#isabel of castile duchess of york

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Do you know that Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York's wife Isabella is likely to have an affair with a man from the Howard family and gave birth to the Earl of Cambridge, Richard? Isabella's will was made with Edmund's consent, which may indicate that although Edmund did not want his property to go to Richard, he did not hate their mother and son. Perhaps they were just colleagues who had to have children together

I'm not quite sure I'm following your ask. I think you're asking about Isabel (or Isabella) of Castile, Duchess of York and the assertion that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was a son born from her adulterous liaison? However, the man she was accused of having an affair with was not a member of the Howard family but John Holland (or Holand), Earl of Huntington. Huntington was the son of Joan of Kent and Thomas Holland and thus half-brother to Richard II. Huntington was married to Elizabeth of Lancaster who was the sister of Henry IV, which would have been made things awkward (to say the least) when Richard II was deposed. Huntington was killed during the Epiphany Rising which aimed to restore Richard to the throne. .

Jenny Stratford recently published work arguing that the affair did not take place and that Cambridge was legitimate, as far as we can tell. I'll talk you through the evidence and her arguments against it below the cut.

Thomas Walsingham's commentary on Isabel

Thomas Walsingham wrote that Isabel was:

A lady of sensual and self-indulgent disposition, she had been worldly and lustful; yet in the end by the grace of Christ, she repented and was converted. By the command of the king she was buried at his manor of Langley with the friars, where, so it is said, the bodies of many traitors had been placed together.

Stratford points out that Walsingham got the date of her death wrong, placing it two years after her death occurred, which suggests he was probably not well-informed about his life. She suggests that the image of emerges from Isabel's will contrasts sharply against the image Walsingham provides:

The duchess herself emerges in a favourable light. In face of her husband’s debts, the arrangement to provide an income for the seven-year-old Richard by transferring to Richard II most of her jewels and plate, her personal chattels, was eminently practical. It limited the possibility of claims by the duke’s creditors, while grants previously made to Isabel were subsequently reassigned to fund the annuity. These provisions seem very unlikely to indicate that young Richard was illegitimate, any more than a gap of twelve years between the age of the oldest and youngest of the duchess’s three living children was necessarily significant. The duke’s will drawn up a decade after Isabel’s death speaks of his devotion to her.

It's also worth noting that Walsingham has something of a reputation for misogyny and for being unreliable - we now know that some of his assertions about Alice Perrers's background are groundless and serve to make her appear worse than she was, while Anna Duch argued that he effectively erased Anne of Bohemia from his account of Richard II's reign. He is also full of vitriol for Agnes Launcekrona and Katherine Swynford so it seems to me that we should treat his claims on women with great scepticism.

John Shirley's comments on Chaucer's Complaint of Mars

Forty years after Isabel's death, a scribe named John Shirley wrote an afterword on Geoffrey Chaucer's Complaint of Mars that linked it to a scandal involving "the lady of York" and John Holland. Connected with Walsingham's commentary, it's generally been taken as evidence that they had an affair.

Stratford argues that the Shirley's commentary is likely a garbled reference to the affair between Constance of York (Isabel's daughter) and Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent (John Holland's nephew) which the resulted in the birth of an illegitimate daughter, Eleanor. Following Kent's death, Eleanor claimed claimed her parents had married clandestinely before Kent married Lucia Visconti and that she was his rightful heir but her claims were rejected. Historians have suggested that Kent might have considering marrying Constance before the revelation that she had been involved in a plot against Henry IV meant he distanced himself from her.

Additionally, J. D. North argued that the astronomical framework contained within Complaint of Mars could have only applied to the year 1385 and aligns it with the beginning of the affair between Elizabeth of Lancaster and Huntington. Elizabeth had been married to John Hastings, heir to the earldom of Pembroke, in 1380 when she was 16 and Hastings was 8. However, the marriage was annulled in 1386 and Elizabeth soon after married Huntington on 24 June 1386. It is frequently asserted that Huntington and Elizabeth had embarked on an affair that resulted in a pregnancy, leading to the hasty annulment of Elizabeth's first marriage and her second marriage to Huntington though it isn't clear when their first child was born, though it was in 1386 or 1387. It may be that John Shirley's reference to the affair between "the lady of York" and Huntington may actually be referring to Huntington's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster.

It may even be that the reference represents a garbled combination of the two affairs - Constance of York and Edmund Holland, Elizabeth of Lancaster and John Holland - recorded decades later. It might be noteworthy in this regard that Elizabeth and Huntington's first child was also named Constance (both Constances were named after Isabel's sister, Constanza or Constance of Castile), which would add to the confusion).

The wills of Cambridge's father and older brother.

The argument that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was illegitimate is based around the lack of reference to Cambridge in the wills of his father and older brother, where it is assumed that this represents that Cambridge was effectively, though not legally, disowned.

His brother, Edward 2nd Duke of York's will was written after Cambridge had been executed as a traitor for his role in the Southampton Plot. His lack of reference to Cambridge may simply be because Cambridge was dead and could not be a beneficiary. There may have also been concern that any reference to Cambridge, such a request for prayers for his brother's soul, could result in suspicion of Edward's own loyalties. From the surviving evidence, Edward also seems to have had a close relationship with Henry V so Cambridge's treason may well have driven a wedge between the brothers. In short: there are a lot of reasons why Edward might have avoided referencing Cambridge explicitly that were far more relevant to the circumstances his will was written in.

Stratford notes that "a testator may not include all his bequests in his will", which would apply to both Dukes of York. Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York left "nothing in the will to any of his three children" (my emphasis). He did, however, ask to be buried "near his beloved Isabel, formerly his companion". In short, there is no reason to presume Cambridge's exclusion was due to his being informally disowned by his father due to the adultery of his mother. York's will provides no support to the idea that he had a fraught relationship with Isabel, either.

Isabel's will makes special provision for Richard, Earl of Cambridge.

Isabel's will asked Richard II for provide an annuity of 500 marks for Cambridge against the surrender of her jewels and plate until appropriate lands could be found to furnish him with an income. This has led to the belief that Cambridge would not be supported by his father and brother and, in combination with the above, that this was because he was illegitimate.

Most of this is based on the transcript of her will published in Testamenta vetusta, which is a shortened extract of the full document which didn't include Isabel's many bequests to her husband (if you read something that claims Isabel left York nothing, the author is working from the abridged will, not the full text). Stratford's study is on the original will in its full form. As noted in your ask, Isabel required and received the permission of her husband to make this will. Stratford also notes that some of those mentioned in the will are Edmund, Duke of York's officers who also appear in his will, "strongly suggesting that the duke and the leading members of his familia were in full agreement with its provisions". In short, the idea that York was refusing to acknowledge or provide for Cambridge seems somewhat illogical given his involvement and the involvement of his officers in Isabel's will which was primarily concerned with providing for Cambridge.

Stratford argues that what the will represents is an effort by Isabel and York to provide for Cambridge "while protecting as far as possible the incomes of her husband and his heir."

The principal purpose of Isabel’s will was to provide for their youngest child, Richard, then aged seven. Edmund gave his wife full powers to dispose of her horses, jewels, robes, the furnishings of her chamber, and her other chattels. She made a number of bequests, notably including books, but offered the majority of her valuables to Richard II if he would agree to provide her younger son, his godson (filiol), with an income of 500 marks per year for life. If the king did not so wish, Isabel’s oldest son, then earl of Rutland, was invited to do so on the same terms.

At the time Isabel was drawing up her will, York was heavily in debt following his Portuguese expedition, had difficulty obtaining money due to him from the Crown, and didn't have lands commensurate with his status. York's executors were still struggling to pay his debts eight years after his death and when his eldest son died in 1415, the duchy of York remained bankrupt for twenty years. Stratford notes that the money raised by Isabel's jewels and plate would "circumvent claims on the duke by his creditors".

John Holland gave Isabel a gift.

Isabel's will mentions a "sapphire and diamond brooch" given to her by John Holland, Earl of Huntington which has been taken as evidence of their affair. Sometimes she is also said to have been given a gold cup and a chaplet of white flowers by Huntington, though Stratford points out the brooch is the only item actually said to have been given to her by Huntington and is one of three gifts from named donors (the others was a "little" gold tablet given to her by John of Gaunt and a gaming board of jasper from Leo of Armenia).

Firstly, while gifts of jewels to us seem to be strictly or largely romantic gestures, this very much wasn't the case within the Middle Ages, where the exchange of jewels was a normal part of aristocratic life, albeit serving an important function. We know that medieval nobles frequently exchanged gifts, including items they had been given by others, and it is a pure speculation to assume that Isabel "treasured" the brooch or even that she kept it because it was Huntington who had given to her. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that it was identified through the designation as a gift given to her by Huntington.

Secondly, if this is evidence of their affair which produced Cambridge, it's very odd that she didn't leave Huntington's gift to Cambridge but to her eldest son, Edward, who was York's acknowledged son and heir whose legitimacy has never been doubted.

Isabel left bequests to Holland.

Isabel left her Bibles and "the best fillet I have" to John Holland. Some have argued that this is unusual enough because Holland was the only person she gave gifts to who wasn't a "close member" of her family.

Outside of her husband and three children, Isabel also left bequests to Richard II, Anne of Bohemia, John of Gaunt and Eleanor de Bohun, Duchess of Gloucester, and Stratford groups with Eleanor as a member of Isabel's "wider family" and says it is credible they were friends, not lovers. The extent that Holland isn't a "close" member of her family can be debated: he was married to her niece (Elizabeth of Lancaster) and the half-brother of her nephew (Richard II).

Stratford says that Isabel may have made the bequest to Huntington in hope that that he would influence Richard II and John of Gaunt (who was Huntington's father-in-law and and close ally in the 1380s and named as an executor in Isabel's will) to ensure that the annuity she sought for Cambridge would become a reality.

Furthermore, Stratford suggests that the "best fillet" (which was probably a collar) may have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, Huntington's wife. If so, this would rather point away from it being a memento from their affair.

There were a ten-year gap between Cambridge and his siblings.

The other main piece of evidence put forward is the large gap between Constance of York (b. c. 1375) and Cambridge (b. c. 1385). The supposition usually goes that having had two children (Edward, 2nd Duke of York was born c. 1373), Isabel and York had grown tired of each other's company and didn't have sex again, Isabel then embarked on an affair with Huntington that, some ten years after Constance's birth, left her pregnant and York allowed the child to be brought up as his son but refused to provide for him.

The problem with this scenario is that it is effectively a complete invention. The idea that York and Isabel were at odds is based around the idea of the affair and the speculation Cambridge was illegitimate. York never repudiated Isabel nor officially disowned Cambridge as a bastard. There are many possible reasons why there was such a large gap - fertility issues, miscarriages, bad luck, personal decisions, religious reasons (i.e. choosing to adopt a chaste marriage). Constance's birth may have been particularly difficult and York and Isabel decided not to chance sexual intercourse or to use the contraceptive methods available to them only to slip up. It's also possible that they may had other children who died too young to leave evidence behind and that the large gap between children wasn't that large in reality. After all, it seems we know very little about the births of their children, even the years are uncertain.

I know this is all speculative but so is the argument that they fell out. The point is that we don't have evidence to explain why beyond speculation.

Conclusion

A lot of the arguments for the affair based on tenuous links and are often based on the assumption that the affair was a historical fact and that Walsingham's comments on Isabel are an objective and reasonable account of her character. So the evidence that shows us a connection between Isabel and Huntington is often assumed to be evidence of a sexual relationship.

Take the brooch. It seems to be read as the equivalent of a man buying his lover an emerald necklace or diamond earrings. Except we know that the exchange of valuable jewels as gifts was a common aspect of medieval noble life that performed a vital function that very frequently had nothing to do with romantic or sexual feelings. We know, for example, that Henry VI gave Eleanor Cobham a brooch - it does not follow that they were therefore having an affair or that Henry harboured romantic feelings for his aunt.

That the brooch was mentioned in Isabel's will also tells us nothing. We don't know how she felt about it, only that she singled it out to be passed onto her eldest son (not Cambridge). It may be that she wanted him to have it because of he had admired it and, if it was a feminine piece, may have intended to give it onto his wife when he married. It's quite unremarkable that a medieval individual would identify a piece through noting who had given it to them and is not proof of romantic attachment. Isabel also mentioned gifts given to her by John of Gaunt and Leo of Armenia - should we assume she had affairs with them too?

On a similar note: that Isabel left items to Huntington is taken as proof of their romantic liaison. The bequest? Her best fillet (probably a collar, according to Stratford), which may well have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, and her Bibles. They were likely valuable items but hardly proof of romantic involvement - such bequests were very common and would be utterly remarkable without the context of Shirley's commentary on their relationship.

It seems to me that there is good good reason to believe that John Shirley's commentary on Complaint of Mars, written decades after Isabel's death, may not have been about Isabel at all. She isn't named in the commentary and we have no clear, explicit evidence of this affair outside of the commentary itself. I think it was a garbled recollection of either Isabel's daughter, Constance of York's affair with Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent or of John Holland's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster. We have clear, contemporary evidence of both these affairs - the existence of Constance's and Kent's daughter and this daughter's attempt to inherit Kent's estates, the annulment of Elizabeth's marriage to Hastings and her marriage to Huntington.

The evidence cited as "proof" of their affair is really nothing of the sort. Isabel's will attempted to provide for Cambridge in the face of York's (comparatively) small income and large debts. Huntington was a beneficiary but hardly the only one and not a particularly unusual choice. He gave Isabel a gift that was in keeping with the social custom of their class and time. York's will mentioned none of his children and he did not officially disown Cambridge. The lack of reference to Cambridge in his brother's will is easy to understand given it was written after Cambridge had been executed for treason. We have no real evidence of discontent between Isabel and York - he was obviously involved in the writing of her will and he requested burial with her in his own. Nor is there any account that records discord between them or separation, like we do for John of Gaunt and Constanza of Castile. York was buried with Isabel, as he had requested, and on their joint tomb-monument are Huntington's coat of arms (amongst many others). It seems very strange to me that York was so utterly furious about Isabel's adultery that he refused to provide for Cambridge, forcing Isabel to beg the king to provide for him, yet he chose to be buried with her, he chose as his second bride Huntington's niece, Joan Holland, and he chose to add the coat-of-arms with the man she had betrayed him with on their tomb monument (which was probably constructed sometime between 1393 and 1399). I don't think this picture holds up.

Walsingham did criticise Isabel for being "worldly and lustful" but Walsingham calling a woman a slut is pretty par for the course for him and he got facts of her life wrong. Nor does he report anything she actually did to deserve such a reputation. In others: scepticism is clearly needed. None of this adds up to very much. It isn't until Shirley wrote his commentary, decades later, that we find any reference to their affair. The rest are things that would be entirely unremarkable without Shirley's commentary directing us to see it as a romantic gesture.

Of course, the fact is that we can't prove she didn't have an affair and that Shirley was really referring to a more evidenced scandal. Proving a negative is hard. Even if we located, exhumed and DNA-tested the bodies of Cambridge, York and Huntington, we might confirm that Cambridge was really York's son (or Huntington's or the son of an unknown man) but we wouldn't be able to prove that Isabel didn't have sex with Huntington at some point in her life. We don't have evidence for every single time a medieval individual had sex and so we can't definitively rule out the possibility that an affair did occur. All we can say is the actual surviving evidence doesn't support the narrative that Isabel had an affair.

It's probably worth noting that Kathryn Warner also read Isabel's full will and still accepts the narrative of Isabel's infidelity, though she argues Cambridge should be given the benefit of the doubt where his illegitimacy is concerned. Personally, I find Stratford's reading of the will more credible than Warner's. I don't think the evidence cited as proof of Shirley's claim is actually evidence of an affair but the existence of a typical relationship between medieval nobles working as normal. Warner seems to contradict herself at times* and she doesn't seem to have been interested in questioning whether Isabel did or did not have an affair. I also think Stratford's extensive work on medieval manuscripts and the inventories of John, Duke of Bedford and Richard II lends credence to her claims.

Works Referenced

Jenny Stratford, "The Bequests of Isabel of Castile, 1st Duchess of York, and Chaucer’s ‘Complaint of Mars’", Creativity, Contradictions and Commemoration in the Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of Nigel Saul, eds. Jessica A. Lutkin and J. S. Hamilton (The Boydell Press 2022)

Jenny Stratford, "Isabel [Isabella] of Castile, duchess of Yorkunlocked (1355–1392)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (published 2022, updated 2023)

J. D. North, Chaucer's Universe (Oxford University Press 1988)

James P. Toomey (ed.), "A Household Account of Edward, Duke of York at Hanley Castle, 1409-10", Noble Household Management and Spiritual Discipline in Fifteenth-Century Worcestershire (Worcestershire Historical Society 2013).

John Evans, "XIV. Edmund of Langley and his Tomb", Archaeologia, vol. 46, no. 2, 1881

Kathryn Warner, John of Gaunt: Son of One King, Father of Another (Amberley 2022)

(also looked at the ODNB entries for York, Cambridge, Huntington and Elizabeth of Lancaster).

* After mentioning the brooch given to Isabel by Huntington, Warner states: "Isabel did not not mention other gifts she had received from anyone else". In an earlier chapter, Warner says "The 1392 will of Isabel of Castile, duchess of York and countess of Cambridge, reveals that Levon [Leo of Armenia] gave her a ‘tablet of jasper’ during this visit, which she bequeathed to John of Gaunt". Warner also repeats this within the chapter dealing with Isabel's will: "and ‘a tablet of jasper which the king of Armonie [King Levon of Armenia] gave me’ to John of Gaunt". How can Huntington's brooch be the only gift from anyone mentioned in her will when we've been told (twice) that Isabel's will includes a reference to a tablet of jasper gifted to her by Leo of Armenia? Additionally, Warner's arguments seems to be drawn from the preconceived notion that Isabel did have an affair so any evidence connecting her to Huntington must be evidence of the affair, regardless of how limited the evidence is - this is quite surprising, since it goes against one of her arguments against reading Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer's relationship as a love affair.

#ask#anon#isabel of castile duchess of york#john holland earl of huntington#edmund duke of york#richard earl of cambridge#i did just have the revelation cambridge was only a year and a bit older than henry v#god this is long

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabel of Castile, First Duchess of York

Isabel was the third of four children of King Pedro I, also known as Pedro the Cruel, who ruled the Crown of Castile from 1350. Her mother was the vivacious and intelligent Maria de Padilla, often described as Pedro's mistress. In 1361, when Isabel was only six, her mother died. The following year, Pedro declared that he and Maria had been lawfully married before he was forced to espouse his estranged French wife, Blanche of Bourbon, who was by then also dead, some said murdered by her husband. His claim of an earlier marriage was subsequently endorsed by the Cortes, thus legitimising Pedro's children by Maria. Pedro was killed by his illegitimate half-brother and deadly enemy Enrique of Trastámara in March 1369. Trastámara became King Enrique II of Castile.

Isabel accompanied her elder sister Constanza to England, and married Edmund of Langley, son of Edward III and Philippa of Hainault, in 1472 at Wallingford, as part of a dynastic alliance in furtherance of the Plantagenet claim to the crown of Castile. Isabel was only 16 or 17 to Edmund’s 31, and brought him no lands or income or even the promise of such because her sister Constanza – who married Edmund’s elder brother John of Gaunt as his second wife – was their father’s heir. John and Constanza spent many years trying unsuccessfully to claim her late father’s throne from her illegitimate half-uncle Enrique of Trastamara, while Edmund and Isabel were required to give up any claims to the kingdom of Castile and were not compensated.

As a result of her marriage, Isabel became the first of a total of eleven women who became Duchess of York. She was appointed a Lady of the Garter in 1379. In their twenty years of marriage, the Duke and Duchess of York had three children:

Edward of Norwich, Duke of York

Constance

Richard of Conisburgh, Earl of Cambridge

Contemporary sources suggest that Edmund and Isabel were an ill-matched pair and their relationship was a rocky one, with Isabel accused of having an affair with John Holland, Duke of Exeter and half-brother to Richard II. The affair is believed to have started as early as 1374 and likely continued for a decade. As a result of her indiscretions, Isabel left behind a tarnished reputation. The chronicler Thomas Walsingham considered her to have somewhat loose morals.

John Holland has also been suggested as the real father of Isabel’s youngest son, Richard of Conisburgh, who was the grandfather of Edward IV and Richard III. The fact that his father Edmund of Langley and brother Edward, both, left him out of their wills has fuelled this theory. However, leaving a son out of your will was not entirely unusual, and Richard had died when his brother made his will.

Isabel of Castile died in December 1392 at the age of about 37 and was buried at Langley Priory in Hertfordshire. In her will, Isabel left items and gifts of money to close relatives by blood or marriage, and to numerous servants of hers, men and women. Isabel referred to Edmund of Langley as her "very honoured lord and husband of York", and left him all her horses, all her beds including the cushions, bedspreads, canopies and everything else that went with them, her best brooch, her best gold cup, and her "large primer". Isabel named King Richard II as her heir, requesting him to grant her younger son, Richard, an annuity of 500 marks. Isabel left nothing at all to her older sister Constanza, duchess of Lancaster, and failed even to mention her. Isabel doesn't forget John Holland in her will, at this time married to Elizabeth of Lancaster, John of Gaunt's daughter.

About 11 months later her widower married Joan Holland, niece of Isabel's supposed lover, John Holland. In another bizarre family twist, it was Joan’s brother, Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent, who had an affair – and an illegitimate daughter – with Constance of York, the daughter of Edmund and Isabel. In Edmund’s own will of 1400 he requested burial ‘near my beloved Isabele, formerly my consort.’ Despite Isabel of Castile's bad reputation and supposedly having been involved in a court scandal that humiliated her husband, Edmund seems to have felt great affection for her as demonstrated by his willingness to rest eternally with Isabel and not with his second wife.

Source:

#Isabel of Castile#Edmund of Langley#Duchess of York#Duke of York#women in history#english history#spanish history

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you name all 59 women

1. Anne Bonny: a lesbian

2. Mary Read: a lesbian

3. Mary Read again: an abusive, cheating wife

4. Mary, Queen of Scots: a lesbian. (But also not a lesbian because Hester Mary MacKenzie was also her concubine.)

5. Isabella 'Bella' Baldwin: a lesbian

6. Queen Elizabeth of Parma, also known as Isabelle d'Este, was the Empress of Modena. She's one of several queens whose non-biological children were legitimized by the church.

7. Mary, Queen of France (before and during her marriage to Henry III).

8. Charlotte of Savoy: a lesbian

9. Elizabeth of York, also Elizabeth Stuart: a lesbian

10. Anna Ivanovna Demushkin: a lesbian (Ivan the Terrible's wife, as well as Mary Queen of Scots')

11. Mary, Duchess of Orleans: a lesbian

12. Mary, Duchess of Orleans again: a lesbian

13. Isabella of France: a lesbian

14. Margaret of Anjou, wife of Francis Plantagenet: a lesbian.

15. Mary 'Mary of Guise', daughter of Margaret of Anjou and Francis Plantagenet: a lesbian

16. Queen of Denmark: a lesbian (Anne's daughter, Sophie of Poland and Denmark)

17. Catherine Howard: a lesbian

18. Katherine Howard: a lesbian

19. Mary, Queen of England: a lesbian (Mary Tudor)

20. Eleanor of Austria, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella: a lesbian (Mary Tudor's daughter, also Queen of England)

21. Mary, Queen of Bohemia: a lesbian

22. Catherine Parr: a lesbian

23. Eleanor of Austria, again: a lesbian (Mary Tudor's daughter, also queen of England)

24. Mary Tudor: a lesbian

25. Queen of Scots: a lesbian

26. Catherine Parr again: a lesbian

27. Christine de Bourgogne: a lesbian, as well as a queen of France.

28. Jane Seymour, wife of Thomas Seymour and mother of Edward Seymour. Also a lesbian.

29. Mary Stuart: a lesbian

30. Isabella of Castile: a lesbian

31. Mary Stuart again, daughter of Mary I of England: a lesbian

32. Jane Seymour again: lesbian (Edward Seymour's mom)

33. Anne Fitzwilliam, Duchess of Norfolk: a lesbian

34. Barbara Tacy, Countess of Pembroke: a lesbian

35. Mary Tudor again: a lesbian. (Mary Stuart's daughter again)

36. Jane Buckley: a lesbian

37. Catherine Parr: Elizabeth Howard, Parr's daughter, was Queen of England after her mother's death and died without an heir.

38. Margaret Cecil: a lesbian

39. Anna of Cleves: Anne Beaton, wife of Frederick V, Elector of Saxony and of James I and Mary, Queen of Scots; and her granddaughter, Lady Jane Grey, daughter of King Henry VIII and Edward Seymour.

40. Henrietta Maria Stuart: lesbian

41. Anne of Cleves: lesbian

42. Mary Queen of France: lesbian

43. Mary Queen of France again: a lesbian

44. Margaret, Countess of Lennox: lesbian

45. Elizabeth Howard: another lesbian

46.

Anne Stafford: a lesbian

47.

Jane Stafford: a lesbian

48. Jane Seymour again: a lesbian

49. Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots: lesbian

50. Princess Margaret: a lesbian

51. Anne of Cleves again, this time as a mother: Mary Tudor's daughter; Queen of England for less than a month in 1553

52.

Jane Stafford again: lesbian

53. Margaret Howard, Countess of Stafford: lesbian

54. Lady Jane Grey again: a lesbian

55. Princess Anne: a lesbian. (Princess of Portugal and the two Marianas, of Portugal and England.)

56. Elizabeth Howard again: lesbian

57. Margaret of Anjou, Lady of Woodville, wife of Ralph Neville, son of the Duke of Northumberland (Henry Tudor).

58.

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

♛ STARZ THE ROYALTY COLLECTION* ♛

THE WHITE QUEEN | men go to battle women wage war

↳ Edward IV, King of England and Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England

↳ George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence and Prince of England and Isabelle Neville, Duchess of Clarence.

↳ Richard Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester and Prince of England later Richard III of England and Anne Neville, Duchess of Gloucester later Queen of England.

THE WHITE PRINCESS | love to the death

↳ Henry VII, King of England and Elizabeth of York, Queen of England.

THE SPANISH PRINCESS | fight like a woman

↳ Henry VIII, King of England and Katherine of Aragon and Castile, Queen of England.

*based on the Philippa Gregory Novels: The White Queen, The Red Queen, The Kingmaker’s Daughter, The White Princess, The Constant Princess, The King’s Curse and Three Sisters, Three Queens

#the white queen#the white princess#the spanish princess#perioddramaedit#twqedit#twpedit#thespanishprincessedit#max irons#rebecca ferguson#david oakes#Eleanor Tomlinson#Aneurin Barnard#faye marsay#jacob collins levy#jacob collins-levy#jodie comer#ruairi o'connor#charlotte hope#my edits#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#George Plantagenet#isabelle neville#Richard III#anne neville#henry vii#elizabeth of york#henry viii#Katherine of Aragon#forever bitter we did not get promos of mary/charles or margaret/james

344 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royal women who died in childbirth in 15/16th century

There are misconceptions that Tudor were somehow unnaturaly cursed, more plagued by fertility issues and deaths in childbirths than the other dynasties.

Plenty of past royal miscarriages and stillbirths were not even recorded. But had they existed they could have contain similiarly grim acount. But we can at least look at records of royal women who died in childbirth in 15th and 16th century:

During, or soon after childbirth/miscarriage:

Philippa of England, Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 1430

Catherine of Castille, Duchess of Villena in 1439

Catherine of Poděbrady, Queen of Hungary in 1464

Anne of Savoy(Crown Princess of Naples) in 1480

Isabella of Aragon, Queen of Portugal in 1498

Elizabeth of York, Queen of England in 1503

Anne of Foix-Candale, Queen of Bohemia and Hungary in 1506

Maria of Aragon, Queen of Portugal in 1517

Jane Seymour, Queen of England in 1537

Isabella of Portugal, Holy Roman Empress in 1539

Maria Manuela of Portugal, Princess Asturias in 1545

Catherine Parr, Dowager Queen of England in 1548

Isabella of Valois, Queen of Spain in 1568

Claude of Valois, French Princess in 1575

Anne of Austria, Queen of Poland in 1598

Weeks/Months after(never recovered fully):

Catherine of Valois, Dowager Queen of England in 1437

Isabel Neville, Duchess of Clarence in 1476

Barbara Zápolya, Queen of Poland in 1515

Aditionally deaths of royal women:

Blanche of England died of fever in 1409, she was pregnant at the time

Mary of Burgundy died in 1482, weeks after she fell from horse and broke her back. She was pregnant at the time.

Claude of France, Queen of France might have died from childbirth or miscarriage in 1524, although different causes are also speculated by historians-mainly illness and poison.

Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg, Queen of Sweden died in 1535. She was pregnant and fell badly while dancing. The fall confined her to bed and lead to complications and eventually her death.

Joanna of Austria, Grand Duchess of Tuscany had fell from stairs in 1578 eight months pregnant. She then had premature labour where baby was in difficult position and both of them died.

Deaths due to cancer of reproductive organs:

Barbara Radziwiłł, Queen of Poland died in 1551. The cause was widely speculated at the time, but modern historians think it could have been cervical or ovarian cancer.

Mary I of England died in 1558 fallowing phantom pregnancy. Historians think it could have been ovarian or uterine cancer.

(Some might disagree with Catherine of Valois dying of childbirth. But imo, if you think her giving birth and her death detoriating not long after is not at least contributing factor, then you’re insane.)

It’s a lot of women. Those were the days. Men fought on battlefields and women had battlefield of their own. The most heartbreaking for me are the cases where mother died in childbirth and the child didn’t live or died young.

I have probably missed some women. I mostly fallowed just main royal line. Queens, spouses of crown princes and blood princesses. But there should have also been wives of the rest of the princes, i just looked at few.

Also in some cases, the cause of death was not recorded, nor was there any theory about possible pregnancy pushed foward by historians. We can rule out those royal women who died pass their childbearing years. But younger ones we can only speculate about. Although in 16th century if the royal woman died of illness or generally poor health, usually it is mentioned. In 15th-usually nothing.

So we will never get 100% accuracy, but i try.

It’s certainly interesting to me reading that Queen of Sweden died after falling badly during dancing. I thought that period superstition(which lingers to today) that one should not dance is total bull. But aparently they had some dances which could cause pregnant lady harm. Idk, maybe some of those jumpy ones could cause woman to trip and fall very easily?

I will probably update this in future. Write to me if I made mistake in anything or if you know of any more royal women who died either in childbirth or after or while pregnant in 15/16th century. Or if you know anything more about death of Claude of France.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AU Tudor: Best Destinations for Henry VIII's Wives (That is, if they had never married him)

Catherine of Aragon-Queen of England (1485-1540)

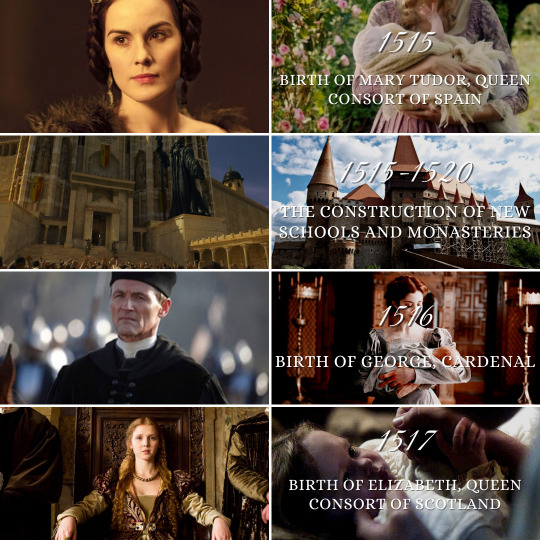

Catherine and her husband, the Prince of Wales, Arthur Tudor were deeply in love and that great love was able to overcome the disease they were going through. The improvement of the princes was a great joy for all and the couple continued with their normal life, being a very united and passionate couple also focusing on the task of bringing children into the world. In 1504 the couple's first son, Henry, the future Henry VIII of England, was born. The birth of the little one was a great joy for England and for the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, since the succession to the throne was assured. Two years later Princess Victoria was born, who would be Queen Consort of France.

In the year 1509 King Henry VII of England died and Arthur sat on the throne as Arthur I of England, Catherine being his consort. Dances and masses were held for the new kings wishing them a long life and many descendants. In 1515 the third daughter of the kings was born, Mary who became queen consort of Spain.

During the years 1515 and 1520 England was involved in numerous conflicts between Catholics and Protestants. King Arthur did not want to start a war of religion trying to appease both sides but to be a fervent Catholic like his queen. In that period, Catherine had two more children: George Tudor in 1516, who became a cardinal, and Elizabeth in 1517 who was Queen of Scotland; During Elizabeth's pregnancy, Arturo suffered an attack at gunpoint by a Protestant and this news greatly upset the queen, giving birth to her daughter prematurely.

In the year 1523 Arthur and his little brother, Henry the Duke of York, made the passes after ten years of estrangement, in addition to promising the Prince of Wales, Henry, with his older cousin, Eleanor. A year later both cousins were married in the Church of Greenwich in a simpler but happy ceremony.

In 1525, Princess Victoria married King Francis I of France shortly after Claudia de Valois' widow. This marriage managed to make peace between France and England.

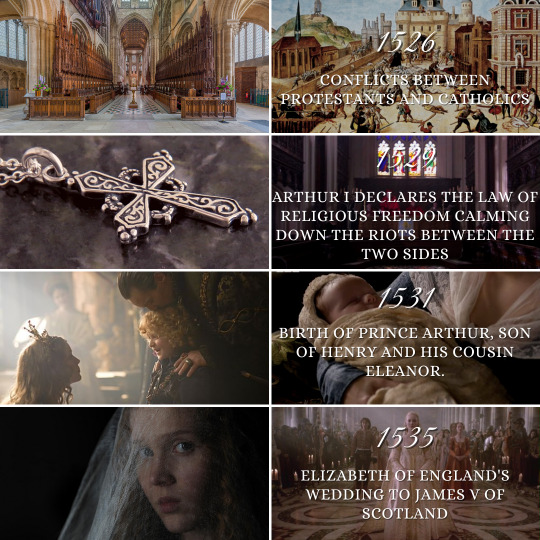

In the year 1526 there was a revolt between the religious groups resulting in the death of more than two thousand people. This event was known as "the massacre for Christ" being a great tragedy for the kings who tirelessly searched for the perpetrators of the massacre.

In the year 1527 the first daughter of the princes of Wales was born, Catherine who was Duchess of Orleans. A year later she was born Margaret, but she died of smallpox at the age of seven.

Three years later in 1529 the king declared the law of free religion respecting the religions of every inhabitant of England, Arthur being known as "The Conciliator". Despite the fact that Catherine was a fervent Catholic, she respected the Protestant side and did not include religion in the issues of State.

In 1531 Prince Arthur was born, the first son of Prince Henry and his wife Eleanor, this birth being a great joy for all England. A year later another son was born, Luis who would be Duke of Cornwall, the duchy being separated from the title of Prince of Wales.

At first, Princess Mary was betrothed to her cousin, Carlos I of Spain, but he broke off his commitment to marry Isabel of Portugal, having numerous tensions between England and Spain, but the Spanish king proposed to marry his cousin with his son, the Prince of Asturias, Felipe. This engagement did not please the kings very much due to the twelve years difference between the young people, but in the end they agreed to marry in the year 1532.

In 1535 Arthur and his sister Margaret decided to marry his sons James V of Scotland and Elizabeth of England to each other. That same year the couple got married and Elizabeth was crowned Queen of Scotland in this way both countries signed peace.

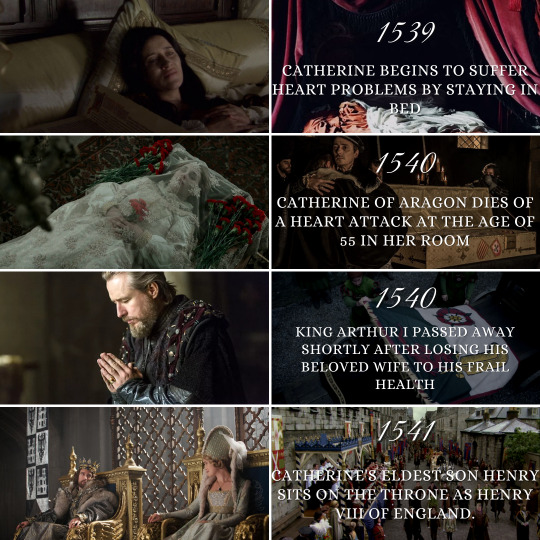

In the year 1539 Catherine suffered a relapse while returning from a mass, this caused her to stay in bed for several months in which her condition began to worsen more and more, but she remained strong for her country and her husband who did not detached from his queen from the start. One year after complete agony and grief, Queen Catherine of Aragon passed away at the age of 55. It is said that on her deathbed, she hugged her husband, who was devastated when he saw her beloved wife dead in her arms. Catherine's death was felt in much of Europe and she was remembered as a faithful, charitable queen and a great mother.

Catherine was buried in St George's Chapel at Windsor Castle. Just four days after the queen's funeral, Arthur I fell seriously ill and the next day he passed away at the age of 54. The king's last words were "my beloved Catalina."

AU Tudor: Los mejores destinos para las esposas de Henry VIII (Es decir si ellas nunca se hubieran casado con el)

Catalina de Aragón-Reina de Inglaterra (1485-1540)

Catalina y su esposo, el príncipe de gales, Arturo Tudor estuvieron enamorados profundamente y ese gran amor pudo contra la enfermedad por la que estaban pasando. La mejoría de los príncipes fue una gran alegría para todos y la pareja siguió con su vida normal, siendo una pareja muy unida y pasional centrándose también en la tarea de traer hijos al mundo. En el año 1504 nació el primer hijo de la pareja, Henry el futuro Henry VIII de Inglaterra. El nacimiento del pequeño fue una gran alegría para Inglaterra y para los reinos de Castilla y Aragón, ya que la sucesión del trono estaba asegurada. Dos años después nació la princesa Victoria que sería reina consorte de Francia.

En el año 1509 falleció el rey Enrique VII de Inglaterra y Arturo se sentó en el trono como Arturo I de Inglaterra siendo Catalina su consorte. Se celebraron bailes y misas por los nuevos reyes deseándoles una larga vida y muchos descendientes. En el 1515 nació la tercera hija de los reyes, María que se convirtió en reina consorte de España.

Durante los años 1515 y 1520 Inglaterra se vio envuelta en numerosos conflictos entre católicos y protestantes. El rey Arturo no quería iniciar una guerra de religión tratando de apaciguar a ambos bandos pece a ser un ferviente católico como su reina. En ese periodo Catalina tuvo dos hijos mas: George Tudor en el año 1516, quien se convirtió en cardenal, e Isabel en el año 1517 quien fue reina de Escocia; Durante el embarazo de Isabel, Arturo sufrió un ataque a punta de pistola por parte de un protestante y esta noticia altero mucho a la reina dando a luz a su hija de manera prematura.

En el año 1523 Arturo y su hermano pequeño, Enrique el duque de York hicieron las pases después de diez años de distanciamiento, además de prometer al príncipe de Gales, Enrique con su prima mayor, Leonor. Un año después ambos primos se casaron en la Iglesia de Greenwich en una ceremonia mas sencilla, pero feliz.

En el 1525 la princesa Victoria se caso con el rey Francisco I de Francia poco después que este enviudara de Claudia de Valois. Este matrimonio logro hacer la paz entre Francia e Inglaterra.

En el año 1526 hubo una revuelta entre los bandos religiosos resultando en la muerte de mas de dos mil personas. Este acontecimiento fue conocido como “la masacre por Cristo” siendo una gran tragedia para los reyes quienes buscaron incansablemente a los perpetradores de la masacre.

En el año 1527 nació la primera hija de los príncipes de Gales, Catalina que fue duquesa de Orleans. Un año después nació Margaret, pero falleció de viruela a los siete años.

Tres años después en el 1529 el rey declaro la ley de libre religión respetando las religiones de cada habitante de Inglaterra, siendo Arturo conocido como “El conciliador”. Pesé a que Catalina era una ferviente católica ella respeto al bando protestante y no incluía la religión en los temas de Estado.

En el 1531 nació el príncipe Arturo, el primer varón del príncipe Enrique y su esposa Leonor, siendo este nacimiento una gran alegría para toda Inglaterra. Un año después nació otro hijo varón, Luis que sería duque de Cornualles siendo el ducado separado del titulo de príncipe de Gales.

En un principio la princesa María fue prometida con su primo, Carlos I de España, pero este rompió su compromiso para casarse con Isabel de Portugal teniendo numerosas tenciones entre Inglaterra y España, pero el rey español propuso casar a su prima con su hijo, el príncipe de Asturias, Felipe. Este compromiso no gusto mucho a los reyes debido a los doce años de diferencia entre los jóvenes, pero al final accedieron al casamiento en el año 1532.

El 1535 Arturo y su hermana Margarita decidieron casar a sus hijos Jacobo V de Escocia e Isabel de Inglaterra entre si. Ese mismo año la pareja se caso e Isabel fue coronada como reina de Escocia de esta manera ambos países firmaron la paz.

En el año 1539 Catalina sufre una recaída mientras regresa de una misa, esto provoca que se quede en cama por varios meses en los cuales su estado empieza a empeorar cada vez mas, pero se mantiene fuerte por su país y su marido quien no se a despegado de su reina desde el comienzo. Un año después de completa agonía y pena, la reina Catalina de Aragón falleció a la edad de 55 años. Se dice que en su lecho de muerte abrazo a su marido el cual quedo destrozado al ver a su amada esposa muerta en sus brazos. La muerte de Catalina fue sentida en gran parte de Europa siendo recordada como una reina fiel, caritativa y una gran madre.

Catalina fue enterrada en La Capilla de San Jorge, en el Castillo de Windsor. Tan solo cuatro días después del funeral de la reina, Arturo I callo enfermo de gravedad y al día siguiente falleció a la edad de 54 años de edad. Las ultimas palabras del rey fueron “mi amada Catalina”.

#catherine of aragon#arthur tudor#arthur i of england#henry viii#victoria of england#mary of england#george of england#elizabeth of england#house tudor#AU

64 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Here's the list of the characters I used :

- Queen Victoria (Victoria)

-Princess Jasmine (Aladdin)

- Isabella I of Castille (Isabel)

- Elizabeth of York (TWP)

- Elizabeth I (Elizabeth; Mary, Queen of Scots; Elizabeth: The Golden Age; Reign)

- Ankhesenamun (Tut)

- Anne of Austria (The Musketeers)

- Mary, Queen of Scots (Reign; Mary Queen of Scots)

- Lagertha (Vikings) - Isabella of Valois (The Hollow Crown)

- Elizabeth Woodville (TWQ)

- Mary I of England (The Tudors)

- Catherine of Aragon (The Spanish Princess)

- Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians (The Last Kingdom)

- Morgana Pendragon (Merlin)

- Daenerys Targaryen (GOT) - Anne Boleyn (The Tudors)

- Gisla (Vikings) - Empress Maud (Pillars of the Earth)

- Kösem Sultan (Magnificent Century: Kösem)

- Catarina de Lurton (Dsor) - Empress Ki (Empress Ki)

- Queen Ravenna (Snow White & The Huntsman: Winter’s War; Snow White & the Huntsman)

- Elizabeth II (The Crown)

- Hürrem Sultan (Magnificent Century)

- Caroline Matilda of Great Britain (A Royal Affair)

- Marie Antoinette (Marie Antoinette)

- Georgiana Cavendish (The Duchess)

- Catherine the Great (Ekaterina)

- Cersei Lannister (GOT)

- Zhen Huan (Empresses in the Palace)

- Queen Gwen (Merlin)

- Sansa Stark (GOT)

- Mary II of England (Anna Brewster from Versailles)

- Isabella of France (World Without End)

- Marie de Guise (Elizabeth)

- Dido Elizabeth Belle (Belle)

- Anne Neville (TWQ)

- Wu Zetian (The Empress of China)

---------------------------------------------------------------

Song: Dynasty

Artist: Rina Sawayama

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

#multiqueens #rinasawayama #dynasty #pop #music #fanvidfeed #viddingisart #multifandom

#rina sawayama#dynasty#pop#music#pop music#multifandom#multi female#multi queens#queens#royalty#japan#uk#france#Russia#kirsten dunst#emilia clarke#margot robbie#elle fanning#natalie portman#cate blanchett#victorian age#ancient egypt#versailles

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

FE4/War of the Roses AU pls

OMG so many.

“Child,” said the Duchess as she arranged the strands of Deirdre’s silvery hair. “This is the destiny that’s awaited you from the day of your birth. He is the king.”

So Deirdre = Elizabeth Woodville, in the sense that young King Sigurd of the House of York contracts a secret marriage with her. Cigyun lives as an analogue of Jacquetta Woodville and sees her daughter married.

To hide the arrangement with Deirdre, Sigurd embarks on the boneheaded plan to “marry” (bigamously) Lady Edain of Jungby Salisbury so that his advisor Duke Reptor stops tryna arrange foreign marriages for him. This pisses Reptor the fuck off because he feels humiliated on the world stage.

"He is not interested in the lady from Provence, nor in any from France, nor Castile, nor Savoy, nor Denmark. My child, once we have exhausted these diplomatic games, our cousin King Sigurd will discover the most perfect rose of England has always been within this garden."

Even tho Reptor was planning his own long game, assuming Sigurd was too immature to go for any foreign brides and would ultimately be charmed by his favorite daughter Tailtiu. The Friege sisters = the Neville sisters (Isabel and Anne) here, and their ultimate marriages to Lex and Azelle respectively an echo of the Neville girls’ union to the royal dukes of Clarence and Gloucester.

"Right. So if Prince Cuan died suddenly, and we-- England, I mean, not us-- got ahold of his little daughter, and married her to the Prince of Wales that doesn't exist yet..."

"Then Reptor is the grandfather of the king of all Britain."

"Right. England, Scotland, and Ireland under one crown. At least once that Orkneys mess is settled. On the other hand, if something terrible were to befall our king right now, as it stands, Prince Cuan could lay claim on England through his wife and daughter and send that army he's constantly building down across the Wall and we're all ruled by the Scots."

"There's an awful lot of sudden death in these scenarios," said Lex.

Reptor has some other grand plans, too.

When Reptor + Lombard shove Sigurd off the throne, he hides out in the court of Duchess Rahna of Burgundy until, like Edward IV, he regroups and invades England once more. Unlike Edward, who thrashed the Lancastrians and reigned for 13 more years in increasing girth and tyranny, Sigurd is betrayed by Arvis when he tries to enter the Tower of London.

“Sigurd, Duke of York. I hereby arrest you on charges of treason against the King’s Grace.”

“On whose authority?”

“Mine own.”

Arvis pulls some King Henry VII bullshit and ante-dates his reign by one day before Sigurd’s death to declare all Sigurd’s supporters traitors.

Then King Arvis marries lovely Lady Deirdre, unaware of her prior entanglements and of the child being raised in Brittany, and then all hell starts to unfurl...

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

14th King of Portugal (5th of the Aviz Dynasty): King Manuel I of Portugal, “The Fortunate)

Reign: 25 October 1495 – 13 December 1521 Acclamation: 27 October 1495 Predecessor: João II

Manuel I (31 May 1469 in Alcochete – 13 December 1521 in Lisbon ), the Fortunate (o Venturoso, o Afortunado), King of Portugal, was the son of Fernando, Duke of Viseu,

by his wife, the Infanta Beatriz of Portugal.

His name is associated with a period of Portuguese history distinguished by significant achievements both in political affairs and in the arts. In spite of Portugal's small size and population in comparison to the great European land powers of France, Italy and even Spain, the classical Portuguese Armada was the largest in the world at the time. During Manuel's reign Portugal was able to acquire an overseas empire of vast proportions, the first in world history to reach global dimensions. The landmark symbol of the period was the Portuguese discovery of Brazil and South America in April 1500.

Manuel's mother was the granddaughter of King João I of Portugal,

whereas his father was the second surviving son of King Duarte of Portugal

and the younger brother of King Afonso V of Portugal.

In 1495, Manuel succeeded his first cousin, King João II of Portugal, who was also his brother-in-law, as husband to Manuel's sister, Leonor of Viseu.

Manuel grew up amidst conspiracies of the Portuguese upper nobility against King João II. He was aware of many people being killed and exiled. His older brother Diogo, Duke of Viseu, was stabbed to death in 1484 by the king himself.

Manuel thus would have had every reason to worry when he received a royal order in 1493 to present himself to the king, but his fears were groundless: João II wanted to name him heir to the throne after the death of his son Prince Afonso and the failed attempts to legitimize Jorge, Duke of Coimbra, his illegitimate son. As a result of this stroke of luck, Manuel was nicknamed the Fortunate, and succeeded on João's death in 1495.

Imperial Growth

Manuel would prove a worthy successor to his cousin João II for his support of Portuguese exploration of the Atlantic Ocean and development of Portuguese commerce. During his reign, the following achievements were realized:

1498 – The discovery of a maritime route to India by Vasco da Gama

1500 – The discovery of Brazil by Pedro Álvares Cabral.

1501 – The discovery of Labrador by Gaspar

and Miguel Corte-Real.

1505 – The appointment of Francisco de Almeida as the first viceroy of India

1503–1515 – The establishment of monopolies on maritime trade routes to the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf by Afonso de Albuquerque, an admiral, for the benefit of Portugal.

The capture of Malacca in modern-day Malaysia in 1511 was the result of a plan by Manuel I to thwart the Muslim trade in the Indian Ocean by capturing Aden, blocking trade through Alexandria, capturing Ormuz to block trade through the Persian Gulf and Beirut, and capturing Malacca to control trade with China.

All these events made Portugal wealthy from foreign trade as it formally established a vast overseas empire. Manuel used the wealth to build a number of royal buildings (in the "Manueline" style) and to attract scientists and artists to his court. Commercial treaties and diplomatic alliances were forged with Ming dynasty of China and the Persian Safavid dynasty. Pope Leo X

received a monumental embassy from Portugal during his reign designed to draw attention to Portugal's newly acquired riches to all of Europe.

Manueline Ordinations

In Manuel's reign, royal absolutism was the method of government. The Portuguese Cortes (the assembly of the kingdom) met only three times during his reign, always in Lisbon, the king's seat. He reformed the courts of justice and the municipal charters with the crown, modernizing taxes and the concepts of tributes and rights. During his reign, the laws in force in the kingdom of Portugal were recodified with the publication of the Manueline Ordinations.

Religious policy

Manuel was a very religious man and invested a large amount of Portuguese income to send missionaries to the new colonies, among them Francisco Álvares, and sponsor the construction of religious buildings, such as the Monastery of Jerónimos.

Manuel also endeavoured to promote another crusade against the Turks.

The Jews in Portugal

His relationship with the Portuguese Jews started out well. At the outset of his reign, he released all the Jews who had been made captive during the reign of João II. Unfortunately for the Jews, he decided that he wanted to marry Infanta Isabel of Aragon,

then heiress of the future united crown of Spain (and widow of his nephew Prince Afonso). Her parents Fernando and Isabel had expelled the Jews in 1492 and would never marry their daughter to the king of a country that still tolerated their presence. In the marriage contract, Manuel I agreed to persecute the Jews of Portugal.

In December 1496, it was decreed that all Jews either convert to Christianity or leave the country without their children. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the king. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who tried to use coercion and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country.

This period of time technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as "New Christians", and they were given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith would be allowed; this was later extended to end in 1534.

During the course of the Lisbon massacre of 1506, people invaded the Jewish Quarter and murdered thousands of accused Jews; the leaders of the riot were executed by Manuel.

Isabel died in childbirth in 1498, thus putting a damper on Portuguese ambitions to rule in Spain, which various rulers had harbored since the reign of King Fernando I (1367–1383).

Manuel and Isabel's young son Miguel

was for a period the heir apparent of Castile and Aragon, but his death in 1500 at the age of two years ended these ambitions.

Manuel's next wife, Maria of Aragon,

was his first wife's younger sister. Two of their sons later became kings of Portugal. Maria died in 1517 but the two sisters were survived by an older sister, Joana of Castile, who was born in 1479 and had married the Archduke Philip (Maximilian I's son) and had a son, Charles V who would eventually inherit Spain and the Habsburg possessions.

Manuel I was awarded the Golden Rose by Pope Julius II in 1506 and by Pope Leo X in 1514. Manuel I became the first individual to receive more than one Golden Rose after Emperor Sigismund von Luxembourg.

Manuel died of unknown causes on December 13 of 1521 at age 52. The Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon houses Manuel's and Maria’s tombs. His son João succeeded him as king.

Negotiations for a marriage between Manuel and Elizabeth of York

in 1485 were halted by the death of Richard III of England.

He went on to marry three times. His first wife was Isabel of Aragon, princess of Spain and widow of the previous Prince of Portugal Afonso. Next, he married another princess of Spain, Maria of Aragon (his first wife's sister), and then Leonor of Austria,

a niece of his first two wives, who married Francis I of France

after Manuel's death.

By Isabella of Aragon (2 October 1470 – 28 August 1498; married in 1497)

Miguel da Paz, Prince of Portugal (23 August 1498 - 19 July 1500) 1 year 10 months - Prince of Portugal, Prince of Asturias and heir to the crowns of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon.

By Maria of Aragon (19 June 1482 – 7 March 1517; married in 1500)

João, Prince of Portugal (7 June 1502 - 11 June 1557), 55 years - Succeeded the throne as João III, King of Portugal.

Infanta Isabel (24 October 1503 - 1 May 1539), 35 years - Holy Roman Empress by marriage to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Infanta Beatriz (31 December 1504 - 8 January 1538), 33 years - Duchess of Savoy by marriage to Charles III, Duke of Savoy.

Infante Luís (3 March 1506 - 27 November 1555), 49 years - Duke of Beja. Unmarried but had illegitimate descendants, one of them being António, Prior of Crato, a claimant of the throne of Portugal in 1580; see: Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Infante Fernando (5 June 1507 - 7 November 1534), 27 years - Duke of Guarda. Married Guiomar Coutinho, 5th Countess of Marialva and 3rd Countess of Loulé (died 1534). No surviving issue.

Infante Afonso (23 April 1509 - 21 April 1540) 30 years - Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church

Infante Henrique (31 January 1512 - 31 January 1580), 68 years - Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church who succeeded his grandnephew, King Sebastião (Manuel I's great-grandson), as Cardinal Henrique, King of Portugal. His death triggered the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Infanta Maria (3 February 1513) Died immediately after birth.

Infante Duarte (7 October 1515 - 20 September 1540), 24 years - Duke of Guimarães and great-grandfather of João IV of Portugal. Married Isabel of Bragança, daughter of Jaime, Duke of Bragança.

Infante António (9 September 1516) - Died immediately after birth.

By Leonor of Austria (15 November 1498 – 25 February 1558; married in 1518)

Infante Carlos (18 February 1520 - 14 April 1521), 1 year 1 month

Infanta Maria (18 June 1521 - 10 October 1577) 56 years - Unmarried

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

December 1, 1530 – Death of Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands. Margaret was the daughter of Maximilian of Austria and Mary of Burgundy, co-sovereigns of the Low Countries. She was named after her stepgrandmother, Margaret of York (sister of Edward IV & Richard III), Dowager Duchess of Burgundy, who was especially close to Duchess Mary. In 1482, Margaret's mother died and her older brother, Philip the Handsome, at that time three years of age, succeeded her as sovereign of the Low Countries, with his father Maximilian as his regent. Both Margaret and her brother married children of Isabel of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, the Catholics Monarchs. Her husband died after only six months and Margaret was left pregnant, but gave birth to a premature stillborn daughter. The Dowager Princess of Asturias returned to the Netherlands early in 1500. In 1501, she remarried Philibert II, Duke of Savoy. This marriage was childless as well, and he died after three years. She vowed never to marry again. During a remarkably successful career lasting from 1506 until her death in 1530, Margaret broke new ground for women rulers. After the early death of her brother Philip of Spain, in November 1506 she became the only woman elected as its ruler by the representative assembly of Franche-Comté (her title was confirmed in 1509). In November 1530, one of Margaret's maids broke a glass goblet. A splinter of glass went into Margaret's foot and the wound became gangrenous. Her doctors strongly recommended that she agree to having her foot amputated. She gave her consent for the operation, received the sacrament, and revised her will. Before the amputation could be performed, however, she died, apparently from an overdose of opium given to her in preparation for the operation. She died at the age of fifty, after appointing her nephew, Charles V, as her universal and sole heir. (at Howland Township, Trumbull County, Ohio)

0 notes

Photo

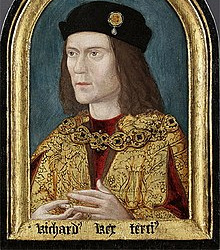

Isabel of Castile and Edward IV of England

In February 1464, when Isabel was not quite thirteen years old, her brother Enrique IV of Castile accepted the English offer and agreed to give her in marriage to King Edward IV, in a gesture of political alignment between the two countries. This would at once make Isabel a queen. It might have been a generous act on Enrique’s part, to help ensure an illustrious future for his half sister. However, it is just as likely that the marital alliance was Enrique’s attempt to remove Isabel from the direct line of succession in Castile and relocate her to a distant land, particularly at a time when rumors were brewing about Princess Juana’s legitimacy. Regardless of Enrique’s motives, however, the proposition of marriage to the English king would have been appealing to most young women. The twenty two-year-old Edward of York had recently assumed the throne of England. Charming, blond, strong, and six feet four inches tall, he was intelligent, excellent at the courtly games of hunting and jousting, dressed elegantly in furs and rich jewelry, and was fond of chivalric romances. This combination of traits made him irresistible to women, upon whom the lusty young king was eager to lavish his own attentions.

Marriage to Edward would of course have been an intriguing, even dazzling, prospect for Isabel, who loved hunting and stories of courtly love. It would give her a splendid husband, make her the envy of other women, and install her as queen of a kingdom with which she had long ancestral links. Isabel believed that Spain and England had a natural dynastic affinity. Her grandmother was Catherine of Lancaster, the daughter of the famous English nobleman John of Gaunt, son of King Edward III, whose marriage to Constance of Castile had made him a contender for the throne of Castile.

Edward IV was also descended from John of Gaunt, making him a distant cousin of Isabel. If the alliance proceeded, an old family tie would be reconnected. The marriage presented some strategic opportunities for England as well. Edward’s descent from King Pedro of Castile, through Pedro’s daughter Isabel Duchess of York, already made Edward a potential claimant to the Castilian throne, and this claim would be strengthened if he were to marry Isabel. English poets were already writing doggerel extolling Edward as not just king of England and deserving of France but also the future inheritor of Spain: “Re Angliae et Franciae, I say, It is thine own, why sayest thou nay? And so is Spain, that fair country.”

Once the match was proposed, Isabel waited at home for the decision. Given the difficulties in communication at the time, messages from one court to another sometimes took months because courtiers needed to physically travel from one place to another. Finally she somehow learned, to her great disappointment, that another woman had been selected, in a most unusual way. Unbeknown to the king’s councilors, who were negotiating Edward’s marriage prospects in both France and Spain, King Edward had already impulsively married a comely widow, Elizabeth Woodville. In faraway Castile, Isabel, still a young teenager, brooded over her rejection, much later telling ambassadors that she had been passed over for a mere “widow of England,” making it clear she had harbored resentment at her rejection for the next twenty years. Like Elizabeth Woodville, she was not a woman to suffer a slight lightly or forgive easily.

Source:

Kirstin Downey, Isabella: The Warrior Queen

#Isabel de Castilla#Isabella of Castile#Edward I of England#Henry IV of Castile#Enrique IV de Castilla#Elzabeth Woodville#Isabel tve#The White Queen#Spanish history#English history

37 notes

·

View notes