#cincinnati streets

Text

Cincinnati Surrendered To The Automobile When Jaywalking Was Outlawed

How many Cincinnatians subscribed to Popular Mechanics magazine in 1912? And how many of those subscribers recognized, in the September issue, a tiny article on Page 414 that laid out the future of the Queen City? It all seemed so innocent:

“The city pedestrian who cares not for traffic regulations at street corners, but strays all over the street, crossing in the middle of the block, or attempting to save time by choosing a diagonal route across a street intersection instead of adhering to the regular crossing, is designated as a ‘jay walker’ in Kansas City. Kansas City recently adopted a new ordinance for the control of foot traffic as well as vehicles, and ‘jay walking’ is to be prevented as rigidly as ‘jay driving.’”

That squib appeared adjacent to another brief item on how the brand-new town of Speedway, Indiana allowed only motorized vehicles on its streets, banning anything pulled by horses. In combination, the two articles sounded the death knell for a way of life that had existed for millennia.

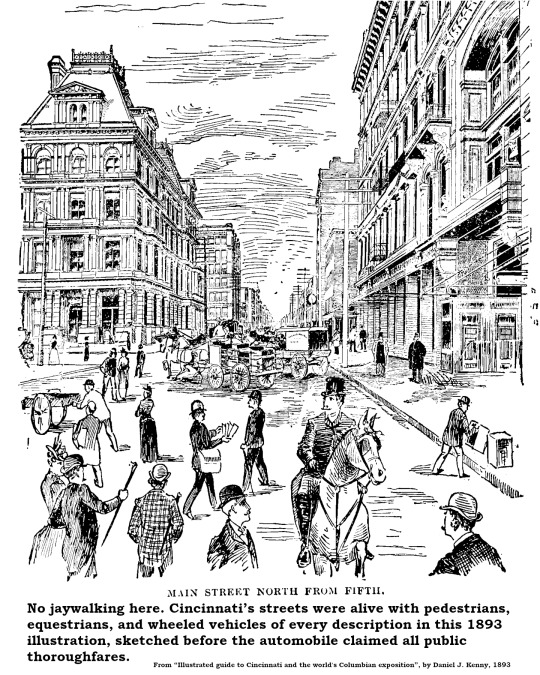

Look at the illustrations that grace the old books about Cincinnati. There is no such thing as jaywalking. The streets were owned and enjoyed by the people. Pedestrians share the road with wheeled vehicles, crossing wherever convenient, even stopping in the middle of the street to chat. Horse-drawn carriages and wagons hauled passengers and freight. Men pulling handcarts and pushing wheelbarrows dodge the throng. The only motorized vehicles were the electric street cars, and they were confined to their tracks.

During election season, Cincinnati’s streets filled with torchlit political parades. On at least one occasion, a parade filled Vine Street from Fourth Street to McMicken with chanting men waving flaming brands, lighting the clouds above with a rosy glow. When any dignitary showed up in town, they were expected to speechify from their hotel balcony and people thronged the street below, halting traffic as they cheered. People crossing the street from any direction weren’t “jay walking.” They were just “walking.” The automobile changed all that.

Horse-drawn vehicles and electric streetcars killed a fair number of people, but the motor car quickly notched more than a hundred fatalities and many more injuries every year. Local media often blamed the victims. The Cincinnati Post [8 January 1916] piled on:

“Fourth-st. is the mecca of Cincinnati’s jay walkers. Most of the jay-walking is done between Vine and Race-sts. The other day we counted 20 persons crossing the street at different points at one time – and none was using a cross-walk. Fortunately accidents are rare on this street because of the extreme care exercised by autoists.”

It appears not to have occurred to the writer that this behavior, just five years previous, would have been considered normal.

The hammer landed in 1917. Cincinnati joined the ranks of other auto-infested cities that criminalized jaywalking. The new law went into effect in May of that year, restricting automobiles to no more than 8 miles per hour in the business district and 15 miles per hour in residential districts. For the first time, pedestrians were restricted to sidewalks and crosswalks. Pedestrians – literally – fought the new law. According to the Post [23 May 1917]:

“Theodore Mitchell, 38, agent, 631 Maple-av, is the first person to be arrested on a charge of jay-walking since the new traffic ordinance went into effect. Traffic Patrolman [Edward] Schraffenberger charged Mitchell attempting to make a short cut at Fifth and Walnut streets. When reminded of his mistake, Mitchell became angry, Schraffenberger said. Mitchell, charged with disorderly conduct and violating the traffic ordinance, was cited to appear in court Thursday.”

If you’d asked the cops, however, they would unanimously aver that the chief violators were women. The Post [21 May 1917] quoted Police Lieutenant Charles Wolsefer:

“The women are awful. They just don’t pay any attention at all. Just take a look at them crossing on Race-st.”

The reporter did so, and counted 48 jaywalkers, of whom 37 were women. A few days later, another Post reporter followed another policeman on patrol who confronted 25 jaywalkers, of which only two were men.

Among the first arrested was Miss Ella Bright of 538 Howell Avenue, Clifton, a teacher at Woodward High School. Miss Bright did not care for the attitude of the city policeman who accosted her. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer [7 June 1917]:

“She declared she had been upbraided unduly by an officer because she crossed the street in a manner which was a violation of the traffic laws after alighting from a street car.”

In August of that year, Mrs. John Mongan, 4217 Glenway Avenue, Price Hill, was arrested for striking a police officer who grabbed her arm as she executed a “Dutch Cut” (diagonal jaywalking) across the intersection at Sixth & Race.

Former U.S. President William Howard Taft, then on the law faculty at Yale, was visiting his hometown that year and blithely jogged across Sixth Street near Main, only to be corralled by Officer Joseph Schindler, who gave the law professor a little legal lesson.

The Post even enlisted its “boy reporter,” 12-year-old Freddy Printz, to test the city’s ability to enforce the new jaywalking regulations. On 7 July 1917, Freddy reported his fruitless attempts to get bawled out by a police officer. Despite blatantly jaywalking at five different locations, he only earned a polite reprimand from one officer.

While the local constabulary was doing their best to enforce the new laws, the automobiles were merciless. On 21 May 1918, the Post reported on the 25th traffic fatality of the year. The victim, a 12-year-old girl, was the twelfth child killed by an automobile that year.

Curiously, although Cincinnati outlawed jaywalking, the city had omitted one very important detail that might have contributed to compliance with the new law. A letter signed only “Chicagoan” appeared in the Post on 13 June 1917. The writer suggested that, like other cities attempting to get pedestrians to cross at intersections, Cincinnati should assist pedestrians by painting white lines on the street to mark approved pedestrian crossing paths. Cincinnati’s mandatory crosswalks were unmarked!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Walnut Street’ 2022,

Archival digital print (35.5 x 47”)

Part of ‘PENUMBRA’ Series by Ian Strange for the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, USA.

#art#sculpture#lightingart#ian strange#penumbra#walnut street#usa#cincinnati#surreal#starnge#mystery#mysterious#overexposed#nonlight#nondark#reflective material

937 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bones and All

Luca Guadagnino. 2022

Apartment

2921 Marshall Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45220, USA

See in map

See in imdb

#luca guadagnino#bones and all#taylor russell#timothée chalamet#cincinnati#ohio#united states#cannibalism#movie#cinema#road movie#film#location#google maps#street view#2022

95 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, Emma! What are your top Ten all-time favorite TV shows? 😀

Hi! And it’s Anya, not Emma :). And these are in no particular order, as always

Blue Bloods

Hill Street Blues

Magnum PI

The Brokenwood Mysteries

Lewis

Midsomer Murders

That 70s Show

Full House

WKRP in Cincinnati

Dick Van Dyke Show

#favorite tv shows#Blue Bloods#hill street blues#magnum pi#the brokenwood mysteries#Lewis#midsomer murders#that 70s show#Full House#wkrp in cincinnati#the dick van dyke show#thank you for asking#thanks for the ask!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

(4/24/24) far out

#aesthetic#photography#35mm film#film photography#vintage aesthetic#cincinnati#cincinnati ohio#street photography#city photography

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cincinnati, July 2024.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

[You're taking a step out of Cincinnati, and you're walking into something completely different. Passed many pleasant hours]

#s21e06 one street wonders#guy fieri#guyfieri#diners drive-ins and dives#many pleasant hours#step#cincinnati#something

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funeral Home

#photo taken by me#photography#photo by me#black and white#photographers on tumblr#funeral#streetphotography#street photography#cincinnati

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

#poll#starsky and hutch#Streets of San Francisco#wkrp in cincinnati#Adam 12#twin peaks#MASH#the monkees#the man from uncle#radio shows

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cincinnati, OH by Ron Himebaugh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oxford street fair, 1912

Stunt dog leaping from ladder, south side of East High Street between Main Street and Poplar Street

Greater Cincinnati Memory Project

Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library

#dogs#stunt dogs#diving dogs#oxford street fair#cincinnati memory project#cincinnati and hamilton county public library

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Lost Chapter From Cincinnati’s Irish History: The Sad Saga Of Dublin Street

“If ugliness were a cardinal virtue, angels might abide in Dublin Street.”

Cincinnati Commercial Tribune

21 July 1849

When the ghost of Ginger Ryan appeared one night in 1903, Dublin Street, long neglected and criminally abused, was already doomed. Ginger, or James, as he was known to the local priest, had worked as an express man when he was alive. He delivered things by horse-drawn wagon. When he wasn’t working, Ginger was fighting. Sometimes he got into brawls while he was working. Ginger Ryan was the very embodiment of Dublin Street, so it was no surprise when residents of that woebegone lane claimed they saw Ginger’s ghost wandering around in the chill October dusk. Ginger’s ghost never spoke and eventually ceased its nocturnal visits.

As the name suggests, Dublin Street was a gathering place for Cincinnati’s Irish population. The street offered shelter throughout the time when “No Irish Need Apply” signs decorated many Cincinnati storefronts. Barred from all but the most menial occupations, many Dublin Street residents turned to crime. The infamous Nuttle Gang, Irish through and through, congregated here. Descriptions were rarely inspiring. Here is the Enquirer [23 November 1877]:

“Dublin street is a sort of nickname given to a hole in the line of Lock street extended north. It is thickly studded with houses whose tops scarcely reach to the level of the streets now filled in around it. The houses are principally old, weather-beaten frames, with rickety stairs and fences and general squalor to correspond.”

Despite its unsavory reputation, Dublin Street remains one of Cincinnati’s mysteries. It was a street, but it was also an informal district. “Dublin Street” was a catch-all term for the area just east of Bucktown where the poor Irish lived. It is intriguing that Cincinnati’s city directories, which include lists of every street in the city, make no mention of Dublin Street. That absence might imply that Dublin Street had not been dedicated or officially accepted by the city, and yet as early as 1845 the city appropriated funds to grade and pave Dublin Street.

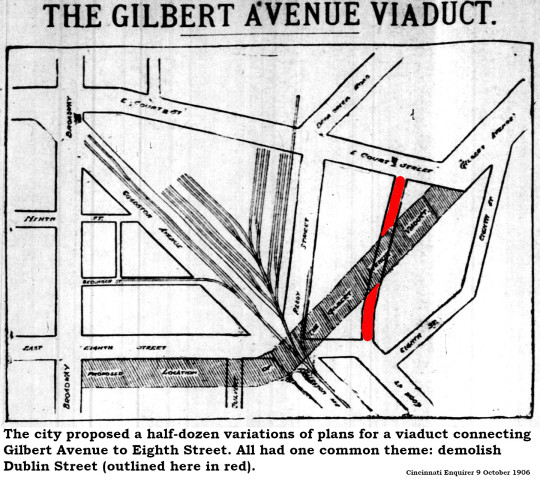

It was hardly worth the expense. Dublin Street proper was a narrow alley crammed into a ravine running from the intersection of Lock and Eighth streets to the intersection of Court Street and Gilbert Avenue. Don’t bother trying to find it on a map. The whole area has been bulldozed and covered with a web of highway ramps. As it extended northeasterly, Dublin Street also descended into Deer Creek Valley, the old “Bloody Run” once bathed by the effusions from slaughterhouses upstream. When it rained, Dublin Street became a cesspool. The Enquirer [24 May 1871] opined:

“The Board of Health would do well to visit Dublin street and Gilbert avenue. There is about four feet of filthy gutter-water standing in the street, and the residents have to dam it out of their houses.”

It is unlikely the Health Department took the newspaper’s advice. No one wanted to “visit” Dublin Street and those people forced to do so, such as officers of the court, barely escaped to tell the tale. The Cincinnati Times-Star [22 November 1911] recalled one episode:

“Court Officer John Thomas had his troubles on old Dublin street, too. He recalls a time when he was called upon to arrest a youth named Thorp on a charge of theft. The boy cried and in a moment the street was filled with excited men and women. Thomas had to hold the boy and fight the crowd back. Gradually he fought his way to Gilbert avenue and dragged the youth up the hill while sticks and stones were showered upon him.”

As the anecdote implies, the northern end of Dublin Street, where it met Gilbert Avenue, was a hill, made steeper by every improvement to Gilbert as the main route to tony Walnut Hills. Eventually, Dublin Street ended in an embankment that acted as a dam, pooling rainwater and sewage downhill from Gilbert’s finely paved thoroughfare. The Enquirer [31 May 1871] reports the effects of one storm:

“The water rose rapidly on Dublin street, flooding the floors of most of the houses on a level with the street to the depth of ten or twelve inches, and pouring in torrents down into the basements in the rear, which are used by the poor residents in this locality for kitchens and sleeping-rooms.”

A pioneering sociologist, Wallace E. Miller, reported on his inspection of Dublin Street, part of a comprehensive look at the city’s “tenement districts.” According to the Enquirer [15 March 1902]:

“This district,” says Prof. Miller, “is popularly known as ‘Dublin Street,’ partly because of the predominance there of people of Irish extraction. The ground is very low. The drainage is very poor, indeed. The street is never dry. The houses for the most part are frame buildings that are not kept up to the standard either of comfort or appearance. The surroundings are not conducive to health either in summer or winter.”

When Dublin Street residents appealed to the city for relief, they were met with undisguised scorn. After years of requests for some sort of attention, whether a set of stairs to climb up to Gilbert Avenue, or more capacious culverts to drain pooled floodwaters, Dublin Street residents asked for an embankment to keep the Gilbert Avenue hill from sliding into their back yards. City Councilman William E. Patterson even accused Dublin Street grocer Florence McCarthy of theft because he had rebuilt his house on stilts to avoid the flooding. According to the Enquirer [22 June 1890] Councilman Patterson laughed:

“McCarthy, you’re a robber. Here you shove up a house on sticks and then ask me to have the city slide a lot under it. You’re the first man I ever saw that would steal dirt. I’ll not vote for it.”

What the city eventually did vote for was a viaduct to connect the downtown to Gilbert Avenue. It took years to decide on the route and to condemn properties along the way, and to agree on the contractor, but every alternative concurred on one item: Dublin Street would be wiped from the map. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune [17 July 1909] exposed the city’s ulterior motive:

“It has been decided to condemn all the property in Dublin street, although all of it is not needed. The part not needed will be used for a park or a playground, it is said.”

When Dublin Street disappeared, there was no record of anyone shedding a tear. There is, today, a park in the general vicinity of the old Dublin Street. It’s for dogs.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Carew Tower was added to the register of National Historic Landmarks on April 19, 1994.

#Carew Tower#National Historic Landmarks#19 April 1994#anniversary#USA#441 Vine Street#Cincinnati#Ohio#Midwestern USA#Art Deco#façade#W.W. Ahlschlager & Associates#Delano & Aldrich#tourist attraction#detail#downtown#original photography#summer 2016#vacation#travel#exterior

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bones and All

Luca Guadagnino. 2022

University

Zimmer Hall, 315 College Dr, Cincinnati, OH 45219, USA

See in map

See in imdb

#luca guadagnino#bones and all#taylor russell#cannibal#reading#book#university#brick#cincinnati#ohio#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#2022

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

seventh street near vine street

#aesthetic#photography#35mm film#film photography#vintage aesthetic#cincinnati ohio#canon photography#ohio#street photography#digital photography#photographers on tumblr

10 notes

·

View notes