#instead of summer parish assignments

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The theology teacher from my freshman year of high school died a few days ago. His kids were both younger than me by more than a few years, and its always a weird mortality check on my family when something like that happens.

He was one of the giants of my high school--a teacher that had legends associated with his name. His class was hard. I credit it with being where I actually learned to type. I got lucky and was the first class that didn't have to prepare a massive animated powerpoint presentation on the book of Exodus, because at that point no one needed to be taught how to use powerpoint. (I would have benefitted from that project, but I'm not complaining that I was spared.) One random day, he would cancel class by surprise and regale us with the story of how he proposed to his wife. And at just fifteen years of age, he assigned a gospel research paper so focused that I had to visit a local seminary college and use their physical library to find information. Exegesis of a pericope anyone?

(I now realize how much this ages me, that I went to a highly specific university library to research a few bible verses, because I couldn't access the necessary resources with the limited online research tools available at the time)

I could wax poetic about tiger amulets, a class known as FARTS, and how I learned about so much more than the Catholic bible from this man, but this is already highly specific. Going to a women's high school meant that we had weird narratives built up around the male faculty, even when they were older than most of our fathers, because there weren't high school boys to distract us. Almost all of them have retired, and three of those men have died.

Adulting is weird and sad, and as much as I was a ball of stress and anxiety during high school, I really love my memories, friends, and experiences and look back fondly on those times in life. It makes me more grateful for the relationships that I've been able to form with some of those same faculty members as an adult.

#adulthood#adulting#looking back on high school#clearly the tiger amulet worked#because there weren't ever any tigers on campus#exegesis of a pericope#this paper was as big as a dissertation in the eyes of the freshman class#my great uncle the priest was impressed by my biblical knowledge halfway through the year#he said I was having seminary-level conversations with him#granted he did seminary in post-WW2 europe and was able to get away with summer motorcycle trips#instead of summer parish assignments#so maybe i should question some of his seminary education#the proposal introduced us all to the idea of a “ro-tic” evening#it's romantic without the man#AKA a selfcare package and VHS tape proposal sent from the states to europe#so maybe he ruined future proposals for every woman who graduated for the 33 years that he taught theology#catholic school#women's school#women's high school#all girls school#catholic high school#all girls high school

0 notes

Text

Starting Out: First days are universally the hardest days...

Day 1: August 13, 2019

I arrived in Uganda around 2:30 PM. It was a long journey (12 hours from New York to Dubai and then another 6 hours from Dubai to Entebbe), but we made it safely. Along the way, I watched movies, journaled, and began to read Melinda Gate’s book, The Moment of Lift.

I was greeted at the airport by Ruth, my host, and her cousin George, who I met on my last trip. After about 20 hours of traveling, I felt extremely comforted by a familiar face. We hopped in the car and made our way back to Kampala.

When we made it to Ruth’s house, it felt entirely different than last time. Everything might have looked the same or similar to what it was a year ago. However, during my last trip, I always had Ysabel, a fellow student, by my side experiencing everything. We had been chosen to work the internship together, live together, and be support sources for each other.

This time, I am on own, and being back in Ruth’s house without Ysabel made me confront that reality. Not only am I on my own, but I am also doing a completely independent project. There is no office space for me to go, no strict 9-5 schedule, and no manager assigning my tasks. I am in charge of finding a space to work, creating structure for myself, and finding people to interview.

I tried to fall asleep around 8:00 PM, but I could not help but feel a little overwhelmed by this reality. “What was I doing here?”, I thought. Doubts, worries, and stressors circled my mind and kept me up. This is often what happens to me when I have to deal with uncertainty. My mind thinks of all the things that could go wrong rather than the plan to make it go right. However, I decided to shut that shit down and play a guided meditation for sleep. Sometimes, when confronted with anxiety, this is the best way for me to get through it. The guided meditation urges you to “give your thoughts permission to leave you to take their own journeys for a while and join you again in the morning”. While this seems like the obvious thing to do after a long journey with limited sleep, sometimes it is helpful to have a reminder to tackle your problems when you are well rested.

I woke up again around 1:00 AM and luckily Maddy, a good friend, was around to call and chat. She heard me out, made me feel comforted, and reminded me that I am up for task. Feeling more secure, I fell back asleep and let my mind and body prepare for the next day ahead.

Day 2: August 15th, 2019

Given my anxieties the night before, I really hit the ground running on my second day. I got up and called a friend around 8:00 AM, I ate a breakfast consisting of mango, pineapple, and a fried egg, and then I took a boda to Acacia Mall to get started.

I first tackled the problem of getting an office space. I visited a local coworking space called Tribe Kampala, where many researchers and internationals come to enjoy fast internet and a productive environment. I opened a membership, set up my WiFi, and sat down to work.

Next, I started to make a real tangible action plan. For my senior thesis, I am investigating the roles and experiences of teachers, administrators, policy makers, and nonprofits in integrating the refugee population into the national education through the Education Response Plan (ERP). I intend to start with the schools because they are hardest to reach from abroad and Ruth, my host mom, offered to drive me to these schools because she does not have much going on during the weeks.

While I had prepared a list of schools that I was interested in visiting before coming, I realized that I had to narrow down my target sample to schools that serve refugees. I had read in numerous reports that mentioned 23 schools with the highest refugee populations, but I was having trouble tracking their names.

I first attempted to narrow the sample down by identifying the subdistricts in Kampala with the highest refugee populations and creating a list of schools within those areas. Then, after four hours of work, by the grace of God, I found a list of schools in Kampala and their refugee count in their student population deep in the bottom of a UNHCR update from 2016. While collecting accurate information of the refugee status of students can be difficult because many children choose not to disclose this information, this was a start. With this list, I began mapping out the schools, tracking down their phone numbers, and creating a plan to visit them starting next week.

After working for quite some time, I headed over to Acacia Mall to buy a phone plan. Unfortunately, I forgot that I needed my passport to register so I had to put this task off for the next day. Instead of doing that task, I went to a café, had a passion juice, and practiced on my mental math to prepare for some case interviews that are looming in the fall.

Around dinner time, I met up with Ryan, a recent Princeton graduate currently doing a Princeton in Africa Fellowship which sets you up to work for NGO or Social Enterprise in Africa for a Year. He is working for Rockies, an organization that scouts a talent from across rural Uganda, recruits them for a performance troop, and pays for their training and schooling. He just moved here in the beginning of August and is already being thrown into work from grant writing to logistics.

We went to Meza, my favorite shawarma place in the world, and chatted about our experiences, our transition, and our lives. Then, we went to Wine Garage, a nearby lowkey wine bar, for their happy hour to celebrate meeting each other and my first full day in Kampala.

I ended the day feeling more confident and positive then before. I realized I wasn’t alone and that I had many contacts and many people I could reach out to. I also realized that I can make a plan and execute on it- it’s as simple as just doing it. I had plan to contact schools the next day and reach out more people.

This time when I got home, I worked a bit more, excitedly showed Ruth the schools, and called my parents and friends to tell them the updates. Things were looking up!

Day 3: August 15th, 2019

Today, was a longer day. I woke up a bit later around 9 AM because I was up until late working on logistics for when I get back to school and start working with the Glee Club. I quickly showered, ate breakfast, and ran out the door.

I made it to Acacia Mall around 10 AM and went to the MTN Mobile Provider Office to set up my local number (finally!) Pro Tip: Always do it at the airport- it might be more expensive, but it’s easier. It took about an hour to get all set up and squared away with a phone number, but I practiced on my mental math app in the meantime. While I wanted to have been watching Stranger Things, the last thing I need right now is more mysteriousness to creep into my subconsciousness. So, instead of watching those pre-downloaded Netflix episodes, mental math it was.

After, I finished setting up my phone. I went to Tribe Kampala and began to make phone calls. The first 10 schools I called either did not pick up or were invalid numbers. Finally, 11 calls later, an administrator told me that I must go through the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) to interview students (yay bureaucracy!!).

With this new development, I called the KCCA to figure out the process to get their approval and introduction to schools. I found out I needed to provide a letter of introduction from my University providing the details of my work. So, for the next hour, I printed and assembled a packet to bring to the KCCA. I then took a safe boda to the KCCA, walked into their massive complex, and was directed to the department of education for approval. I handed her the packet, explained my time crunch (only 3.5 weeks), and she told me that I can expect to hear back from tomorrow with her feedback (Please say a prayer for this to work out). Despite this bureaucratic bump in the road, I am positive that it will all work out and that I am taking the steps in the right direction.

After this, I had a call with an associate at a consulting firm to learn about her experience and gather her advice. I also read a chapter in my Casebook and practiced more mental math (shout out to my sister if she’s reading this).

For dinner, I met up with Rosette, a former coworker of mine from the Bayimba Cultural Foundation, where I worked last summer. She has since left the organization and is on her way to the next thing in life. Here is a bit about her life because I think she is a power house and we all can learn from the way she walks purposefully through life and always demonstrates her value:

She is the daughter of a diplomat, who recently passed away, and majored in tourism in her undergraduate education. She had always been interested in theater and drama starting with her work at her local parish where she led the Christmas Cantatas and taught Sunday School through drama. While working at Sunday School, a leader in the church took notice and offered her a job as her project manager. She worked there for a while, but after being dissatisfied with inconsistent pay, she looked to move on.

It was around then when she made a close connection with the woman who would always write the Christmas Cantatas. She impressed the woman by tidying up her place and offered Rosette an administrator job. While she was happy at this job, she both lived and worked with this woman which made for difficult boundaries. It was around that time when she started going to the Bayimba Festival and connecting with their founder, Faisal. She became their part-time workshop coordinator as she continued working for the other woman often working early mornings, late nights, and traveling on the weekends for the Bayimba events across the country. After doing this for a period of a year, she realized that she had to get out and move on her own. Around that time, she met three international women hoping to rent out their place while they would be away. Despite not having the money at the time, she demonstrated her interested and moved forward with the opportunity.

After working hard at Bayimba, the team there began to take notice and offered her a full-time position when the funding came in. She then was able to move out of the old job and house and start this new career with Bayimba. For the past 9 years, that had been her life. She worked as the coordinator for the Bayimba Academy- organizing workshops, inviting guest artists from around the world, and helping develop the young talent here in Uganda.

Just this May, she resigned from Bayimba and began to take the steps towards her next phase in life. She is hoping to improve her education and eventually work to improve the channels for cultural exchange across the world and open people’s minds up to the broad arts landscape that is out there. She is brilliant, strategic, and has had so much faith and courage over her life. I am excited for her next adventure.

Rosette and I talked for hours and she connected me with some music educators that serve refugee populations across Uganda who I will try to interview. She is one of those amazing individuals that leave you speechless at times.

Now, I am in my room in bed at Ruth’s house next to the Oryx Petrol Station on Bukoto-Kisassi Road. I am exhausted, but so excited and ready for what will come tomorrow.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

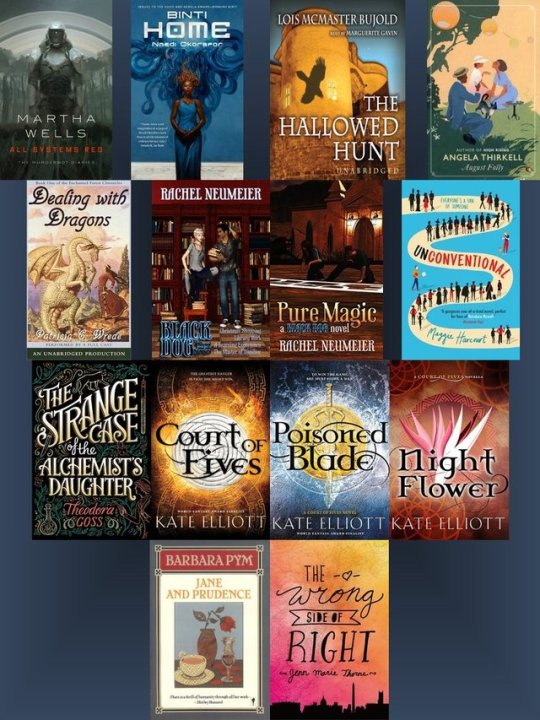

Books read in July

I had more time to read, but I also read a few novellas and rediscovered audiobooks.

It occurred to me a few years ago that an audiobook makes housework less tedious, but back then the library often didn’t have books I wanted as audiobooks, and there was inconvenience of lugging around a CD player or transferring umpteen CDs to my iPod. Now my library now has a good range on Overdrive, and being able to borrow audiobooks online and download them straight to my phone makes finding and listening to them so much easier. It’s amazing.

I’ve asterisked my favourites.

(My longer reviews and ratings are on LibraryThing.)

* The Murderbot Diaries: All Systems Red by Martha Wells: Told from the perspective of the Security bot assigned to a team surveying an uninhabited planet. The self-dubbed “Murderbot” avoids arousing suspicions about its hacked governor module and its binge-watching habits. But when things start going wrong, it has to work much more closely with its human clients than it would prefer. AI-with-feelings is one of my favourite things, and this particularly AI is delightfully grumpy and introverted. But this doesn’t just have an entertaining narrator, it also has a high-stakes mystery and some decent humans, and the combination is amazing. Well and truly exceeded my expectations.

Binti: Home by Nnedi Okorafor: After a year at university, Binti returns home. It’s a difficult homecoming, because not all of her family approve of her decision to go to university, and Binti’s plans of undertaking the pilgrimage that will mark her transition to becoming a Himba woman are disrupted by revelations about her heritage from her father’s side. An interesting, unusual story about culture, identity, prejudice and technology. It ends with a lot of things unresolved, in a cliff-hanger-y sort of way that strongly suggests the story isn’t over.

* The Hallowed Hunt by Lois McMaster Bujold (narrated by Marguerite Gavin): A gripping story with unusual worldbuilding, set in the world of the five gods. Lord Ingrey, sent to retrieve Prince Boleso murderer, becomes convinced that Lady Ijada was acting in self defence - and that no one else will accept that. Things quickly get much more complicated, and Ingrey and Ijada become tangled in mysteries about the past and the gods’ plans. I’m very glad I listened to the audiobook! The narrator highlighted the amusing moments, and I suspect I became much more attached to the characters as a result of experiencing their story more slowly. I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this as much as I did.

August Folly (1936) by Angela Thirkell: A summer of dinners, donkey rides, rehearsals, train journeys, cricket, secret worries, siblings and romance. When Richard Tebbin comes down from Oxford, he’s moody, awkward and self-absorbed - and becomes promptly besotted with the much older and married Mrs Dean. This is not a situation I’d consider delightful or charming, yet I was captivated. Thirkell astutely portrays family dynamics, with their various tensions, and many of the characters have complexities or contradictions, and show unexpected depth, strength or growth. I’m very glad I didn’t skip this one (in spite of the odd and unnecessary, but fortunately brief, references to prejudiced attitudes).

Dealings with Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede (unabridged dramatisation): Cimorene has no interest in being a traditional princess. When her parents attempt to arrange a suitable marriage for her, she defies convention by running away and volunteering to becomes a dragon’s princess. This story combines dragons with the of subversion of fairytale tropes, so I’m surprised I didn’t become more invested. I don’t know if this was due to the dramatisation or the story itself - Cimorene is so capable and content with her circumstances it’s hard to connect with her. Or maybe this is simply one of those books I would have appreciated more fifteen years ago?

Black Dog series by Rachel Neumeier:

Black Dog Short Stories: A collection of short stories, mostly set just after the events of Black Dog. All of them involved more action than I was expecting. I enjoyed them, especially the backstory in “The Master of Dimilioc”.

Pure Magic: The black dog community of Dimilioc has dealt with one threat, but they have other enemies out there - and things really don’t go to plan. The result is very tense with very high stakes, and I couldn’t put it down. Dimilioc’s reluctant new member, Justin, grew up unaware of his magic and knowing little of black dogs. I appreciated the different perspective he brings. Unlike Justin, Natividad’s very certain she wants to be part of Dimilioc - but is still getting her hand around what that actually means. I liked how the story ultimately deal with her agency and her disobedience.

Unconventional by Maggie Harcourt: Lexie’s father runs six fan conventions every year, and Lexie is right in the thick of it. As a look at the friendships and chaos behind the scenes at conventions, Unconventional is engaging and reasonably lighthearted. However, because the focus isn’t limited to convention shenanigans, the story loses something by never properly showing Lexie’s life beyond convention weekends. A couple of issues feel resolved too easily and some of the conclusions Lexie reaches feel a bit... artificial. I was disappointed that it was almost-but-not-quite something with more depth. Still, it’s fun and fannish.

The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter by Theodora Goss: A mystery set in the late 19th century, in which most of the characters are borrowed from, or are the offspring of characters from, 19th century Gothic and mystery fiction. I’d read most of those stories and was delighted to see them all woven together like this. It’s all very meta in a way I really appreciated. After her mother dies, Mary Jekyll tries to find her father’s murderer. Instead she becomes involved in Holmes’ investigation into murders in Whitechapel and meets several highly unusual women with connections to the Société de Alchimistes. And together they write their own story.

Court of Fives trilogy by Kate Elliot: In postcolonial Efea the Saroese Patron class are forbidden from marrying Efean commoners. As the daughters of a Saroese army captain and his Efean lover, Jessamy and her sisters, occur a precarious place in society. But that hasn’t prevented Jessamy from sneaking out and training to compete in the Fives. When her family’s circumstances change, she has to use all the skills to protect those she loves.

* Court of Fives (narrated by Georgia Dolenz): I loved this. The narrator is excellent - Jessamy and her sisters are so lively and believable - and the story’s absolutely gripping. I stayed up much later than I should because I was so worried for the characters! Jessamy’s impulsive high spirits and interactions with her sisters reminded me of Jo March from Little Women. I love that Jes’s relationships with her family are the heart of the story, and that she develops a more nuanced understanding of her parents’ choices. She also realises how they’ve sheltered her from challenges others face.

* Poisoned Blade (narrated by Georgia Dolenz): Jessamy has always dreamed of competing as an adversary in the Fives - but not when her victories are ordered and used to advantage by the man who tore her family apart. As Efea’s political situation crumbles, Jes becomes more aware of its complexities and of her unique position with loyalties to people from both classes. Frustratingly yet understandably, she takes a lot of risks - she’s learnt she’ll never win by playing it safe. I love how Jes’s relationships with her family remain central to the story, and how believably complex and strong-willed they all are.

Night Flower (prequel novella): A cute story about how Jessamy’s parents met. It’s interesting seeing them as young people newly arrived in the city - moreover, seeing them as they see each other, not as their daughter perceives them twenty years later - but I was a little disappointed it didn’t show more of their relationship. I wanted to read about the point where, with a more thorough understanding of each other and of the sacrifices their relationship will involve, they chose to build a life together.

Jane and Prudence (1953) by Barbara Pym: Charming but it is also unromantic and sometimes uncomfortably astute. Jane and Prudence are friends who met years earlier at Oxford as a tutor and a student respectively. Jane is a vicar’s wife, adjusting to life in a new parish; Prudence is twenty-nine and unmarried, working in a London office. I appreciated that Jane is not particularly good at some things, like running an efficient household and yet is accepted as she is. Jane and Prudence’s friendship is also realistic and refreshing - they don’t always understand each other, but their friendship has persisted despite their differences.

The Wrong Side of Right by Jenn Marie Thorne: Kate is a teenager who has grown up knowing nothing about her father. After her mother dies her father’s identity is unexpectedly revealed. He’s a senator, with a family, and he’s running for president. As the campaign progresses, Kate has to decide how much is she prepared to pushed around, and what she will do when she doesn’t agree with her father’s politics.A few odd details initially struck me as a bit unrealistic - but I read the rest in one go. It satisfactorily addresses my quibbles, and finds the right balance between lighthearted and heartwarming.

#Herenya reviews books#Herenya recommends things#Angela Thirkell#Rachel Neumeier#Court of Fives#Barbara Pym#Kate Elliott#Theodora Goss#Lois McMaster Bujold#The World of the Five Gods#Martha Wells#Murderbot#Nnedi Okorafor#Patricia C. Wrede

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss Black people

A tall Black man came into the office in Christmas Valley last week to introduce himself as a social services worker for parts of Deschutes County and north Lake County, too. My door and my fellow therapist’s door were open, and we introduced ourselves and chatted amicably. When he and I discovered we had both lived in DC, I became Chatty Cathy, waxing poetic about Ethiopian Food. It became clear that he wasn’t that familiar with it, couldn’t remember the word ‘injera’… but that was okay. I was talking to a Black man who knew DC. I’m pretty sure I embarrassed myself. My colleague was friendly and professional. I was irrationally glad to see him out of all proportion to the occasion.

He probably left thinking to himself, white people are weird. Guilty as charged.

I am one of those white people who study Black people. Their experience, history, personalities, and the systemic, systematic way in which they’ve been imprisoned in one big internment camp called the United States of America. Everything about them, with the possible exception of current music beyond a superficial point. My kids listen to nothing but music made by Black people, so we, as a family, have that covered.

Formative books: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The Color Purple. Beloved. Also, Why do all the Black kids sit together in the Cafeteria, and When Race Became Real. Between the World and Me is the most recent.

Formative movies: Sounder (with music by Taj Mahal). Anything by Spike Lee (with the possible exception of Inside Job, which is excellent, but not about Black experience.) Moonlight. Daughters of the Dust. I am Not Your Negro is the most recent. Anything by Ava DuVernay, most recently, 13th. (I dare you, white reader, to watch it, on Netflix, and not have your mind blown.)

Music: Otis Redding. Songs in the Key of Life by Stevie Wonder. Early Michael Jackson and the Jackson Five. Tracy Chapman. India Arie.

I could go on and on… Perhaps I’ll stop with this link to 100 Woke Black women to follow: http://www.essence.com/news/woke-100-women

“Study” does not mean to keep at arms-length. I have been a marshmallow in a sea of cocoa since I can remember being alive. And since, many times, in different schools and neighborhoods, I was one of the few white kids, it behooved me to observe how we are similar and different. When you are the minority, you study the majority.

Little differences, in hygiene practices (Black women are more fastidious), in pronunciation (Andrea is pronounced An DRE uh by Black folks, AN dreeah by white. Darrell is DaRELLE for Black people and DAR rul for white.) In Happy Birthday songs: Black folks sing the Stevie Wonder version. In mythical secret jokes. Some Black people think that white people smell bad when wet. I’m serious. Based on how stinky the white men were when they came across the Atlantic to kidnap Black people. I mentioned this one day to a church friend, a PhD in Math, descended from Jamaicans, and she gasped! How did I know?! (I read it in a book, silly.)

I notice how much African American Vernacular English is used by white people. “You go, girl.” “24/7.” “I’m down.” “Word.” White folks don’t necessarily notice. I do. I try not to use AAVE. For fear of being scolded by my daughter. But also, because it is not appropriate. I struggle with this appropriateness thing. Because it’s the right thing to do. I keep learning how much culture has been stolen from Black Americans. Elvis Presley is just the tip of the iceburg. White people have stolen from Black people for millennia, and not just culturally. I look for examples of this, and find it, daily. I look out of long habit, so that I can give credit where credit is due.

It is absolutely true that Black people have transformed my life again and again. A Black 10th grade English teacher told me I was a good writer and should check out the Urban Journalism Workshop. I did, I applied, I got in, I learned to write, and the article I wrote earned an honorable mention from the Robert Kennedy Journalism awards. It was about the gentrification of Mount Pleasant, a neighborhood in DC. In 1976. I’m pretty sure I got into Oberlin College because of the Urban Journalism Workshop. Because I had zero extracurriculars besides running away from home. Thank you, Mrs. Feely.

I spent 40 years in the grooviest episcopal church on the planet (IMHO) because of a Black seminarian I almost married. He was 9 years my senior, I was 17, when we met. St Stephen & the Incarnation became my spiritual home because he was assigned there. And after I realized I was too young to marry, it stayed my parish home until I moved to the Oregon Outback in August 2016. Thank you, Eddie.

I miss my Black friends. Gay and straight women, with a few gay Black men in there, too. I know a lot of wonderful straight Black men, but I can’t say I’d call any of them in the middle of the night to take me to the emergency room. (One of my criteria for being a real friend. I’m sure they’d take me; I would just be so embarrassed.) Each of my friends is amazing. Of course, that is also true of my white friends. I’ve been mulling over the difference between my white and Black friends.

I’m reminded of something I read years ago about being friends across the racial chasm: the Black woman’s advice to her white friend was, “Forget I am Black. And, never forget that I am Black.” The zen koan of being friends with a Black person.

I feel lucky when a Black person will deign to be my friend. They could so easily reserve their precious energies for other people of color, especially people of the African diaspora. Out of self-care. (deign: verb, do something that one considers to be beneath one's dignity. "she did not deign to answer the maid's question" Archaic condescend to give [something.] "He had deigned an apology.") When I am hanging out with my Black friends who are activists and seemingly tireless in their work for justice in all kinds of situations, I am amazed that they have time for me. I know in fact that they are tired. And I do my best to be someone they can relax with. Even though I am white.

I have a Black friend who grew up in Crown Heights Brooklyn, where my son lives now in an apartment with many roommates. Her parents were from Guyana, an African-Caribbean country. Crown Heights is gentrifying, but it seems to still hold a special mix of Caribbean immigrants and Hasidim. S is a little younger than I am, and also has 2 kids, one in college (same one as my daughter) and the other graduated (as is my son.) My kids’ dad and I met their family when we each had only one baby in diapers and one parent each were home, and craving adult conversation. Play group in Brookland DC used to meet once a week until the community-organizing father of my children got hold of it, and then it met 3 times a week.

Our oldest boys were friends. We had second children. We developed a tradition of going to the Outer Banks in North Carolina for a week every summer and sharing an old beach house that was right on the water, one family per bedroom. We’d have 4 families give or take, and take turns cooking, looking after munchkins, and going on field trips to the Wright Brothers Museum, Walmart, and movies.

When it was time to figure out where to have the oldest boys go to school, our two families combined forces. In DC, finding a decent public school requires a strategy. We got pretty elaborate: what are our criteria for excellence? How much did each value weigh in the decision? We teamed up, with S and I spending the night in her car one icy January to get on the list for a popular bilingual Spanish/English immersion school (Oyster Elementary). My kids’ dad and her husband hit a number of schools that were apparently much less popular but still made our list. My kid got into Oyster, and S, who was right after me, did not. We decided that our boys would go to a DC public Montessori program instead of risking separation.

By the way, S met a nice Jewish young man from Iowa when they both attended Harvard, and married him. After many years, she decided to convert to Judaism, and both boys had bar mitzvahs, which were very cool to attend.

Both families switched to another DC public Montessori program when the original one seemed in steep decline, and enjoyed that community for a while. It became clear that my son wasn’t doing as well in that context, so I got him on a waiting list for a phenomenal charter school that uses the Expeditionary Learning model (affiliated with Outward Bound.)

We remained friends as families, going to the beach, joining the pool just over the DC line that many Brooklanders belonged to. Our boys grew apart, but we still hung out. One amazing bit of fate is that it was S and her son who introduced my boy to film-making at around 6th grade. He now makes his living as a filmmaker and is a Tisch film school graduate.

S is one of those women who is rather butch, and also straight. She is not femme: never wears make up, keeps her hair very short for minimum of fuss, and never wears skirts or dresses (except in her wedding.) I taught her to knit on one of our beach weeks, and she’s gone on to become expert and imaginative. I figured out at one point that I had a crush on her, but I stomped that out, and we have had a great 20+ year friendship.

When my marriage ended, S and her husband extended dinner invitations to both me and my ex, separately, but only I responded. My ex is introverted, and for some reason he let his connection to these folks wither. I was grateful to hold onto the friendship, and enjoyed coming to their house for amazing food prepared by Ed, the son of the Iowan baker. Lots of far ranging conversation. We’d solve the problems of the world, and then I’d go home. We also share a love of movies. I had to call Ed once to get me to an emergency department, and he did with calm kindness.

Neither S nor her husband are on Facebook much, which is where I keep in touch with most of my social connections from DC. I’ll have to actually write them a letter, which I used to do routinely. I miss these people very much. Maybe I should just call them up. How novel.

S was my friend first, and Black incidentally.

B became my friend and her Blackness was way more prominent. Whereas S never uses AAVE, B uses it a lot, and with her I feel like I can say “GIIRRRRRLLLL” in greeting.

B is from a large African-American Catholic family, originally from Florida. Old school Black, which is to say, ancestors enslaved and brought to the mainland United States, then reared here after Emancipation, and always in the minority. Whereas Island folks, from what was formerly known as the West Indies, were also enslaved, they freed themselves from colonial power, and became majority Black countries. B taught me that some Caribbean folks look down on the old school Black folks. I learned a lot about hierarchies within Blackness from Brigette.

We met at a card game for women in our neighborhood. Her son was a year older than mine, and she lived within a block of us. I started to pursue her as a friend; we attended a Black-taught “all sizes welcomed” yoga class in the neighborhood, and would walk there and back every Saturday morning. On those walks we got to know each other.

She is so accomplished; a law degree, an all but dissertation PhD drop out, an author, a management consultant, a philanthropist. I was honored to be the one white person present for a discernment committee she gathered, Quaker style, to help her make a decision. She influenced me a great deal. I hope I was a good friend to her. She was, probably still is, extremely busy, always, involved in one justice-promoting effort after another. I felt like a slacker in her presence. And she was not judging me. She simply lived every waking moment as an opportunity for social change. I also know there is pain underneath that activity, not just ‘post-traumatic slavery syndrome.’ Our sons are out in the world making art. She is making change. I miss her.

There are many others… Imani, D, Isaiah, Fern, Paulette, Liane…and powerful Facebook friends... Claudia, Alan, Reuben, KM

When I see a Black person out here in Oregon, I am riveted and try not to stare. Black people in white places are used to this, it is the ‘white gaze’, just like women are conscious of the ‘male gaze.’ For the observed, this vigilance is automatic and barely conscious until there is a perceived danger. Is that man (of whatever color) following me down this street? Is that white woman following me in this store? I regret that I am adding to this vigilance for people of color in Oregon.

In Eugene Oregon at a huge hippy extravaganza called Country Fair, I took to counting Black people. Less than 20. I follow the SURJ-Eugene Chapter on Facebook. It’s the closest chapter to where I live. (Standing up for Racial Justice is a white person’s organization that hopes to support Black Lives Matter efforts. White folks can ask other white folks to call each other out and help each other grow. This is not the job of Black People.) Oregon is a very white place.

I am an anti-racist organization of one. Which is not to say I am the only one who cares about racism against Black people, systemic and individualized here in Lake County. I have not yet met anyone as steeped as I am, but it’s always possible. (Where are you?) Anybody out here willing to start a book club to read Witnessing Whiteness? It’s for white people who want to reveal and counteract the racism that lives within all of us.

From the context of my upbringing, and my choice, the collective and multi-hued Black American World is my north star. The Black/white conversation, the current animosity, the centuries-long history, is my cosmology: “noun, the science of the origin and development of the universe.” My social universe. The foundation upon which I build my politics, my theology of justice, my self-image. My corrective. Also, my joy.

I am a white person who works on her racism. Even when there are no Black people in my Oregon Outback world, except a phlebotomist, one former client, and the girlfriend of another. My moral universe is constructed around the fact of the injustice of slavery and its current unjust sequelae. (Noun. se·que·la. a condition that is the consequence of a previous disease or injury.) Part of the post-slavery curse is the anti-government bias that is ripping further the tattered safety net. It is hard work to help white folks in mostly white contexts to see how anti-Black racism seeps into every bit of politics and also harms them individually. I’m working on this. I find it exhausting when the occasional conversation starts with “I don’t have a racist bone in my body.” I was so spoiled in D.C.

Yes, I believe in reparations. TaNehisi Coates’ work on this in The Atlantic is a paradigm-shifter. (https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/)

I only recently read a book on the native American experience, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s epic, “An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States.” Now I can include the injustice wrought against native peoples into my cosmology. Except I did not grow up as a white person in a majority First Nation context. A whole new arena to familiarize myself with. First Nations are deeply relevant to life out here due to water rights. (You can watch Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz read from the book here: https://youtu.be/Pn4QTS6S3WU.) And you can read about water rights and the Klamath Nation here: (https://www.rotary.org/en/rotarian-helping-klamath-river-dispute)

I will continue to be a Black-identified white woman living in Whitelandia. I will try not to be obnoxious when I hear something flatly racist, although I will counter it. Someone said something about Black on Black crime early on. I said something, and now she knows I’m a ‘liberal.’ I share about Black experience on Facebook because I rejoice at the artistry and profound accomplishments of people who Overcome, every day. Maybe my new friends in Oregon will have a couple of stereotypes dashed by following my Facebook posts. Maybe not. Some of the clients at our mental health center are white ex-offenders with Aryan nation tattoos. Lord, make me an instrument of thy peace.

My job is to enlighten white people, somehow, with humility, because i know next to nothing. I need to tell the truth, but tell it slant, as Emily Dickinson wrote, so the truth will dazzle gradually. My job is to live with integrity wherever I am, as inclusively as possible, mining my own deep veins of ignorance (see, Native American History, also, the racist history of Oregon vis a vis Sundown laws, et al.) Counteracting the deep ignorance of the public discourse about the roots of our current politics in my own thinking. And praying to know how to be a bridge builder.

Written on the immensely tall wall of the Lincoln Memorial are words from the 2nd Innaugural address. To quote Wikipedia, “Lincoln suggests that the death and destruction wrought by the [Civil] war was divine retribution to the U.S. for possessing slavery, saying that God may will that the war continue "until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword", and that the war was the country's "woe due".’ What I believe is that the great Civil War in the USA right now is the price we are paying for the sin of slavery, the divide of have and have not, early white immigrant/imperialist versus newer immigrant especially from South and Central America, the disconnect of white republican voters-for-trump and the fact of their deep dependence on the government. My cousin, President Lincoln, (4th cousin, 5 times removed) was more right than he knew.

I will be an ally no matter where I am, however (deeply) imperfect. I can’t help it.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

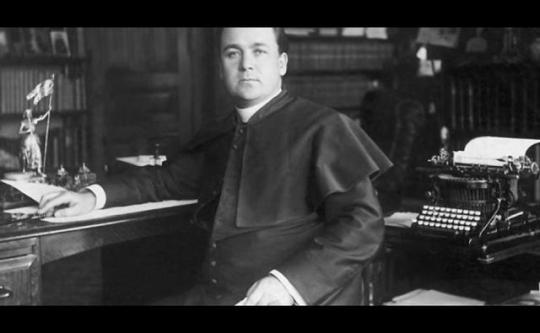

The American Apologetics Giant You've Never Heard Of

Among the ports of call on this summer’s Catholic Answers Cruise and Pilgrimage (June 3-10, Montreal to Boston) is Prince Edward Island, best known to Americans—those who still read books—as the setting of the Anne of Green Gables novels and the birthplace of the author, Lucy Maude Montgomery. Prince Edward Island is also the birthplace of one of the greatest bishops in the history of the Church in America, Francis Clement Kelley (1870), founder of the Catholic Church Extension Society and second Bishop of Oklahoma. From the first he excelled at writing and would go on to publish 17 books, then became a Catholic priest.

Ordained a priest for the diocese of Detroit, Michigan, Fr. Kelley’s first assignment set the spark to the tinder that fired his life’s work. The Lapeer, Michigan parish “spoke of a cold calculating indifference to God.” The culprit was the previous pastor, removed for apostasy. The 22-year-old Fr. Kelley rallied his disillusioned parishioners with sermons rich in doctrine and delivered with clarity and wit. Under Kelley a brick-and-mortar building project began in earnest but stalled while the young priest donned his country’s uniform in 1898.

“No one could have had a stronger conviction that the war with Spain was not only unjust but unnecessary,” Kelly later wrote, but as an Army chaplain he was able bring the sacraments to soldiers mired in the tropical heat, bad sanitation, snakes, mosquitoes, and fever of Tampa and Huntsville.

Writer and apologist

Returning to Michigan, Fr. Kelley joined the Lyceum circuit, and his honoraria funded the construction of his parish. His audiences ranged from “small boys throwing peanut shells” to “old ladies who looked with disapproval at the first Catholic priest they had ever seen while wondering how he concealed his horns so cleverly.” Fr. Kelley came face to face with middle America gathered in meeting halls, red schoolhouses, vacant shops, and tents. He witnessed the miserable living and working conditions endured by Catholic priests “among the scattered people and the churchless places” of the American West and South. He resolved to found a home mission society to bring the Faith to the many regions of America overrun with poverty, prejudice, and ignorance.

A column for Ecclesiastical Review of Philadelphia launched the Catholic Extension Society. Reprinted as a pamphlet, Kelley’s “Little Shanty Story” described the ramshackle rectory of a Catholic pastor in Ellsworth, Kansas. The pamphlet captured the hearts of Catholics across the Republic and in poured donations. One captured heart was that of Archbishop of Chicago, James Quigley. And within a year Kelley’s bishop gave him the Exeat to transfer to Chicago where the Catholic Church Extension Society was formed shortly before.

Kelley excelled as a fundraiser, but his public candor about the lack of missionary spirit in the American seminaries and his scathing criticism of the American hierarchy’s neglect of Catholic rural America made him East Coast enemies, including the papal delegate, Archbishop Diomede Falconio. Quigley stuck by Kelley and arranged meetings for him in Rome to obtain Vatican approval for the Society. To Kelley, Pope Pius X was, “a saint who saw no obstacle to holiness in the possession of a fund of humor” but it was the pope’s Secretary of State, Cardinal Merry del Val who was “the first great and powerful Roman friend of the Extension Society.” He instructed Kelley, “in the science of untying hard diplomatic knots,” lessons the priest would apply throughout his life. Del Val secured a Papal Brief of Approval for the Extension, largely silencing Kelley’s critics.

Apologetics was central to the work of the Extension Society, and when a chapel car rolled into town, one especially popular feature was (then as now) the question box. Before a priest of the Extension would deliver a lecture or offer Mass, he would field questions about the Catholic Faith, often from Protestants or Mormons. Some questions derived from innocent ignorance: one woman thought that Jesus Christ had brought the Bible down from heaven, whole and entire. Other questions were the result of the Ku Klux Klan’s anti-Catholic propaganda: “Is it true that a priest has to murder four people before he can be ordained?” “Do priest really have hooves like cows instead of feet?” A priest visiting a town in Oregon took off his shoes and socks to settle the matter.

Father Kelley’s rolling chapels restored the sacraments to countless fallen-away Catholics all over rural America. Extension Society priests offered each of the sacraments and the Mass throughout the West, Midwest, and the South. In the many towns where the rail cars planted the seed of the Faith, chapels and churches sprang up, supported by Extension Society dollars and constructed by the faithful who had returned home.

Kelley helped finance the work of the Extension with his Extension Magazine, which at its peak boasted half-a-million subscribers. A Catholic version the Saturday Evening Post, the quarterly spread the word about the Society’s work, thereby attracting donations. Extension Magazine also included articles in apologetics, poetry, and short stories, including scores of mystery stories penned by Kelley himself.

Books to politics

So popular was Extension Magazine that when America entered the First World War, Kelley received the offer of a substantial bribe in exchange for an editorial endorsing Woodrow Wilson’s interventionism. Kelley declined, passing up “his one and only chance to become rich” and penned instead, The Pigs of Serbia, a scathing rebuke of the war and its promoters on both sides of the Atlantic.

American meddling in the affairs of Europe was not the only U.S. foreign policy that provoked Fr. Kelley’s anger. “The Mexican Question”, mishandled by administrations from Taft’s to Coolidge’s, became, a focus of Kelley’s life, and perhaps the one for which he is best known today. The resulting book, Blood Drenched Altars, is his only work still in print. The volume argues that Mexico under Spain was a glorious Catholic country, culturally superior to the United States well into the 19th Century: “They dotted the land,” wrote Kelley, “with architectural triumphs which to this day have not been equaled in the Americas.”

Father Kelley’s fight for the soul of Mexico took him to the corridors of American power, striking up dramatic conversations with William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of State, and a meeting with Wilson himself about American’s unwillingness to get involved in the atrocities in Mexico.

The diplomat, and bishop

After the First World War, Fr. Kelley took his crusade for the Church in Mexico to Versailles where he proposed a “liberty of conscience” requirement for any nation desiring membership in the League of Nations. Kelley’s amendment was a matter of practical politics, and a wise one, not a theological proposition. Yet, as he later observed, at the modern world’s official gathering of liberalism, a chief tenet of liberalism, religious freedom, was given no quarter, scuttled by Clemenceau and Wilson.

The time in Paris did bear fruit. Kelley used his skills in practical diplomacy to help achieve a just resolution of the “Roman Question.” The Vatican had lost her lands and sovereignty to the Italian revolution. Kelley proposed a territorial concession, access to the sea, and recognition of sovereignty. Ten years later, the substance of Kelley’s plan was approved by Mussolini, and the sovereignty of the Holy See was restored and secured.

In June 1924, a man who had been a sailor, soldier, scholar, orator, mission priest, political adept, international diplomat, and published author with a prose style praised by H.L. Mencken, was ordained the second bishop of Oklahoma. The mission priest was now a mission bishop, establishing the Faith on the plains, and bringing a new diocese to maturity.

Francis Kelley’s life shows how dogged determination, a devout prayer life, and a profound humility can together achieve great things for God. “The thing was God’s, not mine. If he wanted a fool or a child to do it, that was his business. He had his way of picking over poor material and working it over to suit his purposes. I was quite sure that I was poor material. But why worry? The skeleton of a failure often marks the beginning of a right trail.” Bishop Francis Kelley was far from a failure, but he did understand what St. Teresa of Calcutta would later observe: “We are not called to be successful; we are called to be faithful.”

Catholic Answers President, Christopher Check invites anyone who would like to join him this June on a visit to Bishop Kelley’s birthplace: CatholicAnswersCruise.com. He recommends Kelley’s autobiography, The Bishop Jots it Down, and Francis Clement Kelley and the American Dream by Fr. James P. Gaffey (in two volumes), both regrettably out of print.

#Catholic Answers#Christopher Check#Catholic Answers Cruise#Bishop Kelley#The Bishop Jots It Down#American Dream#Catholic Apologetics

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

Boeing B-17E Fortress 41-9045 'Stinky' by Batman_60 Via Flickr: July 25, 1942, Iceland - 2nd Air Base Group personnel change the #3 engine on an Icelandic summer day (20+ hours of daylight and a mild 55-60 degrees). American Air Museum in Britain: "...Assigned 414BS/97BG Polebrook 3/42; transferred 92BG Bovingdon 24/8/42; crash landed Agricultural College, Athenry, Ireland, near Galway Bay, 15/1/43 ex N/Africa after taking part in 1st Prov Grp of Gen Brereton in Eritrea (as No 8.). En route Portreath, Cornwall with Tom Hulings, Co-pilot: Jim McLaughlin, Navigator: Clyde Collins, Radio Operator: Larry Dennis, Flight engineer/top turret gunner: Ed Parish,Tail gunner: Sgt Tucker plus passengers:-Generals Barnes, Palmer, Brooke, Col Sexton, Major Hormelnwere, Capt Rawlings, Sgts Pippin, Herrie, Planchard, Bery, Tocer and Bollard (18 Returned to Duty). Aircraft was dismantled and returned to USAAF base at Langford Lodge. Salvaged. STINKY, aka TENNESSEE BELLE..." - Baugher: "...The forced landing in neutral Ireland (due to navigational errors) could have been very embarrassing as the aircraft was carrying Lt Gen Jacob Devers and his staff who were on a fact-finding tour of the ETO! The Irish authorities should, by international law, have interned them; instead, they were treated to an impromptu banquet and were transported to the border with Northern Ireland!

1 note

·

View note

Link

His story was one of thousands.

“It happened in the wee hours of the morning,” a Pennsylvania man wrote in a letter to the Diocese of Pittsburgh in 2008, describing the moment he tried to take his own life. He’d spent the night drinking heavily, “which my doctors have explained may have induced an inescapable episodic flashback of sexual abuse, which has haunted me over the years.”

His alleged abuser, Rev. Richard Dorsch, was his childhood priest in Pittsburgh. The events he recalled took place throughout his childhood. According to the letter, Dorsch forced his victim — whose name has not been made public — to sexually stimulate him repeatedly, ignoring the child’s objections.

The diocese settled with the man quietly after his suicide attempt, paying for his mental health care. But in 2010, payments abruptly stopped. Two months later, the victim attempted suicide again. That time, he succeeded.

This story is just one account out of hundreds listed in a recently released Pennsylvania grand jury report. A 1,400-page document compiled over two years, the report implicated 300 priests in the sex abuse of over 1,000 minors across six of the state’s eight dioceses. (The other two, Philadelphia and Altoona–Johnstown, had been the subject of previous investigations that were no less damning.)

The report revealed that this abuse was made possible by a widespread, systematic cover-up from church leaders and other clergy. Instead of contacting law enforcement about allegations, senior church officials and bishops quietly reshuffled offending priests, typically putting them in positions where they would continue to have close contact with a new set of children. The highest-profile figure accused in participating in such a cover-up is Donald Wuerl, the current archbishop of Washington, DC.

The report and its fallout came during a summer of turmoil for the Catholic Church. First, there was the May revelation that Cardinal George Pell, among the highest-ranking members of the Vatican, faced charges of child sex abuse from decades ago in his native Australia. Then, there was the ousting of Father Theodore McCarrick, formerly the archbishop of Washington, DC, who allegedly committed sexual harassment and abuse against junior seminarians under his authority, as well as against two minors.

Then came the Pennsylvania revelations.

Three hundred abusers and over 1,000 victims, documented in 1,400 pages with stories no less harrowing than the one above. These are just the latest figures in a decades-long crisis, whose full extent may never be known. What has made these stories possible — and what has prevented them, in many cases, from being told until now — is a much wider story of an institution that has, over decades, repeatedly chosen secrecy and bureaucracy over transparency and accountability. It is the story of an institution that has not only failed to protect children from abusers, but has systematically allowed that abuse to continue, often with impunity, and has contributed to the victims’ suffering by repeatedly failing to contend with and take responsibility for its history.

Since 2002, the American Catholic Church — to say nothing of the church globally — has been contending with the sheer catastrophic scope and scale of the crisis. We know about thousands of cases of child sex abuse already. It is likely that thousands more are yet to emerge.

And while efforts taken by the Catholic Church in recent years have significantly reduced abuse since 2002, the fundamental problem remains: There is little to no centralized effort to document, publicize, or take accountability for the decades of systemic child sexual abuse.

But one thing’s for sure: It’s the victims whom the church has left behind.

While cases of Catholic clerical sex abuse were reported by the media up to the 1990s, one-off instances here and there did not signal the truth: that the church was actually dealing with an internal crisis of systemic proportions.

One early accusation concerned Oregon priest Thomas Laughlin, who was removed from ministry in 1983 and spent a year in prison for misdemeanor sex abuse involving sexual contact with two minors. In 1985, Louisiana priest Gilbert J. Gauthe was convicted of molesting at least 39 children between 1972 and 1983.

In 1995, Cardinal Hans Hermann Groër was forced to resign from his position as archbishop of Vienna after allegations of child sex abuse were made public, although he retained his title of cardinal and was allowed to continue in lower-profile church ministry almost until his death. And in 1998, 11 plaintiffs sued the Diocese of Dallas for failing to take action against Rudolph Kos, allowing him to molest minors throughout the 1980s. The plaintiffs were ultimately paid $31 million.

Each of these cases received a degree of media coverage. And victims slowly began to find one another. For example, in Chicago, Barbara Blaine started the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) in 1988.

But the first widespread investigation into Catholic clerical sex abuse as a pattern occurred in the late 1990s, in Ireland. Much of the formative coverage of the Irish crisis was carried out by the team behind the 1999 television documentary States of Fear and the follow-up book, Suffer the Little Children by Mary Raftery and Eoin O’Sullivan. The documentary and book revealed what appeared to be a widespread culture of sexual, emotional, and physical abuse at state-funded, Catholic-run orphanages and educational institutions, as well as an equally widespread cover-up by clergy and local law enforcement.

The Irish sexual abuse crisis was particularly severe, and it rocked the robustly Catholic country’s faith in a church that had been inextricable from Irish national identity. As Irish Times columnist Fintan O’Toole wrote ahead of Pope Francis’s recent visit there, “[Francis] will find a Catholic church not just falling to ruin, but in some respects beyond repair.”

Catholics learned that systemic child sex abuse by priests had also infiltrated American churches in 2002. That January, the Boston Globe published the results of several months of dogged investigative reporting about child sex abuse in the Boston area at the hands of clergy, which had been covered up by the church’s hierarchy over several decades. Journalists at the paper ultimately identified more than 70 Boston priests who had sexually abused children. (For reference, there were 1,678 priests in the Boston Archdiocese that year.)

The investigation was fraught with political difficulties. Boston was a heavily Catholic city — in 2000, 48 percent of Bostonians identified as Catholic. Law enforcement and journalists alike had traditionally been wary of running afoul of the Catholic Church. The Globe reporters later recalled being accused by readers of “anti-Catholic bias” in their reporting, and a feeling that there was little appetite for coverage that aired what seemed to be the church’s dirty laundry.

It was that very systemic culture of secrecy, the Globe found, that allowed abuse to thrive. The investigation found a staggering amount of complicity on the part of both the Boston church hierarchy and local law enforcement. Priests who had abused children would simply be reassigned to other parishes and face few legal or pastoral consequences. Meanwhile, law enforcement officials, reluctant to go up against the Catholic Church, would neglect allegations. When victims did come forward to church officials with allegations, they were often quietly paid off in exchange for their silence. In fact, several of the victims the Globe spoke with had already sought legal advice or gone to the church directly with their complaints, only to be paid to say nothing.

By and large, the Globe found, the church handled abuse cases in absolute secrecy. Individual dioceses throughout Boston paid off victims and sealed records, never making cases public. Priests did not face criminal charges. The avoidance of scandal — or any form of public outcry — often took precedence over ensuring the protection of children. Meanwhile, offending priests were treated as sinners in need of repentance and forgiveness, rather than criminals who merited legal punishment. Instead, many priests were assigned special spiritual counseling or mandated therapy by their superiors, only to return, in many cases, to active ministry.

The highest-profile individual implicated in the scandal was Boston’s archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Law, who was accused of participating in the cover-up.

Central to Law’s disgrace was the case of Rev. John J. Geoghan, who had featured heavily in the Globe’s reporting. Geoghan was defrocked by Pope John Paul II in 1998 after abusing at least 150 boys. He had been shuffled from parish to parish any time anyone made a complaint against him over the course of 30 years. Geoghan was eventually found guilty of indecent assault and battery for groping a child. He was sentenced to prison and murdered by a fellow inmate.

Law was directly responsible for some of Geoghan’s transfers, the Globe found, allowing him to continuously abuse children throughout the area. The lay Catholic group Voice of the Faithful then alleged that Law knew about additional abusers and had in some cases outright lied in order to transfer them quietly to other parishes. Law quietly resigned, but he remained influential within the church until his death last year.

After the Globe’s reporting, victims of sex abuse began to come forward across the United States. Catholic priests and bishops throughout the country attempted to grapple with the problem as it became increasingly apparent Boston was just one slice of a national crisis.

In 2002, the US Conference of Catholic Bishops established a charter of procedures to deal with accused child sex abusers in the clergy, including a “zero tolerance” policy for accused abusers. The charter is officially known as the Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People, or the Dallas Charter, after the city in which it was ratified.

Most importantly, the Dallas Charter mandated that all allegations of child sex abuse by clergy be turned over to law enforcement. Every single diocese in the US, except for one in Lincoln, Nebraska, expressed compliance with the charter and submitted annual audits to the USCCB. Since the establishment of the charter, abuse allegations among priests across the country have declined (except in the Lincoln diocese, where rates remain largely unchanged).

Two years after the Dallas Charter was enacted, the USCCB commissioned a report from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York that dug into the extent of abuse over the previous five decades in the US. The report, which remains the most comprehensive on the subject of clerical sex abuse, concluded that between 1950 and 2002, a staggering 10,667 people across the country accused 4,392 priests of child molestation. This represented about 4.3 percent of active American Catholic clergy during that time. (Some studies suggest this is on par with the rates of child sex abuse committed by the general population).

Only a tiny fraction of these priests, however, had ever been convicted in a court of law, according to the report. Just 252 priests were convicted of a crime, and 100 served time in prison. Instead, dioceses and parishes paid billions of dollars in settlements to accusers over several decades, securing secrecy over these cases. It meant priests would simply be transferred to new parishes, making a new set of families vulnerable to abuse without their knowledge. The John Jay report also concluded that the church hierarchy had systematically defended and protected priests, treating their offenses as sins that demanded repentance and forgiveness, rather than criminal prosecution.

For many dioceses, 2002 marked a turning point. Strategies and policies that were put in place, like the Dallas charter, were largely effective, which the Pennsylvania grand jury report acknowledges. As Massimo Faggioli, a professor of theology at Villanova University, told Vox, “The policies put in place by the US bishops since 2002 have worked.”

A trickier issue, however, is how the church has dealt with the ongoing revelations of abuse prior to 2002. By and large, dioceses have remained unwilling to preemptively publish the names of alleged abusers, even those who have been removed from ministry for their actions.

Throughout the 2000s, however, various dioceses and archdioceses continued to settle privately with victims. The Catholic Church has paid over $3 billion to victims across the United States, and 19 dioceses and religious orders have filed for bankruptcy as a result. In 2007, for example, Archbishop Roger Mahony of Los Angeles authorized the payment of $660 million to 500 victims, who had brought allegations against 220 clergy members of the diocese.

The slow trickle of these revelations coincided with a wider decline in Catholic identity. According to the Public Religion Research Institute, a full 31 percent of Americans report being raised Catholic, yet just 20 percent consider themselves practicing. This is the largest drop-off for any single religious identity. Another study found that, in the period between 1985 and 2012, Catholic church attendance dropped from 52 to 29 percent.

While church attendance and affiliation has dropped across Christian denominations over the past two decades — albeit less so among white evangelicals — it’s nevertheless extremely likely that the abuse crisis has shaken ordinary Catholics’ faith in their church.

One of the ongoing questions in the Catholic clerical sex abuse crisis is what the Vatican knew and for how long, which has never been adequately answered.

Carlo Maria Viganò, a former Vatican official, recently accused Pope Francis of knowingly lifting Pope Benedict XVI-era sanctions on Cardinal McCarrick in 2013. He also claimed Francis was deferential to a so-called gay “network” in the Vatican that ignored abuse. The pope refuses to address these claims. Either way, the truth is more complicated and more difficult to ascertain. For one, Viganò’s assertion conflates consensual homosexual activity, sexual harassment, and pedophilia. More broadly, it does not address in any detail the decades of abuse that came from any other clerics around the globe or the veil of secrecy under which they were allowed to continue abusing children while remaining in ministry.

What we do know is that US archdioceses seem to have operated in many regards outside the oversight of the Vatican, and they rarely passed information about individual abuse cases up the ladder.

Benedict XVI, for example, reportedly told a bishop, “My authority ends at that [office] door,” referencing his limitations on effectively managing a bureaucratic church that in practice, if not in theory, operated largely autonomously. (Certainly, if Viganò’s assertion that Pope Benedict put sanctions on McCarrick is true, this could explain why McCarrick continued to appear in public in the United States during the period of the alleged sanctions.)

Given the Vatican’s culture of secrecy, it is difficult, if not impossible, to get an accurate sense of behind-the-scenes responses to the crisis. On the one hand, the Vatican’s denials could be a convenient way of passing the buck. On the other hand, it seems apparent that international archdioceses have, in many ways, operated on a day-to-day level independently from the curia.

At least as early as the 1960s, figures like Father Gerald Fitzgerald, head of an order called the Servants of the Paraclete that provided counseling for troubled priests, expressed concerns directly to the Vatican that pedophile priests were not being treated with appropriate seriousness. But it remains unclear whether the highest echelons of the Vatican knew about the problem, how much they knew, and when they learned of the extent of the problem.

The response from the Vatican, however, has been somewhat muted. Pope John Paul II was the first pope to deal with the crisis publicly. While he condemned clergy abuse as an “appalling sin” in April 2002, shortly after the Globe report came out, he urged Catholics to focus on the “power of Christian conversion” — redemption — for abusers. He also blamed bishops’ poor handling of the crisis as rooted in “the advice of clinical experts,” such as therapists who treated offending priests and, in the Vatican’s eyes, misleadingly suggested they might be able to return to ministry once “cured.”

The Catholic hierarchy’s focus was, by and large, on ensuring repentance from and redemption for the sinner, not justice for the accusers.

His successor, Benedict, fared a little better. He handed over control of dealing with priest allegations to the centralized office of the Doctrine of the Congregation of the Faith, which he personally oversaw, allowing a degree of streamlining in the process. Under Benedict’s watch, the Church defrocked 384 priests accused of child sex abuse. Benedict met with victims, including five from the Boston archdiocese.

Benedict also ordered an investigation into — and ultimately removed from office — an influential Mexican priest, Marcial Degollado, founder of the powerful religious order Legionaries of Christ, for reported abuse. He was ordered by the Vatican to live a life of seclusion, penance, and prayer until his death.

Many Vatican watchers saw the act as evidence of Benedict’s commitment to combating the issue. But Benedict’s critics say he did not go far enough. He allowed bishops like Kansas’s Robert Finn — who was criminally convicted for failing to report child porn on a junior priest’s computer — to remain in office after his conviction. Benedict also barred men with same-sex attraction from priestly office, seen by many as an unnecessary and insulting move.

In 2010, revelations emerged that Benedict himself — as an archbishop in Munich in the 1980s — was responsible for overseeing the transfer into therapy of a German priest accused of child sex abuse instead of immediately removing him from ministry. That priest was later cleared for reentry into pastoral work, only to commit further sexual abuse. He was ultimately criminally prosecuted for it.

Pope Francis’s own legacy has, likewise, been mixed.

Shortly after becoming pope, Francis announced the creation of a Vatican committee to fight sex abuse in the church. In 2014, he named eight people, including one clerical abuse survivor, Marie Collins, to that committee. He also publicly apologized for the Vatican’s actions, expressing regret that “personal, moral damage” had been “carried out by men of the Church.” He also urged any priest who had enabled abuse by moving an abuser to another parish to resign.

However, progress has been slow. In 2016, the Vatican committee scrapped a proposal that any senior cleric accused of covering up abuse be subject to an internal tribunal, angering victims’ advocates. That same year, Collins stepped down from the committee, calling the Vatican’s lack of progress “shameful.”

And Francis, too, has vocally cast doubt on some accusers. When confronted with allegations that Father Juan Barros, a Chilean priest, had covered up systematic abuse by another priest, Francis called the claims “calumny.” He later apologized for his remarks, and the entire Chilean bishopric resigned under pressure after meeting with Francis on the issue.

Viganò’s letter accusing Francis of neglecting McCarrick’s abuse, however, may prove particularly influential. Even if Francis does not resign, which seems likely, Viganò’s letter may nevertheless intensify the call on some of Francis’s allies — such as Washington, DC’s Archbishop Donald Wuerl, who has been implicated in cover-ups in both the Pennsylvania report and the McCarrick crisis — to step down.

Francis’s response to the Pennsylvania report has been encouraging. While the Vatican itself released a relatively anodyne statement saying that it “condemns unequivocally” child sex abuse, Francis issued a 2,000-word open letter to all “People of God.”

That letter condemns what he calls a “culture of death” on the part of the church: a systematic silencing and shaming of victims. “We showed no care for the little ones,” he wrote, adding, “We abandoned them.”

Francis did not make specific policy recommendations going forward. He did, however, express sympathy with the victims and a commitment to changing the culture of the church. “Looking back to the past,” he wrote, “no effort to beg pardon and to seek to repair the harm done will ever be sufficient. Looking ahead to the future, no effort must be spared to create a culture able to prevent such situations from happening, but also to prevent the possibility of their being covered up and perpetuated.”

Individual bishops and dioceses have taken varying actions in the aftermath of the Pennsylvania report. Some are choosing to remain silent. Others, like Bishop Kevin Rhoades of the Fort Wayne–South Bend diocese in Indiana (and formerly of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), say they will release the names of all priests in their diocese who have ever been removed from ministry due to child sex abuse.

It is unclear what to expect from still-active priests who, like McCarrick, have been accused of abuse or participation in a cover-up. It’s important to note that the process of “defrocking” a priest — formally known as “laicizing” — is not automatic. As Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest and Catholic commentator, told Vox, the process is subject to complex internal rules. So while priests may be removed from active ministry, laicization is a longer, more complicated process similar to a courtroom trial, which also demands the formal presumption of innocence.

As it stands, the church itself is doing little to centralize and publicize narratives of abuse. David Gibson, director of the Center for Religion and Culture at Fordham University and a frequent commentator on Catholic issues, told Vox that there’s still been a widespread reluctance on the part of the church itself to take similar initiatives. “There was no push by the church to do it,” he said. “I think it’s also important to do it … The vast majority of [dioceses] are saying ‘Everybody’s dead! These are very old [cases]!’ … Nobody is trusting the church enough to know in that sense to police its own.” That means that, thus far, it falls to civil authorities — such as grand juries like that in Pennsylvania — to investigate and reveal the scope of allegations.

Meanwhile, on the legal front, Pennsylvania lawmakers are pushing for changes in the statute of limitations to allow victims of clerical sex abuse to pursue civil or criminal charges.

It is unclear whether reports on the scale of Pennsylvania’s will emerge in other states. Pennsylvania’s distinctive grand jury system, which allows the attorney general’s office to commission a large-scale investigation before filing any charges, was integral in assembling the report. There have only been nine such investigations in the United States since the Boston Globe story, including investigations into New Hampshire and Maine’s Catholic churches.

New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood has announced that she, working with several district attorneys throughout the state, may wage a similar commission there. Westchester and Suffolk counties already have investigations underway.

While defenders of the Vatican argue that the Dallas charter has drastically decreased the number of post-2002 cases of abuse, tips are still flooding into prosecutorial and private Pennsylvania hotlines about decades-old cases.

Cases that — for now — have no way of being prosecuted.

Original Source -> The decades-long Catholic priest child sex abuse crisis, explained

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

A Sister’s Glance into Asperger’s - Alicia Hughes