#in a long history of library censorship struggles

Text

Mike Hixenbaugh at NBC News:

METROPOLIS, Ill. — The pastor began his sermon with a warning.

Satan was winning territory across America, and now he was coming for their small town on the banks of the Ohio River in southern Illinois.

“Evil is moving and motivated,” Brian Anderson told his congregation at Eastland Life Church on the evening of Jan. 13. “And the church is asleep.”

But there was still time to fight back, Anderson said. He called on the God-fearing people of Metropolis to meet the enemy where Satan was planning his assault: at their town’s library.

A public meeting was scheduled there that Tuesday, and Christians needed to make their voices heard. Otherwise, Anderson said, the library would soon resemble a scene “straight out of Sodom and Gomorrah.”

The pastor’s call to action three months ago helped ignite a bitter fight that some locals have described as “a battle for the soul” of Metropolis.

The dispute has pitted the city’s mayor, a member of Eastland Life Church, against his own library board of trustees. It led to the abrupt dismissal of the library director, who accused the board of punishing her for her faith. And last month, it drew scrutiny from the state’s Democratic secretary of state, who said the events in Metropolis “should frighten and insult all Americans who believe in the freedom of speech and in our democracy.”

Similar conflicts have rocked towns and suburbs across the country, as some conservatives — convinced that Democrats want to "sexualize" and indoctrinate children — have sought to purge libraries of books featuring LGBTQ characters and storylines. Republican state legislatures have taken up a wave of bills making it easier to remove books and threatening librarians with criminal charges if they allow minors to access titles that include depictions of sex.

To counter this movement, Illinois Democrats last year adopted the first state law in the nation aimed at preventing book bans— which ended up feeding the unrest in Metropolis. Under the law, public libraries can receive state grant funding only if they adhere to the Library Bill of Rights, a set of policies long promoted by the American Library Association to prevent censorship.

Many longtime residents were stunned when these national fissures erupted in Metropolis, a quirky, conservative city of about 6,000 people that has a reputation for welcoming outsiders.

Because of its shared name with the fictional city from DC Comics, Metropolis has for the past half century marketed itself as “Superman's hometown.” Tens of thousands of tourists stop off Interstate 24 each year to pose beneath a 15-foot Superman statue at the center of town, to attend the summertime Superman Celebration, or to browse one of the world’s largest collections of Superman paraphernalia at the Super Museum.

“Where heroes and history meet on the shores of the majestic Ohio River,” the visitor’s bureau beckons, “Metropolis offers the best small-town America has to offer.”

But lately, the pages of the Metropolis Planet — yes, even the masthead of the local newspaper pays homage to Clark Kent — have been filled with strife.

Unlike in comic books and the Bible, the fight in Metropolis doesn’t break along simple ideological lines. Virtually everyone on either side of the conflict identifies as a Christian, and most folks here vote Republican. The real divide is between residents who believe the public library should adhere to their personal religious convictions, and those who argue that it should instead reflect a wide range of ideas and identities.

During his sermon in January and in the months since, Anderson has cast his congregation and their God as righteous defenders of Metropolis — and the Library Bill of Rights and its supporters as forces of evil.

If Christians didn’t take a stand, Anderson warned, there would soon be an entire children’s section at the library “dedicated to sexual immorality and perversion.” And before long, he said, the town would be hosting “story hour with some guy that thinks he’s a girl.”

[...]

A week later, the board went into a closed session and presented Baxter with an ultimatum: If she wanted to keep her job, she needed to sign a performance improvement plan. It stipulated that she would abide by the Library Bill of Rights, seek state grant funding and discontinue praying aloud with children and other religious activities at the library.

Baxter refused to sign and began to criticize the board. Voices were raised, according to three members.

After a few minutes, James, the board president, slammed her fist on the table.

“This is not up for debate, Rosemary,” she said. “Either sign it, or don’t.”

Baxter stood up and left.

Minutes later, the board came out of closed session.

By a vote of 5-3, they terminated Baxter’s employment.

Baxter’s departure left the library in turmoil. Four employees resigned soon after, and the board got to work picking up the pieces.

They brought on a former library employee to serve as interim director and embarked on top-to-bottom reviews of the library’s catalog and finances.

“Our focus,” James said, “is making sure our library is strong and healthy and there to serve everyone.”

Then, on March 19, the story of Baxter’s firing was picked up by Blaze Media, a national conservative outlet. In a column titled, “A librarian’s faithful service is silenced by a secularist takeover,” conservative talk radio host Steve Deace interviewed Baxter and Anderson and reported that both had come under fire for their Christian beliefs.

Deace presented the local saga as a warning that evil forces were now coming for small-town America and blamed the problems in Metropolis, in part, on “a California transplant who is living with another man,” referring to Loverin, the library board member.

Three days later, Metropolis Mayor Don Canada — who in 2021 had appointed Anderson, his pastor, to an open seat on the City Council — took a stand of his own.

In letters addressed to James and two other board members, Canada announced that he’d “lost faith in the Board in its current state.” As a result, he was removing James and two others who’d voted to terminate Baxter.

In Superman's alleged hometown of Metropolis, Illinois, the town has been engulfed with strife over conflicts on the direction of the town's public library, with Eastland Life Church Pastor Brian Anderson leading a war against the library as part of the faux moral panic about LGBTQ+ books that right-wingers falsely claim such books "sexualize" children.

#Metropolis Illinois#Illinois#Libraries#Book Bans#Book Banning#Public Libraries#Anti LGBTQ+ Extremism#Eastland Life Church#Brian Anderson#Alexi Giannoulias#Illinois HB2789#American Library Association#Metropolis Public Library#Rhonda James#Rosemary Baxter#Library Bill of Rights#Culture Wars#Steve Deace#Don Canada#Library Boards

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

i talked to my friend who is a librarian in florida recently, & she is having a very bad time for a lot of reasons but one of the main ones is that everyone who works in her library system is under some level of pressure to avoid right-wing political repercussions against the library, so they're doing a lot of self-censorship in a culture of fear, and the stress has made managers who are more disengaged from daily work, less supportive of their staff, and less able to articulate any organizing vision for the library. it's very bad. she was like "i always assumed that there would be libraries for as long as i was willing to work in them, but now i'm worried that the field will be done with me before i'm done with it," and i struggled with this, at least as much as i sympathized with it! i struggled with it, because i have been freaking the fuck out about the revanchist turn against libraries since 2020, when it began to be clear what was coming: as a field, we aren't organized and we don't have a robust defense; while most librarians are broadly attached to the idea of intellectual freedom, many of them have little idea about its contents or the nature of the attacks on it, so we can't even articulate the problem clearly or consistently; our commitment to an outmoded idea of political neutrality no longer serves, if it ever did. but it's also hard to see a way out of it, and i often feel very bleak about the present and future of the public library, especially youth services. it's hard not to feel bleak. and my friend said that to me, that she felt this despair, maybe not for all of human history, but for our present moment. i share that despair, to be honest; it's hard not to, when you're looking around and the ascendant political vision is genocide, nationalism, exploitation, even the bare shreds of social support stripped away. and the only thing i could think of was a post on here i read years ago, about how little hope the bolsheviks had; they expected to lose, they expected to die, but they tried anyway. and they won! & obviously i am not holding up the entirety of soviet history as some kind of shining light to the world, okay, i don't want to argue about it, but i was moved by the idea that a social order which had been rigidly oppressive for a millennium cracked, and the reminder that the people inside that moment, making that change, couldn't see the path forward either, even though we know a way did open. i feel the same way thinking about the french and haitian revolutions. it must have seemed impossible then too.

#is this just a post against teleology? is the only hope for the future a historiographical turn? surely not#wish i could find the post i would just rb that lol but op deactivated years ago#if you would like to argue with me that librarians are actually all excellent defenders of intellectual freedom you must have evidence#because that has not been my experience at all. a lot of those commitments shred the moment there is pushback.#irredeemable whining

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Documenting Travesties: War & The Arts

Erasure of culture is the most devastating tragedy of war, and yet, so overlooked. It is to take away the manifestation of art and the sole purpose of human expression, which promotes creativity, celebrates individuality and growth. This is now seen before our eyes in the 21st century, as Russian soldiers invaded Ukraine and sowed destruction along their path. They are colonizers, establishing their control over Ukraine when it was not asked for, forcibly scrubbing away the unique identity of Ukrainians to replace it with their own.

The arts is an unappreciated aspect of preserving knowledge and tradition, to the public eye. It is something who's importance is only displayed in museums. But when you think of the Nazis, and how they collected precious artifacts by looting the places they conquered, standing with pride as they show off their assortment of stolen goods, you start to learn that the arts is the seeds of hope for the future, which needs to be cultivated and cared for. Humans are naturally social, who have survived for so long due to their intrinsic friendly behavior. To eradicate a country of it's culture, it's traditions and customs, is a cruel, heartless act. It is to seep the color out of a vibrant canvas, to dull and muddy the waters of a crystalline pond.

But knowledge, which is vital to human survival, is never overlooked by those who wish to burn it. In the Information Age, which is now, authors and librarians battle censorship and the puritan movement to prohibit works which they deem unpalatable to modern society. These include historical works which detail stories about the cruelty and abuse people of color have faced for centuries, erotic literature, and queer fiction, because all this they cannot stand, and cannot understand.

Colonizers, in truth, hate to read or listen to different perspectives. Whatever strays from their morals, and personal beliefs, they disagree with. More than disagree, but they make it a goal to completely suppress any kind of work that promotes thinking and creativity.

Here are only a few of the photos documenting the Russian tactic of destroying and erasing Ukrainian culture, by targeting books. Books, which contain valuable knowledge, information, and promote creativity and emotion.

During March 24, a Ukrainian outlet reported of Russian troops confiscating historical texts and Ukrainian literature. What they are most after are of books about Ukrainian Maidans, history books containing descriptions of the struggles of Ukrainian liberation. The "extremist" literature which the Russians have declared a threat to Russia also includes school textbooks used by schoolchildren to study, about the history of their own country, Ukraine. This is an effective method of imperialism, and has proved itself useful to the eradication of a nation's rich culture and history.

Proof of the brutal attacks of Russian troops on the identity of Ukrainians is also widely recorded, due to technology.

In Chernihiv, a library in ruin was photographed, and uploaded to Twitter.

This is the library of Chernihiv after being shelled by Russian soldiers. It is clear evidence that the war in Ukraine is a genocide perpetrated by Russia, on Ukrainian culture.

Interfax, a news outlet of Ukraine, has published a news article, writing about the harmful consequences of the Russian invasion on Ukrainian culture. 221 libraries damaged, and around a hundred destroyed.

Another news article about the impact of war on Ukrainian culture: by the Guardian. Sanitizing and filtering information, controlling the media and the news, has always been a crucial part of sustaining a dictatorship, and plays a key role in supporting a lasting, totalitarian regime. In a world where the news is subjected daily to censorship, being examined thoroughly for anything that might provoke or suggest retaliation against people in authority, is a dystopian world which we have been warned about by numerous literary works.

The war in Ukraine is hybrid warfare, both fought vigilantly with propaganda and heavily filtered content. Both use propaganda as a means to accomplish their goals. and through information. It is in the forms of historical revisionism to false campaigns supported with disinformation, which Russian media portrays. It is also impossible to show the true nature of the war in Ukraine in Russian media, as all protestors in Russia who have campaigned against the invasion of Ukraine have been detained and imprisoned by order of the Kremlin.

An article written by Emma Létourneau explains this further and in more detail than I can. It was published on Artshelp. It is titled, "Russia's War Against Ukraine and the Impact on Art and Culture". It provides you with a valuable insight about the war happening in Ukraine.

The New York Times has also released an article about this, but it is locked behind a paywall. This is a link to said article, but without the paywall, made possible because of Internet Archive's web archiving feature. It explains, and in great detail, about the repercussions which conflict brings, especially to a nation's heritage, identity, and culture.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

so it's nice to see a lot of backlash against the proposed Missouri legislation overseeing material in public libraries, but most of the times I've seen it on tumblr it's been in the context of "this is antis' fault" or whatever and like. libraries have been dealing with this shit for ages, do we have to make it about the fandom drama du jour for anyone to give a damn

#i can promise you your tumblr squabbles over fanfic are not the primary influence#in a long history of library censorship struggles#and there are a lot of complex discussions going on in the library profession right now#about things like meeting room policies and collection development and content warnings#and the professional ethics of having something like anti vax content on your shelves#and basically we're talking about some similar issues except we're capable of being goddamn adults about it#and I don't love seeing my profession and state only mentioned to score internet drama points

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Graphic Recommendations

This year has been an excellent one for readers of graphic novels. I've been reading quite a few during the pandemic when longer form books just seem like too much of a time investment or my attention span is limited. Falling into the visuals can be just the thing I need when the world seems a bit chaotic. Here are a few I highly recommend.

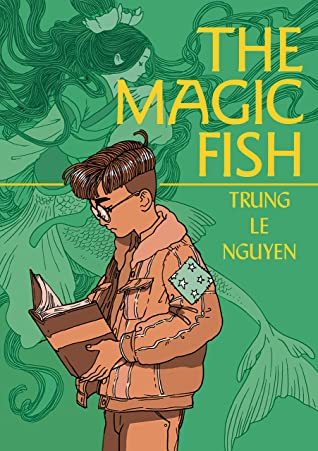

The Magic Fish by Trung Le Nguyen

Random House Graphic

Real life isn’t a fairytale.

But Tiến still enjoys reading his favorite stories with his parents from the books he borrows from the local library. It’s hard enough trying to communicate with your parents as a kid, but for Tiến, he doesn’t even have the right words because his parents are struggling with their English. Is there a Vietnamese word for what he’s going through?

Is there a way to tell them he’s gay?

A beautifully illustrated story by Trung Le Nguyen that follows a young boy as he tries to navigate life through fairytales, an instant classic that shows us how we are all connected. The Magic Fish tackles tough subjects in a way that accessible with readers of all ages, and teaches us that no matter what—we can all have our own happy endings. — Cover image and summary via Goodreads

Displacement by Kiku Hughes

First Second [Jessica's Review]

A teenager is pulled back in time to witness her grandmother’s experiences in World War II-era Japanese internment camps in Displacement, a historical graphic novel from Kiku Hughes.

Kiku is on vacation in San Francisco when suddenly she finds herself displaced to the 1940s Japanese-American internment camp that her late grandmother, Ernestina, was forcibly relocated to during World War II.

These displacements keep occurring until Kiku finds herself “stuck” back in time. Living alongside her young grandmother and other Japanese-American citizens in internment camps, Kiku gets the education she never received in history class. She witnesses the lives of Japanese-Americans who were denied their civil liberties and suffered greatly, but managed to cultivate community and commit acts of resistance in order to survive.

Kiku Hughes weaves a riveting, bittersweet tale that highlights the intergenerational impact and power of memory. — Cover image and summary via Goodreads

Flamer by Mike Curato

Henry Holt and Co.

I know I’m not gay. Gay boys like other boys. I hate boys. They’re mean, and scary, and they’re always destroying something or saying something dumb or both.

I hate that word. Gay. It makes me feel . . . unsafe.

It's the summer between middle school and high school, and Aiden Navarro is away at camp. Everyone's going through changes—but for Aiden, the stakes feel higher. As he navigates friendships, deals with bullies, and spends time with Elias (a boy he can't stop thinking about), he finds himself on a path of self-discovery and acceptance. — Cover image and summary via Goodreads

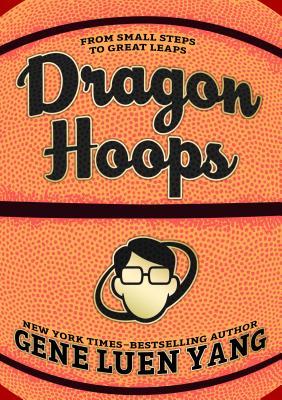

Dragon Hoops by Gene Luen Yang

First Second

In his latest graphic novel, New York Times bestselling author Gene Luen Yang turns the spotlight on his life, his family, and the high school where he teaches.

Gene understands stories—comic book stories, in particular. Big action. Bigger thrills. And the hero always wins.

But Gene doesn’t get sports. As a kid, his friends called him “Stick” and every basketball game he played ended in pain. He lost interest in basketball long ago, but at the high school where he now teaches, it’s all anyone can talk about. The men’s varsity team, the Dragons, is having a phenomenal season that’s been decades in the making. Each victory brings them closer to their ultimate goal: the California State Championships.

Once Gene gets to know these young all-stars, he realizes that their story is just as thrilling as anything he’s seen on a comic book page. He knows he has to follow this epic to its end. What he doesn’t know yet is that this season is not only going to change the Dragons’s lives, but his own life as well. — Copy image and summary via Goodreads

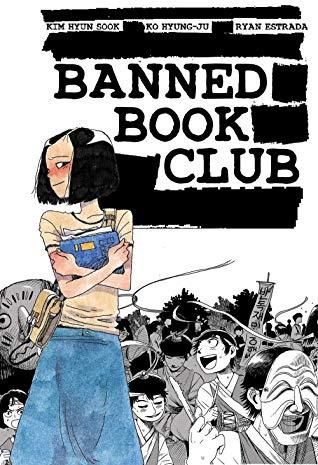

Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook, Ko Hyung-Ju, Ryan Estrada

Iron Circus Comics [Crystal's review] [Q&A with Kim Hyun Sook & Ryan Estrada]

When Kim Hyun Sook started college in 1983 she was ready for her world to open up. After acing her exams and sort-of convincing her traditional mother that it was a good idea for a woman to go to college, she looked forward to soaking up the ideas of Western Literature far from the drudgery she was promised at her family’s restaurant. But literature class would prove to be just the start of a massive turning point, still focused on reading but with life-or-death stakes she never could have imagined.

This was during South Korea’s Fifth Republic, a military regime that entrenched its power through censorship, torture, and the murder of protestors. In this charged political climate, with Molotov cocktails flying and fellow students disappearing for hours and returning with bruises, Hyun Sook sought refuge in the comfort of books. When the handsome young editor of the school newspaper invited her to his reading group, she expected to pop into the cafeteria to talk about Moby Dick, Hamlet, and The Scarlet Letter. Instead she found herself hiding in a basement as the youngest member of an underground banned book club. And as Hyun Sook soon discovered, in a totalitarian regime, the delights of discovering great works of illicit literature are quickly overshadowed by fear and violence as the walls close in.

In Banned Book Club, Hyun Sook shares a dramatic true story of political division, fear-mongering, anti-intellectualism, the death of democratic institutions, and the relentless rebellion of reading. — Cover image and summary via Goodreads

Almost American Girl by Robin Ha

Balzer + Bray

A powerful and timely teen graphic novel memoir—perfect for fans of American Born Chinese and Hey, Kiddo—about a Korean-born, non-English-speaking girl who is abruptly transplanted from Seoul to Huntsville, Alabama, and struggles with extreme culture shock and isolation, until she discovers her passion for comic arts.

For as long as she can remember, it’s been Robin and her mom against the world. Growing up in the 1990s as the only child of a single mother in Seoul, Korea, wasn’t always easy, but it has bonded them fiercely together.

So when a vacation to visit friends in Huntsville, Alabama, unexpectedly becomes a permanent relocation—following her mother’s announcement that she’s getting married—Robin is devastated. Overnight, her life changes. She is dropped into a new school where she doesn’t understand the language and struggles to keep up. She is completely cut off from her friends at home and has no access to her beloved comics. At home, she doesn’t fit in with her new stepfamily. And worst of all, she is furious with the one person she is closest to—her mother.

Then one day Robin’s mother enrolls her in a local comic drawing class, which opens the window to a future Robin could never have imagined. — Cover image and summary via Goodreads

For a few older titles, you can check out the lists we've created in the past:

LGBTQ POC Comics

3 Quick Comic Book Reads

Women's History Month

Getting Graphic

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orion Digest №29 — The Imperative to Fight Against War and Oppression

The world faces a clear and present danger — the quest for greater power. That lofty goal of being raised above others, of being at the top, is one people have sought after for all of human history — and as a result, we have hardly ever gone a year without war, and the concept of being born in a comfortable life without struggling against disadvantage are left to chance. It’s not as if life has to be this way — everyone in the world has a need, and society in its most ideal would serve to use the resources around us to make those needs fulfilled. But even if ‘world peace’ is a goal everyone would like to promote, our world’s current power structure has proven time and time again to be incapable and incompetent at the simple task of achieving it.

World peace is by no means a push of a button, but compared to all we have done, it is relatively simple. We’ve evaporated cities, dug trenches that connect oceans, created vast cities and libraries from the forests and plains we were born into. I speak to you now over a vast, global system of communication accomplished through machines in the sky, available simultaneously wherever you are in the world. To understand that no one can win in the end by trying to create imbalance, by trying to push agendas onto others without effective communication, is a concept we try to teach to toddlers, yet it is something that the nations and factions of the world cannot bring themselves to grasp through the fog of the narrative they have built. Call it protection, call it a crusade, but in the end it’s greed and stubbornness.

Right now, across the world, people are at each other’s throats because the idea of coexisting is intolerable to them. The states of Israel and Palestine wage war against each other over ancient land, stolen and fought for over the course of thousands of years. The insistence upon Israel as a sovereign state rather than the integration of both into a state based on structure and not religious determination keeps the citizens of both nations in fear and anger — a bloodbath in the making all for allies to make a profit and meet a quota. Further east within Eurasia, the People’s Republic of China cracks down upon its citizens with violent force and censorship, undermining the basis of their argument by turning into the very monster secessionists make them out to be. Rather than hear out the claims of their citizens, they choose instead to use live fire, tear gas, and media silencing to solve issues — plugging a leak while creating ten more. Across the ocean, the United States finds itself unable to answer the problems of increasing gun violence, ecological destruction, public health risks, and the incompetence of its own justice system due to the idea that any give will allow the “other party” to gain ground, and thus we must fester in our national stalemate.

The list goes on and on, but the problem remains the same — the world powers as we know them now, whether economic or political, have lost touch with the people they represent, and are so lost in the world they know that they will never achieve world peace. Fighting and scheming around others for the good of their own citizens is their modus operandi, but they cannot see that even their own citizens are losing faith. Worse still, as they fight enemies abroad, they fight their constituents at home, until the question really becomes “who are they fighting for?” This conflict, these wars, this suppression of outcry and questioning loses any inherent sense of morality, and one thing becomes clear — modern government has become incompetent. Perhaps it always was, and the previous millennia were just a story of corrupted growth into what we are today.

So long as people suffer, as long as innocent civilians bleed and die and go hungry because of the conflict of factions and governments, we have a moral imperative to find a better way, and to achieve change as quickly and efficiently as possible. This question of how to build a better world is not just an abstract thought — it is a solution to a real and present danger, a ticking timebomb where every second costs lives. We’ve stumbled as an international society enough times throughout human history to know better, but those in power see a global society as a standoff where only the foolish put their gun down first, rather than a community where everyone has needs, and working together logically, we can distribute the resources and assistance to make sure all those needs are filled.

This isn’t a problem any one nation is responsible for — every nation contributes to it, and every nation must stand down or be made to stand down. So long has mistrust been the way of the world that it is hard to fathom ever letting our guard down, and surely, if one nation were to let themselves be open, another might come in and become opportunistic, unconvinced that every other nation would follow the first’s example. The first nation would then learn to not trust the others, and because of that shared belief that all others would take advantage in a moment of weakness, no one would step forward in the first place. So, if the current existing governments are not willing to sacrifice power for the sake of using it for the greater good of helping and healing the world, they should not be entrusted with it.

It is our imperative specifically to make and fight for change while others suffer, because complacency with unequal and unjust distribution of power and resources makes one yet another resource to add to the wealth of the corrupt. If you simply feel anger but continue along the same path, you will still have serviced that which you hate — another brick lain in the tower. There is no sense of neutrality — we must act together in the interest of ending bloodshed across the world. If ever there was a reason to fight, the growing death and poverty on Earth is absolute just cause. Our opponent is not any one person — it is instead this way of thinking, this system of war and mistrust constructed by fear, and the politics and economics that perpetrates it. It is a battle that must be fought not with guns and bombs but speeches and shields; protecting those in danger and calling with every voice on Earth to stop the train before it runs us all off the tracks.

Society is a construct that should always be for the benefit and ease of the citizens within it. It is a machine we created for the purpose of automating practices too confusing for each person to figure out all on their own. It has lost its purpose of it disadvantages and harms the people within it, and you do not keep using a broken machine, let alone worship it. You fix the machine, and if unfixable, you replace it. It doesn’t matter how old or big our nations and their governments are. It doesn’t matter how important decorated medals and positions may be. As long as just one person is unjustly hurt or unfairly treated, it is our duty to our human family to fight to our last breath until the problem is fixed, no matter how far we have to go, no matter how bold we must be.

- DKTC FL

#imperative#war#oppression#israel#palestine#china#taiwan#esf#power#world peace#politics#international politics#world politics#orion#orion digest#sword of orion#government#corrupt government#broken machine

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before Night Falls

The tone of the writing is bleak at times. Reinaldo Arenas describes the struggles he experienced in the country during his childhood. There are sexual interactions that he had with people around him that could be considered sexual abuse. Arenas may not see it that way because it was normal to explore sexual desires with whoever or whatever was around in the countryside. The tone was ever-changing and depended on the stage of life that Arenas was in. When he was in the county, he felt in his element, but he was confused about his sexuality. Arenas tried to suppress his love for men; it created a hopeless tone for the writing. The way he speaks about the people who did not hide their sexuality is with admiration. He was impressed by those who accepted their feelings and did not hide for fear of persecution. When Arenas witnesses the support that others around him have for communist Cuba, there is a tone of fear. The political climate in Cuba is unstable, and no one is safe from Fidel Castor's control.

The atmosphere of the reading was unstable, and things were never what was expected. The sexual desire that Arenas felt was all over the place, and hiding his genuine desire for men was only making it harder for him. The political state went from one dictatorship to another. Fidel Castro took control under false pretenses, and this only creates a more fragile political state. When the people took to the streets, once they heard the truth about their leader's intention, they went along with it. They were indoctrinated into communism, and to object meant death. Arenas knew this, and it is why he pretended to show support for what happened. He was already in constant danger because he was gay, and showing his actual distrust for Fidel Castro would have put an even bigger target on his back. People were being prosecuted for their sexuality. “sweetness. Little by little, those enemies started to make headway, saying that María Teresa was a lesbian, an aristocrat, and a counterrevolutionary, and they finally managed to get her replaced” (Arenas, 72). She was accused and persecuted even though she was just rumored to be gay. Throughout the reading, I could only feel an anxiousness about what was going to happen next. The history of the book is well known, but the events that Arenas experienced were never predictable. There was danger around him, and he was close to getting outed because of the people around him. Arenas wanted to learn and improve his writing skills, and the people who were willing to help him were against Castro. His association with these people made him suspicious. Arenas is constantly on the brink of losing everything. His writing is starting to be recognized but has yet to make the impact that he wants.

While reading this, I was shocked, and at one point, I had to put the book down. I could not handle the description of animal cruelty that Arenas had written about. Arenas mentions witnessing that “Sheep would be hung by their legs to have their throats slit, and after the blood had been drawn, while they were still half alive, they would be cut into pieces” (Arenas 20). There were so much cruelty and pain around people and animals. It made me think about what the people in the town had experienced and what cruelty they do to each other. Arenas mentions, “We had returned to the times of Nero, the times when the masses rejoiced in watching how a human being was being condemned to death or murder before their eyes” (Arena, 59). People enjoyed the fact that they could get someone killed if they disagreed with Fidel Castro’s belief. Surprisingly, Arenas did not end up as a cruel person who would give up those around him in Castro's support. The university he attended had brainwashed everyone who attended, but he saw what was going on before public knowledge. Arenas even admitted that there were people in power who were openly gay but were not arrested because they supported communist Cuba. Arenas was educated and knew how to use his words to create a reaction. If he wanted to, he could have climbed the political ladder and loved whom he wanted, but he kept his viewpoint and saw the system's right and wrong.

The issues seen throughout the reading are endless. Arenas describes the executions of those who opposed Castro and the persecution that the gay community experienced. Cuba was struck by poverty, violence and people were using the system to get rid of people they did not like. Arenas depicted the unstable nature that existed within the citizens of Cuba. Whether it be people living in fear of being gay or having someone lie to get rid of them, Cuba's people were never truly safe. The trial system did not rely on evidence; if there was an accusation, it was enough for someone to be sent to jail or be executed. Arenas wrote the book not to highlight his experiences but everyone's experience. He does not only focus on himself, and he brings in everyone's beliefs and actions. In the “... decade of the 1960s, when the state assumed an ever more prominent role in policing sexual behavior and identities,”. (Lambe). The Cuban government tries to control all aspects of life. He writes to show how those around him helped him grow, but he also depicted their downfall because of communist Cuba. Arenas wanted to show how everyone under Castro's control was a victim who could not escape their captor. In the end, “the executions were thus for Fidel a measured attempt to ensure the survival of Cuba's revolution, as well as to propagate long-term political transformation. (Karl). Many people died during the revolution and suffered right after the revolution under Fidel Castro’s control.

In the end, the dissidence, homosexuality, and literature all correlate with the Cuban Revolution. The disagreement of homosexuality and censorship of literature played significant roles in the revolution. Many people died and were punished for their sexuality or even being accused of being homosexual. Arenas mention in the library chapter, “I decided the Library was no longer a place for me either. Any book that could be deemed to be “ideological diversionism” disappeared immediately. Of course, any book dealing in any way with sexual deviation also vanished”(Arenas, 73). Many things were being used to punish people if the government didn’t agree with them. This type of censorship limited the revolution and cost. Arenas was writing to spread his word and the truth about Cuba. He mentions that he had lost some of his work, and some disapproved of his writing because of its topics. “Arenas was also writing as an ‘outlaw’ since some of the episodes in which he had become involved fell within violation of sexual laws in Cuba.” (Ocasio). Arenas was becoming free through his writing. Still, in reality, he could not be seen in public without the fear of someone turning him into the government.

Works Cited

ARENAS, REINALDO. BEFORE NIGHT FALLS: a Memoir. PENGUIN Books, 2020.

Karl, Robert A. “Reading the Cuban Revolution from Bogotá, 1957–62.” Cold War History, vol. 16, no. 4, 2016, pp. 337–358., doi:10.1080/14682745.2016.1218848.

Lambe, Jennifer L. “Historicizing Sexuality in the Cuban Revolution.” Radical History Review, vol. 2020, no. 136, 2020, pp. 217–232., doi:10.1215/01636545-7857392.

Ocasio, Rafael. “Arenas, Reinaldo (1943-1990), Novelist and Political Activist.” American National Biography Online, 2000, doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1602886.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Open Letter to His Cop Father

My hope is to make clear, maybe for the first time, my perspective on a variety of points of contention between you and me, not so that we can reconcile them necessarily, but so that I won't feel the need to tiptoe around you any more. Addressing this problem I have with codependency and self-censorship has been my task ever since I left my ex, and I think you yourself would agree that in the last year and a half, I have become much more vibrant and present than I ever was as the kowtowed ghost who let his controlling girlfriend dictate the terms of his existence. In the following letter I strove to be unsparing, but only for the sake of clarity. I don't hold any resentment towards you. I want to take ownership of my own role in our dynamic so that we can move into the future, unencumbered.

A few months ago, you and I argued over my career with regard to the classes I plan on taking for my Masters in library science. After we'd each calmed down, you said that you were only suggesting I keep my options open, as we'd both noted that the future of public libraries, and indeed social services generally, is uncertain at best and possibly doomed. You merely meant to suggest that I look into classes that would prepare me for information career opportunities in the private sector, in the probable case that public libraries no longer exist in the future.

At the time I didn't want to argue any more, and I agreed that you had made good points. I would keep my options open. What you didn't understand, however, was that I only grew "defensive" about my plans after I thought I presented them as exactly what you claimed to be suggesting—that is, I would look into a variety of library and information science related fields while keeping my focus, somewhat idealistically, on public libraries. But then you interjected, as you so often do, with all the reasons why my plan might not be such a great idea. Had I considered the uncertain future of public libraries? (Of course I had.) Wouldn't a librarianship at a prestigious museum be a more stable and lucrative career? (Maybe, but nothing's a safe bet.)

Because I stood my ground, because I intend to fight for what I believe in while I still can, you accused me of being 'defensive.' There's always an underlying tension between us, you said, which is something I don't deny. Why do I always seem resentful? you asked. You accused me of only viewing you as a resource to draw on without any care for you as my father, a totally unfair and manipulative thing to say of your son who followed you and your other son for a decade, watching you coach his brother’s baseball team, without him; your son who desperately wished his father understood his art and literature recommendations, but knows they'll usually go unheeded; your son who, despite knowing what his father did to his mother, and resenting that his father won't speak with his mother at all, still loves his father.

You can't seem to recognize sometimes that your mistakes could have had any effect on the way you and I relate, and I think you think any antagonism between us is me blindly rebelling, an absurd image to have of me, the most docile black sheep any flock has ever had. To be clear, what causes the tension between us is a feeling in me that I won't even be heard if you've previously decided you're in the right. So rather than speak up, I generally keep my mouth shut, which is not healthy for me, nor is it productive of the kind of relationship I'd hope to have as an adult with my father.

You would prefer that I not stake my future on public librarianship, because you would not do that. Therefore, I shouldn't do that. I don't care whether you disagree with me. Ultimately, none of this letter is about convincing you of anything. What I want to address is that I have never felt like my voice would be heard, by you or anyone, really, which is in part a result of having my perspective so often subjected to critical (over)analysis from you, as in our argument over public libraries. Or, it’s a result of having my enthusiasm mocked anytime you and my brother didn't appreciate something I did. 2001: A Space Odyssey is a masterpiece of American art, and you Philistines didn't watch more than 15 minutes of it, but to this day you make fun of me for wanting to watch it with you.

When we had disagreements over any supposed transgression on my part, you quickly dropped the pretense towards being a concerned parent to assume your interrogation persona, with me the guilty-until-proven-innocent suspect. One of the oldest tricks to get someone to fess up is asking the same question several times, forcing the suspect to repeat their story. Any time you seemed suspicious I wasn't answering your questions straight, it would be "You sure? Positive? Nothing else?" The only thing missing was the aluminum chairs and the spotlight in my face. All disagreements were structured this way, with you above, already having the answers, and me below, forced to acquiesce to the judgement presumed. Attempts to defend myself when I felt I was unfairly accused were met with the reprimand to not "talk back," something I've internalized deeply, corrosively, finding myself drawn, in friendships and in love, to those who shout me down or laugh me out. As a result, my natural cowardice and timidity have festered for years.

You have long urged me, since childhood, to be more assertive, less passive, to stop "playing the victim," and these were not unfair or inaccurate criticisms. Like Kafka with his father, none of this is to say I blame you for the effect you've had on me and my inability to speak up. I was a timid child, easily influenced by social pressure and a need for approval, most especially from you. From my child's view I was enamored of what you seemed to represent, which I suppose is unremarkable, as sons and fathers go. Perhaps also unremarkable of fathers and sons is how elusive your approval seemed to be. There was never outright disapproval of me from you, and I always knew you "supported" me. But let's not pretend like we at times did not and do not appear alien to one another. Which is normal, healthy, so long as it's accepted, because we’re separate people, but the trouble fathers and sons get into is they each seek validation from the other—the father struggles to impose his own standards on the son and see his progeny flourish as so judged by the standards imposed, and the son seeks to establish himself as his own person, separate but unable to escape the looming shadow of his father, the son's primary model for what a person is.

One instance where I probably tried to voice an objection to your discipline, an instance where I knew the gravity of the issue you wanted to convey but disagreed that what I'd done deserved such a strong reprimand from you, was when I drew a Klansman in my notebook, being the bored and doodling 8th grade boy that I was, watching a documentary about the Klan in history class. I wasn't approving of the Klan by drawing a man in a pointed hood, but to your credit, you saw an opportunity to make clear the need to take seriously the violence and oppression that African-Americans have faced in this country, and to never trivialize symbols of that violence and hatred. (Fatefully, I was similarly firmly scolded by my mom when she saw a swastika in one of my notebooks, which is when I learned my Polish grandmother escaped the Nazis as a small child in the belly of a freight ship, traumatized by the sight of dead stowaways floating past her, and this after the death of her brother at the hands of fascist thugs.)

When the black community today raises the cry "Black Lives Matter," what they want is a reckoning from American society for the way that black life has historically been deemed disposable. Africans were ripped from their mother country, brutalized on a treacherous trans-Atlantic voyage, and sold off in a land where the climate and environment were entirely alien, their various languages as unintelligible to one another as to their masters. They were subjected to centuries of horrific slavery, whippings, rape, and familial rupture. Any who managed to escaped their bondage risked dogged, murderous pursuit by slave patrols. The de facto opponents of slavery won a civil war and slavery was abolished, and for another century black people were terrorized with lynchings by whites (who were never prosecuted), all while being denied economic opportunity and treated as less-than-second-class citizens in public spaces, not to mention suffering a complete lack of political representation. It wasn't until 1968 that the political rights of African-Americans were codified into federal law, but the mere granting of rights does nothing to address the long term devastation wrought on the black community, which built this country for free, this country that so long denied them not only equal rights and opportunity, but denied them their humanity. And to this day, black people go murdered, in broad daylight, in their cars, or while they sleep, both by the police and by others, without justice. "Black Lives Matter" needs to be said because American society does not seem to acknowledge that black life matters, despite America's lofty ideals for itself as a place of equal protection under the law. If black lives matter, then all lives matter, but not all lives matter until black lives matter.

Saying "Blue Lives Matter" is to be presented with that history, turn it around and say "Yeah, well what about us cops?" No one chooses to be black; all cops choose to be cops. If you want the profession of policing to have the respect you demand people give it, then cops should be aware what they're signing up for: a thankless, demoralizing job that answers to the public, and not the other way around. To say "My job is hard so we matter too!" when, after centuries of oppression, the black community says, "Our lives matter!" is a gross exercise in bad faith. This is why "Blue Lives Matter" is offensive, utterly bankrupt beyond the expression of resentment towards an imagined enemy. American society has no doubts about the value of the lives of police officers. What easier way is there to bring the full force of the American justice system, with a swift investigation and aggressive prosecution, than to murder a cop? The justice system has time and again demonstrated the societal value of police officers' lives. The same can not be said of black lives, which is why "Blue Lives Matter" is far more trivializing of the racism still faced by black people in America than some 13-year-old kid's drawing of a Klansman.

Part of me worries that writing this is futile, that you'll see this as another instance of me "talking back," i.e. saying what challenges your airtight prosecutor's argument. Another part of me thinks what I’m saying resonates with your bedrock American and Catholic values. After all, I had to get my principles from somewhere. But if this doesn't move you, I will rest well knowing that at the very least I'm not shutting myself up any more, and that I'll finally be coming to you as a man and not as your child, facing you squarely, head no longer bowed.

I love you.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! Would you happen to know what other lines were localized to make Edelgard come off better? I'm always curious about localization changes.

Thank you for your ask! Here are the ones that stand out the most for me right now. They are available from this post tumblr post (recommended read, as both the direct translations and the input about them are interesting)https://nanigma.tumblr.com/post/187449339197/crimson-flower-ending-epilogue-japaneseTranslation: After Fhirdiad’s surrender, both the Holy Kingdom of Faerghus and the Church of Seiros disappeared from the history of Fodlan.English Localization: With the fall of Fhirdiad, the Holy Kingdom of Faerghus and the Church of Seiros both vanished into the people’s memories.My take: The direct translation implies that Faerghus and Church of Seiros were removed from historical record. History and memory are definitely different - while various countries that existed in the past no longer exist now (and if you go back long enough, no one has personal memory of them), it would be wrong to say that they all disappeared from history. As long as historical record of them exists, they are part of history.

The only way they would disappear from Fodlan’s history is if historical records of them are destroyed - in other words, censorship/historical revisionism/tampering with history. Fodlan has various libraries and book stores. You can go down the street and just buy a book. Only way Faerghus and the Church disappear from history is if you go book burning essentially.I don’t really see the point of this part being in the original Japanese ending if not to imply that historical records were changed to remove mentions of Faerghus and the Church - after all, players already know that Edelgard conquered all of Fodlan (and destroyed the Church) and that fact is even reminded in the ending text elsewhere.

Also, countries are one thing, religion is another. Most people in Fodlan were Church of Seiros believers, if Edelgard is not actively oppressing believers, I doubt the church is going to simply fade into memory or disappear from history.

Translation: Imposing a strongly centralized authority, Edelgard started working on a reform that would dismantle the nobility. She set out to create a new world where no one would be judged on the basis of crests.

English: Embracing her newfound power, Edelgard could at last set about destroying Fódlan’s entrenched system of nobility and rebuild a world free of the tyranny of Crests and status.

My take: The english version has no mention of the strong centralized authority. I honestly get major authoritarian vibes from Edelgard and her empire, and yet the english version does not mention that, instead it’s just a vague “new found power.”The english version also adds in something about a world free from status, which the direct translation does not have. Status can exist without nobility - ie. celebrities, the rich, politicians, etc, so this feels like an embellishment to make her look better.

Translation: Behind the scenes, the empire would take a clearly hostile stance with „Those who slither in the dark“, who they had formerly collaborated with, and silently began to wage war on them in places without witnesses.

English Localization: Yet beneath the surface, an unseen and silent struggle began to take shape. From her seat of power, Edelgard could at last wage war against those who slither in the dark.

The Japanese version here goes more direct in saying that the Empire is keeping their collaboration with the genocidal slither people a secret. Coupled with the implication of historical censorship regarding Faerghus and the Church that I’ve mentioned above, it’s clear to me that Edelgard’s empire is willing to hide historical truths in order for the empire to look better.

Nationalist sentiment in the Adrestian Empire seems to be that Faerghus should have never split from the Empire. Now that Edelgard is in control, she can remove that loss of Adrestian pride from the books - the Empire was always whole and there was no civil war!

Now all of these are subject to interpretation. They could just be poor or misleading translations. After all, we can’t actually know whether they were translated in the way they were to make her look good unless they say as much. But this is just the impression I’ve gotten. That impression is why I’m also curious if in the Japanese version, players are also forced to sympathize with Edelgard like they are in the english version.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

New world news from Time: ‘It’s So Much Worse Than Anyone Expected.’ Why Hong Kong’s National Security Law Is Having Such a Chilling Effect

After more than a decade, Martin suddenly quit writing his column. He said goodbye to his readers, editors and colleagues. But he did not name the fear that prompted him to abandon his commentaries—at least not until he left Hong Kong.

“The day [the national security law] passed I just couldn’t write anything. I stared at the screen for hours,” he messaged TIME from onboard his flight out of the semi-autonomous enclave. “I hate self-censorship, so I’d rather call this an end.”

Martin, who asked that his real name not be used because he needs to return in the future, is hardly the only one to fall silent rather than risk tangling with the draconian new restrictions.

In the three and a half weeks since the enactment of the law at the end of June, a sense of fear and uncertainty has taken hold in Hong Kong, where anything seen to provoke hatred against the Chinese government is now punishable with up to life in prison. Some people have redacted their social media posts and erased messaging app histories. Journalists have scrubbed their names from digital archives. Books are being purged from libraries. Shops have dismantled walls of Post-it Notes bearing pro-democracy messages, while activists have resorted to codes to express protest chants suddenly outlawed.

The first arrests came just hours after the law was implemented. On July 1, the 23rd anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China from Britain, hundreds of protesters were rounded up for unauthorized assembly amid the coronavirus pandemic. Ten, including a 15-year-old girl and a 23-year-old motorcyclist who drove into police, were accused of breaching the new law, mostly by carrying separatist stickers and pro-independence flags.

In at least one respect, the regulations are already proving successful: the sometimes violent demonstrations that flared across the freewheeling Asian financial capital over the past year have largely evaporated. The unrest, which seized university campuses, paralyzed public transportation and brought police and petrol bombs into residential neighborhoods, wrought millions of dollars in damages and plunged Hong Kong into a recession. It also challenged Beijing’s bottom line as the movement morphed into an open challenge of the Chinese Communist Party’s authority, with demonstrators sporting American flags, beseeching foreign governments to intervene and increasingly chanting, “independence, the only way out.” Their fight brought this previously stable financial capital directly into the crux of imploding U.S.-China relations.

To Beijing, the legislation is necessary to secure its sovereignty over the territory. “People in Hong Kong can still criticize the Communist Party of China after the handover,” Zhang Xiaoming, deputy director of the Chinese government’s Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, reportedly said at a press conference earlier this month. “However, you cannot turn these into actions.”

Read more: Hong Kong Is Caught in the Middle of the Great U.S.-China Power Struggle

Some hope the crackdown will only be temporary as Beijing restores stability. But others fear the far-reaching new law marks the arrival of authoritarian control in a city that has long cherished its freedoms and independent judiciary.

“Overnight, Hong Kong has gone from rule of law to rule by fear,” says Lee Cheuk-yan, a veteran activist and former legislator.

Lee chairs the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China, which established the world’s only museum dedicated to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest movement in Beijing. Afraid the museum, and its advocacy of an end to one-party rule in China, may fall foul of the new law, the alliance is rushing to raise $200,000 to digitize its archives.

While Lee and his colleagues discussed moving the artifacts abroad, including video footage and items donated by mothers of students killed in the bloody military crackdown, doing so seemed like handing victory to the Chinese government and its attempt to erase the event from collective memory. But keeping the operation running is now a game of dramatically higher stakes.

“Our worry is that the law is so vague about everything and so broadly defined that we don’t know how they will categorize our organization,” Lee says. “Will they strike at us?”

That sense of foreboding hangs over many organizations as they speculate what might make them a target.

Chan Long Hei—Bloomberg/Getty Images Police officers stand guard outside the Office for Safeguarding National Security in Hong Kong, set up at the Metropark Hotel, in Hong Kong on July 8, 2020.

‘We should all be making plans’

Drafted in secret, the law only became public as it took effect shortly before midnight on June 30. By morning, boats bearing giant red and yellow banners sailed across Victoria Harbor heralding the new legal regime.

Though the new measure specifically bans subversion, sedition, terrorism and collusion, several lawyers who are experts in Chinese law told TIME the phrasing of these crimes can be interpreted so expansively as to apply to almost any activity or speech. On the mainland, similar charges are routinely wielded to crush even moderate dissent.

“It’s so much worse than anyone expected. It can encompass all the acts we have been doing in the protests over the last year,” says Lee, who is facing multiple charges of unlawful assembly stemming from before the law’s enactment.

The Hong Kong government insists the new law will only affect a small minority of people, and that the city’s free speech is not under threat. But officials also say that the law encompasses popular protest slogans, including “Liberate Hong Kong” and “Hong Kong Independence,” that are now deemed to be inciting others to commit secession or subverting state power.

It remains unclear how far the law’s 66 provisions—which touch on education, media, non-governmental organizations, universities, the internet, social organizations, international organizations, elections and more—will extend.

“Each day the government announces something new about this law,” says Fung Wai-wah, president of the pro-democracy Professional Teachers’ Union. “The red line is still moving.” Stoking concern for academic freedom, schools have been told to review course materials, books and libraries to ensure nothing is in violation. “This censorship is as irrational as it is ambiguous,” Fung adds.

For the first time, Chinese security agents will operate openly in Hong Kong, while the most serious offenders may be extradited for trial in the Communist Party-controlled courts on the mainland. Simon Young, associate dean of the University of Hong Kong’s law school, suspects that if such extradition powers are used “It may well be that we don’t know until after the person has entered the mainland jurisdiction. It’s certainly something that keeps us guessing and in fear.”

The city’s top official, Chief Executive Carrie Lam, denies there is “a wide spread of fears [sic]” among Hongkongers, even as a Chinese government official warned the law is intended to act like “a sharp sword hanging high” over the heads of potential offenders.

“This is not just a new law, it’s really a new order in Hong Kong,” says Fred Rocafort, a former diplomat and legal expert on China at law firm Harris Bricken. He expects “relatively constant applications of the law for even relatively minor acts” as this state of affairs is established.

Read more: ‘Hong Kong Is Freer Than You Think’

Some see a deliberate deterrent effect in the law’s ambiguity.

“The whole purpose is to incept people’s minds so they have to ask the question of whether everything they do is maybe a violation,” says Peter Yam, a film producer currently working on an independent documentary about the Hong Kong protests.

While the subject matter could be considered incendiary in the current political climate, Yam says he and the crew have discussed the law and don’t want to focus on it. “If our films are put under review and censored then there’s nothing we can do,” he says.

Since the law was enacted, Yam has received a stream of messages from friends and colleagues debating whether it’s time to leave the city for good.

“I want to stay until the last moment,” he says. “At the same time, we should all be making plans.”

While Australia, Taiwan and the U.K. are all offering avenues for fleeing Hongkongers, many of the 7.4 million residents of one of the world’s most starkly unequal cities cannot afford an exit strategy. Those who stay will have to navigate what it means to lose some of the liberties that distinguished their home from the mainland.

In 1997, the former British colony was grafted back onto China under a political formula known as “one country, two systems,” designed to preserve its separate legal and political systems within an authoritarian state. The conceit meant Hong Kong was the only place in China where calls for political reform could be full-throated, and the color and vulgarity of anti-government invectives were limited only by imagination. Here, publishers hawking banned books and practitioners of the outlawed Falun Gong spiritual movement could promote literature inaccessible just over the border. Unfettered by censorship, the hard-bitten local press documented any perceived interference by Beijing.

Lam, the city’s leader, said she could guarantee the press would not be targeted by the new law only if all reporters also gave “a 100% guarantee that they will not commit any offenses under this piece of national legislation.”

Rachel Cartland, a former civil servant and long-time guest presenter for Hong Kong’s public broadcaster RTHK, found the government’s statements less than reassuring. She announced she was stepping down from a radio program over the new law, just days after its enactment.

“I put aside this thought of, well, ‘How likely are they to come after me?’ and just looked at it dispassionately,” she says. “People are really going to have to think through: how is this going to affect me?”

‘The cost of politics will be much higher’

The government is expected to “strengthen the management” of foreign nongovernmental organizations and news agencies, according to the law, a condition that has prompted deep concern and expedited corporate relocation plans. On July 14, the New York Times announced it was shifting its Hong Kong-based digital news operation to South Korea, citing visa problems and the city’s “new era under tightened Chinese rule.”

The police force has also been given sweeping new powers to regulate online content and intercept communications. Companies may be compelled to remove content deemed a threat to national security and to handover private user data. In response, tech giants like Facebook and Google announced a pause on data requests from Hong Kong.

Meanwhile, primary elections held by pro-democracy parties mid-July could be considered a violation of the national security law by way of “subverting state power.” (The government alleges that the primaries were potentially subversive because the stated aim of many candidates, if elected, will be to veto the government’s budget and legislation, even though such deadlocking is permitted under the city’s mini-constitution.) Organizers claim that more than 600,000 cast ballots in the two-day vote, with results favoring young democrats who tend to be more confrontational toward the Chinese government. It’s unclear if these candidates, many of whom protested the new law, will face disqualification or other repercussions.

Read more: ‘One Country, Two Systems Is Still the Best Model for Hong Kong But It Badly Needs Reform‘

“The cost of politics will be much higher than before,” says Tanya Chan, a lawmaker and convenor of the pro-democracy camp. Her book was one of several removed from circulation at the public libraries pending a review. The targeting of her travelogue was “puzzling,” she says, though she expects that “sooner or later” this law “will affect almost every aspect of our normal life.”

Some groups have preemptively disbanded. Demosisto, the youth political party founded by prominent activist Joshua Wong, ceased to be on the same day the law was enacted, while other upstart political organizations relocated overseas.

Nathan Law, a co-founder of Demosisto—and frequently vilified in Chinese state media as a conspirator of foreign governments over his lobbying for U.S. sanctions on Hong Kong—went into self-imposed exile in London a day after he testified online to a congressional hearing.

“It has created a chilling effect,” says Law, “and destroyed the Hong Kong that we used to know.”

But for some, exasperated by the violence and disruption of last year’s protests, the law brings welcome tranquility back to Hong Kong’s streets.

Ronny Ng, a 52-year-old IT professional, says he was tired of not being able to go out or get to work as protest after protest transformed his neighborhood into a battlefield. “If you’re not against the government or against China, the new law won’t be a problem,” he says while on a cigarette break outside his office. Those who are, he admits, “should probably leave if they can’t adapt.”

Chan Long Hei—Bloomberg/Getty Images Blank sticky notes are displayed inside a restaurant in Hong Kong on July 8, 2020.

Among businesses in the financial center, reactions have been mixed. After the details were revealed, a survey by the American Chamber of Commerce showed the majority of U.S. companies operating out of the hub were increasingly concerned, especially about the law’s ambiguity. Yet an exodus seems unlikely, with 51% of respondents also expecting it would have either no effect or even a positive effect on their operations, given the suspension of protests.

Still, resistance hasn’t been fully extinguished. Demonstrators have already found cheeky ways to circumvent the law, like using numbers, acronyms and homonyms instead of the words in the outlawed protest chant. The Post-it Note walls have returned, although they no longer carry any messages. Blank paper has become the latest marker of defiance. So too have the opening lines of China’s national anthem: “Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!”

Ahead of the new law’s implementation, some journalists and academics had predicted the “death” of Hong Kong. But Yam, the film producer, insists this not the end of his beloved city.

“I’ve never seen Hong Kong so vibrant in a way,” he says while on a lunch break during one of the last days of filming. “It turns out we really want freedom.”

from Blogger https://ift.tt/3jDhSP6

via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Museums & Digital Black Lives Matter Activism

Any institution with a platform has a responsibility to be anti-racist. In these increasingly digital times, hashtags are an important tool in showing support. Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa open their article “#Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media and the US” by explaining the significance of hashtags in any modern social justice movement.1 Hashtags reflect a digital arm of a movement that has body parts in both the virtual and physical realms. Many of the observations Bonilla and Rosa made about #Ferguson on Twitter are applicable to #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackoutTuesday on Instagram. These tags link posts together, regardless of the poster’s viewpoint or intent, and allow easy access to these posts by removing them from their original context and lumping them together. 2 The inclusion or omission of #BlackLivesMatter is taken as a political statement by many and has become a criterion for holding institutions, celebrities, and content creators accountable in standing up to racism. In the same vein, a poster’s use of #BlackLivesMatter on an image of a black square shows their lack of awareness, as the millions of black squares rendered nearly all the information on the #BlackLivesMatter tag impossible to find. It is widely recognized among activists that simply posting a black square is not sufficient in using one’s platform, regardless of their follower count. As citizens, we have a responsibility to use our voice and elevate others’ by sharing their posts to our stories and feeds. Digital activism is not the be-all end-all, it is only the beginning. In the case of institutions, their Instagram activity represents the first steps they are taking towards a more equitable future.

This post will examine the ways two very different museums (the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Poster House) engage with Black Lives Matter activism on their Instagram accounts. I will evaluate their activism based on their genuity versus performativity, the #blackouttuesday debacle, and duration of their support.

In a post from May 31, the Met (@metmuseum) posted a picture of Freedom of Speech by Faith Ringgold and was continuously called out in the comments for beating around the bush. One commenter said “Say what you NEED to say [with] your chest. Not these loose allusions or references”.3 The Museum responded with “Thank you, you’re right. We’ve amended our post”, but the caption still does not say Black Lives Matter.4 The Met did include #BlackLivesMatter in a caption on June 1, but the post was a black square that took up space on the hashtag during a critical period of organizing. This is not activism.

In the caption of their black square post, the Met pats itself on the back for the letter it sent to its employees. Regarding social media, the letter says: “We have been using our social media channels to highlight works from our collection that invite reflection on our nation's complicated past and present...We will continue to use social media to contribute to the national conversation, and we hope to respond to these issues thoughtfully in our blogs and other online programming in the coming weeks”.5 Since then, the account has included the work of Black artists in their posts more than they previously had, but not exclusively. On a search of the Met’s website for “Black Lives Matter”, the only relevant result is their Racial Justice Resource Library which contains links to third-party sites and a paragraph long disclaimer, which states that “The Met's inclusion of these websites does not constitute an endorsement or an approval by The Met of any of the services or opinions of the third-party content provider”.6 They have yet to explicitly say Black Lives Matter outside of their unfortunate hashtag situation.

The Poster House (@posterhousenyc) provides a much more responsible example of what institutions can be doing. Keeping in mind that the Poster House (physical location) is currently celebrating its first birthday (compared to the Met’s 133 year history), we see a commitment to justice that is reflective of the period the Poster House was developed.

If the Poster House did engage with #blackouttuesday, they have since deleted the post. Many organizers asked social media users not to engage with this trend at all, even if the #blacklivesmatter hashtag was not used, because it still crowded people’s feeds and led to censorship. The Poster House has a permanent highlight on their page, posted three weeks ago, titled “BLM Resources”. The first slide states “Poster House will continue highlighting posters that speak to the worldwide fight against: -Racial Injustice -Police Brutality -Oppressive Government Systems, As well as amplifying content from BIPOC creators”.7 The second announces a forthcoming program from their Education Department that will provide “a deeper understanding of the history of Civil Rights protests in the USA leading up to the Black Lives Matter Movement”. Comprehensive histories that place the Black Lives Matter movement within the context of racial justice efforts is a worthy and much-needed endeavor.

@posterhousenyc’s engagement with the current Black Lives Matter effort began on May 30, when they posted an Amos Kennedy poster that reads “If there is no struggle, there is no progress -Frederick Douglass”. The Poster House continued to engage exclusively with racial justice posters from then until June 9. After June 9, they began to integrate gay rights posters into their Instagram feed, but have continued to discuss antiracism.

Digital activism is only valid if one’s activism continues offline. The composition of museums’ leadership, their treatment of nonwestern and nonwhite artists, and their workplace politics all contribute to the authenticity of their Black Lives Matter statements.

Yarimar Bonilla and Jonathan Rosa, "#Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media and the US," American Ethnologist, 2015, accessed July 3, 2020. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

@thatgirlyoh on @metmuseum Instagram post. May 31, 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CA3OhwVFSKZ/. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Daniel Weiss and Max Hollein, "Standing in Solidarity, Committing to the Work Ahead," The Metropolitan Museum of Art, last modified June 1, 2020, accessed July 3, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2020/standing-in-solidarity-president-director. ↩︎

"Racial Justice Resource Library," The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed July 3, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/adults/racial-justice-resources. ↩︎

@posterhousenyc. Instagram post. https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/17903462683467377/. ↩︎

#BLM#Black Lives Matter#museums#museum#metropolitan museum of art#poster house#new york city#digital activism

0 notes

Text

Bong Joon Ho’s Path From Seoul to Oscar Dominance

SEOUL, South Korea — Eom Hang-ki’s pizza parlor in the run-down Noryangjin district of Seoul has attracted unusual customers in recent months: movie fans from Japan and even the United States and Argentina, all coming to pay homage at one of the locations where Bong Joon Ho shot “Parasite.”

“I am so happy that my shop played even a tiny role in the creation of the historic movie,” Ms. Eom, 65, said of the film that has become a worldwide sensation and this week became the first foreign language movie to win the best picture Oscar. “But frankly, I was confused at first when foreigners began showing up at my shop.”

The streets of Seoul are as much a character in “Parasite” as the actors themselves, and they played a formative role in shaping Mr. Bong’s politicized worldview and intense focus on the searing inequality in the pulsing city of 10 million people.

Mr. Bong’s relatives have told the South Korean news media that he showed a keen attention to wealth disparities from an early age, bringing poorer friends from school home to dine with him. When he was at Yonsei University in Seoul, students championed the rights of the poor and underprivileged, often going to rural villages as volunteer farmers and teachers during summer vacations or infiltrating work sites to help organize unions.

Mr. Bong moved to Seoul with his family from the provincial city of Daegu when he was a third grader. His maternal grandfather was Park Tae-won, a novelist who ended up in North Korea during the Korean War in the early 1950s and built a prolific literary career there until his death in 1986.

During the Cold War, studying Mr. Park and other “gone-to-the-North” writers was taboo in the South. People were banned from borrowing his book from libraries, and when parts of his works were cited in books and journals, his name was often partly redacted.

Growing up in Seoul, Mr. Bong as a middle school student was determined to become a film director. While studying sociology at Yonsei University in Seoul, he co-founded a filmmaking club.

He also developed what he called a “morbid obsession” with movies, watching old Hollywood classics broadcast every weekend on South Korean TV stations, as well as more sexually explicit and violent films shown on AFKN, a TV channel for American troops in South Korea. He bought his first video camera with savings from selling doughnuts at a school cafeteria.

“I still remember sleeping at night hugging the Hitachi camera,” he said.