#late ottoman empire

Text

Modern Ladino Culture

🇪🇸 El libro "Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire" de Olga Borovaya, finalista de los National Jewish Book Awards en 2011, es el primero en examinar como un fenómeno unificado tres géneros de la producción cultural ladina: la prensa, la literatura de ficción y el teatro. Borovaya identifica estos géneros como importaciones de Occidente que se arraigaron entre los sefardíes otomanos a principios del siglo XX y se desarrollaron dentro del contexto cultural local, centrándose en las comunidades de Salónica, Esmirna y Estambul. La autora considera crucial abordar la cultura impresa ladina como un fenómeno único para entender el movimiento cultural de la época y su importancia en la historia sefardí. Analiza la evolución de los tres géneros, comenzando con la prensa, seguida de la literatura de ficción, y finalmente el teatro, destacando el papel significativo de las escuelas de la Alianza en la expansión de la cultura ladina. Borovaya también explora el fenómeno de la "reescritura" de novelas europeas occidentales, que luego se serializaban en la prensa ladina. Con notas detalladas y un índice, Borovaya presenta un análisis exhaustivo y accesible de un conjunto de materiales raros, proporcionando una valiosa contribución al estudio de la cultura sefardí.

🇺🇸 The book "Modern Ladino Culture: Press, Belles Lettres, and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire" by Olga Borovaya, a finalist for the National Jewish Book Awards in 2011, is the first to examine three genres of Ladino cultural production as a unified phenomenon: the press, fiction literature, and theater. Borovaya identifies these genres as imports from the West that took root among Ottoman Sephardim at the beginning of the 20th century and developed within the local cultural context, focusing on the communities of Salonica, Izmir, and Istanbul. The author considers it crucial to approach Ladino print culture as a single phenomenon to understand the cultural movement of the time and its importance in Sephardi history. She analyzes the evolution of the three genres, starting with the press, followed by fiction literature, and finally theater, highlighting the significant role of the Alliance schools in the expansion of Ladino culture. Borovaya also explores the phenomenon of "rewriting" Western European novels, which were then serialized in the Ladino press. With detailed notes and an index, Borovaya presents a comprehensive and accessible analysis of a rare collection of materials, providing a valuable contribution to the study of Sephardi culture.

#judaísmo#Modern Ladino Culture#Press#Belles Lettres#and Theater in the Late Ottoman Empire#judaism#jewish#jumblr#Ottoman Empire#imperio otomano#Olga Borovaya#Indiana University Press#Ladino press#ladino#judeoespañol#judezmo#judío#cultura sefardí#literatura sefardí#sephardic literature#cultura judía#sefardí#sephardic

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hagia Sophia, former Byzantine Church and Ottoman Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey. Original church was built in 360 AD and updated several times. The current structure stems from the reign of Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor Justinian I, completed in 537 AD. It became a mosque with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 AD...

#hagia sophia#istanbul#turkey#turkiye#constantinople#byzantine#eastern roman empire#justinian#ottoman#church#mosque#ottoman empire#byzantine empire#byzantine art#icons#late antiquity#medieval

1 note

·

View note

Text

kruszyniany mosque in kruszyniany, poland. this is the oldest lipka tatar mosque in poland.

the town of kruszyniany was assigned to tatars who participated on the side of the polish-lithuanian commonwealth in their war against the ottoman empire. after lipka tatars settled in the city, they built this mosque, most likely in the late eighteenth century; though there are documents which mention it going back to 1717. the village was settled by repatriates and belarusian muslims following world war ii.

#poland#tatar#architecture#interior#worship#muslim#nmenam#wooden worship#my posts#there's men's and women's entrances in the back

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

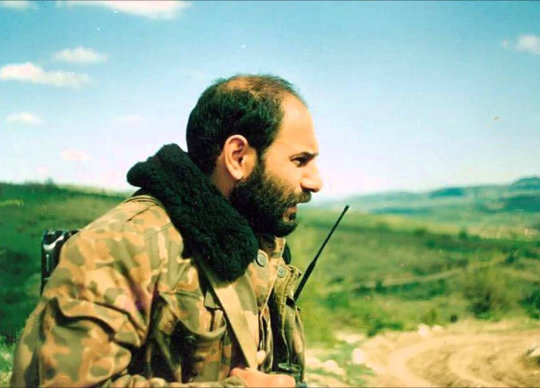

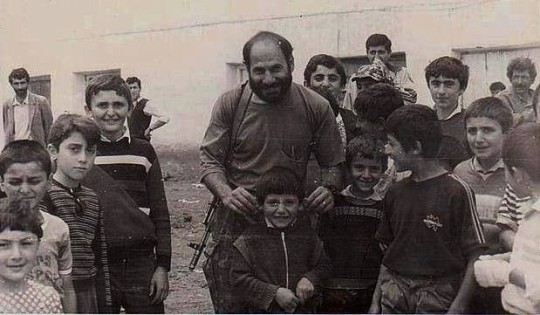

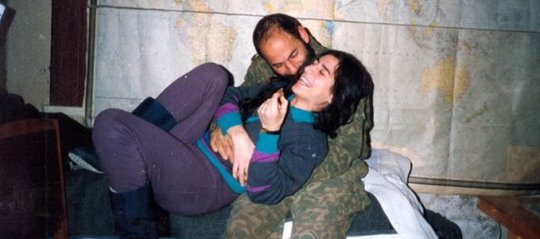

Monte Melqonyan/Մոնթե Մելքոնյան (1957-1993)

Honestly, I don't even know where to begin. He's one of those extraordinary individuals about whom countless books could be written and numerous movies could be made, yet still, so much would remain untold. You might wonder, "He's a National Armenian Hero—cool, but why should I know about him?" My answer is simple: if the world had more people like him, especially in today's times, it would be a much better place. He fought for justice, embodied culture and education, and radiated a deep love for his people and humanity as a whole. I believe everyone should aspire to have a little bit of Monte's spirit within them, regardless of their nationality.

Now, it's important to note that some things written about him in the Western press can be questionable and inaccurate. So, I would advise taking most of the information from those sources with a grain of salt.

Monte was born on November 25, 1957, into an Armenian family in Visalia, California, that had survived the Armenian Genocide. From 1969 to 1970, his family traveled through Western Armenia, the birthplace of his ancestors. During this journey, Monte, at the age of twelve, began to realize his Armenian identity. While taking Spanish language courses in Spain, his teacher had posed him the question of where he was from. Dissatisfied with Melkonian's answer of "California", the teacher rephrased the question by asking "where did your ancestors come from?" His brother Markar Melqonyan remarked that "her image of us was not at all like our image of ourselves. She did not view us as the Americans we had always assumed we were." From this moment on, for days and months to come, Markar continues, "Monte pondered [their teacher Señorita] Blanca's question Where are you from?"

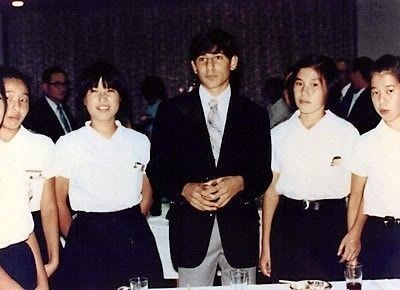

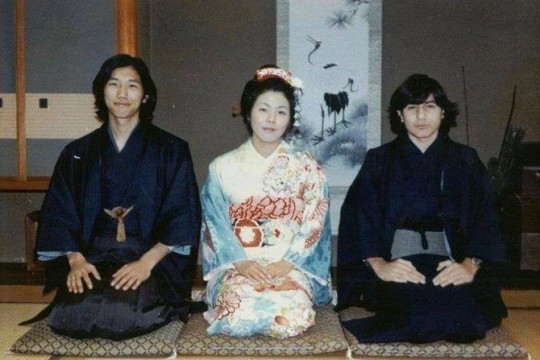

In high school, he excelled academically and struggled to find new challenges. Instead of graduating early, as suggested by his principal, Monte found an alternative - a study abroad program in East Asia. The decision to go to Japan was not random. He had been attending karate clubs and was the champion of the under-14 category in California. He also studied Japanese culture, including taking Japanese language courses. After completing his studies at a school in Osaka, Japan, he went to South Korea, where he studied under a Buddhist monk. He later traveled to Vietnam, witnessing the war and taking numerous photographs of the conflict. Upon returning to America, he had become proficient in Japanese and karate.

Having graduated from high school, Monte entered the University of California, Berkeley, with a Regents Scholarship, majoring in ancient Asian history and archaeology. In 1978, he helped organize an exhibition of Armenian cultural artifacts at one of the university's libraries. A section of the exhibit dealing with the Armenian Genocide was removed by university authorities at the request of the Turkish consul general in San Francisco, but it was eventually reinstalled following a campus protest movement. Monte completed his undergraduate work in under three years. During his time at the university, he founded the "Armenian Students' Union" and organized an exhibition dedicated to the Armenian Genocide in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey.

Upon graduating, he was accepted into the archaeology graduate program at the University of Oxford. However, Monte chose to forgo this opportunity and instead began his lifelong struggle for the Armenian Cause.

In the fall of 1978, Monte went to Iran and participated in demonstrations against the Shah. Later that year, he traveled to Lebanon, where the civil war was at its peak. In Beirut, he participated in the defense of the Armenian community. Here, he learned Arabic and, by the age of 22, was fluent in Armenian, English, French, Spanish, Italian, Turkish, Persian, Japanese, and Kurdish.

From 1980, Monte joined the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA – I promise to tell you more about them later) and quickly became one of its leaders. In 1981, he participated in the planning of the famous Van operation. In 1981, he was arrested at Orly Airport in France for carrying a false passport and a pistol. During his trial, Monte declared, "All Armenians carry false passports—French, American—they will remain false as long as they are not Armenian." Over the following years, he perfected his military skills at an ASALA training camp, eventually becoming one of the group's principal instructors.

Monte with his wife Seda

After being released from a French prison (once again) in 1989, Monte arrived in Armenia in 1991, where armed clashes between Armenians and azerbaijanis had already begun. He founded the "Patriots" unit and spent seven months in Yerevan working at the Academy of Sciences, writing and publishing the book "Armenia and its Neighbors." In September of the same year, he went to the Republic of Artsakh to fight for his fatherland and its people. Due to his military expertise, he was appointed Chief of Staff of the Martuni defense district in 1992. His sincerity and purity quickly won the love and respect of the local population and the Armenian community as a whole.

Throughout his conscious life, Monte fought for the rights of Armenians, recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and the reclamation of Armenian homeland.

There are various versions of Monte Melqonyan's death circulating in both Armenian and azerbaijani media. According to official Armenian information, Monte was killed on June 12, 1993, by fire from an azerbaijani armored vehicle.

Monte remains a lasting testament to the incredible potential unleashed when the Armenian patriotic heart unites with sharp intellect.

youtube

In case you'd like to put a voice to the face and hear about the Artsakh struggle directly from Monte, here he is speaking about it in English.

#so many things have been left out#but I guess this is a good starting point#I promise to tell you more about ASALA and Van Operation in near future#monte melqonyan#armenia#armenian history#armenian culture#world history#artsakh#artsakh is armenia#translated literature#մոնթե մելքոնյան

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

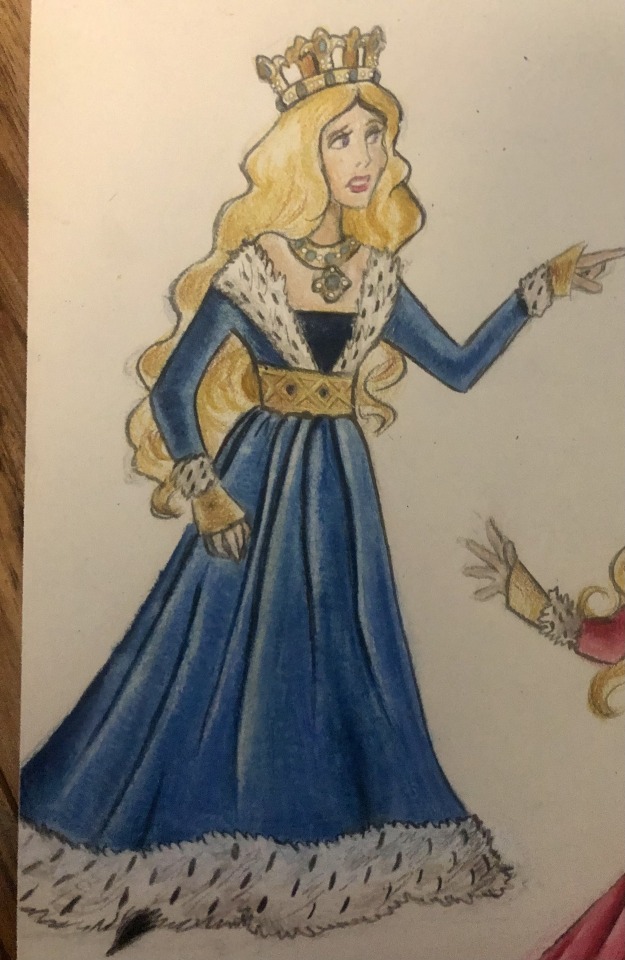

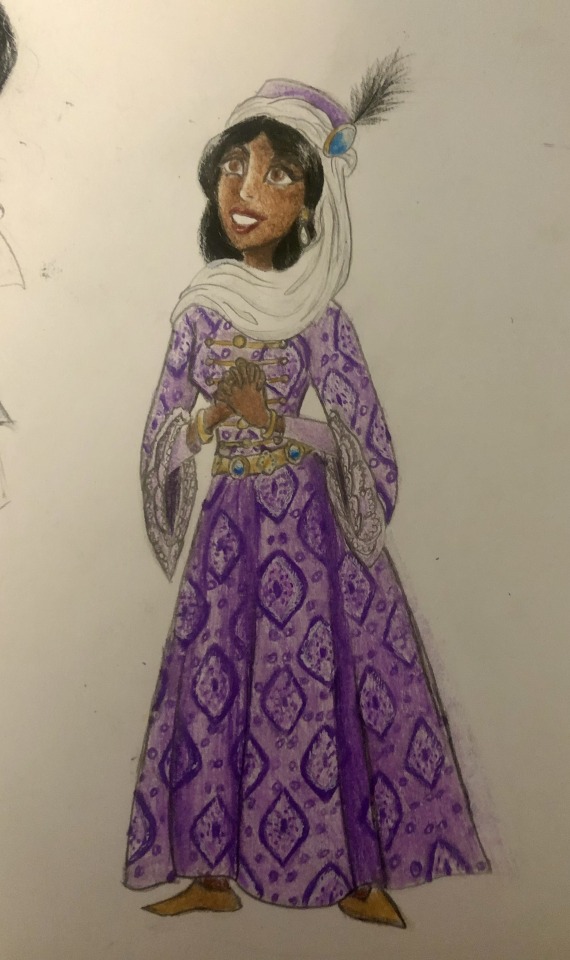

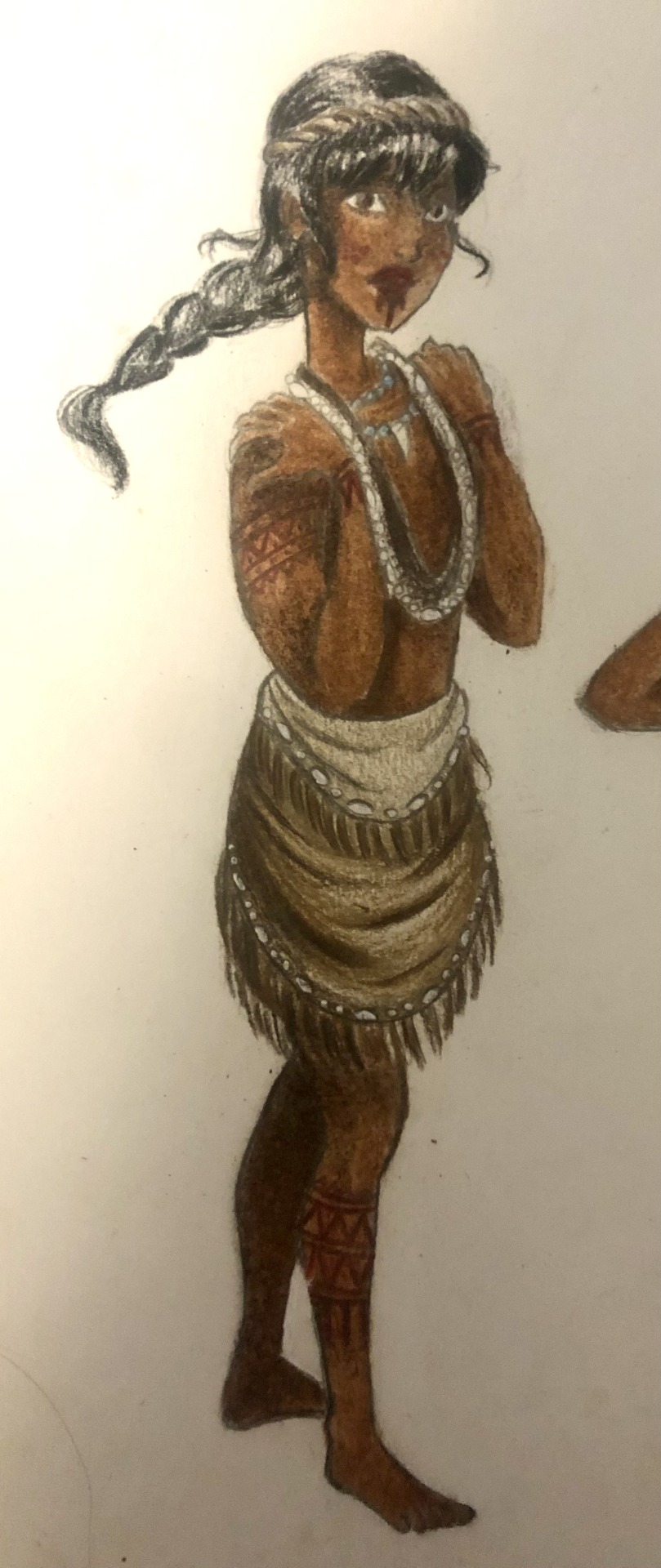

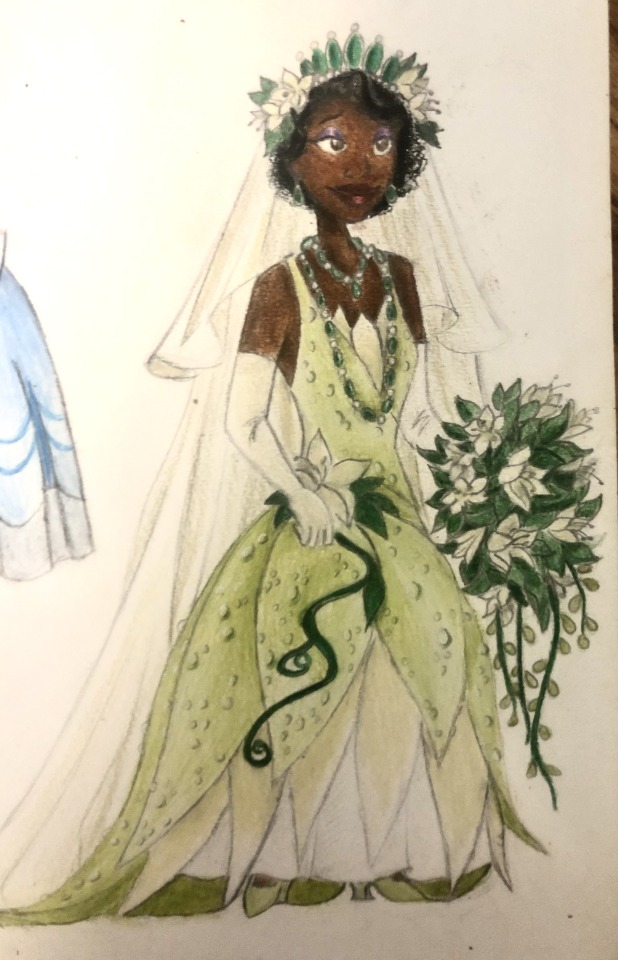

Thought I’d do a little art throwback with my own historically accurate (well mostly) takes on Disney princesses and heroines, which I did from 2021 to 2022! Included in this series are:

Snow White - early 16th century Germany (then part of the Holy Roman Empire)

Cinderella - late 1860s-early 1870s France

Aurora - mid 15th century France

Eilonwy - 8th-10th century (present day) Wales

Ariel - 1830s Mediterranean Europe (maybe Italy)

Belle - 1760s-1770s France

Jasmine - 16th century Arabian Peninsula during the Ottoman Empire

Pocahontas - 1607 Virginia, (present day) United States of America

Esmeralda - 1480s France (Romani garb)

Megara - Classical period of Ancient Greece (c. 5th-4th centuries BCE)

Mulan - Wei Dynasty China (386-535 AD)

Jane - 1900s England

Tiana - late 1920s New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

Rapunzel - 1790s-1800s Germany

Merida - 10th-11th century (present day) Scotland

Elsa - late 1830s-early 1840s Norway

Anna - same period as Elsa (duh)

Moana - ancient Polynesian Islands (c. 1st century BCE)

I had so much fun drawing these, as well as doing the research for each one! I actually drew most of the outfits each one wears (in their first movies) but they're waaaaay down further in my blog.

I'm planning to do a digital redo of these someday, as well as do my own historical spins on other characters I haven't done yet.

Which one is your favorite?

Commissions info

#my art#angie's scribbles#disney#disney princess#disney princesses#disney heroines#disney girls#disney ladies#historical disney#historically accurate disney#historical fashion#snow white#snow white and the seven dwarfs#snow white 1937#cinderella#cinderella 1950#princess aurora#aurora#sleeping beauty#sleeping beauty 1959#eilonwy#princess eilonwy#the black cauldron#ariel#the little mermaid#the little mermaid 1989#belle#beauty and the beast#beauty and the beast 1991#jasmine

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

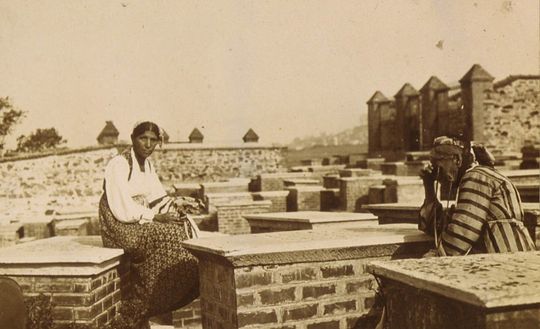

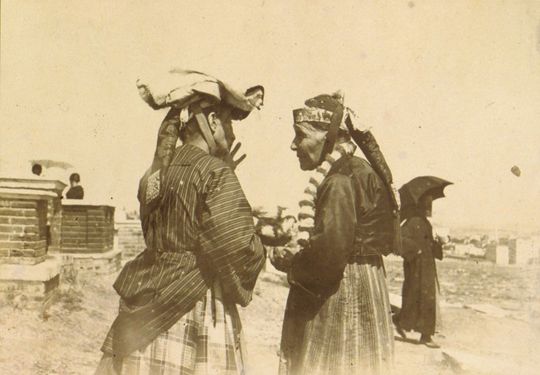

Sephardic Jews from Thessaloniki in their traditional costumes, in the city’s old cemetery, before the war // a contemporary photo that shows where the destroyed cemetery once was, which is now Greece's largest university, built partially on top of and with land and materials (particularly tombstones) stolen from the razed site.

Thessaloniki or Salonika, once referred to as “the Jerusalem of the Balkans” due to its Ladino-speaking Jewish majority, saw roughly 96% of its Jewish population murdered during the Holocaust. This mass destruction extended to the city's Jewish cemetery, which had been the country's largest, established in the 15th century and housing hundreds of thousands of Jewish graves until its razing by city authorities who had long desired to repurpose the land and resented the inconvenience of Jewish presence. Despite its large-scale destruction during German occupation in 1942, which was initiated and carried out primarily by Thessaloniki authorities with Nazi consent and arrangement, some parts of the cemetery survived intact as late as 1947. Many tombstones were subsequently appropriated and used by city authorities and the Greek Orthodox Church. After the war, people were still carrying away Jewish gravestones each day and regularly looting the cemetery in search of valuables. The city's officials, led by their mayor, completed the cemetery's destruction and sold the tombstones to contractors for use as building materials in various projects; as such many were and are still found in various walls, roads, structures, and churches around the city. A 1992 commemorative book pictures Greek schoolgirls playing Hamlet with skulls and other bones they found in the cemetery.

“[T]he ‘rape’ of the cemetery escalated, marble flooded the market, and its price plummeted. Jewish tombstones were stacked up in mason’s yards and, with the permission of the director of antiquities of Macedonia and overseen by the metropolitan bishop and the municipality, used to pave roads, line latrines, and extend the sea walls; to construct pathways, patios, and walls in private and public spaces though out the city, in suburbs such as Panorama and Ampelokipi, and more than sixty kilometers away in beach towns in Halkidiki, where they decorated playgrounds, bars, and restaurants in hotels; to build a swimming pool – with Hebrew-letter inscription visible; to repair the St. Demetrius Church and other buildings...” Devin Naar, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece

Most of the efforts to return found tombstones throughout the city are led by Jews, particularly Jacky Benmayor, the curator of the Jewish Museum and last Ladino speaker in Greece, who has personally recovered hundreds of tombstones including his own family's. Surviving Greek Jews never received compensation for the confiscation of the land under the destroyed cemetery, upon which now partially rests Greece's largest university, Aristotle University, which also used Jewish gravestones as building material for its long-coveted expansion finally made possible by the dispossession and annihilation of the city's Jews. In 2014, 72 years after the cemetery's destruction and appropriation, a small memorial was established on campus grounds to acknowledge the Jewish cemetery the school is built on and with; the ceremony just 10 years ago involved the first-ever acknowledgement of the atrocities and apology from a Thessaloniki mayor. The memorial has been vandalised multiple times since its establishment.

#jumblr#jewish#jewish history#jewish photography#sephardic#holocaust#salonika#my posts#greece#don't feel very coherent about this one. doesn't a country's biggest university being built on and with jewish graves just say it all#72 years of silence and then a small memorial subject to frequent vandalism btw#this is the 'compensation' greek jews got#from an annihilation that didn't even spare the dead. a near-total obliteration of life and memory#the memorial pisses me off a little bc it's deliberately vague about very key local participation in these atrocities#reading it you wouldn't know they were mostly driven by local authorities; just facilitated and finally made possible by the nazis#but I do think about what it says a lot:#'but people were not enough. they wanted to kill the memory too.'#and wasn't that true? of both nazis and neighbors?#I really recommend devin naar's work for anyone further interested in this subject

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palestinian History Between Great Powers - Part 1

From Bronze Age to Ottoman Palestine

I started writing this article months ago but as it deserves proper research, it took me a long while, and at one point I started questioning is this helpful anymore. I thought it's obvious at this point to anyone not willfully ignorant that what we are seeing in real time is a genocide, and I'm not going to convince those who are willfully ignorant. I decided to finish it anyway since I do feel obligation to do something and maybe providing some accessible historical context is what I'm capable of doing. Even if I probably won't change any hearts and minds, I think the least we can do is not forget Palestinians and fall into apathy. And at the very least more understanding of the situation is always better even when we already oppose this genocide.

This is quite out of my area of focus, so I will be doing more of a general overview of the history and link in depth sources by more knowledgeable people than try to become an expert on this. My purpose is to offer an accessible starting point for the history of Palestine to help people put historical and current events into their proper context. I don't think the occupation and genocide in Palestine pose complex moral questions - it's pretty simple in my opinion that genocide, apartheid and colonialism are wrong and need to stop for peace to be possible - but the history is complex and it's understanding needs quite a lot of background. I will do my best to represent the complexity accurately and fairly while keeping this concise. Since there is a lot of history, even if this is very general overview, it's still very long, so I did need to cut this in two parts. First part will be covering everything to the beginning of WW1, second part the British Mandate period and Israel period.

Bibliography

I'm linking my sources and further reading here so it's easy to check some specific resources even if you don't want to/have time to read 5 000 years of history right now. Because there's so much misinformation and propaganda, I read as much as I could from academic sources, linked at the top here. They are really interesting and delve deeply into specific subjects so I do recommend checking out anything that peaks your interest (Sci-Hub is your friend against paywalled papers and in JSTOR you can make a free account to access most papers). Some of them I didn't really end up using, but I still linked them here since they provide some additional context that wouldn't fit in this overview. At the end there's some accessible resources (youtube videos, podcasts etc.) which are relevant and I think good.

Pre-Ottoman Era

On The Problem of Reconstructing Pre-Hellenistic Israelite (Palestinian) History - Critique of Biblical historical narratives

Canaanites and Philistines

Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: Between Large Forces: Palestine in the Hellenistic Period - Everyday life in Hellenistic Palestine

Ottoman Era

Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History - Critique of politics of Ottoman Palestine historiography

The Peasantry of Late Ottoman Palestine

Consequences of the Ottoman Land Law: Agrarian and Privatization Processes in Palestine, 1858–1918

The route from informal peasant landownership to formal tenancy and eviction in Palestine, 1800s–1947

The Ottoman Empire, Zionism, and the Question of Palestine (1880–1908)

Origins of Zionism

Christian Zionism and Victorian Culture

Zionism and Imperialism: The Historical Origins

The Non-Jewish Origin of Zionism

Zionism and Its Jewish "Assimilationist" Critics (1897-1948)

The Jewish-Ottoman Land Company: Herzl's Blueprint for the Colonization of Palestine

Books

Boundaries and Baraka - Chapter II of Muslims and Others in Sacred Space - Local syncretic religious beliefs of Muslim and Christian Arabs in Palestine

Further "reading"

Israelis Are Not 'Indigenous' (and other ridiculous pro-Israel arguments) - Properly cited youtube video on settler colonialism of Zionism (Indigenous is defined here in postcolonialist way, in contrast with the colonialist, the video doesn't argue that diaspora Jews didn't originate from the Palestine area)

Gaza: A Clear Case of Genocide - Detailed Legal Analysis - Youtube video detailing current evidence on the ongoing genocide and assessing them through international law

What the Netanyahu Family Did To Palestine: Part 1 , Part 2 - Two part podcast episode of Behind the Bastards about Israel's history and Netanyahu Family's involvement in it with an expert quest

History of Israeli/Palestinian conflict since 1799 - Timeline of Palestinian history by Al Jazeera with documentaries produced by Al Jazeera for most of the entries in the timeline

Ancient Era (33th-4th century BCE)

Palestine's location in the fertile crescent, the connecting land between Africa and Asia and the strip of land between Mediterranean and Red Sea means since the earliest emergence of civilizations it has been in the middle of great powers. Thorough it's history it has been conquered many, many times for it's strategic value. Despite the changing rulers and migrating groups there has been a continuous history history of a people, which has changed, split and evolved, but not fully disappeared or replaced at any point, which is quite rare of a history spanning thousands of years.

Speakers of Semitic languages are the first recorded inhabitants of Palestine. At least from Bronze Age (c. 3300-1200 BCE) onward they inhabited Levant, Arabian peninsula and Ethiopian highlands. Semitic languages belong in the Afroasiatic language group, which includes three other branches; ancient Egypt, Amazigh languages and Cushitic languages of African Horn. Most prominent theories of the origins of proto-Afroasiatic is in Levant, African side of Red Sea or Ethiopia. In the Bronze Age the Levant's Semitic speakers were called Canaanites and there was already urban settlements in Early Bronze Age. Egypt had been extending it's control over Canaan for a while and in Late Bronze Age, 1457 BCE, it took over Canaan. Gaza, which had had habitation for thousand years already, became the Egypt's administrative capital in Canaan. Canaan stayed as Egypt's province until the Late Bronze Age collapse c. 1200-1150 BCE, when Egypt started losing it's hold on Levant. Egypt eventually retreated from Canaan around 1100 BCE. The causes of Late Bronze Age collapse are unknown, but theories suggest some kind of environmental changes that caused destruction of cities and wide-spread mass migration all around the East Mediterranean Bronze Age civilizations.

Canaanites was not what most of the people called themselves, but rather what the surrounding empires, especially Egypt and Hittites in the north, called them. Philistines appear in Egyptian sources around the Late Bronze Age collapse as raiders against Egypt, who were likely populating southern parts of Canaan, the Palestine area. Several groups with mutually intelligble languages emerged after Egypt left the area: in Palestine area Philistines, Israelites, in Jordan are Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites, and in Lebanon area Canaanites, who were called by Phoenicians by Greeks. Israelites have been theorized to split from Philistines, possibly after Aegonean migrants during the Late Bronze Age collapse influenced the culture of the costal Philistine city states, and/or through Israelites development of monotheistic faith. During Iron Age these different groups descendant from Caananites had their own kingdoms. In the area of Palestine there was two Israelite kindgoms, Kingdom of Judah is the highlands of Judah, were Israelites likely originated, and Kindom of Israel or Samaria north to it, as well as Philistine city states in the coast around the area of current Gaza strip.

Earliest historical evidence of Israel is from mid 9th century BCE and of Judah from 7th century BCE, though Israelites as a group were mentioned earlier. It's entirely possible the kingdoms predate these mentions, but the archaeological evidence suggests likely not by much. Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian empire in 722 BC, so it's entirely possible kingdom of Judah was created by retreating Israelites of the earlier kingdom. The remaining Israelites under Assyrian rule came to be known as Samaritans, marking also the split of Jewish faith into Judaism and Samaritanism. Neo-Assyrian lingua franca was Aramaic, a Semitic language from southwest Syria, which became the major spoken language in Samaria. Judah became a vassal state of Assyrians and later Babylonians. After a rebellion Babylonians fully conquered Judah in 586-587 BCE and exiled the rebels, though more recent historical study suggests it targeted the rebelling population and was not a mass exile. In 539 BCE Babylon and by extension Judah was conquered by Persian Achaemenid empire, which allowed the exiles to return and rule Judah as their vassals. Persia also conquered Samaria and Philistines. Aramaic was also the official language of the both Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid empires and replaces Old Hebrew as spoken language in Judah too, though Old Hebrew continued to be written language of religious scripture and is known today as Biblical Hebrew. Otherwise in the Palestine area there were Edomites, who migrated to the southern parts of former Judah kingdom, and Qedarites, a nomadic Arabic tribal federation, in southern desert parts.

Biblical narratives tell this early history very differently, and for a long while, those were used as historical texts, but more recent historical study has cast a doubt on their usefulness in historical inquiry. Even more recent archaeological DNA studies (like this and this) have supported the historical narratives constructed from primary historical texts.

Antique Era (4th century BCE - 7th century CE)

Under Persian rule the people in the Palestine area had a relative amount of autonomy, which lasted about 200 years. In the 330s BCE Macedonians conquered Levant along with a lot of other places. The Macedonian empire broke down quickly after the death of Alexander the Great, and Levant was left under the control of the Seleucid empire, which included most of the Asian parts of the Macedonian empire. During this time the whole Palestine area was heavily Hellenized. In the 170s BCE the Seleucian emperor started a repression campaign against the Jewish religion, which led to a Maccabean Revolt in Judea, lasting from 167-160 BCE until the Seleucids were able to defeat the rebels. It started with guerilla violence in the countryside but evolved into a small civil war. Defeat of the rebelling Maccabees didn't curb the discontent and by 134 BCE Maccabees managed to take Judea and establish the Hasmonean dynasty. The dynasty ruled semi-autonomously under the Seleucian empire until it started disintegrating around 110 BCE, and Judea gained more independence and began to conquer the neighbouring areas. At most they controlled Samaria, Galilee, areas around Galilean Sea, Dead Sea and Jordan River between them, Idumea (formerly Kingdom of Edom) and Philistine city states. During the Hasmonean dynasty Judaism spread to some of the other Semitic peoples under their rule. It didn’t take long for the rising power of the Roman Republic to make Judea into their client state in 63 BCE. Next three decades the Roman Republic and Parthian Empire would fight over control of Judea, which ended by Rome gaining control and disposing of the Hasmonean dynasty from power. It was a client state until 6 CE Rome incorporated Judea proper, Samaria, Idumea and Philistine city states into the province of Judea.

The Jewish population was very much discontent under Roman rule and revolted frequently through the first century or so. It led to waves of Jewish migration around the Mediterranean area, which would eventually lead to the formation of European and North-African Jewish groups. The Roman emperor’s decision to build a Roman colony into Jerusalem, which they destroyed along with Second Temple while squashing the previous revolt, provoked a large-scale armed uprising from 132-136 among Judean Jews, which Rome suppressed brutally. Jerusalem was destroyed again, Jews and Christians were banned from there, and a lot of Judean Jews were killed, displaced and enslaved. Rome also suffered high losses. Jews and Christians hadn’t yet fully separated into different faiths yet, but this strained their relations as Christians hadn’t supported the uprising. Galilee and Judea was joined into one province, Syria Palaestina. Galilean Jews hadn’t participated in the revolt and had therefore survived it unscathed, so Galilee became the Jewish heartland. During the Constantine dynasty, in the first half of the 4th century, when Christianity was the Roman state religion, Jerusalem was rebuilt as very Christianized. After the Constantine dynasty the Jewish relations with Rome were briefly improved by a sympathetic emperor, until Justinian came into power in 527 and began authoritarian religious oppression of all non-Christians, casting the whole area into chaos. Samaritans rebelled repeatedly and were almost fully wiped out, while Jews joined forces with several foreign powers in an attempt to destabilize Byzantium rule. By 636 the first Muslim Caliphate emerged as victors over the control of Palestine.

Muslim Period and Crusades (636-1516)

For more than 300 years under the rule of Muslim Caliphate, Palestine saw a much more peaceful period, with relative freedom and economic prosperity. Christianity continued to be the majority religion and Christians, Jews and usually Samaritans were considered People of the Book, who were guaranteed religious freedom. Non-muslims though had to pay taxes and depending on the caliph had more or less restrictions posed upon them. The position of Samaritans as People of the Book was unstable and at points they were persecuted. For the position of Jews it was a marked improvement, and after the expulsion of Jews from Jerusalem by Rome in the 2nd century, they were finally allowed to return. Jerusalem became a religious center for the Muslims too, as it was considered the third most holy place of Islam. Cities, especially Jerusalem, saw Arab immigration. The rural agricultural population was mostly Aramaic speaking, though even while Palestinian Arabs had mostly been bedouins in the southern deserts, there were few Arabic villages from the Roman era. People of the Book were protected from forced conversions, but over time conversions among the Christian population slowly increased, until Islam became the majority religion. Cities became Arabicized and slowly Arabic (also Semitic language) replaced Aramaic as the majority language. Towards the end of the first millennium persecution of Christianity increased with the threat of Byzantium.

In 970 a competing dynasty, Fatimids, conquered Palestine beginning a new era of continuous warfare and conquest by foreign powers. In the beginning of the new millennium Palestine was conquered by the Turco-Persian Seljuk empire for a couple of decades, recaptured by Fatimids for only a year, until the Crusaders took Palestine in 1099. During the next two centuries Palestine exchanged hands several times between the Crusaders and the Egyptian Ayyubid Sultanate. After internal struggle the Ayyubid dynasty was overthrown by the mamluk military caste and them in lead, the Sultanate secured Palestine. First they repelled the invading Mongol empire in 1260 and by 1291 they had defeated the remnants of the Cusaders and their Kingdom of Jerusalem. The period was devastating to the Palestinian populations, cities and economic life. The Crusaders especially committed numerous massacres against non-Christians and under Muslim rule Christians were persecuted and forcibly converted. The next two centuries under the Mamluk Sultanate were peaceful and Christian and Jewish communities were afforded some self-governance and relatively high religious freedom for being recognised as People of the Book again. The state had a more contentious relationship with Christians as the wars with the Crusaders were still looming between Christians and Muslims, and at some points Christians faced persecution and forced conversions.

Ottoman Period (1516-1917)

The Ottoman Empire gained dominance in western Asia over the Mamluk Sultanate during the late 15th century and conquered Palestine in 1516. It became a great imperial power in Asia and Europe for two centuries and in the 18th century started a slow decline, eventually becoming the "Sick man of Europe". The Ottoman Empire was very decentralized and under it Palestine was at first ruled by three Palestinian families semi-autonomously. The Ottoman state didn’t pay much attention to economic development, as they considered it contrary to their chivalric culture, so they instead attracted foreign businesses with the capitulation system. Capitulations were treaties between Ottomans and a foreign power by which the citizens of that foreign power were under their jurisdiction inside Ottoman borders. This guaranteed safety and religious freedom for non-Muslim merchants and exempted them from any additional taxes applying to foreigners and non-Muslims, which encouraged them to build businesses in the Ottoman Empire. Ottomans also intentionally attracted European Jews, who faced persecution and pogroms, and had built effective international trade networks through the tight knit diaspora communities. Jews and Christians had quite well secured position in the empire as People of the Book, but Samaritans were persecuted after they had sided with the Mamluk Sultanate against Ottomans and later for being considered "pagans". City elites adopted Turkish culture, while in rural areas peasant villages and Bedouin clans remained Arabic. The rural areas were very much self-governing as both villages and Bedouin clans were fairly self-reliant with their own political structures. Villages consisted of clan-like family groups, hamulas, and the village lands were distributed between their collective ownership.

In the 19th century the Ottoman Empire was leaving behind European imperial powers in economic and military development. With the rise of the international capitalist markets, capitulation approach, which had worked well for the empire in previous centuries, was extended to markets as a very laissez faire economic policy. This did not lead to hoped economic growth however, but rather deindustrialization. The Ottoman Empire opened itself to markets it couldn’t compete in and its resources were then easy to exploit by stronger economies. The other powers, such as the European powers, avoided this by first cultivating strong national industries with protectionist policies, and then opened to international markets. The capitulation system also became a political liability the way it interacted with the protégé system. The Ottoman Empire had agreed to allow some European powers to give their protection over certain minority religious groups (mostly Christian groups) in the Empire, allowing members of those groups to claim citizenship of their protectorate nation. This had allowed those Ottoman citizens to claim the benefits of the capitulation system and cultivated trade and business for the Empire. In the 19th century the European powers, notably France, British Empire, Germany and Russia, turned their interests towards Levant which was important for their access to their colonial interests in Asia and Africa. They had a vested interest in the continuing power of the weakening Ottoman Empire, which they believed they could control through economic dominance and the protégé system. It became a competition on who could gain the most influence in the Ottoman Empire. In Palestine this led to a change in class dynamics. Christian protégés of European imperial powers were given tax exemptions from the increasing taxes, which were implemented to balance the national deposit, and better opportunities to gain wealth from international trade, turning the urban Christian Arabs into elite.

In 1832 Egypt invaded Palestine, marking a point of more rapid decline of Ottoman rule. Egypt attempted to “modernize” Palestine, which was considered backward, but Egypt's policies, especially conscription, were considered intrusive. The local self-ruling clans and families were resistant to outside powers and with their sway over the population, they rose to a popular uprising after two years of Egyptian rule. The suppression of the uprising devastated many villages and Egypt still failed to enforce order and halt violence. In 1840 Britain intervened, returning its control back to the Ottomans. They didn’t yet have capitulations with the Ottomans and were concerned over the other European powers gaining influence over the aging empire, so in return for their military assistance, they gained capitulations and named Jews and Protestants as their protégés in Levant. Palestine rapidly opened to the international markets with the increase in capitulations combined with the laissez faire fiscal policies of the empire, allowing European powers to turn Palestinian cities, especially in the coast, to centers of trade. In 1858 the Ottoman Empire also attempted to privatize land ownership to increase agricultural production and profitability in order to help with their financial troubles. Most Palestinian land was public land, but in practice owned informally by the villagers cultivating it. As long as they paid taxes, they couldn’t be evicted, which rarely happened in those cases either, and their rights to the land were hereditary. The land reform codified and formalized land ownership and removed barriers to non-villagers gaining ownership of peasant land, laying groundwork for commodifying land. The Ottoman Empire also allowed foreigners to purchase private land. This didn’t immediately lead to large-scale transfer of land ownership, but increasing taxes impoverishing the peasantry and indebting them transferred land from its cultivators to urban absentee landlords. Peasants started to turn into landless tenants and a new type of large estates were established.

Birth of Zionism

The British pushed for more control over Levant, since they wanted to secure their access to India and their colonial ventures in Africa. They didn’t have much interest in colonizing Levant themselves, which is why they were interested in backing the Ottoman Empire and gaining stronger control over it via European Jewish immigrants. European Jews had been immigrating to Palestine in small numbers for a while for religious reasons, to escape persecution and to take advantage of the economic opportunities offered by the Ottoman Empire. The British though also had religious interests in supporting Jewish migration to Palestine. Since the early 19th century, there had been a growing religious movement of Christian Zionism, who sought to restore Jews into Palestine and then convert them to Christianity to cause the second coming of Jesus and the end times. As you do. They were considered fanatics, even lunatics, for their literal interpretations of prophecy, but they were enthusiastic imperialists and when they expressed the idea of restoration of Jewish Palestine in imperial terms, it gained popular acceptance in Britain. Some of the common talking points originating from Christian Zionism were Jews had the right to Palestinian land for Biblical reasons, the only way to not let the “underdeveloped” agrarian land go to waste was colonialism, and Jews would be a civilizing force in Palestine. While the end goal of Christian Zionists was conversion of Jews, they had Orientalist reverence for Jews, but among the wider imperialist support for these ideas there was in addition an explicitly antisemitic aspect. The imperialists' idea was that Britain, and Europe more broadly, could this way also get rid of the Jews.

The trouble was that at the time there was no wide interest at all among Jews to colonize Palestine. The Jews who were migrating there during the first half of the 19th century did so with all intentions of integrating to the Palestinian society. European Jews had since Enlightenment and the French Revolution gained unprecedented levels of social acceptance and equality (which still wasn’t very much), and liberal assimilationism had become the dominant ideology especially among Jewish elites. Assimilationist Jews considered Judaism a religious identity, not an ethnic one, and they rather identified with their nationality. In the latter half of 19th century Jewish socialism was contesting the liberal Jewish idea that antisemitism could be overcome with individualist approach and instead demanded structural change. During the century it became increasingly clear that the assimilationist approach couldn’t fix antisemitism as racial ideology and exclusionist ethnonationalism were gaining traction and fueling antisemitism, which culminated in the 1880s pogroms in Russia and 1894 Dreyfus Affair in France. These events certainly promoted socialist approach among many Jews, but the Jewish elite were certainly not interested in socialist solutions, where they would lose their elite status, even if for white Christians they were all second class citizens. So instead, like many elites facing the threat of socialism, they turned to nationalism. To the question of how to build a nation from a diverse diaspora, they found the answer from Christian Zionism. Jewish Zionism was distinctly secular, so while they did adopt many religious and biblical narratives and goals of Christian Zionism, they put them in nationalist terms. Their end goal was of course different from that of the millennialist Christians so Jewish Zionism was presented as a practical and rational alternative to utopian fanaticism, but they were still natural allies. Zionism was opposed in the European Jewish communities by both assimilationists and socialists, who both viewed it as countering the efforts of opposing antisemitism, which Zionists saw as an inherently impossible endeavor, and also by Orthodox Jews from a religious standpoint. Orthodox Jews denounced the secularization of the Promised Land, which according to them could only be bestowed by God and couldn’t be a state with secular power.

Before Zionism was fully formalized as a movement, there were proto-Zionist movements in Eastern-Europe as a direct response to the pogroms, with the goal of settling Eastern Jewish refugees to Palestine from 1881 forward. This is considered to be the start of the First Aliyah, the explicitly Zionist mass migrations to Palestine. The funding was secured from the European Jews, and with it the Zionists bought land from the absentee urban landlords with large estates and evicted the tenants in order to form Zionist colonies. This raised concern among Ottoman officials, who had become vary of the European exploitation of their capitulation system, which increased European influence with the immigration of European Jews. They were also concerned about the rising Arab nationalism in Palestine provoked by the European economic exploitation and even more pressingly the peasant displacement. The Ottoman Empire was already facing massive difficulties with nationalist movements in different parts of the empire, like in Armenia. They attempted to restrict Zionist land purchases with legal restrictions and failed.

The 1880s settling to Palestine was still unorganized and leaderless until Theodor Herzl, who is considered to be the founder of Zionism, joined Zionist ranks in mid-1890s and began formulating a colonialist venture in earnest. The British were supportive of the Zionist project, but as long as the Ottoman Empire was in charge of Palestine and the British could extend control over it, they weren’t interested in establishing such a state themselves. So the Zionist movement with Herzl in the lead turned to the Ottoman Empire in 1901. He envisioned the Zionist colonial project as a land company, modeled after the British and Dutch East Indian Companies, which would under imperial blessing operate fairly independently and govern over colonized land. The end goal was to build an ethnonationalist Jewish state and expel the native population. There were even dreams of Jewish empire that would colonize neighbouring countries, “civilize” them and bring them “prosperity”. To persuade the Sultan, Herz proposed to pay for the Ottoman Empire’s depts with European Jewish investments in exchange for allowing the Zionists to settle and govern Palestine. The Ottoman government was well aware of Zionist movement’s end goals and their alliances with European Imperialism, rejecting their proposals.

The Zionists evaded Ottoman restrictions anyway and continued to settle Palestine with British backing. European powers then pressured Ottomans to abolish those restrictions allowing a new wave of Zionist colonialism. The violence and pogroms in Russia had convinced some of the Eastern European Jewish socialists that fighting antisemitism was impossible, so they created Labor Zionism and used the “untouched land” to experiment with utopian socialist communes. In the process they displaced indigenous peasant hamulas, which had often for centuries farmed the land in communal ownership. Mass migration and eviction quickly provoked a predictable opposition in the Palestinian population and spread of Arab nationalist thought. This second wave of Aliyah ended at the First World War, which was also the end of the Ottoman Empire.

#history#palestine#palestinian genocide#palestinian history#colonization#colonial history#zionism#islamophobia#ottoman empire

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grecanico

I wasn't very familiar with the dialects of the Griko community, the Greek minority of Italy, residing mostly in Calabria and Apulia. Once in a travel show I had seen a grandpa speaking in one of them but it was so fast and idiomatic that I could only catch one word or two and I consequently thought the Griko dialects had grown really distant from Greece's or Eastern Greek dialects.

Recently I watched this Griko song performance in Italy and it moved me deeply. First of all, it impressed me how it could seamlessly pass as a Modern Greek music style. Of course, Italy and Greece do share a lot of similar sounds, so it perhaps was to be expected. Even the la-la-le-o-la-la pattern, I have heard it in many familiar Greek urban songs (as in, not folk).

I just read that there are in fact two Italiot Greek dialects, Griko (spoken by ~ 45,000 people) and the smaller one, Grecanico (severely endangered and spoken only by ~ 2,000 people). The latter is believed to have incorporated more Italian influences. According to Wikipedia, there are many similarities with Standard Modern Greek, although linguists assert they evolved independently from either Ancient or Koine Greek. If you ask me, judging from the song, there is no way they evolved independently from Ancient Greek. Not only that but if the linguists did not only examine the Ancient and Koine theories, I would have thought they evolved independently from early Modern or super late Koine at most. This could be explained by an influx of Greeks to Italy as a consequence of the Crusader conquests or the Fall of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire to the Ottoman Turks because - fun fact - the type of Greek spoken during both those periods was Modern Greek. Very early Modern Greek at the times of the Fourth Crusade (1202 - 1204), yet modern nonetheless. So the Greeks that might have fled the Latin and the Ottoman blows to the East Roman Empire may have perhaps influenced the language of the ancient and medieval Greek communities of Italy. Then, this late koine - early modern Greek dialect also got influenced by Latin / Italian, especially in the pronunciation and some of the vocabulary. That’s my theory that’s just on me. Perhaps they indeed developed independently from Koine Greek because the Greek language is pretty conservative after all. But Ancient, as in prior to 200 BC, no fricking the frick way.

The song is in Grecanico of Apulia. The video of this performance had the lyrics in Grecanico (they use the Latin alphabet) and a translation in Standard Modern Greek. I was shocked by how much more I could understand in the slower way they were singing compared to the mumbling grandpa. It was deeply touching so I decided to share the video and I even decided to offer the Standard Modern Greek equivalent version in a Latin transliteration, in case any of you is interested in the study of the evolution between Standard Modern Demotic Greek and the Grecanico of Italy.

youtube

Lyrics in Grecanico and Standard Modern Greek (with Latin characters) below the cut:

G: KALINITTA

SMG: KALINICHTA

G: Ti en glicea tusi nifta, ti en ória

SMG: Ti glikiá in' túti i níchta, ti oréa íne

G: cíevó plonno penséonta 'ss' esena

SMG: ki eghó xaplóno skeftómenos eséna

G: C'ettú mpἰ's ti ffenéstra ssu agápi mu

SMG: Ke káto ap'to paráthiro su agápi mu

G: tis kardia mmu su nifto ti ppena

SMG: tis karðiás mu su ðíchno ton póno

G: Evó pánta ss' esena penseo

SMG: Eghó pánta eséna skéftome

G: jati 'sena, fsichi mmu 'gapó

SMG: jatí eséna psichí mu agapó

G: ce pu pao, pu sirno, pu steo

SMG: ke ópu páo, ópu sérno, ópu stéko

G: sti kkardía panta sena vastó.

SMG: stin karðiá pánta eséna vastó.

G: T' asteracia pu panu me vlepune

SMG: T' asterákia pu páno me vlépune

G: ca mo féngo friffizun nomena

SMG: ke me to fengári psithirízun omú (?)

G: ce jelú ce mu leone ¨ston anemo

SMG: ke jelún ke mu léne ¨ston ánemo

G: ta traudia pelis, i chamena"

SMG: ta traghúðia petás, íne chaména¨

G: Kalí nifta! Se finno ce féo

SMG: Kalí níchta! Se afíno ke févgho

G: Plaja 'su ti 'vó pirta prikó

SMG: Plájase jatí eghó févgho (?) pikrá

G: ce pu pao, pu sirno, pu steo

SMG: ke ópu páo, ópu sérno, ópu stéko

G: sti kkardía panta sena vastó.

SMG: stin karðiá pánta eséna vastó.

Hopefully, the Greeks of Italy and the Greek state will aid in rescuing Grecanico from fading forever. 🙏

Oh and here’s an English translation of the song to not leave it entirely obscure:

What a sweet night it is, how beautiful

and I lay down thinking of you

and under your window, my love

I show you the pain of my heart.

I always think about you

because it’s you, my soul, that I love

and wherever I go, I set to, I stand

I always keep you in my heart.

The little stars look at me from above

and they chat together with the moon

and they laugh and tell me “In the wind

you throw your songs, they go wasted”.

Good night! I am leaving you and I am going away.

Go to bed for I am leaving in bitterness

and wherever I go, I set to, I stand

I always keep you in my heart.

#Greek#languages#Greek language#linguistics#Italy#langblr#language stuff#dialects#Griko#grecanico#Greek songs#Greek music#Greco-Italian music#music#Youtube#Greek dialects#Greek culture#Greek facts

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marble Head of Alexander the Great Uncovered in Turkey

The head of a statue determined by archaeologists to belong to Alexander the Great, was unearthed during excavations in north-western Turkey.

The marble head, dated to the 2nd century AD, was found at the top of a theater in the ancient city of Konuralp, near modern-day Düzce.

While most parts of the ancient theater have been unearthed during the excavations, similar historical remains such as the head of the Apollo statue and the head of Medusa were previously found in the upper part of the structure.

During the excavations carried out in the Konuralp Ancient Theater excavation area, archaeologists identified an artifact in the ground at the top of the theater area. As they kept digging, they removed the artifact, which appeared to be the head of a bust.

As a result of the consultation of history experts, it was determined that the bust head found belonged to the Macedonian King Alexander the Great.

In a statement, Konuralp Museum provided information about why they determined the bust to belong to Alexander the Great.

“The head, measuring 23 centimeters [from head to neck] was found during the excavations in the ancient theater. It is depicted with deep and upward-looking eyes made of marble, drill marks on the pupil and a slightly open mouth that does not show much of its teeth.

“His long curly hairstyle up to his neck and two strands of hair [Anastoli] in the middle of his forehead are like the mane of a lion. This depiction is a hair type typical of Alexander the Great,” the statement said.

The marble head of Alexander the Great delivered to Konuralp Museum

Historical Konuralp is 8 km north of Düzce; first settlements there go back to 3rd century BC. Until 74 BC, it was one of the most important cities belonging to Bithynia, which included Bilecik, Bolu, Sakarya, Kocaeli.

It was conquered by Pontus and then by the Roman Empire. During the Roman period, the city was influenced by Latin culture, and it changed its name to Prusias ad Hypium. Later on Christianity affected the city and after the separation of the Roman Empire in 395, it was controlled by the Eastern Roman Empire (the later Byzantine Empire).

In 1204, the Crusader armies invaded Constantinople, establishing the Latin Empire. Düzce and its surroundings are thought to be under the dominance of the Latin Empire during this period. Düzce was under Byzantine rule again from 1261 to 1323.

The Konuralp Museum has some rare exhibits. A 1st-century sarcophagus, Orpheus mosaic, the mosaic of Achilles and Thetis and the 2nd-century copy of Tyche and Plutus sculpture are among the notable items in the museum. There are 456 ethnographic items.

In the ethnography section clothes, weapons, and daily-usage articles about the late Ottoman era are exhibited. There are also 3837 coins from Hellenistic to Ottoman era.

By Tasos Kokkinidis.

#Marble Head of Alexander the Great Uncovered in Turkey#ancient city of Konuralp#Konuralp Ancient Theater excavation area#marble#marble sculpture#ancient marble sculpture#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#greek history#ancient art

285 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Turks in the Balkans: The Battle of Kosovo, 1389.

« Atlas des guerres au Moyen Âge », Loïc Cazaux, Autrement, 2024

by cartesdhistoire

The Turkish advance in the Balkans represents a fundamental step for the stabilization of the Ottoman Sultanate.

In Europe, besides their fragile control of the Bosphorus, the Byzantines only retain a few small, scattered territories threatened by Turkish expansion.

In Pontus, the Greek Empire of Trebizond, founded in 1204, stands as a separate entity alongside Constantinople, despite late medieval agreements between the two Byzantine states. It will collapse in 1461 in the face of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II.

In Albania and the Peloponnese, the Byzantines are no longer able to impose regional order. During the 14th century, the former Greek despotate of Epirus is divided among the Byzantines, Latins (Italians), Albanians, and Serbs. It will also be conquered by the Ottomans in the 15th century.

Finally, thanks to Stephen Dushan, a short-lived Serbian empire was established between the 1340s and 1370s. It came together by exploiting regional dissensions. However, it did not constitute a counterweight to the decline of Byzantine strength and the continuation of Ottoman expansion. The empire collapsed too quickly, failing to consolidate its unity and establish solid foundations. In this sense, it gave way to the western offensive of the Turks toward Serbia, which led to the Battle of Kosovo, or the "Field of Blackbirds" (June 15, 1389), on a plain north of Skopje, delivering the final blow to Serbian resistance.

The Serbs now formed a submissive people who had to fight for the Turks. From their Balkan positions, the Ottomans set up a double objective: to the south, towards the Peloponnese, in order to reach the Byzantine despotate of Morea and strengthen their control of the passages to the Aegean Sea, and to the north, to consolidate their control of the Danube valley, an essential axis toward the Black Sea. For this, Wallachia was attacked, conquered, and put under tribute in 1394-1395.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in case, some might enjoy. Had to organize some notes.

These are just some of the newer texts that had been promoted in the past few years at the online home of the American Association of Geographers. At: [aag dot org/new-books-for-geographers/]

Tried to narrow down selections to focus on Indigenous, Black, anticolonial, Latin American, oceanic/archipelagic geographies; imaginaries and environmental perception; mobility, borders, carceral/abolition geography; literary and musical ecologies.

---

New stuff, early 2024:

A Caribbean Poetics of Spirit (Hannah Regis, University of the West Indies Press, 2024)

Constructing Worlds Otherwise: Societies in Movement and Anticolonial Paths in Latin America (Raúl Zibechi and translator George Ygarza Quispe, AK Press, 2024)

Fluid Geographies: Water, Science, and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Hydrofeminist Thinking With Oceans: Political and Scholarly Possibilities (Tarara Shefer, Vivienne Bozalek, and Nike Romano, Routledge, 2024)

Making the Literary-Geographical World of Sherlock Holmes: The Game Is Afoot (David McLaughlin, University of Chicago Press, 2025)

Mapping Middle-earth: Environmental and Political Narratives in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Cartographies (Anahit Behrooz, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024)

Midlife Geographies: Changing Lifecourses across Generations, Spaces and Time (Aija Lulle, Bristol University Press, 2024)

Society Despite the State: Reimagining Geographies of Order (Anthony Ince and Geronimo Barrera de la Torre, Pluto Press, 2024)

---

New stuff, 2023:

The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Camilla Hawthorne and Jovan Scott Lewis, Duke University Press, 2023)

Activist Feminist Geographies (Edited by Kate Boyer, Latoya Eaves and Jennifer Fluri, Bristol University Press, 2023)

The Silences of Dispossession: Agrarian Change and Indigenous Politics in Argentina (Mercedes Biocca, Pluto Press, 2023)

The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Dueterte (Vicente L. Rafael, Duke University Press, 2022)

Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908 (İlkay Yılmaz, Syracuse University Press, 2023)

The Practice of Collective Escape (Helen Traill, Bristol University Press, 2023)

Maps of Sorrow: Migration and Music in the Construction of Precolonial AfroAsia (Sumangala Damodaran and Ari Sitas, Columbia University Press, 2023)

---

New stuff, late 2022:

B.H. Roberts, Moral Geography, and the Making of a Modern Racist (Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr.and Phillip Gordon Mackintosh, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022)

Environing Empire: Nature, Infrastructure and the Making of German Southwest Africa (Martin Kalb, Berghahn Books, 2022)

Sentient Ecologies: Xenophobic Imaginaries of Landscape (Edited by Alexandra Coțofană and Hikmet Kuran, Berghahn Books 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884–1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Geographies of African American Short Fiction (Kenton Rambsy, University of Mississippi Press, 2022)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski, University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment (Jessica T. Simes, University of California Press, 2021)

---

New stuff, early 2022:

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-fatness as Anti-Blackness (Da’Shaun Harrison, 2021)

Coercive Geographies: Historicizing Mobility, Labor and Confinement (Edited by Johan Heinsen, Martin Bak Jørgensen, and Martin Ottovay Jørgensen, Haymarket Books, 2021)

Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil (Alan Marcus, University of Nebraska Press, 2021)

Decolonial Feminisms, Power and Place (Palgrave, 2021)

Krakow: An Ecobiography (Edited by Adam Izdebski & Rafał Szmytka, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021)

Open Hand, Closed Fist: Practices of Undocumented Organizing in a Hostile State (Kathryn Abrams, University of California Press, 2022)

Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

---

New stuff, 2020 and 2021:

Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography after the Rubber Boom (Amanda Smith, Liverpool University Press, 2021)

Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by María del Pilar Blanco and Joanna Page, 2020)

Reconstructing public housing: Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives (Matt Thompson, University of Liverpool Press, 2020)

The (Un)governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858–1911 (Raghav Kishore, 2020)

Multispecies Households in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russia-Mongolia Border (Edited by Alex Oehler and Anna Varfolomeeva, 2020)

Urban Mountain Beings: History, Indigeneity, and Geographies of Time in Quito, Ecuador (Kathleen S. Fine-Dare, 2019)

City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856 (Marcus P. Nevius, University of Georgia Press, 2020)

#abolition#ecology#multispecies#landscape#tidalectics#indigenous#ecologies#archipelagic thinking#opacity and fugitivity#geographic imaginaries#caribbean#carceral geography#intimacies of four continents

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Disclaimer: the intent of this post is not to delegitimize the right of either Israelis or Palestinians to sovereignty, dignity, and self-determination. There is no future in Israel and Palestine without both Israelis and Palestinians. Nor is this post an endorsement of any Israeli policy.

Rather, after a conversation in the comment section of a recent one of my posts regarding population density in Mandatory Palestine, I decided to rework an older post into this. Personally, I find it really interesting, and I think it’s a key piece in understanding the continuing conflict. It’s also important to dispel false propaganda about the Jewish presence in Israel that has now been accepted as fact.

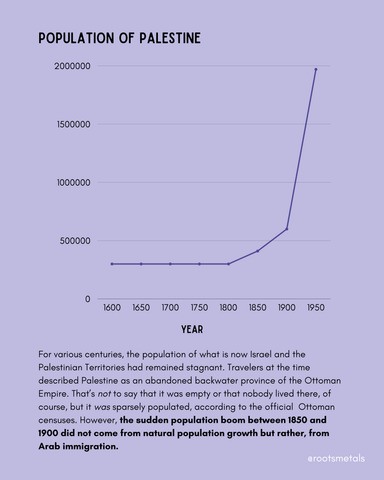

POPULATION OF PALESTINE

For various centuries, the population of what is now Israel and the Palestinian Territories had remained stagnant. Travelers at the time described Palestine as an abandoned backwater province of the Ottoman Empire. That’s not to say that it was empty or that nobody lived there, of course, but it was sparsely populated, according to the official Ottoman censuses. However, the sudden population boom between 1850 and 1900 did not come from natural population growth but rather, from Arab immigration.

"Palestine sits in sackcloth and ashes. Over it broods the spell of a curse that has withered its fields and fettered its energies."

Mark Twain, 1867

"Many are Israel's forsaken places, and great is the desecration. The more sacred the place, the greater the devastation it has suffered. Jerusalem is the most desolate place of all."

Moses ben Nachman (Nachmanides), 1267

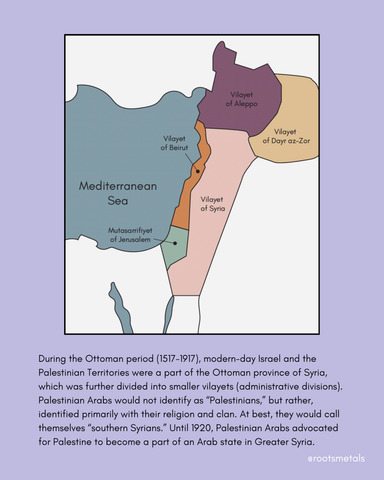

During the Ottoman period (1517-1917), modern-day Israel and the Palestinian Territories were a part of the Ottoman province of Syria, which was further divided into smaller vilayets (administrative divisions). Palestinian Arabs would not identify as “Palestinians,” but rather, identified primarily with their religion and clan. At best, they would call themselves “southern Syrians.” Until 1920, Palestinian Arabs advocated for Palestine to become a part of an Arab state in Greater Syria.

IMMIGRATION FROM EGYPT

The most significant factor in the population growth in Palestine between the turn of the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century was Arab immigration, particularly from Egypt. At the turn of the 19th century, a famine prompted as much as 1/6 of Egypt’s population out of Egypt, with a significant percentage settling in Palestine.

The wave of Egyptian immigration continued in 1829, after thousands of peasants fled harsh labor laws imposed by the Egyptian ruler, Mehmmet Ali Pasha. Travelers during this period wrote that Bedouin tribes accompanied the peasants as well. In 1831, Egypt invaded Palestine. Over 6000 Egyptian peasants crossed into Palestine during the invasion; various Bedouin tribes also arrived with the Egyptian army. Others fled to Palestine as a result of blood feuds between different clans. Many Egyptian soldiers and administrators also chose to stay in Palestine.

By the late 19th century, the city of Jaffa had Egyptian neighborhoods all over town.

When the British invaded Egypt in 1882, scores of Egyptians fled to Palestine. A news report from the time stated: “Many of the people come here from Egypt to wait until the danger passes.” But very few actually returned to Egypt. To this day, the third most common Palestinian surname is El Masry, literally translating to “the Egyptian.”

IMMIGRATION FROM NORTH AFRICA

Following a rebellion against French rule of Algeria in 1850, a number of Arabs and Imazighen from North Africa settled in Palestine, particularly in the Galilee region and Safed.

IMMIGRATION FROM CIRCASSIA

Between 1863-1878, Russia murdered between 1.5-2 million Circassians in the Circassian Genocide. Another 1-1.5 million were expelled from their homes in Circassia. The Ottoman authorities then settled many of the deportees in the Levant, hoping that their presence would curb Bedouin and Druze influence, as the Druze were not always receptive to Ottoman rule, and the Ottomans hoped to squash sentiments of Arab nationalism.

The Circassians, who are Muslim, developed a good relationship with the Yishuv -- the Jewish community in pre-state Israel -- and are now one of the groups with mandatory conscription into the IDF. Like Jews once did, however, Circassians still dream of returning to their homeland, from which they were stolen.

SLAVERY

The Ottoman Empire began issuing decrees to reduce and ultimately terminate slavery in 1830, but these laws were rarely strictly enforced, especially in places such as Palestine. Throughout the 19th century, slave ships continued docking on the shores of Palestine, with the majority of the slaves coming from Ethiopia and Sudan, with a minority coming from Circassia. The last slave ship to arrive to Palestine docked on the shores of Haifa in 1876, though Arabs in Palestine continued holding slaves well into the 1930s.

JEWISH IMMIGRATION (19TH CENTURY)

Between 1881-1903, some 25,000 to 35,000 Jews -- most of them Ashkenazi Jews escaping massacres in Eastern Europe -- immigrated to Ottoman Syria, to the region now encompassing Israel and the Palestinian Territories. Only 15,000 of them stayed, due to harsh economic conditions and disease.

Between 1880-1914, about 8% of all Bukharian Jews immigrated from modern-day Uzbekistan to Jerusalem, escaping brutal persecution. In that same time span, 10% of all Yemenite Jews immigrated to Palestine. Most settled in Jerusalem and Jaffa.

THE "THREAT" OF JEWISH IMMIGRATION

The Ottoman Empire did not abolish the “dhimmi” status for Jews -- that is, second-class citizenship -- until 1856. Dhimmi taxation in Palestine was especially brutal, economically marginalizing religious and ethnic minorities. The Jews in Palestine relied on charity from Jews in the Diaspora for survival. The Samaritans, our closest ethnoreligious cousins, did not have a Diaspora community to come to rely on. Thanks to harsh persecutions, they were nearly wiped out during Ottoman rule.

Though dhimmi status was abolished in 1856, the Arab Muslim majority in Palestine had become accustomed to a certain social order, in which Jews were tolerated so long as we were subjugated. Thus, Zionism and Jewish immigration presented a threat to the status quo.

In 1899, the Arab mayor of Jerusalem, Yousef al-Khalidi, wrote to the chief rabbi of France, “Who can deny the rights of the Jews to Palestine? Good lord, historically it is your country!…But in practice you cannot take over Palestine without the use of force…” The chief rabbi of France forwarded al-Khalidi's letter to Theodor Herzl, who was quick to send a reply, assuring al-Khalidi that the Zionist movement had no intention of displacing the Muslim and Christian populations. It’s worth noting that during this period the mass influx of immigrants -- predominantly Muslim immigrants -- didn’t seem to bother al-Khalidi. It was Jewishimmigration that felt like a threat.

In 1882, the Ottomans prohibited Jews from immigrating to the Ottoman Empire. In 1893, the Ottomans prohibited all Jews -- “Palestinian” or not -- from purchasing land in Palestine. Thus, Jews in the region “enjoyed” less than four decades of equality under the law. No such restrictions existed for Arabs.

IMMIGRATION IN THE 20TH CENTURY

Unlike the population boom in the second half of the 19th century, the huge spike in the population of Palestine in the 20th century did come primarily from Jewish immigration. Between 1904-1914, some 35,000 Jews fled violence, mostly in Eastern Europe, and sought refuge in the region under the Ottomans. Between 1919-1923, another 40,000 Jews arrived to Palestine -- now under the British -- from Europe. Another 70,000 Ashkenazi immigrants arrived in the 1920s, as well as some 10,000 Mizrahi immigrants, predominantly from Yemen and Iraq.

Prior to the Holocaust, another massive influx of Jewish immigrants — between 225,000-300,000 — arrived from Europe. This angered the Arab leadership in Palestine, which responded with violence. To appease the Arabs, the British passed the 1939 White Paper, which limited Jewish immigration to 75,000 people over a period of five years and limited Jewish land purchases to 5% of the Mandate Palestine Territory.

Between 60,000-100,000 Arabs immigrated to Palestine between the two world wars. There are numerous reasons for this migration, most notably, new economic opportunities. In March of 1926, a railroad from Egypt to Palestine was completed, which prompted many young Egyptians to leave by train to seek employment in Palestine. In the 1920s and especially in the 1930s, the coastal plain between Gaza and Jaffa, as well as the area between Gedara and Ness Ziona, Ramle, and Lod became densely populated with Egyptian immigrants.

During World War II, when Jewish immigration was essentially squashed, the British brought Syrian and Lebanese laborers to Palestine. Civilians also employed foreign contractors, many of whom came to Palestine without the legal paperwork. Government records from this period state that there were some 14,000 Egyptian and Lebanese laborers. The population increase along the southern coastal plain during this period was almost completely due to Arab immigration. In the area of Israel now known as “the Triangle,” over 35% of the population consisted of immigrants from Egypt. 10-15% of the Israeli Palestinian population today lives in that region.

LAND OWNERSHIP

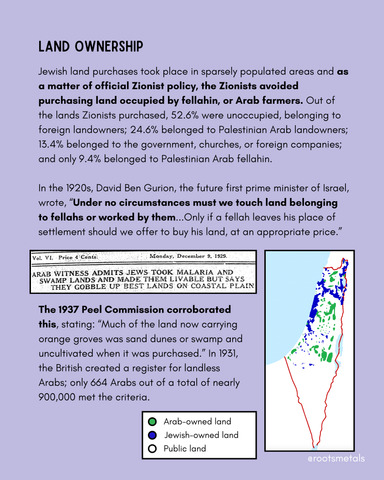

Jewish land purchases took place in sparsely populated areas and as a matter of official Zionist policy, the Zionists avoided purchasing land occupied by fellahin, or Arab farmers. Out of the lands Zionists purchased, 52.6% were unoccupied, belonging to foreign landowners; 24.6% belonged to Palestinian Arab landowners; 13.4% belonged to the government, churches, or foreign companies; and only 9.4% belonged to Palestinian Arab fellahin.

In the 1920s, David Ben Gurion, the future first prime minister of Israel, wrote, “Under no circumstances must we touch land belonging to fellahs or worked by them...Only if a fellah leaves his place of settlement should we offer to buy his land, at an appropriate price.”

The 1937 Peel Commission corroborated this, stating: “Much of the land now carrying orange groves was sand dunes or swamp and uncultivated when it was purchased.” In 1931, the British created a register for landless Arabs; only 664 Arabs out of a total of nearly 900,000 met the criteria.

For a full bibliography of my sources, please head over to my Instagram and Patreon.

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

apologies if you've received an ask about this / have made a post about it before (when i tried to search it up on your blog i first accidentally pasted in the entirety of my speech, but the second time i got it right and the only thing that showed up was the ask you answered about why healthcare is the way it is), but i'm very interested in learning about military medicine, specifically about its role in, as you said in the aforementioned ask, the creation of the hospital/clinic system—do you have any specific readings that would be a good introduction to it?

yes, although i should've phrased that more precisely: the first anon was asking about the current US medical system, and my argument is that a lot of what's characteristically "fascist" (as they put it) about it has throughlines to medical knowledge transfer in the 19th-century Atlantic world, & particularly the influence of what is (sort of incorrectly) termed 'Paris medicine'. so, this is not a universal claim about hospitals (eg, there's lots of scholarship on hospital medicine in the Ottoman Empire, which functioned differently and had different relationships to military medicine, &c &c)

anyway i would recommend for some broad introductions to this process:

Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840, by Rana Hogarth (2017)

The Citizen-Patient in Revolutionary and Imperial Paris, by Dora Wiener (2002)

Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine, by Jim Downs (2021)

and, jumping a bit to the late 19th century and the origins of 'modern medicine' generally:

The Emergence of Tropical Medicine in France, by Michael Osborne (2014)

Imperial Bodies in London: Empire, Mobility, and the Making of British Medicine, 1880–1914, by Kristin Hussey (2021)

Pasteur's Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World, by Aro Velmet (2020)

Curing the Colonizers: Hydrotherapy, Climatology, and French Colonial Spas, by Eric T. Jennings (2006)

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's something truly magical about late 19th century history paintings.

It's the last gasp of the French Academic style, but instead of lots of drapery and allegory, they are taking cues from the rising tide of archaeological research and forward-looking school of narrative illustration, which adds up to the first real attempts to depict the past as best they it could be imagined. These paintings have more in common with the old-(ish) National Geographic illustrations of life in ancient Knossos than they do with their contemporaries in the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

From top to bottom-

"Cardinal Richelieu at the Siege of La Rochelle," by Henri-Paul Motte (1881)- depicts the siege by the forces of Louis XIII of France, lead by Cardinal Richelieu, against the Huguenots in the port of La Rochelle, 1627-1628

"Bringing Home the Body of King Karl XII of Sweden," by Gustaf Cederstrom (1884)- depicts the route of the Swedish army following a failed invasion of Norway that ended with the death of King Karl XII, 1718

"Zenobia's Last Look on Palmyra," by Herbert Schmalz (1888)- depicts the Palmyrene Queen Septimia Zenobia in the moments before leaving her besieged capitol, having been captured by the forces of the Roman emperor Aureliuan, 272 AD

"Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed," by Ilya Repin (1880s)- depicts the supposedly historical story of the Cossacks sending an insulting reply to an ultimatum from the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Mehmed IV, 1676

"The Execution of Lady Jane Grey," by Paul Delaroche (1833)- depicts the execution of the teenaged Lady Jane Grey, who had been elevated to the throne of England and Ireland for (approx) nine days in July of 1553. Her execution was at the Tower of London in February, 1554

"The Cadaver Synod" by Jean-Paul Laurens (1870)- depicts the posthumous trial of Pope Formosus by his eventual successor Pope Stephen VI ten months after Formosus' death, 897

"Chlodobert's Last Moments" by Albert Maignan (1880)- depicts the death of the Merovingian Prince Chlodebert, son of Chilperic I, before the tomb of Saint Medard, where the prince had been brought in the hope of a miracle, 580

546 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dracula a Love Story characters and their historical counterparts

Vlad - Vlad III, also known as Vlad the Impaler and Vlad Dracula (Vlad Țepeș), was a 15th-century ruler of Wallachia, notorious for his brutal punishment methods, particularly impaling his enemies. He defended his realm from the Ottoman Empire and became a national hero in Romania.

Mehmed - Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror (Mehmed bin Murad), was the Ottoman Sultan who famously captured Constantinople in 1453. Historically, Mehmed II clashed with Vlad Dracula during campaigns in Wallachia, adding political depth to their enmity.