#andrey makarevich

Text

Strictly speaking, prior to “Time Machines” the band was called “The Kids,” and before that it wasn’t called anything at all, and everything didn’t happen right away. Really everything started when I heard the Beatles. I came home from school at the moment when my father was taping “A Hard Day’s Night,” borrowed from a neighbor, onto a little Philips tape recorder. I’d heard some kind of scraps of the Beatles even before that, at someone else’s house. A tiny fragment of their concert (about five seconds) could be heard on the television, thereby demonstrating how far bourgeois culture had fallen. In class a photo of the Beatles was passed around: re-photographed multiple times, worn and cracked like an ancient idol, enough that by now it was impossible to tell who in it was who, but magic still emanated from it.

So, I got home, and my father was taping “A Hard Day’s Night.” There was a sense that my entire life so far I’d been wearing cotton wool in my ears, and suddenly it had been taken out. I simply physically felt something within me churning, stirring, changing irrevocably. The Beatles days had started. Beatles were listened to from morning until evening. In the morning, before school, then immediately after and straight through until knock-off. On Sunday Beatles were listened to all day. Occasionally my Beatles-exhausted parents would kick me out onto the balcony together with the tape recorder, at which point I’d turn the volume up to full, so that everyone in the area would also listen to the Beatles.

(original Russian text beneath the cut)

[—from Было, есть, будет… / It Was, It Is, It Will Be..., Andrey Makarevich (founder and frontman of Russia’s oldest active rock band, Машина Времени / Mashina Vremini / Time Machine)]

Собственно, до «Машины времени» ансамбль назывался «The Kids», а до этого он вообще никак не назывался, и все происходило не сразу. По-настоящему все началось, когда я услышал битлов. Я вернулся из школы в тот момент, когда отец переписывал «Hard day’s night», взятый у соседа, на маленький магнитофон «Филипс». Какие-то обрывки битлов я слышал и раньше, где-то в гостях. Крохотный кусочек их концерта (секунд пять) звучал по телевидению, демонстрируя тем самым, как низко пала буржуазная культура. В классе по рукам ходила фотка битлов, несколько раз переснятая, затертая и потрескавшаяся, как старая икона, и уже невозможно было понять, кто на ней кто, но магия от нее исходила.

Так вот, я вернулся домой, и отец переписывал «Hard day’s night». Было чувство, что всю предыдущую жизнь я носил в ушах вату, а тут ее вдруг вынули. Я просто физически ощущал, как что-то внутри меня ворочается, двигается, меняется необратимо. Начались дни битлов. Битлы слушались с утра до вечера. Утром, перед школой, потом сразу после и вплоть до отбоя. В воскресенье битлы слушались весь день. Иногда измученные битлами родители выгоняли меня на балкон вместе с магнитофоном, и тогда я делал звук на полную, чтобы все вокруг тоже слушали битлов.

#i love this SO much#tiny soviet beatle fans passing around their one (1) beatle photo#the way he tells this story is so fun and colloquial in a way that is borderline impossible to translate but i have done my best#andrey makarevich#mashina vremeni#the beatles#андрей макаревич#машина времени#было есть будет…#it was it is it will be...#the beatles and the USSR

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

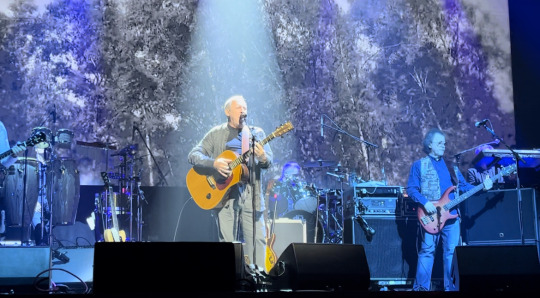

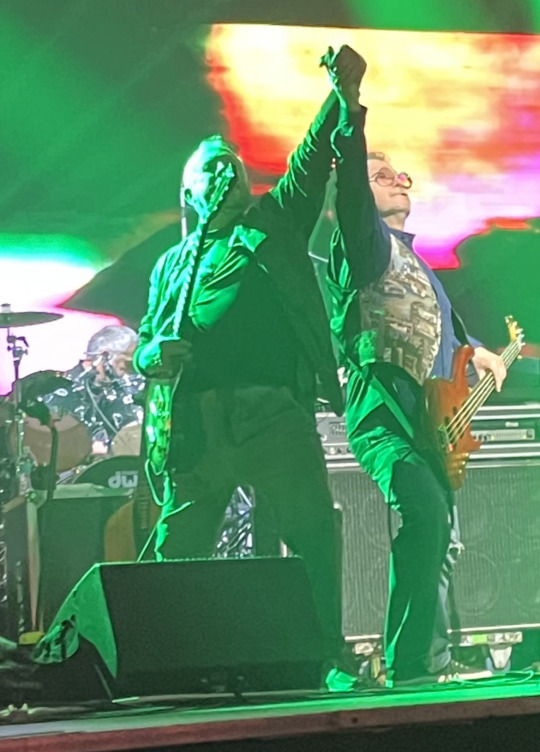

Ночь с Машиной Времени (2023)

#it was amazing!#they’re in their 70s and played a whole two hour set almost flawlessly#andrei makarevich is stupidly charming#and it was kind of surreal to spend an entire night surrounded by nothing but Russian#(I actually made small talk and understood about 90% of the concert so we’re going to call that a win)#also#Andrei and Alexander Kutikov are the cutest damn thing ever#or pretty darn close#I wish I had gotten more good footage of them#the way andrei looked at alexander when he was singing#and how alexander snuck up to give him a hug from behind during one of the songs#I’m just a sucker for old musicians that have been together for 50+ years#especially when they clearly still adore each other as much as those two#машина времени#андрей макаревич#александр кутиков#русский рок#keith richards#(died when I saw him)#marlon richards

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rock Monsters in Our Midst

Rock Monsters in Our Midst

“Monsters in our midst! The best urban fantasy”Source: Ozon.ru email newsletter, 7 July 2022

It’s hilarious how many people, back in the day, thought that Medvedev was a “liberal”:

Reviving Russia’s implicit nuclear threats, Dmitry Medvedev, a former president, has warned that the war in Ukraine might endanger the future of humanity. Mr Medvedev, now deputy chairman of Russia’s security…

View On WordPress

#Alexei Kortnev#Andrei Makarevich#Aquarium (Russian rock band)#Boris Grebenshchikov#Dmitry Medvedev#Khimki Forest#managed democracy#Okhta Center#Russian invasion of Ukraine#Russian rock music

0 notes

Text

Все отболит, и мудрый говорит —

Каждый костер когда-то догорит.

Ветер золу развеет без следа…

Но до тех пор, пока огонь горит,

Каждый его по своему хранит,

Если беда, и если холода…

Еще не все дорешено, еще не все разрешено,

Еще не все погасли краски дня.

Еще не жаль огня, судьба хранит меня…

/Андрей Макаревич

It'll wear off, and the wise man says.

Every fire will burn out one day.

The wind will scatter the ashes without a trace.

But as long as the fire burns

Every man keeps it in his own way,

If there's trouble, if there's cold.

There's more to be done, there's more to be solved,

The colours of the day have not yet gone out.

Not yet sorry for the fire, fate keeps me…

/Andrey Makarevich

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrey Makarevich

Со скрипом часы крутанутся назад, вот время и встало.

Вы 70 лет лизали им зад, вам этого мало.

Свободен в движеньях великий народ, что очень приятно.

Хлебнули свободы, гляди-ка - не мед, поедем обратно.

К чему мордоваться нам сквозь бурелом, где пни да коряги,

Мы смирно в знакомое стойло пойдем под красные флаги.

Не надо невиданных гор и морей, была бы охота:

Гораздо спокойней и как-то милей родное болото.

Поверим опять в доброту сволочей до новой до крови,

И выберем сами себе палачей - нам это не внове.

Отнимем, разделим, достанется всем, наполним корыто.

Под сводами храма устроим бассейн, теперь только крытый.

Не дай только Бог призывать нас к огню да на баррикады.

И я никого и ни в чем не виню, так всем нам и надо.

Не пью валидол, не бегу на вокзал, душа подустала.

Я просто с привычной тоской осознал, насколько нас мало.

Спустя 20 лет я опять осознал, насколько нас мало...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Andrey Makarevich, Yekaterina Golubeva

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Russian authorities have recently charged two female theater artists, Zhenya Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk, with “justifying terrorism.” While the allegations connected to the production of Petriychuk’s play, “Finist the Bright Falcon,” are highly controversial, what Russians talk about the most when talking about this case is why it is that Berkovich calls herself “rezhissyorka” — using a gendered suffix to convey that she is not a “director” but a female “directoress.” The Russian journaliste Shura Gulyaeva thinks that the debates about “feminitives” — feminine-gendered nouns in the Russian language — have nothing to do with grammar, and everything to do with ideology and politics. She explained her reasoning in her essay for Meduza’s newsletter Signal.

In this abridged English translation, we have deliberately followed the author’s decision to use “feminitives,” or feminine-gendered nouns, to describe women’s professions. Contemporary Russian feminists argue that feminitives help make women’s achievements and contributions to the professions more visible. What do you think? Send us your thoughts!

Why ‘directoress’?

In late May, a Moscow court dismissed the complaint filed by Zhenya Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk about their unlawful arrest. Both of them are being prosecuted for allegedly “justifying terrorism” through the rhetoric used in Berkovich’s production of Petriychuk’s play, Finist the Bright Falcon. In her play, Petriychuk tells the story of the hundreds (possibly even thousands) of Russian women who converted to radical Islam and married Syrian jihadists.

Zhenya Berkovich, who produced Petriychuk’s prize-winning play, is an ardent feminist who has for years insisted that others should call her not a rezhissyor (“director” in Russian) but a rezhissyorka, using a feminitive corresponding to “directoress” or something similar in English. As Finist the Bright Falcon and the criminal prosecution of the two female artists drew the attention of the press, excitement about Berkovich’s use of feminitives grew on Russian social media (as it does every time a feminitive makes headlines).

A typical comment reads like this: “The helpful media has informed our whole city and the rest of the world that Zhenya Berkovich is not a director who stages plays but just some chick.” “She’s not really a director, just a directoress,” ran the pejorative reading of the female professional’s preferred noun.

When, two weeks after the two women’s arrest, the legendary rock musician Andrey Makarevich joined the conversation, it was only to say: “You’ve got to be monstrously, criminally deaf to your mother tongue to come up with pearls like professorka, poetka, rezhissyorka… Are you completely bonkers, people?”

Why not just ‘director’?

Well, to begin with, Berkovich herself wants to be called a “directoress.” She even insists that others should refer to her this way. But not everyone is convinced.

Recent years’ heated debates on the use of feminitives in the Russian language have consolidated two mutually intolerant positions. People who side with inclusivity in the use of language are convinced that the use of feminitives raises awareness of the women’s achievements and contributions to the professional world, culture, and society. They think that feminitives can help correct social injustices with respect to women, including gender discrimination, income inequality (women in Russia earn 30–35 percent less than men), and the inequitable spread of domestic chores.

The opponents of feminitives, on the other hand, believe that this linguistic practice diminishes women and doesn’t recognize them as men’s equals. They also like to say that feminitives simply don’t sound “natural” in Russian.

In reality, starting at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, an increasing number of women in Russia (and elsewhere in the world) joined the workforce, offering their labor for hire. At the same time, a variety of new professions were just emerging and becoming a part of regular life, and women who joined them were frequently referred to with feminitives, as she-transcribers, -telegraphists, -aviators (or, rather, “aviatrixes”), and so forth.

Against this backdrop, the pre-revolutionary Russian feminist movement demanded suffrage rights for women. Unlike European suffragettes, Russian women were able to achieve this reform as early as 1917, when, following the February Revolution, the Provisional Government gave in to their demands and granted them the right to vote.

What to call women

At the same time, writes the Russian lingvistka Irina Fufayeva in her book What to Call Women, a linguistic undertow was normalizing the plural masculine form as the generic description of what people — both men and women — can do professionally. What’s a bit more surprising, though, is that this pattern of generalizing the masculine nouns as gender-neutral only became the norm by the 1960s. While, at the turn of the century, feminitives were preferred by women’s publications in 63 percent of cases, by the 1950s this number went down to 25 percent, dropping to 19 percent by the 1980s.

Marxism and Leninism treated women’s emancipation as a task of making them fully equal to men. Immediately after the October Revolution, Soviet propaganda portrayed women as strong workers and peasants. Some might even say they looked “masculine.” Still, even at that time, women were barred from certain occupations, considered too “dangerous” for all but men. By the late 1970s, the list of occupations closed to women grew to 431 different professions, obviating the feminitives that otherwise might have survived in the language.

Zhenya Berkovich is one of the contemporary Russian feminists who try to counter the generalization of the masculine gender. Besides, her determination to do this “definitely doesn’t hurt anyone,” she says.

The unconvinced

The question of using or not using feminitives is, first and foremost, a question of politics. This is, in fact, what bothers people who feel that their right to staying neutral is being taken away from them by the politicization of feminitives.

The linguist Alexander Pipersky thinks that, at the bottom of any linguistic debate there is inevitably a political creed. Anyone who takes part in the heated contemporary debates on language inevitably expresses a political position, sometimes in spite of themselves, or else has one attributed to them, sometimes against the grain of what they really think and feel. This is true not just for the arguments about gendered nouns, but also for other linguistic debates, like the proper way to refer to Ukraine. Either embracing or rejecting feminitives instantly broadcasts an ideological commitment, Pipersky believes: “Maybe you didn’t want to broadcast it. Maybe you’re just coming to a clinic to see a doctor and it’s not the place and time for politics.” When settings like that are newly politicized, it can bother people, Pipersky observes.

One of the arguments for the use of feminitives is that they highlight gender inequality through language and counter the invisibility of women’s work. But some people who oppose the wider use of feminitives think it’s irrelevant to focus on a professional’s gender, since gender falls outside of a person’s professional identity. Other critics of the practice believe that gender-neutral language helps protect women from discrimination. On these grounds, feminists in the English-speaking world have long advocated for gender neutrality in reference to work and professional occupations.

Nevertheless, since in the 1960s, sociolinguists have been noticing that using masculine nouns as neutral doesn’t automatically result in gender-neutral perceptions. When asked about their first associations with generic plural nouns like “writers,” “doctors,” “journalists,” or “experts,” both respondents and respondentesses in Romance in Germanic languages said that their first thought was about a group of men.

Nancy Fraser’s position

One of the critics of the rhetoric of recognition exemplified by the feminitives is the American philosopher Nancy Fraser. She does not believe that inclusive language is enough to solve society’s structural problems. “We are facing,” she writes, “a new constellation in the grammar of political claims-making — and one that is disturbing on two counts.”

First, this move from redistribution to recognition is occurring despite — or because of — an acceleration of economic globalization, at a time when an aggressively expanding capitalism is radically exacerbating economic inequality. In this context, questions of recognition are serving less to supplement, complicate and enrich redistributive struggles than to marginalize, eclipse and displace them.

Second, today’s recognition struggles are occurring at a moment of hugely increasing transcultural interaction and communication, when accelerated migration and global media flows are hybridizing and pluralizing cultural forms. Yet the routes such struggles take often serve not to promote respectful interaction within increasingly multicultural contexts, but to drastically simplify and reify group identities. They tend, rather, to encourage separatism, intolerance and chauvinism, patriarchalism and authoritarianism.

Does this mean that we should give up on the feminitives? I prefer to think that cultural shifts can complement our efforts towards economic justice.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Гражданин Израиля Андрей Макаревич был в Ереване во время атаки Ирана

Музыкант планирует в мае выступить в Молдавии и Прибалтике.

Подробнее https://7ooo.ru/group/2024/04/14/279-grazhdanin-izrailya-andrey-makarevich-byl-v-erevane-vo-vremya-ataki-irana-grss-299039702.html

0 notes

Text

"What can there be more sweet than the feeling of a free f[light] over the abyss? Nothing, I say!"

- Andrey Makarevich

0 notes

Text

“What lives in the minds of these Gavriks?”: Enraged Makarevich attacked the transgressors

“What lives in the minds of these Gavriks?”: Enraged Makarevich attacked the transgressors

The singer commented on the rumors about his business in Russia.

The leader of the Time Machine group, who moved to Israel, Andrei Makarevich, rarely makes contact.

In a new country, the musician tries himself in new creative professions. Either, red-faced from the heat, he hits a hammer in a blacksmith’s workshop, then shows off his new paintings.

In Russia, the singer left the company “Most…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Makarevich proved to the Russians that Putin is lying about the war in Ukraine

Makarevich proved to the Russians that Putin is lying about the war in Ukraine

The leader of the Russian group “Time Machine” still hopes that the citizens of the Russian Federation will finally see the light

Andrei Makarevich made the Russians think. / Photo: Collage: Today, Instagram

For the 18th day now, Russian invaders have been destroying towns and villages in Ukraine and killing civilians, including innocent children. The whole world condemns the culprit of the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Charlie Watts with Andrei Makarevich and Stas Namin or/или Чарли Уоттс, Андрей Макаревич, и Стас Намин (Moscow/Москва, 1998)

#this is such an amazing picture#andrei makarevich and charlie are two of my favorite musicians ever#and I never thought I’d see them together#the rolling stones#charlie watts#old married band#andrei makarevich#stas namin#машина времени#андрей макаревич#стас намин#русский рок#английски рок

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This is almost three months old now, but I'm still laughing about it.

(The Russian government forced independent Meduza media to {falsely} start all of its podcasts/articles with a warning that it acts as a foreign agent. They responded by having various staff members really ham it up while recording the warning, but also got this folk-music cover of it from Andrey Makarevich.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A six-twelve-story fourteen-entry brick residential building of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions. Designed in stages from 1939. Built in 1952 Architects involved in design: E.A. Levinson and I.I. Fomin., also A. E. Arkin, I.Z. Vilner and others. (client : Central Council VTsSPS- (All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions.)) (c) BACU Boris Berezovsky, Andrei Makarevich, actors Gleb Strizhenov, Vladimir Ivashov, academician Lev Ernst, and radio engineering scientist V.V. Shakhgildyan lived in the house. © B.A.C.U. @_BA_CU #_BA_CU #socrealism . . Add new sites: http://socheritage.com/add-locations-visitors/ . . Map location: http://socheritage.com/ . . Use the #SocialistRealism tag and your #SocHeritage shots will enter our selection and possibly be featured in our materials. Information collected from the public will be published on our website and included in an interactive map&data base under the name of the contributor. Collaborative profile tags: #SocArchitecture https://www.instagram.com/p/B9MZJiNnFgz/?igshid=ijbfd7rplkz1

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moscow’s central House of Books bookstore told its staff not to feature books by fifteen Russian authors listed in an internal memo, writes Ksenia Sobchak on her Bloody Lady Telegram channel. Two-thirds of that list are writers officially declared to be “foreign agents” by the Russian Justice Ministry.

Sobchak’s video explains that undesirable authors from the list cannot be shelved facing the customer, or featured on the “recommended” tables. “Be attentive and keep an eye on the displays; external organizations are inspecting us regularly,” the management advised the bookstore’s employees.

Here’s the list of authors whose book spines must be “stuck in a dark corner,” according to a House of Books staff member:

Boris Akunin

Natalia Baranova

Dmitry Bykov

Dmitry Glukhovsky

Vladimir Kara-Murza

Andrey Makarevich

Alexander Nevzorov

Leonid Parfyonov

Sergey Parkhomenko

Alexey Polyarinov

Yevgeny Ponasenkov

Ekaterina Shulman

Lyudmila Ulitskaya

Victor Vakhshtayn

Mikhail Zygar

The list notes its last revision date of October 15, but it’s unclear how long the House of Books has been limiting the display of certain authors.

One of the employees told a customer that Mikhail Zygar’s “All the Kremlin’s Men” and a number of other books by authors from the list was on sale, at 20 percent off, since the store is “getting rid of such authors.”

The House of Books made no formal comment on Sobchak’s report.

On October 21, the Russian novelist and playwright Boris Akunin wrote that his name had been removed from playbills at two theaters currently staging his plays — Moscow’s Russian Academic Youth Theater, and St. Petersburg’s Alexandrinsky theater. “I guess, next we’ll have books without the author’s name on the cover,” Akunin expects.

6 notes

·

View notes