#how do i explain all of this to someone who thinks im relatively sane

Note

hey, i have a sister who struggles with addiction. she moved out from our parents to my place when she turned 18, so that she could have some space and that her highs and lows wouldnt affect our younger siblings that much. but shes been going through a hard time for quite long now, which causes her to treat us around her like complete shit. her behaviour led into a pretty bad argument, which led to me driving her to our parents in the middle of the night cause i couldnt mentally or physically handle the shit she was giving me anymore. after that night, she never returned to mine and told our parents to pick her stuff and move it into a new apartment that she got for herself (which locates in the same building as her friends who she uses substances with). she hasnt reached out to me at all, even though we have been around each other and i cant bare to approach her either, cause im still upset and hurt. my mom said that shes already prepared to lose her. i heard from her friends that shes told them that if she goes unconscious, theyre not allowed to call the ambulance or try to help her. i am worried sick to my stomach everytime i think about her and i feel so powerless. my parents just say that theres nothing more we can do, she goes to psychotherapy and shes under the social services but still i feel like we should do something more to help her or to stop her from destroying herself. im so sorry if this message makes you feel uncomfortable, but since ive followed you for quite awhile and i know your experiences with these things, i would appreciate if you could help me with this situation or at least try to give me some advice, how to cope with these feelings that come from loving your sister that struggles. i dont want to lose her.

hey, i am so sorry to hear this. there's a lot i could say and a lot i want to say but can't really articulate. i don't think there's any one size fits all advice for such a complex and heartbreaking situation. i guess i'll begin with what i'm sure of, and that is that your boundaries and feelings are justified. addiction literally rewires your brain and perception of the world beyond recognition, to the point where the only thing the person cares about is their vice. it's just total tunnel vision, selfishness denial and violence on top of selfishness denial and violence. being around ppl like that, especially a loved one, is beyond exhausting, it's its own special kind of hell. like screaming at a brick wall. it's totally understandable that you had to take a step back after falling victim to her erratic, manipulative and abusive behaviour. the drug use explains it but it absolutely does not excuse it. you're really brave for putting your foot down and prioritizing your own mental stability when it all got to be too much. know you never have to regret that. having said that, it's possible for two conflicting feelings to coexist and for them both to be (for lack of a better word) valid. she's your sister - of course you're worried, of course you're terrified for her. of course you love her even while feeling like you hate her, at times. it's alright to let your emotions be illogical, to just weather the storm and let them pass through you. write it down, talk to your loved ones, maybe consider speaking to a therapist or hotline over it. it's perfectly normal to need that support and talking through your circumstances may be illuminating/lead to some personal revelations regarding how you want to approach this. ultimately, you're angry because you care. after a while i was like that too, with my sister. although i tried to let her know that i was more worried than frustrated during our conversations, sometimes i still couldn't help the internal rage. all because i wanted her to wake up to reality and for her to be okay - i didn't get her thought process at all, didn't get her version of the world. and i felt so fucking powerless because she just strayed so quickly from her path, despite what she was telling me, despite her being relatively fine mere months prior. despite us being best friends and on good terms. it's a headfuck, and you don't have to know what to do, you don't have to have anything figured out. just try to focus on what you need, today.

the hardest thing to accept is the fundamental truth of the situation, and that is that you can't fix this for her. can't love her out of it, can't enable her out of it, can't fight her out of it. all you can do is be there for her emotionally while still maintaining the appropriate boundaries necessary to preserve ur own mental wellbeing. it's completely okay if you need more time - i know you said you cant bear to reach out to her at the moment, which makes total sense. but since you sent this message and i can still see that you're beyond concerned and it's only getting worse, maybe you could consider calling her or sending her a text or meeting her for coffee when you're ready. just to let her know you haven't stopped thinking of her. and that you care about her so much, that when/if she's ready to get help you will be with her every step of the way. even if shes battling addiction for the rest of her life. if she screams at you, if she breaks down, if she ignores you for what you say - fine. but at least she'll know on some level that she is not alone, and at least you'll know you did what you could with what was in your control. also about her being under social services - is there any way you could get in touch with them, maybe explain that youre still worried about her and that you think she needs a higher level of care, maybe ask them if theres anything proactive you can do in collaboration with them to maximize the help shes getting? i dont know how it works where you are, that might be a no go, but i just thought i'd mention it. i'm sorry, i know it's a disappointing answer, but i really don't realistically think there's any other. there's only so much of this that is in your hands and so far it sounds like you've done and are doing everything possible to stay sane while looking out for her. i really really hope something clicks for her and that she starts to listen to you and her loved ones soon, that she begins to approach recovery out of the genuine need to get better. but it really does have to come from within her, all you can do is encourage it. im sending you both so much love. i know more than anyone how fucking stressful it is to have to wake up to this every day, and i'm so sorry. if you need someone to talk to, my inbox will always be open. you deserve peace in your own life, too. take care x

resource one

resource two

resource three

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Origins (Chapter 4)

Summary: Before the Renegades put an end to the Age of Anarchy, they were six kids trying to survive day by day in a city ruled by chaos and desolation. Is there a space for hope and kindness somewhere in Gatlon City? Maybe.

AO3 link: https://archiveofourown.org/works/25123756/chapters/62248708

Translating it’s so exhausting. Especially when you have that bitch (Grammarly) constantly telling you “oh ur wrong” and you ask “where?” and the bitch responds “oh im not gonna tell you u r not premium”. So fuck it. Here it is. This was supposed to be Evander’s chapter, but I decided give this one to Tamaya instead, just for the fun. He can wait, he’s fine.

As you can see, I started to title my chapters. I already did it on AO3, but not on tumblr. The other three posts have their titles too. If you guess what song are the titles from, you get a cookie (?

I want to start doing a tag list but I don’t know who to tag. So if you want in, just tell me. I’m too shy to tag you if you don’t tell me to do it because I feel like I’m bothering you.

Also, trigger warning for domestic violence. I tried to keep it as low as possible and it’s a small scene, but I understand if there are people who still can’t handle it, and I’m no one to judge. I will take TW more seriously from now on. If you think I should tag any other of my work, feel free to DM me or send me an ask, even if it’s anonymus. Seriously, feel free to correct me. I’m a big girl, I can handle it;)

Running away from the world that we designed

Age of Anarchy

Year 8

Tamaya had gone three weeks without human contact. Her parents did not talk to her and she did not talk to her parents. Her mother sent the only remaining servant to bring her food twice a day. Every time he entered the room, Tamaya turned around to avoid making eye contact, because if she did, she would start crying. No one else was going to see her cry ever again.

It all started when Tamaya was flying in her room when her father came in without knocking first. The man was paralyzed and gaped, at the same time that Tamaya lost her concentration and plummeted onto her bed.

Then, her father started yelling at her. Marcus Rae had never been known to be particularly friendly in the way he spoke to other people. She had never heard that man say "thank you" or "please." However, Tamaya had not seen him scream either. At least, not at her. And that was enough to make her cry.

Not only because she was scared, but also because she felt dumb. She had managed to hide her abilities for five years and she had been caught in such a stupid way. Tamaya believed she was smarter, but she was not.

Her father took her by the arm and lifted her from the bed with such abruptness that Tamaya accidentally knocked over a porcelain figure that was resting on her nightstand. His shouting was already so unbearable that she could only make out a few words.

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

Her mother ran into the room and asked what was going on.

“Your daughter can fly!" yelled Marcus. "How the fuck did she learn to do it!?”

And so it went on. Her father kept shaking her like she was a rag doll, while the woman begged her husband to calm down, with a trembling voice full of terror.

But he wouldn't stop. Nothing made him stop.

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

“Please control yourself!” her mother cried.

In response, her father slapped her on the floor.

"ANSWER MY QUESTION, MELISSA!”

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

Melissa lay there, sobbing and holding her cheek. Seeing that his wife was not going to answer him in any way, his father refocused his attention on her. He turned her around and held her tightly by the arms. Then he forced her to walk to the wall and stamped her face against it. With one hand she crushed the back of Tamaya's neck and with the other, he scratched his chin.

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

Before she could react, her father tugged on one of her wings, as if he was going to pluck it apart. Tamaya screamed and broke down in tears again.

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

Did he hate her that much? Was Tamaya that disgusting to him?

Freak. Bounder. Idiot.

How could someone do that to their daughter? How ruthless do you have to be?

Was she a monster? Was his father a monster?

Were the two of them monsters?

An electric current ran through her body. Adrenaline seized her veins, giving her the strength to push her father away from her and scream:

“Enough!”

With a wave of her hand, Tamaya fired a bolt of lightning at one of her bookshelves, setting it fire. Her mother reacted and ran to the kitchen for a bucket of water to put the fire out. Her father was not even able to move, nor did Tamaya. She was not concerned about the accident she had caused. Her gaze was fixed on Marcus, and her contempt for him was stronger than any pain and fear she had left.

She wiped one last tear that ran down her cheek.

She may be a freak and she may be a bounder. But she made a promise to herself that she would never be an idiot again.

Melissa quickly put out the fire. They were very lucky that it did not spread to the rest of the room. After the initial impact, her parents stared at her as if they didn't know her. Their eyes seemed to say: “How is it that such a dangerous and violent creature our daughter?”

It is because you are creatures as dangerous and violent as me.

Now it was Saturday night. Tamaya was sitting on the carpet, surrounded by her dolls. When Georgia asked why she didn't get rid of them, she always blamed her mother, saying she would be very upset if Tamaya threw away such expensive toys.

However, Tamaya did not throw them away because, unlike Georgia, she did keep playing with her dolls. She had conversations with them, brushed their hair, and if her mother managed to get yarn, she would embroider their skirts with details of flowers or birds. In winter, she had even gone as far as to make sweaters for them.

It was a childish hobby for a seventeen-year-old girl, but it was also the only thing that kept her sane.

Knock. Knock.

Tamaya looked up at the light catcher. She flew to see who it was.

Georgia.

“What are you doing here?” she asked through clenched teeth.

“Surprise!”

“Lower your voice,” she scolded her. “My parents could hear you.”

Georgia put a fake padlock over her mouth and made a pleading gesture as she pointed to the latch on the catch. Tamaya rolled her eyes and let her in.

“My mom doesn't know I'm here, but she told me everything,” Georgia explained sitting on the bed. “Which wing was it?”

“This one,” she replied pointing to her right wing, “but it's nothing. It practically healed itself.”

Georgia looked at the circle of dolls on the carpet, stifling a giggle.

“What party are you having?” she asked teasingly.

Tamaya was silent. Georgia realized that her friend was in no mood for jokes and looked down, with a serious expression on her face.

“My mom also told me about your other power,” Georgia whispered.

The blood went to her feet.

“What power?”

“The lighting thing.”

Then, silence. That reunion was nothing like Tamaya expected. She believed Georgia was going to have hundreds of questions and was not going to stop talking. Georgia always had a lot of things to say to her. Most of the time, she did not talk about important issues. It was always about discussions with her mother, gossips going around her school, or about a new book that she had found and that she recommended.

Tamaya was glad Georgia knew how to start conversations. She had no idea.

How her mother had been able to talk about Tamaya's powers with Mrs. Rawle was a mystery to her. Melissa Rae was very concerned with what other people would think of her, something that had never made sense to Tamaya. Was there someone left in that damn city who kept worrying about something as stupid as status?

“Is it true that you almost hit your dad with one? With lighting?”

Tamaya did not want to lie to Georgia. Lying was not her thing. However, she wasn't quite sure about what to tell her exactly. Should it be something like “Yes, I did it, so what?” or something less violent? Something between the lines of: “Yes ... and I regret it.”

The thing was, Tamaya had no regrets. She had a lot of time to think about it those past few days and she could never force herself to feel a single shred of regret for her actions. Not even when her mom begged her to apologize to her dad. She just couldn't.

However, it was not until that moment that she realized she wasn't proud of it either. If it had been for her, Georgia would never have known about that little detail of the fight and her powers.

Tamaya already knew that she could control lightning and storms. She had discovered it relatively recently when she was flying and accidentally shot lightning at the ground. It was small and just left a black stain on the fine wood flooring, nothing a rug couldn't hide.

But lighting should not be near people, and Tamaya knew it.

“Why didn't you tell me?”

Tamaya turned to see her. “Pardon me?”

Georgia was frowning and arms crossed. There was reproach in each of the words that came out of her mouth.

“Why didn't you tell me you had more powers?” she asked. “Why didn't you trust me? I thought we were friends.”

“Woah, wait, Georgia,” she interrupted her. “How exactly is this about you?”

“Friends are supposed to talk to each other,” Georgia said. “I always tell you everything that happens to me and you know every last detail about my life. Why don't you tell me what's wrong with you? How many other things do you hide from me? Is our friendship based on lies? Is your name even Tamaya?”

Tamaya was so shocked by Georgia's reaction, she thought she was hallucinating. She noticed each gesture her friend's face made and each movement of her eyes. And she wasn't kidding. Tamaya was not hallucinating. Georgia was seriously mad at her.

“Really?” she asked her. “After everything that's happened to me, somehow I'm the bad guy to you?”

“Yes.”

The audacity of this bitch.

“How the hell can you be so self-centered, Georgia?” she asked with flushed cheeks. “Do you think this is because I didn't trust you? Did you ever stop to think about how I felt? Doesn't it occur to you that the reason I hid it from you is that I wanted to protect you?”

“Protect me?” Georgia laughed. “Don't be ridiculous, what would you be protecting me from?”

“From myself!”

And Georgia laughed again.

“I was protecting you from myself!” Tamaya insisted. “Stop laughing!”

But she ignored her. Georgia kept on laughing as if it was the funniest joke she had ever heard. It was clear as day that Georgia didn’t care anymore if the whole neighborhood heard her. She didn’t care if they got into trouble.

And she does not care about you, Tamaya.

Tears welled up in her eyes.

No, no one else was going to see her cry ever again. Not even Georgia.

Without thinking, Tamaya lunged for her friend. She grabbed the collar of her blouse, lifted her ten feet above the ground, and stamped her against the wall. She could feel the electricity on her fingertips, and she was sure Georgia felt it too.

She was no longer laughing.

“Look me in the eyes, Georgia,” she whispered. “Look me in the eyes!”

“I'm doing it,” she replied quietly.

“What do you see?”

“That you have beautiful eyes.”

Tamaya held her tighter. “Aren't you afraid of me? Aren't you afraid of monsters?”

Tears began to flow from Georgia's dark eyes. She put a hand to her mouth and a faint smile of pity appeared on her lips.

“Oh, Tamaya. You are not a monster.”

She had no qualms with people seeing her cry. How pathetic.

She released her.

“Yes I am,” she hissed.

Georgia fell to her feet.

“No, people have convinced you that you are,” she exclaimed, approaching her. “That's what they always say about all of us.”

She reached out to take her hand. Tamaya rose a few inches to not be within her reach. Georgia did not insist.

“And the worst thing is that,” she continued saying, “there are some people who believe them and become monsters. You know, like a certain person who starts with Ace and ends with Anarchy.”

Oh. Him.

“You know, I think he hates himself. A person who loves themselves would never do the things he does.”

“I don't blame him.”

Georgia pursed her lips. “Why not?”

“If you spend your entire life calling someone a monster, what do you expect them to become?”

Silence appeared again. For a second, Tamaya was pleased with herself for making Georgia run out of arguments.

But Georgia was never run out of arguments.

“That still doesn't excuse it,” Georgia replied. “You are constantly calling yourself a monster inside your head, and you had not become one.”

Tamaya looked at the mirror. Her reflection looked back at her.

“Would you still be my friend if I were a monster?”

“Uh, I don't know,” Georgia shrugged. “But I don't have to worry about it. You will never become a monster.”

“How are you so sure?” she asked defiantly.

“Because you are too strong to become one.”

She wished she could believe her.

No, Tamaya wasn't strong. That room was driving her crazy. She heard no other voice than her own, telling her the most horrible things she could hear every day. The world had never called her a monster because Tamaya's world were those four walls. Those four walls too similar to—

Oh, God.

Too similar to a monster's cage.

“I have to go,” Tamaya blurted out.

“Go?” Georgia asked in dismay. “But where?"

“I don’t know, but I have to go. Right now.”

Georgia asked no questions when she was helping Tamaya find a backpack, or when she packed Molly away before she began to look for clothes. She didn't even ask questions when Tamaya didn't dare go through the skylight, because she thought she heard her parents asking her not to leave.

However, when she turned around, she realized that no one was there.

She came out.

The air in the outside world smelled like gasoline and rain. The higher she flew, the smaller her house looked. Her neighborhood was the only point of light in that dull city. The buildings looked abandoned and lonely even from that distance.

It was horrible. But it was the world. A new world.

Tamaya allowed herself to laugh. She was so happy that she even dared to flip in the air.

Then, she realized that Georgia was not flying next to her. She was standing on the ceiling of her room, looking at her with teary eyes.

A crazy idea came to her mind.

“You come?” she asked her.

Georgia shook her head. She reached into her pants pockets and pulled out a torn locket. Tamaya reached out to look at it better. It had a missing part, was slightly rusty, and was not made of real gold, but the chain and clasp were intact.

“I found it in the market,” she told her, “with a lady who sold fish.”

“Why would a fisherwoman be selling lockets?” Tamaya asked raising an eyebrow.

“I do not know. It was from her husband, according to her,” Georgia explained. “But now it’s yours."

Tamaya had not worn any jewelry for a long time.

“It looks tragic,” she said.

“It combines with the city,” Georgia replied. Tamaya put on the locket. “Would you forgive me?” she asked. “I was selfish and I shouldn't have blamed you for not telling me. You had your reasons for keeping the secret. I understand if you don't want to talk to me—”

“Stop,” Tamaya ordered. “I'll come looking for you in a couple of days,” she assured her. “If you haven't heard from me by then, I'm dead.”

Her friend shuddered. She didn't know if from the cold or the fear.

“Any advice for the outside world?”

Georgia approached her with a smile and held her hand. “When in doubt, fly.”

Tamaya looked towards the horizon. The doubts did not take long to arise.

“Fine.”

Then, Tamaya flew. And she didn't look back.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rambling about my new watchholder oc Mallory

* absolute gremlin child. Eats dirt. Probably more of a monster than most of the yokai.

* at the same time tho, she is like super sunshine friend! She looks kinda gloomy ominous but her personality is actually super bubbly and her biggest priority in life is making new yokai friends and loving them forever. Like, creepy in a wholesome way? She does indeed love horror movies and creepy crawlies and could probably fistfight god, but that doesnt mean she's evil!

* kinda always bored but also easily exciteable? One of her biggest recurring jokes is just ignoring the normal or sane solution to a thing and doing something more fun even if its more difficult or dangerous. Actually i guess its more "fearless" than bored? Or bored of fear, lol. Fearless and doesnt really give a shit about any rules. But again not in a mean way, she doesnt break rules because she wants to piss people off, just like "im not gonna believe this if nobody bothers explaining why its supposed to be so important". But not exactly phrased like that cos that would be rude, lol. So uhh more like just relateable autism feel of not grasping social cues but mixed with a personality thats quite outgoing and uncaring of being judged poorly for not being normal, as opposed to me who's always worried about what people think.

* oh wait thats the word for it!! Free-spirited! Trickster! Like a peter pan type of trickster tho, more than loki. Like just "i am naturally outside the obligations of normalcy" rather than "i am intentionally trying to prank/illusion/manipulate people cos its funny". Or uhh i guess "manic pixie dream girl" but without all the stupid shit that trope has got associated with.

* pretty much just wish fullfillment of "what if i was confident enough to not care what people think and just act like myself no matter what"

* anyway in summary she likes to climb trees n stuff and her reaction to yokai being real is "yay" and her reaction to seeing an undefeatable giant kaiju is to run at it and try and suplex it with her bare hands. She's kind of a badass! Tho lol also her biggest character flaw is her badassness, cos she can be reckless due to the lack of fear. But then also sometimes when everyone is hopeless she really does manage to save the day no matter what, and help inspire everyone else to be brave too!

* though i'm thinking of maybe a character arc where she starts off seeing this as just a fun adventure with no stakes, and it doesnt matter if you take risks cos nobody's gonna get hurt anyway. Like a "this isnt really real, its just my hero's story" sort of thing? When things start getting more dark and she faces things she cant just defeat with simple optimism, it kinda stops being fun anymore. And she has to realize that even if she doesnt care about her own self preservation there's consequences that could happen to her friends and family. And maybe she's already made mistakes that she can't take back, and now she's neck deep in a conflict thats a lot bigger and more insurmountable than she thought. You can't just fistfight something like the abstract concept of hatred for humanity which will continue to be perpetuated as long as the idea keeps taking root. And maybe even yokai you befriended could start to believe it too, after all you've kinda been treating them as just fun toys and sidekicks on a story that's all about you, and dragging them into danger with your recklessness. Even though you're fighting the villains, are you really doing it because you actually care about saving the day? Do you even know what you're saving it from...?

* and similar to her unflappable victoryness being shaken, i think her fearlessness and confidence could also be deeper than they look on the surface. I feel like maybe as the story goes on it could be revealed that its less being fearless and more just not caring about her own safety. You start to see her get more actual consequences from her fights, and it starts to become sort of concerning that she keeps brushing it off as no big deal. Laughing it off. Wondering why her friends are even sad that she got hurt. And maybe she isnt really happy all the time and 100% secure in who she is, she just tries to hide any signs of doubt because she feels like nobody would care. And that she has to always be the funny class clown or else nobody would want to be her friend. And like.. She doesnt even really believe that she's great, believe that she's fine as she is. She's more aware of her weirdness than she lets on. She's constantly, paralyzingly aware that everyone thinks she's a freak. She did use to try and change herself to fit in, but she kept failing at it and it never helped her get any friends. Or when she did think she made a friend they'd turn on her whenever she slipped up and showed a crack in her mask of the perfect normal person. The perfect normal person they wanted her to be.. Constantly changing into WHATEVER anyone wanted her to be. The only reason she doesnt do that anymore is that she lost all hope in it working, not that she actually gained confidence in her true self. And even when she's npt conciously doing it she's still subconciously trying to be what people want her to be. She has to always be funny, always be fearless, she has to cling to the few parts of her weirdness that people dont seem to hate. And now she has to be the hero. She has to carry all the dreams of everyone she's met along the way, while never letting them know when she's scared she wont be able to help make them come true. She's always just laughing it off and never being fully open with any of her friends, because she's scared they'll hate her. ..

* so uhh.. Yeah. Personal experience of that. Personal experience of trying to fit into negative stereotypes of autism because thats what everyone saw me as no matter how hard i tried, and also it was the only form of autism theyd treat positively, somehow. Like just be the "funny one" and dont challenge any of their assumptions ans they'll leave you in relative peace. Put up with some degree of degredation to avoid the even worse version. And i was doing all of this at a very youbg age before i even knew i was autistic or what autism was, but i could still feel how people treated me differently and how i had to friggin agree with it or else they'd never let it go. Gahhh.. It was all way too complicated and dark for a kid to understand!

* so yeah anyway her story arc is going from being a badass funny to being a funny badass? Like she just becomes more genuinely tough and cool when she's not always winning and the stakes dont seem so low and comical AND most importantly you know her real feelings and see that she will indeed continue fighting even when she's scared. And she doesnt try so hard to be cool all the time so it just lets her be more genuine. And form actual relationships with everyone with genuine feelings. So its less "she is badass because its funny" and more "she is a badass because she's a badass". But she's still funny, just in more varied ways than simply "the only reason she won this fight so fast is because jokes". Fighting legit threatening enemies in fights that arent over in five seconds. So they can contain... SEVERAL joke..!!! And also some actual fighting for once!!

* hhh i dunno i am very tired im probably not explaining this well

* oh and i think possibly she has a bit of a complex of feeling she's nothing without her yokai watch? Like the yokai are her first friends who never abandoned her. And she always felt like she was useless and it was her own fault that she didnt have any friends. She first started off being all irreverent and goofy when she got the yokai watch cos she was well into her "i dont care anymore" phase of depression and felt certain these new friends would all realise she was awful eventually and leave, so like.. Why get attatched? Just have fun while it lasts. So maybe actually she shows early signs of her depression by trying harder to be normal whenever anyone shows her friendship. Maybe something where she starts straigjtening her hair or dressing more feminine and then you just see this look on her face like her heart has shattered when someone agrees that she does look better now. (Maybe a new yokai she recently caught who was like super cool and she wanted to impress them?) And she gets compulsively obsessed with it, exaggerating it to a ridiculous degree and starting to change other parts of her appearance and everyone goes from giggling about this weird circumstance to getting REALLY DAMN CONCERNED! And in the end something something the yokai who was an asshole abput her needing to be more feminine slips up and shows his true assy colours to the other yokai and theyre like IT WAS YOU and he's like "what? You should be thanking me for fixing your shitty trainer!" And Then Everyone Beats Him Up Forever. Etc etc moral that real friends accept you for who you are and anyone who tells you you have to change to impress them is not worth impressing. Also maybe some aspect where the yokai dude thinks that mallory is trying to impress him cos she has a crush on him, and thats the moment that manages to snap her out of her depressive funk. Self hate overrided by sheer EWW NO IM A LESBIAN, DUDE i just liked ur cool hat, geez. (Wait was that entire plot idea just an excuse to find a way to foreshadow her getting a crush on hailey in yw3...?)

* and maybe i dunno some sort of dramatic episode where she loses the ability to use the yokai watch and is faced with her self worth issues all at once and its super fuckin sad and we all know eventually she will get to see all her yokai friends again cos the plots not gonna end before finishing all the games but still MEGA SUPER SAD MOMENT ANYWAY (also tearful reunions!)

* also i just heard theres a yokai called furgus thats a big adorable hairball that gives people big hair. So maybe that could be one of the comically easy victory episodes? He uses his power on mallory but her hair is already too fluffy to be floofed! Maybe it backfires and turns his own hair into a boring bowl cut, lol? And then maybe a sequel where he returns for revenge a million episodes later but it just so happens to be during the maddiman boss fight and he accidentally cures his balding. "Noooo dont thank me nooooo" *is forced against his will to become a popular advertosing mascot for hair cream* *like straight up just gets sucked into the nearest bottle and sealed like a genie* *cursed forever to fame and fortune and a million dollar salary*

* lol i dont think im as funny as the actual yokai watch writers but i have a few ideas at least. This will be fun to draw!

1 note

·

View note

Text

5.6

The truck bounced and ambled its way down the dust-covered road, tossing its passengers gently from side to side like they were in a ship on a particularly stormy ocean. Cody’s stomach turned over, and he tore his gaze away from the window to look at John and Sailor, who shared the backseat with him.

“Are we sure about this?”

“No,” Sailor growled under her breath. She was hunched over in her seat, gently rubbing her leg where her knee joint met her new prosthetic. “It’s a bad plan. Not enough people, and not enough guns.”

“I thought that was kinda the point,” Nash said cheerfully, from the driver’s seat. “Y’all aren’t supposed to be attracting attention.”

“Nash, respectfully, you aren’t a part of this discussion unless you’re gonna be gettin’ out of the car to go with us,” Cody said, his voice flat.

He knew exactly what Nash’s orders were, unfortunately, and Nash wasn’t coming with him, John, and Sailor. According to what Marc had said that morning at brunch, Nash was coming along strictly as their getaway driver. If they didn’t come back to the rendezvous point within about an hour, Nash was allowed to head back to Texas Waters and leave the three of them high and dry. Cody, for one, had no doubt that he really would. Nash may have been affable enough, but at the end of the day, Marc was the one paying him for his services.

“Fair enough,” Nash said, with an easy shrug. “Your drop point’s comin’ up in a couple minutes, by the way.”

“Great,” Cody said through his teeth. John put a hand on his knee, gently, and he reached down to squeeze it. Having his own gesture returned muddled his thoughts about the whole interaction - he still wasn’t sure what he had been trying to communicate, back at breakfast. At least he could say for certain that John hadn’t minded. Cody refocused himself on the problem at hand, more agitated now than before. “I still don’t see why we have to split up.”

Their instructions were relatively straightforward, all things considered. Marc would be meeting with the heads of a local mob, in a town just across the Mexican border, under the pretense of making an alliance with them. Something about dividing up certain resources they each had access to for a mutual benefit. While the meeting was going on, John, Cody, and Sailor would be pulling off one of the double-crosses Marc was apparently notorious for - considering breakfast, that hadn’t been much of a surprise.

John, Cody, and Sailor were to steal the mob’s supply of water. The only catch was that the supply was kept in a compound located dead in the middle of a nest of muties. The mob didn’t have to spend the manpower guarding their most valuable resource if the muties kept people away for free, after all. All they had to do was guard one tunnel entrance. The mob members transported the water in barrels through a tunnel under the mesa, then raised it up on a lift. The barrels sat out in the open, the hundred-odd feral muties enough of a deterrent for any sane person.

The water heist, as Marc had devised it, was a two-pronged plan. Cody and Sailor would make their way up one side of the mesa, doing their best to go as quickly as possible while also disturbing as few muties as possible. At the same time, John would arrive at the guard station at the base of the mesa, dressed as one of the mob’s security men. While Cody and Sailor reached the compound from the top, John would take care of the guards patrolling the underground tunnel. If all went well, they’d meet as soon as Cody and Sailor took the lift down, then transport the barrels of water out through the tunnel to where Nash would be waiting in the truck.

It was a decent plan, in theory. But there were a lot of ways it could go wrong, and Cody hadn’t stopped thinking up more since they’d left Texas Waters. He was so nervous that he could practically feel the food he’d eaten at brunch rolling around in his stomach, threatening to come back up.

“You really want to fight your way back through a nest of pissed-off muties? I mean, be my guest, but…” Nash trailed off, perhaps remembering that Cody had just told him not to talk anymore. He punctuated it with another shrug.

“He’s right,” John murmured, almost as if it pained him to do so.

Cody frowned. “The last time we split up -”

“Was different,” John said, squeezing his hand back. “Not on purpose.”

“Still!”

“Cody,” John said firmly, then looked surprised when Cody’s attention snapped completely to him. He swallowed, Adam’s apple bobbing conspicuously in his throat, looking a little like a deer caught in headlights.

“Well?” Cody asked.

“...I’ll handle it,” John said at last, a little gruff, diverting his gaze towards the floor. Cody’s frown deepened.

“I know, but -”

“John has the easy job,” Sailor broke in, looking more than a little exasperated with the route the conversation had gone down. “All he has to do is clear the getaway path for us, and stay there to make sure no other goons show up.”

“I dunno about easy. Once he starts takin’ them down, someone’s gonna notice,” Cody said.

“Not if he’s careful,” Sailor said. “He’ll have enough time to be, with us sneakin’ our way up the whole fuckin’ mesa. I didn’t exactly think he was gonna run in guns blazing, and just start shooting people left and right.”

John snorted.

“Hey, he might have to, if his cover gets blown,” Nash pointed out.

“That’s fine,” John said, and then fell silent again, looking contemplative.

Cody watched him, thinking that, strangely, this was the most he’d heard John speak since before they’d arrived at Texas Waters that morning. He wondered how John was feeling, but he wasn’t about to ask a thing like that in front of Sailor and Nash. They’d have time to talk about it later, hopefully.

“Alright, here we are,” Nash said, pulling the truck off to the shoulder of the road. There wasn’t much there - the mesa loomed over them a couple of yards away, but for the most part, it was just scenic desert. Nothing to suggest a nest of muties nearby. “Hop on out, you two, and don’t forget your guns.”

Cody gave John’s hand a final squeeze before letting go of it, and opening the door to let himself and Sailor out of the truck. He hopped down to the ground, adjusting his poncho, and circling to the back of the truck for the rifles Marc had given to them, just in case. Cody had never fired a fancy rifle like the ones Marc’s guards used before, but he’d fired a shotgun, and he reckoned they worked about the same. He had his pistol holstered to his hip again, too, as a last resort.

“Be safe,” he told John through the window, slinging the rifle’s strap over his shoulder. “Don’t do anything stupid.”

John nodded. Nash revved the truck’s engine once, then peeled away onto the road, with apparently little regard for the dust the tires kicked up onto Cody and Sailor. Cody watched the truck disappear into the distance, until he couldn’t see John’s face looking for him from the window anymore.

“Ready to kill some muties?” he asked, turning to Sailor.

“I’m hoping we won’t have to,” she grumbled. She started to head for the mesa, her eyes scanning the horizon line for something. “There should be a footpath close to here that goes up to the top. It was on Marc’s map.”

“Right,” Cody said, following just a couple steps behind. He’d thought the map of the area that Marc had brought out while explaining the plan had been largely for dramatic purposes, but now he felt a little silly for not taking the time to study it seriously.

“What’s with you and Marc, anyway?” he asked. It couldn’t hurt to make conversation until they actually reached mutie territory, and he was curious, anyway. “I thought you were trying to catch him for the bounty. He acted like you come around for brunch all the time.”

“It’s complicated,” Sailor said, bluntly.

“Is it?”

“No,” she answered, after a moment of contemplation. They’d reached the beginning of the footpath, and she started up it, only pausing for a moment to make sure Cody was following her closely. “Not really. He thinks I’m hunting him because I like him.”

“And he likes you, obviously,” Cody said, filling in the gaps.

“Obviously,” Sailor said. “What was your first clue?”

Cody laughed - and then froze, the sound dying in his throat as he abruptly became aware of something moving in his peripheral vision. Sailor snapped her head up to look, and he did the same, already knowing what he’d find. His stomach twisted. There was a group of muties, at least five of them crouched on a ledge not five yards away. Their eyes were milky white with cataracts, and they were hunched over, with necks and arms that looked too long for their bodies. Some of them were chittering softly, Cody thought, unless it was the sounds of nearby animals. But he doubted that, somehow.

“They can’t see,” he murmured, barely moving his lips. If the muties were blind, maybe sneaking past them would be easier than Marc had thought.

Sailor frowned. She stooped to pick up a rock from the ground, slowly and deliberately. Cody wondered what she was doing for only a moment before she wound up and threw it, sending it sailing over the group of muties’ heads and clattering across the ground on the ledge they were on.

The muties reacted in less than a second. So abruptly it was startling, they sprang into motion, turning to lunge on the spot where the rock had landed. They were making low, guttural noises in their throats that sounded like a human imitation of a dog’s growl. Cody thought it might have been the worst noise he’d ever heard in his life.

“They can sure hear, though,” Sailor said, under her breath.

Cody bit the inside of his cheek, and nodded. Somehow, he got the feeling that this was going to be much worse than the last time he and John had split up.

5.5 || 5.7

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was told reading Philosophical problems with blah blah blah would answer why making 500 genders would solve gender stereotypes

I am petty and affable so I read it

If you want my opinions and my mind slowly melting i am kindly putting this under a read more cuz its fucking long as shit

the TLDR is : this drivel doesnt mention the problems of gender stereotypes or neogenders at all its just some guy wanking on why women need to give up their spaces because he thinks their wrong and annoying ( Kathleen Stock especially)

I’d love to @ you lake-lady, but you blocked me for thought crimes and im to lazy to try to get around that ( if you actually read this before recommending it to me, you are very very strong and very very brainwashed)

the first 14 paragraphs are circle talk "GC feminists are wrong, i will prove their wrong, they think "this" it is wrong ill prove its wrong etc etc etc"

if you survive that that, They focus on Kathleen Stock in their words "Stock presents an articulate, relatively comprehensive, and moderate form of gender-critical feminism"

first:

If Margie’s self-diagnosis (“I’m a boy”) is questioned by the therapist, the therapist can be construed as . . . “converting” . . . a trans child to a “cis” one. If, on the other hand, Margie’s self-diagnosis is affirmed unquestioningly, the therapist is effectively failing to affirm Margie in a sexual orientation of lesbianism; something which also looks like conversion by omission. (Stock, 2018e)

-They spend 5 paragraphs explaining why Stocks hypothetical girl^ isnt converted to male heterosexualness by transitioning, and not affirming Marges Gender identity is Dangerous

They do not address Stocks ACTUAL concern that Gender Affirming Therapy without any kind of therapy and research on GNC and SSA children is conversion by omission because it doesnt take into account if these feelings stem from gender stereotypes and homophobia. Stocks is not concerned that you are converting this girl straight( sex is real she would be SSA either way) she is concerned your transitioning her without affirming her sexuality and giving her support in the knowledge that being a lesbian is okay and perfectly normal.-

Next:

concern about female-only spaces is about legal self-identification without any period of “living as a woman,” prior male socialisation in a way which exacerbates the tendency to violence against female bodies, and the fact that many self-identifying trans women . . . retain both male genitalia and a sexual orientation towards females. (stock)

If the evidence shows (as, in fact, it is already showing) that some males—whether genuinely “truly” trans or just pretending—turn out to pose a threat to females, and it’s really hard to tell in advance which ones will, can’t we then make a social norm and/or law to exclude all [natal] males from female-only spaces . . . ? (also stock)

-Quotes are separated by garbage but this whole section is what we have all seen before " why must trans woman suffer, just because cis men hurt woman" except its really long it acknowledges male violence rates but refuses to acknowledge we have already seen men (and identified transwoman) taking advantage to hurt woman. This whole chunk is just SOME woman must be sacrificed for Trans feelings-

They do put:

Finally, we know that some men who come into contact with children in their work will offend against them. Yet we do not exclude all men from working with children, even if using gender as a watershed would prevent those offenses. Why does the good of minimizing child sexual abuse not lead us inexorably to the conclusion that we must outlaw all male teachers and coaches? Because our practical reason recognizes complexity: We readily see that even the most highly desirable states of affairs (minimizing abuse of children) do not have simple, quasi-mechanistic implications for policy or decision-making, and that they do not justify the indiscriminate suppression of other goods (even less important ones, such as professional vocations).

-And id like to add with the rise in pedo crimes I am 100% down with separating men from children because i do not think any child should be endangered just to keep men in jobs.-

They also put this quote in:

there is clearly a difference between the experience of a child who is treated by others in way that are characteristic of boys and also feels like a boy, and a child who is treated by others in ways that are characteristic of boys whilst feeling that they are really a girl. (Finlayson et al., 2018)

-And are you sure? are you really sure? I feel like there might be differences between social conditioning, experience and feelings. A boy treated like a boy and a boy(who feels like a girl) treated like a boy are still experiencing being treated and raised like a boy?? one just has emotional differences (is it internalized homophobia, Gender non conformity, a developed fetish?? who knows but they still experienced boyhood)-

-Next section says we cant make single stall or any other kind of netrual or trans bathrooms because its to hard? and it hurts trans feels reminding them that they have birth sexes because thats hate speech???-

also this:

Our social world is arranged in a way that makes exclusion from the sex/gender they claim—on the basis of a lack of “authentic” belonging (Serano, 2007)—central to trans subordination. As with other forms of social subordination, trans exclusion has not only material dimensions (Blair & Hoskin, 2018; Hargie et al., 2017; Moolchaem et al., 2015; Movement Advancement Project and GLSEN, 2017; Rondón Garcia & Martin Romero, 2016; Serano, 2013; Stonewall, n.d.; Yona, 2015), but also discursive ones that work in accordance with the logic of so-called performatives. Performatives are utterances that do things with words: specifically, they accomplish something in the act of saying it (Austin, 1975). The classical example is marriage—in the act of declaring a couple married, a celebrant brings about a change in their normative status, provided the celebrant is the right person in the right circumstances. This presupposes a normative background (that is a set of laws, conventions, or other rules) governing all those matters: who qualifies as a legitimate celebrant, what the right circumstances are for the performative to do its work, what marriage status means in terms of spouses’ rights and obligations, etc.

-Celebrating a Marriage is celebrating a couples chosen form of representing their relationship publicly and adding each other to their legal family, how is that the same as letting men into woman's bathrooms because they have feelings??-

-Theres more babblery about subjugating trans people by not pretending biology is fake, and that saying they cant just taking womans rights and spaces is denying their reality and existence

we find out the author is a gay(cis) man so why does he have opinions on womans spaces and issues who fucking knows ( he really likes the word unintelligible)-

-Im tired, Ive taken several breaks just to stay clear headed( mildly sane) and now we are onto why Trans inclusive practices dont threaten the concept of female, male, lesbian and gay. Okay buddy ole pal bring it on-

Stock (2018b) has also argued that trans inclusion on the ground of self-identification/declaration threatens “a secure understanding” of concepts intimately related to “woman”—namely, “female” and “lesbian.” It is hard to see this threat as a real one. After all, conceptually, “trans maleness” and “trans femaleness” presuppose “cis maleness” and “cis femaleness” as their other—namely, the case of female and male for which no transition, no reaching across, is required: the case of femaleness and maleness already on this side of (= “cis”) their sex.

-At some point i expect to find out Stock implied his dick is tiny or something " gender crit feminists are wrong im gonna argue with just this one" In this section he manages to be long winded and say nothing have a taste:

Stock (2019b) argues, correctly, that “sex [i.e., maleness and femaleness] is not determined by any single, unitary set of essential criteria,” and that “there is no single set of features a person must have in order to count as male or female.” She goes on to state that: (a) “you do still need to possess some” female (biological) sex characteristics to count as female; (b) that this is “a real, material condition upon sex-category-membership”; and (c) that “medical professionals [assigning sex]. . . rely upon an established methodology, aimed at capturing pre-existing biological facts” (Stock 2019b). Stock presents (a), (b), and (c) as if they were true without qualification. In fact, they only describe how, for very legitimate reasons, sex is understood and assigned within the discourses of biology and medicine; but our everyday usages of “male” and “female” may well be more capacious. It does not follow, of course, that there is no connection at all between these discursive domains—biology and the everyday. Rather, something like the biological meaning of “male” and “female” refer to the central cases of “male” and “female” as those terms feature in everyday usages. But those usages, if trans-inclusive (as they should be), will also cover, legitimately and usefully, noncentral cases of those selfsame terms.

-Yes you need to be female to be female, it doesnt matter what you look like how much you weigh your hobbies or tastes you just need to be female. Observed Biology is observed not assigned we dont pop out blank slates until someone says "ya this ones a girl"-

There really is no good reason to fear that such trans-inclusive practices will imperil “maleness” and “femaleness” as concepts. It is the very fact that those concepts have and will retain central cases that puts to rest any such fear. What makes something like the biological meanings of “male” and “female” the central cases of everyday usages of those words is “[o]rdinary-life truth seeking, a certain level of which is essential for survival”; this “involves a swift instinctive testing of innumerable kinds of coherence against innumerable kinds of extra-linguistic data” (Murdoch, 1992). Reproduction is a key aspect of human experience: The existence of each of us and the perpetuation of the human species presuppose it. The extra-linguistic reality of the dioecious configuration of human bodies, which is functional to human reproduction, means both that the concept of “female” and “male” are here to stay, and that their central cases will remain well-understood, even after we give up on trans-exclusionary attitudes, practices, and policies. To put it another way: trans-inclusive linguistic usages, policies, and so on, cannot threaten the distinction between the concepts of “male” and “female,” which hinges on the nondisposability of the central cases of those concepts.

For similar reasons, it is difficult to agree with Stock that characterizing as “gay” trans men attracted to men, and as “lesbian” trans women attracted to women, “leaves us with no linguistic resources to talk about that form of sexual orientation that continues to arouse the distinctive kind of bigotry known as homophobia” (Stock, 2019d). After all, our linguistic conventions make cissexual womanhood and manhood the central or paradigmatic cases of “womanhood” and “manhood”; cissexual (though not necessarily gender-conforming) lesbianism and male homosexuality the central or paradigmatic cases of “lesbianism” and “male homosexuality,” and so on. This will not change. First because of the prevalence of cissexual women/men and cissexual lesbians/gay men, in terms of sheer numbers, relative to trans women/men and trans lesbians/gay men. Second, because of the ways in which the concepts of “man,” “woman,” “gay,” “lesbian,” “cis,” and “trans” sit together with the concepts of “male” and “female,” which reference an extra-linguistic reality, of which, as we have already seen, we cannot but take notice. Given these linguistic and empirical facts, a trans-inclusive use of the terms “lesbian” and “gay” does not carry the dangers Stock (2019d) worries about.

-I keep going back and checking the date this was published in 2020 clearly this man has neither been online except to stalk Stock, nor talked to a human who actually believes what he is arguing against. No one is mad at transwoman for liking woman or vise versa its the kind of woman and men they go after and EXPECT romance and validation from ( ie lesbians and gay men, ie threatening what lesbian and gay mean in "inclusive" climates) fucking knob.-

I dunno if this is translated or the writer isnt english but he keeps using subordination where "opression" would be used and umm. anyway onto "Overemphasizing Sex-Based Subordination"

first he explains the difference between paranoid and paranoid structuralism there is so much fucking bullshit then we get to some quotes! that are bullshit-

Even assuming that the socialization of trans girls mirrors that of cis boys, the fact that trans girls do not identify with maleness can be expected to make a difference to the outcomes of such socialization (Finlayson et al., 2018).

-this guys back, love this guy doesnt know you dont fucking socialize yourself-

It is a mistake to treat “violence and discrimination against trans women . . . as if it were unconnected to that faced by cis women” (Finlayson et al., 2018).

-Finlayson marry me your so smart, that big brain of yours is sooo sexy. Anyway transwoman and "cis" woman face violence from the same people.. Men. but it is not for the same reasons and most transwoman who face violence are brown and black sex workers( if your gonna care go wholesys not halfseys). As opposed to woman who face violence no matter their class, race, nationality, age.. etc etc etc-

Saying “Not giving people everything they desire is not a denial of their humanity” (Allen et al., 2019) amounts to an insensitive dismissal of the serious argument that trans exclusion is ipso facto harmful.

-I want an affordable home and access to food and water whenever i am hungry, you want me to pretend reality doesnt exist so your feefees dont get hurt-

The claim that women “are a culturally subordinated group . . . [while] at best, trans women are a distinct subordinated group; at worst . . . members of the dominant group” entirely discounts the ways in which sex, gender, and cis/trans status intersect. These intersections produce more complex, shifting, and context-dependent power relationships than are captured by the M > F formula.

-Sex based oppression is actually like jello, sometimes woman are less oppressed or oppressed slightly more to the left, I too can just kinda say words-

A dubious assumption underlies this statement: “[T]he fact that our concept-application [of, e.g., ‘woman’] might indirectly convey disadvantage towards some social groups [e.g., trans women] is not itself a reason to criticise the concept use, because the concept use has a further valuable point” (such as “to pick out a distinctive group, relative to recognisably important interests”) (Stock, 2019e). The dubious assumption here is that the “valuable point” of a restrictive use of the concept will be lost if the concept is broadened. The assumption is dubious because even in its broad, inclusive use, the concept retains a readily identifiable central case.

-Yes you dunder head if we start calling lizards mammals we lose the point of what makes a mammal a mammal, which complicates and endangers our way of researching and understanding mammals

by making woman "whoever the fucks wants to be one" we loss the ability to easily talk about things that are exclusive to woman the more female language is edified the harder it is for females to unite to talk about womans issues, womans health, girls puberty, womans oppression etc etc.-

-my fuck i dont even care to learn this mans name and i have a personal hatred just for him, i hope ya'll have noticed he uses several different "sources" for his arguments and yet pins GC feminism on Stock alone. Anyway here we go into Doing Philosophy and Debating Policy in the Age of Social Media and Digital Platforms ( i think this man nuts every time he types out philosophy)-

my god we have brough Plato into this, Stocks must stand alone but we are at fucking plato, anyway this section actually has some brains in it there drivel but also truth:

Needless to say, in real-world face-to-face exchanges, unalloyed communicative action is known only by approximation. But there are very good reasons to think that the distance between the ideal (namely, communicative action) and the real is especially wide in the context of the quasi-spoken digital media used to construct (and respond to) the gender-critical case against trans inclusion. Stock (2019f) herself, discussing the reception of her arguments, has complained about countless “half-arsed takedown attempts” by “online philosophers,” crediting, conversely, philosophers she meets offline with “interesting, constructive, and charitable” objections. She also notes that social media siphons “users into paranoid, angry silos” (Stock, 2019d), and that “when reading disembodied words on a screen” it is “easy enough” to engage in “projection” (Stock, 2019a). Why and how do social media and allied platforms have this potential for distorting genuine communicative action?

First, they enable new manipulative communication practices, such as flaming and trolling. The popular support base of gender-critical academics makes ample use of these, though gender-critical scholars are also at the receiving end. Rather than using the quasi-spoken features of social media and allied platforms with a view to genuinely advancing understanding, online activists may exploit these features for strategic aims. Common techniques include drowning a post or blog with irrelevant comments; exposing the blogger to ridicule; deflecting attention from the point she made; forcing her to address spurious objections; pretextually professing a failure to understand, demanding endless further explanations; and so on. Some of these techniques are available in spoken exchanges, but social media and allied platforms magnify their power by enabling “widely-distributed individuals to organize and galvanize around issues of common interest [or] political advocacy” (Stewart, 2016); and by facilitating the use of nonverbal or nonargument-based, but effective, communicative devices, such as memes, gifs, and emoticons.

Another way in which these digital media distort genuine communicative action is by affecting the motivations of the blogger, or micro-blogger, herself. Specifically, they facilitate the interference with genuinely communicative goals (reaching understanding) by noncommunicative, strategic aims. I will discuss three: acquiring influence, career progression, and venting.

In traditional academic communicative practice, one’s recognition as an expert is supposed to follow from the credit that accrues to one as a result of the soundness of one’s research methods and arguments, judged through peer-review processes. But “in the era of social media there are now many different ways that a scientist can build their public profile; the publication of high-quality scientific papers being just one” (Hall, 2014). Veletsianos and Kimmons (2016) have found, by examining a large data set of education scholars’ participation on Twitter, that

being widely followed on social media is impacted by many factors that may have little to do with the quality of scholarly work . . . and . . . that participation and popularity may be impacted by a number of additional factors unrelated to scholarly merit (e.g., wit, controversy, longevity; p. 6).

-This section like every section goes on forever but we finally finally reach our conclusion-

Cooper (2019) has invoked a legal pluralist perspective to argue that it is possible, and may be desirable, for gender as conceived by gender-critical feminists (as “sex-based domination”) and gender as conceived in trans-affirming terms (as “identity diversity”) to coexist side-by-side in the law. Access to women’s spaces is just the kind of policy matter that need not choose between one conception of gender and the other: it can and should be granted on the basis of both. While a compelling feminist case has been made for inclusion (Finlayson et al., 2018), the best feminist case against inclusion suffers from a number of argumentative fallacies (Aristotle, n.d.), and is at odds with well-established and sound uses of practical reason. Many problems in gender-critical thought are consistent with the explanation that paranoid structuralism is too often presupposed in gender-critical work, rather than being treated, productively, as a hypothesis. The nature of the publication outlets favored by gender-critical feminists (social media, blogs, etc.) is also likely to be implicated in generating some of these problems.

I think one of the things i would like anyone who managed to read this entire thing to take away from this

is that not ONCE were male bathrooms or male spaces mentioned, not once did this apparently "cis" gay man say that he welcomes and wants transmen in HIS spaces or that he has even thought about it

(((( also he didnt even mention neo genders so my original question 100% unanswered, even fuckface magee doesnt think demiboys are real. He doesnt want to or even mention solving sex based oppression he just wants woman to stop fighting to keep men out))))

#gender critical#gender critical feminism#GC#radfem#terf friendly#anyone with a strong brain try to read the original piece its contras brother i swear to fucking god#id say radfem friendly but he doesnt touch womans issues he doesnt care#trans exclusive

0 notes

Text

Bryan Caplan, The Economics of Szasz: Preferences, Constraints and Mental Illness, 18 Rationality & Society 333 (2006)

Abstract

Even confirmed economic imperialists typically acknowledge that economic theory does not apply to the seriously mentally ill. Building on psychiatrist Thomas Szasz’s philosophy of mind, this article argues that most mental illnesses are best modeled as extreme preferences, not constraining diseases. This perspective sheds light not only on relatively easy cases like personality disorders, but also on the more extreme cases of delusions and hallucinations. Contrary to Szasz’s critics, empirical advances in brain science and behavioral genetics are largely orthogonal to his position. While involuntary psychiatric treatment might still be rationalized as a way to correct intra-family externalities, it is misleading to think about it as a benefit for the patient.

Do we want two types of accounts about human behavior – one to explain the conduct of sane or mentally healthy persons, and another to explain the conduct of insane or mentally ill persons? I maintain that we do not need, and should not try, to account for normal behavior one way (motivationally), and for abnormal behavior another way (causally). Specifically, I suggest that the principle, ‘Actions speak louder than words,’ can be used to explain the conduct of mentally ill persons just as well as it can the behavior of mentally healthy persons. Thomas Szasz, Insanity: The Idea and Its Consequences (1997: 352)

1. Introduction

Even the staunchest proponents of economic imperialism have long made an exception for the seriously mentally ill. Posner (1998: 258) remarks that:

If a person is insane either in the sense that he does not know that what he is doing is criminal (he kills a man who he thinks is actually a rabbit) or that he cannot control himself (he hears voices that he believes are divine commanding him to kill people), he will not be deterred by the threat of criminal punishment.

Cooter and Ulen’s (1988: 237) Law and Economics text is more explicit:

If the promisor’s preferences are unstable or not well-ordered, then he is unable to conclude a perfect contract. The law says that such people’s promises are unenforceable because they are legally incompetent. For example, children and the insane do not have stable, well-ordered preferences, and, as a result, their promises are unenforceable.

Even Milton Friedman (1962: 33) concurs: ‘Paternalism is inescapable for those whom we designate as not responsible. The clearest case, perhaps, is that of madmen. We are willing neither to permit them freedom nor to shoot them.’

Though these authors are usually eager to bring social phenomena into the orbit of economics, they not only make an exception for severe mental illness; they treat the exception as uncontroversial. Over time, however, diagnoses of mental illness have become increasingly widespread.1 Epidemiologists now report that 20% or more of the USA population suffers from mental illness during a given year (Kessler et al. 1994). A seemingly small loophole in the applicability of economics has grown beyond recognition.

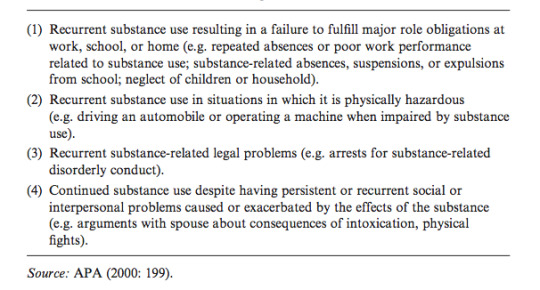

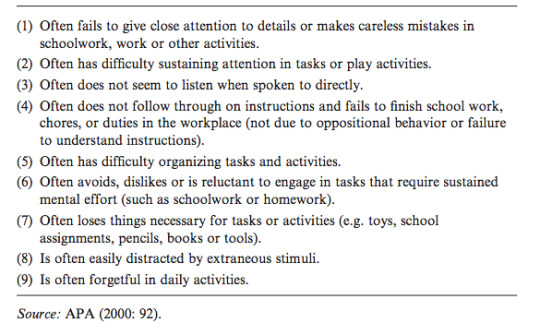

This article argues that much if not all of the loophole should never have been opened in the first place. Most glaringly, a large fraction of what is called mental illness is nothing other than unusual preferences – fully compatible with basic consumer theory. Alcoholism is the most transparent example: in economic terms, it amounts to an unusually strong preference for alcohol over other goods. But the same holds in numerous other cases. To take a more recent addition to the list of mental disorders, it is natural to conceptualize Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as an exception- ally high disutility of labor, combined with a strong taste for variety.2

Consider how economists would respond if anyone other than a mental health professional described a person’s preferences as ‘sick’ or ‘irrational’. Intransitivity aside, the stereotypical economist would quickly point out that these negative adjectives are thinly disguised normative judgments, not scientific or medical claims. Why should mental health professionals be exempt from economists’ standard critique?

This is essentially the question asked by psychiatry’s most vocal internal critic, Thomas Szasz. In his voluminous writings, Szasz has spent over 40 years arguing that mental illness is a ‘myth’ – not in the sense that abnormal behavior does not exist, but rather that ‘diagnosing’ it is an ethical judgment, not a medical one.3 In a characteristic passage, Szasz (1990: 115) writes that:

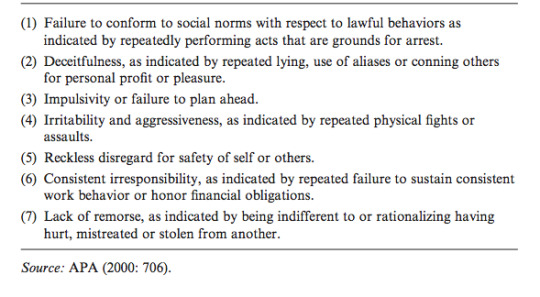

Psychiatric diagnoses are stigmatizing labels phrased to resemble medical diagnoses, applied to persons whose behavior annoys or offends others. Those who suffer from and complain of their own behavior are usually classified as ‘neurotic’; those whose behavior makes others suffer, and about whom others complain, are usually classified as ‘psychotic’.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) 1973 vote to take homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses is a microcosm of the overall field (Bayer 1981). The medical science of homosexuality had not changed; there were no new empirical tests that falsified the standard view. Instead, what changed was psychiatrists’ moral judgment of it – or at least their willingness to express negative moral judgments in the face of intensifying gay rights activism. Robert Spitzer, then head of the Nomenclature Committee of the American Psychiatric Association, was especially open about the priority of social acceptance over empirical science. When publicly asked whether he would consider removing fetishism and voyeurism from the psychiatric nomenclature, he responded, ‘I haven’t given much thought to [these problems] and perhaps that is because the voyeurs and the fetishists have not yet organized themselves and forced us to do that’ (Bayer 1981: 190). Even if the consensus view of homosexuality had remained constant, of course, the ‘disease’ label would have remained a covert moral judgment, not a value-free medical diagnosis.

Although Szasz does not use economic language to make his point, this article argues that most of his objections to official notions of mental illness fit comfortably inside the standard economic framework. Indeed, at several points he comes close to reinventing the wheel of consumer choice theory:

We may be dissatisfied with television for two quite different reasons: because the set does not work, or because we dislike the program we are receiving. Similarly, we may be dissatisfied with ourselves for two quite different reasons: because our body does not work (bodily illness), or because we dislike our conduct (mental illness). (Szasz 1990: 127)

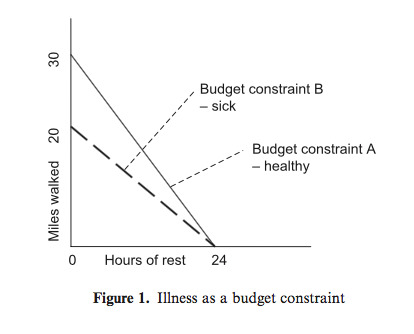

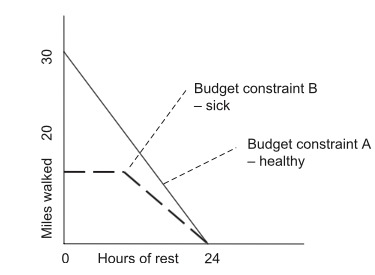

Explicitly wedding standard economic concepts to Szasz’s philosophy of mind allows us to spell out his position with new clarity and force. How so? Consumer choice theory has two basic building blocks: preferences and budget constraints. Inside of this framework, how would one model physical disease? By and large, as an inward shift of the budget constraint: When you have the flu, for example, your peak level of physical performance declines. In contrast, most mental diseases amount to nothing more than unusual preferences; they do not affect what a person can do, only what they want to do. An oft-repeated slogan states that ‘Mental disease is just like any other disease’, but elementary microeconomics highlights a disanalogy with a distinct Szaszian flavor. To call someone physically ill is (usually) a descriptive claim about what a person is able to do; to call someone mentally ill is (usually) a normative claim about what preferences he ought to change.

In addition to unusual preferences, the mentally ill are often said to suffer from delusional beliefs. This criterion has greater economic appeal than bald complaints about preferences: Since the rational expectations revolution, economists have routinely equated systematically biased beliefs with ‘irrationality’ (Caplan 2002; Sheffrin 1996; Thaler 1992). In practice, however, only unpopular delusions provoke diagnoses of mental illness. Adherence to the dogmas of an established religion or ideology – no matter how bizarre – almost never attracts psychiatric attention. Originating your own bizarre belief system frequently does.4 In Szasz’s (1990: 215) words:

If you believe you are Jesus or that the Communists are after you (and they are not) – then your belief is likely to be regarded as a symptom of schizophrenia. But if you believe that Jesus is the Son of God or that Communism is the only scientifically and morally correct form of government – then your belief is likely to be regarded as a reflection of who you are: Christian or Communist.

Once again, mental health specialists’ covert standard is not scientific or medical, but moral: Absurd beliefs shared by millions are ‘healthy’; equally absurd beliefs held by a lone individual are ‘sick’. While economists have only begun to study the demand for irrational beliefs (Akerlof 1989; Akerlof and Dickens 1982; Caplan 2001), there is little if any reason to treat ‘popular’ and ‘niche’ delusions asymmetrically.

I organize this article as follows. The next section summarizes the distinctive features of Szasz’s position and corrects popular misconceptions about it. Section 3 considers the best way to model disease in economic terms. Section 4 explains why at least a high fraction of mental illnesses must be formalized in the opposite way, as preferences. Section 5 analyzes the ‘hard cases’ of hallucinations and delusions. Section 6 argues that the progress of brain science and behavioral genetics sheds little light on deeper questions about the nature of mental illness. Section 7 concludes.

2. A Brief Survey of Szasz

Thomas Szasz is probably best known for his opposition to involuntary mental hospitalization. His (1990: 107) rejection is categorical and impassioned:

Involuntary mental hospitalization is like slavery. Refining the legal or psychiatric criteria for commitment is like prettifying the slave plantations. The problem is not how to improve or reform commitment, but how to abolish it.

Unfortunately, his policy advocacy overshadows the more novel aspect of Szasz’s thought: his philosophy of mind. For Szasz, the most salient fact about human motivation and thought is its vast heterogeneity. Even if we limit the sample to people with a ‘clean bill’ of psychiatric health, the range of desires and viewpoints is amazingly wide (Caplan 2003; Piedmont 1998). There are monks and prostitutes, mountain climbers and shut-ins, CEOs and beach bums, Sunni Muslims and Trotskyist splitters. Great works of literature are perhaps the most powerful evidence of human diversity: think of the chasms between Iago, Brutus or Falstaff in Shakespeare; Pierre, Rostov or Anna Karenina in Tolstoy; Javert, Frollo or Quasimodo in Hugo. Indeed, one of the lessons of literature is that characters’ superficially inexplicable behavior becomes intelligible once you see it from their perspective.

Now consider the common sense view of mental illness: ‘You would have to be crazy to do that!’ or, as Sylvia Nasar (1998: 18) describes schizophrenia, ‘More than any other symptom, the defining characteristic of the illness is the profound feeling of incomprehensibility and inaccessibility that sufferers provoke in other people. Psychiatrists describe the person’s sense of being separated by a ‘‘gulf which defies description’’ from individuals who seem ‘‘totally strange, puzzling, inconceivable, uncanny, and incapable of empathy, even to the point of being sinister and frightening’’.’ Szasz faults the common sense view for refusing to take human heterogeneity seriously. What makes you think that no human being would prefer a life of day-dreaming, play-acting, daily heroin use or sadism? Is this any less credible than other unusual preferences that now escape psychiatric stigma, such as being gay, entering a convent, or ‘speaking in tongues’ in a Protestant church? As Szasz (1997: 64) critically observes:

It is wonderfully revealing of the nature of psychiatry that whereas in natural science there is a premium on the expert observer’s ability to understand what he observes . . . in psychiatry there is a premium on the expert’s inability to understand what he observes (and to understand it less well than the object he observes, which is typically another person eager to proffer his own understanding of his own behavior).

Thus, psychiatrists’ inability to understand economist Donald McCloskey’s desire to become Deirdre led to two short but involuntary hospitalizations. But she (1999: xiv) maintains that she simply would rather be a woman than a man:

In response to your question Why? ‘Can’t I just be?’ You, dear reader, are. No one gets indignant if you have no answer to why you are an optimist or why you like peach ice cream. These days most people will grant you an exception from the why question if you are gay . . . I want the courtesy and the safety of a whyless treatment extended to gender crossings.