#depending on how high her alcohol levels were. she might need to go to jail for a little while

Text

:((

#the sky speaks#vent moment again ✨#moms not coping well#i can hear her sobbing up there rn#she took a shower at least#depending on how high her alcohol levels were. she might need to go to jail for a little while#but we still don't know and the anticipation is killing her#it could be upwards of a 5k fine#and ahes probably going back to rehab or something like it#im at the point where im not really feeling anything anymore#some good things have happened tho#i took a walk at the park yesterday#and like 10 minutes in. i squint at a figure across the park and i go. is that my fucking brother???#so i call him. and he doesbt pick up. typical. and then i call his gf instead and she picks up and im like heyyy. r u at the park rn?#and turns out yes it was them and we meet up and shoot a basketball for like an hr and just chill#it was nice#they told me i can crash at their place whenever#but then i get home again and its just ao fucking quiet here#im starting to hate the quiet

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bad Manners (S2, E5)

My time-stamped thoughts for this episode. As always I reference Malcolm’s mental health. A lot. So if that’s going to be a trigger for you, don’t keep reading.

SPOILERS AHEAD:

0:35 - Martin totally thought John Watkins abducted and killed Ainsley. Mark my words.

0:44 - Holy. Shit. Ainsley is FIVE years old (or younger) here right? A five year old with that much determination?!?! She literally stayed silent in that clock for probably hours......and no one was concerned about this kid when Martin was arrested because...?

1:09 - Anyone else impressed with Malcolm’s aim here? Just me?

1:20 - Gil and Malcolm talking about sleep and murder is so freaking sweet. <3 Honestly, they’re acting like friends instead of co-workers and it warms my cold dead heart.

1:29 - Does Gil become a grumpy old man when he doesn’t get 8 hours sleep? I really want to know now.

1:39 - OMG. Gil pointing at Ainsley here is hilarious. He’s totally acting like some weird mix of a stern pissed off high-school teacher, and a step-dad trying to discipline an unruly teen. hahaha AND MALCOLM’S FACE. Look how done Malcolm is. He looks so so tired, sad, and exasperated.

1:44 - Wow. Girl power. Ainsley has those camera guys bending to her will. I honestly would’ve thought they would just read the situation and turn the camera off themselves.

1:47 - “It’s not a game.” Yikes. I have thoughts about this:

Malcolm is right - it’s not a game.

Malcolm is a bit of a hypocrite for saying that to Ainsley. Although, to his credit even when Malcolm is excited/inappropriately happy about murder it’s always pretty clear that he thinks murder is wrong, and that he has sympathy for the victims and their families.

Ainsley does not have that same sympathy for the victims. That much is clear later in this episode.

Pretty sure the writers are trying to turn Ainsley into a serial killer this season.

2:13 - “You know I like to share these things with my friends.” .....does this mean Malcolm thinks Dani and JT are his friends now? Last I checked (Ep 1x05) Malcolm didn’t have friends. This absolutely melts my heart. <3 I’m honestly so happy that Malcolm considers someone other than Gil to be his friend.

2:18 - “We lost Dani to vice.” .....What is vice? AND WHAT IS THE REAL LIFE REASON THAT DANI WASN’T IN THIS EPISODE?!?

2:19 - Edrisa has a medical degree right? She has to know how dangerous consuming that much caffeine is right? Plus aren’t energy drinks super dangerous if you drink a lot of them (or maybe that’s just what adults in my neighbourhood told kids)?

2:30 - Edrisa SHINES in this episode. She’s so funny and awkward and I just love her.

2:36 - hahaha Gil has adopted the whole team. Look at him throwing the “Dad warning stare” at Edrisa.

3:31 - Why does Edrisa start bouncing around looking upset when Malcolm says, “rejection is a powerful motivator”?!?! Has she recently been broken up with or something? Is this a reference to how she has a crush on Malcolm (who doesn’t reciprocate)? I WANT MORE INFORMATION.

3:47 - TWIZZLERS!!! <3 Damn I love how this tiny detail about Malcolm’s character keeps coming up.

3:55 - Ainsley is on a rampage this episode. She’s so determined ...actually she’s acting a lot like Jessica (think girl in the box bracelet). However, unlike Jessica, Ainsley’s motives aren’t about justice or the safety of her loved ones. Ainsley is chasing personal gain (career) with a side of (a subconscious?) need to be exposed to murder and her father’s twisted world.

4:05 - This whole interaction between Ainsley and Malcolm is really interesting. Ainsley is knowingly manipulating Malcolm to get the answers she wants. We’ve seen her do it in 2x4 and 1x19. She knows her big brother would do anything for her. It makes sense, they’re five years apart and after the trauma they experienced as children Malcolm felt responsible to protect Ainsley. He never wants to disappoint Ainsley. Not a burden he should’ve had to deal with but I digress. PLUS Malcolm looks weary of Ainsley here. He knows what she’s doing. He’s scared that she’s turning to the dark side. But he still gives her the answers because if he doesn’t - that means something has changed. He thinks that would make Ainsley suspicious and then she might remember what happened to Endicott. He’s scared of and for Ainsley.

4:32 - OKAY. I’ll say it. The thing that annoys me the most about this episode is that it suggests that Ainsley was a debutant when in 1x6 AINSLEY TELLS MARTIN SHE WAS NEVER A DEBUTANT. She went to etiquette school - I guess that doesn’t strictly mean she also did debutant balls but it sort of suggests it in the context of this episode? Did she actually graduate from the etiquette school (there was bullying, maybe she was expelled/dropped out similar to Malcolm and Remington?)?

4:59 - “No stabbies” OMG. How is this show not classified as a comedy?!? Istg I laugh harder watching this ‘drama’ then I do watching most of the shows that call themselves ‘comedies’.

5:35 - It’s honestly kind of amazing that Ainsley and Malcolm are as ‘sane’ as they are. They were raised by a stubborn predatory psychopath and a stubborn rich meddling socialite. They had no chance of normalcy. Look at the amount of pleasure Martin is currently getting by throwing his son under the bus with regards to Jessica.

5:45 - “No actually, I cleaned it up.”.....does this have a dual meaning? Did Martin do something to make Malcolm dispose of the body? We already know that Martin has tried some sort of conditioning on Malcolm (remember ‘C’mon boy!’ from 1x14? The stabbing?). What if Martin said some sort of trigger word to control Malcolm and coerced Malcolm into getting rid of the body? What if this isn’t the first time?

6:05 - Ainsley is a sociopath. I’m calling it again. I called it when I first watched Q&A (1x7) because the way she treated Malcolm was more than just selfish/careless. It was cruel and she didn’t feel any remorse for literally broadcasting her brother’s private health details on television. That is messed up. I honestly won’t be shocked if the writers make Ainsley a full blown serial killers (although I’m not sure I want that because I don’t know how Malcolm would remain the main character if the story goes in that direction?).

6:12 - Poor Jessica. I honestly feel really bad for her. Sure, she’s a headstrong alcohol dependant crazy rich woman. She also has a good heart. She’s been dealt a pretty shitty hand when it comes to relationships (minus Gil but she ruined that because she’s a MORON) and now she’s terrified that her own children have become monsters and she blames herself. She definitely hasn’t been a perfect mother but I don’t think she’s to blame for Ainsley and Malcolm’s obsession with murder. If these kids had a different bio dad, they would probably just have a low-key drug problem or some other common rich kid baggage.

6:15 - “You know that’s not how cancer works right?” LOL. hahahaha

6:33 - Martin kind of has a point. There’s no rehab for murder. That’s why he’s been in jail for 20 years and he still wants to kill people. In my opinion, given what we’ve seen of Ainsley’s personality: as soon as she fully remembers that night - she’s gone. She’ll go full serial killer and Jessica and Malcolm will lose her forever.

6:40 - Jessica’s little jazz hand finger twinkle as she spins on her heel and leaves Martin kills me. It’s so extra. It’s so funny. And it’s sooo Jessica.

6:47 - Damn. Martin is pissed. I’m worried. That’s murder-level rage. If he escapes ISTG Martin is going to try and kill Gil. For so many reasons 1) because he hates Gil, 2) it’ll hurt Jessica, and 3) killing Gil will eliminate his ‘Dad’ competition.

6:54 - Edrisa on caffeine is AMAZING.

7:43 - I love Edrisa but her blatant, unreciprocated crush on Malcolm is honestly getting a little creepy.

7:52 - Gil spent all last season drinking out of a Yankee’s mug. Doesn’t that mean he’s a baseball fan? Why doesn’t he know this pitcher guy?

7:56 - hahahaa “Where is JT?” Because obviously JT is the team sports fan.

8:22 - Does Gil get nightmares about cases? He always seems really uncomfortable around the dead bodies.

8:45 - “And suddenly I’m wide awake” SERIOUSLY - is anyone else laughing every 60 seconds when they watch this show? Is my sense of humour just super dark and messed up?

8:54 - YES. The liquorice is BACK.

9:00 - I love Malcolm talking to JT about his obsession with candy. I love how Malcolm doesn’t even hesitate before giving JT an honest answer. Malcolm is acting like JT’s annoying little brother and I am here for it. One thing I did notice though - Malcolm specifically mentions candy+dopamine but doesn’t mention his depression/anxiety. Processed sugar can be a short-term (unhealthy) way to boost your mood. It’s why some people eat their feelings. I really want more backstory about Malcolm with the lollipops and licorice though.

9:19 - “But you didn’t do anything wrong.” Awwww Malcolm is so soft here. I love how much he genuinely cares about JT. <3 I love how JT is comfortable enough with Malcolm to give him an honest answer. <3 THEIR RELATIONSHIP HAS GONE THROUGH SUCH A GLOW UP. <3

9:32 - “Like toy dolls?” hahaha the way Malcolm perked up here. All I could think was “SQUIRREL!” hahaha.

9:41 - Malcolm is doing better than he has been the past few episodes? I mean he’s still suffering and he’s still in a terrible mental state. BUT he also seems happier? IDK maybe he’s just entered the more manic nervous energy stage of his emotions as opposed to the depressed and scared stage.

9:49 - “Deep childhood trauma”. So we’re looking for a debutant killer with childhood trauma who is chasing perfection? Debutant = rich lady culture. Like Ainsley. AND Ainsley went to the same etiquette school as the first two victims. The writer’s wanted us to assume the killer was Ainsley for the first 15 mins of this episode right? I’m not the only one seeing it?

10:04 - “My sister went there too.” ....why is there something super attractive about the way that line was delivered?

10:08 - I’m so done with this absolute tom foolery. Why does the team keep splitting up into two teams - where one team is JUST MALCOLM. The one who is unarmed and technically a civilian?!? This makes no logical sense to me (except for plot).

10:25 - Was Martin just about to say, “Just like the old days”?!? Is Martin referring to Endicott? OR is Martin referring to something that Malcolm’s repressed from his childhood?

10:30 - “I always root for the bad guys.” .....finally some truth from Martin.

10:40 - Soooooo I guess Mr. David doesn’t know? I promise you Mr. David has suspicions though. How could he not?!?!

11:24 - “It was brutal for Ains.” Look at how sad Malcolm is! Ugh. This hurts so much. He clearly loves his sister so so much and what she’s done is slowly killing him. I honestly think that part of the reason Malcolm helped Ainsley dispose of the body is that Malcolm doesn’t want to loose his sister. His sister is one of the only good things he’s always been able to count on. If word gets around that she’s a killer - Malcolm’s fragile world gets shattered a little more and I don’t know if Malcolm can recover mentally from that.

11:36 - “Teasing made her capable of...stuff.” C’MON. There’s no way Mr. David doesn’t know.

11:45 - Sooo is Martin saying that he recognized that Ainsley was a sociopath when she was a small child? Or did she just respond to his (or John Watkins’) grooming much ‘better’ than Malcolm?

11:56 - “Because she’s her mother’s” Okay. So I see the point. I can see that Ainsley is driven and stubborn like Jessica. BUT it feels like Martin is suggesting that Jessica is capable of murder? Which - I honestly don’t think she is. If anything - Malcolm is more like Jessica than Ainsley is.

11:59 - There was a look in Martin’s eyes when he was comparing Ainsley to Jessica that really freaked me out. I can’t figure out why. It makes me wonder if Martin still somehow views Jessica as ‘his possession’ (he refers to her as his wife all the time but I always assumed that was just to get a rise out of people?). Martin’s dream from 2x4 certainly suggests that he still wants Jessica romantically. I honestly think he’s going to try to escape and rekindle the romance with Jess; and it’s going to go very poorly when Jessica rejects him.

12:06 - Preach JT. Preach. This is creepy af.

13:00 - Ugh. Of course this creep has a history of indecent exposure. Now I understand why Gil and JT were hostile with the dude right from the start.

13:12 - Man. People will use the Bible to justify anything. No wonder people hate Christians ( I say this as a practicing Christian).

13:18 - JT is such a good dude. I’m so glad he’s a dad now. <3 He’s going to be such a good one. <3

13:26 - “One phone call and this place will be shut down.” OH SHIT. GIL THAT IS VICIOUS AND I RESPECT THE SHIT OUT OF IT.

13:35 - I soooo thought that dude was going to sprint out of that room.

14:30 - THIS. YES. This is why I have a problem with Ainsley’s enthusiasm for murder vs. Malcolm’s. Ainsley’s enthusiasm is centred on her nee to ‘get the story’. She’s obsessed with forwarding her career and as a result she’s treating crime like a competitive sport. Malcolm’s obsession (while it can border on creepy and reckless) is always centred on his need to find the killer and stop the murders. Malcolm is seeking justice and his heart is in the right place. I can’t say the same for Ainsley.

14:31 - “We’re brother and sister, everything is a competitive sport”.....whoever wrote this doesn’t have a sibling they experienced trauma with as a kid (and as a result was raised by a single parent). Seriously, my dad was abusive he lived with us until I was 10 and my brother was 7. Then my parents got divorced and my mom was a single parent (he didn’t pay child support or see his kids after the divorce). Are my brother and I competitive? Sure sometimes. But the way we grew up forced us to become partners. Annoyed with Mom? Let’s rant about it together. Is he struggling in math? I’ll tutor him in exchange for a Reese cup. Am I struggling at daycare because I have massive social anxiety? He’ll include me in whatever he’s doing so I’m not sitting alone in a corner. My point: siblings who experience trauma together don’t have the typical sibling relationships that are widely televised in North America. There’s a lot less fighting and competition and a lot more teaming up and commiserating.

14:39 - “It. It’s terrible.” - Notice how Ainsley didn’t actually say how it made her feel? She gave the standard “TV response” to a murder “a terrible/horrific/tragedy has occurred”. She doesn’t feel bad that these women are dead. She’s too consumed with getting a story to even stop and let herself feel anything. I’ve been saying it since last season - the way Ainsley shows no regard for other people and their feelings when she’s obsessed with her job is concerning.

14:50 - “Remind me of the people who cut us off after Dad’s arrest.” ...Are you kidding me?!? The whole fandom has been speculating about this since early season one and they’re not going to elaborate on that line?!? I’m going to need some more information about this and it better be in the upcoming episode where Jessica’s younger sister appears.

15:40 - She thinks of her students as family? Sooo what does she think of Ainsley? Wasn’t Ainsley bullied at this school? Did she do anything about it?

16:00 - this is like a ‘weekend/evening school’ right? Kids aren’t living in this house like a boarding school/summer camp?

16:01 - “Mr. Whitly” UGH. This bitch preaches etiquette and she doesn’t even have the common courtesy to call Malcolm by the name with which he introduced himself? Nah. I don’t like her.

16:13 - Ugh. Ainsley, seriously? Why don’t you help your brother solve the case. AND PREVENT MORE MURDERS. Why are you indirectly but purposely obstructing justice?

16:37 - “Of course.” Huh. Do you think Martin might try and manipulate Ainsley into killing Malcolm? Ainsley definitely capable of it. She doesn’t actually seem to care about Malcolm nearly as much as he cares about her.

17:17 - WTF?!? That’s creepy af. How did no one in this show think this assistant was a suspect? She has a super creepy doll that she ‘forgot’ on the floor the middle of a hallway. AND THE DOLL WAS STANDING UP. Not sitting, not dropped carelessly, STANDING UP.

17:30 - Look at Malcolm’s face. He’s definitely going to be having nightmares about that doll.

18:25 - OMG. This was amazing. JT just totally bulldozed his way into catching that dude. Very badass. Also kind of funny (maybe that’s just my messed up sense of humour again?).

18:44 - Ugh. This dude has a thing for dolls. I don’t want to kink shame but - no. no. There’s something really gross about that.

18:48 - I’ve seen some people say that this doll looks like Ainsley and how that’s supposed to be some sort of foreshadowing/symbolism. I kind of see it? I mean the hair colour is similar and if you pause the screen at 18:48 the angle kind of looks like Ainsley? It would be an interesting metaphor though - Ainsley played with dolls as a little girl. John Watkins gave her angel statues. She is Watkins’ and Martin’s doll’ in the sense that she was the object that murders manipulated/groomed.

18:53 - Then again, pause the screen here and there’s something about the facial structure that looks like Dani to me.

19:00 - Jessica lets Ainsley work in the murder office?!? No. No she doesn’t. This is garbage. Jessica would’ve forbade it. Jessica would’ve bordered up this room immediately after Watkins.

19:57 - Poor Jessica. She’s clearly terrified that she’s losing Ainsley and terrified of Ainsley. BUT Jess, sweetie, running to Europe won’t fix this.

20:16 - “She wanted the dolls to look like her students.” AND PEOPLE SEND THEIR CHILDREN TO HER?!? WTF?!? NO. NO. NO. NOT OKAY.

20:31 - HAHA look at Gil’s face when Trevor tells him he can make the ‘perfect woman’. Gil’s like WTF - can I arrest you for thinking you can fabricate a ‘perfect woman’?!!?

21:06 - Malcolm is having so much fun playing with Trevor’s doll head. Look at how excited he is. It’s kind of adorable but his manic energy is showing which is concerning.

21:10 - Why is Trevor giving his doll fancy 1940s(ish) names?

21:31 - Props to LDP. I honestly believed Gil was annoyed with Malcolm for barging in on the interrogation the first time I watched this.

21:42 - “They got a word for everything.” hahaha OMG. This is so reminiscent of a teenager explaining some new tech to their tech-illiterate parents.

22:00 - I can’t tell if Gil feels sorry for this creep or if he just thinks the dude is really gross. Probably a mixture.

23:00 - Oh we’re bringing up the chloroform again. At least Malcolm knows not listen to Martin about this nonsense.

23:25 - “It doesn’t feel fun.” - THIS. This is why I honestly don’t think Malcolm will ever become a serial killer. His guilt complex is just too big.

23:56 - Are. You. Kidding. Me? This is next level. Ainsley is so out of line here. AND SHE SHOWS NO REMORSE. SHE DOESN’T THINK SHE’S DONE ANYTHING WRONG. THIS GIRL HAS GONE DARK SIDE (she was already halfway there).

24:17 - I’m getting papa!Gil vibes when Gil is talking to Ainsley and I want more scenes of them interacting. Seriously, did Gil have a relationship with Ainsley when she was a kid? I MUST KNOW.

24:45 - Ainsley has no conscience. I honestly don’t think Ainsley has a conscience.

25:00 - “Who is that!?” Malcolm is totally acting like he’s Ainsley’s father-figure right now. I’m here for it.

25:22 - SORE LOSERS?!? I’m sorry. What? If you weren’t concerned about Ainsley you damn well should be now. That is seriously messed up. People are dead. This is not a game. Do you know who else thought murder was a game? Martin Whitly.

25:31 - Okay. Ainsley has a point. Malcolm lecturing anyone about being reckless is pretty hypocritical. But at least Malcolm cares about her.

25:54 - Heart. Shattered. Look at how terrified Jessica is. Look at how gentle and reassuring Gil is. UGh. WHY DID SHE BREAK UP WITH HIM??! I mean, I know why I just think she’s a moron for doing it.

26:00 - Poor Gil. He’s so confused and so concerned. The whole Whitly family is acting crazier then usual and he doesn’t know why.

26:11 - “Both you and Malcolm are at an 11 and I’ve never seen Ainsley like that.” FIND YOURSELF A MAN WHO CARES LIKE GIL AND NEVER LET HIM GO. <3 <3 <3 <3 <3 Seriously. The love and concern he shows for this family warms my cold dead heart.

26:16 - “Her father?!” Oh shit. Now Gil knows there’s something BIG happening. Jessica would never run to Martin unless she absolutely had to.

26:19 - annnnd Gil’s also being a prideful man who’s feeling are hurt. “You went to him?” He’s right to be though - the woman he loves went to a serial killer for advice before going to the guy who practically co-parented with her.

26:33 - “I’m here. Whatever you need. I’m here.” <3 <3 Gil is the definition of a good man. <3 I’m in love with it.

26:48 - “You were right on time for me.” ....*snort* subtle Gil (and in front of JT!!)

27:08 - Edrisa is hysterical on caffeine. hahaha. This whole scene is perfect.

27:20 - You know someone is acting manic when Malcolm Bright is concerned about their eccentric behaviour.

27:34 - Annnnnd Tom Payne was a split second from breaking character here. I don’t blame him. hahaha

28:05 - EDRISA flipping and dropping that pencil. HAHAHAHAHAHA

29:10 - “Absolutely not.” hahaha this is funny but also really sweet. Malcolm knows that Edrisa hopped up on caffeine isn’t safe to have near an active killer. Who knows what’ll happen. I wish he’d care that much about his own well being. Looks like calling for backup last episode was a one time thing.

30:37 - I’ll give the writers one thing - Miss Windsor makes a convincing murder suspect.

31:22 - GIL. STANDING. UP. FOR. JT. IS. EVERYTHING. Where is O’Malley’s back up? Oh yeah, they’re not brave enough to defend him.

32:00 - Huh. Bright texted for backup. This is growth. I’m proud of him.

32:15 - YES. This JT arc was handled right. Sure JT could’ve complained. It would’ve been episodes upon episodes of bureaucratic nightmares and injustice. This show isn’t about racism. They showed enough to portray that the system is broken and they had JT act like a responsible adult. It’s not fair that JT had to go through this or that he’ll likely experience something similar to it again. But the fact that JT is acting like a bigger person is perfect. JT will protect his family. Always. That includes Malcolm. So JT avoids putting through a formal complaint because he knows that will take time away from doing his job, from protecting others, from hanging out with his wife and kid. JT’s taking the higher road, it might not be gratifying or fair but I respect the hell out of him for taking it.

32:28 - Gil is so so proud of JT. Look at him. <3 <3

33:40 - Look, Miss Windsor is a bit of a stuck up bitch but she has a good heart. Look at the way she immediately tells Malcolm where Ainsley is when she realizes what’s happening.

34:14 - This confused me during the first watch - Ainsley obviously didn’t drink any tea - so why is she drugged? (obviously I know now).

34:17 - Big brother Malcolm frantically looking for Ainsley is so so sweet. <3

35:42 - The music, the dolls, and Miss Windsor’s speech here. There’s something about this part of the episode that is strangely reminiscent of 5x16 of Criminal Minds.

36:20 - ......does Miss Windsor have some sort of mental illness? She’s talking to herself and ranting erratically. Is this just emotional stress or something deeper?

37:00 - This is why Malcolm’s not a serial killer. Even now- looking at a killer - he’s trying to sympathize with her. He’s trying to understand why. He’s trying to calm her down, diffuse the threat, and get her mental help.

39:00 - Oh yeah. Ainsley was definitely going to kill without remorse. Again. I’ve seen some theories that Ainsley only ever tries to kill to protect Malcolm. I disagree. I think Ainsley’s trying to protect herself. Ainsley is pissed off that this girl tried to drug her and kill her because she thinks Ainsley is wicked. Ainsley was pissed at Endicott for whatever he did to Ainsley before Malcolm got there. I think Ainsley felt threatened and scared so she reacted. I don’t think this has anything to do with protecting Malcolm.

39:41 - Malcolm isn’t a killer. Look. He smells gas but he takes the time to carry an unconscious murderer (who literally just tried to kill his sister) out of the building.

40:00 - The drama. Holy hell. What a weird ending to this case.

40:48 - Who gave Ainsley a police jacket and let her keep it?

41:14 - She almost died and she’s still obsessing over ‘winning’. This is seriously unstable behaviour. Way more concerning than anything Malcolm’s done since 2x1.

41:45 - “My father was a serial killer also.” Anyone else super irritated by that phrasing?!? Just me?!? Something about the ‘also’ feels super wrong to me.

41:53 - Oh sweetie. I’d argue that you are more messed up than Malcolm.

42:06 - Jessica went to see Martin twice in one episode. THIS IS BAD.

42:15 - “Maybe even more so than Malcolm if that’s possible.” Jessica knows her kids. I’m on her side here.

42:20 - Martin is way too happy about Ainsley showing signs of serial killing.

42:30 - Jessica? You married an act. That man never existed. He’s always been a serial killer. You just didn’t know it. He’s manipulative and you were a victim to it.

42:50 - “A partner.” OH THIS IS NOT GOING TO END WELL. ESPECIALLY FOR THE GIL/JESSICA ARC.

Okay....so definitely the weakest episode of the season so far. AND the fact that we got no mention of Tally and/or the baby this episode is a crime.

BUT I’M SO SO SO EXCITED FOR THE NEXT EPISODE. It’s going to be a televised fanfic and I can’t wait.

#jess-rewatches-prodigal#malcolm bright#prodigal son#gil arroyo#dani powell#JT Tarmel#ainsley whitly#martin whitly#edrisa tanaka#jessica whitly#I LOVE this show#whump#rewatch#spoliers#malcolm needs a hug#ps#so good#2x05#2x5#Bad Manners#s2

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Updated list of the bitches in this system because Gods know we needed it, go!

• Fae- Actual owner of the body. Has not been fully “themself” since they were like 6 (when Harl got here). Always co-cons with someone because they can’t stand being out alone. Doesn’t know or care what we do with their life. Terrified of people. Has left us alone for extended periods of time. If you think you’ve talked to them, there’s a 99% chance it was actually Claire, Amanda, or Becky. Actually a very sweet kid, but very hurt. Will go to the end of the world for their friends. Can hold a grudge like nobody’s business. Paints themself as a bitch but is a softie. Their mom cannot tell the difference between them and Becky. Diabetic, to Nidia’s displeasure. Closet Gryffindor turned Slytherin in order to survive.

• Amanda – Our system’s “guard dog”/Head Bitch in Charge. Much more complicated than that. The real author of Fae’s thigh scars (barely visible now), and maybe the only reason we made it through high school. The little voice that says “kill everyone and blame it on me”. Zero concern for consequences for herself. Impulse control consists of “Jail is awful and Fae doesn’t deserve it”. She’s over 30.

• Lisbeth (Sally)- Just…Sally. The other voice that wants to kill everyone but doesn’t because she actually thinks about the consequences of her actions. Max is technically her partner, but we don’t talk about that (you can ask). I think she’s 30-something, but might as well be Fae’s age.

• Claire- Possibly Fae’s projection of herself into different universes. She can be 6, 17, 24 and 35. Last name Constantine. From Liverpool. Awful accent. Please don’t call her Australian. Another closet Gryffindor turned Slytherin. Most of Fae’s friends are actually hers. Has been Fae for longer than Fae has been Fae. Likes soccer and we’re sorry. Punk. Hella Punk. Also hella broke.

• Mara- Claire’s sister (maybe twin). Approach with caution. (One of the several sexual alters, can be the same ages as Claire) Responsible for most of Fae’s awful dating decisions.

• Valentina- Rarely comes out, but she’s apparently God? We don’t know. Seems like she knows everyone, though. She always looks 20-something, but we know she’s older.

• Nidia- Claire’s daughter and the pure incarnation of Fae’s ADHD. A Jedi. Weirdest kid EVER. Super compassionate. Wears heart on her sleeve. Can be 5, 9, 16 and 21. Impulse control is 100% artificial, but existent. Can, like Amanda, drink up to 3 cans of Monster Energy Drink in a row without batting a lash. Will eat ALL THE CANDY. The reason we need to carry an extra insulin syringe with us most of the time. Pours fun dip and sweetarts into her drinks. The kind of kid child leashes were invented for.

• Hellena- Mara’s daughter. STAY AWAY. Evil incarnate. Abusive A.F. Can and will destroy you. In her 20’s

• Christine- Hell’s identical twin. Remember that girl in Mean Girls who wants to bake a cake out of sunshine and rainbows and smiles? Christine is that cake. Rarely out. Same age as Hell.

• Evey- Hell and Chris’ big sister. That one kid with the pink hair and lots of tattoos. Zero impulse control. Always looks like a teenager for some reason (not over 25)

• Vlad- Agender/Genderqueer mystical creature of the forest. Valentina’s child. Awesome person in general. Permanently 17.

• Harley- Yup. THAT Harley. You know the drill. She’s actually the one who makes all the fun plans because she’s the one who has the energy for it. Gets along with everyone until she doesn’t. Can drink us all under the table. Can drink you under the table. Has been Fae for longer than Claire has been Fae. Was the first one here, so she has tattoo privileges. And dating privileges. And everything privileges, basically. If I say how old she is, I may not live to see another day. Fae’s real mum. Will take you to Petco on exam week to pet puppies. Will yell “doge!” out loud.

Pets every dog. Will steal Teddy from Max.

• Edward- Mr. Nigma, sir. Somehow has better makeup skills than all the girls here combined. If his attitude was as nice as his eyebrows, he’d rule the world by now. EVERYTHING HAS QUESTION MARKS. Knows more than anyone. Is actually a genius. Wastes his time trying to school the little ones (and trying to get Naya to use proper words). Smug bastard. Probs 40-something.

• Cass- Also from comics. EVERYTHING IS YELLOW (yiyo). Doesn’t talk much, but is always fun to have around. Will make you watch animated movies and take you to Starbucks. Will also make you work out. Can be 5, 9, 18 and 25. Smol Cass is a fan of pokemon. If it’s yellow, it belongs to her.

• Naya- Cass’ child. Has her own language, featuring words like “kaijukata”, “pakato”, and “omashii” (“Kaiju attack”, an insult of her own invention, and her word for “mother”.) There are no sidewalks, only pedestrian lanes. Biggest Kaiju Enthusiast. Wants to be Mako Mori.

• M.J.- Has been here for as long as Harley has. Isn’t around as much. The difference between her and Claire is that you can actually understand what MJ says when she gets mad. Probs 25 forever.

• Danni- Amanda’s daughter. Will also fuck you up. Has the weirdest kinks. 23

• Miranda- Danni’s daughter. Don’t ask. Also a sexual alter. 21

• Martha- Miranda’s sister. Level-headed. A psychiatrist. 21. Actually the most mature person in this head, along with Tári.

• Alice- Nidia’s daughter. Also a psychiatrist. Likes psychoanalyzing people. Type 1 bipolar. Thinks all Arkham inmates are humans and wants to help. Will probably end up as an Arkham Inmate herself. Age slides. Toddler Alice is the devil. Can be 5, 9, and 21

• Alyssa- Mara’s best friend. Take Alice out of wonderland and teach her ballet, then add a sprinkle of Luna Lovegood. Permanently 17-ish.

• Robin- Alice’s little sister. Wants to be Carrie Kelly when she grows up. Terrified of squirrels. Can be 5 and 18. Lesbiab. Lesebeb. Girls. Yes.

• Tári- Alice and Robin’s eldest sister. Autistic. Genius extraordinaire. Loves to talk to Eddie. Often one of them leaves the conversation feeling stupid (it isn’t Tári). Loves Legos. REALLY LOVES LEGOS. Forensic Anthropologist/ wants to be Bones when she grows up. Vegetarian. Can be 12/17/21.

• Frances- Harley’s kid. Don’t ask, this was super weird. Frances herself is super weird. She hears voices. The voices tell her to do things. She rarely listens. Actually super polite. Has “opal” hair. 18-20. We don’t really know. If we’re gonna have a sub-system, it will probably be because of Frankie.

• Shilo- Shilo Wallace. Infected by her genetics. Her nightmares are the worst. Once made Amanda and Sally fight over a pair of combat boots just so she could get to keep them. Probably Becky’s best friend in here.

• Bellatrix- That one got here on her own. Over 50. Still looks great.

• Azula- also got here on her own.

• Cassiopeia- Bella’s biggest mistake. Best teacher ever. Resident hipster chick. Is actually here to keep a little group of alters from causing too much mayhem. 28.

• Ascella- Lesbian extraordinaire. Sees dead people. I’m not even kidding. Permanently 23.

• Jamie Moriarty- Another one who got here on her own. Our self confidence boosts and power trips. Will maybe kill someone. Better than you and is not afraid to let you know. Fae’s teachers were terrified of her.

Everyone’s terrified of her; I don’t know who we think we’re kidding. 32.

• Lestat- Fae’s gay vampire boyfriend. Is rarely around anymore. Probably for the best. 260-ish years old. Prick.

• Lindsay - THE definitive Sexual alter. From a comic book oneshot. Amanda on steroids, but if Amanda knew how to socialize. Loves horror, movies, photography and monsters. 26.

• Becky - Called “morbid” for a reason. Disabled as all fuck. Autistic/ADHD, connective tissue disorder. A lawyer. Loves to argue. Jon Crane’s wife (at least here). 30ish. Always cold and always in pain. If we cancel plans, it’s most likely her fault and she’s sorry.

• Liliana - Necromancer. Big Titty Goth GF. We love and cherish her, alcoholism and all. Will never be over Jace and she knows it.

• Chandra - Pyromancer extraordinaire with severe ADHD. A lot like Fae in a lot of ways. Decidedly Pansexual, thank you very much. 25.

• Vraska - Ravnican to the core, but also a fantastic pirate. Great leader, good friend, fun to be around. Has the huskiest voice in the system. Has the worst flashbacks out of all of us. Can be 19 and 29.

• Kari - Vraska and Jace’s kid. Hypermelanistic gorgon, telepath like her dad. Fun to be around. Can be 7, 12 and 25.

• Ral - Very very Izzet, and very very gay, and we love him for it. Very intelligent, good at fixing and making things with his hands. Confident, charismatic, and a workaholic. Tomik’s husband. Sometimes with Max. In his 40’s

• Tomik - Ral’s husband. Quiet, but very caring and polite.Also very smart and hard-working, always loves to learn new things and meet new people. 27-ish. Very gay, too. Makeup skills up there with Eddie’s.

• Teysa - Tomik’s boss. A Boss Ass Rich Bitch, and we love her lots for it. Very polite and interesting to be around. Could buy us all and our families ten times. Old, but looks to be in her early 30’s.

• Avacyn - An angel from Innistrad. Here to protect us. Really likes listening to old pop-punk and emo music with Max. Very sweet to be around, although she can be a little literal-minded.

• Olivia - A Vampire and a bitch. Liliana’s...ex? Something. A lot like Teysa, but much more fun-loving and impulsive.

• Nahiri - Doesn’t come out much. Stern but caring, very savvy, doesn’t take anyone’s crap. Can hold on to grudges like her life depends on it.

#alterblogging#I'm probably missing people but oh well#here's the main ones#yes there's a lot of MTG peeps here#they're recent#we love them

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Morris Hoffman, Therapeutic Jurisprudence, Neo-Rehabilitationism, and Judicial Collectivism: The Least Dangerous Branch Becomes The Most Dangerous, 29 Fordham Urb L J 2063 (2002)

Introduction

The movement that calls itself "therapeutic jurisprudence"' is both ineffective and dangerous, in almost the same way that its predecessor—the rehabilitative movement that became popular in the 1930s and was abandoned in the 1970s—was both ineffective and dangerous. Drug use, shoplifting, and graffiti are no more treatable today than juvenile delinquency was treatable in the 1930s. The renewed fiction that complex human behaviors can be dealt with as if they are simple diseases gives the judicial branch the same kind of unchecked and ineffective powers that led to the abandonment of the rehabilitative ideal in the 1970s. In fact, this new strain of rehabilitationism has produced a judiciary more intrusive, more institutionally insensitive and therefore more dangerous than the critics of the rehabilitative ideal could ever have imagined.

I. The Real Face of Therapeutic Jurisprudence

In a drug court in Washington, D.C., the judge roams around the courtroom like a daytime TV talk show host, complete with microphone in hand.' Her drug treatment methods include showing movies to the predominantly African-American defendants, including a movie called White Man's Birth.3 She often begins her drug court sessions by talking to the "clients"4 about the movies, and then focusing the discussion on topics like "racism, justice, and equality."5 The judge explains her cinemagraphic approach to jurisprudence this way:

Obviously they need to talk about their own problems and what leads to them, but I also think that it's good to have distractions in life. I've found out that if there are periods of your life when you are unhappy, sometimes going out to see an interesting movie or going out with a friend and talking about something else, or going to the gym to work out, these kinds of things can help you through a bad day.6

After the film discussion, the session begins in earnest. Defendants who are not doing well are scolded and sometimes told stories, often apocryphal, about the fates that have befallen other uncooperative defendants or the drug court judge's own friends and family members.7 Some defendants are jailed for short periods of time and/or regressed to stricter treatment regimens, and eventually some are sentenced to prison.8 The audience applauds defendants who are doing well, and the judge hands out mugs and pens to the compliant. The judge regularly gives motivational speeches that are part mantra and part pep rally. Here is a typical example:

Judge: Where is Mr. Stevens? Mr. Stevens is moving right along too. Right?

Stevens: Yep.

Judge: How come? How come it is going so great?

Stevens: I made a choice.

Judge: You made a choice. Why did you do that? Why did you make that choice? What helped you to make up your mind to do it?

Stevens: There had to be a better way than the way I was doing it.

Judge: What was wrong with the way you were living? What didn't you like about it?

Stevens: It was wild.

Judge: It was wild, like too dangerous? Is that what you mean by wild?

Stevens: Dangerous.

Judge: Too dangerous, for you personally, like a bad roller coaster ride. So, what do you think? Is this new life boring?

Stevens: No, not at all.

Judge: Not at all. What do you like about the new life? Stevens: I like it better than the old.

Judge: Even though the old one was wild, the wild was kind of not a good wild. You like this way.

Stevens: I love it.

Judge: You love it. Well, we're glad that you love it. We're very proud of you. In addition to your certificate, you're getting a pen which says, "I made it to level four, almost out the door."9

This is the real face of therapeutic jurisprudence. It is not a caricature. Except for the movie reviews, this Washington, D.C. drug court is typical of the manner in which this particular kind of therapeutic court is operating all over the country. Defendants are "clients"; judges are a bizarre amalgam of untrained psychiatrists, parental figures, storytellers, and confessors; sentencing decisions are made off-the-record by a therapeutic team10 or by "community leaders";11 and court proceedings are unabashed theater.12 Successful defendants-that is, defendants who demonstrate that they can navigate the re-education process and speak the therapeutic language13—are "graduated" from the system in festive ceremonies that typically include graduation cake, balloons, the distribution of mementos like pens, mugs, or T-shirts, parting speeches by the graduates and the judge, and often the piece de resistance—a big hug from the judge.14

Drug courts are the most visible, but by no means the only, judicial expression of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement. The idea that judges should be in the business of treating the psyches of the people who appear before them is taking hold not only in drug courts but in a host of other criminal and even civil settings. Some therapeutic jurists see bad parenting, domestic violence, petty theft, and prostitution as curable diseases, akin to drug addiction, and argue that divorcing parents, wife-beaters, thieves, and prostitutes should therefore be handled in specialized treatment-based courts.15 The objects of the treatment efforts include not only the litigants in civil cases, and the criminals and victims in criminal cases, but also the "community" that is "injured" by the miscreant. Petty criminals in many so-called "community-based courts" are in effect sentenced by panels of community members, typically to perform various community services as deemed necessary by the panels, in order to "heal" the damage done to the "community.”16

It is curious that the existing scope of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement, with the exception of drug offenses, is limited to relatively minor petty and misdemeanor criminal offenses.17 We might ask ourselves why the movement ignores the entire spectrum of violent felonies, so many of which have an apparent psychiatric component. We don't have specialized child molester courts in which "clients" are hugged and pampered and cajoled into right-thinking. Why not? My suspicion, as discussed in more detail below,18 is that what much of therapeutic jurisprudence is really about, at least in the criminal arena, is a de facto decriminalization of certain minor offenses which the mavens of the movement do not think should be punished, but which our Puritan ethos commands cannot be ignored. Supporters of the movement recognize that as a political matter they cannot go too far blurring the distinction between acts and excuses.19

True to their New Age pedigree, therapeutic courts are remarkably anti-intellectual and often proudly so. For example, the drug court variant is grounded on a wholly uncritical acceptance of the disease model of addiction, a model that is extremely controversial in the medical, psychiatric, and biological communities.20 All of the therapeutic jurisprudence variants presume that the underlying problem in virtually all kinds of cases—drug abuse, domestic violence, delinquency, dependency, divorce, petty crimes—is low self esteem, despite the fact that many psychological studies have shown that violent criminals tend to have high self esteem.21

The question asked in these new therapeutic courts is not whether the state has proved that a crime has been committed, or whether the social contract has otherwise been breached in a fashion that requires state intervention, but rather how the state can heal the psyches of criminals, victims, families, dysfunctional civil litigants, and the community. The goal is state-sponsored treatment, not adjudication, and the adjudicative process is often seen as an unnecessary and disruptive impediment to treatment.22 Because the very object is treatment, rehabilitated criminals deserve no punishment beyond what is necessary to restore them, their victims, and the community to their prior state.23

The therapeutic jurisprudence movement is not only anti-intellectual, it is wholly ineffective. The treatment is a strange combination of Freud, Alcoholics Anonymous, and Amway, whose apparent object is not really to change behaviors so much as to change feelings.24 Drug courts are a perfect example. The success of drug-court treatment programs is measured more by a defendant's professed attitude adjustment than by the sort of concrete measures one might expect of such programs, such as whether the defendant stops using drugs. As long as defendants are compliant with treatment ("buying into the program," as addiction counselors say), they are moved from treatment phase to treatment phase, often irrespective of whether the treatment is actually working. As James Nolan puts it, drug court success "is evaluated in large mea- sure by whether or not clients adopt a particular perspective.25

The particular perspective required is the disease model of addiction. Compliance is almost always measured by a defendant's willingness to admit that his or her drug use is a disease. Any resistance to the disease model is reported as "denial," a crime apparently much worse than continued drug use.26

The therapeutic jurisprudence literature is almost completely devoid of any empirical discussion of whether litigants, defendants, and victims, let alone "communities," are actually being helped by all this perspective-changing treatment, and understandably so. The imprecise words common to the therapeutic language—words like "healed," "restored," and "cured"—are simply incapable of being subjected to rigorous testing.

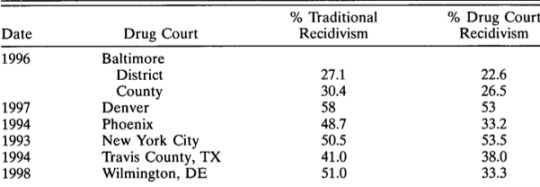

When investigators have looked at less imprecise measures of success-like recidivism rates-the therapeutic promise has proved wholly ineffective.27 For example, the very first effectiveness study performed on the very first modern drug court—in Dade County, Florida—showed that drug defendants treated in the drug court and drug defendants processed in the traditional courts suffered statistically identical rearrest rates.28 Virtually every serious study of drug court effectiveness has reached similarly sobering results,29 leading the General Accounting Office to declare in 1997 that there is simply no firm evidence that drug courts are effective in reducing either recidivism or relapse.30

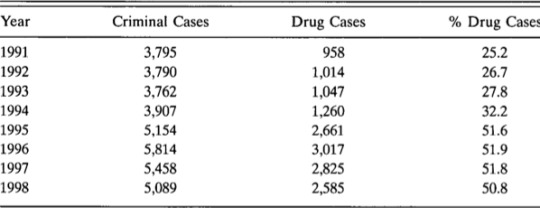

Drug courts not only do not reduce recidivism or relapse, they have the unintended consequence of dramatically increasing the number of drug defendants sent to prison. The reason is massive net-widening, that is, the phenomenon whereby new programs targeted for a limited population end up serving much wider populations and thereby losing their effectiveness. In Denver, Colorado, for example, the number of drug cases nearly tripled two years after the implementation of its drug court.31 That fact, coupled with typically dismal recidivism rates, led to the entirely predictable result that Denver judges sent more than twice the number of drug defendants to prison in 1997, two years after the implementation of the drug court, than they did in 1993, the last year before the implementation of the drug court.32

If therapeutic jurisprudence were just a trendy idea that did not work, we could let it die a natural death. But it is not just trendy and ineffective, it is profoundly dangerous. Its very axioms depend on the rejection of fundamental constitutional principles that have protected us for 200 years. Those constitutional principles, based on our founders' profound mistrust of government, and including the commands that judges must be fiercely independent, and that the three branches of government remain scrupulously separate, are being jettisoned for what we are led to believe is an entirely new approach to punishment. In fact, this new approach-state mandated treatment-turns out to be a strangely out-of-touch return to rehabilitative ideals that gained popularity in the 1930s, but were abandoned in the 1970s because they not only did not work but, in the bargain, armed the state with therapeutic powers inimical to a free society.

There are four main reasons why the new therapeutic judges are most dangerous: 1) they are amateur therapists but have the powers of real judges; 2) they act in concert with each other, their communities, prosecutors, defense lawyers, and the self-interested therapeutic cottage industry, contrary to the fundamental principle of judicial independence; 3) they impinge on the executive branch's prosecutorial and correctional functions; and 4) they impinge on the legislative function by making drug policy.

Before I address these four dangers, let me briefly review the history of punishment and the scant theoretical underpinnings of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement in the context of this history.

II. A Brief History of Punishment

The idea of punishment as moral retribution may have its roots in what some anthropologists have called "defilement," the process by which primitive societies interpreted and explained human suffering as punishment by the gods.33 Such an explanation for otherwise inexplicable suffering can be deeply comforting. It means that our suffering is not meaningless and, more practically, that if we abide by the laws of the gods we will be protected from their wrath.34

As humans began to imitate the laws of gods with the laws of men, we also imitated defilement. Punishment became one of the methods by which we not only enforced our common codes of conduct but also comforted one another with the idea that no one would have to endure man-inflicted suffering so long as the codes of conduct were honored. Indeed, in its most profound sense, the rule of law necessarily requires the tyranny of gods over man, or of the many over the few, and that tyranny in turn requires some form of theocratic or group disapproval when norms are violated.

Interestingly, imprisonment as a form of punishment is a relatively recent invention, in contrast to custodial detention pending trial. In the ancient world, most crimes were punished either by banishment, various forms of corporal punishment such as beating or mutilation, or, most often, death.36 Imprisonment was reserved as punishment only for disobedient slaves, whose execution was uneconomic; political criminals, whose execution risked martyrdom; and petty criminals, whose execution was unwarranted.37 Even as late as the 1780s, in a society as fully touched by the Enlightenment as England, death was the sanction for virtually every crime, including crimes that we would today deem misdemeanors.38

There were many precursors to the modern prison: jails for pretrial detention and short sentences; workhouses for debtors; almshouses for the poor; reformatories for minors; convict ships for banishment; and the gallows for most other crimes.39

In fact, the prison-that is, a jail for serving long sentences after conviction—is a uniquely American invention. Prisons were first used by Pennsylvania Quakers in the late 1700s, primarily as a humane alternative to corporal punishment and execution.40 The first prison was Philadelphia's Walnut Street Jail, which the Quakers opened in 1790 as a "penitentiary" for criminals convicted in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.41 The Quaker notion of a penitentiary was the product of the fortuitous confluence of the Quakers' theological beliefs and their knowledge of Cesare Beccaria's retributionist monograph On Crimes and Punishment.42 The Quakers hoped that long periods of isolation, which provided an opportunity for reflection and solitary Bible study, would ultimately lead to repentance.43 New York adopted this system in 1796, and prisons soon flourished across America and Europe.44

The modern debate about punishment revolves around the primacy of four components: retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, and rehabilitation.45 In the late 1700s-precisely at the time when the Quakers were experimenting with prisons and, more importantly, when our founders were debating our form of government—the German philosopher Immanuel Kant constructed a philosophy of retribution, giving a rational foundation to what had been the retributional basis of all punishment since the dawn of civilization.46 He argued that the preeminent goal of criminal law must be retribution, and that punishment should be an end in itself.47 Kant's view was that to punish the criminal defendant as a means to any other utilitarian goal-deterrence or rehabilitation, for example—was to de-humanize him by reducing him to an object.48 Moreover, Kant viewed punishment as a purely retributive reaction to the crime itself, therefore, the punishment had to be proportionate to the crime.49

Georg Hegel concurred with Kant's retributionist ideal, adding the notion that punishment annulled the crime.50 In Hegel's construct, crime is the negation of moral law, and punishment is necessary to negate that negation to restore the moral right.51 Hegel continued the Kantian view that criminals themselves are moral beings, entitled to have their crimes negated by proportionate punishment. As Hegel stated:

[P]unishment is regarded as containing the criminal's right and hence by being punished he is honoured as a rational being. He does not receive this due of honour unless the concept and measure of his punishment are derived from his own act. Still less does he receive it if he is treated either as a harmful animal who has to be made harmless, or with a view to deterring and reforming him.52

Cesare Beccaria is generally credited with the first systematic exposition of proportionality.53 His version, much heralded in Western Europe and the American colonies, took a decidedly political view. Beccaria believed that requiring criminal sentences to be proportionate to the crime was an important limitation on the powers of government.54

Thus, retribution not only survived the Enlightenment, it achieved an important philosophical structure, both in its own right and as the basis for proportionality. It continued to flourish in both Europe and America and was consistent with the spread of the Quaker penitentiaries. People were sentenced to penitentiaries to be punished; there was nothing "rehabilitative" about them, except the repentance that was expected to come from enduring the punishment.

The retributionist paradigm lasted thousands of years and did not come under serious philosophical attack until the early 1800s, when a group of English utilitarians led by Jeremy Bentham began to challenge it.55 For the utilitarians, the only purpose of punishment was to prevent crime, that is, to be a deterrent.56 Bentham, and in America, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., saw the prospective criminal as a rational bad man, who weighed the benefits of his crime against the risks of detection and the costs of punishment.57 The purpose of punishment under the deterrence model was simply to make the costs of crime so high that they outweighed the benefits.58

The utilitarians believed that morality has nothing to with punishment. Bentham argued that if he could be assured that a particular criminal would never commit another crime, any punishment of him would be unjust.59 Richard Posner has argued that aside from the problem of judgment-proof criminals, all criminal sanctions could be replaced with a system of fines.60

Naturally, if punishment is viewed as a utilitarian tool to deter future illegal behavior of potential criminals, then it can also be used, though less efficiently, to shape the behavior of the particular defendant being punished. Not only would punishment deter him from engaging in future crimes, but it could also change him. The early beginnings of what became known as the "rehabilitative ideal" thus started, on their face, as a rather simple extension of the deterrence model.

But it was hardly a simple extension. It represented a profound change in the way human behavior was viewed. Criminals were no longer ordinary people, cursed like all of us with original sin, whose own humanity demanded that their crimes against moral consensus be purged with proportionate punishment.61 Rather, they were morally diseased, quite different from us, and they needed to be cured.

By the end of World War I, this rehabilitative perspective was becoming dominant in American penology, and it remained dominant until after World War II. It is probably no coincidence that the rise and fall of the rehabilitative ideal coincided roughly with the rise and fall of the welfare state.62 Among the state's increasing New Deal responsibilities toward its citizens was the responsibility to cure all the social ills that were believed to lead to crime, and to treat criminals whose as-yet unreformed social circumstances led them to crime. There was a distinct moral fervor in the early rehabilitationists, as there is in its current devotees, similar to the tenor of the temperance movement: There is a right way and a wrong way to live, and lost souls who choose the path of crime, whether as a result of social circumstance or not, must be shown the right way.

The attacks on the rehabilitative ideal came primarily from the political left, beginning with the jewel of the rehabilitative ideal—the American juvenile court system. With its progressive origins in Chicago in 1899, the juvenile court movement was based on the belief that young offenders were not only ripe for rehabilitation, and needed a more individualized and sensitive justice system in order to maximize rehabilitative efforts, but also that, unlike adult criminals, they suffered from the curable sociological disease of "delinquency.”63 The function of juvenile courts was not to punish or to deter, but to cure delinquency. The juvenile court movement took the nation by storm, not at all unlike today's drug court movement.64 By 1920—just twenty years after their invention—juvenile courts were in place in all but three states.

But the sensitive paternalism of the juvenile court movement had an ugly statist face. Commentators began to write about a system in which gentle persuasion was giving way to unchecked judicial powers, and where an abject lack of basic due process "helped to create a system that subjected more and more juveniles to arbitrary and degrading punishments.66 Even the Supreme Court entered the fray, ruling in 1967 that juvenile defendants are entitled to the protections of the Sixth Amendment's guaranty of counsel.67

Critics of both the juvenile and adult rehabilitative ideal also began to express concerns about a governmental regime in which defendants are simultaneously treated and punished. In 1971, the American Friends Service Committee published a scathing attack on rehabilitative penology, and included in their criticisms a fundamental objection to coerced treatment: "When we punish the person and simultaneously try to treat him, we hurt the individual more profoundly and more permanently than if we merely imprison him for a specific length of time."68 The Quakers' recantation of the rehabilitative ideal was particularly influential, given their seminal role in the invention of the American penitentiary.

By 1970, forty years after its ascension, the rehabilitative ideal was in theoretical and empirical shambles.69 Uncoupled to any concept of proportionality, its primary theoretical failure was that it gave the state unchecked powers to "cure" that were unrelated to any notions of criminal responsibility and fundamental justice. If it takes ten years of prison, or any other form of state-imposed therapy or re-education, to cure Jean Valjean of shoplifting, then ten years is what must be imposed. This threat to individual liberty, acceptable to pro-government progressives of the 1930s, was decidedly unacceptable to a post-World War II, post-Nazi, cold war generation becoming increasingly wary of state power. As Norval Morris put it: "[T]he concept of just desert remains an essential link between crime and punishment. Punishment in excess of what is seen by that society at that time as a deserved punishment is tyranny.”70 He further stated: "We cage criminals for what they have done; it is an injustice to cage them also for what they are in order to change them, to attempt to cure them coercively."71

The real death knell to the rehabilitative ideal, both in general and in its juvenile incarnation, came not from the theoreticians but from the empiricists. Rehabilitation simply did not work. Crime was mysteriously immune to the entire liberal regimen, from anti-poverty programs to prison reform.72 After four decades of experimentation, the studies rather dramatically illustrated that all of our idealistic efforts to rehabilitate had virtually no effect on the propensity of juveniles or adults to commit crime.73

The fiction that imprisonment, even in its most rehabilitation- friendly form, has ever been successful in rehabilitating inmates has come to be called "the noble lie" by some critics.74 David Rothman, who coined the term, argued in 1973 that it was long past time to abandon the noble lie:

The most serious problem is that the concept of rehabilitation simply legitimates too much. The dangerous uses to which it can be put are already apparent in several court opinions, particularly those in which the judiciary has approved of indeterminate sentences . . . . Moreover, it is the rehabilitation concept that provides a backdrop for the unusual problems we are about to confront on the issues of chemotherapy and psychosurgery .... This is not the right time to expand the sanctioning power of rehabilitation.75

With a swiftness rarely seen in complex institutions, the American penal system dropped rehabilitation almost overnight. What had, as late as 1972, been described in the criminal law treatises as the central justification for punishment,76 was by 1986, being described in the past tense.77 This was much more than a theoretical rejection by academics and textbook writers. Correctional officials across America were also abandoning rehabilitation in their day-to-day operations.78

The extraordinarily sudden abandonment of the rehabilitative ideal gave way to a kind of fusion of retribution and incapacitation, dubbed by some as "neo-retributionism.”79 The modest goals of punishment as a just dessert, and prevention as the simple act of taking criminals out of society, replaced rehabilitation as the dominant penal theory.80 These ideas ultimately resulted in the abandonment of indeterminate sentencing schemes and eventually to the controversial Federal Sentencing Guidelines.81

Almost all modern criminologists acknowledge that each of the four traditional justifications for punishment—retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation—must continue to play some role in the criminal justice system.82 However, integrating them into a coherent and sensible system has not been easy, in no small part because they represent incompatible goals.83 If deterrence and incapacitation were the only considerations, then perhaps all crimes should be punishable by life sentences or death.84 If rehabilitation were the only consideration, then all crime could be considered forms of social disease, treatable in hospital-like settings, never in prisons.

Only retribution connects the crime with the punishment, treats criminals as moral beings rather than diseased subjects in a utilitarian social experiment, and imposes proportionality limitations on the government's right to punish. As a result, despite all their machinations about a synthesis, most modern criminologists have found their way back to retribution as the pole star of punishment.85

In 1979, Francis Allen delivered the Storrs Lecture at Yale Law School on the topic of the demise of the rehabilitative ideal. That lecture was published in 1981, and it has become a kind of obituary for rehabilitation.86 Allen impressively documented both the theoretical and empirical failings of rehabilitation. He concluded his lectures with this prediction:

[A]ttitudes toward [the rehabilitative ideal] are likely to be wary in the closing years of this century. A statement made by Lionel Trilling over a generation ago still possesses acute relevance to the present: "Some paradox of our nature leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the object of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then our wisdom, ultimately our coercion. ... " Given the history through which American society has recently passed, it is hardly possible that the total benevolence of governmental interventions into persons' lives will be unthinkingly assumed .... It is just as well. For modern citizens of the world have learned that the interests of individuals and society are frequently adverse and that the assumption of their identity supplies the predicate for despotism.87

Sadly, Professor Allen's prediction could not have been more wrong. Less than ten years after rehabilitation's obituary, the gurus of rehabilitation were back, this time with a vengeance, fueled by a zeal to treat the psychiatrically less fortunate, and in particular to win the war on drugs. These neo-rehabilitationists are pushing judges into unprecedented extremes that Professor Allen could not have imagined. In the flash of an eye judges have become intrusive, coercive, and unqualified state psychiatrists and behavioral policemen, charged with curing all manner of social and quasi-social diseases, from truancy to domestic violence to drug use. By forgetting the most profound lesson of the twentieth century—that the state can be a dangerous repository of collective evil—therapeutic jurisprudence poses a serious risk to the kind of individualism and libertarianism upon which our republic was founded.

III. The Theory Behind Therapeutic Jurisprudence

Although therapeutic jurisprudence descends directly from the long-rejected rehabilitative ideal, its proponents rarely talk about its theoretical heritage. The movement is almost devoid of anything resembling serious theoretical self-examination. The questions that have plagued philosophers and criminologists for a thousand years, and whose answers have come to define all major schools of criminology, are questions therapeutic jurisprudence devotees seldom ask.88 But the movement does have a short history, if not a terribly satisfying theoretical one.

It owes its beginnings to mental health law, where, by definition, the current and prospective mental states of the participants are the primary inquiry. Its initial insights were neither terribly profound nor particularly original: in a system whose very function is to judge the mental state of its subjects, we should think about the mental health effects of the actions we as judges take. Thus, for example, when we remand a criminal defendant for a competency evaluation, we should think about the effects the remand and evaluation might have on the defendant's competence.

These initial formulations about a therapeutic judicial perspective were limited in several important respects. First, they were focused on empirical questions: what effects are our rulings having on the mental health of the chronically mentally ill, insane or in- competent? Proponents, at least initially, never suggested that we should begin to change our rulings or the way we make them in anticipation of effects before we measure what those effects might actually be.

More importantly, these therapeutic ideas were originally proposed exclusively for application to mental health law, where the state has already crossed that thorny boundary of paternalism and already has its hands uncomfortably inside the heads of the unfortunate participants. Of course, many aspects of mental health law involve the judiciary's positive obligation to ensure treatment of the mental conditions of the people appearing in court as a precondition to moving into its more traditional truth-finding role. By expanding the therapeutic model into nonmental health areas, the therapeutic jurisprudence movement not only intrudes without any basis for intrusion, it profoundly changes the judicial function. Trials are no longer processes to investigate factual guilt and discover truth, they are mere opportunities to treat.

This therapeutic perspective is completely inimical to the judicial function. We should conduct trials guided by the rules of procedure and evidence that have been crafted over centuries to maximize the reliability of the result, not to ensure that the litigants have a meaningful mental health experience. We should impose sentences and assess damages guided by well-settled principles of responsibility, not by fretting about whose feelings will be hurt or how the community can be healed.

The profound and dangerous expansion of the judicial role represented by the therapeutic jurisprudence movement is just a small part of a broad therapeutic trend in all aspects of government and indeed across the entire spectrum of our culture. James Nolan has labeled this trend "the therapeutic ethos."89 Government's new role is to treat, not to enforce norms. Its success is measured by how it makes us feel, not by what it actually does. And because the couch of State needs patients, citizens are no longer individual participants in a free republic, but sets of victims with complicated diseases in dire need of state-sponsored treatment.

In this "postmodern moral order," as Nolan calls it, suffering is no longer viewed as a part of the human condition, but rather as the inevitable consequence of some disease or injury. Almost all of human behavior has become pathologized. We speak of "addictions" to all manner of behaviors that we would have called "choices" just thirty years ago.90 Today, cancer and alcoholism are both "diseases"; heroin use now shares an addictive moral equivalence with things like gambling and eating chocolate. Of course, this externalization of behavior is just a new version of our old friend defilement: once we blamed phantom gods for our suffering;91 now we blame phantom diseases.92

In the particular context of drug courts, James Nolan has called this process of pathologization the "eradication of guilt":

The drug court's eradication of guilt has been a subtle and insidious process. Guilt is not so much challenged as ignored. It is not so much disputed as it is made irrelevant. But it is the making irrelevant of something that has long been regarded as the crux of criminal justice.... The jettisoning of guilt may well represent the most important, albeit rarely reflected upon, consequence of the drug court. If, as Philip Rieff argued, culture is not possible without guilt, one wonders what will become of a criminal justice system bereft of what was once its defining quality.93

Blaming the pathogens has become the raison d'etre for the judicial system, both in criminal and civil cases. An African man who murders his wife blames his anti-divorce culture;94 a fired employee blames "chronic lateness syndrome."95 Of course, the judiciary takes its cases as it finds them, and judges cannot be blamed entirely for acting like psychiatrists when the parties insist on it. But the therapeutic jurisprudence movement requires us to act like psychiatrists even when no litigant is insisting on it, and indeed even when all the litigants object (that is, they are in "denial"). It is this aspect of mandated judicial intrusion that makes therapeutic jurisprudence so dangerous and so utterly unacceptable in our constitutional scheme.

IV. The Most Dangerous Branch

The judicial branch was specifically designed to be the least dangerous of the three branches. Hamilton coined that famous phrase in this classic description of the circumscribed powers of the federal judiciary:

[T]he judiciary, from the nature of its functions, will always be the least dangerous to the political rights of the Constitution; because it will be least in a capacity to annoy or injure them.... The judiciary ...has no influence over either the sword or the purse; no direction either of the strength or wealth of the society; and can take no active resolution whatever. It may truly be said to have neither FORCE NOR WILL, but merely judgment; and must ultimately depend upon the aid of the executive arm even for the efficacy of its judgments.96

Federal judges are not elected, but appointed for life, helping to decrease the chances they will be influenced either by corrupt forces or, often more subtly, the vagaries of popular will.97 The case or controversy requirement helps decrease the chances that judges will make abstract law (that is, policy) in the guise of deciding a case.98 The very architecture of the federal and state systems leaves the judicial branches without the power either to make or enforce laws and further dissipates federal judicial power by imbedding it in a system in which individual states continue to operate in their own spheres of sovereignty.

One might ask why the founders were so keen on such a comprehensive institutional clipping of the judiciary's powers. The answer is that they appreciated, from their own English history, that unchecked judicial power is an evil to avoid at almost any cost. Both the Federalists and the anti-Federalists were acutely aware of the failings of the English system, in which all judges were appointed by the Crown and served at the Crown's pleasure, and in which Parliament was invested with supreme appellate jurisdiction in all cases.99

The founders were even more acutely aware of the failings of the Confederation, under which there was no federal judiciary at all.100 Hamilton wrote extensively about the need for an independent judiciary to house judges capable of defending the new federal Constitution against incursions by the other two branches.101 Madison's expositions on the separation of powers doctrine were designed to allay the fears of the anti-Federalists that the existing constitutional plan did not do enough to separate the three branches.102

Our commitment to judicial restraint is not limited to the constitutional design. The mootness103 and ripeness104 doctrines give meaning to the case or controversy requirement, and help insure that decisions by judges will be a recourse of last resort. Indeed, the whole paradigm of the common law is built around the notion that precisely because judges have extraordinary powers in single cases—the power to incarcerate and the power to bankrupt—those powers must be limited to single cases and will operate beyond single cases only after surviving the judgment of judicial history.105

Along with these structural limitations, judges have developed a powerful ethos of restraint. Although some might say the ring of that ethos has become rather hollow in the years following the New Deal and Warren Courts, the restraining rules have for the most part remained quite vigorous, especially in trial courts. Deference to appellate court precedent effectively constrains even the most independent-minded trial judge, as it does the appellate courts themselves, though of course to a lesser degree. At all levels, we are loath to decide issues we need not decide, are generally committed to deciding cases on the narrowest grounds, and will almost always follow controlling precedent.

All of these constitutional, common law, and normative principles have blended together to create a profound commitment to restraint in responsible judges. We are unrepresentative, mostly unelected, independent magistrates whose function is to decide no more than the necessary issues in the single cases thrust upon us, in accordance with laws and established rules of evidence and procedure with which we may or may not agree. Juries tell us the facts, appellate courts may tell us we were wrong on the law, and legislatures may avoid most effects of our decisions by changing the laws. We have no more valid insight into public policy than the members of any other particular occupation.106

Yet it seems to be an occupational hazard for judges and other members of the public to confuse our simple role as gatekeepers of the truth-finding function with anything at all having to do with the will of the governed. We do not make public policy; we do not even enforce it. We are, as Madison put it, only the "remote choice of the people.”107 That very remoteness is what both prevents us from becoming, and tempts us to become, the most dangerous of the three branches.