#bimora

Text

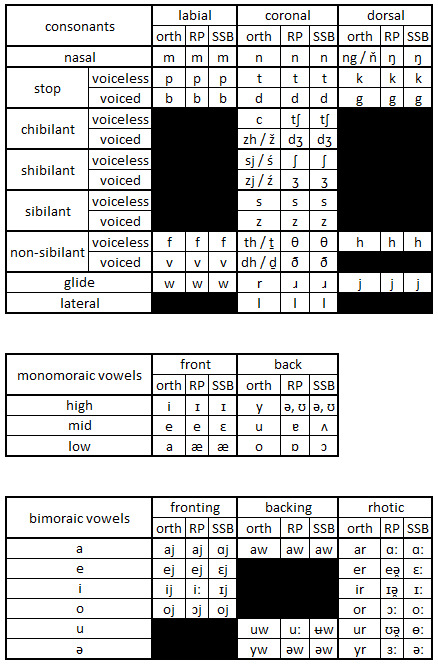

Y Speling Ryform

The following is a spelling reform for English, based on the Standard Southern British I speak myself, as described by Geoff Lindsey.

It is intended to represent the phonemic inventory of this variety unambiguously, using only letters of the basic Latin Alphabet (and in fact does so without using x). There is an alternative using diacritics to represent phonemes otherwise requiring digraphs (other than those where a digraph is actually a better description).

The tables here show the orthography in the first column, the traditional RP transcription in the second, and Geoff Lindsey's SSB transcription in the third.

The transcription of bimoraic vowels (diphthongs and long vowels) naturally suggests linking and intrusive r (likewise y & w, although these are less well-recognised by the general public).

The hapPY vowel is spelt the same as the KIT vowel, as it is genuinely a monophthong, albeit one with the same quality as the start of the FLEECE vowel (the first element of which in this orthography is also <i>).

Obviously this reform would never catch on; it’s way too different to the existent orthography, but it may still be useful for programmatically applying sound changes to Standard Southern British English for a posteriori conlanging.

A sample (the KJV Babel text) is given below. Most words are transcribed according to their strong (stressed) pronunciation, with the exception of articles which are pretty much never pronounced strong in natural speech.

Naw dhy hywl wyrld had won langgwizh and y comyn spic.

Az pijpyl muwvd westwyd, dhej fawnd y plejn in Sjijnar and setyld dher.

Dhej sed ty ijc udhy, "kum, lets mejk briks and bejk dhem thuryli." Dhej juwzd brik insted ov stywn, and tar for mortyr.

And dhej sed, "kum, let us bild arselvz y sitij, and y tawyr huwz top iz in dhy hevynz; let us mejk y nejm for arselvz, lest wij bij skatyd ybrord ywvyr dhy fejs ov dhy hywl yrth."

But dhy Lord kejm dawn ty sij dhy sitij and dhy tawyr wic dhy sunz ov men had bilt

And dhy Lord sed, "indijd dhy pijpyl ar won and dhej orl hav won langgwizh, and dhis iz wot dhej bygin ty duw; naw nuthing dhat dhej prypywz ty duw wil bij widhheld from dhem.

Kum, let Us gyw dawn and dher kynfjuwz dher langgwizh, dhat dhej mej not undystand won ynudhyz spijc."

Syw dhy Lord skatyd dhem ybrord from dher ywvyr dhy fejs ov orl dhy yrth, and dhej sijst bilding dhy sitij.

Dherfor its nejm iz korld Bejbyl, bykuz dher dhy Lord kynfjuwzd dhy langgwizh ov orl dhy yrth; and from dher dhy Lord skatyd dhem ybrord ywvyr dhy fejs ov orl dhy yrth.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

how are we feeling about a tonemic inventory of like. "simple tones" 42 55 ⟨a á⟩ on monomoraic vowels and "complex tones" 253 425 511ˀ 355ʱ ⟨aa aá áa áá⟩ on bimoraic ones (diphthongs and long monophthongs). with the idea that the latter four are combinations of the former two. and then i still don't have much of an intuition for tone sandhi but certainly at least 42 becomes 22 when immediately preceding another 42 (and they alternate for more than two in a row ie /42.42.42.42/ = [22.42.22.42])

#using the high 5 low 1 tone number convention. as opposed to the other one which is the opposite#conlang

0 notes

Photo

こんにちはぁ🤗✨💕 🗓2022.06.17 💖BIMORA HUMAN STEM CELL SERUM for moisturizing @bimora_cosme 💟BimoRaは 一歩先へ導くような存在でありたいと想いから誕生 年齢や性別を超えてどんなに人にも美しい肌から自信につなげてほしいと願っているそうです BimoRa HSC美容液がこだわっている点は 「濃度とコストのバランス」 💟ヒト幹細胞培養エキス ※ ※ヒト脂肪細胞順化培養液 (保湿) 高濃度 30%配合 💟幹細胞には、 こんなチカラが‼️ 🔹再生し、修復する ❣️同じ性質の幹細胞をコピーし、再生修復力を高める 🔹違う細胞になりかわる ❣️自分とは違う細胞になりかわり、トラブルの少ない細胞になる つまり... 🔸細胞を活性化し元気にするチカラ BIMORAが選ぶのは、ヒト由来 ☑️ヒト幹細胞培養液 シワ改善効果や美白効果 抗酸化作用 発毛・増毛効果等 様々な生理的活性効果が学術発表されています 💙年齢とともに遅くなる お肌のサイクル 🔹10~20代 約28日 🔸30代~40代 約40~ 45日 🔹50代以降 約50~ 70日 💟BIMORA HSC美容液で期待できる効果 ・肌のキメを整える ・肌にハリを与える ・乾燥小じわを目立たなくする ・肌荒れを防ぐ など 💚ヒトにやさしい無添加、 フリー 🔸パラベン 🔸合成香料 🔸シリコン 🔸紫外線吸取剤 🔸石油系(界面活性剤) 🔸合成色素 ✿・゚:✲:…✿・゚:✲:…✿・゚:✲:…✿・゚:✲:… 💄コスメコンシェルジュ 💖Kumikoの感想💖 ヒト由来の幹細胞で サラっとした ミルクの様なテクスチャ 保湿力があるので 潤い、ハリ、ツヤ、透明感が期待出来ますね 気になる方は チェックしてみて下さいね🤗✨ @bimora_cosme #bimora #ヒト幹細胞 #美容液 #love #photography #smile #japan #style #me #workout #instagram #instagood #makeup #beautiful #beauty #アラフィフ #アラフォー #アラサー #自撮り #セルフィー #写真 #アンチエイジング #大人女子 #enjoythemoment #world #美活 #美肌 #コスメ #cosmetics #コスメ好きさんと繋がりたい https://www.instagram.com/p/Ce5HAP0pXSV/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#bimora#ヒト幹細胞#美容液#love#photography#smile#japan#style#me#workout#instagram#instagood#makeup#beautiful#beauty#アラフィフ#アラフォー#アラサー#自撮り#セルフィー#写真#アンチエイジング#大人女子#enjoythemoment#world#美活#美肌#コスメ#cosmetics#コスメ好きさんと繋がりたい

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

I think about this kind of structure a lot in the context of Southeast Asian historical linguistics, including Blust’s ‘Austronesian Root Theory’ (*CVCVC = *CV-CVC with a monosyllabic root obligatorily extended with a prefix [when not reduplicated] to form a word)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Linguistic Diversity Challenge Day 4 — Jarawa

linguisten

What is the language called in English and the language itself?

Jarawa, Jarwa, Järawa; which is based on the exonym meaning ‘forigners’ in the neigboring Aka-Bea language

The endonym is aong ‘people’

Where is the language spoken?

Andaman Islands; interior and south central Rutland island, central interior and south interior of South Andaman island, Middle Andaman island, west coast

How many people speak the language?

approximately 270 native speakers; while not entirely uncontacted, their interactions with the outside world are rare and mostly hostile

Which family does it belong to? What are some of its relatives?

Ongan

> Jarawa

A distant relationship of Proto-Ongan and Proto-Austronesian has been postulated (Blevins 2007)

What writing system does the language use?

none

What kind of grammatical features does the language have?

Like many of its closer relatives, the language has rich derivational and inflectional morphology, most notable of which is the productive use of infixes. The language has a “Philippine-type” voice system, called “Focus” system.

What does the language sound like?

Vowels:

i u

e ɘ o

ə

a

Consonants

Among all the 28 consonants, voiced and voiceless plosives are present along with voiceless aspirated plosives. Sounds like nasals, trills, retroflex flap, lateral and retroflex laterals all occur in this language.There are also two approximants in the Jarawa language, these being labial and palatal, along with a few fricatives like the pharyngeal fricative and the bilabial fricative. Two labialised consonants also exist, such as the pharyngeal fricative and voiceless aspirated velar plosive

Jarawa words are at least monosyllabic, and content words are at least bimoraic. Maximal syllables are CVC.

What do you find interesting about the language?

I shared an office with one of the extremely few people who were allowed both by the Indian government and the Jarawa tribe to conduct fieldwork and language documentation work with them. (Pramod Kumar)

I witnessed the discussions between Kumar and Blevins that led to her 2007 paper on a possible genealogical connection of Proto-Ongan and Proto-Austronesian and I find the entire story highly exciting: Basically Kumar just wanted a phonologist’s advice on how to transcribe a few words and how to reconstruct a few things. Blevins, trained in Austronesian linguistics, couldn’t believe her ears when she found one familiar (cognate) word after the other.

Resources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarawa_language_(Andaman_Islands)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember Day 9

Udì [uˈdi] Water

From the Kasshian wanipa with the same meaning. The initial u- only appears in the nominative, in all other cases it’s lost. It survived in the nominative due to a bimoraic minimum for content words. Ordinarily, initial uC- became Cw- early on, but at the relevant stage, this word was uníw in the nominative, with diphthongs counting as single morae, thus, *nwíw would’ve violated the bimoraic minimum. /w/ was regularly lost after coronals, so it resulted in an alternation between un- in the nominative and plain n- in other cases. Nasal consonants before stressed oral vowels became prenasalized stops, thus, /n/ → /ⁿd/, and then later the prenasalization was lost, hence the /d/ in the modern form.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

si'yá /siʔ.já/ prt. an irregular imperative form of 'say' e.g. ł-i-'ulú si'ruh si'yá! (Say "I love you!") ‘isu si'yá, sayuu! (Talk to Isu, Sayuu!) cf. sii (’to say’).

This is the word I made yesterday but did not have time to post! So here it is now. I figured while I was playing around with speech verbs, like with si’ruh from the day before yesterday, I would add an irregular imperative for ‘to say,’ which is something I have wanted to do for a bit.

The regular imperative is formed with an enclitic =‘a (but I might overhaul this soon), and so the logic is sii+’a > si’i+a > si’yá. It’s not uncommon for glottal stops in łaá siri to divide one bimoraic syllable (sii) into two monomoraic syllables (si’i). This is how some agentives are derived!

The first example shows a use with the quotative complementizer from the day before yesterday, si’ruh, and the second example shows a transitive use of ‘say’ meaning ‘speak to.’ So si’yá can cover all the same domains as sii as of now, but I am still deciding whether or not I want there to be a difference between this irregular imperative and the regular imperative. The quickest difference that comes to mind is that the regular imperative, which can co-occur with full verbal morphology, could be used for imperatives directed at people other than the hearer, or with more nuanced TAM morphology.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello! I am here from the baby babble/language acquisition post... How exactly do you find the syllable pattern for a language? I've googled it and I'm having a hard time seeing what the correct answer is.. Like, it keeps giving me multiple patterns for a single language. I'm looking to see what the pattern for Azeri is since it's my fiance's native language so I can compare it to English. I'm not a linguist D: ... Thank you for the time, your blog is great!

Hi! What a great question, thank you so much for asking! I’m about to write a lot because I can’t ever shut up about linguistics, so please bear with me haha.

I’m so sorry that Google gave you confusing answers! The thing is, languages do have multiple syllable patterns. Using English for an example, let’s consider the monosyllabic words cat and go. Cat has three sounds, a consonant, a vowel, and another consonant, so that means its syllable structure is CVC (Consonant Vowel Consonant). Go has only two sounds, a consonant, and a vowel, so its structure is CV. As you can see, both of these are perfectly fine words in English, but their syllable structures differ by one consonant!

So, with that in mind, what we have to do is find the canonical syllable structure of the language. This basically means the longest syllable structure that may be permitted in the language. In English, the canonical syllable structure is often cited as ( C )( C )( C )V( C )( C )( C )( C ), where the sounds in brackets are optional, but may be pronounced in certain words, and the sound outside the brackets are obligatory. All of them would be realized in a word like strengths (s.t.r.e.ng.th.s) (pronounced /stɹɛŋkθs/).

As you can see, English is a very complex language with regards to syllable structure. There can also be moderately complex languages and simple languages. So how do we figure out which one a target language is?

I haven’t studied Azeri, but from the little research I did, I think it has a canonical bimoraic syllable structure. This sounds scary, but all it means is that syllables can have up to two vowels in them. Let’s look at the word aileli (which I hope I’m spelling right). In the first syllable, /ai/, there are two vowels next to each other! (In linguistics, two vowels like this is called a diphthong). Of course, not all words in Azeri need to have two vowels next to each other like that– there are words like pisik and alma that have only one vowel per syllable! All bimoraic structure means is that two vowels are allowed to be there.Now, what about the consonants?

Something interesting about Azeri is that linguists look mostly at the vowels when determining the syllable structure of the language, because it’s based on moras (vowels, basically) instead of syllables (chunks of a word). This means that the canonical syllable pattern doesn’t have much to say about consonants! But I did a little looking. It seems like up to three consonants are allowed to be next to each other in a syllable. Let’s look at the word for happiness, xosbextlik. As I mentioned, I don’t speak Azeri, so my segmentation may be off, but it looks to me like three consonants can be put in a row– xo.sbe.xtlik. And then, of course there can be another consonant that’s not next to those guys! So my best guess for the syllable pattern would be ( C )( C )( C )V( C )( C )( C ). As you can see, that’s quite similar to English!

What does that mean for a baby learning Azeri and English? My best guess is that their babbling would be almost indistinguishable from the babbling of a monolingual English-speaking baby. Since the canonical syllable structure of both languages is very similar, the rhythm would also be fairly similar, and the baby’s babbling, based on the rhythm, would sound the same no matter which target language they were trying to imitate.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember Day 10

Pắ [ˈpʰəː] “Love” (noun)

This is descended from the Kasshian oppa, a derivative of the verb upa “to love”. In Kasshian, it was sometimes inflected as a gender VII noun, poppa, which would’ve become *pupắ [pu̥ˈpʰəː ~ pʰuˈpʰəː]

An interesting quirk of this word is the ergative form ulipà [uliˈpʰʲæ]. The most common allomorph of the ergative is an infix -li- placed before the final consonant of the stem, which in this case is the sole consonant. Historically, the /u/ there is part of the original form. Originally, the infix was a single consonant -l- which would thus be the coda of the preceding syllable, thus ulpà. This is why the /u/ was preserved in the ergative, since *lpà would not be a possible word (both because /lp/ is not a licit onset and because there is a bimoraic word minimum). Later, coda liquids were lost. In the case of /ɻ/, it was simply lost with compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel, while in the case of /l/ an epenthetic /i/ was added. Synchronically, the u- can be thought of as a kind of “supporting vowel”, to keep -li- as an infix. Some speakers do, however, drop the u- making the ergative lipà so that -li- in this case appears as a prefix

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lexember Day 15

Tevà’, pl. tedà’ [tʰɛˈvʲæʔ], [tʰɛˈdæʔ] Storm, a hard rain, especially with high winds

This is derived from a compound of two words, the now-obsolete té [ˈtʰɛː], pl. ôts [ˈot͡s] “storm” and và’, pl dà’ [ˈvʲæʔ], [ˈdæʔ] “rain”.

Té/ôts is descended from Kasshian otta “hurricane, typhoon, etc.”. The meaning had gradually shifted, however, first being generalized to any strong storm, then gradually weakening to just any kind of storm.

Và’/dà’ is descended from Kasshian wadafka “rain”

Modern Shivrashanian has a strict bimoraic word minimum, which both té and va’ satisfy, but also a preference for stems that are at least a full syllable, and té is unusual in that its stem was just the single consonant t-, the -é being a nominative ending (và’ is a full stem, the nominative in this case being no ending). This may be why it was compounded with và’. In this compound form, only the va’ part is inflected. This is usual in compounds, except that sometimes number is marked on the first half

1 note

·

View note