#came from the plights of WOMEN OF COLOR throughout history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

an executive producer of The Handmaid’s Tale was cheering that trump won under an insta post from justine bateman and idk why anyone is surprised when the lead actress has always been balls deep in Scientology

#g talks#the handmaid’s tale tv series has always been a joke#bc to the people making it its just an adaptation of a book#it’s never meant anything serious to them#based on who they’ve hired to make it#and Atwood herself said the inspiration for the book#came from the plights of WOMEN OF COLOR throughout history#yet the main characters in the tv series are white as fuck#and the feminists that watch it rave about it bc they can finally relate#because the women affected are all white#it’s like the fucking morons putting their voted stickers on Susan B Anthony’s grave#after voting for Kamala#as if Susan would’ve supported their decision at all#that bitch didn’t consider black people HUMAN BEINGS#there’s a reason white women could vote years in advance#but modern white feminists don’t think about it#they still exclude black women from their feminism#and believe that just voting for a black woman is enough#to make up for what white feminists have done#or just white women in general#while they’re STILL worshipping women like Margaret Sanger and Susan B Anthony#it’s just embarrassing#mine#/mobile#/okay to reblog

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

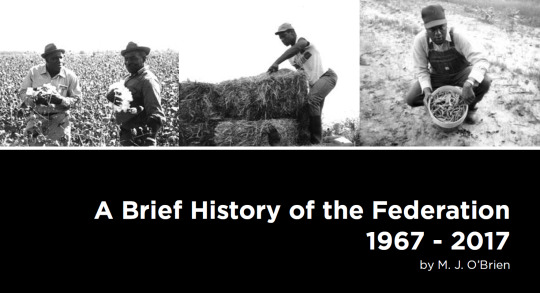

What We Do in the Past, Echoes in the Future

Given the state of our country right now due to the unjust killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and so many others, it reminded me of a short essay I wrote about discrimination last year. It covers from the time of the Harlem Renaissance to 2020. How black people in America continue to face the same prejudice time and time again. This particular essay examines Claude McKay’s poem If We Must Die, Danez Smith’s piece dear white america, and Malcolm X’s speech The Ballot or the Bullet.

Not everyone can be at the protests and it can make you feel like you aren’t doing enough to help. If you’re like me, I constantly question “what can I do? how can I help? We can donate to the organizations, but if you can’t afford it, one of the most important things EVERY ONE can and should do is listen. Stay informed. Learn our history. Change the future.

I’ve included both poems and the speech. The Ballot or the Bullet is long, but I urge you all to read it or listen to it on youtube. It’s a difficult conversation to keep having, but we must keep speaking up for the victims of the systematic racism in this country and continue to fight for justice, by any means necessary.

What We Do in the Past, Echoes in the Future

By Arriana M. Williams

Literature and art have always been powerful tools for expressing and analyzing the human condition. We write as a way to leave something lasting and tangible for the next generation to, hopefully, improve upon society as a whole. When it comes to the marginalized communities of the world, specifically in our country, the role and value of literature becomes essential in understanding the plights and difficulties these people have faced in history and today. By reading the works created by these men and women, we gain a more intimate and personal insight into their struggles, aspirations, and their outlook of the world and their hopes of a brighter future. As cliché as that may sound, it was the ultimate goal of men like Martin Luther King Jr, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and so many more. While these men followed in the footsteps of men like Claude McKay, who defined his perspective of racism in his poem “If We Must Die”, they also inspired those who came after them. Men like Danez Smith, who in his poem, “Dear White America”, addresses the typical perspectives white people have towards those of color in America. Although reading and writing is not a cure-all for discrimination or injustices in America, it is hard to deny that the old adage is true. That those who do not learn history, are doomed to repeat it.

Take for example Malcolm X’s speech, "The Ballot or the Bullet". Given as a response to congress deliberating about the Civil Rights Act, which would prohibit discrimination based on race, sex, religion, and origin. This speech is considered to be one of his best as it clearly and sophisticatedly describes how people of color in America must demand equality regardless of economic class or political affiliation. His message was not aimed towards any specific group of black Americans, nor religious associations. Malcolm X was a very relatable figure in that, the way he spoke was how common people spoke. He was intelligent, but he was not a politician.

The tone of his speeches touched people because of how passionate he was, but also how he was just like us. A man who wanted a better life for himself and his people, a man who was genuine in his convictions. Some people consider him to have been a radical, because he believed that the disenfranchised should demand equality “by any means necessary”. His goal was to urge black people to use their votes as a way to progress their civil rights. To do this, he used some humor to connect to the masses. His use of Muhammad Ali as a metaphor in this speech may have been funny, stating that we should not be “singing” for freedom or treading lightly in this fight. But he goes on to say, “But you can swing up on some freedom. Cassius Clay can sing. But singing didn’t help him to become the heavyweight champion of the world. Swinging helped him” (Malcolm X 338). His tone grows from humorous to serious because he tries to exclaim that we must come to terms with when enough is enough. Malcolm X gave this speech in 1964, forty- five years after Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die”, but the message remains the same.

Malcolm X was trying to usher his people into a new world, a new way of thinking and living in America. Claude McKay was originally from Jamaica, but when he moved to the United States for higher education, he experienced racism first-hand which inspired him to begin writing poetry. His poem, “If We Must Die”, is written from the perspective of a black man speaking about fighting back when it comes to racism. The final line is the most powerful stating, “Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack/Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” (McKay 139). The speaker says that their blood will not be shed in vain and this poem goes on to display themes of the frustrations and concerns with discrimination and with the state of the country. Written in 1919, this poem is yet another example of people of color no longer willing to take the horrendous treatment of them in America anymore. This is a pattern in the pieces of literature throughout the Harlem Renaissance, when the dynamics in the country were beginning to change, after slavery was abolished but before the civil rights movement began. Basically, black people were beginning to fight back against oppression, just like Malcolm X explained in his speech, even decades after McKay’s poem, that people of color must continue to fight back by any means necessary.

Perhaps to a layman on the subjects of racial experiences, maltreatment, or persecution, it would seem like things have improved when it comes to inequality in America. So why are we still reading about prejudice and racism? All of the men I mentioned, Martin Luther King Jr, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X were assassinated in this country. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that there is still room for improvement. Even during the era of our first black president, men and women of color were still living in fear of many threats. In “Dear White America”, Smith uses metaphors for religion and the justice system in our country as examples of how people of color are often the ones left out of “God’s miracles”. He mentions the issue of mass incarceration of black men and says, “I’m sick of calling your recklessness the law” (315) which is a statement of the epidemic of police involved shootings of unarmed black people. Smith goes on to address the typical “white” perspectives towards people of color in America. Like the, “I just don’t see race” and “Why does it always have to be about race” (315).

The poem is written in a way that the speaker is acknowledging the problems with common, white opinions. That they do not understand the harm they cause, but the speaker is attempting to enlighten them from a person of color’s point of view. The piece progresses from just words that are detrimental and hurtful stereotypes, to the ongoing violence black/brown people must endure in this country. The tone of this poem, as in all of the other works, is angry, the speaker does not want to remain silent and in the ends tells the “white audience” that they will create a new world, one that cannot be stolen, sold, beaten, hanged, or shot and that, “this, if only this one, is ours” (315). It is discouraging that from 1919 to 2019 we are still analyzing these types of experiences in literature, because they continue to be relevant. Many people believe that living in a post- Obama America means racism is eradicated, but all it takes is to open a book, watch the news, or check social media to see that notion could not be further from the truth.

What all of these pieces have in common, are the ways in which literature and assembly of like- minded individuals can open up a space for those whose voices might not be heard otherwise. The written word is a medium unlike any other in the way that it can stand the test of time, to be passed down from generation to generation. While some subjects are incredibly depressing to endure, they remain extremely poignant time after time. With something as complicated as racial issues, we need literature to understand the speakers that came before us. To gain more awareness of how far we’ve come, and how much more we have to work on in this country. From Malcolm X, to the poets of today, the similarities far outweigh the differences in their experiences, which is both concerning and comforting in a way. It is unfortunate that people of color are still facing such ordeals today, but that fact that so many before them faced trials and tribulations, it goes to the strength and power they possessed in order to keep fighting. To keep fighting for equality and the advancement of the people.

If We Must Die

BY CLAUDE MCKAY

If we must die, let it not be like hogs Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot, While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs, Making their mock at our accursèd lot. If we must die, O let us nobly die, So that our precious blood may not be shed In vain; then even the monsters we defy Shall be constrained to honor us though dead! O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe! Though far outnumbered let us show us brave, And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow! What though before us lies the open grave? Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

dear white america

BY DANEZ SMITH

i’ve left Earth in search of darker planets, a solar system revolving too near a black hole. i’ve left in search of a new God. i do not trust the God you have given us. my grandmother’s hallelujah is only outdone by the fear she nurses every time the blood-fat summer swallows another child who used to sing in the choir. take your God back. though his songs are beautiful, his miracles are inconsistent. i want the fate of Lazarus for Renisha, want Chucky, Bo, Meech, Trayvon, Sean & Jonylah risen three days after their entombing, their ghost re-gifted flesh & blood, their flesh & blood re-gifted their children. i’ve left Earth, i am equal parts sick of your go back to Africa & i just don’t see race. neither did the poplar tree. we did not build your boats (though we did leave a trail of kin to guide us home). we did not build your prisons (though we did & we fill them too). we did not ask to be part of your America (though are we not America? her joints brittle & dragging a ripped gown through Oakland?). i can’t stand your ground. i’m sick of calling your recklessness the law. each night, i count my brothers. & in the morning, when some do not survive to be counted, i count the holes they leave. i reach for black folks & touch only air. your master magic trick, America. now he’s breathing, now he don’t. abra-cadaver. white bread voodoo. sorcery you claim not to practice, hand my cousin a pistol to do your work. i tried, white people. i tried to love you, but you spent my brother’s funeral making plans for brunch, talking too loud next to his bones. you took one look at the river, plump with the body of boy after girl after sweet boi & ask why does it always have to be about race? because you made it that way! because you put an asterisk on my sister’s gorgeous face! call her pretty (for a black girl)! because black girls go missing without so much as a whisper of where?! because there are no amber alerts for amber-skinned girls! because Jordan boomed. because Emmett whistled. because Huey P. spoke. because Martin preached. because black boys can always be too loud to live. because it’s taken my papa’s & my grandma’s time, my father’s time, my mother’s time, my aunt’s time, my uncle’s time, my brother’s & my sister’s time . . . how much time do you want for your progress? i’ve left Earth to find a place where my kin can be safe, where black people ain’t but people the same color as the good, wet earth, until that means something, until then i bid you well, i bid you war, i bid you our lives to gamble with no more. i’ve left Earth & i am touching everything you beg your telescopes to show you. i’m giving the stars their right names. & this life, this new story & history you cannot steal or sell or cast overboard or hang or beat or drown or own or redline or shackle or silence or cheat or choke or cover up or jail or shoot or jail or shoot or jail or shoot or ruin

this, if only this one, is ours.

The Ballot or the Bullet

by Malcolm X April 3, 1964 Cleveland, Ohio

Mr. Moderator, Brother Lomax, brothers and sisters, friends and enemies: I just can't believe everyone in here is a friend, and I don't want to leave anybody out. The question tonight, as I understand it, is "The Negro Revolt, and Where Do We Go From Here?" or What Next?" In my little humble way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet.

Before we try and explain what is meant by the ballot or the bullet, I would like to clarify something concerning myself. I'm still a Muslim; my religion is still Islam. That's my personal belief. Just as Adam Clayton Powell is a Christian minister who heads the Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, but at the same time takes part in the political struggles to try and bring about rights to the black people in this country; and Dr. Martin Luther King is a Christian minister down in Atlanta, Georgia, who heads another organization fighting for the civil rights of black people in this country; and Reverend Galamison, I guess you've heard of him, is another Christian minister in New York who has been deeply involved in the school boycotts to eliminate segregated education; well, I myself am a minister, not a Christian minister, but a Muslim minister; and I believe in action on all fronts by whatever means necessary.

Although I'm still a Muslim, I'm not here tonight to discuss my religion. I'm not here to try and change your religion. I'm not here to argue or discuss anything that we differ about, because it's time for us to submerge our differences and realize that it is best for us to first see that we have the same problem, a common problem, a problem that will make you catch hell whether you're a Baptist, or a Methodist, or a Muslim, or a nationalist. Whether you're educated or illiterate, whether you live on the boulevard or in the alley, you're going to catch hell just like I am. We're all in the same boat and we all are going to catch the same hell from the same man. He just happens to be a white man. All of us have suffered here, in this country, political oppression at the hands of the white man, economic exploitation at the hands of the white man, and social degradation at the hands of the white man.

Now in speaking like this, it doesn't mean that we're anti-white, but it does mean we're anti-exploitation, we're anti-degradation, we're anti-oppression. And if the white man doesn't want us to be anti-him, let him stop oppressing and exploiting and degrading us. Whether we are Christians or Muslims or nationalists or agnostics or atheists, we must first learn to forget our differences. If we have differences, let us differ in the closet; when we come out in front, let us not have anything to argue about until we get finished arguing with the man. If the late President Kennedy could get together with Khrushchev and exchange some wheat, we certainly have more in common with each other than Kennedy and Khrushchev had with each other.

If we don't do something real soon, I think you'll have to agree that we're going to be forced either to use the ballot or the bullet. It's one or the other in 1964. It isn't that time is running out -- time has run out!

1964 threatens to be the most explosive year America has ever witnessed. The most explosive year. Why? It's also a political year. It's the year when all of the white politicians will be back in the so-called Negro community jiving you and me for some votes. The year when all of the white political crooks will be right back in your and my community with their false promises, building up our hopes for a letdown, with their trickery and their treachery, with their false promises which they don't intend to keep. As they nourish these dissatisfactions, it can only lead to one thing, an explosion; and now we have the type of black man on the scene in America today -- I'm sorry, Brother Lomax -- who just doesn't intend to turn the other cheek any longer.

Don't let anybody tell you anything about the odds are against you. If they draft you, they send you to Korea and make you face 800 million Chinese. If you can be brave over there, you can be brave right here. These odds aren't as great as those odds. And if you fight here, you will at least know what you're fighting for.

I'm not a politician, not even a student of politics; in fact, I'm not a student of much of anything. I'm not a Democrat. I'm not a Republican, and I don't even consider myself an American. If you and I were Americans, there'd be no problem. Those Honkies that just got off the boat, they're already Americans; Polacks are already Americans; the Italian refugees are already Americans. Everything that came out of Europe, every blue-eyed thing, is already an American. And as long as you and I have been over here, we aren't Americans yet.

Well, I am one who doesn't believe in deluding myself. I'm not going to sit at your table and watch you eat, with nothing on my plate, and call myself a diner. Sitting at the table doesn't make you a diner, unless you eat some of what's on that plate. Being here in America doesn't make you an American. Being born here in America doesn't make you an American. Why, if birth made you American, you wouldn't need any legislation; you wouldn't need any amendments to the Constitution; you wouldn't be faced with civil-rights filibustering in Washington, D.C., right now. They don't have to pass civil-rights legislation to make a Polack an American.

No, I'm not an American. I'm one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. One of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but disguised hypocrisy. So, I'm not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver -- no, not I. I'm speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don't see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.

These 22 million victims are waking up. Their eyes are coming open. They're beginning to see what they used to only look at. They're becoming politically mature. They are realizing that there are new political trends from coast to coast. As they see these new political trends, it's possible for them to see that every time there's an election the races are so close that they have to have a recount. They had to recount in Massachusetts to see who was going to be governor, it was so close. It was the same way in Rhode Island, in Minnesota, and in many other parts of the country. And the same with Kennedy and Nixon when they ran for president. It was so close they had to count all over again. Well, what does this mean? It means that when white people are evenly divided, and black people have a bloc of votes of their own, it is left up to them to determine who's going to sit in the White House and who's going to be in the dog house.

lt. was the black man's vote that put the present administration in Washington, D.C. Your vote, your dumb vote, your ignorant vote, your wasted vote put in an administration in Washington, D.C., that has seen fit to pass every kind of legislation imaginable, saving you until last, then filibustering on top of that. And your and my leaders have the audacity to run around clapping their hands and talk about how much progress we're making. And what a good president we have. If he wasn't good in Texas, he sure can't be good in Washington, D.C. Because Texas is a lynch state. It is in the same breath as Mississippi, no different; only they lynch you in Texas with a Texas accent and lynch you in Mississippi with a Mississippi accent. And these Negro leaders have the audacity to go and have some coffee in the White House with a Texan, a Southern cracker -- that's all he is -- and then come out and tell you and me that he's going to be better for us because, since he's from the South, he knows how to deal with the Southerners. What kind of logic is that? Let Eastland be president, he's from the South too. He should be better able to deal with them than Johnson.

In this present administration they have in the House of Representatives 257 Democrats to only 177 Republicans. They control two-thirds of the House vote. Why can't they pass something that will help you and me? In the Senate, there are 67 senators who are of the Democratic Party. Only 33 of them are Republicans. Why, the Democrats have got the government sewed up, and you're the one who sewed it up for them. And what have they given you for it? Four years in office, and just now getting around to some civil-rights legislation. Just now, after everything else is gone, out of the way, they're going to sit down now and play with you all summer long -- the same old giant con game that they call filibuster. All those are in cahoots together. Don't you ever think they're not in cahoots together, for the man that is heading the civil- rights filibuster is a man from Georgia named Richard Russell. When Johnson became president, the first man he asked for when he got back to Washington, D.C., was "Dicky" -- that's how tight they are. That's his boy, that's his pal, that's his buddy. But they're playing that old con game. One of them makes believe he's for you, and he's got it fixed where the other one is so tight against you, he never has to keep his promise.

So it's time in 1964 to wake up. And when you see them coming up with that kind of conspiracy, let them know your eyes are open. And let them know you -- something else that's wide open too. It's got to be the ballot or the bullet. The ballot or the bullet. If you're afraid to use an expression like that, you should get on out of the country; you should get back in the cotton patch; you should get back in the alley. They get all the Negro vote, and after they get it, the Negro gets nothing in return. All they did when they got to Washington was give a few big Negroes big jobs. Those big Negroes didn't need big jobs, they already had jobs. That's camouflage, that's trickery, that's treachery, window-dressing. I'm not trying to knock out the Democrats for the Republicans. We'll get to them in a minute. But it is true; you put the Democrats first and the Democrats put you last.

Look at it the way it is. What alibis do they use, since they control Congress and the Senate? What alibi do they use when you and I ask, "Well, when are you going to keep your promise?" They blame the Dixiecrats. What is a Dixiecrat? A Democrat. A Dixiecrat is nothing but a Democrat in disguise. The titular head of the Democrats is also the head of the Dixiecrats, because the Dixiecrats are a part of the Democratic Party. The Democrats have never kicked the Dixiecrats out of the party. The Dixiecrats bolted themselves once, but the Democrats didn't put them out. Imagine, these lowdown Southern segregationists put the Northern Democrats down. But the Northern Democrats have never put the Dixiecrats down. No, look at that thing the way it is. They have got a con game going on, a political con game, and you and I are in the middle. It's time for you and me to wake up and start looking at it like it is, and trying to understand it like it is; and then we can deal with it like it is.

The Dixiecrats in Washington, D.C., control the key committees that run the government. The only reason the Dixiecrats control these committees is because they have seniority. The only reason they have seniority is because they come from states where Negroes can't vote. This is not even a government that's based on democracy. lt. is not a government that is made up of representatives of the people. Half of the people in the South can't even vote. Eastland is not even supposed to be in Washington. Half of the senators and congressmen who occupy these key positions in Washington, D.C., are there illegally, are there unconstitutionally.

I was in Washington, D.C., a week ago Thursday, when they were debating whether or not they should let the bill come onto the floor. And in the back of the room where the Senate meets, there's a huge map of the United States, and on that map it shows the location of Negroes throughout the country. And it shows that the Southern section of the country, the states that are most heavily concentrated with Negroes, are the ones that have senators and congressmen standing up filibustering and doing all other kinds of trickery to keep the Negro from being able to vote. This is pitiful. But it's not pitiful for us any longer; it's actually pitiful for the white man, because soon now, as the Negro awakens a little more and sees the vise that he's in, sees the bag that he's in, sees the real game that he's in, then the Negro's going to develop a new tactic.

These senators and congressmen actually violate the constitutional amendments that guarantee the people of that particular state or county the right to vote. And the Constitution itself has within it the machinery to expel any representative from a state where the voting rights of the people are violated. You don't even need new legislation. Any person in Congress right now, who is there from a state or a district where the voting rights of the people are violated, that particular person should be expelled from Congress. And when you expel him, you've removed one of the obstacles in the path of any real meaningful legislation in this country. In fact, when you expel them, you don't need new legislation, because they will be replaced by black representatives from counties and districts where the black man is in the majority, not in the minority.

If the black man in these Southern states had his full voting rights, the key Dixiecrats in Washington, D. C., which means the key Democrats in Washington, D.C., would lose their seats. The Democratic Party itself would lose its power. It would cease to be powerful as a party. When you see the amount of power that would be lost by the Democratic Party if it were to lose the Dixiecrat wing, or branch, or element, you can see where it's against the interests of the Democrats to give voting rights to Negroes in states where the Democrats have been in complete power and authority ever since the Civil War. You just can't belong to that Party without analyzing it.

I say again, I'm not anti-Democrat, I'm not anti-Republican, I'm not anti-anything. I'm just questioning their sincerity, and some of the strategy that they've been using on our people by promising them promises that they don't intend to keep. When you keep the Democrats in power, you're keeping the Dixiecrats in power. I doubt that my good Brother Lomax will deny that. A vote for a Democrat is a vote for a Dixiecrat. That's why, in 1964, it's time now for you and me to become more politically mature and realize what the ballot is for; what we're supposed to get when we cast a ballot; and that if we don't cast a ballot, it's going to end up in a situation where we're going to have to cast a bullet. It's either a ballot or a bullet.

In the North, they do it a different way. They have a system that's known as gerrymandering, whatever that means. It means when Negroes become too heavily concentrated in a certain area, and begin to gain too much political power, the white man comes along and changes the district lines. You may say, "Why do you keep saying white man?" Because it's the white man who does it. I haven't ever seen any Negro changing any lines. They don't let him get near the line. It's the white man who does this. And usually, it's the white man who grins at you the most, and pats you on the back, and is supposed to be your friend. He may be friendly, but he's not your friend.

So, what I'm trying to impress upon you, in essence, is this: You and I in America are faced not with a segregationist conspiracy, we're faced with a government conspiracy. Everyone who's filibustering is a senator -- that's the government. Everyone who's finagling in Washington, D.C., is a congressman -- that's the government. You don't have anybody putting blocks in your path but people who are a part of the government. The same government that you go abroad to fight for and die for is the government that is in a conspiracy to deprive you of your voting rights, deprive you of your economic opportunities, deprive you of decent housing, deprive you of decent education. You don't need to go to the employer alone, it is the government itself, the government of America, that is responsible for the oppression and exploitation and degradation of black people in this country. And you should drop it in their lap. This government has failed the Negro. This so-called democracy has failed the Negro. And all these white liberals have definitely failed the Negro.

So, where do we go from here? First, we need some friends. We need some new allies. The entire civil-rights struggle needs a new interpretation, a broader interpretation. We need to look at this civil-rights thing from another angle -- from the inside as well as from the outside. To those of us whose philosophy is black nationalism, the only way you can get involved in the civil-rights struggle is give it a new interpretation. That old interpretation excluded us. It kept us out. So, we're giving a new interpretation to the civil-rights struggle, an interpretation that will enable us to come into it, take part in it. And these handkerchief-heads who have been dillydallying and pussy footing and compromising -- we don't intend to let them pussyfoot and dillydally and compromise any longer.

How can you thank a man for giving you what's already yours? How then can you thank him for giving you only part of what's already yours? You haven't even made progress, if what's being given to you, you should have had already. That's not progress. And I love my Brother Lomax, the way he pointed out we're right back where we were in 1954. We're not even as far up as we were in 1954. We're behind where we were in 1954. There's more segregation now than there was in 1954. There's more racial animosity, more racial hatred, more racial violence today in 1964, than there was in 1954. Where is the progress?

And now you're facing a situation where the young Negro's coming up. They don't want to hear that "turn the-other-cheek" stuff, no. In Jacksonville, those were teenagers, they were throwing Molotov cocktails. Negroes have never done that before. But it shows you there's a new deal coming in. There's new thinking coming in. There's new strategy coming in. It'll be Molotov cocktails this month, hand grenades next month, and something else next month. It'll be ballots, or it'll be bullets. It'll be liberty, or it will be death. The only difference about this kind of death -- it'll be reciprocal. You know what is meant by "reciprocal"? That's one of Brother Lomax's words. I stole it from him. I don't usually deal with those big words because I don't usually deal with big people. I deal with small people. I find you can get a whole lot of small people and whip hell out of a whole lot of big people. They haven't got anything to lose, and they've got every thing to gain. And they'll let you know in a minute: "It takes two to tango; when I go, you go."

The black nationalists, those whose philosophy is black nationalism, in bringing about this new interpretation of the entire meaning of civil rights, look upon it as meaning, as Brother Lomax has pointed out, equality of opportunity. Well, we're justified in seeking civil rights, if it means equality of opportunity, because all we're doing there is trying to collect for our investment. Our mothers and fathers invested sweat and blood. Three hundred and ten years we worked in this country without a dime in return -- I mean without a dime in return. You let the white man walk around here talking about how rich this country is, but you never stop to think how it got rich so quick. It got rich because you made it rich.

You take the people who are in this audience right now. They're poor. We're all poor as individuals. Our weekly salary individually amounts to hardly anything. But if you take the salary of everyone in here collectively, it'll fill up a whole lot of baskets. It's a lot of wealth. If you can collect the wages of just these people right here for a year, you'll be rich -- richer than rich. When you look at it like that, think how rich Uncle Sam had to become, not with this handful, but millions of black people. Your and my mother and father, who didn't work an eight-hour shift, but worked from "can't see" in the morning until "can't see" at night, and worked for nothing, making the white man rich, making Uncle Sam rich. This is our investment. This is our contribution, our blood.

Not only did we give of our free labor, we gave of our blood. Every time he had a call to arms, we were the first ones in uniform. We died on every battlefield the white man had. We have made a greater sacrifice than anybody who's standing up in America today. We have made a greater contribution and have collected less. Civil rights, for those of us whose philosophy is black nationalism, means: "Give it to us now. Don't wait for next year. Give it to us yesterday, and that's not fast enough."

I might stop right here to point out one thing. Whenever you're going after something that belongs to you, anyone who's depriving you of the right to have it is a criminal.

Understand that. Whenever you are going after something that is yours, you are within your legal rights to lay claim to it. And anyone who puts forth any effort to deprive you of that which is yours, is breaking the law, is a criminal. And this was pointed out by the Supreme Court decision. It outlawed segregation.

Which means segregation is against the law. Which means a segregationist is breaking the law. A segregationist is a criminal. You can't label him as anything other than that. And when you demonstrate against segregation, the law is on your side. The Supreme Court is on your side.

Now, who is it that opposes you in carrying out the law? The police department itself. With police dogs and clubs. Whenever you demonstrate against segregation, whether it is segregated education, segregated housing, or anything else, the law is on your side, and anyone who stands in the way is not the law any longer. They are breaking the law; they are not representatives of the law. Any time you demonstrate against segregation and a man has the audacity to put a police dog on you, kill that dog, kill him, I'm telling you, kill that dog. I say it, if they put me in jail tomorrow, kill that dog. Then you'll put a stop to it. Now, if these white people in here don't want to see that kind of action, get down and tell the mayor to tell the police department to pull the dogs in. That's all you have to do. If you don't do it, someone else will.

If you don't take this kind of stand, your little children will grow up and look at you and think "shame." If you don't take an uncompromising stand, I don't mean go out and get violent; but at the same time you should never be nonviolent unless you run into some nonviolence. I'm nonviolent with those who are nonviolent with me. But when you drop that violence on me, then you've made me go insane, and I'm not responsible for what I do. And that's the way every Negro should get. Any time you know you're within the law, within your legal rights, within your moral rights, in accord with justice, then die for what you believe in. But don't die alone. Let your dying be reciprocal. This is what is meant by equality. What's good for the goose is good for the gander.

When we begin to get in this area, we need new friends, we need new allies. We need to expand the civil-rights struggle to a higher level -- to the level of human rights. Whenever you are in a civil-rights struggle, whether you know it or not, you are confining yourself to the jurisdiction of Uncle Sam. No one from the outside world can speak out in your behalf as long as your struggle is a civil-rights struggle. Civil rights comes within the domestic affairs of this country. All of our African brothers and our Asian brothers and our Latin-American brothers cannot open their mouths and interfere in the domestic affairs of the United States. And as long as it's civil rights, this comes under the jurisdiction of Uncle Sam.

But the United Nations has what's known as the charter of human rights; it has a committee that deals in human rights. You may wonder why all of the atrocities that have been committed in Africa and in Hungary and in Asia, and in Latin America are brought before the UN, and the Negro problem is never brought before the UN. This is part of the conspiracy. This old, tricky blue eyed liberal who is supposed to be your and my friend, supposed to be in our corner, supposed to be subsidizing our struggle, and supposed to be acting in the capacity of an adviser, never tells you anything about human rights. They keep you wrapped up in civil rights. And you spend so much time barking up the civil-rights tree, you don't even know there's a human-rights tree on the same floor.

When you expand the civil-rights struggle to the level of human rights, you can then take the case of the black man in this country before the nations in the UN. You can take it before the General Assembly. You can take Uncle Sam before a world court. But the only level you can do it on is the level of human rights. Civil rights keeps you under his restrictions, under his jurisdiction. Civil rights keeps you in his pocket. Civil rights means you're asking Uncle Sam to treat you right. Human rights are something you were born with. Human rights are your God-given rights. Human rights are the rights that are recognized by all nations of this earth. And any time any one violates your human rights, you can take them to the world court.

Uncle Sam's hands are dripping with blood, dripping with the blood of the black man in this country. He's the earth's number-one hypocrite. He has the audacity -- yes, he has -- imagine him posing as the leader of the free world. The free world! And you over here singing "We Shall Overcome." Expand the civil-rights struggle to the level of human rights. Take it into the United Nations, where our African brothers can throw their weight on our side, where our Asian brothers can throw their weight on our side, where our Latin-American brothers can throw their weight on our side, and where 800 million Chinamen are sitting there waiting to throw their weight on our side.

Let the world know how bloody his hands are. Let the world know the hypocrisy that's practiced over here. Let it be the ballot or the bullet. Let him know that it must be the ballot or the bullet.

When you take your case to Washington, D.C., you're taking it to the criminal who's responsible; it's like running from the wolf to the fox. They're all in cahoots together. They all work political chicanery and make you look like a chump before the eyes of the world. Here you are walking around in America, getting ready to be drafted and sent abroad, like a tin soldier, and when you get over there, people ask you what are you fighting for, and you have to stick your tongue in your cheek. No, take Uncle Sam to court, take him before the world.

By ballot I only mean freedom. Don't you know -- I disagree with Lomax on this issue -- that the ballot is more important than the dollar? Can I prove it? Yes. Look in the UN. There are poor nations in the UN; yet those poor nations can get together with their voting power and keep the rich nations from making a move. They have one nation -- one vote, everyone has an equal vote. And when those brothers from Asia, and Africa and the darker parts of this earth get together, their voting power is sufficient to hold Sam in check. Or Russia in check. Or some other section of the earth in check. So, the ballot is most important.

Right now, in this country, if you and I, 22 million African-Americans -- that's what we are -- Africans who are in America. You're nothing but Africans. Nothing but Africans. In fact, you'd get farther calling yourself African instead of Negro. Africans don't catch hell. You're the only one catching hell. They don't have to pass civil-rights bills for Africans. An African can go anywhere he wants right now. All you've got to do is tie your head up. That's right, go anywhere you want. Just stop being a Negro. Change your name to Hoogagagooba. That'll show you how silly the white man is. You're dealing with a silly man. A friend of mine who's very dark put a turban on his head and went into a restaurant in Atlanta before they called themselves desegregated. He went into a white restaurant, he sat down, they served him, and he said, "What would happen if a Negro came in here? And there he's sitting, black as night, but because he had his head wrapped up the waitress looked back at him and says, "Why, there wouldn't no nigger dare come in here."

So, you're dealing with a man whose bias and prejudice are making him lose his mind, his intelligence, every day. He's frightened. He looks around and sees what's taking place on this earth, and he sees that the pendulum of time is swinging in your direction. The dark people are waking up. They're losing their fear of the white man. No place where he's fighting right now is he winning. Everywhere he's fighting, he's fighting someone your and my complexion. And they're beating him. He can't win any more. He's won his last battle. He failed to win the Korean War. He couldn't win it. He had to sign a truce. That's a loss.

Any time Uncle Sam, with all his machinery for warfare, is held to a draw by some rice eaters, he's lost the battle. He had to sign a truce. America's not supposed to sign a truce. She's supposed to be bad. But she's not bad any more. She's bad as long as she can use her hydrogen bomb, but she can't use hers for fear Russia might use hers. Russia can't use hers, for fear that Sam might use his. So, both of them are weapon- less. They can't use the weapon because each's weapon nullifies the other's. So the only place where action can take place is on the ground. And the white man can't win another war fighting on the ground. Those days are over The black man knows it, the brown man knows it, the red man knows it, and the yellow man knows it. So they engage him in guerrilla warfare. That's not his style. You've got to have heart to be a guerrilla warrior, and he hasn't got any heart. I'm telling you now.

I just want to give you a little briefing on guerrilla warfare because, before you know it, before you know it. It takes heart to be a guerrilla warrior because you're on your own. In conventional warfare you have tanks and a whole lot of other people with you to back you up -- planes over your head and all that kind of stuff. But a guerrilla is on his own. All you have is a rifle, some sneakers and a bowl of rice, and that's all you need -- and a lot of heart. The Japanese on some of those islands in the Pacific, when the American soldiers landed, one Japanese sometimes could hold the whole army off. He'd just wait until the sun went down, and when the sun went down they were all equal. He would take his little blade and slip from bush to bush, and from American to American. The white soldiers couldn't cope with that. Whenever you see a white soldier that fought in the Pacific, he has the shakes, he has a nervous condition, because they scared him to death.

The same thing happened to the French up in French Indochina. People who just a few years previously were rice farmers got together and ran the heavily-mechanized French army out of Indochina. You don't need it -- modern warfare today won't work. This is the day of the guerrilla. They did the same thing in Algeria. Algerians, who were nothing but Bedouins, took a rine and sneaked off to the hills, and de Gaulle and all of his highfalutin' war machinery couldn't defeat those guerrillas. Nowhere on this earth does the white man win in a guerrilla warfare. It's not his speed. Just as guerrilla warfare is prevailing in Asia and in parts of Africa and in parts of Latin America, you've got to be mighty naive, or you've got to play the black man cheap, if you don't think some day he's going to wake up and find that it's got to be the ballot or the bullet.

l would like to say, in closing, a few things concerning the Muslim Mosque, Inc., which we established recently in New York City. It's true we're Muslims and our religion is Islam, but we don't mix our religion with our politics and our economics and our social and civil activities -- not any more We keep our religion in our mosque. After our religious services are over, then as Muslims we become involved in political action, economic action and social and civic action. We become involved with anybody, any where, any time and in any manner that's designed to eliminate the evils, the political, economic and social evils that are afflicting the people of our community.

The political philosophy of black nationalism means that the black man should control the politics and the politicians in his own community; no more. The black man in the black community has to be re-educated into the science of politics so he will know what politics is supposed to bring him in return. Don't be throwing out any ballots. A ballot is like a bullet. You don't throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.

The political philosophy of black nationalism is being taught in the Christian church. It's being taught in the NAACP. It's being taught in CORE meetings. It's being taught in SNCC Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee meetings. It's being taught in Muslim meetings. It's being taught where nothing but atheists and agnostics come together. It's being taught everywhere. Black people are fed up with the dillydallying, pussyfooting, compromising approach that we've been using toward getting our freedom. We want freedom now, but we're not going to get it saying "We Shall Overcome." We've got to fight until we overcome.

The economic philosophy of black nationalism is pure and simple. It only means that we should control the economy of our community. Why should white people be running all the stores in our community? Why should white people be running the banks of our community? Why should the economy of our community be in the hands of the white man? Why? If a black man can't move his store into a white community, you tell me why a white man should move his store into a black community. The philosophy of black nationalism involves a re-education program in the black community in regards to economics. Our people have to be made to see that any time you take your dollar out of your community and spend it in a community where you don't live, the community where you live will get poorer and poorer, and the community where you spend your money will get richer and richer.

Then you wonder why where you live is always a ghetto or a slum area. And where you and I are concerned, not only do we lose it when we spend it out of the community, but the white man has got all our stores in the community tied up; so that though we spend it in the community, at sundown the man who runs the store takes it over across town somewhere. He's got us in a vise. So the economic philosophy of black nationalism means in every church, in every civic organization, in every fraternal order, it's time now for our people to be come conscious of the importance of controlling the economy of our community. If we own the stores, if we operate the businesses, if we try and establish some industry in our own community, then we're developing to the position where we are creating employment for our own kind. Once you gain control of the economy of your own community, then you don't have to picket and boycott and beg some cracker downtown for a job in his business.

The social philosophy of black nationalism only means that we have to get together and remove the evils, the vices, alcoholism, drug addiction, and other evils that are destroying the moral fiber of our community. We our selves have to lift the level of our community, the standard of our community to a higher level, make our own society beautiful so that we will be satisfied in our own social circles and won't be running around here trying to knock our way into a social circle where we're not wanted. So I say, in spreading a gospel such as black nationalism, it is not designed to make the black man re-evaluate the white man -- you know him already -- but to make the black man re-evaluate himself. Don't change the white man's mind -- you can't change his mind, and that whole thing about appealing to the moral conscience of America -- America's conscience is bankrupt. She lost all conscience a long time ago. Uncle Sam has no conscience.

They don't know what morals are. They don't try and eliminate an evil because it's evil, or because it's illegal, or because it's immoral; they eliminate it only when it threatens their existence. So you're wasting your time appealing to the moral conscience of a bankrupt man like Uncle Sam. If he had a conscience, he'd straighten this thing out with no more pressure being put upon him. So it is not necessary to change the white man's mind. We have to change our own mind. You can't change his mind about us. We've got to change our own minds about each other. We have to see each other with new eyes. We have to see each other as brothers and sisters. We have to come together with warmth so we can develop unity and harmony that's necessary to get this problem solved ourselves. How can we do this? How can we avoid jealousy? How can we avoid the suspicion and the divisions that exist in the community? I'll tell you how.

I have watched how Billy Graham comes into a city, spreading what he calls the gospel of Christ, which is only white nationalism. That's what he is. Billy Graham is a white nationalist; I'm a black nationalist. But since it's the natural tendency for leaders to be jealous and look upon a powerful figure like Graham with suspicion and envy, how is it possible for him to come into a city and get all the cooperation of the church leaders? Don't think because they're church leaders that they don't have weaknesses that make them envious and jealous -- no, everybody's got it. It's not an accident that when they want to choose a cardinal, as Pope I over there in Rome, they get in a closet so you can't hear them cussing and fighting and carrying on.

Billy Graham comes in preaching the gospel of Christ. He evangelizes the gospel. He stirs everybody up, but he never tries to start a church. If he came in trying to start a church, all the churches would be against him. So, he just comes in talking about Christ and tells everybody who gets Christ to go to any church where Christ is; and in this way the church cooperates with him. So we're going to take a page from his book.

Our gospel is black nationalism. We're not trying to threaten the existence of any organization, but we're spreading the gospel of black nationalism. Anywhere there's a church that is also preaching and practicing the gospel of black nationalism, join that church. If the NAACP is preaching and practicing the gospel of black nationalism, join the NAACP. If CORE is spreading and practicing the gospel of black nationalism, join CORE. Join any organization that has a gospel that's for the uplift of the black man. And when you get into it and see them pussyfooting or compromising, pull out of it because that's not black nationalism. We'll find another one.

And in this manner, the organizations will increase in number and in quantity and in quality, and by August, it is then our intention to have a black nationalist convention which will consist of delegates from all over the country who are interested in the political, economic and social philosophy of black nationalism. After these delegates convene, we will hold a seminar; we will hold discussions; we will listen to everyone. We want to hear new ideas and new solutions and new answers. And at that time, if we see fit then to form a black nationalist party, we'll form a black nationalist party. If it's necessary to form a black nationalist army, we'll form a black nationalist army. It'll be the ballot or the bullet. It'll be liberty or it'll be death.

It's time for you and me to stop sitting in this country, letting some cracker senators, Northern crackers and Southern crackers, sit there in Washington, D.C., and come to a conclusion in their mind that you and I are supposed to have civil rights. There's no white man going to tell me anything about my rights. Brothers and sisters, always remember, if it doesn't take senators and congressmen and presidential proclamations to give freedom to the white man, it is not necessary for legislation or proclamation or Supreme Court decisions to give freedom to the black man. You let that white man know, if this is a country of freedom, let it be a country of freedom; and if it's not a country of freedom, change it.

We will work with anybody, anywhere, at any time, who is genuinely interested in tackling the problem head-on, nonviolently as long as the enemy is nonviolent, but violent when the enemy gets violent. We'll work with you on the voter-registration drive, we'll work with you on rent strikes, we'll work with you on school boycotts; I don't believe in any kind of integration; I'm not even worried about it, because I know you're not going to get it anyway; you're not going to get it because you're afraid to die; you've got to be ready to die if you try and force yourself on the white man, because he'll get just as violent as those crackers in Mississippi, right here in Cleveland. But we will still work with you on the school boycotts be cause we're against a segregated school system. A segregated school system produces children who, when they graduate, graduate with crippled minds. But this does not mean that a school is segregated because it's all black. A segregated school means a school that is controlled by people who have no real interest in it whatsoever.

Let me explain what I mean. A segregated district or community is a community in which people live, but outsiders control the politics and the economy of that community. They never refer to the white section as a segregated community. It's the all-Negro section that's a segregated community. Why? The white man controls his own school, his own bank, his own economy, his own politics, his own everything, his own community; but he also controls yours. When you're under someone else's control, you're segregated. They'll always give you the lowest or the worst that there is to offer, but it doesn't mean you're segregated just because you have your own. You've got to control your own. Just like the white man has control of his, you need to control yours.

You know the best way to get rid of segregation? The white man is more afraid of separation than he is of integration. Segregation means that he puts you away from him, but not far enough for you to be out of his jurisdiction; separation means you're gone. And the white man will integrate faster than he'll let you separate. So we will work with you against the segregated school system because it's criminal, because it is absolutely destructive, in every way imaginable, to the minds of the children who have to be exposed to that type of crippling education.

Last but not least, I must say this concerning the great controversy over rifles and shotguns. The only thing that I've ever said is that in areas where the government has proven itself either unwilling or unable to defend the lives and the property of Negroes, it's time for Negroes to defend themselves. Article number two of the constitutional amendments provides you and me the right to own a rifle or a shotgun. It is constitutionally legal to own a shotgun or a rifle. This doesn't mean you're going to get a rifle and form battalions and go out looking for white folks, although you'd be within your rights -- I mean, you'd be justified; but that would be illegal and we don't do anything illegal. If the white man doesn't want the black man buying rifles and shotguns, then let the government do its job.

That's all. And don't let the white man come to you and ask you what you think about what Malcolm says -- why, you old Uncle Tom. He would never ask you if he thought you were going to say, "Amen!" No, he is making a Tom out of you." So, this doesn't mean forming rifle clubs and going out looking for people, but it is time, in 1964, if you are a man, to let that man know. If he's not going to do his job in running the government and providing you and me with the protection that our taxes are supposed to be for, since he spends all those billions for his defense budget, he certainly can't begrudge you and me spending $12 or $15 for a single-shot, or double-action. I hope you understand. Don't go out shooting people, but any time -- brothers and sisters, and especially the men in this audience; some of you wearing Congressional Medals of Honor, with shoulders this wide, chests this big, muscles that big -- any time you and I sit around and read where they bomb a church and murder in cold blood, not some grownups, but four little girls while they were praying to the same God the white man taught them to pray to, and you and I see the government go down and can't find who did it.

Why, this man -- he can find Eichmann hiding down in Argentina somewhere. Let two or three American soldiers, who are minding somebody else's business way over in South Vietnam, get killed, and he'll send battleships, sticking his nose in their business. He wanted to send troops down to Cuba and make them have what he calls free elections -- this old cracker who doesn't have free elections in his own country.

No, if you never see me another time in your life, if I die in the morning, I'll die saying one thing: the ballot or the bullet, the ballot or the bullet.

If a Negro in 1964 has to sit around and wait for some cracker senator to filibuster when it comes to the rights of black people, why, you and I should hang our heads in shame. You talk about a march on Washington in 1963, you haven't seen anything. There's some more going down in '64.

And this time they're not going like they went last year. They're not going singing ''We Shall Overcome." They're not going with white friends. They're not going with placards already painted for them. They're not going with round-trip tickets. They're going with one way tickets. And if they don't want that non-nonviolent army going down there, tell them to bring the filibuster to a halt.

The black nationalists aren't going to wait. Lyndon B. Johnson is the head of the Democratic Party. If he's for civil rights, let him go into the Senate next week and declare himself. Let him go in there right now and declare himself. Let him go in there and denounce the Southern branch of his party. Let him go in there right now and take a moral stand -- right now, not later. Tell him, don't wait until election time. If he waits too long, brothers and sisters, he will be responsible for letting a condition develop in this country which will create a climate that will bring seeds up out of the ground with vegetation on the end of them looking like something these people never dreamed of. In 1964, it's the ballot or the bullet.

Thank you.

#george floyd#ahmaudaubrey#justiceforahmaud#protest#malcolmx#georgefloyd#black lives matter#i cant breathe

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Our Own by Eddie S. Glaude Jr.

Baldwin’s understanding of the American condition cohered around a set of practices that, taken together, constitute something I will refer to throughout this book as the lie. The idea of facing the lie was always at the heart of Jimmy’s witness, because he thought that it, as opposed to our claim to the shining city on a hill, was what made America truly exceptional. The lie is more properly several sets of lies with a single purpose. If what I have called the “value gap” is the idea that in America white lives have always mattered more than the lives of others, then the lie is a broad and powerful architecture of false assumptions by which the value gap is maintained. These are the narrative assumptions that support the everyday order of American life, which means we breathe them like air. We count them as truths. We absorb them into our character. (p. 7)

***

These, then, are the twined purposes at the heart of Baldwin’s poetic vision. He is not only motivated to transform the stuff of experience into the beauty of art; as a poet he also bears witness to what he sees and what we have forgotten, calling our attention to the enduring legacies of slavery in our lives; to the impact of systemic discrimination throughout the country that has denied generations of black people access to the so-called American dream; to the willful blindness of so many white Americans to the violence that sustains it all. He laments the suffering that results from our evasions and refusals and passes judgment on what we have done and not done in order to release ourselves into the possibility of becoming different and better people. He bears witness for those who cannot because they did not survive, and he bears witness for those who survived it all, wounded and broken. (p. 40)

***

In the end, we cannot escape our beginnings: The scars on our backs and the white-knuckled grip of the lash that put them there remain in dim outline across generations and in the way we cautiously or not so cautiously move around one another. This legacy of trauma is an inheritance of sorts, an inheritance of sin that undergirds much of what we do in this country. (p. 46)

***

When we memorialize the Confederacy with monuments to Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson, what exactly are we commending? It’s never simply the military genius of a general. . . . The Confederate monuments are memorials to a way of life and a particular set of values associated with that way of life. To suggest they are not is just dishonest. The students at Princeton asked a similar question about Woodrow Wilson: What does the university’s uncritical celebration of him commend to us? Again, who and what we celebrate reflects who and what we value. This is why in moments of revolution or profound cultural shifts one of the first things people remove are symbols of the old values. Lenin’s and Stalin’s statues, for example, had to fall, but it is telling that Robert E. Lee continues to stand tall in parks across the United States—even in Charlottesville, Virginia, where Heather Heyer died. (p. 79)

***

An honest confrontation with the past had everything to do with the kinds of persons we understood ourselves to be and the kinds of people we aspired to become. Baldwin’s demand was a decidedly moral one: He wanted to free us from the shackles of a particular national story in order that we might create ourselves anew. For this to happen, white America needed to shatter the myths that secured its innocence. This required discarding the histories that trapped us in the categories of race. “People who imagine that history flatters them,” he wrote in Ebony, “are impaled on their history like a butterfly on a pin and become incapable of seeing or changing themselves, or the world.” (p. 82)

***

Even though Baldwin understood Black Power, its condemnation of white America, and its insistence on black self-determination as a reasonable and, in some ways, wholly justifiable response to the country’s betrayal of the civil rights movement, he never rejected the idea, found in this formulation, that we are much more than the categories that bind our feet. We, too, must never forget this insight.

“Color,” as he wrote in 1963, “is not a human or personal reality; it is a political reality.” Color does not say, once and for all, who we are and who we will forever be, nor does it accord anyone a different moral standing because they happen to be one color as opposed to another. But, again, Baldwin is not naïve. He understands history’s hold and the politics that make it so. As he wrote in The Fire Next Time, “as long as we in the West place on color the value that we do, we make it impossible for the great unwashed to consolidate themselves according to any other principle.” It makes all the sense in the world, then, that black people would look to the fact of their blackness as a key source of solidarity and liberation. White people make black identity politics necessary. But if we are to survive, we cannot get trapped there. (pp. 101-02)

***

Baldwin came to understand that there were some white people in America who refused to give up their commitment to the value gap. For him, we could not predicate our politics on changing their minds and souls. They had to do that for themselves. In our after times, our task, then, is not to save Trump voters—it isn’t to convince them to give up their views that white people ought to matter more than others. Our task is to build a world where such a view has no place or quarter to breathe. I am aware that this is a radical, some may even say, dangerous claim. It amounts to “throwing away” a large portion of the country, many of whom are willing to defend their positions with violence. But we cannot give in to these people. We know what the result will be, and I cannot watch another generation of black children bear the burden of that choice. (pp. 112-13)

***

To understand this is to see why the desire to distance oneself from Trump fits perfectly with the American refusal to see ourselves as we actually are. We evade historical wounds, the individual pain, and the lasting effects of it all. The lynched relative; the buried son or daughter killed at the hands of the police; the millions locked away to rot in prisons; the children languishing in failed schools; the smothering, concentrated poverty passed down from generation to generation; and the indifference to lives lived in the shadows of the American dream are generally understood as exceptions to the American story, not the rule. Blasphemous facts must be banished from view by a host of public rituals and incantations. Our gaze averted, we then congratulate ourselves on how far we have come and ruthlessly blame those in the shadows for their plight in life. Gratitude is expected. Having secured our innocence, we feel no guilt in enjoying what we have earned by our own merit, in defending our right to educate our children in the best schools and in demanding that we be judged by our ability alone. To maintain this illusion, Trump has to be seen as singular, aberrant. Otherwise, he reveals something terrible about us. But not to see yourself in Trump is to continue to lie. (pp. 173-74)

***

I have taken the title of this book from a passage in James Baldwin's last novel, Just Above My Head. In light of the collapse of the civil rights movement and the consolidation of the after times with the election of Ronald Reagan, Baldwin offered these words for those who desperately sought to imagine a way forward: “Not everything is lost. Responsibility cannot be lost, it can only be abdicated. If one refuses abdication, one begins again.” Begin again is shorthand for something Baldwin commended to the country in the latter part of his career: that we reexamine the fundamental values and commitments that shape our self-understanding, and that we look back to those beginnings not to reaffirm our greatness or to double down on myths that secure our innocence, but to see where we went wrong and how we might reimagine or re-create ourselves in light of who we initially set out to be. This requires an unflinching encounter with the lie at the heart of our history, the kind of encounter that cannot be avoided at places like the Legacy Museum.

Irony abounds. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice opened in 2018, in the middle of Donald Trump’s first term. As I have argued, Trump's election represents our after times; all that he stands for reasserts the lie in the face of demographic shifts and political change represented by Obama’s election and the activism of Black Lives Matter. Every day Trump insists on the belief that white people matter more than others in this country. He has tossed aside any pretense of a commitment to a multiracial democracy. He has attacked congressmen and women of color, even telling four congresswomen “to go back to the countries they came from”; scapegoated people seeking a better life at our borders; and appealed explicitly to white resentment. On top of the racist rhetoric, his judicial appointments and his policies around voting rights, healthcare, environmental regulations, immigration law, and education disproportionately harm communities of color. In every way imaginable, Trump has intensified the cold civil war that engulfs the country.

But to view Trump in the light of the lynching memorial in Alabama is to understand him in the grand sweep of American history: He and his ideas are not exceptional. He and the people who support him are just the latest examples of the country's ongoing betrayal, our version of “the apostles of forgetfulness” When we make Trump exceptional, we let ourselves off the hook, for he is us just as surely as the slave-owning Founding Fathers were us; as surely as Lincoln, with his talk of sending black people to Liberia, was us; as surely as Reagan was us, with his welfare queens. When we are surprised to see the reemergence of Klansmen, neo-Nazis, and other white nationalists, we reveal our willful ignorance about how our own choices make them possible. The memorial confronts both Trumpism and those who would never imagine themselves in sympathy with it, with the truth and trauma of American history. It exposes the lie for what it is and makes plain our collective complicity in reinforcing it.

In his introduction to his 1985 collection of essays, The Price of the Ticket, Baldwin noted that America had become quick to congratulate itself on the progress it had made with regards to race, and that the country's self-congratulation came with the expectation of black gratitude. (This was particularly the case with the election of the country's first black president.) As Baldwin wrote, “People who have opted to be white congratulate themselves on their generous ability to return to the slave that freedom which they never had any right to endanger, much less take away. For this dubious effort . . . they congratulate themselves and expect to be congratulated.” The expectation was that he should feel “gratitude not only that my burden is . . . being made lighter but my joy that white people are improving.”

Baldwin viewed this demand for gratitude from the vantage point of someone who had lived through and was deeply wounded by the betrayal of the black freedom movement, someone whose recollection or remembrance of that moment involved trauma. In 1979, on the eve of the election of Ronald Reagan, for example, in a short piece for Freedomways, Baldwin wrote of the difficulty of recalling the past. “Let us say that we all live through more than we can say or see. A life, in retrospect, can seem like the torrent of water opening or closing over one’s head and, in retrospect, is blurred, swift, kaleidoscopic like that. One does not wish to remember—one is perhaps not able to remember—the holding of one’s breath under water, the miracle of rising up far enough to breathe, and then, the going under again. . . .” Here Baldwin captures beautifully the cycles of the after times that illustrate how horrific the white expectation of gratitude is.

Baldwin believed the after times required that we look back in order to understand the choices we’ve made that have brought us to the moment of crisis. We don’t begin again as if there is nothing behind us or underneath our feet. We carry that history with us. In the introduction to The Price of the Ticket, Baldwin formulated his point about beginning again a bit differently. “In the church I come from,” he wrote, “we were counselled, from time to time, to do our first works over.” Here Baldwin invokes Revelations 2:5: “Consider how far you have fallen! Repent and do the things you did at first. If you do not repent, I will come to you and remove your lampstand from its place.” In the mode of poet-prophet, Baldwin called the nation, in his after times, to confront the lie of its own self-understanding and to get about the work of building a country truly based on democratic principles. As he wrote:

To do your first works over means to reexamine everything. Go back to where you started, or as far back as you can, examine all of it, travel your road again and tell the truth about it. Sing or shout or testify or keep it to yourself: but know whence you came.

��America in the generality, he argued, refused to do such a thing because the exploration itself would reveal that the price of the ticket to be here in the United States was in fact to leave behind the particulars of Europe and become white. That transformation “choked many a human being to death,” because to become white meant the subjugation of others, an act that disfigured the soul by closing off the ability to see oneself in others, and to see them in oneself. Our task, Baldwin maintained, was to understand the history of how that disfiguring of the soul happened and, in doing so, to free oneself and the country from the insidious hold of whiteness in order to become a different kind of creation—a different way of being in the world. (pp. 193-97)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author's Statement:

In entirety, this semester has brought about so much change. It seems that’s the true theme of my writing, as well as life. Everyday something changes and we barely take notice or choose to push out of mind. However, there comes those monumental times in our lives. It dismantles everything we thought we once knew about the world or about oneself. For me and many others my age, it came in the form of the transition from grade school to University. Moreover, just as much as they shape an individual, they also shape the course of history for a community. Throughout the 7 works on this page, a common theme of changes, the pressure that creates them and societal norms within the concept of change are explored. In addition, the prominence of changes can be observed within the semester's initial focus on “Revolution”.

In the segments of “Making Connections”, the prompt of choosing an interesting pieces of literature introduced that inspired me led me towards “I Too” by Langston Hughes, “Straight Outta Compton” by one of the 90s rap group NWA and “shitty First drafts” by Anne Lamott. I Too spoke to me. I read it again and again. Not because I didn't understand it the first time but because I felt it. I felt those feelings of indignation at being put out because the world canty see your worth. However, I feel that pride in knowing that the fault is not in oneself but those that shroud their eyes of the truth of black success and liberation. In addition, “Shitty First Drafts” fed my confidence and opened me up to a humanistic approach to writing that ignores the norm. Finally, “Straight Outta Compton” was a physical embodiment of the eradication of black criminality as ironically, it employs the emphasis on criminality and fearlessness. In all 3 there's a common theme of a shift from conventionally thinking. These authors and artists reached outside the box and in the meantime inspired me. All were symbols of a turning point in perception and therefore embody change.

Finally, in the segments of Essay portion, the prospects of Reconstruction , Women’s Rights as well as protest is chronicled. The first essay focuses on women’s liberation. This current society is one that seeks to justify women’s plight by saying “At least it's not as bad as before”. This is also true for the plight of the African American people today. The powers that benefit from our oppression can only thrive on the current standing. That's where protesting comes in. Why isnt that encouraged as much as voting? Both are part of the duty of every single city that claims the perks of democracy.

Remember, the very construct of this “modern” world was to keep some down by furthering the success of another group. Women, colored people, poor people are just a few groups that don't seem to fit into this mold of holding power so therefore they are disenfranchised. As you read through this portfolio, my only hope is for inspiration, Just as Langston Hughes inspired me. The reader must understand however that there is hope nonetheless because after all “They'll see how beautiful we are and be ashamed”.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The African origin of heroes, super and otherwise

July 7, 2011

by J.D. Jackson