#eugene o'neill

Text

Paul Robeson is Brutus Jones in the 1933 film adaptation of Eugene O'Neill's The Emperor Jones. Photograph by Edward Steichen for Vanity Fair, August 1933.

#paul robeson#eugene o'neill#lit#1930s#black history#b&w#film#black excellence#culture#retro#black tumblr#indie#civil rights#theatre#icons#history#actor#black men#activism#cinema#blm#vanity fair#photos#edward steichen#📸

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robert Sean Leonard in Eugene O'Neill : a documentary film (2006)

He used to play Edmund from Long Day’s Journey into Night

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long Day's Journey into Night (1962)

Jason Robards as Jamie Tyrone

Katharine Hepburn as Mary Tyrone

Ralph Richardson as James Tyrone

Dean Stockwell as Edmund Tyrone

directed by Sidney Lumet

cinematography by Boris Kaufman

#long day's journey into night#jason robards#katharine hepburn#ralph riachardson#dean stockwell#jamie tyrone#mary tyrone#edmund tyrone#sidney lumet#boris kaufman#lumet and kaufman went off#eugene o'neill

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I took a class on american gothic literature and we read a semi-autobiographical play based on the playwright's fucked up family and my professor said that the writer made the stage his own personal haunted house. he took the pain that he lived through and lined it all up in front of him and had it played over and over and over again, like memories, like ghosts

and I think about that all the fucking time

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

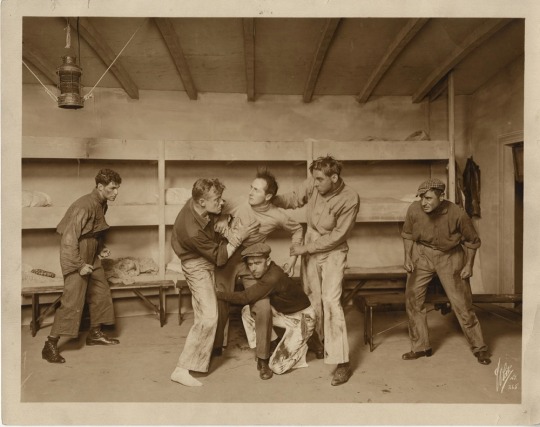

The Washington Square Players’ 1917 production of In the Zone, written by Eugene O’Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953).

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

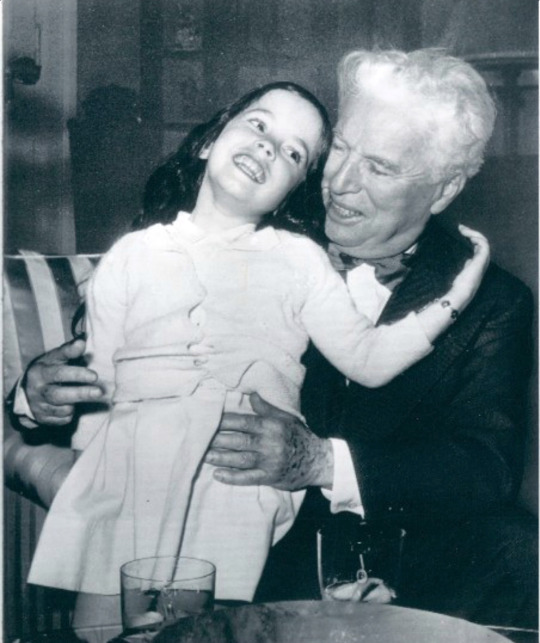

Sorry to hear of the passing of Josephine Hannah Chaplin (daughter of Charlie Chaplin) who passed July 13th 2023 at the age of 74.

Born in the U.S. 1949 the third of eight children to Charlie Chaplin and wife Oona, her maternal grandfather was Nobel Prize winning American playwright Eugene O'Neill. When she was three years old her father Charlie self-exiled to Switzerland. She made her film debut in father's film "Limelight" as well an appearance in "A Countess from Hong Kong".

Photo's:

#2 Charlie and Josephine Beverly Hills home 1952 (photographer W. Eugene Smith).

#3 "Limelight" 1952 Josephine in the middle with sister Geraldine and brother Michael.

#4 Charlie and Josephine 1954 home in Switzerland.

#5 Geraldine Chaplin (center) with sisters Josephine (to her right) and Victoria (to her left) home in Vevey, Switzerland 1954.

#6 Charlie and Josephine April 16th 1954.

#7 With father Charlie, Ireland circa 1965.

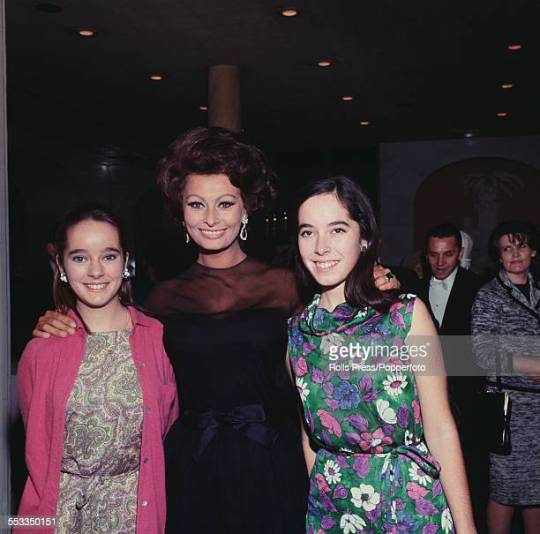

#8 Sophia Loren poses with Josephine Chaplin to her left and sister Victoria to her right, 1965.

#9 In "A Countess of Hong" Josephine (center) and sister Victoria (her left), 1967.

#11 Josephine and her father on her wedding day, 1969.

Her middle name for her grandmother Hannah Chaplin and I believe first name because of her father Charlie's fascination with Emperor Napoleon and Josephine Bonaparte.

#josephine hannah chaplin#rip#july 13th 2023#father#charlie chaplin#mother#oona o'neill chaplin#maternal grandfather#eugene o'neill

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

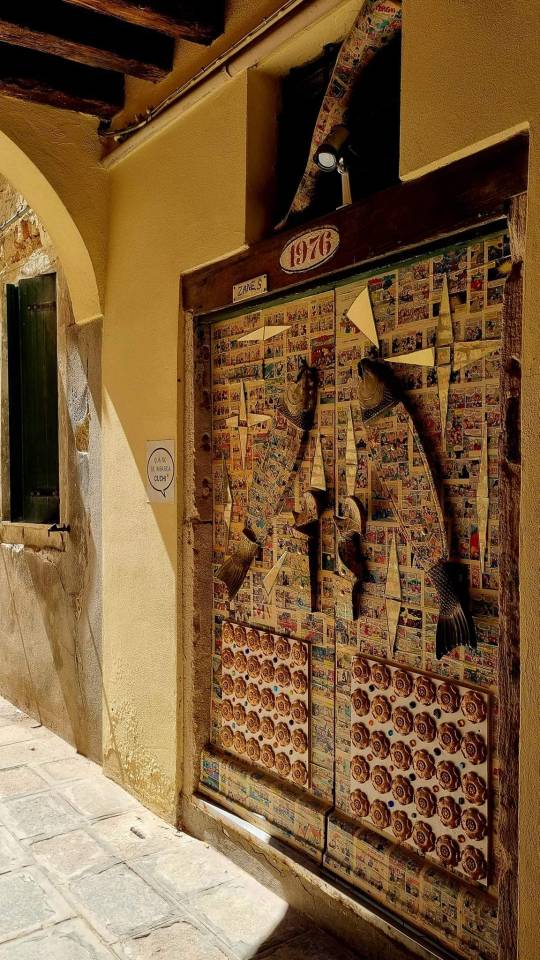

Obsessed by a fairy tale, we spend our lives searching for a magic door and a lost kingdom of peace.

// Eugene O’Neill

#venice#venezia#fairy tale#magic door#street photography#photography#travel photography#ph#eugene o'neill#quote#q#italy#italia

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Must-read plays for darkest academics *

• Prometheus Bound - Aeschylus (between • 479 BC - 424 BC)

• Phaedra - Seneca ( before 54 AD)

• The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus - Christopher Marlowe (1592)

• Hamlet - Shakespeare (between 1599-1601)

• Faust - Goethe (first part 1808, second part 1831)

• Cain - Lord Byron (1821)

• Ghosts - Henrik Ibsen (1881)

• Spring Awakening - Frank Wedekind (1890)

• The Living Corpse - Lev Tolstoy (1900)

• The Pelican - August Strindberg (1907)

• Mourning Becomes Electra - Eugene O'Neill (1931)

• Caligula - Albert Camus (1944)

*the years represent when the play was finished/published, not when it was performed for the first time

#plays#theatre#darkest academia#academia#academics#darkest academics#ancient theatre#ancient greeks#aeschylus#seneca#christofer marlowe#goethe#lord byron#leo tolstoy#henrik ibsen#august strindberg#albert camus#eugene o'neill#shakespeare#frank wedekind

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is no present or future, only the past, happening over and over again, now.

-Eugene O'Neill

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carlotta Monterey as Mary Blair and Louis Wolheim as Bob "Yank" Smith in The Hairy Ape, 1922. Monterey replaced Mildred Douglas and met playwright Eugene O'Neill during the production of "The Hairy Ape." She later married him.

Yank Smith is an engine stoker on an ocean liner, and very confident in his power over the ship's engines and his men. When passenger Mary Blair, the daughter of a wealthy industrialist, refers to him as a "hairy ape," he is first outraged, but then begins to brood over it and question his place in the world. He leaves the ship and wanders into Manhattan, only to find he does not belong anywhere—neither with the socialites on Fifth Avenue, nor with the labor organizers on the waterfront. In a fight for social belonging, Yank's mental state disintegrates into animalistic, and in the end he is defeated by an ape in which Yank's character has been reflected. The Hairy Ape is a portrayal of the impact industrialization and social class has on the dynamic character Yank.

In her review of the play Dorothy Parker wrote of "the power of this curious, brutal, fantastic play of the soul of a stoker. One is ashamed to place neat little bouquets of praise on this mighty conception of O'Neill's. It is like smiling tolerantly at the ocean, and saying, "Very pretty indeed."

Photo: MCNY

#vintage New York#1920s#Hairy Ape#The Hairy Ape#Eugene O'Neill#theater#Carlotta Monterey#Louis Wolheim#Dorothy Parker#vintage theater

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have had my dance with Folly, nor do I shirk the blame;

I have sipped the so-called Wine of Life and paid the price of shame;

But I know that I shall find surcease, the rest my spirit craves,

Where the rainbows play in the flying spray,

'Mid the keen salt kiss of the waves.

Eugene O'Neill

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

'I almost knock into Andrew Scott before I see him. He’s just dashed out of the Tate Modern, frantic and slightly late: “There’s just so many entrances!” he exclaims. His patrician forehead crinkles, and the brown eyes charmingly plead: Forgive me! He was just inside, picking up his membership card. Surely he can get in for free? “Excuse me,” he huffs, “I’m a fully paid-up member.” Then he flashes the broad grin that seduced a legion of Fleabag viewers, and we’re off.

The plan today is to meander in a loop along the Thames. On a midafternoon Friday in London, this involves much ducking and diving through crowds, which suits Scott just fine. The weather is one of those bright, springlike days that convinces you that winter is over—except the rain-swollen river is now sloshing ominously onto the pavement. We slow down to regard an underwater section of our route. “I don’t think we’re gonna get through there,” he says. “I’ve probably got a hole in my trainers.”

We head for the road instead, words pouring out of the 47-year-old actor in that mellifluous Irish lilt, peppered with “you knows” and interrupted frequently by his laugh. It’s no surprise that his colleagues quickly become friends: “It was clear from the moment that I met and worked with Andrew that he was an exceptionally gifted actor,” says Julianne Moore, who starred alongside Scott on Broadway in 2006’s The Vertical Hour. It was both actors’ Broadway debuts, though Scott has juggled screen and theater from the start. “I’ve always done both,” he says, though he acknowledges modestly: “I used to do maybe a few plays a year and one television show. Now maybe it’s kind of the opposite.” That’s somewhat underselling his dramatic accomplishments. Scott has won two Olivier Awards, for the experimental A Girl in a Car With a Man in 2005 and Noël Coward’s Present Laughter in 2020. He has performed in productions of Eugene O’Neill, Oscar Wilde—he’s played Hamlet, too, and was nominated for an Olivier for that as well. “Scott gives carefully controlled, thrillingly virtuoso physical performances,” wrote The Guardian last year, when he performed eight roles from Uncle Vanya by himself, in a much-lauded West End solo adaptation of the Chekhov play. (A New York transfer could not be confirmed when this piece went to press, but seems highly likely.) “He wore his talent so lightly and modestly,” Moore says. “He was joyful and fun and an amazing partner to have onstage and off.”

Scott was born in Dublin, sandwiched between two sisters; his mother is a teacher and an artist, and his father works at an employment agency. As a child, he was brought to art galleries and theaters. A performance by the great Irish actor Donal McCann in Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock when he was 11 or 12 made a lasting impression: “There was just something about the power in his stillness—people think that, in theater, it’s all about the grand gesture, but stillness onstage is absolutely mesmerizing.”

An eerie stillness characterizes all of Scott’s performances as well. As Moriarty in Sherlock, the BBC One show that catapulted him to fame in Britain in the 2010s, he requested fewer lines to play up the villain’s spookiness. And then there is that agonizing stretch of silence in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag right after its titular protagonist confesses her love. Has the line “It’ll pass” ever been delivered with so much pathos? Scott’s acting is all submerged passion; when he does speak, his words have depth. “Andrew has an intensity and a precision in his work,” Moore tells me. “I love his vulnerability, the way his eyes glitter onscreen.”

As a child, Scott was sent to drama classes to get over his shyness. He still remembers his first role, as the Tin Man in a production of The Wizard of Oz. “I felt completely free,” he says, seemingly transported to the moment he launched into “If I Only Had a Heart” onstage. “I felt joy—that’s the word. Not only did I feel it, but I felt that other people felt it when they were looking at me…. Some intuition told me as an 11-year-old: ‘You have to be this expressive, that’s what theater is!’ Nobody taught me that. I just felt it.” Then he swerves to avoid a clutch of tourists on Tower Bridge, and the reverie is lost.

These days, walking around London is something of an ongoing pastime for Scott. During the press rollout for Andrew Haigh’s Golden Globe–nominated romance All of Us Strangers, he and costar Paul Mescal went to their PR engagements on foot. One day, two boys on bikes clocked the pair and started chasing after them in an alarming fashion: “We escaped them—it was quite fun, actually!” Does he ever feel slightly protective of Mescal, two decades his junior? “Not any more than I would with any of my other people in my life. Because he’s got his head screwed on, you know? I absolutely adore Paul,” Scott adds, though he wants to make one thing clear: “Bromance is not the word that we associate with it, because neither of us are very bro-ey.”

Waller-Bridge, who has known Scott for 15 years, describes him as “an absolute pixie of mischief.” When asked to elaborate, she continues: “I could write a novel. But I love how naughty he is. He has the magical ability to make you feel instantly present—no matter what’s going on in your life, you’re suddenly there in the moment and feeling joyful. I think that’s what it’s like to watch him as an actor too…like he can stop time with his honesty.”

Between 2020 and 2021, Scott also traversed the lengths of the Thames, pondering the script from Ripley, his upcoming eight-episode project for Netflix, in which he plays the titular protagonist. “Quite unusually, I got sent all eight scripts at the same time,” he remembers. Steven Zaillian, the screenwriter behind Schindler’s List and Gangs of New York and the director and writer behind All the King’s Men, had written all eight at the outset.

Tom Ripley is crime novelist Patricia Highsmith’s slipperiest literary creation; a pathological liar and murderer with whom she felt a strange kinship—she sometimes signed letters with some variation of “Pat H., alias Ripley.” It is not so much a spoiler as an ongoing feature of the books that Ripley, despite splurging on Venetian palazzi and Gucci suitcases, never gets caught. If anybody comes close, there is always a conveniently located oar or glass paperweight nearby. Ripley, in other words, is the hero of the tale. “That’s why he fascinates so many,” says Scott. “There’s been so many iterations of him. I think it’s because people root for him.” Actors like Alain Delon and Dennis Hopper have tried the role; Matt Damon played him as an obsequious, lower-class naïf; John Malkovich, as a slimy, camp killer. Scott’s Ripley is different; a watchful loner escaping rodent-infested poverty, more at home among art than he is around people. Musician and actor Johnny Flynn plays his first victim—the monied Dickie Greenleaf—and Dakota Fanning is Dickie’s suspicious ex-girlfriend. “I find Tom quite vulnerable,” Scott tells me. “I don’t think he’s necessarily lonely, but I certainly think he’s solitary…. He seems to me by his nature that he just can’t fit in. He’s trying to survive.”

In Ripley, Zaillian extracts maximum Hitchcockian dread from every creaky footstep. But most sinister of all is Scott’s face, which exhibits a sharklike steeliness throughout. It’s a performance that exudes queasy force. Is Ripley a scammer, a psychopath, or both? “There’s so many things lurking beneath him that I’ve been very reluctant to diagnose him with anything. I never thought of him as a sociopath or murderous,” Scott declares. “It’s up to everybody else to characterize him or call him whatever they want.”

As we weave through tourists near the Tower of London, barely anybody notices Scott, save for a faint glimmer of recognition among mainly young women. He seems to draw reassurance from it. “I don’t like to think about it too much, if I’m honest,” he muses of fame. “I find it a little bit, er, frightening.” He is known but not blockbuster-recognizable, although he is in the upcoming Back in Action with Cameron Diaz and Jamie Foxx. What stunts did he do? “I can’t give that away, I’m afraid, or somebody from Netflix will come and shoot me in the head.”

What’s been on Scott’s mind the most hasn’t been acting at all, in fact, but art. As a 17-year-old, he was offered his first movie role on the same day he was given a scholarship to study painting. He chose acting, but has recently been thinking about Oliver Burkeman’s philosophical self-help tract from 2021, Four Thousand Weeks, which makes the case for focusing on the five things you truly want to accomplish. “For me at the moment, it’s like, What do you want to do? What do you want to say?”

He scrolls through his phone to show me his work. There’s a watercolor of a couple arguing in a restaurant in rich reds and greens, line drawings of friends and people on the beach, and two self-portraits. “It’s a bit weird,” he acknowledges of his depiction of himself, all bulbous forehead and Pan-like tufts of hair. His brisk, nervy lines are reminiscent of Egon Schiele or Francis Bacon, who turns out to be one of his favorite painters. “Well, God, I’ll take that,” he mutters at the comparison. He would like someday to go to art school. “I don’t ever regret it,” he says of acting. “But I suppose you just get to a stage where you think, What else? That’s one of the big painful things in life for me, where you can’t quite live all the lives.” As he gets older, he feels the tug toward revisiting old working relationships, including with Waller-Bridge: “We’ve definitely got things cooking,” he smiles. “I’d love to work with her again. She’s just a singular, wonderful person.” For her part, Waller-Bridge says: “I’d love to see him do a fully unhinged slapstick comedy character. Someone who is outraged at everything, all of the time.”

As we round the pavement and the Tate Modern looms back into sight, he recalls a poster he received in 2017—a monstrously large graphic that detailed every week in a human life span. “It’s your entire life if you live to 80—you have to fill in all the bits that you’ve already lived,” he remembers in awe, “a visually terrifying gift.” What did he do with it? “I didn’t hold on to it for too long.” Easy come, easy go: We finally finish our loop around the Thames and, as Scott disappears back into the throng, anonymous just the way he likes it, it occurs to me that the actor has many lives to live yet.'

#Andrew Scott#Fleabag#Hot Priest#The Vertical Hour#Julianne Moore#Patricia Highsmith#Netflix#Ripley#Back in Action#Jamie Foxx#Cameron Diaz#Tate Modern#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#A Girl in a Car with A Man#Noel Coward#Present Laughter#Broadway#Eugene O'Neill#Hamlet#Vanya#Chekhov#Oscar Wilde#Olivier Awards#Donal MaCann#Juno and the Paycock#Moriarty#Sherlock#Paul Mescal#All of Us Strangers#“If Only I Had A Heart”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jessica Lange, Paul Nicholls, and Paul Rudd in Long Day's Journey Into Night at the Lyric Theater in London, 2000

#jessica lange#paul nicholls#paul rudd#long day's journey into night#eugene o'neill#mary tyrone#edmund tyrone#jamie tyrone#lyric theater

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

“O’Neill demands so much. If you’re not giving everything or trying to fake it, it comes off as melodrama and could be cringe-worthy. It forces you to dig down. And some of the things that worked in show number five don’t work on show number 20. It’s like, ‘I gotta find a different part of my heart to break tonight.’ My body starts to build up a callus and I go, ‘I know what you’re trying to do to me. Let’s not go there.’ And I have to figure out a way around it.”

I just read The Iceman Cometh in two days and absolutely loved it. How I would give anything to see Austin as Don Parritt.

#austin butler#david morse#the iceman cometh#don parritt#larry slade#broadway#austin butler the iceman cometh#eugene o'neill

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eugene O'Neil, Playwright, 1926.

©E.O. Hoppé Estate Collection.

#long day's journey into night#eugene o'neill#playwright#writer#e o hoppe#the iceman cometh#1920s#moustache#mourning becomes electra

2 notes

·

View notes