#contemporary hollywood cinema

Text

Meshes of the Afternoon

Maya Deren, 1943

#maya deren#short film#old hollywood#black and white#surreal#dream world#avant garde#cinema#surrealism#contemporary art#women filmmakers#eldrich horror#eerie#strange#dreamlike#meshes of the afternoon#classic film

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

67-Charlize Theron. POP Art de ACQUA LUNA.

En los cielos del arte hemos recorrido el vuelo del águila. Ahora, bajamos a la calle y sentimos el murmullo de lo cotidiano.

(Artistas ACQUA LUNA)

Art in heaven we have come flying eagle.Now, we drove down the street and feel the buzz of everyday life.

#charlize theron#pop art#painting#saatchi art#acqua luna#art collectors#art for sale#andy warhol#cinema#hollywood#portrait#art contemporain#art international#art america#art europe#art oceania#decoration#artists on tumblr#contemporary art#google

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Propaganda

Vyjayanthimala (Madhumati, Amrapali, Sangam, Devdas)—Strong contender for /the/ OG queen of Indian cinema for over 2 straight decades. Her Filmfare Lifetime Achievement Award came not a moment too soon with 62 movies under her belt. Singer, dancer, actor, and also has the most expressive set of eyes known to man

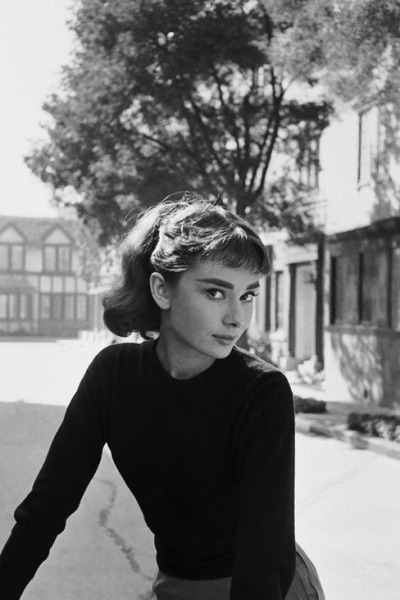

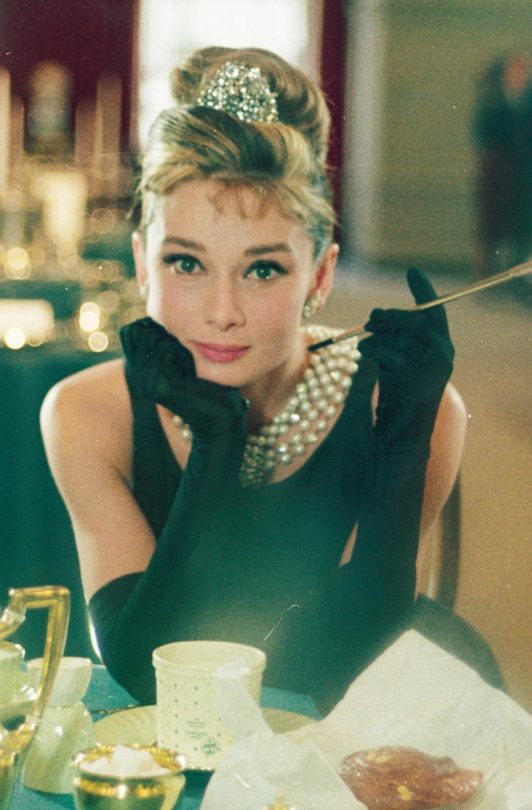

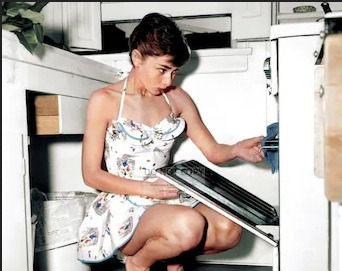

Audrey Hepburn (My Fair Lady, Sabrina, Roman Holiday)—Growing up, Audrey Hepburn desperately wanting to be a professional ballerina, but she was starved during WWII and couldn't pursue her dream due to the effects of malnourishment. After she was cast in Roman Holiday, she skyrocketed to fame, and appeared in classics like My Fair Lady and Breakfast at Tiffany's. She's gorgeous, and mixes humor and class in all of her performances. After the majority of her acting career came to close, she became a UNICEF ambassador.

This is round 6 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Vyjayanthimala:

Linked gifset

Linked gifset 2

Linked gifset 3

Linked gifset 4

Linked gifset 5

Linked gifset 6

Audrey Hepburn:

"She may be a wispy, thin little thing, but when you see that girl, you know you're really in the presence of something. In that league there's only ever been Garbo, and the other Hepburn, and maybe Bergman. It's a rare quality, but boy, do you know when you've found it." - Billy Wilder

Raised money for the resistance in nazi occupied Hungary. Became a humanitarian after retiring. Two very sexy things to do!

where to begin......... i wont her so bad. i literally dont know what to say.

My dude. The big doe eyes, the cheekbones, the voice. The flawless way she carried herself. She was never in a movie where she wasn't drop dead gorgeous. Oh, also the fact she raised funds against the Nazis doing BALLET and she won the Presidential Medal of Freedom for her humanitarian work.

"It’s as if she dropped out of the sky into the ’50s, half wood-nymph, half princess, and then disappeared in her golden coach, wearing her glass slippers and leaving no footprints." - Molly Haskell

"All I want for Christmas is to make another movie with Audrey Hepburn." - Cary Grant

I know people nowadays are probably sick of seeing her with all the beauty and fashion merch around that depicts her and/or Marilyn Monroe but she is considered a classic Hollywood beauty for a reason. Ironically in her day she was more of the alternative beauty when compared to many of her contemporaries. She always came off with such elegance and grace, and she was so charming. Apparently she was a delight to work with considering how many of her co-stars had wonderful things to say about her. Outside of her beauty and acting ability she was immensely kind. She helped raise funds for the Dutch resistance during WWII by putting on underground dance performances as well as volunteering at hospitals and other small things to help the resistance. During her Hollywood career and later years she worked with UNICEF a lot. Just an all around beautiful person both inside and out.

youtube

No one could wear clothes in this era like she could. She was every major designer's favorite star and as such her films are time capsules of high fashion at the time. But beyond that, she had such an elegance in her screen presence that belied a broad range of ability. From a naive princess, to a confused widow, to a loving and mischievous daughter, she could play it all.

Look at that woman's neck. Don't you want to bite it?

417 notes

·

View notes

Text

racism in Nintendo 2: electric boogaloo

hello and welcome back it is i, once more. to talk about the elephant in the room that has reappeared in the release of the totk designs. a suspiciously green elephant i might say

this is of course about ganon

i have made a few posts before about ganon - about how it's not anti-racist to 'redeem' his role as an all-evil villain by sexualising him; about the fan response to the first totk trailer and the rehydrated ganondorf trend; and how other characters (namely link) do not get the same treatment that ganon gets for similar design features.

what i want to give today is a more straightforward explanation of 1. why it is bad that ganon is green (yes, it is in fact bad) and 2. the orientalism inherent in his totk design. i know a lot of people find him hot, and might become defensive that i'm pointing out features that they enjoy. the fact of the matter is that the sexualisation of totk ganon is done by deliberately playing upon erotic orientalist tropes and this is something that shouldn't be ignored for personal comfort.

so to start. the green skin. im going to quote an article called Greenface: Exploring green skin in contemporary Hollywood cinema by Brady Hammond, which can be summed up by the arguement in the

"article [is] that as overtly racist cinematic depictions associated with real-world skin colors – particularly black skin – have decreased, Hollywood cinema has relocated those tropes onto green skin."

and I agree. I've talked about coding before in relation to loz, and it is no stretch to consider that a character can be representative of some particular demographic(s) without replicating their features in their entirety.

Without doubt it is straightforward to say that ganon represents a brown or black man. The gerudo are heavily inspired by the SWANA region, and not to mention that most of the gerudo indeed have a brown skin tone. botw having lighter and darker skinned gerudo is still representative of the SWANA region and the variety of looks we have there.

and thus coding done with ganon's design - intentional or otherwise - cannot escape the racial implications that ganon is very clearly a brown or black man. which means negative coding that coincides with preexisting racist coding and racial stereotypes will carry those same racist undertones. none of it is undermined by that nintendo is a Japanese company or that this is a fictional world in a video game. deliberate design choices made by real people can't be absolved from racism when it's convenient

to start:

"David Batchelor states that ‘color has been the object of extreme prejudice in Western culture’. This prejudice, he argues, manifests itself by either dismissing color outright as ‘superficial’ or by denigrating it and ‘[making it] out to be the property of some “foreign” body – usually the feminine, the oriental, the primitive, the infantile, the vulgar, the queer or the pathological’."

and

"More importantly, given the ability of the cinema screen to render fantastic spaces and colors it is necessary to consider how characters are represented when they feature an unnatural or even impossible skin color."

the gerudo have always had an orientalist lens laid over them. ganon has always had strong animalistic associations, and has appeared non-human a number of times. this was fine before nintendo retconned him to specifically be a brown man from a group that are explicitly human in the same way that hylians are human and other round-eared people in the loz franchise are human. it is racist to seperate the gerudo exclusively from other human groups as having explicitly non-human characteristics given their prolific role as the first group of brown humans in tloz, and the most foreign and exoticized group of humans.

to give ganon green skin is thusly, a way that implicitly denies his humanity. and it becomes pointed when this primitive and animalistic coding occurs most frequently to the brown man villain. now that totk revived ganon as a humaoid it becomes more pointed that he's denied the same human skintone of the rest of the gerudo, and it's quite frankly upsetting to see this happen and to be glossed over.

more specifically. green has preexisting racist associations for black and brown characters specifically. that is because green has long been used in media to depict the racialised other by linking them with real world negative racist stereotypes. an example given in the article "in Star Trek (1966-1969) when an alien woman of the Orion race dances. Her skin is an emerald green and she is both hyper-feminine and an alien Other." not commented upon but which is more evidence to the racial stereotyping of green skin is that the orion woman is depicted in a distinctly orientalist manner: with a hypersexualized outfit and routine that is reminiscent of belly dancer fantasies. the low light, setting choices, and recurring theme of the slave women dancing provocatively plays upon the western imaginations of the Harem.

as you can see:

other examples of the green other include orcs (with their own swath of racial stereotypes), the grinch, aliens, gremlins, goblins, etc. what often occurs is that green characters are concurrently linked to ethnic stereotypes through coding that is brought together in the fantasy realm by their green skin. that coding may include racism, orientalism, xenophobia, antisemitism, anti-indigenous stereotypes or so on. it is clear that ganon representing a brown/black man brings with it negative coding in the game as the only villain, his animalistic associations, his domineering violence that stands apart from the primarily female gerudo, and as the racialised other. this coding would still exist if he was not green. but it is an affront to dignity to remove the humanity of a brown man by also making him green.

if i have not yet lost you then to wrap up: the fetishizing other. as established with his coding, ganon's humanity is put into question with his design, and he can be linked to the SWANA region. evocative of a harem is the only (violent and dangerous) man from a group of women who are hidden away, and is explicitly a danger to both them and western/hylian rule and ideology.

His imagery is paired with similar design choices made for the gerudo women to sexualize him and invoke imagery of the sexy orient, the beast that can be tamed, and so on. This is done primarily with his torso being bare while he wears gold jewelry, in a way almost reminiscent of chains or cuffs. brown and black men are fetishized through sexualising them as erotic beasts, which is clear to the image that totk ganon's design presents. even the toe rings play into this - as a practice with a long history in India as worn by married women (and men, in Tamil culture).

much akin to the face veil for women, brown and black men are often sexualised through (usually gold) jewelry. specifically (like with the veil) the juxtaposition between their lack of full covering (bare torso is most common) and the abundance of ornamental jewelry. it shows their body as this exotic, decorated prize, where their nudity is highlighted by what they do wear. [this remains true despite the real world groups in the swana region that have traditionally topless outfits for men. that sort of respectful and researched depiction of cultural outfits it not what is happening here, clearly]

[note: there are clear elements of ganon's outfit that have a noticeable influence of the samurai, and the outfit is not exclusively made from one source. however the features of the outfit that i am mentioning, the jewellery, toe ring, even the trousers, are not part of the samurai aspect. it is in conjunction with the other coding and features that ganon having a bare torso becomes anything more significant]

which all goes to say that totk ganon's design continues Nintendo's legacy of racism. He is simultaneously dehumanised and sexualised - which only serves to further his dehumanisation. I am not going to ask for or address his role as a villain, what I want is just a modicum of respect.

#totk ganon#gerudo#gerudo tag#moya's loz thoughts#legend of salty#txt#if u don't know me im not open to feedback but block me and move on with your life

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

A collection of profiles, interviews, and definitive cinematic images, Cinema Her Way: Visionary Female Directors in Their Own Words by Marya E. Gates, due for publication in 2025 by Rizzoli, shines a light on female filmmakers who have made an indelible impact on the landscape of contemporary film, from art house and independent award-winners to Hollywood blockbusters and beyond.

Sign Up Here

#cinema her way#52 films by women#directed by women#female directors#women in film#book#author#film book#meryl streep#she-devil#she devil#susan seidelman

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

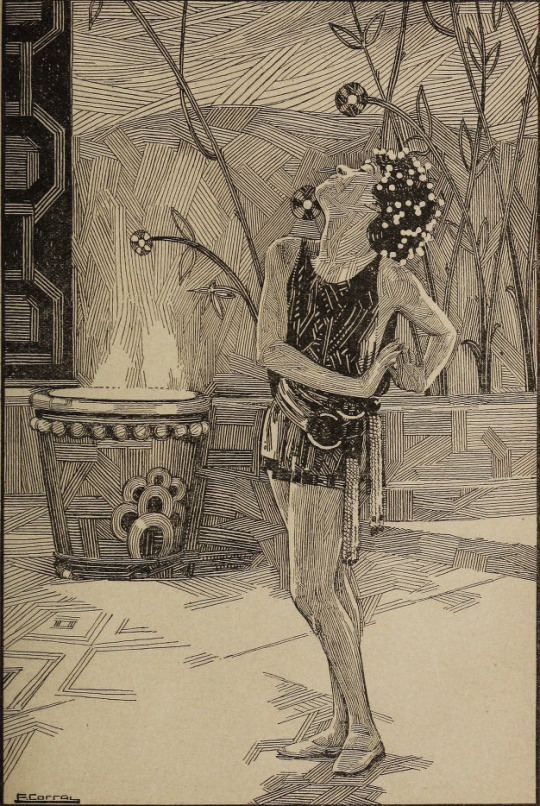

Cosplay the Classics: Nazimova in Salomé (1922)—Part 1

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Importance of Being Peter: Nazimova’s Take on Wilde

With over two decades of professional acting experience behind her (six on the “shadow stage” of silent cinema), Alla Nazimova went independent. She was one of the highest paid stars in Hollywood at the start of 1922 when her contract with Metro ended. Almost exclusively using her own savings, Nazimova founded a new production company and immediately got to work on two films that reflected both a deep understanding of her own fan base and a faith in the American filmgoer’s appreciation for art.

Discourse around these films and their productions that have emerged in the century since their release are often peppered with over-simplifications or a lack of perspective. Focus is understandably placed on Salomé, as her first project, A Doll’s House (1922), has not survived. In part one of this series, I plan to contextualize Nazimova’s decision to commit Wilde’s drama to celluloid and examine the details of the adaptation. Then, in part two, I will cover how Salomé (and A Doll’s House) fits into the industry trends and the emergent studio system in the early 1920s.

While the full essay and more photos are available below the jump, you may find it easier to read (formatting-wise) on the wordpress site. Either way, I hope you enjoy the read!

Wilde’s Salomé: The Basics

Salomé was a one-act drama written by Oscar Wilde. In a creative challenge to himself, Salomé was one of Wilde’s first plays and he chose to write in French, which he did not have as complete a mastery of as of English. Wilde was directly inspired by the Flaubert story “Herodias,” which was, in turn, inspired by the short story which appears twice in the New Testament. The play was later translated into English and published with illustrations by artist Aubrey Beardsley. Wilde’s play was the basis of the opera of the same name by Richard Strauss. While both the opera and the play had been staged numerous times across Europe and in New York before Nazimova’s adaptation, Strauss’ opera was the main reference point for the story in the popular imagination of the time. The success of Strauss’ opera led to the popularization of the Dance of the Seven Veils and the accepted interpretation of the character as a classic femme fatale.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

Nazimova’s Salomé: The Basics

When Nazimova announced her production of Salomé, she did so assured that she and Natacha Rambova, her art director, had a unique and creatively compelling interpretation of the story to warrant adaptation. Nazimova was not only the star and producer of Salomé, she adapted it from its source herself under her pen name Peter M. Winters. (Cheekily, contemporary interviews and profiles joke that “Peter” is one of her common nicknames.) Charles Bryant, credited as director, was as much the director of the film as he was Nazimova’s husband, which is to say, he is not known to have contributed much at all. It’s now accepted fact that Bryant acted as a professional beard (Bryant and Nazimova were also never legally married). The choice to credit Bryant was to offset the heat Nazimova was getting in the press at the time for “taking on too much.” Having Bryant’s name in the credits was a protective measure. Charles Van Enger was a talented, up-and-coming cinematographer who had been recommended to Nazimova following the inadequate cinematography of her Metro films.

Rambova was in charge of the art direction, set designs, costumes, and makeup. Nazimova and Rambova had become close artistic collaborators after Nazimova hired Rambova to design the fantasy sequence for her film Billions (1920, presumed lost). [You can learn more about Rambova’s career here.] Both women valued their work above all else. Both were convinced that film could be art. Both had the gumption to believe that they could make a lasting mark on cinema’s recognition as a legitimate medium of artistic expression.* (Spoiler: even though Salomé was not an unqualified box-office success, they were right.)

Photo of the Salomé crew from Exhibitors Herald, 29 April 1922. Original caption: Nazimova ordered this picture taken that she might be reminded of the real pleasure encountered in every stage of the production of “Salome.” Top, left to right: Monroe Bennett, laboratory; Charles Bryant, director; Mildred Early, secretary; John DePalma, assistant director. Second row: Sam Zimbalist, cutter; Natacha Rambova, art director; Charles J. Van Enger, cameraman; the star; R. W. McFarland, manager. Front row: Neal Jack, electrician; Paul Ivano, cameraman; Lewis Wilson, cameraman.

Nazimova’s independence was at least partly spurred on by feeling creatively bereft from her work at Metro. In a 1926 interview with Adela Rogers St. Johns, Nazimova said:

“You asked me why I made ‘Salome.’ Well—’Salome’ was a purgative. […] It seems impossible now that I should ever have been asked to play such parts as ‘The Heart of a Child’ and ‘Billions.’ But I was. And instead of saying, ‘No. I will not play such trash. I will not play roles so wholely [sic] unsuited to me in every way,’ I went on and played them because of my contract, and they ruined me.

“WORSE than that, they [made] me sick with myself. So I did ‘Salome’ as a purgative. I wanted something so different, so fanciful, so artistic, that it would take the taste out of my mouth. ‘Salome’ was my protest against cheap realism. Maybe it was a mistake. But—I had to do it. It was not a mistake for me, myself.”

Given that Nazimova now had full creative freedom, outside of the confines of the Hollywood film factory, why were A Doll’s House and Salomé the first works she gravitated towards?

Initially, Nazimova had conceived of a “repertoire” concept for her productions: one shorter production (A Doll’s House) and one feature-length production (Salomé), which could be distributed and exhibited together. Once production was underway for ADH, Nazimova instead chose to make it a feature. The reasons for this decision that I found in contemporary sources are purely creative, but I don’t think it’s too much of a presumption that this may have been a financial choice, as profits from ADH (which unfortunately wouldn’t materialize—more on that in part two!) could have been cycled into Salomé’s production.

Ibsen was not popular source material for the silent screen, but Nazimova’s name and career was forever tied to the playwright as she is considered the actress who brought Ibsen to the US. (Minnie Maddern Fiske starred in a production of Hedda Gabbler in the US before Nazimova, however it failed to raise the profile of the writer.) Nazimova’s stage productions of Ibsen’s work proved that there was an audience for it in the US—both in New York and on tour. Superficially, ADH might seem like a risky proposition, but Nazimova had good reason to believe it had both artistic and box office potential. (Again, I’ll delve into why it might not have found its audience in part two.)

Nazimova as Nora in A Doll’s House

Though ADH is now lost, we know from surviving materials that Nazimova understood that by 1922 The New Woman archetype was already becoming passé to the post-war/post-pandemic generation of young women. Nazimova endeavored to translate the play in a way that would resonate with 1920s American womanhood. (How well she succeeded is lost to time unless we are lucky enough to recover a copy of the film.) Likewise, Nazimova approached her adaptation of Salomé with a keen eye for the concerns of modern independent women.

——— ——— ———

*Incidentally, both women also had a personal connection to Wilde. Nazimova was a close friend and colleague of Elizabeth Marbury, who worked as Wilde’s agent. Rambova spent summers at her aunt’s (Elsie de Wolfe) villa in France where she lived with her longtime partner, Marbury.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Adolescence of Salome

In the decade following the end of the First World War, there was a great cultural shift for women in America, who experienced and pursued greater independence in society—particularly young and/or unmarried women. This quality was emblematized in the Flappers and the Jazz Babies, but even women who didn’t participate in these subcultures lived lifestyles removed from “home and family” ideals of the past. The lifestyle change was mirrored aesthetically. As Frederick Lewis Allen describes in Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s:

“These changes in fashion—the short skirt, the boyish form, the straight, long-waisted dresses, the frank use of paint—were signs of a real change in the American feminine ideal (as well, perhaps, as in men’s idea of what was the feminine ideal). […] the quest of slenderness, the flattening of the breasts, the vogue of short skirts (even when short skirts still suggested the appearance of a little girl), the juvenile effect of the long waist,—all were signs that, consciously or unconsciously, the women of this decade worshiped not merely youth, but unripened youth […] Youth was their pattern, but not youthful innocence: the adolescent whom they imitated was a hard-boiled adolescent, who thought not in terms of romantic love, but in terms of sex, and who made herself desirable not by that sly art that conceals art, but frankly and openly.”*

Allen’s summary of youthful womanhood in the 1920s resounds so clearly in the character design and performance of Nazimova’s Salomé, it’s apparent that she and Rambova were thoroughly informed by contemporary trends around young/independent women. Belén Ruiz Garrido puts it succinctly in her great essay on the film “Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salomé de Alla Nazimova:”

“Las concomitancias con la flapper o la it girl de los felices años veinte son evidentes. Se muestra mimosa, pero su seducción es como un juego de niña. / The similarities with the flapper or the it girl of the roaring twenties are obvious. She performs affection, but her seduction is like child’s play.” (translation mine)

Nazimova was also fully conscious that her fanbase was predominantly female and that she held significant appeal for younger women. From the moment she signed her first American theatrical contract with Lee Shubert, Nazimova’s status as a queer idol was already being established.

“The women… were enthusiastic about [Nazimova]… [At the hotel, the] ladies’ entrance was always crowded with women waiting for her to return from the theatre. It is much better that she should be exclusive and meet no one if possible. They regard her as a mystery. And there are other damned good reasons besides this one.” – citation: A. H. Canby to Lee Shubert, December 29, 1908**

While women, particularly middle-class women, were emerging as a prominent consumer group in the US, Nazimova’s popularity peaked on stage and on screen. Arriving in Hollywood, Nazimova also continued her trend of surrounding herself socially and professionally with other queer women. Profiles and interviews of Nazimova in the Hollywood press often contained coded language about her queerness as a wink and nudge, usually but not always accompanied by mention of her “husband” Charles Bryant.

This well-developed understanding of her primary fanbase led her to break from popular presentations of the character as an embodiment of monstrous feminine sensuality. Instead, Nazimova chose to present the character as an adolescent. While Nazimova was the first to put this read on the character on film, Marcella Craft chose an adolescent interpretation in a production Strauss’ opera in Munich and Hedwig Reicher was a teenager when she assayed the role and played it accordingly (also in Germany). (Maybe not insignificantly, Reicher was also working in Hollywood at the time of Salomé’s production.)***

This is the American pop culture landscape we’re talking about here, so of course women’s independence was rapidly codified for capitalization. Young women were moralized at for not conforming to traditional gender roles while simultaneously being framed as sexually desirable in order to sell consumer goods (including motion pictures!). The American way. It’s hard to not see social commentary in Nazimova’s reworking of this icon of wanton femininity for a new generation.

This isn’t to suggest that Nazimova’s Salomé glorifies the character, but rather that making Salomé a teen adds layers of complexity to the production. Considering it in conversation with her predecessors, Salomé isn’t even named in the New Testament stories. Flaubert built out the character with 19th century concerns in mind (though his story is more about Herod & Herodias) and Wilde shifted even more focus to Salomé. Nazimova continued that trend with her version of Salomé—an impetuous child too young and ill-equipped to constructively deal with the horrible environment she was brought up in. (Might that resonate with a generation of young people disillusioned by a World War and a pandemic?)

As Nazimova/Peter wrote in the opening intertitles to the film:

“It is at this point that the drama opens, revealing Salome who yet remains an uncontaminated blossom in a wilderness of evil.

“Though still innocent, Salome is a true daughter of her day, heiress to its passions and its cruelties. She kills the thing she loves; she loves the thing she kills, yet in her soul there shines the glimmer of the Light and she sets forth gladly into the Unknown to solve the puzzle of her own words——”

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As Salomé was an experiment in pantomime for screen acting, it’s worthwhile to look at how Nazimova embodies this image of youth in her performance. In the first scenes, Salomé’s facial expressions are pouty and her movements like a bored child’s. Her wig emphasizes every movement she makes with a flurry of pearls and creates a neotenous silhouette for the character. When denied access to Jokanaan, her facial expressions are imperious, but the imperiousness of a spoiled child. She swings on the bars imprisoning Jokanaan as if they are a jungle gym. As she “charms” Narraboth, her expressions and body language shift toward a scheming energy with barely concealed artifice, displaying a distinct lack of sophistication—like she’s trying to angle a second serving of ice cream not exacting a favor of a servant that could cost his life.

Perhaps most crucially, Salomé’s adolescence emphasizes the inappropriateness of men’s gaze upon her. Wilde’s drama is built around rhythmic repetition in the dialogue—a key repetition being the act of looking. Though the play is only one act, some form of “regarder” in relation to Salomé is repeated nineteen times—most often in some form of “don’t look at her” or “you shouldn’t look at her that way.” As Salomé is a silent film, to repeat this in intertitles nineteen times in intertitles would be absurd. Throughout the film, frequent close ups are strategically employed to visually recreate the rhythmic emphasis on gazing. (The purpose of this device seems to have been lost on one reviewer for Exhibitors Herald who said in his review: ”too many close ups.”) Additionally, the motif is foregrounded by front-loading the mentions of looking. As soon as the opening narration ends, we’re introduced to Herod behaving lecherously toward Salomé and Herodias telling him not to look at her. The perversity of Herod is amplified here because Salomé is not only his niece and his step-daughter, but also a child. This scene is followed by Narraboth and the page having a similar interaction, albeit with a different tone.

As Nazimova put it herself in a profile in Close-Up magazine:

“The men about her are obnoxious; they cannot even look upon her decently. She loathes them all. Even the Syrian [Narraboth] whose approach is of all the most respectful and decorous, is of his times and his love is tempered with the alloy of lust.”

In the film, Salomé’s rage against Herod is justified, and her rage against Jokanaan is a raw confusion of emotions—she doesn’t have the capacity to act constructively. When the first unfortunate man commits suicide over her, she barely takes notice, establishing Salome’s blasé attitude toward death. When the second man takes his life this time directly in front of her, Salomé only notices after almost tripping on his body. Her response is giving the body an annoyed kick for tripping her! The key phrase of the drama is “The mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.” Salomé is surrounded by death, enveloped by it, but love (of any kind) is unknown to her until Jokanaan. So, when her love of Jokanaan is rebuked, she reverts to the only response that has been nurtured into her: death.

Nazimova’s Salomé is a perfect surviving example of a quality of her acting described in an uncredited review of Nazimova’s theatrical work:

“If the actress you’re seeing knows what she’s saying but you don’t, it’s Mrs. [Minnie Maddern] Fiske. But if the actress doesn’t know what she is saying and you do, it’s Alla Nazimova.”****

We as viewers understand what Salomé is going through, but she is being psychologically buffeted by fate and circumstance without ever comprehending the nature of it. The tumultuous feelings brought on by Salomé’s first brush with the spiritual (rather than the sexual), launches her into an accelerated ripening of her cruelty. This is masterfully communicated by Nazimova through facial expression and body language and accentuated by Rambova’s costuming.

As Herman Weinberg put it in his essay “The Function of the Actor:”

“The true film crystalizes action for us. ‘To see eternity in a grain of sand,’ the poet said. ‘To see a life cycle in an hour and a half’ is the modern screen parallel.”

Because of the emotional scale of Nazimova’s performance in Salomé, it has been variously described as “bizarre” or “grotesque”—though not always said derogatorily. That’s on point, as Nazimova’s performance is only one expression of her protest against realism in the film.

——— ——— ———

*If you’re interested in the 1920s at all, I highly recommend Allen’s book. The section this quote is from has a detailed survey of changes in American women’s lifestyles throughout the 1920s.

**as quoted in “Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke

***Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova intimates that she referenced the 1917 Tairov production of Wilde’s Salomé, which she reportedly had a detailed description of. Reading about the production for myself in Mark Slonim’s Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets, I’m not sure what precisely she would have drawn from this production. It doesn’t seem to have much in common with the ‘22 film at all. That said, in a 1923 interview with Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, Nazimova admits that in preparing for the film, she compiled a large scrapbook of previous productions and artistic interpretations of the story and character. Unfortunately, though Lambert clearly did voluminous research for his biography, his presentation and interpretation leaves a lot to be desired. Most of the things I tried to verify or try to find more information on from the book proved to be misrepresentations or were factually incorrect. So, I’m avoiding quoting Lambert without verification, unless what I’m citing is directly taken from a primary source; like a quote from Nazimova’s correspondence.

****quotation is from an uncredited clipping held by the Nazimova archive in Columbus, Georgia as quoted in Gavin Lambert’s biography

Illustration of Nazimova as Salomé by F. Corral from The Story World, March 1923

Nazimova and Rambova’s Modernist Phantasy

The assurance that Rambova and Nazimova felt that they had something new to bring to Salomé was obviously not solely founded in a character interpretation updated for the screen and for the decade. The two crafted a singular work born of pastiche in a manner that genuinely had not been done before in the American film industry. It’s often repeated that Salomé is America’s first art film. This may have its origin in promotional materials* made for the initial release of the film. Before the film’s official release, Bryant, Nazimova, and Paul Ivano (assistant camera & Nazimova’s on-again-off-again lover) arranged preview screenings and a few reviews from those screenings mention in some form that Salomé was a direct retort to the notion that art cannot be made with a camera.

What constituted the Nazimova/Rambova strategy to elevate film to the status of art? Both women had around six years of experience working in film (twelve collectively), but both came from a live performance background—theatrical acting and ballet respectively. Salomé is a film based on a stage play (though not strictly based on any one production of that play). Salomé inherits its symbology (first and foremost the moon) from its source material, but the filmmakers found creative ways of communicating and remixing symbols for the camera. The art design is inspired by Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for a printed edition of the play, though Rambova pulled more broadly from art-nouveau to devise designs that are in no way unoriginal.

As for the much discussed Dance of the Seven Veils, in my opinion, Nazimova’s execution is inspired by the dance described in Flaubert’s “Herodias” rather than a previous live performance.

“Again the dancer paused; then, like a flash, she threw herself upon the palms of her hands, while her feet rose straight up into the air. In this bizarre pose she moved about upon the floor like a gigantic beetle; then stood motionless.

“The nape of her neck formed a right angle with her vertebrae. The full silken skirts of pale hues that enveloped her limbs when she stood erect, now fell to her shoulders and surrounded her face like a rainbow. Her lips were tinted a deep crimson, her arched eyebrows were black as jet, her glowing eyes had an almost terrible radiance; and the tiny drops of perspiration on her forehead looked like dew upon white marble.”

Clearly, I’m not implying that what’s described above is exactly what we see on screen. My thought instead is that Nazimova may have drawn inspiration for the dance to be provocative in an uncanny way instead of provocative in a conventionally sensuous way. What we do see on screen is a distinct lack of practiced sensuality and an element of menace. The former comes both from Salomé’s youthfulness and from the logic that, as Salomé has already gotten Herod to give her his word in front of dignitaries, there’s no need for seduction. The latter is brought on by the expression of Salomé’s fractured emotional state and feelings about Herod. In execution, the use of close-ups again serves a major purpose. Intercutting close-up reactions from those gathered at the court provides a crescendo to the motif of looking, which is then pivotally reversed in the kiss scene. Cutting to close-ups of Salomé’s face accents the ecstatic and maniacal quality of the dance. Together this variation of shots creates an effect that could only work on film.

Salomé has a significant appreciation for its non-cinematic antecedents, but filtered through the prism of Nazimova’s and Rambova’s own creative strengths and sensibilities—a melding of theater and graphic art into something not only fresh but also totally cinematic.

It speaks to their filmmaking skill that all of these ideas and influences do in fact come together as a cohesive yet wholly unconventional film. Some critics of Salomé (both contemporary and modern) will cite vague notions of theatricality, or state that the film is only a series of tableaux, or that the limited sets don’t depart enough from a stage presentation. Art is in the eye of the beholder, but I think whether those specific elements preclude Salomé from being cinematic is a matter of perspective.

The oversized, stylized nature of Salomé’ssets might at first register as theatrical, but those same sets also serve to amp up the anti-real nature of the film. It’s uncharitable to Rambova to suggest that this artificiality was not a conscious artistic decision. If you have seen the sequences she designed with Mitchell Leisen for De Mille’s Forbidden Fruit (1921) then you have seen her demonstrated understanding of how designs register on camera. The gorgeously executed lighting effects in Salomé that are employed to to sublimate tone shifts could feasibly be recreated in a theatrical setting, here, filtered through the camera of Van Enger, register as thoroughly cinematic.

To once again quote “The Function of the Actor” by Weinberg:

“In nine movies out of ten (most particularly those emanating from the film factories of Hollywood), the actors stand around and talk to each other, relieved only by periodic bursts of someone going in or out of a doorway. (Sixty percent of the action in the average Hollywood movie consists of people going in and out of doors.) […]

“The actor going through a doorway may be a necessary device on the stage, to get him on and off. But Pudovkin has made a neat distinction between the realities of stage and screen: ‘The film assembles the elements of reality to build from them a new reality proper to itself; and the laws of time and space that, in sets and footage of the stage are fixed and fast, are in the film entirely altered.’ On the stage, that is, an event seems to occur in the same length of time it would occupy in life. On the screen, however, the camera records only the significant parts of the event, and so the filmic time is shorter than the real time of the event.”

Weinberg cites Pudovkin in an amusing but illustrative way here. People may throw “overly theatrical” or “stagey” casually, but more often than not the distinction between theatrical/cinematic comes down to how space and time is traversed. Even if the base material, a narrative drama for example, is shared between stage and screen, there should be a thoughtful construction of geography and chronology. Could Salomé have played more creatively with space? Perhaps. But, for a film made in early 1922, its creative geography isn’t all that uninventive. The majority of the action in Salomé takes place exclusively on one set, so it does rely a lot on the types of comings and goings that Weinberg identifies with theatre. That said, there are some comings and goings that forcefully pull the audience away from the feeling of stagey-ness. The most consequential occurs in the scene with the first suicide, which I previously mentioned in the context of developing Salomé‘s character and environment. The man runs to the ledge of the courtyard, beholds the moon, and leaps. Cut to a wide, back-lit shot of the figure plunging to nowhere, establishing that the city above the clouds depicted in the art titles and opening credits is the actual physical location that film is taking place in. It’s a genuinely startling moment in the film and Salomé’s most evocative use of creative geography.

The majority of legitimate critical appraisal at the time of Salomé’s release recognize it as an achievement in film art, even highlighting artsiness as a potential selling point. As art cinemas started popping up in the US, Salomé stayed in circulation. Appreciation grew. Legends emerged around its production. And, now one hundred years later, it’s safe to say that Salomé has earned and kept its place as a fixture of the history of film art. As we are lucky enough to have the complete film to watch, assess, reassess, and debate its qualities as a work of cinematic art, I’m positive that conversation on Salomé will continue.

So, if Salomé was appreciated in its time, why did it ruin and bankrupt Nazimova? What was going on in the American film industry at the time? Find out in part two!

“If we have made something fine, something lasting, it is enough. The commercial end of it does not interest me at all. I hate it. This I do know: we must live, and I must live well. I have suffered—enough. Never again shall I suffer. But most of all am I concerned in creating something that will lift us all above this petty level of earthly things. My work is my god. I want to build what I know is fine, what I feel calling for expression. I must be true to my ideals—”

— Nazimova on Salomé quoted in “The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm Oettinger

——— ——— ———

*As of the time of writing, I haven’t been able to track down a complete copy for the campaign book for the film, so I’m relying on fragments, quotes, and second-hand references to its content.

——— ——— ———

Read Part Two Here

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Bibliography/Further Reading

(This isn’t an exhaustive list, but covers what’s most relevant to the essay above!)

Salomé by Oscar Wilde [French/English]

“Herodias” by Gustave Flaubert [English]

Cosplay the Classics: Natacha Rambova

Lost, but Not Forgotten: A Doll’s House (1922)

“Temperament? Certainly, says Nazimova” by Adela Rogers St. Johns in Photoplay, October 1926

“Newspaper Opinions” in The Film Daily, 3 January 1923

“Splendid Production Values But No Kick in Nazimova’s “Salome” in The Film Daily, 7 January 1923

“SALOME” in The Story World, March 1923

“SALOME’ —Class AA” from Screen Opinions, 15 February 1923

“The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, April 1923

“Famous Salomes” by Willard H. Wright in Motion Picture Classic, October 1922

“Nazimova’s ‘Salome’” by Walter Anthony in Closeup, 5 January 1923

“Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke in Passing Performances: Queer Readings of Leading Players in American Theater History

“Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salome de Alla Nazimova” by Belén Ruiz Garrido (Wish I had read this at the beginning of my research and writing instead of near the end as it touches upon a few of the same points as my essay! Highly recommended!)

“The Function of the Actor” by Herman Weinberg

“‘Out Salomeing Salome’: Dance, The New Woman, and Fan Magazine Orientalism” by Gaylyn Studlar in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film

Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (Note: I do not recommend this without caveat even though it’s the only monograph biography of Nazimova. Lambert did a commendable amount of research but his presentation of that research is ruined by misrepresentations, factual errors, and a general tendency to make unfounded assumptions about Nazimova’s motivations and personal feelings.)

Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s by Frederick Lewis Allen

Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets by Mark Slonim

#1920s#1922#1923#Nazimova#alla nazimova#natacha rambova#cosplay#fan art#Salome#Oscar Wilde#film history#independent film#silent cinema#classic cinema#film#american film#queer cinema#women filmmakers#queer#cosplay the classics#queer film#cinema#women directors#classic film#classic movies#silent film#my gifs#silent movies#silent era#history

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submission: About the house facade falling

About that reference to a silent movie with house facade falling - hello silent movie fan here! :)

You are thinking of the iconic scene from "Steamboat Bill jr", a film by and with Buster Keaton! (Who happens to be a cousin of mine, so double interest jippie!)

This is one of his most famous scenes. The house facade was weighing about 2 tons, so no cardboard here - he could have been killed if the calculations hadn't worked out and the crew on set was worried about Buster's safety. This is even more amazing when you think about Buster's education or lack thereof - his parents were Vaudevillian actors and Buster grew up "on tour" and acting from early childhood on. Meaning he never got a formal education. He famously had difficulties writing his own name. Buster couldn't really read or write but created these elaborated sets and stunts himself.

Buster talked about that if he hadn't been born into an entertainment business family, he would have become an engineer. The film industry was quite literally build with his technical input on film technology (he took cameras apart and rebuild them, to make them more adaptable to his ideas for example) and stunt work on set.

All of this to say - the falling facade is iconic in so many ways! And I hope Taylor saw "Steamboat Bill jr". :)

Copyright has run out and Library of Congress has put it on the National Film Registry. So it is easily possible to watch this online.

I don't know if I'm being a bit too informed but I want to add this too - maybe Taylor not only wanted to reference (maybe) this iconic scene, but also the circumstances?

You see Buster was one of THE creators of cinema. Even back then people acknowledged that. But he was always bad with, or rather not interested in, money!

Unlike Charlie Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, his two big contemporaries, he decided to sign with a big studio. Thinking that way he didn't have to do the paper work (he couldn't read anyway) and accounting and the studio could do the promo work he wasn't really interested in.

That deal turned to be his downfall! He got screwed over with the contract. The studio thought he was dumb and uneducated and treated him terribly. Buster suddenly had to hand in written scripts - how? The studio was getting more and more involved with production because he couldn't give them written pages ... it was a disaster!

At that time his marriage to a famous actress also started to fall apart and Buster started drinking. By the time of "Steamboat Bill jr" he was a full blown alcoholic. His last wife, he met after he had sobered up, Eleanor, later talked about that everyone around Buster back then thought, he was trying to kill himself with this stunt (which was filmed at the end of the movie shoot) because he was so desperate and depressed at that point. He couldn't deal with his marriage falling apart and the studio trying to micromanage him.

So yeah ... I don't know. Did Taylor reference this? She knows about Clara Bow, the star no one was interested in when she started speaking ... does she know about Buster and his conflict with the film industry which sucked him dry and discarded him? Possible ...

If you want to know more about Buster - there is a very good documentary "Buster Keaton - a hard act to follow". He is also featured in the "Silent Hollywood" documentary series. All his films are amazing, but his personal favourite was "The General". I think that is the one Buster would recommend to you. ;)

————

Anonymous said:

So after the volcano 🌋 anon she Buster Keaton’s through the door and comes out under the floor.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ava Gardner & Le Galion: L’ASTRE – Ava, Incendiary Star

The year 2022 marks the centenary of the birth of an icon of Hollywood cinema: Ava Gardner. Archetype of the femme fatale, personification of luscious femininity, the great actress was close to the house of Le Galion at the end of the 1950s.

She met Paul Vacher and became an ambassador for Sortilège, before asking him to compose a tailor-made fragrance for her. The perfumer, close to many stars of the time (Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Grace Kelly…) complied.

In 2022, Le Galion is launching L'Astre, a contemporary rewrite of a formula that has remained private for decades. Worked in collaboration with the heirs of Ava Gardner who offer access to their archives, L'Astre symbolizes the brilliance of these two great names of the 20th century, whose influence continues today

Created by Rodrigo Florès-Roux, this new version of L’Astre is, according to the perfumer, a “large, exuberant and magnetic floral.” After a catchphrase made of sensual spices, the perfumer worked on “a spectacular floral accord” made of white flowers, before continuing with an amber, warm and enveloping background.

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Wow, I so loved this video and found it to be so comforting! Tab Hunter seems like he was a really sweet, sensitive guy who made a great life for himself despite a ton of misfortune, rejection, and homophobia in Hollywood. It's rare for a story of a queer actor's life from this era to have such a happy ending.

It's seriously impressive that after years of studio suppression he was able to openly embrace queer cinema by working with John Waters and the come out for himself, too. Lots of his contemporaries took their secrets to their graves, but in the interviews featured Tab seems so open and joyful, and at peace at where he was in his old age.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fünf von der Jazzband (1932)

I'd like to thank the anonymous person who sent me the question about this film tonight, because I was finally inspired to sit down and watch the whole thing! I'm glad, too, because it's very funny. 😁

True, I am not a German speaker and I didn't have the benefit of subtitles, but I was surprised at how much of the dialogue I did understand. Good heavens, maybe I learned something. Or maybe the plot of this bubbly musical comedy is simple enough even for dopes like me, I dunno. It starts when a young lady of no musical talent accidentally joins up with a jazz quartet after she falls butt-first off a ladder and into the bass drum. Things only escalate from there with a series of comedic misunderstandings, including getting wrongfully mixed up with a gang of car thieves:

oh yeah and Peter Lorre is here, briefly

I checked, and Peter doesn't appear in the film for almost a full hour!! It's not that I wasn't enjoying the story without him, I absolutely was, but in the back of my mind I kept wondering when on earth he was going to show up. Normally, if he's not in a prominent role, the patented Lorre appearance occurs no later than the first half hour or so. Here it's little more than a glorified cameo at a point when the story is nearly over. I mean, he doesn't have a whole lot to do anyway.

This actually gave me something of a revelation as I was watching. It has been speculated by modern critics and even some of Peter's contemporaries, like Brecht or Lang, that had the war never occurred and Peter was never forced to flee Germany, his career would have blossomed beyond his wildest imaginings and he would have been even more renowned in the most prestigious works of film and stage, oh why did Hollywood have to corrupt his genius, etc. etc.

And yet. What exactly did German cinema offer him? It seems to me that the execs at Ufa had just as little imagination when it came to finding something suitable to his talents. In the wake of his success in M, Lorre turned down role after role of crazed psycho killer and retreated into things like this, into lighthearted musical comedy only remembered by us giant nerds film enthusiasts. Sure, he loved doing comedy. However these movies, however fun and enjoyable, are treated today as forgettable footnotes in film history, barely a ripple in the cinematic pond. Is that somehow better? If not for the war, would we instead speak of Lorre today as an amusing but ultimately obscure character actor of German film and TV, a familiar face once but not recognized by anyone under a certain age? Would he never haunt the imagination of creators today, the ones who never knew his name but still understand, as if by base instinct, the meaning of his voice and face?

We have no way of knowing. Perhaps this was not all that Germany could have offered him, had the war never happened. But to me, these films only look like a different sort of cage--perhaps even smaller than the one Hollywood prepared for him.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anyway here's my reading list for my big film censorship project in case anyone's been wondering what I've been up to when I'm not being a stupid idiot cringey fandom blogger or whatever the jackasses think I am:

Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, by Frank Cullen

Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment, 1890-1925, by David Monod

From Traveling Show to Vaudeville: Theatrical Spectacle in America, 1830-1910, edited by Robert M. Lewis

American Vaudeville as Ritual, by Albert F. McLean Jr.

American Vaudeville As Seen by its Contemporaries, edited by Charles W. Stein

Rank Ladies: Gender and Cultural Hierarchy in American Vaudeville, by M. Alison Kibler

The New Humor in the Progressive Era: Americanization and the Vaudeville Comedian, by Rick DesRochers

Humor and Ethnic Stereotypes in Vaudeville and Burlesque, by Lawrence E. Mintz

"Vaudeville Indians" on Global Circuits, 1880s-1930s, by Christine Bold

The Original Blues: The Emergence of the blues in African American Vaudeville, by Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff

Waltzing in the Dark: African American Vaudeville and Race Politics in the Swing Era, by Brenda Dixon Gottschild

The Wizard of Menlo Park: How Thomas Alva Edison Invented the Modern World, by Randall Stross

Edison, by Edmund Morris

The Rise and Place of the Motion Picture, by Terry Ramsaye

The Romantic History of the Motion Picture: A Story of Facts More Fascinating than Fiction, by Terry Ramsaye (Photoplay Magazine)

Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company, by Charles Musser

The Kinetoscope: A British History, by Richard Brown, Barry Anthony, and Michael Harvey

The Man Who Made Movies: W.K.L. Dickson, by Paul Spehr

A Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture, by Terry Ramsaye

Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907, by Charles Musser

Dancing for the Kinetograph: The Lakota Ghost Dance and the Silence of Early Cinema, by Michael Gaudio

The First Screen Kiss and "The Cry of Censorship," by Ralph S.J. Dengler

Archival Rediscovery and the Production of History: Solving the Mystery of Something Good - Negro Kiss (1898), by Allyson Nadia Field

Prizefighting and the Birth of Movie Censorship, by Barak Y. Orbach

A History of Sports Highlights: Replayed Plays from Edison to ESPN, by Raymond Gamache

A History of the Boxing Film, 1894-1915: Social Control and Social Reform in the Progressive Era, by Dan Streible

Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema, by Dan Streible

The Boxing Film: A Cultural and Transmedia History, by Travis Vogan

Policing Sexuality: the Mann Act and the Making of the FBI, by Jessica R. Pliley

Screened Out: Playing Gay in Hollywood, from Edison to Stonewall, by Richard Barrios

The Ashgate Research Companion to Moral Panics, edited by Charles Krinsky

A Companion to Early Cinema, edited by Andre Gaudreault, Nicolas Dulac, and Santiago Hidalgo

The Silent Cinema Reader, edited by Lee Grieveson and Peter Kramer

The Harlot's Progress: Myth and Reality in European and American Film, 1900-1934, by Leslie Fishbein

Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era, by Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser

Banned in Kansas: Motion Picture Censorship, 1915-1966, by Gerald R. Butters, Jr.

Black and White and Blue: Adult Cinema From the Victorian Age to the VCR

Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood, by Mick Lasalle

Dangerous Men: Pre-Code Hollywood and the Birth of the Modern Man, by Mick Lasalle

Pre-Code Hollywood: Sex, Immorality, and Insurrection in American Cinema, 1930-1934, by Thomas Doherty

Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934), When Sin Ruled the Movies, by Mark A. Vieira

Sin in Soft Focus: Pre-Code Hollywood, by Mark A. Vieira

Hollywood's Censor: Joseph I. Breen & the Production Code Administration, by Thomas Doherty

The Dame in the Kimono: Hollywood, Censorship, and the Production Code, by Leonard J. Leff and Jerold L. Simmons

Moral House-Cleaning in Hollywood: What's it All About? An Open Letter to Mr. Will Hays, by James R. Quirk (Photoplay Magazine)

Will H. Hays - A Real Leader: A Word Portrait of the Man Selected to Head the Motion Picture Industry, by Meredith Nicholson (Photoplay Magazine)

Ignorance: An Obnoxiously Moral morality Play, Suggested by "Experience," by Agnes Smith (Photoplay Magazine)

Close-Ups: Editorial Expression and Timely Comment (Photoplay Magazine)

Children, Cinema & Censorship: From Dracula to the Dead End Kids, by Sarah J. Smith

Freedom of the Screen: Legal Challenges to State Film Censorship, 1915-1981, by Laura Wittern-Keller

Picturing Indians: Native Americans in Film, 1941-1960, by Liza Black

America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies, by Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin

White: Essays on Race and culture, by Richard Dyer

Black American Cinema, edited by Manthia Diawara

Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World, by Wil Haygood

Hollywood's Indian: the Portrayal of the Native American in Film, edited by Peter C. Rollins and John E. O'Connor

Wiping the War Paint Off the Lens: Native American Film and Video, by Beverly R. Singer

Celluloid Indians: Native Americans and Film, by Jacquelyn Kilpatrick

Native Americans on Film: Conversations, Teaching, and Theory, edited by M. Elise Marubbio and Eric L. Buffalohead

Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film, by Ed Guerrero

Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films, by Donald Bogle

Hollywood Black: the Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers, by Donald Bogle

White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood From the Dark Side, by James Snead

Latino Images in Film: Stereotypes, Subversion, and Resistance, by Charles Ramirez Berg

Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism, by Nancy Wang Yuen

Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, edited by Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar

The Hollywood Jim Crow: the Racial Politics of the Movie Industry, by Maryann Erigha

America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, by Daniel Eagan

Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies, by Robert Sklar

Of Kisses and Ellipses: The Long Adolescence of American Movies, by Linda Williams

Banned in the Media: A Reference Guide to Censorship in the Press, Motion Pictures, Broadcasting, and the Internet, by Herbert N. Foerstel

Censoring Hollywood: Sex and Violence in Film and on the Cutting Room Floor, by Aubrey Malone

Hollywood v. Hard Core: How the Struggle Over Censorship Saved the Modern Film Industry, by Jon Lewis

Not in Front of the Children: "Indecency," Censorship, and the Innocence of Youth, by Marjorie Heins

Degradation: What the History of Obscenity Tells Us About Hate Speech, by Kevin W. Saunders

Censoring Sex: A Historical Journey Through American Media, by John E. Semonche

Dirty Words & Filthy Pictures: Film and the First Amendment, by Jeremy Geltzer

Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon, by Alexander Doty

Masculine Interests: Homoerotics in Hollywood Film, by Robert Lang

Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film, by Harry M. Benshoff

New Queer Cinema: A Critical Reader, edited by Michele Aaron

New Queer Cinema: The Director's Cut, by B. Ruby Rich

Now You See It: Studies on Lesbian and Gay Film, by Richard Dyer

Gays & Film, edited by Richard Dyer

Screening the Sexes: Homosexuality in the Movies, by Parker Tyler

Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Essays on Popular Culture, edited by Corey K. Creekmur and Alexander Doty

Out Takes: Essays on Queer Theory and Film, edited by Ellis Hanson

Queer Images: a History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America, by Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin

The Lavender Screen: the Gay and Lesbian Films, Their Stars, Makers, Characters, & Critics, by Boze Hadleigh

The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, by Vito Russo

Tinker Belles and Evil Queens: the Walt Disney Company From the Inside Out, by Sean Griffin

The Encyclopedia of Censorship, by Jonathon Green

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

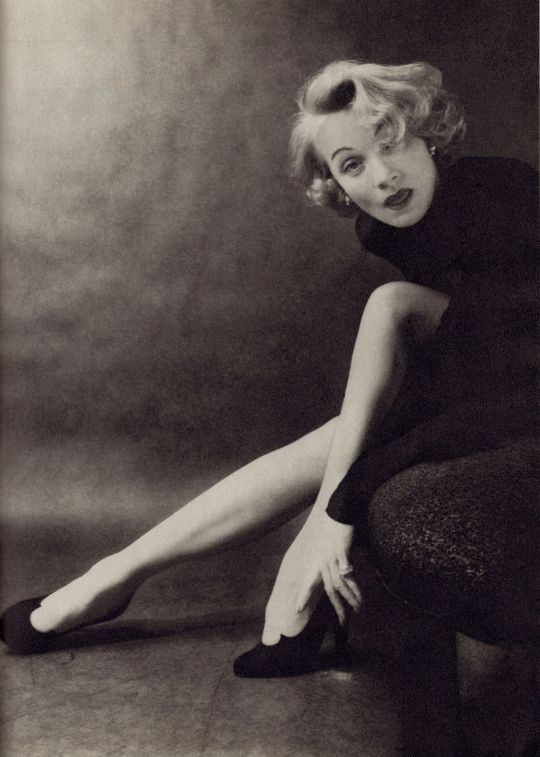

Propaganda

Marlene Dietrich (Shanghai Express, Witness for the Prosecution, Morocco)—Bisexual icon, super hot when dressed both masculine and feminine, lived up her life in the queer Berlin scene of the 1920s, central to the 'sewing circle' of the secret sapphic actresses of Old Hollywood, refused lucrative offers by the Nazis and helped Jews and others under persecution to escape Nazi Germany, the love of my life

Xia Meng, also known as Hsia Moog or Miranda Yang (Sunrise, Bride Hunter)—For those who are familiar with Hong Kong's early cinema, Xia Meng is THE leading woman of an era, the earliest "silver-screen goddess", "The Great Beauty" and "Audrey Hepburn of the East". Xia Meng starred in 38 films in her 17-year career, and famously had rarely any flops, from her first film at the age of 18 to her last at the age of 35. She was a rare all-round actress in Mandarin-language films, acting, singing, and dancing with an enchanting ease in films of diverse genres, from contemporary drama to period operas. She was regarded as the "crown princess" among the "Three Princesses of the Great Wall", the iconic leading stars of the Great Wall Movie Enterprises, which was Hong Kong's leading left-wing studio in the 1950s-60s. At the time, Hong Kong cinema had only just taken off, but Xia Meng's influence had already spread out to China, Singapore, etc. Overseas Chinese-language magazines and newspapers often featured her on their covers. The famous HK wuxia novelist Jin Yong had such a huge crush on her that he made up a whole fake identity as a nobody-screenwriter to join the Great Wall studio just so he can write scripts for her. He famously said, "No one has really seen how beautiful Xi Shi (one of the renowned Four Beauties of ancient China) is, I think she should be just like Xia Meng to live up to her name." In 1980, she returned to the HK film industry by forming the Bluebird Movie Enterprises. As a producer with a heart for the community, she wanted to make a film on the Vietnam War and the many Vietnam War refugees migrating to Hong Kong. She approached director Ann Hui and produced the debut film Boat People (1982), a globally successful movie and landmark feature for Hong Kong New Wave, which won several awards including the best picture and best director in the second Hong Kong Film Award. Years later, Ann Hui looked back on her collaboration with Xia Meng, "I'm very grateful to her for allowing me to make what is probably the best film I've ever made in my life."

This is round 5 of the tournament. All other polls in this bracket can be found here. Please reblog with further support of your beloved hot sexy vintage woman.

[additional propaganda submitted under the cut.]

Xia Meng:

Marlene Dietrich:

ms dietrich....ms dietrich pls.....sit on my face

its marlene dietrich!!!! queer legend, easily the hottest person to ever wear a tuxedo, that hot hot voice, those glamorous glamorous movies…. most famously she starred in a string of movies directed by josef von sternberg throughout the 1930s, beginning with the blue angel which catapulted her to stardom in the role of the cabaret singer lola lola. known for his exquisite eye for lighting, texture, imagery, von sternberg devoted himself over the course of their collaborations to acquiring exceptional skill at photographing dietrich herself in particular, a worthy direction in which to expend effort im sure we can all agree. she collaborated with many other great directors of the era as well, including rouben mamoulian (song of songs), frank borzage (desire), ernst lubitsch (angel), fritz lang (rancho notorious), and billy wilder (witness for the prosecution). the encyclopedia britannica entry im looking at while compiling this propaganda describes her as having an “aura of sophistication and languid sexuality” which✔️💯. born marie magdalene dietrich, she combined her first and middle names to coin the moniker “marlene”. she was a trendsetter in her incorporation of trousers, suits, and menswear into her wardrobe and her androgynous allure was often remarked upon. critic kenneth tynan wrote, “She has sex, but no particular gender. She has the bearing of a man; the characters she plays love power and wear trousers. Her masculinity appeals to women and her sexuality to men.” in the 1920s she enjoyed the vibrant queer nightlife of weimar berlin, visiting gay bars and drag balls, and in hollywood her love affairs with men and women were an open secret. she was an ardent opponent of nazi germany, refusing lucrative contacts offered her to make films there, raising money with billy wilder to help jews and dissidents escape, and undertaking extensive USO tours to entertain soldiers with an act that included her a playing musical saw and doing a mindreading routine she learned from orson welles. starting in the 50s and continuing into the mid-70s she worked largely as a cabaret artist touring the world to large audiences, employing burt bacharach as her musical arranger.

First of all, there are those publicity photos of her in a tux. Second of all, I have never been the same since knowing that she sent copies of those photos to her Berlin lovers signed "Daddy Marlene." Not only is she hot in all circumstances, but she can do everything from earthy to ice queen. Also, she kept getting sexy romantic lead parts in Hollywood after the age of 40, which would be rare even now. She hated Nazis, loved her friends, and had a sapphic social circle in Hollywood. She also had cheekbones that could cut glass and a voice that could melt you.

Her GENDER her looks her voice her everything

“In her films and record-breaking cabaret performances, Miss Dietrich artfully projected cool sophistication, self-mockery and infinite experience. Her sexuality was audacious, her wit was insolent and her manner was ageless. With a world-weary charm and a diaphanous gown showing off her celebrated legs, she was the quintessential cabaret entertainer of Weimar-era Germany.”

The bar scene in Morocco awoke something in me and ultimately changed my gender

youtube

"Her manner, the critic Kenneth Tynan wrote, was that of ‘a serpentine lasso whereby her voice casually winds itself around our most vulnerable fantasies.’ Her friend Maurice Chevalier said: ‘Dietrich is something that never existed before and may never exist again.’”

"Songstress, photographer, fashion icon, out bisexual phenom (notoriously stole Lupe Velez and Joan Crawford's men, and Errol Flynn's wife, had a torrid affair with Greta Garbo that ended in a 60-year feud, other notable conquests including Erich Maria Remarque -yes, the guy who wrote All Quiet on the Western Front- Douglas Fairbanks Junior, Claudette Colbert, Mercedes de Acosta, Edith Piaf), anti-Nazi activist. Marlene was a bitch - she had an open marriage for decades and one of her favorite things was making catty commentary about her current lover with her husband, and her relationship with her daughter was painful- but she was also immensely talented, a hard worker, an opponent of fascism and the hottest ice queen in Hollywood for a long time."

youtube

"She can sing! She can act! She told the Nazis to fuck off and became a US citizen out of spite! She worked with other German exiles to create a fund to help Jews and German dissidents escape (she donated an entire movie salary, about $450k, to the cause). She looks REALLY GOOD in a suit. If you're not convinced, please listen to her sing "Lili Marlene". Absolutely gorgeous woman with a gorgeous voice."

Gifset link

"Bisexual icon and Nazi-hater. Looks absolutely stunning in the suits she liked to wear. 'I dress for the image. Not for myself, not for the public, not for fashion, not for men'."

"would you not let her walk on you?"

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cillian Murphy is one of the most beloved actors in contemporary cinema. After starring in indie favourites 28 Days Later and Intermission in the early 2000s, Murphy secured his place in Hollywood by forging a long-standing relationship with director Christopher Nolan. The two worked together on Batman Begins and have since collaborated on five more films, most recently, Oppenheimer.

While he was breaking America, Murphy also honed his acting reputation closer to home as Tommy Shelby in Peaky Blinders. But before he became one of the most recognisable and respected names in film, Murphy very nearly pursued a music career.

In his youth, Murphy was particularly passionate about music. The budding actor was in a band with his brother named The Sons of Mr. Green Genes, who even received an offer to do five albums with Acid Jazz Records. They declined the offer, but Murphy’s love for music persisted and he still enjoys engaging with music. He even told the Sunday Independent Life Magazine that the only extravagances in his lifestyle are his “stereo system, buying music and going to gigs”.

His love of music has also bled into his professional life. Between shooting with Nolan and collecting Bafta nominations for his work on Peaky Blinders, Murphy has presented a show on the beloved alternative radio station, BBC Radio 6. He once told the BBC, “One of my favourite things in the world is playing music on my favourite radio station in the world”.

As well as providing Murphy with an outlet for his love of music, the show has also given fans insight into his music taste, which is both wide-spanning and characteristically Radio 6. During his time with the BBC, he shared his love for a number of artists and tracks, including fellow Irishmen Fontaines D.C., stating, “There is a great explosion of new Irish music… Every single tune, they’re relentlessly themselves”.

He once shouted out Radiohead’s ‘Daydreaming’, stating, “When Radiohead released ‘Daydreaming’, I listened to it five times in a row. I think it’s a remarkable piece of music”. He’s also given nods to Low, Elbow, and Kendrick Lamar, who he notes is a favourite of his son’s.

Throughout his appearances on the radio station, Murphy has played over 400 songs ranging from trip-hoppers Massive Attack to indie folk favourites Big Thief to jazz composer Alice Coltrane. The show acted as a platform for Murphy’s expansive music taste and a great place to pick up recommendations for Murphy fans and casual radio listeners alike...'

#Cillian Murphy#Radiohead#“Daydreaming”#Low#Elbow#Kendrick Lamar#Big Thief#Alice Coltrane#Massive Attack#28 Days Later#Intermission#Christopher Nolan#Batman Begins#Oppenheimer#The Sons of Mr. Green Genes#Tommy Shelby#Peaky Blinders#BBC Radio 6#Fontaines D.C.

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

14 and 26??

thank you very much for the ask from the i'm not from the states ask game, anon!

14. do you enjoy your country’s cinema and/or tv?

26. does your nationality get portrayed in hollywood/american media? what do you think about the portrayal?

now - i think these two have to be taken together...

so, yes, i do enjoy our media - we have obviously produced the finest comedy television show in recent history, after all.

but i do think that media made in ireland - or, at least, made in ireland in english - suffers from the fact that it's aiming to be marketable outside of ireland. and - in particular - that it's aiming to be marketable in both britain and the united states.

which means that it takes an interest in portraying an image of irishness which is appealing to those countries.

when it comes to the states, the way we are portrayed and the way we portray ourselves is always aiming to tap into a view of ireland which dominates the american national consciousness - as a country which americans, especially on the east coast, consider themselves enormously culturally aligned to and politically sympathetic with, due to the sheer size of the irish-american community.

let's get the cards on the table - being irish-american is a meaningful cultural identity within the united states. it is not - and it never, ever will be - the same as actually being irish [which someone ought to tell the president...]. and one reason is because the centrality of emigration to the irish-american identity requires ireland to become a quasi-mystical place, preserved in aspic at the point mass emigration to the states really took off.

that's why you end up with the portrayal of ireland you see in films like the banshees of inisherin - quaint, rural, full of half-wit musical drunkards who love a wee chat, surrounded by historical events but also sort of outside them...

in britain, the geographical proximity, the easier movement across boarders, and the fact that these enable diaspora communities to retain closer links with ireland [one of the single most amusing activities in the world is watching irish-americans learn that vast numbers of brits have more recent irish heritage than they do...] means that ireland is treated less like a magical fantasy land unchanged from ages past.

but it's nonetheless affected by the brits' own stereotypical view of the country - that the rural south is full of superstitious, unsophisticated idiots [who sometimes get to have hearts of gold!] who've never seen pesto; that the urban south is generally indistinguishable from london; and that the north is full of grey housing estates interspersed with burned-out cars and everyone is a terrorist.

again and again it seems that the only way to get funding for a project about ireland is to pick one of the famine, the war of independence, or the troubles as your setting. there's so little representation of what ireland looks like in the here-and-now - not least in the fact that you'd get the impression from its international film and television that it's a country where everyone is white...

and even media which is set in contemporary ireland and which does make an effort to be more diverse - such as the tv adaptation of normal people - presents an ireland designed for international consumption [trinity college dublin does run itself very much like oxford and cambridge in real life - but this is turned up to eleven in normal people in a way which is clearly aimed at the british audience...].

which is something i'd like to see us get a grip on, tbh.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Westworld at 50: Michael Crichton’s AI dystopia was ahead of its time

by Keith McDonald, Senior Lecturer Film Studies and Media at York St John University

Westworld turned 50 on November 21. Director Michael Crichton’s cautionary tale showed that high-concept feature films could act as a vehicle for social commentary. Westworld blended cinematic genres, taking into account the audience’s existing knowledge of well-worn narrative conventions and playfully subverting them as the fantasy turns to nightmare.

The film centres on a theme park where visitors, in this case the protagonists Peter (Richard Benjamin) and John (James Brolin), can enter a simulated fantasy world – Pompeii, Medieval Europe, or the Old West. Once there, they can live out their wildest fantasies. They can even have sex with the synthetic playthings that populate the worlds.

This sinister idea went on to be explored further in later films such as The Stepford Wives (1975 & 2004), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) and Ex Machina (2014).

youtube

Of course, it all goes terribly wrong when a computer virus overruns the park and the androids become unbound from the safety protocols that have been encoded into them. The resultant horror climaxes with Peter being stalked through the park by the menacing gunslinger (Yul Brynner).

The film isn’t perfect. Westworld was Michael Crichton’s feature directorial debut, and it shows – as does the tight shooting schedule and frugal budget imposed by MGM. The studio was notorious at the time for mishandling projects and their directors.

Compared to some of the other notable films released that year, such as William Friedkin’s masterful The Exorcist, Nicolas Roeg’s terrifying Don’t Look Now and Clint Eastwood’s assured High Plains Drifter, Westworld has a B-movie aesthetic.

This is, though, elevated by a towering performance from Brynner, and the high-concept approach that later came to dominate the Hollywood system. The film also provided fruitful inspiration for an ambitious HBO adaptation in 2016.

Genre blending and bending

Westworld successfully blended science fiction with other genres. In this sense, it was a pioneering film, which made the most of its limitations due to the hugely influential imagination of Crichton and a postmodern masterstroke of the casting and performance of Brynner.