#edward mendelson

Photo

—Edward Mendelson, “Life, Death, This Moment of June”

Mendelson reviews two new post-copywright Mrs. Dalloway editions—the Norton Critical (ed. Anne Fernald) and the Liveright “Annotated” (ed. Merve Emre), neither of which I’ve seen yet. Though sometimes I don’t want vast scaffolds of editorial apparatus if a book can be read, more or less, without them. Mendelson lucidly observes the reductionisms of too-much-information or not-the-right-information or why-is-this-relevant-information such volumes tend to imply. Historical context? What is it but everything that’s ever happened, what George Eliot labeled “that tempting range of relevancies called the universe”? I’ve never seen a photo of the woman Woolf based Clarissa on; I’m not sure how it would help me to read the novel if I had, though Emre includes one in her edition.

At the heart of the review, part of which I screenshotted above, Mendelson objects to Emre’s heavy editorial hand. She conflates, in the novel’s most crucial scene, the American and British texts, though the latter, finalized later, is more somber and weighty. I agree with his critique of Emre’s editorial practice, though she must have justified it to herself by saying that Shakespeare’s editors do this kind of thing all the time, so why not Woolf’s editors? Most cheap paperback editions of Hamlet, for example, run the Second Quarto and the Folio texts together on the principle “the more Shakespeare, the better,” even though this conflation creates inconsistencies in plot and characterization.

I do not agree with his critical judgment on Woolf. “He made her feel the beauty, made her feel the fun” is more complex, truer to life, scandalously accurate, whether the moralist finds it trivial or no. She lost her nerve when she took that line out for the British version. I concluded the essay I wrote on Mrs. Dalloway for my website in 2018—not to be confused with my 2013 dissertation chapter on the novel—with reference to teaching this particular sentence:

This passage never goes well in the classroom—in a social setting, neither I nor the students can get past condemning Clarissa here, though every honest person knows just how she feels. I had a good moment with it the other day, though. I said to the class, “Who approves of Clarissa’s reaction?” They looked at me blankly; no one raised a hand. “Who disapproves of it?” I asked, imagining I would get a livelier response. But they still looked at me blankly, and only one or two hands straggled up. Finally, I said, “Who knows you’re supposed to disapprove of this, but the complexities of human emotion being what they are, you see where Clarissa is coming from?” Most hands shot into the air, and one student even exclaimed, “Oh yeah, definitely!” I call that a victory for aesthetics, and I imagine the pupil of Clara Pater and the self-elected sister of Shakespeare smiling slyly somewhere further back or further on in the stream of time.

Mendelson doesn’t class Woolf with Shakespeare. Following Auerbach’s Mimesis, he prefers the almost more august company of the epic poets: Homer, Dante, Goethe. I think placing her in this rather masculinist lineage misses something of her feminist anti-epic stance; the fluidly imaginative dramatist and lyricist Shakespeare, with all of his own beauty and fun, really does seem her truer companion. Mendelson also champions her against Joyce. He writes:

One of the ways Woolf made Mrs. Dalloway more profound and more disturbing than its model Ulysses was by adding Septimus’s chosen death. No one in Ulysses is threatened with death; the deaths that occurred in the past were all natural ones; Leopold Bloom’s most dangerous moment occurs when someone throws a biscuit tin at him and misses.

But this is wrong on one point of fact and, more broadly, on the modernist epic’s general political tenor. First, Bloom’s father, Virag, did not die a natural death but rather took his own life, not unlike Septimus. Second, the two episodes of comic violence in the novel—the nationalist’s would-be assault on Bloom and the English soldier’s attack on Stephen—have their deadly serious dimension. Each stands for forms of world-historically lethal violence: that of anti-Semitism and of British imperialism, respectively.

Which isn’t to say that modernism’s two great day-in-the-life novels can’t be productively or amusingly compared. I wrote an essay on just this theme for Bloomsday 2018 and made my own case for Woolf:

Though Ulysses scrupulously if rather literally mimics the dream-state in “Circe,” which is a just a warm-up for Finnegans Wake, Mrs. Dalloway, with its transience of perception from character to character across expanses of consciousness as well as social space, is the more winningly dream-like achievement. It is Joyce’s formalist literalism, his resolute commitment to achieving every (sometimes inorganic) experiment, that Woolf lacks: this is what she means in her censure of the “tricky,” and I think she is more right than wrong.

But, I conclude, we don’t have to choose between works on this level of literary achievement. Fictions that make themselves so central crystalize whole modes of perception, styles of sensibility, epochs and cities, ethical climates. As a reader, in most moods I prefer Ulysses, while as a writer, I am much closer to the Woolf of Mrs. Dalloway. Obviously, we need them both, or at least I do.

#virginia woolf#edward mendelson#merve emre#james joyce#literary criticism#modernism#british literature

1 note

·

View note

Text

Here's my top 10 dilfs of the week folks!!! Comment below your favorite dilfs.

1. Gregory Peck

2. Clancy brown

3. Tim Roth

4. Matthew Modine

5. Johnny Knoxville

6. Ben Mendelson

7. Gael Garica Bernal

8. Kent Nelson

9. Edward Norton

10. Robert Redford

#clancy brown#tim roth#ben mendelsohn#gael garcia bernal#robert redford#johnny knoxville#matthew modine#pierce brosnan#gregory peck#edward norton

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023

key

↻ = re-read

☞ = continuing (started previously)

✑ = for school

☏ = others recommended and/or gifted to me

✧ = favorites

𓆱 = northern arizona

- hard aground by james w. wall

- ↻ moby-dick; or, the whale by herman melville

- shockwave by paul ruditis

- the expanse by j. m. dillard

- last full measure by michael a. martin & andy mangels

- surprise! by nichelle nichols, sondra marshak, & myrna culbreath

- the good that men do by michael a. martin & andy mangels

- and how are you, doctor sacks?: a biographical memoir of oliver sacks by lawrence weschler

- how to change your mind: what the new science of psychedelics teaches us about consciousness, dying, addiction, depression, and transcendence by michael pollan

- ✑ rhetoric and human consciousness: a history (5th ed) by craig r. smith

- ✑ how english works: a linguistic introduction (3rd ed) by anne curzan and michael p. adams

- ✑ goodbye to all that by joan didion

- ✑ disappearance by carrie brownstein

- ✑ debts and lessons by zadie smith

- ✑ baby yeah by anthony veasna so

- bone in the throat by anthony bourdain

- the man who loved alien landscapes by albert wendland

- ✑ notice by jessica handler

- ✑ joyas voladoras by brian doyle

- ✑ proxies: essays near knowing by brian blanchfield

- ↻ night sea journey by john barthes

- ✑ consider the lobster by david foster wallace

- admissions: a life in brain surgery by henry marsh

- dino: living high in the dirty business of dreams by nick tosches

- ✑ the book of delights: essays by ross gay

- frank sinatra has a cold by gay talese

- inventing jerry lewis by frank krutnik

- ✑ whatever the weather by linda tran

- ✑ the gift of strawberries by robin wall-kimmerer

- fried walleye and cherry pie: midwestern writers on food, edited by peggy wolff

- tomorrow and beyond: masterpieces of science fiction art, edited by ian summers

- stories and prose poems by aleksandr solzhenitsyn, trans. michael glenny

- ✑ in cold blood by truman capote

- w. h. auden: selected poems, edited by edward mendelson

- 95 poems by e. e. cummings

- ↻ dawn by elie wiesel

- ☏ 20020: the future of college football by jon bois

- ☏ the postman by david brin

- slouching towards bethlehem by joan didion

- who by fire: leonard cohen in the sinai by matti friedman

- in the house upon the dirt between the lake and the woods by matt bell

- zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance: an inquiry into values by robert m. pirsig

- ✑ essays one by lydia davis

- the book of eulogies: a collection of memorial tributes, poetry, essays, and letters of condolence, edited by phyllis theroux

- ✧ kneller's happy campers by etgar keret

- the bus driver who wanted to be god and other stories by etgar keret

- ↻ where the sidewalk ends: poems and drawings by shel silverstein

- aperture 12:4, 1964, edited by minor white

- the complete peanuts, 1959-1960 by charles m. shultz

- ✧ letters to milena by franz kafka

- aredo by grace smith

- the last lecture by randy pausch & jeffrey zaslow

- the bug wars by robert asprin

- leaves of grass: “first” and “death-bed” editions by walt whitman

- something alive by keegan grau

- ↻ moby dick; or, the whale by herman melville

- hunger makes me a modern girl by carrie brownstein

- ✧ our numbered days by neil hilborn

- book of mercy by leonard cohen

- some ether by nick flynn

- death of a lady's man by leonard cohen

- the white album by joan didion

- in fact: the best of creative nonfiction, edited by lee gutkind

- ✧ kurt vonnegut: letters, edited by dan wakefield

- spent saints & other stories by brian jabas smith

- reckless daughter: a profile of joni mitchell by david yaffe

- day by elie wiesel

- william carlos williams: the collected poems 1909-1939, edited by walton litz and christopher macgowan

- 𓆱 quench your thirst with salt: essays by nicole walker

- 𓆱 package fever by anahi molina

- 𓆱 tumbling toward awareness by anahi molina

- 𓆱 if i could just see the levee from my backyard by anahi molina

- 𓆱 undertones by anahi molina

- 𓆱 building the dream: lego friends and the construction of human capital by christopher schaberg, ginger grimstein, waverly evans, paige franckiewicz, nino hernandez, terran lumpkin, anahi molina, & adelaide wight

- 𓆱 interview with margarida vale de gato by anahi molina

- love in the time of cholera by gabriel garcía márquez, trans. edith grossman

- bagombo snuff box: uncollected short fiction by kurt vonnegut

- 𓆱 evening with grandma by anahi molina

- 𓆱 the gods are dead by anahi molina

- 𓆱 namesakes by anahi molina

- ☏ a book of common prayer: a novel by joan didion

- grapefruit: a book of instructions and drawings by yoko ono

- ☏ bluets by maggie nelson

- cradle book: stories & fables by craig morgan teicher

- ☏↻ the gift: poems by hafiz, the great sufi master, trans. daniel ladinsky

- ☏ i heard god laughing: renderings of hafiz by daniel ladinsky

- hunger: a memoir of (my) body by roxane gay

- our babies, ourselves: how biology and culture shape the way we parent by meredith f. small

- ☏ the overstory: a novel by richard powers

- ☏ having and being had by eula biss

- the two cultures and the scientific revolution by c. p. snow

- ☏ dogsucker: the written oral by lawrence lenhart

- 𓆱 backvalley ferrets: a rewilding of the colorado plateau by lawrence lenhart

- post office by charles bukowski

- consider the lobster and other essays by david foster wallace

- zoologies: on animals and the human spirit by alison hawthorne-deming

- ↻ the rainbabies by laura krauss melmed

- billions & billions: thoughts of life and death at the brink of the millenium by carl sagan

- ☏ zami: a new spelling of my name: a biomythography by audre lorde

- the paper menagerie by ken liu

- ☏ the member of the wedding by carson mccullers

- the handsomest drowned man in the world by gabriel garcía márquez

- the joy of sex by alex comfort

- open all night: new poems by charles bukowski

- ham on rye by charles bukowski

- howl’s moving castle by diana wynne jones

- ☏ norwegian wood by haruki murakami

- the gales of november: the sinking of the edmund fitzgerald by robert j. hemming

- ✑ the rise of silas lapham by william dean howells

- ✑ girl by jamaica kincid

- everyone but me wrote this by anahi molina

- ✑ a rose for emily by william faulkner

- ✑ sister carrie by theodore dreiser

- ✑ in praise of gossip by patricia meyer spacks

- ✑ the husband stitch by carmen maria machado

- ✑ the way the end of days should be by diane cook

- ✑ the tomb of wrestling by jo ann beard

- ✑ oronooko: or, the royal slave by aphra behn

- ✑ the jungle by upton sinclair

☇ new york times article reading list

- ✑ bless me, ultima by rudolfo anaya

- ✑ kindred by octavia butler

- ✑ the awakening by kate chopin

- ✑ behave: the biology of humans at our best and worst by robert sapolsky

- ☏ happening by annie ernaux

- ✑ m. butterfly by david henry hwang

- ✑ my ántonia by willa cather

- here is your war by ernie pyle

- ✑ the whale caller by zakes mda

- ✑ sáanii dahataał / the women are singing: poems and stories by luci tapahonso

- ✑ in dubious battle by john steinbeck

- ↻ sarah, plain and tall by patricia mclachlan

- ✑ “the rockpile” by james baldwin

- i will not leave you comfortless: a memoir by jeremy jackson

- fifty famous people by james baldwin

- ✑ “shiloh” by bobbie ann mason

- ✑ “cathedral” by raymond carver

- you get so alone sometimes that it just makes sense by charles bukowski

- ✑ slaughterhouse-five by kurt vonnegut

- dead babies by martin amis

-> view december

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

not to get crazy but would i be able to read your lot 49 essay?

yes absolutely.........nightmare pynchon essay that HAD to be extensively about neoplatonism for some reason (the class was called Neoplatonism Across Time And Faith) under the cut.

Neoplatonic paranoia and the (im)material “hermeneutics of unknowing” in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49

At first blush, the bizarre fragmentations, cluttered material cultures, and satirical, postmodern remove of Thomas Pynchon’s novels appear incompatible with any model of sincere religious devotion, much less the hierarchy of heavenly order espoused by classical Neoplatonists. In The Crying of Lot 49, our heroine, the suburban California housewife Oedipa Maas, is indeed never entirely sure what she should believe. Following the death of her former lover, the real estate mogul Pierce Inverarity, Oedipa chases the possible existence of “Trystero,” an extra-governmental mail delivery system whose omnipresence seems both inescapable and highly suspect. As Oedipa—and the novel’s voice—descend into a state of perpetual paranoid vigilance with regards to signs of Trystero’s presence, we arguably fail to reach a true sense of united faith.

Many scholars have disputed the notion that Lot 49 offers a vision of a disorganized—and consequently, disenchanted—world. In “The Sacred, The Profane, and The Crying of Lot 49,” Edward Mendelson maintains that Pynchon’s narrative “describes a gradual revelation of order and unity within the multiplicity of experience,”[1] through which Trystero is invariably associated with “the language of the sacred and with patterns of religious experience.”[2] Trystero here comes to represent faith for faith’s sake, a metonymic symbol that “has no hieratic significance in itself.”[3] In this essay, I extend Mendelson’s reading to centre Oedipa’s paranoiac orientation towards the very existence of the “order and unity” that Trystero’s (alleged) arrival promises. If Trystero is the arrival of the transcendent, Oedipa in her suspicious state is both fervently desperate for its arrival and certain that she cannot be certain of it. Rather than dismissing this paranoia as a mere inability to confront some fundamental kernel of religious truth, I ask what it might mean to read paranoia as a mode of (specifically Neoplatonic) faith unto itself. Modifying Paul Ricoeur’s definition of paranoia as a “hermeneutics of suspicion,”[4] I define Lot 49’s paranoia as a “hermeneutics of unknowing,” after the author of The Cloud of Unknowing, a text that asks the faithful to embrace the ultimate inscrutability of the divine. The Pynchonian paranoiac must put faith in the profound unknowability of what she seeks, the knowledge that, for all the material approximations of the divine she finds, she may “never touch the truth.”[5] Approximating the presence of some transcendence through an unfulfillable quest that projects a “shape and form on things which have neither,”[6] Oedipa’s faith, a sincerity masquerading as disbelief, produces a structure of the unknowable, a re-instation of the divine in America’s materiality.

The unifying paranoia that Oedipa finds departs from her world of origin, a disenchanted and hyper-material one that struggles with the very notion of “belief.” Immediately before the novel descends into its increasingly slippery, increasingly hyper-vigilant affective mode, the Californian suburbs are characterized, not by a suspicion (in other words, a professing of belief in something beyond what is there) but rather an all-encompassing disbelief. The first action Oedipa takes after hearing of Inverarity’s death is an attempt to connect with the transcendent under the emptying gaze of the material; “stared at by the greenish dead eye of the TV tube,” she “spoke the name of God, tried to feel as drunk as possible.” To no avail: “this did not work.”[7] This dizzying, searching “drunkenness” is later to completely reorganize Oedipa’s subjectivity; for now, however briefly, she can feel what Dwight Eddins characterizes as a “nostalgia for cosmic harmony,”[8] an “implicit lament for the harmonizing constructs that made the universe a home.”[9] Unable to yet reach some Californian iteration of Pseudo-Dionysius’ “inscrutable One,”[10] she instead descends into the material trappings of the housewife: “the layering of a lasagna, garlicking of a bread, tearing up of romaine leaves.”[11] The business of a disenchanted life carries, briefly, on.

Though gendered being structures Pynchon’s novel,[12] Oedipa’s suburban disenchantment is hardly the unique provenance of the housewife. Her husband, Wendell “Mucho” Maas, is almost comically, almost cosmically incapable of summoning up belief. “I don’t believe in any of it, Oed,”[13] is his continuous refrain with regards to his current employment as a radio DJ or torturous past as a used car salesman. “At least he had believed in the cars,” Oedipa reassures herself, but years after no longer selling them, Mucho is repulsed and “sickened” by the “actual residue of these lives” contained within the cars he swept out and sold: the “clipped coupons promising savings of .05 or .10, trading stamps, pink flyers advertising specials at the markets, butts, tooth-shy combs, help-wanted ads,” all “coated uniformly, like a salad of despair, in a gray dressing of ash, condensed exhaust, dust, body wastes.”[14] His disbelief represents the fundamental failings of the material, the entrapped clutter of what Pseudo-Dionysius calls the fact that “all beings fall short of goodness and being in proportion to their remoteness from the Good.”[15] What, indeed, could be more decidedly remote from Godliness than the “residue of lives” held by a hollowed-out used car?

As Trystero’s world-ordering structure approaches, Oedipa cannot linger in Mucho’s disbelief for long. Mere pages after Mucho whistles a shiny new tune by “an English group he was fond of but did not believe in,”[16] a still-newer way of organizing the world appears on the scene, a still-forming group called The Paranoids with false English accents but a very real presence.[17] Their presence stalks the novel, dogging Oedipa as one of the endless array of signs that, to Mendelson, “intrude iteratively on the book’s heroine until they entirely supplant the undemanding world with which she had once been familiar.”[18]

By taking on the paranoid position as, in Sedgwick’s words, “a way…of seeking, finding, and organizing knowledge,”[19] Oedipa enters a new drama and possibility of belief to which she was not previously privy. Paradoxically, her departure from this disenchantment takes place through the ascription of importance to signs, symbols, and arbitrary material detritus; the material world is the locus from which her faith must necessarily depart. Early in the novel, Oedipa, looking on “from above” in an early attempt to contemplate her world’s wider structure, finds meaning in Southern California’s ordered sprawl:

The ordered swirl of houses and streets, from this high angle, sprang at her now with the same unexpected, astonishing clarity as the circuit card had. Though she knew even less about radios than about Southern Californians, there were to both outward patterns a hieroglyphic sense of concealed meaning, of an intent to communicate. There’d seemed no limit to what the printed circuit could have told her (if she had tried to find out); so in her first minute of San Narciso, a revelation also trembled just past the threshold of her understanding.[20]

Here, Oedipa begins to read through the “strong theory” of paranoia, the “theory of wide generality”[21] that, in taking on the size and scope of a literal birds-eye view, begins to approximate “a revelation” that she cannot yet fully locate. Her faith in the possibility of something wider, of a not just “hieroglyphic,” but hierophanic “sense of concealed meaning,” is a faith of abstraction that must necessarily tether itself to non-abstracted elements. The language of a concealed truth that can reveal itself through material proxies for what is “inscrutable and unsearchable”[22] re-inscribes the writing of Pseudo-Dionysius on have, themselves, no form. In the “Divine Names,” he speaks of “something above and beyond speech, mind, or being itself” that nevertheless comes, in its transcendence, “clothed in the terms of being, with shape and form on things which have neither.” Where Mucho’s relationship to the radio is one of dissociated disbelief, Oedipa, vaunted by her vigilant curiosity into the mode of “searching,” pries the radio open and locates a pattern within its seemingly arbitrary “terms of being.” It is through the process of “opening,” the determined, if at times equally torturous, investigation of meaning, that Oedipa uses the material to surpass the same material plane in which her husband appears to be trapped.

“God, hieroglyphics,”[24] she muses. And hierophany, too. The (re)-iteration of this sign gradually becomes a mode by which she can connect with some broader unifying mode of being. “Shall I project a world?” she writes under the symbol after attending the performance of a heavily-coded play that reveals the word “Trystero” to her for the first time.[25] The horn is the material focal point through which the world is revealed, one of what Pseudo-Dionysius calls “numerous symbols…employed to convey the varied attributes of what is an imageless and supra-natural simplicity.”[26] Oedipa’s paranoiac way of “reading the world” projectsa transcendent unity and “supra-natural simplicity” into the symbol. For something to be projected, here, is not a normative statement of its falsehood or absence. It is instead a reaching for the very “name of God,” whose particularities might elide the worshipper, but induces, nevertheless, a piercing belief beyond what is.

Trystero’s horn leads Oedipa in questing motion, through both the structure of the immaterial world and the physical streets of “the infected city,”[27] which serves, once more, as a material corollary to the transcendent and ephemeral. Reading gnostic Neoplatonism into Pynchon’s longer, later works, Richard Hardack posits that he “characterizes a Gnostic or surrealist geography in which matter doubles its equal and opposite spirit.”[28] The spirit, acquiescing to Hardack’s reading, traces through San Francisco’s “far blood’s branchings,” as Oedipa is moved by both a fervent certainty of the symbol’s presence and an inability to truly confirm her own faith: “in Chinatown, in the dark window of a herbalist, she thought she saw it on a sign among ideographs. But the streetlight was dim.” Later, a greater certainty when Oedipa sees “two of them in chalk, 20 feet apart” on a sidewalk, surrounded by strange symbols. To track Trystero’s horn is to engage in a process of approximation and incomplete (re)-iteration of what might be, to seek what is “appropriate” but nevertheless lacks the total explanatory power of the purely transcendent. As she searches, Oedipa wonders “if the gemlike ‘clues’ were only some kind of compensation. To make up for her having lost the direct, epileptic Word, the cry that might abolish the night.”[29] Seduced by the “promise of the definitive revelation” offered by gnosis,[30] Oedipa comes to confirm Pseudo-Dionysius’ theory that the transcendent One indeed holds “an understanding beyond being,” producing a fundamental gap of knowing between the “direct, epileptic” unity, the capital-W-Word, and the veiled world-forms through which we might attempt to reach it.

The novel’s practice of reading the transcendent into the mundane opens up from postmodern chaos an organized universe in which one could find faith. Specifically, it presents the process of paranoia as a map to revelation. Pynchon’s narration confirms the value of paranoia as something more than an affective experience; rather, or additionally, it is an epistemological strategy. Musing on various knowers—the “saint,” the “clairvoyant,” the “dreamer”—who might approach and connect to the transcendent, the narration incorporates “the true paranoid for whom all is organized in spheres joyful or threatening about the central pulse of itself.”[31] Paranoia, in other words, generates a scaffold for the relationship between the material and immaterial worlds, an “organization in spheres” not dissimilar to the “mapped universes” presented by early Classical Neoplatonists, most notably Plotinus’ architecture of the universe,[32] by which “all is organized” from the “central pulse” of the one from which matter, soul, and platonic forms emanate. Paranoia is a mode of mapping and maintaining one’s relation to the material and immaterial worlds. As Oedipa’s psychiatrist, Doctor Hilarius, says of his aversion to LSD, “I never took the drug, I chose to remain in relative paranoia, where at least I know who I am and who the others are.”[33] This confirmation of paranoia as something that orients one’s own presence in the cosmos equally confirms Oedipa’s first instance of paranoia, the one that precedes even Trystero’s intrusion: her refusal to take the medication that Hilarius offers her, noting that “I don’t know what’s inside them.”[34] This position provides an ordered orientation of faith amid the chaos of her world’s material detritus. Though Oedipa pursues an “either/or” anxiety that maintains that either Trystero is real, or she is a “true paranoid,” the text presents, over and over again, the possibility that the two are commensurable, perhaps even requisite for each other.

Though paranoia is a faithful mode of reading the world, though it sharpens some of San Narciso’s edges, it is incapable of providing an actual crystalline “clarity.” The closer Oedipa’s vigilant pattern recognition brings her to some divine recollection, the more it brings her towards a kind of certainty of her own uncertainty, an in-provable “unknowing” to which she must submit if any answers are to be approximated. As all that she previously knew abandons her, she enters into what the author of The Cloud of Unknowing calls a “darkness” that is “always between you and your god, no matter what you do, prevent[ing] you from seeing him clearly."[35] If Trystero is a form of God in its transcendence and world-structure, despite its ominousness and possibly sinister correlations (as Mendelson notes, “the demonic is a subclass of the sacred, and exists, like the sacred, on a plane of meaning different from the profane and the secular”[36]), it is perpetually concealed from Oedipa in a “cloud of unknowing”; the more she approximates understanding, the less she understands.

Towards the end of the novel, for instance, Oedipa is ostensibly given answers. Having chased down the appropriate history books, she maps a complete narrative of “the secular Trystero” and the concrete, worldly history of the organization’s emergence in Europe hundreds of years before. It utterly fails to provide her with the psychic or spiritual clarity she seeks: “beyond its origins,” she laments, “the libraries told her nothing more about Tristero.”[37] When transcendence comes, it arrives in creeping uncertainties; shrouding Oedipa’s subjectivity in “a privation of knowing,” an inability to define what one “worships” or seeks even as one ascends into a “state of contemplation” with regards to spiritual truth.[38] We see it in the “haze” that seeps, obscurifying, through the streets of San Francisco, in the disintegration and ephemerality of the “clues” Oedipa attempts to amass, in multiple characters’ pronouncements that though she can seek it into perpetuity, she may “never touch the truth.” In The Cloud of Unknowing, the piercing sensation that anchors one to the untouchable spiritual is the “loving power,” rather than the “knowing power,” the deep and abiding love for one’s God that allows the seeker of spiritual fulfilment to find peace in the darkness in “always crying out after him whom you love.”[39] For Pynchon’s paranoiac epistemology, the “cry” that anchors one’s sensing-self to a transcendent thing that will always elide comprehension is, not love, but apprehension and trepidation. After all, to a Pynchonian paranoiac they are one and the same, the universe organized around the investigator in spheres “joyful or threatening”; it matters not which.

The novel ends in definitive opacity, the paradoxical knowing of unknowing. As Oedipa awaits, in Lot 49’s last paragraph, the auctioning of a bundle of “Tristero forgeries” from which she hopes to finally glean the truth, “an assistant closed the heavy door on the lobby windows and the sun.”[40] She is enclosed, now, in a “darkness” of breathless uncertainty; in placing her faith in the lot, and by consequence Trystero and her own paranoiac drive for answers, the rest of the world, its very sun, is concealed from her. She must, as The Cloud of Unknowing demands, place a “cloud of forgetting” between herself and the material trappings and clues from which her search initially departed. Sealed in the auction room, sealed between the clouds of unknowing and forgetting in a state of “waiting” from which she is never released, Oedipa must put absolute faith in the processes of suspicion, and the direction in which it orients her.

Pynchon’s novels are an exercise in finding faith in faithlessness and vice versa, a kind of roadmap, complete with stutters, lapses, and moments of uncertain “haze,” to the approximation of belief in a universe of postmodern senselessness. His philosophical framework in Lot 49 reaches back to the world-structures of early Neoplatonists, who both map the cosmos with definitive clarity and read the fundamental obscurity of a world’s transcendence. The simultaneous avowed self-certainty and doubting haze of the paranoid position generate a twentieth-century mode of faithfulness, one that centres the material as a mode to reach beyond it, by whatever means possible. The paranoid hermeneutics of Pynchon’s world therefore provide a mode of reading the material/immaterial tensions that so vexed classical Neoplatonists, seeking to leave worldly embodiments and desires behind and yet, as human beings, so invariably tangled in their trivialties. In order for the world to fall away, Pynchon posits, we must focus on the world—its cigarette butts, lottery tickets, scrawled holy invocations on a graffitied bathroom wall. It is only then that we might know what it is we fail to know at all.

[1] Mendelson, “The Sacred, The Profane, and The Crying of Lot 49,” 183.

[2] Mendelson, “The Sacred, The Profane,” 188

[3] Ibid, 192.

[4] Paul Ricoeur. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation, trans. Denis Savage (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 33.

[5] Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49, (New York: Harper, Perennial Fiction Edition, 1986), 85.

[6] Pseudo-Dionysius, Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, Luibheid, Colm, trans., (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1987), 52.

[7] Pynchon, Lot 49, 3.

[8] Dwight Eddins, The Gnostic Pynchon, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), 10.

[9] Eddins, The Gnostic Pynchon, 12.

[10] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, 49.

[11] Pynchon, Lot 49, 6.

[12] In manners, though fascinating, too complex to do justice to within the scope and length of this essay.

[13] Pynchon, Lot 49, 12.

[14] Pynchon, Lot 49, 15.

[15] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, 87.

[16] Pynchon

[17] As worldly things fall away across the course of the novel, it will be revealed as the oldest mode of reading of them all.

[18] Edward Mendelson, “The Sacred, The Profane, and The Crying of Lot 49” in Individual and Community: Variations on a Theme in American Fiction, Ed. Kenneth H. Baldwin and David K. Kirby, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1975), 187.

[19] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You” in Touching Feeling. Duke University Press, 2002, 130.

[20] Pynchon, Lot 49, 24.

[21] Sedgwick, Paranoid Reading, 134.

[22] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, 50.

[23] Pynchon, Lot 49, 52.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Pynchon, Lot 49, 101.

[26] Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, 52.

[27] Pynchon, Lot 49, 116.

[28] Richard Hardack, “Consciousness Without Borders: Narratology in ‘Against the Day’ and the Works of Thomas Pynchon,” Criticism 52, no. 1 (2010): 91–128, 94.

[29] Pynchon, Lot 49, 118.

[30] Eddins, The Gnostic Pynchon, 118.

[31] Pynchon, Lot 49, 160.

[32] Lloyd Gerson, “Plotinus,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta, Fall 2018 (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, 2018), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/plotinus/.

[33] Pynchon, Lot 49, 136.

[34] Ibid, 7.

[35] Walsh, James, ed, The Cloud of Unknowing, (Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1981), 120.

[36] Mendelson, “The Sacred, The Profane,” 191.

[37] Pynchon, Lot 49, 160.

[38] Cloud of Unknowing, 125.

[39] Cloud of Unknowing, 120.

[40] Pynchon, Lot 49, 183.

#this is the last essay i ever wrote for college ever#it's not 'good' per se#answered#means the WORLD to me that you asked this. to be clear

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WELCOME TO HALF MOON BAY —

please review our welcome list here.

Ash with Avan Jogia as Jayesh Acharya, 33, Musician and Radio Host

Ash with Priscilla Quintana as Alycia “Aly” Acosta, 32, Business Executive for The Acosta Group

Bri with Theo James as Andrew Hayes, 34, PAC (Political Action Committee)

E with Michiel Huisman as Aiden Mendelson, 37, General Surgeon

Lily with Hazal Filiz Küçükköse as Amara Arslan, 32, Owner of Pasta Moon / Artist

J with Jake Weary as Justin Edwards, 31, Sales Associate at Vinyl Records Studio

J with Clayton Cardenas as Gabriel Fuentes, 33, Tattoo Artist at Celestial Ink

Jackie with Josh Segarra as Nicolás "Nick" Marin, 35, Bartender & Manager at Sea N Sips

Jamie with Camila Mendes as Opal da Silva, 30, Con Artist

Jamie with Nick Robinson as Jackson Darby, 27, bartender at Cameron's Pub

1 note

·

View note

Text

"ROBBED WIDOW OF SOLDIER WHO DIED IN DIEPPE RAID," Toronto Star. April 9, 1943. Page 2.

----

Thomas Brown Jailed Three Months for Stealing Pension Cheque

----

"MEAN THING TO DO"

----

"A" Police Court, City Hall; Magistrate Browne.

"You know that this woman's husband was killed at Dieppe, and that the money you stole was a government pension cheque from Ottawa," said Magistrate Browne to Thomas Brown, up for sentence on charge of stealing $75 from Mrs. E. Griffin.

"It was a mean thing to do," added his worship imposing a term of three months.

Evidence given at a previous hearing showed that the accused knew the complainant. having met her in a restaurant where she was employed. The court was told that she took him to her home to clean some floors. She said that the money was in her purse and the accused took it.

Accused admitted buying a wrist watch with part of the money. He had $37 when arrested.

"For a young man. you have a very bad record." remarked Magistrate Browne to Peter Leclair, a soldier, convicted of assaulting P.C. Tom Duffy and also stealing a pound of tea. He was sentenced to four months on each count, to run concurrently.

Miss A Mitchell, a waitress in a Queen S. W. restaurant, said she saw accused taking the tea and leave. "I told a waiter and he went looking for him." she said,

A. Evans stated that he missed accused awhile and then saw him, some distance from the restaurant.

P.C. Duffy told of seeing the accused being chased. "I caught him," said witness. "He tried to kick me in the stomach and failed. He kicked me in the shine. We tussled and he knocked my helmet off."

Leclair denied taking the tea, but had nothing to say regarding the assault.

For failing to notify the registrar of his change of address, William Kerr, subject for military call. was fined $25 and costs or 30 days. He pleaded guilty,

Constable Glanfield. R.C.M.P. fold Magistrate Browne the police had been trying to locate accused for some months. "He admitted moving often," said the officer.

Donald Davey pleaded guilty of stealing a case of cigarettes from a transport truck. "He took the cigarettes, valued at $150, and sold them for $80, related Detective George Elliott.

"You will go to jail for three months." ruled Magistrate Browne.

Thirty days and a fine of $200 or 30 additional days, was the penalty given Edward Eisen, after he pleaded guilty of keeping a betting house on Yonge St..

Police Constable Fred Paveling said that over a period of three weeks P.C. Lamont made 12 bets on horses with accused.

Defence Counsel H. L. Mendelson pleaded for a reduction of the jail term.

"He was convicted once before on a similar charge." replied his worship

Appearing for sentence for stealing four radiator caps from parked motor cars on Colborne St. James McNeil and Clayton Lovely, first offenders, were given suspended sentence and probation for one year. They were arrested by Constable Agnew at the scene. Both pleaded guilty.

HAD DRUGS, GETS YEAR

---

"B" Police Court, at the City Hall, Magistrate Prentice.

"You will be fined $200 and costs or six months and in addition you will be sentenced to serve 12 months, his worship told David Kerr when he appeared for sentence on a charge of unlawful possession of drugs. On a charge of theft and receiving he was sentenced to additional six months concurrent.

Remanded for judgment and investigation until today after appearance yesterday on a charge of trespassing on the premises of a munitions plant Joseph Harty, 22, was fined 510 or 10 days. Harty had a record, Crown Counsel Malone reported.

Pleading guilty of aggravated assault upon Alee Herasimenko, 63, Dmytro Kowbel, 21, was sentenced to 30 days in jail. Through interpreter Markowitz. complainant stated he had been struck by accused in the kitchen of their Draper St. rooming-house after a verbal argument.

"He called me a name and I struck him," admitted accused.

"A most brutal assault," said Crown Counsel Malone.

HIS FINES TOTAL $70

----

"D" Police Court, at the City Hall. Magistrate Tinker.

Convicted of careless driving, operating a car without a proper license and having liquor illegally, Bruno Maisonneuve was ordered to pay a total of $70 in fines and costs or serve one month in jail. On the first charge. he was fined $50 or 20 days. on the| second $10 and costs or 10 days and on the third charge $10 or one month, sentences concurrent.

Constable Art Hudson said he went to Avenue Ad.., near Heath St., to investigate an accident and found accused standing beside his car, which was up on the sidewalk. "He was in no condition to drive," the officer said, adding that he found 22 full pint bottles of beer in the car.

"He had a beginner's permit but was driving without a licensed driver." explained Constable Hudson.

William Metcalf, driver of the other car, said accused, going in the opposite direction, suddenly swerved and crashed into his car.

Pleading guilty of illegal purchase of beer, John Ribich was fined $25 and costs or 30 days. His Royce Ave. home was declared a public place.

Constable Gordon Deyman said he found 29 quart bottles and 12 pint bottles of beer in the home. Ribich said he purchased six quarts at a brewer's warehouse and the rest from a brewer's driver.

"When I came home from work, I saw the brewer's truck in front of my home. The driver told me he did not have an order to deliver beer in my house, but said that due to icy streets he was unable to make all deliveries and said he would sell me three cases of beer, which I bought."

#toronto#police court#stolen cheque#theft#pension cheque#military widow#assaulting a police officer#resisting arrest#aggravated assault#narcotics possession#illegal beer#liquor control#sentenced to prison#toronto jail#ontario reformatory#fines and costs#canada during world war 2#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada

0 notes

Text

In the twentieth century those interested in poetry had to come to terms with the big beasts of the initials: W.B., T.S., and the upstart, W.H.—and it’s no exaggeration to say that the publication of Auden’s Poems in October 1930 by Faber and Faber, his first commercially published collection, changed poetry in English. Here, from a twenty-three-year-old, was a new tone in the language, a different way of saying, pushing back against expectations of rhythm and syntax and referent. The poems were strange, rich, authoritative.

Certain tropes percolate through the early poetry—stratagems, machinations, espionage—and have been read as symptoms of adolescent rebellion, or the resistance of youthful leftism against the bourgeois establishment, but it’s hard now not to see much of it simply as a consequence of the necessary sexual coding, its power derived from what could not be said. “Here am I, here are you:/But what does it mean? What are we going to do?” (It’s worth remembering that homosexuality was subject to criminal sanctions in Britain until 1967, when Auden was sixty.)

Take the fifteenth poem (they are numbered rather than titled) of the thirty in his first collection:

Control of the passes was, he saw, the key

To this new district, but who would get it?

He, the trained spy, had walked into the trap

For a bogus guide, seduced with the old tricks.

At Greenhearth was a fine site for a dam

And easy power, had they pushed the rail

Some stations nearer. They ignored his wires.

The bridges were unbuilt and trouble coming.

The street music seemed gracious now to one

For weeks up in the desert. Woken by water

Running away in the dark, he often had

Reproached the night for a companion

Dreamed of already. They would shoot, of course,

Parting easily who were never joined.

“Who would get it?” indeed. The poem tells us itself that the “new district” has a “key,” a code, a way of being read. The texture is not without precedent in English literature—the heavy alliteration (line 10, for example, has “weeks,” “woken,” “water”) harks back to Anglo-Saxon verse—though the tone feels entirely new. There is a straightforward-enough reading: a “trained spy” has been betrayed by a “bogus guide” and is now in enemy territory. He’s been abandoned by his handlers and seems sure he will be shot. But ambiguities multiply suggestively. There is an oddness, a dream logic to the lines: water runs away in the dark, the desert seems to bring us to a landscape more psychological than actual. Its symbolism seems allegorical.

0 notes

Quote

Throughout the book, matters of politics or patriotism are steamrolled by corporations, which (like the rocket) transcend nations and their trifling differences. “The true war,” as one character observes, “is a celebration of markets.” Pynchon name-checks Shell Oil, I.G. Farben, and other concerns whose business interests cut across battle lines. A chemical pitchman named Wimpe proudly proclaims that his “little chemical cartel is the model for the very structure of nations.” Another character, Clayton Chiclitz, is a toy manufacturer who recruits war orphans to scrounge for black market bric-a-brac. By the time of Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (set some 20 years after the events of Rainbow), Chiclitz has moved from peddling children’s playthings to heavy weaponry, heading up a mega-corp called Yoyodyne.

This idea of the corporation supplanting the nation-state—what critic Edward Mendelson termed “Pynchon’s new internationalism”—proved the author’s most prescient forecast. In 1973, in the throes of the Cold War, the notion that nations and ideologies would be incidental might have seemed like the stuff of pulpy sci-fi. Before Don DeLillo and George Romero showed supermarkets and shopping malls as temples of spiritual longing, decades before Fukuyama proclaimed “the end of history,” Pynchon saw that the new world order was incorporation: a technological arrangement of global capital that would defy nationality and morality.

We’re All Living Under Gravity’s Rainbow | WIRED

0 notes

Text

In his poetry above all, Auden reckoned with the great historical forces of his age and struggled — genuinely — to arrive at an accurate understanding of & a moral response to them.

0 notes

Quote

Firstly that the question of how good or bad Pound’s poems are is irrelevant (I do not care for them myself particularly); the issue would be the same if some hick newspaper refused, for the same reasons, to print some scribbler they had been in the habit of printing. (Vice versa, of course, if Pound were the greatest poet in the world, it would not entitle him to more lenient penalties for treachery.) Secondly, the issue is far more serious than it appears at first sight; the relation of an author to his work only one out of many, and once you accept the idea that one thing to which a man stands related shares in his guilt, you will presently extend it to others; begin by banning his poems not because you object to them but because you object to him, and you will end, as the nazis did, by slaughtering his wife and children.As you say, the war is not over. This incident is only one sign—there are other and far graver ones—that there was more truth than one would like to believe in Huey Long’s cynical observation that if fascism came to the United States it would be called Anti-fascism. Needless to say, I am not suggesting that you desire any such thing—but I think your very natural abhorrence of Pound’s conduct has led you to take the first step which, if not protested now, will be followed by others which would horrify you.

W. H. Auden (qtd. in Edward Mendelson, “Auden on No-Platforming Pound”)

21 notes

·

View notes

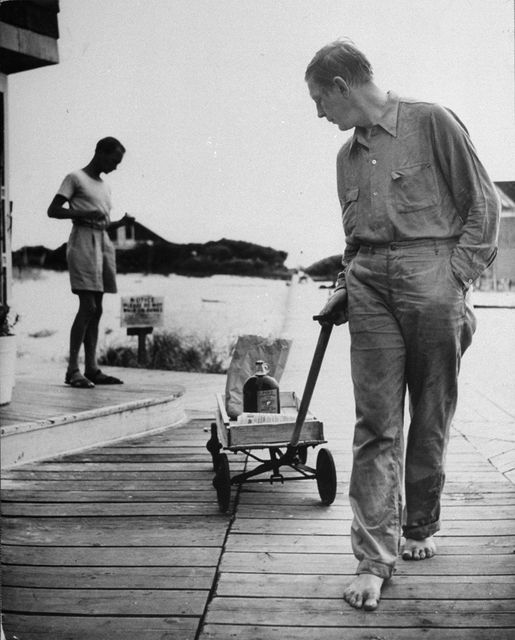

Photo

Photo: W. H. Auden, Fire Island, 1946 (Jerry Cooke/Pix Inc./Time Life Pictures/Getty Images)

* * * * *

W.H. Auden had a secret life that his closest friends knew little or nothing about. Everything about it was generous and honorable. He kept it secret because he would have been ashamed to have been praised for it.

Edward Mendelson: The Secret Auden

http://j.mp/1o9cGxU

The New York Review of Books

* * * *

All I have is a voice

To undo the folded lie,

The romantic lie in the brain

Of the sensual man-in-the-street

And the lie of Authority

Whose buildings grope the sky:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

[From "September 1, 1939"W. H. Auden - 1907-1973]

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yes, @trustworthy-liar and I have plenty of headcannons regarding all the lives of Jonah Magnus.

Continuation of THIS POST.

Jonah Magnus

Charming young man who has one day appeared in the society and acted like he always belonged there. He doesn’t like talking about his past.

When he was young he read all books in a family library. After arriving to London he was very surprised by how much he still doesn’t know.

Met Barnabass Bennet for the first time when the young man was travelling through Scotland.

Barnabass later intorduced him to all his acquaintances in the high society such as Robert Smirke and all the others.

Very easily forgets himself in his studies and research especially when there's no one around to drag him away and force him to eat and sleep.

Still genuenly cared about his peers but unfortunately he cared about a knowledge a bit more.

Infamous member of many gentlemen clubs.

Dissapeared at age 83. His body was never found. There are rumors his ghost still wanders through the halls of the Magnus insitute.

(years mark the time Jonah’s conciousnes was inhabiting the body - who would guess that it correspond with time as the Head of the institute as well)

William Bennett

Young, pretty, had decent amount of money and fascinated by all the wierd and obscure things. He was naturally very intriqued when Jonah Magnus offered him a private tour through the artifacts...

Jonah took over William Bennett at age 21. Feeling sour after unsuccesful ritual he decided to enjoy the decadence.

Met with Mordechai once. Lets say Mordechai was not amused by Jonah figuring some way to live longer. And also by the name of the person he chose.

Accidentally got adicted to opium. Jonah didn’t realized till he skipped bodies becuase he was sure he could stop anytime he wanted.

The only time Jonah travelled out of England - to the world expo in Paris in 1989 (“oh it will be probably lame not as cool as ours”). He realized he did not get over his seasickness and fear of ocean by skipping a body way too late.

He met his death at age 47 becuase he got plenty of enemies and also there started to be several rumors about him. Also the opium addiction. Overall Jonah did not treat this body very well - yes, bodies are disposable but he is still living in them...

Jonah made the death look like a murder and framed one of his enemies for it.

Edward Lyon

Edward was boring looking librarian of the Magnus Institute who cared more about books than he cared about people

Body snatched at age of 34

Everyone wrote off Edward’s sudden change of personality as power getting into his head

Jonah establisehed closer relantionship with the Lukas family again - through the dullest person ever, Thomas Lukas

Went back to meticulously researching the rituals and haven’t stopped since

Died at the age of 64, written off as a heart attact (but for real Jonah just wanted to enjoy 1920′s as a young man)

Augustus Moore

Served in the WWI and after it ended he´was seeking a new life in London and decided to give a statement to the Magnus Institute where he caught the eye of the Head of the institute who offered him a job in the artifact storage

Jonah was jeallous of Augustus being young and having fun so he took over his body at 28 even though he previously planned to wait a bit longer

Around year 1929 he shortly reconnected with Thomas Lukas (who never figured out that he is the same person as Edward or Jonah Magnus - no matter how many not even subtle hints he was giving him)

Spent most of the WW2 hidden in the tunnels scared for his life institute (”Did I miss a Slaughter ritual?”)

During the great fog in 1952 got scared that there was succesfull Lonely ritual

Because there was way too many fog problems in London he decided to skip bodies in 1965 just to be prepared if there was really some ritual

Died at age 65 in a fire, absolutely unrelated to the conflict Jonah was having with the cult of the lightless flame at the moment

Richard Mendelson

Worked in the Library, double faced, acted nice to everyone but behind their back tried to discredit them to make himself look better

At last he got his promotion (to Head of the institute) at age 33

To Jonah’s dismay Mendelson turned out to be lactose intolerant (no cakes for Jonah :( )

This time he did not come to Lukas but Lukas came to him and boy was he disapointed, Nancy Lukas turned out to be real pain in the ass

Made a wagger with Nancy wether woman can be the Archivist and survive at least 10 years on such position (almost no archivist actually did) - unfortunatley the chosen Archivist was no one else but Gertrude Robinson herself

Unfortunately met his end at age of 47 in a car crash (because Jonah really wanted an icecream and cheese without consequences)

This only fed the rummors about the position of the head of the institute being cursed by Jonah Magnus himself (technically they were not wrong...)

James Wright

Filling clerk at the research department, unhappy, divorced and lonely man with past alcohol adiction problems

Body snatched at age 45, Jonah wanted much younger body of a man who he thouht was named Robert, turns out his name really was just “Bob” and he coudn’t have that

Turned out James had kids, one of them tried to reconect with their absent fater. Jonah was not very happy about it.

In 1989 met with Peter Lukas

Since he couldn’t have alcohol, he wanted to try opium again (moderately this time) and was shocked that it was illegal, so he turned to smoking and cake

Staged his death at age 68 as a suicide

Elias Bouchard

Worked at the artifact storrage

Jonah took his body sooner than previously planned because Elias wanted to get some horrendous tattoo

Jonah threw away all his clothes...but he kept the funny weed socks

Til his end in the Spiral Michael Shelley never figured out why his friend started to act so weirdly (Jonah had it as his side hobby to induce the paranoia in him by acting like the good old Elias to him from time to time)

Peter was very much not amused by this little stunt of Jonah Magnus

Stabbed by his Archivist to death while he was crying like a little bitch he is

𝙁𝙚𝙬 𝙢𝙚𝙢𝙗𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙇𝙪𝙠𝙖𝙨 𝙛𝙖𝙢𝙞𝙡𝙮 𝙬𝙝𝙤 𝙝𝙖𝙙 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙢𝙞𝙨𝙛𝙤𝙧𝙩𝙪𝙣𝙚 𝙤𝙛 𝙞𝙣𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙖𝙘𝙩𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙬𝙞𝙩𝙝 𝙅𝙤𝙣𝙖𝙝 𝙈𝙖𝙜𝙣𝙪𝙨

Mordechai Lukas

Already quite rich and well etabilished in the society

Owns a shipping company, which is later the only reason why he still interacts with people

Met with Jonah on gentleman business meeting, they were introduced to each other by Barnabas on Jonah’s demand

To Jonah’s disgust he got married when he was in his early forties

Around 1830s decided to disappear from the society completely only getting ocasionally annoyed by Jonah

After meeting William Bennett he decided that one lifetime with Jonah was enough and dissapeared into the Lonely forever (as you do)

Thomas Lukas

Mordechai’s possible grandson/grandnephew

Rising child lonely at it’s peak

Already married and with few kids when he met Edward. He heard that cheating partner makes one feel very lonely...

Unlike the other lonely avatars Jonah ever encountered this one was trully indifferent towards anything, driving Jonah mad by rarely showing any reaction

Had a brief relationship with both Edward and Augustus however never caught Jonah’s hints who he really is and just assumed that these eyevatars are all kinda the same

Nancy Lukas

The great pain in Mendelson’s ass

Neither impressed nor charmed by him

Regularly calls him out on his bullshit (sexism)

Lonely feminist - believes that independce for women will make everyone more lonely so she supports it

Calls Mendelson “Dick” because that’s indeed short version of Richard

Slightly intriqued by Gertrude Robinson (what a beautiful loneliness right there)

Peter Lukas

First Lukas after Mordechai who really intrigued Jonah

Originally started an affair with Wright because he thought it nice and lonely to be with someone old, who will soon die (boy was he surprised)

Except the train documentaries his guilty pleasure are also romantic movies with tragic ending (Titanic my beloved)

Actually figured it out on his own who Jonah Magnus is(because of course he wanted to play this game again with this fresh new Lukas)

Anyway both @trustworthy-liar and I still have plenty of headcannons about Jonah and all of his bodies (especially the oc ones) so you can probably expect more detailed posts with thorough biography of every single one of them in the future.

Just to be clear most of the dates as well as all the funfacts are really just our made up headcannons. We didn’t bother writing here some of the cannon events but they are marked on the well-arranged timeline.

#Did we waste our time by thinking way too much about Jonah Magnus and creating way too many headcannon about him?#Yes yes we did and we regret nothing...#Also I apologize for missing date of death on Elias' plate my gf is still in denial#Anyway yeah we still have plenty of thoughts and we will keep making it your problem as well#Or not you dont have to read this#tma#tma ocs#jonah magnus oc bodies#jonah magnus#all the lives of jonah magnus#elias bouchard#james wright#richard mendelson#lonelyeyes#all the more controversial headcannons (because trans jonah) will be in the future posts#mEye post#mEye jonah take

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What Thucydides Knew About the US Today

Everyone who reads Thucydides knows him as the most profound and convincing historian of empire, not only in his own age but also in his explicit and implicit predictions of later ages.

The New York Review of Books

Edward Mendelson

On the morning after the 2016 presidential election I tried to distract myself by reading some pages of Thucydides that I had assigned for a class the next day, and found myself reading the clearest explanation I had seen of the vote that I was trying to forget. In the third book of his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides describes the outbreak of civil war on the northern island of Corcyra in 427 BC:

There was the revenge taken in their hour of triumph by those who had in the past been arrogantly oppressed instead of wisely governed; there were the wicked resolutions taken by those who, particularly under the pressure of misfortune, wished to escape from their usual poverty and coveted the property of their neighbors; there were the savage and pitiless actions into which men were carried not so much for the sake of gain as because they were swept away into an internecine struggle by their ungovernable passions.

The closest thing to a consolation that I found in the election was the catastrophic failure of almost every attempt to predict the outcome by using numerical data, instead of interpreting the passions that provoked it, as Thucydides interpreted the conflict in Corcyra. The most confident pre-election pollsters proclaimed themselves 99 percent certain of the result that didn’t happen. Even the least confident predicted exactly what did not occur.

Everyone who reads Thucydides knows him as the most profound and convincing historian of empire, not only in his own age but also in his explicit and implicit predictions of later ages. One of his great themes is Athenian exceptionalism and the moral and military failures that inevitably issued from it. Early in his book, he reconstructs or invents the funeral oration spoken by the Athenian leader Pericles to commemorate those who died in the first year of the Peloponnesian War, with its brilliantly inspiring praise of Athenian democracy in its full flower, prospering and triumphant through its voluntary self-control, its mutual responsibility, its reverence for the law.

https://getpocket.com/explore/item/what-thucydides-knew-about-the-us-today?utm_source=pocket-newtab

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

me hammering on ab’s door in washington dc: hi. hi. hi i know you’re social distancing but i have to know. does les miserables qualify as an encyclopedic novel as per edward mendelson’s definition? i won’t be mad if you say no! i just want to know why!

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I've read in 2019

I forgot to do a monthly overview so here's my read books of the year by genres

Anthology

Proud - Ed. Juno Dawson (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Non-binary Lives: An Anthology of Intersecting Identities - Ed. Jos Twist, Ben Vincent, Meg-John Baker, Kat Gupta (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Classics

The Epic of Gilgamesh - Anonymous (⭐⭐⭐)

Fantomina - Eliza Haywood (⭐⭐)

Things Fall Apart - Chinua Achebe (reread)

Frankenstein - Mary Shelley (⭐⭐⭐+1/2)

Northanger Abbey - Jane Austen (⭐⭐⭐)

Much Ado About Nothing - William Shakespeare (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

A Christmas Carol - Charles Dickens (⭐⭐⭐)

Crime

Death on the Nile - Agatha Christie (⭐⭐)

Comics/Graphic Novels

Vida y Muerte de Federico García Lorca - Ian Gibson, Quique Palomo (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Through the Woods - Emily Carroll (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Spider-Gwen - various (several issues)

Daredevil - various (several issues)

Ghosbusters - various (several issues)

Essays

Africa's Tarnished Name - Chinua Achebe (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

No One Is Too Small To Make A Difference - Greta Thunberg (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Fantasy

A Wizard of Earthsea - Ursula K. Le Guin (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Name of the Wind - Patrick Rothfuss (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Wise Man's Fear - Patrick Rothfuss (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Good Omens (2x) - Terry Pratchett, Neil Gaiman (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Ocean at the end of the lane - Neil Gaiman (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Dark Days Deceit - Alison Goodman (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Hobbit - JRR Tolkien (⭐⭐⭐)

Wayward Son - Rainbow Rowell (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Fiction

The Rules of Seeing - Joe Heap (⭐⭐⭐)

Purple Hibiscus - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (⭐⭐⭐)

Wide Sargasso Sea - Jean Rhys (⭐⭐)

Crooked Hallelujah - Kelli Jo Ford (⭐⭐⭐)

Horror

Elevation - Stephen King (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

It - Stephen King (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Humour

Die Känguru Apokryphen - Marc-Uwe Kling (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Middle Grade

How to look for a lost dog - Ann M. Martin (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Dragon's Green - Scarlett Thomas (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Chosen Ones - Scarlett Thomas (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Call me Alastair - Cory Leonardo (⭐⭐⭐)

Matilda - Roald Dahl (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Mythology

9 from the 9 worlds - Rick Riordan (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Aru Shah and the end of time - Roshani Chokshi (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Aru Shah and the Song of Death - Roshani Chokshi (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Circe - Madeline Miller (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Norse Mythology - Neil Gaiman (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Warriors, Witches, Women: Mythology's Fiercest Females - Kate Hodges (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Non-fiction

The Moor's Last Stand - Elizabeth Drayson (⭐⭐)

Lingo - Gaston Dorren (⭐⭐⭐+1/2)

Every Word is a Bird we teach to sing - Daniel Tammet (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Trans and Autistic - Noah Adams, Bridget Liang (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Spectrum Girl's Survival Guide - Siena Castellon (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Queer Heroes: Meet 53 LGBTQ Heroes from Past and Present - Arabelle Sicardi, Sarah Tanat-Jones (⭐⭐⭐+1/2)

What's Your Pronoun: Beyond He & She - Dennis Baron (⭐⭐⭐+1/2)

Novella

The Only Harmless Great Thing - Brooke Bolander (⭐⭐)

As Kismet would have it - Sandhya Menon (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Poetry

Selected Poems - WH Auden, Ed. Edward Mendelson (⭐⭐⭐)

Tell me the truth about love - WH Auden (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Sacrament of Bodies - Romeo Oriogun (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Romance

Ayesha At Last - Uzma Jalaluddin (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Sci-fi

Space Opera - Catherynne M. Valente (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

WWW: Wake - Robert J Sawyer (⭐⭐)

WWW: Watch - Robert J Sawyer (⭐⭐⭐)

WWW: Wonder - Robert J Sawyer (⭐⭐+1/2)

Archenemies - Marissa Meyer (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Supernova - Marissa Meyer (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

Travel

Spiritual Places - Sarah Baxter (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

YA

The Love & Lies of Rukhsana Ali - Sabina Khan (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

You Asked for Perfect - Laura Silverman (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

When Dimple met Rishi - Sandhya Menon (⭐⭐⭐⭐)

There's Something About Sweetie - Sandhya Menon (⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐)

The Bird and the Blade - Megan Bannen (⭐⭐⭐+1/2)

9 notes

·

View notes