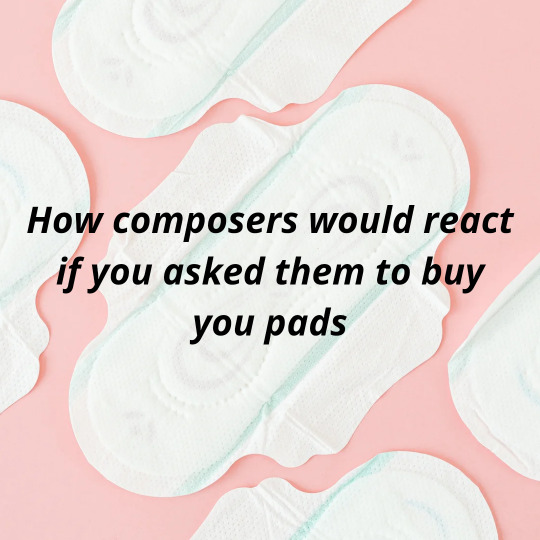

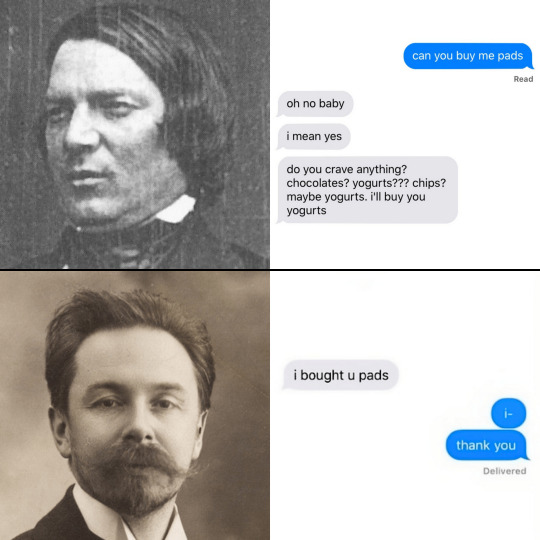

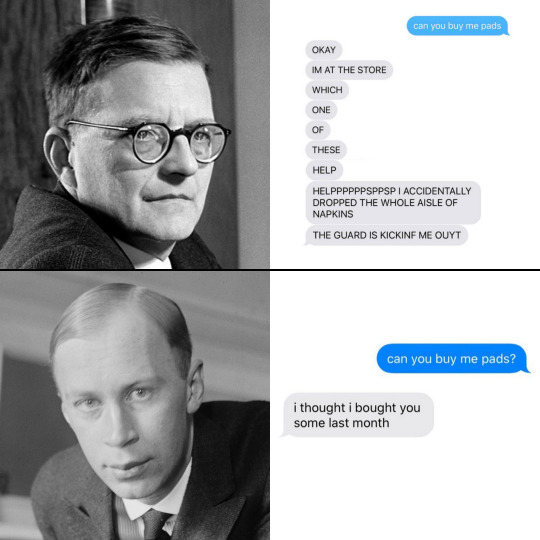

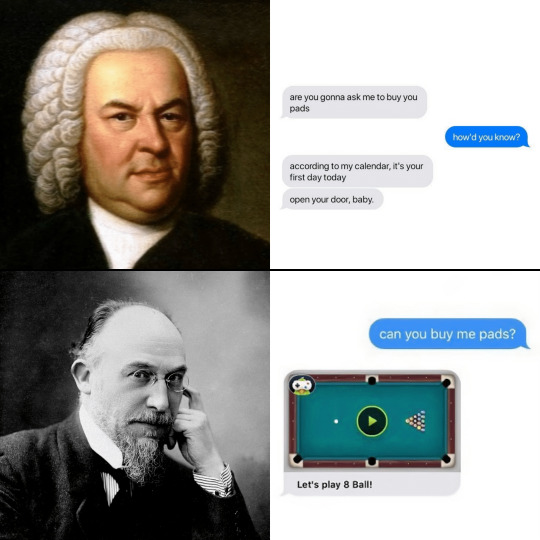

#boulez

Text

#berlioz#liszt#haydn#mahler#schumann#scriabin#rachmaninoff#mussorgsky#mozart#messiaen#ravel#chopin#bach#satie#boulez#beethoven#shostakovich#prokofiev#classical music#classical#classical composers#composers#classical music memes#can you buy me pads#memes

635 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Il faut avoir vis-à-vis de l'oeuvre que l'on écoute, que l'on interprète ou que l'on compose, un respect profond devant l'existence même. Comme si c'était une question de vie ou de mort.

- Pierre Boulez

#boulez#pierre boulez#quote#music#composer#conductor#sound#listening#arts#french#culture#classical music

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Top 5 20th Century Classical Books that I use

CLICK SUBSCRIBE!

My Top 5 20th Century Classical Books that I use for music composition

Please watch video above for detailed info:

Hi Guys,

As requested [from my polytonality video/blog], here are the main [Top 5] books that I use for 20 Century [or 21st Century] classical composing:

Before we start None of these books has guitar Tablature or anything like that they are all standard musical…

View On WordPress

#20 century classical#Anthology of Twentieth Century Music#books#boulez#classical#composition#Messiaen#messiaen-technique-my-musical-language#music#music lessons boulez#Robert.P.Morgan#textbooks#The musical language of Pierre Boulez#top 5#Twentieth Century Harmony -Vincent Persichetti

0 notes

Photo

“𝑺𝒆𝒎𝒑𝒓𝒆 𝒑𝒊ù 𝒑𝒆𝒏𝒔𝒐 𝒄𝒉𝒆 𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒄𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒓𝒆 𝒊𝒏 𝒎𝒐𝒅𝒐 𝒆𝒇𝒇𝒊𝒄𝒂𝒄𝒆 𝒃𝒊𝒔𝒐𝒈𝒏𝒂 𝒄𝒐𝒏𝒔𝒊𝒅𝒆𝒓𝒂𝒓𝒆 𝒊𝒍 𝒅𝒆𝒍𝒊𝒓𝒊𝒐 𝒆 𝒐𝒓𝒈𝒂𝒏𝒊𝒛𝒛𝒂𝒓𝒍𝒐"

𝐋𝐀 𝐌𝐔𝐒𝐈𝐂𝐀 𝐂𝐎𝐌𝐄 𝐏𝐑𝐀𝐓𝐈𝐂𝐀 𝐃𝐄𝐋𝐋'𝐈𝐌𝐏𝐎𝐒𝐒𝐈𝐁𝐈𝐋𝐄 - Monografie oltre ai generi𝗣𝗶𝗲𝗿𝗿𝗲 𝗕𝗼𝘂𝗹𝗲𝘇: 𝗹'𝗶𝗻𝗾𝘂𝗶𝗲𝘁𝗼 𝗲 𝗶𝗹 𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗼𝗿𝗲

🎧 𝐀𝐒𝐂𝐎𝐋𝐓𝐀 𝐈𝐋 𝐏𝐎𝐃𝐂𝐀𝐒𝐓

Nelle precedenti puntate del programma, abbiamo più volte narrato del grande movimento d’avanguardia musicale europeo, concentratosi in particolare a Darmstadt, durante agli anni ’50 del secolo scorso, il punto di partenza in azione e reazione di tutto quello che andrà a seguire nel Novecento. Lo abbiamo visto attraverso le monografie su Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono, György Ligeti, Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen e in dialettica opposta o complementare anche John Cage e Giacinto Scelsi. Come un'ideale chiusura del cerchio, andiamo oggi alla scoperta di uno dei più carismatici, per certi tratti autoritari e sicuramente influenti personaggi di quegli anni, il compositore e direttore d’orchestra francese Pierre Boulez.

In gioventù Boulez si ritirò dagli studi matematici per intraprendere quelli musicali anche se i primi influenzeranno particolarmente il suo approccio alla composizione. Con il trasferimento a Parigi avviò una vera e propria rivoluzione musicale insieme a Stockhausen appunto e al belga Henri Pousseur, accentuata dall’incontro con il giovane John Cage durante gli anni Sessanta. Proprio nella capitale francese fondò nel 1970 l’IRCAM, l’istituto per l’esplorazione e lo sviluppo della musica moderna.

Compositore innovativo e aperto alla sperimentazione di quegli anni, Pierre Boulez fu anche un’eccezionale direttore d’orchestra, a capo dell’orchestra di Cleveland, la sinfonica della BBC e la Filarmonica di New York in cui contribuì alla diffusione del repertorio di Debussy, Mahler e Stravinsky.

Michele Selva ci porta a conoscere una figura imprescindibile della cosiddetta classica contemporanea, nonché uno dei precursori ella musica elettronica e delle su infinite possibilità.

Un programma a cura di Michele Selva

Regia di Alessandro Renzi

Illustrazione tratta da un’immagine di Artcurial

🎧 𝐀𝐒𝐂𝐎𝐋𝐓𝐀 𝐈𝐋 𝐏𝐎𝐃𝐂𝐀𝐒𝐓

🎶 𝐒𝐂𝐎𝐏𝐑𝐈 𝐈𝐋 𝐂𝐀𝐍𝐀𝐋𝐄 - La Musica come Pratica dell'Impossibile

0 notes

Photo

BOULEZ CONDUCTS ZAPPA

“The perfect Stranger”, originally issued on vinyl in 1984

1 note

·

View note

Text

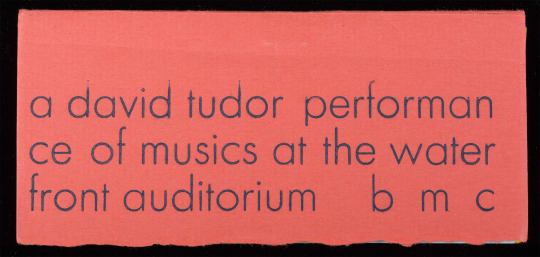

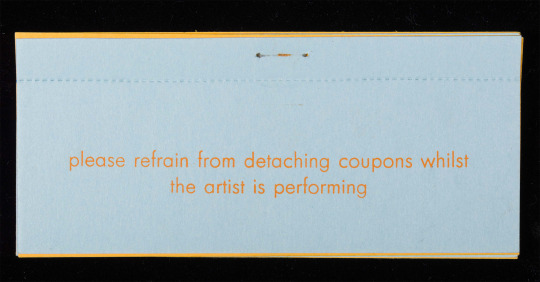

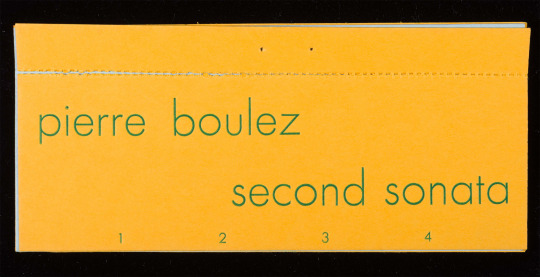

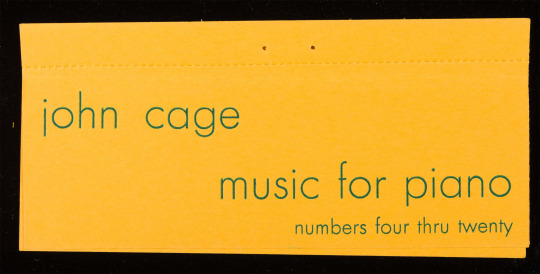

A David Tudor Performance of Musics at the Water Front Auditorium, Black Mountain College, Black Mountain College Print Shop (Tommy Jackson, printer), Black Mountain, N.C., 1953 [Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina]

[State Agency Records, N. C. Museum of Art, Black Mountain College Research Project, Series VI, Box 76, folder 30, 1953, Summer. Original program. A David Tudor Performance of Musics at the Water Front Auditorium]

«1953, Summer. Original program. A David Tudor Performance of Musics at the Water Front Auditorium. Included Second Sonata by Pierre Boulez, Displaced Spaces, part two by Stefan Wolpe, Music for Piano, numbers four thru [sic] twenty by John Cage, Perspectives by Earle Brown.»

#graphic design#typography#art#music#performance#program#school#david tudor#pierre boulez#stefan wolpe#john cage#earle brown#tommy jackson#black mountain college print shop#western regional archives#state archives of north carolina#1950s

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gustav Mahler allegedly advised to spend less time studying counterpoint and to read more Dostoevsky. In Mahler as in novels, happiness comes best at the edge of catastrophe

‘how a musical idea, seemingly exhausted, rekindles itself through the unexpected emergence of one of its facets suddenly revealed, how a main phrase becomes secondary under the intrusion of a counterpoint that consciously takes precedence, how this perpetual change of hierarchy occurs…’

Video: Gustav Mahler, Ninth Symphony (adagio). Leonard Bernstein

Adorno: “During a walk with Schönberg and his students, Gustav Mahler allegedly advised the latter to spend less time studying counterpoint and to read more Dostoevsky. If Mahler’s music recalls great novels, it’s not just because it often seems to tell a story. The very curve it describes is novelistic: the way it rises to exceptional situations and collapses. It performs gestures comparable to that of Natasha, the heroine of 'The Idiot,’ burning banknotes, or to Jacques Collin, the convict disguised as a Spanish priest who, in Balzac, prevents young Lucien de Rubempré from suicide and elevates him to temporary splendor. In Mahler as in novels, happiness comes best at the edge of catastrophe. (…) The attitude of those who lament Mahler’s lengthiness is no better than that of promoters of abridged versions of Fielding, Balzac, or Dostoevsky. The generous temporal extension of Mahler’s music… makes no concessions to the comfort of easy listening, which spares the listener from any memory and expectation. His music embraces duration. Mahler makes those who have outlived him shudder like a boat journey makes frequent flyers shudder. Mahlerian duration reminds them that they themselves have lost duration. (…) The epic symphony savors time, surrenders to it; it seeks to materialize measurable time in living duration. It sees in duration itself the image of meaning, perhaps in reaction to the disgrace that duration begins to suffer in the mode of production of advanced industrialism and in corresponding forms of consciousness.

Music must cease to deceive the listener about time through a true 'auditory illusion’; time must not pretend to be the moment it is not. Schubert’s celestial lengths were already the antithesis of such an attitude.” (Translated from French. Theodor W. Adorno: Mahler, A Musical Physiognomy)

Pierre Boulez: “Adorno is right about the novelistic structure in Mahler, but he doesn’t delve deep into the analysis. His reflection doesn’t rely on the description of the form, whereas there is so much to say about the form in Mahler, especially in all the finales, which are truly the pages of the highest complexity ever written in music. It would have been fascinating, for example, to show how a musical idea, seemingly exhausted, rekindles itself through the unexpected emergence of one of its facets suddenly revealed, how a main phrase becomes secondary under the intrusion of a counterpoint that consciously takes precedence, how this perpetual change of hierarchy occurs… For instance, consider the adagio of the Ninth, a kind of extraordinary extension of Tristan’s gruppetto: it is truly the Liebestod magnified, amplified by polyphony, and something Wagner would never have dared to dream.” (Translated from French. October 26, 1988, Questions to Pierre Boulez, by Henry-Louis de La Grange, MUSICAL, Châtelet Review - Paris Musical Theater: Mahler and France)

youtube

Video: Isolde’s Liebestod “Mild und leise” - Richard Wagner, Waltraud Meier, 1995

'consider the adagio of the Ninth (Gustav Mahler), a kind of extraordinary extension of Tristan’s gruppetto: it is truly the Liebestod magnified, amplified by polyphony, and something Wagner would never have dared to dream'

#of great art#classical music#art#music#artist#gustav mahler#dostoevsky#singer#richard wagner#dostoyevsky#dostoyevski#songwriting#opera#wagner#mahler#fyodor dostoevsky#storyteller#musician#waltraud meier#pierre boulez#novel#story#Youtube

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peefeeyatko, a 1991 documentary. W/ Xenakis, Boulez, and Stockhausen (not pictured)

6 notes

·

View notes

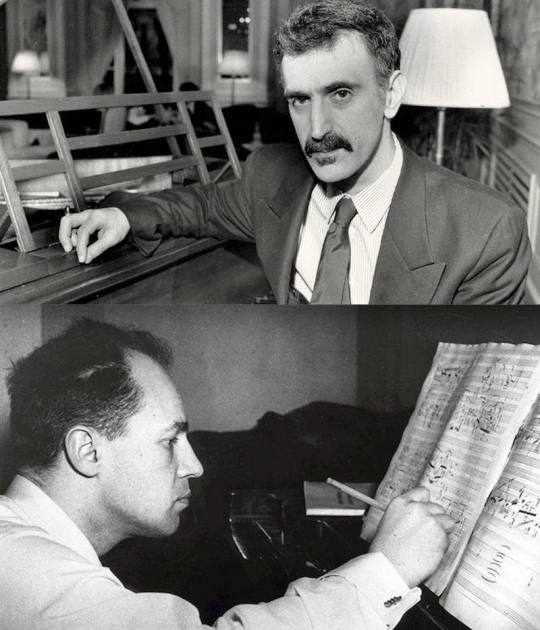

Photo

I believe a civilisation that conserves is one that will decay because it is afraid of going forward and attributes more importance to memory than the future. The strongest civilisations are those without memory - those capable of complete forgetfulness. They are strong enough to destroy because they know they can replace what is destroyed. Today our musical civilisation is not strong; it shows clear signs of withering… […] Conducting has forced me to absorb a great deal of history, so much so, in fact, that history seems more than ever to me a great burden. In my opinion we must get rid of it once and for all.

- Pierre Boulez (in 1975...he changed his mind in the 1990s)

Frenchman Pierre Boulez was classical music’s most celebrated maverick, widely regarded as the 20th century’s greatest innovator of classical music. Boulez’s 1967 proclamation that the answer to the stagnation of opera was to “blow the opera houses up”, is just one of many bold and candid statements that have won him recognition as one of classical music’s most outspoken and controversial figures.

But he has also said: “I don’t want my statements to be frozen in time. A date should always be attached to them. Certainly if you take a picture of yourself 30 years ago, that same picture cannot be used as a picture of yourself today.” His incendiary comments, whether directed at his contemporaries (he has described Duchamp as ‘a pompous bore’, Cage as ‘a performing monkey’, and Stockhausen, ‘a hippie’), or more general topics such as culture and history, however, suggest that he enjoyed the controversy.

It was Boulez who once declared, without a trace of irony, that any composer who did not acknowledge the necessity of Schoenberg’s 12-tone system was “useless”, and who wrote caustic articles such as “Schoenberg Is Dead”, criticising the Austrian composer’s approach just months after his death in 1951.

I find much to disagree with Boulez especially about his remarks on wiping out civilisations and defacing all past art, including da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

But other times I agree 100% such as when he said, “In the provincial town of Paris the museum is very badly looked after. The Paris Opera is full of dust and crap, to put it plainly. The tourists still go there because you ‘have to have seen’ the Paris Opera. It’s on the itinerary, just like the Folies-Bergere or the Invalides, where Napoleon’s tomb is. […] These operatic tourists make me vomit. If I write a work for the stage I certainly won’t write it for star-fanciers; I shall be thinking of a public that has an extensive knowledge of the theatre.”

Or his views on minimalist music, “If you want a kind of supermarket aesthetic, OK, do that, nobody will be against it, but everybody will eventually forget it because each generation will create its own supermarket music - like produce that after eight days is rotten and you can’t eat it anymore and have to toss it away.”

Many young composers of his generation in the 1960s and since read his writings, but they didn’t always know his music. And yet what you might not guess from the polemics is the sheer beauty of his compositions.

Messiaen, who taught Boulez, would say of him that, underneath it all, he was simply a poet. Messiaen also believed it would take a long time for the wider public to really understand Boulez’s music, because it has a very particular and original sensibility. Messiaen would talk with pride of his former student, describing him as a formidable and immense talent, though when young “he was like a flayed lion”. Boulez was indeed a very angry young man.

He attacked anything in sight, including those who had taught him, such as René Leibowitz, a Schoenberg disciple who was largely responsible for introducing serialism to Paris. At one point, Boulez even turned against Messiaen, who had done so much to encourage and help him, and it was five years before their relationship was restored.

Boulez grew up in Nazi-occupied France. He was 20 when the Second wWorld War ended. The continent had to make itself anew. Messiaen used to describe travelling home on the Metro with Boulez after classes. Boulez would say “Who’s going to put music right? It’s in such a terrible state.”

And Messiaen would reply: “You.”

He considered himself from his earliest days to have an almost Napoleonic mission regarding music and its cultural role. His ambition was not only to compose, but to change the attitude of the public, institutions in France and - later - the wider western world with regard to modernism. He initially pursued this aim with a heightened form of ideological dogmatism. The works of the Second Viennese School, and composers such as Bartók and Varèse, were not played at all in Paris in the late 40s; that they are now part of the international concert repertoire is in large part due to Boulez.

As a conductor, his approach to the early modernist masterpieces has had a tremendous impact on the way they are considered by younger conductors and heard by audiences. He made stupendous recordings of hundreds of pieces of music – among them works by his illustrious contemporaries Carter, Ligeti, Kurtág, Stockhausen, Berio and Birtwistle - and has inspired and helped generations of younger composers.

Through the power of his personality, the scale of his reputation and his considerable personal charm, Boulez has made big things happen, way beyond the confines of manuscript paper. Paris’s new concert hall, the Philharmonie de Paris, owes its existence to him, as does the rest of the Cité de la Musique, his own group the Ensemble Intercontemporain and IRCAM, the musical research institution attached to the Pompidou Centre.

In his own music, however, he moved away from Serialism, the great rallying cry of his youth, and over the years further distanced himself from the concept, now viewing it with scepticism. For me, his best compositions are not the ones from his early years but the works in which the foundations of his earlier idiom are treated much more freely and with greater fantasy. I believe that only when he accepted he was fundamentally a French composer did he find his true voice.

Le Marteau sans maître (1953-57) was a breakthrough. It is a work in which you can also hear the profound influence of extra-European music, above all from Asia and Africa. This radically alters the sonority and the music’s sense of time and direction, as well as its expressive viewpoint and ethos. Boulez was by no means the first French composer to be open to, and ravished by, eastern music – it had already had a transformative effect on the father of modern music, Debussy, and on succeeding generations – but he took it a stage further, and the curious marriage between his already transforming serial universe and the extra‑European world produced a unique style.

For me, his quasi-symphonic portrait of Pli selon pli, portrait de Mallarmé – completed in the early 60s – is a greater masterpiece, and the decades that followed produced gem after gem: Eclat/Multiples, Cummings Ist der Dichter, explosante-fixe, Sur Incises. There is no better postwar musical piece written for orchestra than Notations, his five hyper-elaborate orchestral canvases, all based on very simple serial pieces he wrote for the piano in his early 20s.

Arguably the most important composer-conductor since Mahler, Boulez knows the orchestra more intimately than any of his colleagues, and these short, dazzling showpieces have an intoxicating exuberance and elegance.

Boulez only published around 30 works in his lifetime. When he died at 90 years old in 2015, I’m sure he regretted that he hadn’t written more. But I suspect he has not had the easiest of relationships with his muse. This is a man with a vastly refined and critical mind. His intelligence is so questioning and extreme, and his aural imagination so sensitive and acute, that composing must have been a taxing experience. The world today doesn’t need huge numbers of pieces, as it did in, say, Haydn’s time. What are needed, surely, are essential statements, singular and unique works. And these he has provided, without question by the time the curtain came down on his life.

Having cultivated the image of the angry young man of new music in the post-war years, it took a long time in public perception for the austere, uncompromising radical to morph into the hugely respected and revered figure Boulez became in the last decades of his life. As he mellowed further over the following decades, he also began to conduct music by a number of composers he would surely have dismissed out of hand in his hardline early years. That inevitably required some quiet revisionism.

I have an enormous regard for his rendition of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen. It’s a surprising landmark in every sense. Boulez’s performance of Patrice Chéreau’s centenary production of the Ring Cycle shocked and then seduced audiences at Bayreuth. Filmed in 1980, it’s still among the most searingly insightful readings of the cycle, musically and dramatically, ever performed. Another of the highlights of Boulez’s operatic career, this 1992 performance of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande in Peter Stein’s production at Welsh National Opera revealed the expressivity, focus, and clarity that Boulez brought to everything he conducted.

Like everything he conducted, though, it was the precision and lucidity of his performances that were so revealing, and which illuminated a range of 20th-century music in a way that few conductors before him had ever approached. And while a good handful of Boulez’s own works – the second and third piano sonatas, Le Marteau Sans Maître, Pli Selon Pli, Eclat/Multiples, Sur Incises, the orchestral Notations - will surely endure, it is his achievement as a conductor and educator in moving the music of our time and of the immediate past into the mainstream of our concert life that is likely to be his lasting, crucially important memorial.

His skills as a conductor are vast - he would have been every bit as intellectual and important if he was just a conductor and had never written a note of music himself. As it is, his music, thoughts, theories and treatises are all a massively important part of 20th and 21st century music.

#boulez#pierre boulez#quote#music#composer#french#sound#conductor#orchestra#france#serialism#paris opera#icon#essay

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

J'écoute marcher dans mes jambes

La mer morte vagues par-dessus tête

Enfant la jetée-promenade sauvage

Homme l'illusion imitée

Des yeux purs dans les bois

Cherchent en pleurant la tête habitable

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Arnold Schoenberg, Pierrot Lunaire, op. 21 (21. «O alter Duft»).

Pierre Boulez, director

Yvonne Minton, mezzosoprano

(Los tres primeros compases de la partitura son citados en Malina de Ingeborg Bachmann.)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

FIVE CONTEMPORARY COMPOSERS

GIACINTO SCELSI, GYÖRGY LIGETI, PIERRE BOULEZ,

KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN, ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

conceptual graphics

See full project -> https://jackiebranc.site/five-contemporary-composers/

#elloon#jackie branc photographer#graphic design#computer graphics#pierre boulez#györgy ligeti#Giacinto Scelsi#Karlheinz Stockhausen#arnold schoenberg#conceptual#conceptural art

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think itd be really funny to attempt to analyze one of pierre boulez's works in tonal terms purely for shits and giggles

2 notes

·

View notes