#jean baptiste jourdan

Text

Murat and Bessières at school

Still looking for something for @flowwochair, I came across this very brief remark in the memoirs of general Jean Sarrazin (more about him below):

When I was seven, my father took me to the college in Cahors, the capital of the Lot department. My father chose this college in preference to the one in Agen, on the advice of the Comte de Fumel, whose tenant he was. [...] I was raised with Murat, Bessières and Andral, with whom I was friends. Bessières was well-behaved, a little Cato. Murat was a scatterbrain, boisterous and concerned only with his own pleasures. He was a true Paris brat (gamin de Paris).

Now, I assume this author is a highly suspicious source. Not only because he, obviously, is yet another Gascon, but mostly because he, after having served in the Revolutionary and Imperial army, defected to the British in 1810, and supplied them with plenty of information on Napoleon’s plans and the most prominent leaders of his army. As a matter of fact, in 1811 he had a book published with descriptions of several prominent figures in France, called "The Philosopher", the first chapter of which is dedicated to Marshal Soult, who was probably the most interesting to the British due to him being their main opponent in Spain, and who in this book receives much more praise than is due to him. While much of it may be plain wrong or at least cannot be verified, I feel like it’s an interesting insight into what people in the army at the time thought about these folks.

Among other things, Sarrazin gives a long description of the battle of Fleurus, with some interesting twists. Mostly he claims that Lefebvre owed his reputation as a great general only to Soult, who at the time was his chief-of-staff, and even has general Marceau exclaim that Soult had won the battle of Fleurus for them. This is completely opposite to Soult’s own memoirs, where Soult has nothing but praise for Lefebvre’s actions during the battle of Fleurus, and barely mentions his own. However, there seems to be some truth to Soult coming to the aid of one rather desperate general Marceau, as Soult mentions this, too, though in a very different context.

The demand to detach some troops at a very inopportune moment is made in Soult’s memoirs as well – but not by Marceau, but by Saint-Just. And it’s not Lefebvre and Soult who refuse, but Jourdan (whom Soult praises a lot for having had the courage to stand up to what he calls "Saint-Just's presumptuous ignorance"). I am not sure in how far these memoirs are influenced by Soult’s own long life and his own political situation, but he clearly despises Saint-Just. According to his memoirs, the whole officers’ corps was shaking with fear while the politicians were with them, literally scared to death. In front of Charleroi, one artillery capitaine allegedly was executed for having failed to meet the schedule Saint-Just had set for him.

Again, I have no clue what this is based on. But I thought it worth mentioning, maybe somebody from the Frev community can shed some light onto this incident.

(Personally, I feel like Soult may be projecting here a little of "Joseph's presumptuous ignorance" onto another episode of his life 😋)

#napoleon's marshals#jean de dieu soult#battle of fleurus#1794#saint just#francois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste jourdan#frev

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

A fun little ask: the Marshalate is informed there is cake in the break room. How do each of them react?

Who ever you are, thank you for this sweet little question and I apologise for my late response. 🙈💕

I have ideas for some of them, however I am **not** aware of the maréchals eating habits so any input is welcome here. Also, I don't know all of the marshals well enough but I will try to include as many as possible. Don’t expect any historical accuracy in this.

See this post as a very big headcanon and as one ongoing story where I am going to try to mimic the marshals characters and miserably fail.

Shall we begin? :D

Les Maréchals and cake

Berthier would hear about it and quietly get excited by the idea of having a nice little piece of cake, just for him to be too busy with everything so that he isn't able to leave his desk. Either this or someone (probably one of his adcs) would be nice enough to get for Berthier his piece of cake.

Murat: You bet he is one of the first ones to look at this cake. His reaction might depend on how the cake looks. If it's a huge cake with a lot of golden details, Murat will carry it around so everyone admires this phenomenal cake because it deserves to be looked at.

Augerau and Masséna wonder why there is such a fancy a cake in the break room in the first place and who might have put it there. Augerau asks Masséna with a low voice: “How much money do you want to bet on the cake being poisoned?” Before Masséna is able to answer, Lannes enters the scene.

Lannes runs after Murat with the cake knife demanding to finally get his damn piece of this cake while Murat can't make himself to cut it because this cake is “so damn beautiful that it would be a waste to eat it.” This little game goes on for a minute or two until the other marshals grow impatient, one of them being Ney.

Ney who is known for his hotheadedness tries to save this cake from a disaster aaaaand fails. :) The three of them dispute over who is the actual culprit of this mess.

L: Murat, what have you done?

M: I have done nothing. You followed me with a knife.

N: You let the cake fall.

M: You intervened in my business with Lannes.

The cake has fallen to the ground as Davout, Suchet and Macdonald watched. “Aaand here goes the cake”, Macdonald says; “At least the floor was able to taste it.”

Suchet asks: “What do you think was its flavour?”

”Chocolate vanilla.” Davout answers. After a moment of silence, he adds. “Soult has a good recipe.”

Mortier walks in, seeing how Lannes, Murat and Ney are loudly disputing while Masséna and Augerau get themselves black coffee and Davout, Suchet and Macdonald talking. Lefebvre who was walking right behind Mortier gestures him to move away from the door so he can get into the break room: “What is going on?”

Suchet: “We found a cake-“ Davout interrupts him: “We found a chocolate vanilla cake which we don’t know how it got here or if it was poisoned and now it’s inedible because his royal highness, the King of Naples, made it fall.”

Murat shouts from the back: “I didn’t let it fall.”

Lannes: “Oh, you did.”

Lefebvre offers a solution like the good fatherly figure he is: “Do you still want cake? We could bake a new cake, messieurs.”

Davout replies: “This sounds like a smart idea, Monsieur. Maréchal Soult knows an excellent recipe.”

Lefebvre: “Ahh, excellent. Where is our maréchal?”

Mortier: “He is in his office.”

“Then this where our journey goes next.” Lefebvre slams the door open and accidentally hits Oudinot. “Ah, Monsieur, my apologies. If I had known you were there, I wouldn’t have slammed the door as hard as I did. Are you alright? Yes? Until the next time then.”

Davout walks up to his friend to make sure how Oudinot is doing and explains to him in the meanwhile what is going on and also promises Oudinot to bring him a piece of the cake they are going to bake.

Lefebvre takes the lead and walks straight to Soult’s office while Davout and Mortier follow him. Suchet decides to stay behind while Macdonald thinks about it.

Lefebvre knocks on Soult’s office door: “Monsieur, le maréchal? Are you here?” *Lefebvre knocks again with his energetic manner.* “Monsieur, le maréchal, it’s me, Lefebvre. Open the door!*

Soult opens the door with his usual unimpressed demeaner: Hm?

Lefebvre: “Excusez-moi, mon maréchal, I heard you have a recipe for a delicious cake?”

Soult: Cake? What cake?

Davout: The chocolate vanilla one… the one you baked for your daughter Hortense’s birthday. The delicious one.

Soult: Ah, yeah. That one. What of it?

Mortier: We would like to bake this cake, which is why we want to ask if you mind us borrowing the recipe?

Soult stares at his co-maréchals for a second, he shuts the door, opens it again with a piece of paper in his hand which he gives to Lefebvre. “Here. Is there anything else you need?”

Macdonald who decided to join the baking group walks up to them and asks Soult: “Would you mind to lend us your baking equipment?”

- “No. Have a nice day.”

Soult shuts his door while Lefebvre shouts: “Thank you for your help, Monsieur Soult.”

Macdonald asks: “What are we going to do now?”

“We are going to bake the cake now, my good friend”, Davout answers.

Mac: “Where? Where do you want us to bake the cake? Do we have the right ingredients?”

D: In the kitchen and I don’t see why we shouldn’t have the ingredients.

Macdonald looks at Davout with suspicious eyes about the matter if they are going to manage to bake this cake…

The group of maréchals appear in the imperial kitchen where they start to gather the right ingredients. While the group is busy with the preparations, les maréchals Pérignon and Sérurier appear, wondering what is going on. As Lefebvre is explaining these two their baking journey up until now, Pérignon and Sérurier decide to join them: “A cake made by maréchals for maréchals.”

What could possibly go wrong with two additional heads in the kitchen? As it turns out: Everything.

Pérignon and Sérurier manage to overdo the cake by confusing salt with sugar. The cake tastes salty, the icing itself is fine because it was made by Davout who religiously followed Soult’s directions. In addition to that, monsieur Lefebvre manages to mix up usual paper with baking sheets.

Bernadotte walks into the kitchen as he sees his fellow maréchals working on their baking project. He comments on the scenery: “This is just pure chaos without any discipline, a chaos which can’t possibly create something edible.”

Davout replies “Well, have you ever baked anything in your miserable existence which you so call your life?”; to which Bernadotte says: “wELL, no, BUT-“

Davout continues: “Then get out of this room and give me my peace back or shut up.” Bernadotte decides to leave.

As Bernadotte is leaving, Jourdan walks right into the scene with an apple in his hand. A fire starts to break out in the oven and Jourdan, like the team player he is, turns and leaves this mess to his co-maréchals without saying one word.

Nothing is going as Davout had it planned. He sits in a corner, mourning this beautiful chocolate vanilla cake he had in mind. Macdonald sits right next to him with a spoon, telling him: “Well, at least the frosting you made yourself is delicious.”

Davout, completely shattered by the fact that he wasn’t able to make his desired chocolate vanilla cake, puts his face into his palms until a surprise visits the kitchen: It’s maréchal Soult. With a cake. A chocolate vanilla cake. A chocolate vanilla cake which is neither burnt nor oversalted. A chocolate vanilla cake according to the recipe. Next to Soult is Oudinot who cuts two pieces of the cake: one for himself and one for his good old friend, Louis Nicolas Davout.

After Soult, Ney and Lannes enter the kitchen. Ney silently takes a piece of Soult’s cake, saying nothing except a simple “thank you”. So do Macdonald and Mortier. Soult tolerates Ney’s presence. Lannes on the other hand goes straight to the oversalted and burnt cake which the older maréchals made and are also eating. Kellermann and Grouchy, as late to the party as ever, also go for Lefebvre’s bad cake while Soult’s good cake is still sitting there. Soult can’t hide his look of disgust.

At some point, Bessières and Murat join or rejoin retrospectively the scene, walking up to Soult’s cake. Bessières, as well mannered as he is, takes one piece of a cake to which Murat comments: “I know how much you like this lovely type of cake, Bessières, take a second piece.”

- “No”, Soult replies: “That’s not your cake. Take your piece and leave.”

Murat adds: “For whom are the other pieces then? I don’t see anybody who would possibly want to eat this gorgeous baked good. We want to eat your delicious creation of a fabulous cake.”

- “One piece each. You can give him your piece if you like to.”

Bessières interrupts the two: “I am content with my piece.”

Murat doesn’t listen to what Bessières says and continues his conversation with Soult: “My fellow maréchal, I don’t understand, why do you struggle so much with allowing somebody to have one additional piece of cake than the other ones?”

While Murat and Soult continue their dispute which leads to nowhere, one adc enters slowly the kitchen. He looks at Soult who recognises this man as one of Berthier’s adcs. He came to get a piece of cake for his marshal. Soult lets him take one of the few pieces left.

All of a sudden, Kellermann seems to be chocking on his salty cake piece. All the maréchals are gathering around him and in the chaos, the last few pieces of Soult’s cake fall to the ground. Soult looks at his cake or what’s left of it. One could argue that everyone who wanted to eat it was able to eat it. One could argue that these fallen pieces can be ignored and Soult could go on with his day never ever thinking about the pieces again. However, we are talking about maréchal Soult here who sees the art in baking. The love, the accuracy of it. Today he didn’t just bring cake to his fellow maréchals. Today he witnessed how some of them have no sense of dignity for what it means to be able to eat good food. Good cake. Soult is leaving the room, not bothered about Kellermann as he wouldn’t be able to help anyway. He is going to his wife, his Louise Berg, who asks him about his day. He tells her the whole of it. How he was surprised by his fellow maréchals who wanted to bake a cake. How he knew that they are going to mess up his recipe. How he baked that cake properly and how a part of it went to waste. “Some of them ate oversalted and burnt cake. Who eats bad cake? Who likes bad cake???”

Davout on the other hand was thankful for Soult. With a smile on his face, Davout enjoyed his so desired chocolate vanilla cake, unbothered by the event surrounding him.

The end. :)

#Napoleonic headcanon#headcanon#napoleonic#louis alexander berthier#joachim murat#charles pierre augerau#andré masséna#jean lannes#michel ney#louis nicolas davout#louis gabriel suchet#étienne macdonald#édouard mortier#nicolas charles oudinot#françois joseph lefebvre#jean baptiste bernadotte#jean baptiste bessières#jean baptiste jourdan#jean de dieu soult#louise berg soult#And the rest :)#i am too tired for this#i hope you like it#cake

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jourdan's Achievements During the French Revolution (Part 1)

Marshal Jourdan seems to be one of the twenty-six that gets overlooked because most of his achievements came before the Napoleon's ascendancy, which rather underrates him in my opinion. As it is his birthday around this time of the year, I would like to dedicate a few posts to some of his qualities and his most significant accomplishments from the Revolutionary era, which did much to ensure the French army's supremacy when Napoleon gained power.

I use as my source a 1978 PhD dissertation titled Jacobin General; Jean Baptiste Jourdan and the French Revolution, 1792-1799, by one Lawrence Joseph Fischer. Clocking in at a little less than 500 pages, it tells you more than you could ever possibly want to know about Jourdan during those years (or perhaps not, if you are a fervent Jourdan admirer). Working my way through it has greatly increased by appreciation of the Marshal. The dissertation seems to be a relatively balanced assessment of the times in which Jourdan held command, so if you are interested in Jourdan or the (dis)organisation of the armies of the French Revolution in general, it may be worth a look.

Now, let us begin.

---

The Team Player: Appointment to General in Chief of the Armée d Nord

As I briefly touched on in one of my previous posts, the French military was in a dire situation during the Revolution owing to multiple factors that brought chaos. The second levée en masse, which drew the army’s men from the common populace, often lacking in military discipline, was implemented with confusion. Furthermore, the sheer number of men that needed to be incorporated exacerbated the logistical problems of equipping, feeding, and training them. At the same time, the Convention and Committee of Public Safety was purging officers in the hopes of getting rid of incompetents and useless aristocrats, but ended up with some collateral damage as some innocent officers were barred from service and even executed. This caused a shortage of officers as existing officers demurred promotions for fear of their reputations and lives, while freshly promoted ones sometimes proved inadequate to the task.

"Inferior in number to the Allies, especially in cavalry, the army indeed was in a pitiful condition," Jourdan recalled of the command that he assumed [in his 1793 memoirs]. "The generals and superior officers, having risen in rank in but a few months from the subaltern ranks to higher grades, possessed only their zeal and their courage. The troops were denuded of equipment and clothing [and here he might have added food], and the arsenals were lacking arms and munitions . . .The older regiments, not having received any recruits for a long time, were reduced to half their strength… The greatest number [of the conscripts] were only furnished with sticks and pikes. Nonetheless, as they judged the state of affairs, the Committee of the government, which based the strength of the Republic upon the multitude, believed that it [the army] could accomplish the greatest things.” (p. 87)

The dissertation then goes into the specifics of how badly the army was faring and it is A Read. There are multiple mentions of weaponry, clothing, and food shortages, with troops literally starving to death at one point, not to mention the general insubordination and desertion—far cry from the armies Napoleon would take command of. So how did Jourdan face this task? He first did what many other Marshals might have thought unthinkable: to sacrifice his ego for a greater benefit.

In selecting Jourdan for the command of the Nord the government could not have made a more fortunate choice. e was, above all, a team man. He possessed none of the arrogance, pride, and intolerance that would have prevented him from working harmoniously with others, be they politicians, generals, or common soldiers. He was a warm and sympathetic person, evidently with an easy personality and an ability not only to suffer opposing points of view but also to defer to them when necessary. He yielded gracefully to orders even when they proved vexing or difficult. The fact that he took orders from civilians did not trouble him; he possessed none of the soldier's traditional hostility towards the meddling of civilian politicians in matters which he believed should be reserved for the military expert. When offering advice, he did so with almost painful diffidence. 'I submit these considerations to you because I think them to be in the best interests of the Republic', he would so often write, but 'be assured that whatever course of action you decide upon I will obediently carry out'. Then as an added precaution he would reassure his superiors of his loyalty and devotion to the regime. Jourdan was very careful not to repeat Custine's mistake and cause the government to suspect his patriotism. Like everyone, he had a point at which unreasonable superiors or incompetent subordinates would exhaust his patience. Fortunately, given the circumstances, he had a high threshold of tolerance.

Jourdan's ability to work with others was not limited to his superiors. He also got along well with his subordinates, be they generals or privates. The continuing loyalty of the officers who served under him in the Nord and in the Sambre et Meuse and the affection that the common soldiers always had for him even in the most dire of circumstances were mute testimony to his ability to deal with his men with understanding, tact and humanity. His long years of privation and his experiences in the ranks of the Royal army enabled him to empathize with the average man in the ranks. At the same time he had doubtlessly served with malingerers and chronic discipline problems, and he well knew that the only way to deal with such persons was with tough, unrelenting discipline. Additionally, he possessed the ability always to display what one might call a positive attitude. If he doubted his ability to cope with the army's problems, he did not show it. He did not duplicate Houchard's mistake of criticizing himself in his dispatches in an effort to persuade the government to shift the responsibilities of his command from his shoulders. Only once did he commit this error. During the appalling hardships of the November [1793] offensive, he became so disgusted that he threatened to resign his post; the government very nearly dismissed and arrested him, and he never made the mistake again. (pp. 90-92)

Jourdan also got along with his civil superiors: Lazare Carnot, member of the Committee of Public Safety; Bouchotte, Minister of War; and the representatives on the field with him. The last was particularly important.

Without the work of the representatives, the reorganization of the Nord would have been indefinitely delayed, if ever completed at all. The representatives grappled with a bewildering variety of organizational and logistical problems which were simply beyond Jourdan's resources to handle. They saw to the feeding and equipping of the army, the supervising of the supply personnel, and the discipling of foot-dragging departments which were not sending the army their assigned food quotas. They worked to execute the levée, and they helped to implement the amalgame. They consulted with Jourdan in the hiring and firing of officers and supply officials, and repaired and provisioned fortresses. In a given week one representative might discover a planned night assault betrayed to the enemy by a traitor who lit a telltale bonfire; another might purge the municipality of a front-line commune of aristocrats, malingerers, and other suspects; and a third might urge the government to deliver the back pay of the personnel of a certain administration. Like all administrators they made mistakes and committed abuses. Some were too quick to dismiss an officer for failures which were beyond the latter's ability to avoid. But on the whole their account sheet shows an overwhelming balance on the credit side of the ledger.

Jourdan did not hesitate to work with the representatives. ... The representatives could press the Committee for action in a certain area with far more vigor than could Jourdan, and they could shift some of the intense responsibility from the general's shoulders to their own. As they labored among the troops, they came to realize the extent and gravity of their problems as well as did the generals. In the struggle against disorganization, indiscipline, and the presumption of the extremists, men like Delbrel, Duquesnoy and Levasseur were Jourdan's most valuable allies. (pp. 99-101)

Jourdan would also have to deal with the more extreme commissaires, who were sent by Bouchotte to root out those unfaithful to the government. They had an almost pathological phobia of generalships, which they considered as belonging to the “nature of monarchy”. They often hindered Jourdan’s day-to-day work, but he managed to preserve his position from his cooperative nature (pp. 101-104). His determination to make the situation work within the parameters he was given would help him immensely in organising his army.

Tbc in Part 2.

#jean baptiste jourdan#wars of the revolution#french revolution#why jourdan mattered#sorry this is so late!!!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday Marshal Jourdan! April 29, 1762

#napoleonic marshals#jourdan#marshal jourdan#jean-baptiste jourdan#painting by eugene charpentier#happy birthday

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jourdan Dunn - Isabel Marant - Paris Fashion Week PAP AW23 by Jean Baptiste Soulliat

Book┃IG

#AW23#Fashion#Fashion week paris#Isabel Marant#Jean Baptiste Soulliat#Jourdan Dunn#Katrina Liksnite#Model#Models#Paris#Paris Fashion Week#Streetstyle#mode#pfw#portrait#pret à porter

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday, Marshal Jourdan!

My life still being shambolic at the moment, I have not done my slice-of-Marshal-Jourdan’s-life post as I had planned. I know what I have in mind, which is the reason he joined the army when in his teens (hint: escaping unhappy circumstances).

Jourdan is one of many Marshals who was orphaned at a young age. I can’t name all the others off the top of my head, but I know there were several, most notably our next birthday boy Massena. Like Massena, Jourdan is also one of the Marshals who went to America, Berthier being another. Maybe one day I will create a table of similarities and comparisons between the Marshals.

In the meantime, my Oudinot and Jourdan birthday posts will have to wait a few more days. But please don’t follow my sorry example, don’t leave Jourdan all alone at his birthday party!

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nina Ricci

Shoes: Charles Jourdan

Marie France, December 1991

Photographed by Jean-Baptiste Leroux

#Nina Ricci#vintage Nina Ricci#90s Nina Ricci#1990s Nina Ricci#Charles Jourdan#vintage fashion photography#vintage fashion#vintage style#90s fashion#90s style#1990s fashion#1990s style#90s#1990s

901 notes

·

View notes

Text

VOTE FOR A MARSHAL OF THE EMPIRE!!!

SINCE WERE NOT GOING TO APPEAR FOR AGES IN THAT OFFICIAL TOURNAMENT AND THE EMPEROR JUST GOT ROYALLED FUCKED THERE BY A VANISHED ROAST BEEF

HERES A BALLOT JUST FOR US MARSHALS OF THE EMPIRE!!

IN CASE YOU DONT KNOW WHO WE ARE WE'RE THE TOP MILITARY COMMANDERS PROMOTED BY NAPOLEON HIMSELF

AND WE HAVE REALLY BIG HATS

VOTE FOR WHOEEVER THE FUCK YOU WANT WHETHER THATS THE BEST OR THE SEXIEST OR THE MOST PATHETIC I DONT CARE

YOU KNOW YOU WANT TO VOTE FOR ME THOUGH!!!

GO AHEAD AND POST ALL THE PROPAGRANDA YOU WANT, THE ADC WILL SHARE IT IF ITS FUNNY

SORRY TO MONCEY, JOURDAN, BERNADOTTE, BRUNE, MORTIER, KELLERMAN, PERIGNON, SERURIER, VICTOR, MACDONALD, OUDINOT, MARMONT, SUCHET, SAINT-CYR AND GROUCHY, MAYBE WELL HAVE A PITY POLLE LATER

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

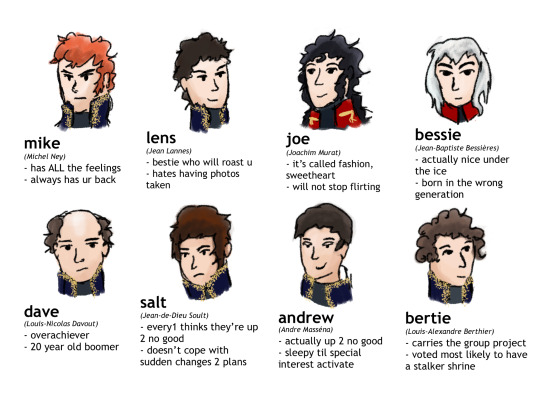

Tag Yourself: Unabridged Shitty Drawing Marshal of the Empire Edition

Yes All 26 Of Them + Bonus 2

drawn and compiled by yours truly, initial and probably inaccurate research assisted by Chet Jean-Paul Tee, additional research from Napoleon and his Marshals by A G MacDonnell, Swords Around A Throne by John R Elting and a bunch of other books and Wikipedia pages

captions under images

mike (Michel Ney)

- full of every emotion

- always has ur back

joe (Joachim Murat)

- it's called fashion sweetheart

- will not stop flirting

lens (Jean Lannes)

- bestie who will call u out on ur shit

- does not like their photo taken

bessie (Jean-Baptiste Bessieres)

- actually nice under the ice

- was born in the wrong generation

dave (Louis-Nicolas Davout)

- overachiever

- 20 year old boomer

salt (Jean-de-Dieu Soult)

- people think ur up to no good

- doesn’t cope with sudden changes 2 plans

andrew (Andre Massena)

- actually up to no good

- sleepy until special interest is activated

bertie (Louis-Alexandre Berthier)

- carries the group project

- voted most likely to make a stalker shrine

auggie (Pierre Augereau)

- shady past full of batshit stories

- will not stop swearing in the christian minecraft server

lefrank (François Joseph Lefebvre)

- dad friend

- in my day we walked to school uphill both ways

big mac (Étienne Macdonald)

- brutally honest

- won't let you borrow their charger even if they have 100%

gill (Guillaume Brune)

- love-hate relationship with group chats

- pretends not to care, checks social media every 2 minutes

ouchie (Nicholas Oudinot)

- needs to buy bandages in bulk

- a little aggro

pony (Józef Antoni Poniatowski)

- can't swim

- tries 2 hard to fit in, everyone secretly loves them anyway

grumpy (Emmanuel de Grouchy)

- can't find them when u need them

- complains about the music, never suggests alternatives

bernie (Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte)

- always talks about their other friendship group

- most successful, nobody knows how

monty (Auguste de Marmont)

- does not save u a seat

- causes drama and then lurks in the background

monch (Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey)

- last to leave the party

- dependable

morty (Édouard Mortier)

- everyone looks up 2 them literally and figuratively

- golden retriever friend

jordan (Jean-Baptiste Jourdan)

- volunteers other people for things

- has 20+ alarms but still oversleeps

kelly (François Christophe de Kellermann)

- old as balls but still got it

- waiting in the wings

gov (Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr)

- infuriatingly modest about their art skills

- thinks too much before they speak

perry (Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon)

- low-key rich, only buys things on sale

- “let’s order pizza” solution to everything

sachet (Louis-Gabriel Suchet)

- dependable friend who always brings snacks

- lowkey keeps the group together

cereal (Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier)

- unnervingly methodical and precise about fun

- will delete your social media after u die

vic (Claude Victor-Perrin)

- loves spicy food but can’t handle it

- says they're fine, not actually fine

Bonus!

june (Jean Andoche Junot)

- chaotic disaster bisexual

- will kill a man 4 their bestie

the rock (Géraud Duroc)

- keeps a tidy house

- mom friend with snacks

#napoleon’s marshals#napoleonic era#napoleonic shitposting#napoleonic wars#history shitposting#cadmus draws#I thought it would be funny if it was hand drawn#i had to draw these over a few weeks or else my RSI ridden fingers would explode#I will reblog this a few times because this is so stupid and I’m proud of this#yes chatgpt helped because I’m not actually familiar with most of the 26#ended up editing a lot of it but some entries are less based on history and more based on vibes#and as we know vibes are extremely accurate

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friends, enemies, comrades, Jacobins, Monarchist, Bonapartists, gather round. We have an important announcement:

The continent is beset with war. A tenacious general from Corsica has ignited conflict from Madrid to Moscow and made ancient dynasties tremble. Depending on your particular political leanings, this is either the triumph of a great man out of the chaos of The Terror, a betrayal of the values of the French Revolution, or the rule of the greatest upstart tyrant since Caesar.

But, our grand tournament is here to ask the most important question: Now that the flower of European nobility is arrayed on the battlefield in the sexiest uniforms that European history has yet produced (or indeed, may ever produce), who is the most fuckable?

The bracket is here: full bracket and just quadrant I

Want to nominate someone from the Western Hemisphere who was involved in the ever so sexy dismantling of the Spanish empire? (or the Portuguese or French American colonies as well) You can do it here

The People have created this list of nominees:

France:

Jean Lannes

Josephine de Beauharnais

Thérésa Tallien

Jean-Andoche Junot

Joseph Fouché

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand

Joachim Murat

Michel Ney

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (Charles XIV of Sweden)

Louis-Francois Lejeune

Pierre Jacques Étienne Cambrinne

Napoleon I

Marshal Louis-Gabriel Suchet

Jacques de Trobriand

Jean de dieu soult.

François-Étienne-Christophe Kellermann

17.Louis Davout

Pauline Bonaparte, Duchess of Guastalla

Eugène de Beauharnais

Jean-Baptiste Bessières

Antoine-Jean Gros

Jérôme Bonaparte

Andrea Masséna

Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle

Germaine de Staël

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

René de Traviere (The Purple Mask)

Claude Victor Perrin

Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

François Joseph Lefebvre

Major Andre Cotard (Hornblower Series)

Edouard Mortier

Hippolyte Charles

Nicolas Charles Oudinot

Emmanuel de Grouchy

Pierre-Charles Villeneuve

Géraud Duroc

Georges Pontmercy (Les Mis)

Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont

Juliette Récamier

Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Étienne Jacques-Joseph-Alexandre Macdonald

Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

Catherine Dominique de Pérignon

Guillaume Marie-Anne Brune

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Charles-Pierre Augereau

Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais

England:

Richard Sharpe (The Sharpe Series)

Tom Pullings (Master and Commander)

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Jonathan Strange (Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell)

Captain Jack Aubrey (Aubrey/Maturin books)

Horatio Hornblower (the Hornblower Books)

William Laurence (The Temeraire Series)

Henry Paget, 1st Marquess of Anglesey

Beau Brummell

Emma, Lady Hamilton

Benjamin Bathurst

Horatio Nelson

Admiral Edward Pellew

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke

Sidney Smith

Percy Smythe, 6th Viscount Strangford

George IV

Capt. Anthony Trumbull (The Pride and the Passion)

Barbara Childe (An Infamous Army)

Doctor Maturin (Aubrey/Maturin books)

William Pitt the Younger

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry (Lord Castlereagh)

George Canning

Scotland:

Thomas Cochrane

Colquhoun Grant

Ireland:

Arthur O'Connor

Thomas Russell

Robert Emmet

Austria:

Klemens von Metternich

Friedrich Bianchi, Duke of Casalanza

Franz I/II

Archduke Karl

Marie Louise

Franz Grillparzer

Wilhelmine von Biron

Poland:

Wincenty Krasiński

Józef Antoni Poniatowski

Józef Zajączek

Maria Walewska

Władysław Franciszek Jabłonowski

Adam Jerzy Czartoryski

Antoni Amilkar Kosiński

Zofia Czartoryska-Zamoyska

Stanislaw Kurcyusz

Russia:

Alexander I Pavlovich

Alexander Andreevich Durov

Prince Andrei (War and Peace)

Pyotr Bagration

Mikhail Miloradovich

Levin August von Bennigsen

Pavel Stroganov

Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna

Karl Wilhelm von Toll

Dmitri Kuruta

Alexander Alexeevich Tuchkov

Barclay de Tolly

Fyodor Grigorevich Gogel

Ekaterina Pavlovna Bagration

Ippolit Kuragin (War and Peace)

Prussia:

Louise von Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Gebard von Blücher

Carl von Clausewitz

Frederick William III

Gerhard von Scharnhorst

Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

Friederike of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Alexander von Humboldt

Dorothea von Biron

The Netherlands:

Ida St Elme

Wiliam, Prince of Orange

The Papal States:

Pius VII

Portugal:

João Severiano Maciel da Costa

Spain:

Juan Martín Díez

José de Palafox

Inês Bilbatua (Goya's Ghosts)

Haiti:

Alexandre Pétion

Sardinia:

Vittorio Emanuele I

Lombardy:

Alessandro Manzoni

Denmark:

Frederik VI

Sweden:

Gustav IV Adolph

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desaix / ドゼー and Clive / クレーベ

Desaix (JP: ドゼー; rōmaji: dozē) is the chancellor of Zofia who stages a coup of the kingdom in Fire Emblem: Gaiden and Echoes: Shadows of Valentia. He is named after Louis Desaix (JP: ルイ・ドゼー; rōmaji: rui dozē), one of the most highly regarded generals of the French Revolutionary Wars. Born into a noble house, Desaix began his military training at age eight. By age 15 he was a second lieutenant. After the Revolution began, he served under Victor de Broglie, chief of staff of the Army on the Rhine. Desaix would quickly ascend through the military, serving as a commander under Jean-Baptiste Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau during the invasion of Bavaria. Soon after meeting General Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy, Desaix was assigned to the campaign in Egypt. There he continued to prove a valuable asset as a commander in the Battle of Alexandria and Battle of the Pyramids. His victories over Murad Bey the Mamluks earned him the title of "Just Sultan" among the peasants of Egypt until authority was given to his fellow commander Jean-Baptiste Kléber. Desaix would join Bonaparte in Italy once more, where he died in the Battle of Marengo.

Clive is the former leader of Zofia's resistance force - the Deliverance - against the Rigelian Empire and Desaix's coup before relinquishing command to Alm. His name may be derivative of Robert Clive, a British baron and colonial, who became the first British to govern the Bengal Presidency largely credited for the East India Company planting roots in that region of India. More likely, it was a close approximation of Clive's Japanese name.

In Japanese, Clive's name is クレーベ (rōmaji: kurēbe), officially romanized as Clerbe. This seems to be a corruption of the surname of a contemporary to Desaix and Bonaparte, Jean-Baptiste Kléber (JP: ジャン=バティスト・クレベール; rōmaji: jan-batisto kurebēr). Unlike his fellow generals, Kléber was common-born, which withheld his promotion under the French Royal Army. At the outset of the Revolutionary Wars, he reenlisted, where he quickly rose through the ranks, eventually becoming second-in-command. He participated in the campaign in Egypt and Syria. However, when the expedition turned sour for Napoleon, the general withdrew, leaving the remaining French army holding Egypt in the hands of Kléber without a word prior. And it would be in Cairo that he would be assassinated, on the same day that his close friend Louis Desaix would be killed in action. While Kléber was highly regarded by Napoleon for his skill, Emperor-to-be had the commander buried on a remote island, fearing his tomb to be used as a symbol of Republicanism.

While the character of Clive is not of common birth, the reference to Kléber is likely meant to allude to his desire to fight alongside the commonfolk under the banner of the Deliverance. Him being in conflict against the encroaching empire could relate to Napoleon's interpretation of his character as representing Republicanism. Additionally, Clive stepping down from leadership of the Deliverance could be based on Kléber declining supreme command over the French Revolutionary Army.

On the other hand, Louis Desaix's position as "sultan" over Egypt during the bulk of the Egyptian and Syrian expeditions was likely the primary reason for Desaix's name and role in the story, aiding the Rigelian Empire's expansion into Zofia while gaining greater social standing over the region.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soult cautiously inquires after Ney

Just because I love those two and their constant quarrels. From a very long letter some time after the battle of Talavera:

Soult to Jourdan, Placencia, 12 September 1809

[…] Circumstances lead me, Marshal, to ask you a question. Since the 6th Corps left Placencia, the Marshal Duc d'Elchingen has not given me any news of him, and I have received it only from you; you also do me the honor of telling me that the Marshal sends his reports to the King, and that he receives directly the orders of His Majesty. The Emperor having placed the 2nd, 5th and 6th corps of the army under my orders, and not having been informed that this arrangement was recalled, I beg you to tell me if the King has made some changes in it, so that I can justify my responsibility to the Emperor. […]

Uhm… this may be a bit of a weird question but – Ney? Has anything changed or is he still under my command and supposed to write to me? ´coz he kinda seems to ignore me ...

#also: tell joseph to stop meddling with troops under my command#poor jourdan#napoleon's marshals#jean baptiste jourdan#jean de dieu soult#michel ney

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Watch the American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 now: https://youtu.be/bWiW4Rp8vF0?feature=shared

The American Climate Leadership Awards 2024 broadcast recording is now available on ecoAmerica's YouTube channel for viewers to be inspired by active climate leaders. Watch to find out which finalist received the $50,000 grand prize! Hosted by Vanessa Hauc and featuring Bill McKibben and Katharine Hayhoe!

#ACLA24#ACLA24Leaders#youtube#youtube video#climate leaders#climate solutions#climate action#climate and environment#climate#climate change#climate and health#climate blog#climate justice#climate news#weather and climate#environmental news#environment#environmental awareness#environment and health#environmental#environmental issues#environmental justice#environment protection#environmental health#Youtube

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

The napoleonic marshal‘s children

After seeing @josefavomjaaga’s and @northernmariette’s marshal calendar, I wanted to do a similar thing for all the marshal’s children! So I did! I hope you like it. c:

I listed them in more or less chronological order but categorised them in years (especially because we don‘t know all their birthdays).

At the end of this post you are going to find remarks about some of the marshals because not every child is listed! ^^“

To the question about the sources: I mostly googled it and searched their dates in Wikipedia, ahaha. Nevertheless, I also found this website. However, I would be careful with it. We are talking about history and different sources can have different dates.

I am always open for corrections. Just correct me in the comments if you find or know a trustful source which would show that one or some of the dates are incorrect.

At the end of the day it is harmless fun and research. :)

Pre 1790

François Étienne Kellermann (4 August 1770- 2 June 1835)

Marguerite Cécile Kellermann (15 March 1773 - 12 August 1850)

Ernestine Grouchy (1787–1866)

Mélanie Marie Josèphe de Pérignon (1788 - 1858)

Alphonse Grouchy (1789–1864)

Jean-Baptiste Sophie Pierre de Pérignon (1789- 14 January 1807)

Marie Françoise Germaine de Pérignon (1789 - 15 May 1844)

Angélique Catherine Jourdan (1789 or 1791 - 7 March 1879)

1790 - 1791

Marie-Louise Oudinot (1790–1832)

Marie-Anne Masséna (8 July 1790 - 1794)

Charles Oudinot (1791 - 1863)

Aimee-Clementine Grouchy (1791–1826)

Anne-Francoise Moncey (1791–1842)

1792 - 1793

Bon-Louis Moncey (1792–1817)

Victorine Perrin (1792–1822)

Anne-Charlotte Macdonald (1792–1870)

François Henri de Pérignon (23 February 1793 - 19 October 1841)

Jacques Prosper Masséna (25 June 1793 - 13 May 1821)

1794 - 1795

Victoire Thècle Masséna (28 September 1794 - 18 March 1857)

Adele-Elisabeth Macdonald (1794–1822)

Marguerite-Félécité Desprez (1795-1854); adopted by Sérurier

Nicolette Oudinot (1795–1865)

Charles Perrin (1795–15 March 1827)

1796 - 1997

Emilie Oudinot (1796–1805)

Victor Grouchy (1796–1864)

Napoleon-Victor Perrin (24 October 1796 - 2 December 1853)

Jeanne Madeleine Delphine Jourdan (1797-1839)

1799

François Victor Masséna (2 April 1799 - 16 April 1863)

Joseph François Oscar Bernadotte (4 July 1799 – 8 July 1859)

Auguste Oudinot (1799–1835)

Caroline de Pérignon (1799-1819)

Eugene Perrin (1799–1852)

1800

Nina Jourdan (1800-1833)

Caroline Mortier de Trevise (1800–1842)

1801

Achille Charles Louis Napoléon Murat (21 January 1801 - 15 April 1847)

Louis Napoléon Lannes (30 July 1801 – 19 July 1874)

Elise Oudinot (1801–1882)

1802

Marie Letizia Joséphine Annonciade Murat (26 April 1802 - 12 March 1859)

Alfred-Jean Lannes (11 July 1802 – 20 June 1861)

Napoléon Bessière (2 August 1802 - 21 July 1856)

Paul Davout (1802–1803)

Napoléon Soult (1802–1857)

1803

Marie-Agnès Irma de Pérignon (5 April 1803 - 16 December 1849)

Joseph Napoléon Ney (8 May 1803 – 25 July 1857)

Lucien Charles Joseph Napoléon Murat (16 May 1803 - 10 April 1878)

Jean-Ernest Lannes (20 July 1803 – 24 November 1882)

Alexandrine-Aimee Macdonald (1803–1869)

Sophie Malvina Joséphine Mortier de Trévise ( 1803 - ???)

1804

Napoléon Mortier de Trévise (6 August 1804 - 29 December 1869)

Michel Louis Félix Ney (24 August 1804 – 14 July 1854)

Gustave-Olivier Lannes (4 December 1804 – 25 August 1875)

Joséphine Davout (1804–1805)

Hortense Soult (1804–1862)

Octavie de Pérignon (1804-1847)

1805

Louise Julie Caroline Murat (21 March 1805 - 1 December 1889)

Antoinette Joséphine Davout (1805 – 19 August 1821)

Stephanie-Josephine Perrin (1805–1832)

1806

Josephine-Louise Lannes (4 March 1806 – 8 November 1889)

Eugène Michel Ney (12 July 1806 – 25 October 1845)

Edouard Moriter de Trévise (1806–1815)

Léopold de Pérignon (1806-1862)

1807

Adèle Napoleone Davout (June 1807 – 21 January 1885)

Jeanne-Francoise Moncey (1807–1853)

1808: Stephanie Oudinot (1808-1893)

1809: Napoleon Davout (1809–1810)

1810: Napoleon Alexander Berthier (11 September 1810 – 10 February 1887)

1811

Napoleon Louis Davout (6 January 1811 - 13 June 1853)

Louise-Honorine Suchet (1811 – 1885)

Louise Mortier de Trévise (1811–1831)

1812

Edgar Napoléon Henry Ney (12 April 1812 – 4 October 1882)

Caroline-Joséphine Berthier (22 August 1812 – 1905)

Jules Davout (December 1812 - 1813)

1813: Louis-Napoleon Suchet (23 May 1813- 22 July 1867/77)

1814: Eve-Stéphanie Mortier de Trévise (1814–1831)

1815

Marie Anne Berthier (February 1815 - 23 July 1878)

Adelaide Louise Davout (8 July 1815 – 6 October 1892)

Laurent François or Laurent-Camille Saint-Cyr (I found two almost similar names with the same date so) (30 December 1815 – 30 January 1904)

1816: Louise Marie Oudinot (1816 - 1909)

1817

Caroline Oudinot (1817–1896)

Caroline Soult (1817–1817)

1819: Charles-Joseph Oudinot (1819–1858)

1820: Anne-Marie Suchet (1820 - 27 May 1835)

1822: Henri Oudinot ( 3 February 1822 – 29 July 1891)

1824: Louis Marie Macdonald (11 November 1824 - 6 April 1881.)

1830: Noemie Grouchy (1830–1843)

——————

Children without clear birthdays:

Camille Jourdan (died in 1842)

Sophie Jourdan (died in 1820)

Additional remarks:

- Marshal Berthier died 8.5 months before his last daughter‘s birth.

- Marshal Oudinot had 11 children and the age difference between his first and last child is around 32 years.

- The age difference between marshal Grouchy‘s first and last child is around 43 years.

- Marshal Lefebvre had fourteen children (12 sons, 2 daughters) but I couldn‘t find anything kind of reliable about them so they are not listed above. I am aware that two sons of him were listed in the link above. Nevertheless, I was uncertain to name them in my list because I thought that his last living son died in the Russian campaign while the website writes about the possibility of another son dying in 1817.

- Marshal Augerau had no children.

- Marshal Brune had apparently adopted two daughters whose names are unknown.

- Marshal Pérignon: I couldn‘t find anything about his daughters, Justine, Elisabeth and Adèle, except that they died in infancy.

- Marshal Sérurier had no biological children but adopted Marguerite-Félécité Desprez in 1814.

- Marshal Marmont had no children.

- I found out that marshal Saint-Cyr married his first cousin, lol.

- I didn‘t find anything about marshal Poniatowski having children. Apparently, he wasn‘t married either (thank you, @northernmariette for the correction of this fact! c:)

#Marshal‘s children calendar#literally every napoleonic marshal ahaha#napoleonic era#Napoleonic children#I am not putting all the children‘s names into the tags#Thank you no thank you! :)#YES I posted it without double checking every child so don‘t be surprised when I have to correct some stuff 😭#napoleon's marshals#napoleonic

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jourdan's Achievements During the French Revolution (Part 3)

When Jourdan’s name is mentioned, what often comes to mind is his military career and his successes at the Battles of Wattignies and Fleurus. However, he was also active in politics from 1797 to 1799 as a member of the Council of Five Hundred. As much as I would like to examine Wattignies and Fleurus in detail (because I think it is admirable what Jourdan pulled off under pressure from the enemy and from the Convention and Committee), my time is sadly limited, so I will focus on the kind of contributions he on the debating floor rather than the battlefield. I continue to use Fischer’s Jacobin General as my source.

The Politician: Presidency of the Council of Five Hundred; Implementation of Conscription Law

Having been blamed for the defeats of the Armée de Sambre et Meuse so as to become unemployed in 1796, Jourdan headed into politics. He was made president of the electoral college of Haute Vienne and became one of its candidates for election to the Council of Five Hundred, which was created in 1795 and functioned as a legislative body. Jourdan was successfully made a deputy on a vote of 195 to 7. He sat on the left, which comprised of old remnants of the Jacobin party of 1793-1794, and which included his former colleagues from his time in the Armée du Nord and the Sambre et Meuse, as well as future Marshals Augereau and Bernadotte.

Jourdan supported the basic ideas of republicanism with a nationalist emphasis, and indeed first speech in the Five Hundred was anti-clerical (despite or because of the time he spent with his abbot uncle). He supported the coup of 18 Fructidor to oust the conservatives, and in staying loyal to the Republicans and Directory, was elected as president for two terms in total, though the role was largely symbolic (pp. 380-388). He was most active as the head of the military commission of the Five Hundred, “a sub-committee involved with all problems related to the French army”.

[W]e do know of the most important legislation that Jourdan dealt with. He proposed a bill suspending the appointment of any new staff officers or supply officials, the number of which had expanded from 8,000 to 25,000 over the preceding two years, gravely eating into the budget. In the same bill he proposed that the number of officers per staff be fixed at a given level to prevent superfluous aides fro m being promoted. The bill appears to have been passed since there was no further discussion on the subject. He also supported the agitation for a severance bonus for all veterans upon their retirement from the army. … Jourdan asserted that the bonus was not a "degrading salary" like the bounty then paid to volunteers, but a "just reward" for their good services. He further urged that the indigent families of dead or disabled soldiers receive some kind of pension. (pp. 390-391)

The most significant proposal Jourdan would make would be the institutionalisation of conscription, which was sorely needed.

Since the levée en masse in 1793 the government had enactec no legislation to provide the army with recruits nor had they bothered to draft additional men to replace those killed or crippled, or those who had deserted. As a result the army had shrunk from over 1,000,000 men in 1794 to 454,000 in 1796, mostly due to desertion, and declined even more following the Treaty of Luneville in 1797. Most replacements were volunteers induced to enlist for a bounty, and these were few enough. As the diplomatic situation deteriorated in the summer of 1798, the feebleness of the army became a subject of concern. ...

Obviously some form of conscription was necessary, no matter how distasteful this was to many of the Thermidorians. The alternatives were either to reestablish a professional army of paid mercenaries or to resort to the levée en masse in times of national crisis. The first was impossible because it smacked of the recruiting gangs and tyranny of the monarchy; the second was unpopular because it had been a measure of the Terror. Yet the left believed that the Republic dared not attempt to get by with a skeleton army. … Only a powerful army could deter the monarchies of the rest of Europe from attempting to overturn the verdict of 1 794. (pp. 391-393)

To combat this drain of manpower, Jourdan proposed for conscription (technically as a joint proposition between him and his former colleague Debrel).

On July 20, 1798, Jourdan proposed a bill that would draft a contingent of young men into the army on a yearly basis. The justification for the conscription was that all Frenchmen capable of bearing arms were responsible for the defense of their nation. The Revolution had granted them liberty, equality and full citizenship, and it was their duty to serve as soldiers to protect it. Jourdan argued that the alternative was a professional army, and that both the Roman Empire and the French Monarchy had demonstrated the dangers of dividing society into separate military and civilian castes. Should national security be turned over to professionals, not only would the citizens be at the mercy of a contemporary praetorian guard, they also would become prey to effeteness and degeneracy. "The base greed for money will replace the noble passion for glory; self love, love of nation: riches will become more important than virtue; and the Nation, enervated by luxury, will be prey to every ravisher." Like most career soldiers Jourdan considered military service beneficial, a strengthener of character, an instiller of discipline in young men. ...

The provisions of Jourdan's conscription law declared that all able bodied French males between the ages of twenty and twenty-five, except those married before January 12, 1798, were subject to military service. They were to be registered according to their ages in five classes. The legislature would decide at a given time how many conscripts were required, and the Minister of War would then call the necessary number to the colors beginning with the youngest class—those twenty years old. Jourdan argued that the youngest class should be called first because most would have completed their education or apprenticeships, but would not yet be involved with a family or career. Besides men at that age were best suited to bear the physical hardships of war. Each conscript was to serve five years, although chances were that he would not have to serve his fifth year. Each new class of men twenty years old was to replace those having finished their service. The municipal authorities of each arrondisement were to draw up draft lists of their citizens, while the war ministry compiled a master list, coordinated the other details of registration, and handled the actual call-up of the draftees. The conscripts were to be incorporated into veteran units as replacements—the amalgame perpetuated. Although volunteers were still to be accepted, Jourdan urged that the incentive bounty be done away with lest conscripts be tempted to enlist prior to receiving their draft notices in order to collect the bounty; volunteers should enlist out of patriotism, or out of a desire to pursue a military career. All draft evaders were to be treated as deserters, deprived of their civic rights, and subjected to arrest. (pp. 393-395)

The bill was only met with light opposition and made law on 19 September 1798. There were flaws in the law due to the allowance of locally-made decisions (which often neglected national interests) and inefficiencies of war beauracracy, but the loi Jourdan “marked a watershed in military history” (pp. 395-398). As the system was smoothed out, it effectively allowed Napoleon to supply his armies with men. It was a piece of infrastructure that allowed him to maintain the size and scale of his army, and the law’s impacts were felt beyond Napoleon’s fall.

It was the first modern draft law ever enacted; this fact alone explains its many rough edges. Its content and philosophy forshadowed the modern age, for the concept of obligatory military service for a nation's young men, so basic to the mass armies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, was first articulated in the Jourdan law. Indeed, the arguments which he used to defend the bill, that defense of one's country was the duty of every citizen, that a professional army allowed a nation’s manhood to go soft and thus was dangerous to liberty, and that young men were physically and m entally best suited to undergo the rigors of military duty, can be found in any modern brochure defending the men its of conscription. The French theory of the nation in arms originated here. The Jourdan law has remained the basis for French conscription to the present day, and if the law has changed in particulars over the years, the fundamental fact of compulsory military service has remained in effect since 1872. (pp. 398-399)

While Jourdan’s achievements in the French Revolution, political or military, may seem negligible in now, they were not insignificant at the time. As mentioned in the previous two posts, Jourdan understood how to lead under the pressure of and in conjunction with conflicting interests, including that of a civilian government. Men like Jourdan brought time through their victories and the systems they implemented through legislation, however little and inefficient, which helped build the fledgling French Republic and turn it into the working apparatus that would greet Napoleon. If Jourdan is not a first-rate military commander or the ablest Marshal, he had at least the abilities to accomplish what was needed, when it was needed. Considering the era in which he made his mark, those abilities were noteworthy indeed.

Fin.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan (1762-1833) was a French general who held significant commands in the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). He won a major victory for the French Republic at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794 and was among the first 14 men to be appointed marshal of the empire by Napoleon I in 1804.

Continue reading...

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the verdant underbrush of planet Zylar-5, a figure stood silent among the whispering leaves, its appearance an uncanny blend of the native zylathine's ferocity and the artful mimicry of an interstellar traveler. The mask, with its horned visage and intricate patterns, was the work of a legendary artisan named Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, who had traveled the cosmos in search of civilizations where he could trade his skill for their stories.

Jourdan had arrived on Zylar-5 during the Festival of the Silver Moons, a time when the indigenous creatures, the Zylathines, celebrated the alignment of the planet’s two moons. A master of his craft, he sought to honor the Zylathines with a creation inspired by their most revered animal totem, the majestic Iriynx, whose likeness was believed to channel the wisdom of the moons.

With materials gathered from the corners of the galaxy, Jourdan fashioned the mask before you. The horns, curved like the rings of Saturn, were carved from the metallic trees of Ferunia. The fur, as black as the void of space, came from the nebular wolves of Andara. The piercing orange eyes, a pair of sunstones, were mined from the dying stars of the Beltrax cluster.

The mask was not just a ceremonial object but a sophisticated piece of technology. Within its lining, microcircuitry interlaced with bio-fiber optics allowed the wearer to connect with Zylar-5’s neural network of flora and fauna, experiencing the collective consciousness of the planet.

As Jourdan presented the mask to the Zylathines, a hush fell over the crowd. The chief, a wise old Zylathine with scars from celestial battles, donned the mask. In an instant, his perception expanded, the stories of the cosmos flowing into him. He saw through the eyes of the Iriynx, the fierce guardian spirits of the forests, and understood the silent language of the stars above.

The mask became a bridge, not just between species, but between the natural world and the cosmic dance of the universe. Jourdan, a humble artist, had inadvertently created a key to universal understanding.

When the festival ended, Jourdan left as quietly as he had arrived, his spaceship a mere flicker against the moons' glow. The mask, however, remained, a testament to his genius, a beacon of unity on a distant world where stories were not just told, but lived.

And somewhere, in the constellation that bore his name, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's legacy continued to soar, boundless as the universe itself.

0 notes