#bridewell prison

Link

It is this idea of reanimating the archive, and the Black lives Habib locates within it, that inspires the work of the poet Caroline Randall Williams, which I have been teaching and writing about. Williams’ Lucy Negro, Redux, published in 2019 with the subtitle: The Bard, a Book, and a Ballet, tells the story of Shakespeare’s Sonnets from the point of view of a figure from the archives who has been called “Lucy Negro”, and whom some have seen as a possible model for the so-called “Dark Lady” to whom the later part of the sequence seems to be addressed.

“In August of 2012, I got it into my head that Shakespeare had a black lover,” Williams writes, “and that this woman was the subject of sonnets 127 to 154.” Lucy Negro, Redux intersperses Williams’ poems about Lucy with a prose account telling the story of her meeting with English professor Duncan Salkeld and, consequently, with the figure of “Black Luce” in the archives of Bridewell prison. Interweaving archival narrative with original poems Williams recovers and reclaims an overlooked Black life from the English archive in ways that resonate with Habib’s own critical and creative project.

#Imtiaz Habib#black lives#in the english archive#shakespeare#william shakespeare#black luce#poetry#poet#Caroline Randall Williams#Lucy Negro Redux#bridewell prison#early modern#history#many headed monster

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'll weave your dreams in canvas of stars

A sanctuary in your mind, safe from nightmares

If you nestle your stray hope in my dark heart

and make it its forever haven

#ratonhnhaké:ton#connor ac3#connor kenway#assassin's creed 3#ac3#ac edit#acedits#my ac3 edit#ac3 edit#assassin's creed 3 edit#ACIII#Assassin's Creed III#assassin's creed#my words#my writing#poems on tumblr#poem of the day#poems for him#poetsontumblr#mywords#love notes#free verse#mywriting#bridewellprison#prisoner outfit#bridewell prisoner outfit

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eliza Prince, widow of John at Berkshire house of correction, remarked rather pointedly to the authorities that she could continue in the family tradition of keeping the jail or she could fall on the parish which would then have to support her and her eight children, as well as pay the wages of a new jailer.

That your petitioner's and his father and grandfather have been keepers of the house of correction at Abingdon dkr a great many years, and your petitioner has a brother and a brother in law very well qualified and willing to assist her in the future management of that prison, and she can find sufficient security, if required, for her faithful discharge of the office of Bridewell keeper. Your petitioner therefore humbly prays to be continued in the office of keeper of the house of correction, that she may be thereby able to provide bread for her family, which must otherwise be unavoidably thrown on the parish for maintenance.

"Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History" - Philippa Gregory

#book quotes#normal women#philippa gregory#nonfiction#eliza prince#widow#john prince#berkshire#prison#corrections#family traditions#jail#parish#abingdon#bridewell#employment

1 note

·

View note

Text

Assassin’s Creed Real Life Locations Map (Maps) (Real Filming Locations)

Map by @warrenwoodhouse. A set of fanmade maps featuring all of the Real Life Locations from the entire @assassinscreed franchise.

Map 1: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?hl=en&mid=1yyWU7jFW3L7DVjDgZlFuHDTrtCY

Map 2: coming soon

Map: Isu Sites: I’ll add the link here soon

Changelog

8th April 2024 at 11:17 am: Added multiple locations to the section titled “Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood” in the map

7th April 2024 at 1:45 pm: Added “Bridewell Prison” to the section titled “Assassin’s Creed III” in the map. Added “Hope Jensen’s Warehouse” to the section titled “Assassin’s Creed: Rogue” in the map

15th February 2024 at 3:26 pm: Added the section titled “Assassin’s Creed: Mirage” to the map and added Baghdad to that section as well

12th February 2024 at 8:16 am: Updated map description and moved post to my Tumblr blog

11th June 2020 at 4:54 pm: Created map

#warrenwoodhouse#gaming#maps#google maps#googlemaps#google mymaps#googlemymaps#.map#realfilminglocations#real filming locations#.gmap#assassinscreed#assassin's creed#assassins creed#real life#assassin’s creed real life map#assassins creed real life map#assassinscreedreallifemap#2020#2024#maps-assassinscreed#maps assassinscreed#assassinscreed-maps#assassinscreed maps

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

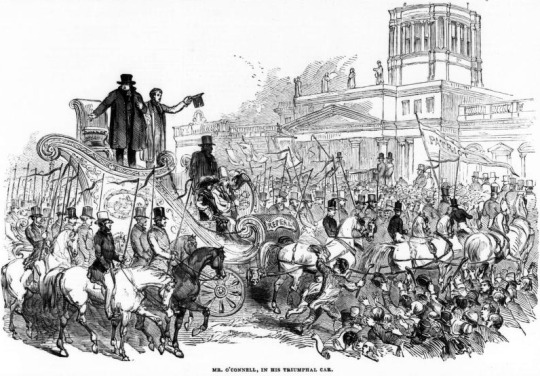

Francis Crozier and O'Connell's chariot

In early September of 1844, Francis Crozier was between jobs, having gotten a year's leave from the Admiralty, and was just beginning to plan his upcoming trip to France and Italy. In the meantime, however, he was spending some time in Dublin with his family.

This meant he was in just the right place at the right time (or, as he may have felt, the wrong place at the wrong time) to experience a historic event: the parading of Repeal politician and statesman Daniel O'Connell through the streets of Dublin on a huge gilded chariot.

(Illustrations taken from the Illustrated London News.)

The ‘chariot’, 3 metres high and 4.5 metres long, was specially made for O’Connell’s glorious re-entry into the city, and modelled on the triumphal cars of ancient Rome. It was upholstered in purple silk and blue wool and adorned with gilded mouldings and decorative overlays, depicting shamrocks and stylised classical foliage. The sides showed Hibernia with the increasingly familiar national iconography of harp, round tower and wolfhound. On the back was a representation in gold of a harp surmounted by the word ‘Repeal’, summarising O’Connell’s campaign for repeal of the Act of Union. (x)

In May of that year, O'Connell and his son had been found guilty on conspiracy charges and sentenced to a year in prison. They'd appealed the verdict to the House of Lords, and their appeal was granted on September 4th, 1844. They were released after serving three months in Richmond Bridewell penitentiary.

On Saturday, September 7th, O'Connell was paraded through the streets of Dublin on his gilded throne-chariot, drawn by six "splendid grey horses" and surrounded by "a crowd of around 200,000 citizens." Several guilds were also represented in the long parade, as well as town council and corporation members and the Lord Mayor. Their route took them from the penitentiary (now the Griffith Barracks Multi-Denominational School) to O'Connell's home on Merrion Square.

If the Crozier house, which was located at 2, Sandford Place, was near where we find Sandford Parish Church today, this was a bit of a walk away. But the crowd clearly made itself felt throughout the city, because on Monday, September 9th, Francis Crozier wrote to James Clark Ross:

What think you the decision of the house of Lords, it has been & is considered here a great victory for Dan – Such a set of Ruffians as were perading [sic] about here on Saturday they say that they Dans people may now do anything as he can get them clear –

I did not see one drunk man nor one that looked the least like a gentleman although I suppose he has many adherents that are so by both

Whether Crozier happened to catch sight of O'Connell and the triumphal procession itself isn't clear, but as he gives no description of the spectacle, he may not have. Accounts in the Illustrated London News bear the latter assertion out: "It is a fact worthy of notice, that there was not, in the immense assemblage, a single individual intoxicated; each guild was followed by a temperance band […]," and though excitement continued through the evening, "everything passed off with the utmost quiet."

Leinster (which includes Dublin) was a stronghold for O'Connell and the Repeal movement, but the movement had met resistance in the predominantly Protestant, largely Presbyterian, Ulster. For his own part, though he had publicly stressed common cause and appreciation for Protestant Repealers, O'Connell had privately expressed disdain for the Presbyterian support for the United Irishmen, and for Protestantism in Ireland itself.

Crozier, an Ulsterman and a Protestant, was evidently not very impressed with "Dan" O'Connell and his followers, nor with the handling of the House of Lords:

I must confess that I think the house of Lords have signed their own death warrant as a house of appeal by leaving the case in the hands of a few mountebank political Lords.

A quotation of unclear origin that's often attributed to Sophia Cracroft states that Francis Crozier was an "indifferent speller" and a "horrid radical". If she did say (or write) that, it's difficult to know what sort of radicalism she had in mind.

At the time of Francis' and his siblings' baptisms in the late 18th century, the Crozier family belonged to the Banbridge First Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church—but had, as one of "only four or five" Presbyterian families in town, taken the minority position of not supporting the United Irishmen. Later, Francis' brother Graham became a vicar in the Church of Ireland. Overall, the Croziers come off as fairly solidly establishment. And while we don't know much about Francis Crozier's politics and he may have espoused views Sophia Cracroft would find radical, we do know that he was—unsurprisingly, given his origins—not a Repealer.

Sources:

MSS 284/364/17: Letter from Francis Crozier to James Clark Ross September 9th 1844 (SPRI)

The Illustrated London News, September 14th 1844, pp. 164-6

The Croziers of Banbridge by Olga Kimmins on The Thousandth Part

O'Connell's Chariot on A History of Ireland in 100 Objects (by An Post, The Irish Times, the National Museum of Ireland, and the Royal Irish Academy)

Icebound in the Arctic (2nd edition 2021) by Michael Smith

Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 (1989) by R. F. Foster

Griffith Barracks (Wikipedia)

#francis crozier#m#be gentle if i said something stupid; this is not my field; i just thought it was a really cool coincidence#19th century#daniel o'connell

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

[The] distinction between the legal code and the unwritten popular code is a commonplace at any time. But rarely have the two codes been more sharply distinguished from each other than in the second half of the 18th century. One may even see these years as ones in which the class war is fought out in terms of Tyburn, the hulks and the Bridewells on the one hand; and crime, riot, and mob action on the other. […] The commercial expansion, the enclosure movement, the early years of the Industrial Revolution—all took place within the shadow of the gallows. The white slaves left our shores for the American plantations and later for Van Diemen's Land, while Bristol and Liverpool were enriched with the profits of black slavery; and slave-owners from West Indian plantations grafted their wealth to ancient pedigrees at the marriage-market in Bath. It is not a pleasant picture. In the lower depths, police officers and gaolers grazed on the pastures of crime—blood-money, garnish money, and sales of alcohol to their victims. The system of graduated rewards for thief-takers incited them to magnify the offence of the accused. The poor lost their rights in the land and were tempted to crime by their poverty and by the inadequate measures of prevention; the small tradesman or master was tempted to forgery or illicit transactions by fear of the debtor's prison. Where no crime could be proved, the J.P.s had wide powers to consign the vagabond or sturdy rogue or unmarried mother to the Bridewell (or “House of Correction”)—those evil, disease-ridden places, managed by corrupt officers, whose conditions shocked John Howard more than the worst prisons. The greatest offence against property was to have none.

The law was hated, but it was also despised. Only the most hardened criminal was held in as much popular odium as the informer who brought men to the gallows. And the resistance movement to the laws of the propertied took not only the form of individualistic criminal acts, but also that of piecemeal and sporadic insurrectionary actions where numbers gave some immunity. When Wyvill warned Major Cartwright of the “wild work” of the “lawless and furious rabble” he was not raising imaginary objections. The British people were noted throughout Europe for their turbulence, and the people of London astonished foreign visitors by their lack of deference. The 18th and early 19th century are punctuated by riot, occasioned by bread prices, turnpikes and tolls, excise, “rescue”, strikes, new machinery, enclosures, press-gangs and a score of other grievances. Direct action on particular grievances merges on one hand into the great political risings of the “mob”—the Wilkes agitation of the 1760s and 1770s, the Gordon Riots (1780), the mobbing of the King in the London streets (1795 and 1820), the Bristol Riots (1831) and the Birmingham Bull Ring riots (1839). On the other hand it merges with organised forms of sustained illegal action or quasi-insurrection-Luddism (1811–13), the East Anglian Riots (1816), the “Last Labourer's Revolt” (1830), the Rebecca Riots (1839 and 1842) and the Plug Riots (1842).

E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (Vintage, 1966), pp. 60–2.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Daniel Lambert (1770-1809)

attributed to Benjamin Marshall (1768-1835)

about 1800

Oil on Canvas

This is one of many portraits that were painted of the celebrity Daniel Lambert (1770-1809), famous in the late Georgian era as the self-styled ‘fattest man in Britain’.

Leicester-born Lambert was the eldest son of the Earl of Stamford’s huntsman, and as a youth was a keen sportsman. Having served an apprenticeship at a die-casting works in Birmingham, he returned to Leicester to succeed his father as Keeper of the Bridewell Prison, a sedentary job which caused his weight to balloon uncontrollably. By the age of 23 he weighed 32 stone (203 kg), and after the gaol closed in 1805 – at which point Lambert weighed 50 stone (318 kg) – he became a virtual recluse.

However, poverty forced Lambert to put himself on exhibition to raise money. Visiting London in 1806, he took lodgings in Piccadilly and received paying visitors between 12 noon and 5pm. After this success, he combined successful tours of the regions with a new career as a dog breeder in Leicester. He died suddenly in Stamford aged only 39 and weighing 52 stone (330 kg). Even though he was provided with a wheeled coffin, it took 20 men to drag his casket into the grave.

Compton Verney

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bridewell - Megan Johnson

Script :

The Bridewell is a historical-landmark pub situated in The Ropewalks area of Liverpool.

The Pub has an incredibly rich History, As the building was originally host to a police and fire station- Housing around 100 prisoners at a time with 7 Cells that have now been converted to Lavish booths to enjoy the craft beers created by the owners themselves.

The Prison itself opened in the mid 19th century and has been host to plenty of unique characters, One in particular was the legendary author Charles Dickens who in 1860 was sworn in as a special constable for 1 night in order to research for his book ‘The Uncommercial Traveler’

The building ceased to be used as a prison in 1932, but was brought back to life in World War 2 by the US Military.

After the short occupation, The pub seemed to be derelict for afterwords until the 1980s wherein the pub was rejuvenated and transformed into a music rehearsal space for local musicians and artists.

Although the Pub does not feature much in the way of Traditional Art mediums, It’s unique history and eccentric architecture more than makes up for it and solidifies The Bridewell as a Landmark Liverpudlian Pub.

Source:

Blog Post:

After meeting with the group and discussing what would be the best way to structure our video, we decided to assign each member a specific pub in order to add a more structured and sectioned feel to the video- I was assigned The Bridewell Pub. I felt a connection to this particular pub due to its interesting concept and history to it and after doing some digging and research I discovered plenty of unique facts and stories about the pub. I then collected the facts and stories I had found and created a script to use in the recording process which I found to help me stay on topic during the recording. I was originally planning on interviewing a friends relative who had stayed in The Bridewell in his youth, However he had unfortunately passed away a few weeks prior to us beginning to conduct our research.

I then recorded my section and sent it of to Jain to add to the video.

0 notes

Text

Saint of the day August 28

St. Edmund Arrowsmith, 1628 A.D. St. Edmund Arrowsmith (1585 - 1628) Edmund was the son of Robert Arrowsmith, a farmer, and was born at Haydock, England. He was baptized Brian, but always used his Confirmation name of Edmund. The family was constantly harrassed for its adherence to Catholicism, and in 1605 Edmund left England and went to Douai to study for the priesthood. He was ordained in 1612 and sent on the English mission the following year. He ministered to the Catholics of Lancashire without incident until about 1622, when he was arrested and questioned by the Protestant bishop of Chester. He was released when King James ordered all arrested priests be freed, joined the Jesuits in 1624, and in 1628 was arrested when betrayed by a young man he had censored for an incestuous marriage. He was convicted of being a Catholic priest, sentenced to death, and hanged, drawn, and quartered at Lancaster on August 28th. He was canonized as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

Blesseds John Roche and Margaret Ward. John Roche was one of the London martyrs of 1588. Blessed Margaret Ward was a gentle woman born at Congleton in Cheshire, in the service of another gentle woman, Whitall, in London. She had visited in the Bridewell prison, Mr. Richard Watson, a secular priest; to him she smuggled a rope, but in making use of it to escape, Watson had fallen and broken an arm and a leg. He was gotten away by Margaret's young Irish serving-man, John Roche, who, to assist the priest's escape, changed clothes with him and so, was himself arrested. When charged, both Blessed Margaret and Blessed John refused to disclose Mr. Watson's whereabouts. They were offered their liberty if they would ask the Queen's pardon and promise to go to church; to which they replied that they had done nothing that could reasonably offend her Majesty, and that it was against their conscience to attend a protestant church. So they were condemned. These martyrs, who suffered with such firm constancy and patience, were forbidden to speak to the people from the scaffold because their persecutors were afraid of the impression they would make; "but the very death of so many saint-like innocent men (whose lives were unimpeachable), and of several young gentlemen, which they endured with so much joy, strongly pleaded for the cause for which they died."

Bl. William Dean, 1588 A.D. Martyr of England. Born at Linton in Craven, Yorkshire, he was originally a minister who was converted to Catholicism. William left England and received ordination at Reims, France, in 1581. Returning to England, he was arrested and exiled but returned and was arrested again in London. William was executed in Nile End Green, London. He was beatified in 1929.

Bl. William Guntei, 1588A.D. Martyr of Wales. A native of Raglan, Gwent, Wales, he was a Catholic who received ordination at Reims, France, in 1587. He returned to England to work for the Catholic mission. Captured, he was hanged at Shoreditch and beatified in 1929.

Bl. Thomas Felton, 1588 A.D. English martyr. The son of Blessed John Felton, he was born at Bermondsey, England, in 1568. Leaving England to study at Reims, France, he entered the Friars Minim and went home to England to recover from an illness. He was arrested and imprisoned for two years. Released, he was again put in prison and hanged at lsleworth, London.

Bl. Thomas Holford, 1588 A.D. English martyr. Also known as Thomas Acton, he was born at Aston, in Cheshire, England. Raised a Protestant, he worked as a schoolmaster in Herefordshire until converting to the Catholic faith. He left England and was ordained at Reims in 1583. Going home, he labored in the areas around Cheshire and London until his arrest. He was hanged at Clerkenwell in London.

Bl. Hugh More, 1588 A.D. Martyr of England. He was a native of Lincolnshire, educated at Oxford. After converting while at Reims, Hugh was martyred at Lincoln’s Inn Fields by hanging. Pope Pius XI beatified him in 1929.

Bl. Robert Morton, Roman Catholic Priest and English Martyr. He was executed at Lincoln's Inn Fields, London. Feastday Aug.28

Bl. Teresa Bracco, In WW II an enraged soldier throttled her until she choked. He shot her twice with his revolver and to vent his rage, crushed part of her skull with his boot. Teresa had fulfilled her intention: "I would rather be killed than give in".Aug. 28

Bl. Laurentia Herasymiv, was a nun who joined the Sisters of Saint Joseph in 1933 and was Martyred Under Communist Regimes in Eastern Bloc.Aug. 28

Bl. Aurelio da Vinalesa, Aurelio was a member of the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. Martyred during the Second Spanish Republic.Aug. 28

ST. AUGUSTINE, BISHOP OF HYPPO AND DOCTOR OF THE CHURCH, St. Augustine of Hippo, Bishop and Doctor of the Church, was an indefatigable truth-seeker. The author of hundreds of books, tracts, treatises and letters. He was born in Thagaste on November 13, AD 354, and died in the city of Hippo (present-day Annaba in Algeria), on August 28, AD 430.

https://www.vaticannews.va/en/saints/08/28/st---augustine--bishop-of-hyppo-and-doctor-of-the-church.html

0 notes

Text

A Dialogue of Self and Soul: Plain Jane's Progress- Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar

The following is my selective retyping of this essay found in the back of the Norton Critical edition of Jane Eyre.

Jane Eyre is a novel looking at the female realities around her: confinement, orphanhood, starvation, and rage even to madness. Jane becomes the emblem of a passionate, barely disguised rebelliousness. Victorian critics understood this and disliked the "anti-Christian" refusal to accept the forms, customs, and standards of society. Jane refuses to submit to her social destiny, of which Elizabeth Rigby said: it pleased God to make her an orphan, friendless, and penniless. What horrified the Victorians was Jane's anger.

The story is of enclosure and escape. Everywoman in patriarchal society must meet and overcome oppression, starvation, madness, coldness. Jane's confrontation with Bertha is an encounter with her own hunger, rebellion, and rage.

Jane is on a pilgrim's progress towards maturity, and there are problems she has to solve on the way to maturity. At Gateshead, the book opens with the remark that there was no possibility of taking a walk that day. Jane is excluded from the family, so she sits in the window behind the curtain. This is emblematic of the choice- stay behind the oppressive curtain, or go out into the cold loveless world.

John Reed comes on the scene though and it results in his fat lip and Jane's sentence to the red room.

As Jane meditates on the injustice, she is faced with the option of escape through flight or escape through starvation, which will recur in the novel. But Jane finds a third possible escape: madness, through seeing ghosts. This opens up a larger drama that we find throughout the book. Jane's anomalous, orphaned position in society, her enclosure in stultifying roles and houses, and her attempts to escape through flight, starvation, and... madness.

It is her eagerness for a new servitude that brings Jane to Thornfield, where she will confront the demon of rage that has haunted her since her afternoon in the red room. Before the appearance of Rochester, she explores Thornfield. It is the house of Jane's life. There is a long, cold gallery, where portraits of unknown ancestors hang the way the specter of Mr Reed hovered in the red room. Mrs Fairfax is assumed to be her employer when in fact she is just the housekeeper, the surrogate of an absent master, as Mrs Reed was for Mr Reed. But the third floor holds enigmatic locked rooms guarding secrets. In the attic, Jane looks out over the world and articulates her desire for liberty.

Many of Jane's problems can be traced to her status as governess at Thornfield. Governesses were, and were not, members of the family, were, and were not, servants. The women at Thornfield represent negative role-models. The most important are Adele, Blanche, and Grace Poole. While Adele isn't yet a woman, she is a little woman; cunning and doll-like. She longs for fashionable gowns rather than love or freedom, as her mother would. Where Miss Temple's was the way of the lady, and Helen's was the way of the saint, Adele and Celine's are the way of vanity fair.

Blanche is also a denizen of vanity fair, but Blanche teaches Jane that conventional marriage can be a prison, through the charade of Bridewell. But the charade also suggests that the marriage market is a game even scheming women are doomed to lose.

Finally there is Grace, who, acting as an agent for men, may be the keeper of other women, but both are prisoners in the same chains.

Jane's meeting with Rochester is a fairy-tale, but his first action is to fall on the ice. He acknowledges her power, and though they begin as master/servant in one sense, in another they are spiritual equals. In time Jane falls in love with him because she feels them equals.

After his long revelation of his past love life, Jane is shown to be his equal, and in fact he notices her unseduceable independence in a world of self-marketing Celines and Blanches.

Jane, in a moment of despair upon hearing about Blanche, asserts that though she is poor, obscure, plain, and little, she has as much soul and heart as he does.

Rochester then casts away his own disguise and professes that Jane is his equal.

The Victorians were upset because the novel here is asserting that Jane is his democratic equal.

But there were impediments. Rochester, despite some attempts to cast off the masks or disguises that give him mastery, still does need to cast it off, because the inequality exists.

Once Rochester has secured Jane's love, he almost immediately begins to treat her as an inferior. She senses this and resolves to keep him in check. His ultimate secret is of course Bertha, the literal impediment to his wedding. After the aborted ceremony, Jane learns that he had married her for status, sex, money, everything but love and equality. He regrets it, but Jane says she would have spurned such a union.

Jane's impediments are other. While she loves Rochester the man, she has doubts about Rochester the husband. She tells him that after 6 months the excitement of her love would dwindle. Jane's life pilgrimage has prepared her to be angry at Rochester's, and society's, concept of marriage. As her fears and anger about marriage intensify, she is drawn back into her own past to re-experience the sense of doubleness that had begun in the red room. The first sign of this is the recurring dream of a child. The child represents Jane's own childhood, her being orphaned. Until she reaches maturity, independence, and true equality with Rochester, she can't let go of the orphaned alter-ego so easily, despite love-making, silk dresses, jewelry and a new name. Another sign of this doubleness is Jane's reflection in the mirror on her wedding day where she says she seems the image of a stranger.

Finally, in the appearance of Bertha, the most threatening avatar, Jane sees the Bertha does what Jane wants to do: Jane secretly wants to tear the garments up, Bertha does it. Jane would like to put off the wedding day, Bertha does it. Resenting the mastery of Rochester, she wishes to be his equal in size and strength, Bertha is nearly that. Bertha, in other words, is Jane's truest and darkest double- the angry aspect of the orphan child, the ferocious secret self that Jane has been trying to repress ever since Gateshead- these two characters represent the socially acceptable, conventional personality and the free, uninhibited, and sometimes criminal self.

Jane's desire to destroy Thornfield, the symbol of Rochester's mastery and her own servitude, will be carried out by Bertha.

Some writers have noted that Bertha is the symbol of what happens to a woman who tries to be the fleshly version of the masculine élan. Just as Jane's instinct for self-preservation saves her from earlier temptations, it must save her from becoming this woman by curbing her imagination at the limits of what is bearable for a powerless woman in the England of the 1840's. While Bertha acts out Jane's secret fantasies, she at least provides her a lesson of what not to do.

But Bertha also acts like Jane in ways. She is imprisoned, running backwards and forwards, like Jane pacing backwards and forwards on the third story.... and she is also the 'bad animal' like ten-year old Jane, imprisoned in the red room. Bertha's appearance- goblin, half dream, half reality, recalls Rochester's epithets for Jane as a malicious elf, sprite, changeling.

Despite all the habits of harmony she gained in her years at Lowood, that on her arrival at Thornfield, she only appeared disciplined and subdued. She has repressed her rage and it will not be exorcised until the death of Bertha frees her from the furies that torment her and make a marriage of equality possible- and a wholeness within herself.

Her pilgrimage away from Thornfield is signaled by the rising of the moon, which accompanies other events in the novel. Her wanderings on the road are a symbolic summary of the wanderings of the poor orphan child which constitute her entire life's pilgrimage. Jane wanders far and lonely; starving, freezing, stumbling, abandoning her few possessions, her name, and even her self-respect, in search of a new home. But here she meets the Rivers- good relatives that free her from the angry memories of the wicked step-family. She has also torn off the crown of thorns that Rochester offered and rejected the unequal marriage he proposed. She has now gained the strength to discover her real place in the world. She concludes she was right when she adhered to principle and law. But her progress will not be complete until she learns that principle and law in the abstract don't always coincide with the deepest principles and laws of her own being. Her earlier sense that Miss Temple's teachings had only been superimposed on her native vitality has already suggested this to her. But her encounter with St John Rivers cements in thoroughly.

Where Rochester offers a life of pleasure, a marriage of passion, and a path of roses (with concealed thorns); St John offers a life of principle, a marriage of spirituality, and a path of thorns (with concealed roses). If she follows St John, she will replace love with labor. But Jane's repudiation of both Helen's and Miss Temple's spiritual harmonies hint that she will not accept St John's offer.

Rochester represents fire, and St John represents ice. But Jane, who has struggled all her life, like a sane version of Bertha, against the cold of a loveless world, ice will not do. St John, like Brocklehurst, is a pillar of patriarchy. Brocklehurst removed Jane form imprisonment only to immure her in a valley of starvation. Rochester tied to make her a slave of passion. St John wants to imprison her soul in the ultimate cell- the iron shroud of principle.

This attempt to imprison was certainly difficult to resist, especially on the heels of Jane congratulating herself on her adherence to principle. But her escape is facilitated by two events: she finds her true family, and comes into her inheritance. Now she is literally an independent woman. But her freedom is also signaled by the death of Bertha. The plot device of hearing each other's voices is the sign that the relationship for which both lovers had longed is finally possible.

Ferndean is stripped and asocial, buried deep in the woods out of the way. This suggests isolation of the lovers in a world where egalitarian marriages are rare, if not impossible. Perhaps Bronte was unable to envision a viable solution to patriarchal oppression, and the only thing to do was isolate oneself from it as much as possible.

While I don't know if this analysis is on point or not, I the points I've rewritten here interesting. Clearly a lot of thought has gone into the analysis, and it was interesting to read symbols and connections that I'd never thought of. It's the reason I bought the Norton critical edition- because I was hoping to read what other people had thought about the novel. I thought it was interesting

0 notes

Photo

A familiar tale. No longer current. Journeys completed. We are initially bound by our own shared passions and thrilling differences. And then comes a period when the same becomes the matter of our bridewells. Escape—together—is certainly possible. Though is takes great effort, patience, and—especially—a willingness toward self examination. The Prisoners Enclosed in this disturbing mutual wood, Wounded alike by thorns of the same tree, We seek in hopeless war each others' blood Though suffering in one identity. Each to the other prey and huntsman known, Still driven together, lonelier than alone. Strange mating of the loser and the lost! With faces stiff as mourners', we intrude Forever on the one each turns from most, Each wandering in a double solitude. The unpurged ghosts of passion bound by pride Who wake in isolation, side by side. —Adrienne Rich, 1950 (at Tongva Land) https://www.instagram.com/p/CkWpGRISfd2A9ju-jPL6WcsJXcHOJ1zVYGevog0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

Here comes my storm...

My sister from the sky

Rain

will touch you, will speak to you

through the same secret fairytale of approaching fall,

by scarlet maple leaves as love letters blown

to tell you

My heart is Yours

to stab or hold

#it digs an abyss in me to see him wounded and bruised each time I edit Bridewell prison caps - yet even his fragile state is enchanting#ratonhnhaké:ton#connor ac3#connor kenway#assassin's creed 3#ac3#ac edit#acedits#my ac3 edit#ac3 edit#assassin's creed 3 edit#ACIII#Assassin's Creed III#assassin's creed#my words#my writing#poems on tumblr#poem of the day#poems for him#poetsontumblr#mywords#love notes#free verse#mywriting#bridewellprison#prisoner outfit#fall-themed

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

The Whipping Cheer

The Whipping Cheer is a c. 1625 ballad about Bridewell, the (if)famous workhouse, and it's simultaneously a work song and a prison song. Workhouses were basically prisons which systematically used forced labour, and locked up "the idle poor": vagrants, beggars, thieves, "women of loose morals", the unemployed, the homeless, and anyone without an approved occupation.

Workhouses sucked ass. At their worst, which was often, they involved hard labour (repetitive, exhausting, and way too much of it every day), brutal corporal punishment, and worst of all, endless preaching about how idleness is the mother of all vices, and only hard work builds character for the likes of you (obviously this rigorous work ethic didn't extend to the rich, who could wank all day long for all anyone cared).

For more on English Poor Laws from a rogue's perspective, see No rest for the wicked: Anti-vagrancy laws in Tudor England, 1495-1604. This will bring us to the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601, which didn't invent but firmly established the institution of "houses or correction" (the precursors to workhouses) for many years to come. Bridewell Prison lasted from 1556 to 1855, and along with Bedlam, remains an iconic example of how early modern England treated its outcasts.

The Whipping Cheer comes in two parts, one for the girls who turn the spindle in Bridewell,

and one for the boys who beat hemp,

or at least will be when they get caught. (To be perfectly honest, I have questions about the 2nd part's meaning, so if anyone's super comfortable with Elizabethan English and wants to give it a shot, please let me know.) Hemp was indeed a product of Bridewell Prison, as we can see in this 1732 engraving by William Hogarth, from A Harlot's Progress.

Bridewell prison with inmates (including prostitutes and a card-player) beating hemp under the supervision of a warder holding a cane; a man stands with his hands in a pillory, with the sign "Better to Work than Stand thus" [x]

A few years back, the band Dead Rat Orchestra took some verses from the first part of the ballad, and made it a great song and a great video. You can read the original ballad in its entirety here.

youtube

Dead Rat Orchestra - The Whipping Cheer

Come you fatal Sisters three,

whose exercise is spinning:

And help us to pull out these threads,

for here’s a harsh beginning.

Oh hemp, and flax, and tow to to to,

Tow to to to, tow tero.

Oh hemp, and flax, and tow to to to,

Tow to to to, tow tero.

You punks and panders every one,

follow your loving sisters:

In new Bridewell there is a mill,

Fills all our hands with blisters.

Bess the eldest Sister, she

is stained much with honour,

And cannot endure the labour which

has been thrust upon her.

The blinded whipper he attends us,

if we the wheel leave turning,

And then the very Matron's looks,

turns all our mirth to mourning.

Gold and silver hath forsaken,

Our acquaintance clearly:

Twined whipcord takes their place,

And strikes our shoulders nearly.

#long post#Dead Rat Orchestra#The Whipping Cheer#prison ballads#prison#Bridewell#trs#the right to be lazy#poetry

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

BRIDEWELL GALLERY INDEPENDENT EXHIBITION

‘CAN I FORGET YOUR FACE?’

Several students and I exhibited our work in the Bridewell Gallery (independent [outside of university])

Having been inspired by Angelo Madonna’s work in the Bridewell, I decided to also exhibit my work in the cells. I thought my art worked well in the prison as the portrait paintings were of a criminal I knew from the past who had not been caught (NO JUSTICE TO THOSE HARMED BY HIM). Due to him committing suicide before the police could put him in a trial to send to jail, I decided to sentence him myself via paintings.

It was a very interesting space and overall, I thought the exhibition went very well. Despite my lack of inspiration and ideas for this semester, I think I did well, and the mark making for the paintings were very fun (but also frustrating because art is god damned hard) and I have Jasmir Creed to thank for the inspirational work she did.

#art#artist#art ideas#paintings#gouache#watercolour#oil paint#portrait#portrait paintings#criminal#prison#prison cell#bridewell#bridewell gallery#bridewell exhibition#bridewell studio#liverpool#university#ljmu#student blog#year 2 semester 2

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On April 8th 1820 Radical prisoners were taken from Paisley to Greenock jail under escort.

Following on from Monday’s post which covered The Battle of Bonnymuir.

Economic downturn after the Napoleonic Wars led to higher prices and unemployment. There was general unrest among workers and attempts to achieve political reform. Artisan workers, including weavers were particularly active, calling for strikes across central Scotland. Bands of radicals rallied and there were many skirmishes with the armed forces who had been called out to deal with the threat of unrest. The ringleaders and anyone suspected of being part of the unrest were arrested and jailed. Paisley gaol was full so five prisoners were sent to Greenock to be imprisoned here.

A rumour about this soon got out and a mob gathered in the streets around the Bridewell. The five radical prisoners duly arrived in a cart escorted by the Port Glasgow Volunteers with a fife and drum playing. The prisoners were put in jail and the Volunteers prepared to return to Port Glasgow. The crowd turned on them. One of the local magistrates Mr Dennistoun tried to calm things down but to no avail. The mob began throwing stones and bottles. Several of the Volunteers were hurt and fired a few shots in the air to warn the mob. This only proved to anger them and eventually the Volunteers fired on them injuring and killing some of the crowd.

The mob gathered together their own weapons, even pulling up iron railings en route, and followed the Volunteers on their way to Port Glasgow intending to fight. They only got so far when they heard that more militia were being sent to Port Glasgow to help the local Volunteers. At this, the crowd dispersed. Meanwhile, some had broken into the prison and released the radicals (but none of the other prisoners).

A detachment of hussars and guards were sent from Glasgow by steamboat to Port Glasgow in case of any trouble. But by the time they arrived the next day all was quiet.

The five Radical prisoners, who were never re-captured.

A public inquiry was held, at the end of which the Port Glasgow Militia was fully exonerated.

A list of the dead and wounded appeared in the Glasgow Herald -

Adam Clephane (48 years) dead

James Kerr (17 years) dead

William Lindsay (15 years) dead

James MacGilp (8 years) dead

Archibald Drummond (20 years) dead

John Mac Whinnie (65 years) dead

John Boyce (33 years) dead

Archibald McKinnon (17 years) dead

(Died of his wounds on 5th May 1820)

Mrs Catherine Turner (65 years) leg amputated

Hugh Paterson (14 Years) leg amputated

Peter Cameron (14 years) flesh wound

John Gunn (24 years) flesh wound

John Turner (22 years) flesh wound

Gilbert MacArthur (18 years) slight wound

Robert Spence (11 years) slight wound

David MacBride (14 years) slight wound

John Patrick (30 years) slight wound

George Tillery (25 years) slight wound

The pics show the Radical War Memorial, Bank Street, Greenock and is called “The Hands of the Fallen”. And a memorial on the east side of Bank Street, stones inset into the retaining wall of the Well Park record the ages and names of those killed: feature created by Broughton-based landscape designer James Gordon.

24 notes

·

View notes