#zuleika dobson

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

the lillycrew actually works pretty well for women's hairstyles from the end of the long 19th century bc you can move the hair around so much ^_^ (it's zuleika dobson & mathilde bouvier again btw)

#see the flag backgrounds. see my headcanons + oc information. ok#zuleika dobson#oc: mathilde bouvier#fl ocs#ocs

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"One is taught to refrain from irony, because mankind does tend to take it literally." #zuleikadobson

In his time, Max Beerbohm was known as an essayist, parodist and caricaturist, publishing under his first name only; however, nowadays he’s best remembered for his one novel, “Zuleika Dobson“. Publisher Mike Walmer has been flying the flag for Beerbohm, and I’ve previously covered his reissues of “The Works” and “More“, in handsome paperbacks (and I still have “Yet Again” lurking!) Now Mike has…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

But beauty and the lust for learning have yet to be allied

Zuleika Dobson by Max Beerbohm

1 note

·

View note

Text

James Elkington & Nathan Salsburg Interview: Poise, Levity, and Easygoingness

Photo Credit: James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg

BY JORDAN MAINZER

All Gist (Paradise of Bachelors), the third album of guitar duets from exploratory, thoughtful players James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg, sounds like what it is: two longtime friends and collaborators playing together, equal parts casual and focused. Since their 2015 album Ambsace, each has been busy, separately and together. Elkington's released three solo albums, played as part of Eleventh Dream Day, Brokeback, and Jeff Tweedy's live band, and recorded with Steve Gunn, Nap Eyes, and many more. Salsburg's dropped a bevy of albums and has played on records by Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Shirley Collins, and others. Meanwhile, the two have come together on four records by Salsburg's partner Joan Shelley, and Elkington produced Salsburg's Psalms, his 2021 album of arrangements of Hebrew psalms. Their duo records, however, are born of the most natural collaboration, each bringing to the table melodies they think--perhaps know--the other will respond to, combining them, and being open to feedback or changing gears entirely.

All Gist, specifically, carries the distinct quality of the Chicago winter during which it was recorded: You can picture Elkington and Salsburg sitting around the kitchen table, each culling from their vast repertoires and tendencies, creating something to warm their bodies and hearts and perk their heads and ears, unaware of any blusters outside. The songs are reflective of their shared artistic interests and inspirations, and they're rounded out by the presence of musical contemporaries with whom each has fostered relationships over the years. Opener "Death Wishes to Kill", which takes its title from T.F. Powys' Unclay, sports lilting guitar melodies that offer an affable sway, along with Wanees Zarour's violin solo. The minimal "Explanation Point" bounces along a groove that sounds bigger than it is, almost gestalt, as Jean Cook's strings and Anna Jacobson's brass shimmer. Moments of percussion come from other instruments like hand drums ("Long in the Tooth Again"), along with Wednesday Knudsen's woodwinds ("Nicest Distinction"), or as part of the sheer tactility of guitar scrapes and textures. The self-reflexive "Numb Limbs" gets its title from the physical aftereffects of playing a song that took forever to come together; you feel the spritely guitar picking and breakneck tempo in your own fingers.

Of course, All Gist has a few interpolations, namely a gentle, quiet, start-stopping version of Howard Skempton's "Well, Well, Cornelius" and a taut, concise combination of two traditional Breton dance tunes in "Rule Bretagne". Easily, the most unexpected song on the album is a version of Neneh Cherry's classic late 80s jam "Buffalo Stance". Oscillating and slowed down to an expanse, one guitarist plays Cherry's lyrical line, the other the song's instrumental melody, making something both recognizable and nostalgic as well as emblematic of the duo's adventurous nature. That combination, indeed, is the gist of Elkington and Salsburg.

Earlier this month, both guitarists answered some questions over email about All Gist, their creative process, covering songs, and their sometimes-overlapping, oft-diverging taste in art. Read their responses below, edited for clarity.

Photo Credit: Joan Shelley

Since I Left You: Why was it time again to make an album together?

James Elkington: We’d been talking about it since we made the last one, but the truth is that we’ve both just been too busy. I started making solo records again after the last one, plus I got to produce one for Nathan, and we both help out with Joan Shelley’s records, so it never felt like we weren’t working together anyway. We were just working on projects in a different way. I think that Nathan and I both think there’s something about the duo’s music that is different from the other things we do, so we were keen to get back to it at some point. Fortunately for us, we got an invitation to play at a guitar festival in Chicago, and we used that as an excuse to start working on new material. I should also mention that our wives kept bugging us to do it again.

SILY: How was your collaboration on All Gist unique as compared to your other records together, and how was it similar?

JE: We hadn’t played together like this for something like 7 years, so I was interested to see if we could even do it. But our writing together was as quick and easy as it ever was, and in that sense, it was really similar to how we worked before. Nathan has always worked with longer forms than me, but this time, I wanted to follow his lead a bit more in terms of writing longer pieces with less changes and more textures. We weren’t concerned this time with being able to play all of this stuff live, so we left more space for orchestration and overdubs.

Nathan Salsburg: We’ve each lived through a world of experiences in the past ten years, musical and otherwise. Now that we’re each squarely into our middle age, I think the poise, levity, and easygoingness that should be attendant on this period of life show up in the music at [the] pitch they didn’t in the past.

SILY: Was there a lot of improvisation in the process of combining the different instrumental motifs you each brought to the recording session?

JE: Because we don’t have a great deal of time to work together, we find things go much quicker if we come up with rough musical sketches by ourselves and then present them to the other. Nothing is ever written in stone, and the level of trust is very high. Anything Nathan suggests for one of my ideas is going to improve it. Both of us are more concerned with coming up with something that sounds cohesive and keeping the ball rolling than having any personal agenda for how this thing should be, and we always leave enough space for us to be surprised by what we end up with. I rarely have any idea what Nathan is playing, but I like how it sounds when it’s finished. We did experiment with recording something completely improvised and liked the results, but it sounded like a different record, so we didn’t use it. Maybe that’ll be the next one.

SILY: How or at what point in making each song do you determine whether it needs more musical accompaniment, from other instruments and/or players?

JE: That’s a good question, and I’m not sure I have an answer, but the plan seems to be to write a piece that can stand by itself for the two guitars, record that to our satisfaction (which is nearly always the first take we can manage that has all the right parts), then start throwing other instruments at it to see what sticks. Most of that approach is me in my studio adding things and then taking them off again. There are certain pieces where, as were writing them, we can hear that a solo instrument would sound great in a certain part. Wannees Zarour’s solo in "Death Wishes To Kill" was like that. There are songs, like "All Gist Could Be Yours", where for a repeating chord sequence to have the effect we’re going for, its going to need a lot of support from other instruments, and we talked about that as we were writing it.

Cover art by Chris Fallon

SILY: Do you have a backlog of other people's songs you think might be fun or fulfilling to cover or reimagine as a guitar duet? What makes a song fit for a cover from your two artistic voices?

JE: Well, I’m a little concerned that there’s a potential novelty aspect to our doing a lot of covers, but maybe it's okay. We certainly didn’t go out of our way to think of any for this record. Nathan suggested "Buffalo Stance" early on just because he loved the song and all the parts. I was resistant at first, just because I thought there wasn’t enough there for us to work with harmonically, but there’s so much good stuff going on with the synths and the bassline in that tune that it became more a process of picking and choosing what aspects of the song we wanted to shine a light on, at what time. Our Smiths cover from the last record is like that, too. It switches from the guitar line to the vocal depending on where we’re at or what seems to be most important, so I suppose we have a system for doing this. I think the only criteria we have for picking a song is whether one of us really really likes it and the other one can get their head around it.

SILY: "Death Wishes To Kill" takes its title from a T.F. Powys novel you both read. Do the two of you tend to recommend books, films, albums, etc. to each other a lot? Do you ever find you're about to recommend the same thing to one another?

JE: I was going to write that we don’t have a huge amount of overlap, but I’m remembering going to his house when we hadn’t known each other long and being confronted with what appeared to be a wall of my own books. Its not as if we like exactly the same things, but there are some writers and records that we both like that NO-ONE else I can think of likes, so when Nathan suggests a book, I usually get to it pretty quickly. I think Nathan was reading the Powys novel, Unclay, and sent me a screen shot of one of the passages in the book with the caption "this is for you" underneath. He also sent me a link to an Australian liquor store commercial from the early 90’s because he knew it would make me laugh for a day and a half, and it did.

NS: I remember we made common cause over Max Beerbohm not long after we met—Zuleika Dobson, maybe—but yeah, we each have some preoccupations that the other couldn’t give much of a shit about. Like, I can’t say mid-century British horror movies do a whole lot for me. I’m remembering when Jim spent the better part of an hour trying to explain the appeal of U.S. Maple, and I can’t say he succeeded. And Jim couldn’t care less about rural American string-bands of the late 1920s. But when we have an overlap—Unclay, say, or the totally under-appreciated Yorkshire singer-songwriter Jake Thackray, or Alan Partridge—and yes, these overlapping things do tend to all be English—it’s always stuff we’re super, super jazzed about.

SILY: Can you tell me about the cover art for All Gist?

NS: The artist’s name is Chris Fallon, an old friend of mine from when I lived in New York City 20+ years ago. He’s a phenomenal painter, and I love his figures, his palette, and the scenes/settings that he dreams up. I asked him to create a portrait of us, and this is what he did. He’s never met Jim and hasn’t seen me in quite a few years, but I feel like he nailed something of Jim’s and my dynamic, equal parts earnest, bizarre, silly.

youtube

#interviews#james elkington#nathan salsburg#paradise of bachelors#all gist#james elkington & nathan salsburg#james elkington and nathan salsburg#ambsace#eleventh dream day#brokeback#jeff tweedy#steve gunn#nap eyes#bonnie “prince” billy#shirley collins#joan shelley#psalms#t.f. powys#unclay#wanees zarour#jean cook#anna jacobson#wednesday knudsen#howard skempton#neneh cherry#chris fallon#the smiths#max beerbohm#zuleika dobson#u.s. maple

0 notes

Text

"A crowd, proportionate to its size, magnifies all that in its units pertains to the emotions, and diminishes all that in them pertains to thought."

Max Beerbohm, Zuleika Dobson

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Beerbohm

"Death, as he had said, cancelled all engagements."

Zuleika Dobson or An Oxford Love Story

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But the loveliest face in all the world will not please you if you see it suddenly, eye to eye, at a distance of half an inch from your own.

Max Beerbohm, Zuleika Dobson

#Zuleika Dobson#Max Beerbohm#lit#literature#literary quotes#book#books#bookstagram#bookworm#quotes#quote#book quotes#quoting#quotation#book quotations#reading#currently reading#reads#reader#to read#tbr#to be read#love yourself#self love#self-love#wisdom#wise

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Beerbohm and the one-liner.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

But the dullard's envy of brilliant men is always assuaged by the suspicion that they will come to a bad end.

Zuleika Dobson by Sir Max Beerbohm

0 notes

Text

for my purposes, the referenced texts E.M. Forster made in his book, The Aspects of the Novel.

William George Clark. Gazpacho: Or Summer Months in Spain.

—. Peloponnesus: Notes of Study and Travel.

—. The Works of William Shakespeare - Cambridge Edition.

—. The Present Dangers of the Church of England.

John Bunyan. The Pilgrim's Progress.

Walter Pater. Marius the Epicurean.

Edward John Trelawny. Adventures of a Younger Son.

Daniel Defoe. A Journal of the Plague Year.

—. Robinson Crusoe.

—. Moll Flanders.

Max Beerbohm. Zuleika Dobson.

Samuel Johnson. The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia.

James Joyce. Ulysses.

—. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

William Henry Hudson. Green Mansions.

Herman Melville. Moby Dick.

—. "Billy Budd".

Elizabeth Gaskell. Cranford (followed by My Lady Ludlow, and Mr. Harrison's Confessions).

Charlotte Brontë. Jane Eyre.

—. Shirley.

—. Villette.

Sir Walter Scott. The Heart of Midlothian (part of the Waverley Novels).

—. The Antiquary (part of the Waverley Novels).

—. The Bride of Lammermoor (part of the Waverley Novels).

George Meredith. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel.

—. The Egoist.

—. Evan Harrington.

—. The Adventures of Harry Richmond.

—. Beauchamp's Career.

Leo Tolstoy. War and Peace.

Fyodor Dostoevsky. The Brothers Karamazov.

William Shakespeare. King Lear.

Henry Fielding. The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling.

—. Joseph Andrews.

Henry De Vere Stacpoole. The Blue Lagoon (part of a trilogy; followed by The Garden of God and The Gates of Morning).

Clayton Meeker Hamilton. Materials and Methods of Fiction.

George Eliot. The Mill on the Floss.

—. Adam Bede.

Robert Louis Stevenson. The Master of Ballantrae.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The Last Days of Pompeii.

Charles Dickens. Great Expectations.

—. Our Mutual Friend.

—. Bleak House.

Laurence Stern. The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

Virginia Woolf. To the Lighthouse.

T. S. Eliot. The Sacred Wood.

One Thousand and One Nights.

Emily Brontë. Wuthering Heights.

Charles Percy Sanger. The Structure of Wuthering Heights.

Johan David Wyss. The Swiss Family Robinson.

D. H. Lawrence. Women in Love.

Arnold Bennett. The Old Wives' Tale.

Anthony Trollope. The Last Chronicle of Barset.

Jane Austen. Emma.

—. Mansfield Park.

—. Persuasion.

H. G. Wells. Tono-Bungay.

—. Boon.

Gustave Flaubert. Madame Bovary.

Percy Lubbock. The Craft of Fiction.

—. Roman Pictures.

André Gide. The Counterfeiters.

Homer. Odyssey.

Thomas Hardy. The Return of the Native.

—. The Dynasts.

—. Jude the Obscure.

Anton Chekhov. The Cherry Orchard.

Oliver Goldsmith. The Vicar of Wakefield.

David Garnett. Lady Into Fox.

Alexander Pope. The Rape of the Lock.

Norman Matson. Flecker's Magic.

Samuel Richardson. Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded.

Anatole France. Thaïs.

Henry James. The Ambassadors.

—. The Spoils of Poynton.

—. Portrait of a Lady.

—. What Maisie Knew.

—. The Wings of the Dove.

Jean Racine. Plays.

I. A. Richards.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

👀

^ begun on april 11

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today being my birthday, i had the time and energy to finally do some drawing after ages of neither time nor drive. So, i spent that on sketching out some headshots of the recurring characters of 33 Usher Street, my 1920s (and beyond?) vampire hunters story. Meet the employees, management, friends, and nuisances of the Usher Street House of Antiquities and Curios, an estate management company specializing in settling the affairs of the unusually deceased. This is both a source of income and a cover for their real calling: the elimination of dangerous vampires and other hostile undead.

Solomon “Sol” Szombathy (gay intersex man), a Jewish dhampir of Romanian-American extraction (late of Pittsburgh, Vandalia) has arrived at the USHAC with his guardian in tow, after both of them got involved in a vampire attack. Sol’s ability to see the invisible and the surges of supernatural strength he gets when battling the undead are especially useful, as is the hawthorn-wood cane he uses to deal with the chronic pain he feels the rest of the time.

James “Jim” Cullock III (asexual cisgender man) is a Scottish immigrant who helped co-found the USHAC as the assistant of a longtime vampire hunter; his love of gardening has given him many potent botanical weapons against vampires, including especially hardy and richly-scented roses that repel most bloodsuckers. He’s taken to maintaining a backstage role for the most part, as his lifelong issues with visual hallucinations have gotten worse with age.

The Reverend Doctor Matteus J. Hammer (transgender man of no particular sexuality) is an aging monster hunter of no small repute, his experience having brought him briefly as a boarder to the Szombathy house. His recommendation brought Sol to Usher Street, but can the perspective of this eccentric wandering hero be relied upon?

Randolph Carter (in-denial bisexual cis man) was once an author of minor repute with a fondness for the strange and occult, but encounters with the genuinely supernatural have mellowed his previously bigoted worldview. While he still struggles to be a halfway decent person in a reality that is at odds with his beliefs, his expertise with languages, obscure subject matters, and research makes him at least a useful jackass when it comes to spending time among his books.

Pluton is a very good judge of character, for a one-eyed cat. And oddly skilled at making his way out of dangerous situations, to the point that one might almost think he has more than the usual nine lives. It’s no wonder that the USHAC often bring the cat along.

Constance “Connie” Wright (pansexual cis woman) is a former orphan with the miraculous talent to ‘chew’ raw materials into new shapes, a skill she most often uses to create nails for sealing up coffins and the like. Naturally, the rail-thin Connie’s favorite weapon is a heavily weighted steel sledgehammer, when she can’t just do some slugging with a sturdy baseball bat.

Dorotheea “Dotty” Szombathy (transgender lesbian) is a golem that once served as Sol’s guardian, and is now happily living as his adopted sister. Her ability to reshape her naturally earthen clay body pairs well with her immunity to most forms of vampiric attack, as an artificial being. Prone to switching between having difficulty speaking at all and being effusively loquacious, she finds it easiest to focus when she has something to occupy her hands and mind.

Marie Bosley (bisexual cis woman) was and is the greatest vampire hunter in the United States, even if these days she prefers to stay at home and listen to music. Her unmatched knowledge of apotropaic magic allows her to create boundaries and barriers that no vampiric influence can pass, and lets her open the way for her proteges.

Esther "Essie” Levi (asexual cis woman) is the self-proclaimed ‘fastest knot-tier east of the Rockies’, and an unmatched expert in knotting string, yarn, thread, and cord to achieve magical effects. Paired with a gift for strategic thinking and an eye for symptoms of vampirism, she can easily weave a web that no bloodsucker is going to get through.

Aleister “Al” Jones (gay cis man) is a multilingual expert in stealth, infiltration, and charm whose gentlemanly demeanor is in no way at odds with his fondness for boxing. Unfortunately for opponents that would see him as unarmed except for a disarming smile, he’s also the bearer of a pair of gloves lined with the relics of a Catholic saint invoked against vampires.

Wilhemina “Will” Fawkes (lesbian cis woman) is the USHAC’s resident machinery buff, with cutting-edge expertise in automobiles, radios, firearms, and more. Her fondness for artifice means that the only thing that can distract her from something shiny and new is an animated short at the nearest theater, and her love of testing the limits of machinery means that her allies often find she’s made unexpected ‘upgrades’ to important equipment.

Adriaen ten Boom (bisexual cis man) is the most senior of the employees of the USHAC, a skilled actor whose pyrokinetic gift makes his good looks more than just smoldering. In spite of these charms, he’s actually fairly naïve when it comes to romance, and is prone to charming his way into entanglements he didn’t mean to get into.

Smith the Mechanical Heel (just a real dick) is a World’s Fair experiment gone wrong, and now runs the criminal underworld in Jackson, Massachusetts—which puts him at odds with the USHAC, since that’s where their home base is. He sees most of the employees as potentially useful additions to his crew, but he’s especially interested in learning more about Dotty’s magically-constructed nature, in the hopes of making himself more lifelike. He’s not above getting involved in things that involve the undead....

The Ghosts of Madeline and Roderick Usher (cis lesbian and cis gay man) are the former owners of the land on which the USHAC was built, and haven’t moved on since the new tenants turned up. Freed of mortal concerns, they’re fond of teasing the living staff members, and serve as a second line of defense after Marie’s wards and magical traps. Roderick is absolutely certain that he’s going to get his ectoplasm all up on Randolph one of these days, and nobody feels up to questioning his taste in men; Madeline is the company gossip fiend and the best source of information on comings and goings at 33 Usher Street.

Dr. Joaquín de la Garza (closeted nonbinary queer) is a local physician who has a close working relationship with the USHAC, and is very fond of the mysteries and excitement they bring to his life. Exactly what brought a medical expert of Zapotec and Spanish heritage all the way up east is uncertain, but the good doctor seems to know a lot more about the supernatural than one might expect from just his familiarity with the secrets of the Usher Street staff.

Phoebe Khrysos (???) is a remarkably pristine ancient automaton, whose actual provenance is uncertain. Resembling a child made of silver, glass, and gold, she has a mischievous mystery about her that makes her more like a mechanical fairy than a precious relic. What motivates her and how she sees the living and the undead remain to be seen....

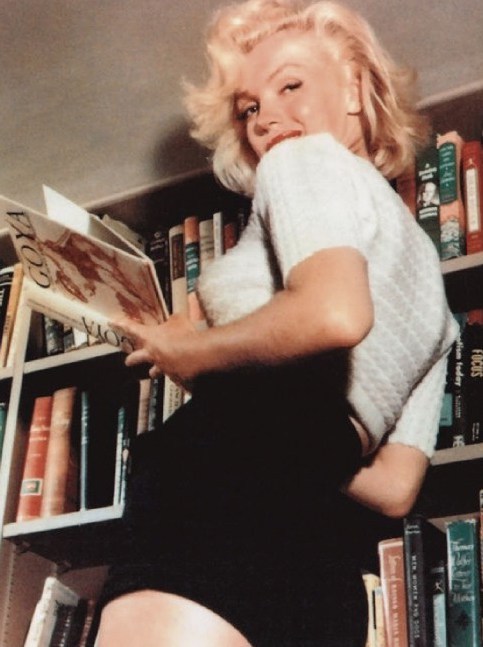

Zuleika Dobson (pansexual cis woman) is a a con artist, thief, and scammer who has broken many hearts and far more bank accounts; her lack of concern about what she leaves in her wake may have finally caught up with her when she targets some valuable goods in a city with a vampire problem. Can someone so untrustworthy be relied upon when there’s undeath to deal with, or will her self interest put her in the way of both bloodsuckers and the USHAC alike?

33 Usher Street leans heavily on the public domain, and will do so much more than just in the few characters here that originated elsewhere. Some of these designs are likely to change as the story develops, but i’m just so happy to finally get them on paper!

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Who's afraid of the campus novel?

Ever since Vladimir Nabokov published his lovely, sad, ruthless and very funny novel Pnin, the beginning of term has been a staple scene in the campus novel. "The 1954 Fall term had begun... Again in the margins of library books earnest freshmen inscribed such helpful glosses as 'Description of nature', or 'Irony'; and in a pretty edition of Mallarmé's poems an especially able scholiast had already underlined in violet ink the difficult word oiseaux and scrawled above it 'birds'."

The details of the scene change; the first paragraph of Don DeLillo's White Noise , for instance, is saturated with late 20th-century excess: "The station wagons arrived at noon, a long shining line that coursed through the West campus... students sprang out and raced to the rear doors to begin removing the objects inside..." Or, as Malcolm Bradbury put it in the first line of The History Man: "Now it is autumn again; the people are all coming back."

This academic year begins with Tom Wolfe's latest attempt to characterise an age. And despite those who believe that, while university life will continue, the novel of academia has had its day, Wolfe has chosen a campus novel - I am Charlotte Simmons, 600 pages set at a moneyed college on the eastern seaboard - with which to do it.

From a practical point of view, of course, the attractions of the campus haven't changed much: it is a finite, enclosed space, like a boarding school, or like Agatha Christie's country-houses (the campus murder mystery being its own respectable sub-genre); academic terms, usefully, begin and end; there are clear power relationships (teacher/student; tenured professor/scrabbling lecturer) - and thus lots of scope for illicit affairs; circumscription forces a greater intensity - revolutions have been known to begin on campuses, though that doesn't seem to have happened for a while. And it's all set against the life of the mind.

"The high ideals of the university as an institution - the pursuit of knowledge and truth," says David Lodge, author of some of the more popular campus novels of the last century, "are set against the actual behaviour and motivations of the people who work in them, who are only human and subject to the same ignoble desires and selfish ambitions as anybody else. The contrast is perhaps more ironic, more marked, than it would be in any other professional milieu."

The campus novel began in America, with Mary McCarthy's The Groves of Academe (1952), Randall Jarrell's reply to it, Pictures From an Institution (1954), and Pnin (1955). (Nabokov's Pale Fire is, inter alia, a campus novel, and a murder-mystery.) "Campus" is, of course, an American word, and Lodge makes the distinction between the campus novel and the varsity novel - the latter being set at Oxbridge, and usually among students, rather than teachers, thus disallowing the joys of Zuleika Dobson, or Jill, or Brideshead Revisited; he claims Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim (1954) as the first British campus novel, and a template.

To all the standard elements, Lodge explains, Amis added "the English comic novel tradition, which goes back through Evelyn Waugh and Dickens to Fielding"; i.e., an element of robust farce later elaborated by Tom Sharpe in Porterhouse Blue, for example, or by Howard Jacobson.

"I don't see why the campus novel has to consist of farce," says AS Byatt, who dislikes Lucky Jim, seeing it as both sexist and thoroughly anti-intellectual. "I find it baffling." She has much more time for what she calls true comedy, in Terry Pratchett's Unseen University, or in Lodge's Nice Work (1988), which she feels have more respect for a profession based on serious thought.

This is an older tradition, again. "I compare it to pastoral," says Lodge. "If you think of a comedy such as As You Like It, you get all these eccentric characters, all in one pastoral place, interacting in ways they wouldn't be able to do if they were part of a larger, more complex social scene. There's often an element of entertaining artifice, of escape from the everyday world, in the campus novel. Quite interesting issues are discussed, but not in a way which is terribly solemn or portentous."

The other, probably inevitable, addition was class. Much of the tension in Lucky Jim is between Jim Dixon and his socially superior boss; apart from the fact that she's simply prettier, the thing that binds Jim to his eventual girlfriend, Christine, is their mutual recognition of a kind of aggressive gaucheness, assumed to be more authentic than the baying, madrigal-singing Welches. But it's a fruitful collision nonetheless.

"If you're interested in the phenomenon of meritocracy, which transformed English society in the postwar period, then the university is - or was - a good place to observe it," says Lodge, who like many of his colleagues in the 60s and 70s was a first-generation university graduate. "The Kirks are, indeed, new people," wrote Bradbury in The History Man, which was published in the same year, 1975, as Lodge's Changing Places. "But where some people are born new people... the Kirks arrived at that condition the harder way, by effort, mobility and harsh experience."

These two seminal English campus novels are set in and immediately after "the heroic period of student politics", to quote Lodge's Nice Work, when new universities seemed to be appearing all over the country, change seemed possible, social mobility achievable, and promiscuity mandatory - the necessary mixing and mating of comedy, or farce, meshing nicely with the burgeoning sexual revolution and women's lib. And even though Bradbury's novel especially has a great sense of darkness, pointing, among other things, to the inequalities of unfettered sexuality at that point in time, both now read as historical novels, imbued with a quixotic hope.

But in English higher education everything is set, even in celebration, against Oxbridge, says Ian Carter, author of Ancient Cultures of Conceit: British University Fiction in the Post War Years (1990), and a professor at the University of Auckland, citing those who made the conscious choice to go to Sussex, for example, instead. The American campus novel was, he feels, better able to avoid the trap of class, "perhaps because American universities are so highly differentiated, so recognisably placeable; novels could take on a larger variety of themes without automatically having to deal with class."

Though the oil crisis of 1973 was the beginning of the end of the boom in new universities, Thatcher prompted the next great satirical subject: Lodge cites Andrew Davies's A Very Peculiar Practice, and his own Nice Work transfers the contrapuntal, mutually illuminating UK university versus US university structure of Changing Places to UK university versus UK capitalist industry.

A concurrent subject was the rise of literary theory, gently skewered in Robyn Penrose, standing for the university side of Nice Work (she is a devotee of "semiotic materialism" who believes there is no such thing as the "self", though "in practice this doesn't seem to affect her very noticeably [so] I shall therefore take the liberty of treating her as a character"). John Mullan, lecturer in English at University College London, who has written, in these pages, that the English campus novel is a fossil form, says "nobody notices, but AS Byatt's Possession [1990] is an extremely acid attack on feminist literary criticism."

So, as the university changed, British campus novels were changing in tone - angry, coruscating, debunking, or, in the case of Michael Frayn's haunting The Trick of It (1989), melancholy; and the younger generation of novelists - Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan - weren't writing them. "It might be that the clutch of books that appeared in the 70s and 80s were to do with the fact that we were about to see a world vanish, maybe they were all elegies to an idea of the campus," says Howard Jacobson. "My novel [Coming From Behind, a "rotten poly" satire published in 1983] came towards the end of it - and was in a way a parody of what was already a parody, since my campus wasn't even a campus."

Jacobson argues that fear of elitism put paid to the campus novel. "Although half the country goes to campuses... everybody is embarrassed to talk about it. I think once democracy got going on the English novel, and we felt we didn't want to write anything that might upset anybody or make them feel out of it, that was the end of the campus novel. I miss it. And also, of course, campus novels were, by their very nature, funny, and funny is not in either. Campuses have become tragic places. Maybe that's all it is. They're pure wastelands, really."

"Universities are depressed," says Byatt. When institutions such as the University of East Anglia were built everything was "shiny, white and new," and because "in those days universities were intensely hopeful" you could afford farce, because "you had a solidity. Now they're terrified and cowering and underfinanced and overexamined and over-bureaucratised."

Not everyone shares this bleak view. Lodge, for one, published a new campus novel, Thinks... in 2001, and says "There's a tendency for people to sneer at the genre as if it's played out, while actually they take a good deal of interest in reading it. The fact is that universities change and societies change, and therefore there are always new fictional possibilities."

Laurie Taylor, who for 27 years has written a satirical column about universities for the Times Higher Education Supplement (and was rumoured to be the model for Howard Kirk in The History Man), concurs. This week he judged a competition for the THES that asked for the first chapter of a new campus novel. The entries were "full of campuses in which management experts and management gurus and development leaders, all speaking management jargon, are locked in a battle with the few people left who still believe that there's something more to universities than providing people with degrees that enable them to get jobs."

For this is the major battle still being fought, first joined under Thatcher, and continued under Blair: "the campus is now a site for a clash between two pretty fundamental values": the instrumental and the intrinsic, auditors versus intellectuals. Taylor cites a novel he recently reviewed, Academia Nuts, by Michael Wilding (2002), "which is very clever, in the grand tradition of Lucky Jim - but all about the impossibility of writing campus novels any more."

' "This", said Henry. "All this." There it was, their world lay all before them. The deserted common room. The chipped cups. The worn, unfigured carpet. "There's not an awful lot here," said Pawley. "I think you need more than the common room." "The university as such," said Henry. "You'd better hurry," said Pawley. "It's all being out-sourced. There's hardly anything left. The virtual university. No tenured staff. No gross moral turpitude." "I shall write about the university in decline," said Henry. "I think you might have left it too late," said Dr Bee.'

So "there are still plenty of laughs," says Taylor, "even though the laughter is now bitter instead of affectionate." But Academia Nuts is also Australian, and it is instructive to look away from England to see how the patient is really faring. Canada had Robertson Davies, now dead, and more recently Jeffrey Moore, who won the Commonwealth Best First Book award with a campus novel, Red-Rose Chain, in 2000; JM Coetzee's fierce, brilliant Disgrace (1999) is set in motion by the narrator's misdemeanors on a campus in Cape Town.

Europe never had very many, though All Souls, by Javier Marias, is "wonderful", says Byatt; in order to write a good campus novel you have to have been a university teacher, says Lodge, and in Europe that would be a betrayal of professional dignity. But in America the genre seems to have grown in stature, mutating into something important, and relevant. The increasing ubiquity of the university education is as true there as it is here (as David Mamet put it in Oleanna, "college education, since the war, has become so much a matter of course, and such a fashionable necessity... that we espouse it as a matter of right, and have ceased to ask 'What is it good for'?") and ensures a large audience less hamstrung than the British by class-consciousness.

The English department continues to provide great fodder (for Richard Russo, for example) but one of the more obvious trends has been the rise of novels satirising creative writing courses, such as Wonder Boys, by Michael Chabon. "It's like shooting fish in a barrel," laughs Francine Prose, whose National Book Award-nominated Blue Angel updates the Marlene Dietrich movie, placing it in a creative writing course in a tiny college in northern Vermont. "The minute they started allowing writers on campus they were in trouble"; of course they were going to start mocking the day job.

"Where is the novel we ought to have, about science departments?" wonders Byatt, who frankly wishes that English departments, wallowing in self-referentiality, could be discontinued; Lodge's Thinks... again of contrapuntal, bipartite structure, plays a novelist teaching a creative writing course off against a cognitive scientist; the usual farcical bed-hopping ensues, but it's a knowing nod to the genre in what is mainly a serious exploration of the nature of consciousness and the limits of AI.

This, too, is a trend established in the US, by writers such as Jonathan Lethem, whose As She Climbed Across the Table is about a physicist who discovers a hole in the universe, and a sociologist who studies academic environments; or by Richard Powers, who in Galatea 2.2 has a cognitive neurologist train a neural net to pass a course on Great Books.

Francine Prose set out to write a novel of obsessive love and ambition, "and somehow the campus seemed the perfect way to talk about those things". This seems a general discovery: White Noise, 20 years old now, is, as well as a study of the threats, and the seductive promises of science, and a celebration of family, a sustained and darkly funny engagement with the idea of death; Donna Tartt's bestseller The Secret History (also a campus thriller) takes the influence tutors have over their nubile charges to violent extremes. Power is so clearly demarcated on campus, and, increasingly, so easy to lose.

The great novel about this - though it is great about nearly everything - is Philip Roth's The Human Stain. Coleman Silk, professor of classics, is also dean when he utters one inadvisable word, "spooks"; the tumbrils of politically correct outrage roll, and he loses his job. (One of the central ironies of the book is that he is African-American, passing as white.) In the controlled space of the campus he has been king, overhauling departments, sweeping them clean, but in a word he has been forced into exile.

Exile is, in the late 20th century, itself almost a fossilised concept: where, centuries ago, you might be forced to leave a village as punishment, how many communities now are close-knit enough to function in this way? The campus, especially highly differentiated, self-sufficient American campuses such as Coleman Silk's in sleepy New England, is our alternative; banishment is no less keenly felt. And it nearly drives Silk mad.

Political correctness never made much headway on British campuses, and in fact, says Alexander Star, who edited Lingua Franca, the magazine of American academia, until it folded three years ago, the worst has been over in the US for a while now. The animating anger of The Human Stain is, therefore, dated. But it doesn't matter. For in pc, and in literary theory, and on a modern campus, Roth found a way to address some of the big cultural questions of the later 20th century.

Silk's nemesis is a young French academic called Delphine, bright, ambitious, a mistress of theory. She is also far from home, and lonely, and increasingly "destabilised to the point of shame by the discrepancy between how she must deal with literature in order to succeed professionally and why she first came to literature": that instrumental v intrinsic argument rearing its head again.

The dichotomy, for Roth, is clear: ideology is the enemy of humanism, of the human; ideology is fascism, communism - is political correctness. And so, in America at least, the campus novel has become a way to measure the state of the nation. It has taken on the elements of classical tragedy, but it is still amusing, albeit often bleakly so. No wonder Tom Wolfe wants to join in the fun.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Una hermosa criatura (A Beautiful Child)

El siguiente texto, transcrito de “Música para camaleones” (Ed. Anagrama), fue escrito por Truman Capote y traducido al español por Benito Gómez Ibáñez.

Fecha: 28 de abril de 1955.

Escenario: La capilla de la Universal Funeral Home en la Avenida Lexington esquina a la Calle Cincuenta y Dos, en la ciudad de Nueva York. Una brillante asamblea se aglomera en los bancos: celebridades en su mayor parte, del campo del teatro internacional, del cine, de la literatura, presentes todos como tributo a Constance Collier, la actriz de origen inglés que había muerto el día anterior a los setenta y cinco años.

Nacida en 1880, miss Collier empezó su carrera como corista de variedades, pasando a convertirse en una de las principales actrices shakespearianas de Inglaterra (y, durante mucho tiempo, en la fiancée de sir Max Beerbhom, con quien nunca se casó y quizá por ese motivo inspirara el personaje de la heroína maliciosamente inconquistable, de la novela Zuleika Dobson, de sir Max). Finalmente, emigró a Estados Unidos, donde se asentó como una respetable figura de la escena de Nueva York, y del cine de Hollywood. Durante las últimas décadas de su ida, vivió en Nueva York dando clases de dramaturgia de una calidad única; como alumnos, sólo admitía a profesionales y, por lo general, consagrados que ya eran "estrellas": Katherine Hepburn era discípula permanente; otra Hepburn, Audrey, también era protegée de Collier, lo mismo que Vivien Leight, y durante unos meses antes de su muerte, una neófita a la que miss Collier se refería como "mi problema especial", Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn Monroe, a quien conocí por medio de John Huston cuando éste la dirigía en su primer papel con diálogo, The Asphalt Jungle, entró bajo la protección de miss Collier por sugerencia mía. Hacía unos seis años que yo conocí a miss Collier, y la admiraba como una mujer de auténtica estatura, física, emocional y creativa, por todos sus modales dominantes, por su gran voz de catedral y por ser una persona adorable, levemente perversa, pero extraordinariamente tierna, digna, pero Germütlich. Me encantaba ir a los frecuentes y pequeños almuerzos que daba en su oscuro estudio Victoriano en pleno Manhattan; contaba historias increíbles acerca de sus aventuras como primera actriz junto a sir Beerbohm Tree y al gran actor francés Coquelin, de sus relaciones con Oscar Wilde, con el joven Chaplin y con Garbo en la época de formación de la silenciosa sueca. Efectivamente, era una delicia, igual que su fie secretaria y compañera, Phyllis Wibourn, una tranquila y parpadeante soltera que tras el fallecimiento de su patrona se convirtió en la dama de compañía de Katherine Hepburn, cosa que sigue siendo. Miss Collier me presentó a muchas personas con las que entablé amistad: los Lunt, los Olivier y, especialmente, Aldous Huxley. Pero fui yo quien le presenté a Marilyn Monroe, y al principio no estuvo muy inclinada a trabar relaciones con ella: era corta de vista, no había visto ninguna película de Marilyn y no sabía absolutamente nada de ella, salvo que era una especie de estallido sexual de color platino que había adquirido fama universal; en resumen, parecía una arcilla difícilmente apropiada para la estricta formación clásica de miss Collier. Pero pensé que harían una combinación estimulante.

La hicieron. “¡Oh, sí!”, me aseguró miss Collier, “hay algo ahí Es una hermosa criatura. No lo digo en el sentido evidente, en el aspecto quizá demasiado evidente. No creo que sea actriz en absoluto, al menos en la acepción tradicional. Lo que ella posee, esa presencia, esa luminosidad, esa inteligencia brillante nunca emergería en el escenario. Es tan frágil y delicada que sólo puede caparlo una cámara. Es como el vuelo de un colibrí: sólo una cámara puede fijar su poesía. Pero el que crea que esta chica es simplemente otra Harlow o una ramera, o cualquier otra cosa, está loco. Hablando de locos, en eso es en lo que estamos trabajando las dos: Ofelia. Creo que la gente se reirá ante esa idea, pero en serio, puede ser una Ofelia exquisita. La semana pasada estaba hablando con Greta y le comenté la Ofelia de Marilyn, y Greta dijo que sí, que podía creerlo porque había visto dos de sus películas, algo muy malo y vulgar, pero, sin embargo, había vislumbrado las posibilidades de Marilyn. En realidad, Greta tiene una idea divertida. ¿Sabe que quiere hacer una película de Dorian Gray? Con ella en el papel de Dorian, por supuesto. Pues dijo que le gustaría tener de antagonista a Marilyn en el papel de una de las chicas a las que Dorian seduce y destruye. ¡Greta! ¡Tan poco utilizada! ¡Semejante talento…!, y algo parecido al de Marilyn, si uno lo piensa. Claro que Greta es una artista consumada, una artista con un dominio sumo. Esa hermosa criatura no tiene concepto alguno de la disciplina o el sacrificio. En cierto modo, no creo que vaya a madurar. Es absurdo que lo diga, pero de alguna manera creo que seguirá siendo joven. Realmente, espero y ruego que viva lo suficiente como para liberar ese extraño y adorable talento que vaga a través de ella como un espíritu enjaulado”.

Pero ahora, miss Collier había muerto. Y ahí estaba yo, remoloneando en el vestíbulo de la Universal Chapel esperando a Marilyn; habíamos hablado por teléfono la noche anterior, quedando de acuerdo para sentarnos juntos durante la ceremonia, cuyo inicio estaba previsto para mediodía. Llegó media hora tarde; siempre llegaba tarde, pero yo pensaba:

¡Por amor de Dios, maldita sea, sólo por una vez! Y, entonces, apareció de pronto y no la reconocí, hasta que dijo…

Marilyn: ¡Oh, cuánto lo siento, chico! Pero, mira, me maquillé toda, y luego pensé que quizá fuese mejor no llevar pestañas postizas, ni maquillaje, ni nada, así que tuve que quitarme todo aquello de encima, y no se me ocurría nada que ponerme…

(Lo que se le ocurrió ponerse habría sido apropiado para la abadesa de un convento en audiencia particular con el Papa. Llevaba el pelo enteramente oculto por un pañuelo de gasa negra; un vestido negro, suelto y largo, que de algún modo parecía prestado; medias negras de seda apagaban e brillo dorado de sus esbeltas piernas. Con toda seguridad, una abadesa no se habría calzado unos zapatos negros de tacón alto tan vagamente eróticos como los que ella había escogido, ni las gafas oscuras en forma de búho que dramatizaban la palidez de vainilla de su piel de leche fresca).

Truman Capote: Tienes un aspecto estupendo.

Marilyn (mordisqueándose una uña roída ya hasta el final): ¿Estás seguro? Es que estoy tan nerviosa. ¿Dónde está el lavabo? Si pudiera entrar ahí nada más que un minuto…

TC: ¿Y meterte una pastilla? ¡No! Chsss. Esa es la voz de Cyril Ritchard: ha empezado al panegírico.

(De puntillas, entramos en la atestada capilla y nos abrimos paso hasta un pequeño espacio en la última fila. Acabó Cyril Ritchard; lo siguió Cathleen Nesbitt, una compañera de miss Collier de toda la vida, y, finamente, Brian Aherne se dirigió a los asistentes al funeral. A lo largo de todo ello, mi acompañante se quitaba periódicamente las gafas para enjugar lágrimas que se desbordaban de sus ojos azulgrises. En ocasiones la había visto sin maquillaje, pero hoy ofrecía una nueva experiencia visual, un rostro que yo no había observado antes, y al principio no me di cuenta de qué podría ser. ¡Ah! Se debía al sombrío pañuelo de la cabeza. Con los bucles invisibles y e cutis limpio de cosméticos, parecía tener doce años: una virgen pubescente que acaba de entrar en un orfanato y está llorando su desgracia. La ceremonia terminó al fin, y la reunión comenzó a dispersarse).

MM: Quedémonos aquí sentados, por favor. Esperemos a que salga todo el mundo.

TC: ¿Por qué?

Marilyn: No quiero tener que hablar con nadie. Nunca sé qué decir.

TC: Entonces, quédate ahí sentado, y yo esperaré fuera. Tengo que fumar un pitillo.

Marilyn: ¡No puedes dejarme sola! ¡Dios mío! Fuma aquí.

TC: ¿Aquí? ¿En la capilla?

Marilyn: ¿Por qué no? ¿Qué te quieres fumar? ¿Un petardo?

TC: Muy gracioso. Venga, vámonos.

Marilyn: Por favor. Hay un montón de fotógrafos ahí abajo. Y, desde luego, no quiero que me tomen fotografías con esta facha.

TC: No te lo reprocho.

Marilyn: Has dicho que tenía un aspecto estupendo.

TC: Y lo tienes. Sencillamente, perfecto…, si estuvieras interpretando La novia de Drácula.

Marilyn: Ya te estás riendo de mí.

TC: ¿Tengo yo pinta de reírme?

Marilyn: Te estás riendo por dentro. Y ésa es la peor clase de risa. (Frunciendo el ceño; mordisqueándose la uña del pulgar). En realidad, podría haber llevado maquillaje. Veo que toda esa otra gente lleva maquillaje.

TC: Yo sí. Gotitas.

Marilyn: Lo digo en serio. Es el pelo. Necesito un tinte. Y no he tenido tiempo de dármelo. Todo ha sido tan inesperado, la muerte de miss Collier y demás. ¿Ves?

(Levantó un poco el pañuelo, mostrando una franja oscura en la raya del pelo).

TC: Pobre inocente de mí. Y todo este tiempo pensando que eras rubia natura.

Marilyn: Lo soy. Pero nadie es así de natural. Y, de paso, que te follen.

TC: Muy bien, ya ha salido todo el mundo. Así que vamos, arriba.

Marilyn: Esos fotógrafos siguen ahí abajo. Lo sé.

TC: Si no te han reconocido al entrar, tampoco te conocerán al salir.

Marilyn: Uno de ellos me reconoció. Pero me escabullí por la puerta antes de que empezara a chilar.

TC: Estoy seguro de que hay una entrada trasera. Podemos ir por ahí.

Marilyn: No quiero ver cadáveres.

TC: ¿Por qué habríamos de verlos?

Marilyn: Esta es una funeraria. Deben tenerlos en alguna parte. Lo único que me faltaba hoy, aparecer en una habitación llena de cadáveres. Ten paciencia. Iremos a algún sitio y te invitaré a una botella de champaña.

(Así que nos sentamos y hablamos y Marilyn dijo: “Odio los funerales. Me alegro de no tener que ir al mío. Pero no quiero ceremonias, tan sólo mis cenizas arrojadas al agua por uno de mis hijos, si alguna vez tengo alguno. No habría venido hoy a no ser porque miss Collier se preocupaba de mí, de mi bienestar, y era como una abuela, como una abuela vieja y dura, pero me enseño mucho. Me enseñó a respirar. Hice buen uso de ello, además, y no me refiero sólo a actuar. Hay otras veces que respirar es un problema. Pero cuando me dijeron que miss Collier se había muerto, lo primero que se me ocurrió fue: ¡Oh, Dios mío, qué va a ser de Phyllis! Miss Collier era toda su vida. Pero he oído que se va a vivir con miss Hepburn. Qué suerte la de Phyllis; ahora sí que se va a divertir. Me cambiaría por ella sin pensarlo. Miss Hepburn es realmente una gran señora. Ojalá fuera amiga mía. De ese modo iría a visitarla alguna vez y… pues no sé, nada más que visitarla”.

Comentamos cuánto nos gustaba vivir en Nueva York y cómo detestábamos Los Angeles (“A pesar de que nací allí, sigue sin ocurrírseme nada bueno de ella. Si cierro los ojos y me imagino Los Angeles, lo único que veo es una enorme vena varicosa”); hablamos de actores y de actuación (“Todo el mundo dice que no sé actuar. Lo mismo dijeron de Elizabeth Taylor, y se equivocaron. Estuvo extraordinaria en Un lugar en el sol. Nunca conseguiré el papel adecuado, nada que realmente quiera. Mi físico está contra mí”); hablamos algo más de Elizabeth Taylor, quería saber si yo la conocía, y dije que sí, y ella me preguntó cómo era, cómo era en realidad, y yo contesté, pues se parece un poco a ti, es enteramente sincera y tiene una conversación ingeniosa, y Marilyn dijo que te follen, y añadió, bueno, si alguien te preguntara cómo es Marilyn, cómo es en realidad, ¿Qué le dirías?, y yo contesté que tendría que prensarlo.

TC: ¿Crees que ya podemos largarnos de aquí? Me prometiste champaña, ¿recuerdas?

Marilyn: Lo recuerdo, pero no tengo nada de dinero.

TC: Siempre llegas tarde y nunca llevas dinero. ¿Es que por casualidad te figuras que eres la reina Isabel?

Marilyn: ¿Quién?

TC: La reina Isabel. La reina de Inglaterra.

Marilyn (frunciendo el ceño): ¿Qué tiene esa gilipollas que ver con esto?

TC: La reina Isabel tampoco lleva dinero nunca. No se lo permiten. El vil metal no debe manchar la real palma de su mano. Es una ley o algo parecido.

Marilyn: Ojalá aprobaran una ley como esa para mí.

TC: Sigue así y quizá lo hagan.

Marilyn: ¡Por Dios! ¿Cómo paga las cosas? Cuando va de compras, por ejemplo.

TC: Su dama de compañía la sigue con un bolso lleno de monedas de un cuarto de penique.

Marilyn: ¿Sabes una cosa? Apuesto a que todo selo dan gratis. A cambio de avales.

TC: Es muy posible. No me sorprendería nada. Por Decreto de Su Majestad. Perros galeses. Todas esas golosinas de Fortnum & Mason. Hierba. Condones.

Marilyn: ¿Para qué querría ella condones?

TC: Ella no, boba. Para ese tipo que la sigue a dos pasos. El príncipe Felipe.

Marilyn: Ah, sí. Ese. Es un encanto. Tiene aspecto de tener un buen nabo. ¿Te conté alguna vez lo de aquella ocasión en que vi a Errol Flynn sacarse la picha de repente y empezar a tocar el piano con ella? ¡Oh, vaya! Ya hace cien años de eso, yo acababa de empezar como modelo, fui a esa estúpida fiesta y ahí estaba Errol Flynn, tan orgulloso de sí mismo, se sacó a picha y tocó en el piano con ella. Aporreó las teclas. Tocó You are my sunshine. ¡Cristo! Todo el mundo dice que Milton Berle tiene el chisme más grande de Hollywood. Pero ¿a quién le importa? Oye ¿no tienes nada de dinero?

TC: Unos cincuenta pavos, quizá.

Marilyn: Bueno, eso nos llega para pedir algo de champaña.

(Fuera, la avenida Lexington estaba vacía de todo, excepto de inofensivos peatones. Eran cerca de las dos, una tarde de abril tan espléndida como uno podría desear: un tiempo ideal para dar un paseo. De modo que deambulamos hacia la Tercera Avenida. Algunos transeúntes volvían la cabeza, no porque reconociesen a Marilyn, sino por sus galas de luto; se rió entre dientes con su risita particular, un sonido tan tentador como el cascabeleo de las campanillas en el Tren de la Risa, y dijo: “Quizá debería vestirme siempre de esta manera. Es enteramente anónima”.

Al acercarnos al local de P.J., sugerí que ése sería un buen sitio para refrescarnos, pero ella lo vetó: “Esta lleno de esos gacetilleros repugnantes. Y esa zorra de Dorothy Kilgallen siempre está ahí, entrompándose. ¿Qué les pasa a esos irlandeses? Esa manera en que beben; son peor que indios”.

Me sentí llamado a defender a Dorothy Kilgallen, quien, en cierto modo, era una amiga, y me permití decir que en ocasiones podía resultar una mujer inteligente y divertida. Ella dijo: “Sea como sea, ha escrito algunas cosas puñeteras de mí. Pero todas esas gilipollas me odian. Hedda. Louella. Comprendo que tú estés acostumbrado, pero sencillamente yo no puedo. Me hace mucho daño. ¿Qué es lo que les he hecho yo a esas brujas? El único que ha escrito una palabra decente acerca de mí es Sidney Skolski. Pero es un chico. Los chicos me tratan muy bien. Como si fuese una persona humana. Cuando menos, me conceden el beneficio de la duda. Y Bob Thomas es un caballero. Y Jack O’Brian”.

Miramos los escaparates de tiendas de antigüedades; uno de ellos contenía una bandea de anillos antiguos, y Marilyn dijo: “Ese es bonito. El granate con las perlas deterioradas. Ojalá pudiera llevar sortijas, pero detesto que la gente me mire las manos. Son demasiado gruesas. Elizabeth Taylor tiene manos gruesas. Pero con esos ojos, ¿quién va a fijarse en sus manos? Me gusta bailar desnuda delante del espejo y ver cómo me brincan las tetas. No tienen nada de malo. Pero me gustaría no tener las manos tan gordas”.

Otro escaparate exhibía un bello reloj antiguo, lo que le impulsó a observar: “Jamás he tenido un hogar. Uno auténtico, con mis propios muebles. Pero si alguna vez vuelvo a casarme y gano mucho dinero, alquilaré un par de camiones para pasar por la Tercera Avenida y comprar toda clase de cosas locas. Compraré una docena de relojes antiguos, los pondré en fila en una habitación y los tendré a todos marcando la misma hora. Eso resultaría muy hogareño, ¿no crees?).

Marilyn: ¡Eh! ¡En la acera de enfrente!

TC: ¿Qué?

Marilyn: ¿Ves el cartel con la palma de la mano? Dee ser el consultorio de una adivina.

TC: ¿Estás con ánimo para esas cosas?

Marilyn: Bueno, vamos a echar un vistazo.

(No era un establecimiento atrayente. A través de una tiznada ventana, distinguimos una yerma habitación con una gitana flaca y peluda sentada en una silla de lona bajo una lámpara de techo que castigaba con su duro resplandor; tejía un par de botitas de niño, y no nos devolvió la mirada. Sin embargo, Marilyn empezó a entrar y luego cambió de parecer).

Marilyn: A veces quiero saber lo que va a pasar. Luego pienso que sería mejor no saberlo. Pero hay dos cosas que me gustaría saber. Una es si voy a perder peso.

TC: ¿Y la otra?

Marilyn: Es un secreto.

TC: Vamos, vamos. Hoy no podemos tener secretos. Hoy es un día de dolor, y los afligidos comparten sus pensamientos más íntimos.

Marilyn: Bueno, se trata de un hombre. Hay algo que me gustaría saber. Pero eso es todo lo que voy a decirte. Es un secreto, de verdad.

(Y yo pensé: eso es lo que tú crees; yo te lo sacaré).

TC: Estoy preparado para beber esa champaña.

(Terminamos en un restaurante chino de la Segunda Avenida, desierto y con muchos adornos. Pero tenía un bar bien provisto, y pedimos una botella de Mumm’s; nos los sirvieron sin enfriar y sin cubo, así que nos lo bebimos en vasos largos con hielo).

Marilyn: Es divertido esto. Como rodar exteriores, si es que a uno le gustan los exteriores. Cosa que desde luego a mí no me gusta nada. Niágara. ¡Qué asco! ¡Uf!

TC: Así que cuéntame lo de ese amante secreto.

Marilyn: (Silencio).

TC: (Silencio).

Marilyn: (Risitas).

TC: (Silencio).

Marilyn: Tú conoces a muchas mujeres. ¿Cuál es la más atractiva que conoces?

TC: Bárbara Paley, sin duda. Indiscutiblemente.

Marilyn (frunciendo el ceño): ¿Es ésa a la que llaman “Niña”? Desde luego, a mí no me parece que tenga nada de aspecto infantil. La he visto en Vogue y demás. Es tan elegante. Encantadora. Sólo con mirar fotografías de ella me siento como basura de cerdo.

TC: A ella le divertiría oír eso. Está muy celosa de ti.

Marilyn: ¿Celosa de mí? Ya estás otra vez tomándome el pelo.

TC: Nada de eso. Está celosa.

Marilyn: Pero ¿por qué?

TC: Porque una articulista, Kilgallen, creo, lanzó una noticia a ciegas que decía algo así: “Corre el rumor de que la señora DiMaggio se reúne con el más encumbrado magnate de la televisión, y no para hablar de negocios.” Bueno, ella leyó el artículo, y se lo creyó.

Marilyn: ¿Qué se creyó?

TC: Que su marido tiene un asunto contigo. William S. Pale, el principal magnate de la televisión. Es aficionado a las rubias bien formadas. Y también a las morenas.

Marilyn: Pero eso es estúpido. No conozco a ese tipo.

TC: ¡Ah, vamos! Puedes sincerarte conmigo. Ese amante secreto tuyo… es William S. Paley, n’est-ce-pas?

Marilyn: ¡No! Es un escritor. Es un escritor.

TC: Eso está mejor. Ya vamos a alguna parte. Así que tu amante es un escritor. Debe ser un auténtico ganapán, si no, no te daría vergüenza decirme cómo se llama.

Marilyn (furiosa, frenética): ¿Qué representa la “S”?

TC: ¡”S”! ¿Qué “S”?

Marilyn: La “S” de William S. Paley.

TC: ¡Ah! Esa “S”. No ceo que represente nada. La ha debido poner ahí por las apariencias.

Marilyn: ¿Es sólo una inicial que no representa ningún nombre? ¡Dios mio! Míster Paey debe encontrarse algo inseguro.

TC: Tiene muchos tics. Pero volvamos a nuestro misterioso escriba.

Marilyn: ¡Cállate! Tengo mucho que perder.

TC: Camarero, tomaremos otra Mumm’s, por favor.

Marilyn: ¿Estás tratando de tirarme la lengua?

TC: Sí. Te propongo una cosa. Haremos un trato. Yo te contaré una historia y, si la encuentras interesante, quizá podamos hablar luego de tu amigo escritor.

Marilyn (tentada, pero reacia): ¿De qué trata tu historia?

TC: De Errol Flynn.

Marilyn: (Silencio).

TC: (Sielncio).

Marilyn (odiándose a sí misma): Vale, empieza.

TC: ¿Recuerdas lo que has dicho de Errol? ¿Lo orgulloso que estaba de su picha? Puedo garantizarlo. Una vez pasamos una agradable noche juntos. ¿Me comprendas?

Marilyn: Te lo estás inventando. Me quieres engañar.

TC: Palabra de explorador. Estoy haciendo un trato limpio. (Silencio; pero veo que ha picado, así que, tras encender un pitillo…). Pues eso ocurrió cuando yo tenía dieciocho años. Diecinueve. Fue durante la guerra. En el invierno de 1943. Aquella noche, Carol Marcus, o quizá se había convertido ya en Carol Saroyan, dio una fiesta para su mejor amiga, Gloria Vanerbilt. La celebró en el piso de su madre, en Park Avenue. Una gran fiesta. Unas cincuenta personas. A eso de medianoche se presentó Errol Flynn con su amigo de confianza, un mujeriego fanfarrón llamado Freddie McEvoy. Los dos estaban bastante borrachos. A pesar de eso, Errol empezó a charlar conmigo y estuvo divertido, nos hicimos reír el uno al otr; de pronto dijo que quería ir a El Morocco, y que yo fuera con él y con su amigo McEvoy. Le dije que muy bien, pero McEvoy dijo entonces que él no quería dejar la fiesta con todas aquellas principiantes, así que Errol y yo terminamos yéndonos solos. Pero no fuimos a El Morocco. Tomamos un taxi hasta Gramercy Park, donde yo tenía un pequeño piso de una habitación. Se quedó hasta el mediodía siguiente.

Marilyn: ¿Y qué puntuación le darías? En una escala de uno a diez.

TC: Francamente, si no hubiera sido Errol Flynn, no creo que lo hubiese recordado.

Marilyn: No es una historia maravillosa. No vale lo que la mía; ni por asomo.

TC: Camarero, ¿dónde está nuestro champaña? Tiene usted sedientas a dos personas.

Marilyn: Y no me has contado nada nuevo. Siempre he sabido que Errol alternaba. Mi masajista, que prácticamente es como una hermana, atendía a Tyrone Power, y él me ha contado el asunto que se traían Errol y Ty. No, tendrá que ser algo mejor que eso.

TC: Me lo pones difícil.

Marilyn: Te escucho. Así que oigamos tu mejor experiencia. En ese aspecto.

TC: ¿La mejor? ¿La más memorable? Suponte que contestas tú primero a esa pegunta.

Marilyn: ¡Y soy yo quien lo pone difícil! ¡Ja! (Bebiendo champaña). Lo de Joe no está mal. Podía llegar al tope. Si sólo se tratara de eso, aún seguiríamos casados. Sin embargo, todavía lo quiero. Es auténtico.

TC: Los maridos no cuentan. En este juego, no.

Marilyn (mordiéndose las uñas; pensando en serio): Bueno, conocí a un hombre que está emparentado de alguna manera con Gary Cooper. Un corredor de bolsa, sin ningún atractivo a la vista; tiene sesenta y cinco años y lleva unas gafas de cristales muy gruesos. Gordo como una medusa. No puedo decir qué era, pero…

TC: Puedes parar ahí mismo. Otras chicas me han contado todo acerca de él. Ese viejo verde tiene mucha cuerda. Se llama Paul Shields. Es padrastro de Rocky Cooper. Dicen que es sensacional.

Marilyn: Lo es. Muy bien, listo. Te toca a ti.

TC: Olvídalo. No tengo que contarte absolutamente nada. Porque sé cuál es la maravilla que ocultas. Arthur Miller. (Bajó sus gafas oscuras: ¡cielos!, si las miradas mataran, ¡uf!). Lo adiviné en cuanto dijiste que era escritor.

Marilyn (balbuceando): Pero ¿cómo? Quiero decir, nadie…, quiero decir, casi nadie…

TC: Hace tres años, por lo menos, quizá cuatro, Irving Drutman…

Marilyn: ¿Irving qué?

TC: Drutman. Es un redactor del Herald Tribune. Me contó que andabas tonteando con Arthur Miller. Que estabas colada por él. Soy demasiado caballero para haberlo mencionado.

Marilyn: ¡Caballero! ¡Un bastardo! (Balbuceando de nuevo, pero con las gafas oscuras en su sitio). No lo entiendes. Eso fue hace tiempo. Aquello terminó. Pero esto es nuevo. Ahora todo es distinto, y…

TC: Que no se te olvide invitarme a la boda.

Marilyn: Si hablas de esto, te mato. Haré que te liquiden. Conozco a un par de tipos que me harían gustosos ese favor.

TC: No lo pongo en duda ni por un momento.

(Por fin volvió el camarero con la segunda botella).

Marilyn: Dile que se la vuelva a llevar. No quiero más. Quiero largarme de aquí.

TC: Si te he hecho enfadar, lo siento.

Marilyn: No estoy enfadada.

(Pero lo estaba. Mientras yo pagaba la cuenta, se fue al tocador, y deseé tener un libro para leer: sus visitas al lavabo de señoras a veces duraban tanto como el embarazo de una elefanta. Mientras pasaba el tiempo, me pregunté tontamente si se estaría metiendo estimulantes o tranquilizantes. Tranquilizantes, sin duda. Había un periódico encima de la barra y lo cogí; estaba escrito en chino. Cuando pasaron veinte minutos, decidí investigar. Quizá se había metido una dosis mortal, o a lo mejor se había cortado las muñecas. Encontré el lavabo de señoras, y llamé a la puerta. Ella dijo: “Pase”. Dentro, se estaba observando en un espejo mal iluminado. Le dije: “¿Qué estás haciendo?”. Contestó: “Mirándola a ella”. En efecto, se estaba pintando los labios con lápiz de color rubí. Además, se había quitado el sombrío pañuelo de la cabeza y se había peinado su lustroso pelo, fino como algodón de azúcar).

Marilyn: Espero que te quede suficiente dinero.

TC: Eso depende. No lo bastante como para comprar perlas, si ésa es tu idea de enmendar las cosas.

Marilyn (con risitas, otra vez de buen humor. Decidí no volver a mencionar a Arthur Miller): No. Sólo lo bastante para un largo paseo en taxi.

TC: ¿A dónde vamos? ¿A Hollywood?

Marilyn: ¡No, demonios! A un sitio que me gusta. Lo averiguarás cuando lleguemos.

(No tuve que esperar tanto, porque nada más parar un taxi dio órdenes al conductor para que se dirigiese al muelle de South Street, y pensé: ¿no es ahí donde se toma el transbordador para Staten Island? Y mi siguiente conjetura fue: se ha tragado pastillas encima del champaña y ha perdido la chaveta).

TC: Espero que no vayamos a dar un paseo en barca. No he recogido mi Dramamine.

Marilyn (contenta, riéndose): Sólo por el muelle.

TC: ¿Puedo preguntar por qué?

Marilyn: Me gusta estar allí. Huele a algo remoto y doy de comer a las gaviotas.

TC: ¿Con qué? No tienes nada que darles de comer.

Marilyn: Si tengo. Mi bolso está lleno de pastelitos de la suerte. Los he robado del restaurante.

TC (tomándose el pelo): ¡Vaya! Cundo estabas en el lavabo abrí uno. El envoltorio de dentro era un chiste verde.

Marilyn: ¡Vaya! ¿Pastelitos de la suerte verde?

TC: Estoy seguro de que a las gaviotas no les importará.

(Nuestro camino nos llevó por el Bowery. Diminutas casas de empeño y puestos de donar sangre y pensiones de cincuenta centavos el catre y pequeños hoteles sombríos de un dólar la cama y bares para blancos, bares para negros, en todas partes mendigos, pedigüeños jóvenes, nada jóvenes, ancianos, vagabundos en cuclillas al borde de la acera, agachados entre vidrios otros y restos de vómito, pordioseros reclinados en portales y apelotonados como pingüinos en las esquinas. Una vez, al detenernos ante un semáforo rojo, un espantapájaros de purpúrea nariz se acercó hacia nosotros dando traspiés y empezó a restregar el parabrisas del taxi con un trapo húmedo, sujeto con mano temblorosa. Nuestro conductor, protestando, gritó obscenidades en italiano).

Marilyn: ¿Qué pasa? ¿Qué ocurre?

TC: Quiere una propina por limpiar la ventanilla.

Marilyn (tapándose la cara con el bolso): ¡Qué horror! No lo puedo soportar. Dale algo. De prisa. ¡Por favor!

(Pero el taxi se alejó zumbando, derribando casi al viejo borrachín. Marilyn se echó a llorar).

Marilyn: Me he puesto mala.

TC: ¿Quieres irte a casa?

Marilyn: Todo se ha estropeado.

TC: Te llevaré a casa.

Marilyn: Espera un minuto. Me pondré bien.

(Así llegamos a South Street, y efectivamente la visión de un transbordador ahí anclado, con la silueta de Brooklyn al otro lado del agua y blancas gaviotas en picado, haciendo cabriolas contra un horizonte marino salpicado de leves y algodonosas nubes como encajes delicados, ese cuadro, tranquilizó pronto su espíritu.

Al bajarnos del taxi vimos a un hombre con un chow llevado de una correa, un posible pasajero en dirección al transbordador y, cuando nos cruzamos con ellos, mi acompañante se agachó para acariciar la cabeza del perro).

El hombre (con tono firme, pero no hostil): No debería tocar a perros desconocidos. Especialmente a los chow. Podrían morderla.

Marilyn: Los perros no me muerden. Sólo los seres humanos. ¿Cómo se llama?

El hombre: Fu Manchú.

Marilyn (riendo): ¡Oh! Como en las películas. Tiene gracia.

El hombre: ¿Cuál es el suyo?

Marilyn: ¿Mi nombre? Marilyn.

El hombre: Lo que me figuraba. Mi mujer nunca me creerá. ¿Podría darme su autógrafo?

(Sacó una tarjeta y una pluma, utilizando el bolso como apoyo, escribió: “Dios lo bendiga. Marilyn Monroe”).

Marilyn: Gracias.

El hombre: Gracias a usted. Ya verá cuando lo enseñe en la oficina.

(Llegamos a la orilla del muelle, y escuchamos el chapoteo de agua contra él).

Marilyn: Yo solía pedir autógrafos. A veces lo hago todavía. El año pasado, Clark Gable estaba sentado junto a mí en Chasen’s y le pedí que me firmara la servilleta.

(Apoyada en un poste de amarre, ofrecía el perfil: Galatea inspeccionando lejanías inconquistadas. La brisa le acariciaba el pelo, y su cabeza se volvió hacia mí con etérea suavidad, como si el aire la hubiera hecho girar).

TC: Pero ¿cuándo damos de comer a los pájaros? Yo también tengo hambre. Es tarde y no hemos almorzado.

Marilyn: Recuerdas que te dije que si alguien te preguntaba cómo era verdaderamente Marilyn Monroe…, bueno, ¿qué le contestarías? (Su tono era inoportuno, burlón, pero también grave: quería una respuesta sincera). Apuesto a que dirías que soy una estúpida. Una sentimental.

TC: Por supuesto. Pero también diría…

(La luz se iba. Marilyn parecía esfumarse con ella, mezclarse con el cielo y las nubes y alejase más allá de ellos. Quería elevar mi voz más alto que los chillidos de las gaviotas y llamarla para que volviese: ¡Marilyn! ¿Por qué todo tuvo que acabar así, Marilyn? ¿Por qué la vida tiene que ser tan jodidamente podrida?).

TC: Diría…

Marilyn: No te oigo.

TC: Diría que eres una hermosa criatura.

#marilyn monroe#truman capote#a beautiful child#una hermosa criatura#literatura#relato#cronica#cine#pop

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On another small table stood Zuleika's library. Both books were in covers of dull gold."

Max Beerbohm, Zuleika Dobson

0 notes