#bioindicator

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Wild Pearls

The golden-striped salamander is one of the species most vulnerable to water contamination, which is why its presence is used as a bioindicator. As vulnerable as it is elusive, this species breeds in caves and rock cracks, where pure water runs out of the rock bed. One single female can lay more that 500 eggs in every reproductive season, lining the walls with living pearls.

Photograph: Javier Lobon-Rovira

The British Ecological Society Annual Capturing Ecology Competition

#javier lobon-rovira#photographer#british ecological society annual capturing ecology competition#golden-striped salamander#salamander#amphibian#bioindicator#nature#animal

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

do u guys understand how fucking tantalizing it is to write fanfiction rn. when i have a 10+ page lab report due in two days i have written one paragraph of

#i want to write So. Bad. BUT NOT ABOUT ALGAE AS BIOINDICATORS#and it’s been so long since I’ve written any fic like it kind of makes me sad#so. all that to say#RAHHHH RAHHHHHH JASON KILLS JOKER AU 100K WORDS RAAAHHHHHHHHH#ahem. anyway.#q dicit

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry Bug-Person here. Your favorite animals are eating my favorite animals🐝🦋🐞🪲🪳🪰🐜🦗🦟🕷️🦂🐛🐛🦋🦋

We’re gonna getcha

21K notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

My bird identification course starts today SO excited

#doing this with my friend and probably one random old man bcs only 3 ppl signed up for the course including us GSDJK#very refreshing to do smth completely different I've been interested in but like with NO pressure to learn or be good at it#we're also learning abt different bird behavior birds as bioindicators in ecology and protection programs HEHEHE

1 note

·

View note

Text

Although dam removals have been happening since 1912, the vast majority have occurred since the mid-2010s, and they have picked up steam since the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which provided funding for such projects. To date, 806 Northeastern dams have come down, with hundreds more in the pipeline. Across the country, 2023 was a watershed year, with a total of 80 dam removals. Says Andrew Fisk, Northeast regional director of the nonprofit American Rivers, “The increasing intensity and frequency of storm events, and the dramatically reduced sizes of our migratory fish populations, are accelerating our efforts.”

Dam removals in the Northeast don’t generate the same media attention as massive takedowns on West Coast rivers, like the Klamath or the Elwha. That’s because most of these structures are comparatively miniscule, built in the 19th century to form ponds and to power grist, textile, paper, saw, and other types of mills as the region developed into an industrial powerhouse.

But as mills became defunct, their dams remained. They may be small to humans, but to the fish that can’t get past them “they’re just as big as a Klamath River dam,” says Maddie Feaster, habitat restoration project manager for the environmental organization Riverkeeper, based in Ossining, New York. From Maryland and Pennsylvania up to Maine, there are 31,213 inventoried dams, more than 4,000 of which sit within the 13,400-square-mile Hudson River watershed alone. For generations they’ve degraded habitat and altered downstream hydrology and sediment flows, creating warm, stagnant, low-oxygen pools that trigger algal blooms and favor invasive species. The dams inhibit fish passage, too, which is why the biologists at the mouth of the Saw Kill transported their glass eels past the first of three Saw Kill dams after counting them...

Jeremy Dietrich, an aquatic ecologist at the New York State Water Resources Institute, monitors dam sites both pre- and post-removal. Environments upstream of an intact dam, he explains, “are dominated by midges, aquatic worms, small crustaceans, organisms you typically might find in a pond.” In 2017 and 2018 assessments of recent Hudson River dam removals, some of which also included riverbank restorations to further enhance habitat for native species, he found improved water quality and more populous communities of beetles, mayflies, and caddisflies, which are “more sensitive to environmental perturbation, and thus used as bioindicators,” he says. “You have this big polarity of ecological conditions, because the barrier has severed the natural connectivity of the system. [After removal], we generally see streams recover to a point where we didn’t even know there was a dam there.”

Pictured: Quassaick Creek flows freely after the removal of the Strooks Felt Dam, Newburgh, New York.

American Rivers estimates that 85 percent of U.S. dams are unnecessary at best and pose risks to public safety at worst, should they collapse and flood downstream communities. The nonprofit has been involved with roughly 1,000 removals across the country, 38 of them since 2018. This effort was boosted by $800 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. But states will likely need to contribute more of their own funding should the Trump administration claw back unspent money, and organizations involved in dam removal are now scrambling to assess the potential impact to their work.

Enthusiasm for such projects is on the upswing among some dam owners — whether states, municipalities, or private landholders. Pennsylvania alone has taken out more than 390 dams since 1912 — 107 of them between 2015 and 2023 — none higher than 16 feet high. “Individual property owners [say] I own a dam, and my insurance company is telling me I have a liability,” says Fisk. Dams in disrepair may release toxic sediments that potentially threaten both human health and wildlife, and low-head dams, over which water flows continuously, churn up recirculating currents that trap and drown 50 people a year in the U.S.

Numerous studies show that dam removals improve aquatic fish passage, water quality, watershed resilience, and habitat for organisms up the food chain, from insects to otters and eagles. But removals aren’t straightforward. Federal grants, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or the Fish and Wildlife Service, favor projects that benefit federally listed species and many river miles. But even the smallest, simplest projects range in cost from $100,000 to $3 million. To qualify for a grant, be it federal or state, an application “has to score well,” says Scott Cuppett, who leads the watershed team at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s Hudson River Estuary Program, which collaborates with nonprofits like Riverkeeper to connect dam owners to technical assistance and money...

All this can be overwhelming for dam owners, which is why stakeholders hope additional research will help loosen up some of the requirements. In 2020, Yellen released a study in which he simulated the removal of the 1,702 dams in the lower Hudson watershed, attempting to determine how much sediment might be released if they came down. He found that “the vast majority of dams don’t really trap much sediment,” he says. That’s good news, since it means sediment released into the Hudson will neither permanently worsen water quality nor build up in places that would smother or otherwise harm underwater vegetation. And it shows that “you would not need to invest a huge amount of time or effort into a [costly] sediment management plan,” Yellen says. It’s “a day’s worth of excavator work to remove some concrete and rock, instead of months of trucking away sand and fill.” ...

On a sunny winter afternoon, Feaster, of Riverkeeper, stands in thick mud beside Quassaick Creek in Newburgh, New York. The Strooks Felt Dam, the first of seven municipally owned dams on the lower reaches of this 18-mile tributary, was demolished with state money in 2020. The second dam, called Holden, is slated to come down in late 2025. Feaster is showing a visitor the third, the Walsh Road Dam, whose removal has yet to be funded. “This was built into a floodplain,” she says, “and when it rains the dam overflows to flood a housing complex just around a bend in the creek.” ...

On the Quassaick, improvements are evident since the Strooks dam came out. American eel and juvenile blue crabs have already moved in. In fact, fish returns can sometimes be observed within minutes of opening a passageway. Says Schmidt, “We’ve had dammed rivers where you’ve been removing the project and when the last piece comes out a fish immediately storms past it.”

There is palpable impatience among environmentalists and dam owners to get even more removals going in the Northeast. To that end, collaborators are working to streamline the process. The Fish and Wildlife Service, for example, has formed an interagency fish passage task force with other federal agencies, including NOAA and FEMA, that have their own interests in dam removals. American Rivers is working with regional partners to develop priority lists of dams whose removals would provide the greatest environmental and safety benefits and open up the most river miles to the most important species. “We’re not going to remove all dams,” [Note: mostly for reasons dealing with invasive species management, etc.] says Schmidt. “But we can be really thoughtful and impactful with the ones that we do choose to remove.”

-via Yale Environment 360, February 4, 2025

#rivers#riparian#united states#north america#northeast#pennsylvania#massachusetts#new york#dam#dam removal#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Coloration and Crypsis in a Pelagic Sea Snake

Harvey B. Lillywhite

Abstract

The Yellow-bellied Sea Snake ranges across the tropical Indo-Pacific and is the most widely distributed squamate reptile. The bicolored form, Hydrophis platurus platurus, has a black dorsum and is cryptic while floating among wavelets that produce dark streaks resembling the snake. When flotsam is present on slicks that are its favored foraging sites, the snakes also resemble sticks or debris, while the mottled coloration of the tail resembles the froth that is a common component of flotsam. A second color morph is the all-yellow xanthic subspecies, H. p. xanthos, which has a discrete population restricted to an inner basin of Golfo Dulce. These yellow snakes are conspicuous, and floating specimens are highly visible. Predation pressures from birds, fishes, and marine mammals are potentially great on this species. Whereas the bicolored snakes are diurnal, the highly conspicuous xanthic snakes tend to be nocturnal. In both forms, brilliant yellow coloration is a presumptive aposematic signal that is reinforced by chemical detection of noxious skin. Scarring of snakes is indicative of predatory strikes, but overall predation appears to be less than expected and conceivably mitigated by crypsis and aposematic signals. Understanding features of coloration is important to the conservation of this species, which may serve as an important bioindicator of changes in climate and habitat.

Read the paper here:

Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 19(1): 1–10 (e338). March 2025

https://amphibian-reptile-conservation.org/manuscript/index.php/arc/article/view/69

358 notes

·

View notes

Text

lichen moments from today's research:

-read that one paper where they measured lichen survival after simulated meteor impact and although the results were essentially like 'the lichens did surprisingly well even though they ARE more likely to die as the impact of the theoretical meteor theyre riding on becomes more powerful, and unfortunately big rocks hitting a planet tend to be powerful, so it might take a time and place with lots and lots of different meteors hitting the planet in question for lichen colonization of another planet to be statistically possible' i was also very distracted by the table where they had the explosives they used on the lichens listed and it was like TNT and C4 and shit loaded on to one end of the lichen destroyer 5000 whos only purpose is to smoosh a lichen between two meteor-like rock disks at different velocities. it just had a very loony tunes subtext to it i enjoyed and i wonder if footage exists

-i knew lichen diversity could be used as a pollution bioindicator but i didn't know that was THAT good of a pollution bioindicator. like there are papers where they're concocting pollution maps of a city by counting the lichen species on similarly-sized trees of the same species and putting the counts into a formula that spits out a lichen yelp review of how much it sucks to breathe air for any given survey site in an area. and the yelp reviews track with rough gradients of air pollution readings. which is wild

901 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pectinereis strickrotti is a recently described nereidid polychaete worm found in the coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean, found at methane seeps off the coast of Costa Rica. Specimens of Pectinereis strickrotti had been observed dating back to 2009 swimming just above the seafloor at ~1,000 m depth but were not successfully captured until 2018.

This species is known for its distinctive, fan-like parapodia, which are used for both locomotion, as swimming, and respiration. This polychaete worm inhabits sandy or muddy substrates, where it burrows and forms a protective tube. Its feeding strategy is largely suspension-based, capturing plankton and organic material from the water column using its elaborately branched tentacles. The species plays an important ecological role by contributing to the sediment's bioturbation, enhancing nutrient cycling in its habitat. As a bioindicator, P. strickrotti's presence and health can reflect changes in the quality of coastal ecosystems, especially regarding pollution levels and environmental disturbances.

Gifs extracted from video: Tulio F. Villalobos-Guerrero,

Reference (Open Access): Villalobos-Guerrero et al., 2024. A remarkable new deep-sea nereidid (Annelida: Nereididae) with gills. PlosONE

#Open Access#science#new species#marine biology#nereididae#annelida#polychaeta#blisster#Pectinereis strickrotti#biology#deep sea#pacific#gif

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

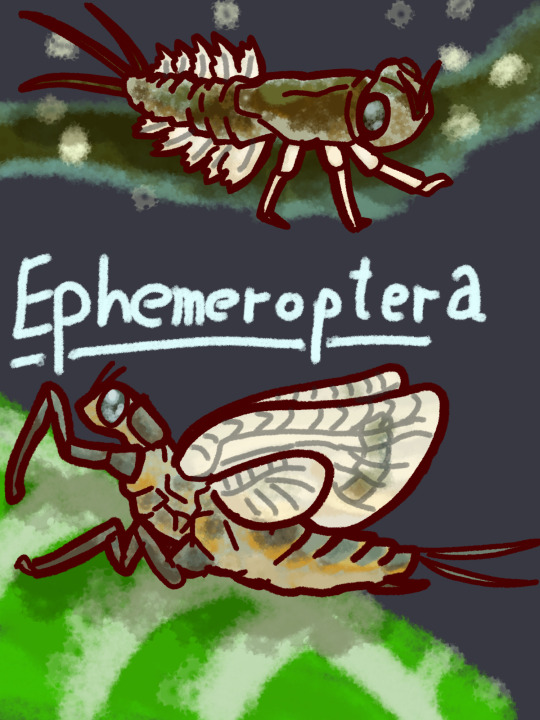

Anatomy practice (1/?): Ephemeroptera

The defining characteristics of this group seem to be 3 pronged tails, two pairs of wings in the adult stage, and two short antenna at the centre of the head.

The larval form lives at the bottom of still water bodies, looking for nutrients. They eat algae, diatoms, and the like. They require clean water to thrive and are a bioindicator of good quality water.

They grow as nymphs through repeated shedding of the whole exoskeleton, until they attain the adult form. This stage is nicknamed the Mayfly as they typically come out in May, but they spend very little time in this form. The adults rarely live longer than a week.

Throughout their life they are a important food source for fish and birds alike.

#art#digital art#medibang paint#coloured art#colored art#Ephemeroptera#Mayfly#Mayflies#invertebrates#Bugs#Bugs on tumblr#Bugblr#entomology#Entomologist#Insects#Insectblr#Bug art#[Cores Crib Sheet]

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Philip Sontag first visited Antarctica as a Ph.D. student, he brought back an unusual souvenir: a huge bag of penguin feathers. And now, after a decade-long analysis, Sontag and his colleagues have figured out how to use such feathers to create a living map of the mercury contamination that increasingly threatens Southern Hemisphere wildlife.

Mercury is a common by-product of gold mining, a growing industry in several southern countries. The toxic metal accumulates as it moves up the food chain by binding with amino acids in animals and then infiltrating their central nervous systems, where it can inhibit neural growth. Tracking mercury exposure is crucial for monitoring an ecosystem—but merely sampling rocks, ice or soil for its presence tells little about how much is actually entering the food web.

Many predators, including penguins, have evolved ways to dispose of mercury. The chemical builds up in feathers that the birds regularly molt in large quantities. Sontag, now a polar researcher based at Rutgers University, and his colleagues hoped to use molted feathers to determine where penguins picked up the toxic substance. The scientists were surprised to find a very clear correlation between the feathers’ levels of mercury and of a carbon isotope called carbon-13; the latter varies based on geographic location and thus acts as an indicator of “where the penguins are feeding or where their breeding grounds are,” Sontag says. These findings, published in Science of the Total Environment, confirmed this connection in seven penguin species scattered across the Southern Ocean—a pattern suggesting they’re exposed to more mercury farther north, where the comparatively warmer environment leads to higher carbon-13 levels.

These findings suggest that penguins could function as mercury bioindicators: living trackers of environmental pollutants, says the study’s senior author John Reinfelder, a marine biologist at Rutgers. Rather than measuring the chemical itself in a snapshot of time and place, he says, measuring penguin feathers’ mercury levels tracks the substance’s movement through the oceanic food web. For instance, penguin species known to reside near one another had varying mercury and carbon-13 levels because of their different migration and feeding patterns. These data could be modeled into a maplike database to help guide future projects on conservation and polar science research.

Scientists consider penguins promising candidates for such bioindicators, says marine scientist Míriam Gimeno Castells, a Ph.D. student at the Institute of Marine Science from the Spanish National Research Council, who was not involved in the study. The animals are midway through the food chain. They breed in colonies, so researchers can easily scoop up feathers from many different individuals. Additionally, every breeding season they undergo dramatic molts; the feathers they lose “will contain the mercury that has accumulated during the nonbreeding season,” Gimeno Castells says.

Sontag’s next steps are to collect newer feathers to experiment with, across different species, and to measure mercury in penguins’ blood and prey to compare with levels of the substance in their feathers.

And how are the penguins themselves doing with their current mercury levels? “We don’t believe penguins have been exposed to toxic levels as of yet,” Reinfelder says. “Yes, the penguins will be okay.”

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

HELLO O HEHEHE could i ask for some skipp x reader for these trying times... i'll love quite literally anything you write.. HAVE A NICE DAY!!!

"Sunlight on the Surface" - Ramshackle

Skipp x Reader

Romantic

Mostly Headcanons

---

YAHOO SKIPP MERMAID SIREN STUFF

These are trying times for sure yeah I gotchu man

Stupid title but I based it off of like skipps hair?? And like imagine it under water ykyk?? Like orange and stuff bye this is stupid

---

Pretend you're some kind of deep-sea diver or explorer or nerd or whatever and Skipp is just a mermaid/siren guy chilling way down below thankz

Skipp, like just about every single marine creature, sticks to the ocean floors rather than the shoreline—mainly due to the fact mermaids can't breathe out of water for long. He can, however, find fun in basking in the rare sunlight for a few moments every now and then. Sirens don't typically have a good rep— he can understand that— but he'd rather avoid being pelted with rocks and coarse sand. He's sure that if they just heard a little tune from his mandolin they'd change their minds.

Most gentle soul ever physically and like emotionally?? If that's the word

He spends his days strumming his mandolin and entertaining the local marine life, scrounging around the sandy bottoms and between the long, winding seaweed, and sticking by Stone's side whenever he allows him. He has an almost endless ocean to explore, but he likes to stick by Ramshackle's harbor. That's where he gets to see Vinnie every now and then, and he practically grew up in the murky waters below the dock pilings. He's friends with practically everyone (even the animals and even Stone), and is more than happy to make more.

You're not crazy about Ramshackle's paranormal or mystical creatures—you don't go out searching for unicorns or Santa. Rather, neat shells and small specimens, keystone species, bioindicators, lots of nerdy things of the like.

So, running into a real-life siren certainly takes you by surprise. As in, it makes you choke on water and stupidly flail about in a fearful, panicked frenzy, which effectively gains the creature's attention. You only flail about more when it swims over and even grabs hold of you. That's when you pass out from both fear and lack of oxygen.

When you wake up, you're back on land (kind of) again, all your items returned to your side. You're rested on a massive, mossy rock that pokes up through the ocean waves. It's not too far from shore, at least. It doesn't take long for you to put two and two together: the evil siren could've taken your things and discarded your floundering form for shark food, but it didn't. They didn't, rather.

When Skipp hesitantly pokes his head out of the water moments later, you refrain from freaking out. That's good, he's glad. He approaches you with his usual, friendly demeanor, toned down just a bit so you don't get scared and fall off the rock you're perched on. He's "normal", for a siren, you can tell. He even offers to go find you some food, but you'd much rather be on your way.

So, he offers to help you reach the shore. He doesn't think you should be swimming on your own in such a winded state. It takes about another half hour or so to gradually gain an ounce of your trust before you let him help you. He probably has you drape one arm over his shoulders to hold yourself up and does most of the work from there.

I blacked out and started writing where am I going with this

You make it back safely, to your surprise, and all in one piece. He acts like it's no big deal and wishes you "the very best" before dipping back down into the water and swimming away. Your interaction was mostly panic-filled (on your end), but overall pleasant and painfully brief. But, for your own safety, you settle on avoiding deeper waters for a bit.

The next day you're back at it again despite your prior declaration. Maybe it's just because you're filled with morbid curiosity and desperate to know more, or maybe you just want some mermaid guy to save you again idk

Regardless, you inevitably bump into each other. You kind of just float around the surface and wait for him to approach you since you lack lungs like his. He'll pop his head out of the water, give you a warm greeting, and ask how you're doing. Probably says you should go home and rest instead of poke around underwater, but he's a little surprised when you admit something along the lines of wanting to know more about sirens, specifically him. You clearly think he's weird and out of the ordinary, but he can look past that. Curiosity is natural, after all. So he bites and explains that, no, he does not eat humans. Or any meat of any kind.

Tiny tidbit I wrote when I was gonna do a oneshot heeheehahahhol

---

You lean back against the sandy dunes, legs outstretched in the water before you.

"Really? You don't eat humans? Seriously? That can't be right. You're so gonna drown me and eat me, huh." You're mostly joking. Skipp laughs and waves you off.

"Oh, no of course not! I'm vegetarian."

"...what?"

"Huh. Never heard of a vegetarian siren. And you like it? Is that, like, a common thing, or...? You don't ever feel weak, or sick, or...I don't know, wrong?" you gradually lose your voice, silently pondering if you're being too invasive, or even insensitive. "Sorry. I could've worded that better."

"Vegetarian! I don't eat fish. Or humans, for that matter. So you've got nothing to worry about!" He flashes you a toothy, reassuring smile as he mindlessly strums his mandolin, upper body rested against a heavy rock submerged in the mellow waves.

"Nah, it's fine. I don't really feel weak or sick or wrong. I feel just...normal, I guess! I recommend. Fish are friends, not food." He gives you a big dorky smile as he takes a moment to duck underwater before poking his head through the sloshing waves once more, shaking his head this way and that to shake off some of the excess water from his hair. "What do you eat?"

You only shrug in response. "All kinds of things, I guess. Fish included. Sorry."

He feins a dramatic heartbroken expression clutching whenever his heart would be and sputtering in shock. "What?! Cruelty!" He breaks out into a fit of giggles after.

You laugh along as you share more of your favorite foods and the ones commonly sold along the streets in Ramshackle. Skipp seems entertained. He wades through the waters with ease, occasionally dipping under for a brief moment before returning like nothing ever happened, and seems to hold a permanent, toothy grin. You like that about him.

Tgat was kinda stupid I just wanted to include it Ook abyways

---

You're quick to become friends, or at least friendly acquaintances, but something remotely close to romance takes quite a while to develop (naturally), being two different yet still fairly similar species and all. Also, I feel like Skipp wouldn't want you thinking he's hasty to earn your trust so that he can bite your face off, regardless of how many times he's reassured you he's a very friendly vegetarian, so he's happy with gradually growing closer over extended periods of time. Not like he has ulterior motives or anything anyway idk

(I'm gonna basically restate whatever I wrote in my other one involving mermaid skipp, so plsss bear (bare? bear) with me 😞)

Big fan of serenading you with his mandolin skills and charming voice. He dares to creep closer to land, or even hang around the docks, all so that he can hang around your presence for a little while. He also probably offers on more than one occasion to teach you. It's difficult to do in water but he swears up and down he can make it work (and he absolutely will).

Loves exchanging information and fun facts with you, since you both live in areas that vastly contrast the other's. He's always eager to learn more about your daily life (you in general), and is more than happy to share his experiences in the ocean and its weird, native creatures with you. He has a way of delivering morbid or creepy facts with ease that manages to draw laughter regardless of how odd they may be.

He's so giving without expecting a single thing in return. Frequently comes bearing gifts and trinkets, things you've never seen before. Doesn't really anticipate a gift in return (although an apple or two would be nice), but such a gesture does mean a lot to him and is treated as such (come back to this word better). He keeps it tucked away or frequently adorns it if it's a wearable item, and absolutely sheds tears if it gets lost, stolen, or broken at any point. He's pretty sentimental and holds you and everything you bring to high regards.

Because he's almost always stuck in the water, you typically come to him rather than him coming to you (aka land), and it's a small tiny detail and really not a big deal, but it doesn't go unnoticed by Skipp and he's actually insanely grateful to have a reoccurring visitor (you) that's willing to trek to deep waters just to say good morning. He makes it obvious, too. Skipp has no issue with spewing sentimental, genuine, sometimes sappy speeches about how much he values you and your efforts and your humor and your face and all that. He's kind of cheesy about it, too.

Very resourceful and can probably make jewelry and fun designs out of things like seaweed, seagrass, and even litter, so bracelets and funny looking necklaces crafted from shreds of plastic and seagrass are common gifts.

Such a gentle and respectful soul. He honors and appreciates the marine life and just about every living creature on Earth, which obviously includes you. He's never pushy or coercive, despite being a siren and being particularly good at it. The ocean can be scary at times, especially when mermaids and sirens are added to the mix of already strange local life, but he puts on a big show of being protective and strong for your sake.

If you wanna hug you have to dive into the ocean and figure it out there. Maybe you can share a fire kiss like Mabel's and Mermando's 🔥🔥

Yeah like this

---

A/N: NI HAO FINE SHYTS

I keep changing my name sorry

Hii hope this works cuz once again im NOT proofreading allat goodnight

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I see mosses, I think about how they function similarly to sensors or organic bioindicators. For example, you can potentially determine when an environment is contending with pollution merely by looking at moss from a distance. But moss can also be collected and thoroughly examined in a laboratory.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moss, often overlooked, plays a crucial ecological role. Acting as nature’s sponge, it absorbs and retains moisture, controlling soil erosion and stabilizing ecosystems. Mosses filter pollutants from water, improving quality and supporting biodiversity. They provide habitats for tiny organisms, essential food sources in complex food webs. Furthermore, moss contributes significantly to nutrient cycling, breaking down rocks and organic matter into fertile soil. Beyond ecology, mosses serve as bioindicators, their sensitivity reflecting environmental health. Their resilience and adaptability inspire biomimicry in architecture, showcasing potential for sustainable design. Ultimately, moss embodies the delicate balance and quiet strength underpinning Earth’s ecological harmony.

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

god i'm such a slut for sentences like "their prominence as bioindicators and keystone species emphasizes the need to understand their systematics and evolution"

9 notes

·

View notes