#especially when han and bon are dating

Text

jurassic park // june gloom

stand atlantic hot milk

#these song parallels just get better and better#especially when han and bon are dating#stand atlantic#hot milk#bonnie fraser#david potter#jonno panichi#miki rich#hannah mee#jim shaw#hardy deller#tom paton#pop punk#music#lyrics#lyric parallels

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Usual Shows I am Watching List

For the next week or so at least (obviously, I am unlikely to watch every single one on the list, but they are all in the running; it’s like a preview for posts I am likely to make).

The Abyss (Korea) - I am a few eps behind and, frankly, the drama about two dead people brought back into different bodies, hunting a serial killer and finding love, should be more engaging and smarter than it is, but it’s a pleasant easy watch and I am very fond of the two leads.

Angel’s Last Mission (Korea) - I am only two eps in, but the gorgeous intensity reminds me of old-school kdrama melos that I love so much. A bitter blind ballerina and an angel who is supposed to help her find love but falls for her instead is probably doomed for disaster in terms of happy ending, but I will be eating up all the pain!

Arthdal Chronicles (Korea) - grim (but not too grim) cool and otherwordly fantasy. I still don’t care for any characters, but the drama itself is great to watch.

Cage of Love (China) - surprisingly, not a BDSM tale. Hawick Lau wears amazing outfits and seeks revenge while trying to clear himself from being framed on a regular basis and dealing with heroine who sometimes loves him and sometimes thinks he is the resident serial killer. I started it years ago and now feel like continuing.

The Crowned Clown (Korea) - I need a sageuk in my life and watching Yeo Jin Gu in the pretty inferior Absolute Boyfriend made me remember how impressed I was by him playing both a psycho king and a sweet acrobat doppleganger who replaces him, so I restarted it.

Good Omens (UK) - loved the book when I read it a gazillion years ago and the first ep was good!

Heart of Stone/Hua Jai Sila (Thailand) - basically a 1980s romance crack about a pimp who comes back for revenge on his stepmom and falls for his childhood friend, this is insane! But addictive! Also make-outs!

Here to Heart (China) - it’s on my list and I may or may not get to it. I like the angsty premise and credits (they used to be lovers until she broke his heart in what I am sure is either a misunderstanding or noble idiocy), now he is mega rich and she is hired as his assistant, but Zhang Han has never clicked with me for some reason. He’s good-looking, he’s an OK actor, but for whatever reason he just doesn’t have that “it” for me. Maybe this drama will change that.

Just Between Lovers (Korea) - when it was airing and people were falling madly in love with it, I was in a kdrama slump that no kdrama could cure. But now - oh, this is so achingly, perfectly, emotionally gorgeous. Only one ep in, but I already know this will be a keeper.

Kimse Bilmez (Turkey) - the one Turkish entry on this list! Starts on Tuesday, promises angst, women in danger, macho traditional men who defend them blah blah blah. As a modern feminist, I should probably be appalled, but I like what I like and gimme gimme gimme!

Le Coup de Foudre (China) - I just want to see the aristocrat daughter and the hot constable from An Oriental Odyssey be an OTP, all right?

Legend of Fuyao (China) - am on ep 22 I think. It’s pretty and shippy and I won’t stay awake freaking out about characters or plot twists, but watching Ethan Ruan worship the ground Yang Mi walks on never gets old.

Legend of the Phoenix (China) - on ep 4! Get subbed quicker for my sanity, pls. Love story, scheming courtiers, angst, period costumes. What more does a girl need? Jeremy Tsui looking scrumptious, apparently.

The Legends (China) - finally hit ep 20! I like it and it’s a relaxing, fun, cute watch. Though if Zhao Yao figures out Demon Boy likes her before at least a dozen eps pass, despite him doing everything but carving “I love Zhao Yao” into his chest, I would faint from shock.

Letting You Float Like a Dream (China) - I am excited Young Lord from Minglan gets to be the hero of his own story and get the girl he wants (even if he has to reincarnate a couple of times first), plus look cool in 1930s duds. This is very much my thing.

Likit Ruk/The Crown Princess (Thailand) - sometimes a lady just wants to watch a good, old-fashioned princess x bodyguard romance, especially when said princess and bodyguard are hot enough to set the Chao Praya river on fire.

Listening Snow Tower (China) - on ep 38 now. Gorgeous visuals, awesome fights, and the Victorian duality of the chaste and almost unspoken but frighteningly intense romance is so my jam. But if they kill the hero, I will riot. Let him and Lady Badass wuxia into sunset together, pls.

My Absolute Boyfriend (Korea) - I am all up to date with this one. Which is weird because I am not up to date on other dramas I like more. This is a giant meh emotionally, and wastes some really good actors, but it is so good-naturedly unoffensive, I can’t even complain. Still, perhaps the story of a lady buying a lovebot should have stayed solely in manga form because I’ve never seen an amazing adaptation of it.

Pretty Man (China) - I liked the first ep, and you have no idea how rare it is for me to say that about a contemporary cdrama. Childhood loves who find second chances yes pls.

Princess Silver (China) - Yuu Watase, is that you? Did you write this? Cracky, not too serious, but seriously addictive, this is a chocolate bon bon in drama form. PS Pls cure the prince of his touch phobia through LOTS of skinship, princess!

Siege in Fog (China) - romantic dysfunction reigns supreme, even more so than gorgeous 1930s outfits and people. Elvis Han and Sun Yi boil my blood in amazingly pleasant ways as two people in a marriage of inconvenience, where he pines for her but won’t show it and she loves another, until she wakes up and realizes that HELLO IT’S SEX ON LEGS ELVIS, I NEED TO GET SOME OF THAT! And the civil war says, “not so fast!”

Too Late To Say I Love You (China) - I started it years ago when it was not fully subbed and loved it because in my secret heart-of-hearts, I too want a mega hot warlord who looks like Wallace Chung and has stylish 1930s cars and a private army to sweep me off my feet and obsess over me in an unhealthy but hormonally incredible fashion as if I am the only woman in the world. SiF reminded me of this so here we are.

Tried and dropped:

The Plough Department of Song Dynasty (China) - watched one episode, felt my brain leaking out of my ears and bailed. Granted, I watch plenty of dumb stuff so far be it from me to act high and mighty about a bit of brainless fun, but I don’t like mysteries, there was no angst, and I couldn’t care less if all the characters fell into a giant pit, so here we go...

Well Intended Love (China) - people didn’t like it because the male lead was a sociopath. I didn’t like it because it was cutesy and boring and nobody in it bothered to act (or couldn’t.) I bailed long before the dysfunction, that’s how bored I was.

#cdrama#kdrama#lakorn#too late to say i love you#siege in fog#arthdal chronicles#the abyss#my absolute boyfriend#absolute boyfriend#the plough department of song dynasty#well intended love#the legend of fuyao#legend of fuyao#legend of the phoenix#the legends#angel's last mission: love#angel's last mission#princess silver#listening snow tower#snow tower#pretty man#le coup de foudre#here to heart#likit ruk#hua jai sila#the crown princess#letting you float like a dream#heart of stone#cage of love#kimse bilmiz

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye 2019. Hello 2020.

To celebrate the new year - which a lot of people are celebrating right now, I’m sure, unfortunately not me yet - I decided to create this post. I don’t know how to explain it but if you like kpop, keep reading!

My Top 3 Songs of 2019

1. SKZ - Miroh

This song got me into my now ult group, Stray Kids. Those 9 boys have honestly made this year 10x better for me. Chan’s VLives definitely helped me when I was upset, and the members made me feel emotions by their side. I’m so glad that add of Miroh appeared and I chose to watch it because I may have not gotten into Stray Kids without it.

2. ATEEZ - Wave

Again, another song that got me into the group. I heard the song in a video where they played huge jenga at Kcon... I think? Anyways, this song is another banger and you completely fall in love with it first listen. You won’t regret listening to this.

3. TWICE - Fancy

I got into TWICE when they released YES OR YES, but FANCY is the song that you can’t not fall in love with. I did on my 2nd listen and man, if you’re saying you didn’t learn the dance and bopped to this song, you are LYING because- let’s be honest - everyone said FANCY SOTY.

Groups I began stanning in 2019 its felt like forever tho

Stray Kids - March 26th. You think I would forget?

ATEEZ - August 18th. Another date I remember, because I spent a good 2 hours getting to memorize the members name and faces. Was so happy when I finally did it.

iKON - Honestly, I was more of a Double B stan since January until Hanbin left. I loved their songs but I never got to know the rest of the members, except for Jinhwan.

ChungHa - Snapping dragged me in. That’s all I gotta say. Although, ngl, Gotta Go was something I always tried to dance to.

KARD - Again, Bomb Bomb just pulled me into the fandom. The rest of their discography made me stay. I sang along to Bomb Bomb everyday for a good 3 months. It was honestly EVERYTHING to me and then Dumb Litty came and stole my heart and KARD did it AGAIN.

Mamamoo - gogobebe. Do I really need to say anything else?

GOT7 - I’m pretty sure I got into them because, well everyone knows GOT7. They’re a name everyone knows if you like kpop, so I just wanted to get into them. Eclipse and You Calling My Name are songs I’ll dance and singalong to in the right mood and right part of the song. But their personalities dragged me in. I’m pretty sure BamBam also attracted me when he was on Stray Kids reality show.

Day6 - Time Of Our Life. I decided to listen to it because Seungmin of Stray Kids was a big fan of them and I was like, it shouldn’t hurt to try. Seungmin made me want to watch and Day6 made me want to stay. They don’t make ANY bad songs.

Everglow - March 18. Listened to Bon Bon Chocolat when it came out, and I was honestly scared ppl were gonna sleep on them cause ITZY debuted a month before. Fortunately, everyone noticed their talent.

BigBang - I dunno just listened to one of their songs. And, of course, I fell in love. Too late to stan them while they were active, but I’m expecting something in 2020... just saaying.

NCT - All of the subunits. Honestly there were so many of them, I spent time taking tests to tell them apart. The struggle to stan these boys. Instantly fell in with the Dreamies. And then I found out they weren’t a fixed unit... My heart shattered. It’s still breaking because 4 OF THEM ARE LEAVING. or left. I dunno.

Tomorrow by Together - They were probably the most anticipated group of this year. I remember ppl hyping them up in October of 2018! Predebut stan right here. (I just remembered that I thought the preview of each member was coming out in age order and thinking that Beomgyu was the youngest. And I was just like WHERE IS HEUNINGKAI FROM?!?!)

ITZY - remember when everyone thought that itzy’s debut was rushed because info about them was leaked. yeah, i forgot too. anyways, again I was a predebut stan.

(G)- idle - i always listened to their title tracks and I began stanning them during Queendom after their Fire cover im listening to 2ne1 2015 mama fire performance rn lol.... omg bom’s han cover just started playing. spotify is watching me guys.

Somi - Birthday was a bop. fight me. outfits sucked, gotta agree with that opinion I didn’t rlly know much about IOI but I started stanning because Jenchu were fangirling to it i mean jennie twerked for it!

Jimin Park - I’m out here still streaming STAY BEAUTIFUL. honestly she’s so loveable. her personality and her voice are everything. how can you not like her

My Top 5 Groups of the Year

1. STRAY KIDS - A lot of the reasons I luv them are the same as ATEEZ. That’s why ateez are close to being my number one, but honestly these 9 boys are everything to me. 9 or NONE FOREVER. They have been through so much this year and I hope they STAY strong for 2020. In their 2020 seasons greeting they announced a full album next year, so I’m ready to follow these boys on their journey no matter how many stay or leave. I’m a STAY for a reason.

2. ATEEZ - PERSONALITY. I’m also a sucker for groups that shove their love for each other in your face. 8 makes 1 team, y’know? Hongjoong and Mingi are amazing rappers, Jongho, Wooyoung and San’s vocals tho, Yunho and Seonghwa’s deep voices are the death of me, and Yeosang dancing. They’re talented and luvable and that’s all I need for an ult group. also all their songs are bops

3. Mamamoo - Honestly would’ve tied with Twice but these I’m a sucker for them as ppl as well, and I need that to luv a group. they ain’t fake, they slap information in your face and they are POWERFUL WOMAN. (Not saying twice aren’t ofcourse) And these girls vocals are on POINT. Moonbyul is rapper material, but have you heard the girl song? What an angel. Their songs are all slaps, especially the most recent ones.

4. TWICE - This was their year? yes or yes. Fancy soty. Feel Special was a great title track, don’t get me wrong, bUT HAVE YOU HEARD THE FULL ALBUM. Every song is my AMAZING. omg rainbow is playing

5. NCT DREAM - These boys stole my heart, I only stanned nct because of them. Honestly seeing the 00 line leave breaks my heart.

My Top 5 girl group and boy group songs

gg songs were honestly so hard to pick, they thrived and SO many good songs were made in 2019. But here is my list.

1. Fancy - soty

2. Hip - this song was everything from the choreo to the song itself to the girls energy performing it

3. Psycho - came out like last week but it’s in everyone's top 10 of this year. Beautiful song that won’t get outta my head. getwellsoonwendy.

4.Violeta - this is another song that won’t get out of my head. honestly none of these songs will. ok so the final dance part after the drop of violeta pisses me off because the dance could is so powerful and that part comes and it’s such a disappointment but it’s the only part I can do so i shouldn't complain but the song itself is very catchy. I don’t want these girls to disband even if the votes were rigged because they make a good group and sing bangers. i don't want them to leeeave.

5.Lion - the song is just so powerful. other songs they’ve made are good, but the chorus is usually a disappointment because the pre chorus is so good but EVERYTHING is great about Lion. Didn’t like it at first for some reason, i dunno why, but once you give it a few more listens you’ll fall in love.

Now onto the boy groups. They made quite a few bangers this year as well.

1. Miroh - It’s my no.1 of the year. watchu expect?

2. Wave - and this is my no.2. Again, what else would I put here?

3. Run Away - what. a. bop. still can’t get out of my head. Crown was a disappointment to me after 1000 listens but not Run Away. A bonus is the Harry Potter references. With that I just was head over heels in love. Txt didn’t fail to disappoint with their comeback even if it was pushed back.

4. Boom - This song made me fall in love with the talent that NCT DREAM holds despite being so young. Sang along for a few months. Actually, it’s still in my head.

5. Make It Right - I was doing title tracks for all these but then I realised there has to be an exception because I just really like this song, especially the one featuring Lauv. Boy with luv wasn’t it for me but every other song on Persona is a straight up masterpiece (ok an exaggeration but u get what i mean)

Now onto the soloists (they’re all female, sry not sry)

1. Chica - I was debating whether to put Snapping or this but decided with Chica. Honestly the vocals, the song, the dance, the MESSAGE, is everything. I love it, it empowers woman, it makes ME feel good, and it’s what some people really need sometimes. So, thank you ChungHa.

2. Gotta Go - another bop by our queen ChungHa, she really ruled this year. I didn’t stan her when it came out but that doesn’t mean I didn’t do the ‘deulshi’ part whenever I heard it. iconic.

3. Twit - Again another iconic bop from this year. (i thought this masterpiece came out last year, i dunno why but it just is so 2018 for some reason? I dunno) Hwasa’s solo debut really was everything. So was Moonbyul’s which unfortunately didn't make it on the list but I would say it’s in between 5th to 7th for me.

4. Stay Beautiful - Such a beautiful song, it was a shame Jamie had to leave but she left JYP saying that they lost smth PRECIOUS and they would regret it and she conveyed all that in one song without hinting at it. So many quote worthy lyrics were in the song and it just bring up my mood and my standard for vocals. Don’t sleep on this girl, y’all.

5. Birthday - the song brought out mixed reactions from everyone but i LOVED IT. It did get a bit old but it’s still something you’ll find me singing along to every now and then.

ARTISTS THAT STOOD OUT TO ME THIS YEAR

1. Bang Chan of Stray Kids. I love him. He’s such a great leader, he’s a loveable person, he’s all rounded and he fucks up sometimes but he acknowledges it and fixes it. He went through so much shit this year and he deserves so much more. I, along with many other STAYs are gonna make 2020 a better year for him and all of his group. Stay strong Chan! But besides his personality his stage presence, his rapping, his singing, his producing, his energy, his personality, it all made him someone who was always on my mind.

2. Yeonjun of Tomorrow x Together. He’s also very well rounded and he really stands out to me from all the other 4th gens. Whenever I see a performance by TXT he always grabs my attention even when he’s not the main focus. I love his dancing, it’s very eye catching to me, along with his stage presence. He never loses his energy on stage and I expect a lot from him in 2020! His rapping and singing are amazing as well, especially for a rookie. Also when they first debuted he cried a lot, which was very heartwarming to me because idols showing emotion other than happy is something I appreciate, because it lets me remember they’re human too.

3. Seulgi of Red Velvet. She’s, again, very well rounded. I’m not really a Reveluv, but Wendy and Seulgi are vocalists who really stand out to me so those to kind of make me want to listen to Red Velvet’s songs. She’s an amazing vocalist, like words can’t express how much a love this woman's voice. Her stage presence is amazing as well, she’s just a really good performer imo.

4. Jihyo and Nayeon of TWICE. First of all I really like their personality and how powerful they are. Honestly a wink from them and I’m falling of my chair. Secondly, I don’t know if anyone's noticed but I really like powerful female vocals, and these two have extremely POWERFUL vocals. Have you heard them sing? Just... POWERFUL, that’s all I can really say to describe their voices.

5. Mingi and Hongjoong of ATEEZ. They are rapper that are gonna blow away the whole industry with 3racha, I mean they already have. Did y’all see their performance in MAMA. The RAWEST vocals I heard that whole show. They were obviously not lip syncing, you could hear Mingi panting and he didn’t rap a whole line, and I LOVE that because it is RAW and we need more raw vocals or atleast breaths heard when the artists are dancing because it makes the performance more REAL. also stage presence is amazing from these two, they really know how to hype up a crowd.

ROOKIE GROUPS I EXPECT A LOT FROM NEXT YEAR

sorry my expectations are high for them, but they have stood out tome so much and i couldn’t stand to see them flop.

1. TOMORROW X TOGETHER - they’ve been on this list quite a lot, and I really appreciate their individual talents along with them as a group. I REALLY want to see them improve and grow more next year because they were really pushed this year, being BTS’s juniors. I’m sure they were really stressed but I want them to become TOMORROW BY TOGETHER not BTS’s juniors. Probably won’t happen in a year but hopefully in the next decade.

2. ITZY - another group really known for theing the juniors of TWICE this time. The title tracks they released so far have all been listen to it the first time, you don;t like it, but listen to it the 2nd time and it’s stuck in your head for the next 7 months. Honestly if they keep going like this, it would be like a ITZY thing, and I honestly wouldn’t mind.

3. EVERGLOW - i think everyone just saw bon bon chocolat, gave it a listen, and loved it. but i also heard it was produced by someone who helped produce Crown by TXT and Spring Day by BTS, so there’s another reason ppl may have liked it so much. Adios wasn’t a disappointment at all. Of course, I would also love it if Everglow kept up the “nanana” thing in each of their title tracks.

4. ATEEZ - I don’t think they’ll flop at all next year. I know they just had their 1st year anniversary, but I wouldn’t mind a full album... either way, Imma stick with them because they’ve only released that good shit so far and I’m honestly expecting a somewhat mediocre song at least once in their career next year. Not expecting it though.

5. ONEUS - I haven’t’t talked about them yet but all of oneus’s title tracks are absolute gold. I am a mess for Valkyrie, Twilight AND Lit. They’re all just AMAZING songs. I mean, what did we expect from Mamamoo’s juniors but. They are REALLY good. Just go listen to all their title tracks rn.

And finally, wishes for 2020

- Of course, Wendy to recover after her tragic incident at SBS. Again, I hope she recovers well

- Mina to come back from her hiatus, only if she’s ready to, of course

- BLACKPINK FULL ALBUM. ROSE SOLO. PLEASE.

- Of course, 4th gen to thrive along with 3rd gen and 2nd gen groups

- A full album from stray kids (which was confirmed) and again, maybe for ATEEZ? just maybe?

- More attention for Mamamoo. They are underrated queens.

- Less hate for Tomorrow By Together. People bash them just because they’re BTS’s juniors. they would be praised a less but definitely not doubted way more if they weren’t under Bighit. Yeah, they get luxuries other groups won’t but that doesn’t mean people should degrade them for it.

And with that

I wish everyone a Happy New Year. May your next decade be filled with happiness and joy! omg fancy started playing

also i didn’t have time to properly edit this. then again i am a rambling blog, so what are you expecting?

#kpop#twice#mamamoo#txt#bts#kpop 2020#ateez#everglow#itzy#oneus#jyp#kpop 4th gen#chung ha#somi#queen hwasa#jimin park#chica#snapping#gotta go#twit#stay beautiful#birthday#stray kids#got7#bang chan#choi yeonjun#kang seulgi#im nayeon#park jihyo#song mingi

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 2 (26): (1587) Third Month, Third Day, Midday.

26) Third Month, Third Day; Midday¹.

It was agreed that [only] kashi [would be served]².

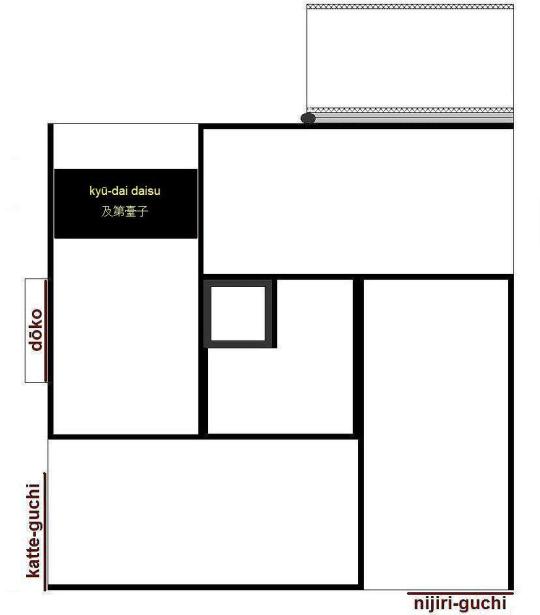

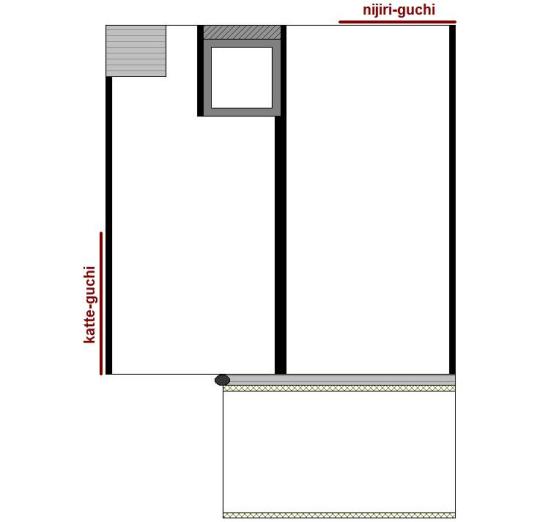

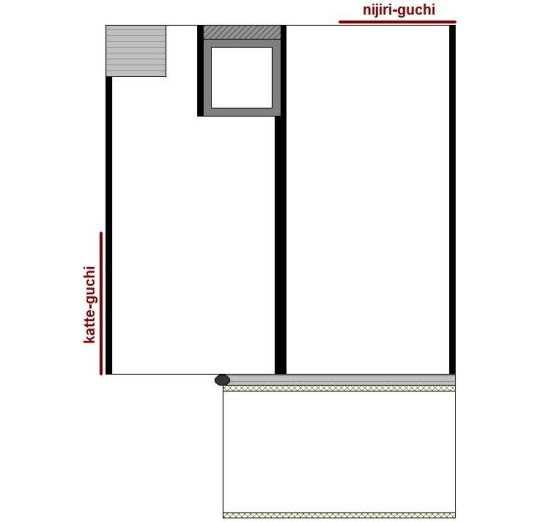

◦ 4.5-mat [room]³.

◦ [Guests:] Jōko [紹古]⁴, Sōkei [宗惠]⁵.

[Sho [初].]⁶

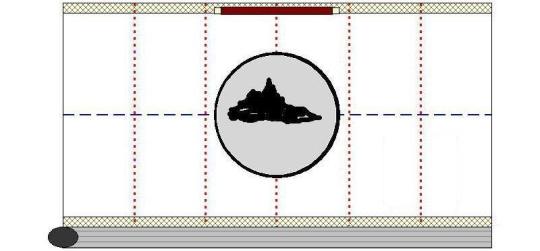

﹆ Shunkyo [舜擧]⁷, painting of peach[-blossoms]⁸.

◦ Bon-san [盆山] Kiji [紀路]⁹.

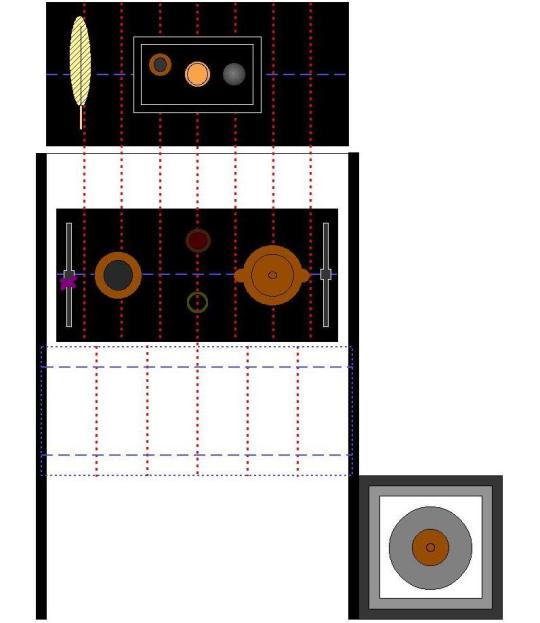

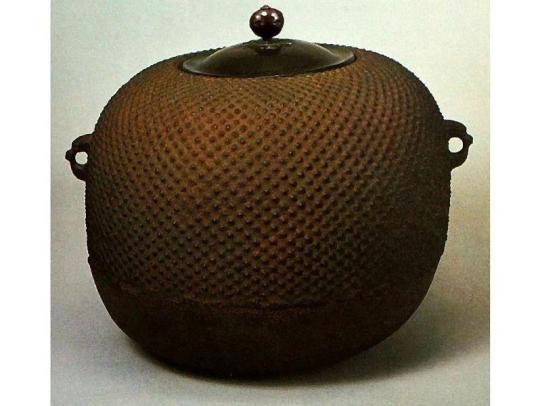

◦ Kiri-gama [桐釜], [suspended on the] small[-linked] chain¹⁰.

◦ On the kyū-dai [弓臺]¹¹:

below:

﹆ mizusashi mu-mon [水指 無紋]¹²;

﹆ momo-jiri [モヽ尻]¹³;

﹆ kuchi-boso [口細]¹⁴;

﹆ guru-guru [クル〰]¹⁵;

◦ fukusa [服サ]¹⁶;

above:

◦ On a kō-bon [香盆]¹⁷: kōro Usu-gumo [香爐 薄雲]¹⁸, kōgō futae ao-gai [香合 二重青貝]¹⁹, kyōji-tate [キヤウシ立]²⁰;

◦ Habōki [羽帚]²¹.

After the kōro was passed around, a set of charcoal [was laid in the ro]²².

▵ Sakemono ju-ju [サケ物重〻]²³.

▵ Yomogi no mochi [ヨモキノモチ]²⁴.

▵ Nimono [煮物] tori ・ kushi-awabi ・ shiitake ・ mame ・ musubi-me [鳥 ・ 串アハヒ ・ 椎茸 ・ マメ ・ ムスヒメ]²⁵.

▵ Mizu-kuri [水栗]²⁶.

▵ Sake, two rounds.

Go [後]²⁷.

◦ The toko [was left] as it was.

◦ Kyū-dai [弓臺]:

below:

◦ as it was;

above:

﹆ chaire sasa-mimi [茶入 サヽ耳]²⁸;

◦ on a naka-bon [中盆]²⁹: natsume ・ kasane-chawan ・ ori-tame [ナツメ ・ カサネ茶碗 ・ 折タメ]³⁰.

_________________________

¹San-gatsu mikka, hiru [三月三日、晝].

The Gregorian date of this chakai was April 10, 1587. It was thus nearly high spring, and the earliest of the cherry blossoms would have been getting ready to open.

The occasion for this chakai was the Momo-no-seku [桃の節句], or peach-blossom festival (hence the kakemono). The occasion was also known as the Hina-matsuri [雛祭り], because on this day the girls of the household displayed their collection of hina-ningyō [雛人形] -- small dolls that were dressed and arranged to reproduce the scene of the Imperial court.

Because the morning was occupied with inspecting the dolls (many of which were precious antiques -- especially in the households of the wealthy machi-shū), and partaking of a morning meal replete with festive delicacies, Rikyū and his guests agreed beforehand to limit the food served during this chakai to kashi only (according to his notation).

Rikyū uses an impressive set of utensils, but his focus seems to be on the Peach Festival aspect of the day.

²Kashi ni te, yakusoku [菓子ニて、約束].

That is, he arranged with the guests beforehand that he would only serve kashi. (Though the selection of kashi actually seems at least as substantial as many of his fuller kaiseki -- probably to give the kama time to return to a boil after a new set of charcoal had been added to the fire, while making it clear that the limitation to kashi only was not a sign of parsimony.)

This gathering is what is now called a kashi-chaji [菓子茶事]. Whether it was also an impromptu chakai (as Shibayama Fugen suggests) cannot be known -- Rikyū does not mention when the agreement over the kashi was made -- though the rather large number of different kinds of kashi (most of which were cooked, and some of which required several hours of preparation time) served, along with the special utensils that Rikyū used, argues against this.

³Yojō-han [四疊半].

This was the 4.5-mat room in Rikyū's residence.

He is still in Sakai.

⁴Jōko [紹古].

Nothing is known about this person*.

That said, however, it is important to point out that both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō give a different name: Jōsa [紹佐]†.

Jōsa [紹佐] would refer to the man known as Abura-ya Jōsa [油屋紹佐], the wealthy Sakai machi-shū and chajin who appears to have been a disciple of Jōō. Some scholars identify this person with the man who affected the (Japanese-style) name Date Jōyū [伊達常祐; ? ~ 1579] -- though, given the fact that the present gathering took place in 1587, this could not be him. Perhaps Jōsa was Jōyū’s son‡. The wealthy Abura-ya [油屋] firm, which dealt in oils, was headquartered in Sakai.

At any rate, in addition to his being mentioned several times as a guest in Rikyū's several kaiki, Jōsa is also said to have been closely connected to Kokei oshō -- and presented the monk with thirty strings of coins** for expenses when Kokei moved from Sakai to the Daitoku-ji in Kyōto.

__________

*This name is found only in the Enkaku-ji version of Book Two of the Nampō Roku (and in Kumakura Isao's modern Japanese rendering, which more or less follows the Enkaku-ji text).

Neither Hisamatsu Shin-ichi (the editor of the Sadō Koten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集] edition of the Enkaku-ji text), nor Kumakura Isao, do any more than list this name without comment.

The fact that the other manuscripts generally agree on a different name (as has been mentioned before, Tanaka Senshō had access to Jitsuzan's original notes -- the same notes from which Jitsuzan himself copied) suggests that Tachibana Jitsuzan may have made a mistake when he transcribed this kaiki from his notes into the notebook that he was preparing for presentation to the Enkaku-ji.

†Tanaka Senshō also includes a note suggesting that some other copies give the name as Jōrin [紹林] -- though he seems to feel that this is not credible.

Jōrin [紹林] would refer to Tateishi Jōrin [立石紹林; his dates of birth and death unknown], another machi-shū chajin from Sakai, who had apparently studied chanoyu with Jōō (as attested to by his name). Jōrin was a guest at chakai that Rikyū gave on the 25th of the Second Month, the 26th day of the Twelfth Month of the previous year; and he is also mentioned as having introduced Maruyama Bansetsu [丸山晩雪] to Rikyū (Bansetsu was entertained by Rikyū on the 27th Day of the First Month), suggesting that Jōrin and Rikyū were close friends.

‡And so Jōsa would have assumed the name of Jōyū when he succeeded to the headship of the Abura-ya firm -- as was customary in many families during that period.

Jōyū certainly studied chanoyu from Jōō; but Jōsa is held, by certain scholars, to have been a disciple of Rikyū. This conundrum could be explained quite easily if the two were indeed father and son.

**“Zeni san-jū kanmon” [錢卅貫文]: 30,000 copper coins -- weighing some 112.5 kg.

⁵Sōkei [宗惠].

This was Mizuochi Sōkei [水落宗惠; his dates of birth and death are unknown], a respected machi-shū chajin from Sakai*. He is also said to have been the father of Rikyū's son-in-law, the man usually known as Sen no Jōji [千紹二]†.

Sōkei is mentioned as having been a guest at several other chakai that are recorded in Rikyū's kaiki (his most recent previous appearance having been on the 5th day of the Second Month, together with Kokei oshō and Nambō Sōkei‡), as well as in many other documents that have survived from this period.

__________

*Some suggest that he was also one of Rikyū's disciples (though it is more likely that he was a member of the group that formed around Rikyū in the years after Jōō’s death -- given Sōkei’s contemporary reputation as a chajin).

†He is usually known as Sen no Jōji because Rikyū adopted him into the Sen family upon his marriage to his daughter (a common enough practice at that time when a man had fathered few or no sons).

‡Implying that he may have been a member of their circle as well.

⁶Sho [初].

This notation, which means the shoza, is not found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript -- though both Tanaka Senshō's and Shibayama Fugen's manuscripts are so marked.

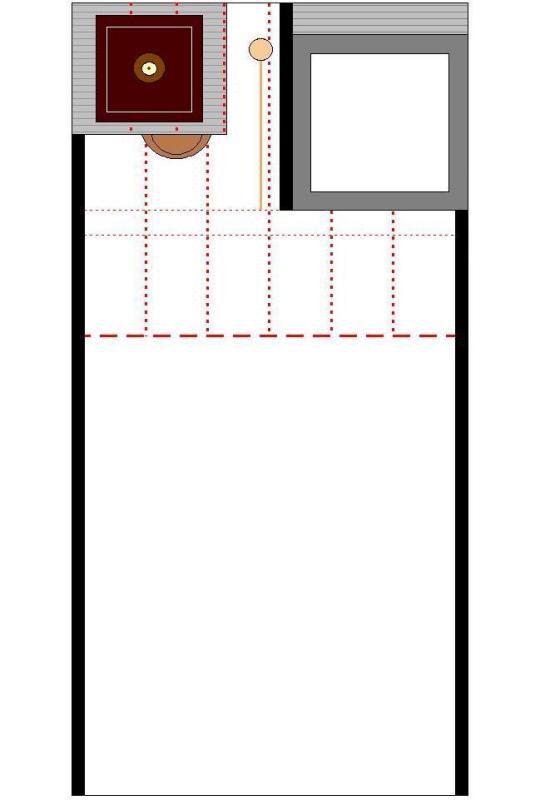

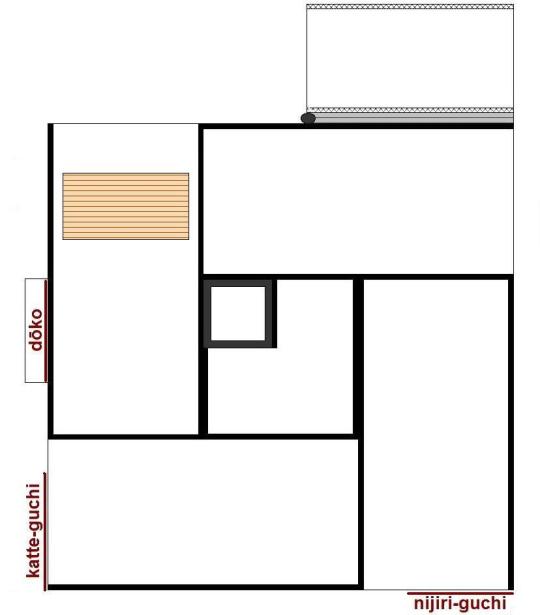

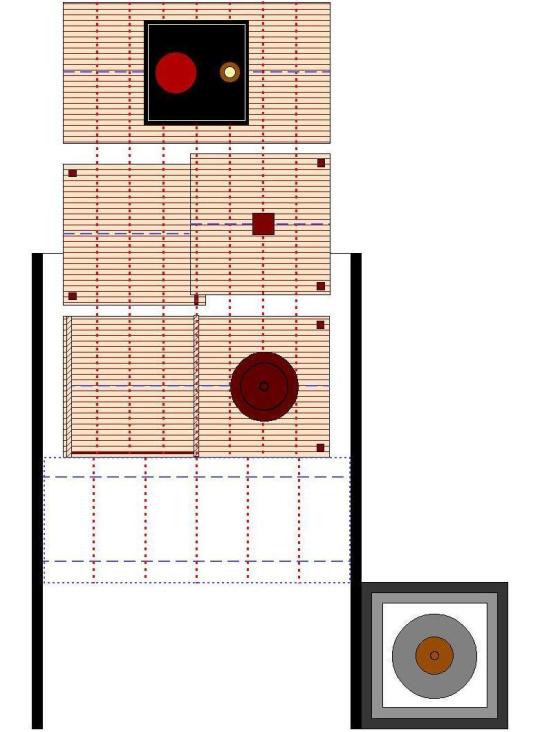

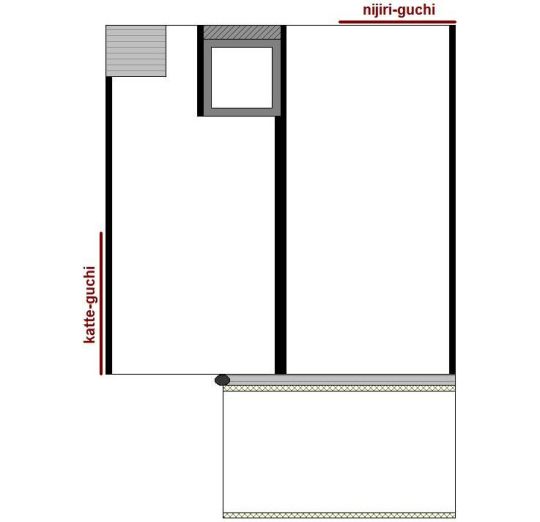

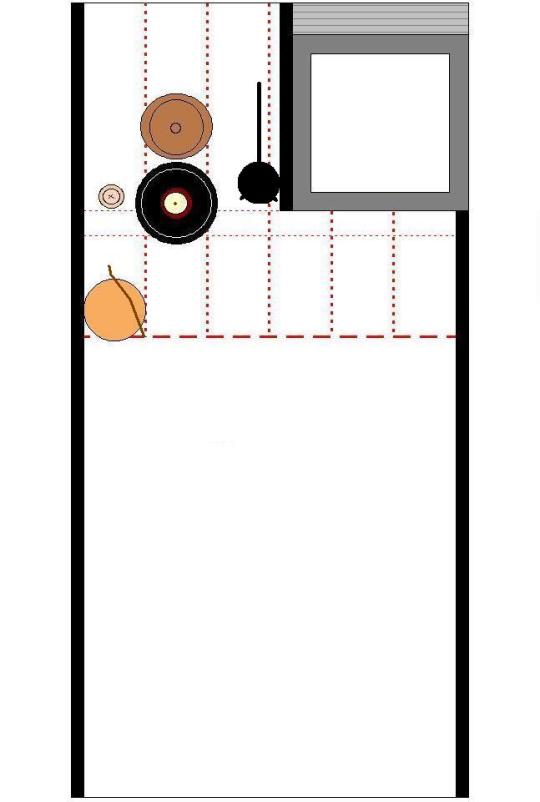

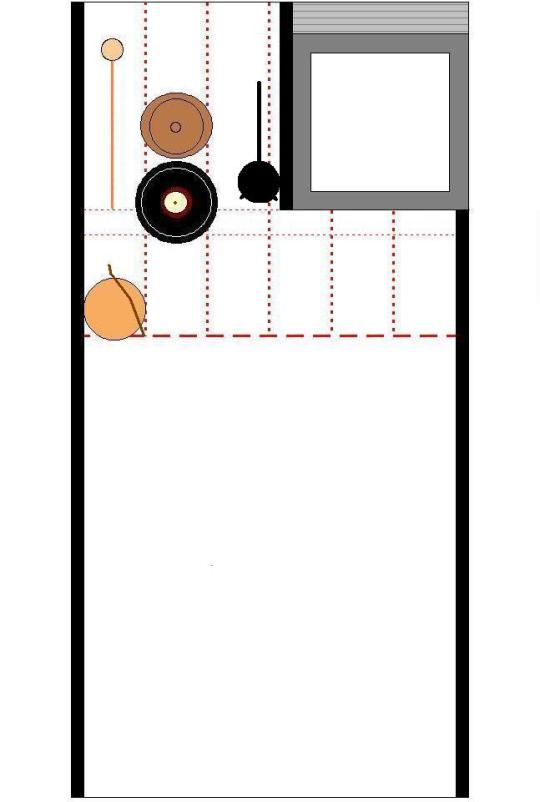

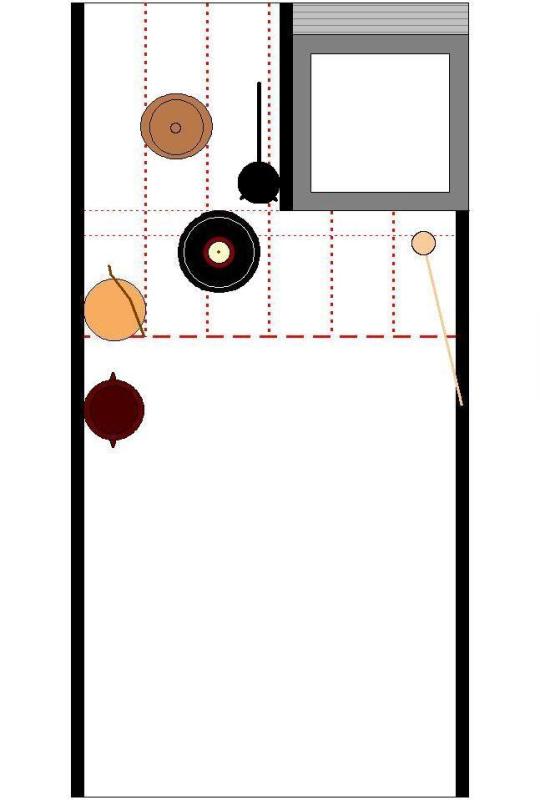

With respect to the kane-wari:

- the toko contained the kakemono, with a bon-san arranged on the floor in front of it, and so was chō [調];

- the room had the kama in the ro, meaning it was han [半];

- and as for the daisu, the kaigu were han [半] (because, while there were four objects, either the futaoki, or the koboshi, shared a kane with the shaku-tate), while the kō-bon and habōki on the ten-ita were chō [調] (each contacted yang-kane), giving a total of han [半] for the tana.

Chō + han + han is chō, which is appropriate for the shoza of a gathering held during the daytime.

⁷Shunkyo [舜擧].

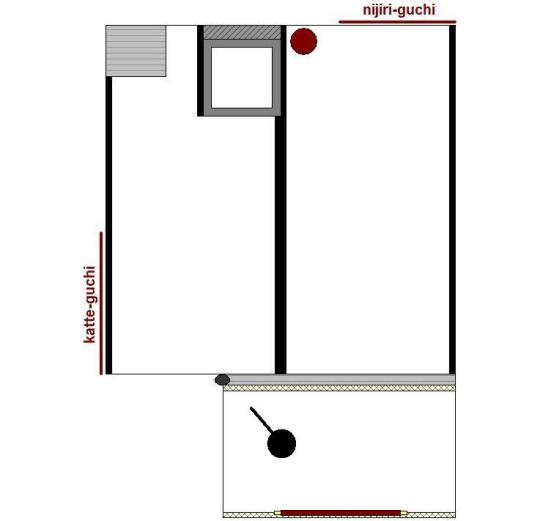

Shùn-jǔ [舜擧] is one of the names used by the Chinese painter Qián Xuǎn [錢選; 1235 ~ 1305], who is also known as Yù-tán [玉潭], and who was active from the late Song into the early Yuan dynasty.

It is said that, though Qián Xuǎn was trained as a scholar, he did not succeed in advancing in the Song officialdom satisfactorily; while the collapse of the regime followed by the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, lead to a refusal to consider aiding the new overlords out of a sense of loyalty to Song (and so, China).

After 1276 Qián Xuǎn devoted himself to painting, and became famous for his realistic depiction of various textures (“fur and feathers”), as well as depictions of natural subjects. His works frequently display a nationalistic inclination, and harp back to the works of the Tang and Song dynasties.

⁸Momo[-no-]e [桃繪].

Among Qián Xuǎn's surviving paintings is one that is known as “a broken-off branch of peach blossoms” (Zhézhī táo-huā [折枝桃花]), shown below, though it is not certain whether this was the painting displayed by Rikyū on this occasion or not.

This painting, nevertheless, well illustrates Qián Xuǎn's technique.

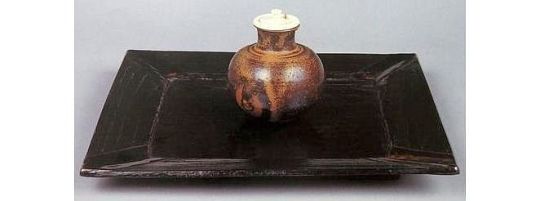

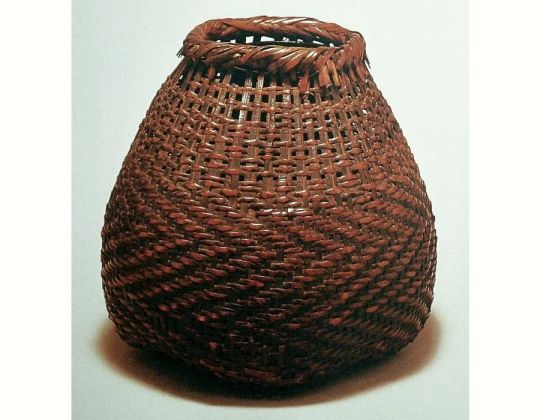

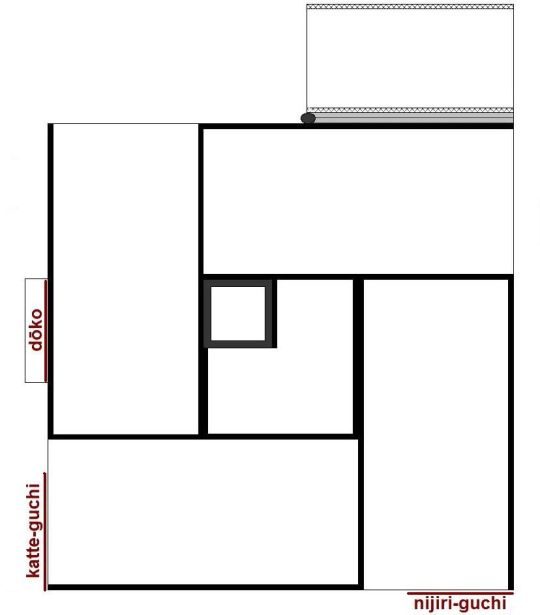

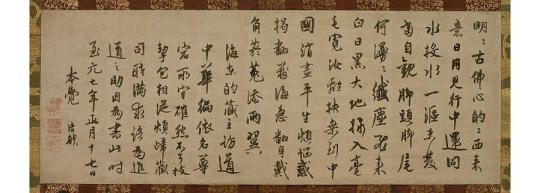

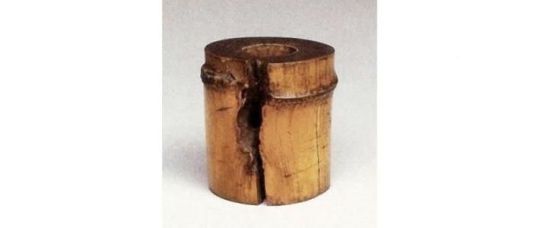

⁹Bon-san Kiji [盆山 紀路].

Kiji [紀路]* was the name of a famous bon-san [盆山]†. Below is a photograph of a different bon-san, known as Sue no matsu-yama [末ノ松山], which it may have resembled, arranged in the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] that was made for Ashikaga Yoshimasa by Haneda Gorō‡.

The Kiji viewing stone has never been located, if it still exists.

On this occasion it was displayed on the floor of the toko, in front of the scroll, as shown above.

__________

*This was the name of a road traversing the mountains, that was renowned for its scenic beauty, in the Province of Kii (Kii-no-kuni [紀伊の國]).

†Bon-san [盆山] means a mountain[-shaped stone] arranged in a tray. They are also known as bon-seki [盆石] (stones arranged on a tray), and sui-seki [水石] -- an abbreviation of the word sansui-seki [山水石], which means a landscape stone (that is, a stone whose shape evokes a landscape in miniature).

‡The original karamono naka maru-bon [中丸盆] was identical in size and shape to the tray seen in the photo. However, rather than being plain black lacquer, the Chinese tray had a brass plate (crafted to resemble a dragon) inlaid in the face, and a brass fuku-rin [覆輪] around the rim. While used for chanoyu (at the suggestion of the great dōbō [同朋] Nōami [能阿彌; 1397 ~ 1471]), the original tray seems to have been made for transporting hot dishes from the kitchens to the residential apartments (in China).

The original tray (along with the other five meibutsu trays) was lost when Yoshimasa's storehouse was destroyed by fire during the Ōnin wars.

In fact, many of these great treasures were originally mundane objects in their homelands; and their being esteemed in Japan suggests the lower technical level of native crafts, coupled with a fascination with the exotic.

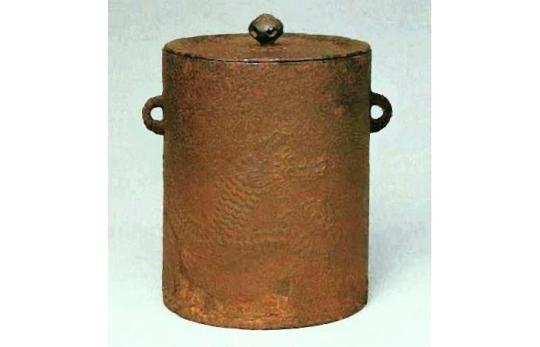

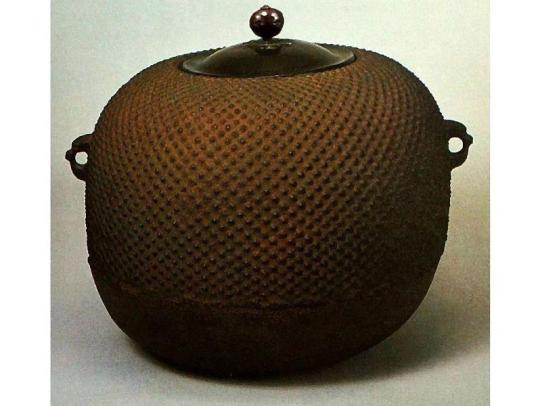

¹⁰Kiri-gama ko-kusari [桐釜 小クサリ].

This was the small kama, originally made for use with a small kimen-buro, that had formerly belonged to Jōō.

The kama was suspended over the ro on a chain with small links that has subsequently come to be known as Rikyū's azuki-kusari [小豆鎖].

This chain, along with Rikyū’s bronze tsuru and kan, is shown above.

¹¹Kyū-dai ni [弓臺ニ].

This refers to the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子].

The ten-ita of this daisu is 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu wide and 1-shaku 4-sun from front to back, while the ji-ita is 2-shaku 7-sun 5-bu wide and 1-shaku 3-sun deep. It, thus, can only be used in a room covered with kyōma-tatami and, because it has only two legs, it was originally not used with the furo (because the legs would interfere with the raising and lowering of the kimen-buro’s kan).

When arranged on the utensil mat, this daisu is placed 5-sun from the far end of the mat (rather than 4-sun 5-bu, as was the case with the shin-daisu), which means that there is 1-shaku 2-sun 5-bu between the upper corner of the ro and the front of the daisu. Consequently, the naka maru-bon [中丸盆] (which was 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter) was the largest tray that can be used with this daisu.

¹²Mizusashi mu-mon [水指 無紋].

This was Rikyū's bronze mizusashi with kimen kan-tsuki [鬼面鐶付].

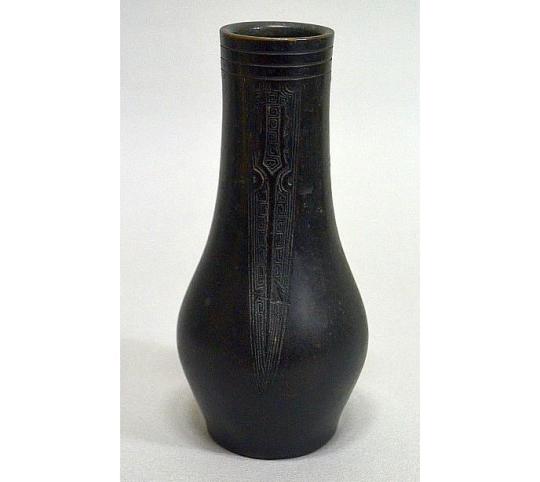

¹³Momo-jiri [モヽ尻].

This refers to the meibutsu hishaku-tate shown below.

Two kinds of momo-jiri shaku-tate are known from the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa: one with bas relief decoration (shown above), and one without decoration (i.e., “mu-mon” [無紋], like the mizusashi)*. It is not known which of them Rikyū owned.

__________

*These pieces were originally made in pairs, for use as flower vases that were placed on the family altar. As this was something that almost every Chinese family had in the main sitting room of their house, both sorts of momo-jiri were easily available on the continent.

¹⁴Kuchi-boso [口細].

This was Rikyū's narrow-mouthed mizu-koboshi.

¹⁵Guru-guru [クル〰].

This was a ceramic ya-gaku [夜學] futaoki, probably of dark green ceramic (rather than the celadon shown in the photo).

The name suggests that the piece was etched with a stylus to look as if string had been coiled around it (before the openings were cut out). It has not been identified.

¹⁶Fukusa [服サ].

This was an ordinary temae-fukusa [手前袱紗]*. The fukusa, whatever its size, was folded in half, and then it was folded into thirds, as shown below†.

The fukusa was then knotted around the left leg of the daisu‡.

__________

*That said, it is actually not known what sort of cloth Rikyū used for his fukusa. Jōō and the chajin of his generation used Chinese donsu, of a size determined by the native width of the cloth from which it was made (people bought an entire roll of cloth, and made fukusa by cutting a length that was twice the width, which, when stitched, resulted in a not-quite-square wiping cloth); while Furuta Sōshitsu (and the tea men who came after him) used Japanese silk that was dyed dark purple. While this fukusa was copied from the small furoshiki that Rikyū used to wrap natsume of gift tea (and was identical to these in both size and color), it is unclear whether Rikyū eventually imitated Oribe's lead by using these cloths as temae-fukusa or not -- since surviving reports are contradictory, and should be considered propaganda intended to support the Edo period conventions espoused by the Sen families rather than historically accurate information.

The fukusa was (and, even in the present, should be) used for only one temae, and then discarded. And since it was a personal item, apparently none of Rikyū's ended up in any of his admirers' hands, and so none have survived.

†As always, the wasa [輪差] (the folded edge) is on the right, and the fukusa is folded in half away from you. Then the right hand slides from the upper corner to the lower one, so the wasa is in front, and at the top. Then the fukusa is folded in thirds, starting from the top (like a chakin).

‡The fukusa is held horizontally behind the leg of the daisu (with two folds at the bottom), and the knot is tied in front.

¹⁷Kō-bon ni [香盆ニ].

A “kō-bon” [香盆] could be any sort of tray that was large enough for the incense burner, kōgō, and (in this case) kyōji-tate [香筋建]* to fit on comfortably. In the present day small naga-bon (which does not conform with the dimensions of any of the classical trays described in the Nampō Roku) seem to be preferred by the modern schools, but in the classical period, square and round trays were used as well.

__________

*The kyōji-tate [香筋建] (it can also be written kyōji-tate [香箸立] -- though this form was considered rather inelegant) is like a miniature shaku-tate, in which the implements necessary for burning kyara [伽羅] incense in a hand-held censer are stood.

While the list may be abbreviated (and in the context of chanoyu, almost always is), the full set consist of:

- gin-yō-basami [銀葉挾] (a pair of pincers with flat heads that are used to handle the gin-yō [銀葉] -- mica squares on which the incense rests while being burned);

- kō-saji [香匙] (a sort of spoon used to scoop up the pieces of kyara when transferring them from the chopping block to the kōgō: incense wood is split into small pieces using a razor-sharp steel chisel, and the pieces are then handled with a special spoon in order to avoid contamination by the oils in the human hand);

- kyōji [香筋] (ebony chopsticks used to move one piece of kyara from the kōgō onto the gin-yō, in the kōro);

- an object called an uguisu [鶯], or uguisu-kushi [鶯串] (a flat platform, often shaped like a plum blossom, through which a long toothpick-shaped needle is poked: the uguisu is used to create a flat top to the mound of ash in the kōro where the gin-yō will rest; and, simultaneously, a chimney through which the heat from the charcoal rises upward: the name comes from the fact that the uguisu [鶯] feeds on the pollen of the plum blossom, hence the platform is shaped like a plum blossom, while the needle poking through suggests the bird's beak penetrating deep into the flower);

- koji [火筋] (metal chopsticks used to handle the burning tadon [炭團] -- the little briquettes made of processed charcoal that were used to heat the kōro);

- hai-oshi [灰押] (an object, shaped like a closed folding-fan, that is used to press the ash in the kōro into a conical shape after the burning charcoal has been put inside);

- and a miniature habōki [羽箒] (a feather duster used to clean the rim of the kōro after the ashes have been shaped).

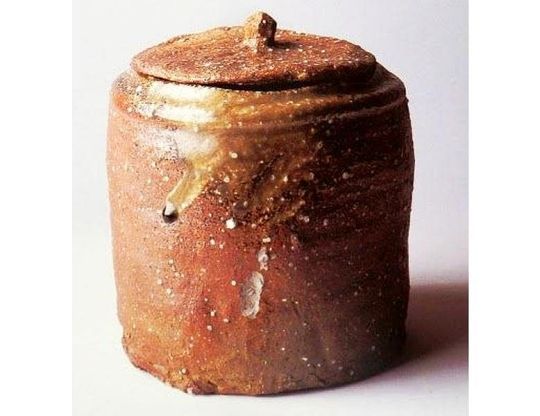

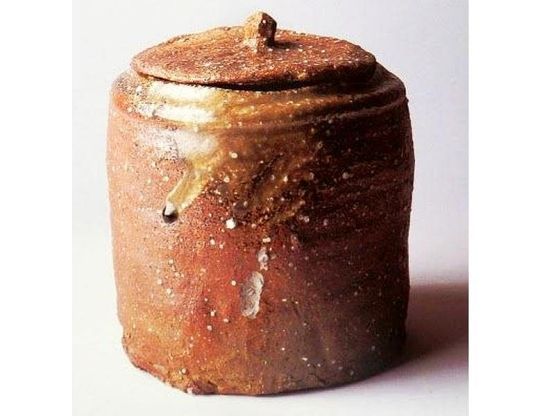

¹⁸Kōro Usu-gumo [香爐 薄雲].

Usu-gumo [薄雲] is the name of a famous variety of kyara incense wood (not a kōro). Tanaka Senshō's manuscript (which was the document copied by Jitsuzan with the Shū-un-an papers before him) reads kō-bon ni kōro ・ usu-gumo mei-kō ・ kōgō futae aogai [香盆ニ香爐 ・ 薄雲 名香 ・ 香合 二重青貝], suggesting that Tachibana Jitsuzan made a mistake when transferring this information from his original notes to the notebook that he intended to present to the Enkaku-ji*.

As for the kōro itself, since Rikyū does not give a name, it was probably not the celadon Chidori kōro [千鳥香爐] that had been one of Jōō's treasures. Most likely, it was the ido-kōro [井戸香爐], that is shown below.

This kōro is now known as Kono-yo [此世], the name he wrote on its box (and presumably gave to it) just before his death.

__________

*While Shibayama Fugen states that Usu-gumo [薄雲] is the name of the kōro, it must be remembered that Fugen was relying on a set of notes set down by one of the auditors during the discussion of the Enkaku-ji manuscript that took place after Tachibana Jitsuzan had presented his text to that temple. In order to preserve the secrecy of the text, it appears that it was forbidden for the participants to write anything down while they were in the Enkaku-ji. Thus, this document was set down only after the person had returned to his home. (As such, it is rather remarkable that, on the whole, the text is exactly the same as the Enkaku-ji version. Copies taken from this manuscript circulated around Kyōto for many years, until the authentic Enkaku-ji version was finally published in the middle of the 20th century, and I have had the chance to inspected several of these copies on different occasions.)

¹⁹Kōgō futae ao-gai [香合 二重青貝].

Ao-gai [青貝]* is mother-of-pearl inlay.

Most surviving ao-gai kōgō from Rikyū's period are of the usual sort. A much smaller number have three levels (mie-kōgō [三重香合]). Kōgō with two levels (futae-kōgō [二重香合]) are all but unknown today, since they do not meet the modern demands as established by the tea schools†.

__________

*More commonly known as raden [螺鈿] today.

†A kōgō with two levels usually held the incense (enclosed within small envelopes) in the upper level, and a supply of gin-yō [銀葉] in the lower. Burned out incense pieces (which were fused to the gin-yō on which they were heated) were discarded into a separate taki-gara-ire [炷空入] -- often the kind of container used as a ceramic kōgō today.

A three-level kōgō includes a silver-, pewter-, or copper-lined lower level into which the burned-out incense is discarded.

It appears that Rikyū intended that the kōro be placed in the toko after the guests had finished appreciating the incense, so that it would continue to perfume the room during the remainder of the chakai. In fact, it may have been to suggest this intention that he did not arrange a taki-gara-ire on the kō-bon -- as would have been customary.

²⁰Kyōji-tate [キヤウシ立].

This is a vase-like object, usually made of metal, in which the implements used when preparing the kōro* are kept when not in use.

___________

*See footnote 17 for a complete listing of these things, including a description of their purposes. Rikyū probably abbreviated the number of things, since some of their functions could be performed by the utensils used during the sumi-temae (the regular ro-yō hibashi, for example, would have been used to transfer the burning tadon from the ro to the kōro; and the large habōki to dust the rim of the kōro).

²¹Habōki [羽帚].

This was an ordinary habōki, made from feathers around 1-shaku in length.

While it is not possible to know what kind of feathers were used, it was the season when the geese were flying north, and so these birds would have been taken from time to time by Hideyoshi's hawkers, with the feathers available to Rikyū for his purposes.

²²Kōro mawarite issumi ari [香爐マハリテ一炭アリ].

In other words, the tadon [炭團] (a small briquette of high-quality processed charcoal that is used to heat the kōro) were placed in the ro just before the guests entered the room for the shoza*, so Rikyū began the gathering by inviting the guests to appreciate incense, then prepared the kōro and offered it to them.

After they were finished, the kōro was placed in the tokonoma (probably by Rikyū)†, and Rikyū turned his attention to the ro. Because, according to san-tan san-ro [三炭三爐] practice, the fire in the ro should be rebuilt at midday (after having been laid at dawn), the charcoal would have burned down to mostly hot embers by this time‡, thus Rikyū would have added a more or less full set of charcoal, as he notes (rather than the several pieces added during the sumi-temae at a morning or evening gathering**). His use of the term issumi [一炭] implies that Rikyū had not replenished the fire prior to the arrival of his guests.

__________

*The use of the small tsuri-gama would have helped facilitate the insertion and removal of the tadon without having to take the kama out of the ro first.

When a large ro-gama was used, Jōō said that the gotoku should be moved diagonally toward the far left corner when the ro was set up, thus leaving more space in the front right corner for the host to reach in (with the ro-yō hibashi) to remove the tadon. (The koji [火筋] would never have been long enough to reach the tadon kindling deep in the ro.)

†The piece of kyara would not have been anywhere near exhausted by the time that the two guests finished passing it back and forth three times -- one piece of kyara (about 5-bu square) was intended to last long enough for five or six (or even up to ten) people to appreciate it three times each before its fragrance began to disappear. Therefore, to remove the kōro from the room would have been wasteful. The fact that Rikyū did not prepare a taki-gara-ire [炷空入] suggests that the idea of placing the kōro in the toko was planned beforehand (and the kane-wari for the goza also bears this out -- since the kōro was left in the toko until the end of the chakai).

Rikyū would have gone out to the katte and brought a small tray of some sort into the room that would serve as a base for the kōro when it was lifted into the toko. It would have been placed between the bon-san and the toko-bashira, forward of the midline of the toko, and associated with a yang-kane, as shown in the sketch.

‡Dawn occurs around 5:08 on April 10 in this part of Japan. Thus, the fire in the ro would have been burning for at least seven hours when this chakai began. The charcoal would have been reduced to ash-covered mounds (referred to as shira-zumi [白炭] by Jōō in the Hundred Poems), with perhaps only the large dō-sumi [胴炭] still partially intact. The dō-sumi would have been broken in half with the hibashi and moved to the middle of the ro, with the remaining embers (knocked free of their white ash coating) piled around it, after which shimeshi-bai would have been sprinkled over the white ash to make the ro look tidy. Then the wa-dō would have been placed on the right side of the pile of embers, toward the right-front corner of the ro, and then gitchō and wari-gitchō were added in a circle around the embers. This was how Rikyū arranged the charcoal.

During the ro season, the white eda-zumi [枝炭] -- carbonized azalea twigs coated with gesso -- were not used by Rikyū. These were used only during the furo season (if they were used at all by him), when laying the fire around a shita-bi of three burning gitchō. It is completely wrong to call the eda-zumi “shira-zumi” [白炭], and this mistake has lead to much confusion over the meaning of several of Jōō's verses in the Hundred Poems.

**The fire was added to the ro at dawn, so by the time of a morning gathering, the fire would still be fairly strong, with much of the charcoal still unburnt.

Likewise, the ro was emptied, cleaned, and a new fire was laid at dusk. Thus, when an evening chakai was scheduled, the fire would still be fairly strong, necessitating the addition of only a little charcoal to bring the kama back to a boil and keep it boiling until the service of usucha was concluded.

In the case of this chakai, however, the fire in the ro when the guests entered would have been the one laid at dawn (and, since a morning chakai had not preceded this one, the charcoal would have mostly burned down by this time). Consequently, the sumi-temae started with the collection of the burning embers into the middle of the ro, followed by the addition of a wa-dō [輪胴] -- the large circular piece cut from the thickest end of the long piece of charcoal as received from the charcoal shop -- which had to be retrieved from the bottom of the sumi-tori (unlike now, Rikyū placed the large pieces on the bottom and then piled gitchō and wari-gitchō on top to fill the sumi-tori; meaning that a number of these smaller pieces had to be moved into the haiki before the large piece on the bottom could be accessed, and the rest of the sumi-temae took place using the smaller pieces from the haiki) as the foundation for the new fire. Then a number of gitchō and wari-gitchō were used to encircle the embers. The arrangement, therefore, was much simpler than what evolved during the Edo period; but the very lack of strict rules meant that it also required careful thought on the part of the host -- so that he would add enough charcoal, yet not too much.

The elaborate sets of charcoal of different sizes and shapes concocted by the various tea schools during the Edo period were intended to make the task of building the fire as easy as possible -- so that even an incompetent host (someone with no real interest in chanoyu, for example) could manage to get the kama boiling without too much difficulty. And the go-sumi-temae [後炭手前], performed between the koicha-temae and the usucha-temae, meant that he did not have to worry that the kama would stop boiling before the service of tea was finished.

²³Sakemono jū-jū [サケ物重〻].

Both Tanaka Senshō and Shibayama Fugen have Sagemono-jū ni [サゲ物重ニ = 提げ 物 重 ニ] for this entry. A sagemono-jū [提げ 物 重] -- or sage-jūbako [提げ重箱] -- is a set of multi-tiered food boxes that can be carried by hand (such as to a picnic -- the purpose for which such sets of boxes were originally created). The particle ni [ニ], of course, means “in.” That is, the kashi enumerated below were all arranged in a stacked set of boxes, from which the guests were free to help themselves.

²⁴Yomogi no mochi [ヨモキノモチ].

This was mochi (steamed rice-cake) made with yomogi [艾] (mugwort, Artemisia princeps), which makes the mochi dark green and gives it an herbal flavor and smell. Yomogi-mochi were traditionally served on the Third Day of the Third Month.

In the old days, large sheets or cakes of mochi made with yomogi were cut into small pieces and simply served in that way. By the Edo period, mochi dough was wrapped around a ball of sweetened anko [餡子] made from the red azuki [小豆] bean. It is not known which sort of yomogi-mochi Rikyū offered to his guests during this chakai.

²⁵Nimono tori ・ kushi-awabi ・ shiitake ・ mame ・ musubi-me [煮物 鳥 ・ 串アハヒ ・ 椎茸 ・ マメ ・ ムスヒメ].

These “kashi” were all cooked by boiling in broth (nimono [煮物]). However, they would have been drained (and probably allowed to cool off) before being put into the box. These offerings consisted of:

- tori [鳥]: probably small birds (such as sparrows or finches), mashed into a paste and formed into dango [團子] (meatballs) that were threaded on a skewers in threes and so boiled;

- kushi-awabi [串鮑]: abalone that had been dried on skewers, rehydrated by boiling in broth, and then sliced;

- shiitake [椎茸]: probably dried shiitake mushrooms that were boiled in the broth after having been soaked in water overnight (the drying process makes them sweeter and more flavorful, and so better for boiling than the fresh mushrooms);

- mame [豆]: probably the large, white ōfuku-mame [大福豆], an especially large variety of the common ingen-mame [隠元豆] type of beans;

- musubi-me [結び芽]: wakame [ワカメ = 若芽] (a type of green seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, that resembles a small size kelp), cut into short lengths that were then tied into decorative knots.

²⁶Mizu-kuri [水栗].

Raw chestnuts that have had part of the brown pellicle carved away with a knife, then soaked in water for several hours to remove the bitterness from the remaining pellicle before serving.

According to Tanaka Sensho, the pellicle was scratched away from half of the chestnut in a coma shape, resulting in a three dimensional futatsu-tomoe [二つ巴] design (the “yin-yang symbol”).

²⁷Go [後].

The go-za.

In terms of kane-wari:

- the toko, which now contains the scroll, the bon-san, and the kōro, would be han [半];

- the room remained han [半], since all it contained was the kama in the ro;

- and the daisu was also han [半]*.

Han + han + han is han. This is correct for the goza of a chakai held during the daytime.

___________

*The ji-ita remained han, and the ten-ita, with the sasa-mimi and a naka-bon bearing the kasane-chawan and a natsume, would have been chō. Han + chō is han.

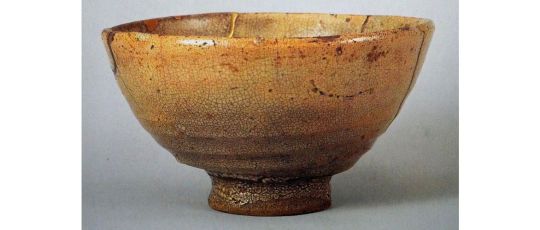

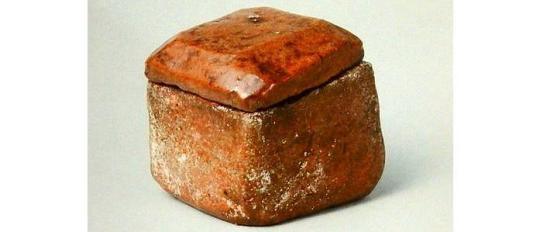

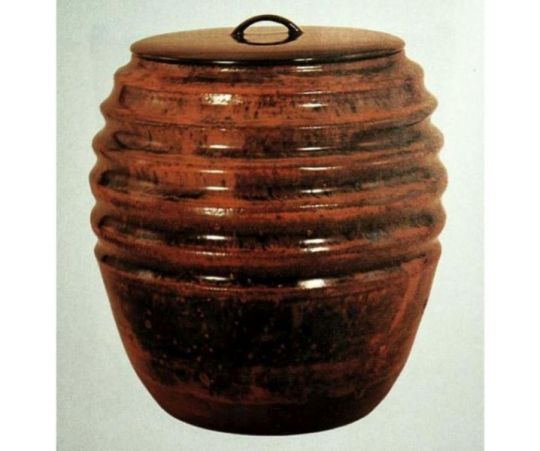

²⁸Chaire sasa-mimi [茶入 サヽ耳].

The sasa-mimi [笹耳]* is a rather exaggeratedly etiolated chaire, originally made as a vessel for perfumed beauty-oil (the shape allowed it to be poured out without splashing); the pair of ears were there so that a cord could be tied onto one, crossed over several times as it passed over the stopper, and then tied onto the other ear to secure the lid and prevent spillage. Chinese sasa-mimi containers came in several different colors, with brown (as seen below) and egg-shell-white being most common.

Rikyū has marked this chaire with a red dot, indicating that it was one of the featured utensils -- probably as a nod to the fact that it was the Hina-matsuri.

Though described first, the tea in the sasa-mimi was used to serve usucha. Therefore, though the sasa-mimi was usually provided with a shifuku, the shifuku was removed and placed flat on the daisu on this occasion (to protect the lacquer of the ten-ita from being scratched by the foot of the chaire) with the sasa-mimi standing on top of it.

___________

*Sasa-mimi [笹耳] means “ears shaped like the leaves of the bamboo-grass.”

²⁹Naka-bon ni [中盆ニ].

This could have been either be a square tray or a round one.

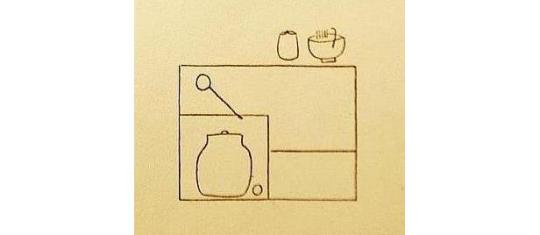

³⁰Natsume ・ kasane-chawan ・ ori-tame [ナツメ ・ カサネ茶碗 ・ 折タメ].

The natsume (probably a ko-natsume [小棗], since there were only two guests) contained tea for the koicha*.

It is not possible to guess which chawan Rikyū used on this occasion†, though the chakin, chasen, and chashaku (shown below) would have been arranged in the upper of the two bowls.

The chashaku was one of Rikyū’s ori-tame, and example being shown below.

As for how the chashaku may have been displayed, there are two possibilities:

1) it may have been placed across the rim of the smaller chawan, as shown in the left sketch;

2) or, it may have been placed on the tray, with the handle resting on the front rim, between the kasane-chawan and the natsume, as shown on the right‡.

___________

*The tea in the container displayed on the tray was considered to rank above that in the container that was not placed on a tray.

†The word kasane-chawan [カサネ茶碗] appears several times in the Nampō Roku, but the particular chawan used by Rikyū for this purpose, or their sizes, are not discussed.

Somewhat later he used a pair of black Raku-chawan (known as o-guro [オグロ, 小黒], “small black,” and ō-guro [オーグロ, 大黒], “large black” – the smaller bowl, which still exists, is around 3-sun 8-bu in diameter; while the larger, which has disappeared, was a little over 4-sun in diameter) as his kasane-chawan; but at the time of this chakai Chōjirō does not seem to have started producing his black bowls yet. (They first appeared during the summer -- according to a questionable entry in this kaiki -- or early autumn of 1587, perhaps making a sort of debut to the tea world at the Kitano ō-cha-no-e [北野大茶會], which opened on the First Day of the Tenth Month of that year.) . As mentioned above, only the smaller bowl survives now, and somehow it has acquired the name of the larger of the pair.

In the sketch I suggested one of the ido bowls as the larger chawan, with an aka-chawan as the smaller, but this is pure speculation.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Us, April 8

Cover: Jennifer Lawrence Quits Hollywood for Love

Page 2: Red Carpet -- Black and White -- Candice Swanepoel, Charlize Theron, Viola Davis, Angela Sarafyan, Leighton Meester

Page 3: Julia Roberts, Sandra Oh, Nicole Kidman, Rosamund Pike, Amber Heard

Page 4: Who Wore It Best? Ellie Goulding vs. Jasmine Sanders, Lili Reinhart vs. Sara Foster, Angelina Jolie vs. Gal Gadot

Page 6: Lily James vs. Leslie Grossman, Sonequa Martin-Green vs. Paloma Faith, Bella Hadid vs. Halsey

Page 8: Alicia Silverstone vs. Kimberly Schlapman vs. Liza Koshy

Page 10: Loose Talk -- Kelly Ripa responding to her daughter, Winston Duke on how his mom keeps him grounded, Mandy Moore on Queer Eye’s Karamo Brown, Lin-Manual Miranda on watching Hamilton with Prince Harry, Kate Beckinsale on her cat

Page 13: Contents

Page 14: Hot Pics -- Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards -- Fuller House stars Candace Cameron Bure and Andrea Barber and Jodie Sweetin showed their support for Lori Loughlin, Chris Pratt got slimed

Page 15: Will Smith, Heidi and Spencer Pratt and son Gunner, Janelle Monae, Jennifer Hudson, Lana Condor and Noah Centineo

Page 16: Nick Jonas and Joe Jonas and Kevin Jonas and Priyanka Chopra Jonas and Sophie Turner in Miami

Page 19: Prince Charles and Duchess Camilla, Taylor Kinney and Wilder Valderrama, Becca Kufrin and Caroline Lunny and Tia Booth and Garrett Yrigoyen

Page 20: Ariana Grande, Serena Williams and Roger Federer, Dolly Parton

Page 22: Lupita Nyong’o and Evan Alex and Shahadi Wright Joseph and Winston Duke and Jordan Peele at the premiere of Us, Amy Poehler, Machine Gun Kelly and Tommy Lee at the premiere of The Dirt

Page 24: 10 Things I Hate About You on it’s 20th anniversary -- Heath Ledger, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Gabrielle Union, Larisa Oleynik

Page 25: Julia Stiles, Allison Janney, Andrew Keegan, David Krumholtz, Susan May Pratt

Page 26: Highlighter-colored chic -- Ashley Graham, Jordyn Woods, Chanel Iman, Kendall Jenner

Page 27: Sailor Brinkley-Cook, Tinashe, Blake Lively, Bella Hadid, Dorit Kemsley

Page 30: Stars They’re Just Like Us -- Fergie, Dwayne Wade and Gabrielle Union, Jamie Chung

Page 31: Bella Thorne, Ron Howard, Katherine Schwarzenegger, Natalie Portman

Page 32: Furry Friends -- Martha Stewart and dog Han, Colton Underwood and cat Maverick, Andy Cohen and dog Wacha, Isla Fisher and her dog Busta, Halle Berry and dog Jackson -- Please adopt, don’t shop

Page 34: Hollywood Moms -- Brooklyn Decker on being a mom to two kids with Andy Roddick

Page 35: Chrissy Teigen and John Legend are gearing up for their daughter Luna’s third birthday, Edie Falco’s kids are run-of-the-mill preteens, Morena Baccarin tries to be a good role model to her daughter

Page 36: Love Lives -- Miley Cyrus’ brother Trace thinks Liam Hemsworth is awesome

Page 37: Justin Verlander knows he scored big when we won over Kate Upton, Karamo Brown planning his wedding to Ian Jordan to be like Priyanka Chopra and Nick Jonas, Dylan Sprouse couldn’t be prouder that girlfriend Barbara Palvin just earned her Victoria’s Secret wings

Page 38: Hot Hollywood -- Ben Affleck and Lindsay Shookus going strong

Page 39: Felicity Huffman and William H. Macy on the rocks over the college admissions scandal, Lori Loughlin’s daughters are upset with her and husband Mossimo Giannulli for the fallout of the college admissions scandal especially Olivia Jade who has lost endorsement deals, Melanie “Mel B” Brown admits she hooked up with fellow Spice Girl Geri Halliwell

Page 40: Christina Anstead expecting a baby with husband Ant Anstead in September, Paris Hilton dating British comedian Jack Whitehall, stars who have gotten into the wine business -- Sarah Jessica Parker, the Vanderpump gals, Ayesha Curry, Jon Bon Jovi, Kurt Russell

Page 41: Jessica Simpson’s third baby Birdie, VIP Scene -- Don Lemon and Debi Mazar, James Franco, Owen Wilson, Alex Rodriguez, Michelle Williams, Rami Malek, Elle Fanning, John Stamos

Page 42: What’s in My Bag? Sofia Carson

Page 43: Jenny McCarthy was miserable on The View, Jameela Jamil claps back at body shamers and bullies like Khloe Kardashian, Piers Morgan, Cardi B, Kim Kardashian, Quentin Tarantino

Page 44: Cover Story -- How Jennifer Lawrence finally found happiness

Page 47: Other stars who left Hollywood -- Phoebe Cates, Jonathan Taylor Thomas, Mischa Barton, Leelee Sobieski, Taylor Momsen, Jack Gleeson, Cameron Diaz

Page 48: Amanda Stanton and Bobby Jacobs happily ever after

Page 50: She’s headed toward age 50 but Jennifer Lopez has never looked better

Page 54: The Wellness Hacks of Other Ageless Stars -- Jennifer Garner, Padma Lakshmi, Diane Kruger, Elizabeth Hurley, Angela Bassett, Jennifer Aniston, Heidi Klum

Page 56: Hot Couple Alert -- Lady Gaga and Jeremy Renner

Page 60: Style -- Timepieces -- Kate Upton

Page 61: Mandy Moore

Page 62: Beauty -- Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, Joan Smalls, Ashley Benson

Page 63: Beyonce, Kat Graham, Karlie Kloss

Page 65: AJ McLean’s Hot Tracks

Page 66: Lorraine Toussaint on The Village

Page 67: Chase and Savannah Chrisley on their spinoff Growing Up Chrisley, Buzzzz-o-Meter -- Lea Michele, Taylor Swift, Paris Hilton

Page 70: Fashion Police -- Poppy, Carson Kressley, Betty Who

Page 71: Shania Twain, Ta’rhonda Jones, Keira Knightley

Page 72: 25 Things You Don’t Know About Me -- Luann de Lesseps

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The NYC Hit List The Best New Restaurants In NYC added to Google Docs

The NYC Hit List The Best New Restaurants In NYC

Wondering where you should be eating in New York City right now? You’re in the right place. The Infatuation Hit List is your guide to the city’s best new restaurants.

And when we say “best new restaurants,” we mean it. Because we’ve tried every single one of these places - and we’ve also left off countless spots that simply aren’t as worthy of your time and money.

The Hit List is our record of every restaurant that’s opened in the past year that we’d highly recommend you try. This guide is sorted chronologically, so at the top you’ll find our latest entries to this list (the newest spots), and as you keep scrolling you’ll find the places that are on the older side - but are great enough that we still haven’t stopped talking about them.

New to The NYC Hit List (as of 2/19/20): Quality Bistro, Jua, Peoples Wine

Some spots you might have heard about that didn’t make the cut: American Bar, 232 Bleecker, Būmu, Torien, Nowon, Portale, Leo, Il Fiorista, and Gotham Bar And Grill

And for more in-depth guides to the best new Brooklyn or Uptown spots, check out the Brooklyn Hit List and the Uptown Hit List.

The Spots Quality Bistro $$$$ 120 W 55th St

Quality Bistro is a massive French restaurant in Midtown that has about as much gold detailing as the Salon of Venus at Versailles. The 400-bottle French wine list and the four filet mignon options might make it sound like a place to send in-laws before 6pm tickets for Chicago, but this place - from the people behind Don Angie, Quality Meats, and about 10 other popular spots - isn’t stuffy. There’s a casual bar area that gets packed with after-work crowds, and dining rooms that are louder and darker than your typical spin class. Share big portions of excellent French-leaning food with a date who you want to impress, or clients who purposefully didn’t book early flights tomorrow.

Peoples Wine $ $ $ $ Wine Bar in Lower East Side $$$$ 115 Delancey St

We’re currently more impressed with Peoples Wine than we are with any candidate running for president or the poodle who won the Westminster Dog Show. The first reason being, this bar from the Contra and Wildair team serves great snacks as well as natural wine you either haven’t heard of or you already love. And the second is that Peoples has somehow created a space where you’ll want to spend multiple hours, despite the fact that it’s located in the basement of a LES food hall.

Dan Ahn Jua $$$$ 36 E 22nd St

Jua is from the group behind Atomix and one of our all-time Greatest Hits, Her Name Is Han. What we’re trying to say is, we can’t remember the last time we were so excited to go to Flatiron. This Korean restaurant’s space falls somewhere between special-occasion Atomix and group-friendly Her Name Is Han, but with food that has something in common with both - we’re still thinking about it long after leaving. Dinner starts with deep-fried seaweed wrapped around uni and a ton of caviar, and the next eight dishes on the $95 tasting menu, including a bunch of things cooked on the wood-fired grill, are just as memorable. While you can order a la carte, you should come here for the two-hour set menu and share a bottle of natural wine with a date.

Verōnika $ $ $ $ European in Flatiron , Gramercy $$$$ 281 Park Ave S Not

Rated

Yet

If there were an Oscars ceremony for restaurants, we’d feel comfortable nominating Verōnika for several categories, like Best Borscht, and Best Impression Of a 19th-Century Aristocrat’s Clubhouse. Even if Verōnika’s Eastern European food weren’t elegant and delicious (it is), the room alone could make your night - from portraits of powerful women on the walls and little Bauhaus-style lamps on every table, to ceilings so high it’s almost inappropriate not to have a firehouse pole. Verōnika is unquestionably formal, but after a few visits, the food is what stands out here compared to other special occasion spots in the city. You’ll find Eastern European classics, like porky borscht, lamb goulash with nicely chewy spätzle, as well as black cod dish with a lemony beurre blanc sauce that will be memorialized in our hearts and minds for years to come.

Chikarashi Isso Chikarashi Isso $ $ $ $ Japanese in Financial District $$$$ 38 Rector St Not

Rated

Yet

Like Richie and Chas Tenenbaum, you wouldn’t know Chikarashi and Chikarashi Isso were related if it weren’t for the name. Whereas Chikarashi draws long lunch lines for fast-casual poke bowls, Chikarashi Isso is a high-end Japanese restaurant in FiDi where you’ll find wagyu with caviar and wok lobster with soft shell shrimp. And despite a diverse menu with tempura, yakitori, and soba, each of these dishes could pass as the restaurant’s specialty. That’s especially the case with the yakitori, and it’s why the chef’s selection of six delicious skewers of chicken and vegetables needs to be on your table. Come here for a laidback business meal the next time you’re near the Stock Exchange.

Itay Paz Zizi $ $ $ $ Middle Eastern in Chelsea $$$$ 182 8th Ave Not

Rated

Yet

The first law of thermodynamics states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, but that it can change forms and locations. While we never understood it in high school, we think we get it now after eating at ZiZi. What Williamsburg lost when Zizi Limona (a utility spot that worked for everything from group brunch to dinner with parents) closed in September, Chelsea gained when ZiZi opened there a month later. The menu at this casual Middle-Eastern spot is almost identical, including a fantastic shawarma plate with juicy chicken and lamb over creamy hummus, and the space even looks similar, with lots of exposed brick, a small bar lined with wine bottles, and a couple of tables on the sidewalk outside.

Melissa Hom Piggyback $ $ $ $ Thai , Filipino in Chelsea , Koreatown $$$$ 140 W 30th St Not

Rated

Yet

People are constantly asking us where they can sit down and grab a dinner that won’t make them sad around Penn Station. Koreatown has a bunch of great spots, and Farida is only about six blocks away - but Piggyback is now the best option within several hundred feet. It’s from the same people behind Pig and Khao, and the menu is a mix of mostly Southeast Asian things like lumpia, Thai fried rice, and a big bowl of crudo with grapefruit, cashews, and crunchy strips of pork. We especially like the flaky curry puffs stuffed with a very large handful of heavily-spiced beef, and we suggest you stop by the next time you find yourself around 30th street to get them. Bring a few friends. It’s a fun spot with loud music and murals on the walls, and they make some solid cocktails.

Tyson Greenwood Kindred $ $ $ $ Pasta , Mediterranean , Wine Bar in East Village $$$$ 342 E 6th St Not

Rated

Yet

Ruffian is one of our favorite wine bars in NYC, and the only reason we hesitate to recommend it to everyone is the fact that the 19-seat space tends to fill up before most people get out of work. But you don’t need to run the risk of a two-hour wait for excellent Mediterranean food and natural wines in the East Village anymore because Kindred, which is from the same people, opened around the corner. The small bar area up front is great for small plates and Happy Hour drinks, but unlike Ruffian, there’s also a full dining room. Come here with a date, and share some Slovenian orange wine and housemade pasta.

Rachel Vanni Ernesto's $ $ $ $ Spanish , French in Lower East Side $$$$ 259 E Broadway Not

Rated

Yet

Ernesto’s is the new restaurant we’re getting asked about the most. It’s a Basque-inspired place that’s already packed with people eating pinxtos, sitting in leather chairs we’d like to own, surrounded by red brick and gold fixtures and globe lights. On a first visit, we weren’t blown away by the food - with the exception of a tower of housemade potato chips and iberico ham - but the restaurant experience made up for it. It’s a place where you want to hang for a while, or as long as the sommelier/wine whisperer keeps suggesting different half-glasses of French and Spanish natural wines for you to try.

Noods n' Chill Noods n’ Chill $ $ $ $ Thai in Brooklyn , Williamsburg $$$$ 170 S 3rd St Not

Rated

Yet

Let’s get one thing out of the way: Noods n’ Chill is not a great name. It sounds like an upstate retreat with a lax dress code or a text you’d receive from an unsaved number at 12am. But none of that matters. Because Noods N’ Chill is where you’ll find the best Thai food in Williamsburg. This tiny counter-service spot is from the same people behind Look By Plant Love House (one of our favorite Thai restaurants in the city), and most things here cost less than $15. The guay tiao tom yum soup - with its spicy broth, tender fish balls, and abundant noodles - is an excellent choice, and you should go ahead and get a few pork buns to start your meal. Try this place for a casual weeknight dinner (that’s better than most) or stop by for brunch, when there’s stuff like kaya toast and porridge.

Marko Macpherson Bar Bête $ $ $ $ French in Carroll Gardens , Cobble Hill $$$$ 263 Smith St Not

Rated

Yet

Bar Bête is NYC’s latest restaurant serving roast chicken on marble tables beneath large hanging globe lights. But this trendy Cobble Hill spot has more to offer than the possibility of a Bon Appetit staff member sighting. It’s where you should absolutely have dinner with a date in the area. The simple reason being, they serve thoughtful and delicious French food (like a peekytoe crab omelette) that makes ordering the roast chicken seem about as inspiring as proposing to someone at a Yankees game. So don’t write it off as just another trendy roast chicken restaurant.

Noah Fecks Banty Rooster $ $ $ $ American in West Village $$$$ 24 Greenwich Ave Not

Rated

Yet

The Banty Rooster is a rare example of a West Village place that exceeded our expectations. At first glance, this casual American spot feels like countless other places in the area serving potato fritters and short rib. But then you’ll notice that the fritters are served with salt cod aioli and the short rib crumbles when you dip it in the side of ancho barbecue sauce. Between the food, big space, and affordable wine offerings, this place should be at the top of your list for your next group dinner in the West Village.

Melissa Hom Kochi $ $ $ $ Korean in Hell's Kitchen , Midtown $$$$ 652 10th Ave Not

Rated

Yet

We’ve long championed eating things on sticks. But while seven of the nine courses at Kochi are served on skewers, that’s not the reason we’re telling you to go. You should go to this Korean tasting menu spot in Hell’s Kitchen because everything from the raw scallops and fluke at the beginning of the meal to the black sesame ice cream pop at the end is delicious. You’ll leave feeling full, and considering the variety and quality of everything here (including bibimbap topped with tons of uni), the $75 price tag feels reasonable, especially while it’s still BYOB.

Liz Clayman Le Crocodile $ $ $ $ French in Brooklyn , Williamsburg $$$$ 80 Wythe Ave 8.2 /10

The restaurant space in the bottom of the Wythe Hotel has always been one of our favorites. It has huge windows, high ceilings, and brick walls that wouldn’t feel out of place in a rural castle from the fifteenth century. And now that Le Crocodile has moved in, we’d like to eat there every day. This French restaurant is from the people behind Chez Ma Tante in Greenpoint, and the menu is equal parts traditional and exciting. You’ll find escargots and steak tartare, for example, and it also has a pork chop covered in burrata and some roast chicken with several fistfuls of fries on the side. Order all of these things. And be sure to book a table before more people realize they should eat here.

Anton's $ $ $ $ American , Italian in West Village $$$$ 570 Hudson St 8.2 /10

Anton’s might have only just replaced Frankie’s 570 in the West Village, but it feels like this Italian restaurant has both been around forever and is here to stay. On our first visit a week into service, it was already running like a well-oiled machine, and almost everything we tried we’d want to eat again. With its dark wood, long bar, and ideal amount of candlelight, it’s the kind of place that makes you want to become a regular who has a standing martini and steak and/or pasta order. Speaking of which, the pastas are where we’d recommend you focus your order.

Flora Hanitijo Mina's $ $ $ $ Greek in Long Island City $$$$ 22-25 Jackson Ave Not

Rated

Yet

Not all museum restaurants are created equal. And Mina’s, the new Greek small plates spot in MoMA PS1, is proof. Unlike most museum cafeterias or upscale restaurants that feel like museums themselves, Mina’s is both casual and pleasant. The bright space is ideal for a brunch or snack involving things like a creamy muhammara, perfectly oily anchovies, and an excellent Greek egg and cheese boat peinirli. Take someone here who likes natural wine, Sally Rooney books, and the color seafoam. They’ll want to move in.

The Riddler The Riddler $ $ $ $ American , French , Raw Bar in West Village $$$$ 51 Bank St 8.1 /10

While we were drinking from a Chambong at The Riddler in the West Village, the couple at the table over stared at us, so transfixed by what they were seeing that they forgot they were holding shrimp cocktail in midair. Whether you want to have a classy evening involving raw bar and several glasses of Champagne, or debauchery by way of Chambong and glasses of wine filled to the literal brim, you’ll have a good time at this Champagne bar in the West Village. Just be sure to order the raclette burger and to make a reservation - the space is small and there’s very little room for walk-ins.

Zooba $ $ $ $ Middle Eastern , Egyptian in Nolita $$$$ 100 Kenmare St 8.5 /10

Zooba is a fast-casual restaurant in the same way that Bob Ross is a watercolor painter. It’s technically true, but there’s a lot more exciting context. This is the first US location of an Egyptian spot with several locations in Cairo, and it’s officially where you should be getting lunch or a quick dinner in the Soho area. The ceiling in here is covered with neon signs and it’s pretty difficult not to admire the flashing lights above you while you wait in line. But the food is more memorable than any of that. The specialty is the ta’ameya (fried balls made out of fava beans), which you can and should order spicy, but we also love the hawawshi beef patty sandwich with cheese. Most things come on a soft homemade Egyptian pita called baladi and everything costs under $15. If you work anywhere downtown - we suggest beelining here.

Nami Nori $ $ $ $ Sushi in West Village $$$$ 33 Carmine St 7.6 /10

Nami Nori feels like a tiny West Village boutique or a cinematic version of the afterlife. It’s a bright and attractive space on Carmine Street with two bars and just a handful of tables, and pretty much everything is either white, off-white, or a soothing shade of light brown. They specialize in hand rolls that are left open like tacos (instead of being cylindrical or cone-shaped). And of the 20 different kinds - like tuna poke with crispy shallots, lobster tempura with yuzu aioli, and a few classic varieties - the least-complicated ones are the best. For $28 you can get a chef’s selection of five rolls, and there are also a bunch of small plates like shishito peppers and miso clam soup, most of which cost less than $10. Start with one or two of those, get the chef’s selection, and you’ll have a very good and reasonably priced (for sushi) meal.