#arnold of brescia

Text

The Restoration of the Roman Republic ... in the Middle Ages? The Forgotten Commune of Rome

Today it seems men often have Rome on their minds with Tik Toks and polls indicating that men often think about Rome on a daily basis. I'm assuming that most of these thoughts revolve around the Roman Empire, lesser so the Roman republic, some the Eastern Roman (Byzantine Empire), and few think about the Roman monarchy. However I guarantee that almost no one thinks about the medieval Roman Republic known as the Commune of Rome.

In the 12th century central Italy was directly ruled by the Pope through the Papal States. One of the hot topic political issues of the day was the "investiture controversy", which was debate over who had the power to install bishops and other important clergy; the Pope or secular authorities. This evolved into a debate on who would have ultimate governing authority, the Pope, or the secular government, most notably the Holy Roman Empire. At the time, many cities in Italy were growing disgruntled with the rule of the Pope and the rule of nobles who supported the Pope. This resulted in popular uprisings in which cities overthrew the Papal government and declared themselves independent, thus forming various city states and communes in Italy.

In 1143 a wealthy Italian banker named Geordano Pierlione led a revolt against Papal authority, kicking the Pope out of Rome and declaring an independent Commune of Rome. The next year a monk and priest named Arnold of Brescia arrived in the city, becoming the intellectual leader of the movement and establishing the new Roman Republic. Arnold was a controversial reformer who railed against abuses of Church and Papal authority, decried Church corruption, and advocated a thorough reformation of the Church. Among his ideas he believed that clergy needed to return to apostolic poverty, renouncing all wealth and ownership of property, and also renouncing secular political power. Here's a statue of him in Brescia, Italy today.

With Arnold at it's head a new Roman government was formed and modeled after the ancient Roman Republic, with 56 senators who were not of noble class, 4 from each of Rome's medieval districts, and executive authority invested in a "patrician". The new republic refused to use the title "consul" as it had become an inherited noble title after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Nobles and aristocrats above the rank of knight were not allowed and thus most noble titles were abolished.

Of course the Pope, then Lucius II, was not going to tolerate such a rebellion and attempted to take back the city. In 1145 he formed an army and laid siege to the city. Amazingly the Romans drove away the invaders, with Pope Lucius II being killed in the battle after being bonked in the head with a rock.

The new republic flourished; drafting news laws, reforming medieval Roman society, making alliances with other Italian city states and war with others, setting up courts, and minting coins.

The Roman army was reformed, and a new capital building was constructed on the Capitoline Hill known as the Palazzo Senatorio (the Senate Palace), which still stands today but is much different after being heavily renovated by Michelangelo in the 1530's.

Originally the new Roman Republic swore fealty to the Holy Roman Emperor. However Rome and the Empire had a falling out. In 1149 the Roman Senate invited the German king Conrad III to the city to be coronated Roman Emperor. Rome's enemies were growing, so the Roman Senate offered Conrad this title in return for protection. Conrad had already been elected as Holy Roman Emperor and was due to be coronated, but the Roman Senate was proposing that he be THE Roman Emperor, as in like, a real Roman Emperor whose authority is defined by the Roman Senate, and not a Holy Roman Emperor whose authority was defined by the Pope and a loose confederation of high ranking German, Italian, Austrian, and Czech nobles. In the Holy Roman Empire the emperor is elected by the highest ranking nobles of the land. The Roman Senate was claiming that it had the authority to choose Roman emperors as the senate did during the ancient Roman Empire. Well, lets just say that Conrad probably didn't take too kindly to the Roman Senate attempting to usurp the governing structure of the Holy Roman Empire. In the middle ages a group of lower class burghers and knights cosplaying as Roman senators was not a good basis for a Europe spanning universal imperial monarchy. When Conrad died he was already cutting a deal with the Pope to snuff out the republic.

Conrad died in 1152 but his successor, Frederick Barbarossa continued the deal with the Pope to end the Roman Republic. It was one of the few times Frederick and the Pope agreed on anything. In 1155 a combined Papal/Imperial army invaded Rome. The city quickly fell and Arnold of Brescia was captured and burned at the stake. His ashes were scattered into the Tiber River.

Amazingly the Roman Republic lived on. Frederick Barbarossa was coronated by Pope Adrian IV as Holy Roman Emperor, an act which led to a new revolt among the Romans. Frederick put down this revolt, killing 1,000 Romans in the process, but afterwards he simply left the city and never returned after becoming bogged down in the complex politics of Italy. The Pope also left Rome, having to deal with a papal schism, resulting in no one being left in charge of the city and thus another restoration of the Roman Republic.

In 1167 Rome made war on the neighboring city of Tusculum, a long time rival of Rome who had supported the Pope and became a papal capital after the foundation of the republic. The Count of Tusculum appealed for help to the Holy Roman Empire, and Frederick I sent a small army of 1600 men. The Romans had an army of 10,000 made up of peasant militia who were poorly armed and poorly trained. While heavily outnumbered the Imperial army consisted of well armed and trained knights and professional soldiers. The Imperial army easily defeated the Romans at the Battle of Monte Porizio on May 29th, 1167, a battle which would later be called, "the Cannae of the Middle Ages". The Imperial army would continue to march on Rome, but by a stroke of luck for the Romans would be struck with the plague and forced to turn back. The Romans got their revenge against Tusculum in 1183 when they conquered and burned the city to the ground Carthage style.

The beginning of the end of the republic came in 1188 when Pope Clement III made a power sharing deal with the senate in which the people would elect senators but the Pope would have to approve the senators. The senate agreed to this in order to secure the protection of the Pope as the Holy Roman Empire was still a threat. Over the coming decades popes would reduce the number of senators until by the early 13th century, there was just one. Soon that single senate post was directly chosen by the Pope, and eventually it became a hereditary position. Before you knew it, French and Spanish nobles were becoming Roman senators and Roman senators ruled as autocrats at the behest of the Pope. By the end of the 13th century, the Roman Republic was dead.

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday’s Late Night Sci-Fi Cinema (Special Double Feature)

Cosmos: War of the Planets (1977 film)

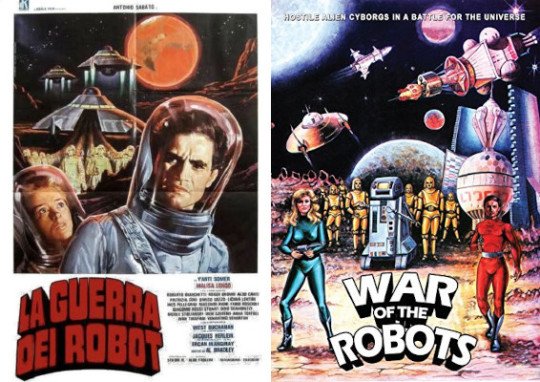

Italian theatrical (left) and one of the many international release (right) posters

Main cast:

John Richardson as Captain Fred Hamilton

Yanti Somer as Meela

Massimo Bonetti as Vassilov

Aldo Canti as Etor

Craig Kelly (as Romeo Constantini) as Commander Armstrong

Production staff:

Directed by: Alfonso Brescia (as Al Bradley)

Story by and screenplay by: Alfonso Brescia (as Al Bradley), Aldo Crudo (as Al Crydo), Maxim Lo Jacono (uncredited) and Jacob Macci (uncredited)

Cinematography by: Silvio Fraschetti (as S. Fraschetti)

Special effects by: Aldo Frollini (as Aldi Frollini)

Edited by: Larry Marinelli (as Lawrence Marinelli) and Carlo Reali (as Charles Really)

Music by: Marcello Giombini (as Marcel Giombrini)

Produced by: Luigi Alessi (as Louis Aless) (executive producer) and Doro Vlado Hreljanovic (executive producer)

Production company: Nais Film

Distributed by: Picturemedia Limited

Original release date: September 23, 1977 (Italy)

YouTube channel: Filmix

In a distant time, where most of mankind is putting their unconditional trust in technology, Captain Fred Hamilton has a different attitude.

He is now at Orion Space Complex before its commander facing a charge of insubordination for slapping one of his superiors.

The reason: he refuses to take orders from the WIZ Computer System.

The Commander Armstrong decided not to punish him by now because he thinks Hamilton's mindset will be useful at missions in outer space. And orders the Captain and his crew from the Starship MK-31 to repair a 100 year-old satellite.

After the success of the repair mission, Captain Hamilton receives another order: To track the origin of a signal that interferes with all radio and video communications of planet Earth.

The MK-31 arrives to an alien planet to be received by two flying saucers ready to the attack.

The crew took down one of them and received a direct hit from the other. They had to make a landing on the planet.

In there, they found a race of humanoids who are under the slavery of a giant robot.

It seems the Captain and his crew are the last resort for both Earth and that alien world.

Cosmos: War of the Planets is an Italian space opera film from 1977. Its original title is Anno Zero: Guerra Nello Spazio (Year Zero: War In Space in English). Directed by Alfonso Brescia under the pseudonym of Al Bradley.

Fascinating fact:

A Star Wars rip off that gets its release a few months after the release of Episode IV: A New Hope.

youtube

War of the Robots (1978 film)

Italian theatrical release poster (left) and a cover art for one of the many international VHS, DVD and Blu-Ray releases (right)

Main cast:

Antonio Sabato, Sr. as Captain John Boyd

Yanti Somer as Julie

Malisa Longo (as Melisa Long) as Louis

Aldo Canti (as Nick Jordan) as Kuba The Alien

Jacques Herlin (as Jacques Herlein) as Professor Carr

Ines Pellegrini (as Mickey Pilgrim)

Ian Pulley as The Autoritarian Leader

Roger Brown (uncredited) as Commander King

Licinia Lentini (as Lilian Lacey) as Commander King's Assistant

Production staff:

Directed by: Alfonso Brescia (as Al Bradly)

Story by and screenplay by: Alfonso Brescia (as Al Bradly) and Aldo Crudo (as Alan Rawton)

Cinematography by: Silvio Fraschetti (as Cyril Franks)

Special effects by: Aldo Frollini (as Allan Forsyth)

Edited by: Mariano Arditi (as Mark Arnold)

Music by: Marcello Giombini (as Marcus Griffin)

Produced by: Luigi Alessi

Production companies: Nais Film and Koala Cinematografica

Distributed by: Picturemedia Limited

Original release date: April 21, 1978 (Italy)

YouTube channel: Timeless Classic Films

The Professor Carr developed a machine that could give to the ones who own it such a great power to create life but it could also can lead to disastrous results.

At that time, an UFO has infiltrated the planet Earth's security system bringing in a gang of alien robots that kidnapped the Professor and his assitant, Louis.

In the Space Station Sirius, Commander King gave orders to Captain John Boyd and his crew of the Spaceship Trissi to pursue the UFO and rescue the couple of scientists.

There is also an urgent need to rescue the Professor. He is the only one capable of turning off a nuclear reactor. If it is not done, the Station and a nearby city would be destroyed in an explotion.

In the pursuit, they have to face more UFOs. After a intense battle with the saucers, they land on the planet Antor.

There, the crew of the Triss meet a dying world and their inhabitants. They established a friendship with Kuba, the leader of a tribe of slaves who agree to go with them to fight against their tyrannical masters.

Captain Boyd and his crew are about to be witnesses of the true nature of the Professor and his assitant in order to save the future.

War of the Robots, is an Italian space opera film from 1978. Its title is a translation of the original title La Guerra Dei Robot. Directed by Alfonso Brescia under the pseudonym of Al Bradly.

Fascinating facts:

It is not a sequel of Cosmos: War of the Planets. It was produced with much of the production crew, actors and props from the aforementioned movie, but its storyline is different.

The name of Trissi it's also the name of Trissi Sports. The same company in charge of the design and making of the spacesuits.

youtube

#space opera#space western#70s sci fi#star wars rip off#star wars rip offs#star wars episode iv: a new hope#Alfonso Brescia#Al Bradley#Al Bradly#Italian sci-fi#italian fantasy#italian adventure#italian movies#italian film#italian films#Italian movies#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Bergamo: dai proggeti inclusivi alle politiche green, tanti spunti al BIC Festival delle Biblioteche

Bergamo: dai proggeti inclusivi alle politiche green, tanti spunti al BIC Festival delle Biblioteche.

A Bergamo, Capitale della Cultura 2023 insieme a Brescia, si è svolta la prima giornata dell'iniziativa.

Dai progetti inclusivi dedicati a persone con fragilità, alle politiche green nelle scelte dei mezzi di consegna, dall’innovazione al factchecking alla creazione di blog, social e portali, dalla rigenerazione urbana alla valorizzazione del territorio.

I bibliotecari si scambiano le loro buone pratiche al BIC, il festival dedicato alle biblioteche in corso allo spazio Daste di Bergamo. Raccontano le loro esperienze prendendo parola sul palco delle ignite talk: interventi che non devono superare i 5 minuti e che potrebbero servire da spunto per altre realtà.

Due le sessioni previste nel primo giorno di lavori al Daste: la prima è stata introdotta dal filosofo Telmo Pievani, la seconda da Alessandro Bollo, esperto in management e progettazione culturale, già direttore del Polo del ‘900 di Torino.

Pievani ha raccontato una storia: quella di Frances Arnold, chimica e ingegnere statunitense che nel 2018 ha vinto il premio Nobel per la chimica. “Frances nel 1976 si trovava a Madrid quando per caso legge “La biblioteca di Babele” di Jorge Luis Borges e ha un’illuminazione: immagina quegli scaffali sterminati pieni di libri senza senso dove solo alcuni contengono frasi di senso compiuto, li immagina pieni di enzimi ed inizia a navigarci dentro, come se fosse una bibliotecaria a caccia di senso. Ci lavora 25 anni inserendo gli enzimi esistenti e applicando tutte le possibili mutazioni. E, grazie alla sua caparbietà, arriva a vincere il Nobel. Questo per dirvi che se si ha un obiettivo bisogna perseverare e che spesso la risposta che si cerca si trova nel libro accanto a quello che si stava cercando. E ci si imbatte per caso. Siamo molto ignoranti, caratteristica che nella scienza è molto positiva, perché ci spinge a scoprire sempre cose nuove. E in questo senso il dialogo è fondamentale, anche tra discipline diverse, perché è dal confronto che arrivano le scoperte più grandi”.

Bollo ha puntualizzato sulla diversa narrazione che deve essere prodotta attorno alle biblioteche: “Negli ultimi 25 anni sono state al centro del cambiamento sociale, culturale, tecnologico. Le biblioteche non sono più i luoghi in cui si prendono in prestito i libri e sono i presidi culturali che maggiormente si sono messi in gioco, uscendo spesso dalle loro zone di comfort. È necessario lavorare sui luoghi e sulla vocazione degli spazi che possono essere inclusivi, abilitanti e militanti: le biblioteche hanno tutte e tre queste caratteristiche ma devono lavorare maggiormente sulla narrazione che viene fatta attorno a questi luoghi. Devono raccontarsi diversamente per uscire dallo stereotipo valorizzando tutte le loro potenzialità”.

Tanti i progetti presentati negli interventi dei partecipanti. Laura Boni, responsabile del Sistema Bibliotecario Urbano di Bergamo ha parlato dei progetti attivi nell’ambito dell’inclusione, come “La biblioteca a casa tua” e il progetto Incoop, che coinvolgono giovani con fragilità, o la biblioteca del carcere.

Anche il progetto BookBox coinvolge persone con disturbi dello spettro autistico. Ne ha parlato, commuovendosi,

Stefania Romagnoli della biblioteca La Fornace di Maiolati Spontini, in provincia di Ancona: “Book Box permette di coinvolgere i ragazzi nella raccolta di libri donati dalle case editrici o dai cittadini, che possono lasciarli in scatole disseminate in giro per la città. Una volta raccolti e catalogati, questi libri vengono distribuiti nelle sale d’attesa degli ambulatori, dei pronto soccorso, nei centri estetici, delle parrucchiere, delle aziende e in tutti i luoghi di attesa. Le persone che collaborano al progetto si occupano di cambiare periodicamente i titoli. Il dentro non basta più, andiamo noi a stanare i nuovi utenti della biblioteca”.

C'è il progetto bergamasco DigEducati, finalizzato alfabetizzazione digitale sostenuto da Fondazione della Comunità Bergamasca insieme a Fondazione Cariplo e Impresa sociale ‘Con i Bambini’. Illustrato da Chiara Di Carlo della Biblioteca di Seriate, promuove, per il triennio 2021-2024, attività dedicate ai bambini dai 6 ai 13 anni.

Ci sono i progetti, quasi tutti nati dall’esperienza del Covid e legati quindi alle nuove tecnologie.

C’è Librida, illustrato da Maria Stella Rasetti della biblioteca San Giorgio di Pistoia, che nel lockdown ha organizzato una fiera del libro digitale che è poi diventata uno spazio virtuale permanente dove gli utenti possono interagire con i bibliotecari, porre domande, chiedere informazioni, ricevere un servizio virtuale come quello in presenza.

Damiano Orrù dell’Università di Roma Tor Vergata ha parlato di BiblioVerifica, un blog di bibliotecari nato per sviluppare il senso critico dell’utente al quale vengono fornite informazioni rispetto alle strategie di verifica delle informazioni.

Davide Bassi della Rete Bibliotecaria di Mantova ha illustrato il progetto della Casa Digitale del Lettore, un portale a metà tra un blog e un social network. “Funziona come un catalizzatore, come hub delle esperienze di lettura, una comunità attiva e dialogante di lettori, in particolare rivolto al pubblico giovanile. Abbiamo avviato un percorso con le scuole superiori come esperienza di alternanza scuola lavoro: 274 ragazzi hanno aderito, un numero straordinario per la nostra provincia. In tanti si sono appassionati al mondo della biblioteca e, incredibilmente, alla catalogazione, tant’è che alcuni hanno cominciato a catalogare la biblioteca scolastica”.

Lorenzo Gobbo, delle Biblioteche dell’università della Svizzera Italiana ha parlato di Gesnet, un modello di rete decentralizzata per l’accesso permanete al patrimonio culturale digitale di cui possono farsi carico le biblioteche per combattere vulnerabilità di internet e garantire la permanenza delle risorse e trasmetterle alle generazioni future.

Per tutti gli appassionati di viaggi, ma non solo, c’è la Mappa Letteraria, un sito illustrato da Daniela Mena dell’associazione L’Impronta, Microeditoria e Centro per il libro e la lettura di Brescia. Il progetto connette libri e luoghi: “La letteratura abita i nostri paesaggi, vogliamo fornire una risposta a lettore viaggiatore che vuole prepararsi, portandosi in valigia non solo le guide. Coloro che conoscono i luoghi e territori sono i bibliotecari, quindi li abbiamo coinvolti chiedendo loro di caricare sul portale i libri che parlano dei loro territori. Vogliamo affermare il concetto di turismo letterario”.

Le biblioteche svolgono un’importante funzione anche a livello di promozione del territorio.

Laura Campopiano della biblioteca Gianico, in provincia di Brescia, ha illustrato il progetto La Funsciù, mutuando il nome da una celebrazione religiosa che avviene in paese ogni dieci anni. Si tratta una biblioteca digitale che mira a salvaguardare il patrimonio storico culturale del comune.

C’è il progetto che la Rete Bibliotecaria Bergamasca ha creato per Bergamo Brescia Capitale della Cultura. Si chiama Produzioni Ininterrotte ed è stato spiegato dal presidente della Rbbg Gianluca Iodice: “Il progetto è nato per trasferire sui territori oltre i capoluoghi le potenzialità di una capitale italiana della cultura. Le biblioteche, così capillari, sono state protagoniste ed hanno attivato alleanze con le associazioni e gli enti del terzo settore creando un calendario di appuntamenti lungo un anno. Il risultato è stato un successo e i numeri parlano: 31 i comuni coinvolti, 33 i luoghi interessati, 40 le associazioni che hanno collaborato, 93 gli eventi da gennaio a dicembre”.

Giancarlo Zoccheddu del Centro Servizi Culturali di Macomer, piccolo centro Sardegna, in provincia di Nuoro ha presentato dodici pillole partendo da citazioni di autori e libri.

Fabio Fornasari è un architetto e museologo che è stato chiamato a riqualificare la biblioteca Sala Borsa Lab di Bologna – Liquid lab, e lo ha fatto con una visione completamente nuova, utilizzando materiali di riciclo.

A Orvieto, la biblioteca Luigi Fiumi ha ideato il Bibliobike service. Roberto Sasso, il referente della biblioteca Luigi Fiumi, ha spiegato il servizio, nato per raggiungere tutte e 36 le frazioni della città, anche quelle più lontane dal centro. Alla Fiumi si noleggiano anche le biciclette e con il ricavato si sostiene il progetto.

Francesco Serafini del Sistema Bibliotecario di Pavia ha illustrato il progetto Biblioinsieme, che ha parlato di quanto i cittadini, nonostante la città offra ben 50 biblioteche, 11 delle quali comunali, abbiano chiesto a gran voce di riattivare le biblioteche di quartiere. Avendo a disposizione pochi fondi hanno chiesto ad associazioni di gestire questi luoghi facendosi carico della riqualificazione, ottenendo risposte entusiaste. Questi spazi sono diventati tematici: una di queste biblioteche è gestita da un’associazione di gaming, un’altra da una compagnia teatrale ed è specializzata in libri dedicati al cinema, al teatro e alla musica.

BIBLIOTECA DI CONFINE GIACOMO BARONI:

Giacomo Baroni ha parlato di una realtà particolare, come la biblioteca di Rosarno: “Troppo spesso ci definiamo biblioteche di confine, marginali, situate in luoghi difficili, ma vorrei che questa logica, grazie alle nostre azioni concrete, si possa ribaltare. Dal confine possiamo anche osservare a distanza ciò che avviene al centro, possiamo sperimentare. La nostra società cooperativa si chiama Kiwi e facciamo della cultura il nostro lavoro. Siamo un gruppo di professionisti che ha deciso di investire in Calabria, a Rosarno, per riabilitare questo territorio troppo spesso etichettato come marginale. Abbiamo riaperto la biblioteca, abbiamo tolto le cancellate che chiudevano lo spazio e abbiamo avviato una progettazione con scuole della città per ridisegnare la biblioteca di Rosarno, insieme. Abbiamo inserito una playstation per portare bambini in biblioteca, facciamo teatro, corsi di ceramica, yoga, presentiamo libri, facciamo incontri con gli autori. La biblioteca è un luogo flessibile e versatile, quasi una casa. Tant’è che sfruttiamo eventi popolari come ad esempio il festival di Sanremo per attirare le persone, che vengono a vedere insieme la finale, la commentano, socializzano, si conoscono. I cittadini non solo utenti, ma partecipano a creazione di prodotti culturali come ad esempio la guida di Rosarno o la progettazione di un gioco per la costruzione di storie. C’è anche biblioteca fuori, per strada, nelle piazze, per azzerare il divario di chi frequenta la biblioteca e chi no, senza limiti”....

#notizie #news #breakingnews #cronaca #politica #eventi #sport #moda

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

That one time in the middle ages when peoe tried to reinstate the Roman Republic and Peter Abelard's buddy joined them:

"Two years earlier the renovatio senatus (“renewal of the Senate”), seeking independence from ecclesiastical control, had expelled Innocent and the cardinals, revived the ancient senate, and proclaimed Rome a republic.

Eugenius sent Arnold to Rome on a penitential pilgrimage. He soon allied himself with the insurgents and resumed his preaching against the Pope and cardinals. He was excommunicated in July 1148. Arnold’s agitation for ecclesiastical reform vitalized the revolt against the Pope as temporal ruler, and he soon controlled the Romans. He also worked to consolidate the citizens’ newly won independence.

Pope Adrian IV placed Rome under interdict in 1155 and asked the citizens to surrender Arnold. The Senate submitted, the republic collapsed, and the papal government was restored. Arnold, who had fled, was captured by the forces of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, then visiting Rome for his imperial coronation. Arnold was tried by an ecclesiastical tribunal, condemned for heresy, and transferred to the Emperor for execution. He was hanged, his body burned, and his ashes cast into the Tiber River."

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Browning and Robespierre?

RBZPR made this interesting post t’other day. While the quality of the portrait is not the best, the verse by Maximilien is extremely interesting, and not just in terms of expressing his fears.

Le seul tourment du juste à son heure dernière,

Et le seul dont alors il sera déchiré,

C'est de voir en mourant la pâte et sombre envie

Distiller sur son nom l'opprobre et l'infamie,

De mourir pour le peuple, et d'en être abhorré!

It reminds me very strongly of a favourite Robert Browning poem, about which I have long wondered.

An early draft of The Patriot mentions Brescia, and some have tried to associate it with the 1848 rising against the Austrians there; but it does not fit. It fits nearer, but not quite, the mediæval hero Arnold of Brescia, because his career actually ended in Rome, not his native city, and he was around for more than a year. But Browning then dropped the Brescia reference. Was it only an add-on “mask”? Because to me, it seems too much about this poem fits Max; and if his own verse was known in 19C sufficiently to be quoted on an item such as the plaque, might Browning have known of it? The subject was perhaps still too hot to handle explicitly in English, but smuggled in under a light disguise of the Risorgimento…? I give you Robert Browning’s The Patriot:

I

It was roses, roses, all the way,

With myrtle mixed in my path like mad:

The house-roofs seemed to heave and sway,

The church-spires flamed, such flags they had,

A year ago on this very day.

II

The air broke into a mist with bells,

The old walls rocked with the crowds and cries.

Had I said, ‘Good folks, mere noise repels -

But give me your sun from yonder skies!’

They had answered, ‘And afterward, what else?’

III

Alack, it was I who leaped at the sun,

To give it my loving friends to keep!

Nought man could do have I left undone:

And you see my harvest, what I reap

This very day, now a year is run.

IV

There's nobody on the house-tops now -

Just a palsied few at the windows set -

For the best of the sight is, all allow,

At the Shambles' Gate—or, better yet,

By the very scaffold's foot, I trow.

V

I go in the rain, and, more than needs,

A rope cuts both my wrists behind;

And I think, by the feel, my forehead bleeds,

For they fling, whoever has a mind,

Stones at me for my year's misdeeds.

VI

Thus I entered, and thus I go!

In such triumphs, people have dropped down dead.

‘Paid by the World, what dost thou owe

Me?’ - God might question; now instead,

'Tis God shall repay! I am safer so.

#poetry#robert browning#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#risorgimento#arnold of brescia#browning#victorian literature#thermidor

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todos os filmes em que as cenas de sexo foram para valer

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. Ao todo, a lista conta com 264 títulos.

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. Nos Estados Unidos, esse tipo de cena era proibido no cinema convencional, mas a partir dos Anos 1960 os cineastas começaram a ultrapassar os limites. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. A maioria deles foi lançada nos anos 1970 e 80, com predominância de dois diretores: o espanhol Jesús Franco e o italiano Joe D’Amato. Por repetidas vezes, também aparecem os nomes de cineastas consagrados atualmente, como Lars von Trier, Gaspar Noé e Yorgos Lanthimos.

1 — Gift (1966), Knud Leif Thomsen

2 — They Call Us Misfits (1968), Stefan Jarl

3 — F*uck (1969), Andy Warhol

4 — 99 Mulheres (1969), Stefen Thrower

5 — Double Face (1969), Riccardo Freda

6 — Quiet Days in Clichy (1970), Jens Jørgen Thorsen

7 — Groupie Girl (1970), Drek Ford

8 — The Deviates (1970), Eduardo Cemano

9 — Bacchanale (1970), John Amero

10 — Kama Sutra ’71 (1970), Raj Devi

11 — Cry Uncle! (1971), John G. Avildsen

12 — Slaughter Hotel (1971), Fernando Di Leo

13 — Uma Lagartixa num Corpo de Mulher (1971), Lucio Fulci

14 — Luminous Procuress (1971), Steven F. Arnold

15 — Secret Rites (1971), Drek Ford

16 —A Clockwork Blue (1972), Eric Jeffrey Haims

17 — Pink Flamingos (1972), John Waters

18 — Who Killed the Prosecutor and Why? (1972), Giuseppe Vari

19 — La Verità Secondo Satana (1972), Ronato Polselli

20 — So Sweet, So Dead (1972), Rose et Val

21 — The Red Headed Corpse (1972), Renzo Russo

22 — Commuter Husbands (1972), Derek Ford

23 — Delirium (1972), Renato Polselli

24 — Christina, the Devil Nun (1972), Sergio Bergonzelli

25 — Danish Pastries (1973), Finn Karlsson

26 — Ingrid the Streetwalker (1973), Brunello Rondi

27 — Thriller – Um Filme Cruel (1973), Bo Arne Vibenius

28 — Revelations of a Psychiatrist on the World of Sexual Perversion (1973), Renato Polselli

29 — A Scream in the Streets (1973), Carl Monson

30 — The Devil In Miss Jones (1973), Gerard Damiano

31 — Fleshpot on 42nd Street (1973), Andy Milligan

32 — The Other Side of the Mirror (1973), Jess Franco

33 — Diary of a Nynphomaniac (1973), Jesús Franco

34 — A Virgem e os Mortos (1973), Jesús Franco

35 — O Reduto dos Monstros (1973), Vidal Raski

36 — The Devil’s Plaything (1973), Joseph W. Sarno

37 — Anita (1973), Torgny Wickman

38 — The Sex Thief (1973), Martin Campbell

39 — The Porn Brokers (1973), John Lindsay

40 — Emmanuelle (1974), Just Jaeckin

41 — The Eerie Midnight Horror Show (1974), Mario Gariazzo

42 — Zelda (1974), Alberto Cavallone

43 — I Tyrens Tegn (1974), Werner Hedman

44 — Score (1974), Radley Metzger

45 — Riot on a Women’s Prison (1974), Brunello Rondi

46 — The Girls of Kamare (1974), René Viénet

47 — La Bonzesse (1974), François Jouffa

48 — Sweet Movie (1974), Dušan Makavejev

49 — Fiossie (1974), Marie Forsa

50 — Contos Imorais (1974), Walerian Borowczyk

51 — Lorna: O Exorcista (1974), Jesús Franco

52 — Countess Perverse (1974), Jesús Franco

53 — Carnal Revenge (1974), Alfredo Rizzo

54 — Keep It Up, Jack! (1974), Derek Ford

55 — The Hot Girls (1974), John Lindsay

56 — Voodoo Sexy (1974), Osvaldo Civirani

57 — Nude for Satan (1974), Luigi Batzella

58 — In the Sign of the Gemini (1974), Werner Hadman

59 — Come To My Bedside (1975), John Hillbard

60 — The Image (1975), Radley Metzger

61 — Número Dois (1975), Jean-Luc Godard

62 — The Teenage Prostitution Racket (1975), Carlo Lizzani

63 — Emanuelle Nera (1975), Bitto Albertini

64 — Emanuelle’s Revenge (1975), Joe D’Amato

65 — Felicia (1975), Max Pécas

66 — But Who Raped Linda? (1975), Jesús Franco

67 — A Maldição da Vampira (1975), Jesús Franco

68 — Les Chatouilleuses (1975), Jesús Franco

69 — L’Éventreur de Notre-Dame (1975), Jesús Franco

70 — Justine e Juliette (1975), Mac Ahlberg

71 — The Bloodsucker Leads the Dance (1975), Alfredo Rizzo

72 — Lábios de Sangue (1975), Jean Rollin

73 — Rêves Pornos (1975), Max Pécas

74 — Wham! Bam! Thank You, Spaceman! (1975), William A. Levey

75 — Breaking Point (1975), Bo Arne Vibenius

76 — Rolls-Royce Baby (1975), Erwin C. Dietrich

77 — Girls Come First (1975), Joseph McGrath

78 — The Sexplorer (1975), Derek Ford

79 — Le Sexe qui Parle (1975), Claude Mulot

80 — Barbie Wire Dolls (1975), Jesús Franco

81 — Emanuelle em Bangkok (1975), Joe D’Amato

82 — Lust (1976), Max Pécas

83 — The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), Radley Metzger

84 — Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Fantasy (1976), Bud Townsend

85 — Bedside Sailors (1976), John Hillbard

86 — In The Sign of the Lion (1976), Werner Hedman

87 — O Império dos Sentidos (1976), Nagisa Oshima

88 —Through the Looking Glasses (1976), Jonas Middleton

89 — A Real Young Girl (1976), Catherine Breillat

90 — Die Marquise von Sade (1976), Jesús Franco

91 — Girls in the Night Traffic (1976), Jesús Franco

92 — The French Governess (1976), Demofilo Fidani

93 — Inhibition (1976), Paolo Poetti

94 — Around the World in 80 Beds (1976), Jesús Franco

95 — Sex Express (1976), Derek Ford

96 — Keep It Up Downstairs (1976), Robert Young

97 — Secrets of a Superstud (1976), Morton L Lewis

98 — The Office Party (1976), David Grant

99 — The Angel and The Woman (1976), Gilles Carle

100 — Agent 69 in the Sign of Scorpio (1977), Werner Hedman

101 — Shining Sex (1977), Werner Hedman

102 — Fate la nanna coscine di pollo (1977), Amasi Damiani

103 — Blue Rita (1977), Jesús Franco

104 — Emanuelle na América (1977), Joe D’Amato

105 — Emanuelle Around the World (1977), Joe D’Amato

106 — Sister Emanuelle (1977), Giuseppe Vari

107 — Nazi Love Camp 27 (1977), Mario Caiano

108 — Under The Bed (1977), David Grant

109 — The Mark (1977), Ilias Mylonakos

110 — The Cerimony (1977), Omiros Efstratiadis

111 — Monsieur Sade (1977), Jacques Robin

112 — Caligula’s Hot Nights (1977), Roberto Bianchi

113 — Agent 69 Jensen in the Sign of Sagittarius (1978), Werner Hedman

114 — Behind Convent Walls (1978), Walerian Borowczyk

115 — Blue Movie (1978), Alberto Cavallone

116 — Sister of Ursula (1978), Enzo Milloni

117 — The Coming of Sin (1978), José Ramón Larraz

118 — Pleasure Shop on the Avenue (1978), Joe D’Amato

119 — You’re Driving Me Crazy (1978), David Grant

120 — Immoral Women (1979), Walerian Borowczyk

121 — Caligula (1979), Bob Guccione

122 — Images In a Convent (1979), Joe D’Amato

123 — Play Model (1979), Mario Gariazzo

124 — Giallo a Venezia (1979), Mario Landi

125 — Malabimba (1979), Andrea Bianchi

126 — A Prisão (1980), Oswaldo de Oliveira

127 — Beast in Space (1980), Alfonso Brescia

128 — Blow Job (1980), Alberto Cavallone

129 — La Gemella Erotica (1980), Alberto Cavallone

130 — Erotic Nights of the Living Dead (1980), Joe D’Amato

131 — Orgasmo Nero (1980), Joe D’Amato

132 — Flying Sex (1980), Joe D’Amato

133 — Libidomania (1980), Bruno Mattei

134 — When love is obscenity (1980), Roberto Polselli

135 — Hard Sensation (1980), Joe D’Amato

136 — Hotel Paradise (1980), Edoardo Mulargia

137 — Sex and Black Magic (1980), Joe D’Amato

138 — Porno Esotic Love (1980), Joe D’Amato

139 — The Porno Killers (1980), Roberto Mauri

140 — Sem Controle (1980), Paul Verhoeven

141 — Táxi para o Banheiro (1980), Frank Ripploh

142 — Os Frutos da Paixão (1981), Shuji Terayama

143 — Emmanuelle in Soho (1981), David Hughes

144 — Porno Holocaust (1981), Joe D’Amato

145 — Calígula: A História que Não Foi Contada (1982), Joe D’Amato

146 — Scandale (1982), George Mihalka

147 — Apocalipsis Sexual (1982), Carlos Aured

148 — Aphrodite (1982), Robert Fuest

149 — Il Nano Erotico (1982), Alberto Cavallone

150 — My Nights With Messalina (1982), Jaime J. Puig

151 — The Virgin for Caligula (1982), Jaime J. Puig

152 — Luz del Fuego (1982), David Neves

153 — Perdida em Sodoma (1982), Nilton Nascimento

154 — Killing of the Flesh (1983), Cesari Canevari

155 — Satan’s Baby Doll (1983), Mario Bianchi

156 — Taking Tiger Mountain (1983), Tom Huckabee

157 — Emmanuelle 4 (1984), Francis Leroi

158 — Lilian, The Perverted Virgin (1984), Jesús Franco

159 — Alcova (1985), Joe D’Amato

160 — James Joyce’s Women (1985), Michael Pearce

161 — Diabo no Corpo (1986), Marco Bellocchio

162 — Emmanuelle 5 (1987), Walerian Borowczyk

163 — Emmanuelle 6 (1988), Bruno Zincone

164 — Hotel St. Pauli (1988), Svend Wan

165 — Kindergarten (1989), Jorge Polaco

166 — Kinski Paganini (1989), Klaus Kinski

167 — Tokyo Decadence (1992), Ryu Murakami

168 — The Soft Kill (1994), Eli Cohen

169 — A Vida de Jesus (1997), Bruno Dumont

170 — Os Idiotas (1998), Lars von Trier

171 — O Tédio (1998), Cédric Kahn

172 — Fiona (1998), Amos Kollek

173 — Jesus is a Palestinian (1999), Lodewijk Crijns

174 — Romance (1999), Catherine Breillat

175 — Pola X (1999), Leos Carax

176 — The Man-Eater (1999), Aurelio Grimaldi

177 — Olhe por Mim (1999), Davide Ferrario

178 — Vampire Strangler (1999), William Hellfire

179 — Baise-moi (2000), Virginie Despentes

180 — Scrapbook (2000), Eric Stanze

181 — Intimacy (2001), Patrice Chéreau

182 — O Pornógrafo (2001), Bertrand Bonello

183 — Lucia e o Sexo (2001), Julio Medem

184 — Dias de Cão (2001), Ulrich Seidl

185 — O Centro do Mundo (2001), Wayne Wang

186 — La Novia de Lázaro (2002), Fernando Merinero

187 — Le loup de la côte Ouest (2002), Hugo Santiago

188 — Eternamente Sua (2002), Apichatpong Weerasethakul

189 — Coisas Secretas (2002), Jean-Claude Brisseau

190 — Ken Park (2002), Larry Clark

191 — Brown Bunny (2003), Vincent Gallo

192 — Faça Isto (2003), Tinto Brass

193 — Rossa Venezia (2003), Andreas Bethmann

194 — The Principles of Lust (2003), Penny Woolcock

195 — Anatomia do Inferno (2004), Catherine Breillat

196 — 9 Canções (2004), Michael Winterbottom

197 — Story of The Eye (2004), Georges Bataille

198 — Kärlekens språk (2004), Anders Lennberg

199 — Garotinho Bobo (2004), Lionel Baier

200 — All About Anna (2005), Jessica Nilsson

201 — 8mm 2 (2005), J. S. Cardone

202 — Beijando na Boca (2005), Joe Swanberg

203 — O Sabor da Melancia (2005), Tsai Ming-Liang

204 — Princesas (2005), Fernando Léon de Aranoa

205 — Deite Comigo (2005), Clement Virgo

206 — Destricted (2006), Gaspar Noé e outros

207 — Shortbus (2006), John Cameron Mitchell

208 — Taxidermia (2006), Gyorgy Pálfi

209 — Os Anjos Exterminadores (2006), Jean-Claude Brisseau

210 — Amour Fou (2007), Felicitas Korn

211 — Ex Drummer (2007), Koen Mortier

212 — Its Fine. Everything is Fine! (2007), David Brothers

213 — The Story of Richard O (2007), Damien Odoul

214 — Import Export (2007), Ulrich Seidl

215 — Serviço (2008), Brillante Mendoza

216 — Tropical Manila (2008), Sang-woo Lee

217 — Otto, ou Viva Gente Morta (2008), Bruce LaBruce

218 — À l’aventure (2008), Jean-Claude Brisseau

219 — Amateur Porn Star Killer 2 (2008), Shane Ryan

220 — Gutterballs (2008), Ryan Nicholson

221 — House of Flesh Mannequins (2009), Domiziano Cristopharo

222 — Anticristo (2009), Lars von Trier

223 — Viagem Alucinante (2009), Gaspar Noé

224 — The Band (2009), Anna Brownfield

225 — Canino (2009), Yorgos Lanthimos

226 — Angels With Dirty Wings (2009), Roland Reber

227 — Now & Later (2009), Philippe Diaz

228 — Bedways (2010), Rolf Peter Kahl

229 — Rio Sex Comedy (2010), Jonathan Nossiter

230 — The Bunny Game (2010), Adam Rehmeier

231 — Ano Bissexto (2010), Michael Rowe

232 — Gandu (2010), Qaushiq Mukherjee

233 — LelleBelle (2011), Mischa Kamp

234 — Desire (2011), Laurent Bouhnik

235 — O Amor é um Saco! (2011), Scud

236 — Caged (2011), Stephan Brenninkmeijer

237 — Léa (2011), Bruno Rolland

238 — The Wrong Ferrari (2011), Adam Green

239 — Clip (2011), Maja Milos

240 — Uma Estranha Amizade (2012), Sean S. Baker

241 — Paradise: Faith (2012), Ulrich Seidl

242 —And They Call It Summer (2012), Paolo Franchi

243 — I Want Your Love (2012), Travis Mathews

244 — Crônicas Sexuais de Uma Família Francesa (2012), Pascal Arnold

245 — Azul é a Cor Mais Quente (2013), Abdellatif Kechiche

246 — Ninfomaníaca (2013), Lars von Trier

247 — Pornopung (2013), Johan Kaos

248 — O Desconhecido do Lago (2013), Alain Guiraudie

249 — Zonas Úmidas (2013), David Wnendt

250 — Pasolini (2014), Abel Ferrara

251 — Diet of Sex (2014), Borja Brun

252 — Angry Painter (2015), Kyu-hwan Jeon

253 — Love (2015), Gaspar Noé

254 — Muito Amadas (2015), Nabil Ayouch

255 —Theo e Hugo (2016), Olivier Ducastel

256 — Tenemos la Carne (2016), Emiliano Rocha Minter

257 — Needle Boy (2016), Alexander Bak Sagmo

258 — Love Machine (2016), Pavel Ruminov

259 — A Noite (2016), Edgardo Castro

260 — A Thought of Ecstasy (2017), Rolf Peter Kahl

261 — Ana, Meu Amor (2017), Calin Peter Netzer

262 — Picture of Beauty (2017), Maxim Ford

263 — Marfa Girl 2 (2018), Larry Clark

264 — Mektoub, My Love: Intermezzo (2018), Abdellatif Kechiche

Todos os filmes em que as cenas de sexo foram para valer Publicado primeiro em https://www.revistabula.com

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notte della Cultura 2019 - Brescia

ALLA LUNA, ALLA LUNA!

sonorizzazione dal vivo di filmati alle origini del cinema

sabato 5 ottobre 2019 ore 21.30

Brescia, cortile del Broletto

(in caso di pioggia auditorium S. Barnaba)

BRIXIA ART ORCHESTRA

Gabriele Rubino, Stefano D’Anna, Carmelo Coglitore, Luca Ceribelli, Nicholas Lecchi

saxofoni e clarinetti

Paolo Malacarne, Giuseppe Chirico, Riccardo Bianchi

trombe

Sara Cucchi

corno

Carlo Napolitano

trombone

Francesco Baiguera

chitarra

Giacomo Papetti

contrabbasso

Valerio Abeni

batteria

Corrado Guarino

pianoforte, direzione, composizioni e arrangiamenti

In occasione del cinquantesimo anniversario dello sbarco sulla Luna, la Brixia Art Orchestra propone, in collaborasione con Cinema Eden, la sonorizzazione di alcuni dei primi prodotti artistici della storia del cinema. Si tratta di sette “corti” in cui il tema della luna e dei viaggi spaziali è rappresentato con una stupefacente immaginazione e con uno spiccato gusto per il fantastico e per il trucco da prestigiatore. La musica è in gran parte scritta appositamente da Corrado Guarino, ma non mancano citazioni e elaborazioni tratte dai materiali musicali più disparati, dagli standard jazz a Arnold Schönberg, passando per un doveroso omaggio a Gil Evans.

La “Brixia Art Orchestra” è nata nel 2018 da un’idea di Stefano D’Anna e Corrado Guarino, con l’ambizione di creare una formazione stabile in grado di produrre progetti originali in cui abbia spazio l’intero universo espressivo del jazz, con uno sguardo verso la sua storia così come verso le sue contaminazioni con altri stili, e la sua contemporaneità in continua evoluzione. L'organico della formazione comprende musicisti affermati e giovani promettenti che gravitano nell'area di Brescia.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.

At the opening of the thirteenth century, Christendom, as a whole, rested united in profound belief in one religious faith. There had appeared in the age preceding teachers of new doctrines, like Abailard, Gilbert de la Poree, Arnold of Brescia, and others; but their new ideas had not at all penetrated to the body of the people. As a whole, Christendom had still, as the century began, an unquestioned and unquestionable creed, without schism, heresy, doubts, or sects. And this creed still sufficed to inspire the most profound thought, the most lofty poetry, the widest culture, the freest art of the age: it filled statesmen with awe, scholars with enthusiasm, and consolidated society around uniform objects of reverence and worship.

It bound men together, from the Hebrides to the Eastern Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Baltic, as European men have never since been bound. Great thinkers, like Albert of Cologne and Aquinas, found it to be the stimulus of their meditations. Mighty poets, like Dante, could not conceive poetry, unless based on it and saturated with it. Creative artists, like Giotto, found it an ever-living well-spring of pure beauty. The great cathedrals embodied it in a thousand forms of glory and power. To statesman, artist, poet, thinker, teacher, soldier, worker, chief, or follower, it supplied at once inspiration and instrument.

Large parts of Europe

This unity of creed had existed, it is true, for five or six centuries in large parts of Europe, and, indeed, in a shape even more uniform and intense. But not till the thirteenth century did it co-exist with such acute intellectual energy, with such philosophic power, with such a free and superb art, with such sublime poetry, with so much industry, culture, wealth, and so rich a development of civic organisation. This thirteenth century was the last in the history of mankind in Europe when a high and complex civilisation has been saturated with a uniform and unquestioned creed.

As we all know, since then, civilisation has had to advance with ever-increasing multiplicity of creeds. What impresses us as the keynote of that century is the harmony of power it displays. As in the Augustan age, or the Periclean age, or the Homeric age, indeed, far more than in any of them, men might fairly dream, in the age of Innocent and St. Louis, that they had reached a normal state, when human life might hope to see an ultimate symmetry of existence. There have been since epochs of singular intellectual expansion, of creative art, of material progress, of moral earnestness, of practical energy. Our nineteenth century has very much of all of these in varying proportions. But we have long ceased to expect that they will not clash with each other; we have aban- K doned hope of ever seeing them work in organic harmony together.

0 notes

Photo

So fertile in new political ideas

The same age, too, which was so fertile in new political ideas and in grand spiritual effort, was no less rich in philosophy, in the germs of science, in reviving the in-heritance of ancient learning, in the scientific study of law, in the foundation of the great Northern universities, in the magnificent expansion of the architecture we call Gothic, in the beginnings of painting and of sculpture, in the foundation of modern literature, both in prose and verse, in the fullest development of the Troubadours, the Romance poets, the lays, sonnets, satires, and tales of Italy, Provence, and Flanders; and finally, in that stupendous poem, which we universally accept as the greatest of modern epical works, wherein the most splendid genius of the Middle Ages seemed to chant its last majestic requiem, which he himself, as I have said, emphatically dated in the year 1300. Truly, if we must use arbitrary numbers to help our memory, that year— 1300 — may be taken as the resplendent sunset of an epoch which had extended in one form back for nearly one thousand years to the fall of the Roman empire, and equally as the broken and stormy dawn of an epoch which has for six hundred years since been passing through an amazing phantasmagoria of change tours sofia.

Now this great century, the last of the true Middle Ages, which, as it drew to its own end, gave birth to Modern Society, has a special character of its own a character that gives to it an abiding and enchanting interest. We find in it a harmony of power, a universality of endowment, a glow, an aspiring ambition and confidence, such as we never again find in later centuries, at least so generally and so permanently diffused.