#battle of fleurus

Text

Murat and Bessières at school

Still looking for something for @flowwochair, I came across this very brief remark in the memoirs of general Jean Sarrazin (more about him below):

When I was seven, my father took me to the college in Cahors, the capital of the Lot department. My father chose this college in preference to the one in Agen, on the advice of the Comte de Fumel, whose tenant he was. [...] I was raised with Murat, Bessières and Andral, with whom I was friends. Bessières was well-behaved, a little Cato. Murat was a scatterbrain, boisterous and concerned only with his own pleasures. He was a true Paris brat (gamin de Paris).

Now, I assume this author is a highly suspicious source. Not only because he, obviously, is yet another Gascon, but mostly because he, after having served in the Revolutionary and Imperial army, defected to the British in 1810, and supplied them with plenty of information on Napoleon’s plans and the most prominent leaders of his army. As a matter of fact, in 1811 he had a book published with descriptions of several prominent figures in France, called "The Philosopher", the first chapter of which is dedicated to Marshal Soult, who was probably the most interesting to the British due to him being their main opponent in Spain, and who in this book receives much more praise than is due to him. While much of it may be plain wrong or at least cannot be verified, I feel like it’s an interesting insight into what people in the army at the time thought about these folks.

Among other things, Sarrazin gives a long description of the battle of Fleurus, with some interesting twists. Mostly he claims that Lefebvre owed his reputation as a great general only to Soult, who at the time was his chief-of-staff, and even has general Marceau exclaim that Soult had won the battle of Fleurus for them. This is completely opposite to Soult’s own memoirs, where Soult has nothing but praise for Lefebvre’s actions during the battle of Fleurus, and barely mentions his own. However, there seems to be some truth to Soult coming to the aid of one rather desperate general Marceau, as Soult mentions this, too, though in a very different context.

The demand to detach some troops at a very inopportune moment is made in Soult’s memoirs as well – but not by Marceau, but by Saint-Just. And it’s not Lefebvre and Soult who refuse, but Jourdan (whom Soult praises a lot for having had the courage to stand up to what he calls "Saint-Just's presumptuous ignorance"). I am not sure in how far these memoirs are influenced by Soult’s own long life and his own political situation, but he clearly despises Saint-Just. According to his memoirs, the whole officers’ corps was shaking with fear while the politicians were with them, literally scared to death. In front of Charleroi, one artillery capitaine allegedly was executed for having failed to meet the schedule Saint-Just had set for him.

Again, I have no clue what this is based on. But I thought it worth mentioning, maybe somebody from the Frev community can shed some light onto this incident.

(Personally, I feel like Soult may be projecting here a little of "Joseph's presumptuous ignorance" onto another episode of his life 😋)

#napoleon's marshals#jean de dieu soult#battle of fleurus#1794#saint just#francois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste jourdan#frev

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

at this point i am no longer sure if i can call jean-clément martin a historian anymore, dude really shatposted about his role as “scientific”(?) advisor to the Video Game that We Do Not Talk About implying that slandering Marat as an overbearing brother and generally unloveable person, slandering Saint-Just as a selfishly revenge-driven criminal, etc, is comparable to depicting the use of flying machines in the 1790s (and I don’t even want to get into how the hot air balloon was already put into military use in the Battle of Fleurus).

Obviously I cannot be the person to systematically write a long call-out post for Jean-clément here, because I’m not a historian. But really I’d avoid any source that mainly cite him.

as always, save me o more well-read mutuals of mine. Save me. I mean, correct me if I’m wrong.

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

you mentioned that carnot went behind the others' backs to wage a war of conquest, would you mind talking about that a little more? i don't know that much about carnot and his war opinions but i would like to! thank you for your excellent posts :)

Before discussing Carnot's actions during wartime, it's essential to understand his political journey, as it inherently shapes his conduct during conflicts. He exhibits a true weathercock attitude, common among politicians of his era (and persisting today), although not as extreme as someone like Fouché.

Initially allied with the Girondins on war-related issues, he maintained this stance while also voting for the King's death, similar to the Montagnards, and advocating for progressive taxation. Personally, I view his alliance with the Montagnards as opportunism that persisted throughout his life, unlike Couthon, whose allegiance to the Mountain seemed more genuine, but this is solely my perspective. His ideas of war of conquest to better pillage, they will be constant throughout his life.

Later on, Carnot found himself at odds with Saint-Just, particularly regarding wartime strategy. Contrary to popular belief, Carnot could be more decisive than Saint-Just in matters of punishment even if Saint Just established army discipline with others.

While Carnot did a decent job in terms of armament, the ideas of Saint-Just and others significantly contributed to improving the army and securing victories. Saint-Just's encouragement of fraternity among soldiers, requisitioning shoes from aristocrats to distribute to barefoot soldiers who fought without shoes, and his equal treatment of generals and soldiers, instauring fraternity , and the courage to put himself in the front on the front line which earned him admiration including his enemies like Marc Antoine Baudot, boosted troop morale.

Moreover, there was a replacement of generals genuinely motivated to ensure the army's victory because some generals with affiliations to royalists, aristocratic backgrounds, or little sympathy for the Republic lacked the commitment to save France. Carnot failed to address these issues, despite opportunities.

One might argue that Carnot's physical presence in Paris to coordinate operations was necessary, but his interference with specialists on the ground hindered progress.

Regarding the question of Fleurus, a significant victory for the French Republic, Carnot's actions trouble me deeply. He demanded a reduction in Jourdan's army by 18,000 men, issuing the order behind Saint-Just's back, with plans for these troops to serve under General Pichegru and plunder Rhin. Saint-Just intercepted and canceled the order, preventing a potential defeat at Fleurus. These actions occurred without the knowledge of his colleagues deputies who advocated for French armies to remain within natural borders.

To support my claims, here is an excerpt from Saint-Just's last speech:

"In the absence of this member, a military expedition, which will be judged later because it cannot yet be made known, but which I consider insane given the prevailing circumstances, was conceived. Orders were given to draw, without informing me or my colleagues, 18,000 men from the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse for this expedition. I was not informed, why? If this order, given on the 1st of Messidor, had been executed, the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse would have been forced to leave Charleroi, perhaps to withdraw under Philippeville and Givet, and to abandon Avesnes and Maubeuge. Shall I add that this army had become the most important?

The enemy had brought all its forces against it, leaving it without powder, cannons, or bread. Soldiers died of hunger there while kissing their rifles. An agent, whom my colleagues and I sent to the Committee to request ammunition, was not received, which would have flattered me had he been, and I owe this praise to Prieur, who seemed sensitive to our needs. Victory was necessary, and we achieved it.

The Battle of Fleurus contributed to opening up Belgium. I desire justice to be done to everyone and victories to be honored, but not in a manner that honors the government more than the armies, for only those who are in battles win them, and only those who are powerful benefit from them. Victories should therefore be praised, and oneself forgotten'".

Strangely, whereas Saint-Just spares Billaud-Varennes even if he critize him, Carnot is rightly put back in his place for his actions. He should have been at least fired to the moment when he make order on the back of his colleagues for this such action . In these period generals could have been executed for less than that. General Hanriot ( mistreated by history too), who effectively contained Parisian excesses through persuasion and not repression ( indication of good competence) , opposed Carnot's plan to strip Paris of his gunners, indicating Carnot's interference in matters beyond his expertise. I admit it was a free tackle against Carnot that one.

Skipping over the events of the Thermidorians, Carnot's adept political maneuvering aligns him once again with the right and its wars of conquest were able to continue being free from any important opponent in this matter during the period of Directoire. He becomes one of the five directors, earning the nickname "Organizer of Victory." However, this title is both pompous and false, as Carnot's contributions were not singular. He carried out violent repression against the Babouvists and accepted Napoleon's pardon, serving as Minister of War under the Consulate, despite his opposition to the creation of Napoleon's empire and was marginalized for it within the government. During the Hundred Days, Carnot's weathercock attitude contrasts with Prieur's steadfastness, ultimately resulting in his exile without ever returning to France because of the statut of regicide ( too bad that the punishment was the same for Prieur de la Marne). Why am I more indulgent to Prieur de la Marne than Carnot?

I mean that Prieur opposed Napoleon and his coup d'état on 18 Brumaire to the point of being dismissed immediately. It seems that he mainly adhered to the hundred days of Napoleon for fear of a new restoration of the Bourbons.

Carnot accepted the title of Minister of the Interior and was made a count. Big difference for me.

In conclusion, Carnot's conquest wars cost France dearly, morally and pragmatically, potentially favoring the emergence of a military dictator, the end of the French Revolution and facilitating the restoration of the Bourbons. It's regrettable that he didn't heed his colleagues' advice on this matter. This is solely my opinion, and I apologize to Carnot's admirers ( once again it's okay to contradict me) . All information provided is drawn from sources like Albert Ollivier, Soboul, etc. You can explore revolutionary portraits on the Veni Vidi Sensi website for further insights.

P.S.: Thank you for the compliment on my posts; I strive to offer the best insights drawn from historians and contemporaries.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Praise the Victories and Forget Ourselves": Saint-Just Thermidor Series

A section of Saint-Just's undelivered 9 Thermidor speech, something he drafted at his desk in the late hours of the first of two sleepless nights before his untimely end on 10 Thermidor.

"The Fleurus day [victory] contributed to opening up Belgium. I want justice to be done to everyone and victories to be honored, but not in such a way as to honor the government more than the armies, because only those who are in battles win them, and it is only those who are powerful who benefit from it; we must therefore praise the victories and forget ourselves.

If everyone had been modest and hadn't been jealous that we spoke more of another than of ourselves, we would be very peaceful; we would not have done violence to reason to bring generous men to the point of defending themselves in order to make it a crime for them."

Read the complete drafted speech here, from Saint-Just's 9 Thermidor Speech.

Other helpful resources for further reading:

Jean Jaurès Socialist History of the French Revolution, section in regard to 9 Thermidor.

Marisa Linton Dilemmas of Political Heroism in the French Revolution.

Patrice Higgonet The Meaning of Terror in the French Revolution

Albert Soboul Pour relire et comprendre Saint-Just

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ruthless Representatives, Unjust Executions (1/3): the Death of an Artillery Captain

This is a response to @josefavomjaaga's recent post, which partially deals with the alleged arrest and execution of an artillery captain by Saint-Just, then a representative on mission, during the siege of Charleroi, and the representatives' abuse of military men around the time of the battle of Fleurus. Josefa enquired whether anyone could shed light on this incident from the FRev community. While I am not well-versed in FRev events, I would like to offer some of my findings about military justice in the army during the Revolution in relation to the representatives in three parts. The first part deals directly with the tale of Saint-Just's execution of the artillery captain, and how it was turned into a symbol that exemplifies the Revolution's extrajudicial violence. All translation errors are my own.

The source about Saint-Just's terrorisation and execution of the artillery captain that is cited the most is from Soult’s memoirs (1854). Writers, including Colonel Phipps, use this source verbatim without questioning it, because Saint-Just and all the representatives were obviously Stupid Civilians who thought that any incompletion of their orders amounted to betrayal:

It was above all the siege division which deployed with activity before Charleroi. The colonel Marescot directed the engineering operations, under the eyes of Generals Jourdan and Hatry; we had a sufficient artilery crew, and the representatives Saint-Just and Lebas stood at the foot of the trench to speed up the work. One day, they visited the site of a battery that had just been marked out: "At what time will it be finished?" asked Saint-Just of the captain responsible for having it executed. "That depends on the number of workers that I will be given; but we will work relentlessly," responded the officer. "If tomorrow, at six o'clock, she is not ready to fire, your head will fall off!..."

In this short time, it was impossible for the work to be completed; even though as many men were put there as the space could contain. It was not entirely finished when the fatal hour struck; Saint-Just kept his horrible promise: the artillery captain was immediately arrested and sent to his death, because the scaffold marched in the wake of the ferocious representatives. (pp. 156-157)

Saint-Just, in Soult's depiction, is the proper Archangel of Death, guillotining everything that stands in his path. In portraying Saint-Just thus, Soult criticizes the representatives' murder of an innocent man. Worse, he depicts representatives as civilians that can only stand around instead of hardworking soldiers bringing the siege to fruition, making their commands unjustified. Soult condemns the fact that a civilian's word could be the injust law that separated soldiers from life or death.

That said, as Soult is no friend of the political figures of the Revolution, his remembered account requires precise corroboration to be valid. I found one earlier source that describes, presumably, the same incident, from Victoires, conquêtes, désastres, revers et guerres civiles des Français, de 1792 à 1815, vol. 3. It was written in 1817 by "a society of soldiers and men of letters", and edited by Charles Théodore Beauvais de Préau, a general of the Revolution and Empire. Though this anonymisation may have been taken to avoid the wrath of the Bourbons in the Restoration, it means we have no idea who wrote the following section, nor their intentions:

This fierce man [Saint-Just], who never showed himself in the trench, informed that a captain of the first regiment of artillery had been somewhat negligent in the construction of a battery of which he was in charge, had him shot in the trench. At the same time, he gave General Jourdan the order to arrest, and consequently have shot on the spot, the General Hatry, commander of the besieging troops, the General Bellemont, commander of the artillery, and the commander Marescot. The General Jourdan had, at the risk of his own life, the courage to resist the wishes of this gutless representative. The officers of whom we have just spoken of had the audacity of protesting against the cruel sentence which condemned the unfortunate artillery captain Méras, and, in his his atrocious delirium, Saint-Just dared to accuse them of complicity. (p. 47)

If we infer from the title of this source that the editor compiled the accounts of his comrades, then this account was written by a former Revolutionary and Imperial officer who could have some memory of the incident. However, many aspects of this text don’t line up with Soult’s account, including the way the captain was executed (shot in the trench here, guillotined in Soult's account). Saint-Just's successive condemnation of high-ranking officers, which highlights how much power he had over even the highest echelons of the army, also does not appear in Soult's account. But we do have a name for the captain: Méras. His name, in fact, appears in a 1797 publication: L'observateur impartial aux armées de la Moselle, des Ardennes, de Sambre et Meuse, et la Rhine et Moselle, a memoir by Pierre Charles Lecomte, at the time "the conducteur general of the artillery in the Army of the Rhin-Moselle [sic]". This is his account on the affair, relegated to a footnote:

Before giving the details of the capitulation of Charleroi, I must cite a horrible feature of the role of Representative Saint-Just.

The French proconsul ordered the construction of a battery that he thought was necessary.*

The general Bollemont [sic] entrusted its execution to an artillery captain, named Méras. All the shovels, pickaxes, and other utensils happened to be employed in other work, the orders of the Representative could not be executed. The morning of the next day, passing close to the location where the battery was supposed to be constructed, he [Saint-Just] shouted, raged, sent to search for the captain; and, without listening to his reasons, he had him arrested. Two days later, when his [Méras’] company was battling against the enemy, he [Saint-Just] had him taken from the prison, he had him conducted to the middle of his works; and there, o misery! o inhumanity! he had him assassinated. At night his company returned to the camp covered in glory; they learned that their chief had been shot; they surrendered to despair. They wanted to go to the tyrant: they were stopped, under the fear that some of these brave soldiers would have become new victims. Méras was so much loved, that all of the artillery wanted to enact vengeance on his assassin. This almost universal rumour made itself heard amongst the trenches; and, for preventing it from having consequences, the company of the unfortunate Méras was sent into the interior.

*We know that there was a time when the Representatives, often little-instructed in the military arts, dared impudently to command old soldiers whose arms had dulled, and obliged them to sacrifice, according to their whims, some thousands of brave soldiers. (p. 38-39)

Once again, the details contradict even more with Soult’s account, and with that of the 1817 one. Soult says as much help as possible was given to the artillery captian, but Lecomte says all other workers were occupied and that captain received little help (presumably because the battery was militrarily unimportant). Méras’ misery is stretched out over two days instead of him being shot immediately, and it is not the generals who protested against Méras' execution that Saint-Just raises a hand against, but Méras' entire company, which the civilian government sends to the Vendée. The message could not be clearer: under "tyrannical representatives" like Saint-Just, the Revolution is eating its soldiers, the common people it was supposed to protect.

Is this the truth of the matter, since it is the earliest version? The publication is contemporary enough, but I am inclined to doubt the reliability of a text explicitly titled “impartial”. A look at the author's background reveals his attitudes. Lecomte was, according to BnF data, the maître de pension in Versailles until 1792 (presumably up to the abolishment of the monarchy), then the inspector of octroi taxes in Paris until 1815. Seeing that he served the First Empire, I am inclined to think that he was no die-hard revolutionary, and certainly not part of the Montagnard faction. Furthermore, he published his account after the fall of the Montagnards, during the height of the Directory. This makes the affair more likely to be Thermidorian propaganda, and indeed Lecomte even admits that his account was an “almost universal rumour”, not a fact, because in his story, no one is present at the scene of Méras’ death other than Saint-Just and his executioner. This makes the account unverifiable, and makes it more likely to be fabrication.

It would seem that, after Saint-Just’s death, the army’s fear and hatred of representatives turned into slander against their characters, often resulting in widely circulated variants of the same tale to emphasise different effects. The 1797 version highlights Saint-Just’s cruelties as a tyrant against the “small folk” of the Revolution and uses exclamatory language to amplify the reader's pathos. The 1817 version emphasises Saint-Just’s power over even the generals of the army, exaggerating his dictatorship. Finally, in Soult’s memoir, Saint-Just is not just a dictator who could dismiss soldiers with a wave of a hand. He and the representatives were synonymous with the guillotine and the excesses of the Revolution themselves.

The accounts of Saint-Just condemning Méras to death are inconsistent, and should amount to nothing more than invalid hearsay, which tells us nothing of the representatives' historical actions. If anyone has more information on the topic or the wider subject, feel free to add to this.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Battle of Fleurus

The Battle of Fleurus (26 June 1794) was the climax of the Flanders Campaign of 1792-95 and was one of the most decisive battles in the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797). A French victory, Fleurus ensured French ascendency for the rest of the war, leading to France's conquest of Belgium and to the destruction of the Dutch Republic.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

beach day with these assholes

stuff that happened + more images under cut :3 ( including seagull )

my autistic ass accidentally made the entire thing frev + amrev related . . . oops

the car drive there was me info dumping about frev for 45 minutes and then continuing to info dump for the next 30 minutes we spent trying to get food and then info dumping for the next 1 hour or so we spent eating on the beach

in that hour i met this silly !

i may or may not have named them maxime . but . they hung around for like the entire time ? ? ? ? ? it was sooo cool i miss them so bad :(

the little shit would not eat corn . but he fucked chips up so there was that

then i got fucking possessed by hamilton or something and forgot i was at a beach , got my inkwell out and wrote until my mother wanted to go home aFJDLSKJFSF

the clouds were lookin like phoenixes ( phoenixi ? phoeni ? who knows ) so i wrote about that and humanity burning and rebirth and stuff :3

and then we had to go home BUT FIRST

i got a lovely eighteenth century adaption of star wars : revenge of the sith !

I HAVE THE HIGH GROUND HAMILTON

and then the car drive home was singing hamilton because im silly like that

and now im going back to researching the battle of fleurus :3

#silly day#amrev#frev#frevblr what do we think of maxime the seagull#they were a very polite fellow#rather scared of my ipad though#oh yeah so funny story my ipad is literally stuck together with sticky tape#and whilst we were waiting for food#THE TAPE FUCKING BROKE#so i fucked around at the beach with a tapeless ipad#twas terrifying#terrorfying if you will#haha get it#terror#maxime the seagull#haha#okay sorry

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult,[1][2] 1st Duke of Dalmatia (French: [ʒɑ̃dədjø sult]; 29 March 1769 – 26 November 1851) was a French general and statesman. He was a Marshal of the Empire during the Napoleonic Wars, and served three times as President of the Council of Ministers (prime minister) of France.

Son of a country notary from southern France, Soult enlisted in the French Royal Army in 1785 and quickly rose through the ranks during the French Revolution. He was promoted to brigadier general after distinguishing himself at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794, and by 1799 he was a division general. In 1804, Napoleon made Soult one of his first eighteen Marshals of the Empire.

yeah

i’m sorry

for copying and pasting from wikipedia

and probably for drawing an anime body pillow design of jean-de-dieu soult

#jean-de-dieu soult#napoleonic shitposting#cadmus draws#the chief goal was to give him a look of utter disgust and contempt#I don’t think I succeeded in that as much as i wanted to#napoleon’s marshals#tumblr does still do the after five tags it doesn’t show up in the tag right#the real question is do I do Ney Murat or Bessieres next#dead frenchmen dakimakura series

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 7.1

69 – Tiberius Julius Alexander orders his Roman legions in Alexandria to swear allegiance to Vespasian as Emperor.

552 – Battle of Taginae: Byzantine forces under Narses defeat the Ostrogoths in Italy, and the Ostrogoth king, Totila, is mortally wounded.

1097 – Battle of Dorylaeum: Crusaders led by prince Bohemond of Taranto defeat a Seljuk army led by sultan Kilij Arslan I.

1431 – The Battle of La Higueruela takes place in Granada, leading to a modest advance of the Kingdom of Castile during the Reconquista.

1520 – Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés fight their way out of Tenochtitlan after nightfall.

1523 – Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos become the first Lutheran martyrs, burned at the stake by Roman Catholic authorities in Brussels.

1569 – Union of Lublin: The Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania confirm a real union; the united country is called the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth or the Republic of Both Nations.

1643 – First meeting of the Westminster Assembly, a council of theologians ("divines") and members of the Parliament of England appointed to restructure the Church of England, at Westminster Abbey in London.

1690 – War of the Grand Alliance: Marshal de Luxembourg triumphs over an Anglo-Dutch army at the battle of Fleurus.

1690 – Glorious Revolution: Battle of the Boyne in Ireland (as reckoned under the Julian calendar).

1766 – François-Jean de la Barre, a young French nobleman, is tortured and beheaded before his body is burnt on a pyre along with a copy of Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique nailed to his torso for the crime of not saluting a Roman Catholic religious procession in Abbeville, France.

1770 – Lexell's Comet is seen closer to the Earth than any other comet in recorded history, approaching to a distance of 0.0146 astronomical units (2,180,000 km; 1,360,000 mi).

1782 – Raid on Lunenburg: American privateers attack the British settlement of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.

1819 – Johann Georg Tralles discovers the Great Comet of 1819, (C/1819 N1). It is the first comet analyzed using polarimetry, by François Arago.

1823 – The five Central American nations of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica declare independence from the First Mexican Empire after being annexed the year prior.

1837 – A system of civil registration of births, marriages and deaths is established in England and Wales.

1855 – Signing of the Quinault Treaty: The Quinault and the Quileute cede their land to the United States.

1858 – Joint reading of Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace's papers on evolution to the Linnean Society of London.

1862 – The Russian State Library is founded as the Library of the Moscow Public Museum.

1862 – Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, second daughter of Queen Victoria, marries Prince Louis of Hesse, the future Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse.

1862 – American Civil War: The Battle of Malvern Hill takes place. It is the last of the Seven Days Battles, part of George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign.

1863 – Keti Koti (Emancipation Day) in Suriname, marking the abolition of slavery by the Netherlands.

1863 – American Civil War: The Battle of Gettysburg begins.

1867 – The British North America Act takes effect as the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia join into confederation to create the modern nation of Canada. John A. Macdonald is sworn in as the first Prime Minister of Canada. This date is commemorated annually in Canada as Canada Day, a national holiday.

1870 – The United States Department of Justice formally comes into existence.

1873 – Prince Edward Island joins into Canadian Confederation.

1874 – The Sholes and Glidden typewriter, the first commercially successful typewriter, goes on sale.

1878 – Canada joins the Universal Postal Union.

1879 – Charles Taze Russell publishes the first edition of the religious magazine The Watchtower.

1881 – The world's first international telephone call is made between St. Stephen, New Brunswick, Canada, and Calais, Maine, United States.

1881 – General Order 70, the culmination of the Cardwell and Childers reforms of the British Army, comes into effect.

1885 – The United States terminates reciprocity and fishery agreement with Canada.

1885 – The Congo Free State is established by King Leopold II of Belgium.

1890 – Canada and Bermuda are linked by telegraph cable.

1898 – Spanish–American War: The Battle of San Juan Hill is fought in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba.

1901 – French government enacts its anti-clerical legislation Law of Association prohibiting the formation of new monastic orders without governmental approval.

1903 – Start of first Tour de France bicycle race.

1908 – SOS is adopted as the international distress signal.

1911 – Germany despatches the gunship SMS Panther to Morocco, sparking the Agadir Crisis.

1915 – Leutnant Kurt Wintgens of the then-named German Deutsches Heer's Fliegertruppe army air service achieves the first known aerial victory with a synchronized machine-gun armed fighter plane, the Fokker M.5K/MG Eindecker.

1916 – World War I: First day on the Somme: On the first day of the Battle of the Somme 19,000 soldiers of the British Army are killed and 40,000 wounded.

1917 – Chinese General Zhang Xun seizes control of Beijing and restores the monarchy, installing Puyi, last emperor of the Qing dynasty, to the throne. The restoration is reversed just shy of two weeks later, when Republican troops regain control of the capital.

1921 – The Chinese Communist Party is founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao, with the help of the Far Eastern Bureau of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks), who seized power in Russia after the 1917 October Revolution, and the Far Eastern Secretariat of the Communist International.

1922 – The Great Railroad Strike of 1922 begins in the United States.

1923 – The Parliament of Canada suspends all Chinese immigration.

1931 – United Airlines begins service (as Boeing Air Transport).

1931 – Wiley Post and Harold Gatty become the first people to circumnavigate the globe in a single-engined monoplane aircraft.

1932 – Australia's national broadcaster, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, was formed.

1935 – Regina, Saskatchewan police and Royal Canadian Mounted Police ambush strikers participating in the On-to-Ottawa Trek.

1942 – World War II: First Battle of El Alamein.

1942 – The Australian Federal Government becomes the sole collector of income tax in Australia as State Income Tax is abolished.

1943 – The City of Tokyo and the Prefecture of Tokyo are both replaced by the Tokyo Metropolis.

1946 – Crossroads Able is the first postwar nuclear weapon test.

1947 – The Philippine Air Force is established.

1948 – Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Quaid-i-Azam) inaugurates Pakistan's central bank, the State Bank of Pakistan.

1949 – The merger of two princely states of India, Cochin and Travancore, into the state of Thiru-Kochi (later re-organized as Kerala) in the Indian Union ends more than 1,000 years of princely rule by the Cochin royal family.

1957 – The International Geophysical Year begins.

1958 – The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation links television broadcasting across Canada via microwave.

1958 – Flooding of Canada's Saint Lawrence Seaway begins.

1959 – Specific values for the international yard, avoirdupois pound and derived units (e.g. inch, mile and ounce) are adopted after agreement between the US, the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries.

1960 – The Trust Territory of Somaliland (the former Italian Somaliland) gains its independence from Italy. Concurrently, it unites as scheduled with the five-day-old State of Somaliland (the former British Somaliland) to form the Somali Republic.

1960 – Ghana becomes a republic and Kwame Nkrumah becomes its first President as Queen Elizabeth II ceases to be its head of state.

1962 – Independence of Rwanda and Burundi.

1963 – ZIP codes are introduced for United States mail.

1963 – The British Government admits that former diplomat Kim Philby had worked as a Soviet agent.

1966 – The first color television transmission in Canada takes place from Toronto.

1967 – Merger Treaty: The European Community is formally created out of a merger between the Common Market, the European Coal and Steel Community, and the European Atomic Energy Commission.

1968 – The United States Central Intelligence Agency's Phoenix Program is officially established.

1968 – The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons is signed in Washington, D.C., London and Moscow by sixty-two countries.

1968 – Formal separation of the United Auto Workers from the AFL–CIO in the United States.

1972 – The first Gay pride march in England takes place.

1976 – Portugal grants autonomy to Madeira.

1978 – The Northern Territory in Australia is granted self-government.

1979 – Sony introduces the Walkman.

1980 – "O Canada" officially becomes the national anthem of Canada.

1983 – A North Korean Ilyushin Il-62M jet en route to Conakry Airport in Guinea crashes into the Fouta Djallon mountains in Guinea-Bissau, killing all 23 people on board.

1983 – The Ministry of State Security is established as China's principal intelligence agency

1984 – The PG-13 rating is introduced by the MPAA.

1987 – The American radio station WFAN in New York City is launched as the world's first all-sports radio station.

1990 – German reunification: East Germany accepts the Deutsche Mark as its currency, thus uniting the economies of East and West Germany.

1991 – Cold War: The Warsaw Pact is officially dissolved at a meeting in Prague.

1997 – China resumes sovereignty over the city-state of Hong Kong, ending 156 years of British colonial rule. The handover ceremony is attended by British Prime Minister Tony Blair, Charles, Prince of Wales, Chinese President Jiang Zemin and U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

1999 – The Scottish Parliament is officially opened by Elizabeth II on the day that legislative powers are officially transferred from the old Scottish Office in London to the new devolved Scottish Executive in Edinburgh. In Wales, the powers of the Welsh Secretary are transferred to the National Assembly.

2002 – The International Criminal Court is established to prosecute individuals for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression.

2002 – Bashkirian Airlines Flight 2937, a Tupolev Tu-154, and DHL Flight 611, a Boeing 757, collide in mid-air over Überlingen, southern Germany, killing all 71 on board both planes.

2003 – Over 500,000 people protest against efforts to pass anti-sedition legislation in Hong Kong.

2004 – Saturn orbit insertion of Cassini–Huygens begins at 01:12 UTC and ends at 02:48 UTC.

2006 – The first operation of Qinghai–Tibet Railway is conducted in China.

2007 – Smoking in England is banned in all public indoor spaces.

2008 – Riots erupt in Mongolia in response to allegations of fraud surrounding the 2008 legislative elections.

2013 – Croatia becomes the 28th member of the European Union.

2020 – The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement replaces NAFTA.

1 note

·

View note

Text

National Security: Militaries Have Sought To Use Spy Balloons For Centuries. The Real Enemy Is The Wind

— February 17, 2023 | Geoff Brumfiel | NPR

The Pentagon's multi-billion-dollar program to develop advanced missile warning balloons is just one of many projects over the decades that has been sabotaged by a gusty breeze. Patrick Semansky/AP

The U.S. government is increasingly convinced that an alleged Chinese spy balloon was thousands of miles off of its intended course.

An official, speaking on condition of anonymity on Thursday, told NPR that the government now suspects the spy balloon was supposed to surveil Guam and Hawaii, but ended up flying over Alaska, Canada and eventually, the rest of the continental United States.

According to the official, the probable cause of the course deviation was one of the oldest foes faced by military balloons: the wind.

The balloon was first spotted by the public over Montana on Feb. 1. The U.S. military tracked it as it drifted across the country before an F-22 Raptor brought it down with an air-to-air missile three days later. China has maintained that it was an "unmanned civilian airship."

If the balloon's path really was a mistake, then the incident is just the latest in a long line of errant military balloons, which for over two centuries have been blown hither and thither by everything from breezes to gales

Generals have been put at risk, diplomatic relations strained, and millions of dollars of sensitive equipment ruined. And despite it all, nations just don't seem to be able to let go of their balloons.

Zeppelin Vs. Zephyr

The love affair with balloons started long before airplanes took flight. As early as 1794, the French army operated balloons during the Battle of Fleurus in combat against the Austrians. During the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln created the U.S. Army Balloon Corps to surveil the enemy.

When you're fighting a war, perspective matters, says Tom D. Crouch, an emeritus curator at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. "In military terms, it's always good to be able to get up high to see as much as you can behind the enemy lines," he says.

During the U.S. Civil War, observation balloons were used by the Union Army. They occasionally blew away, and sometimes blew back again. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

But for as long as there have been balloons, the wind has had something to say about where they fly. On April 11, 1862, during the siege of Yorktown, Virginia, a balloon carrying a Union general named Fitz John Porter came untethered and began drifting towards the Confederate position. Marksmen took a few potshots at the bobbing general as he floated over the enemy, Crouch says. "Fortunately, the winds shifted, and they were blown back over the Union lines."

Balloons continued to see regular use in conflicts through World War I, but it was nearly a century later, in the mid-1950s, that the U.S. government undertook a far more ambitious balloon surveillance project.

New, lightweight materials, such as mylar, allowed researchers to build balloons that could travel high into the stratosphere, near the edge of space. That technology, together with electronics and remote cameras meant that uncrewed balloons could potentially drift across enemy territory, providing views that, at the time, were unavailable any other way.

And the U.S. had one enemy in particular it wanted to watch: the Soviet Union.

"You would take special cameras, attach them to high-altitude balloons, set them adrift in Western Europe and let them drift over the Soviet Union," says Stephen Schwartz, a non-resident senior fellow at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

During the 1950s, the U.S. sent hundreds of spy balloons floating over the Soviet Union. A diplomatic spat ensued. Air and Space/Defense Visual Information Center

The goal, Schwartz says, was to fly over the vast Soviet homeland and collect intelligence on nuclear weapons. "We were terrified that the Soviet Union was going to unleash a surprise attack and we didn't know what they were really capable of, so any useful information would have been helpful," he says.

The culmination of these efforts was a top-secret program called Project Genetrix. Starting in January of 1956, the U.S. government began releasing dozens of high-altitude balloons from airbases in Germany and Turkey.

But it didn't last long.

"It was essentially a disaster," Schwartz says. And once again, the wind was to blame: "You had no idea where the balloons were going, so it was just hit or miss as to what you would see."

Genetrix balloons captured images of enormous tracts of Soviet farmland. And clouds. Lots of clouds.

Also, Balloons Are Really Easy To Shoot Down

In addition to being haphazard, the Genetrix balloons weren't very stealthy either, says Tom Crouch. U.S. intelligence "hoped that they could get by without the Soviets noticing," he says. "That didn't happen."

Within a month, Soviet air defenses were taking down balloons left and right. "They just shot them out of the sky," Crouch says. "They had big public exhibitions in Moscow of these balloon camera systems that the nefarious Americans were sending over the innocent Soviets."

The Air Force briefly tried to solve the problems with still more balloons. "They launched them in very large numbers, hoping that a significant number would get through," Crouch says.

“What did they think they were going to get with a balloon?” — Tom D. Crouch, Historian

In total, around 500 balloons were released, but the strategy quickly became unsustainable. In February, just barely a month after Project Genetrix began, the Soviets went public, protesting what they called "a gross violation of Soviet airspace." The once-top secret program was on the front page of the New York Times.

At the same time, Crouch says, the CIA was close to deploying a spy plane known as the U-2. The highly classified plane was capable of flying at altitudes far above normal aircraft, but not above the balloons. The intelligence agency became concerned that the balloons were drawing undue attention to that patch of the sky.

High altitude spy planes, like this U-2, quickly ended up replacing balloon surveillance. Airman Bailee Darbasie/99th Air Base Wing Public Affair

"They were worried that the Soviets were going to be so good at shooting things down and looking for things that the U-2 program would be compromised," he says.

In the end, President Dwight D. Eisenhower decided that the balloon program wasn't worth the headaches, and Project Genetrix ended almost as quickly as it began.

Can't Let Go

And yet, despite all the ups and downs, interest in surveillance balloons is still going strong. In July of last year, Politico reported that the Pentagon was looking at using surveillance balloons to again spy on China and Russia. The report says budget documents show it intends to spend $27.1 million this fiscal year to study the possibility.

A U.S. fighter jet flies near China's spy balloon just minutes before it was shot down over the Atlantic Ocean. Chad Fish/AP

But it's clear that the wind isn't backing down either. In addition to possibly having a hand in this latest diplomatic bust-up, it's been sabotaging other efforts. In 2015, a Pentagon surveillance balloon being tested at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds came unmoored and drifted into Pennsylvania, before coming down in a thicket of woods. Critics say the program cost the government more than $2 billion before it floated away.

Crouch, the retired historian, says he's watched the latest events with China's balloon unfold with a mix of bemusement and bewilderment.

It's now an age where satellites, planes, drones and cell phone cameras can give virtual views of almost any spot on the Earth.

"For heaven's sake," he asks, "what did they think they were going to get with a balloon?"

NPR's Greg Myre contributed to this report.

0 notes

Text

Versailles pretty… the Napoleon parts were pretty boring though and very salty that they didn’t put Saint-Just there but had the battle of fleurus in the big major(tm) historical battles area with a ton of, what I presume to be, military generals

0 notes

Text

"Nation in arms."

"As the Republic faltered in the face of foreign invasion, internal insurrection and economic crisis, the revolutionary leadership grew more radical. In June 1793, the Jacobin faction seized control of the government. Facing an extremely volatile domestic and international situation, the Jacobins called for extraordinary measures to protect the nation and the revolutionary ideals. They believed that only strong and centralized leadership could save the Republic. Such was provided by the twelve-member Committee of Public Safety (CPS), which introduced radical reforms to achieve greater social equality and political democracy and began imposing the government's authority throughout the nation through violent repression and terror.

In the interest of the nation's defense, the CPS launched a levée en masse- the masterwork of minister of war Lazare Carnot- that mobilized the resources of the entire nation. "From this moment until that in which the enemy shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic," stated the National Convention's decree of August 23, "all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the service of the armies." In a remarkable administrative feat, the revolutionary government had raised an astonishing fourteen new armies and equipped some 800,000 men within a year. The CPS introduced universal conscription of all single men ages eighteen to twenty-five, requisitioned supplies from individual citizens, and ensured that factories and mines produced at full capacity. The success of this mass mobilization was aided by a vast state propaganda that touted the levée en masse as a patriotic duty aimed at defending la patrie against tyranny and foreign threats. Citizens not privileged not bear arms and fight on the front line were encouraged to work harder to make up for it. These messages were spread via posters, broadsides, leaflets, and newspapers, while speakers and decorated veterans toured the country to rouse the masses. In creating the "nation in arms", the Jacobins heralded the emergence of modern warfare.

The citizens soldiers of the Republic proved their worth on the battlefields. In September 1793 General Jean Nicolas Houchard defeated the Anglo-Hanoverian army at Hondschoote in Flanders, while Jean-Baptiste Jourdan routed the Austrians at Wattignies on October 15-16, thus turning the tide of war against the First Coalition. Two months later the French army drove the Anglo-Spanish force out of the strategically important port of Toulon, where an obscure artillery major named Napoléon Bonaparte first distinguished himself. In the west of France, the revolutionary armies brutally suppressed the royalist revolt in the Vendée. After General Jourdan's victory at Fleurus on June 26, 1794, the French pushed back the Coalition forces along the northern frontier and reclaimed Belgium and the Rhineland; in January 1795 the Dutch Texel fleet of fourteen ships-of-the-line was trapped in ice and captured by a French squadron of hussars and an infantry company riding pillion behind them- the only example in history of a cavalry capturing a fleet."

Alexander Mikaberidze- The Napoleonic Wars, A Global History.

#wars of the revolution#alexander mikaberidze#the napoleonic wars: a global edition#lazare carnot#general houchard#jean-baptiste jourdan#battle of hondschoote#battle of wattignies#siege of toulon#battle of fleurus#and that day when hussars captured a fleet#that was quite a day#oh#and some artillery dude

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

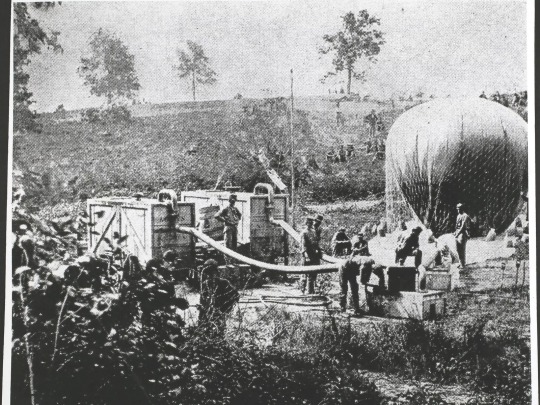

French military ballon of the Aerostatic Corps at the battle of Fleurus, 1794.

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jourdan's Achievements During the French Revolution (Part 3)

When Jourdan’s name is mentioned, what often comes to mind is his military career and his successes at the Battles of Wattignies and Fleurus. However, he was also active in politics from 1797 to 1799 as a member of the Council of Five Hundred. As much as I would like to examine Wattignies and Fleurus in detail (because I think it is admirable what Jourdan pulled off under pressure from the enemy and from the Convention and Committee), my time is sadly limited, so I will focus on the kind of contributions he on the debating floor rather than the battlefield. I continue to use Fischer’s Jacobin General as my source.

The Politician: Presidency of the Council of Five Hundred; Implementation of Conscription Law

Having been blamed for the defeats of the Armée de Sambre et Meuse so as to become unemployed in 1796, Jourdan headed into politics. He was made president of the electoral college of Haute Vienne and became one of its candidates for election to the Council of Five Hundred, which was created in 1795 and functioned as a legislative body. Jourdan was successfully made a deputy on a vote of 195 to 7. He sat on the left, which comprised of old remnants of the Jacobin party of 1793-1794, and which included his former colleagues from his time in the Armée du Nord and the Sambre et Meuse, as well as future Marshals Augereau and Bernadotte.

Jourdan supported the basic ideas of republicanism with a nationalist emphasis, and indeed first speech in the Five Hundred was anti-clerical (despite or because of the time he spent with his abbot uncle). He supported the coup of 18 Fructidor to oust the conservatives, and in staying loyal to the Republicans and Directory, was elected as president for two terms in total, though the role was largely symbolic (pp. 380-388). He was most active as the head of the military commission of the Five Hundred, “a sub-committee involved with all problems related to the French army”.

[W]e do know of the most important legislation that Jourdan dealt with. He proposed a bill suspending the appointment of any new staff officers or supply officials, the number of which had expanded from 8,000 to 25,000 over the preceding two years, gravely eating into the budget. In the same bill he proposed that the number of officers per staff be fixed at a given level to prevent superfluous aides fro m being promoted. The bill appears to have been passed since there was no further discussion on the subject. He also supported the agitation for a severance bonus for all veterans upon their retirement from the army. … Jourdan asserted that the bonus was not a "degrading salary" like the bounty then paid to volunteers, but a "just reward" for their good services. He further urged that the indigent families of dead or disabled soldiers receive some kind of pension. (pp. 390-391)

The most significant proposal Jourdan would make would be the institutionalisation of conscription, which was sorely needed.

Since the levée en masse in 1793 the government had enactec no legislation to provide the army with recruits nor had they bothered to draft additional men to replace those killed or crippled, or those who had deserted. As a result the army had shrunk from over 1,000,000 men in 1794 to 454,000 in 1796, mostly due to desertion, and declined even more following the Treaty of Luneville in 1797. Most replacements were volunteers induced to enlist for a bounty, and these were few enough. As the diplomatic situation deteriorated in the summer of 1798, the feebleness of the army became a subject of concern. ...

Obviously some form of conscription was necessary, no matter how distasteful this was to many of the Thermidorians. The alternatives were either to reestablish a professional army of paid mercenaries or to resort to the levée en masse in times of national crisis. The first was impossible because it smacked of the recruiting gangs and tyranny of the monarchy; the second was unpopular because it had been a measure of the Terror. Yet the left believed that the Republic dared not attempt to get by with a skeleton army. … Only a powerful army could deter the monarchies of the rest of Europe from attempting to overturn the verdict of 1 794. (pp. 391-393)

To combat this drain of manpower, Jourdan proposed for conscription (technically as a joint proposition between him and his former colleague Debrel).

On July 20, 1798, Jourdan proposed a bill that would draft a contingent of young men into the army on a yearly basis. The justification for the conscription was that all Frenchmen capable of bearing arms were responsible for the defense of their nation. The Revolution had granted them liberty, equality and full citizenship, and it was their duty to serve as soldiers to protect it. Jourdan argued that the alternative was a professional army, and that both the Roman Empire and the French Monarchy had demonstrated the dangers of dividing society into separate military and civilian castes. Should national security be turned over to professionals, not only would the citizens be at the mercy of a contemporary praetorian guard, they also would become prey to effeteness and degeneracy. "The base greed for money will replace the noble passion for glory; self love, love of nation: riches will become more important than virtue; and the Nation, enervated by luxury, will be prey to every ravisher." Like most career soldiers Jourdan considered military service beneficial, a strengthener of character, an instiller of discipline in young men. ...

The provisions of Jourdan's conscription law declared that all able bodied French males between the ages of twenty and twenty-five, except those married before January 12, 1798, were subject to military service. They were to be registered according to their ages in five classes. The legislature would decide at a given time how many conscripts were required, and the Minister of War would then call the necessary number to the colors beginning with the youngest class—those twenty years old. Jourdan argued that the youngest class should be called first because most would have completed their education or apprenticeships, but would not yet be involved with a family or career. Besides men at that age were best suited to bear the physical hardships of war. Each conscript was to serve five years, although chances were that he would not have to serve his fifth year. Each new class of men twenty years old was to replace those having finished their service. The municipal authorities of each arrondisement were to draw up draft lists of their citizens, while the war ministry compiled a master list, coordinated the other details of registration, and handled the actual call-up of the draftees. The conscripts were to be incorporated into veteran units as replacements—the amalgame perpetuated. Although volunteers were still to be accepted, Jourdan urged that the incentive bounty be done away with lest conscripts be tempted to enlist prior to receiving their draft notices in order to collect the bounty; volunteers should enlist out of patriotism, or out of a desire to pursue a military career. All draft evaders were to be treated as deserters, deprived of their civic rights, and subjected to arrest. (pp. 393-395)

The bill was only met with light opposition and made law on 19 September 1798. There were flaws in the law due to the allowance of locally-made decisions (which often neglected national interests) and inefficiencies of war beauracracy, but the loi Jourdan “marked a watershed in military history” (pp. 395-398). As the system was smoothed out, it effectively allowed Napoleon to supply his armies with men. It was a piece of infrastructure that allowed him to maintain the size and scale of his army, and the law’s impacts were felt beyond Napoleon’s fall.

It was the first modern draft law ever enacted; this fact alone explains its many rough edges. Its content and philosophy forshadowed the modern age, for the concept of obligatory military service for a nation's young men, so basic to the mass armies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was first articulated in the Jourdan law. Indeed, the arguments which he used to defend the bill, that defense of one's country was the duty of every citizen, that a professional army allowed a nation’s manhood to go soft and thus was dangerous to liberty, and that young men were physically and m entally best suited to undergo the rigors of military duty, can be found in any modern brochure defending the men its of conscription. The French theory of the nation in arms originated here. The Jourdan law has remained the basis for French conscription to the present day, and if the law has changed in particulars over the years, the fundamental fact of compulsory military service has remained in effect since 1872. (pp. 398-399)

While Jourdan’s achievements in the French Revolution, political or military, may seem negligible in now, they were not insignificant at the time. As mentioned in the previous two posts, Jourdan understood how to lead under the pressure of and in conjunction with conflicting interests, including that of a civilian government. Men like Jourdan brought time through their victories and the systems they implemented through legislation, however little and inefficient, which helped build the fledgling French Republic and turn it into the working apparatus that would greet Napoleon. If Jourdan is not a first-rate military commander or the ablest Marshal, he had at least the abilities to accomplish what was needed, when it was needed. Considering the era in which he made his mark, those abilities were noteworthy indeed.

Fin.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan (1762-1833) was a French general who held significant commands in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). He won a major victory for the French Republic at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794 and was among the first 14 men to be appointed marshal of the empire by Napoleon I in 1804.

Continue reading...

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

The real marshals, according to Thiébault

General Thiébault in his memoirs is quite outspoken about those whom he considers worthy of the title »marshal«, and of those he does not. It’s an interesting list.

Yes, to make such a dignity worthy of envy, it was necessary to award it at all times to the most deserving, that is to say, to Masséna first, to Saint-Cyr, as great tactician; to Kellermann, as the victor of Valmy; Jourdan, as the victor of Wattignies and Fleurus; Lannes, as man of inspiration; Bernadotte and Suchet, as men of capacity; Ney, as a man of vigour; Murat, as a man of valour; this is the honour of our marshal's baton, an honour to which Dumouriez, Pichegru, Moreau, as soldiers, not as Frenchmen, Hoche, Marceau, Championnet, Dugommier, Kléber, Desaix, Joubert, if they were not already dead, and Vandamme, if he had been appointed, would have been added but, under the Empire, Soult, a man of cabinet, not of battle, Berthier, Pérignon, Sérurier, Augereau, Lefebvre, Bessières, Mortier, in spite of his coup de collier at Krems, Brune, whose success in Switzerland cannot be described by the word victory, and who in Holland only defeated the English thanks only to the vigour of Vandamme, as Davout defeated the Prussians at Auerstædt thanks only to the generals Legrand, Morand and Gudin who commanded his divisions, Marmont, Macdonald, Oudinot, despite his chivalrous valour, Grouchy, and, under the Restoration, Clarke, Beurnonville, Vioménil, Maison; such choices scandalize instead of enlighten; they tarnish the lustre which the great dignity of the marshalate would have had without them, and, to return to the first promotion, when he received this dignity, which thirty-six years later Sébastiani was to complete to bring it down, I remember the tone, half of anger, half of disdain, with which General Masséna replied to my congratulations with this quip: "We are fourteen!"

So, according to Thiébault the only real marshals were

Masséna

Lannes

Ney

Murat

Bernadotte

Suchet

Saint-Cyr

Kellermann

Jourdan

I guess there’s little discussion about the first four. The others I find at least somewhat surprising. As to those missing, I’m not surprised about Berthier and Soult, he hated both. His hatred of Brune astonishes me, but the real shock of course is Davout.

47 notes

·

View notes