#hölderlin

Text

What lives is indestructible, stays free in its most deeply servile form, stays intact and though you split it to the ground, stays unscathed and though you shatter it to the marrow, and its essence flies away in triumph through your fingers.

Hölderlin, Hyperion (1799)

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Apollo (5)

And here is the last part of Françoise Graziani’s article « Apollo, the mythical sun » (begun here).

IV/ The mystical Sun

The interpretation of the Sun as a symbol of royalty was already present during the Renaissance but was truly amplified by the baroque era. This iconological interpretation was first punctually associated with the panegyric (Ronsard in his “Elegies” wrote “Henry, the Sun that inspired me”), then to the emblematic, as the royal crown was depicted as a crown of sun-rays. While Tyard saw a positive symbol within the idea of the Sun “Prince and rector of the sky”, the baroque poet Drelincourt, in 1677, compared it to a “superb King, who shines in his Court, Crowned with rays” – but only to better accuse the celestial body of being a simulacra of God, a “weak painting”. Within the same idea, Du Bartas substituted the false pagan god to the real God: “The world is a cloud through which shines, not the bow-shooting son of the beautiful Latone, this divine Phoebus, but…”. It is very revealing that Drelincourt presents a critical and desacralizing interpretation of the sun, where it loses its mythical name and function… while writing within the court of Louis XIV, right as the king ideologically concretizes the literary allegories by depicting himself within Versailles (the “house of the Sun”) as Apollo, as the sun on earth. Drelincourt concludes his sonnet “About the Sun”, by insisting that the Sun is just the “portrait of the Primal Cause”: “your brightness is but a Shadow, and you are not the Sun anymore”. The mythical Sun is a false sun, but it is replaced in the metaphorical heaven by the real mystical Sun, the Christ, that the Renaissance paintings sometimes depicted under the traits of Apollo. As a reflection of the true God, as the interpret and the vehicle of God’s light, the Christ was a solar character, whose death was thought as bringing a “night” to the Western world (it was how the poets metaphorize the eclipse that occurred during the Crucifixion). This identification, very common within the mystical baroque poetry, was sometimes pushed to the point of including (in a very unusual way) some episodes of Apollo’s legends within the Christian allegory (such as Hyacinthus or Clythia).

V/ The Sun of intelligence

The mystical sun is, in a paradox that determined all poetic interpretations, linked to the decline of the mythical sun. And yet, the mystical sun is born from a very old topos, the one of the Deus Pictor: if God is a painter, and the Universe his painting, than the Sun (and the poets claim it since the Hellenistic times) is his brush. In the baroque era, the solar myth, heavily used in a metaphorical (not quite allegorical) way, leads this motif towards the realm of abstractions. Every time it appears, it is linked to two elements: on one side, the Sun as a divine principle and an instrument of creation which becomes the double of the poet (a poet that now dares associate himself with not just Orpheus, but Apollo). On the other side, the diurnal travel of the solar eye becomes the metaphor of the process of writing. Numerous baroque texts play on the similarity between the words “rayons” (the rays) and “crayon” (the pencil), to show the Creator in his picturesque and scriptural functions. In a similar way, it is traditional to punctuate long poems by various sunsets and sunrises, described in such a way that they establish an analogy between the rhythm of the days, and the rhythm of the poem itself.

It is for example the case within G. B. Marino’s “Adone”, where, at the end of the poem, the Muse answers Apollo’s call, and comes to “end the thread of this long canvas”, and the end of the last day is described in textual terms: “The sky is of paper, the darkness of ink, the ray a feather / Which with the sun erases the ending day to write / to the West, in letters of gold, the end of the long travel.” Within “Adone”, Apollo is present under different shapes. He is found, in a metaphorical way, in the character of the hero, Adonis, which ultimately is just a gaze that crosses the various spectacles of the universe (celestial world, terrestrial world, cultural world) and is often compared, due to the “shine of his youth”, to Apollo. As the sun is the eye that brightens the world, that reveals the world and that allows it to be, the first creating gaze over the poem is done by the poet itself ; but there is another sight, the image of the human eye that reads and interprets the great Book of Nature. Adonis, within Marino’s poem, plays this role of reader, the double of the creature to which the secrets of the creation are hidden. He is, too, a “false sun”, and this is why Marino show him as a passive hero who, throughout the poem, does not understand what he sees: it is a reverse image of the philosophical sun of the Renaissance. He symbolizes the human soul, in the idea that the human soul only perceives the appearances, and mistakes itself for the sun because it was created in tis image. Marino’s Adonis is a “lonely eye” to which the gods (Venus and Hermes) reveal secrets, but the only world that receives the light of his gaze is the one of the book, of which the real writer is Apollo, “he who brightens the wise minds”. He who shines upon the minds embodies the last avatar of the god of Poetry: the divine Intellect, he who makes the minds shining and insightful, he who gifts human with both invention and divination. The solar sign valorizes the human Intellect, and more so over the individual intelligence. The god doesn’t “inspire” anymore, but he does more by “shining” upon the artistic works.

Apollo is more and more disguised as time passes by, to the point of losing his name – he is substituted so much he is even refused the qualificative of a god. He keeps however, as a mythical sign, a great coherence. The abstract uses of the Sun as metaphors for the divine eye contain very clear remains of its mythical nature. The connotations tied to the solar figure are simply the transpositions, on a metaphorical plane, of the elements tied to the god. The frequency of his use throughout the 16th and 17th centuries proves its almost ritualistic value, even though literature splits itself from the myth. As such, it seems that, as soon as the poetry does not bear the myth of the inspiration anymire, the figure of its titular god is slowly abandoned. Even though the invocation of the Muses persists, as a convention or as a periodical element, all the way to the 19th century. The names of “Apollo”, “Muses” and “Lyre” are enough to designate, by metonymy, and outside of all myths, the very concept of poetry.

VI/ Hyperion

With Romanticism, Apollo becomes the Archer again. The divine inspiration of the poet is not an illumination or a revelation anymore, but a shock, a stupefying possession. The poet, as Hölderlin writes, is “struck by Apollo” and, confronted by the presence of the god, he can’t be understood by other humans anymore. The poetic vocation is assimilated to a curse, and to a suffering. Within Hölderlin’s work, Apollo is fused with both Jupiter, he who strikes with the blinding lightning, he who “shakes and vivifies”, and with Dionysos, to condense itself ultimately in the figure of the Christ. He also especially identified with the one who was, according to Hesiod, his grand-father, the titan Hyperion. Just like Hyperion, of which he bears the name in the allegorical novel of Hölderlin “Hyperion”, the poet is a fallen and exiled titan, whose rebellion (pre-apollonian actions) are doomed to failure, but who keeps the vague memory of his solar origin and of his mission, while still being, like the sun, doomed to loneliness. A loneliness which, in this context, bears both a positive aspect, as the solitude which brings exaltation, and a negative aspect, the solitude which makes the poet a cursed man or a mad man. Apollo and Dionysos become one within the Romantic conception of madness as a sign of both divine election and mystical drunkenness. The fundamental ambiguity of Apollo is found back within the duality of the poetry, perceived as both a grace and an eviction. This duality was felt by the Romantics on an individual plane, and not on a conceptual plane like in the Renaissance.

An exceptional occurrence of the figure of Apollo within literature must be studied, quite close to Hölderlin’s own interpretation. Apollo appears as the subject and the hero of a 19th century literary work in only one piece, an unfinished poem by Keats which was also called Hyperion (1819). This brief epic of a Miltonian style depicts the fall of the Titans, banished by the New Gods, and the rise to divinity of the young Apollo, initiated by Mnemosyne. Within Keats’ writing, just like within Hölderlin’s work, Apollo is treated as the symbol of a “new beauty”, and as the tutelar god, not to say the embodiment, of the New Poetry. For both men, the accent is put on the “divine future” of Apollo: for Keats, Apollo only becomes a god when, thanks to Mnemosyne (who is in mythology the mother of the Muses), he understands his divinity, and this accession to Knowledge is a painful process. Apollo, before striking the poets, suffers himself from an “agony as burning as death is cold”. And he screams painfully when he was his epiphany. Within Hölderlin’s, the name Hyperion symbolized, by an antonomasia, the splitting of the hero, a hero turned to the Ancient Gods, that feels himself as their interpret, and yet is destined to inaugurate the renewal of the Teenager Sun through a New Poetic Religion. The poet which is speaking here is not yet born, and Hyperion represents the mythical prehistory of he who will only become a god, a pure lonely spirit, the “Hermit of Greece”, free of all heroic temptations, only after Romanticism. In a similar way, Keats brutally interrupts his poem right as Poetry is born.

#the myth of apollo#apollo#hyperion#greek mythology#poetry#greek gods#symbolism#sun#titans#keats#hölderlin#christianization of greek myths#greek myths#poetic symbols#literary myths

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

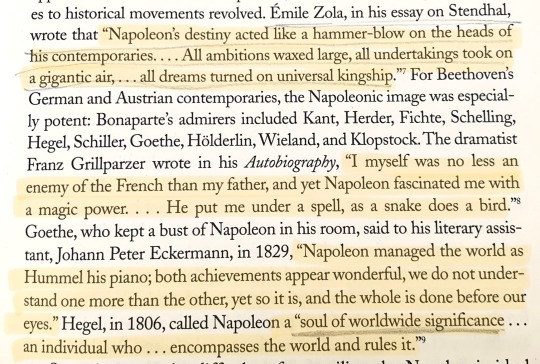

German and Austrian contemporaries of Napoleon (plus one by Émile Zola in his essay about Stendhal, a French contemporary):

Source: Beethoven, by Maynard Solomon

#napoleon#quotes#book#book pic#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#napoleon bonaparte#Kant#herder#Fichte#schelling#Hegel#Schiller#Goethe#friedrich hölderlin#hölderlin#wieland#klopstock#grillparzer#franz grillparzer#émile zola#Zola#Stendhal#Beethoven#france#history#frev#immanuel kant

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

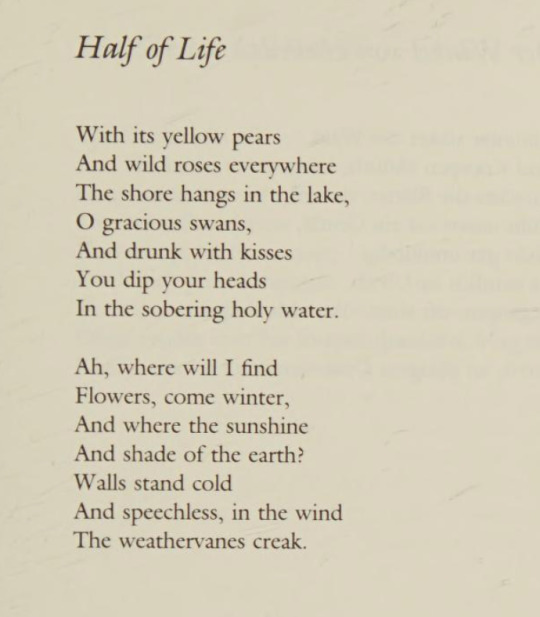

Friedrich Hölderlin, from Hymns and Fragments (translated by Richard Sieburth)

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst

Das Rettende auch.

Hölderlin

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

"En la época del seminario, Hegel soñaba con escribir un gran libro sobre Jesús y la religión del amor. Al igual que Hölderlin y Schelling, rechazaba la idea de que la fe es un saber inferior, o de que implica la sumisión a una autoridad. La fe equivale para él al espíritu libre, que se une vivamente con lo creído. Del mismo modo que solo el espíritu puede conocer al espíritu, sólo el que cree en lo divino tiene en sí lo divino."

- Rüdiger Safranski "Hölderlin o el fuego divino de la poesía"

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jenny Gröllmann, actress from the GDR who played Hölderlin's love in the film Hälfte des Lebens in 1985.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

sen insan değil, inan bana, sen bir dünya arıyordun.

friedrich hölderlin - hyperion

#hölderlin#friedrich hölderlin#hyperion#felsefi yazılar#felsefe blog#felsefe#platon sokrates#sokrates'in savunması#sofist#platon#herakleitos#nietzsche ağladığında#friedrich nietzsche#susanna tamarro#buket uzuner#charles bukowski#kitap kurdu#kitap blog#kitaptavsiyesi#oblomov#küçük iskender#küçük prens#yılmaz güney#ahmet altan#içimizde bir yer#yaşar kemal#gabriel marcia marguez#blog#blogger#şiir

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hölderlin: Az élet fele útján

Sárga virággal és vad

rózsákkal rakva csüng le

a part a tóba,

ti nyájas hattyuk

és részegen csóktól

a józan és szent vízbe

mártjátok fejetek.

Jaj nékem, hol kapok én, ha

tél jön, virágokat és hol

napsugarat

és árnyékot a földön?

Falak merednek

szótlan s hidegen a szélben

csörögnek a zászlók.

fordította: Kosztolányi Dezső

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friedrich Hölderlin, Hyperion

#Friedrich Hölderlin#Hölderlin#Hyperion#quotes#quote#romanticism#german romanticism#literature#lit#german literature#1800s#1800s literature#19th century lit

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

With us, everything is concentrated on the spiritual, we became poor so that we could become rich.

Hölderlin, Communism of Spirits

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

denkst du lenz und hölderlin würden viben?

auf jeden fall !!

erstmal schon wegen grundlegenden gemeinsamkeiten wie dass sie viel und oft wandern, nähe zu religiosität und wahnsinn vor allem da denke ich dass es oft momente gibt in denen man nicht verstanden wird aber sie würden sich verstehen

außerdem sind die beiden sehr klassizistisch unterwegs. zwar hat lenz eher lateinische literatur übersetzt, statt griechische wie hölderlin, aber er konnte auch sehr gut griechisch und hat (wie hölderlin) antike stoffe stark rezipiert (bei den übersetzungen natürlich, aber auch in seinen gedichten zb piramus und thisbe oder pygmalion oder generellen anspielungen die er in seinen werken macht).

vor allem denke ich aber, dass ihr kunstverständnis ähnlich ist, was natürlich ein bisschen schwer zu vergleichen ist, weil zetilich zwischen den beiden viele für die entwicklung der philosophischen ästhetik wichtige schritte liegen. die 1770er, 80er und 90er waren einfach die prime time für die ästhetik.

kurz gefasst: lenz sieht die kunst als "erste[n] trieb" der menschen wie gott zu schöpfen, nachdem sie das schöne in der natur erfahren haben, was "der Beweis eines unendlich freihandelnden Wesens ist" [Anmerkungen über das Theater - Lenz]. für hölderlin kann die freiheit, die für ihn die den menschen eigentümliche eigenschaft ist, die wir verwirklichen müssen um die höchste glückseligkeit zu erlangen, nur durch das erfahren und damit einhergehende schaffen von schönheit d.i. kunst erreicht werden. das ist jetzt ganz grob zusammengefasst haha aber viele der gedankengänge findet man im hyperion und da vor allem auf der überfahrt nach athen und wenn ihr sonst nichts von hölderlin lest dann doch bitte das <3 [für die fahrt nach athen müsst ihr einfach nach ganz unten scrollen, es ist das letzte kapitel in dem teil]

sie sind auf jeden fall unterschiedliche menschen aber sie sind beide klassizistische idealisten also abschließend ja ich denke sie würden viben !

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ho vissuto poco, ma respira fredda / già la mia sera. / E silenzioso già simile all’ombra / io sono qui.

Il lato piacevole di questo mondo l’ho goduto. / Le gioie della gioventù sono trascorse da tanto tempo! […] io non sono più nulla, io non vivo più volentieri.

Hölderlin

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

HANGİ TAŞ EZDİ SENİ, TADIN BÖYLE GÜZELLEŞMİŞ?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Often the worlds inner-ness seems clouded, closed/

Hölderlin, Aussicht, 24. 3. 1871

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

So freigiebig, wie die Sonne mit ihren Strahlen, will ich nicht seyn; meine Perlen will ich vor die alberne Menge nicht werfen.

Friedrich Hölderlin: “Hyperion”, S.93

#friedrich hölderlin#hölderlin#hyperion#freigiebigkeit#zurückhaltung#perlen vor die säue#alberne menge

31 notes

·

View notes