#and then he introduces robespierre

Text

Grey history is so good y'all

#MANNN THE EPISODES ABOUT THE LEGISLATIVE ARE. SO. GOOD.#The explanation of brissot and the war party was *chef kiss*#and then he introduces robespierre#It's so neutral and fair but so passionate I was 😳😳😳 the entire time#Reminded me why robespierre is my fave

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being a Polish frev fan is really weird because you see people arguing about Robespierre in some film all of the time but then you look into it and think: 'Hello, Mr. Andrzej.'

#this applies to both Wajda and Seweryn#He's just Andrzej in the way of 'he's just ken'#this Danton is Klaus Maria Brandauer#and he's just Andrzej#I'm a Pszoniak-Robespierre defender for only one reason#i like Wojciech Pszoniak#yeah.#and also 'Danton' 1983 is the movie that introduced me to the Frev fandom#so#🤷#frev#frev shitposting#not a jeeves and wooster post#wojciech pszoniak#andrzej wajda

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found the Charlotte Robespierre-pins-down-Couthon-in-an-armchair-and-calls-him-a-hypocrite anecdote in its full glory within La Révolution, la Terreur, le Directoire 1791-1799: d’après les mémoires de Gaillard (1908) page 263-272. The table of contents claim this event happened in May 1794.

-

Gaillard therefore presents himself at Mlle Robespierre's house, she welcomes him in a friendly manner, she does not seek to know the political opinions of her visitor; both talk for a long time about her family and their old acquaintances, she names for Gaillard, with great bitterness, the prodigious number of very honest people dragged to the scaffold by Joseph Lebon; she makes him tell her how he was able to save himself at least from prison and tells him how much pleasure she and her older brother felt in receiving news of him from their younger brother; then Gaillard explains to her the embarrassment he finds himself in and asks her to help him with her advice to save the magistrates of Melun and the signatories of the address to Louis XVI.

”When my younger brother passed through Melun,” said Mlle Robespierre, ”all three of us were living together; I still hoped to be able to bring back the older, to snatch him from the wretches who obsess over him and lead him to the scaffold. They felt that my brother would eventually escape them if I regained his confidence, they destroyed me entirely in his mind; today he hates the sister who served as his mother… For several months he has been living alone, and although lodged in the same house, I no longer have the power to approach him… I loved him tenderly, I still do… His excesses are the consequence of the domination under which he groans, I am sure of it, but knowing no way to break the yoke he has allowed himself to be placed under, and no longer able to bear the pain and the shame of to see my brother devote his name to general execration, I ardently desire his death as well as mine. Judge of my unhappiness!… But let’s return to what interests you. The addresses to the king on the events of 1792 are already far from us; it seems to me that the signatures of these addresses are persecuted less than those who protested against the day of May 31. Try to see Maximilien, you will be content; he was very glad that our younger brother saw you at Melun. On this occasion he spoke with interest of the exercises of your pupils and of the attention you had in entrusting him with presiding over them. I won’t introduce you to him, I would not succeed; I even advise you not to speak to him about me. You will be told he is out, don't believe it, insist on your visit.”

The Robespierre family was housed on rue Saint-Honoré, near the Assomption chapel, the sister and younger brother at the front, the older brother at the back of the courtyard. Gaillard went to Maximilien’s apartment; a young man, looking at him with the most insolent air, said to him, barely having opened the door: “The representative isn’t home…”

“He may not be there for those who come to talk to him about business, but that is not my doing; I will talk to him about his family that I know a lot, you have seen me come out of his sister's apartment who is involved in state affairs no more than I am... Bring my name to the representative, he will receive me, I’m sure of it.”

The fellow did not dare refuse to carry a paper on which Gaillard had taken care to indicate himself in such a way as to be recognized, he immediately came back and gave the visitor his paper saying: “The representative does not know you,” and the door was violently slammed shut!…

The insolence of this brazen man whom Gaillard knew to be the secretary of Robespierre, son of Duplay, to whom the sister attributed the excesses of his brother, the sorrow he felt at losing the hope of saving the judges of Melun and to ensure his personal rest, all these thoughts made him very angry; he calls the young man a liar, insolent, he accuses him of deceiving Robespierre and of increasing the number of his enemies every day, all this in the loudest voice with the intention of being heard by Maximilien and lure him to one of the windows where, surely, he would have recognized him. New disappointment, no one appears and Gaillard goes back to tell Mlle Robespierre about his misadventure.

“I prepared you for it, she told him. ”No one can approach my brother unless he is a friend of those Duplays, with whom we are lodging; these wretches have neither intelligence nor education, explain to me their ascendancy over Maximilien. However, I do not despair of breaking the spell that holds him under their yoke; for that I am awaiting the return of my other brother, who has the right to see Maximilien. If the discovery I just made doesn't rid us of this race of vipers forever, my family is forever lost. You know what a miserable state we found ourselves in, reduced to alms, my brothers and I, if the sister of our father hadn’t taken us in. It’s strange that you didn’t often notice how much her husband’s brusqueness and formality made us pay dearly for the bread he gave us; but you must also have noticed that if indigence saddened us, it never degraded us and you always judged us incapable of containing money through a dubious action. Maximilien, who makes me so unhappy, has never given a hold, as you know, in terms of delicacy. Imagiene his fury when he learns that these miserable Duplays are using his name and his credit to get themselves the rarest goods at a low price from the merchants. So while all of Paris is forced to line up at the baker's shop every morning to get a few ounces of black, disgusting bread, the Duplays eat very good bread because the Incorruptible sits at their table: the same pretext provides them with sugar, oil, soap of the best quality, which the inhabitant of Paris would seek in vain in the best shops... How my brother's pride would be humiliated if he knew the abuse that these wretches make of his name! What would become of his popularity, even among his most ardent supporters? Certainly my brother is very proud, it is in him a capital fault; you must remember, you and I have often lamented the ridicule he made for himself by his vanity, the great number of enemies he made for himself by his disdainful and contemptuous tone, but he is not bloodthirsty. Certainly he believes he can overthrow his adversaries and his enemies by the superiority of his talent.”

The tenderness of this unfortunate girl for her brother was therefore very keen and very blind, she forgot that, a few moments before, she had told Gaillard, with the accent of despair and with eyes filled with tears, that death would seem preferable to the pain of seeing Maximilien dedicate his name to public execration, and yet her brother for his part had devoted mortal hatred to her since the trip she had made to Arras to collect evidence of the massacres carried out by Joseph Lebon.

“In the absence of my brother,” said Mlle Robespierre to Gaillard, would you like to try to see Couthon? He prides himself on being good for me, I will ask him to receive you, he will not refuse me, I will precede you by a quarter of an hour, he will give the order to let you in and we will exit together.”

Gaillard gratefully accepts, takes the address of Couthon who lived at n. 97 of the Cour du Manège, today rue de Rivoli, near rue du 29 Juilliet, and the next morning arrives at the indicated time.

Couthon, whose face was truly angelic, wore a white dressing gown. A child of five or six years old, beautiful as Love, was between his father's legs; he had a young white rabbit in his arms which he was feeding alfalfa. Mme Couthon and Mlle Robespierre stood in the embrasure of a window overlooking the Tuileries.

“You (vous) are,” said Couthon to Gaillard, a friend of Mlle Robespierre, you therefore have every kind of right to my interest, tell me, citizen, how can I be of use to you?”

The fine face, the entourage of innocence, the tone, the manners of good company, this care not to use tutoient when everyone else did so, convinced Gaillard that the slander had attached itself in particular to the person of this worthy M. Couthon, he promises to undeceive all those with whom the deputy had relations.

“Citizen representative, one of your colleagues, Maure, deputy for Yonne, had recalled the former judges, all very honest people, to the courts of Melun, and everyone applauded this act of justice. The popular society was offended by this, it threatened Maure that it was going to denounce him to the Convention as a supporter of Louis XVI and his family, given that these judges had adhered to the address by which the directorate of the department complained of the outrages committed against the king on the day of June 20 1792. The next day your colleague issued a decree dismissing these judges who were not yet installed, and ordered the revolutionary committee to incarcerate them. Can you please tell me by which means these unfortunate judges can escape this act of severity?”

“Admit, citizen,” answered Couthon, “that the Convention is indeed to be pitied for being forced to send as commissioners to the departments a crowd of imbeciles who make it hated and who compromise liberty... Maure doesn’t have the strength to understand that true patriots were saddened and rightly outraged by this fatal day of June 20. The aristocrats, as one said then, were delighted by it, the crimes of the people seemed to them a means of forever losing liberty and reestablishing despotism... It was a duty to rise up against the violation of the home of the first official of the the State and the bloody outrages to which it was subjected that day. I signed an address in which our indignation was expressed in the most energetic terms and I am far from repenting of it. Have the judges you are talking to me about been arrested?”

“No, citizen.”

”That’s what I suspected, they will have been warned; in fact, one is not going to prison automatically, one will have their homes sealed and perhaps not be very eager to arrest them?… Can you assure me, citizen, that these judges are honest men?”

”The most honest people in the country!”

”Well, on reflection, I was going to give you bad advice... based on the distance from Melun to Paris, this is where they will come to hide, one will find them, there is no safety in the prisons of Paris. They'd better go home, they shall be given a guard, they won't even be incarcerated... but once again, how can it be made a crime to have signed these addresses?”

“Citizen,” continues Gaillard, with great emotion, you are convinced that the signatures of these addresses have not committed a crime, you are all-powerful in the Committee of Public Safety where your opinion always prevails. Today, seventy unfortunate people are being led to the scaffold, their condemnation based on nothing other than the signing of these addresses…”

Couthon's face changed, he suddenly takes on the tiger's mask, makes a movement to grab the bell pull... Mlle Robespierre rushes at him to stop him (he was paralyzed from the legs down), turns towards Gaillard and says to him: “Save yourself!” In the confusion into which all this throws him, Gaillard takes Couthon's hat, she notices it, warns him, he runs across the apartment and reaches the stairs. He had barely gone down eight or ten steps when he heard Mlle Robespierre shouting to him: “Go and wait for me at the Orangerie.” (The courtyard of the Orangerie was located at the end of the Terrace des Feuillants where Rue de Rivoli now meets Place de la Concorde).

When Gaillard was able to think, he wondered why the various sentries posted along the Feuillants terrace had not stopped him. A glance in a mirror while picking up his hat in Couthon's salon had told him how altered his face was. Even after leaving the deputy, he did not think he was safe, he did not take four strides without wondering if he was being pursued. He has barely gone down into the courtyard of the Orangery when he goes back up onto the terrace, looking anxiously to see if his good angel was arriving. As soon as he sees her, he runs towards her, loudly asking her five or six questions at the same time without paying attention to the crowd around them. Mlle Robespierre, calmer, tells him in a low voice that she will answer him when they have reached the Place de la Révolution.

“Explain to me, please,” said Gaillard to Mlle Robespierre as soon as they were offshore, ”your haste to tell me to take flight flee and why you held back Couthon in his chair?”

“You were fooled, my dear monsieur, by the profound hypocrisy of Couthon, I was completely fooled myself; I believed your judges saved and you forever at peace like all the signatories of these addresses to Louis XVI... Couthon only showed himself to be so good-natured in order to get to know the depths of your thoughts, you fell into his trap, I could not have avoided it more than you. Your bloody and so justly deserved reproach regarding the 63 victims of today struck in the hearth, my presence, even my confidence could not have stopped his vengeance. The members of the Committee of Public Safety each have five or six men at home who are resolute at their command, because they are constantly trembling. Had he reached the bell pull, this very afternoon you would have been placed in the tumbril alongside the 63 unfortunate people you wanted to save... Fortunately, I succeeded in making him ashamed of the crime he was going to commit by immolating a friend that I had brought to his house... Will he keep his word to me? I followed your conversation very attentively, you did not say a word from which Couthon could conclude that you do not live in Paris... Return home quickly, do not follow the ordinary route out of fear that, remembering the name of the city where your judges were to sit, he sends for men to follow you on the road to Melun.” (1)

Mlle Robespierre barely gives her protégé time to thank her and does not want him to accompany her back to her house. Gaillard leaves immediately without seeing his sister or the two dismissed judges, who have taken refuge in Paris.

(1) The story of Gaillard's visit to Couthon is reproduced almost word for word by M. Lenôtre, in his Paris révolutionnaire, vielles maisons, vieux papiers, 1900, La Brouette de Couthon, p. 279.* Mr. Lenôtre draws his story from the collection of Victorien Sardou's autographs. The note appearing among these authographs which speaks of Couthon comes from Fouché's papers: it is in fact Gaillard who, at the request of his friend Fouché, recorded in writing for him the narration of his interview with Couthon. Gaillard took pleasure in often recounting to the people with whom he was in contact this scene of which he had always retained such a terrifying impression of; this is the reason why it appears today in his memoirs.

*Worth noting is that Charlotte’s identitity is kept a secret in this account, she’s simply described as ”a lady.” This account also includes the detail of Couthon’s son starting to cry and the bunny he was holding getting pushed to the floor once his father gets mad.

#charlotte robespierre#robespierre#couthon#georges couthon#frev#someone should draw this…#or just make anything of it at all since this side of charlotte is somehow never brought up by today’s historians#like why she’s SO much more fun like this…#fouché#joseph fouché#girl physically restrains a member of the cps and (allegedly) gets accused of poisoning another

88 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have some good sources about how women during the frev thought about universal male suffrage?

(i've been uncomfortable with some claims about how the frev was not feminist enough because women got the rights to vote in the 20th century, but cannot back up this discomfort.)

"I am quite limited on certain subjects and this is one of them (I am currently researching the exact thoughts of women during the French Revolution on universal suffrage).

Unfortunately, it has been a great shame that the French Revolution was misogynistic despite the meager rights that were gradually taken away from them over time. Even the greatest progressives like Sylvain Maréchal, who was an important disciple of Babeuf, had as a project to ensure that women did not have a say in the learning of reading.

The fact that misogyny was already present during the Ancien Régime (Marie Antoinette is blamed for all evils when in reality she did not have much say during her husband's reign, to better absolve Louis XVI and the policy of France under this absolute regime) or that Napoleon made the condition of women worse than that of Italy or Spain (I mentioned this in my post 'Women's Rights Suppressed') while being a great hypocrite does not absolve the revolutionaries for what they did in their misogyny.

There was a habit of attacking the wives of their adversaries to better discredit them (like Manon Roland, Marie Françoise Goupil, wife of Hébert, Lucile Duplessis, wife of Desmoulins), which is an interesting parallel on this point with the attacks against Marie Antoinette.

Olympe de Gouges spoke about the rights of women and citizens. Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, who demanded the right to organize in the national army. Théroigne de Méricourt, Louis Reine Audu, and again Claire Lacombe fought in the Tuileries and yet, despite being rewarded with a civic crown, they would not have the right to speak on universal suffrage.

Chaumette was a great misogynist, Robespierre too (one could tell me that he supported Louise de Keralio's candidacy for her entry into the academy, but in political matters, it was another story), Danton, Sylvain Maréchal, Amar, etc. I am not here to blame Robespierre and I deplore that there is a black legend about him, but one can see a certain purely political gesture in my opinion for the action he will take towards Simone Evrard.

As much as Simone Evrard is a very intelligent woman, with an extraordinary destiny very underestimated, capable of making very good political speeches (one of the people of the French Revolution that I admire the most), I wonder if the fact that Robespierre personally introduced her into the Assembly was just an opportunistic gesture because he would have had an additional reason to discredit Jacques Roux and Théophile Leclerc thanks to the speech she made while he was among the revolutionaries who approved the restriction of women's rights. Respect towards Simone Evrard regarding her dignity and intelligence (maybe even surely) opportunism, I would be tempted to answer on this by affirmative.

Risking repeating myself, Napoleon being a greater oppressor towards women by taking away the few rights they had, enacting oppressive and hypocritical laws, and even bloody ones concerning them, does not absolve the other revolutionaries of their sexism.

And there is no excuse that it was of their time (in fact, I noticed that this lie is used in my opinion to absolve Napoleon but not the revolutionaries, but forced to see that it fits into the same idea)... First of all, Charles Gilbert Romme was more progressive in women's rights, Marat and Charlier too, Camille Desmoulins thought that women could have the right to vote, Condorcet demanded gender equality, Carnot worked with him in women education with Pastoret and Guilloud , Guyomar opposed the exclusion of women from universal suffrage. Worse than anything, while the clubs and societies of women ended up being banned, which is a regression.

In 1795, for attempting to revolt against the Assembly which abolished the social policies of the Montagnards, they were prohibited from attending assemblies and even from gathering in the streets in groups of more than 5. Moreover, the term 'tricoteuse' to insult women was not invented during the Napoleonic era or the royalist era but in 1795.

What did women think about this? This is where I am quite limited because besides the answers I have given about these women and their actions, unfortunately, there is not much else I can say due to my limited knowledge.

In any case, I hope I have helped a bit to support the aforementioned statements.

In the meantime, I can provide some of my sources: the historian Mathilde Larrère, Antoine Resche who made very good summarized portraits of some revolutionary women on the website 'veni vidi sensi', I would also recommend reading the book by the writer Claude Guillon on Robespierre, women, and the Revolution (even though I completely disagree with some of his books that have been legally condemned, this one is rather good and he had a quite good blog on the French Revolution that I recommend checking out), and the historian Jean-Clément Martin, 'La révolte brisée'."

Reedit: Thank you to aedesluminis for inform me the role that Carnot Pastoret and Guilloud did with women's education.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Went, I Saw, I’m Back….

Today was Napoleon movie day and I lived to come back and report.

You know how you go into a movie with super high expectations when you have heard it’s the best thing ever, then inevitably find it less than you expected? The reverse happened a bit for me, everyone had hated this so my expectations were low, and though the movie is problematic, because everyone I read was losing their minds, it wasn’t that bad.

That is not to say it was good.

So for me it’s a mixed bag of stuff. Things I liked and and things I did not.

The main problem with the movie is that it tries to fit everything in it and therefore nothing works because everything is trying to be in there. Since they try to cover everything, nothing is covered and everything suffers, including the flow of the movie. It’s one of the movies that I felt like I could see what they were trying to do, and maybe it would have worked if they didn’t slam everything in there.

So this is going to be a bit scattered because my thoughts are scattered. And warning: spoilers will be discussed.

I wish they would have just skipped the French Revolution altogether and assumed the audience had a working knowledge of it. Shoehorning it in didn’t work. We have a brief scene of Marie Antoinette running the halls with her children trying to escape arrest to then a fade out of her execution. Yes, it’s all wrong, she is too defiant, her hair is too long, her dress is wrong. I get what they are going for here and a defiant Queen is probably a bit more dramatic than one who apologizes to her executioner for stepping his his shoes. Napoleon in the crowd, even though he wasn’t really there, works in the dramatic licensing department and his reaction was actually good.

Then we are whisked to Napoleon getting into a meeting with Barras, who acts as a sort of a narrator to the audience to catch them up on the state of things and Toulon. What I dislike in this film is that they introduce the characters by flashing their names and titles on screen. Ugh. I do not like this. Napoleon gives his plans on what he’d do with Toulon and Lucien (he’s been mistaken as Joseph in some reviews) acts as interpreter to Barras over what Napoleon just said (What my brother is saying….) .

There is a bit of time spent at Toulon with Napoleon walking around the place and even melting cannons for new cannons. The British are brutes who yell at him calling him a “shitbag” and yelling at the locals to move their “fucking goats!” . No, they really had wandering goats.

The battle is intense. Now, I know a lot of complaints have been filed due to battle inaccuracies and too few of them. This isn’t a problem for me. I am not a scholar on Napoleonic warfare. I am a wimp when it comes to blood and gore. I dislike seeing people blown up but even hate seeing horses blown up more. So one of the first casualties of Toulon is Napoleon’s beautiful white innocent horse. It takes a cannon ball to the chest and it’s graphic and it makes me want to do a cry. The horse falls and Napoleon is thrown but regains his composure to go fight with one on one with some a combatant until someone else decapitates the guy with a sword.

One battle down more to go.

Barras magically is on scene to literally crown Napoleon general with a sword like the Queen knights people. Napoleon wanders away to his poor dead horse and fished out the ball lodged in the chest and hands it off to I think Junot with instructions to give it to someone. I thought I heard “for mother” but that can’t be it….can it?

Now we are back to revolution stuff and Robespierre is being denounced. Why are we putting this in here? It’s too…whatever. He runs out of the chamber, tries to shoot himself when he can’t shoot the chamber and of course just ends up wounding himself in his jaw. Barras pops over to put his finger in the wound (ew sir) and tells him he missed and off to the guillotine for you “dear friend”.

Enter Josephine. She escapes her prison in her dramatic cloak where she is hugged by a nameless woman.

Enter Napoleon being instructed by Barras on the civilians uprising. There is a scene of Napoleon wandering through a crowd of citizens shouting long live the King. Napoleon places his cannon, the citizens line up and then boom! More bloodshed for everyone. People are mowed down, blood spray. The back crowd runs off and the camera pans to a woman trying to crawl away with her severed foot in the street. No horses dead thankfully.

Back to Josephine in her cloak walking empty Paris streets and looking at various overturned debris. Is she just walking the streets for days? Is she coming upon the whiff of grapeshot? We don’t know.

Napoleon is now wandering around a Survivor’s ball. The lighting is gorgeous in here. Josephine has ditched her cloak for a dress her boob might escape from at any moment. She’s sitting with Barras with her insane asylum haircut and red long gloves and red ribbon neck decoration. Napoleon looks bored. Later Napoleon is still wandering around and Josephine is hanging out gambling. She notices Napoleon starring at her and confronts him. Here we meet Josephine with her dramatic British accent and Napoleon’s awkward American one (but it strangely fits all the same). She asks why he was starting and there is some back and forth but no lines from the trailer with her “has the course of my life change Napoleon?” Instead Napoleon tells her not to tell him her name and she stares at him and wanders off to gamble some more I guess. What?

Next is the scene with a very small Eugene doing the probably made up Napoleon myth scene of “Can I have my father’s sword please sir?” Napoleon and Junot have been throwing shit at the wall before this for…reasons. Napoleon explains to Eugene that he can’t give back the sword because citizens can’t have weapons. The boy says it’s a rememberance of his dead father. Napoleon asks what he is doing there and the boy says his mother said that Napoleon could. Napoleon then goes to a room with loads of swords that were taken from the executed officers. Napoleon asks if anyone thought to put names to them but no, they did not. Napoleon grabs a random sword and heads to chez Beauharnais. There everyone seems to know him, including the help, and he gives the maybe sword back to Eugene. Everyone thanks him and Napoleon tells Josephine that he gives his compliments to the house chef. ???

Now Napoleon has random meetings with Josephine that I guess is supposed to be their abbreviated courtship. Josephine stares into her makeup mirror and wonders aloud to her maid (Lucille) if she looks in love. They have random conversations about how her husband was executed in front of his mistresses. How she tried to get pregnant in prison to save her life. Will any of this bother Napoleon? Napoleon answers “no, madam”. She flashes him her nether regions and Napoleon just stares. Awkward. Some old lady behind me in the theatre went “oh!”

Oh well then it’s time to get married.Josephine has the fastest growing hair in the history of the world. Last scene she was a mental patient, now her hair is shoulder length. They are giddy, well Napoleon is, at the register’s. They are sure to share Josephine’s real name but then announce that Napoleon was born in February. What? Didn’t he just change the year and not the month of his birth? But none of it matters since they never discuss their age difference anyway.

They have a dinner party where Josephine flirts with Hippolyte Charles with Napoleon glowering and then we cut to the sexy time scene where Napoleon and Josephine have sex doggy style! Oh God. Cringe. Napoleon talks of having a son. Napoleon is very broody in this movie.

Napoleon is now in Egypt. Italy is mentioned only in a letter voice over where he happily informs Josephine that he was victorious in Italy. He wonders why she isn’t writing. Insert scenes of a naked butt Charles romping in bed with Josephine. Napoleon and the mamalukes line up by the pyramids and Napoleon fires the cannons. They hit the pyramids and then he just wanders away. Is this the battle? Lol One mamaluke falls off his horse. No horse casualties.

If you ever felt that General Dumas never got his moments to shine, well he is in this movie. He’s not singled out, you just have to know it’s him. He accompanies Napoleon to see a mummy. Napoleon looks at the mummy and goes to touch it’s cheek and the mummy shifts away from his touch. Is this like some omen that like Josephine, even dead mummy’s don’t want Napoleon touching them? Lol

Junot later informs Napoleon while they eat that Josephine is unfaithful. Napoleon tells Junot that he gets no dessert and to leave, which he does. They later meet up again and Napoleon tells him he’s off to France.

Napoleon lands to fanfare in France and greets the crowd with smiles and waves. He gets in the coach, finds an English paper making fun of him and Josephine’s affairs. He waves at people out the window. He arrives home to No Josephine but dogs! There are a lot of dogs in this movie that is a win for me. He questions Lucille on her whereabouts, throws wine at her and tips a chair over. Josephine arrives to her luggage in the yard and she goes to the locked door and….next scene she is in tears and Napoleon is yelling. She is a “selfish little pig” and how could she do this…why didn’t she think of his feelings? Josephine says sorry and Napoleon makes her say she is nothing without him.

The scene cuts to the first of many scenes of Napoleon sitting awkwardly on the couches with their heads on the back cushions staring at each other. Lol. Can’t they sit normal? What are these two adults doing? Here Josephine makes Napoleon recite to her that he is a brute that is nothing without her and “your mother”. Oh boy, Napoleon is a mama’s boy too.

Napoleon has a meeting with those in charge which is a great scene of him telling all of them that they aren’t fit to run France. They accuse him of deserting his army in Egypt. He points out one by one why they can’t serve getting to one man and saying “though you can scowl very well!” He marches out saying that they have nerve questioning him when they have ruined France and he has found out his wife is a slut.

Napoleon has brunch with Sieyes and he invites him to a coup. Scenes follow of the various men being arrested or asked to step down. One man tries to escape by running up the stairs and then getting into a slap fest with two soldiers. Dumas arrests another man who says he can’t believe this he was just about to have a “scrumptious breakfast!” Dumas escorts him out leaving his hysterically crying wife saying “enjoy your breakfast”. Talleyrand tells Barras of his dismissal to which Barras says he will gladly go back to being a private citizen.

The coup is hysterical. But it was, wasn’t it? Napoleon gets manhandled and runs away falling down a flight of steps and barricading the door from the mob. He can barely stand up. Now I know some of this rubs scholars the wrong way but the coup was about as good as this. Napoleon was given a horse that he couldn’t control and was almost thrown off.

Now Napoleon is talking to Caulaincourt who talks to him about the czar. This scene actually works well. Napoleon walks around questioning and using his knife to hack away at the furniture.

Napoleon confronts an ambassador and screams at him. Here is where he shouts “you think you are so great because you have boats!”before stomping out. It is laughable but again, Napoleon was known to do this at times. He did kick one ambassador in the stomach once for no reason.

Talleyrand says hey why don’t you become Emperor. Napoleon laughs and pinches his ear.

Napoleon leads an older woman around. You guessed it! Mama is on scene. Napoleon walks her over to Josephine where Madame Mere says “This must be Josephine!” They nod at each other and then Madame Mere says “Is that Charles?” and wanders off to talk to Talleyrand. Who knew they were friends?

Napoleon still is broody. He walks in on Josephine dressing and acts like a horse, baying and stomping the ground. Josephine dismisses the maid and says “you nasty man” and more doggie style sex! She tells him her nether regions are his. Cringe.

Napoleon the next morning questions Josephine on why she isn’t pregnant. She makes excuses but says she has been busy cleaning up his messes. Napoleon whimpers again, crawls under the table and grabs her.

It’s coronation time baby! No lead up, just happens. Hippolyte Charles is there to give the evil eye to the imperial couple. Josephine looks at him as she walks by. Barras comes out of nowhere to get a prime seat up at the Dias. The pope is pretty enthusiastic proclaiming Napoleon emperor. The end.

Now Napoleon is watching David paint his portrait with a model as Talleyrand says he needs to divorce.

Now we are at Austerlitz. This is beautifully shot. There are lots of blood in the water and sadly dead horses. This doesn’t seem to be a lake they are falling into, but the ocean as they sink sink sink forever.

Now Napoleon is chatting up Emperor Francis.

Now there is a montage of happy Napoleon and Josephine moments. Napoleon plays with a dog while Josephine smiles. Napoleon and Josephine share a bath.

Now Napoleon and Josephine sit at a dinner party and Napoleon asks in front of everyone why isn’t she pregnant? Awkward. Josephine says there hasn’t been much love making in the place. Awkward. Napoleon’s mother is even like “ew”. Napoleon says that is a lie. There has been years and years! Josephine fires back that he is a fat fat fatty. Napoleon says that is true, he likes to eat, destiny brought him this lamb chop. Josephine throws food at him. Napoleon throws food at her. She throws more. WTF is going on here? No lie, an older man behind me in the theater whispered in this scene to his wife “he’s probably been putting it in the wrong hole. “

Madame Mere is the one and not Caroline to tell Napoleon she has rounded up a girl for him to see if he can get her pregnant. She says it’s time to know who is at fault. Napoleon and she drink brandy while Napoleon studies his feet. She says the girl, Elenore Denuelle, is waiting for him naked in the bed. Napoleon asks if he can have another brandy. He pauses at the door while mama shooes him in.

Next scene Madame Mere tells Napoleon the happy news of Elenore’s pregnancy.

Napoleon and Josephine have an awkward stare conversation sliding down on the couch.

Napoleon announces over dinner with Josephine the divorce. She tears up but then laughs. Napoleon leaves in a huff.

The divorce scene. Josephine has tears rolling down her cheeks. Napoleon sniffles and roughly wipes her face and his. He reads his statement. Barras is also somehow here too. Standing in the audience like a bad omen. Napoleon scolds Josephine to read her statement. She can’t get through it because she keeps laughing. I guess we are going for hysterical laughter but it plays wrong. And of course the history is that she cried so much she had to have the statement read by someone else. Here she gets slapped by Napoleon to her shock and everyone else’s but still laughs her way through it.

Josephine leaves in her carriage and lands at someplace that is Malmaison but is not Malmaison. She walks around gloomy. Napoleon visits her and puts his hat on her head. Tells her to cheer up.

Napoleon chats with the Czar and tries to marry his sister.

Napoleon is now meeting Marie Louise. Now the casting is all screwed up. Napoleon ages through the film but for some reason Josephine never does. Josephine is taller than Napoleon even though she was in reality shorter. Marie Louise is a black haired little thing when in reality she was taller than Napoleon.

Napoleon is given his son. He cries. He’s been wanting a kid for a long time, man. Napoleon takes the baby to Malmaison to visit Josephine who looks like for a second she might throw the baby over a Cliff.

Napoleon is off to Russia. Cossacks attack. Napoleon rips off little pieces of bread to his troops as they walk by. They fight at Borodino and Napoleon is leading a Calvary charge but what the hell? He’s wearing his Italian uniform. Since when did fat Napoleon get into his closest and grab up his ornate uniform? My guess is that this was meant to be Italy, they scrapped it for time and used this footage for Borodino thinking no one would notice.

Napoleon find Moscow abandoned including the Kremlin that has apparently been abandoned for decades as pigeons have taken over the place and have shit all over the czar’s nice throne. Napoleon fits so he sits. Birds continue to shit on it. I think this is supposed to be some poetic metaphor.

Napoleon wakes up flames. He comes out and asks who did this. Luckily the marshals are all there waiting and inform him. He wants to march to Petersburg. They tell him no because of winter. Napoleon puts his hands over his ears and then screams into his hat. Chill man.

Napoleon marches back in snow. Dead people. Men eating horses. Not the horses!!

Oh Napoleon is abdicating. That’s quick. Surprisingly Barras is missing from the audience.

Napoleon lands on Elba and parades around. Josephine greets the Czar and dances with him in a really stupid dress. Malmaison is always cloudy with fog and rain. Always. Every scene. Napoleon sees a paper on Elba that mocks him about Josephine entertaining the czar and him being cuckolded again. But they are divorced? He beats the paper on the table. He then writes to Josephine and tells her that he is coming back to France to reclaim his stuff including her. So I guess we don’t care about Marie Louise or baby anymore.

Btw, Josephine should be dead by now.

Josephine is shown being ill and the doctor telling her to open her mouth. He says her chest is congested and her throat inflamed and recommends going to bed. But she says Napoleon is coming over and over again. I don’t think Josephine ever called a Napoleon Napoleon either.

Napoleon gets on ship and lands on French soil. Kisses it. Josephine dies. Finally. Too late.

Napoleon greets his troops. They go to his side. He lands at Malmaison and learns from Hortense that Josephine is dead from diphtheria. Napoleon is mad at her. Why didn’t anyone tell him? He wants her letters that he wrote to her. Hortense says the valet stole them and sold them. Napoleon cries. Hortense apologizes and Napoleon says he forgives her. For what though?

Napoleon is at Waterloo. Rupert Everett is Wellington but all I can think is damn he’s old. I remember when he was a heart-throb in movies and now he’s old Wellington. Battle. Dead horses (no!!!) dead men. This is the longest battle filmed.

Napoleon is on the Bellerophon giving a class to a bunch of boys. Wellington for some reason comes for a meeting and Napoleon and he are rather friendly to each other. I wonder where Barras is? He could be here. He wasn’t. But he could be. Wellington dashes Napoleon’s hopes of remaining in England and tells him he will be off to St. Helena “a rock really”. Napoleon laughs.

At long last, Napoleon is on St. Helena with a voice over with Josephine talking to Napoleon. Next time she will be Emperor and he will have to listen to her. Napoleon is shown washing his face. Napoleon is shown drinking wine at his desk while plantblow out of the ground outside his window. There is a dead fly in his wine that he fishes out. Napoleon is at an outdoor table while Betsy Balcombe and some other girl fence with sticks. Napoleon grills them on the capitals of Europe. They do the Moscow story. How it was burned to get rid of the French. Napoleon asks who told them that and then throws dates at them as they run back to play. Another voice over from Josephine. She tells Napoleon she has prepared a place for him why doesn’t he come? We see Napoleon’s back and his famous hat from the back as he sits at the table. Come she tells him and we will try again. Napoleon drops over dead. Well, that’s not how it went but okay.

Jesus. That was a lot. I will do my final thoughts tomorrow.

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

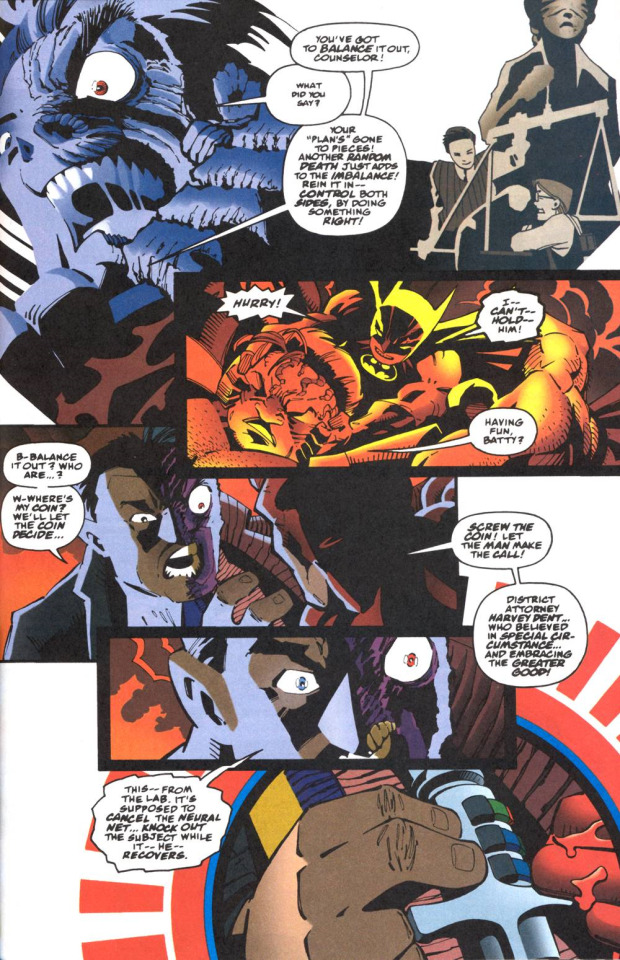

I was just wondering, are there any particularly good Elseworlds or AU stories that involve Two-Face/Harvey in them? Are there any in particular that you'd recommend actually picking up and reading? (I've been thinking about actually reading Masque and Two Faces lately, but was wondering if there were any others worth checking out!)

Ah, Elseworlds,: DC’s venerable AU imprint. As is the case everywhere else, these were a mixed bag of good, bad, weird, and forgettable, and Harvey’s appearances in them was no exception. The two you cited are perfect examples (in addition to being his two most prominent Elseworlds stories):

Two Faces is, pound for pound, the very best Harvey Elseworlds story. Not surprising, since it comes from one of the greatest comic-writing teams ever, Abnett & Lanning! Bruce is a Jekyll figure who “Hydes” himself in the name of finding a chemical cure for Harvey, who has become an airship-flying, bowler-hatted Two-Face.

It’s great, and the conclusion has long been one of my favorite looks at their friendship and the lengths they’ll go for one another. How I wish we’d gotten a sequel with that particular Batman. In terms of Victorian Batman stories, I vastly prefer this to “Gotham By Gaslight,”which I’ve always felt has been rather overrated.

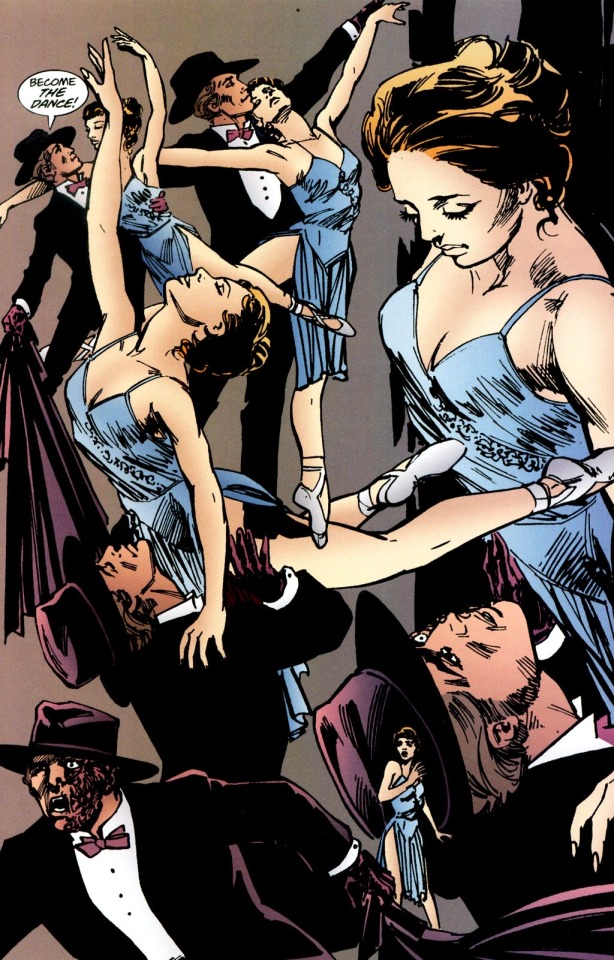

Masque, by contrast, is not very good but still worth reading. I think of Mike Grell as an artist who sometimes writes, and this is very much an artist’s story, using both Bruce and Harvey as Phantom figures with the opera swiped out for ballet, presumably for the purposes of comics being a visual reading medium.

But as both a story and a Phantom tribute, it’s rather thin, with little to say. Still, it has Harvey as a flamboyant, romantic, murderous ballet danseur, so that’s worth checking out on its own.

Beyond those two, there are a few other Elseworlds worth tracking down. The first is in the vein of Masque, in that it’s a thin take on Harvey that entirely coasts on his concept and physical appearance.

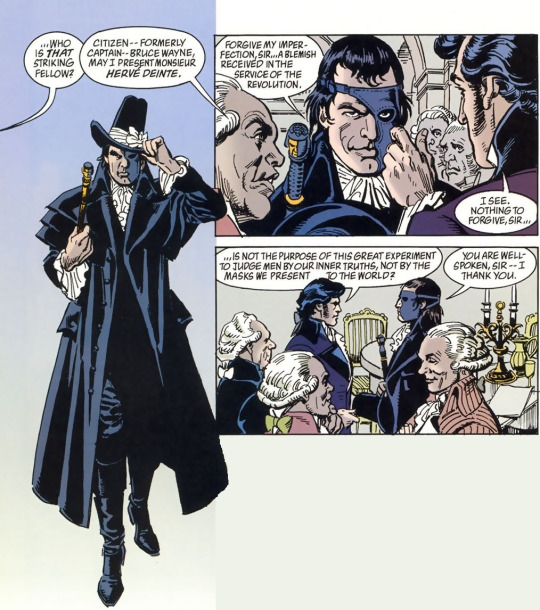

In this take on The Scarlet Pimpernel, Harvey is the French Revolutionary Hervé Deinte, who clashes with the mysterious Bat-Man seeking to fight against Robespierre.

Mike W Barr has never been a good writer of Two-Face, but Jose-Luis Garcia-Lopez’ incredible art more than makes this worth reading, especially for the unusually dashing and dangerous take on Diente.

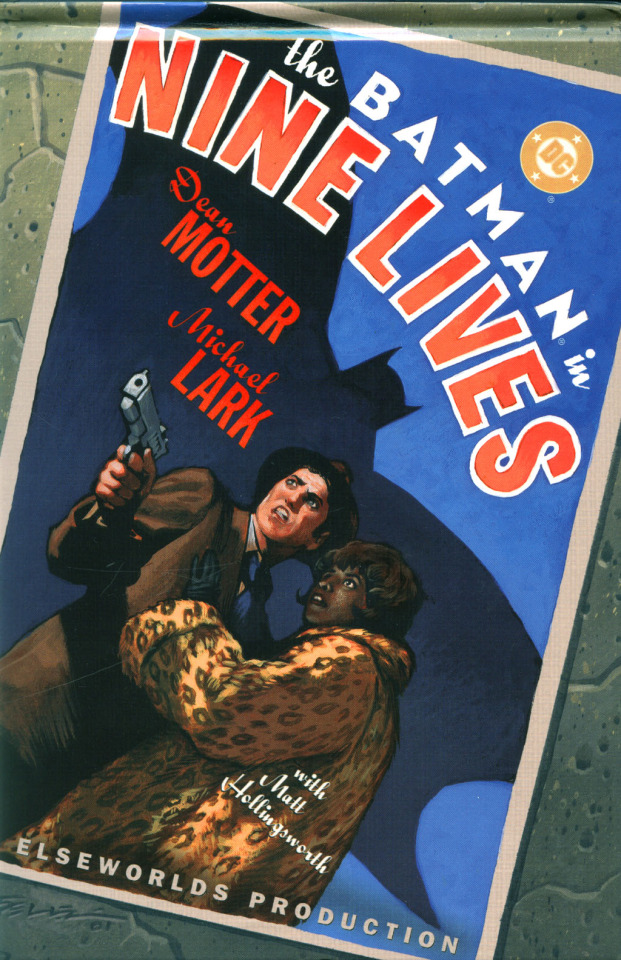

The next recommendations are a pair of noirish tales that came out around the same time. The more famous of these is Nine Lives, which was published sideways to presumably replicate letterbox cinema format.

Harvey in this story is Bruce’s friend and lawyer, but get this: he’s two-faced! In that he sells out Bruce to try getting rich with the Joker stand-in. Plus he uses his coin to con people, not a fan of that.

Still, his face-turn (pun not intended) at the end to save Bruce helps redeem these flaws, and the story is pretty solid noir all around, albeit a bit dry for my tastes.

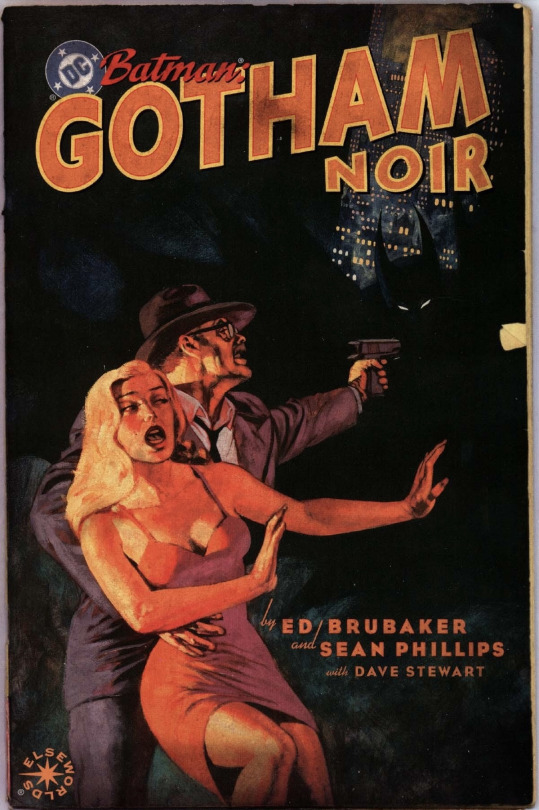

I strongly prefer the other noir Elseworlds, Gotham Noir, by the impeccable team of Brubaker and Phillips. It’s more hard-boiled (more like pulp compared to Nine Lives' literary noir), and not afraid to be a bit more outlandish, and I love Harvey’s role here as the DA, which is more in line with his role in Year One. Brubaker also gets to play with a concept he introduced elsewhere, that Batman is credited as a myth that Dent cooked up to scare criminals.

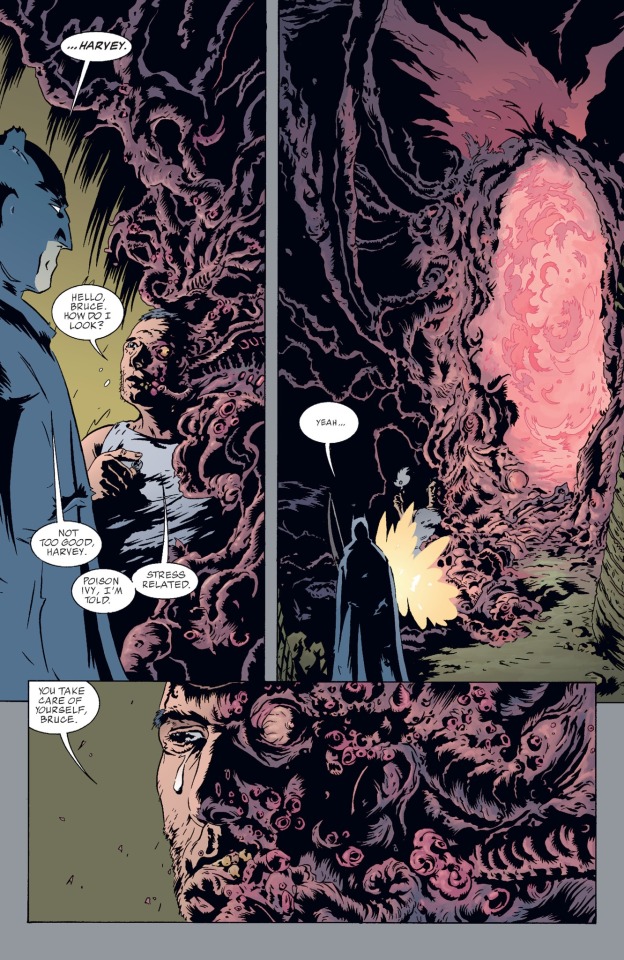

Next up are two Lovecraftian takes on Batman with prominent Harvey roles. The first and far more famous is Mike Mignola’s The Doom That Came To Gotham, which somehow manages to make Harvey suffer even more than usual.

It’s a rare take on a Harvey Dent who is purely good and purely a victim, where even his transformation into a Two-Face of sorts is just… sad. It’s great!

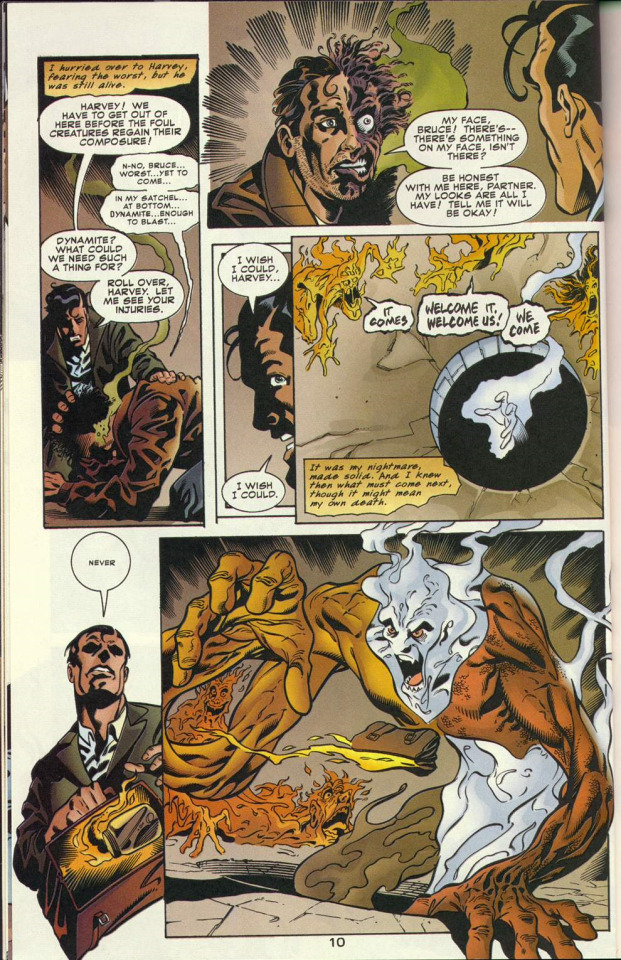

“The Crawling Hand,” however, is far more obscure and for good reason: it was included in the infamous Elseworlds 80-Page Giant which was initially scrapped and pulped before release because of Kyle Baker’s story about Superman’s babysitter. As a result, this story is still a little-known curiosity with Bruce and Harvey trying to survive eldritch takes on DC’s stretchy characters, with Harvey ending up as a surviving casualty lost to madness. Fun!

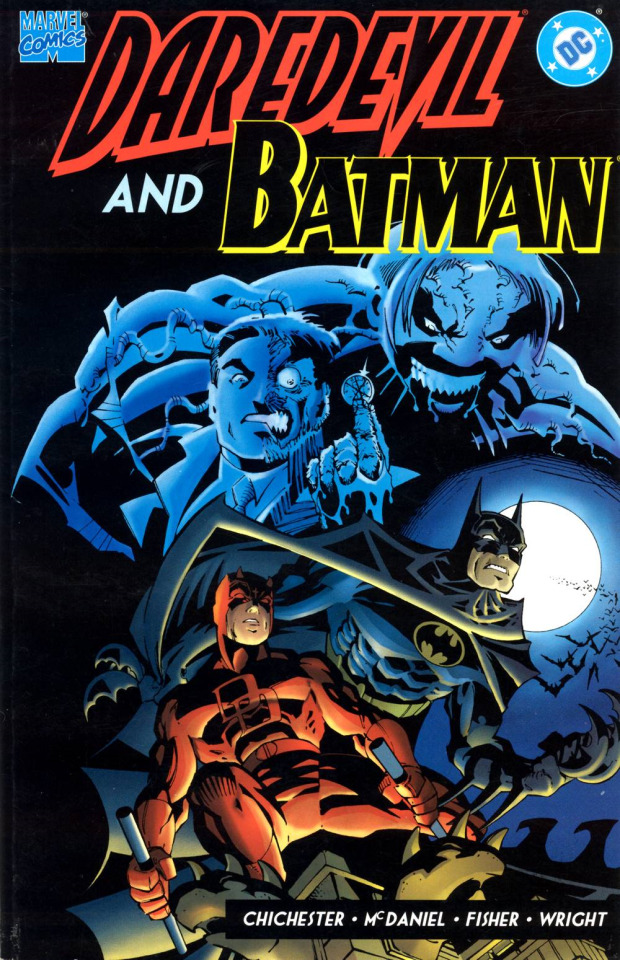

Finally, the last Elseworlds I’d recommend is one that has no reason to be an Elseworlds at all: the Daredevil/Batman crossover. Seriously, why the hell was this an Elseworlds? No one dies, there���s nothing to indicate an alternate setting… literally the only reason I can even imagine why DC slapped on the AU label—seemingly at the last second!—is because they didn’t want it canon that Harvey and Matt Murdock were rival-friends back in college!

Granted, it IS a bit weird to have a story with Matt being the one who believe in Harvey Dent while Batman is a hardline jerkass who hates Harvey, but that was hardly out of place in this era of Bruce being a grim prick. I’m baffled as to why it’s an Elseworlds at all, but hey, it technically counts! Definitely worth checking out either way!

All in all, a mixed bag of good and interesting. Seeing these again makes me long to see the Elseworlds imprint revived, especially now that we're getting new Elseworlds projects in film and TV thanks to James Gunn. Maybe we'll finally see some cool, interesting new takes on Two-Face in the near future!

#apologies for any typos or errors this was a nightmare to compile#neither the app nor desktop tumblr liked me making this post for some reason

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aulard on Herault de Sechelles

Okay here we go, another author who is absolutely in love with Herault. I’m not even joking, Aulard is completely head over heels for this man. So here is his chapter on Herault de Sechelles in his book Les orateurs de la Législative et de la Convention: l'éloquence parlementaire pendant la Révolution française (Tome 2). Link here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5441755r

A few notes:

When I make a translation, I am not agreeing or disagreeing with anything an author says. It's important to keep in mind that every author has their own agenda and writes about historical events and historical figures within the context of their own viewpoint. Aulard , as you will see, is a keen supporter of Danton, and he labels Herault as a Dantoniste throughout the entire chapter. Whether Herault should be considered as a strict Dantoniste is, in my non-professional opinion, up for debate. A lot of people are still not aware, for example, that he and Fabre d'Eglantine were arrested separately to, and before Danton and Camille were arrested, and it was only afterwards that it was decided that they should be tried together.

Aulard neglects to give sources for several of the statements that he makes and is very condescending towards Robespierre and Saint-Just. He also seems to try to justify Herault’s actions during the revolution by saying that he was mostly acting to keep Robespierre off his back. I personally think this is incredibly injurious to Herault, who was an active participant in the Revolution – we have no reason to believe, as many would like to, that he was only pretending to support the Revolution to survive, rather than because he genuinely believed in its principles.

Also, apparently Herault bought a lottery office for one of his mistresses and I just … cannot deal with this man.

Anything with an asterisk is my personal note/observation. I will take the time to remind every one again that my French is dismal and that is why I always link the original. Huge thank you again to @ans-treasurebox for helping me with translating parts of this and also to @orpheusmori who had to sit there and put up with me losing my mind over Herault on the Discord for several nights in a row.

Chapter VIII – Herault de Sechelles

I

Herault de Sechelles was the ornament of the Dantonist party. A man of the court and of noble family (1), a classical and lucid spirit, an orator enamored with academic elegance, he forms a perfect contrast with the rusticity of Legendre. When he was very young, he was introduced to Marie Antoinette by her cousin Madame de Polignac, pleased her, and obtained from her a position as a lawyer at the Chatelet. He won great success there through his talent for speaking and by the choice of his causes, calculated to interest the sensitivity of his protectors. "There is applause on all sides, says one of his biographers, at his eloquent indignation against the ingratitude of a pupil towards his tutor and against the odious behavior of an opulent girl who had abandoned her mother in need."

(1) His grandfather had been lieutenant general; his father, colonel of the Rouergue regiment, had perished gloriously at the Battle of Minden (Jules Claretie, Les Dantonistes, p. 317). He was also a nephew of the Marshal de Contades (Souvenirs de Berryer, I, 1)

In 1779, at the age of 19, he published Eloge de Suger. Serious and charming, he was soon called, by the favor of the Queen (1), to the post of Advocate General in the Parliament of Paris. The parliamentarians, he would say, hated him, either because of the rapidity of his fortune (2), or for his philosophism.

(1) She sent him, it is said, a scarf embroidered with her own hand. - His last speech as a lawyer was a triumph: the magistrates and the audience accompanied him, applauding, to his carriage. Journal de Paris of August 7, 1785, quoted by J. Claretie, ibid.

(2) La pere de Berryer's (ibid.) says that he had been appointed after a hard fight and he adds "He had justified this sudden elevation by the marvelous ease of speaking, which he had shown in various causes of brilliance."

He did not believe himself out of place among the combatants of July 14, and he broke with the court party at the beginning of the revolution. At the end of 1790, he was elected judge in Paris, then he became commissioner of the king at the tribunal de cassation. A member of Parliament for Paris in the Legislative Assembly, he hesitated at first between the royalists and the Jacobins. On the 6th of October, he protested against the revolutionary decree issued the day before on the ceremonial of the royal session. Interrupted as an aristocrat, he was silent and observed in silence until the end of 1791.

On the 29th of December, he delivered a speech on war, in which, in the manner of Brissot, but more briefly, he drew a picture of the state of Europe: according to him, each power was too poor to desire war. All the more reason to demand a lot, to summon the King of Prussia, to intimidate the counterrevolutionaries from within. Is he for war or for peace? Does he support Brissot or Robespierre? We don't know; but we can see in his somewhat equivocal words the Dantoniste policy: let's make war, but let’s be sure about making it, after having defeated the court.

This speech pleased and, although ambiguous, rang true. From then on, Herault followed a democratic line. On the 14th of January, in response to the declaration of Pilnitz, he proposed to the Assembly an address to the people, in which the perfidy of the court was clearly indicated. As for the threats of Europe, France only had to rise to confound them. "Certainly, the French, after having taken such a high rank, will not resolve to descend to the last place; yes, the last, for there is on earth something more vile than a slave people, it is a people who become so again after having known how to cease to be so."

On the 24th of January, he attacked the draft decree presented by the diplomatic committee in response to the Emperor's office: "I regret, he said, that the committee did not announce or rather reiterate the known resolution of France, which, as a consequence of her renunciation of any conquest, having also renounced to meddle in any way with the form of government of other powers, must doubtlessly, in the face of all mankind, expect the most perfect reciprocity; and when one will see a wise people regulating within its homes the form in which it suits it to live, leaving peace to its neighbors and seeking order for itself; if ambitions, vengeance, dare to arm themselves against the happiness of such a people, the world, posterity, history, by pitying them, will avenge them, and will mark with eternal opprobrium their vanquished enemies and even their conquerors, if there could be any.”

This elevated and diplomatic language made an impression and the Assembly voted the draft decree of Herault, by which the king was invited to declare to the emperor that he could henceforth treat with him only in the name of the French nation, to ask him if he wanted to remain the friend of the French nation and to give until the 15th of February to respond.

He was twice rapporteur for the legislation committee: on the 22nd of February, on ministerial responsibility, the conditions of which he discussed pleasantly; on the 7th of April on the acceleration of judgments in cassation.

At the beginning of July 1792, the gravity of the circumstances had led the Assembly to add an extraordinary commission to the diplomatic and military committees. The diplomatic qualities of his words led Herault, on the choice of his colleagues, to be designated for the drafting of the report relating to the declaration of the homeland in danger, a report which would be read with passionate attention by all of Europe (July 11). "Our most important business, he said, is to go to war soon, and not to wait for a chance or a set back which, however slight, might make some of the powers who are now mute observers, but whose diplomatic correspondence shows us, perhaps in the distance, secret hopes and a prudence subordinated to fortune, determine to be against us. Let us therefore produce a great movement, let us deploy a formidable apparatus, let us interest each citizen in his fate: let’s call, it is time, all over the fatherland, all the French, all those who, having sworn to defend the Constitution until death, have the happiness of finally being able to carry out their oath. The fatherland is in danger, and this single word, like the electric spark, hardly left within the national representation, will resound the same day in the 83 departments, will rumble on the heads of the despots and their slaves; and this single word will repel their attacks, or will victoriously support the negotiations, if, however, these are negotiations that we can hear and which in no way alter the immutable sanctity of our rights.”

In a more critical than enthusiastic spirit, Herault examines the objections that could be made to this declaration; he exposes them with a gift of objectivity very rare in this time of passion. He ends with a sufficiently warm oratory: "When, under Louis XIV, despotism, seconded by the genius of Turenne, held in check four armies at the same time, let us believe with confidence in the cause of the human race and in the miracles of freedom. Ah, gentlemen, a prophetic voice rises in my heart: we have sworn to be free; it is to have sworn to conquer! Called, in the face of the universe, to stipulate the rights of humanity, let us avenge these sacred and imperishable rights: I swear by these phalanxes which will gather from all parts of France, and by you, intrepid Gouvion, by you, brave Cazotte; and by all of you whom a death so beautiful and so desirable has reaped before the victory, under the walls of Philippeville; virtuous citizens, whose memory will henceforth preside over our destinies, and whose souls, quivering with joy in the depths of the tombs, will share in all our triumphs!”

In matters of revolutionary enthusiasm, that is all that the noble and pure rhetoric of Herault de Sechelles can give. He understands, he interprets with truth the spirit of 1792; he is not under its influence. His reason approves of patriotic folly; his heart does not share it. There is in this beautiful spirit an inability to be moved, to vibrate with the same passions as the people. He admires Danton and would like, I believe, to possess his sympathetic verve; but, whatever he does, he mingles with the passions of the time only as a dilettante, with the reserve of a delicate observer, with a good will that is immediately cooled by a innate decency. His friend Paganel said that he distinguished himself from the men of his party by "his liberal education, his gentle affections, the tastes and the urbanity which reveal the beautiful forms of his body and the noble and brilliant features of his face". (1)

(1) Paganel, II, 247. Cf. Souvenirs du pere du Berryer, I, 176 “Herault de Sechelles was not forty years old in Year II. He was one of the most handsome men in France, tall, dark-faced, very noble; he had the manners of the court."

Indolent, selfish, he pleased everyone, even the fiercest sans-culottes, who forgave him his status as a ci-devant because of his modesty, his affability, and the pleasant turn he gave to the most revolutionary measures. Paganel, believing to praise him, judges him severely "He spared, he says, all opinions, and appropriately took, but only for his defense, the colors of each party." No, Herault was not a hypocrite (1), but an epicurean who tasted the flower of each opinion in turn, an eclectic to whom it seemed that all sides were right, but that there was more common sense and good faith in that of Danton. He loved life; but he did nothing ugly to avoid the guillotine. His laziness explains what is undulating in his politics, and Paganel was truer and shrewder when he wrote "laziness dominated over all his tastes, and the love of women over all his other passions. His speeches to the tribune, his work on the committees, were many victories he won over himself, were so many thefts from his pleasures. Herault lavished a life which promised him only brief pleasures. He was always ready to lose it. He felt that the genius of the Revolution would prevail over his precautions and his prudence; and each event warned him of his destiny. He spared himself the terrors of it, by filling with much existence the few days which were counted to him..."

(1) This reputation came to him from the contrast which was noticed between his political gravity and his private playfulness. Saint-Just would say hatefully in his report: "Herault was serious in the Convention, a buffoon elsewhere, and laughed incessantly to excuse himself for not saying anything". And Sieyes wrote in his intimate notes: "Brilliant with his success, H. de S., in his distraction, looked like a very happy funny fellow, who smiled at the irascibility of his thoughts" (Sainte-Beave, Causories du Lundi, t. V).”

Mais c’est la Herault tel que le fit la crise meme de la Terreur.* In 1792, he is still smiling and optimistic. It does not seem that the fall of the throne moved him. On the 17th of August, he traced with a rather bold hand the first draft of the revolutionary tribunal. His educated voice mingled with the great voice of Danton in the work of national excitement which marked, in August 1792, the dictatorship of the Cordeliers and Girondin patriots. His proclamation on the capture of Longwy (August 26) is not lacking in emphasis, any more than the noble letter he wrote on September 10, in his capacity as president, to the widow of the heroic Beaurepaire.

*This sentence has eluded my ability to translate.

In the first six months of the Convention where he represented the department of Seine-et-Oise, his speeches were rare. Elected president on the 2nd of November, he was sent with Simon, Gregoire and Jagot, to Mont Blanc. He was still there during the trial of the king, whom he condemned, it is said, by letter, but without saying to what penalty. The Convention liked to be presided over by this man of noble face and conciliatory manners. They put him at their head on two important occasions. It was he who presided temporarily, in place of Isnard, on the night of May 27 to 28, when the commission of the Twelve was broken up for the first time. On the 2nd of June, he replaced the tired Mallarme in the chair, and had the sad honor of guiding the Convention in the walk it took in the Tuileries Gardens and the Carousel, to make people believe that it was free and to save its dignity. It was therefore to the beautiful Herault that Hanriot made his crude reply "The people did not rise to listen to phrases, but to give orders."

He was made a deputy to the Committee of Public Safety on the 30th of May "to present constitutional basics". On the 10th of June he tabled the famous draft Constitution, improvised with so much haste. Circumstances alone made the short and dull report he read on this subject famous. There is only one original idea: the establishment of a national grand jury, to which each department would appoint a member, and whose function would be “to protect the citizens from the oppression of the Legislative Body and the Executive Council.” This article was rejected on the 16th of June at the request of Herault himself, who declared that he had always considered the institution of the a national jury to be very dangerous. This is the first time that a reporter has admitted to having an opinion other than expressed in their report. And yet, on the 24th of June, he proposed in his name an additional article: of the censorship of the people against its deputies and of its guarantee against the oppression of the legislative body. This system contained the single Chamber, counterbalanced it as a second Chamber, and tended to the same end as the "national jury". This bicameriste insistence of Herault served as a theme for the Robespierrist Jacobins to slander him. "We remember, Saint-Just would say in his report, that Herault was with disgust the mute witness of the work of those who drew up the plan of the Constitution, of which he skillfully made himself the shameless reporter." (1)

(1) Yet Couthon praised Herault’s attitude on the committee to the tribunal (26 brumaire an II).

Yet nothing would alter the favor he enjoyed at the Convention. Re-elected to the Committee of Public Safety, on the 17th of July he made this chimerical and Jacobin proposal, inspired by the beautiful dreams of Jean-Jacques, at which his skepticism must have made him smile to himself, "Citizens, you decreed this morning that the house of the traitor Buzot, in Evreux, would be razed. The Committee of Public Safety thought that it was necessary to celebrate the return of freedom in this city by a civic festival, in which six young virtuous republicans will be married to six young republicans chosen by an assembly of old men. The dowry of these young girls will be provided by the nation". The Convention adopted the proposal.

As we can see, his talented pen didn't hesitate to align with the ideas of others. There was even one instance where he acted as a rapporteur to interpret the underlying opposition of the Robespierrists to Danton's inclinations. On August 1st, 1793, Danton had proposed the establishment of the Committee of Public Safety as a provisional government, seeing in this unity of dictatorship the most effective means to defend the nation and the revolution. Hérault had too much political acumen and was too much a friend of Danton to hesitate in opposing the anarchic and disorganizing spirit alongside him. Nevertheless, he allowed himself to be influenced and presented a report against his master's proposal, contributing to its rejection on August 2.

On the 9th of August, by a singular favor, the Convention called him once more to the chair. They wanted her noblest and finest speaker to appear and speak in their name at the national holiday, which was held the next day in honor of the acceptance of the Constitution by the people. It was a new federation. Mixed with an immense retinue in which there were delegates from all the primary assemblies of the Republic, the Convention went slowly to the Champ de Mars, according to the program created by David, and stopped at six solemn stations, in front of the fountain of regeneration, in front of the triumphal arch erected in honor of the women of October 6, at the Place de la Revolution, at the Invalides, at the altar of the fatherland, and finally in front of the monument for the warriors who died for the fatherland, at the Champ de Mars.

Herault thus delivered six speeches which shone more by the high decency of the expressions than by the internal feeling. He moved the people, however, when he addressed the dead soldiers: "Ah! how happy you were! You died for your country, for a land dear to nature, loved by heaven; for a generous nation, which vowed a dedication to all feelings, to all virtues; for a Republic where places and rewards are no longer reserved for favor, as in other states, but assigned by esteem and by trust, you have therefore fulfilled your function as men and French men; you entered the tomb after having fulfilled the most glorious and desirable destiny that there is on earth; we will not outrage you with tears.”

The spirit of this festival, as reflected in the speeches of Herault de Sechelles, was entirely philosophical and naturalistic: "Oh Nature! exclaimed the friend of Danton, receive the expression of the eternal attachment of the French for your laws, and that these fertiles waters that spring from your breasts , that this pure drink that watered the first humans consecrate in this cup of fraternity and equality, the oaths that France makes to you on this day, the most beautiful that the sun has lit since it was suspended in the vastness of space.”

The inspiration of the six speeches of the president of the Convention had no deist, spiritualist character: it is the indirect negation of the ideas of Rousseau, the glorification of the positivist tendencies of Diderot. One can imagine what sadness, sincere and respectable, Robespierre must have experienced at this demonstration which already foresaw the Feast of Reason. I admit that he, who was born to preach, was envious of the role of great philosophical pontiff that the Dantonist Herault played that day. But it was a deeper feeling, a believer's pain that kindled in him that hatred, of which the harmless and amiable haranguer was to be the victim.

II

From then on, [Herault] felt himself watched by the symbolic and frightening eye which figured on the banners of the Jacobins, and he saw that Robespierre was watching him. He immediately darkened the color of his presidential speeches, but without carmagnole. Soon he had himself sent on a mission to Alsace, and he wrote, from Plotzheim, on 7 Frimaire Year II, in Jacobin style: "I have taken all possible measures to raise the department of Haut-Rhin to the level of the Republic. The public spirit was entirely corrupted there. Intelligence with the enemy, aristocracy, fanaticism, contempt for assignats, speculation and non-execution of the laws everywhere: I fought all these scourges, I suspended the department, created a departmental commission; I forced the popular Society to regenerate itself; I broke up the surveillance committees, the least of which were feuillants, and I replaced them with sans-culottes; I organized here the movement of terror which alone could consolidate the Republic: I have created a central committee of revolutionary activity, which requires the rapid action of all the authorities; a revolutionary force detached from the army and which covers the whole department; a revolutionary tribunal, finally, which will bring the country to its senses. "

Thus declaimed this delicate,* for reason as much as for personal prudence: we know, moreover, that he was not rigorous to the aristocrats of Alsace and that he did not shed a drop of blood (1).

*Aulard uses delicate here as a noun and I’m genuinely not sure what to translate it as. Possibly he means fop, or dandy, possibly someone who is tricky or someone who is tactful, as in a “delicate situation”. However, these are only my suggestions and possibly inaccurate.

(1) Cf. Hist. De la Revol. Fr. Dans le departement du Haut-Rhin, par Veron-Reville, 1865, in-8.

But, since the feast of August 10, Robespierre had been weaving a skillful plot against him and was trying to undermine the Dantonist party through him. His plan, indicated in his intimate notes (2), was to make Herault pass for a spy for foreign powers in the Committee of Public Safety.

(2) Le proces des dantonistes, par le docteur Robinet, pass.

The care which this serious spirit took to learn about all foreign affairs, his continual handling of diplomatic papers, might give some pretext to the accusation of communicating to the enemy the plans of the revolutionary government.

As it happened, like everyone else, he had had relations with Proly, bastard of the Prince of Kaunitz. On 26 Brumaire, Bourdon (de l'Oise) echoed these rumors, and dared to say to the Convention: "I denounce to you the ci-devant attorney general, the ci-devant noble Herault Sechelles, member of the Committee of Public Safety, and now commissioner in the Army of the Rhine, for his liaisons with Pereyra, Dubuisson and Proly." But the mine burst too soon: there was a general protest, and Couthon himself had the honesty to pay homage to the patriotism of Herault.

However, an incident had occurred in Alsace, which gave pretext to enormous calumnies. In Brumaire, a letter was intercepted at the outposts of General Michaud's army, who sent it to Saint-Just and Lebas, in Strasbourg. Signed: the Marquis de Saint-Hilaire, this letter tended to lead people to believe in intelligence between the people of Strasbourg and the enemy. The trick was crude. But how to make Saint-Just listen to reason? He immediately imprisoned part of the authorities of Strasbourg, and left in his post only the mayor Monet, and a deputy. A second letter arrived immediately, same signature, dated Colmar, 7 Frimaire Year II. The mayor was reproached for not having yet delivered the city, despite the money received: and the "marquis de Saint-Hilaire" added: "I have only been here (in Colmar) to talk to our friend Herault, who promised me everything."

On the spot, the representative Lemane, who had replaced Saint-Just and Lebas in Strasbourg, had the mayor arrested and, insultingly, sent the letter to Herault. [Herault] brought together the authorites and the popular Society of Colmar and, in a long speech, warns them against the machinations of the royalists, adding that he asks for his recall. It was, among the patriots of Alsace, a cry of pain, for Herault had made himself loved during his mission. But he was exasperated by Lemane's suspicion (1).

(1) Veron.Reville, pass.

Back at the Convention, he was all the more anxious to justify himself because his colleagues on the Committee displayed an insulting distrust of him. Young Robespierre claimed to have brought back from Toulon a document which proved the betrayal of his college: "Ah! how could I be vile enough, cried Herault, to abandon myself to criminal liaisons, I've only had one intimate friend since the age of six. Here he is! (pointing to Lepelletier's painting) Michel Lepelletier (2) O you, from whom I will never part, whose virtue is my model; you who were, like me, the butt of parliamentary hatred, happy martyr, I envy your glory. I would rush like you, for my country, to meet the daggers of freedom; but were it necessary that I were assassinated by the dagger of a Republican? - Here is my profession of faith. If having been thrown by the chance of birth into this caste that Lepelletier and I have not ceased to fight and despise is a crime which I must atone for: if I must, I still have the freedom to make new sacrifices; if a single member of this assembly sees me with suspicion at the Committee of Public Safety: if my prorogation, a source of continually recurring hassles, can harm the public thing before which I must disappear, then I pray the National Convention to accept my resignation from this Committee."

Not one of the accusers answered a word; the Convention not only passed on the agenda on the resignation of Herault, it ordered the printing of his speech (9 Nivose).

(2) assassinated Lepelletier, like Marat, had only admirers. In reality, Herault could not bear his vanity, and mocked him. This president, after 89, refused one day to sit at the same table as a simple prosecutor. We find the comic account of this incident as it took place at Herault’s house, in Oeuvres completes de Bellart, VI, 128.

This triumph did not stop the calumny. On 11 Nivose, Robespierre wrote in his own hand and had Collot, Billaud, Carnot and Barère sign this letter to Herault, "Citizen colleague, you had been denounced to the National Convention, which sent this denunciation back to us. We need to know if you persist in the resignation which you have, it is said, offered yesterday to the National Convention. We ask you to choose between perseverance in your resignation and a report of the Committee on the denunciation of which you have been the object: because we have here an indispensable duty to fulfill. We await your written repudiation today or tomorrow at the latest." These hypocritical threats did not intimidate Herault: he did not resign, and the Committee made no report.

The documents of young Robespierre, we have them: they are in the Archives. These are Spanish papers seized by one of the cruises on an enemy ship: the name of Herault is not even stated there. It is to be believed that the famous threatening letter had no other purpose than to force Herault to reveal himself, in the event that, as was hoped, he would be guilty of high treason. We can guess Robespierre's rage, his confusion, in the presence of this disappointment. His audacity knew no bounds: on 26 Ventose, Herault was arrested with Simond for complicity with the enemies of the Republic and relations with a citizen charged with emigration. The next day, on a summary report from Saint-Just, the Convention ratified this arrest, but did not decree it until 11 Germinal with the Dantonists.

In the meantime, the innocence of the defendant had come to light: the emigre whom he had been accused of hiding in his home was none other than his own secretary, Catus, appointed by the Committee of Public Safety and who, if he had crossed the border, had only been able to do so for a diplomatic mission. They were careful not to confront Herault with this. Moreover, Saint-Just's report of 11 Germinal did not make the slightest allusion to this grievance, which had been the official cause of the Dantonist's [Herault’s] arrest. It was not even brought up at the revolutionary tribunal. (1)

(1) Cf Robinet, 349-352.

In order to ruin Herault, it was necessary to resuscitate the old grievance formerly disavowed by Couthon, and to accuse him of complicity with the foreigner. Saint-Just dared to say: "Herault, who had placed himself at the head of diplomatic affairs, did everything possible to avert the projects of the government. Through him, the most secret deliberations of the Foreign Affairs Committee were communicated to the foreign governments. He had Dubuisson make several trips to Switzerland, to conspire there under the very seal of the Republic.”

It was not easy for the men of the revolutionary tribunal to color the condemnation of Herault who had exclaimed proudly, in the style of Danton: "I challenge you to present the slightest clue, the slightest adminicle possible, to make me only suspect of these communications." (2)

(2) Asked about his name and where he lives: "My name is Marie-Jean, a name not very prominent even among the saints. I sat in this room where I was hated by parliamentarians." Accused of complicity with Chabot and others, he confined himself to denying that he had knowledge of the affair. The court did not insist. But it must be recognized that Herault's notorious intimate relationship with the Abbe d'Espagnac made an unfavorable impression.

They then read to him the famous papers seized on a Spanish ship, two letters from Las Casas and Clemente de Campos, Ambassador of Spain, in which Herault was mentioned by name as an agent of the foreign country. The unfortunate replied: "The tenor of these letters, the perfidious style in which they are written, sufficiently indicates that they were fabricated abroad only to make patriots into suspect and to ruin them. And certainly, the trap is too grossly overstretched to let myself get caught up in it!" Now, and this is not the least infamy of the Robespierreists, the prosecution had not hesitated, in order to ruin Herault, to insert his name in the two Spanish letters, to fabricate all the passage where his accomplices were supposed to reveal his name. We have said it: these papers are in the Archives, M. Robinet published them, and there is no question of Herault’s involvement.