#archaeology in Northern Greece

Note

Hi! I was reading your pinned post and realized that you were a professor at PSU! I’m currently an archaeology/ancient mediterranean studies student here, so that’s pretty cool. Anyways, I was just wondering if you knew about any on going research projects going on regarding Alexander the Great (or anything related). May it be digs, archival work, research- I’m super interested in this area of history and wanna get involved!! Sorry if this is a long shot but I wanted to ask. Thanks!

Hello, there, fellow Nittany Lion!*

Yes, I got my PhD from Penn State and taught there for Religious Studies and Classics both as a lecturer back in the late 1990s.

As for digs, there is one at Pella, but it's already filled out for this season. But keep an eye on it; I believe next season may be the last? I've got a former student who'll be there this year (and perhaps next).

Dig at Pella via AIA

Pella Urban Dynamics Project (U. Mich)

Keep an eye on the AIA (Archaeological Institute of America) site for other opportunities in Greece.

Also, message me if you would, so I have your actual name and email, and I'll keep you in mind if I hear of other opportunities. Let me know who you're studying with at PSU (Mark Munn?). Dr. Munn has digs of his own, and TBH, when it comes to experience with archaeology, any dig will give you some experience.

You should also look into summer programs offered through the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. They've had Macedonia-centric programs in the past. One, in fact, got tanked by Covid. So bookmark that site and, in fact, explore it thoroughly, if you're not already well familiar with the ASCSA.

(Spelling out some of these acronyms for those unlikely to recognize them.)

--------

* For the unintiated wondering what the heck a "Nittany" Lion is ... it's a (mountain) lion that lives on Mt. Nittany, of course. *snort* Penn State (located in State College, PA) nestles in "Happy Valley" which lies between (low) mountain ranges, and one of these is "Mount Nittany." It's actually an extremely lovely place, but also one of the few I had SERIOUS allergy problems for my entire 8 years there. Pollen counts are crazy.

#American School of Classical Studies in Athens#Pella Urban Dynamics Project (U. Mich)#Pella Greece#ancient Macedonia#ancient Pella#Alexander the Great#archaeology in Greece#archaeology in Northern Greece#Penn State#asks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of Cosmic Spirituality by Anton Sammut

youtube

#levels of consciousness#consciousness#cosmic connection#cosmic spirituality#interconnectedness#interconnectedworld#interconnection#gnosticism#gnostic gospels#gnostic teaching#gnosis#ancient history#ancient greece#ancient egypt#archaeology#ancient greek mythology#renaissance#middle east#northern india#jesus in india#india#medieval history#middle ages#classical greece#classical literature#classical studies#mythology#mysticism#mystical#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

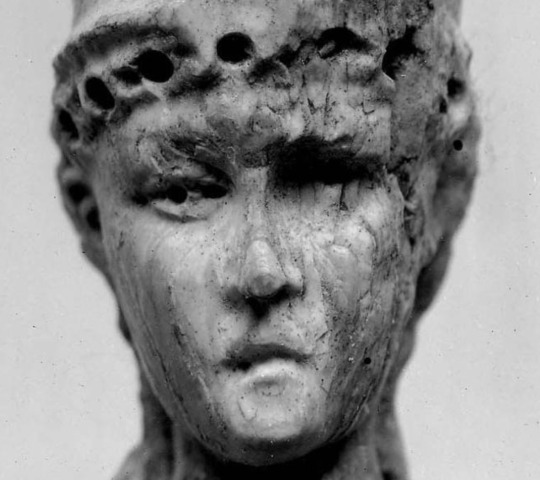

The Marble Head of Apollo Unearthed in Greece

The excavation, carried out by a group of students of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in the archaeological site of Philippi Kavala, brought to light important findings. Among other things, they discovered a rare head of Apollo dating back to the 2nd or early 3rd century AD.

The statue dates back to the 2nd or early 3rd century AD and it probably adorned an ancient fountain.

Natalia Poulos, Professor of Byzantine Archaeology, led the excavation, which included fifteen students from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (11 undergraduates, 2 master’s, and 2 PhD candidates), Assistant Docent Anastasios Tantsis, and Professor Emeritus of Byzantine Archaeology Aristotle Mendzo.

Archaeologists say, this year the excavation continued east of the southern main road (decumanus) at the point where it meets the northern axis of the city (the so-called “Egnatia”). The continuation of the marble-paved road was revealed, on the surface of which a coin (bronze phyllis) of the emperor Leo VI (886-912) was found, which helps to determine the duration of the road’s use. At the point where the two streets converge, a widening (square) seems to have been formed, dominated by a richly decorated building.

Archaeologists say evidence from last year’s excavations leads them to assume it was a fountain. The findings of this year’s research confirm this view and help them better understand its shape and function.

The research of 2022 brought to light part of the rich decoration of the fountain with the most impressive statue depicting Hercules as a boy with a young body.

The recent excavation (2023) revealed the head of another statue: it belongs to a figure of an ageneous man with a rich crown topped by a laurel leaf wreath. This beautiful head seems to belong to a statue of the god Apollo. Like the statue of Hercules, it dates from the 2nd or early 3rd century AD and probably adorned the fountain, which took its final form in the 8th to 9th centuries.

In classical Greek and Roman religion and mythology, Apollo is one of the Olympian gods. He is revered as a god of poetry, the Sun and light, healing and illness, music and dance, truth and prophecy, and archery, among other things.

Philip II, King of Macedon, founded the ancient city of Philippi in 356 BC on the site of the Thasian colony of Crenides near the Aegean Sea. The archaeological site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2016 for its outstanding Roman architecture, urban layout as a smaller reflection of Rome itself, and significance in early Christianity.

By Oguz Buyukyildirim.

#The Marble Head of Apollo Unearthed in Greece#Philippi Kavala#marble#marble statue#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient greece#greek history#greek art

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Zeus, they are stupid!

Back to our favorite mythomaniac, now suddenly proclaimed an expert on all things Greek/Olympic.

I had to howl. I mean, it's mandatory, at this point:

Calling all stations: there is NO Mount Olympia in Greece, you lost soul who thinks she's clever.

You should never have touched a sacred topic on this page: the Peloponnese. And you have finally managed to anger me. Seriously so: pursue at your own risk.

Archaia (that is 'Ancient' for you, Sinister Stupid Savant) Olympia, the birthplace of the Olympic Games, is one of my favorite places on Earth. It is situated in the North-West of the Peloponnese Peninsula, in the region of Ilia, beyond Corinth. That is Southern Greece for you, self-appointed Derailed Encyclopedia.

Mount Olympus, the cradle of the entire Greek Pantheon (that's all the Greek Gods, for you, Pretentious Idiot) is situated near the town of Litochoro, in Eastern Macedonia (as that guy, Alexander, you might have heard of him), in the region of Pieria. That is Northern Greece, for you, Arrogant Liar.

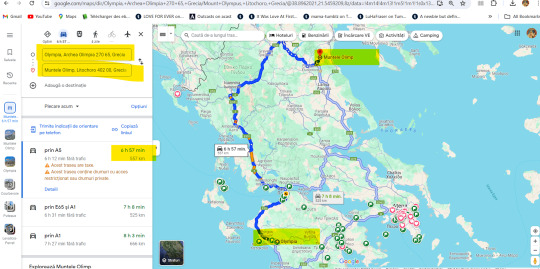

Distance between the two is very clear on a map:

557 kilometers, which means 347 miles. It would take me more than six hours to drive Zorba the Car from point A to point B and it took people like the ancient Olympic (not Olympian, you Faceless Pretentious Nobody) athletes probably more than one week.

Doubling the religious dimension of the athletic events, Archaia Olympia always functioned as Ancient Greece's UNGA (United Nations General Assembly, you Parochial Twat), with envoys from all the Greek city-states and overseas congregating there for the Games, but also (more often than not) to negotiate trade and/or peace agreements (Olympic truce, anyone?). This is perhaps why, unlike Nemea's stadium light cheerfulness, there's still a palpable sense of solemnity, today, in Olympia.

This cat, photographed by me in July 2022, in front of the Archaeological Museum of Olympia (I have already written about it in here: https://www.tumblr.com/sgiandubh/724219876757176320/a-stupid-shippers-guide-to-the-peloponnese-part) doesn't seem to give a damn about all of this, though:

Your credibility was already subzero, madam. I will soon be done with you, finally debunking your uninformed lies about S's copyright EUIPO trial. Even when you do not spew your gratuitous hatred, your overinflated ego and your foolishness betray the Aggressive Fraud that you are.

God, you're brainless. And your denseness is absolutely insulting, at this point. And to think there are people actually believing all the crap that you send into this world!

PS: torch is lit ahead of EACH and EVERY Olympic Games (Summer AND Winter), you Unspeakable Imbecile:

[Source: USA Today https://eu.usatoday.com/story/sports/olympics/2013/09/29/olympic-flame-relay-sochi-games/2890815/]

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir John Boardman

Archaeologist who became a leading authority on the history of Greek art, with a particular interest in gems and finger rings

As a student, John Boardman, who has died aged 96, was able to recite by heart texts in Attic Greek, the form of the language used in ancient Athens. But while studying classics at Magdalene College, Cambridge, he encountered two archaeologists whose work encouraged him to apply that flair to the study of classical objects: Charles Seltman showed him coins, and Robert Cook vases.

To these he added carved gems, sculpture and architecture, on all of which he became a leading authority, and the author of more than 30 books.

On graduating in 1948, he took Cook’s advice not to study for a doctorate, but to go to Greece and do some research there. At the British School in Athens for the next two years, as well as travelling to destinations including Crete and Smyrna, he worked in the depths of the Athens National Museum on vases from the island of Euboea (the modern Evvia).

The diagnostic pot shape that he identified enabled later archaeologists and historians to track the paths of Greeks and Greek culture to the east – Al Mina in Syria – and the west – Pithecusae, today’s Ischia, in the gulf of Naples – and at many points between.

The Greek islands and the diaspora around the Mediterranean came to be recurring themes in Boardman’s work. In 1964 he published two books, The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade, and Greek Art, both of which went on to further editions.

On his first visit to Greece he met Sheila Stanford, an artist, and after he had completed his national service in the Intelligence Corps (1950-52) they married in Britain. He then returned to the British School as assistant director (1952-55), and was given his own dig, on the island of Chios.

His party of excavators and helpers there included Michael Ventris, the architect who shortly aftewards announced his decipherment of the Linear B syllabic script as an early form of the Greek language, and Dilys Powell, the eventual film critic of the Sunday Times.

Back in Britain, Boardman served as an assistant keeper at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1955-59). Its Cast Gallery, containing plaster casts of some 900 Greek and Roman sculptures, became his preferred academic home base, and he published a catalogue of its Cretan collection (1961).

Working on another, private, collection of art objects in the 1990s gave him ideas about world art, its interconnections and aims. This led him to distinguish three main “belts”: a northern one, running from Siberia to North America, where nomads favoured small items, often depicting animals; an urban one, from China to central America, more given to monumental architecture; and a tropical one characterised by human forms, notably of ancestors. He explored these ideas in The World of Ancient Art (2006).

Other publications included Greek Gems and Finger Rings (1970); handbooks on Athenian black-figure and red-figure vases (1974 and 1975); a lecture series given at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and published as The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity (1994); Persia and the West (2000); The Archaeology of Nostalgia: How the Greeks Re-created Their Mythical Past (2002); numerous catalogues, particularly of gem collections, including the royal one at Windsor Castle; and excavation reports from Chios and from Tocra, in Libya.

After the Ashmolean appointment came university posts at Oxford, as reader in classical archaeology (1959-78) and then Lincoln professor of classical archaeology and art (1978-94). As professor emeritus, he continued to work from offices first in the Ashmolean and subsequently the classics faculty’s Ioannou Centre.

In 2020 he produced his autobiography, A Classical Archaeologist’s Life: The Story So Far. The last of its three parts focuses on a field of “minor” art that he showed could be anything but: Greek and Roman gems and finger rings. Called simply “Gems, Bob and Claudia”, it details the work that Boardman did first with the photographer Bob Wilkins and later an archivist of the Beazley Archive, in Oxford, Claudia Wagner. With her he co-authored Masterpieces in Miniature: Engraved Gems from Prehistory to the Present (2018).

Born in Ilford, Essex, John was the son of Clara (nee Wells), who had been a milliner’s assistant, and Arch (Frederick) Boardman, a clerk in the City. The family was not academic, but John was impressed by what he saw at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum when he visited them with his father, who died when John was 11.

While at Chigwell school, John experienced second world war aerial bombardment, of which he later had vivid memories. He found the study of Greek to be “magical”, and the school’s headteacher encouraged him to apply for a scholarship at his former Cambridge college.

Though his own career developed at a time when a doctorate was not obligatory, Boardman went on to supervise vast numbers of graduate students, scattered over several continents. He had an extraordinarily acute and retentive visual memory, was prodigiously efficient and well organised in his teaching – his lectures on Greek architecture and sculpture were a revelation – as in his research and writing, and welcomed the assistance provided by digital technology.

I first met him in his Ashmolean office, in 1969, keen for him to be my doctoral supervisor. Almost the first word he uttered was “Sparta”: not long before, he had published an account vastly improving on previous understanding of the sand, earth and relative dating of the artefacts found at the Artemis Orthia sanctuary site there. Like many others, I appreciated his meticulous standards of archaeological observation and historical interpretation.

Boardman once wrote that he felt more at home intellectually outside Oxford, indeed outside Britain, and he was involved with and recognised by institutions in Ireland, mainland Europe, the US and Australia. For almost three decades he was on the board of the Basel-based Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (1972-99).

His activities in Britain were still considerable. He edited the Journal of Hellenic Studies (1958-65) and was a delegate of the Oxford University Press (1979-89). At the Royal Academy in London from 1989 onwards he occupied what had originally been Edward Gibbon’s seat of professor of ancient history. He was made a fellow of the British Academy in 1969, and knighted in 1986.

While ready to express a view in serious academic controversies he was resolutely apolitical. Nonetheless, he took the view that Lord Elgin’s dubiously acquired collection of sculptures from the Parthenon and other structures in Athens purchased by the UK in 1816 should remain in its entirety under the curation of the British Museum Trustees.

He received a lot of support from the publishers Thames & Hudson, and his very last publication came in the month of his death, in their Pocket Perspectives series. John Boardman on the Parthenon is a lightly illustrated repackaging of the lively text he had composed to accompany the black and white photographs of David Finn in the same publisher’s The Parthenon and Its Sculptures (1985).

Sheila died in 2005. He is survived by their children, Julia and Mark.

🔔 John Boardman, archaeologist and classical art historian, born 20 August 1927; died 23 May 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

North frieze from the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi, 6th century BC

Delphic Archaeological Museum, Greece

The northern frieze depicts the Gigantomachy, the war between the Olympian gods and the Giants, who are depicted as enlarged hoplites. In this scene, the brother and sister team of Apollo and Artemis fire arrows towards a fleeing Giant who glances back over his shoulder, while a line of three other Giants advance from the right. Another rather unfortunate Giant can be seen behind the twin gods struggling to avoid being mauled by a lion.

📷: Egisto Sani

#ancient greece#classics#classical art#classical archaeology#delphi#apollo#artemis#greece#greek archaeology#wouldn't envy that guy

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The golden Bee Pendant (1800-1700 BC) in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum was found in a necropolis on northern Crete, Greece. The two bees are depositing a drop of honey into the granulated honeycomb held between their legs.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

you got your known Minoans and your unknown Minoans (part one)

(reposted, with edits, from Twitter)

Image: The famous “Ladies in Blue” Minoan fresco.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the Minoans. Everyone loves the Minoans, right?

(If you love the Minoans, you are not going to love this series of posts.)

Part One: The Case of the Very Victorian Goddess

Let’s start with a description of the pop culture perception of the Minoans: a peaceful ancient Greek culture with sophisticated, surprisingly modernist art, and extremely sophisticated technology like running water, who were lovers of beauty and peace.

So, I read Mysteries of the Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, and the Forging of History by Kenneth Lapatin. The author focuses on the (now, I believe, pretty thoroughly debunked) Boston Goddess, a supposedly Minoan ivory figurine of a snake-handling woman. She was an absolute SENSATION when she was first displayed.

Image: The Boston Goddess

Sir Arthur Evans, the most famous archaeologist of the Minoan civilization, dubbed her the "Minoan ambassadress to the New World." She made a 1967 issue of Mademoiselle's list of "art sensations" alongside Rembrandt, Picasso, and Rodin. The Museum's monthly bulletin for Dec 1914 proclaimed her an icon of a "wonderful prehistoric civilization which, after having lain submerged, like the lost Atlantis, for three thousand years, has been brought to light again..."

A comparison to Atlantis here is telling.

Victorian "race science" and Victorian occultism were inextricably linked, the latter demonstrating a passion for interpreting the myths of non-European cultures to reflect the ideas of the former. (Its descendants live on as Ancient Aliens theories, etc.) As archaeology became more popular and contact with ancient, sophisticated, and enduring civilizations such as those in India and China increased, white Europeans (especially the Brits) and Americans started to get uncomfortable.

So they started coming up with theories that hey, those people in the East who built all that amazing stuff, who were the "cradle of civilization," who invented the alphabet? They must have been taught by an even OLDER white civilization, now lost.

Image: The Palace of Atlantis by Lloyd K. Townsend, late 19th century, everyone is very Nordic-looking.

Hence the passion for stories about Atlantis and other lost continents. It just couldn't be true that those non-Europeans were building bigger, more sophisticated civilizations long before most (northern) European civilizations built recognizable cities at all.

That longing for proof of ancient European cultural superiority was in the air when excavations of Minoan sites began.

We must have The Oldest Masters

Now, back to the Boston Goddess. Lacey Caskey, writing for the museum, noted that the statuette's distinctive posture "seems not to have been an artistic convention, but a feature of the actual appearance of this aristocratic race."

This aristocratic race. Oof.

Lapatin observes, in the book, that "Minoan civilization was all the rage, for it seemed to provide Europeans with not only the roots of the ‘Golden Age of Greece,’ long considered the foundation of Western culture, but also a sophisticated early society in its own right, a rival to the 'Oriental' cultures of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia--known as the cradle of civilization..."

Victorian occultists, of course, tended to claim that their practices were derived from ancient Egyptian or Chaldean rituals. And again, even as they attempted to partake of the antiquity and sophistication of those cultures, they were also trying to prove that white people, or at least divine beings (rather than non-Europeans), built them. (It's always been a bit ironic to me that the Victorians clung to the idea of the superiority of Greece and Rome as the foundation for their ideas of the superiority of white people, while considering contemporary Greeks and Italians not fully white, but I digress.)

And lest you think that I'm hammering too hard on this point, some of the most prominent descriptions of Evans' finds praised the Minoan frescoes as "the Oldest Masters," and his work as proving the culture "bid fair rival to those of the Orient, and to give European Civilization an undreamed of antiquity."

It's hard to overstate the degree to which the archaeological motivation here was European insecurity.

High-Bred Beauty (and I Am Not, Alas, Describing a Horse)

And why was the Boston Goddess herself such a sensation? Her "exquisite characterization of fragile beauty," her "delicate, high-bred beauty." She is "demure," and "full of resolute charm." Professor Ernest Gardner, at Yale, described her head as "recall[ing] rather the sculptures of Gothic cathedrals of the thirteenth centuries."

Or, to be more explicit and just say the quiet part out loud, her face has also been described as "Anglo-Saxon," "European-looking," "Victorian," "Edwardian," and "Parisienne."

To understand what they’re talking about, let’s do a little compare and contrast. Here are some examples of faces from figurines that, to the best of our knowledge, are actually from Crete c. 1500-1200 BCE.

And here’s a close-up of the Boston Goddess’s face:

And here’s the face of a now-probably-debunked “Minoan” goddess at the Royal Ontario Museum (read more about her here):

To cut to the chase, eventually they did radiocarbon testing on the Boston Goddess, and the ivory was found to date from between 1420 and 1635 CE. (Not BCE. CE. As in the Renaissance.) A similar figurine, the Seattle Boy God, is made from ivory that's about 500 years old. That in itself is pretty fascinating! They were using old ivory for the forgeries.

What do these proven and suspected fakes have in common? Well, among other things, their very Victorian facial features: inset eyes, small pouty mouths, delicate noses.

Spoiler for where I’m going with this: There are reasons why the Minoans were such an archeological craze, and those reasons are highly political. Because of the ways in which a very specific agenda shaped it, fakes that showed people what they wanted to see were accepted as real (and in some cases, are still sort of accepted as real), and we can't trust a lot of what we supposedly "know."

In Part 2: Bagging On Sir Arthur Evans Forever.

#archaeology#atlantis#minos#crete#minoans#arthur evans#white supremacist archaeology#snake goddess#art forgery#minoan

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

"From Southern Greece to northern Russia, people living in agrarian communities have long believed in “dancing goddesses,” mystical female spirits who spend their nights and days dancing in the fields and forests. In The Dancing Goddesses, archaeologist, linguist, and lifelong folkdancer Elizabeth Wayland Barber follows the trail of these spirit maidens―long associated with fertility, marriage customs, and domestic pursuits―from their early appearance in traditional folktales and harvest rituals to their more recent incarnations in fairytales and present-day dance. Illustrated with photographs, maps, and line drawings, the result is a brilliantly original work that stands at the intersection of archaeology and folk traditions―at once a rich portrait of our rich agrarian ancestry and an enchanting reminder of the human need to dance."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

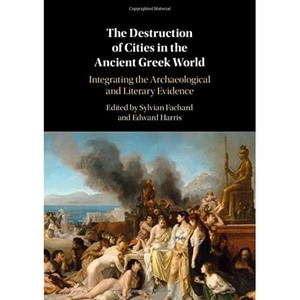

S. Fachard-E.M. Harris (editors) The Destruction of Cities in the Ancient Greek World. Integrating the Archaeological and Literary Evidence, Cambridge University Press 2021

Table of Contents

1. Introduction: destruction, survival, and recovery in the ancient Greek world Sylvian Fachard and Edward M. Harris

2. Destruction, abandon, reoccupation: What Microstratigraphy and Micromorphology tell us Panagiotis Karkanas

3. Miletus after the disaster of 494 B.C.: Refoundation or recovery? Hans Lohmann

4. The Persian destruction of Athens: Sources and Archaeology John Mckesson Camp

5. The Carthaginian conquest and destruction of Selinus in 409 B.C.: Diodorus and archaeology Clemente Marconi

6. Ancient Methone (354 B.C.): Destruction and abandonment Manthos Bessios, Athina Athanassiadou, and Konstantinos Noulas

7. The destruction of cities in Northern Greece during the Classical and Hellenistic periods: The numismatic evidence Christos Gatzolis and Selene Psoma

8. Eretria's “destructions” during the Hellenistic period and their impact on the city's development Guy Ackermann (translated by E. M. Harris and S. Fachard)

9. Rhodes ca. 227 B.C.: Destruction and recovery Alain Bresson

10. Destruction, survival and colonisation: Effects of the Roman arrival to Epirus Björn Forsén

11. From the destruction of Corinth to Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis Charles K. Williams, Nancy Bookidis, Kathleen W. Slane, and with Stephen Tracy

12. Sulla and the siege of Athens: Reconsidering crisis, survival, and recovery in the 1st B.C. Dylan K. Rogers

13. The Herulian invasion in Athens (A.D 267): The archaeological evidence Lamprini Chioti

14. Epilogue. The survival of cities after military devastation: Comparing the classical Greek and Roman experience John Bintliff

15. Appendix. The destruction and survival of cities.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

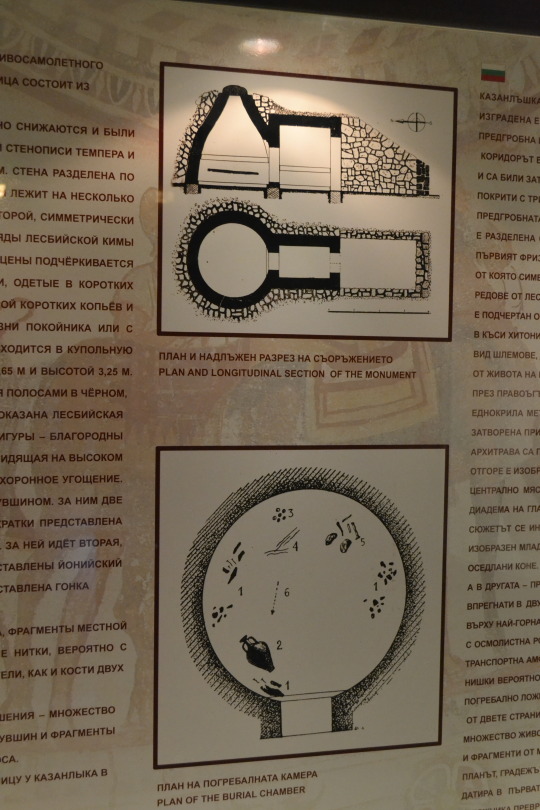

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greece Reopens the 2,400-Year-Old Palace Where Alexander the Great Was Crowned

The 2,300-year-old Palace of Aigai—the largest building in classical Greece—had been under renovation for 16 years.

On the day he was crowned king of Macedonia, Alexander the Great stood atop the intricately patterned marble floors of the Palace of Aigai. This week, the historic palace finally opened to the public after a 16-year-long restoration, report Derek Gatopoulos and Costas Kantouris of the Associated Press (AP).

At 160,000 square feet, the Palace of Aigai was classical Greece’s largest structure. Built primarily by Alexander’s father, Phillip II, in the fourth century B.C.E., it was the home of the Argead dynasty, ancient Macedonia’s ruling family. It was destroyed by the Romans in 148 B.C.E. and endured a subsequent series of lootings. Renovating and excavating this sprawling monument was a serious undertaking, costing over 20 million euros ($22 million).

The Greek government was able to maintain the “general appearance” of the site amid careful alterations to the monument’s towering marble columns, delicate mosaics and textured flooring, according to Xiaofei Xu and Chris Liakos. The palace once featured large column-lined courtyards, worship sites and expansive banquet halls, and its restoration presented a “three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle,” per the AP. Archaeologists solved it by combining stones from the structure’s ruins with replica parts to reproduce the original structures.

Archaeologist Angeliki Kottaridi started working on the renovation efforts as a university student. Overseeing the project’s progress over many years and contributing to its excavation and reconstruction, Kottardi became a leading figure in the project.

“What you discover is stones scattered in the dirt, and pieces of mosaics here and there,” Kottaridi told state television before an opening ceremony on Friday, per the AP. “Then you have to assemble things, and that’s the real joy of the researcher.”

The Palace of Aigai is located in northern Greece between what are now the towns of Palatitsia and Vergina. Its reopening builds on discoveries made in the late 1970s by Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos, who unearthed a cluster of royal Macedonian artifacts, including gold and silver ceremonial weapons and armor, and burials, one of which is thought to contain Phillip’s remains. The palace and its neighboring tombs are now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Deeming it “among the most important archaeological sites in Europe,” UNESCO writes that the Palace of Aigai “represents an exceptional testimony to a significant development in European civilization, at the transition from the classical city state to the imperial structure of the Hellenistic and Roman periods.”

As the site of the first capital of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia, the Palace of Aigai signifies the onset of Alexander’s rule, which would stretch from Asia to the Middle East, and provides a crucial window into Macedonian culture.

“The importance of such monuments transcends local boundaries, becoming property of all humanity,” said Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Greece’s prime minister, at the inauguration event, per CNN. “And we as the custodians of this precious cultural heritage, we must protect it, highlight it, promote it and at the same time expand the horizons revealed by each new facet.”

By Catherine Duncan.

#Greece Reopens the 2400-Year-Old Palace Where Alexander the Great Was Crowned#Palace of Aigai#Argead dynasty#Phillip II#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient macedonia#ancient greece#greek history#greek art

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Places to Go for Vacation

Introduction

Planning a vacation is an exciting endeavor, and the world is brimming with remarkable destinations to explore. Whether you're seeking natural beauty, cultural richness, adventure, or relaxation, there's a perfect vacation spot for everyone. In this article, we'll take a tour of some of the top places to go for vacation, each offering a unique and unforgettable experience.

1. Bali, Indonesia

Known as the "Island of the Gods," Bali is a tropical paradise with stunning beaches, lush rainforests, and vibrant culture. Visitors can explore ancient temples, enjoy water sports, and savor Balinese cuisine. Don't miss the tranquil rice terraces and the energetic nightlife in Seminyak.

2. Santorini, Greece

Santorini, an enchanting island in the Aegean Sea, is famous for its iconic white-washed buildings, crystal-clear waters, and dramatic sunsets. It's a romantic destination with breathtaking views, ancient ruins, and delicious Mediterranean cuisine.

3. Kyoto, Japan

For a taste of Japanese culture and history, Kyoto is a must-visit. This city is renowned for its traditional tea houses, stunning cherry blossoms in spring, and beautiful temples. Stroll through bamboo forests, participate in tea ceremonies, and admire the art of the geisha.

4. Bora Bora, French Polynesia

Bora Bora is synonymous with paradise. Its turquoise lagoons, overwater bungalows, and coral reefs make it a dream destination for honeymooners and water enthusiasts. Snorkeling, scuba diving, and relaxation are the order of the day.

5. Tuscany, Italy

Tuscany's rolling hills, historic cities, and delectable cuisine make it a favorite European destination. Explore the charming streets of Florence, sample world-class wines in Chianti, and savor the simple pleasures of life in the Tuscan countryside.

6. Maldives

The Maldives, a collection of over a thousand coral islands, is a tropical haven with luxury resorts and stunning marine life. It's an ideal spot for beach lovers, honeymooners, and those seeking seclusion in paradise.

7. Machu Picchu, Peru

Machu Picchu, the ancient Inca citadel nestled in the Andes Mountains, is a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the world's most iconic travel destinations. Hike the Inca Trail or take the train to witness this archaeological wonder.

8. New York City, USA

For the bustling urban experience, New York City is a top choice. Explore iconic landmarks like Times Square, Central Park, and the Statue of Liberty. The city offers a vibrant arts scene, diverse cuisine, and endless entertainment.

9. Cape Town, South Africa

Cape Town is a city of breathtaking beauty, nestled between Table Mountain and the Atlantic Ocean. Explore vibrant neighborhoods, visit the Cape of Good Hope, and savor South African wines in the surrounding vineyards.

10. Patagonia, Argentina and Chile

Patagonia offers awe-inspiring natural beauty with its glaciers, mountains, and remote wilderness. It's a dream destination for hikers, nature lovers, and wildlife enthusiasts.

11. Iceland

Iceland's dramatic landscapes include geysers, waterfalls, volcanoes, and geothermal springs. The Blue Lagoon, the Golden Circle, and the Northern Lights are just a few of the attractions that make Iceland a unique vacation destination.

12. Marrakech, Morocco

Marrakech is a bustling and exotic city in North Africa. Explore the bustling souks, visit the historic medina, and relax in stunning riads. Marrakech offers a blend of tradition and modernity.

13. Sydney, Australia

Sydney, with its iconic Opera House and Sydney Harbour Bridge, is a vibrant city with beautiful beaches, world-class dining, and a variety of cultural attractions. The city's coastal charm and natural beauty are hard to resist.

14. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro is known for its lively Carnival, stunning beaches, and iconic Christ the Redeemer statue. Enjoy samba music, relax on Copacabana Beach, and explore the lush Tijuca Forest.

15. Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul straddles Europe and Asia, offering a rich blend of cultures, history, and architecture. Visit the Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque, and the Grand Bazaar for an unforgettable experience.

Conclusion

The world is a treasure trove of vacation destinations, each offering a unique blend of natural beauty, culture, history, and adventure. Whether you're drawn to tropical paradises, ancient cities, or remote wilderness, there's a place for every traveler to discover and savor. When planning your next vacation, consider the experiences that ignite your wanderlust and create memories that will last a lifetime.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Hera’s military concerns at Perachora are referred to by horse figurines, horse trappings, statuettes of mounted warriors, and weapons. In addition, there is a figurine of a woman on a horse. Since she might have held a child, the statuette possibly refers to Hera’s concern with offspring, which provides the foundation for the armed forces and secures their stability. The location of the Heraion at the border of the Corinthian territory suggests that Hera was also regarded as responsible for the protection of its sovereignty, which is a further aspect of her military concerns.

Mounted warriors also occur at the Argive and Tirynthian Heraia. Further evidence for Hera’s military concerns at Tiryns is provided by terracotta shields. These do not occur at the Argive Heraion where a statuette of a riding woman was found, which might have had a similar function as the one from Perachora. However, the fact that Pausanias refers to a shield that hung in the pronaos of the classical temple shows that weapons were dedicated to Hera so that their absence from the archaeological record does not prove their nonexistence at the Heraion. Here, Hera’s military concerns probably derive from her function as protectress of both offspring and the territory of Argos. Since the Tirynthian Heraion is located on the upper citadel, Hera at Tiryns, on the other hand, was worshipped as protectress of the city and its inhabitants.

The Hera sanctuaries at Poseidonia - Paestum are similar to each other as both of them received statuettes of seated women with horses, images of armed women, and weapons. As a peculiarity, there are horse trappings and a skeleton of a horse at Foce del Sele. Although both sanctuaries received similar votive offerings, they probably relate to different aspects of Hera’s military concerns. The location of the Heraion at the southern bank of the river Sele, which marks the northern border of the colony’s territory, suggests that they relate to her function as protectress of Poseidonia’s sovereignty. In this regard, it is comparable to the Heraia at Perachora, Argos, and the one on Samos. The placement of the urban Heraion in the immediate vicinity of the city’s political centre, on the other hand, suggests that its votives relate to Hera’s function as city-protectress. Since both Hera sanctuaries provide evidence for pregnancy and childbirth, the reason for the dedication of such votives probably also derives from Hera’s function as protectress of offspring, considering that it provides the basis of the military force.

At the Samian Heraion, the variety and number of dedications which refer to Hera’s military concerns show that it must have been an important cult aspect. Horse figurines, horse trappings, and weapons occur frequently. Furthermore, there are ship models and dedications for naval victories which, except for Perachora, have not been found in any of the other Hera sanctuaries. They indicate that Hera was worshipped as protectress of the Samian fleet, which is a local peculiarity that demonstrates that the Heraia are embedded in the social and political situation of the city-states they belong to. Like at the other Heraia, Hera’s military concerns probably also derive from her function as protectress of pregnancy and childbirth since there is a statuette of a riding woman with a child in her arms."

- The Significance of Votive Offerings in Selected Hera Sanctuaries in the Peloponnese, Ionia and Western Greece by Jens David Baumbach

#hera#heraion#heraia#votives#votive offerings#perachora#Tiryns#argos#argolid#paestum#samos#argive heraion#samian heraion#quotes#excerpts

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biblical Archaeology Lesson 02: The New Testament

In our previous study, we examined ten archaeological discoveries that demonstrated the historical accuracy of the Old Testament. Today, we will examine ten archaeological finds with relevance to the New Testament.

Let’s read together Acts 13:6-12.

Sergius Paulus inscription

A Roman proconsul was a governor or military commander of a province. Sergius was the proconsul of Cyprus under the reign of Claudius Caesar from 45 to 50 AD. A stone with a Greek inscription dating to 54 AD was found in northern Cypress. The inscription referred to an event that happened earlier than 54 AD and referenced a “proconsul Paulus.” It is very likely this inscription is speaking of the same Sergius Paulus who encountered Paul the Apostle in Paphos.

Let’s read together John 9:1-7.

Pool of Siloam

The pool of Siloam was a freshwater reservoir in the time of Jesus. It was at this pool where Jesus miraculously cured a man of his blindness. It was accidentally discovered in 2004 by workers doing sewage pipe maintenance in the old city of Jerusalem. The discovery of the pool of Siloam shows that the book of John is not a purely theological book. Rather, it is grounded in history.

Let’s read together Acts 19:22; Romans 16:23; and 2 Timothy 4:20..

Erastus inscription

A stone with a Latin inscription dating around 50 AD was found in Corinth. The inscription translated in English reads: “Erastus in return for hisa aedileship laid (the pavement) at his own expense.” (An aedile was a Roman magistrate in charge of public works.) This discovery points to the historicity of Erastus, an evangelist and a socially elite individual mentioned by Paul the Apostle.

Let’s read together Matthew 26:3 and John 18:13-14.

Caiaphas ossuary

An ossuary with the engraving “Joseph son of Caiaphas” was discovered in a burial cave in the old city of Jerusalem. The skeletal remains inside the ossuary were of a 50 year old. This ossuary is very likely the remains of the priest who presided over the trial of Jesus.

Let’s read together Acts 21:27-30 and Ephesians 2:14.

Temple warning inscription

The Jewish historian Josephus wrote of a partition in the Jewish temple with a stone inscription forbidding foreigners from entering the temple upon penalty of death. A complete stone inscription with such a warning was found in Jerusalem in 1871. Interestingly, there were traces of red paint in the stone inscription, meaning it was meant to be very visible to people.

This inscription correlates with the story in Acts 21:28-30 where the Jews accused Paul of bringing in Greeks into the temple and defiling it. Paul may have also referred to this barrier in Ephesians 2:14.

Let’s read together Leviticus 23:24 and Matthew 24:1-2.

Trumpeting place inscription

A stone with the Hebrew inscription “to the place of trumpeting” was discovered in Jerusalem, dating to the first century. It is thought this stone was atop the southwest corner of the temple of Jerusalem before it was cast down. This is evidence for the existence of the second temple of Jerusalem, which was destroyed in 70 AD.

Let’s read together Matthew 28:11-13.

Nazareth inscription

This stone inscription contains an edict from Caesar proclaiming the death penalty for those caught stealing bodies from tombs. This is a rather unusual decree as grave robbers normally would steal items from tombs, but not the bodies.

It is quite possible this inscription was written by Claudius Caesar in response to hearing Christians sharing the story of Jesus’ resurrection. Claudius would have considered Christians a dangerous anti-Roman movement.

Let’s read together Acts 18:12.

Gallio inscription

This is a collection of nine stone fragments of a letter written by Claudius Caesar in 52 AD. The Gallio inscription was found in Delphi, Greece, which is about 50 miles northwest of Corinth. This inscription makes mention of Junius Gallio being proconsul of Achaia. Gallio only served as proconsul from 51 to 52 AD. The Gallio inscription is a fixed marker that allows us to date Paul’s ministry.

Let’s read together Matthew 27:1-24 and Mark 15:1-15.

Pilate stone

Pontius Pilate was a Roman prefect governing Judea from 26 to 34 AD. He is mentioned by the historians Josephus, Tacitus, and Philo in addition to the Gospels. The Pilate stone confirms the historicity of Pontius Pilate.

Let’s read together John 18:31-33.

P52 fragment of John 18:31-33

This is a papyrus fragment dating to 125 to 175 AD. This is the oldest known fragment of the New Testament Gospels. The significance of this fragment is that it was written within 100 years of the events of the Gospels.

There has not been an archaeological find that contradicts the Bible. The historical events recorded in the New Testament are factual. The archaeological discoveries mentioned in this lesson should increase our trust in the Bible.

Friend, will you trust what the Bible says about historical things? Will you trust what the Bible says about spiritual things?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

30 Destinations to Tick Off Your Bucket List

1. Kyoto, Japan:

Why: A blend of ancient traditions and modern amenities, Kyoto offers stunning temples, serene gardens, and delicious cuisine.

Must-see: Arashiyama Bamboo Forest, Kiyomizu-dera Temple, Gion district.

2. Santorini, Greece:

Why: With its iconic white-washed buildings, blue-domed churches, and breathtaking sunsets, Santorini is a dream destination.

Must-see: Oia village, Akrotiri archaeological site, Santorini Wine Museum.

3. Iceland:

Why: From glaciers and geysers to the Northern Lights, Iceland offers a unique and unforgettable experience.

Must-see: Blue Lagoon, Golden Circle, Vatnajökull National Park.

4. Machu Picchu, Peru:

Why: A UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the Seven Wonders of the World, Machu Picchu is a marvel of ancient Inca engineering.

Must-see: Inca Trail, Huayna Picchu, Sun Gate.

5. Galapagos Islands, Ecuador:

Why: Home to a unique ecosystem of endemic species, the Galapagos Islands offer unparalleled wildlife encounters.

Must-see: Isabela Island, Santa Cruz Island, Charles Darwin Research Station.

6. Taj Mahal, India:

Why: A symbol of love and loss, the Taj Mahal is a breathtaking mausoleum and UNESCO World Heritage site.

Must-see: Agra Fort, Fatehpur Sikri.

7. Great Barrier Reef, Australia:

Why: The world's largest coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef offers incredible snorkeling and diving opportunities.

Must-see: Whitsunday Islands, Cairns, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

8. Paris, France:

Why: A city of romance, art, and culture, Paris is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Eiffel Tower, Louvre Museum, Notre-Dame Cathedral.

9. Venice, Italy:

Why: With its canals, gondolas, and stunning architecture, Venice is a magical city.

Must-see: St. Mark's Square, Rialto Bridge, Doge's Palace.

10. New York City, USA:

Why: A bustling metropolis with endless things to see and do, New York City is a must-visit for any traveler.

Must-see: Times Square, Central Park, Statue of Liberty.

11. Angkor Wat, Cambodia:

Why: A stunning temple complex and UNESCO World Heritage site, Angkor Wat is a must-see for history buffs and culture enthusiasts.

Must-see: Bayon Temple, Ta Prohm, Preah Khan.

12. Petra, Jordan:

Why: A hidden city carved into the sandstone cliffs, Petra is a marvel of ancient architecture.

Must-see: Treasury, Monastery, Siq.

13. Great Wall of China:

Why: One of the Seven Wonders of the World, the Great Wall of China is a symbol of Chinese history and culture.

Must-see: Mutianyu section, Badaling section, Simatai section.

14. Cape Town, South Africa:

Why: With its stunning natural beauty, vibrant culture, and delicious food, Cape Town is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Table Mountain, Cape of Good Hope, Robben Island.

15. Reykjavik, Iceland:

Why: The capital of Iceland offers a unique blend of Scandinavian charm and Icelandic culture.

Must-see: Hallgrímskirkja church, Harpa concert hall, Perlan.

16. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil:

Why: Known for its beautiful beaches, vibrant nightlife, and iconic landmarks, Rio de Janeiro is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Copacabana Beach, Ipanema Beach, Christ the Redeemer statue.

17. Amsterdam, Netherlands:

Why: A charming city with canals, bicycles, and a relaxed atmosphere, Amsterdam is a popular tourist destination.

Must-see: Anne Frank House, Rijksmuseum, Van Gogh Museum.

18. Barcelona, Spain:

Why: A vibrant city with stunning architecture, delicious food, and a lively atmosphere, Barcelona is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Sagrada Família, Park Güell, La Rambla.

19. Sydney, Australia:

Why: A beautiful city with iconic landmarks, stunning beaches, and a vibrant culture, Sydney is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Sydney Opera House, Bondi Beach, Harbour Bridge.

20. Dubai, United Arab Emirates:

Why: A futuristic city with towering skyscrapers, luxurious hotels, and a vibrant nightlife, Dubai is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Burj Khalifa, Palm Jumeirah, Dubai Mall.

21. Buenos Aires, Argentina:

Why: A vibrant city with a European flair, Buenos Aires is known for its tango, delicious food, and friendly people.

Must-see: Recoleta Cemetery, Caminito, La Boca neighborhood.

22. Prague, Czech Republic:

Why: A stunning city with beautiful architecture, cobblestone streets, and a rich history, Prague is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Charles Bridge, Prague Castle, Old Town Square.

23. Kyoto, Japan:

Why: A blend of ancient traditions and modern amenities, Kyoto offers stunning temples, serene gardens, and delicious cuisine.

Must-see: Arashiyama Bamboo Forest, Kiyomizu-dera Temple, Gion district.

24. Santorini, Greece:

Why: With its iconic white-washed buildings, blue-domed churches, and breathtaking sunsets, Santorini is a dream destination.

Must-see: Oia village, Akrotiri archaeological site, Santorini Wine Museum.

25. Iceland:

Why: From glaciers and geysers to the Northern Lights, Iceland offers a unique and unforgettable experience.

Must-see: Blue Lagoon, Golden Circle, Vatnajökull National Park.

26. Machu Picchu, Peru:

Why: A UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the Seven Wonders of the World, Machu Picchu is a marvel of ancient Inca engineering.

Must-see: Inca Trail, Huayna Picchu, Sun Gate.

27. Galapagos Islands, Ecuador:

Why: Home to a unique ecosystem of endemic species, the Galapagos Islands offer unparalleled wildlife encounters.

Must-see: Isabela Island, Santa Cruz Island, Charles Darwin Research Station.

28. Taj Mahal, India:

Why: A symbol of love and loss, the Taj Mahal is a breathtaking mausoleum and UNESCO World Heritage site.

Must-see: Agra Fort, Fatehpur Sikri.

29. Great Barrier Reef, Australia:

Why: The world's largest coral reef system, the Great Barrier Reef offers incredible snorkeling and diving opportunities.

Must-see: Whitsunday Islands, Cairns, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

30. Paris, France:

Why: A city of romance, art, and culture, Paris is a must-visit destination.

Must-see: Eiffel Tower, Louvre Museum, Notre-Dame Cathedral.

#travel#travel destinations#bucket list#tourism#adventure#exploration#iceland#machupicchu#taj mahal#great barrier reef#Paris#venice#new york#Petra#great wall of china#Dubai#prague#travel the world#must see places

0 notes