#chun doo hwan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In light of recent events...

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Lai Dai Han (Lai Đại Hàn): The Truth that's Inconvenient for Korea (Essay)

Statue of Lai Dai Han

The 320,000 Korean troops sent to South Vietnam during the Vietnam War committed a war crime that will never be forgotten. Under the pretext of wiping out the Viet Cong in South Vietnam, they indiscriminately massacred local people and gang-raped women, causing countless children (5,000-30,000). These children are called "Lai Dai Han" (children of mixed race with Korean soldiers). They are not accepted in either Vietnam or Korea and live in discrimination.

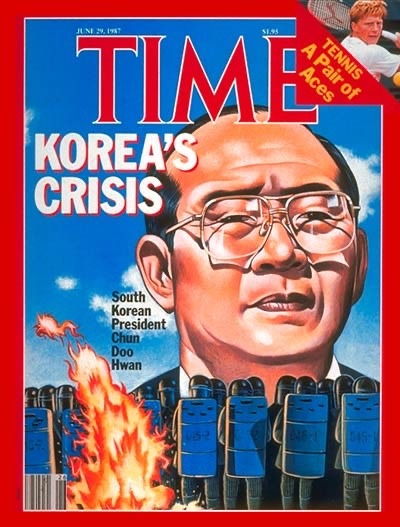

In the extreme conditions of the battlefield, the true nature of human beings is revealed, but what about the wildness of these Korean soldiers? They are no less cruel than American or Russian soldiers. In Korea, the topic of Lai Dai Han is taboo, and although there were media outlets that tried to cover it, the Veterans' Association headed by former President Chun Doo-hwan (全斗煥) suppressed it. Chun Doo-hwan was the commander of the Vietnam Expeditionary Forces. Vietnam, which wants economic assistance from Korea, does not want to touch on the Lai Dai Han.

South Korea, which has committed such evil deeds, is persistently erecting statues of comfort women around the world to criticize Japan for the "comfort women issue," which is said that the Japanese military Kidnapped Korean women and made them "sex slaves", but this is ridiculous. In the first place, the "comfort women issue" is a fabrication by the Asahi Shimbun (newspaper) of Japan, and South Korea is just taking advantage of the situation of it. In the face of the Vicious Lai Dai Han issue, South Korea has no right to criticize anything including Japan. (The Japanese military consensually employed Korean women as prostitutes. Not sex slaves.) The UK has erected in Vietnam a statue of Lai Dai Han in front of the South Korean embassy to commemorate the evil deeds. Japan should also erect a statue of Lai Dai Han next to the statue of comfort women all over the world.

Rei Morishita

2024.07.21

ライダイハン:韓国にとって都合の悪い真実(エッセイ)

ベトナム戦争の折、派遣された韓国軍32万人は、決して消えない戦争犯罪を犯している。それは南ベトナムでベトコンを掃討する名目で、現地の人を無差別に虐殺、また女性を���姦して夥しい数(5000-3万)の子供たちを生ませたことだ。この子供たちを「ライダイハン」(韓国兵との混血児)と呼ぶ。彼らはベトナムでも韓国でも受け入れらえず、差別されて生きている。

戦場という極限状態において、人間の本性があらわになるが、この韓国兵たちの荒みぶりはどうだろう。アメリカ兵、ロシア兵にも劣らない酷さだ。韓国では、ライダイハンの話題はタブーであるし、取り上げようとするマスコミはあったが、韓国大統領も務めた全斗煥を首魁とする退役軍人会が握りつぶした。全斗煥はベトナム派遣韓国軍の指揮官だった。韓国の経済的援助が欲しいベトナムも、ライダイハンには触れたくない。

こんな悪行をする韓国が、日本軍が朝鮮人女性を誘拐し「性奴隷」にしたとされる「従軍慰安婦問題」で、非難のため世界に慰安婦像をしつこく立てまくっているが、ちゃんちゃらおかしい。そもそも「従軍慰安婦問題」は日本の朝日新聞の捏造であり、それに韓国は乗っているに過ぎない。ライダイハンを前にすると、韓国がなにか非難する筋合いはない。(実際、日本軍は、合意の上で韓国人女性を売春婦として雇っていた。)イギリスは、ベトナムで、韓国大使館の前に、ライダイハン像を立て、その悪行を顕彰している。日本も従軍慰安婦像の隣に、ライダイハン像を立てるとよい。

#Lai Dai Han#Lai Đại Hàn#Korea#essay#rei morishita#Vietnam#children of mixed race with Korean soldiers#Chun Doo-hwan#全斗煥#Japan#comfort women#Asahi Shimbun#fabrication#UK#commemorate the evil deeds

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The reality revealed yesterday was better than the dark history of the past.

South Korea should remain vigilant to learn from history. Democracy can't be taken as granted. Threats to democracy don't just come from the North. In fact, as shown in the course of their history, threats came from authoritarian parties and politicians who wanted to be the next dictator.

#South Korea#martial laws#military dictatorship#democracy#Chun Doo-hwan#Coup d'état of 12·12#Park Chung Hee#Yoon Suk Yeol

0 notes

Text

2024 Watch List: Movie Edition

After what feels like a decade of not really watching any movies, I had a good movie year- 70 films, which is a little over a movie per week, mostly because I stuck to watching or rewatching older films. Went through most of Wong Kar Wai's filmography, which always leaves me dreamy and slightly perplexed and also a bit annoyed (complimentary); going bonkers over Interview with the Vampire S2 made me fall into French New Wave for a time- a longing to revisit Paris struck me enough to do something about renewing my passport- though naturally, it didn't improve my bank balance enough to think about actually visiting. Anyway, tbh, I was quite surprised that Hiroshima Mon Amour and Masculin Feminin, among others, are really all that. Sixty years later, Justine Triet's Anatomy of a Fall (2023) would have been my pick for best film at the Oscars- it made me want to return to watching movies in theatre.

Returned to the mothership (UK) via Merchant-Ivory productions and old British tv - Howard's End (1992) which I probably watched for the first time too early in my life, knocked me down and then took me out back and shot me in the head this time around. Maurice (1987) was everything Luca Guadagnino films aren't (y'all were just really flat out lying about Challengers being good); Heat & Dust (1983) made me a little angry, and also pushed me into reading A Passage to India (1924).

Closer home, Kim Jee-woon's weird and wonderful brain gave me Cobweb (2023), which was odd, stylish, darkly funny, and just an incredibly good film to watch some of Korea's top actors doing their thing (and some unexpected things- Jung Woo Sung's cameo, for example). Speaking of the new father (*sniggers meanly*) , I finally got to watch Kim Sung-su's era-defining "youth" film Beat (1997) and John Lee's A Moment to Remember (2004), two films that have defined Jung's career- loved the former, despite the bleak ending, and about half of the latter; it was at its best when it was being unselfconsciously horny- the sharp left into melo territory left me unmoved. It's crazy to me that it's Jung Woo-sung who keeps getting asked to re enact the "If you drink this, we're dating" dialogue for like twenty years, when that scene- and the movie- really belong to the luminous Son Ye jin. Shout out also to director Kim Sung-su's 12:12 The Day/ Seoul Spring(2023), a fictional retelling of the 1979 coup by Chun Doo-hwan which was oddly prescient about Events (TM) of December 2024 to the point where I actually said aloud- wait, I just saw this in a movie.

Hirokazu Kore-eda's Monster (2023) is a perfect film, 10/10 no notes; and I wept buckets watching Shoplifters (2018), but found Airdoll (2009) a bit icky, despite a bravura performance from the great Bae Doona. Andrew Haigh's All of Us Strangers (2023) was another film that had me crying- and it didn't surprise me later to find out that it was based on a Japanese novel by Taichi Yamada. There's just something about how Asian storytelling uses the supernatural that is easily identifiable, even when situated in a different culture.

Moonstruck (1987) turned out to be the rom com of the year for me- just PERFECT, god, imagine Hollywood used to know how to make romances????

Malayalam cinema continues to be the only Indian cinema worth watching (I said what I said): Kaathal: The Core (2023) and Thallumaala (2022) are very different films thematically and stylistically, and give you some idea of the range of what's on offer there, while the bigger Hindi/Telugu cinema industries continue to churn out headache inducing, morally and artistically bankrupt mega-hits. They're not the only ones, of course- why on earth does Emerald Fennell get to make movies, y'all? Saltburn (2023) was trash. Poor Things (2023) was even worse, if that were possible. And yet, I'm told we're going to get treated to MORE of the same. Love yourselves, guys, please.

I'm not sure what I'm looking forward to movie-wise next year, but I do hope to continue rediscovering the joy of cinema. Anyway, what've you all been watching this year? Tell me in the notes/ link me to your posts!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

When South Korean legislator Kim Min-seok warned in August that President Yoon Suk-yeol might be plotting to declare martial law, even the most ardent critics of Yoon were skeptical. Of course, the right-wing president was increasingly displaying authoritarian tendencies. In response to his miserably low approval rating, hovering between the high teens and low 20s, as well as mounting corruption allegations against him and his wife, Yoon ordered indiscriminate raids of the offices and residences of liberal politicians and journalists, numerous thinly supported criminal charges against opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, and ostentatious military parades.

But still, the idea that Yoon might attempt martial law and a self-coup—where an existing leader seizes dictatorial power—seemed to be too outlandish. It was seen as partisan fodder, unbecoming of a lawmaker of Kim’s stature—a respected former youth leader of the South Korean democracy movement that ended the military dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan in 1987. South Korea had not seen martial law since its democratic transition, although a declaration of martial law remained a theoretical possibility in case of a wartime emergency in a hypothetical clash with North Korea.

Then it happened. At 10:23 p.m. local time on Dec. 3, Yoon called an unscheduled press conference. In a six-minute statement, Yoon announced that he was declaring an emergency martial law, claiming that the opposition Democratic Party made the National Assembly “a monster trying to destroy liberal democracy” because the liberal party had brought 22 impeachments against officials in his administration and threatened to slash its discretionary budget. Yoon branded his political opponents are “pro-Pyongyang anti-state forces,” in the same rhetoric that South Korea’s military dictators had used to justify their rule.

Within an hour, Gen. Park An-soo was appointed as the commander of the Martial Law Command, which decreed that all political activities in national and local legislatures were prohibited, all media were subject to the control of the Martial Law Command, and public gatherings and rallies were prohibited. Soon, armored cars and helicopters began emerging in the streets of Seoul.

South Korean news anchors reporting the announcements were visibly shaking because they knew, as did most South Koreans, what could be in store. The last time martial law was declared in South Korea was in 1979, in the waning days of Park Chung-hee’s dictatorship that later gave way to Chun’s. In that martial law period, from October 1979 to January 1981, Chun’s paratroopers massacred hundreds of protesters, perhaps thousands, in the southwestern city of Gwangju.

The mass murders in the aftermath of the Gwangju Uprising became one of the defining moments of modern South Korean history, memorialized in the novel Human Acts by Han Kang, who won the Nobel Prize in literature in October and is due to give her acceptance speech next week. But in 2024, most South Koreans had regarded the massacre as a distant historical event, a tragic but old incident that their country had put past. The public watched the news in shock as armored cars and helicopters were heading to the National Assembly, where lawmakers had the ability to end martial law by a majority vote.

Fortunately, history did not repeat itself—in part because, as with everything he has done, Yoon executed the autogolpe with clownish incompetence. Aspiring authoritarians around the world have long had an established playbook for coups: TV broadcast controlled, the internet jammed, opposition leaders arrested, and checkpoints set up around the city.

The martial law declaration aspired to all of these possibilities, especially control of the media. Yet none of those things happened on the night of Dec. 3. TV cameras roamed freely near the National Assembly Hall, while liberal leaders exhorted the public via social media to protest against Yoon’s power grab. Squads were reportedly deployed to arrest key opposition leaders but were too slow to stop them. Soldiers were reluctant to use force, letting themselves be pushed back by unarmed protesters.

Although details are still emerging as of this writing (around 24 hours since the martial law declaration), it appears that Yoon’s self-coup attempt was so clumsy because the president could not balance the need to keep his plan secret and the need to get the requite buy-ins from key players. Reportedly, it was Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun who suggested declaring martial law. But Kim could only muster a small segment of the military to follow his orders; most of the military and the police remained in their posts. Yoon apparently had no buy-in from conservatives either, as People Power Party leader Han Dong-hoon and Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon quickly denounced the coup attempt.

Nevertheless, there were many moments where just one wrong turn could have resulted in chaos and bloodbath. Under the law, the National Assembly can end martial law with a majority vote—but of course, that assumes that the legislators are able to vote. The declaration, completely illegally, forbade the National Assembly from gathering, and armed soldiers were dispatched to patrol outside the Assembly Hall, as helicopters equipped with machine guns hovered over them.

Somehow, the South Korean legislators managed. The protesters led a tense standoff against the special forces deployed to the legislature, blocking the soldiers and armored cars while opening a path for lawmakers to enter the building. Democratic Party spokesperson Ahn Gwi-ryeong wrestled an armed soldier with her bare hands before going into the building. Lee, the Democratic leader, showed surprising athleticism for a 60-year-old as he hopped over the walls to avoid the soldiers in front of the building—while livestreaming a video of himself to boot. Thankfully, not a shot was fired.

Once in the building, the lawmakers and their aides barricaded the entrance and opened the legislative session at 12:49 a.m. Assembly Speaker Woo Won-shik emphasized that proper parliamentary procedure must be followed to leave no doubt about the result, even as paratroopers broke a window to enter the building and legislative aides pushed them back with fire extinguishers and cellphone flashes.

At 1:01 a.m., after 12 agonizing minutes of typing up the bill and submitting it in accordance with the parliamentary procedure, the 190 out of 300 Assembly members who could manage to enter the hall, including 18 legislators of Yoon’s own party, unanimously voted to end martial law. After a few moments of hesitation, the helicopters and armored cars, then the soldiers, began leaving the hall. Even after the vote, there remained a question whether Yoon would honor the National Assembly vote. The legislators remained in the hall, fearing that Yoon might redeploy the military or declare martial law once again. But at 4:27 a.m., the defeated and humiliated Yoon held a press conference to announce that he would lift martial law.

As of this writing, the situation remains fluid. But it does not appear likely that Yoon will be able to finish out the remainder of his term, which runs until 2027. The Democratic Party demanded that Yoon resign immediately or face impeachment proceedings, which require a two-thirds majority of the 300-seat Assembly. Although Yoon’s party holds a slim buffer with 108 legislators, the president’s coup attempt is likely to be enough to peel off at least eight lawmakers, since 18 of them already voted to end martial law.

Yoon may choose to resign rather than to face the ignominy—though he might still be prosecuted. South Korea has an illustrious history of prosecuting and jailing its former presidents, including two out of the past three presidents, Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye, both conservatives.

However it ends, Yoon’s presidency will serve as a reminder of the resilience of South Korean democracy. South Korea’s first martial law situation in more than four decades ended in approximately six hours, based on a parliamentary vote, with no casualties and not a single shot fired. One errant bullet could have changed the course of history, but the overwhelming weight of democratic norms, physically manifest in a protesting public and the parliamentarians calmly voting in the face of ongoing assault, stayed the hands of the soldiers.

On the other hand, it is another embarrassment for South Korean conservatives, who miraculously came back from the impeachment of their last president, Park, in 2017 to recapture the presidency in a narrow win in 2022 based mostly on grievances about high housing costs. This latest episode will do little to help right-wing leaders shed their reputation as the descendants of military dictators with a streak of authoritarianism that could flare up at the first sign of trouble. The so-called reasonable conservatives, the smaller cadre of right-leaning moderates who think vainly that they can work within the system to change it, will once again have to impeach their own president.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Shock of Sudden South Korean Martial Law

What a surreal and unsettling night!

Last night, South Korean President Yoon Seok-yeol shocked the nation by declaring martial law without warning. His administration moved to ban “all political activities,” including protests and political party meetings, while placing “all news media and publications… under the control of martial law command.” The military surrounded the National Assembly building and attempted to arrest parliamentary leaders, even those from the president’s own party.

For context, President Yoon is deeply unpopular. Both he and his administration—including his wife—have been under investigation for corruption by the opposition-controlled National Assembly, led by the Korean Democratic Party. In his speech last night, he stated (as translated by the New York Times):

Our National Assembly has become a den of criminals and is attempting to paralyze the nation’s judicial administration system through legislative dictatorship and overthrow the liberal democracy system. The National Assembly, which should be the foundation of liberal democracy, has become a monster that collapses the liberal democracy system. Now, Korea is in a precarious situation where it would not be surprising if it collapsed immediately.

Dear citizens, I declare emergency martial law to defend the free Republic of Korea from the threats of North Korean communist forces and to eradicate the shameless pro-North Korean anti-state forces that are plundering the freedom and happiness of our people and to protect the free constitutional order.

South Korea may face its share of political problems, but it is far from being on the brink of collapse. President Yoon’s speech was nothing short of melodramatic, filled with exaggerated rhetoric that seemed completely detached from reality, fabricating a crisis where none existed.

He accused the legislature of undermining democracy, claiming their actions—such as blocking his policy agenda, investigating corruption within his administration, and impeaching his ministers—were politically motivated and destroying the nation. However, the legislature was democratically elected earlier this year, with the opposition party securing a decisive victory. His claim of “legislative dictatorship” is utterly ridiculous.

Fortunately, a true tragedy was averted when the National Assembly, undeterred by the looming threat of arrest, convened in a remarkable display of resolve. In a unanimous decision, they overturned the martial law declaration, exercising their constitutional authority under the nation's provisions for such an extreme measure. The fact that the military respected and complied with this constitutional order is a testament to the resilience of South Korea’s contemporary democratic institutions.

The last time martial law was declared in South Korea was in 1980, during the rule of Chun Doo-hwan. Chun invoked martial law to cement his grip on power following a coup, transforming his presidency into a military dictatorship. This came in the wake of the assassination of Park Chung-hee, the previous dictator, who had also employed martial law to seize power and establish his own military regime.

It was a night that could have spiraled into chaos, but instead, the democratic government regained control and prevented a likely dictatorship.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amergency Act 19 (긴급조치 19호)

It is a satirical 2002 South Korean film about a government act that prohibits popular music and passed in response to a number of musicians being elected to government elsewhere in the world. It is notable for the numerous K-pop stars that make appearances in the film.

Directed by: Kim Tae-gyu

Written by: Kim Sung-dong and Lee Seung-guk

Produced by: Song Chang-yong

Starring:

Kim Jang-hoon as himself, Hong Kyung-min as himself, Gong Hyo-jin as Min-ji, Noh Joo-hyun as the Chief Secretary and Min-ji's father and Ju Yeong-hun as himself

List of Cameos:

Besides the main cast, there are a number of actors and K-pop singers and groups who make cameos in the film as themselves.

They are:

Kim Sung-oh as soldier 2 at Vinyl House, Baby V.O.X., Brown Eyes, CAN, Chakra, Click-B, Fin.K.L, Harisu, Kangta, Koyote, NRG, Shinhwa, UN, and Psy

Plot:

Troubled by the growing worldwide trend of pop singers being elected as politicians, the President of South Korea orders his Chief Secretary to invoke "Emergency Act 19". This new law criminalizes all pop singers, and the army is deployed on the streets of Seoul to round them up. One pop star, Hong Kyung-min, is arrested while performing a concert, but his angry fans mob the soldiers as they try to take him away. The Chief Secretary's teenage daughter, Min-ji, is amongst the fans, and leading her idol to safety gives him her phone number. Kyung-min finally makes a getaway with his friend and fellow pop star, Kim Jang-hoon.

Once Jang-hoon and Kyung-min become fully aware of the situation, they contact Min-ji, who is able to hide the two singers in a secret location. The Chief Secretary finds out that his daughter is working against him, and when she refuses to give them up, he has false news reports created, accusing the singers of sexually assaulting minors. Meanwhile, more pop stars are rounded up by the authorities who are now aided by another singer, Ju Yeong-hun, who decides to betray his friends in order to save himself.

Angered by their tarnished reputations, Jang-hoon and Kyung-min acquire a gun from a shady weapons dealer, and with Min-ji's help they are able to take the Chief Secretary and his staff hostage. They take their captives to the park, where Min-ji has organized a mass demonstration with her friends and other music fans. The army arrive on the scene and engage the demonstrators in conflict, finally capturing Jang-hoon and Kyung-min. The Chief Secretary is able to walk free in all the chaos, but he is appalled by the violence and orders the fighting to stop, convincing the President to repeal the emergency act and restoring peace.

I couldn't find this movie with subs anywhere. I usually watch kdramas but found it on YouTube in 2 parts without eng subs.

If anyone knows where I could watch this movie fully with eng subs would be very helpful.

youtube

(Part 1 above and Part 2 below)

youtube

This movie is based on events that happened in South Korea during the 1970s and 1980s with censorship during the Park Chung Hee Presidency (1961-1979) and Chun Doo Hwan Presidency (1980-1988).

This blog explains a bit about how Seotaji combatted censorship after the 1980s.

More about the censorship during the 1980s in South Korea.

This blog is about the evolution of Korean music in the 70s to the 80s with censorship

The wiki about the Amergency Act 19 (긴급조치 19호) movie.

Should probably go into more detail about this topic, but it gets very long and can be very confusing, and I would rather explain this in my Korean music history on male and female groups.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

⋆˙⟡ recensione: io ci sarò - kyung-sook shin

«Ogni tanto mi convinco che la giovinezza dovrebbe arrivare alla fine della vita».

Una telefonata all’alba da una persona con cui non ha rapporti da otto anni. È così che la scrittrice Jeong Yun si sveglia un giorno: lo scambio è breve, ma quelle poche parole la scuotono profondamente.

“Il Professor Yun è all’ospedale”.

Si risvegliano così i ricordi della gioventù sopiti da tempo nella sua memoria: i visi che sembrava aver dimenticato ricompaiono agli occhi e le conversazioni con persone che non sono più nella sua vita rimbombano nelle orecchie. E così Jeong Yun ci porta con lei nella sua giovinezza, raccontandoci tutti i momenti che la hanno così profondamente segnata.

Sono tre giovani che si incontrano per caso in un’aula universitaria di Seul a essere i protagonisti di questo romanzo, sullo sfondo le proteste studentesche che hanno smosso la Corea del Sud negli anni ’80 durante la dittatura di Chun Doo-Hwan. Un ragazzo che è in prima fila nei cortei, una ragazza che scappa dalla campagna per perdersi nella metropoli coreana e una che nasconde le mani agli occhi indiscreti degli altri: questo il trio che in poco tempo, e per caso, stringe un legame speciale. Basta un momento, una giornata particolare in cui le vite dei tre ragazzi si incontrano nello stesso posto nello stesso attimo, per creare un sodalizio che segnerà per sempre la vita di ognuno.

Le loro storie si intrecciano, ciascuno di loro porta un fardello che ne contraddistingue il carattere e che con il tempo condividono con gli altri, cercando in qualche modo di non sprofondare sotto il dolore del proprio passato. Si immagina un futuro privo di tensioni e di sofferenze, un futuro non definito temporalmente in cui “un giorno” si potrà essere liberi di vivere in tranquillità, senza affondare nel mare tormentoso delle insicurezze personali e delle violenze militari. Un futuro in cui il trio si pensa comunque insieme, l’uno a sostegno dell’altro. Tuttavia il futuro immaginato non si rivela altro che un pio desiderio, perché i sensi di colpa, i rimpianti e le vuote promesse dipingono le pagine di questo romanzo, componendo un quadro tanto doloroso quanto spietatamente reale della gioventù e della fragilità dei rapporti umani. I protagonisti sembrano inconsapevolmente consapevoli di questo aspetto inesorabile della vita e quasi per combatterlo indirizzano l’uno all’altro una frase ricorrente: “Non dimentichiamo questo giorno”; un vano e febbrile tentativo di sottrarre dal fluire del tempo un istante effimero, come se fosse possibile salvare nella memoria un attimo di vita nello stesso modo in cui si scatta una fotografia.

Tuttavia, alla fine del libro la protagonista Jeong Yun, immersa nuovamente nella sua quotidianità, riesce a ritrovare un barlume di speranza: nonostante l’allontanamento, i legami non scompaiono e le persone possono continuare a vivere con noi grazie alle nostre esperienze. D’altra parte, anche il titolo coreano originale, 어디선가 나를 찾는 전화벨이 울리고 vuole esprimere questo sentimento di speranza: "dovunque io sia, c’è un telefono che squilla e che mi cerca". E Jeong Yun alza sempre la cornetta del telefono per rispondere, perché alla fine nessun rapporto muore veramente. E alla persona che sta dall'altro capo della linea sarà sempre pronta a dire: "Io ci sarò".

Mars.

#recensione#book review#book blog#books and reading#reading#bookworm#libri#lettura#citazione libro#leggere#libridaleggere#leggere libri#citazioni libri#frasi libri#citazione#letteratura#citazioni letterarie#letteraturacoreana#ilcaffeletterariodimars

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Good morning or good night, everyone. I need some advice regarding old Korean actors and actresses who can portray a grandpa and a grandma. Could you pretty please help me?

Um Aing-ran (1936) Korean.

Kim Young-ok (1937) Korean.

Kim Yong-rim (1940) Korean.

Kim Hye-ja (1941) Korean.

Kang Boo-ja (1941) Korean.

Na Moon-hee (1941) Korean.

Park Jeong-ja (1942) Korean.

Ban Hyo-jung (1942) Korean.

Sunwoo Yong-nyeo (1945) Korean.

Youn Yuh-jung (1947) Korean.

Jung Jae-soon (1947) Korean.

Lee Hyo-choon (1950) Korean.

Go Doo-shim (!951) Korean.

Yoon Mi-ra (1951) Korean.

Yang Hee-kyung (1954) Korean.

Moon Sook (1954) Korean.

Kim Hae-sook (1955) Korean.

Ye Soo-jung (1955) Korean.

Lee Kyung-jin (1956) Korean.

Kim Bo-yeon (1957) Korean.

Kim Hye-ok (1958) Korean.

Sunwoo Eun-sook (1959) Korean.

Shin Shin-ae (1959) Korean.

Im Ye-jin (1960) Korean.

Cha Hwa-yeon (1960) Korean.

Choi Min-sik (1962) Korean.

and:

Lee Soon-jae (1934) Korean.

Shin Goo (1936) Korean.

Lee Ho-jae (1941) Korean.

Jeon Moo-song (1941) Korean.

Park In-hwan (1945) Korean.

Jang Hang-sun (1947) Korean.

Baek Yoon-sik (1947) Korean.

Lee Jang-hee (1947) Korean.

Jung Dong-hwan (1949) Korean.

Yoon Joo-sang (1949) Korean.

Lee Young-ha (1950) Korean.

Ahn Sung-ki (1952) Korean.

Lee Deok-hwa (1952) Korean.

Jang Gwang (1952) Korean.

Jeon Gook-hwan (1952) Korean.

Lee Kye-in (1952) Korean.

Do Gyeong Lee (1953 Korean.

Moon Sung-keun (1953) Korean.

Kim Chang-wan (1954) Korean.

Gi Ju-bong (1955) Korean.

Park Jin-yeong (1955) Korean.

Shin Cheol-jin (1956) Korean.

Yoo Dong-geun (1956) Korean.

Choi Jung-woo (1957) Korean.

Kim Kap-soo (1957) Korean.

Song Seung-hwan (1957) Korean.

Park Sang-won (1959) Korean.

Kim Yon-ja (1959) Korean.

Lee Geung-young (1960) Korean.

Chun Ho-jin (1960) Korean.

Kim Byeong-ok (1960) Korean.

I hope this helps! ✨

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Final Major Project - Thoughts 16

Protest Songs

Among social movements that have an associated body of songs are the abolition movement, prohibition, women's suffrage, the labour movement, the human rights movement, civil rights, the Native American rights movement, the Jewish rights movement, disability rights, the anti-war movement and 1960s counterculture, art repatriation, opposition towards blood diamonds, abortion rights, the feminist movement, the sexual revolution, the LGBT rights movement, animal rights movement, vegetarianism and veganism, gun rights, legalisation of marijuana and environmentalism.

Martin Luther King Jr. described the freedom songs this way: "They invigorate the movement in a most significant way... these freedom songs serve to give unity to a movement."

EXAMPLE IN EAST-ASIA

China

Chinese-Korean Cui Jian's 1986 song "Nothing to My Name" was popular with protesters in Tiananmen Square.

Chinese singer Li Zhi made references to the Tiananmen Square massacre in his songs and were subsequently banned from China in 2019. Three years later, during the anti-lockdown protests in China, this was used as a protest song across YouTube.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong rock band Beyond's "Boundless Oceans Vast Skies" (1993) and "Glory Days" (光輝歲月) (1990) have been considered as protest anthems in various social movements.

During the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, Les Misérables' "Do You Hear The People Sing" (1980) and Thomas dgx yhl's "Glory to Hong Kong" (2019) were sung in support of the movement. The latter has been widely adopted as the anthem of these protests, with some even regarding it as the "national anthem of Hong Kong".

Philippines

From the revolutionary songs of the Katipunan to the songs being sung by the New People's Army, Filipino protest music deals with poverty, oppression as well as anti-imperialism and independence. A typical example was during the American era, as Jose Corazon de Jesus created a well-known protest song entitled "Bayan Ko", which calls for redeeming the nation against oppression, mainly colonialism, and also became popular as a song against the Marcos regime.

During the 1960s, Filipino protest music became aligned with the ideas of Communism as well as of revolution. The protest song "Ang Linyang Masa" came from Mao Zedong and his Mass Line and "Papuri sa Pag-aaral" was from Bertolt Brecht. These songs, although Filipinized, rose to become another part of Filipino protest music known as Revolutionary songs that became popular during protests and campaign struggles.

South Korea

See also: Music of South Korea and Korean protest songs

Commonly, protest songs in South Korea are known as Minjung Gayo (Korean: 민중 가요, literally "People's song"), and the genre of protest songs is called "Norae Undong", translating to the literal meaning "song movement". The starting point of Korean protest songs was the music culture of Korean students movements around 1970.[66] It was common in the 1970s~1980s, especially before and after of the June Democracy Movement in 1987, and associated with against the military governments of presidents Park Chung Hee and Chun Doo Hwan reflecting the will of crowd and voices of criticism of the day. From the middle of the 1990s, following the democratisation of South Korea, Korean protest songs have lost their popularity.

Taiwan

"Island's Sunrise" (Chinese: 島嶼天光) is the theme song of 2014 Sunflower Student Movement in Taiwan. Also, the theme song of Lan Ling Wang TV drama series Into The Array Song (Chinese: 入陣曲), sung by Mayday, expressed all the social and political controversies during Taiwan under the president Ma Ying-jeou administration.

Thailand

See also: Phleng phuea chiwit

In Thailand, protest songs are known as Phleng phuea chiwit ("songs for life"), a music genre that originated in the '70s, by famous artists such as Caravan, Carabao, Pongthep Kradonchamnan and Pongsit Kamphee.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traditions in transition: cinematic perspectives on the modernization of post-war societies (4/4)

Before concluding this four-part series, I want to examine how Lee Chang-dong’s "Peppermint Candy" (1999) portrays post-war South Korea’s transition from a military dictatorship to democracy. The film not only encapsulates the essence of societal transformation but also serves as a poignant reminder of history's lasting impact on individual lives.

As usual, you can find my previous articles HERE.

Part 3. Peppermint Candy (박하사탕, Lee Chang-dong, 1999)

youtube

Peppermint Candy's Trailer

Directed by Lee Chang-dong, an influential auteur of Korea’s New Wave of cinema, Peppermint Candy (1999) reflects on South Korea’s turbulent journey to democratization and modernity in the decades after the Korean War. Through its non-linear structure and powerful performances, Lee Chang-dong's film delves deep into themes of lost innocence, the impact of political and social change, and the haunting effects of guilt and regret. By revealing Yong-ho’s life in reverse, Lee Chang-dong juxtaposes personal memories with historical events, emphasizing the interplay between individual trauma and collective memory. In this way, he also effectively highlights how past experiences shape present identities.

The film begins with the suicide of the protagonist, Kim Yong-ho, who throws himself in front of an oncoming train. This haunting act serves as the catalyst for a reflective journey into the events that led to his untimely death. We see him in the 1990s as a broken middle-aged man, jobless due to the economic crisis and struggling with the consequences of his actions. His relationships deteriorate, including his failed marriage. Further back, he is depicted as a corrupt police officer and a disillusioned soldier witnessing the violent suppression of the “Gwangju Uprising”, also known as the “Gwangju Democratization Movement”. A tragic and pivotal incident in South Korean history that took place from May 18 to 27, 1980.

Peppermint Candy, Lee Chang-dong, 1999

Triggered by widespread discontent with the authoritarian regime of Chun Doo-Hwan, thousands of students and civilians in the city of Gwangju protested against martial law and demanded democratic reforms. The military’s brutal response led to the death of hundreds of protesters and left a deep scar on the national consciousness. To this day, the Gwangju uprising remains a significant historical event, reflecting the nation’s turbulent journey towards democratization and the enduring impact of state violence on collective memory.

Peppermint Candy, Lee Chang-dong, 1999

Peppermint Candy critiques political oppression and the abuse of power by depicting this military and police brutality. Its protagonist, Kim Yong-ho, is profoundly affected by the 1980 events. In a heart-wrenching scene, he accidently kills a high school girl during the chaos of the uprising, a moment that haunts him throughout the film. The title “Peppermint Candy” serves as a powerful symbol of innocence and nostalgia, contrasting sharply with Yong-ho’s despair. Initially, we see him as an idealistic young man with dreams and aspirations. However, as he becomes embroiled in the corrupt and violent system, his innocence is gradually stripped away, leaving him a hollow shell of his former self. Ultimately, Lee Chang-dong paints a harrowing portrait of a man haunted by his actions and struggling to reconcile the past with the present. Yong-ho’s identity crisis mirrors the broader societal identity crisis during South Korea’s transition.

Thank you for accompanying me on this journey. Your support has been truly invaluable.

Ruth Sarfati

#Lee Chang-dong#Peppermint candy#박하사탕#korean cinema#post war#modernity#democratization#trauma#ruth sarfati

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ajeosshi has been wanting to see 서울의봄 (English title: 12.12 - The Day. Why?? The Korean title 'Seoul Spring' was so much better). It's a film about the 1979 military coup by Chun Doo Hwan, following the assassination of dictator Park Chung Hee. In the film he is, for reasons unknown to me (libel avoidance??) renamed Chun Doo Gwang, but nonetheless, the film makers spent a lot of time and money making lead actor Hwang Jung Min look just like the real Chun Doo Hwan 🤷♀️

Yesterday was the Ajeosshi's day off so he insisted on going to see it, even though he was sick. Like, can barely stay standing without looking utterly miserable sick. We should not have bothered. Since the Ajeosshi likes this genre, I have seen many Korean political/historical thrillers based on actual events (mostly starring the same few actors, heh) and this was by far the worst. The actors are skilled people and the technical folks had a lot of fun making Seoul look like it did in 1979, but it was just so formulaic and BORING. Eeeeendless scenes of men in military uniforms smoking and shouting at each other. Repeated split screens to show us how the enemy was listening in on the good guys. Crass attempts to make 'heroic' moments. Yawn. Why drag it out? Everyone in Korea knows exactly how it will end.

The role of Jung Woo Sung is to be heroic. Because that's apparently the only role he ever plays. (Seriously, can someone point me at anything where he played against type?). Dull.

The (very brief) role of women was to serve the tea and worry about your man. If you get to say a line, it must be delivered in a soft, childish voice :/

I got a good workout from all my clock watching and eye rolling.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

June Uprisings from Korea to California YK Hong / June 09, 2025 at 06:17PM/ https://ift.tt/GFnE3kz image/video: https://ift.tt/F0PmslO As we witness the uprisings and resistance in Los Angeles, as well as around the United States Empire, I wanted to bring in some history from Korea in what is now known as the June Uprisings. On this day in 1987, students around south Korea gathered in preparation for mass nationwide protests and something happened that would change the entire course of history of Korea. Two weeks prior, university students occupied the United States Information Services cultural center building in Seoul. They were demanding reparations and an apology from the United States and south Korean governments for their role in the 1980 Gwangju Massacre. They were also demanding an end to the U.S.-supported authoritarian dictatorship of Chun Doo Hwan. [Students occupying the USIC in Seoul in 1987] This type of image should be familiar to you by now; students taking over buildings to demand accountability from their government’s atrocious actions. [Student in Columbia University occupying the campus building they renamed Hind’s Hall”] Two weeks after that building takeover on June 9, 1987, students were met with Chun Doo Hwan’s brutal military forces. A 21-year-old student from Yonsei University named Lee Han Yeol, was struck in the head with a tear gas canister. [Lee Han Yeol, head bleeding from being hit by a police tear gas canister, being held up by a fellow student] That June would later be known as the June Uprisings or the June Democracy Movement. This is an image from that June in 1987 in the streets of Korea: [Tear gas spread across the streets and people in Seoul in June 1987] But we are witnessing images just like this happening in the U.S. Empire right now, and have been for some time. That image of Lee Han Yeol collapsed, bleeding, and held by a fellow student, captured the hearts and spirits of the Korean movement fighting for democracy and against authoritarianism and the dictatorship. While he was hospitalized during those June uprisings, the students often raised him up as a symbol of the cause. [A banner with an illustration of Lee Han Yeol, and a photo of Park Jong Chul, a student leader who was killed by police interrogators] A few days after the regime capitulated to the people's demands in July, Lee Han Yeol died of the attack wounds. 1.6 million people showed up to his national funeral. [National funeral for Lee Han Yeol and Park Jong Chul] It was those June uprisings from June 10th to 29th in 1987, that changed the entire way that Korea's political system functions. The people’s uprisings forced an end to the military regime and moved to establish the current Republic of Korea (ROK) we have today, with a direct presidential election system. This is the very same election system that was used this past June in 2025 to elect the new president Lee Jae Myung after Yoon Suk Yeol’s martial law declaration and impeachment. That is the power of protest and resistance by the people. The June uprisings. Korea is still fighting off U.S. imperialism and occupation. Those inside of the United Stated are doing the same right now, too. Support the people's protest and resistance. Be a part of the people's protest and resistance. We can change the entire course of history and literally bring down regimes. Liberation Toolbox is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my labor and work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

0 notes

Text

Author Han Kang won this year’s Nobel Prize in literature, becoming the first Asian woman to do so and the second Nobel laureate from South Korea. A woman being the first Korean author to win the prize is a breath of fresh air, especially as the poet Ko Un, long considered the most likely South Korean to win the prize, was exposed as a serial sexual harasser in 2018 by South Korea’s own Me Too movement.

Han’s win is also a triumph of South Korea’s fierce and resilient democracy. South Korea’s first Nobel laureate was Kim Dae-jung, an activist-turned-president who won the peace prize in 2000 for his efforts to restore democracy in the country and improve relations with North Korea. Han’s win echoes Kim’s path. Although Han initially gained international fame through her 2007 novel The Vegetarian, which won the 2016 International Booker Prize, her profile reached new heights with subsequent novels that delved into South Korea’s tortuous modern history: Human Acts was about the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, where hundreds of protesters were murdered by the dictatorship, and We Do Not Part was about the Jeju Massacre of the late 1940s by then-President Syngman Rhee, South Korea’s first autocrat.

Han’s Nobel Prize is a nod of recognition for the South Korean people’s struggle for freedom and democracy against the dictatorship that ruled the country for nearly five decades and still casts a shadow on Korean politics to this day.

Both Kim and Han are from South Joella province, the region that suffered the most under South Korea’s military dictators. Both gained renown through their connection to the 1980 Gwangju Uprising—Kim as a leader of the democracy movement that called attention to the massacre, and Han as the author of Human Acts, which examines the massacre from various perspectives, including an amateur mortician cleaning the bodies of the dead, a censored author, a survivor with post-traumatic stress disorder, and the dead themselves.

Han is part of a transformative generation of both political heroism and artistic talent. Han enrolled in Yonsei University in 1989, just two years after the death of Yonsei student activist Lee Han-yeol—the event that led to the fall of the Chun Doo-hwan dictatorship and South Korea’s transition to democracy. One year ahead of Han at Yonsei was Bong Joon-ho, a student activist who would go on to become an Oscar-winning director with movies such as Parasite and Snowpiercer, both sharp criticisms of capitalism. One year after Han at Seoul National University across town was Hwang Dong-hyuk, who would later win an Emmy Award as the director of Squid Game, a global hit TV series that also highlighted inequality in South Korea.

Though working in different mediums, Han, Bong, and Hwang were all forged in the crucible of South Korea’s tumultuous 1980s and ’90s. In those two decades, the country saw a brutal massacre and an authoritarian government that reveled in witch-hunting communists and the use of torture. Then the dictatorship fell, leading to electoral democracy, the Olympics, and a flowering of youth culture that sowed the seeds for the global popularity of K-pop and Korean dramas. But greater wealth and freedom soon gave way to hyper-competitive capitalism, inequality, and new uncertainties, causing some to pine for the simpler days of the past.

The works of South Korea’s democracy generation are resonating globally because, in the rhymes of history, today’s world resembles the South Korea that Han, Bong, and Hwang saw in their formative years. War and mass murder rage on, with their horrors felt more intimately than ever. Liberal democracy is barely holding on, with the masses willingly submitting to clownish authoritarianism. The world might be wealthier than before, but the small improvement in material conditions is cold comfort to those who lose out in the economic rat race. By looking back on their experiences, Han, Bong, and Hwang created works of art that ask painfully relevant questions for today’s world.

Han’s relentless focus on the violation of bodily integrity is what sets her apart from her predecessors and peers. Other giants of South Korean literature also dealt with the country’s tumultuous modern history, with authors like Jo Jeong-rae and Park Kyong-ni producing epic novels that vividly recount the decades of colonialism, war, and dictatorship. But Han distinguishes herself by drawing the connection of those decades to the effect on one’s body—something extremely personal.

The protagonist for The Vegetarian, for example, is an ordinary woman named Young-hye who suddenly finds meat disgusting, repelled by the implied violence in the food. In the face of subtle and overt violence committed by her husband’s family who cannot understand her decision, she slowly transforms herself into a tree. The Vegetarian gained popularity in South Korea with the rise of toxic misogyny among young men that fueled South Korean politics’ rightward turn—a trend that is now emerging in many parts of the world.

Han’s subsequent works widen the circle of violence from patriarchy to state violence, but her focus on bodily integrity remains the same. Human Acts opens with a stark image of massacred bodies piled on like meat at a butcher shop and one of the protagonists desperately trying to hold back the intestines from spilling out of them. The image is brutal, but not gratuitous—it is an image that must be confronted as reality, just like the horrific images of destruction in Ukraine or dead children in Gaza.

Softly but meticulously, Han’s works examine how social structures—as intimate as an oppressive family, or as distant as the dictatorship government across the sea—can cause such raw and exquisite pain. In doing so, Han asks the thorny but necessary questions for today. What must be done about all this pain? How can the world remain so cold and unmoved in the sight of such suffering? Having seen such suffering, how do we live with ourselves while maintaining human dignity, without drowning in self-hate and survivors’ guilt? Through masterful presentation of these questions, Han elevated the challenges that South Korea’s democracy generation has confronted for decades to issues for the whole world.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

ICYMI: Professor Seo Kyung-deok protests Chun Doo-hwan merchandise sale on Taobao - Chosunbiz || News link Courtesy of BusyBusinessPromotions.com - Increase Sales with Affordable SEO and Automated Marketing Like This Click Here http://dlvr.it/TKybJC

0 notes