#contentideators

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Copyright takedowns are a cautionary tale that few are heeding

On July 14, I'm giving the closing keynote for the fifteenth HACKERS ON PLANET EARTH, in QUEENS, NY. Happy Bastille Day! On July 20, I'm appearing in CHICAGO at Exile in Bookville.

We're living through one of those moments when millions of people become suddenly and overwhelmingly interested in fair use, one of the subtlest and worst-understood aspects of copyright law. It's not a subject you can master by skimming a Wikipedia article!

I've been talking about fair use with laypeople for more than 20 years. I've met so many people who possess the unshakable, serene confidence of the truly wrong, like the people who think fair use means you can take x words from a book, or y seconds from a song and it will always be fair, while anything more will never be.

Or the people who think that if you violate any of the four factors, your use can't be fair – or the people who think that if you fail all of the four factors, you must be infringing (people, the Supreme Court is calling and they want to tell you about the Betamax!).

You might think that you can never quote a song lyric in a book without infringing copyright, or that you must clear every musical sample. You might be rock solid certain that scraping the web to train an AI is infringing. If you hold those beliefs, you do not understand the "fact intensive" nature of fair use.

But you can learn! It's actually a really cool and interesting and gnarly subject, and it's a favorite of copyright scholars, who have really fascinating disagreements and discussions about the subject. These discussions often key off of the controversies of the moment, but inevitably they implicate earlier fights about everything from the piano roll to 2 Live Crew to antiracist retellings of Gone With the Wind.

One of the most interesting discussions of fair use you can ask for took place in 2019, when the NYU Engelberg Center on Innovation Law & Policy held a symposium called "Proving IP." One of the panels featured dueling musicologists debating the merits of the Blurred Lines case. That case marked a turning point in music copyright, with the Marvin Gaye estate successfully suing Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams for copying the "vibe" of Gaye's "Got to Give it Up."

Naturally, this discussion featured clips from both songs as the experts – joined by some of America's top copyright scholars – delved into the legal reasoning and future consequences of the case. It would be literally impossible to discuss this case without those clips.

And that's where the problems start: as soon as the symposium was uploaded to Youtube, it was flagged and removed by Content ID, Google's $100,000,000 copyright enforcement system. This initial takedown was fully automated, which is how Content ID works: rightsholders upload audio to claim it, and then Content ID removes other videos where that audio appears (rightsholders can also specify that videos with matching clips be demonetized, or that the ad revenue from those videos be diverted to the rightsholders).

But Content ID has a safety valve: an uploader whose video has been incorrectly flagged can challenge the takedown. The case is then punted to the rightsholder, who has to manually renew or drop their claim. In the case of this symposium, the rightsholder was Universal Music Group, the largest record company in the world. UMG's personnel reviewed the video and did not drop the claim.

99.99% of the time, that's where the story would end, for many reasons. First of all, most people don't understand fair use well enough to contest the judgment of a cosmically vast, unimaginably rich monopolist who wants to censor their video. Just as importantly, though, is that Content ID is a Byzantine system that is nearly as complex as fair use, but it's an entirely private affair, created and adjudicated by another galactic-scale monopolist (Google).

Google's copyright enforcement system is a cod-legal regime with all the downsides of the law, and a few wrinkles of its own (for example, it's a system without lawyers – just corporate experts doing battle with laypeople). And a single mis-step can result in your video being deleted or your account being permanently deleted, along with every video you've ever posted. For people who make their living on audiovisual content, losing your Youtube account is an extinction-level event:

https://www.eff.org/wp/unfiltered-how-youtubes-content-id-discourages-fair-use-and-dictates-what-we-see-online

So for the average Youtuber, Content ID is a kind of Kafka-as-a-Service system that is always avoided and never investigated. But the Engelbert Center isn't your average Youtuber: they boast some of the country's top copyright experts, specializing in exactly the questions Youtube's Content ID is supposed to be adjudicating.

So naturally, they challenged the takedown – only to have UMG double down. This is par for the course with UMG: they are infamous for refusing to consider fair use in takedown requests. Their stance is so unreasonable that a court actually found them guilty of violating the DMCA's provision against fraudulent takedowns:

https://www.eff.org/cases/lenz-v-universal

But the DMCA's takedown system is part of the real law, while Content ID is a fake law, created and overseen by a tech monopolist, not a court. So the fate of the Blurred Lines discussion turned on the Engelberg Center's ability to navigate both the law and the n-dimensional topology of Content ID's takedown flowchart.

It took more than a year, but eventually, Engelberg prevailed.

Until they didn't.

If Content ID was a person, it would be baby, specifically, a baby under 18 months old – that is, before the development of "object permanence." Until our 18th month (or so), we lack the ability to reason about things we can't see – this the period when small babies find peek-a-boo amazing. Object permanence is the ability to understand things that aren't in your immediate field of vision.

Content ID has no object permanence. Despite the fact that the Engelberg Blurred Lines panel was the most involved fair use question the system was ever called upon to parse, it managed to repeatedly forget that it had decided that the panel could stay up. Over and over since that initial determination, Content ID has taken down the video of the panel, forcing Engelberg to go through the whole process again.

But that's just for starters, because Youtube isn't the only place where a copyright enforcement bot is making billions of unsupervised, unaccountable decisions about what audiovisual material you're allowed to access.

Spotify is yet another monopolist, with a justifiable reputation for being extremely hostile to artists' interests, thanks in large part to the role that UMG and the other major record labels played in designing its business rules:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

Spotify has spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to capture the podcasting market, in the hopes of converting one of the last truly open digital publishing systems into a product under its control:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/01/27/enshittification-resistance/#ummauerter-garten-nein

Thankfully, that campaign has failed – but millions of people have (unwisely) ditched their open podcatchers in favor of Spotify's pre-enshittified app, so everyone with a podcast now must target Spotify for distribution if they hope to reach those captive users.

Guess who has a podcast? The Engelberg Center.

Naturally, Engelberg's podcast includes the audio of that Blurred Lines panel, and that audio includes samples from both "Blurred Lines" and "Got To Give It Up."

So – naturally – UMG keeps taking down the podcast.

Spotify has its own answer to Content ID, and incredibly, it's even worse and harder to navigate than Google's pretend legal system. As Engelberg describes in its latest post, UMG and Spotify have colluded to ensure that this now-classic discussion of fair use will never be able to take advantage of fair use itself:

https://www.nyuengelberg.org/news/how-explaining-copyright-broke-the-spotify-copyright-system/

Remember, this is the best case scenario for arguing about fair use with a monopolist like UMG, Google, or Spotify. As Engelberg puts it:

The Engelberg Center had an extraordinarily high level of interest in pursuing this issue, and legal confidence in our position that would have cost an average podcaster tens of thousands of dollars to develop. That cannot be what is required to challenge the removal of a podcast episode.

Automated takedown systems are the tech industry's answer to the "notice-and-takedown" system that was invented to broker a peace between copyright law and the internet, starting with the US's 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The DMCA implements (and exceeds) a pair of 1996 UN treaties, the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the Performances and Phonograms Treaty, and most countries in the world have some version of notice-and-takedown.

Big corporate rightsholders claim that notice-and-takedown is a gift to the tech sector, one that allows tech companies to get away with copyright infringement. They want a "strict liability" regime, where any platform that allows a user to post something infringing is liable for that infringement, to the tune of $150,000 in statutory damages.

Of course, there's no way for a platform to know a priori whether something a user posts infringes on someone's copyright. There is no registry of everything that is copyrighted, and of course, fair use means that there are lots of ways to legally reproduce someone's work without their permission (or even when they object). Even if every person who ever has trained or ever will train as a copyright lawyer worked 24/7 for just one online platform to evaluate every tweet, video, audio clip and image for copyright infringement, they wouldn't be able to touch even 1% of what gets posted to that platform.

The "compromise" that the entertainment industry wants is automated takedown – a system like Content ID, where rightsholders register their copyrights and platforms block anything that matches the registry. This "filternet" proposal became law in the EU in 2019 with Article 17 of the Digital Single Market Directive:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2018/09/today-europe-lost-internet-now-we-fight-back

This was the most controversial directive in EU history, and – as experts warned at the time – there is no way to implement it without violating the GDPR, Europe's privacy law, so now it's stuck in limbo:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/05/eus-copyright-directive-still-about-filters-eus-top-court-limits-its-use

As critics pointed out during the EU debate, there are so many problems with filternets. For one thing, these copyright filters are very expensive: remember that Google has spent $100m on Content ID alone, and that only does a fraction of what filternet advocates demand. Building the filternet would cost so much that only the biggest tech monopolists could afford it, which is to say, filternets are a legal requirement to keep the tech monopolists in business and prevent smaller, better platforms from ever coming into existence.

Filternets are also incapable of telling the difference between similar files. This is especially problematic for classical musicians, who routinely find their work blocked or demonetized by Sony Music, which claims performances of all the most important classical music compositions:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/05/08/copyfraud/#beethoven-just-wrote-music

Content ID can't tell the difference between your performance of "The Goldberg Variations" and Glenn Gould's. For classical musicians, the best case scenario is to have their online wages stolen by Sony, who fraudulently claim copyright to their recordings. The worst case scenario is that their video is blocked, their channel deleted, and their names blacklisted from ever opening another account on one of the monopoly platforms.

But when it comes to free expression, the role that notice-and-takedown and filternets play in the creative industries is really a sideshow. In creating a system of no-evidence-required takedowns, with no real consequences for fraudulent takedowns, these systems are huge gift to the world's worst criminals. For example, "reputation management" companies help convicted rapists, murderers, and even war criminals purge the internet of true accounts of their crimes by claiming copyright over them:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/04/23/reputation-laundry/#dark-ops

Remember how during the covid lockdowns, scumbags marketed junk devices by claiming that they'd protect you from the virus? Their products remained online, while the detailed scientific articles warning people about the fraud were speedily removed through false copyright claims:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/18/labor-shortage-discourse-time/#copyfraud

Copyfraud – making false copyright claims – is an extremely safe crime to commit, and it's not just quack covid remedy peddlers and war criminals who avail themselves of it. Tech giants like Adobe do not hesitate to abuse the takedown system, even when that means exposing millions of people to spyware:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/13/theres-an-app-for-that/#gnash

Dirty cops play loud, copyrighted music during confrontations with the public, in the hopes that this will trigger copyright filters on services like Youtube and Instagram and block videos of their misbehavior:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/02/10/duke-sucks/#bhpd

But even if you solved all these problems with filternets and takedown, this system would still choke on fair use and other copyright exceptions. These are "fact intensive" questions that the world's top experts struggle with (as anyone who watches the Blurred Lines panel can see). There's no way we can get software to accurately determine when a use is or isn't fair.

That's a question that the entertainment industry itself is increasingly conflicted about. The Blurred Lines judgment opened the floodgates to a new kind of copyright troll – grifters who sued the record labels and their biggest stars for taking the "vibe" of songs that no one ever heard of. Musicians like Ed Sheeran have been sued for millions of dollars over these alleged infringements. These suits caused the record industry to (ahem) change its tune on fair use, insisting that fair use should be broadly interpreted to protect people who made things that were similar to existing works. The labels understood that if "vibe rights" became accepted law, they'd end up in the kind of hell that the rest of us enter when we try to post things online – where anything they produce can trigger takedowns, long legal battles, and millions in liability:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/04/08/oh-why/#two-notes-and-running

But the music industry remains deeply conflicted over fair use. Take the curious case of Katy Perry's song "Dark Horse," which attracted a multimillion-dollar suit from an obscure Christian rapper who claimed that a brief phrase in "Dark Horse" was impermissibly similar to his song "A Joyful Noise."

Perry and her publisher, Warner Chappell, lost the suit and were ordered to pay $2.8m. While they subsequently won an appeal, this definitely put the cold grue up Warner Chappell's back. They could see a long future of similar suits launched by treasure hunters hoping for a quick settlement.

But here's where it gets unbelievably weird and darkly funny. A Youtuber named Adam Neely made a wildly successful viral video about the suit, taking Perry's side and defending her song. As part of that video, Neely included a few seconds' worth of "A Joyful Noise," the song that Perry was accused of copying.

In court, Warner Chappell had argued that "A Joyful Noise" was not similar to Perry's "Dark Horse." But when Warner had Google remove Neely's video, they claimed that the sample from "Joyful Noise" was actually taken from "Dark Horse." Incredibly, they maintained this position through multiple appeals through the Content ID system:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/03/05/warner-chappell-copyfraud/#warnerchappell

In other words, they maintained that the song that they'd told the court was totally dissimilar to their own was so indistinguishable from their own song that they couldn't tell the difference!

Now, this question of vibes, similarity and fair use has only gotten more intense since the takedown of Neely's video. Just this week, the RIAA sued several AI companies, claiming that the songs the AI shits out are infringingly similar to tracks in their catalog:

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/record-labels-sue-music-generators-suno-and-udio-1235042056/

Even before "Blurred Lines," this was a difficult fair use question to answer, with lots of chewy nuances. Just ask George Harrison:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Sweet_Lord

But as the Engelberg panel's cohort of dueling musicologists and renowned copyright experts proved, this question only gets harder as time goes by. If you listen to that panel (if you can listen to that panel), you'll be hard pressed to come away with any certainty about the questions in this latest lawsuit.

The notice-and-takedown system is what's known as an "intermediary liability" rule. Platforms are "intermediaries" in that they connect end users with each other and with businesses. Ebay and Etsy and Amazon connect buyers and sellers; Facebook and Google and Tiktok connect performers, advertisers and publishers with audiences and so on.

For copyright, notice-and-takedown gives platforms a "safe harbor." A platform doesn't have to remove material after an allegation of infringement, but if they don't, they're jointly liable for any future judgment. In other words, Youtube isn't required to take down the Engelberg Blurred Lines panel, but if UMG sues Engelberg and wins a judgment, Google will also have to pay out.

During the adoption of the 1996 WIPO treaties and the 1998 US DMCA, this safe harbor rule was characterized as a balance between the rights of the public to publish online and the interest of rightsholders whose material might be infringed upon. The idea was that things that were likely to be infringing would be immediately removed once the platform received a notification, but that platforms would ignore spurious or obviously fraudulent takedowns.

That's not how it worked out. Whether it's Sony Music claiming to own your performance of "Fur Elise" or a war criminal claiming authorship over a newspaper story about his crimes, platforms nuke first and ask questions never. Why not? If they ignore a takedown and get it wrong, they suffer dire consequences ($150,000 per claim). But if they take action on a dodgy claim, there are no consequences. Of course they're just going to delete anything they're asked to delete.

This is how platforms always handle liability, and that's a lesson that we really should have internalized by now. After all, the DMCA is the second-most famous intermediary liability system for the internet – the most (in)famous is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This is a 27-word law that says that platforms are not liable for civil damages arising from their users' speech. Now, this is a US law, and in the US, there aren't many civil damages from speech to begin with. The First Amendment makes it very hard to get a libel judgment, and even when these judgments are secured, damages are typically limited to "actual damages" – generally a low sum. Most of the worst online speech is actually not illegal: hate speech, misinformation and disinformation are all covered by the First Amendment.

Notwithstanding the First Amendment, there are categories of speech that US law criminalizes: actual threats of violence, criminal harassment, and committing certain kinds of legal, medical, election or financial fraud. These are all exempted from Section 230, which only provides immunity for civil suits, not criminal acts.

What Section 230 really protects platforms from is being named to unwinnable nuisance suits by unscrupulous parties who are betting that the platforms would rather remove legal speech that they object to than go to court. A generation of copyfraudsters have proved that this is a very safe bet:

https://www.techdirt.com/2020/06/23/hello-youve-been-referred-here-because-youre-wrong-about-section-230-communications-decency-act/

In other words, if you made a #MeToo accusation, or if you were a gig worker using an online forum to organize a union, or if you were blowing the whistle on your employer's toxic waste leaks, or if you were any other under-resourced person being bullied by a wealthy, powerful person or organization, that organization could shut you up by threatening to sue the platform that hosted your speech. The platform would immediately cave. But those same rich and powerful people would have access to the lawyers and back-channels that would prevent you from doing the same to them – that's why Sony can get your Brahms recital taken down, but you can't turn around and do the same to them.

This is true of every intermediary liability system, and it's been true since the earliest days of the internet, and it keeps getting proven to be true. Six years ago, Trump signed SESTA/FOSTA, a law that allowed platforms to be held civilly liable by survivors of sex trafficking. At the time, advocates claimed that this would only affect "sexual slavery" and would not impact consensual sex-work.

But from the start, and ever since, SESTA/FOSTA has primarily targeted consensual sex-work, to the immediate, lasting, and profound detriment of sex workers:

https://hackinghustling.org/what-is-sesta-fosta/

SESTA/FOSTA killed the "bad date" forums where sex workers circulated the details of violent and unstable clients, killed the online booking sites that allowed sex workers to screen their clients, and killed the payment processors that let sex workers avoid holding unsafe amounts of cash:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2022/09/fight-overturn-fosta-unconstitutional-internet-censorship-law-continues

SESTA/FOSTA made voluntary sex work more dangerous – and also made life harder for law enforcement efforts to target sex trafficking:

https://hackinghustling.org/erased-the-impact-of-fosta-sesta-2020/

Despite half a decade of SESTA/FOSTA, despite 15 years of filternets, despite a quarter century of notice-and-takedown, people continue to insist that getting rid of safe harbors will punish Big Tech and make life better for everyday internet users.

As of now, it seems likely that Section 230 will be dead by then end of 2025, even if there is nothing in place to replace it:

https://energycommerce.house.gov/posts/bipartisan-energy-and-commerce-leaders-announce-legislative-hearing-on-sunsetting-section-230

This isn't the win that some people think it is. By making platforms responsible for screening the content their users post, we create a system that only the largest tech monopolies can survive, and only then by removing or blocking anything that threatens or displeases the wealthy and powerful.

Filternets are not precision-guided takedown machines; they're indiscriminate cluster-bombs that destroy anything in the vicinity of illegal speech – including (and especially) the best-informed, most informative discussions of how these systems go wrong, and how that blocks the complaints of the powerless, the marginalized, and the abused.

Support me this summer on the Clarion Write-A-Thon and help raise money for the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop!

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/06/27/nuke-first/#ask-questions-never

Image: EFF https://www.eff.org/files/banner_library/yt-fu-1b.png

CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#vibe rights#230#section 230#cda 230#communications decency act#communications decency act 230#cda230#filternet#copyfight#fair use#notice and takedown#censorship#reputation management#copyfraud#sesta#fosta#sesta fosta#spotify#youtube#contentid#monopoly#free speech#intermediary liability

677 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I got a patently obvious false Content ID claim the other day.

After arguing with YouTube about how the heck did it even pass their systems for a few hours on X, I decided this was more productive.

Enjoy the song!

#youtube#youtube shorts#music#metal#lo-fi#lofi metal#vtuber#vtuber takeover#3d vtuber#indie vtuber#vtuber uprising#streamer#vtuberen#contentid

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Content ID vs. Manual Claims: A Comparison for Musicians

The rise of digital platforms like YouTube has transformed the way musicians protect their work, earn revenue, and manage copyright claims. For musicians, navigating copyright claims on these platforms typically involves two main methods: Content ID and manual claims. While both options allow musicians to control the use of their music and enforce their rights, they serve different purposes and come with distinct advantages and disadvantages. This article explores the differences between Content ID and manual claims, examining how each system works, when to use each approach, and strategies for handling disputes, revenue sharing, and balancing exposure with copyright protection.

What is Content ID?

Content ID is an automated copyright management system used by YouTube to detect and manage copyrighted content. It scans every video uploaded to YouTube against a database of copyrighted works, such as songs, videos, and other media, submitted by copyright holders. If a video contains copyrighted material that matches the database, Content ID automatically places a claim on the video, giving the rights holder the option to monetize, block, or track it.

For musicians, Content ID can be an effective tool for managing their work on digital platforms. It allows musicians to automate the process of detecting and claiming unauthorized uses of their music, which can be especially valuable for artists who might lack the time and resources for manual enforcement.

What is a Manual Claim?

Unlike Content ID, a manual claim is initiated by a copyright owner or their representative who manually identifies a case of copyright infringement. Instead of relying on automated detection, manual claims require someone to review the content, verify the infringement, and file a copyright claim manually through the platform’s copyright reporting system.

Manual claims can be beneficial for musicians in cases where Content ID may fail to detect usage due to factors such as altered audio, pitch changes, or remixes that change the music just enough to avoid automatic detection. Manual claims are often used by labels or publishers who employ teams dedicated to protecting their artists' copyrights and are able to manually monitor and file claims when needed.

Content ID vs. Manual Claims: Key Differences

While both Content ID and manual claims help musicians protect their work, they differ in various ways:

Detection and Enforcement:

Content ID: Automatic and algorithm-based. It can quickly detect uses of copyrighted material based on an audio or visual match within its database.

Manual Claims: Human-driven and initiated by a copyright holder or representative. It requires manual identification and filing, making it more labor-intensive but potentially more accurate in detecting altered or remixed content.

Control and Flexibility:

Content ID: Offers standardized options for monetization, tracking, or blocking, but limited flexibility in handling unique or altered uses. Content ID’s automated approach might struggle with nuanced copyright issues, such as fair use or derivative works.

Manual Claims: Provides greater control for copyright holders to evaluate each case individually. Since a manual claim is initiated by a person, the copyright holder can assess context, fair use, and the nature of the infringement more carefully.

Speed and Efficiency:

Content ID: Extremely efficient and capable of detecting matches within minutes of a video being uploaded. For musicians with a large volume of copyrighted material, this can save time and allow for swift copyright enforcement.

Manual Claims: Slower and more time-consuming, as it requires individual review. It’s best suited for cases where automatic detection may not be effective or when the copyright holder wants to be selective about claims.

Cost and Resources:

Content ID: Generally accessible at a low cost or included as part of digital distribution services. Musicians typically don’t need a team to monitor Content ID, as the process is automated.

Manual Claims: Often requires a dedicated team or legal support, especially if the musician’s work is widely distributed or vulnerable to frequent infringement. Independent artists may find manual claims too resource-intensive unless they have specific cases that require close monitoring.

When to Use Content ID vs. Manual Claims

For musicians, choosing between Content ID and manual claims depends on the nature of their music, their copyright protection goals, and the level of control they want over enforcement. Here are some scenarios where each method might be more suitable:

Use Content ID When:

You want to automate copyright detection across a large volume of uploads.

Your music is frequently used by fans, and you want to monetize these uses without manually reviewing each case.

You lack the time or resources to monitor infringement manually and prefer an efficient solution.

Your music doesn’t often appear in altered formats, such as remixes or pitched versions.

Use Manual Claims When:

You need to enforce copyright on altered versions of your music that Content ID may not detect.

You want more control over the enforcement process, especially for cases involving fair use, remixes, or covers.

You have a team or partner (like a label or distributor) who can manage manual claims for you.

You’re dealing with high-profile content where maintaining control over brand perception or artistic integrity is essential.

Handling Disputes and Appeals

Disputes are common when copyright claims are made on platforms like YouTube, and both Content ID and manual claims come with their own challenges in this area. Here’s how musicians can handle disputes and appeals effectively:

Disputes with Content ID Claims:

When a user disputes a Content ID claim, the copyright holder has the option to review and either release or uphold the claim.

To handle disputes effectively, musicians should ensure they have proof of ownership, such as registrations with a PRO (Performing Rights Organization) or contracts showing ownership.

Musicians should also consider whether the user’s claim of fair use is valid. If the user’s content is a parody, critique, or educational in nature, releasing the claim might be more appropriate to avoid legal entanglements.

Disputes with Manual Claims:

Manual claims give musicians more control during the dispute process, as they can provide customized responses and additional context.

When dealing with disputes on manually filed claims, musicians should review the details of the disputed video and respond accordingly. For example, if a remix is involved, they may choose to uphold the claim and monetize it rather than blocking it outright.

Revenue Sharing and Monetization Strategies

Both Content ID and manual claims allow musicians to monetize copyrighted material, but each system comes with its own revenue-sharing implications. Here’s what musicians should consider when it comes to monetization:

Revenue Splits: On platforms like YouTube, ad revenue generated from claimed videos is split between YouTube and the rights holder. Content ID typically provides set revenue splits, but manual claims may allow for more personalized arrangements, especially if negotiated with the content creator.

Collaborative Monetization: Content ID can be used to allow shared monetization on fan-generated content, such as tribute videos or fan remixes. Instead of blocking all uses, musicians can use Content ID to generate revenue while allowing fans to share their creativity.

Custom Monetization Approaches: Manual claims offer more flexibility in revenue arrangements. For instance, if a musician collaborates with another artist who uses a sample, the two parties can work out a revenue-sharing agreement before manually claiming the content.

Balancing Exposure and Copyright Protection

One of the challenges musicians face is balancing exposure with copyright enforcement. For some artists, fan-generated content, covers, or remixes can drive exposure and build an audience. Here’s how musicians can use Content ID and manual claims strategically:

Content ID for Broader Exposure: By allowing Content ID to track or monetize content rather than block it, musicians can increase exposure while still generating revenue. This approach works well for emerging artists who want to let fans share their work.

Selective Manual Claims for High-Value Content: For high-profile work or exclusive releases, musicians may prefer manual claims to maintain control over brand perception and artistic quality. Selective manual enforcement can ensure that valuable content isn’t diluted or used in a way that detracts from its original impact.

Final Thoughts

Both Content ID and manual claims offer valuable tools for musicians, but understanding their differences is crucial for effective copyright management. Content ID is ideal for broad, automated copyright protection, making it suitable for most musicians who want to monetize their work without hands-on management. Manual claims, on the other hand, offer greater control and customization, allowing musicians to handle unique or complex cases that Content ID might miss.

For musicians, leveraging these tools in combination can provide the best of both worlds: automated protection with Content ID for widespread exposure and selective manual enforcement for high-value content. As the digital landscape evolves, musicians who understand and strategically apply both methods can maximize their revenue, control, and visibility, building a sustainable career while protecting their creative work in the digital age.

0 notes

Text

Content ID On YouTube, Other Creator/Artist Protection Tools

There are further ways to safeguard creators and artists, like content ID on YouTube.

The commitment they make to developing AI responsibly

AI is creating a plethora of opportunities and enabling artists to express themselves in novel and fascinating ways. At YouTube, they’re dedicated to making sure that other businesses and artists prosper in this dynamic environment. This entails giving people the instruments necessary to fully use AI’s creative potential while preserving their authority over the representation of their identity, including their voice and visage. currently creating new likeness management technologies to do this, which will protect them and open up new doors down the road.

Instruments they are creating

First, partners will be able to automatically identify and control artificial intelligence (AI)-generated video on YouTube that mimics their singing voices thanks to new synthetic-singing recognition technology created by Google under Content ID on YouTube. They are working with their partners to refine this technology, and early in the next year, a pilot program is scheduled.

Second, you’re working hard to build new technologies that will make it possible for individuals in a range of fields from artists and sports to actors and creators to recognize and control artificial intelligence (AI)-generated material on YouTube that features their faces. This, together with their most recent privacy changes, will provide a powerful toolkit to control the way AI is used to represent individuals on YouTube.

These two new capacities expand on their history of creating technology-driven strategies for large-scale rights concerns management. Since its launch in 2007, Content ID on YouTube has given rightsholders on YouTube granular control over their entire portfolios, processing billions of claims annually and bringing in billions more for artists and creators via the reuse of their creations. Currently determined to introduce the same degree of security and autonomy into the era of artificial intelligence.

Preventing unwanted access to material and giving users more control

It utilize material submitted to YouTube, as they have done for many years, to enhance the user experience for creators and viewers on both YouTube and Google, including via the use of AI and machine learning tools. Please adhere to the conditions set out by the founders in doing this. This includes building new generative AI capabilities like auto dubbing and supporting their Trust & Safety operations as well as enhancing their recommendation algorithms. Going ahead, it’s still dedicated to making sure that YouTube material is utilized appropriately across Google or YouTube for the creation of their AI-powered solutions.

Regarding third parties, including those who would attempt to scrape YouTube material, they have made it quite clear that gaining illegal access to creator content is against their Terms of Service and lessens the value they provide to creators in return for their labor. Help keep taking steps to make sure that third parties abide by these rules, such as making continuous investments in the systems that identify and stop illegal access, all the way up to banning access for scrapers.

Having said that, they understand that as the field of generative AI develops, artists could want greater control over the terms of their partnerships with other businesses to produce AI tools. Currently creating new methods to offer YouTube creators control over how other parties may utilize their video on their platform because of this. Later this year, it will be able to reveal more.

Using Community Guidelines & AI Tools

The experimental Dream Screen for Shorts and other new generative AI tools on YouTube provide artists with new and interesting avenues to express their creativity and interact with their audience. The creative process is still in the creators’ control; they direct the tools’ output and choose what information to disclose.

Google commitment to building a responsible and secure community includes handling information produced by artificial intelligence. AI-generated material has to follow their Community Guidelines, just like any other YouTube video. In the end, creators are in charge of making sure their published work complies with these criteria, regardless of where it came from.

They’ve added safety features to their AI tools to help developers navigate it regulations and avoid any possible abuse. This implies that suggestions that break the rules or deal with delicate subjects may be blocked. They urge artists to thoroughly check AI-generated work before posting it, just as they would in any other scenario, even if their main objective is to inspire creativity. Google recognize they may not always get it right, especially in the early days of new goods, so they welcome input from creators.

Fostering creativity in people

They think that as AI develops, human creativity should be enhanced rather than replaced. Currently determined to collaborate with others to make sure that their opinions are heard in future developments, and it will keep creating safeguards to allay worries and accomplish their shared objectives. Since the beginning, they have concentrated on giving companies and artists the tools they need to create vibrant communities on YouTube, as well as still prioritize creating an atmosphere that encourages responsible innovation.

Read more on Govindhtech.com

#ContentID#YouTube#Creator#ProtectionTools#artificialintelligence#AI#Google#machinelearning#generativeAI#news#technews#technology#technologynews#technologytrends#govindhtech

1 note

·

View note

Text

CopyRight Content Detected

0 notes

Note

How much would it cost to get you to cover some of One Piece? Let's say the East Blue Saga?

A CONSIDERABLE amount of money, honestly. Putting aside that I am VERY reluctant to review manga nowadays because of getting my first ever legit copyright strikes on printed media reviews from the Longbox Uzumaki videos, I know there's a history of popular creators who havve gotten strikes and contentID claims on One Piece in particular, so I am iffy to do anything with it.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worse than serial killers

Engles coined the term "social murder" to describe what companies like United Heath does to everyday citizens

Luigi Mangione's (Alleged UHC CEO killer) review for the Unabomber Manifesto

The McDonald’s employee who called the police

Mcdonald's Being Hit With Negative Reviews

Luigi Mangione's X Account. Fucking McDonald's

https://x.com/pepmangione?lang=en

I added some screenshots for when the account is taken down that show a bit of the thinking that probably led to the adjustment.

Edit: Also fuck me. I didn't know the feelings on Twitter links (do we just hate Twitter or are we infosec scared?). Was just trying to share the social media link. Check out the pics in comments so you don't need to open.

Edit 2: Ol' Elon suspended the account. Scroll all the way through to see various screenshots.

Edit 3: Many people, faced with fighting insurance companies, simply give up: One study found that Americans file formal appeals on only 0.1% of claims denied by insurers under the Affordable Care Act.(https://www.propublica.org/article/unitedhealth-healthcare-insurance-denial-ulcerative-colitis)

You require better care that they aren't providing for you, you need to file a formal appeal right now. Do it right now.

Various resources you may find helpful:

https://www.healthcare.gov/appeal-insurance-company-decision/

https://www.healthcare.gov/marketplace-appeals/appeal-form-instructions-s/

https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/consumer-health-insurance-appeal-denied-claims.pdf

https://www.cms.gov/marketplace/in-person-assisters/applications-forms-notices/eligibility-appeals

https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=34&contentid=20275-1

https://www.patientadvocate.org/explore-our-resources/insurance-denials-appeals/things-to-include-in-your-appeal-letter/

Feel free to copy and paste this everywhere!

Credit to u/trtlclb

#brian thompson#rest in piss#rest in pieces#rotinpiss#rot in hell#united healthcare#unitedhealth group inc#uhc shooter#uhc ceo#uhc assassin#uhc generations#uhc lb#uhc#usa is a terrorist state#usa is funding genocide#usa politics#usa news#usaclothing#usafashion#usa#american indian#american#america#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

39. The door does the choosing, not the man.

Jorge Luis Borges, Fragments of an Apocryphal Evangelist (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?contentId=38928)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

City News | Pflugerville, TX - Official Website

https://www.pflugervilletx.gov/890/City-News?contentId=cc03b4d6-438f-4685-a555-b1ebebe076e8

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

i don't know if you saw because the video doesn't show it, but pecco did also include an eye on the top of his helmet (likely as a reference to the alice eye which i noticed first because it is one of my favourite sponsor logos)

sport.quotidiano . net/image-service/view/acePublic/alias/contentid/M2QwYzM1YmEtODVlYy00/0/

also in the category of 'fully just forgot to answer this' but yeah i LOVE it, very nicely integrated in his usual preferred helmet style. subtle enough to look natural but still looks like a deliberate reference. and obviously i am a long term (read: since i got an ask about it, since i apparently just don't notice sponsors off my own accord even if i've seen them a million times #marxismwin) eye enjoyer, i am a big fan of this throwback to an era where you had eyes everywhere to add symbolic flair to the scenery

this one and the anal sex one truly the goats of late noughties motogp advertising, glad one rider on the current grid at least knows his herstory

#does have to be said. too many sponsors#but ik from silverstone pecco is right there with me on this#pecco being both a vale and casey fan as a kid truly so precious 2 me like he Got It. a true intellectual#what if YOU were fighting for your first premier class title and you messaged BOTH your childhood heroes to give you tips in race weekends#pecco killing himself in front of valentino and forever changing the trajectory of his life#for having casey over the week before his title decider. timing admittedly wasn't valentino's fault but#//#brr brr#//ht#//currt#batsplat responds#//brr brr

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

JUNE 2002

1 - Launch.Com. Publishes an interview in which JC responds to a question about the group’s hiatus.

Title: Matinee Idols

Author(s): David John Farinella

Original Source: Launch.com

Current link(s): https://web.archive.org/web/20021025064128/http://launch.yahoo.com/read/feature.asp?contentID=209140

2 - Popdirt.com published a transcript of a telephone interview Justin did on TRL. This graphic features the portion of the transcript pertaining to Justin’s solo album.

Title: Justin Timberlake Phones Carson On TRL

Author(s): Unknown

Original Source: MTV Network Broadcast (unavailable)

Secondary Source: Popdirt.com

Current link: http://popdirt.com/justin-timberlake-phones-carson-on-trl/5111/#more-5111 (full transcript)

3 and 4 - On June 13th Melinda Bell posted another update in her journal on NSYNC.com. These graphic contain direct quotes from the journal entry.

Author(s): Melinda Bell

Title: Melinda’s Corner

Original Source: Nsync.com/melindas_corner.html

Current Link: http://web.archive.org/20030425162735/nsync.com/melindas_corner.html

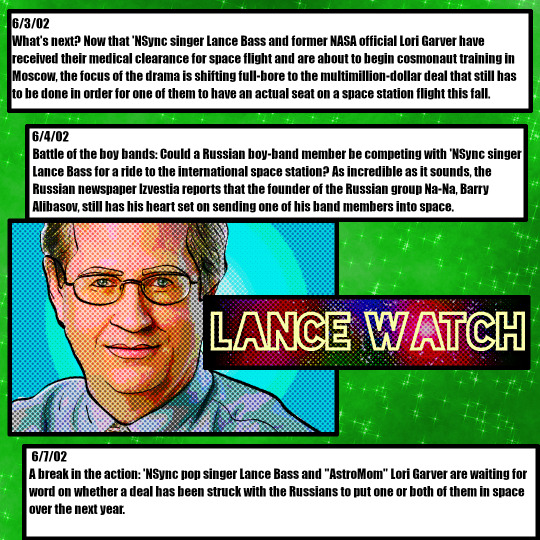

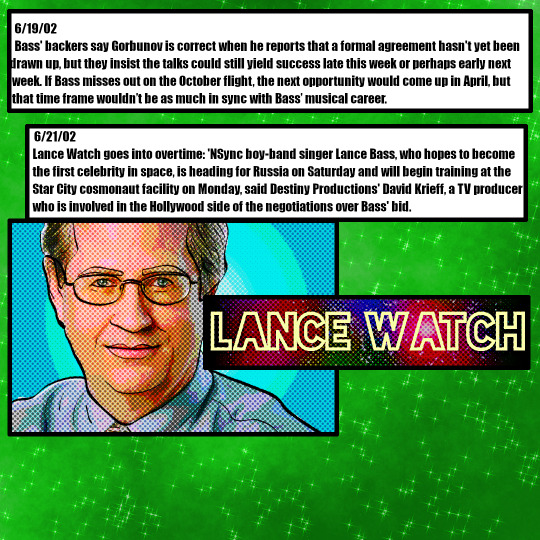

5, 6, and 7 - Alan Boyle’s Cosmic Log on MSNBC.Com featured semi-regular updates about Lance’s cosmonaut training and aspirations. These graphics feature direct excerpts taken from Boyle’s blog entries.

Title: Cosmic Log

Author(s): Alan Boyle

Original Source: MSNBC.com (blog no longer available)

Secondary Source: Cosmiclog.com

Current Link: https://cosmiclog.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/coslog-archive1.docx (MS Word Document containing archived MSNBC blog posts)

#jc chasez#lance bass#nsync#joey fatone#chris kirkpatrick#celeb gossip#boy bands#2000s music#teen pop#archiving#y2k nostalgia#justin timberlake#boyband#breakup#celeb news#mtv trl#total request live#mtv#outer space#popdirt

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/alexbkrieger13/782159924718452736/httpswwwtumblrcomalexbkrieger137821574655434?source=share

I found it here: https://www.dazn.com/fixture/ContentId:47ct6fp590ops4v7aktmrgp3o/ArticleId:43vqydjbhhqnjqkie0ryusfmz/43vqydjbhhqnjqkie0ryusfmz

but you might have to be in germany and have a dazn subscription to watch it.

Why do they have to geoblock everything

1 note

·

View note

Text

Okay im just gonna do a little post. Opsec basics for the MCR fandom

I know everyone’s Hingry and super into all this. I am too. But I’m seeing a lot of bad OpSec practice around with regards to the leaked files. So here’s just some info and protips.

We’re not dealing here with normal pirated or extralegal data like a pirated album. We’re dealing with leaked data, in some cases data that was part of a massive data leak. This warrants significantly more caution and care in handling. DMCA takedowns are going to be swifter & harder & this is significantly more legally sketchy in a lot of ways, and I suspect the original leakers of the big Warner leak could be looking at legal trouble if they get found.

With that in mind, here’s some tips going forwards.

When dealing with pirated or leaked data, the absolute number one key is to Not Draw Attention. Many piracy sites & people manage this by simply not sharing anything at all on the open net. This isn’t always feasible in the interest of sharing, and is sometimes counter to the ethos of sharing and piracy. So the second best thing is to NOT DRAW ATTENTION TO OURSELVES. So with that in mind:

- stop uploading witch to Spotify. Please. I know people want it there to go in playlists and stuff but please perform a stop it. Warner is going to DMCA that stuff sooner than later and you really really do not want to be the account that uploaded it.

- stop uploading Witch to YouTube. One person did it, confirmed the contentID exists. Okay great. Don’t do it anymore. Stop ringing this alarm bell.

- don’t use cloud storage to do any permanent storage of files from the leaks, ESPECIALLY not google drive or Dropbox which are both providers that do content ID ON PRIVATE PERSONAL FILES. We know, from the YouTube stuff, that Witch at least, if not the rest of TPK, is in comtentID. This will eventually get sniped too. Do not count on clouds as permanent storage for ANYTHING related to this.

- if you are using cloud storage to share and distribute data from the leaks, use more copyright ambivalent services like Mega and use burner accounts to do so.

- anything you actually care about and like and want to keep, DOWNLOAD. Locally. Onto your hard drive. That is literally the only place it’ll be safe.

- If you feel brave and want to interface with/download the actual big Warner leaks torrent, do so through a VPN or with a seedbox. Do NOT get your personal IP into the peer swarm on that fucker. That is not a sound or safe thing to be associated with in any traceable capacity. USE A VPN.

- probably stop making us so known & seen on leaked. I’m seeing a lot of new accounts on the leaked threads asking about MCR stuff. I get it, I really really do, and one or two asks is fine, but it’s probably drawing too much attention by now. If you want to stalk leaked, make the account (use a burner email p l e a s e) and Lurk. Pirates and leakers are territorial assholes and leaked is effectively the darkweb. An influx of new blood with an obvious single fandom interest has the potential to be poorly received and get eyes on us we don’t want from multiple different directions. Again, less alarm bells.

I know this is all a bit dramatic and overly serious and everyone can mock me if they like. But I think it’s important to remember that, with the Witch mp3 and the HA stuff from the Warner leak, we’re all doing something most of us aren’t actually used to, which is dealing with data that isn’t just pirated or semi-legal but part of significant data crime. I’m not in any way suggesting to stop sharing or talking about it, and each person’s personal ethical opinion on that is their own. But I do think we all need to be more careful from a technological and security standpoint with how we’re distributing this data and what spaces we’re uploading it. Warner IS going to be watching and we do NOT want them to see us.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

what's your buissness uploading videos with limited access to your old channels, that are seemingly forgotten? Is it some tax evasion scheme? Just curius

ALMOST! Test uploads to see if contentID will flag the movie clips or the music I am using. Sometimes it only flags AFTER the video goes public, so I gotta jump every hoop and test for that too

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is funny how a washing machine chime is being used to demonitized videos.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've noticed with Longbox that after Gyo, it seems you've stuck mostly with Junji Ito's short story collections. Do you ever intend to cover more long form stories like Black Paradox, Dissolving Classroom, Sensor, and Liminal Zone, or are you saving those until you've done all the collections? Also, would you consider doing an Ashock the Fourth Wall seriesl for Tomie like you did with Remina?

Unfortunately, I'm not doing ANY Junji Ito in the future. In case you missed it, the three Uzumaki Longbox videos AND the AT4W live shows featuring them got taken down and I got two copyright strikes from them. Not ContentID claims - copyright strikes, as in the things that can get my channel deleted. Sooo yeah, I can't risk covering Junji Ito material again in the future.

47 notes

·

View notes