#exoticization?? in MY native american heritage month???

Text

“He walks around half naked all the time so CLEARLY this is solely bc he’s meant to be a metaphor for Temptation” my good bitch do you know who you sound like

#exoticization?? in my native american heritage month???#it’s more likely than you think!#it’s also highkey FETISHIZATION#where is the righteously angry energy#when it’s indigenous peoples/characters being fetishized??#hmm???#musings#do not reblog

0 notes

Text

Slant’d: Interview with Allyson Escobar & Marion Aguas

Slant’d is a magazine, a media company and a stereotype flipped squarely on its head. Their work celebrates Asian American identity through personal storytelling and seeks to shatter stereotypes and redefine the APA experience. This month, we’re partnering with the self-professed #badasians to celebrate the release of Issue 02 of Slant’d with behind-the-scenes content from the hearts and minds behind the magazine.

For the first in the series, Slant’d invited Allyson Escobar — freelance journalist and only child of Filipino immigrants — and Marion Aguas, a New York City based photographer and artist, to discuss their joint piece, “When Life Was Fair.”

Both artists navigate and unpack the uncomfortable politics of colorism and privilege in the Filipino community, the global stigma against being darker-skinned, their perspectives on Asian American feminism, life after “Asian August” and their best advice for furthering our current civil rights movement.

Slant’d: For those unfamiliar with you and your work, tell us about yourselves.

Allyson: I’m a freelance journalist and L.A. transplant living in New York City, currently finishing my degree at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism. I’ve covered race, religion, immigration, arts and culture and more, for a variety of local and national publications, including Filipino publications. I’m passionate about writing about people of color — particularly the Asian American community — whose issues and stories I feel often go unreported or misrepresented. I love seeing our community represented in media, both news and entertainment, and seeing us rise in that way.

Marion: I am a freelance photographer so my job is different every day. Sometimes I’m working on straightforward e-commerce projects, and sometimes I get to play dress up on fashion shoots. I’m also very passionate about Asian American representation. In my personal work, I try to make sure to center Asian Americans and their stories. Too often, I see Asian culture still being exoticized, being used to “other” us but not see us. I think it’s important for Asian Americans to represent ourselves in media so that we can give truth to the nuance in our experiences.

We hear you on that! That is the very basis of why we started Slant’d — to illuminate the true, untold and diverse stories of real Asian Americans. Speaking of, how did you come to get involved with Issue 02 of Slant’d?

Allyson: I’m a member of the Asian American Journalists Association, which supports and does a lot of community outreach with Slant’d. I followed Slant’d soon after hearing about the company’s ideals, which I so resonate with, and reached out upon seeing their call for writers’ submissions for Issue 02.

Marion: I responded to the open call for Issue 02. I actually submitted a different pitch, which didn’t work out, but then got invited to do photos to go with Allyson’s piece!

There you go! These next two questions are for Allyson. Your piece sheds light on colorism and explores everything from your personal experiences growing up as a light-skinned Filipina, to the colonial roots of colorism, to its modern day impact on the skincare industry. What compelled you to write this piece?

Allyson: Growing up a light-skinned, “mestiza”-looking Filipina, I’ve often been mistaken for Chinese or Korean because of my skin tone and my straight, jet black hair. [Editor’s Note: “Mestiza” refers to a woman of mixed race, particularly the mixed ancestry of white European and Native American from Latin America.] My mom used to give me “whitening" cream skin products, or tell me constantly to not stay in the sun too long, “for fear of getting dark.” This is, sadly, an all-too-common story in Filipino households, an issue that affects both women and men.

Brownness has a huge cultural stigma, deeply rooted in the long history of Spanish and U.S. colonialism in the Philippines, and the negative connotations that come with being “dark” are still very much alive. Both the Philippines and many Asian cultures traditionally celebrate lightness, in a not-so-subtle way: from the highly-praised “mestiza”— many biracial actresses I grew up seeing on TV shows and comparing myself to — to the lucrative “whitening" skin products I see stocked on the shelves of bathrooms in Asian households. These issues don’t often get covered, and I wanted to write a piece highlighting both colorism’s history and its modern-day widespread impact, while celebrating the beauty of all colors and skin tones.

And what do you hope readers take away from your piece?

Allyson: I want issues of colorism to be more widely discussed, especially in the skincare industry and within families, and for readers to recognize that beauty is beyond skin deep. I want to celebrate men and women in their darkness and lightness, all skin tones and shades, because the world too often tells us to “cover up” what it sees as “flaws.” Colorism is as serious of an issue as racism and sexism, and I hope my piece sheds light on the Filipino American experience of that.

Amazing. Switching focus to the other half of this dynamic duo — Marion, you created the stunning, artistic photographs to accompany Allyson’s writing. What was your process like for creating this art?

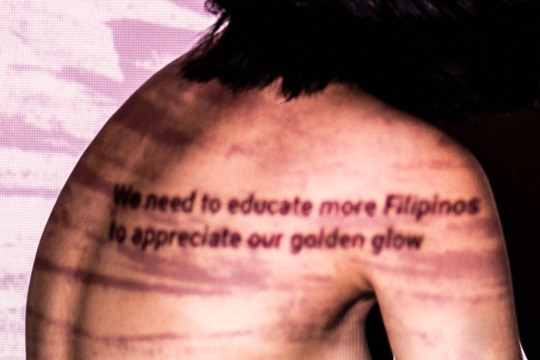

Marion: Allyson’s article really resonated with me, as I am also a light-skinned Filipinx. At first, I wanted to go really hard into the Filipino-specific references but after talking to Allyson about the article, she reminded me that colorism affects more than just Filipinos. So I thought more about how to use more universal imagery that could work as projections.

Tell us more about the final photographs — what is the inspiration behind them, and what are you hoping to portray?

Marion: I had been ruminating on what it means for me to navigate the world as a POC, but one with the privilege of my skin color. The compliments I get, especially from Filipinos and other Asians, about how beautiful my skin is, has always made me feel uncomfortable and I realized it’s because it’s a compliment that I haven’t earned through my actions, but one born out of luck.

My skin color tells the story of colonization. It tells me that somewhere in my family tree, a Spanish person had a child with (or maybe raped, let’s be real) one of my family members and my bloodline now has the genes for a lighter skin color. That’s how I thought about the projections I used in the photographs — I wanted to use my skin as a canvas for the projections to further help tell the story of my people’s history and the story of my lived experiences.

It seems like you’re both involved with shaping the conversation around Asian American feminism. What does Asian American feminism mean to you?

Marion: I think it is a perfect example of what intersectional feminism can look like. We can’t forget that feminism is rooted in a history and defined by a specific set of political ideologies that strive to establish equality amongst the entire gender spectrum. We have to remember that Asian Americans have a lot of privilege within the landscape of American politics. Within our own communities, there is a lot that we need to do to recognize the privileges between East Asians vs. South Asians. Asian American feminism, to me, is learning to understand where my privileges begin and end in order to learn how to center my needs vs. the needs of others and using my privileges to speak up for those who cannot.

Allyson: To me, “Asian American feminism” is straight feminism — which is being pro-human, pro-people, speaking out and standing up for their rights and equalities, checking our privileges and respecting people’s boundaries and also simply supporting and being there for one another. It’s recognizing the flaws and differences in people and finding a way to love them anyway. To me, feminism can be both loud and outspoken, but it can also be much quieter — like being a hand to hold, or a shoulder to cry on — and recognizing the needs of others. And that’s okay too.

How do you see this movement evolving and growing? What can people to do further the conversation?

Marion: I think it’s definitely growing! I see way more Asian American and Asian artists, actors, comedians, storytellers really representing our stories in the best way. And once we start seeing more Asians in the media, this will help the ripple effect that will encourage others to follow their own dreams in storytelling fields. I want to help dispel the obvious stereotypes: that we’re all good at math, that we’re quiet and shy and obedient. Within the queer experience, I want to dispel the idea that dealing with queerness within our families always has trauma associated with it. I’m also seeing more Asian American collectives starting to join forces and work with other black and POC collectives, which I think is important. Until we see more of that, we cannot be a united front. In terms of furthering the movement, we can ask our friends to stand up for us, to help us do the work. To speak up when they hear stereotypes or microaggressions and help amplify our voices as well.

Allyson: I think that, by speaking and standing for others, we are supporting the movement. We also need to show up — at our community events, at the polls, at the movies highlighting diversity and proper representation, etc. These are our platforms, our world stages. By telling our stories and being open-minded with one another, listening to different viewpoints and ideas, we can also have better, more mindful, impactful conversations. We just need to extend the invitation.

What’s top of mind for you right now within the Asian American movement?

Marion: My main focus is really about decolonization. It is a personal battle for me: to decolonize my heritage, reclaim my cultural identity and understand its indigenous roots. I want to further this work by properly representing my story instead of leaving it to others so that I can create a ripple effect that encourages others to also decolonize their spaces. I’m learning more about Asian American activists and their involvement in the civil rights movement. I think there’s a lot to learn, especially about intersectionality, from leaders like Yuri Kochiyama and how she used her voice to speak for all marginalized Americans. I also want to learn more about Asian immigration. I don’t know enough about Asian illegal immigrants and their struggles.

Allyson: I love what’s happening right now with representation in entertainment in our community, especially all the hype after “Asian August;” with the release of Crazy Rich Asians, Searching and Netflix’s To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before. Even kids’ shows like Disney’s Andi Mack are breaking ground, as all of these stories and creators are increasing visibility for the larger Asian American community. I do hope to see more brownness, especially South Asian cultures, represented properly in mainstream media and entertainment.

What’s next for both of you?

Marion: I’m going to keep working! I have a portrait series that is ongoing and hope to get published. I want to keep meeting and working with the queer Asian American community to create beautiful and weird work. I’m exploring incorporating text and video to help tell my story.

Allyson: I’m graduating journalism school in December, and hope to still be telling impactful, inspiring stories until my hands fall off.

To see Allyson and Marion’s work in Issue 02 of Slant’d, pre-order your copy here.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

#slant'd#asian american#colorism#filipino american#aapi#allyson escobar#marion aguas#ace hotel#ace hotel new york#apa#asian american feminism#representation#magazine#yes#interview#badasians

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Markedly Worse Than Expected

by Dan H

Sunday, 27 February 2011

Dan really disliked Marked~

As Ferretbrain enters its fifth year (have we really been doing this for that long?) I sometimes fear that our articles in general – and my articles in particular – have become too self-referential. This is especially true given that recently most of what I have been reading has been books that were voted off from our recent

TeXt Factor Special

.

Six months or so on, I'm still rather pleased with the way the original TeXt Factor turned out – while the whole premise is clearly stupid, every time I've actually tried to finish one of the books we voted out (at least, one of the books we voted out before the point where everything got quite good) I've felt that the experience thoroughly vindicated our original decision to just stop reading the damned thing.

This was certainly true of Marked.

We voted off Marked in

the first round of the Halloween Special

for a variety of reasons, mostly that its protagonist was a horrible, horrible person and that all the stuff about the heroine's “Cherokee ancestry” felt like a big pit of terrible fail waiting to happen.

We were basically right.

Faint Praise

A friend of mine used to have a saying which he used to employ in order to acknowledge the fact that something which he felt was utterly without merit presumably had some value to other people. He would say: “For people who like that sort of thing, that is the sort of thing that they like.”

This is about the limit of my ability to praise the (apparently very popular) Marked. I can see how it would appeal to certain types of person in certain types of ways. Unfortunately the type of person is “horrible people” and the method of appeal is “by playing on their worst and most selfish instincts.”

Okay, this is an overstatement, but basically Marked is written in the voice (and presumably for a target audience) of a teenage girl who is unbelievably selfish, utterly judgemental, hates everybody who is not part of her immediate social circle, and who believes (it seems quite justifiably) that she is the centre of the entire universe. This is not necessarily a problem in itself – it is perfectly reasonable for books to have unsympathetic protagonists, and as an evocation of a particular kind of thoroughly horrible teenager Marked succeeds admirably – the problem is that the protagonist's repugnant qualities are routinely vindicated by the world in which she lives, and frequently lauded as virtues (particularly her harsh and incessant condemnation of girls she considers “sluts”).

Identity and Appropriation

An area of American race politics about which I know absolutely nothing, and which I would not under ideal circumstances touch with a barge pole, is the question of who is and is not entitled to legitimately identify as Native American.

To present a broad, oversimplistic view of a complicated situation, there are a lot of white people in America who unreasonably appropriate Native American culture and identity, often on the basis of a spurious blood connection (“I'm one-seventeenth Cherokee!”), people also often use this sort of iffy cultural appropriation to excuse other sorts of crappy behaviour (“I'm one-seventeenth Cherokee therefore nothing I say can ever be construed as racist”).

Where it gets more complicated (and I am aware that it gets vastly more complicated, and that this is still an oversimplification of the complexity of the whole thing) is that there are plenty of people who genuinely are “one sixteenth Cherokee” and whose claim to a Native American cultural heritage is never the less completely sound. Not all Native Americans live on reservations or run casinos. It is very tempting for people like me to assume that if somebody lives a life which is more or less the same as my own, that said person cannot be a “real” Native American – this of course is actually a form of subconscious racism, it is easy for me to assume that all Native Americans live picturebook lives of harmony with nature and genteel poverty, when in fact they're twenty-first century people just like me.

Now the thing is, I do think that the way in which “Zoey Redbird” identifies with the Cherokee people in Marked actually does fall into the category of skeevy cultural appropriation but I am very very conscious that I am in danger of dismissing somebody's real and genuine cultural identity just because they don't fit my personal stereotype of a member of their race.

So to start off with, here are some things which I don't think cause a problem, even though they might seem to.

I do not think it is a problem that Zoey passes as white. A lot of Native Americans do.

I do not think it is a problem that Zoey is essentially a normal American teenager. It is extraordinarily important to remember that Native Americans are not some kind of fantasy race, they're real people. I am absolutely certain that there are sixteen year old Cherokee girls who read Gossip Girl and had crushes on Leonardo di Caprio.

I do not think it is a problem that Zoey moves freely between two cultures, taking the elements she likes from both. A person of mixed cultural and racial heritage has a complete right to all of the elements that make up their identity, not just the minority part.

Finally, I do not think that it is a problem that, looking at the photograph in the back of the book, P.C. and Kristin Cast don't “look” Native American. This is true for two reasons. Firstly, pursuant to my first point above, it's possible that they're actually genuinely from a Native American cultural background, and just happen to have relatively pale skin. Secondly, as ever authorial intent is not a major concern. Even if P.C. And Kristin Cast are presenting a cultural identity to which they have a legitimate claim, they might still be doing it in a way which feels like or encourages appropriation of that culture.

Here are the things that do make me think that the Native American elements in Marked can be read as skeevy cultural appropriation:

Firstly, Zoey's Native American heritage is exclusively associated with magic, mysticism and the supernatural. Her one link to that part of her heritage is her Grandmother, who runs a lavender farm and is part of a long line of Cherokee wise women. Zoey is, of course, the natural heir to that power. Her Grandmother is also, for some reason, entirely au fait with and accepted at the House of Night, which is otherwise extremely dismissive of humans. Zoey's Cherokee heritage is routinely cast as part of the same world as the vampires. Although in this world the vampires are clearly the cool, sexy, interesting people and we are supposed to sympathise with them they are still ultimately not human. Although the series (being very much a teen-angst Family Romance) takes a very dim view of humans in general, that does not really make it okay to put “humans” in one box and “Native Americans” in another

On a second, related note, the spiritual beliefs of the Cherokee people (to which Zoey is heir, and for which she feels a strong affinity) are presented as compatible (and at times interchangeable) with the clearly Wiccan-derived beliefs of the House of Night. The vampyre rituals which involve drawing pentagrams, calling the corners, and raising the four elements are presented as blending seamlessly with Zoey's grandmother's traditional cultural practices, despite the fact that pentagrams and a four-element cosmology are strictly European cultural artefacts. It even declares that the Greek Goddess Nyx is one and the same as Grandmother Spider which, well I don't actually know enough about either figure to tell you the differences or similarities, but we're dealing with figures from completely different mythologies – I strongly suspect that saying “Nyx is also Grandmother Spider” on the basis of their both being female deities with an association with night is sort of like saying “Jesus is also Eros” on the basis of their being male deities who have an association with love. It all combines to create the strong impression that Marked uses Cherokee culture as a source of cool special effects and exciting mystical sounding ideas, rather than as something that real people really believe in.

The third thing that pushes my skeeve buttons regarding Zoey's Native American identification is that her “Cherokee features” are always exaggerated by her vampirism. Zoey is always at her most Cherokee when she is at her most inhuman, her most exotic, her most unnatural.

To put it another way, there is never any sense that Zoey's Cherokee heritage is just a part of her, it is never something she just takes for granted as part of her cultural background. It is always presented as something alien, exotic, and mystical. Now I recognise that this could be seen as a realistic portrayal of a sixteen year old girl. It's possible that if you were sixteen and felt like an outsider as many do, that you would fixate on a part of your background that you perceived as mysterious and exotic and would exaggerate the mystery and exoticism of it. On the other hand the rest of the world reinforces this creepy Othering of Cherokee culture – Zoey's heritage really does give her magic powers, her Grandmother obviously feels Zoey really gets it, and of course no amount of subjectivity on the part of the narrator can explain why Cherokee spiritual beliefs are suddenly so compatible with Wicca.

I've spent a really long time talking about this, which is ironic because it's not actually the thing I found the most annoying.

Ain't Shit But Ho's and Tricks

I spend a lot of time on FB dissing people for being sexist. Usually I'm on (comparatively) safe ground because the people I'm dissing are men, and usually what I'm saying is something like “I think this author is being sexist in this way, and I think I can recognise it because I think they are indulging in a sexist impulse which I sometimes recognise in myself.”

I find myself in a difficult position with Marked in that I find its portrayal of women and girls extremely troubling, but am naturally a bit leery of saying “hey, you women are writing about women wrong! Let my penis explain why!” On the other hand, the whole book is full of creepy gender-essentialism and slut-shaming and it's important to recognise that women can be sexists too.

In the first episode of the TeXt Factor Halloween Special, Kyra observed that the thing about Marked was that it really did feel like it was written by a Mom-and-Daughter team, in that it often used very teenage language to express very adult concepts. To put it another way, Zoey reads like a teenage girl who has totally internalised the preconceptions and prejudices of her slightly creepy, more-conservative-than-she-thinks-she-is, sex-negative mother.

So we keep getting lines like:

Did you know that your oldest daughter has turned into a sneaky, spoiled slut who's screwed half the football team?

Kinda like those girls who have sex with everyone and think they're not going to get pregnant or a really nasty STD that eats your brains and stuff. Well, we'll see in ten years, won't we?

Of course there are girls who think it's 'cool' to give guys head. Uh, they're wrong, those of us with functioning brains know it is not cool to be used like that.

Tucked into her countrified jeans was a black, long-sleeved cotton blouse that had the expensive look of something you'd find at Saks or Neiman Marcus versus the cheaper see-through shirts that overpriced Abercrombie tries to make us believe aren't slutty.

And that's from the first ninety pages.

Now I don't want to get too far up on my Minority Warrior horse here, I don't want to say “this book is harmful to young women” or “this book is actively immoral” or anything but as the book progresses it does seem to send profoundly unhelpful and contradictory messages to its primary audience.

The vampyres of the House of Night have a matriarchal society (although it seems to be grounded in some distinctly patriarchal ideas), and the vast majority of the adult vampyres we encounter in the book are female, and every single one of them is drop-dead gorgeous and incredibly sexually alluring, and their sexual allure is held up as something to aspire to.

For example, here is the description of the Vampire High Priestess Neferet:

She was movie-star beautiful, Barbie beautiful. I'd never seen anyone up close who was so perfect. She had huge, almond-shaped eyes that were a deep, mossy green. Her face was an almost perfect heart and her skin was that kind of flawless creaminess that you see on TV. Her hair was a deep red – not that horrid carrot-top orange red or the washed-out blond-red but a dark, glossy auburn that fell in heavy waves well past her shoulders.

I'm breaking this up here mostly to draw attention to the next line, but while I'm adding filler text, I'll just quickly ask: what the hell is up with “almond-shaped eyes”, it's used everywhere but seriously what the hell other shape are eyes supposed to be?

Anyway, the description continues thus:

Her body was, well, perfect. She wasn't thin like the freak girls who puked and starved themselves into whatever they thought was Paris Hilton chic … This woman's body was perfect because she was strong, but curvy. And she had great boobs.

So having just spent half a page describing this woman who fits exactly into an unrealistic, unattainable beauty standard and how amazingly wonderful and gorgeous this makes her and how girls can and should aspire to look like her, she then takes a random sideswipe at girls who aspire to a slightly different beauty standard.

Now just to be clear, I am not complaining that Zoey is not in favour of anorexia. Eating disorders are bad and people who have them need help, not condemnation (I'm not going to get into the whole pro-ana thing here). But Zoey doesn't say “this woman was beautiful because she was confident in her own body, unlike those girls who feel so much pressure to conform to other people's ideas that they puke and starve themselves.” No she says as an objective statement: This Woman's Body Was Perfect. I know we don't get much detail about Neferet's figure, but we aretold that she's “Barbie beautiful” which combined with “strong but curvy” implies fairly strongly that she looks more like Christina Hendricks than Amber Riley.

When Zoey talks about “those freak girls who puked and starved themselves” it sounds a lot like as if she is criticising aims rather than methods. Certainly she is extremely critical of the (one or two) fat people she meets in the book so her issue is clearly not with people trying to lose weight. The problem with “those freak girls” is not that they're trying to make themselves thinner (that's only sensible) it's that they're doing it in order to look like Paris Hilton, instead of like a “real” woman.

I should probably take a step back here and say a couple of things (the second being, in part, a counterpoint to the first). The first thing I should say is that it is possible that the House of Night series is actually being extraordinarily subtle and sophisticated, and that all of these examples of Zoey being judgemental about other girls are going to be shown to be false and hypocritical in future volumes, but I sincerely doubt it.

This brings me to my second point, which is that I can absolutely see where a lot of the problems with this book come from. If I was a mother, trying to write a Young Adult book with the help of my teenage daughter, I would almost certainly wind up putting these kinds of messages into the book in the honest belief that I was setting a positive example for young girls. A lot of Zoey's most hateful pronouncements feel like the kinds of half-truths that a well-meaning parent would tell their daughter in order to help her more-or-less get by in the complicated world of adolescence. If you're trying to explain to your fifteen year old about oral sex, I suspect most parents given the choice between:

“It has lower risk than vaginal or anal sex, but you can still contract most sexually transmitted diseases, if you try it and find you don't like it then stop and don't let anybody make you feel you have to, on the other hand if you find you get pleasure out of it then as long as you're aware of the risks then it's alright, and doing it won't make you a bad person. And remember that just because you give a guy a blowjob it doesn't mean you have to have sex with him, but also remember that guys might not see things the same way, most importantly remember that nobody has the right to control what happens to your body except you”

and

“Girls who do that are stupid and have no self-respect.”

most would choose the latter. Most mothers, I suspect, would far rather tell their daughters that oral sex was something only bad girls did than have to have a conversation about what spunk tastes like. Then there's the risk analysis element: from a perfectly understandable perspective, if you tell your kid that it's okay to enjoy giving head, then the worst case scenario is that she dies of a sex-disease. If you tell her it's not okay to enjoy giving head, then the worst case scenario is that she misses out on something she might have found sexually fulfilling. I can absolutely see why, if you were a parent, you would want your little girl to grow up thinking like Zoey.

The problem, of course, is that it just doesn't work that way. Teaching your children to be frightened or ashamed of sex doesn't, in practice, stop them from having it (the waters are muddied here by the fact that actually a lot of teenagers – by accident or design – avoid sex anyway) what it does is make the sex they do have less safe, both physically and psychologically.

But I digress.

In the latter half of the book, most of Zoey's ire is directed at Aphrodite. To be fair, Aphrodite is a horrible person (although she's kind of made of straw – like most school-story rivals her role is to be a threat to the heroine even though the heroine is superior to her in every way). When we first meet Aphrodite, she is trying to give a guy a blowjob. This is evidence that she is a terrible person. Pretty much the whole of the rest of the book is devoted to the systematic observation that Aphrodite is evil, and therefore a whore, and therefore more evil. She pretty much never appears on the page without Zoey having some criticism of her sexual conduct: her boobs are too big, her lips are too red, she moves her hips too much when she dances.

It is worth remembering that all of this is set against the background of a supposedly matriarchal society. The book makes a great play of the fact that it is women who rule the world of the vampyres, but their matriarchal culture seems grounded in patriarchal assumptions about gender roles. So yes, the priestesses are in charge, but all of the warriors are males, because Male Vampires Are The Protectors (this is stated very explicitly, at least three times) and while the book is very big on Goddess Worship and feminine imagery and The Almighty Power of Womanhood, it does this by presenting a very specific, very conservative, and very contradictory idea of what it means to be a woman.

So all of the adult vampires are presented as beautiful and sexy and confident and powerful, but Aphrodite is condemned for being the wrong sort of beautiful and the wrong sort of sexy and the wrong sort of confident and the wrong sort of powerful. The whole book is a study in the fucked up, contradictory rules that young people, particularly young women are brought up with. You mustn't be fat, but you have to have curves. You have to be sexy, but you can't want sex. Boys have to want you, but can't think they can have you. You have to be strong and clever, but not too strong and too clever, and not too ambitious. You can be beautiful and terrible and powerful and unbeatable, but your role will always be to serve others, and no matter how much power you have, you must leave your protection in the hands of the males, because they have their role just as you have yours.

Cultural appropriation and horrible gender-fail aside, the book is also just shoddily paced. Like a depressing number of these books, the heroine is such a complete Mary Sue that the only real tension is exactly when she will employ her effectively unlimited power to solve whatever the current problem is. Marked sets up quite an interesting plotline involving students dying and coming back as evil spirits, but it only kicks off in the last third and is clearly intended as the metaplot of the entire series. So the climax of Marked is just Zoey's showdown with Aphrodite, except that Zoey has near-unlimited supernatural power, and has the actual high Priestess of Nyx on her side, so in the end you wind up feeling kind of sorry for Aphrodite who, in a certain sense, just gets bullied mercilessly by the asshole protagonist and half the teaching staff.

Indeed you can sort of see the final confrontation as a microcosm for everything that is wrong with the book. In theory, Zoey is supposed to be the plucky underdog going up against the socially and supernaturally superior Aphrodite. In fact the reverse is true. Everybody hates Aphrodite (because she's an evil bitch whore slut whore bitch hag slut whore), the entire teaching faculty and the Goddess Nyx Herself have outright stated that Zoey is all that and a bag of chips. So what casts itself as an inspiring tale of triumph over adversity is really the story of somebody with every conceivable advantage stomping over somebody who does not have those advantages. In much the same way, the book casts itself as being this subversive, anti-authoritarian text (it spends a lot of time condemning the People of the Faith for their hypocritical, controlling natures and there's a particularly galling bit where Zoey “I Hate Sluts” Redbird goes on about how much she hates closed-minded people) when it actually just reinforces a lot of deeply conservative, borderline harmful ideas.

So yeah. One to avoid maybe.Themes:

Books

,

Sci-fi / Fantasy

,

Young Adult / Children

,

Judging Books By Their Covers

~

bookmark this with - facebook - delicious - digg - stumbleupon - reddit

~Comments (

go to latest

)

Melissa G.

at 17:59 on 2011-02-27Thanks for slogging through this for me, Dan! I almost want to read it for how bad I know it will be, but I can't quite manage to put my brain through such torture.

My only knowledge of the House of Night series comes from the few chapters of the fifth book that I read with my student. At this point, Zoey's special snowflake-ness is of epic proportions. She has all these tattoos now, which no one has ever had before OMGWTFBBQ!? She's so special it hurts, and not just that, it seems like she knows she's special and Better than You and thus goes around with this air of superiority.

And, dude, poor Aphrodite. It's like her character is constantly getting shat on by the author despite the fact that she is no threat at all anymore and that at this point she and Zoey are FRIENDS. She's been completely de-powered at this point (she is human now, what?), and it just seems like the author keeps taking potshots at her as she's trying desperately to crawl out of range. It's just painful to watch.

Moving on, the fifth book has a lot more sex/sexual situations in it between Zoey and Erik, and I actually found it almost too sexual for a teen book. But perhaps that's me being prude. Shrug. Might also be noteworthy to mention that Zoey lost her virginity to not-her-boyfriend because he magically seduced her or something, which is all kinds of annoying to me, because it's not HER fault she lost her virginity to another guy. I mean, god forbid she just make an actual mistake and have to take real responsibility for it. But no, we'll just make it someone else's fault.

Also from the fifth book on the subject of race fail, a character named Kramisha gets introduced. Kramisha is the very epitome of the sassy black girl stereotype. She talks with poor grammar and outdated black slang, and she's all sassy and confrontational. And you can argue that these kinds of black people do exist in real life and there's nothing inherently wrong with it, but from what I can tell, Kramisha is the only black character around so it's a little unsettling that she's so cartoonishly stereotypical.

We also have token gays!! And they spend all their time talking about being gay, and how being gay means they know how to cook, and how they watch Project Runway (because, you see, they're gay), and how they know about interior design because they're gay, and gay gay gay gay gay gay gay gay. I think you get my point. It's just a bit much. Let them have another character trait. Really, it'll be fine. Also, one of them was described as walking in the room "[screaming] like a girl" and fainting. Fantastic. This is one of those "get off my side" things, as far as I'm concerned.

Anyway, that was my rant. And granted, I haven't read much of the book (not to mention it was the fifth one) so my complaints may not be entirely grounded, but these were my impressions. And I really can't bring myself to read another word of it because it's just garbage. For so many reasons.

permalink

-

go to top

Dan H

at 19:49 on 2011-02-27

At this point, Zoey's special snowflake-ness is of epic proportions. She has all these tattoos now, which no one has ever had before OMGWTFBBQ!?

Yeah, she gets a lot of those at the end of book one (tattoos seem to magically appear on Vampyres as a consequence of their utter awesomeness, although I'm not really sure it counts as a tattoo if it occurs naturally, isn't that just your skin?)

The super-specialness starts out pretty unbelievably insane in the first book and sounds like it only gets worse. In book one we discover that Zoey not only has powers of a variety which are normally only developed by adult vampires, but that her powers are also stronger and greater in number. Basically all adult vampires get a supernatural power called an "affinity", and very rarely they might get an "affinity" for one of the five elements, even more rarely they might have an "affinity" for two or more elements. Zoey of course has an affinity for all five elements (Earth, Air, Fire, Water and Spirit) already and this has NEVER HAPPENED BEFORE IN HISTORY EVER.

Moving on, the fifth book has a lot more sex/sexual situations in it between Zoey and Erik, and I actually found it almost too sexual for a teen book. But perhaps that's me being prude.

I suspect that's one of those YMMV things. I'm personally okay with sex in teen books: I mean they're already saturated in sexual imagery, and I'd kind of rather they were honest about it. Does she at least stop being so judgmental about other girls' sexual behaviour?

Might also be noteworthy to mention that Zoey lost her virginity to not-her-boyfriend because he magically seduced her or something, which is all kinds of annoying to me, because it's not HER fault she lost her virginity to another guy.

I think what would annoy me more in this situation would be if she lost her virginity to another guy because of being magically seduced, and the book didn't flag up that this was, y'know, date rape. Annoying as "I cheated on my boyfriend but it is okay because it was MAGIC" is, it's somewhat less annoying than "I was magically coerced into having sex with a guy, and the only thing that matters about this fact is that it was unfair to my boyfriend because he didn't get to take my virginity."

Also from the fifth book on the subject of race fail, a character named Kramisha gets introduced. Kramisha is the very epitome of the sassy black girl stereotype ... from what I can tell, Kramisha is the only black character around so it's a little unsettling that she's so cartoonishly stereotypical.

I believe that Shaunee (if she's still in it) is black as well, as is one of Aphrodite's minions (although I believe the text describes her as "obviously mixed" - because you can totally tell whether somebody is mixed-race just by looking at them).

We also have token gays!!

Ah, Token Gay is also in the first book (Damien, yeah). To be fair they get some points for allowing the guy to have an actual relationship, although they lose them again for taking the "gays = women (= gender-essentialist stereotypes of feminine behaviour)" angle.

I suspect that a lot of the tokenism actually comes about as a result of everybody except Zoey being an entirely one-dimensional character who exists solely to tell her how awesome she is (or to tell her that she isn't awesome and be proven TOTALLY WRONG).

permalink

-

go to top

Melissa G.

at 20:57 on 2011-02-27

The super-specialness starts out pretty unbelievably insane in the first book and sounds like it only gets worse.

Yeah, I forgot to mention the bit where her dream with Kalona (which is not really a dream) tells us that she's the reincarnated form of Kalona's lover/person who sealed him away. The Mary Sue-ness is mind-boggling.

Does she at least stop being so judgmental about other girls' sexual behaviour?

I didn't notice anything blatant, but I wasn't really looking for it. And I don't feel like going back and checking. :-)

I think what would annoy me more in this situation would be if she lost her virginity to another guy because of being magically seduced, and the book didn't flag up that this was, y'know, date rape.

I'm not sure how it was handled exactly because it happened in the book previous to the one I was reading. But I think it was considered to be sort of date rapey. All I know is that's why she and her boyfriend broke up, and it's made her feel sort of hesitant about having sex again.

I think the sex aspect might have bothered me more because it sounds like an adult writing a sex scene in an adult way that just happens to have teenagers in it. If that makes sense. It felt much like romance novel writing, which there isn't anything wrong with but it turns the sexual situations into fantasies rather than what I would feel is a realistic description of a teenage relationship. But as you said, YMMV.

I believe that Shaunee (if she's still in it) is black as well,

Oh, right, I forgot about her! Fair point. The fifth book kind of just kept lumping new characters and old characters on me from the second chapter on so it was hard to keep them all straight.

I suspect that a lot of the tokenism actually comes about as a result of everybody except Zoey being an entirely one-dimensional character who exists solely to tell her how awesome she is (or to tell her that she isn't awesome and be proven TOTALLY WRONG).

Yes. This. So much.

permalink

-

go to top

Dan H

at 21:59 on 2011-02-27

Yeah, I forgot to mention the bit where her dream with Kalona (which is not really a dream) tells us that she's the reincarnated form of Kalona's lover/person who sealed him away. The Mary Sue-ness is mind-boggling.

I don't think Kalona's shown up yet.

I think the sex aspect might have bothered me more because it sounds like an adult writing a sex scene in an adult way that just happens to have teenagers in it.

I think I see what you're saying, although I doubt I'll read further to see for myself.

permalink

-

go to top

Melissa G.

at 22:05 on 2011-02-27

I don't think Kalona's shown up yet

Kalona is a scary powerful God-like dude that got released in the fourth book. He's the big bad for the rest of the series, I think, and of course he's obsessed with Zoey.

Apologies for spoilers, but I don't think anyone cares?

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 11:24 on 2011-03-01If anything this review just validates our joint decision NOT TO READ THE DAMN THING.

permalink

-

go to top

Robinson L

at 21:06 on 2011-03-25

If I was a mother, trying to write a Young Adult book with the help of my teenage daughter, I would almost certainly wind up putting these kinds of messages into the book in the honest belief that I was setting a positive example for young girls.

You know, the more I grow up, the more I fortunate my sisters and I are to have such freaking amazing parents.

permalink

-

go to top

0 notes

Text

Hyperallergic: A Critical Understanding of Edward Curtis’s Photos of Native American Culture

Plate from The North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis at the Muskegon Museum of Art (all images by the author for Hyperallergic)

MUSKEGON, Mich. — Can one come to a revelation through a visit to an art museum, or is it something that can only be arrived at through a more intensive personal journey? This is the question that emerged for me as I visited the Muskegon Museum of Art for Edward S. Curtis: The North American Indian, a massive installation of the 30-year-plus ethnographic survey of surviving Native American culture by turn-of-the-20th-century, Seattle-based photographer Edward S. Curtis.

Edward Curtis, self-portrait

The North American Indian is a seminal and controversial blend of documentary and staged photography — one which contributes to much of the foundational imagery and, often-stereotypical, understanding possessed by white America about some 82-plus native tribes that the United States eradicated over a century of colonization. Much has been made about the complexities, contradictions, and conflicts of interest in Curtis’s masterwork, by Native and non-Native scholars. Some argue that in staging photographs and, at times, adding props or accessories, Curtis took liberties with the concept of ethnography, both imposing and reinforcing white notions of Native American appearances and culture. Others argue that without Curtis, there would be hardly any extant imagery of the cultural heritage of the tribes he worked with.

The Curtis exhibition at the Muskegon Museum of Art raised, for me, compelling questions around our individual and institutional tendencies to justify the art that we find interesting. It is undeniable that the 723 portfolio images lining the walls of the Musekegon’s galleries — as well as a 20-volume edition gathering 1,500 additional photos and ethnographic research carried out by Curtis in cooperation with tribes west of the Missouri River — represent a remarkable accomplishment. They are fascinating photos, and managed to chronicle what Curtis called, “the lifeways and morays of all the tribes who were still relatively intact from the colonialism and the invasion of Anglo culture.” Beyond ethnography, many of them are also formally beautiful works of art.

Plate from Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian

The Muskegon Museum has personal reason to take pride in this exhibition — the museum is in possession of the collection because of Lulu Miller, the first female director of the adjacent Hackley Library and second director of the Muskegon Art Museum (appointed in 1916, being the second woman in the US to run an art museum). In 1908, as her first acquisition for the library, Miller sourced $3,000 to purchase a subscription to Curtis’s series, which was issued in 20 volumes and would ultimately take 30 years to complete — an incredible gamble when you consider that sum is equivalent to $80,000 today, and certainly a tidy sum for a regional library. The Muskegon Museum of Art owns one of the estimated 225 sets of The North American Indian (many of which are likely incomplete), and this exhibition is one of very few that has put the collection on display in its entirety. The final volume arrived in late 1930, bracketing Miller’s career with the library and museum, and in the 1970s was transferred from the library to the purview of the art museum for conservation efforts.

Hackley Public Library in Muskegon, Michigan

“We think she was pretty gutsy,” said Muskegon Museum of Art’s executive director Judith Haynor, in reference to Miller. “We have a variety of letters from Curtis to Lulu, and from his staff — they had a lively correspondence. There have been 200 or more exhibitions of selections of Curtis’s work, but from what we can ascertain, never before has the entire body of work been put out on display.”

However, the hometown pride in the visionary Lulu Miller — not to mention the more generalized sense of wonder at the beauty and exoticism of Curtis’s imagery — has perhaps skewed the museum’s framing of the appropriateness and relevance of Curtis’s work. The prevailing view here is that the photographs’ issues are a product of their time, and that they are nonetheless of educational value, particularly in our current climate.

Edward S. Curtis: The North American Indian, installation view at the Muskegon Museum of Art

“I think that these images clearly show someone who began to understand more deeply the importance and uniqueness of the American Indian cultures,” said guest curator Ben Mitchell, who worked on the exhibition for some two years. “You can find this in his writing, that he came to understand that white America had something really poignant and important to learn from Native American culture, especially the depth of the spirituality. And I think about the times that we live in right now, in a time of name-calling, when our major political leadership is scapegoating people who are not white. Deportation is up 38% in just the last four months. The point is, I think, that Curtis, through The North American Indian, realized that white America had something to learn.”

Edward S. Curtis: The North American Indian, installation view, including a display featuring a camera of the type Curtis hauled, along with boxes of glass negatives

The museum has gone to great lengths to ensure deft handling of the subject matter, including engagement with the local Little River Band of Ottowa Indians, located in Manistee, Michigan (too far east to have been included in Curtis’s work). Tribal Chief Larry Romanelli served as an advisor to the exhibition, and appeared with other Native American participants in panel discussions and programming that accompanied the exhibition. His view of the exhibition is positive, and echoes a sentiment presented in some of the voluminous wall texts accompanying the imagery: that Curtis captured humanity and heritage that is significant to the descendants of Native American tribes, which would likely have otherwise been lost forever.

“Edward Curtis’s work is not embraced by 100% of people, or all Indian tribes, as well. And they wanted to know if I thought it would be a good idea or not,” said Romanelli in an interview with Hyperallergic. “I’ve been interested in his work for years, and I believe the good absolutely outweighs the negative part. I don’t believe that he ever did anything to intentionally hurt Native Americans. I think he was trying to help Native Americans, and that makes a big difference to me.”

Plate from Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian (detail view)

Romanelli also highlighted a strong sense of connection to the subjects of Curtis’s photographs. “The world would not have known those people [without Curtis’s work], and I believe, in one sense, I can see the souls of my ancestors. I would not have known what they looked like, who they were. So I cherish those photos, from my perspective.”

Perhaps it is powerful enough, all on its own, to enter a conventional museum space and find it entirely dedicated to images of people of color. Western art institutions continue to be overwhelmingly dominated by Eurocentric imagery and artists, and perhaps, by putting these photos on display, they help contribute to a collective understanding of racial injustice.

Plate from Edward Curtis’s The North American Indian

“The time we live in today, where we have the rise of white supremacy, compared with just one year ago — I think pushing forward a takeaway that the majority, dominant, white male culture in America still has a lot to learn from cultures that are not themselves is entirely appropriate,” said Mitchell, in an interview with Hyperallergic. “Some of us may feel that we have already had that takeaway, because of our background and our experience — but remember that in almost any community, the art museum, the anthropology museum will receive far more visitors with very little background in art and anthropology. Our job is to teach.”

Perhaps this is so, and all my personal frustration at the retrograde mentalities that make such remedial learning a necessity does not, at the end of the day, mean they do not exist or need to be addressed. But I have to wonder, if we are dealing with a population whose baseline takeaway from The North American Indian is that “Indians are people, too,” is putting 723 images on display enough to truly move the needle? After all, the United States is still breaking treaties. One cannot doubt Mitchell’s sincere engagement with Curtis’s work, nor the museum’s good faith efforts to present it in an inclusive way — nor even, in following Curtis’s 30-year journey of engagement with tribespeople, can one doubt that the experience profoundly affected his understanding of Native American cultures and humanity. But if presenting such imagery were enough to trigger revelation, could we not put 723 images of Syrian refugees on display somewhere, and watch the understanding come rolling in?

Edward S. Curtis: The North American Indian, installation view at the Muskegon Museum of Art

A more effective contemporary reading of Curtis’s work happens in what I consider to be the very best part of the exhibition: the room juxtaposing Curtis’s images with the work of contemporary Native American artists who’ve reflected upon his impact on their cultural identity. Some, like two paintings by Ojibwe painter Jim Denomie, characterize Curtis as a kind of voyeur or paparazzi figure. Others directly reference his photography in their personal, interpretive works. Inarguably, Curtis’s long relationship with the tribespeople of North America had a significant impact on their communities.

Some of the contemporary works, hung adjacent to Edward Curtis’s photographs which served as source material

According to the narrative presented by the museum, by the end of The North American Indian, Curtis was basically penniless and died in obscurity, as popular interest in his project waned while his own obsession mounted. In his later years, as he became more aware of the struggles of the people he was photographing, his work might be seen as an early attempt at activist or social practice art, before there was any notion of such a thing. These works, also on display, showcase Native Americans living in a more Anglicized context, wearing Depression-era clothing rather than traditional garb, and reflect the ways in which there was, by then, little remaining of the “lifeways and morays” that Curtis found so initially fascinating. The fact that he continued to pursue Native Americans as subjects outside of the exoticized trappings of their traditional culture demonstrates a real transition in Curtis’s work.

Painting by Ojibwe artist Jim Denomie characterizes Edward Curtis as a paparazzi figure

Today, the preponderance of technology has made it possible for people to self-document, and there is less a need to rely on an external, paternalistic, or authoritative record. In this, at least, Curtis’s access to photography tools and training can justifiably be recognized as a product of his time. The question is, then, how can we take this work and do it better in our time — for example, centralizing the creative output and self-representation of Native American peoples, or at least giving it equal ground in the museum setting (rather than only putting it on display in museums dedicated to anthropology or Native American art).

“I’ve come away from this two years of work realizing that history is a very powerful force, because history, when you’re immersed in it, isn’t just looking at the past,” said Mitchell. “History constantly informs the present you’re living in — or it better, if we’re paying attention. But even more than that — and this touches upon why this exhibition is so poignantly timely for the time we live in — history also points us to our future that we’re going to share. We learn from the history how to live in our present, and how to plan to live in our future.”

Edward S. Curtis: The North American Indian continues at the Muskegon Museum of Art (296 W Webster Ave, Muskegon, Mich.) through September 10.

The post A Critical Understanding of Edward Curtis’s Photos of Native American Culture appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2sYQ942

via IFTTT

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Growing up in a predominantly Native American area of rural Oklahoma, it was almost unheard of for someone who wasn’t Native to claim our ancestry. For us, that would have spurred a communal backlash. Everyone knew everyone, and to make such a claim would have been seen as seen as dishonest or nefarious.

On Monday, I awoke to the news that Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) had provided the results of a DNA test to prove she was in fact Native American. I felt the immediate pangs of dread. As the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix — the nation’s oldest Native newspaper founded in 1828 — I’m constantly fielding requests from people trying to track down their heritage. I’m also constantly getting emails from angry tribal citizens wanting to report someone who is fictitiously claiming to be Native American.

This is our reality. We are faced with an onslaught of people who have never lived in our shoes saying, “Those are my shoes too,” simply because they spit into a small hermetically sealed glass tube and got back DNA results that say they are 7 percent Native American.

Too often, Native Americans hear the words “I took a DNA test and …” Too often, our heritage and racial identity has been coopted by others for monetary gain, to claim some exoticism in their identity, or simply because someone wanted an excuse to wear a really pretty Halloween costume. But Native identity is not just about tracing a distant ancestor back to our tribe. It’s about cultural heritage, our shared experiences, and participating in our community.

I’m often amazed at the lengths some people will go to in order to become “Native American.” Our newspaper has reported on groups that create fake organizations under tribal-sound names: For under $100, a person with no claim to Native American heritage is given a bogus membership card and walk away with the mindset that they are Native.

They post on online forums as Natives, they wear regalia from Eastern tribes mixed with Western tribes, they even go so far to start community groups and give themselves “Native” names that are often so laughable and stereotypical they cease to be insulting.

Our identity isn’t present in a faux buckskin outfit or a “Made in China” headdress. It is in our communities, it is in the words of our elders and the faces of our children. It goes beyond whom our ancestors were — it dictates how we live, how we raise our children, and who we are as a people.

For Cherokee Nation citizens to be recognized as such, we must retrace our roots back to a family member who signed the Dawes Roll, essentially a turn-of-the-century census for Cherokees. This is considered a legal status as we are members of a sovereign nation within the borders of the United States. But Warren has never claimed actual citizenship in our tribe. She has infringed on this without evidence or understanding that it takes more than a DNA test to claim an identity.

I understand why Warren released her DNA profile to the masses; she has been dogged by scandal since proclaiming she was in fact “Native American” based on her family’s oral history. President Donald Trump has repeatedly referred to Warren with the very racist moniker “Pocahontas” during several of his rallies. She is attempting to put to rest the only question mark on her otherwise upstanding character, but at what cost?

Warren made her DNA claims to stop the name calling. But she, in my opinion, has propped up a growing sect of people who think they can rely solely on a DNA test to confirm their identities. A DNA test will not explain the struggle or plight your ancestors had to go though to make it to a rough patch of dusty earth in exchange for their ancestral homelands. A DNA test will not help you determine what language your ancestors spoke, the food they ate, or where they essentially originated.

The Cherokee Nation is currently on the precipice of a court case decision that could have devastating consequences to our tribe. This month, a judge in Texas struck down a law governing the adoptions of Native American children by Native families as unconstitutional. Events surrounding Warren’s claims only add confusion to an already complex situation. When people are unclear about what makes someone a citizen of a tribe, misconceptions can lead to a change in the law, in this case it could prove costly to Native children.

I personally have no ill will toward Warren or others like her, they have simply been misled, and through no fault of their own they believe that they hold a claim to being Native American. Compared to other groups and individuals out there preying on the misinformed, Warren’s actions are relatively innocuous.

She does, however, add some legitimacy to the myth that Native American heritage is tied to DNA. Heritage is not just who you are biologically. It is about your community. It is the role you play inside of your tribe, large or small. Propagating the notion that a DNA test is all that a person needs to be Native American is damaging to tribes and the sovereignty they have earned through years of struggle and strife. It simplifies a process that was determined through lengthy courtroom battles and legal discussions.

Being Native American is an honor and privilege you are born with. It simply cannot be determined by scientific testing alone.

Brandon Scott is a Cherokee Nation citizen and lifelong resident of Oklahoma. He is the executive editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the nation’s first Native newspaper.

First Person is Vox’s home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines, and pitch us at [email protected].

Original Source -> Cherokee Nation citizens like me are used to people claiming our heritage. It’s exhausting.

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

Maybe it’s just me but I don’t think I’ve seen MCU fandom blatantly sexualize a male character to the degree it’s currently doing so to Namor and honestly I’m KINDA uncomfortable about it!!

#exoticization?? in MY native american heritage month???#it’s more likely than you think!#not to gatekeep the character from non-natives but on my blog#in my space#i’m gatekeeping him from non-natives#personal#do not reblog#musings#i just want to see cool gif sets goddammit

0 notes