#c: henry ii

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

King Henry II, last royal portrait before his death in 1998

Born: 1915 - Died: 1998

Reign: 1932-1998

His wife, Queen Mother and Duchess of Sussex, Gwyneth

Born: 1938 - Still living

Married to King Henry II in 1958

He famously disliked sitting for portraits with her in the room.

Together their issue totaled 6 children, with only 3 of them surviving to adulthood-- Rosalinde, Duchess of Worcester (b.1960- ; abdicated, estranged from the royal family), Princess Anne (b.1967- ?), who went missing in 1992 and who has never been found, and King George X (b. 1969- ).

#LORE DROP TIME#c: george x#c: gwyneth#c: henry ii#c: anne the lost#c: rosalinde the estranged#I finally got the dates and stuff for the royal line going back to the 1600s#so the lore will be more consistent going forward lol

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

'That was the first good sleep I've gotten in a long time.' ( from h. henry. / @ladyseidr )

STILL HALF ASLEEP, WILLIAM HUMS. IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN A DISAGREEMENT OR AN AFFIRMATION, but it’s impossible to tell due to the fact his head is buried in Henry’s shoulder, blocking out the daylight and the looming threat of getting out of bed. Which is a threat, a major one, in his opinion, when everything outside of bed is so cold — Henry’s warm, warmer than William thinks he’s ever been, and he wants to refrain from moving for as long as possible. “ Shut up, ” he mumbles, lifting his face long enough to speak coherently, “ go back to sleep. Keep having a good sleep. If you leave this bed I think I’ll go crazy and murder you or something. ”

Safe to say he’s slept well too. As a result, his face presses back into Henry’s shoulder firmly: a silent, pushy demand to return to sleeping peacefully. The rest of the world can wait. For now, William is content to rest with Henry by his side.

#(ii) man behind the slaughter — roleplay thread.#(c) answered.#(( TH. THEM ))#(( i kept the verse vague so feel free to see this in any direction / time !!!! ))#(xox) last man standing: william & henry.#(ui) original: standard.#a; ladyseidr#(u) i always come back: queue.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ghostbird-7 linked me to the GQ write-up about Christopher McQuarrie and I'm reeling. I'm losing my entire fucking mind.

I've felt an admiration and kinship for McQ's philosophy on creating art for years now and the specific way he does it, his journey from artist-first to the guy who is parachuted in to save movies from themselves to a tradesman and the back to an artist, the focus on methodology. I'm going to expire.

this one fucking bit:

McQuarrie began to notice patterns. Mistakes that were made, over and over again. Studios soon recognized this particular talent. Once, McQuarrie told me, in his capacity as a movie ER doctor, he was parachuted in on two separate films in distress, on which two totally different filmmakers both had an Apocalypse Now poster in their office. “And I said, ‘Let me tell you how to make Apocalypse Now. Let me help you because it’s so simple. First, make The Godfather, then make The Conversation, then make The Godfather Part II. Then take all of your personal capital and all of your professional capital and gamble that and your marriage and the life of your leading man and your sanity on a movie about a war that nobody wants to remember. And then spend years shooting it and put it in cinemas and no one will come and it will take decades before people recognize what it is. That’s how you make Apocalypse. Now let me tell you something: You’re not making Apocalypse Now.’ ”

because its so simple MCQUARRIE YOU MASSIVE BITCH. /fans face

ENTIRE ARTICLE UNDER THE CUT bc man that fucking paywall is a bitch to get around

When it comes time to start a new Mission: Impossible movie, the first thing that happens is Tom Cruise, the star of the franchise, and Christopher McQuarrie, its longtime writer-director, sit down together and they ask each other: What do you want to do? The answer is inevitably: something difficult and dangerous.

Years ago, when Cruise and McQuarrie were beginning to sketch out the plot of 2018’s Mission: Impossible—Fallout, Cruise proposed a helicopter chase: his character in the films, Ethan Hunt, pursuing a bad guy, played by Henry Cavill, while both of them were aloft. As a rule, in Mission: Impossible, stunts are real: meaning they are performed by the actual actors involved, at least when possible, and when they are being done by Tom Cruise, that means all the time. “He’s the only actor in the world who is actually going to do everything,” Fraser Taggart, the series’s director of photography, told me.

In the Mission: Impossible franchise alone, Cruise has climbed the shiny glass sides of the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building; hung from the side of an A400 military transport plane as it took off; and ridden an actual motorcycle off the edge of an actual Norwegian cliff. He has a commercial pilot license. He is one of 36 people in history to be named an honorary US naval aviator. He can parachute and BASE jump and free dive. But one issue with this particular idea for Fallout was that Cruise, at the time, was not trained as a helicopter pilot. So Cruise and McQuarrie made inquiries, and they were told that at eight hours a day, seven days a week, it would take three months to get Cruise up to speed. Cruise asked: What about the other 16 hours in a day? A month and a half later, he was ready to fly.

The second problem with the idea was that it was so perilous that most countries wouldn’t allow Mission: Impossible to try it within their borders. This is the next conversation McQuarrie and Cruise have. “You’ve got to figure out: Where in the world are we going to shoot this?” McQuarrie said recently. “Well, we’re going to go (a) where Bond isn’t. And (b) where Fast and Furious isn’t. And (c) where Mission has never been. That Venn diagram says: Here’s where you’re shooting. Provided the State Department even allows you to go there.”

With the helicopters, McQuarrie and Cruise tried India first, but “when we told them what we were going to do,” McQuarrie said, “they were like, That’s not happening here.” Finally, they found a friendly government in New Zealand, which said, according to McQuarrie: “Shoot it away from population, and just know if you fly in this glacier and anything happens, there’s no one that can come and get you. You’ll be there forever. They’re going to fly over it and drop a plaque.”

With the location secured, McQuarrie and Cruise got to work. In the sequence they’d planned, Hunt is pursuing a turncoat named Walker, played by Cavill, who is holding the detonator to two nuclear bombs. To film the chase, McQuarrie and his cameraman followed Cruise in a second helicopter. Once in the air, the production followed a strict fuel countdown, meaning they only had so much time in the sky, but the shot was tricky to get right. McQuarrie, over the radio, would give Cruise direction: left pedal, right pedal, until Cruise had flown himself into the frame. “Tom is lining up the helicopter in a camera he can’t see,” McQuarrie recalled. “And I said, ‘That’s your mark. Maintain it.’ The reason it’s always in the frame is because Tom Cruise is both flying the helicopter, looking over his shoulder so the camera can see him, and acting. He’s doing all of that at the same time.”

Simon Pegg, who plays Benji Dunn, a member of the IMF, or Impossible Mission Force, in the series, told me he often feels “a sense of quiet dread” when the production is away attempting one of these sequences. For this one, Pegg said, “I remember when we said goodbye and Tom was going off to do all this stuff with Henry, I said, ‘See you in London. Or maybe not.’ ”

McQuarrie and Cruise have now been working together for nearly two decades, beginning with 2008’s Valkyrie, which McQuarrie wrote and produced, and Cruise starred in. Their partnership has become one of the most productive and lucrative in Hollywood history. And at its center is Mission, as everyone involved calls it—a franchise unlike any other. Based on the TV series from the 1960s, the basic ingredients are almost camp: Each time out, Ethan needs a mission, which will be relayed via a self-destructing device. At some point, someone will wear a latex mask of a face that is not their own. The plots will be baroque; the exposition will come in 40-foot waves.

And yet in its sheer scale, its locations, its dedication to practical effects, and most of all its star, Mission is unmatched. Since McQuarrie came aboard—first as an uncredited screenwriter on the 2011 Mission: Impossible installment Ghost Protocol—the series has also distinguished itself as the rare action franchise about, for lack of a better word, adults. One unofficial rule of Mission is that Ethan Hunt can’t want to do any of the insane things he has to do (ride a motorcycle off a cliff, hang off the side of a plane in midair, etc.), because what normal, mature person would? The primary emotions Hunt seems to feel are guilt, grief, and fear. Just like the rest of us.

To these movies, McQuarrie brings a unique and singular skill set: screenwriter (he won an Oscar, at age 26, for the second Hollywood film he ever wrote, The Usual Suspects), producer, star-handler, director, fixer, stuntman. The producer Jerry Bruckheimer, who worked with McQuarrie on Top Gun: Maverick, told me: “When you look at the town, there are maybe 10 really gifted writers, and maybe 10 really gifted directors, that you can rely on to make something that the audience is going to love.”

McQuarrie is on both lists. And though he tries not to talk about it much, he is also on a third list, as the guy you call when your movie, or your script, isn’t working but the train has left the station and the film is already in production. Sometimes he is credited for this work—as on Edge of Tomorrow or Top Gun: Maverick—and sometimes, as on World War Z, or Rogue One, he is not, which suits him fine.

For the one sequence in Fallout with the helicopters—a scene that would ultimately run around 12 minutes in the film—they shot about 80 hours of footage, Mission’s editor, Eddie Hamilton, told me. Eighty hours. While director and actor hovered in the air. In a canyon where if something went wrong, there would be no escape. “If you want to know why I’m working for Tom for 18 years and other people aren’t,” McQuarrie said, “lots of directors will do that once. They don’t ever want to fucking do that again.”

One day recently, McQuarrie was at home in London, where he lives in a two-story apartment near Hyde Park, racing to finish the latest and possibly last installment of the franchise, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning. (McQuarrie and Cruise both remain coy about whether this is, in fact, the final Mission film.) It was a warm, quiet Saturday, and McQuarrie and Hamilton, his editor, were ensconced in an editing bay on the second floor of the apartment, working through the latest version of the iconic This message will self-destruct brief that more or less begins each Mission movie.

McQuarrie, who is called McQ by his friends, has an emphatic gray sweep of hair, clear-framed glasses, and the distinct and easily legible features of an iPhone emoji. He gestured at the scene on the monitors in front of him and Hamilton. “It’s a giant exposition dump,” he said. “And it’s always excruciating because information is the death of emotion.” Mission movies tend to be dense with plot that even the films’ creators don’t expect the viewer to fully retain. “I’m acutely aware of what I think you are and are not listening to,” McQuarrie told me. “I actually don’t rely on you to pay full attention. I kind of rely on you to drift in and out and get key things.”

McQuarrie began as a screenwriter: worshipful and intensely protective of the words on the page. But in time, and “as I started to understand my job as a director more, I started to understand, you got to let go of the word,” he said. Mission is made for massive global audiences. “Tom and I are talking all the time about the fact that every word you write is a word someone has to read in some part of the world. And that when they’re reading the subtitles, they’re actually not seeing the image. So my images have to tell the story and the words become music.”

McQuarrie had Hamilton cue up the sequence from the beginning and play it for me. “Good evening, Ethan,” intoned Angela Bassett, who plays the president of the United States in the film. Cruise silently watched a monitor as Bassett laid out his character’s history, where Hunt was now, and the stakes of his latest mission. Montages of destruction, nuclear warheads, scenes from past Missions played on the screen. “We’re motivating cuts based on specific words,” McQuarrie explained. “So even if you’ve tuned out, when you hear sacrifice, you might tune in for key words.”

The studio, Paramount, had recently screened Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning for a test audience in Paramus, New Jersey, a location chosen as a literal and cultural midpoint between London and Los Angeles. McQuarrie—unlike many directors, who fear getting feedback that might lead to the studio mandating changes to their film—loves a test screening. “Filmmakers are terrified,” he said, “and rightly so, because not all filmmakers have control of their movie.” But Cruise, who is also the lead producer on the Mission: Impossible franchise, has final cut. So they welcome the information, which they are then able to respond to as they see fit. In this case, audiences had been slightly confused by the mission brief, and so McQuarrie and Hamilton were trying to slow it down and leave them with the desired impression.

After McQuarrie played the sequence once for me, he turned and asked: “What did you take from what you just watched?”

I stammered out what I understood: “Artificial intelligence is trying to use nuclear stockpiles to destroy—”

McQuarrie gently cut me off. “Thanks. That’s all I need you to retain.”

Hamilton cued the scene again and they began going frame by frame, trying to make sure that the images were doing what they could not rely on the words to do. At one point, on a close-up of Cruise, McQuarrie asked Hamilton to pause the scene. “I don’t feel like he’s listening,” McQuarrie said, studying Cruise’s face. “I feel like he’s drifting.”

Hamilton, on another monitor, called up more footage from the scene. “So here now we enter the library of Tom Cruise’s reactions,” McQuarrie said. When this was originally shot, McQuarrie said, Cruise was listening to something else entirely. “It was completely different,” he said. “What we’ll do is, the camera will just drift and Tom will just interact with the camera. And he’ll give you this library of options because he knows full well it’s probably all going to get rewritten.”

Mission scripts are notorious for changing. “Tom likes to feel the film evolve, rather than have a set script and a schedule locked in,” Pegg told me. “It’s a very meta experience,” Erik Jendresen, who cowrote the last two, said. “Because as the screenwriter, me and Tom and Chris, we’re like the IMF team. We’re working under a ticking clock. The stakes couldn’t be any higher. And you’re needing to pivot constantly.” McQuarrie is sensitive to the impression this can leave. “We are not making it up as we go along,” he said. “But we are constantly pushing ourselves to make it better, to make it more immersive, more resonant, more engaging. We don’t trust that just because somebody says these lines on a piece of paper that you’re going to feel those things.”

But a lot can change in the pursuit of a feeling. One of the first things McQuarrie did when he joined the franchise, mid-production, on Ghost Protocol, was rewrite the entire backstory of a character named William Brandt, played by Jeremy Renner. The actor, who had already shot many of his scenes, was initially furious, according to McQuarrie. “Renner was saying, ‘I’m going to free-fall.’ He said to me, ‘But wait, I’ve been playing this whole other character.’ And I said, ‘But I watched all your dailies and all the emotions are the same. What motivated you in that scene doesn’t matter. The emotions you’re communicating are what matters.’ ”

Actors get used to it, McQuarrie said, but the learning curve can be harsh. “Once you start to see the results—Vanessa Kirby on Fallout, Rebecca Ferguson on Rogue Nation, they were all new to the process, and they were all in some way quite understandably destabilized,” McQuarrie said. “But then they see the beginning, middle, and an end. So when they come back for another movie, by the time Vanessa came back for Dead Reckoning, everything changed one day; we had an idea, we rewrote the scene that morning, and I said, ‘Look, I’m sorry, but you’ve got this big thing now.’ And she goes, ‘It’s Mission. I totally get it.’ ” Hayley Atwell, who joined the franchise on Dead Reckoning, told me that the “ever-changing, ever-expanding challenges” of doing things this way used the same muscles that she’d built, not in other movies, but in live theater.

Because of the constantly evolving nature of the Mission scripts, they usually shoot exposition in places they can return to—and not, for instance, on the top of a mountain. “Anytime you have big information scenes, anytime you have exposition, plot, you put them in small rooms, cars, phone booth, you put ’em into a place that you can easily repeat and go back to,” McQuarrie said, “because you’re always going to be changing the plot to accommodate the emotion, rather than the other way around.”

In the edit bay at McQuarrie’s home, Cruise’s face filled the screen in mid close-up, eyes darting, brow furrowing, head bobbing. Cruise is famous on Mission sets for knowing exactly where the frame is: He can indicate the top and bottom of a shot from 30 feet away. “See these very subtle movements he gives,” McQuarrie said. “He’s not doing a big thing. He knows the focal length of that lens and how much it picks up.” When a new actor joins the Mission: Impossible franchise, one of the first things McQuarrie does is sit them down and talk to them about lenses. “Now, when I’m directing Hayley Atwell,” McQuarrie said, “I don’t say, ‘I want your character to feel this, that, and the other thing.’ I point to the lens and say: ‘It’s a 75-millimeter.’ ”

Hamilton and McQuarrie started the scene again from the top. A few minutes later, McQuarrie’s phone rang and the letters TC appeared on the screen. “I’ll be back,” he said.

Before Mission: Impossible, before Tom Cruise, before he won a screenwriting Oscar at 26, McQuarrie was a security guard at a movie theater. “That was my film school,” he said. “I spent four years watching the audience. They were my focus group.” McQuarrie grew up in New Jersey and went to high school with the actor Ethan Hawke, the director Bryan Singer, and the musician James Murphy, of LCD Soundsystem. Because of this, a career in the arts never seemed all that far-fetched. “Bryan was always making movies. James was always making music. When Ethan got cast in Explorers, I was 14, Bryan was 16. James was 12. That made it real—that made it something that could happen. And frankly, it was more real to me than going to college.”

It was Singer who gave McQuarrie his first break in Hollywood when he commissioned McQuarrie to write what would become Singer’s first film, Public Access, in 1993. At the time, McQuarrie, who never did go to college, was doing odd jobs. Public Access screened at the Sundance Film Festival, and won a prize there, but the film never found a distributor. Then McQuarrie came back to Singer with an idea of his own, for a movie called The Usual Suspects, a film told primarily through the interrogation of a small-time criminal named Verbal Kint, played by Kevin Spacey, whose increasingly convoluted tale turns out to be—unbeknownst to his interrogator and the audience—an elaborate fiction.

McQuarrie wrote the first draft of The Usual Suspects in two weeks. The movie has an unorthodox structure; the film opens on the ending of the B-plot, about a group of criminals who are forced together to do a job, and then basically plays in reverse to hide the ending of the A-plot, the true identity of Verbal Kint, which is revealed in the film’s final frames. The end is the beginning is the end. “Suspects is pure structure, pure dialogue,” McQuarrie said. “It’s pure screenplay. Suspects is the rare example of a screenplay that is both readable and shootable. It’s also a script everyone in Hollywood passed on. Everyone. And it’s quite a fluke that the movie ever got made.”

There is an aphorism McQuarrie is fond of: “Writing is pushing a boulder up a mountain. Directing is running down the mountain with the boulder rolling after you.” In the decade after winning the best original screenplay Oscar for The Usual Suspects, he did a lot of pushing. “I thought the Oscar represented power that I could now make something that I wanted to make,” McQuarrie told me. “That wasn’t true. What it meant was I could get paid more money to write the movies they wanted. Nobody wanted my movies.”

McQuarrie had big ambitions and scripts of his own. But what he was actually doing was either joining ailing productions to help fix their scripts, or working in studio development, meaning he was being brought in to come up with ideas and treatments for projects conceived of by executives at various studios and production companies. In practice, very little of it ever saw the light of day. “I spent 10 years writing movies that were never going to get made,” McQuarrie said, “to finance the development of my scripts, which no one would ever make.”

In 2000, frustrated with his inability to make something of his own, McQuarrie wrote another crime film, The Way of the Gun, with plans to direct it, with Ryan Phillipe and Suspects actor Benicio Del Toro as his two leads. The Way of the Gun—about two bumbling criminals who abduct a surrogate mother and hold her and her unborn child for ransom—was deliberately antagonistic: It broke all the rules that McQuarrie had been forced to follow about sympathetic characters, about plot development, and about taking care of the audience, and when it came out, audiences summarily rejected it. “I directed an eight-and-a-half-million-dollar movie that I didn’t want to make,” McQuarrie said. “But it was my only opportunity. And I made it with both middle fingers extended, and the movie didn’t work, and the business said, ‘Thanks very much, that was your shot.’ And I was in director jail, and that’s where I remained for 12 years.”

While in director jail, McQuarrie worked on many movies, and was fired off of many movies. Screenwriting is a brutal business. “Writers, consciously or unconsciously, we are held in contempt,” McQuarrie said. “The movie can’t happen without us, but we are not why a movie happens. We’re not stars, we’re not directors. We’re the nerd at the party and we have the car. You’re not getting home without us. That breeds a kind of resentment.” McQuarrie even went so far as to quit the business at one point. But he was also developing a reputation as a troubleshooter and a fixer. (McQuarrie was once asked to write a script about the making of the Transcontinental Railroad, but for cheap, meaning, somehow, it would need to be shot inside, without showing all that much of the actual railroad—“And I figured out how to do it.”) McQuarrie, Pegg told me, “thrives with a problem. I think McQ loves a crisis more than he loves a blank page.”

What McQuarrie saw during his years in the wilderness were men and women—screenwriters, directors, producers—under duress, making unwise decisions, particularly on movies on the scale of Mission: Impossible. “A lot of these big tentpole movies,” McQuarrie told me, “how they work is you take a director who’s only made smaller films but has had success, and somebody does the math that says, ‘Hey, that person made a $5 million movie that made $50 million, now let’s give them $200 and they’ll make a billion.’ That’s actually not how it works. Because that person is leaping from an independent mindset into a massive commercial mindset without having had any education of the kind of movie they have to make at that number.”

McQuarrie began to notice patterns. Mistakes that were made, over and over again. Studios soon recognized this particular talent. Once, McQuarrie told me, in his capacity as a movie ER doctor, he was parachuted in on two separate films in distress, on which two totally different filmmakers both had an Apocalypse Now poster in their office. “And I said, ‘Let me tell you how to make Apocalypse Now. Let me help you because it’s so simple. First, make The Godfather, then make The Conversation, then make The Godfather Part II. Then take all of your personal capital and all of your professional capital and gamble that and your marriage and the life of your leading man and your sanity on a movie about a war that nobody wants to remember. And then spend years shooting it and put it in cinemas and no one will come and it will take decades before people recognize what it is. That’s how you make Apocalypse. Now let me tell you something: You’re not making Apocalypse Now.’ ”

(ARC NOTE: jesus fucking christ)

What McQuarrie would try to do instead was identify whatever the filmmaker had done that was unique to the genre or the franchise they were working on. Something that was their signature. And he would say, “ ‘That’s your stamp. Now you’ve got to make a billion dollars. Come with me if you want to live.’ And in both cases the directors did not listen. And in both cases the films were taken away from them. Other filmmakers came in and finished those films.” McQuarrie didn’t blame the directors. He blamed the system. “The problem is that they were given an opportunity, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” McQuarrie said, “before anybody sat down and educated them and said, ‘Listen, before you do this, here’s the reality of making movies like this. Are you sure you want to do it?’ And that’s what doesn’t happen. There’s not a system that educates those people.’ ”

McQuarrie knows this because he was one of those people. What changed that fact—and what got McQuarrie out of director jail and development hell—was Tom Cruise. McQuarrie and Cruise met in 2006, as Cruise was circling the lead role in Valkyrie, a movie about the failed assassination of Hitler that McQuarrie had written with the hope of being able to direct it. But Hollywood can be unforgiving. Singer, McQuarrie’s old classmate and collaborator, was also interested in directing the film, and so Singer—a more proven and financially successful filmmaker—became the director instead. (Singer has been accused of sexual assault in multiple lawsuits that were either settled or dismissed, and has maintained his innocence. He hasn’t directed a film since 2018. “My relationship with Bryan is pretty complex,” McQuarrie told me.) Cruise, according to McQuarrie, had two stipulations regarding Valkyrie. The first was that they spend more money on the film. “He said, ‘Guys, you’re blowing up the 10th Panzer division in the first 10 minutes of your movie; you need more money.’ And I said, ‘What’s the compromise?’ And Tom said, ‘There is no compromise. We’re making this movie. We’re going to make it for the widest audience possible. We’re going to make the most emotional version of this movie that we can.’ ”

The second stipulation was that McQuarrie, whom Cruise was growing to like and trust, join Valkyrie as a producer—a job he’d never done before. McQuarrie said yes anyway. “I went to work every day fully expecting to be fired,” he told me. He and Cruise are still working together 18 years later. “And it’s very important to point out that in between The Usual Suspects in ’95 and Valkyrie in 2006, a stack of movies this high, projects that I was called into rewrite, movies that never got made, not one piece of wisdom or applicable knowledge ever came from anyone in any of those meetings, ever,” McQuarrie said. “The truth of the matter is, other than what I brought to storytelling when I wrote The Usual Suspects, everything I learned about movies I learned by making movies with Tom.”

After Valkyrie, McQuarrie’s career was reborn. Suddenly, he was being brought on to write or help fix movies that were actually being produced: Edge of Tomorrow, World War Z, The Tourist, Rogue One, Top Gun: Maverick. In 2012, he directed Cruise in Jack Reacher; three years later, on the heels of doing the uncredited rewrite on Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol, McQuarrie became the director of 2015’s Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, after Cruise called the head of the studio and said that’s who he wanted in the chair.

Jerry Bruckheimer told me the secret to McQuarrie’s success in the latter half of his career was simple: “It’s because he loves it. He loves entertaining audiences. He loves big movies. You’ve got to love it. You bring in certain writers who want to write a big movie but don’t really care about it, you know, or understand what it is. They’re guessing.” McQuarrie is not guessing.

In London, over dinner, I asked McQuarrie to walk me through the making of a single stunt in the newest Mission: Impossible film. In Final Reckoning there is a sequence in which Cruise hangs from the side of a biplane, before leaping onto a second biplane, all in midair. An image from this scene is on the poster; pieces of it are in the film’s trailer. (This is the core of the Mission appeal: The thing the filmmakers care about most is the thing audiences care about most too. The movie is the marketing; the marketing is the movie.) The practice of going out onto the wing of a flying airplane is called wing walking, and that is who Cruise went to first: some wing walkers. “They said, ‘What do you want to do?’ ” McQuarrie told me. “And Tom said, ‘I want to be between the wings of the plane holding on to the tension wires, and I want to be in zero G between the wings.’ And wing walkers who do this for living said, ‘That will never happen. You can never do that.’ And Tom said, ‘All right, well, thank you very much for your time.’ ” And he and McQuarrie went and found some different wing walkers.

During the reporting of this article, I heard stories like this a lot. (Okay, one more: During the shooting of Fallout, McQuarrie told me, Cruise broke his ankle. “A doctor, a sports specialist, said to Tom, ‘It will be six months before you can walk. It’ll be nine months before you can run, if you ever run again.’ And Tom’s response was, ‘I don’t have time for that. I’ve got six weeks.’ And six weeks later, he was climbing Pulpit Rock on a shattered talus bone.”) If you’re wondering what Cruise has to say about all this, so was I. In time, I was invited to ask him a few questions via email. What makes Mission: Impossible…Mission: Impossible?, I wrote to him. Is it the process? The protagonist? The controlled chaos of the production? The stunts? The locations? The scale? “Dear Zach,” Cruise wrote back. “I don’t quite know how to answer this. Maybe it is all of these things and more.”

Mary Boulding, Mission’s first assistant director, told me Cruise has a saying on set: “Don’t be careful. Be competent.” So what the production did next, for the biplane sequence, was start building the stunt, piece by piece. They started with: Just get Cruise out on the wing. How far out could he get? How many G’s could he take once he was out there? “Now there’s a moment,” McQuarrie said, “where Tom’s laying across a cable and the plane goes into positive G’s, which means your whole body is being forced earthward. He’s laying on top of a cable, which means his organs are being pushed past either side of the cable. And if you go too far, the cable’s just going to cut you in half.”

It was at this point that I asked McQuarrie where his heart and mind typically were while shooting sequences like this one. During the A400 stunt, years ago, McQuarrie would sometimes black out from the stress as they waited to attempt it, he said. “If you want the summary, you’re the frog in the pan of water,” he told me. “You don’t realize the water’s boiling until you’re in it and it’s boiling. At which point you better figure out how to survive in boiling water or somebody’s going to be eating your legs and you develop a very thick skin.”

They decided to shoot the biplane sequence in South Africa, just after the rainy season there, because the land would be abundantly green. That also meant it was cold. “If the temperature changes two degrees Celsius, Tom will be hypothermic after 12 minutes on the wing,” McQuarrie said. Cruise had no radio in his ear. So he and McQuarrie, who shot the sequence from a helicopter that hovered so close to the plane that McQuarrie could read Cruise’s airspeed in the cockpit, devised a set of hand signals. “The wind is hitting him not only at the speed that the plane is flying but the wind coming off the propeller. It’s hitting him at well over a hundred-plus miles an hour.” At that speed, air is actually hard to breathe. “There were times when Tom would have to lay down on the wing to rest between takes,” McQuarrie said. “You can’t tell if he’s conscious or not. And unless Tom pats the top of his head”—their hand signal for stop —“it’s like, keep rolling.”

Cruise’s plane was also flying frighteningly low, McQuarrie said. “A plane flying at altitude, safely, is the most boring thing imaginable. You watch Top Gun: Maverick, the reason why we’re flying in that canyon, the reason why Star Wars flies in that canyon—planes are only cool when they’re flying low. No matter how fast they’re flying. Now in Top Gun, they were flying, at times, 50, 60 feet off the deck. When you’re in a biplane that can’t go Mach 2, you’ve got to go lower. The margin of error is zero. The power on these planes, they’re at full throttle, which means if there’s a downdraft or a thermal, there is no more oomph to get up. You go down and that’s it. I’m directly behind it. He goes down, I go down. Our crew goes down.”

In this way, over the years, McQuarrie has become kind of a stuntman too. Where Cruise goes, McQuarrie goes. Even in midair. “There is not enough room in this article for me to fully communicate and give justice to all of the things that Christopher McQuarrie is, does, and has done,” Cruise told me.

Despite the danger, McQuarrie seems to love the chaos of the life he’s fallen into. The bad luck, the broken bones, the close calls. “It’s weird how the content of these things mirrors the making of them,” Jendresen, the screenwriter, told me. McQuarrie encouraged me to rewatch the last scene of Mission: Impossible—Fallout, which they’d shot on film. Cruise’s Ethan Hunt, after his helicopter ordeal, awakens to find all his friends around his hospital bed. His whole body is in pain. “Don’t make me laugh,” he says, and then there is a flash of light, and the screen goes dark. Cue the Mission theme.

But that flash was not planned, McQuarrie told me. What you’re seeing is the most basic accident you can see on a film set. “There is nothing more Mission,” McQuarrie said, grinning, “than the camera rolling out of film on the last shot.”

(((THANK YOU ZACK BARON FOR THE BEST FUCKING PROFILE EVER HOLY SHIT))

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prospero and Miranda (from William Shakespeare's The Tempest, Act I Scene II

Artist: Henry Thomson RA (English, 1773-1843)

Date: c. 1804-1805

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: National Trust Collections, London, United Kingdom

Description

Prospero stands in the centre, in a cave, his back to the viewer, but towards Miranda on his right. Ferdinand approaches them from the beach with signs of a shipwreck behind whilst the spirit Ariel hovers above in the sky, playing music. It depicts the second scene in the first Act of the play after the daughter has declared: 'If by your art, my dearest father, you have / Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them.'

#literary art#painting#the tempest#oil painting#artwork#fine art#oil on canvas#english culture#english art#literary characters#prospero#miranda#ferdinand#beach#cave#william shakespeare#storm#william shakespeare's play#literature#shipwreck#spirit ariel#music#drapery#european art#henry thomson#english painter#19th century painting#royal trust collections

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently, I did a re-read of the AF series, and I am working through some thoughts I have on the Fowls and what allowed them to maintain power -- especially in the sense of being landed -- in Ireland after arriving during the Norman conquest in the 12th century.

Colfer establishes that Hugo de Folé and Virgil Butler arrived in Ireland during the first Norman crusades in the 12th century (1169).

“The first record of this unusual arrangement [between the Fowls and Butlers] was when Virgil Butler had been contracted as servant, bodyguard, and cook to Lord Hugo de Folé for one of the first great Norman crusades.” From: Artemis Fowl. By Eoin Colfer.

At once, these origins of the Fowls would make them ambiguously part of the Old English, a term from the modern period (post-1600) used to describe the descendants of the first Anglo-Norman conquerors who largely inhabited the Pale (Dublin and surrounding areas) and surrounding towns. Hugo de Folé and Virgil Butler would have likely been Catholic.

However, the origins of Fowl Manor complicate this.

The original Fowl castle had been built by Aodhán Fowl in the fifteenth century overlooking low-lying country on all sides. A tactic borrowed from the Normans. From: The Arctic Incident. By Eoin Colfer

In the 15th (c. 1401-1500) century, Aodhán Fowl acquired land for Fowl Manor in the Pale (Dublin and its surrounding areas); the estate has remained in the Fowls' possession ever since, which is important to note.

The Fowls' historical proximity to the Pale likely was what allowed them to maintain power over the centuries.

Between the 12th and 16th centuries, the Lordship of Ireland (1177-1542) placed swaths of Ireland under the control of Anglo-Norman lords loyal to the King of England.

However, by the 14th century (1300s), English rule of Ireland beyond the Pale (Dublin and its surrounding areas) was weakening. Beyond the Pale, (Catholic) Hiberno-Norman lords' fiefdoms had a degree of independence from the English, often adopting elements of Gaelic language and culture.

This changes around the 16th century with the Protestant Reformation and the Tudor conquest of Ireland. In 1536, Henry VIII of England decided to reconquer Ireland and bring it under crown control. Charles II, Henry VII's son, made the re-established Church of England even more explicitly Protestant.

Between the 16th and 17th centuries (c.1550s-1620s), Irish land was transferred to a new wave of (Protestant) settlers from Great Britain and Scotland to strengthen the Crown's weakening control over Ireland and Anglicize (and thus "civilize") the island; the land transfer was facilitated through the creation of plantations, such as the plantation of Ulster.

The Old English, which would have included descendants of de Folé and Virgil Butler, were supplanted by the New English, the Protestant landowners introduced by the Tudors in a number of ventures at plantations.

It is important to note the historical nuance that:

There was no equivalent in Ireland to the English Test Act of 1672, and there were plenty of precedents for exemptions to the Act of Supremacy. The legal position of Irish Catholics was, in many practical respects, better than that of English Catholics; many fines and penalties fell into abeyance under Charles [II], and the Catholic hierarchy co-operated openly with the Dublin administration. From James's [James VI and I] accession, the Church's position was obviously improved; priests emerged into the public eye and were allowed salaries, though they were not as yet endowed. Protestant superiority remained, in many areas, axiomatic; Catholics continued to occupy a curiously edgy position of formal inferiority combined with tacit toleration. But the ambiguities of their situation reflected the logic of local conditions just as much as the shifts in central policy. [...] But the 'Test clause in the 1704 [Popery] Act, obliging holders of public office to take sacraments according to the usage of the Church of Ireland, gradually excluded Presbyterians from town corporations even in Ulster. Despite the regium donum and the Toleration Act, their equivocal relationship with the civil power remained, and would provide a key theme in the radicalization of the Irish political world after 1780, when the threat of Catholic disaffection apparently receded. [From: Modern Ireland, 1600–1972. By R.F. Foster]

Still, the Popery Act would have had consequences for the historical Fowls and Butlers as Old English families. Beyond the Test clause in the Popery Act, it also limited Catholics' ability to buy/lease land, as well as limited inheritance from a Catholic to be by gavelkind i.e., divided equally, and thus shrinking with each generation, the estate between all sons, rather than according to Primogeniture.

It begs the question of how Fowl Manor remained in the hands of the family, rather than becoming the estate of a member of the New English.

As anti-Catholic sentiment was largely grounded in the political context of loyalty to the Crown (as opposed to the Pope), certain members of the Old English gentry could have (and did!) find ways to join the wave of the Protestant Ascendancy.

"The Anglo-Ireland of the day in fact encompassed sizable middle and lower classes -- a heterogeneity that Foster finds "exemplified by that quintessential Ascendancy institution, Trinity College: defined by Anglicanism but containing sons of peers, of shoemakers, of distillers, of butchers, of surgeons, and of builders" (Foster 1989, 173). And not all the "Anglo-Irish" were, strictly speaking, "Anglo." Early in Bowen's Court, Bowen's historical account of her family's Cork home, we learn that "Bowen" derives from the Welsh "ab Owen" or "ap Owen" (Bowen 1942a, 33). Other Anglo-Irish men and women traced their ancestry to the Old English and to Catholics who converted to Protestantism in order to reap the accompanying social, political and material rewards. Violet Martin (better known as Martin Ross) descended from the Old English Martins of Ross, who had owned land in Galway and had converted to Protestantism in the eighteenth century (McMahon 1968, 123). As Thomas Flanagan concludes, "there were many ways of being Anglo-Irish" (Flanagan 1966, 59). So what, then, defined Anglo-Irishness? In [R.F. ] Foster's view, it was Anglicanism. Anglicanism "defined a social elite, professional as well as landed, whose descent could be Norman, Old English, Cromwellian or even (in a very few cases) ancient Gaelic. Anglicanism conferred exclusivity, in Ireland as in contemporary England; and exclusivity defined the [Protestant] Ascendancy, not ethnic origin" From: An Anarchy in the Mind And in the Heart: Narrating Anglo-Ireland. By Ellen M. Wolff

And what do we find out in the first book of Artemis Fowl?

"Beside [Angeline] was a facsimile of [Artemis'] father, constructed from the morning suit he'd worn on that glorious day in Christchurch Cathedral fourteen years ago." From: Artemis Fowl. By Eoin Colfer

Christchurch Cathedral (in Dublin) is Anglican in denomination!

I just think it is so cool that across a few sentences from Artemis Fowl and The Arctic Incident, it is possible to situate the Fowl family within a semi-realistic history of Ireland.

#artemis fowl#long post#sources for this are largely rf foster's modern ireland 1600-1972#and ruth canning's The Old English in Early Modern Ireland#also I am not an expert when it comes to irish history! just an enthusiast/hobby researcher

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Last Updated: 2024-02-08

Disclaimer: I am not the author of these stories, just sharing my favourite Henry!Holmes stories. Find the authors' links below. If you want your work removed, message me privately.

Legend: 〔E〕 ⇢ Erotic/Steamy | 〔F〕 ⇢ Fluff | 〔A〕 ⇢ Angst/Hurt 〔M〕 ⇢ Minor Angst/Hurt | 〔C〕 ⇢ Comfort | ♥︎ ⇢ Established Relationship | 𑁍 ⇢ Pregnancy/Children | 🚫 ⇢ Content Warning

✑ Love-Performing Night | Prt. II | Prt. III by st-juliet • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 •

Summary: "…An actress at Covent Garden Theatre and neighbour to a certain eccentric detective, [you're] equal parts flustered and delighted when [Sherlock] arrives [backstage]."

✑ Utmost Merit by st-juliet • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 •

Summary: "Sherlock presents [you] with a most unconventional proposal."

✑ When We Were Young by youvebeenlivingfictional • 〔F᜶A〕 •

Summary: "You were an only child, a girl (which had disappointed your parents), and while you loved to learn, you hated your governess. You were curious, a little wild, and lonely."

✑ A Work Proposition by zodiyack • 〔F〕 •

Summary: After witnessing your, another detective, interaction with Sherlock, Enola sees a perfect opportunity to play Cupid

✑ An Absolute Mess by youvebeenlivingfictional • 〔F〕 •

Summary: "Your Aunt [sent] you a, moderately frantic, letter [requesting] help [tidying up after one of her more peculiar tenants]."

✑ Don't You Remember│Prt. II by iguana-eyanna • 〔A〕 •

Summary: "Sherlock is hired by an old flame that claims that a family heirloom has been stolen, but he has suspicions of why he was hired in the first place."

✑ Enigma by iguana-eyanna • 〔A᜶F〕 •

Summary: "When Sherlock comes at your door seeking help, you two realize you can't deny the pull you have on each other."

✑ Exactly What You Need by delicate-moon-princess • 18+ • 〔E〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "It seems Sherlock understands your needs better than you do."

✑ Experiment, the│Prt. II by maximsdeadwife • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "When you married Sherlock, you discovered a side to him that you would never have expected. A side that was only for you."

✑ Family Man by buckybarnesthehotshot • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ • 𑁍 •

Summary: "In which [Sherlock], along with other ladies of high society, learns his wife is with child"

✑ Fresh Air and Exercise by daydreaming-in-letters • 18+ • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "Sherlock may [refuse] to join, [you] for an afternoon walk, but that doesn't mean he has to pass up on the much needed exercise altogether."

✑ Give It Up by theplaid-wearingmoose • 18+ • 〔E〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "When Enola had told him he needed to learn to give up control sometimes, he was fairly certain this is not what she had meant."

✑ Hair by buckybarnesthehotshot • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ If Only You Would Know by espinosaurusrexex • 〔A᜶C〕 •

Summary: "You and Sherlock are in love; Enola is sure of it. [However,] she is forced to watch you tiptoe around the topic for an eternity. So when the opportunity arises, and Sherlock is forced to confront his feelings towards you, she does not hesitate."

✑ Jigsaw by andsheloved • 〔F᜶A〕 •

Summary: "As you wonder what it would be like for him to return your affections, Sherlock finally understands what he would sacrifice to fit within your world."

✑ Most Beautiful Riddle, the by espinosaurusrexex • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "Sherlock Holmes... never entertained the idea of marriage. That was, until [you] came along and turned his world upside down... After a year of... love and happiness, he is finally ready to ask the question. There is just one problem: How is he ever to make the proposal worthy of his one true love?"

✑ On Subjects of the Heart│Prt. II by andsheloved • 〔A〕 •

Summary: "Sherlock has a good head on his shoulders; he's straightforward, critical, and almost painfully logical, so why have you had his mind swimming with thoughts that are anything but?"

✑ Only Women, the by writingfortoomanyfandoms • 〔F᜶A〕 •

Summary: {…}

✑ Only You by thisisawonderfulusername • 〔A〕 • ♥︎ • 𑁍 •

Summary: "After becoming pregnant, you notice that Sherlock has been distancing himself. he finally returns home after at least a month of being gone."

✑ Propriety by andsheloved • 〔F᜶C〕 •

Summary: "Sherlock was sure his heart stopped when he saw you lying in the hospital bed, all because of him. He has to take care of you. He has to… who cares if the only way he can be in the room… is to tell them he's your husband? Certainly not him. Absolutely not."

✑ Pubs & Pebbles by youvebeenlivingfictional • 〔E᜶F〕 •

Summary: {…}

✑ Pulse Point by st-juliet • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "To help him relax in the midst of a trying case, Reader exploits Sherlock’s only vulnerability."

✑ Red Carnation by shotgunbunny • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "Sherlock's jealousy shines through and makes you annoyed, [to make amends he] shows you how he's loved you all these years."

✑ Riotous by st-juliet • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "A wealthy, titled, chaste young lady such as [yourself] should most definite… in attendance at a secret back-room boxing match… Neither should a refined [and] proper… detective. [Yet,] here you [both] are, two weeks away from your wedding no less…"

✑ Run Away by multific • 〔F᜶A〕 • ♡ •

✑ Smallest Joys by inknopewetrust • 〔F᜶C〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "The tree in the Holmes' backyard [is] a place of… peace and laughter… and a moment arises for it to be a place of forgiveness and love as well."

✑ Simple Things by dyns33 • 16+ • 〔E〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Sir Snuggles by thisisawonderfulusername • 〔F〕 • 𑁍 •

Summary: "Your niece [enlists] the help of Sherlock Holmes to find her teddy bear."

✑ Surely Not Love by youvebeenlivingfictional • 〔F〕 •

✑ Taste of Home by delicate-moon-princess • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "You wake up next to, [your husband], Sherlock... after months of being apart. It never [feels] like home when [he's] gone... now, [he's finally back] to fill the void in your heart."

✑ Teacups and Telegrams by theladyofmanyfandomsfanfiction • 〔F〕 •

Summary: "Your morning was normal until you received a telegram from your friend Sherlock Holmes with a simple request: help him find Enola."

✑ Thursday 4pm by starkleila • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ • 𑁍 •

Summary: "Enola deduces something about you before Sherlock."

✑ Waiting Game, the by ithebookhorder • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "Sherlock comforts [you after a] heartbreak…and opens a door for a happier future."

✑ We Meet Again by maarijaaa • 18+ • 〔F᜶A〕 • ♡ •

Summary: "After your father stepped down as a detective, you decided to take over... [you did not expect] a letter standing on your front porch from a person you wanted to leave in the past…"

✑ We'll Be Alright by love-strawberry • 〔F᜶A〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "In which [you] fight but there's no doubt that [you'll] end up alright."

✑ What It Would Be Like to Love You by cruelfvkingsummer • 〔F᜶M〕 •

Summary: "What happens when a genius and a hopeless romantic are arranged to be wed?"

✑ What They Didn't Know was Missing by iguana-eyanna • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ • 𑁍 •

Summary: "It's hard to [coming to] terms [with] becoming a mother, but Sherlock [will] remind you [daily] that you are worthy of being one to your child."

✑ Women, the by dyns33 • 〔M᜶C〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: After learning of her sister-in-law's jealousy towards Miss Adler, Enola is determined to make her brother realize how he's hurting his wife.

✑ Words Cannot Express by espinosaurusrexex • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "In which [you] and Sherlock have a forever crush on each other."

✑ Your Only Warning by st-juliet • 16+ • 〔E᜶M〕 • ♥︎ •

Summary: "Alone in the library with his betrothed,... Sherlock fights to remain a gentleman…with limited success."

✑ Always Here by andsheloved • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ At the End of Each Case by writingfortoomanyfandoms • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Autumn Morning by henryofsteel • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Blue by fivequartersoftheorange • 18+ • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Convince Me by youvebeenlivingfictional • 〔F〕 •

✑ Darling by runawayolives • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ En Garde by ithebookhorder • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Game is Afoot Indeed, the by marvelousmando • 〔F〕 •

✑ Governess, the by ladyfloriographist • 〔E〕 •

✑ Hold My Hand by make-me-imagine • 〔F〕 •

✑ Investigating Love by shotgunbunny • 〔F〕 •

✑ Lovely Neighbour, the by dyns33 • 〔F〕 •

✑ Midnight Activities by loganbcrnes • 18+ • 〔E〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Oh What a Fool You Are by germangirl321 • 〔M᜶C〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Perhaps Not by writingfortoomanyfandoms • 〔F〕 •

✑ Playing Games by dyns33 • 〔F᜶A〕 •

✑ Ready Now by st-juliet • 〔C〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Sister's Roomate by writingfortoomanyfandoms • 〔F〕 •

✑ Talking in Your Sleep by writingfortoomanyfandoms • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Waiting on Your Husband | Prt. II by dearfandomdiary • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Wild Violet by st-juliet • 18+ • 〔E᜶F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Being Sherlock's Wife in Enola Holmes Would Include… | Prt. II by starkleila • 〔F〕 • ♥︎ •

✑ Fancying Sherlock Would Include... by hobbit-historian • 〔F〕 •

See Also: Navigation || Henry!Sherlock Holmes Master Index

Authors: @andsheloved || @buckybarnesthehotshot || @cruelfvkingsummer || @daydreaming-in-letters || @dearfandomdiary || @delicate-moon-princess || @dyns33 || @espinosaurusrexex || @fivequartersoftheorange || @germangirl321 || @henryofsteel || @hobbit-historian || @iguana-eyanna || @inknopewetrust || @ithebookhoarder || @ladyfloriographist || @loganbcrnes || @love-strawberry || @maaarijaaa || @make-me-imagine || @marvelousmando || @maximsdeadwife || @multific || @runawayolives || @shotgunbunny || @starkleila || @st-juliet || @theladyofmanyfandomsfanfiction || @theplaid-wearingmoose || @thisisawonderfulusername || @writingfortoomanyfandoms || @youvebeenlivingfictional || @zodiyack ||

#Henry!Holmes x Reader#Henry!Holmes x Y/N#Henry!Holmes x You#Henry!Sherlock x Reader#Henry!Sherlock x Y/N#Henry!Sherlock x You#Henry Cavill x Reader#Henry Cavill x Y/N#Henry Cavill x You#Enola Holmes Fanfiction#Enola Holmes Fanfic#Henry Cavill Fanfiction#Henry Cavill Fanfic

605 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosamund Clifford , Mistress of Henry II [18th c.] British (English) School Ferens Art Gallery

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

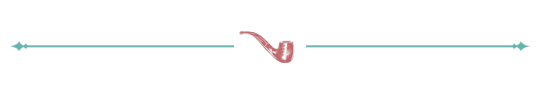

Matilda of Tuscany

Matilda of Canossa (c. 1046-1115), the Countess of Tuscany (r. 1055-1115) and Vice-Queen of Italy (r. 1111-1115), was the final head of the noble House of Canossa following the deaths of her father in 1052 and her elder brother in 1055. One of the most influential women of medieval Europe, Matilda is noted for her military and political prowess, her ceaseless patronage of the Christian Church, and her defense of Papal authority. Though a vassal of the Holy Roman Empire, Matilda often acted independently. Her conflict with the imperial state included a nearly lifelong military conflict with Henry IV (1050-1106), the German king (r. 1056-1105) and Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1084-1105).

Most of Matilda’s holdings, including her family’s ancestral castle of Canossa, were located across the plains of the Po Valley in northern Italy, an invaluable intersection of trade routes between the Italian peninsula and Italy’s northern neighbors beyond the Alps. In the southern part of Matilda domain beyond the Po Valley was the Duchy of Tuscany, rugged with mountains in its north, rural hills throughout, and vital roads connecting to Rome. With these possessions and an impenetrable alliance with the Christian Church, she became an influential political figure in medieval Europe. Matilda was often referred to as the Great Countess (la Gran Contessa) by contemporaries and scholars, despite this title being lesser than her truer title, that of the Margravine of Tuscany. Although she was considered the rightful heir to her father’s northern Italian holdings, Henry IV never recognized her claims to the lands within the Holy Roman Empire.

Early Life

Matilda was a descendent of the House of Canossa, a noble family established by her great-grandfather Atto Adalbert of Lucca (d. 988), a 10th-century Lombard military leader from Lucca and vassal to the German kings of Italy. Adalbert and his son Boniface expanded their domain and by 1027, the Canossa family's influence encompassed the counties of Brescia, Cremona, Ferrara, Mantua, Modena, Reggio Emilia, and Veneto. In 1027, Roman Emperor Conrad II (r. 1027-1039) transferred the Duchy of Tuscany to Boniface. As Schevill explained,

With Tuscany added to his strength ... Boniface completely dominated central and northern Italy; and since he clung to his superior, the emperor, with more consistency than was usual among feudal magnates, he served as the main pivot of the imperial power in Italy in his day. (53)

In 1037, Boniface married Beatrice of Lorraine (c. 1020-1076), a direct descendent of Charlemagne and Conrad’s niece by way of marriage. Matilda was born to Boniface and Beatrice in 1046 after two older siblings: Frederick and Beatrice. Matilda’s place of birth has been disputed, though scholars have suggested Canossa, Lucca, and Mantua. On 6 May 1052, when Matilda was six years old, Boniface was killed by an unknown assailant, likely by an assassin of Holy Roman Emperor Henry III (r. 1046-1056). Frederick inherited the feudal land of their father while Beatrice governed on his behalf. Matilda’s older sister died shortly after Boniface in 1053, though details are unclear.

In 1054, Beatrice married her first cousin Duke Godfrey the Bearded of Upper Lorraine, while Matilda was betrothed to the elder Godfrey’s son, Godfrey the Hunchback. Although Pope Leo IX, another cousin of Beatrice, gave them his blessing to marry, neither received consent from their king, Henry III.

Using the marital transgression to his advantage in 1055, Henry imprisoned Beatrice and Matilda at Bodfeld in current-day central Germany and claimed their holdings. Frederick, the only son and heir to Boniface, is thought to have died in 1055, leaving the young Matilda as the sole child of the Canossa dominion. Since women did not have the right to own, govern, or inherit feudal land under imperial law, Frederick’s death made not Matilda but Henry III, Beatrice’s closest adult male kin, the rightful heir to Boniface.

The mother and daughter remained in captivity until Henry III suddenly died in October 1056. Until the adulthood of Henry’s heir, Henry IV, the widowed Queen Agnes acted as regent to the young king. In exchange for a renewed oath of fealty from Godfrey the Bearded, Agnes freed her deceased husband’s prisoners and authorized the marriage of Godfrey and Beatrice. Godfrey, therefore, controlled the Canossa holdings and established his court in the Duchy of Tuscany, where the family returned by the spring of 1057. Information concerning Matilda’s youth beyond these events is terse.

The marriage of Beatrice to Godfrey the Bearded remained intact despite Henry III’s efforts and was recognized by Queen Agnes. Matilda’s inheritance in Italy was passed to the governance of her stepfather, who, in 1064, also inherited the Duchy of Upper Lorraine. With her role as heir forfeited to her stepfather, Matilda abandoned her ancestral home in Italy in favor of her husband’s in Upper Lorraine. The betrothal to her cousin Godfrey the Hunchback was not fulfilled by marriage until May 1069 when Matilda was 23 years old and the elder Godfrey was expected to die after falling ill. Upon his death, the titles in Italy and Lorraine were transferred to the younger Godfrey. The only child of Matilda by Godfrey was Beatrice, named after her grandmother, but she died shortly after birth, sometime between May and August 1071.

Continue reading...

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the anniversary of the Pulse shooting, which took the lives of 49 people, most of whom were Latine and LGBTQIA+, as Pulse is a gay nightclub that was hosting a "Latin Night" on that evening. Take a moment today to reflect on and honor the lives of the victims. Stanley Almodovar III, 23 Amanda Alvear, 25 Oscar A. Aracena-Montero, 26 Rodolfo Ayala-Ayala, 33 Alejandro Barrios Martinez, 21 Martin Benitez Torres, 33 Antonio D. Brown, 30 Darryl R. Burt II, 29 Jonathan A. Camuy Vega, 24 Angel L. Candelario-Padro, 28 Simon A. Carrillo Fernandez, 31 Juan Chavez-Martinez, 25 Luis D. Conde, 39 Cory J. Connell, 21 Tevin E. Crosby, 25 Franky J. Dejesus Velazquez, 50 Deonka D. Drayton, 32 Mercedez M. Flores, 26 Peter O. Gonzalez-Cruz, 22 Juan R. Guerrero, 22 Paul T. Henry, 41 Frank Hernandez, 27 Miguel A. Honorato, 30 Javier Jorge-Reyes, 40 Jason B. Josaphat, 19 Eddie J. Justice, 30 Anthony L. Laureano Disla, 25 Christopher A. Leinonen, 32 Brenda L. Marquez McCool, 49 Jean C. Mendez Perez, 35 Akyra Monet Murray, 18 Kimberly Morris, 37 Jean C. Nieves Rodriguez, 27 Luis O. Ocasio-Capo, 20 Geraldo A. Ortiz-Jimenez, 25 Eric Ivan Ortiz-Rivera, 36 Joel Rayon Paniagua, 32 Enrique L. Rios Jr., 25 Juan P. Rivera Velazquez, 37 Yilmary Rodriguez Solivan, 24 Christopher J. Sanfeliz, 24 Xavier Emmanuel Serrano Rosado, 35 Gilberto Ramon Silva Menendez, 25 Edward Sotomayor Jr., 34 Shane E. Tomlinson, 33 Leroy Valentin Fernandez, 25 Luis S. Vielma, 22 Luis Daniel Wilson-Leon, 37 Jerald A. Wright, 31 (from

https://www.orlando.gov/Initiatives/Pulse-Tragedy/Updates-and-Information/Victims%E2%80%99-Names

)

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don Miguel de Castro, Emissary of Congo

Artist: Jaspar Beckx (Dutch, 1547-1647)

Date: c. 1643

Medium: Oil on panel

Collection: Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, Denmark

Portrait of Dom Miguel de Castro, Emissary of Congo

The painting is a portrait of Dom Miguel de Castro, a cousin of the Count of Sonho, who was sent as an envoy to the Dutch Republic to ask the Dutch stadtholder for mediation in a conflict the count had with King Garcia II of Kongo. The Dutch West India Company had conquered Loango-Angola in 1641 from the Portuguese, and they had heavily relied on the assistance of the Count of Sonho.

Dom Miguel de Castro travelled with a few servants to the Dutch Republic via Dutch Brazil, where they had been received by Governor John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen. On 19 June 1643, Dom Miguel de Castro arrived in Flushing, where he was received by three directors of the Zealand chamber of the Dutch West India Company, and who provided him with accommodation in Middelburg. Eventually he was sailed by yacht to The Hague on 2 July 1643, where he had an audience with stadtholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange.

#historical art#historical portrait#artwork#oil on panel#fine art#oil painting#don miguel de castro#dutch history#dutch brazil#portrait#man#half length#african#costume#plumed hat#congo emmisary#dutch culture#dutch art#jaspar beckx#dutch painter#european art#17th century painting#statens museum for kunst

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

His Royal Majesty, King William V (1895-1932) and his wife, Royal Consort and Queen Mother Beatrice Haversham-Schulman of Winchester (1892-1986), m.1915.

William V ascended the throne upon the death (1925) of his mother, Queen Mary II passed away.

His father, King Edmund III died in 1918 as tragedy visited the family in the form of the global influenza epidemic, and his older brother, King George IX (died without issue) passed away in a motorway accident in 1919.

The tragedy would continue, however, when William died of lung and throat cancer in 1932 on the eve of the Second World War. Fortunately, his son King Henry II was up to the challenge of steering the Empire through the impending crises.

William and Beatrice were survived by their sons, King Henry II and Prince Edmund. They were said to be a relatively happy couple, amicable and well-liked by the public. However, the losses within the family greatly affected Henry, despite William and Beatrice's best efforts to protect him and prepare him for the throne.

Beatrice was known to actively dislike and oppose--although only ever in private--Henry's wife, and opposed their marriage from the beginning. Still, it could be argued that she did all she could to protect her son until the day she died.

#c: william v#c: prince edmund of saxony and winchester#c: queen mother beatrice#c: henry ii#c: george ix#c: queen mary ii#c: gwyneth#LORE DUMP#moar loar

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

↬ Warwick Wives (2/7) | royal wives during the reigns of Louis III & James I, 1817 - 1857

Both Louis III and James I were unpopular, their reigns were characterised mostly by the royal family's struggle to produce a male heir. In the mid-nineteenth century, the middle-aged, promiscuous and ill-tempered sons of Louis II, vied for the throne. They scrambled to marry and have children. This power struggle divided their young wives, who over the years became jealous, power-hungry, and cunning.

E L I Z A B E T H was the daughter of a wealthy American merchant, the first of House Warwick's many American brides. She married Hereditary Prince Frederick, the only child of King Louis III, in 1826. Criticized as morganatic, the marriage was harmonious but deeply unpopular. Elizabeth was tiny but fierce, with Frederick calling her his "Pocket Artemis" due to her spirited personality and uncharacteristic love of hunting. During her time as Hereditary Princess, Elizabeth was a strong voice for social reforms, although her activism was pointedly ignored by the staunchly conservative king and royal dukes. Elizabeth and Frederick had no children at the time of his early death, sparking a succession crisis. Elizabeth remained close to her in-laws, but later remarried and had four children, the eldest of which was named Frederick.

C A R O L I N E married fifty-three-year-old James, Duke of Lennox when she was twenty-six. The marriage was chiefly a political one, in light of Prince Frederick's death and King Louis III's unhappy marriage with Queen Mary Caroline the Duke was increasingly likely to succeed to the throne. James despised his younger brothers, the Dukes of Glenciarn, Bessarion, Westminster, and Keele, and saw them as a threat to his inheritance. When a healthy son, the future Louis IV, was born in 1840, James was relieved.

Caroline herself was miserable. Her marriage to James had also produced several children who were stillborn or died in infancy. With her health permanently weakened, Caroline was isolated at Lennox House, where she lived with Louis separately from her husband. German by birth, she spoke broken English (although many historians believe this was an act to appear unassuming) and had a hard time adjusting to life in Sunderland. When she became Queen, her situation improved, but she attracted the ire of the Duchess of Glencairn by snubbing her son. Their rivalry would haunt Caroline for the rest of her life. While she was an affectionate mother to Louis, Caroline was intentionally cruel to James's numerous illegitimate children. She promptly banished them from court after James died in 1857.

Caroline has the great accomplishment of being the first woman to serve as a regent. During Louis IV's minority, she governed with a surprising level of competence; but she was unable to control Louis, who had grown temperamental and spoilt.

I M O G E N was stern and grim, with a sharp, unsmiling face. Despite this, in 1837 she left her home in England for the man she loved—the kindhearted Prince Henry, an amateur playwright and the third son of King Louis II. Imogen was passionately in love with her husband and she took pride in her two children. The couple's youngest, George, was the first male-line grandson of Louis II since Hereditary Prince Frederick's death, and Imogen was convinced he would be king someday.

Imogen was crushed by Henry's early death in 1840; after which she became paranoid, controlling, and antagonistic. For the next eighteen years, Imogen clung to George, fearing that his uncles would murder him to secure their own claims. When King Louis IV was enthroned in 1857, with Imogen's arch-enemy Queen Caroline serving as regent, Imogen returned to London, dragging her reluctant teenage children with her. By the time George became king in 1860, Imogen was estranged from him. The pair only reconciled after George became a father in 1862.

E L I Z A B E T H was another German princess who married a son of King Louis II. Prince Reginald's horrific reputation preseeded him, and the seventeen-year-old Elizabeth trembled on her way up to the altar. Reginald was a career soldier who lived a Spartan lifestyle and the rumours surrounding him ranged from off-putting to abhorrent. Luckily for Elizabeth, these rumours were mostly conjecture, and Reginald treated his wife with a "passing indifference". Reginald's military career was sporadic, and he left Elizabeth alone at his city estate for increasingly long stretches of time.

Elizabeth ran a carefree but lonely household. She was often seen picking flowers around the mansion's perimeter and trying to befriend the serving girls and vagabond women who passed through the estate, often giving away her possessions to win their friendship. In her later years, Elizabeth was aggravated by her late husband's debts. While Queen Alexandra, dismissed Elizabeth as peu de chose (not much), King George I was saddened when Elizabeth died.

J A N E had a habit of chewing on caraway seeds. She was pleasant, but known to pry. She came from a family of Sunderlandian aristocracy, a descendant of the Prussian entourage that followed King Louis I and Queen Whilmenina into Sunderland in the 1780s. Her family name Smith was adopted after King Louis II anglicized his own name from the German Hohenzollern to Warwick—an attempt to distance himself from Prussia. Jane married King Louis II's youngest surviving son, Prince Robert, who was fifteen years her senior. Robert was polarizing and widely despised for his controversial stint in the House of Lords. Despite this, the marriage was a happy one and Robert doted on his wife. Jane was the favourite aunt of King Louis IV but his successor, George I, had little love for her and his mother distrusted her.

M A R T H A was a large and domineering woman. Despite marrying the fifth son of King Louis II, she had a bravado that outpaced her station. Unlike her sisters-in-law, Martha remained a prominent member of the royal family during the reign of her nephew, King George I. Known to be an extravagant hostess, Dear Aunt Westminster drank and ate in excess, and habitually burned through her generous pension. She also quarrelled with Queen Alexandra, who thought her impertinent. Family drama quashed Martha's high ambitions in the later half of the 19th century. Her elder son was disinherited after marrying his mistress and her second entered a loveless political union that produced one daughter, Anne. Martha died at the age of ninety-five in 1911, making her one of the longest-lived members of the royal family. Just two years after her death, her granddaughter Anne married the future King George II.

#warwick.extras#warwick.wives#tw pregnancy loss#gif warning#✨#ts4#ts4 story#ts4 royal#ts4 storytelling#ts4 edit#ts4 royal legacy#ts4 legacy#ts4 royalty#ts4 monarchy#ts4 screenshots#ts4 historical

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

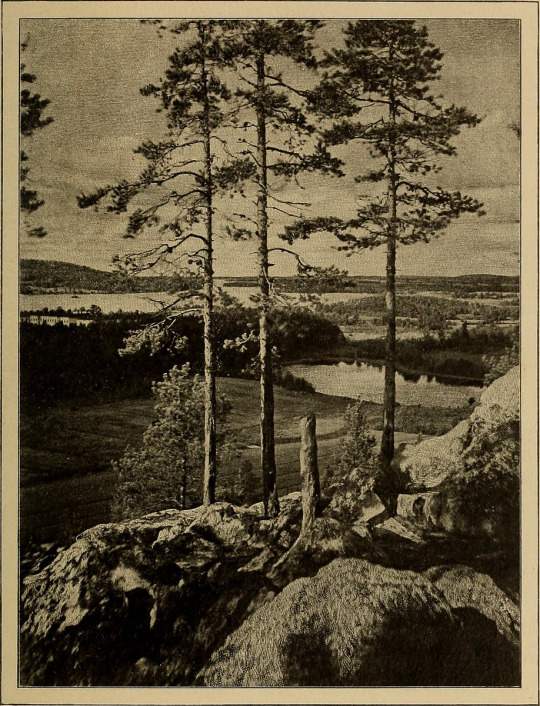

Tree-Worship in Finland

"Near Kuopio, in Finland, there was a famous grove of ancient moss-grown firs, where the people offered sacrifices and practised superstitious customs down to about 1650, when a sturdy veteran of the Thirty Years' War dared to cut it down at the bidding of the pastor. Sacred groves now hardly exist in Finland, but sacred trees to which offerings are brought are still not very uncommon. On some firs the skulls of bears are nailed, apparently that the hunter may have good luck in the chase."

—J.G. Frazer, The Magic Art & the Evolution of Kings, part 2 (The Golden Bough, vol. II, 1911, p. 11)

Fir trees in Finland, c. 1902 from All the Russias, by Henry Norman.

(Source: Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons)

#trees#tree-worship#finland#fir trees#sacrifices#superstition#1650#thirty years' war#sacred grove#kuopio#jg frazer#the golden bough#the golden bough vol ii

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Below the cut I have made a list of each English and British monarch, the age of their mothers at their births, and which number pregnancy they were the result of. Particularly before the early modern era, the perception of Queens and childbearing is quite skewed, which prompted me to make this list. I started with William I as the Anglo-Saxon kings didn’t have enough information for this list.

House of Normandy

William I (b. c.1028)

Son of Herleva (b. c.1003)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

William II (b. c.1057/60)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Third pregnancy at minimum, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 26/29 at birth.

Henry I (b. c.1068)

Son of Matilda of Flanders (b. c.1031)

Fourth pregnancy at minimum, more likely eighth or ninth, although exact birth order is unclear.

Approx age 37 at birth.

Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

Daughter of Matilda of Scotland (b. c.1080)

First pregnancy, possibly second.

Approx age 22 at birth.

Stephen (b. c.1092/6)

Son of Adela of Normandy (b. c.1067)

Fifth pregnancy, although exact birth order is uncertain.

Approx age 25/29 at birth.

Henry II (b. 5 Mar 1133)

Son of Empress Matilda (b. 7 Feb 1102)

First pregnancy.

Age 31 at birth.

Richard I (b. 8 Sep 1157)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 35 at birth.

John (b. 24 Dec 1166)

Son of Eleanor of Aquitaine (b. c.1122)

Tenth pregnancy.

Approx age 44 at birth.

House of Plantagenet

Henry III (b. 1 Oct 1207)

Son of Isabella of Angoulême (b. c.1186/88)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 19/21 at birth.

Edward I (b. 17 Jun 1239)

Son of Eleanor of Provence (b. c.1223)

First pregnancy.

Age approx 16 at birth.

Edward II (b. 25 Apr 1284)

Son of Eleanor of Castile (b. c.1241)

Sixteenth pregnancy.

Approx age 43 at birth.

Edward III (b. 13 Nov 1312)

Son of Isabella of France (b. c.1295)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 17 at birth.

Richard II (b. 6 Jan 1367)

Son of Joan of Kent (b. 29 Sep 1326/7)

Seventh pregnancy.

Approx age 39/40 at birth.

House of Lancaster

Henry IV (b. c.Apr 1367)

Son of Blanche of Lancaster (b. 25 Mar 1342)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 25 at birth.

Henry V (b. 16 Sep 1386)

Son of Mary de Bohun (b. c.1369/70)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 16/17 at birth.

Henry VI (b. 6 Dec 1421)

Son of Catherine of Valois (b. 27 Oct 1401)

First pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

House of York

Edward IV (b. 28 Apr 1442)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Third pregnancy.

Age 26 at birth.

Edward V (b. 2 Nov 1470)

Son of Elizabeth Woodville (b. c.1437)

Sixth pregnancy.

Approx age 33 at birth.

Richard III (b. 2 Oct 1452)

Son of Cecily Neville (b. 3 May 1415)

Eleventh pregnancy.

Age 37 at birth.

House of Tudor

Henry VII (b. 28 Jan 1457)

Son of Margaret Beaufort (b. 31 May 1443)

First pregnancy.

Age 13 at birth.

Henry VIII (b. 28 Jun 1491)

Son of Elizabeth of York (b. 11 Feb 1466)

Third pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Edward VI (b. 12 Oct 1537)

Son of Jane Seymour (b. c.1509)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 28 at birth.

Jane (b. c.1537)

Daughter of Frances Brandon (b. 16 Jul 1517)

Third pregnancy.

Approx age 20 at birth.

Mary I (b. 18 Feb 1516)

Daughter of Catherine of Aragon (b. 16 Dec 1485)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

Elizabeth I (b. 7 Sep 1533)

Daughter of Anne Boleyn (b. c.1501/7)

First pregnancy.

Approx age 26/32 at birth.

House of Stuart

James I (b. 19 Jun 1566)

Son of Mary I of Scotland (b. 8 Dec 1542)

First pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

Charles I (b. 19 Nov 1600)

Son of Anne of Denmark (b. 12 Dec 1574)

Fifth pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles II (b. 29 May 1630)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

James II (14 Oct 1633)

Son of Henrietta Maria of France (b. 25 Nov 1609)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 23 at birth.

William III (b. 4 Nov 1650)

Son of Mary, Princess Royal (b. 4 Nov 1631)

Second pregnancy.

Age 19 at birth.

Mary II (b. 30 Apr 1662)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Second pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Anne (b. 6 Feb 1665)

Daughter of Anne Hyde (b. 12 Mar 1637)

Fourth pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

House of Hanover

George I (b. 28 May 1660)

Son of Sophia of the Palatinate (b. 14 Oct 1630)

First pregnancy.

Age 30 at birth.

George II (b. 9 Nov 1683)

Son of Sophia Dorothea of Celle (b. 15 Sep 1666)

First pregnancy.

Age 17 at birth.

George III (b. 4 Jun 1738)

Son of Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (b. 30 Nov 1719)

Second pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

George IV (b. 12 Aug 1762)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

First pregnancy.

Age 18 at birth.

William IV (b. 21 Aug 1765)

Son of Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (b. 19 May 1744)

Third pregnancy.

Age 21 at birth.

Victoria (b. 24 May 1819)

Daughter of Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saafield (b. 17 Aug 1786)

Third pregnancy.

Age 32 at birth.

Edward VII (b. 9 Nov 1841)

Daughter of Victoria of the United Kingdom (b. 24 May 1819)

Second pregnancy.

Age 22 at birth.

House of Windsor

George V (b. 3 Jun 1865)

Son of Alexandra of Denmark (b. 1 Dec 1844)

Second pregnancy.

Age 20 at birth.

Edward VIII (b. 23 Jun 1894)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

First pregnancy.

Age 27 at birth.

George VI (b. 14 Dec 1895)

Son of Mary of Teck (b. 26 May 1867)

Second pregnancy.

Age 28 at birth.

Elizabeth II (b. 21 Apr 1926)

Daughter of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon (b. 4 Aug 1900)

First pregnancy.

Age 25 at birth.

Charles III (b. 14 Nov 1948)