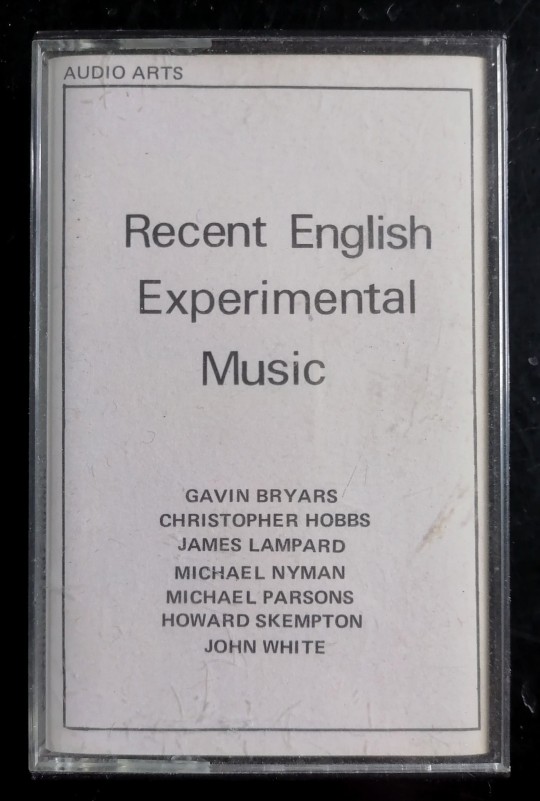

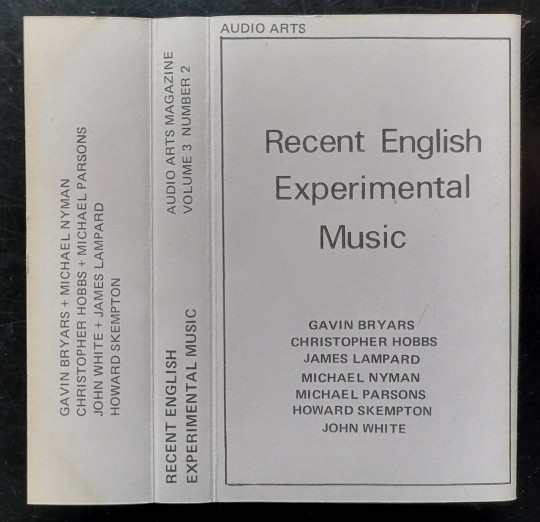

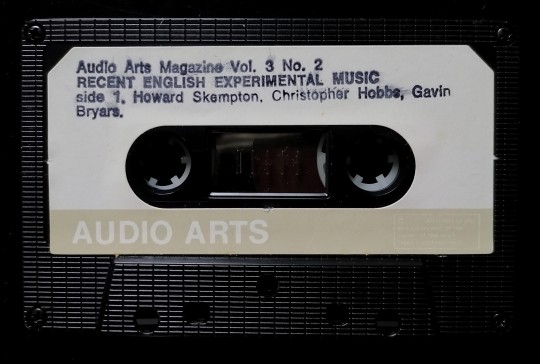

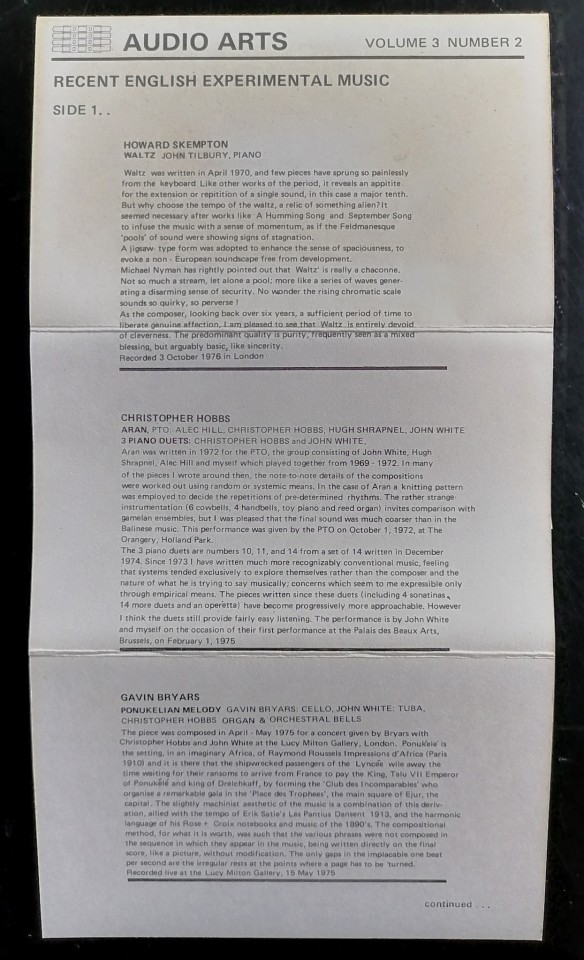

#howard skempton

Text

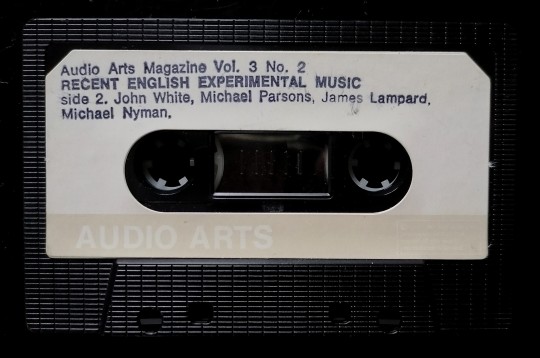

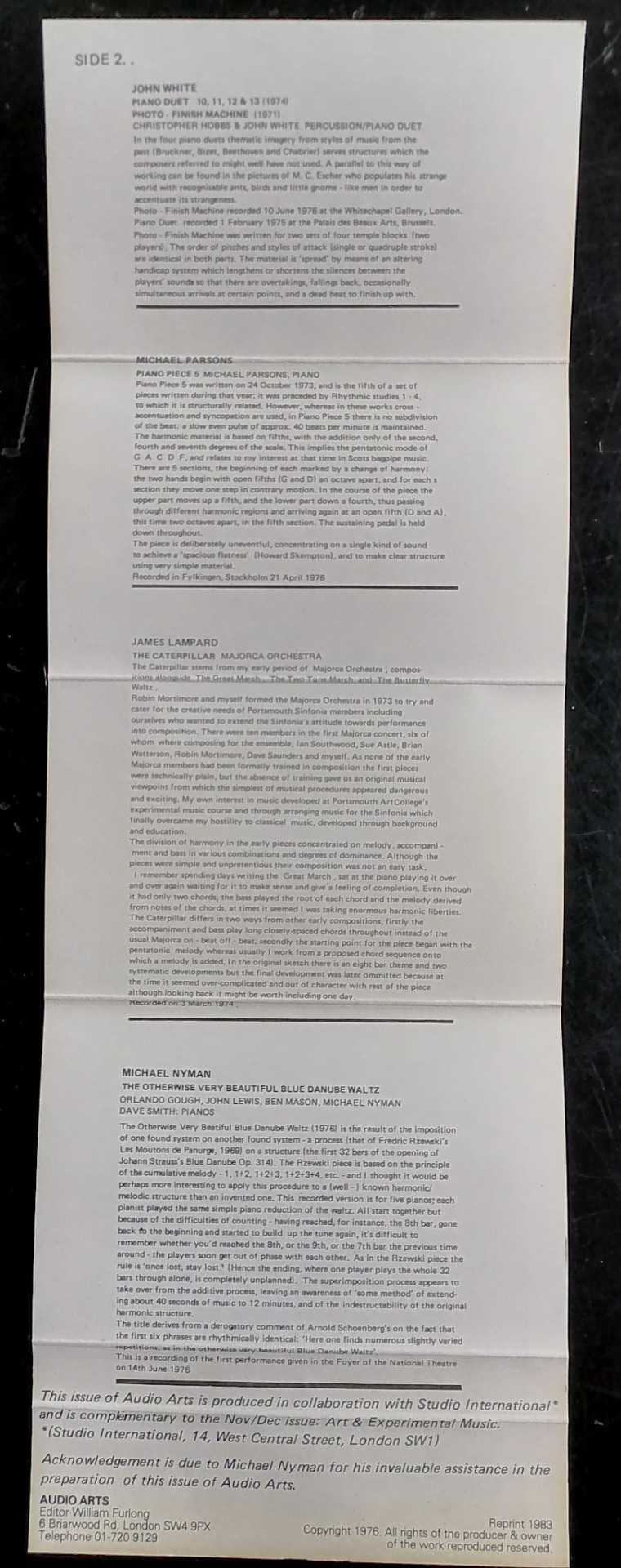

V/A

"Recent English experimental Music"

(cassette. Audio Arts. 1983 / rec. 1972-76) [GB]

youtube

#compilation#1976#uk#contemporary#avant garde#experimental#gavin bryars#christopher hobbs#james lampard#michael nyman#michael parsons#howard skempton#john white#john tilbury#majorca orchestra#cassette#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Elkington & Nathan Salsburg Interview: Poise, Levity, and Easygoingness

Photo Credit: James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg

BY JORDAN MAINZER

All Gist (Paradise of Bachelors), the third album of guitar duets from exploratory, thoughtful players James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg, sounds like what it is: two longtime friends and collaborators playing together, equal parts casual and focused. Since their 2015 album Ambsace, each has been busy, separately and together. Elkington's released three solo albums, played as part of Eleventh Dream Day, Brokeback, and Jeff Tweedy's live band, and recorded with Steve Gunn, Nap Eyes, and many more. Salsburg's dropped a bevy of albums and has played on records by Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Shirley Collins, and others. Meanwhile, the two have come together on four records by Salsburg's partner Joan Shelley, and Elkington produced Salsburg's Psalms, his 2021 album of arrangements of Hebrew psalms. Their duo records, however, are born of the most natural collaboration, each bringing to the table melodies they think--perhaps know--the other will respond to, combining them, and being open to feedback or changing gears entirely.

All Gist, specifically, carries the distinct quality of the Chicago winter during which it was recorded: You can picture Elkington and Salsburg sitting around the kitchen table, each culling from their vast repertoires and tendencies, creating something to warm their bodies and hearts and perk their heads and ears, unaware of any blusters outside. The songs are reflective of their shared artistic interests and inspirations, and they're rounded out by the presence of musical contemporaries with whom each has fostered relationships over the years. Opener "Death Wishes to Kill", which takes its title from T.F. Powys' Unclay, sports lilting guitar melodies that offer an affable sway, along with Wanees Zarour's violin solo. The minimal "Explanation Point" bounces along a groove that sounds bigger than it is, almost gestalt, as Jean Cook's strings and Anna Jacobson's brass shimmer. Moments of percussion come from other instruments like hand drums ("Long in the Tooth Again"), along with Wednesday Knudsen's woodwinds ("Nicest Distinction"), or as part of the sheer tactility of guitar scrapes and textures. The self-reflexive "Numb Limbs" gets its title from the physical aftereffects of playing a song that took forever to come together; you feel the spritely guitar picking and breakneck tempo in your own fingers.

Of course, All Gist has a few interpolations, namely a gentle, quiet, start-stopping version of Howard Skempton's "Well, Well, Cornelius" and a taut, concise combination of two traditional Breton dance tunes in "Rule Bretagne". Easily, the most unexpected song on the album is a version of Neneh Cherry's classic late 80s jam "Buffalo Stance". Oscillating and slowed down to an expanse, one guitarist plays Cherry's lyrical line, the other the song's instrumental melody, making something both recognizable and nostalgic as well as emblematic of the duo's adventurous nature. That combination, indeed, is the gist of Elkington and Salsburg.

Earlier this month, both guitarists answered some questions over email about All Gist, their creative process, covering songs, and their sometimes-overlapping, oft-diverging taste in art. Read their responses below, edited for clarity.

Photo Credit: Joan Shelley

Since I Left You: Why was it time again to make an album together?

James Elkington: We’d been talking about it since we made the last one, but the truth is that we’ve both just been too busy. I started making solo records again after the last one, plus I got to produce one for Nathan, and we both help out with Joan Shelley’s records, so it never felt like we weren’t working together anyway. We were just working on projects in a different way. I think that Nathan and I both think there’s something about the duo’s music that is different from the other things we do, so we were keen to get back to it at some point. Fortunately for us, we got an invitation to play at a guitar festival in Chicago, and we used that as an excuse to start working on new material. I should also mention that our wives kept bugging us to do it again.

SILY: How was your collaboration on All Gist unique as compared to your other records together, and how was it similar?

JE: We hadn’t played together like this for something like 7 years, so I was interested to see if we could even do it. But our writing together was as quick and easy as it ever was, and in that sense, it was really similar to how we worked before. Nathan has always worked with longer forms than me, but this time, I wanted to follow his lead a bit more in terms of writing longer pieces with less changes and more textures. We weren’t concerned this time with being able to play all of this stuff live, so we left more space for orchestration and overdubs.

Nathan Salsburg: We’ve each lived through a world of experiences in the past ten years, musical and otherwise. Now that we’re each squarely into our middle age, I think the poise, levity, and easygoingness that should be attendant on this period of life show up in the music at [the] pitch they didn’t in the past.

SILY: Was there a lot of improvisation in the process of combining the different instrumental motifs you each brought to the recording session?

JE: Because we don’t have a great deal of time to work together, we find things go much quicker if we come up with rough musical sketches by ourselves and then present them to the other. Nothing is ever written in stone, and the level of trust is very high. Anything Nathan suggests for one of my ideas is going to improve it. Both of us are more concerned with coming up with something that sounds cohesive and keeping the ball rolling than having any personal agenda for how this thing should be, and we always leave enough space for us to be surprised by what we end up with. I rarely have any idea what Nathan is playing, but I like how it sounds when it’s finished. We did experiment with recording something completely improvised and liked the results, but it sounded like a different record, so we didn’t use it. Maybe that’ll be the next one.

SILY: How or at what point in making each song do you determine whether it needs more musical accompaniment, from other instruments and/or players?

JE: That’s a good question, and I’m not sure I have an answer, but the plan seems to be to write a piece that can stand by itself for the two guitars, record that to our satisfaction (which is nearly always the first take we can manage that has all the right parts), then start throwing other instruments at it to see what sticks. Most of that approach is me in my studio adding things and then taking them off again. There are certain pieces where, as were writing them, we can hear that a solo instrument would sound great in a certain part. Wannees Zarour’s solo in "Death Wishes To Kill" was like that. There are songs, like "All Gist Could Be Yours", where for a repeating chord sequence to have the effect we’re going for, its going to need a lot of support from other instruments, and we talked about that as we were writing it.

Cover art by Chris Fallon

SILY: Do you have a backlog of other people's songs you think might be fun or fulfilling to cover or reimagine as a guitar duet? What makes a song fit for a cover from your two artistic voices?

JE: Well, I’m a little concerned that there’s a potential novelty aspect to our doing a lot of covers, but maybe it's okay. We certainly didn’t go out of our way to think of any for this record. Nathan suggested "Buffalo Stance" early on just because he loved the song and all the parts. I was resistant at first, just because I thought there wasn’t enough there for us to work with harmonically, but there’s so much good stuff going on with the synths and the bassline in that tune that it became more a process of picking and choosing what aspects of the song we wanted to shine a light on, at what time. Our Smiths cover from the last record is like that, too. It switches from the guitar line to the vocal depending on where we’re at or what seems to be most important, so I suppose we have a system for doing this. I think the only criteria we have for picking a song is whether one of us really really likes it and the other one can get their head around it.

SILY: "Death Wishes To Kill" takes its title from a T.F. Powys novel you both read. Do the two of you tend to recommend books, films, albums, etc. to each other a lot? Do you ever find you're about to recommend the same thing to one another?

JE: I was going to write that we don’t have a huge amount of overlap, but I’m remembering going to his house when we hadn’t known each other long and being confronted with what appeared to be a wall of my own books. Its not as if we like exactly the same things, but there are some writers and records that we both like that NO-ONE else I can think of likes, so when Nathan suggests a book, I usually get to it pretty quickly. I think Nathan was reading the Powys novel, Unclay, and sent me a screen shot of one of the passages in the book with the caption "this is for you" underneath. He also sent me a link to an Australian liquor store commercial from the early 90’s because he knew it would make me laugh for a day and a half, and it did.

NS: I remember we made common cause over Max Beerbohm not long after we met—Zuleika Dobson, maybe—but yeah, we each have some preoccupations that the other couldn’t give much of a shit about. Like, I can’t say mid-century British horror movies do a whole lot for me. I’m remembering when Jim spent the better part of an hour trying to explain the appeal of U.S. Maple, and I can’t say he succeeded. And Jim couldn’t care less about rural American string-bands of the late 1920s. But when we have an overlap—Unclay, say, or the totally under-appreciated Yorkshire singer-songwriter Jake Thackray, or Alan Partridge—and yes, these overlapping things do tend to all be English—it’s always stuff we’re super, super jazzed about.

SILY: Can you tell me about the cover art for All Gist?

NS: The artist’s name is Chris Fallon, an old friend of mine from when I lived in New York City 20+ years ago. He’s a phenomenal painter, and I love his figures, his palette, and the scenes/settings that he dreams up. I asked him to create a portrait of us, and this is what he did. He’s never met Jim and hasn’t seen me in quite a few years, but I feel like he nailed something of Jim’s and my dynamic, equal parts earnest, bizarre, silly.

youtube

#interviews#james elkington#nathan salsburg#paradise of bachelors#all gist#james elkington & nathan salsburg#james elkington and nathan salsburg#ambsace#eleventh dream day#brokeback#jeff tweedy#steve gunn#nap eyes#bonnie “prince” billy#shirley collins#joan shelley#psalms#t.f. powys#unclay#wanees zarour#jean cook#anna jacobson#wednesday knudsen#howard skempton#neneh cherry#chris fallon#the smiths#max beerbohm#zuleika dobson#u.s. maple

0 notes

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Howard Skempton, "Saltaire Melody"

0 notes

Audio

At Home #13 with Christian Wolff playlist:

Oliver Lake&Julius Hemphill

"Vator"

from Buster Bee

(Sackville Recordings)

Christian Wolff

"For Prepared Piano"

from Kompositionen 1950-1972

(Edition RZ)

Christian Wolff

"Tilbury 2"

from Tilbury Pieces ; Snowdrop

(Mode Records)

Christian Wolff

"For 1,2 or 3 People"

from Kompositionen 1950-1972

(Edition RZ)

Christian Wolff

"Peace March No.1"

from (Re):Making Music

(Mode Records)

Christian Wolff

"Travelling Melody(XII.16-27.98),for Walter Zimmermann"

from Incidental Music and Keybord Miscellany

(Mode Records)

Howard Skempton

"Teneramente" from the Chamber Concerto

from Somewhen

(NMC)

Christian Wolff

"For Morty"

from 8 Duos

(New World Records)

Christian Wolff

"Prelude 5"

from Bread and Roses

(Mode Records)

Baka Pygmies

"Hut Song"

from Cameroon Baka Pygmy Music

(Auvidis)

0 notes

Photo

studio mixtape: minimalism pt.3 -piano/silence-

https://www.mixcloud.com/downinyonforest/minimalism-vol3-piano-/

1. of late (piano: john tilbury) | howard skempton

2. music for marcel duchamp (piano: stephen drury) | john cage

3. für alina (piano: alexander malter) | arvo pärt

4. in memory of two cats (piano: ralph van raat) | john tavener

5. for bunita Marcus -excerpt- (piano: john tilbury) | morton feldman

6. gnossienne no.1 (piano: philip corner) | erik satie

7. letter from sergei rachmaninoff to arvo pärt | anton batagov

8. abgemalt (piano: r. andrew lee) | eva-maria houben

9. 1-100 | michael nyman

10. IV (piano: harold budd) | akira rabelais

cover image:

robert ryman

core XII, 1995

#mixtape#music#arvo pärt#john cage#erik satie#akira rabelais#john tavener#morton feldman#howard skempton#anton batagov#eva-maria houben#michael nyman#harold budd#john tilbury#stephen drury#alexander malter#ralph van raat#philip corner#r. andrew lee

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Manuel Zurria – Again & Again, 2xCD, ANTS records, Roma, Italy, June 2020

https://ants4.bandcamp.com/album/again-again

Manuel Zurria is an Italian flutist born 1962, the interpret of many contemporary works for flute from the 1960s avantgarde to today's post-modern works, which he performs with or without electronics, re-recording, or extraneous noises. Zurria also premiered multiple pieces he commissioned to living composers.

This 2xCD set is the 3rd volume of a trilogy focusing on Minimalist composers. I'm not familiar with vol.1, but I enjoyed vol.2 'Loops4ever' back in 2011, collecting radical sound experiments for electronics, vocals and weird sound treatments and occasionally flute. Titled 'Again & Again', the present record is a survey of the many colors of American and European Minimalist music for the flute including familiar names like Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Howard Skempton, James Tenney, Kevin Volans or Tibor Szemző, as well as little known composers from Slovakia or Lithuania.

The re-recording technique favored by Zurria on many tracks can conjure up otherworldly sonorities, from dreamy delay effects to massive accumulation. Zurria also adds extraneous sounds here and there, his signature sort of, like in Philip Glass' Dances #2 and 4, originally for organ, and here rendered as joyful, exquisite dances for flutes, toy instruments and environmental sounds like train – both tracks are some of the highlights of the album for me, though my favourite has to be Tibor Szemző's Water-Wonder, a sublime, dreamy build-up for 4 different flutes exploring homophonies between actual flutes and delay effect.

On several occasions, Zurria appropriates compositions originally for saxophone, organ, piano or percussion and reconfigure them according to his own tastes, with or without flute – like Steve Reich's Clapping Music, here interpreted with handclappers (!). This variety of approach provides diversity and keep things interesting throughout, yet an inevitable cumulative effect arises from such an anthology which should be appreciated through little sips rather than one long sitting. [review by L.F.]

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alessio Bax

(via Home listening: Howard Skempton piano works and more | Music | The Guardian)

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

Howard Skempton Lento ...T i m e..,t o..,f l y...:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pesaro, c'è Musica Inaudita alla Chiesa dell’Annunziata

Pesaro, c'è Musica Inaudita alla Chiesa dell’Annunziata.

Torna a Pesaro la musica contemporanea con Musica Inaudita. Dopo la prima stagione del 2017, l’Ente Concerti propone nella nuova edizione due concerti dedicati alle più recenti frontiere della musica colta con prestigiosi interpreti ed esecuzioni di prime assolute ospitati nella Chiesa dell’Annunziata di Pesaro. Il filo rosso della manifestazione si dipana intorno allo stile italiano degli ultimi secoli e alle riflessioni sulla musica del passato riletta e reinterpretata con gi occhi degli autori dell’oggi.

Protagonisti del cartellone sono proprio due tra gli strumenti storicamente più recenti, il sassofono e la fisarmonica, ai quali quindi viene chiesto di incarnare l'antico e il moderno allo stesso tempo, lanciando inoltre la sfida di far dimenticare, per il tempo del concerto, la propria veste e il proprio suono di strumenti popolari, ancora radicati nella coscienza collettiva.

Sabato 17 settembre

Il SEEM Sax Quartet, ensemble di sassofoni composto dai giovani e talentuosi Eleonora Fiorentini, Matteo Rossini, Sara Albani ed Emilio Bastari, presenta un affascinante viaggio nella musica del presente, proponendo pagine di affermati autori di oggi, quali Lamberto Lugli, Paolo Boggio, Michele Mangani – tutti docenti del Conservatorio Rossini di Pesaro – a fianco di composizioni di giovani autori quali Nicola Gaeta, Alessandro Meacci e Ettore Figliola. Proprio a quest’ultimo è affidato il brano finale del concerto, Curon, eseguito in prima assoluta per l’occasione dall’ensemble di fiati.

Giovedì 29 settembre

Francesco Gesualdi guida il pubblico in un viaggio nella fisarmonica del passato e del presente con un programma in cui vengono magistralmente rappresentate le composizioni e l'arte dei grandi Girolamo Frescobaldi e Carlo Gesualdo, accostati, per una certa analogia da scoprire, alle composizioni di autori della musica d'oggi (Mauro Montalbetti, Howard Skempton, Laurence Crane, Antonio Agostini). Ad impreziosire il tutto, in programma anche la prima esecuzione assoluta di Sand, brano del 2022 del compositore pesarese Danilo Comitini, commissionato dall’Ente Concerti di Pesaro proprio per la nuova edizione di Musica Inaudita.

Biglietti

- Posto unico: € 5,00. Vendita online su www.liveticket.com e rivendite del circuito.

- Biglietteria in loco il giorno dello spettacolo dalle ore 17.30.

- Informazioni Ente Concerti Pesaro (0721 32482 - [email protected]).

Read the full article

0 notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: name pieces by Sean Clancy

0 notes

Text

Man and Bat für Bariton & Kammerensemble - Howard Skempton https://www.awin1.com/pclick.php?p=25945571799&a=350383&m=15108&utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

Scores

Based on excerpts from the text: Keeping Score: Notation, Embodiment, and Liveness By Hendrik Folkerts.

“To approach a definition: the score is a notational device that connects the material of a discipline—ranging from music, dance, and performance to architecture, linguistics, mathematics, physics—and its systems of knowledge to a language that produces description, transmission, and signification, in order to be read, enacted, or executed in whatever form desirable.”

Exercise:

Make a score of your performance

think of:

1. Acts / scenes / chapters - how do the following take part in these and where?:

2. Characters

3. Movements

4. Outfits

5. Sound / video - amplified voice? lights?

6. Props - are they activated? How do these move or change?

Cornelius Cardew

Cornelius Cardew, Treatise (1963–67), EP 7560, musical score (excerpt), assigned 1970 to Peters Edition Limited, London

English experimental music composer, and founder (with Howard Skempton and Michael Parsons) of the Scratch Orchestra, an experimental performing ensemble. He later rejected experimental music, explaining why he had "discontinued composing in an avantgarde idiom" in his own programme notes to his Piano Album 1973[full citation needed] in favour of a politically motivated "people's liberation music". (wikipedia)

“Cardew’s method was premised on a dissolution of the hierarchies and boundaries between composer and interpreter, as well as between performers active in different fields of performance, from music to visual art. The Scratch Orchestra had no fixed leader or conductor; rather, everyone was equally involved and implicated in the enactment of the score. The orchestra consisted of both musicians and nonmusicians acting as one “assembly” in a collective state of continuous training and research. The name of the orchestra refers to each member notating their accompaniments (understood as “music that allows a solo”) in a musician’s scratch book, in whatever notational language they see fit: “verbal, graphic, musical, collage, etc.,” as Cardew put it in his “constitution” for the group.”

Scratch Orchestra link here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8-4yl3Zvdo&feature=emb_title

youtube

Treatise (1963–67), Musical score.

“The show, curated by Barbara Held and Pilar Subirà (Possibility of Action: The Life of the Score at the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona Study Center in 2008), reversed the conventional understanding of a score as an abstract representation of tone, taking instead as their starting point Cage’s contrary notion of the score as a representation of action with a unique and unpredictable result. The score is a generator of an action, they wrote, “to be performed, the outcome of which is unknown, and an end result that can never be repeated.”3 This view adheres to a typical chronology in which the score precedes the live enactment, standing as a precursor for a future iteration. The “unknown outcome” indicates the importance of chance and singularity assigned to the enactment of the score (particularly with respect to Cage), claiming it as the site of origin and performance as the site of singular presence, effect, and changeability.” (...) In the case of the Scratch Orchestra, its political dimensions include the democratic way its members developed a language for the score, in which they took a written instruction by Cardew and each developed it into myriad methods and forms of notation.”

Jani Christou

Greek composer.

Strychnine Lady (1967)

This work belongs to Christou’s last compositional period, during which he experimented with a personal art form that involves stage performance, mythical archetypes, dramatic elements and avant-garde materials and means. At this time, he also introduced new concepts, such as metapraxis and protoperformance, in order to engage with elements of the unconscious, influenced, in particular, by the field of analytical psychology as shaped by the Swiss psychologist, Carl Jung (1875–1961). (From: https://llllllll.co/t/experimental-music-notation-resources/149/367)

Strichnine Lady Link here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVSTUR6uBSI

Epicycle, 1968.

“The score for his late piece Epicycle (1968) includes both written instructions and drawn images that describe how to spatialize and time the performance, all of which lead to the execution of a “continuum”—that is, a continuous space for performance that participants could step in and out of and where, potentially, every observer could be cast as a performer”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IuPHwdazjSs

(...) The interpreter becomes as much the “author” of the score or composition as the composer, if not more so, and the prevalent dialectics of origin(al) and result should be abandoned. Through the transaction of interpretation and subsequent execution (or in the case of Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra, the fabrication of score within a collective), the score becomes part of its own iteration. Within the language systems that are produced, the relationship between score and performance evolves as interdependent, and meaning is produced through a process of transaction, iteration, and repetition, akin to the notion of iterability that Jacques Derrida discusses in “Signature Event Context.”

John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer, music theorist, artist, and philosopher. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading figures of the post-war avant-garde. Critics have lauded him as one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. (wikipedia)

4′33′’ - Silent piece

youtube

Fontana Mix, 1958

«Fontana Mix» consists of a total of 20 pages of graphic materials: ten pages covered with six curved lines each, and ten sheets of transparent film covered with randomly-placed points. In accordance with a specific system, and using the intersecting points of a raster screen, two of the pages produce connecting lines and measurements that can be freely assigned to musical occurrences such as volume, tone color, and pitch. The interpreter no longer finds a score in the customary sense, but rather a treatment manual for the notation of a composition.

________________________________

“(...) the score can easily remain within the autonomy of its own materiality, but it may also manifest as or lead to the production of another object or live enactment, sketched out by the parameters of the score’s language.”

Greta Bratescu

Atelierul—scenariul (The Studio—the film script) (1978), charcoal, colored pencil, and pastel on paper, 89.5 x 116.8 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York

Script developed for the performance film The Studio (1978)

“The script for The Studio, which consists of written instructions accompanied by miniature drawings of Brătescu’s studio, invokes this space as a stage that is literally inscribed with the actions of the artist: lie down, wake up, walk around, sit, lie down, etc. In the film, the transition between the first two scenes (“The Sleep” and “The Awakening”) and the third sequence (“The Game”) marks the passage from Brătescu’s purely private experience—sleeping and awakening, unaware of any external presence—to a situation in which the artist is conscious of the camera’s gaze and starts to perform. Brătescu is both the subject that performs and the object that is observed by herself as the one operating the camera; her studio is both a private and a public space. The script for The Studio is an important interlocutor between the subjectivity and objectivity that is enacted in the simultaneously private and public atmosphere of the artist’s studio. The figures she draws to represent herself in the score, abstractions of her own body, constitute a rudimentary style of self-portraiture. The text that accompanies and is superimposed on these drawings, in turn, references the actions of her body that manifest in the space of the studio as well as on film. The score highlights Brătescu’s role as author, interpreter, actor, and spectator in her work as it moves between self-portraiture, auto-instruction, and enactment. “

Film Still from The Studio, 1978.

“(...) operations of chance, the relationship between language (as score) and event, and what Lucy Lippard described as the “dematerialization of the art object” in the American art context of the 1960s and 1970s: The curators’ selections included Yoko Ono’s instructional scores, Ian Wilson and Robert Barry’s conversation pieces, and Lawrence Weiner’s instructions for wall drawings, to name a few examples. Lippard’s notion of the dematerialized encompasses a wide range of media in which “the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary” and that “stress the acceptively open-ended.”

Yoko Ono

Instructional Scores

Conversation Piece, an event score from Grapefruit, 1964.

Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys (12 May 1921 – 23 January 1986) was a German Fluxus, happening, and performance artist as well as a painter, sculptor, medallist, installation artist, graphic artist, art theorist, and pedagogue. (wikipedia)

Score for Action with Transmitter (Felt) Receiver in the Mountains, 1973

Fluxus

Founded in 1960 by the Lithuanian/American artist George Maciunas, Fluxus began as a small but international network of artists and composers, and was characterised as a shared attitude rather than a movement. Rooted in experimental music, it was named after a magazine which featured the work of musicians and artists centred around avant-garde composer John Cage.

The Latin word Fluxus means flowing, in English a flux is a flowing out. Fluxus founder Maciunas said that the purpose of Fluxus was to ‘promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art’. This has strong echoes of dada, the early twentieth century art movement.

Fluxus played an important role in opening up the definitions of what art can be. It has profoundly influenced the nature of art production since the 1960s, which has seen a diverse range of art forms and approaches existing and flourishing side-by-side.

Fluxus had no single unifying style. Artists used a range of media and processes adopting a ‘do-it-yourself’ attitude to creative activity, often staging random performances and using whatever materials were at hand to make art. Seeing themselves as an alternative to academic art and music, Fluxus was a democratic form of creativity open to anyone. Collaborations were encouraged between artists and across artforms, and also with the audience or spectator. It valued simplicity and anti-commercialism, with chance and accident playing a big part in the creation of works, and humour also being an important element.

Many key avant-garde artists in the 60s took part in Fluxus, including Joseph Beuys, Dick Higgins, Alice Hutchins, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Ben Vautier, Robert Watts, Benjamin Patterson and Emmett Williams. (https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/fluxus)

Intentionally uncategorizable, Fluxus projects were wide-ranging and often multidisciplinary, humorous, and based in everyday, inexpensive materials and experiences—including everything from breathing to answering the telephone. When asked to define Fluxus, Maciunas would often respond by playing recordings of barking dogs and honking geese, perhaps confounding his questioner but also demonstrating the experimentation and embrace of absurdity at its core. Performances—which Fluxus artists called “Events,” in order to distinguish them fromHappenings and other forms of performance-based art—were a significant part of the movement. These were largely based on sets of written instructions, called “scores,” referencing the fact that they were derived from musical compositions. Following a score would result in an action, event, performance, or one of the many other kinds of experiences that were generated out of this vibrant movement. (https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-fluxus-movement-art-museums-galleries)

Fluxus scores

In many ways, most Fluxus ‘scores’ (for music or other kinds of performance and/or composition) are fairly legible as scripts for performance/enactment; i.e. the text comes first and the performance after (if at all). Certainly, one of the interventions (and charms) of Fluxus scores were the openness of the scores, where interpretation and chance were much more important than following the letter of the law, as one might in traditional sheet music, for example. As such, reading Fluxus scores as performance texts allows us to see how writing can activate art/life works that writing cannot contain or control. (https://jacket2.org/commentary/how-make-us-flux-scoresscriptsinstructions)

Toshi Ichiyanagi. Music for Electric Metronome. 1960 (Fluxus Edition announced 1963). Score. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 11 3/16 x 15 3/16″ (28.4 x 38.5 cm)

Yasunao Tone. Anagram for Strings. 1961 (Fluxus Edition released 1963). Score. Master for the Fluxus Edition, typed and drawn by George Maciunas, New York. Ink and typewriting on transparentized paper, 8 1/4 x 11 11/16 (21 x 29.6 cm)

“While these scores can be enacted, their producers considered them stand-alone art objects and often exhibited them in galleries to be experienced for their visual qualities, for example in Tokyo’s Minami Gallery, where the 1962 Exhibition of World Graphic Scores introduced works by Fluxus artists George Brecht, Dick Higgins, and La Monte Young to a Japanese audience.” (https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/12/21/exhibiting-fluxus-keeping-score-in-tokyo-1955-1970-a-new-avant-garde/)

“(...) the score can easily remain within the autonomy of its own materiality, but it may also manifest as or lead to the production of another object or live enactment, sketched out by the parameters of the score’s language.”

(...)

To wade into the muddy waters of the score as an “original,” it is key to look more closely at the score’s relationship to temporality and chronology. In the traditional musicological sense, the score acts as a precursor to an event. Each live enactment can be traced back to the score as a kind of “core material,” so that in the score future performances—and thus temporalities—are latent. Additionally, a score can emerge from a live iteration, or, at the least, may be adapted according to it. Though highly unstable in terms of representation, the score has a documentary aspect—and in turn becomes a forecast of future performances—thus further augmenting the complex multi-chronicities that the score conjures.

José Maceda

Filipino composer José Maceda. Trained as a concert pianist in the 1930s and later obtaining degrees in musicology, anthropology, and ethnomusicology in the United States, Maceda started composing his major works in the 1960s.

(...) Maceda’s lifelong endeavor (he died in 2004): a dissimulation of the cultural hegemony of Occidental music and its core principles of logic and causality in favor of researching a set of values indigenous to the eco-social relations, oral and mystical traditions, production of musical instruments from natural materials, and concepts of time in Southeast Asian culture26—in short, a decolonization of Filipino music and its forms of notation in the context of Southeast Asia.

One of Maceda’s most ambitious works, entitled Ugnayan (Correlation, 1974), is a composition of Filipino village music that was scored and recorded on twenty channels that were then broadcast simultaneously on twenty of Manila’s radio stations. Hundreds of thousands of the city’s residents gathered in public spaces with portable transistor radios to listen to the different tracks created for each station, with the citizenry collectively assembling the composition in a massive public ritual of converging indigenous history, time, and space in the urban fabric.

-----

“Performance, as an act that exists momentarily, has been generally discussed within an archival logic that privileges materiality over immateriality, celebrating its ephemerality, impermanence, and ontological unicity—“performance’s being … becomes itself through disappearance,” as Peggy Phelan initially put it.32 In his catalogue essay for the 1998 exhibition Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949–1979 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Paul Schimmel even goes so far to say that performance is constituted by a drive towards destruction, marking an “underlying darkness” in performative work that is informed by a seemingly Freudian death drive.33 The definition of performance as that which cannot remain and thus “disappears” relies on a rationale that considers performance as antithetical to history, memory, and the archive, an unjust fate it shares with other immaterial practices, such as oral histories, storytelling, and gestural practices, that are also always incomplete, always reconstructive, and thus escape lineage to a singular original.”

“Under this new understanding of the archive as including the corporeal, the body is no longer the object on which a choreographic notational device is projected. The flesh becomes the score, the muscle, and the tissue—the languages through which a work is interpreted, transmitted, embodied, and then performed. This paradigm defies an understanding of the archive as an architecture of objects or documents and opens up ways to think about it anew, as reflecting movement and sound, bodies and waves, time and variations. Within this archive structure, the flesh is activated as a “physicalized relational field of interaction, intensities, techniques, histories, traces, and relicts of experienced information … with its own history and genealogy,” as Van Imschoot argues.38 This position paves the way for a different understanding of the score, away from the terms of a material object to something that can be held in the human body, or, at the very least, exists always in connection with embodiment through enactment.”

Katalin Ladik

From the late 1960s on Ladik started to publish her poems and, subsequently, to perform and record them as speech acts. During these performances, which often included music and choreographed movement, she transformed the language of her written poetry, which necessarily adhered to a linguistic system of regulation. Vowel prolongation, repetition of consonants, words that seem to come from her gut, her throat, her mouth; such techniques became an early repertoire that was often performed as a shamanistic ritual, enacting the poems through the artist’s body, as an extension of her voice and her language. Sentences became embodiments, words produced their meaning through ritualized gestures, letters were spat out or swallowed—a corporeal manifestation of language.

UFO Party, 1969.

Pauline Oliveros

1932-2016

Pauline Oliveros' life as a composer, performer and humanitarian was about opening her own and others' sensibilities to the universe and facets of sounds. Her career spanned fifty years of boundary dissolving music making. In the '50s she was part of a circle of iconoclastic composers, artists, poets gathered together in San Francisco. In the 1960's she influenced American music profoundly through her work with improvisation, meditation, electronic music, myth and ritual.

She founded "Deep Listening ®," which came from her childhood fascination with sounds and from her works in concert music with composition, improvisation and electro-acoustics. She described Deep Listening as a way of listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, of one's own thoughts as well as musical sounds. (https://paulineoliveros.us/about.html)

sonic meditations (1974)

Published in 1974, Pauline Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations is one of the most seminal, if not under-recognized, works in late 20th century avant-garde musical thought. Within it, the grande-dame of American Minimalism not only departs from standard musical notation, but with the entire conception of where music grows from, and how it can be realized. Her focus lies on the cognition of sound – largely through the practice of meditation, and group participation. She highlights the virtues of meditation for making sounds, imagining sounds, listening to, and remember sounds, and sets into action twelve text scores to help practitioners realize these new relationships. Sonic Meditations is as much a workshop for use, as it is a series of pieces. (https://blogthehum.com/2016/09/13/pauline-oliveros-sonic-meditations-1974-the-complete-text-and-scores/)

Guillermo Galindo

(b. 1960, Mexico City) is an experimental composer, sonic architect and performance artist.

Score for War Map (2017)

Acrylic on polyester military blanket 152.4 × 208.3 cm (detail)

In War Map, Galindo uses a military-green blanket as the substrate for a printed composition drawn from collaged and overlayed representations of immigration patterns as digitally mapped on the website Lucify.com. The blanket was donated by Mr. Kurt Heldmann, who works in the reception camp for refugees in Calden, Germany. By combining the visual languages of maps and graphs; musical notation; and more organic, natural motifs suggesting proliferation and motion, the artist skillfully demonstrates that these strategies for visually representing movement through time and space have much in common, and that all movements — even tragic or difficult migrations of people — can be represented such that their own subtle rhythms and musicality are revealed. Galindo describes the digital representations of migration patterns as “surprisingly archaeological” in their look, yielding the sense of a surreal, Borgesian map, and explains that he manipulated the work’s various shades of blue in an effort to mimic the Aegean Sea. (http://www.magnoliaeditions.com/artworks/we_all_have_a_place_at_the_table/)

Score for We All Have a Place at the Table (2017)

Acrylic on cotton tablecloth 54.2 × 157.5 cm (detail)

His third work, We All Have a Place at the Table, is printed on a found tablecloth that still bears stains from meals at the refugee camp. All of the abstract patterns and shapes printed upon its surface were derived from the modest but sophisticated embroidery that already adorned the tablecloth – a simple pattern of repeated small modules whose uncanny resemblance to systems of notation and representation used in music or mathematics appealed immediately to the artist.

(http://www.magnoliaeditions.com/artworks/we_all_have_a_place_at_the_table/)

0 notes

Text

David Gryn on the Art Hour, Soho Radio presented by Vassiliki Tzanakou

David Gryn on the Art Hour, Soho Radio presented by Vassiliki Tzanakou

The Art Hour on Soho Radio with Vassiliki Tzanakou

Interview with David Gryn, Daata Editions

David’s Playlist inc: Augustus Pablo & Jacob Miller, Arvo Pärt, Vaughan Williams, Eleni Karaindrou, Mungo’s Hi Fi & Brother Culture, Howard Skempton

https://www.mixcloud.com/sohoradio/the-art-hour-28042019/

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note