#but I just associate marriage so strongly with both gender roles and Christianity both of which seriously wig me out

Text

The more I think about it the less I have even the slightest desire or need to get married or think that there's any chance that I ever will. I just don't get it at all. Completely not for me. If I ever end up technically getting legally married for financial reasons there'll be no ceremony.

#for context been with my s/o for 10 very happy years and have every intention of staying together for the rest of my life#I think not only is it just........ pointless but also it's that marriage would make me... a 'wife'?#it's so... gender binary#you know?#I know it doesn't have to be and absolutely more power to nonbinary folks who are married or want to get married!#but I just associate marriage so strongly with both gender roles and Christianity both of which seriously wig me out#also as for a wedding ceremony I legitimately cannot think of a single worse thing#draco speaks#but yeah mostly I just don't get the point? like okay I guess it signals your commitment to each other but my s/o and I don't need to?#we already know that#also we're both completely open to polyamory at the same time so like that aspect of marriage is stupid and not relevant to us

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nonbinary Genders Throughout History

I started compiling these with the intention of posting them on trans visibility day as a congrats to @neurodivergent-crow getting their top surgery consultation (woot!), but I kept finding more and more and more third gender figures and it developed into this ever-growing monster of a list of genders to research about... and next thing I know we’re entering Pride month.

I've already found 24 extinct genders and 48 modern ones, so I figured I could start with the extinct ones I’ve already researched and post more instalments as I go so people don’t have to scroll for half an hour to get to the end of this post. ;P

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Ay’lonit [איילונית] (Ancient Israel)

A person who is identified as “woman” at birth but develops “man” characteristics at puberty and is infertile.

There are 80 references to this gender in the Mishna and Talmud and 40 in the classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Androgynos [אנדרוגינוס] (Ancient Israel, from at least 1st century CE to 16th century CE)

A person who has both “male” and “female” sexual characteristics.

There are 149 references to the gender in the Mishna and Talmud and a whopping 350 mentions in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Assinnu (Assyria, Mesopotamia)

An ambiguous gender often represented as being a passive man, but which also at one point was "listed among a group of female cultic attendants".

In Mesopotamia, the man was supposed to be sexually active while the woman took on the passive role. Because of the assinnu's passivity, they were categorized as a third gender figure.

-----------------------

Çengi (Ottoman Empire, now Turkey)

According to Şehvar Beşiroğlu they were “dancers who are non-moslems or [Rromani]”.

From what I understand the term has now evolved to be the feminine form of the noun “dancer” in Turkish, but it was originally considered to be a gender separate from man or woman, which is why I put it in this extinct gender list.

-----------------------

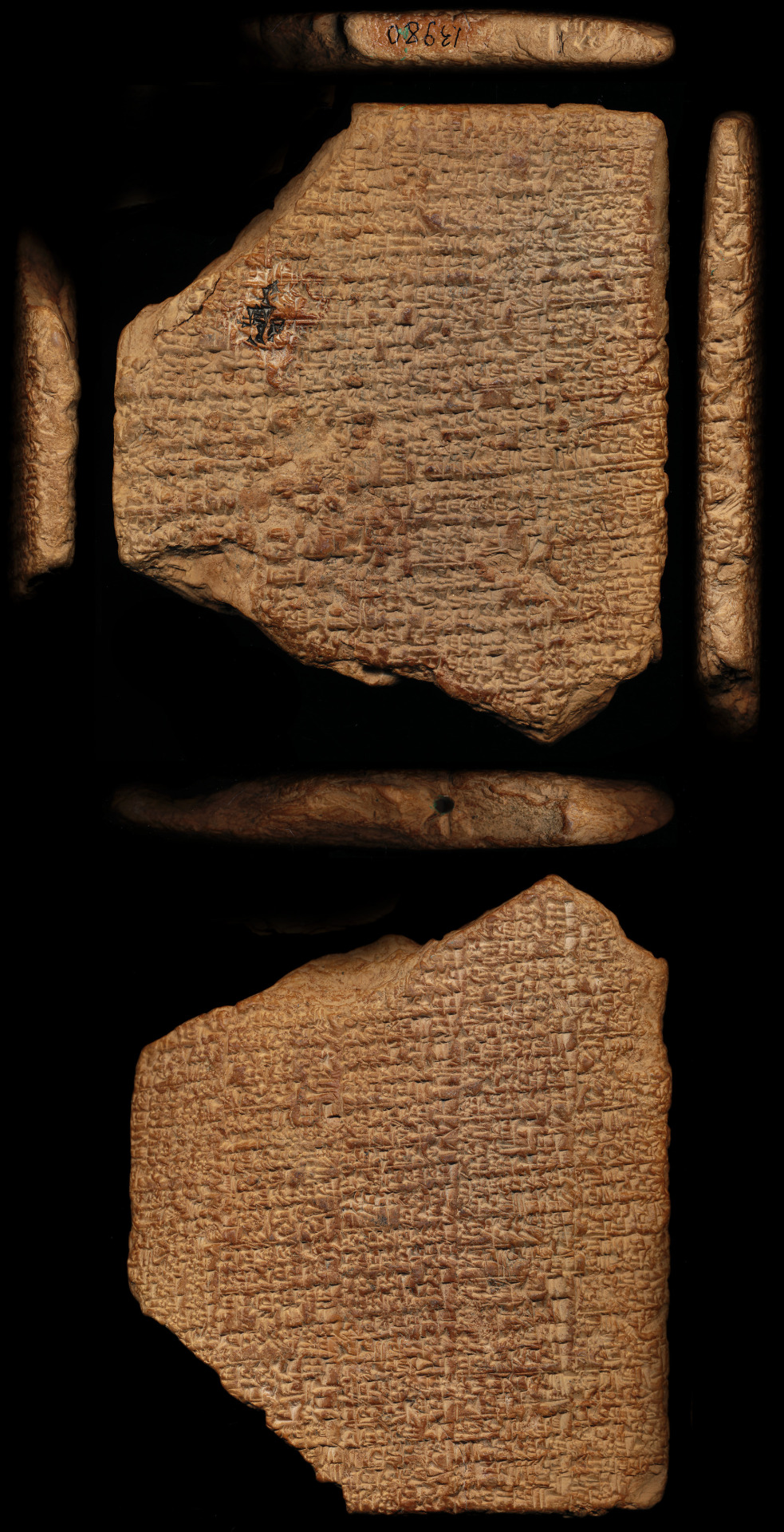

Gala (Sumer, Mesopotamia, 3000 BCE)

^ Cuneiform tablet of Old Babylonian Sumerian proverbs mentioning the gala

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a "chanter of laments".

Simply working as a professional lamenter categorized them as feminine because laments were typically performed by women (not unlike how men who practised seiðr magic were regarded in Norse culture).

During the Old Babylonian period, the role of the gala expanded and became a synonym of kalǔ, becoming a singer who dealt with music-related areas of the worship of Ishtar.

-----------------------

Girseqû (Mesopotamia)

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a childless figure within palace administration.

-----------------------

Kalǔ (Akkad, Mesopotamia)

^ According to the inscription, the beardless person is Ibni-Ištar, kalû of Ištar-of-Uruk.

A person who is identified as “man” at birth who is a "chanter of laments".

Simply working as a professional lamenter categorized them as feminine because laments were typically performed by women (not unlike how men who practised seiðr magic were regarded in Norse culture).

During the Old Babylonian period, the role of the gala expanded and became a synonym of kalǔ, becoming a singer who dealt with music-related areas of the worship of Ishtar.

The kalǔ were institutionalized into religious practice and ritual in order to maintain strong social distinctions between men, women, and a third gender comprised of non-conformative males.

-----------------------

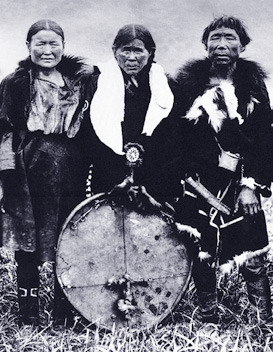

Koekchuch (Itelmens, Siberia, mid 18th - early 19th century)

Individuals assigned to be men at birth but “who wear women's clothes, do women's work*, and have nothing to do with men, in whose company they feel shy and not at their ease”.

It was not uncommon for men to have up to three wives as well as one or more koekchuch (some men reportedly bypassing having any concubines altogether and preferring to have one or more koekchuch instead).

Note 1: Just as a heads up, the link for this gender has transcriptions of material from the 1750s, and as such features some racist, homophobic, and transphobic language.

It’s nothing overly colourful, mostly just the writer having the judgy kind of jerkward attitude you’d expect from a 1700s Christian ethnocentric academic, but I figured I’d give y’all a heads up just the same. :)

Note 2: The book this info comes from, Pacific Homosexualities by Stephen O. Murray, is a treasure trove for anyone interested in the subject, as it features tons of primary sources you’d be hard-pressed to find access to if it’s not your field in academia.

It costs around $40 on Canadian Amazon.

---------------------

Kurgarrǔ (Sumer, Mesopotamia)

Kurgarrǔ were people assigned as men at birth who took part of the cultic performance for Ishtar and presented themselves as militant and masculine.

The kurgarrǔ were considered a third gender because of their involvement in the worship rites for Ishtar, a role that was considered to be ambiguously gendered because Ishtar was an ambiguously gendered deity.

-----------------------

Lύ-sag/Ša rēši (Mesopotamia)

A palace attendant typically in charge of women’s quarters within a palace.

The term Lύ-sag was interchangeable with Ša rēši.

It’s implied in contemporary accounts of the Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods that they were eunuchs, though there are no such mentions in other periods in the culture’s history.

-----------------------

Mukhannath [مخنثون] (Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, Middle East, 4th-7th century CE)

A term used in Classical Arabic to refer to men who were perceived as effeminate.

During the Rashidun era and the first half of the Umayyad era, they were strongly associated with music and entertainment.

During the Abbasid caliphate, the word itself was used as a descriptor for men employed as dancers, musicians, or comedians.

In later eras, the term mukhannath was associated with the receptive partner in gay sexual practices, an association that has persisted into the modern day.

-----------------------

Paṇḍaka (Buddhist, 2nd century BCE)

Mentioned in the Vinaya as one of the 4 genders, it is a somewhat catch-all term for anyone who does not conform to the other 3 genders (for the other Buddhist third gender mentioned in Buddhist scripture, scroll down to “Ubhatobyanjanaka”).

“As the Vinaya tradition developed, the term paṇḍaka came to refer to a broad third sex category which encompassed intersex, male and female bodied people with physical and/or behavioural attributes that were considered inconsistent with the sexual ideal of man and woman.”

-----------------------

Pilpilû (Mesopotamia)

A member of the Ishtar cult** with feminine traits.

** When talking about ancient theology, “cult” doesn’t have quite the same meaning as it does in everyday language. It just means they worshipped Ishtar.

-----------------------

Sadhin (Gaddhi people, in the foothills of the Himalayas)

People identified as women at birth who renounce marriage and dress and work as men, but retain female names and pronouns.

-----------------------

Sanskrit Third Gender

The Mahābhāṣya, a book on Sanskrit grammar from circa 200 BCE, claims that the 3 linguistic genders of Sanskrit are based on “the three natural genders”.

The Ramayana and the Mahabharata (the two Sanskrit great epic poems) also indicate the existence of a third gender in ancient Indic society.

-----------------------

Saris [סריס:] (Ancient Israel)

A person who is identified as a “man” at birth but develops “woman” characteristics at puberty and/or is lacking a penis.

A saris can be “naturally” a saris (saris hamah), or become one through human intervention (saris adam).

There are 156 references to this gender in mishna and the Talmud and 379 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

-----------------------

Sḫt (Egypt, 2000–1800 BCE) [pronounced “sekhet”]

“Someone who is neither a man nor a woman.”

Because the gender is known from only a few pottery shards, it’s not entirely clear whether the ancient Egyptians were referring to man and woman in the sense of sex or gender roles or both.

Note: Since the bulk of early archaeology was dominated by cishet white men who believed only two genders exist, the term has historically been generally translated as “eunuch”.

However, there’s little to no indication that sḫt were all biologically male (let alone castrated ones at that), and the eunuch interpretation of the word has begun to be questioned by gender study historians.

-----------------------

Tamil Third Gender (x2!)

The Tolkappiyam, the oldest known book of Tamil grammar, refers to intersex folk as a third "neuter" gender, as well as mentioning a feminine category of unmasculine males.

-----------------------

Tīru (Mesopotamia)

Not much is known about this gender.

Historians believe it was likely a childless castrate who had a part of palace bureaucracy (I don’t know if this is like the case of the sḫt and cishet dudes just have a propensity to assume “third gender person assigned male at birth = eunuch” or if there’s evidence to back this up).

-----------------------

Tumtum [טומטום] (Ancient Israel)

A person whose sexual characteristics are indeterminate or obscured.

According to Maimonides' Mishneh Torah, Mada, Avoda Zara, 12, 4 Tumtum is not a separate gender exactly, but rather a state of doubt about what gender a person is (kind of like a Schrödinger’s gender?).

I added it to the list because I thought that, like myself, some folks might find it interesting (and it is gender-related...). :)

-----------------------

Ubhatovyanjañaka (Buddhist, 2nd century BCE)

Mentioned in the Vinaya as one of the 4 genders, it is the gender of people with a dual sexual nature (for the other Buddhist third gender mentioned in Buddhist scripture, scroll up to “Paṇḍaka”).

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

P.S. I tried to not use transphobic language, but I’m still learning, so if anyone sees any error please let me know so I can fix it and learn from my mistake! :)

#pride month#woot woot#nonbinary#third gender#transgender#lgbt+ positivity#lgbt representation#lgbt+ history#transgender history#non-binary#happy pride 🌈#read your bible#torah#babylonia

33 notes

·

View notes

Link

A prominent Christian think tank has come out fiercely in favor of better family leave policies, defending federally mandated family leave policies on theological grounds.

“Christian families can form themselves along a divine vision of work and family as holistic complements,” a report released Tuesday reads, “As citizens and culture-shapers, Christians should advocate for and develop policies and practices that protect, rather than fragment, family time.”

The report, authored by Katelyn Beaty and Rachael Anderson of the Center for Public Justice, advocates for changes both on a federal scale, calling for an expansion of the Family Medical Leave Act. Pushing beyond public policy, though, the report also specifically targets gender imbalances within families.

The report follows a Senate finance subcommittee hearing last week on paid family leave, and a growing debate over the government’s role in providing resources for child care. Prominent figures on the right, including Sen. Joni Erst (R-IA) and first daughter and presidential advisor Ivanka Trump, as well as Democrats like Kristen Gillibrand (D-NY) have made the expansion of paid family leave a cornerstone of their policy strategy. Gillibrand’s bill with House cosponsor Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) — calling for at least partial payment to workers on leave for up to 12 weeks — was introduced last year.

”Christian teaching recognizes families’ crucial role in society to nurture and protect the sacredness of life at all stages,” the Center said in an email to journalists. “Paid family leave is an important way to promote family life and family cohesion, particularly for the many households that cannot otherwise afford to elect family care over paid work.”

But the relationship between child care, family life, work, and the evangelical community in America has not always been so straightforward. The history of the relationship between labor, parental support, and government programs to support family life in America has, for the past several decades, been strongly influenced by evangelical opposition to any perceived threat to the nuclear family.

While the authors represent just one Christian think tank among many, their report suggests that, for many evangelical communities, the “traditional” family model — a heterosexual married couple, with a husband who is a primary breadwinner and a wife who is a primary caregiver — is increasingly unsustainable, especially under current American economic conditions and family leave laws.

The report echoes a critique of capitalism, and of the devaluing of family life, heard elsewhere across the contemporary Christian world. Pope Francis, for example, has been a frequent critic of capitalist pro-corporation policies that minimize work-family balance.

However, this point of view has not always been prevalent among Christian leaders. It’s impossible to understand the history of family policy in America without recognizing the role that the nascent Christian right played in advocating against federally-mandated interference in childcare policy, and in advocating for the near-unbridled liberties of corporations. The relationship of Christianity to work-family balance, particularly when it intersects with state interference, has long been a complex and ambiguous one.

After decades of incremental steps and compromises, the current federal law, the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, allows employees working at least 25 hours a week with companies with at least 50 employees to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for family medical reasons. These include childbirth, adoption, and family illness. This is among the least generous policies in the world.

Meanwhile, the US lacks any semblance of universal child care, which can be a burdensome cost for many families. In fact, according to the report, “child care in the United States costs on average $9,589 per year, a significant portion of the annual income of a working-class couple. Yet if one parent stays home, one salary may not be enough to support the family.”

Still, the authors say, Christians have a role in reversing course in public policy around paid leave and child care as a way to uphold its value of families as a cornerstone of Christian life. “Christians who recognize the socially foundational nature of family,” the report urges, “must not only talk about the importance of family, but enact policies and create cultures that tangibly demonstrate its importance. Protecting and enabling family time at crucial moments — whether birth, adoption, illness or death — is one essential way to uphold the enduring value of the family.”

The report advocates for equal family leave for both mothers and fathers. It urges change in policy at both corporate and governmental levels to ensure that mothers and fathers alike are uniformly given the opportunity to, for example, take maternity or paternity leave, or take leave to care for a sick child.

In addition to advocating the broadening of family leave, Beaty and Anderson specifically target issues of gender imbalance in child care, including the expectation that working mothers work a “second shift,” balancing the bulk of housework and parental duties with a full-time job.

“A biblical account of work and family life … [reminds] us that work and family were each designed for good purposes,” the report says. “God did not intend work and family to be experienced as competing spheres of responsibility, but rather complementary ones. Christians believe that every sphere of life falls under the lordship of Christ and is thus a place of God’s blessing and provision. God calls many people to enter into a marriage covenant and to bear and raise children; God also calls many people to work ‘with willing hands’ (Proverbs 31:13) in order to provide for family needs, effect cultural change and take the gospel into the marketplace. Church teaching honors these calls of responsibility.”

Beaty highlighted the importance for Christians of challenging an unquestioning adherence to capitalist approaches to worker productivity. “Christians across the board would agree that the workplace should be a place of a humanizing effect on a person’s life rather than a dehumanizing effect. And so obviously any kind of work that creates physical or mental or emotional harm for a worker is to be critiqued and to be changed,” she told Vox in an interview Wednesday.

Still, she acknowledged that Christian leaders have work to do in ensuring they practice what they preach.

Citing the mixed track record of some faith-based organizations of providing sufficient family leave, Beaty said, “We see that there is often a gap between what Christian leaders say and believe theoretically about the primacy of the family, and the workplace, and cultures that they create that take time away from the privacy of the family. So we want to help address that gap.”

That gap has, historically, been tied in part to the “culture wars,” and the Christian right’s role in it.

The early 1970s ushered in a growing new wave of feminism and gender equality. With it also came the very beginnings of evangelical activism, eventually taking on the moniker of the Moral Majority, a coalition of evangelical Christian leaders and figureheads who actively sought to bring a (largely white) evangelical Christian perspective to the Republican Party, and into government more broadly.

The issue of government-backed child care rose to prominence in the “culture wars” as early as 1971, as more middle-class women pushed for the ability to choose between homemaking and pursuing careers outside of the home.

As Nancy L. Cohen recounted in 2013 in the New Republic, Congress passed a bipartisan Comprehensive Child Development Act in 1971. The act earmarked $2 billion (or about $10 billion in today’s economy) to open a network of federally funded child day care centers, to provide education, food, and medical care to all children on a sliding financial scale. The bill seemed like a shoo-in.

Then, President Richard Nixon vetoed it. Why? According to Cohen, the president’s special assistant and speechwriter, Pat Buchanan convinced Nixon that universal child care opened the door to government control of child-rearing and the collapse of the nuclear family. Buchanan (who is Catholic, but is often associated with the largely evangelical members of the Moral Majority movement) has frequently characterized his opposition to the act in the bombastic language of the culture wars.

In his veto statement, which was drafted by Buchanan, Nixon argued that if the federal government plunged headlong financially into supporting child development, it would commit the vast moral authority of the national government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing, and that it would in turn lead to the collapse of family structures.

Buchanan frequently made ominous reference, too, to communist systems of indoctrination, telling interviewers, “I had been to the Soviet Union, spent 18 days there. … They took us to the young pioneers, (laughter) and these 5-, 6-year-olds were chanting Leninist slogans. And you said, you know, what is going on here? It was eerie.”

Years later, Buchanan defended his position and took full credit for Nixon’s actions, saying, “The federal government should not be in the business of raising American’s children.” He added, “If we hadn’t stopped it, I think you’d have an entitlement program now of enormous size with these federal day care centers, and they would be growing and growing and growing once you got it on the books.”

Not only did Nixon veto the bill, but he reportedly rejected the pleas of his other advisers, who urged him to leave the door open to less costly alternatives. Federally provided child care in America was deemed not just pragmatically tricky, but ideologically unsound.

From then on, as Gail Collins writes in her history of the 20th-century female experience, When Everything Changed, debates over childrearing became central to the American culture wars. During the Gerald Ford administration, congressional leaders tried to resuscitate a more moderate version of the bill, only to face extreme backlash from grassroots religious groups. Thousands of letter-writers contacted their representatives, falsely accusing Congress of trying to make it possible for children to sue their parents for making them do chores, or creating “a godless Russian/Chinese type regimentation of young minds.”

Much of the outcry, according to Collins, was inspired by a hoax flyer about the bill, evidently authored by a Bible camp director from Kansas, that seems to have circulated around South and Midwest. The bill failed.

In an article in the journal Feminist Studies, Rosalind Pollack Petchesky explores how the Christian right became defined by two “interlocking themes”: opposition to feminism (and thus to provisions that would threaten the female-homemaker model) and opposition to government intervention in private corporations.

A “pro-family” ideology characterized by opposition to abortion, divorce, feminism, and homosexuality became de rigueur for Moral Majority figures like Buchanan and Jerry Falwell, linking Catholics and evangelical Protestants. Or, as the 1980 Republican party platform would have it, “We oppose any move that would give the federal government more power over families.”

While the Christian right never explicitly condemned family leave policies the way it, for example, mobilized against federal childcare, it nevertheless made firm its commitment to minimizing any mandatory or federal interference into family life. The preservation of “family life,” in the abstract — which is to say, as an anti-feminist, libertarian ideal — became increasingly synonymous, with the privileging of corporate license to set family policy as it saw fit.

Beaty stresses that her work at the Center for Public Justice is non-partisan, and that they do not formally endorse any particular policy position. Still, she said, “some of the [right’s historical] emphasis on protecting the free market, protecting corporations’ freedom — I think that’s giving the market too much control … over the primacy of the family. As Christians, we think that solutions to social problems are not just problems of individuals making decisions, but that there has to be kind of a concerted, common-good effort to create standards, policies, ethical, moral commitments for workers to choose time with their families.”

Noting that too many families don’t have the financial option to have a parent stay home with their child, Beaty said, “Pat Buchanan and other more politically conservative evangelical leaders of the ’80s and ’90s assumed too much about individuals’ ability to be with their families.”

While, of course, the report represents just one Christian point of view, it represents an avenue of possibility for Christian discourse, and the “pro-life” agenda, in America: a willingness to treat issues of life and family, and the structural inequalities government them, beyond the traditional American “hot-button” issues of abortion and same-sex marriage. In so doing, Christian advocacy groups have the opportunity to broaden and diversify their political reach, and speak out (as many did about family separation) about issues that transcend sectarian lines.

Original Source -> Christians are calling for better family leave policies. That wasn’t always the case.

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Link

ALISA GANIEVA’S APPEARANCE in the world of Russian literature took everyone by surprise, in the literal sense. A critic by training, she published her first work of fiction, the novella Salam, Dalgat! (Salam tebe, Dalgat!), when she was 25, under a male pseudonym; when the novella received the Debut Prize in 2009, Ganieva outed herself as a woman at the awards ceremony. Two novels written under her own name followed, enjoying similar critical success: The Mountain and the Wall (Prazdnichnaia gora, 2012) was longlisted for Russia’s National Bestseller award, while Bride and Groom (Zhenikh i nevesta, 2015) made the shortlist for the Russian Booker. What sets Ganieva apart from most other contemporary Russian writers has to do with what being a “Russian writer” actually means. Her background is culturally and linguistically hybrid. She was born in Moscow but is ethnically Avar, the Avars being the largest ethnic group in Dagestan, a Muslim-majority republic of the Russian Federation located in the North Caucasus. (It neighbors the more sadly famous Chechnya.) Although Ganieva later returned to Moscow, she grew up in Dagestan. As she explains in an interview, her first language was Avar, but she writes in Russian, with which she also grew up, as it is Dagestan’s lingua franca.

This movement between places, cultures, and languages is characteristic of Bride and Groom. Like her previous works, the novel is set in Dagestan, in the small village where Patya and Marat — the bride and the groom — are from and to which they have come back to visit their families. Marat works as a defense lawyer in Moscow, where Patya has just spent a year working in a courthouse copying documents. They are both intimately familiar with village culture and comfortable with Moscow’s modern ways. Intermingling in the novel also occurs on the linguistic level: while Ganieva writes in standard Russian, she injects many words and expressions from Avar and Arabic, making hers a specifically Dagestani Russian variant. In Ganieva’s original texts, these words and expressions are translated into Russian in footnotes, which presents her English-language translator, Carol Apollonio, with the question of how best to handle them in translation. Apollonio opts for two different approaches: in The Mountain and the Wall, she puts these terms in a glossary at the end, whereas in Bride and Groom, possibly because there are fewer of them, she italicizes them to mark their foreignness but leaves them untranslated, asking readers to rely on context for a general understanding of their meaning.

Literature by Dagestani writers is virtually unknown in the West. The press release by Ganieva’s United States publisher, Deep Vellum, notes that The Mountain and the Wall is the first novel by a Dagestani writer to be translated into English (making Bride and Groom the second). Yet even those living in the Russian Federation are poorly versed in writing from Dagestan, having been raised, as was Ganieva herself, on a Russian literary canon overwhelmingly made up of writers of European descent. The rise of a Dagestani author with Dagestani-themed works challenges this hegemony and alters the way the Caucasus, which occupies a prominent place in Russian writing, has been traditionally represented.

As part of its colonial expansion during the 19th century, the Russian Empire sought to bring the region under its control through a series of military campaigns, a conflict that resumed in the late 20th century, as Russia attempted to suppress separatism in Chechnya. Before he became a pacifist and insufferable moralist, the young profligate Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) went to the Caucasus and joined the army after piling up gambling debts. Several writers were exiled to the remote region for displeasing tsarist authorities — notably Mikhail Lermontov (1814–1841), who fought in the military there. Indeed, the Caucasus as a literary setting is most often associated with Russian Romanticism and Lermontov, its most famous practitioner. His novel A Hero of Our Time (1840), whose Byronic protagonist finds himself stationed in the Caucasus like his creator, serves as a foundational text of the Russian novelistic tradition. This work highlights the way many European Russian authors exoticized the Caucasus as the polar opposite of European Russia: warm, lush, romantic, and full of adventure, yet also a foreign, non-Christian space of savagery and violence.

If the Caucasus has for the most part been written about from the point of view of Russocentric outsiders, Ganieva represents it as an insider focusing on Dagestani people and events, while sending up Russians who have no cultural understanding of the region. In the novel’s opening chapter — the only one set in Moscow — Patya becomes the object of fascination for a group of Russians when she goes to an acquaintance’s dacha for a party. When one of the guests begins describing his time in the Caucasus while serving in the army, she laughs at him — “You must be mixing up the nineteen-nineties with the nineteenth century” — and subsequently decides that it is easier not to argue when he asks whether she has to undergo a “gynecological exam every month” to ensure that she is still a virgin.

Ganieva’s works show a society that is much more nuanced than these Russian stereotypes suggest. Dagestan is a place where tradition vies with modernization. Those with hardline religious views chat up prospective partners on the internet: for example, Timur, a fundamentalist political youth organizer and denier of evolution, insists that he and Patya are meant to marry because they have been corresponding for several months. Crucially, Ganieva depicts a range of characters’ Islamic practices. Patya and Marat are modern secular Muslims. Patya tells Timur, “I don’t pray. That’s not happening,” while Marat refuses to consider marrying a woman who wears a headscarf and throws a proselytizer out of a cafe in which he and Patya are on a date — itself a modern concept. Marat’s friend, Rusik-the-Nail, eccentric by his society’s standards, walks out into the street with a placard declaring, “I am an agnostic,” for which he unsurprisingly suffers immense consequences. While most of the society is religious, there is a definitive split between families like Patya’s and Marat’s, who practice a conventional form of Islam, and those like Timur and his friends, who represent the Wahhabi fundamentalism encroaching on the region, which many of the other characters find abhorrent. This split is embodied in the two warring mosques in the village: the regular “mosque on the avenue” and the extremist one “across the tracks” that radicalizes its attendees. While fundamentalism is spreading — more women are wearing hijabs and there are violent clashes between the mosques — it has not completely taken hold. Ganieva has stated that she sees the tendency toward hardline practices as a problem in the region, and her works capture Dagestan in a moment of flux, the path it will head down still unfinalized.

Moreover, as a woman writer, Ganieva injects a different gender dynamic into the Caucasus narrative. The Russians who wrote about the region were largely men writing about male protagonists; Ganieva’s own Salam, Dalgat! and The Mountain and the Wall also feature male protagonists, with the latter especially depicting women as secondary characters in largely clichéd terms. But she takes a different approach in Bride and Groom, alternating the chapters between Patya’s and Marat’s points of view. Arguably, Patya’s point of view predominates, at least until the very end, since her chapters are in first person, while Marat’s are in third person. As a character, Patya is independent and headstrong, with ideas that conflict with the traditional mores of her society, which brand women sluts for sleeping with their boyfriends, as happens to her friend, and even prohibit them from wearing pants in public. She questions the narrowly domestic roles women are expected to assume in a society obsessed with marriage; as she wryly observes when she goes into town, “A wedding salon on every block […] Weddings, weddings, weddings. As though there was nothing else to do.”

To be sure, this society insists on marriage for men as well as women. Marat comes home to his village because his parents have rented out the banquet hall for his wedding and a bride must be found in short order. His mother personally escorts him to meet the women on the list she has compiled for this purpose. Yet marriage demands affect women’s lives more. While his parents will lose their deposit on the banquet hall if a wife is not found, Marat can return to his job in Moscow. In contrast, Patya’s mother refuses to let her go back to Moscow, insisting that she must stay in the village and find a husband; at 25, she is reminded at every turn that she is “[a] little long in the tooth for a bride.” While she eventually becomes engaged to Marat, she does so on her own terms. Even though everyone strongly encourages her to marry Timur, she rejects him because he treats her like an object, and although her family ultimately agrees with her choice of groom, it initially goes against their wishes. At the same time, Ganieva does not always depict Patya consistently. In the scene of their declaring their love for each other, which occurs toward the end of the novel, Patya’s responses to Marat — for example, she assures him, “Go ahead and tell me. I will understand,” when she clearly doesn’t — seem as though Ganieva is relying on cultural clichés of how women in love should talk to the men they are in love with. (In Apollonio’s translation the scene reads more neutrally than in Russian.)

Patya and Marat’s courtship unfolds against the social and political tensions around them, which form the backbone of the story and ultimately determine its outcome. The central event occupying everyone as the two arrive in the village is the arrest and imprisonment of Khalilbek, a man whose status in the community is nothing short of mythic:

Khalilbek was omnipotent, omnipresent, and more […] He had a finger in every pie and knew the details of the most minor matters; at the same time, he was behind all major shifts in power, missing persons cases, and fateful decisions.

Because of his epic powers, many believe he is “Khidr, a prophet,” a man of God and divine wisdom. At the same time, he is imprisoned on charges of corruption and murder and is directly responsible for the death of Adik, Marat’s half-brother and his father’s illegitimate son, whom Khalilbek ran over in his car several years previously. Although Khalilbek’s highly ambiguous nature is never fully resolved, the surprising reason behind Adik’s murder and Khalilbek’s role in the closing scene of the novel does suggest a particular reading. It is the confluence of external circumstances — Adik’s past actions, the jealousy of Marat’s ex-lover, the unscrupulousness of the local police in their efforts to root out fundamentalism — that ultimately decides the private fates of Patya and Marat, underscoring individuals’ precarious position in a world largely out of their control.

The novel’s ambiguous ending, while not entirely satisfying, works well enough. What works markedly less well is Ganieva’s decision to include an afterword in the English version, whose aim, as she explains, “is to address a quiet but very important subtext of the novel that has to do with Sufism, an esoteric Muslim teaching.” To be sure, Sufism is not a topic with which most of her English-speaking readership will be familiar, and it is understandable why she feels the need to elaborate (although she seems not to have felt this need with her Russian audience, most of whom would be equally unfamiliar with it). Looking back at the novel with this subtext in mind does change one’s perception, including the interpretation of the ending, which is Ganieva’s goal. However, adding an afterword in which an author instructs her readers how to read her novel is decidedly an overreach. This misstep aside, Bride and Groom is an intelligent and interesting read that brings into focus a little-known part of the world while challenging cultural and literary clichés that have clustered around it. The fact that this corrective is the work of a woman author and a woman translator may be coincidental, but it is hardly surprising.

¤

Yelena Furman teaches Russian language and literature at UCLA. Her research interests include contemporary Russian women’s literature, Russian-American literature, and Anton Chekhov.

The post A Voice from the Caucasus: On Alisa Ganieva’s “Bride and Groom” appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2MQKSSt

0 notes