#extant garment

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

After looking up where this gorgeous box of New Kingdom linen from 3 500 years ago is held, I read further in the MET's online collection of these linens, and it's fascinating so I decided to share it with you. Apparently earliest known Egyptian funerary texts list linen cloth among important offerings for burials. Fabric was very expensive and viewed as an asset. Fine linens were increadibly expensive, so it's no wonder tombs of kings and queens would include boxes of fine linens as treasures for the royal's after-life journey.

And the linens the Egyptians produce were absolutely amazing. This linen from a chest in the tomb of Hatnefer and Ramose is mindblowing.

It's incredibly sheer, made from extremely fine thread and woven densely, which must have required expert skill and huge amount of labour. It's roughly 5 meters long and 1,6 meters wide, so it's absolutely massive, making it even more mind boggling how much work has gone to it. From the MET collection listing:

This sheet was woven of superfine thread that must have been spun from flax harvested when the plants were very young. The length of cloth would have taken months of constant industry to weave. [...] This cloth must be that described by the Egyptians as "royal linen," the highest quality. The sheerness of the featherweight fabric and its silken softness lend credence to New Kingdom representations of elaborately pleated garments that allow the contours of the body and even the color of the skin to show through. The cloth was repaired and laundered in ancient times.

It's fascinating, I didn't know you could get extremely fine thread by harvesting linen very young! This type of extremely fine linen simply is not made today and probably requires skills that are long lost. And it's incredible that it has survived more than 3 500 years after being used. The text of the MET listing implies that it was used as a clothing. The measurements of the cloth do lend itself for draping an elaborate pleated dress. It would've looked likely something like this.

Here's a modern interpretation on how this kind of long cloth in roughly these dimensions would have been draped.

Another incredible thing I found in the MET collection was this piece of linen.

It's not nearly as impressive as a textile as the royal linen, but this small (25.5 x 17.5 cm) folded piece of linen was found from a mass grave of soldiers from ca. 1961–1917 BC. That was almost 4 000 years ago. A 4 000 year old fabric. That is insane. Imagine the hands of a weaver weaving these specific threads into this specific fabric 4 000 years ago. Imagine touching the same threads a regular unknown weaver touched 4 000 year ago.

#history#historical textiles#historical fashion#dress history#fashion history#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian fashion#painting#mural#ancient egyptian history#textiles#extant garment#sort of

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dress, Croatia, c.1900

Blue satin and voile.

via museum of arts and crafts in zagreb

#fashion history#historical fashion#history of fashion#historical clothing#extant garment#20th century#early 20th century#20th century fashion#edwardian#edwardiana#edwardian era#edwardian fashion#edwardian dress#edwardian aesthetic#turn of the century#la belle epoque#belle epoque#gilded age#1900s#1900s fashion#1900s style#1900s dress#circa 1900#e

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

1901 silk reception gown

Finally my dbd fic got to the gown I'm most excited about!

#a talia original#talia writes#1901 gown#this is from antique gown dot com#a site that seems to have ceased existing between me writing and publishing this chapter#luckily i had to show pioup and lyres this one in advance#so i can at least link it#dead boy detectives#dbda fic#Edwin Payne#fem!edwin payne#just saying#with the barbara lasagna reveal I'm feeling very vindicated in my theory how easy it would be for Edwin to look like a lady#this gown is another gift from me to the edith Payne enjoyers#fic update#extant garment#reception gown#edit: I'm so annoyed i didn't download the other views of this dress

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silk satin & linen waistcoat. Early 19th century according to Kerry Taylor Auctions, but to me it looks much more 1780's. That closely spaced double breasted look is a very 80's style, and in the 1790's the 2 rows of buttons get much further apart.

The slanted collar and lack of big lapels do give it a somewhat early 19th century look, but I suspect this is altered from a longer waistcoat of at least a few decades earlier. The way the front edge curves just looks "off" for this later style, and the buttonholes appear to be the earlier style that are long and only partially opened, so you can have small buttons and a long decorative buttonhole. Very clever to just sew another row of buttons onto the ends to update the look!

Also you'll notice in the last picture that the linen thread used to whip the lining down around the buttonholes is the same weight as the stuff used to sew on the buttons, but a totally different colour! The fact that the button threads are visible at all is another strong point in favour of it being altered, since the typical 18th century construction involves sewing the buttonholes and attaching the buttons before the lining is added, and we can see from the backs of the buttonholes that those were done in that order.

Anyways, the reason I wanted to post this in the first place is because I think the piecing is cool. Look at how economical they're being with their scraps! (Lots of extant garments are like this but it's no less delightful for being common.) The narrower strip at the side looks like it may have been added even later to accommodate growth, but the bit of linen that the pocket welt overlaps must have been there from the time it was cut down and updated. I love the little triangle bit of piecing on the collar lining, but the most exciting scrap is the piece of ikat on the back of the collar!

438 notes

·

View notes

Text

1845 green silk brocade evening dress with a white floral pattern, with a pleated skirt and boned bodice, that is shown here displayed with a lace bertha collar. Kyoto Costume Institute collection.

#fashion history#vintage fashion#victorian fashion#historical fashion#clothes#extant garments#green dress#sage green#ilovethis

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red velvet dress, 1886, Swedish.

By Augusta Lundin.

Worn by Wilhelmina von Hallwyl at the wedding of her daughter Ebba.

Hallwylska museet.

#Augusta lundin#womenswear#extant garments#silk#19th century#dress#Sweden#1886#1880s#1880s Sweden#1880s dress#1880s extant garment#velvet#red#Hallwylska museet#Wilhelmina von Hallwyl

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

That little heart detail on the coat…. 🔥

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Met Costume Institute

Walking dress. British. ca. 1830

#fashion history#historical fashion#antique#1800#1830s fashion#1830s#extant garments#met museum#floral#this is my absolute favorite 1830s dress but I don't know if it's been posted before

782 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overview of Rococo Fashion

I mentioned in a post three god damn years ago I was writing this, but in my defense 1700s was a hell of a century.

18th century was a weird and interesting period of western fashion. It was a time of extreme inequality in Europe and even more extreme exploitation of the rest of the world through massive colonial expansion. Fashion became also extreme. The wealth amassed by the elite translated into diverse styles and complicated dress codes which required multiple changes in clothing thorough a day. Imperialism also meant increasing centralization of power and authoritarianism. In fashion this led to interesting dynamic, where the courts, trying to control the increasingly rich and powerful elite, set restrictive and archaic dress codes, while the aristocrats continued to experiment with new fashions in their casual styles. The cultural capital shifted from formal court events to the casual gatherings among the fashionable aristocrats. Salon parties, picnics, morning gatherings and even dressing up became important social events.

All of this makes the fashion of the period very hard to grasp. I have yet to find any good overview of it. So after trying to figure out this period for a long while now, I will attempt to give my own overview. Like any even remotely succinct overview, it will be incomplete. I'll focus on the high society women's fashion and the two central players in the fashion of this period, France and Britain. I define this fashion period (which is really late Baroque plus Rococo) as starting from the rise of mantua in 1680s and ending to the French Revolution in 1789, but this post will only cover the fashion up to roughly 1770. Things changed a lot during the 1770s in France especially (which was the fashion capital) and numerous new types of fashionable gowns popped up, so this would be way too long (more than it is already) and it's a natural place to split this. (I will make a second part to this but no promises on doing it quickly.) The different types of gowns were used for different purposes and often evolved fairly separately from the other types of gowns, so I will structure this around them. This approach was the only one that made sense to me so I hope it makes sense to you too. I won't go through every single type of gown, since there's too many. For example I will skip all the numerous short gowns and jackets, which were always common informal wear, and I'm focusing less on different types of negligé. Just know they and others were there. I have split this in a very vibes based eras named after the most fashionable thing at the time.

Negligé, dishabillé, half dress and full dress

But first, to understand the fashion of 18th century, we need to first understand the social life of the high society and it's dress codes. The highest level of formality was expected in court, and courts set their own dress code, which needed to be complied with. It functioned as a sort of invitation pass as court was theoretically open, but you needed to wear extremely expensive clothing to get in. Outside court the most formal events were formal balls, in which full dress (formal dress) was used. Full dresses followed fashion and were quicker to change than the court's dress code, so they weren't necessarily the same as court dresses. Less formal events were things like private dinner parties. In those half dress (semi-formal dress) was used. Then there were informal social events, like tea parties, picnics and salon gatherings, where dishabillé could be used. Dishabillé means undress, and while from modern perspective they were fully dressed, at the time it meant a type of informal dress that was used inside the home, but which was not too casual to be improper outside home either. Dishabillé was also used when otherwise going outside, not to an event, but for example visiting a friend or a relative.

At home dishabillé could be used for example to have dinner with family. Dishabillé negligé was an even more informal dress and not used outside home, except for perhaps a private morning walk. Usually it was used in the morning, but could be used till dinner on a quiet day. It could be used to receive guests or sometimes for receiving the small intimate gatherings too. It would be used with stays (could be lightly boned or worn loosely) or jumps and petticoat. Negligé was the most casual wear which was not literally underwear. Negligé was worn over the night chemise, sometimes with minimal structural garments. Negligé was used inside bedchambers or dressing room (usually the same). In the 18th century toilette, dressing up for the day, had become a very intimate social event. The upper class hair especially took quite a while to powder and put up fashionably, so while they were being dressed by the servants, they might just as well receive close friends, family members or even lovers. Sometimes women might receive close friends also when reclining in bed in their negligé.

Only court dress had explicit rules and even those were not always followed, so what was considered full dress, half dress, dishabillé or negligé was not very strict. So when I mention later what type of gown was considered to fit what sort of dress code at different points in time, these are not hard rules and people did bend them based on their taste and even politics. Some day I'll want to go deeper into this and go through some of my research of paintings and fashion plates.

1680s-1710s: The Mantua Era

Mantua gained it's start in 1670s, but became broadly fashionable in 1680s, so that's where I'll properly start. At the start of 17th century first colonial trading companies, the Dutch and the British East Indian Companies, were created and through the century they had been establishing trading posts in Asia. As the century progressed they became increasingly aggressive in their competition over the trade leading to Anglo-Dutch wars. It lead to a race to extend colonial control over the local authorities and in 1680s the British East Indian Company colonized Indian subcontinent. Increasingly available Asian luxury products led to a fascination with Asia. This fascination became justification for colonialism in the form of Orientalism. Orientalism constructs an Orient, which is fetishized, mystical, primitive and barbaric at the same time, to dehumanize colonized people and justify their subjugation. It became a very significant force in the fashion of whole 18th century.

The rigid or stiff-bodied gown

Also known as rode de cour and grand habit in France. Most of the 17th century the basic garment in women's fashion was the structured bodies and a skirt, either attached together or separate as was the case increasingly towards the end of the century. Bodies were heavily structured with boning and the primary structural layer and were used as both outer and under garment. In formal occasions the gown had rigid bodies which could be separate from the skirt but always matching. When mantua became the fashionable dishabillé in 1680s, the more formal gown started to be called rigid or stiff-bodied gown. The new silhouette was conical and stiffer. The skirt had a long trail and was open at the front and pulled to back to expose the usually contrasting petticoat. Later, especially for full dress, petticoat would usually be matching. The petticoat was also fairly conical, narrow and stiff, not full and flowing like in the mid century. It was a sort of return to the Elizabethan aesthetics of mid and late 16th century England and France after the fuller and softer aesthetics of the height of Baroque.

French fashion plate from 1683. Detail from c. 1715-1720 painting "Madame de Ventadour with Louis XIV and his Heirs".

Robe de chambre

Also called wrapper, dressing gown and nightgown. Robe de chambre became the fashionable negligee in late 1600s following the style of men's informal robe, banyan, which had become fashionable in the mid century. Banyan was of Orientalist origin and imitated Japanese kimonos. Banyan name came from Hindu merchants and was also called the Indian nightgown in Britain. In the eyes of Orientalism the whole continent of Asia (and North Africa) were all interchangeable. Banyan represented intellectualism and open-mindedness, connecting to the view that "the Orient" possessed "ancient mystic wisdom", which in the hands of the "Rational Western Man" could be turned into intellectual enlightenment. For example philosophers and intellectuals often got their portraits in banyan. Robe de chambre was like banyan, a long loose gown of rich (often imported) material. As it became more fashionable and more richly made, it graduated to dishabillé negligé. As negligé it was often worn over a night shift, when getting dressed, but as dishabillé negligé it was worn over stays and petticoat. Then it was often belted at the waist to give definition to the silhouette. It could be closed, hiding the stays and petticoat, or they could be left visible, in which case they needed to be fashionable as well. The stays evolved from the undergarment bodies and therefore weren't considered strictly undergarment, like the later corset.

Robe de chambre or dressing gown continued to be used as negligé and dishabillé negligé thorough the century only changing a little (for example in patterns and sleeve shapes) with fashions.

French fashion plate from 1685. French fashion plate from 1695.

Mantua

During 1670s increasingly formal forms of robe de chambre emerged and started to be worn as dishabillé. In addition to being belted, this robe was paired with a fashionable petticoat and the skirt was tied back like the formal rigid gowns to follow the fashionable silhouette and that way making it more formal. It became a new type of dress, mantua. Robe de chambre continued to be used as dishabillé negligé. Mantua was basically constructed the exact same way as robe de chambre, only really differing by having a long train. Early mantuas in 1680s and before were pinned closed at the front to create a sort of closed bodice mimicking rigid gowns. By 1690s though the bodice would be usually left open in a v and a stomacher in contrasting colour would be attached to the stays to cover them or stays of contrasting color from fashionable fabrics were used, usually for more casual cases. By the end of 17th century the petticoat was usually made from the same fabric as mantua, but the stomacher was still often from contrasting fabric. Around that time mantua also graduated to half dress. It was still worn in less elaborate forms as dishabillé though.

Mantua's success arguably laid in it's adaptability. It was loose, simple in cut and didn't need tailoring, so it was quite easy and cheep to make, while it could still be fitted to the fashionable silhouette with pins and belts. This made it very easy to fit comfortably to the changes in body and to other people with different bodies. It could even be fitted to new silhouettes just by changing the structural under garments. The quick and cheap construction also made it possible for rich upper class women to gain very large wardrobe and therefore develop the very complicated dress codes the 18th century would be known for.

British woolen extant mantua from late 17th century (probably around 1680s). French portrait of Anne de Souvré from 1693.

1720s-1730s: The Robe Volante Era

Rococo style started dominating the arts, especially in France, but would influence the whole western world. In fashion it meant brighter colours, lighter and fuller fabrics and lusher details. Because of the rivalry between the British and French empires, the English took a fairly oppositional stance on the very French Rococo style. This led to a gap between French and English fashions. French fashion leaned to the decadent opulence, while English fashion was more restrained and somber. Rococo was a decorational style related to the broader Classicism, and the English fashion leaned more towards "pure" Classicism.

Rigid gown

By 1720s mantua had firmly usurped rigid gown as the fashionable full dress. However, the courts still clinged to the traditional rigid gowns, even though by that point it was clear mantua had come to stay. The roundness had come back to the skirts to display the fullness of the fabrics. The skirt had started growing again in the beginning of the century and hooped petticoats had started to enter back into the wider fashion after almost a century, probably again from Spain, where they had stayed as the stable of court fashion through the whole 17th century. It kept growing through 1730s into massive round cake-like proportions. The sleeves had barely changed at all from previous decades.

Portrait of Maria Lescynska, Queen of France, from 1726. Portrait of Princess Amelia of Great Britain from 1728.

Mantua

As mentioned, mantua had became the full dress. Less elaborate mantua was still also used as half dress, but the dishabillé versions had been usurped by new types of gowns. The formal mantuas had increasingly their pleats stitched to create more fitted appearance. Skirts of the formal mantuas changed along rigid gowns. Hoops (or that large hoop skirts) weren't necessarily used with half dress.

British extant mantua from 1735-1740. Detail from French painting "Adélaïde de Gueidan and her sister at the harpsichord" from 1735-1740.

Robe volante

As mantua was turned into increasingly elaborate and formal gown, a new less formal version was developed from it. Or rather it also developed from a dressing gown as a slightly more formal version like mantua had before it. Robe volante or battante was unbelted mantua. It was closed at the front (usually stitched or closed with buttons) often leaving a similar v as mantua to reveal a stomacher, but sometimes closed so far it mostly covered the stays. It was pleated at the back, but the pleats were left loose, which was called sack back. Overall it was very loose flowing dress and combined with a large skirt the effect, especially when sitting, was like drowning in an opulent sea of fine fabric. In France it became extremely popular first as dishabillé, but eventually it was used as half dress as well.

Today it might feel a little weird that this very covering and not at all formfitting garment was seen as quite indecent in public. But at the time structural garments, especially stays, which shaped the body and concealed it's natural form, was needed to be considered dressed at all. Loose unfitted garments were already associated with negligé, but then covering the fashionable form with a garment like that left it obscured weather they were even wearing stays. The reaction was basically "what if she's naked under her clothes????" This was also of course related to Orientalism. In many Asian and North-African cultures (especially Arab and many other Muslim cultures) women (and everyone else) wore loose covering gowns, and there was fetishistic fascination among Europeans about their "exotic beauty" under the clothes. Both of these associations fed each other. So young fashionable women were then sometimes suspected of promiscuity for wearing robe volante in public. Occasionally these accusations were justified by claiming they could be hiding an extra-marital pregnancy under the loose garment, even though that seems quite impractical.

French extant robe volante from c. 1730. English portrait of Mrs. Elizabeth Symonds from 1740.

English gown

The English upper society, being more prudish and restrained, made their own version of robe volante. It was otherwise basically the same, but the pleats in front and back were pinned like in mantua. Since the skirt portion was closed at the front it was basically round gown. Sometimes belt was also used, or an apron. The v opening on the bodice usually had ribbons, sometimes pleating, to keep the robe in place. This English version was much more toned down than robe volante. It was usually made of plain single color fabric and white neckerchief stuffed under the ribbons of the v-opening or plain, often white, stomacher. There were a little more showy versions of it with elaborate patterned fabrics. For finer dishabillé round gowns the pleats were sometimes stitched to their place like mantua's pleats started to be stitched. The English did still use robe volante, but it seem to have stayed more in the dishabillé negligé (or at most dishabillé) category, while the English version of it was used as dishabillé and half dress.

British extant gown from c. 1725. Detail from British painting "Wedding of Stephen Beckingham and Mary Cox" from 1729.

English nightgown

In 1730s another version of the English gown became popular, it was basically the same, but the skirt was open at the front to reveal simple, often quilted, contrasting petticoat. The terminology is hard to pin down often in this period, but I think this version of the English gown specifically was called nightgown. It was basically robe de chambre, but pinned and belted like the other English gown. It seems to have started as the new dishabillé negligé as round gown was increasingly used as dishabillé, but it would quickly increase in formality.

The English gowns with stiched down pleasts in the back as well, possibly both type of English gowns, came to be known as robe á l'anglaise in France.

British painting "Portrait of a Woman Seated beside a Table" from 1730s. French painting "Le lecturer" from 1725-1750.

1740s-1760s: The Robe á la Française Era

This is the peak Rococo fashion era and is usually what people think when they think of 18th century fashion. Extreme fashions became popular and the gap between the elite and the common people became even more apparent in fashion and in other areas of life. This was fertile ground for political upheaval, and revolutions in US, Latin America and France would follow. The extremes therefore, even in fashion, could not last very long.

Rigid gown

By 1740s rigid gown was well passed it's time as fashionable garment and supplanted from it's place as the court dress in Britain. In France though it continued to be the robe de cour in Louis XV's court till his death in 1774. Louis XV tried to keep control over his aristocracy, even though the center of high society had increasingly shifted to the salons of Paris out of Versailles. Robe de cour adapted to the new fashionable silhouette of the mid century - the extreme wide box-like skirt frame -, but continued to be otherwise very similar in style as earlier in the century.

Portrait of Marie Leszczyńska, Queen of France, from 1747. Portrait of Princess Henriette of France from 1754.

Mantua

The British court had less authoritarian power than the French counterpart, but it was just as conservative, so when it finally accepted mantua as the formal court dress, it was already going out of fashion. From 1740s onward mantua was relegated to court gown. Like the French robe de cour, it also adapted the new fashionable boxy wideness.

British extant court mantua from c. 1750. British painting of David Garrick and Hannah Pritchard from 1752.

Robe á la française

Robe á la française, or the French gown or saque or sack or sack-back gown, replaced robe Volante as the fashionable deshabillé and half dress. Despite it's name, it may have gained it's beginning in Britain in a roundabout way. English gown was a more fitted and conservative version of robe volante, but early in 1740s, when robe á la française had not yet gained popularity, a new English version of robe volante became popularised in Britain. Like in English gown the pleats on the front were fitted, however, the pleats on the back were left unfitted and hence it became a sack-back gown. I'm not sure which came first, the robe á la française in France, which had fitted pleats on the front of the bodice, sack-back and was open at the front, or the English version, which only difference was closed front. I suspect the latter, since I have found more early examples of the closed English version, and it's sort of transitional link between robe volante and robe á la française, and I haven't found any French examples of the closed variety.

Regardless, early on robe á la française was a relatively simple, but it quickly went from dishabillé and half dress to half dress and full dress, making mantua obsolete outside the English court. In 1750s it had become the default formal wear outside courts in both France and Britain and grew increasingly opulent. The sleeves also turned more fitted, while the cuffs grew and gained more layers of ruff and lace.

British portrait of Mrs. Wardle from 1742. French extant gown from c. 1755-1760.

English gown

The open English gown was also adopted by the French as dishabillé and increasingly as robe á la française grew in formality, as half dress, like it was used in Britain as well, though it was more popular in Britain. It followed the same trends too, especially in it's half dress form. Dishabillé version of the garment continued to be quite simple, worn with less structuring and otherwise too quite similar as they were earlier in the century.

Portrait of Sarah Lascelles from 1749. British extant gown from 1770-1775.

Round gown

Closed versions of the English gown were called round gown. It was possibly always called that, but as said multiple times, the terminology of this period is unclear. They stayed fairly similar as they had been since 1720s and didn't really gain popularity in France. I have not seen examples of this early type of round gown from France. The open English gown seemed to have become the more formal version and examples of round gown from 1740s and 1750s seem to be more dishabillé than half dress. Round gown in this form fell out of fashion around 1760, which gets us to the last garment we'll cover in this post.

Portrait of Mrs Iremonger of Wherwell Priory from 1745. British extant garment from 1760-1775.

Close bodied gown

Close bodied gown basically replaced round gown. The unclear terminology makes this especially hard to parse out. It seems to me that after the early version of round gown (open bodice, closed skirt) was replaced with close bodied gown (closed bodice, closed skirt), that was then called round gown as well. The trouble is that close bodied gowns existed alongside round gowns, and not all close bodied gowns even had closed skirt (this applies later as well and I'm not sure weather they were separated in terminology or were both called round gown). Close bodied gowns in fact existed basically during the whole century, but earlier they were used only by underage girls. Main difference to these earlier girl's dresses was that they were closed at the back, while the later close bodied gowns worn by adult women were closed at the front. Some of the close bodied gowns are however constructed similarly to girls' dresses, where the bodice and the skirt are cut fully separately from simple cuts, only difference being the opening is at the center front instead of center back. The close bodied gown, which clearly evolved from the English gown, instead has the distinctive pleated back seams of English gowns. Early gowns like this were clearly constructed as basically the same as the English gown, but the front was not pleated open into a v-shape, instead it was closed over the stays. This close bodied version of round gown would later become very popular casual garment everywhere among all classes and would eventually come to define the Regency fashion which followed after the French Revolution.

British extant garment from c. 1750. Portrait of Anna Dorothean Finney from 1758.

Sources

Patterns of Fashion 1, Janet Arnold

Faction and Fashion: The Politics of Court Dress in Eighteenth-Century England, Hannah Greig

5 Facts About Fashionable, Morning and Domestic Apparel in 18th Century France - MoMu Antwerp (based on a book "Living Fashion: Women’s Daily Wear 1750–1950 from the Jacoba de Jonge Collection" but I couldn't get my hands on the book)

Women's clothing and accessories - 18th Century Notebook

#historical fashion#fashion history#history#dress history#rococo fashion#18th century#18th century fashion#robe a l'anglaise#robe a la francaise#rococo#mantua#extant garment#painting#fashion plate

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wedding gown, 1912.

Silk charmeuse trained gown, lace bodice trimmed w/ crystal beads & pearls.

via augusta auctions

#THIS IS HEAVENLY#when i say my jaw dropped#fashion history#history of fashion#historical fashion#history of dress#wedding dress#wedding gown#edwardian era#edwardiana#edwardian fashion#titanic era fashion#titanic era#20th century fashion#extant garment#1910s#1912#1910s fashion#e

698 notes

·

View notes

Text

Afternoon dress, about 1906, silk damask, silk lace, silk taffeta,

Girolamo Giuseffi (American, born Italy, 1864–1934) and G. Giuseffi Ladies' Tailoring Company (American)

Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Carolyn Garrigues Scofield in memory of her grandmother Caroline Burford Danner, 1986.400.

#source included#extant garment#lace lingerie gown#1900s gown#1906#these images are public domain#i'm just dreaming of lace dresses today#costuming inspiration#historical clothing#historical fashion#image id in alt text#indianapolis museum of art at newfields

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evening dress ca. 1905

From Kerry Taylor Auctions

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

Not sure if it's the same one or just a very similar one, but the dressing gown that inspired yours is currently on display in the Powerhouse museum in Sydney! The colours aren't accurate since my phone likes to oversaturate things :(

Yes, that's the one!! Thank you for the closeups! It's neat to see that some of the damaged triangles have conservation mesh sewn over them, I hadn't seen that in any of the other photos. So many nice woven textures too.

I suppose I ought to add some pictures of my version for anyone who hasn't seen it.

youtube

837 notes

·

View notes

Text

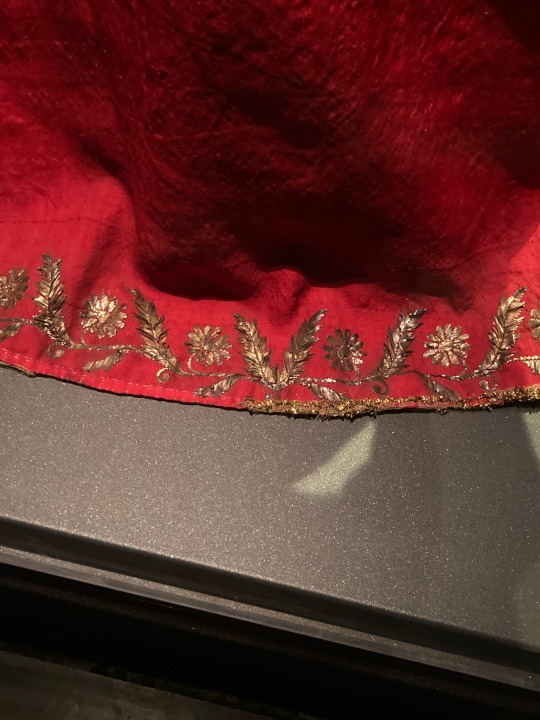

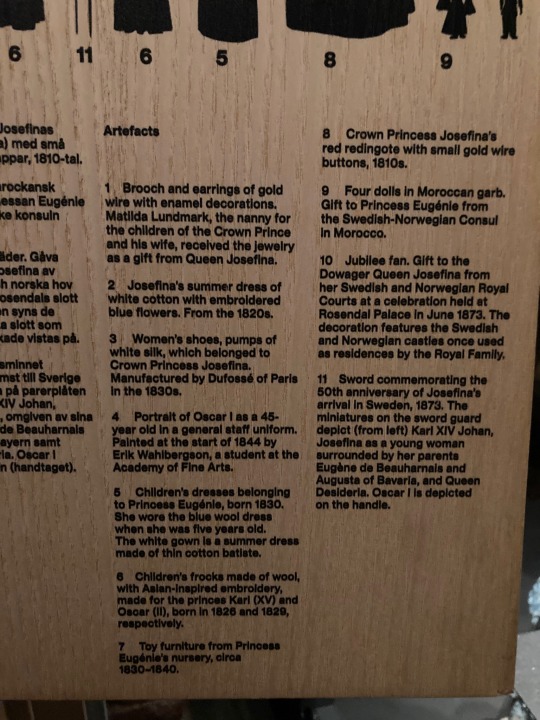

Crown Princess Josefina's Red Redingote With Small Gold Wire Buttons

Circa 1810s

The Royal Armoury

Stockholm, Sweden

#redingote#extant garments#1810s fashion#empire fashion#gold embroidery#gold buttons#crown princess josefina#royal armoury#stockholm#sweden

563 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beautiful Evening Dresses from 1910s Edwardian Era

Evening/Dinner dress • 1908-10 | House of Worth • 1910s

1913

Callot Soeurs • 1916 | Callot Soeurs • 1910

#fashion history#callot soeurs#vintage designer fashion#1910s fashion#women's fashion history#extant garments#fashion history blog#house of worth#the resplendent outfit blog#edwardian fashion

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ball gown Designer: Driscoll

ca. 1900

(via Driscoll | Ball gown | American | The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

422 notes

·

View notes