#first quarto hamlet

Text

An AMENDED Rundown on the Absolute Chaos That is First Quarto Hamlet

O, gather round me, my dear Shakespeare friends

And let me tell to ye a tale of woe.

It was a dark and drizzly winter night,

When I discovered my life was a lie...

This tale is a tragedy, one of Shakespeare sources turned into gardening websites, "misdated" quartos, and failed internet archives. It is also a story of the quarto itself, an early printing of our beloved Danish Prince's play, including an implied Hamlet/Horatio coffee date, weird and extremely short soliloquies, and Gertrude with a hint of motivation and autonomy.

But let us start from the beginning. Long ago, in the year of our lord 2022, I pulled a Christmas Eve all-nighter to bring you this post: https://www.tumblr.com/withasideofshakespeare/704686395278622720/a-rundown-on-the-absolute-chaos-that-is-first?source=share

It was popularish in Shakespeare circles, which is why I am amending it now! I returned to it tonight, only to discover a few problems with my dates and, more importantly, a mystery in which one of my sources miraculously turned into a link to a gardening website...

Anyhow, let us begin with the quarto!

TL;DR: Multiple versions of Hamlet were printed between 1603 and 1637 (yes, post-folio) with major character and plot differences between them. The first quarto (aka Q1) is best known for its particular brand of chaos with brief soliloquies, an extra-sad Hamlet, some mother-son bonding, weird early modern spelling, and deleted/adapted scenes with major influences on the plot of the play!

A long rundown is included below the cut, including new and improved sources, lore, direct quotes, and my own interpretations. Skip what bores you!

And continue... if thou darest!

What is the First Quarto? Actually, what is a quarto?

Excellent questions, brave Hamlet fan!

A quarto is a pamphlet created by printing something onto a large sheet of paper and then folding it to get a smaller pamphlet with more pages per big sheet (1).

First Quarto Hamlet was published in 1603 and then promptly lost for an entire two centuries until it was rediscovered in 1823 in the library of Sir Henry Bunbury. Rather than printed from a manuscript of Shakespeare, Q1 seems like it may be a memorial reconstruction of the play by the actor who played Marcellus (imagine being in a movie, memorizing the script to the best of your ability, writing it down, and then selling "your" script off to the print shop), but scholars are still out on this (2).

Are you saying that Hamlet comes with the stageplay equivalent of a “deleted scenes and extra credits” movie disc?

Yep, pretty much! In fact, there are even more of these! Q2 was printed in 1604 and it seems to have made use of Shakespeare's own drafts, and rather than being pirated like Q1, it was probably printed more or less with permission. Three more subsequent quartos were published between 1611 and 1637, but they share much in common with Q2.

The First Folio (F1) was published in 1623 and its copy of Hamlet was either based on another (possibly cleaner but likely farther removed from Shakespeare's own text) playhouse manuscript (2, 3). It was an early "collected works" of sorts--although missing a few plays that we now consider canon--and is the main source used today for many of the plays!

The versions of the play that we read usually include elements from both Q2 and F1.

So... Q1? How is it any different from the version we all know (and love, of course)? What do the differences mean for the plot?

We’ll start with minor differences and build up to the big ones.

Names and spellings

Most of the versions of Shakespeare's plays that we read today have updated spellings in modern English, but a true facsimile (a near-exact reprint of a text) maintains the early modern English spellings found in the original text.

For example, here is the second line of the play transcribed from F1:

Francisco: Nay answer me: stand and vnfold your selfe.

For the most part, however, the names of the characters in these later versions (ex: F1) are spelled more or less how we would spell them today. This is not so in Q1.

Laertes is “Leartes”, Ophelia is “Ofelia”, Gertrude is “Gertred” (or sometimes “Gerterd”), Rosencrantz is “Rossencraft”, Guildenstern is “Gilderstone”, and my favorite, Polonius gets a completely different name: Corambis.

(This goes on for minor characters, too. Sentinel Barnardo is “Bernardo”, Prince Fortinbras of Norway is “Fortenbrasse”, Voltemand and Cornelius--the Danish ambassadors to Norway--are “Voltemar” and “Cornelia” (genderbent Cornelius?), Osric doesn’t even get a name- he is called “the Bragart Gentleman”, the Gravediggers are called clowns, and Reynaldo (Polonius’s spy) gets a whole different name--“Montano”.)

2. Stage directions

Some of Q1's stage directions are more detailed and some are simply non-existent. For instance, when Ophelia enters singing, the direction is:

Enter Ofelia playing on a Lute, and her haire downe singing.

But when Horatio is called to assist Hamlet in spying on Claudius during the play, he has no direction to enter, instead opting to just appear magically on stage. Hamlet also doesn't even say his name, so apparently his Hamlet sense was tingling?

3. Act 3 scene reordering

Claudius and Polonius go through with the plan to have Ophelia break up with Hamlet immediately after they make it (typically, the plan is made in early II.ii and gone through with in III.i, with the players showing up and reciting Hecuba between the two events). In this version, the player scene (and Hamlet’s conversation with Polonius) happen after ‘to be or not to be’ and ‘get thee to a nunnery.’ I’m not sure if this makes more or less sense. Either way, it has a relatively minimal impact on the story.

4. Shortened lines and straightforwardness

Many lines, especially after Act 1, are significantly shortened, including some of the play's most famous speeches.

Laertes’ usually long-winded I.iii lecture on love to Ophelia is shortened to just ten lines (as opposed to the typical 40+). Polonius (er... Corambis) is still annoying and incapable of brevity, but less so than usual. His lecture on love is also cut significantly!

Hamlet’s usual assailing of Danish drinking customs (I.iv) is cut off by the ghost’s arrival. He’s still the most talkative character, but his lines are almost entirely different in some monologues, including ‘to be or not to be’! In other spots, however, (ex: get thee to a nunnery!) the lines are near-identical. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to where things diverge linguistically, except that when Marcellus speaks, his lines are always correct. Hm...

5. The BIG differences: Gertrude’s promise to aid Hamlet in taking revenge

Act 3, scene 4 goes about the same as usual with one major difference: Hamlet finishes off not with his usual declaration that he’s to be sent for England but with an absolutely heart-wrenching callback to act 1, in which he echoes the ghost’s lines and pleads his mother to aid him in revenge. And she agrees. Here is that scene:

Note that "U"s are sometimes "V"s and there are lots of extra "E"s!

Queene Alas, it is the weakenesse of thy braine,

Which makes thy tongue to blazon thy hearts griefe:

But as I haue a soule, I sweare by heauen,

I neuer knew of this most horride murder:

But Hamlet, this is onely fantasie,

And for my loue forget these idle fits.

Ham. Idle, no mother, my pulse doth beate like yours,

It is not madnesse that possesseth Hamlet.

O mother, if euer you did my deare father loue,

Forbeare the adulterous bed to night,

And win your selfe by little as you may,

In time it may be you wil lothe him quite:

And mother, but assist mee in reuenge,

And in his death your infamy shall die.

Queene Hamlet, I vow by that maiesty,

That knowes our thoughts, and lookes into our hearts,

I will conceale, consent, and doe my best,

What stratagem soe're thou shalt deuise.

Ham. It is enough, mother good night:

Come sir, I'le prouide for you a graue,

Who was in life a foolish prating knaue.

Exit Hamlet with [Corambis/Polonius'] dead body.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Despite having seemingly major consequences for the plot, this is never discussed again. Gertrude tells Claudius in the next scene that it was Hamlet who killed Polonius (Corambis, whatever!), seemingly betraying her promise.

However, Gertrude’s admission of Hamlet’s guilt (and thus, betrayal) could come down to the circumstance she finds herself in as the next scene begins. There is no stage direction denoting her exit, so the entrance of Claudius in scene 5 may be into her room, where he would find her beside a puddle of blood, evidence of the murder. There’s no talking your way out of that one…

6. The BIGGEST difference: The added scene

After Act 4, Scene 6, (but before 4.7) comes this scene, in which Horatio informs Gertrude that Hamlet was to be executed in England but escaped:

Enter Horatio and the Queene.

Hor. Madame, your sonne is safe arriv'de in Denmarke,

This letter I euen now receiv'd of him,

Whereas he writes how he escap't the danger,

And subtle treason that the king had plotted,

Being crossed by the contention of the windes,

He found the Packet sent to the king of England,

Wherein he saw himselfe betray'd to death,

As at his next conuersion with your grace,

He will relate the circumstance at full.

Queene Then I perceiue there's treason in his lookes

That seem'd to sugar o're his villanie:

But I will soothe and please him for a time,

For murderous mindes are alwayes jealous,

But know not you Horatio where he is?

Hor. Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me

To meete him on the east side of the Cittie

To morrow morning.

Queene O faile not, good Horatio, and withall, commend me

A mothers care to him, bid him a while

Be wary of his presence, lest that he

Faile in that he goes about.

Hor. Madam, neuer make doubt of that:

I thinke by this the news be come to court:

He is arriv'de, obserue the king, and you shall

Quickely finde, Hamlet being here,

Things fell not to his minde.

Queene But what became of Gilderstone and Rossencraft?

Hor. He being set ashore, they went for England,

And in the Packet there writ down that doome

To be perform'd on them poynted for him:

And by great chance he had his fathers Seale,

So all was done without discouerie.

Queene Thankes be to heauen for blessing of the prince,

Horatio once againe I take my leaue,

With thowsand mothers blessings to my sonne.

Horat. Madam adue.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

First of all, the implication of Hamlet and Horatio's little date in the city is adorable ("Yes Madame, and he hath appoynted me / To meete him on the east side of the Cittie / To morrow morning.") It reads like they're going out for coffee!

And perhaps more plot relevant: if Gertrude knows of Claudius’s treachery ("there's treason in his lookes"), her death at the end of the play does not look like much of an accident. She is aware that Claudius killed her husband and is actively trying to kill her son and she still drinks the wine meant for Hamlet!

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for! My thoughts! Yippee!

On Gertrude:

WOW! I’m convinced that she is done dirty by F1and Q2! She and Hamlet have a much better relationship (Gertrude genuinely worries about his well-being throughout the play.) She has an actual personality that is tied into her role in the story and as a mother. I love Q1 Gertrude even though in the end, there’s nothing she can do to save Hamlet from being found out in the murder of Polonius and eventually dying in the duel. Her drinking the poisoned wine seems like an act of desperation (or sacrifice? she never asks Hamlet to drink!) rather than an accident.

On the language:

I think Q1′s biggest shortcoming is its comparatively simplistic language, especially in 'to be or not to be,' which is written like this in the quarto:

Ham. To be, or not to be, I there's the point,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all:

No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes,

For in that dreame of death, when wee awake,

And borne before an euerlasting Iudge [judge],

From whence no passenger euer retur'nd,

The vndiscouered country, at whose sight

The happy smile, and the accursed damn'd.

But for this, the ioyfull hope of this,

Whol'd beare the scornes and flattery of the world,

Scorned by the right rich, the rich curssed of the poore?

The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd,

The taste of hunger, or a tirants raigne,

And thousand more calamities besides,

To grunt and sweate vnder this weary life,

When that he may his full Quietus make,

With a bare bodkin, who would this indure,

But for a hope of something after death?

Which pusles [puzzles] the braine, and doth confound the sence,

Which makes vs rather beare those euilles we haue,

Than flie to others that we know not of.

I that, O this conscience makes cowardes of vs all,

Lady in thy orizons, be all my sinnes remembred.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

The verse is actually closer to perfect iambic pentameter (meaning more lines have exactly ten syllables and consist entirely of iambs--"da-DUM") than in the Folio, which includes many 11-syllable lines. The result of this, however, is that Hamlet comes across here as considerably less frantic (those too-long verse lines in F1 make it feel like he is shoving words into too short a time, which is so very on-theme for him) and more... sad. Somehow, Q1 Hamlet manages to deserve a hug even MORE than F1 Hamlet!

Nevertheless, this speech doesn't hit the way it does in later printings and I have to say I prefer the Folio here.

On the ending:

The ending suffers from the same effect ‘to be or not to be’ does--it is simpler and (imo) lacks some of the emotion that F1 emphasizes. Hamlet’s final speech is significantly cut down and Horatio’s last lines aren’t quite so potent--although they’re still sweet!

Horatio. Content your selues, Ile shew to all, the ground,

The first beginning of this Tragedy:

Let there a scaffold be rearde vp in the market place,

And let the State of the world be there:

Where you shall heare such a sad story tolde,

That neuer mortall man could more vnfolde.

(Internet Shakespeare, Source #4)

Horatio generally is a more active character in Q1 Hamlet. This ending suits this characterization. He will tell Hamlet’s story, tragic as it may be. It reminds me a bit of We Raise Our Cups from Hadestown. I appreciate that this isn't a request but a command: put up a stage, I will tell this story.

Closing notes:

After over a year, it was due time this post received an update. My main revisions were in regard to source verification. Somehow, in the last year or so, one of my old sources went from linking to a PDF of Q1 to a garden website (???) and some citations were missing from the get-go as a result of this being an independently researched post that involved pulling an all-nighter on Christmas Eve (but no excuses, we need sources!)

I have also corrected some badly worded commentary implying that the Folio's verse is more iambic pentameter-y (it's not; in fact, Q1 tends to "normalize" its verse to make it fit a typical blank verse scheme better than the Folio's does--the lines actually flow better, typically have exactly ten syllables, and use more iambs than Q1's) as well as that the spelling in the Folio is any more modern than those in Q1 (they're both in early modern English; I was mistakenly reading a modernized Folio and assuming it to be a transcription--nice one, 17-year-old Dianthus!) Additionally, I corrected the line breaks in my verse transcriptions and returned the block quotations to their original early modern English, which feels more authentic to what was actually written. A few other details and notes were added here and there, but the majority of the substance is the same.

Overall, if you still haven't read Q1, you absolutely should! Once you struggle through the spelling for a while, you'll get used to it and it'll be just as easy as modern English! If you'd prefer to just start with the modern English, I have also linked a modern translation below (source 5).

And finally, my sources!

Not up to citation standards but very user-friendly I hope...

1. Oxford English Dictionary

2. Internet Shakespeare, Hamlet, "The Texts", David Bevington (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_TextIntro/index.html)

3. The Riverside Shakespeare (pub. Houghton Mifflin Company; G.B. Evans, et al.)

4. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (facsimile--in early modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1/complete/index.html)

5. Internet Shakespeare, First Quarto (modern English) (https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1M/index.html)

And here conclude we our scholarly tale,

Of sources, citation, and Christmastime too,

Go read the First Quarto! And here, I leave you.

#shakespeare#hamlet#first quarto#first quarto hamlet#classic literature#revisions#hey look at me#having some scholarly merit#i have so much left to learn#which is a darn good thing#how else would i spend my evenings?#the worst part about this#is that it all started because i thought a got a date wrong#but it turns out i didn't#so HA!#but then i realized i got everything else wrong so....#corrections it is!

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

first quarto hamlet my beloved…

#he is such a little shit (affectionate)#to me he seems younger than in some of the other versions#maybe it’s because the language is more simple#but i feel like he’s also more angsty and kind of blunt#instead of ‘i did love you once’ he says ‘i never loved you’#which sounds like something a bitter teenager would say#hamlet#first quarto

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Without the First Folio, we would have been stuck with the text of Hamlet as it appears in the “Second Quarto”, a cheap version probably rushed out to counter the success of a pirated edition, the notorious “First Quarto” of 1603. Even the Second Quarto suffers from typesetting errors—among the most egregious, its version of this monologue. Had they been working from the Second Quarto, Tennant and Essiedu would have graced the RSC stage lamenting the Almighty’s opposition not to self-slaughter—but to seale-slaughter.

As the Shakespearian scholar Jonathan Bate has observed, “ecclesiastical law as shaped by the Bible says nothing about the clubbing of baby seals.” We have yet to see a conservationist production of Hamlet take advantage of this variant (although its time will surely come). Thanks to the First Folio, it is the slaughter of the self, not the seal, that preoccupies modern Hamlets on stage.

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#first folio#hamlet#bad quarto#second quarto#seale slaughter#baby seals

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"'To be, or not to be, aye there's the point?' You stupid monkey!"

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“To be, or not to be, I there's the point,

To Die, to sleepe, is that all? I all:

No, to sleepe, to dreame, I mary there it goes,

For in that dreame of death, when wee awake,

And borne before an euerlasting Iudge,

From whence no passenger euer retur'nd,

The vndiscouered country, at whose sight

The happy smile, and the accursed damn'd.

But for this, the ioyfull hope of this,

Whol'd beare the scornes and flattery of the world,

Scorned by the right rich, the rich curssed of the poore?

The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd,

The taste of hunger, or a tirants raigne,

And thousand more calamities besides,

To grunt and sweate vnder this weary life,

When that he may his full Quietus make,

With a bare bodkin, who would this indure,

But for a hope of something after death?

Which pusles the braine, and doth confound the sence,

Which makes vs rather beare those euilles we haue,

Than flie to others that we know not of.

I that, O this conscience makes cowardes of vs all,

Lady in thy orizons, be all my sinnes remembred.”

Hamlet, First Quarto (1603)

#incorrect literature quotes#shakespeare#hamlet#bad quarto#first quarto#i rise from the dead to bring you the stupidest version of hamlet there is

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hamlet’s Age

Not to bring up an age-old debate that doesn’t even matter, but I have been thinking recently how interesting Hamlet’s age is both in-text and as meta-text.

To summarize a whole lot of discussion, we basically only have the following clues as to Hamlet’s age:

Hamlet and Horatio are both college students at Wittenberg. In Early Modern/Late Renaissance Europe, noble boys typically began their university education at 14 and usually completed at their Bachelor’s degree by 18 or 19. However, they may have been studying for their Master’s degrees, which was typically awarded by age 25 at the latest. For reference, contemporary Kit Marlowe was a pretty late bloomer who received a bachelor’s degree at 20 and a master’s degree at 23.

Hamlet is AGGRESSIVELY described as a “youth” by many different characters - I believe more than any other male shakespeare character (other than 16yo Romeo). While usage could vary, Shakespeare tended to use “youth” to mean a man in his late teens/very early 20s (actually, he mostly uses it to describe beardless ‘men’ who are actually crossdressing women - likely literally played by young men in their late teens)

King Hamlet is old enough to be grey-haired, but Queen Gertrude is young enough to have additional children (or so Hamlet strongly implies)

Hamlet talks about plucking out the hairs of his beard, so he is old enough to at least theoretically have a beard

In the folio version, the gravedigger says he became a gravedigger the day of Hamlet’s birth, and that he’s be “sixteene here, man and boy, thirty years.” However, it’s unclear if “sixteene” means “sixteen” or “sexton” (ie has he worked here for 16 years but is 30 years old, or has he been sexton there for thirty years?)

Hamlet knew Yorick as a young child, and the gravedigger says Yorick was buried 23 years ago. However, the first quarto version version of Hamlet says “dozen years” instead of “three and twenty.” This suggests the line changed over time. (Or that the bad quarto sucks - I really need to make that post about it, huh…)

Yorick is a skull, and according to the gravedigger’s expertise, he has thus been dead for at least 7-8 years - implying Hamlet is at least ~15yo if he remembers Yorick from his childhood

One important thing sometimes overlooked - Claudius takes the throne at King Hamlet’s death, not Prince Hamlet. That is mostly a commentary on English and French monarchist politics at the time, but it is strange within the internal text. A thirty year old Hamlet presumably would have become the new monarch, not the married-in uncle (unless Gertrude is the vehicle through which the crown passes a la Mary I/Phillip II - certainly food for thought)

Honestly, Hamlet is SO aggressively described as being very young that I’m fairly confident the in-text intention is to have him be around 18-23yo. Placing his age at 30yo simply does not make much sense in the context of his descriptors, his narrative role, and his status as a university student.

However, it doesn’t really matter what the “right” answer is, because the confusion itself is what makes the gravedigger scene so interesting and metatextual. We can basically assume one of the following, given the folio text:

Hamlet really is meant to be 30yo, and that was supposed to surprise or imply something to the contemporary audience that is now lost to us

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was written down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text justification of the seeming disconnect between age of actor and description of “youth”

Older actors were playing Hamlet by the time the folio was set down, and the gravedigger’s description was an in-text JOKE making fun of the fact that a 30-something year old is playing a high-school aged boy. This makes sense, as the gravedigger is a clown and Hamlet is a play that constantly pokes fun at its own tropes and breaks the fourth wall for its audience

The gravedigger cannot count or remember how old he is, and that’s the joke (this is the most common modern interpretation whenever the line isn’t otherwise played straight). If the clown was, for example, particularly old, those lines would be very funny

Any way you look at it, I believe something is echoing there. It seems like this is one of the many moments in Hamlet where you catch a glimpse of some contemporary in-joke about theater and theater culture* that we can only try to parse out from limited context 430 years later. And honestly, that’s so interesting and cool.

*(My other favorite example of this is when Hamlet asks Polonius about what it was like to play Julius Caesar in an exchange that pokes fun of Polonius’ actor a little. This is clearly an inside-joke directed at Globe regulars - the actor who played Polonius must have also played Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s play, and been very well reviewed. Hamlet’s joke about Brutus also implies the actor who played Brutus is one of the main cast in Hamlet - possibly even the prince himself, depending on how the line is read).

#hamlet#hamlet meta#hamlet’s age#this obviously does NOT imply anything about being 30yo btw#any age is a good age to be driven to madness by guilt and grief#It’s just very usual for shakespeare to describe somebody well past their apprentice age as a ‘youth’ SO MUCH#and that makes those lines very interesting#shut up e#willy shakes#posting this while EXHAUSTED going to see a million errors and tone problems tomorrow sorry in advance yall#**very unusual#long post#posting Hamlet meta like it’s 2014 hell yeah

822 notes

·

View notes

Text

just encountered first quarto hamlet for the first time in, apparently, my life, and what the fuck. we got queen gertred. we got ofelia and leartes and their dad corambis. and how could I forget that magnificent comedy duo, rossencraft and gilderstone! this is what happens when you order shakespeare off wish dot com

#hamlet#yeah yeah yeah spelling was loosey goosey and Shakespearean canon is the result of 400 years of editorializing#but CORAMBIS…

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakespeare Weekend

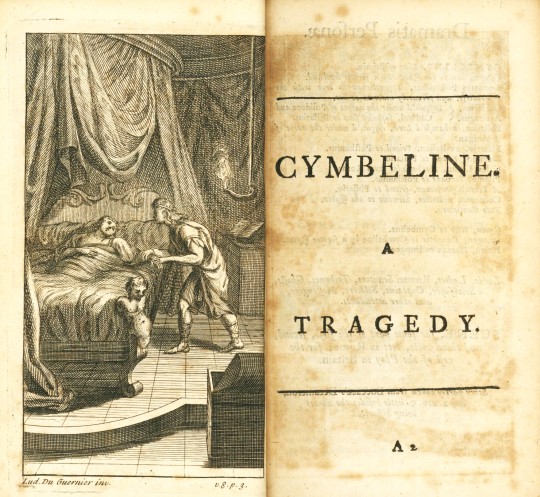

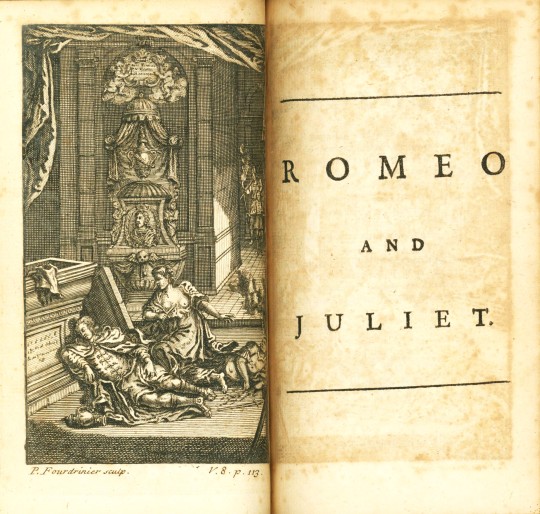

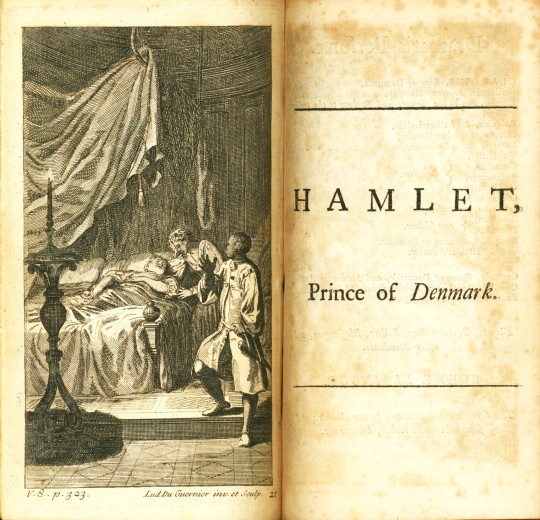

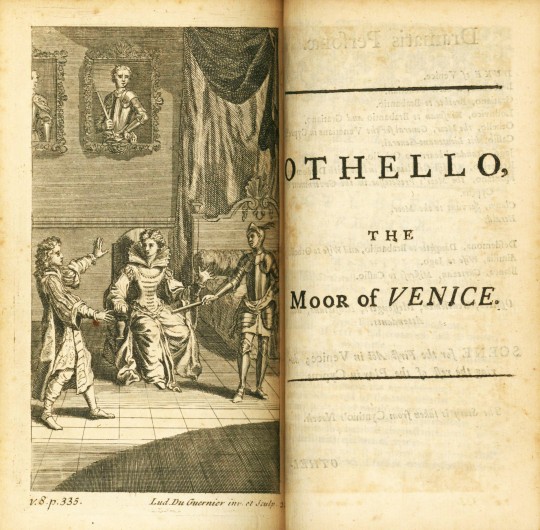

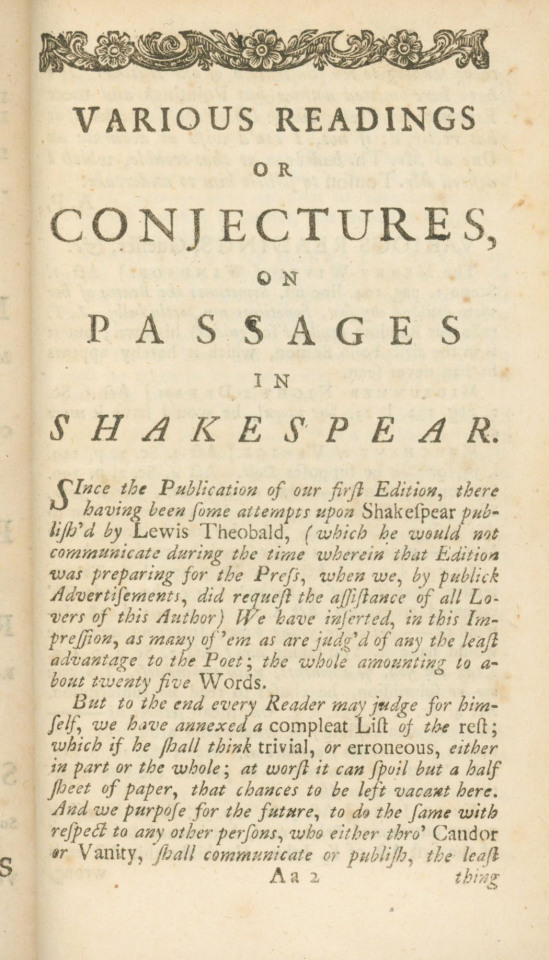

The works of Mr. William Shakespear: in ten volumes published in 1728 by Alexander Pope (1688-1744) and Dr. George Sewell (d. 1726) for Jacob Tonson (1655-1736), is considered complete in 8, 9, or 10 volumes. Pope’s second edition, as we see here, was published in 8 volumes with supplementary 9th and 10th volumes.

As such, Volume Eight includes an index of the characters, sentiments, speeches and descriptions found throughout the first eight volumes. It concludes with, in Pope’s words, “various readings and guesses” that Lewis Theobald (1688-1744) had published in 1726 as editorial amendments to the collection with the intent to “restore the true reading of Shakespeare”. In a bit of catty accusations, Pope claims Theobald had originally withheld his information at the time of the first pressing, and that he only used roughly twenty-five words of Theobald’s corrections in the second edition.

The plays within volume eight are all tragedies dealing with themes of innocence, jealousy, revenge, and fate; they include Cymbeline, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, and Othello. Pope notes that the story of Hamlet was not invented by Shakespeare but that its source is unclear. Regardless, Hamlet is hailed as one of the greatest plays of all time and at 29, 551 words is Shakespeare’s longest.

Pope’s editions of Shakespeare were the first attempted to collate all previous publications. He consulted twenty-seven early quartos restoring passages that had been out of print for almost a century while simultaneously removing about 1,560 lines of material that didn’t appeal to him. Scene divisions, stage directions, dramatis personae, and full-page engravings by either French artist Louis Du Guernier (1677-1716) or Englishman Paul Fourdrinier (1698-1758) precede each play.

View more Shakespeare Weekend posts.

-Jenna, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#shakespeare weekend#william shakespeare#shakespeare#the works of mr. william shakespear in ten volumes#alexander pope#dr. george sewell#jacob tonson#lewis theobald#cymbeline#romeo and juliet#hamlet#othello#louis du guernier#paul fourdrinier#engravings

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

post going around that I'm 80% convinced is historical misinfo on a topic I've studied but I don't have the effort or certainty to dispute it.

anyway.

folio - big fancy published book of plays. shakespeare's first folio was published posthumously by his contemporaries (Ben Jackson iirc).

quarto - pamphlet lil fuckers, often published by players in the plays (this is what I'm assuming op of the post I'm not replying to is on about).

the Shakespeare we know today is a mingling of works from quartos and the first folio merged because they changed in iterations. not a jot of it was published by shakespeare.

and don't get me wrong. equating that with modern plagiarism is very very different. the printing press is a fuckin new fangled thingymabob. but stagecraft itself is much much older.

the plays changed as they were performed. things worked, things didn't. sometimes the cannons you're using for sound effects set the theatre alight and kill an audience member (you'd change that bit for sure).

I think there are four versions of hamlet, maybe three. And elements change between them. Typos and errors create new meanings. Whole speeches are added and lost.

And over four hundred years people have been in with their editing pencils editing and making things fit.

The word 'bowdlerise' comes from a Victorian publishing of Shakespeare by the Bowdlers, who thought everyone should know shakespeare but wanted to censor the bits unsuitable for Victorian ethics.

Copyright is not really a thing in Shakespeare's day.

Stories are stories.

Plays consume themselves, recreate themselves. Playwriting is a more communal experience than you imagine. Strike out the tortured genius in the garret room. Put him in the theatre, among a maelstrom of voices who play the stage and know what works.

And thank fuck that quartos and folios found their way to the printing press, by any means

Writer's copyright is much younger than you'd think (Dracula had to be performed once on stage before Stoker had literary rights to it, centuries later)

anyway I did this a while ago so don't cite me lol. Might dig up my lecture notes later, if I can be fucked

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love the first quarto because it reads like when a bunch of middle schoolers are forced to perform Hamlet in their English class

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just responded to one of your posts, realized it was from over 7 years ago and I’m. Not sure if you hold the same opinion as you did then, but I was about hamlet’s age. I wrote there that I had a slightly different take since I’m younger and a younger hamlet makes more sense in my eyes - authority, parents, control, choices and what you’re allowed to do, etc. - but I respect what you have to say and I don’t want to start discourse.

(Also, I’m aware that I’m probably spamming your account and I apologize for that.)

Spam away! Any meta on anything Shakespeare is my bread-and-butter by this point. I was going to do a separate post on the question of Hamlet’s age, but this will do for now.

With regards to Hamlet’s age, it’s both canonically clear and contentious. Hamlet is 30 in the Folio and Quarto 2 that have the Gravedigger’s line, “I’ve been a sexton, man and boy, for thirty years” and states clearly that he first began working on the day Hamlet himself was born (also when King Hamlet overcame Fortinbras).

The only proof of Hamlet’s being sixteen comes from Quarto 1–a.k.a the Bad Quarto, which is radically different from any other version of Hamlet, including Quarto 2 and the First Folio version.

The Bad Quarto may have been an abridged tour version for when Shakespeare’s troupe played the countryside—that is at least one plausible theory—but for the most part, critics have been reluctant to rely on the Bad Quarto completely. It’s just very, very mangled. The famous soliloquy in it begins “To be or not to be—ay, that is the point. To die, to sleep, is that all? Ay, all.”

Those that believe the Bad Quarto had it right and the Quarto and Folio are wrong believe that Shakespeare may have been making Hamlet’s age closer to the real-life age of Richard Burbage, who originated the role—the theory goes that audiences would not accept a portly 30-year-old playing a 16-year-old. Given that the Elizabethans had no problem with young boys playing girls and women and that Shakespeare’s troupe played characters of most all ages, this is really unconvincing to me.

If the Bad Quarto is indeed the correct one, then there is one logical explanation for the change: Shakespeare changed his mind. He decided not to have a sixteen-year-old Hamlet after all. It would explain why the “thirty years” line is consistent in all subsequent versions of the play and why Heminges & Condell did not change it. Either that, or the Bad Quarto transcriber simply drew on what he knew of the play or story from other sources—maybe that Ur-Hamlet supposedly written by Thomas Kyd—that did have a teen Hamlet.

So yes, young Hamlet does make sense in almost all respects (except, ironically enough, his attending university—royals had private tutors and only nobility went to university). But as far as canon goes, Shakespeare had a darker purpose in mind. Either way, it’s not as if 30 is super-old either, and in this day and age, you’ll find plenty of 30-year-olds still under their parents’ thumb.

#moonlarked#ask#hamlet#hamlet meta#william shakespeare#either that or shakespeare just erm forgot his character was a teenager#i think we overestimate the fucks shakespeare gave when it came to age

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rundown on the Absolute Chaos that is First Quarto Hamlet

IMPORTANT UPDATE: This post may be getting a revamp with better citations—my cross-checking source was scrubbed from the internet entirely???

I said I was going to sleep before writing this. I did not. Here it goes anyway!

TL;DR: Multiple versions of Hamlet were printed between 1603 and 1623. Across these multiple texts, we get some fairly major differences in characterization and plot disparities. The First Quarto is most infamous for its oddness- which includes shockingly brief soliloquies, mother-son bonding, wild spellings of everyone’s names, and deleted/adapted scenes with major plot/character implications.

A full (long!) rundown is below the cut, including sources, transcribed Q1 content and lore, further Hamlet lore, and my fan theories! Feel free to skip the bits you don’t care about, I got way too into this.

Note: *I have updated these lines to their modern spellings for ease of reading

What is the First Quarto? What’s a “quarto”? Who wrote this?!

All pressing questions, my dear dedicated fan of William Shakespeare’s hit play Hamlet!

The First Quarto was published in 1603 and was (presumably, as implied by the name) printed as a quarto (a little book created by folding printed pages into four leaves- eight pages). It is much shorter than the later publications and is presumed to be transcribed from memory by an actor (probably the guy who played Marcellus), who may have been a member of a touring troop of actors performing the play.

Q1 is not necessarily considered a first draft of the play, but something of a “pirated” (by memory) copy that was later amended by Q2 and F1.

Are you saying that Hamlet comes with the stageplay equivalent of a “deleted scenes and extra credits” movie disc?

Yes! And not just one, but many: Quartos 1-5, the First Folio, multiple foreign language versions, and more! Your typical modern copy of Hamlet is a combination of the Second Quarto and First Folio.

Q2 (published in 1604 or 1605) is considered more “Shakespeare-accurate” than Q1- it seems to be a manuscript actually written by Shakespeare combined with an edited version of Q1′s Act 1 text rather than just some guy’s memory of the play. F1 was published much later (1623) and is some combination of another playhouse manuscript and possibly Q2 (but which—Q2 or the manuscript—had more influence in the creation of F1 is unclear). Q2 and F1 have tons of differences in wording and each has some content that the other doesn’t, but what you need to know here is that a typical modern script is an F1/Q2 combo (because editors didn’t think the public would want like six different scripts- fair enough.)

Quartos 3-5 are slightly edited versions of Q2. There seem to be a few other versions in different languages (like the German version) which share points from a variety of the above sources.

So... Q1? How is it any different from the version we all know (and love, of course)? What do the differences mean for the plot?

We’ll start with minor differences and build up to the big ones.

First of all, the language! Everything is spelled to the discretion of the transcriber, which produces gems such as “for England hoe.”

These spelling differences also extend to the characters! Laertes is “Leartes”, Ophelia is “Ofelia”, Gertrude is “Gertred” (or sometimes “Gerterd”), Rosencrantz is “Rossencraft”, Guildenstern is “Gilderstone”, and my favorite, Polonius gets a completely different name: Corambis.

(This goes on for minor characters, too. Sentinel Barnardo is “Bernardo”, Prince Fortinbras of Norway is “Fortenbrasse”, Voltemand and Cornelius- the Danish ambassadors to Norway- are “Voltemar” and “Cornelia” (genderbent Cornelius?/hj), Osric doesn’t even get a name- he is called “the Bragart Gentleman”, the Gravediggers are called clowns, and Reynaldo (Polonius’s spy) gets a whole different name- “Montano”.)

The stage directions include more detail! Ex: Ophelia enters in Act 4 with a lute to play along to her song of insanity. (*Enter Ofelia, playing on a lute, and her hair down, singing). (Some bits are missing direction though! In Act 3, when Hamlet calls upon Horatio to watch Claudius on the night of the play, there is no instruction for Horatio to enter the scene. He appears without being asked.)

There is a slight reordering of scenes in Act 3. Claudius and Polonius go through with the plan to have Ophelia break up with Hamlet immediately after they make it (typically, the plan is made in early II.ii and gone through with in III.i, with the players showing up and reciting Hecuba between the two events). In this version, the player scene (and Hamlet’s conversation with Polonius) happen after ‘to be or not to be’ and ‘get thee to a nunnery.’ I’m not sure if this makes more or less sense. Either way, it has minimal impact on the story.

Many lines, especially after Act 1 are considerably altered or shortened. Everyone is a lot more straightforward and (sometimes) a lot less iambic pentameter-y and poetic. A few examples: Laertes’ usually long-winded I.iii lecture on love to Ophelia is shortened to just ten lines (as opposed to the typical 40+). Polonius (er... Corambis) is still annoying and incapable of brevity, but less so than usual. His lecture on love is also cut significantly! Hamlet’s usual assailing of Danish drinking customs (I.iv) is cut off by the ghost’s arrival. He’s still the most talkative character, but his lines are almost entirely different in some monologues, including ‘to be or not to be’! In other spots, however, (ex: get thee to a nunnery!) the lines are near-identical. There doesn’t seem to be much rhyme or reason to where things diverge linguistically.

And then the big differences: the additional scene and Gertrude’s promise to aid Hamlet in taking revenge. Act 3, scene 4 goes about the same as usual with one major difference: Hamlet finishes off not with his usual declaration that he’s to be sent for England but with an absolutely heart-wrenching callback to act 1, in which he echoes the ghost’s lines and pleads his mother to aid him in revenge. And she agrees. Here is that adapted scene (without line breaks for some reason- ah, formatting!):

*Gertrude: Alas, it is the weakness of thy brain which makes thy tongue blazon thy heart’s grief: but as I have a soul, I swear by heaven, I never knew if this most horrid murder: but Hamlet, this is only fantasy, and for my love forget these idle fits.

Hamlet: Idle, no mother, my pulse does beat like yours, it is not madness that possesses Hamlet. O mother, if you ever did my dear father love, forbear the adulterous bed to-night and sun your self by little as you may, in time it may be you will loathe him quite and mother, but assist me in my revenge and in his death, your infamy shall die.

Gertrude: Hamlet, I swear by that majesty that knows our thoughts and looks into our hearts, I will conceal, consent, and do my best what stratagem so ever thou shalt devise.

Hamlet: It is enough mother, good night. [to polonius] I’ll provide for you a grave who was in life a foolish and prating knave.

*exit Hamlet with Polonius’s body*

Despite having seemingly major consequences for the plot, this is never discussed again. Gertrude tells Claudius in the next scene that it was Hamlet who killed Polonius (Corambis, whatever!), seemingly betraying her promise.

However, Gertrude’s admission of Hamlet’s guilt (and thus, betrayal) could come down to the circumstance she finds herself in as the next scene begins. There is no stage direction denoting her exit, so the entrance of Claudius in scene 5 may be into her room, where he would find her beside a puddle of blood, evidence of the murder. There’s no talking your way out of that one…

And now the most drastic change: the bonus scene. After IV.vi (act 4, scene 6), (but before IV.vii) comes this scene*, in which Horatio informs Gertrude that Hamlet was to be executed in England but escaped. Here it is with modern spellings but without line breaks (man, I hate formatting things!)

Enter Horatio & Gertrude

Horatio: Madam, your son is safe arrive’d in Denmark. This letter I even now received of him, whereas he writes how he escaped the danger and subtle treason that the king had plotted, being crossed by the contention of the winds, he found the packet (letter) sent to the king of England, wherein he saw himself betray’d to death, as at his next conversion with your grace, he will relate the circumstance at full.

Gertrude: Then I perceive there’s treason in his looks that seemed to sugar o’re his villainy: but I will sooth and please him for a time for murderous minds are always jealous. But know not you, Horatio, where he is?

Horatio: Yes, madam, and he hath appointed me to meet him on the east side of the city to-morrow morning.

Gertrude: O, fail not, good Horatio, and commend me a mother’s care to him, bid him a while be wary of his presence, lest that he fail in that he goes about.

Horatio: Madam, never make doubt if that: I think by this news be come to court: he is arrive’d, observe the king and you shall quickly find, Hamlet being here, things fell not to his mind.

Gertrude: But what became of Guilderstone and Rossencraft?

Horatio: He being set ashore, they went for England and in the packet there writ down that doom to be performed on them pointed for him: and by great chance he had his father’s seal, so all was done without discovery.

Gertrude: Thanks be to heaven for blessing of the prince, Horatio, I once again take my leave, with thousand mother’s blessings to my son.

Horatio: Madam, adieu.

If Gertrude knows of Claudius’s treachery (”there’s treason in his looks”), her death at the end of the play does not look like much of an accident. She is aware that Claudius killed her husband and is actively trying to kill her son and she still drinks the wine meant for Hamlet!

Now, the moment we’ve all been waiting for! My thoughts! Yippee!

Clearly, my favorite gift this Christmas was my copy of The Riverside Shakespeare, gifted to me by my grandma. I don’t think I’ll ever sleep again now that reading this is an option. (This play has me head-over-heels, goddamn!)

Anyway, here are my thoughts on Q1 (as abridged as I can get them, seeing as this post is already nearly 2,000 words long.)

On Gertrude: WOW! I’m convinced that she is done dirty by First Folio and Q2! She and Hamlet have a much better relationship (Gertrude genuinely worries about his well-being throughout the play.) She has an actual personality that is tied into her role in the story and as a mother. I love Q1 Gertrude even though in the end, there’s nothing she can do to save Hamlet from being found out in the murder of Polonius and eventually dying in the duel. Her drinking the poisoned wine seems like an act of desperation (or sacrifice? she never asks hamlet to drink!) rather than an accident.

On the language: I think Q1′s biggest shortcoming is its comparatively simplistic language, especially in ‘to be or not to be’*: (again with the formatting!)

Hamlet: To be, or not to be, aye, there's the point. To die, to sleep, is that all? Aye, all: no, to sleep, to dream, aye, merry there it goes. For in that dream of death, when we awake, and borne before an everlasting judge, from whence no passenger ever returned, the undiscovered country, at whose sight the happy smile, and the accursed damn'd. But for this, the joyful hope of this, who’d bear the scorns and flattery of the world, scorned by the right rich, the rich cursed of the poor? The widow being oppressed, the orphan wrong'd, the taste of hunger, or a tyrants reign, and thousand more calamities besides, to grunt and sweat under this weary life, when that he may his full quietus make, with a bare bodkin, who would this endure, but for a hope of something after death? Which puzzles the brain, and doth confound the sense, which makes us rather bear those evils we have, than fly to others that we know not of. Aye that, O this conscience makes cowards of us all.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s good, but it doesn’t feel quite complete, which makes sense for Q1- that’s the vibe I get overall from this version: it’s Hamlet at an earlier point in the play’s journey to becoming its modern renditions and compilations.

On the ending: The ending suffers from the same effect ‘to be or not to be’ does- it is simpler and (imo) lacks some of the emotion that F1 later emphasizes. Hamlet’s final speech is significantly cut down and Horatio’s last lines aren’t quite so potent- although they’re still sweet!

*Horatio, to Fortinbras and co.: Content yourselves, I’ll show to all, the ground, the first beginning of this Tragedy: Let there a scaffold be reared up in the marketplace, and let the State of the world be there: where you shall hear such a sad story told that never mortal man could more unfold.

Horatio generally is a more active character in Q1 Hamlet. This ending suits his character here: He will tell Hamlet’s story, tragic as it may be. It reminds me a bit of We Raise Our Cups from Hadestown.

Overall, I loved reading this version and highly encourage you to do the same! (Two PDFs are linked below!) The spelling is hard to overlook at times, but if you can get through it, this is a fascinating interpretation of the same Hamlet we love and it’s worth a read! There’s so much more I want to get into but I absolutely must sleep, so adieu for now!

And finally, my sources:

The Riverside Shakespeare (pub. Houghton Mifflin Company; G.B. Evans, et al.)

Q1 PDF (Internet Shakespeare) https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Ham_Q1/complete/index.html

***THIS SOURCE NO LONGER EXISTS.*** Q1 PDF (STF Theatre) https://stf-theatre.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/HAMLET-%E2%80%93-the-1st-Quarto.pdf (cross-reference for lines)

#Hamlet#shakespeare#first quarto hamlet#oh man i am tired#definitely entered my unhinged college student era#classical literature#you will be the death of me!#this will be edited for clarity and punctuation later

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

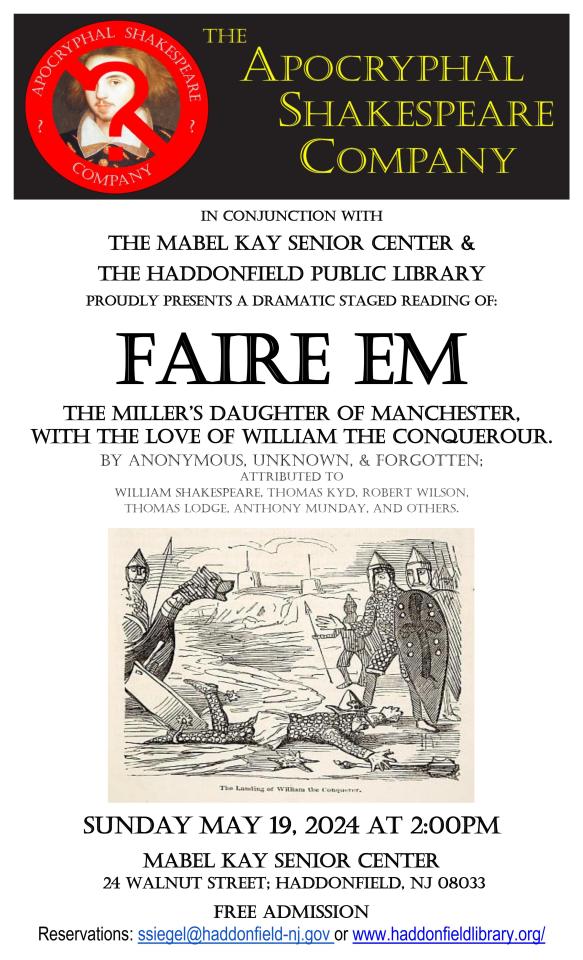

Fair Em, The Miller’s Daughter of Manchester

Director’s Notes:

The First Quarto of Fair Em, The Miller’s Daughter of Manchester is undated; however, its title page boasts that the play “was sundry times publicly acted in the honorable city of London by the right honorable the Lord Strange his servants.” The Lord Strange’s men performed in London from 1589 to 1593; so, we can place an estimated date of 1590 on Fair Em. This places Fair Em at the very beginning of Shakespeare’s career as a playwright and in the middle of Thomas Kyd’s and Christopher Marlowe’s.

Fair Em is actually two comedies in one. In the first story, William the Conqueror attempts to steal his best friend’s fiancé, Mariana. Moreover, he expects his friend to help him do it! But Mariana outwits them both and stays true to her man. In the second story, Fair Em is courted by four different men. She remains true to her first love, Manvile, and pretends to be deaf and blind to discourage the other suitors. Unfortunately, Manvile is also fooled and dumps Em to run off with a rich girl from the next town. Both plots play in alternating scenes until in Act V all the characters confront each other and the question of “true love” together. In both storylines we find that (as in real life) women are strong, intelligent, resourceful, loving, constant beings; while men are shallow, self-centered, sexist, idiots.

Fair Em has situations and complications that remind us of Shakespeare and Kyd. For example, Kyd wrote strong and faithful female characters such as Bel-imperia in The Spanish Tragedy. Likewise, Shakespeare gives us the fidelitous heroines of All’s Well That Ends Well, or The Winter’s Tale as compared to their fickle or jealous male counterparts. Moreover, in Two Gentlemen of Verona Shakespeareargues that the bond between two male friends certainly outranks the love between a man and a woman. After all, if you can’t make love to your best friend’s girl, who can you make love to?

Unfortunately, the surviving copy of Fair Em is a “Bad Quarto.” Whether written by Kyd, Shakespeare or the great Anonymous, we will never know what the full original script was like. Judging the merits of the lost original Fair Em based upon our surviving version would be like judging the merits of Hamlet based only on the 1603 “Bad Quarto” of Hamlet. They are both good plays and quite entertaining, but the mutilated versions no longer touch the peaks of excellence.

We hope you enjoy our production of Fair Em, The Miller’s Daughter of Manchester.

Douglas L. Overtoom

0 notes

Text

(Long Post quoting) NY Review of Books:

This year marks exactly four centuries since the publication of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, the giant two-volume set of thirty-six plays that reframed his work in “overtly literary terms,” as Catherine Nicholson puts it in our Sixtieth Anniversary Issue. Nicholson’s writing about Renaissance literature—including in books on the formation of a vernacular tradition (Uncommon Tongues: Eloquence and Eccentricity in the English Renaissance) and on The Faerie Queene (Reading and Not Reading The Faerie Queene: Spenser and the Making of Literary Criticism)—flashes with a rare combination of historical precision and fresh insight. Her essays for the Review so far include considerations of Edmund Spenser, John Milton, and what we’re able to know about childhood in the sixteenth century; a characteristically sharp line on Milton notes that his “nonchronological narrative design” in Paradise Lost “teases us to think, perhaps God is Eve-like.”

Nicholson’s essay on the First Folio, “Theater for a New Audience,” traces the contingencies that have helped to shape our idea of Shakespeare through the big posthumous book of his plays, revealing among other things how our understanding of foundational texts can be enlarged by studying the history of their reception. It also touches on a number of literary questions that could have formed a separate essay on their own, and this week she discussed a few of them with me via e-mail.

-Catherine Nicholson

Jana Prikryl: We have no evidence that Shakespeare, who died in 1616, had anything to do with the First Folio, which was published in 1623. In your essay you criticize Chris Laoutaris’s Shakespeare’s Book for speculating that the Bard himself instigated the folio project. It’s tempting to imagine something of the sort, since otherwise we have a Shakespeare who was recklessly indifferent to the survival of his own work. What’s your own theory for why he, as you put it, “seems to have had no such ambition”?

Catherine Nicholson: I’m not sure we need to think of Shakespeare as recklessly indifferent to the survival of his plays so much as possessed of a different sense of what survival might mean—firstly in the repertory of the King’s Men, and only secondly in the market for print. And survival within a theatrical repertory often entailed a great deal of change: lines, scenes, characters, and so on might be altered, cut, or added as a script was adapted to the resources of the playing company, the shifting tastes of audiences, and the demands of a particular performance occasion. The playwright might be enlisted in making those changes, or he might have no say at all. Since, at the time, playscripts were the legal property of playing companies, publication happened at a still further remove from authorial control. The version of a play fixed in a printed edition might be the one the playwright intended or preferred, or it might simply be the one the printer could get his hands on. And many, many plays never made it into the hands of any printer: the diary of the Elizabethan impresario Philip Henslowe mentions 280 plays, of which thirty survive in print. Some may have been printed and then lost, but it seems clear that most plays written in Shakespeare’s lifetime lived exclusively in the theaters.

That environment must have shaped Shakespeare’s relationship to his work. No doubt he did sometimes find it frustrating to have his words altered without his say-so. Hamlet’s irritable injunction to the players—“let those that play your clowns speak no more than is set down for them”—gives us a glimpse of the sometimes fraught relations between writers and performers, especially those with the most license to improvise on stage. But that speech itself runs quite a bit longer in the 1603 quarto (Q1) than it does in the 1623 folio: in 1603 Hamlet goes on to recite a string of random comic catchphrases exactly like the ones he doesn’t want forced into his own play. I don’t have an opinion on which version of the speech belongs in a modern edition or performance: the folio version is certainly more elegant and concise, but the ironic effect in Q1 is one I cherish; it suggests that Shakespeare was wont to poke fun at any impulse toward authorial control, even his own.

I have a similar response to, say, Sonnet 55, which begins, “Not marble nor the gilded monuments/Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme….” That poem channels the voices of Ovid and Horace to make an extravagant claim for the undying power of Shakespeare’s verse, and it’s hard to read today without a shiver of appreciation and awe: he was right (so far)! But when I teach the Sonnets, I always point out to students that these are poems that circulated in manuscript for over a decade before making their way (with or without Shakespeare’s knowledge and approval) into print; moreover, they are in a poetic form that already, in the mid-1590s, was a bit passé and in a vernacular almost no one outside of England spoke or read. The idea that these verses would retain their meaning and value for all time—“Even in the eyes of all posterity/That wear this world out to the ending doom”—has got to be shot through with some pathos, implausibility, or even humor.

Can you talk a bit about the kinds of new readings that became available after the plays moved from performance to the page?

In some sense, the shift from playhouse to page must have seemed like an impoverishment: the media of performance are so vivid and multisensory in comparison to the medium of text. One of my favorite recent works of scholarship on early modern drama is Claire Bourne’s Typographies of Performance in Early Modern England (2020), which reveals how painstaking and ingenious early modern printers were in devising typographic conventions to make playbooks legible both as books and as plays. At the turn of the sixteenth century, the resources for communicating dramatic structure and dramatic action were limited: the first playbook printed in England, a Latin edition of Terence’s Comedies, included an editorial note telling readers what an act and a scene were and urging them to imagine actors moving on- and off-stage as they read. By the time Shakespeare’s plays were being published, printers had devised an incredibly sophisticated repertoire of typographic conventions, from act and scene divisions to speech tags, italicized stage directions, printed marks like dashes and pilcrows (the symbol that marks a paragraph break), and woodcut illustrations, all of which helped readers to imagine the text in performance.

But printing a play also creates all sorts of new opportunities for engaging with it, beyond the shared temporality of performance: reading a bit at a time, for instance; stopping to look something up; marking and returning to a favorite passage; noticing the recurrence of an image, phrase, or word across a wide expanse of text; annotating in the margins or copying passages out into a commonplace book. Add those modes of readerly engagement together, and you begin to get something like literary criticism: an approach to a play that can coordinate character and plot with features of the text that would be hard to pause over or even register in performance.

To what degree Shakespeare anticipated or sought that kind of engagement from readers of his plays is an open question. In his 2003 book Shakespeare as Literary Dramatist, the scholar Lukas Erne argues that the length of a number of Shakespeare’s plays suggests he wrote them, at least in part, with print publication in mind, lavishing care on passages he knew would likely never make it on stage. On the other hand, maybe the length of the plays as written reveals that Shakespeare was far less precious about his own words than we tend to be; he knew they might be cut and adapted for performance, and he wrote freely in expectation of that winnowing. In either case, the looser, nonlinear, potentially discontinuous temporality of reading allows for all sorts of lingering and reading across or against the narrative grain that I, at least, can’t fathom doing without. And the First Folio encourages that kind of reading—not simply of each play, but of the plays as a dynamic and interrelated whole.

In the first piece you wrote for the Review, on Edmund Spenser, you called The Faerie Queene “the emblematic textual commodity of an age in which book ownership expanded from the domain of aristocrats and scholars to become a bourgeois expression of taste.” When the First Folio was published twenty-six years later, would you say it was comparable in status?

I’d guess that both the 1590/1596 quartos of The Faerie Queene and the 1611 folio of Spenser’s Works were more immediately recognizable to readers and book buyers as prestige literary commodities. The full title of the latter—The Faerie Queen: The Shepheardes Calender: Together with the other Works of England’s Arch-Poët, Edm. Spenser: Collected into one Volume—takes for granted both the author’s preeminence among English poets and the value of assembling his writings into a unified corpus. Contrast that with the mocking reception in some quarters of the 1616 folio of Ben Jonson’s Works (“Pray tell me Ben, where doth the mistery lurke?” inquired one anonymous wit, “What others call a play you call a work”), which suggests the difficulty seventeenth-century readers still had in conceiving of vernacular stage plays as literature.

But there’s a nearly seventy-year gap between the first and second folios of Spenser’s Works, while the Second Folio of Shakespeare’s plays appears just nine years after the first, in 1632. And by the middle of the eighteenth century, their fortunes have decisively crossed: The Faerie Queene is, increasingly, a book to own—or, perhaps, to study—but not to read, while editions and adaptations of Shakespeare sell in a wide variety of formats and at a range of price points. In that sense, too, textual fixity or bibliographic iconicity isn’t the same as influence or survival: change remains the lifeblood of literary tradition.

I don’t want to give away the brilliant ending of your piece, but its reading of The Tempest made me think of other times in the plays when characters rely overmuch on textual sources: the several letters intercepted in King Lear, the fatefully undelivered letter from Friar Laurence in Romeo and Juliet, the comically bad poems Orlando pins to trees in As You Like It…. Is it too much to say that it seems, in Shakespeare’s worlds, as if things written down are inferior to those acted out?

I don’t know about inferior—Shakespeare is keenly alert to the perils and pitfalls of dramatic reenactment—but certainly subject to error and misapprehension. Sometimes those misapprehensions are disastrous; other times (I’m thinking of poor Malvolio deciphering what he believes to be a love letter from Olivia, in Twelfth Night) they are deliciously comic; occasionally, as with the letter that mysteriously surfaces in the final moments of The Merchant of Venice, restoring Antonio’s lost fortune, they are redemptive. Like Spenser, Shakespeare seems to delight in scripting encounters that anticipate the possibility of his own misreading by others, and misreading is not always figured as a catastrophe; sometimes it offers the wayward path to a happy ending.

#refrigeratormagnets

#shakespeare#william shakespeare#playwright#first folio#plays#dramatist#refrigerator magnets#refrigerator magnet#for educational purposes only

1 note

·

View note

Text

24 years old Ian performed in Fratricide Punished in October 1958, a Stage play by William Poel adapted and produced for broadcasting by Peter Dews. Loosely related to the Quarto version of Hamlet it stars Mark Kingston as Hamlet, Janet Hollander as Ophelia and Ian Richardson as Francisco, Jens and Leonhardus. I don't know how mum has got all these pictures. I know she started seeing the plays at the Rep in 1958. She has had the good fortune to see the very first Hamlets of Ian (1958) and Derek (1959)

#ian richardson#birmingham rep theatre#Fratricidepunished#young british artists#shakespeare#the rsc#shakespearian actors#great british actors#royal shakespeare company

1 note

·

View note

Photo

—Edward Mendelson, “Life, Death, This Moment of June”

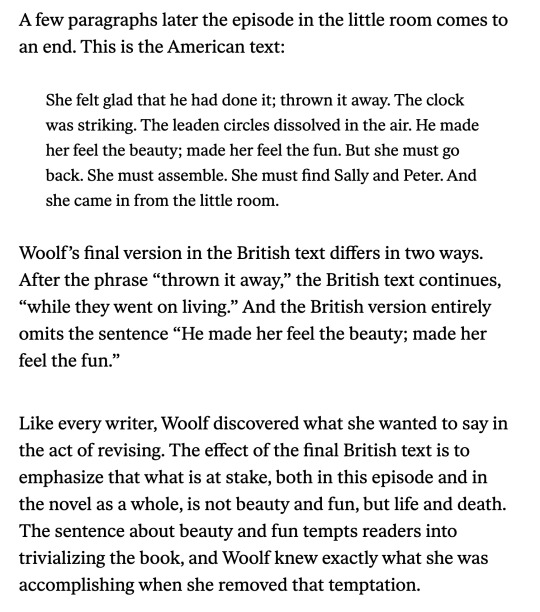

Mendelson reviews two new post-copywright Mrs. Dalloway editions—the Norton Critical (ed. Anne Fernald) and the Liveright “Annotated” (ed. Merve Emre), neither of which I’ve seen yet. Though sometimes I don’t want vast scaffolds of editorial apparatus if a book can be read, more or less, without them. Mendelson lucidly observes the reductionisms of too-much-information or not-the-right-information or why-is-this-relevant-information such volumes tend to imply. Historical context? What is it but everything that’s ever happened, what George Eliot labeled “that tempting range of relevancies called the universe”? I’ve never seen a photo of the woman Woolf based Clarissa on; I’m not sure how it would help me to read the novel if I had, though Emre includes one in her edition.

At the heart of the review, part of which I screenshotted above, Mendelson objects to Emre’s heavy editorial hand. She conflates, in the novel’s most crucial scene, the American and British texts, though the latter, finalized later, is more somber and weighty. I agree with his critique of Emre’s editorial practice, though she must have justified it to herself by saying that Shakespeare’s editors do this kind of thing all the time, so why not Woolf’s editors? Most cheap paperback editions of Hamlet, for example, run the Second Quarto and the Folio texts together on the principle “the more Shakespeare, the better,” even though this conflation creates inconsistencies in plot and characterization.

I do not agree with his critical judgment on Woolf. “He made her feel the beauty, made her feel the fun” is more complex, truer to life, scandalously accurate, whether the moralist finds it trivial or no. She lost her nerve when she took that line out for the British version. I concluded the essay I wrote on Mrs. Dalloway for my website in 2018—not to be confused with my 2013 dissertation chapter on the novel—with reference to teaching this particular sentence:

This passage never goes well in the classroom—in a social setting, neither I nor the students can get past condemning Clarissa here, though every honest person knows just how she feels. I had a good moment with it the other day, though. I said to the class, “Who approves of Clarissa’s reaction?” They looked at me blankly; no one raised a hand. “Who disapproves of it?” I asked, imagining I would get a livelier response. But they still looked at me blankly, and only one or two hands straggled up. Finally, I said, “Who knows you’re supposed to disapprove of this, but the complexities of human emotion being what they are, you see where Clarissa is coming from?” Most hands shot into the air, and one student even exclaimed, “Oh yeah, definitely!” I call that a victory for aesthetics, and I imagine the pupil of Clara Pater and the self-elected sister of Shakespeare smiling slyly somewhere further back or further on in the stream of time.

Mendelson doesn’t class Woolf with Shakespeare. Following Auerbach’s Mimesis, he prefers the almost more august company of the epic poets: Homer, Dante, Goethe. I think placing her in this rather masculinist lineage misses something of her feminist anti-epic stance; the fluidly imaginative dramatist and lyricist Shakespeare, with all of his own beauty and fun, really does seem her truer companion. Mendelson also champions her against Joyce. He writes:

One of the ways Woolf made Mrs. Dalloway more profound and more disturbing than its model Ulysses was by adding Septimus’s chosen death. No one in Ulysses is threatened with death; the deaths that occurred in the past were all natural ones; Leopold Bloom’s most dangerous moment occurs when someone throws a biscuit tin at him and misses.

But this is wrong on one point of fact and, more broadly, on the modernist epic’s general political tenor. First, Bloom’s father, Virag, did not die a natural death but rather took his own life, not unlike Septimus. Second, the two episodes of comic violence in the novel—the nationalist’s would-be assault on Bloom and the English soldier’s attack on Stephen—have their deadly serious dimension. Each stands for forms of world-historically lethal violence: that of anti-Semitism and of British imperialism, respectively.

Which isn’t to say that modernism’s two great day-in-the-life novels can’t be productively or amusingly compared. I wrote an essay on just this theme for Bloomsday 2018 and made my own case for Woolf:

Though Ulysses scrupulously if rather literally mimics the dream-state in “Circe,” which is a just a warm-up for Finnegans Wake, Mrs. Dalloway, with its transience of perception from character to character across expanses of consciousness as well as social space, is the more winningly dream-like achievement. It is Joyce’s formalist literalism, his resolute commitment to achieving every (sometimes inorganic) experiment, that Woolf lacks: this is what she means in her censure of the “tricky,” and I think she is more right than wrong.

But, I conclude, we don’t have to choose between works on this level of literary achievement. Fictions that make themselves so central crystalize whole modes of perception, styles of sensibility, epochs and cities, ethical climates. As a reader, in most moods I prefer Ulysses, while as a writer, I am much closer to the Woolf of Mrs. Dalloway. Obviously, we need them both, or at least I do.

#virginia woolf#edward mendelson#merve emre#james joyce#literary criticism#modernism#british literature

1 note

·

View note