#museum of the bible

Text

by Matti Friedman

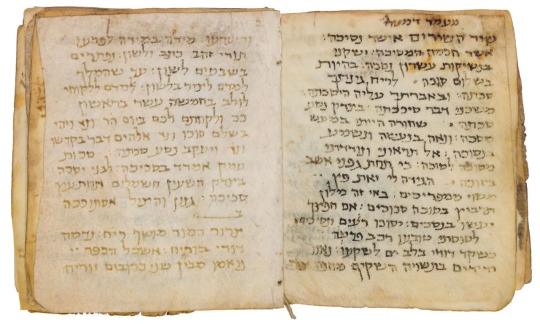

The little book may have been kept by a Jewish family in Bamiyan, the curator suggested, with different people adding new texts as the years passed. The hands of at least five scribes are evident in the pages. They were influenced by ideas and writing coming from both major Jewish centers of the time—Babylon, which is modern-day Iraq, and the Land of Israel, where Jewish sovereignty had been lost seven centuries before and whose people were now under Islamic rule.

The previously unknown poem shows the influence of a familiar biblical text, the erotic Song of Songs, according to Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University, the member of the research team in charge of the poem’s analysis. But it also shows the impact of an esoteric Jewish book that wasn’t part of the Bible, known as the Apocalypse of Zerubbabel. This book is thought to have originated in the early 600s, when a brutal war between Byzantium and the Sasanian empire of Persia generated desperate messianic hopes among many Jews. Whoever wrote the poem in the Afghan prayer book had clearly read the Apocalypse, Elizur said—giving us a glimpse of a Jewish spiritual world both familiar and foreign to the coreligionists of the Bamiyan Jews in our own times, 1,300 years later. The previously unknown poem shows the influence of a familiar biblical text, the erotic Song of Songs, according to Professor Shulamit Elizur of the Hebrew University. (Museum of the Bible)

Chapters of the book’s journey from Afghanistan to Washington are unclear—some because they’re simply unknown even to the experts, and others because that’s the way the people in the murky manuscript market often prefer it.

When the book was discovered by the Hazara militiaman, according to Hepler, the tribesmen didn’t know exactly what it was but understood it was Jewish and assumed it was sacred. The local leader had it wrapped in cloth and preserved in a special box. At one point in the late 1990s, it seems to have been offered unsuccessfully for sale in Dallas, Texas, though it’s unclear if the book itself actually left Afghanistan at the time.

After the al-Qaeda attacks of 9/11 triggered the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the book disappeared for about a decade. In 2012 it resurfaced in London, where it was photographed by the collector and dealer Lenny Wolfe.

Any story about Afghan manuscripts ends up leading to Wolfe, an Israeli born in Glasgow, Scotland. I went to see him at his office in Jerusalem, an Ottoman-era basement where the tables and couches are cluttered with ancient Greek flasks and Hebrew coins minted in the Jewish revolt against Rome in the 130s CE. It was Wolfe who helped facilitate the sale of the larger Afghan collection to Israel’s National Library. “The Afghan documents are fascinating,” he told me, “because they give us a window into Jewish life on the very edge of the Jewish world, on the border with China.”

When Wolfe encountered the little prayer book, he told me it had already been on the London market for several years without finding a buyer. In 2012, the year he photographed the book, he said it was offered to him at a price of $120,000 by two sellers, one Arab and the other Persian. But the Israeli institution he hoped would buy the book turned it down, he told me, so the sale never happened. Not long afterwards, according to his account, he heard that buyers representing the Green family had paid $2.5 million. When I asked what explained the difference in price, he answered, “greed,” and wouldn’t say more. (Hepler of the Museum of the Bible wouldn’t divulge the purchase price or the estimated value of the manuscript, but said Wolfe’s figure was “wrong.”)

The collection amassed by the Green family eventually became the Museum of the Bible, which opened in Washington in 2017. The museum has been sensitive to criticism related to the provenance of its artifacts since a scandal erupted involving thousands of antiquities that turned out to have been looted or improperly acquired in Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East. The museum’s founder, Steve Green, has said he first began collecting as an enthusiast, not an expert, and was taken in by some of the dubious characters who populate the antiquities market. “I trusted the wrong people to guide me, and unwittingly dealt with unscrupulous dealers in those early years,” he said after a federal investigation. In March 2020 the museum agreed to repatriate 11,000 artifacts to Iraq and Egypt.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dead Sea Scrolls, first uncovered by a trio of Bedouin wandering the Judean Desert in 1947, provide a fascinating glimpse into what Scripture looked like during a transformative period of religious ferment in ancient Israel. The scrolls include the oldest copies ever found of the Hebrew Bible, “apocryphal” texts that were never canonized, and rules and guidelines for daily living written by the community of people who lived at Qumran, where the first scrolls were found. All told, scholars have identified as many as 100,000 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments, which come from more than 1,000 original manuscripts.

Experts date the scrolls between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D. (though Langlois believes several may be two centuries older). Some of them are relatively large: One copy of the Book of Isaiah, for example, is 24 feet long and contains a near-complete version of this prophetic text. Most, however, are much smaller—inscribed with a few lines, a few words, a few letters. Taken together, this amounts to hundreds of jigsaw puzzles whose thousands of pieces have been scattered over many different locations around the world.

In 2012, Langlois joined a group of scholars working to decipher close to 40 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments in the private collection of Martin Schøyen, a wealthy Norwegian businessman. Each day in Kristiansand, Norway, he and specialists from Israel, Norway and the Netherlands spent hours trying to determine which known manuscripts the fragments had come from. “It was like a game for me,” Langlois said. The scholars would project an image of a Schøyen fragment on the wall beside a photograph of a known scroll and compare them. “I’d say, ‘No, it’s a different scribe. Look at that lamed,’” Langlois recalled, using the word for the Hebrew letter L. Then they would skip forward to another known manuscript. “No,” Langlois would say. “It’s a different hand.”

Each morning, while out walking, the scholars discussed their work. And each day, according to Esti Eshel, an Israeli epigrapher also on the team, “They were killing another identification.” Returning to France, Langlois examined the fragments with computer-imaging techniques he had developed to isolate and reproduce each letter written on the fragments before beginning a detailed graphical analysis of the writing. And what he discovered was a series of flagrant oddities: A single sentence might contain styles of script from different centuries, or words and letters were squeezed and distorted to fit into the available space, suggesting the parchment was already fragmented when the scribe wrote on it. Langlois concluded that at least some of Schøyen’s fragments were modern forgeries. Reluctant to break the bad news, he waited a year before telling his colleagues. “We became convinced that Michael Langlois was right,” said Torleif Elgvin, the Norwegian scholar leading the effort.

After further study, the team ultimately determined that about half of Schøyen’s fragments were likely forgeries. In 2017, Langlois and the other Schøyen scholars published their initial findings in a journal called Dead Sea Discoveries. A few days later, they presented their conclusions at a meeting in Berlin of the Society of Biblical Literature. Flashing images of the Schøyen fragments on a screen, Langlois described the process by which he concluded the pieces were fakes. He quoted from his contemporaneous notes on the scribe’s “hesitant hand.” He pointed out inconsistencies in the fragments’ script.

And then he dropped the gauntlet: The Schøyen fragments were only the beginning. The previous year, he said, he’d seen photos of several Dead Sea Scrolls fragments in a book published by the Museum of the Bible, in Washington, D.C., a privately funded complex a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol. The museum was scheduled to open its doors in three months, and a centerpiece of its collection was a set of 16 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments whose writing, Langlois now said, looked unmistakably like the writing on the Schøyen fragments. “All of the fragments published there exhibited the same scribal features,” he told the scholars in attendance. “I’m sorry to say that all of the fragments published in this volume are forgeries. This is my opinion.”

The weight of the evidence presented that day by several members of the Schøyen team led to a re-evaluation of Dead Sea Scrolls in private collections all over the world. In 2018, Azusa Pacific University, a Christian college in Southern California that had purchased five scrolls in 2009, conceded that they were likely fakes, and it sued the dealer who had sold them. In 2020, the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, in Fort Worth, Texas, announced that the six Dead Sea Scrolls it had purchased around the same time were also “likely fraudulent.”

The most stunning admission came from executives at the Museum of the Bible: They had hired an art-fraud investigator to examine the museum’s fragments using advanced imaging techniques and chemical and molecular analysis. In 2020, the museum announced that its prized collection of Dead Sea Scrolls was made up entirely of forgeries.

Langlois told me that he derives no pleasure from such discoveries. “My intention wasn’t to be an expert in forgeries, and I don’t love catching bad guys or something,” he told me. “But with forgeries, if you don’t pay attention, and you think they are authentic, then they become part of the data set you use to reconstruct the history of the Bible. The entire theory is then based on data that is false.” That’s why ferreting out biblical fakes is “paramount,” Langlois said. “Otherwise, everything we are going to do on the history of the Bible is corrupt.”

— How an Unorthodox Scholar Uses Technology to Expose Biblical Forgeries

#chanan tigay#michael langlois#how an unorthodox scholar uses technology to expose biblical forgeries#history#religion#christianity#judaism#languages#linguistics#translation#palaeography#museums#forgeries#bible#torah#dead sea scrolls#museum of the bible#west bank#judaean desert#qumran#martin schøyen#esti eshel#book of isaiah

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brannon and his lovely wife at the Museum of the Bible yesterday getting ready to see Prince Caspian by @LogosTheatre!

1 note

·

View note

Text

We Need To Get It Right

The island country of Malta in the Mediterranean Sea has celebrated Christmas for centuries with people crafting what are known as Nativity Cribs, the name common years ago for the feeding box used by livestock, now called mangers.

In 2020 a competition was held, with ten of these beautiful scenes displayed at the Museum of the Bible, and it’s been hosted by this museum for the past several…

View On WordPress

#Bethlehem#Bible#Creches#Dayle Rogers#forgiveness#God#grace#hope#immigrants#Jesus#Malta#malta Nativity Cribs Competition#mercy#Museum of the Bible#Nativity scenes#Tip of My Iceerg#We Need To Get It Right

0 notes

Text

The Green Family’s Other Collection | Sojourners

0 notes

Text

you guys know about the hobby lobby smuggling scandal right

#this is. the funniest crime ever to me#tfw ur a craft store owned by evangelicals so you smuggle in some artifacts you think 'prove' the bible to put in your bible museum (and ge#a tax write off but we neednt mention it)#i think about this every time i pass a hobby lobby XD

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

It was great to see the Bible on display, and I hope people can see the Bible on display in my life every single day!

#encouragement#faith#devotional#religion#christianity#bibledaily#daughters#girl dad#hope#inspiration#jesus christ#family#museum of the Bible

0 notes

Text

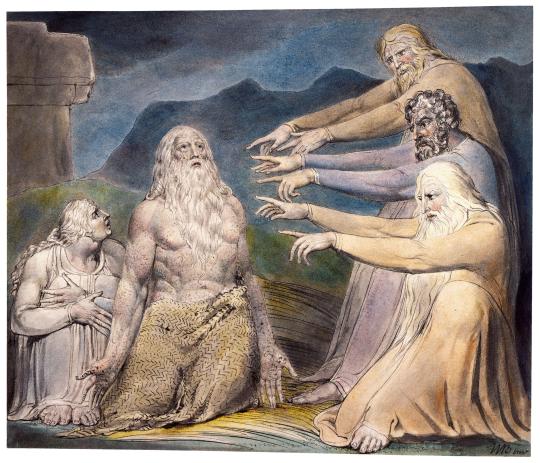

Job Rebuked by His Friends, William Blake, 1805

#art#art history#William Blake#religious art#Biblical art#Christian art#Christianity#Old Testament#Hebrew Bible#Book of Job#wisdom literature#Romanticism#Romantic art#English Romanticism#British art#English art#19th century art#pen and ink#watercolor#Morgan Library and Museum

899 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexandre Cabanel, Samson and Delilah (𝟣𝟪𝟩𝟪)

#alexandre cabanel#oil painting#oil on canvas#19th century#romantic period#painter#art#biblical stories#bible#painting#romanticism#myths and legends#academia#traditional art#classical art#romance#dark academia#betrayal#classic academia#romantic academia#museum#artist#dark romanticism#artists on tumblr#love#lovers#myths#painters on tumblr#artwork

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

#art#painting#oil on canvas#british art#the bible#biblical#bible story#the great flood#book of genesis#old testament#noah´s ark#epic#the deluge#exhibited 1840#francis danby#tate museum

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝚅𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚐𝚎 𝚋𝚘𝚘𝚔𝚜 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚞𝚗𝚒𝚚𝚞𝚎 𝚌𝚕𝚊𝚜𝚙𝚜 (17𝚡𝚡~18𝚡𝚡)

#vintagebooks

#bookstagram #book #books #bookstagrammer #bookclub #booklover #booksbooksbooks #bookworm #booknerd #bookaddict #bookphotography #bookish #booklove #bookcommunity #booklovers #bookobsessed #bookgram #bookporn #buch #bucharest #bücherliebe #bücher #buchliebe #bücherwurm #büchersüchtig #buchverrückt #bucharestmyhome #büchersucht #bücherwelt #librarylovers #librarynerd #libraryart #librarylove #librarybooks #libraryporn #librarylover #libraryofsouls #librarydesign #libraryofbookstagram #librarytime #libraryofinstagram #libraryprogram #librarygram #booksbooksbooks #bookslove #booksaremylife #booksandbooks #booksaddict #bookslover #booksforever #bücherliebe #bücherwurm #büchersucht #büchernerd #bücherverrückt

𝚂𝚘𝚞𝚗𝚍𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚌𝚔: 𝙵𝚊𝚋𝚕𝚎𝚜 & 𝙵𝚊𝚒𝚛𝚢𝚝𝚊𝚕𝚎𝚜 - 𝙳𝚎𝚗𝚒𝚣 𝙺𝚞𝚛𝚝𝚎𝚕 𝚁𝚎𝚖𝚒𝚡 𝚋𝚢 𝙽/𝚊, 𝚁𝚘𝚜𝚒𝚗𝚊

#l o v e#books#clasps#vintage books#vintage#5/2024#nostalgia#book#library#antique#history#17th century#18th century#art history#reading is sexy#reading#antique books#aesthetic#fables#fairycore#bibles#religion is a mental illness#x-heesy#now playing#music and art#contemporaryart#museum aesthetic#museum archives#museum art

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Baptism of Christ, c.1710 by Aernt de Gelder

#aernt de gelder#baptism#baptist#christ#holy spirit#holy#dove#river#river jordan#museum#art gallery#christian#christian art#faith#chruch#bible#holy bible#religion#religious art#religious imagery#jesus christ#art#artwork#old art#classic art

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stealing from Christianity is a lot like stealing from a British museum. 1% chance of getting something original, 99% of getting previously stolen goods.

#anti capitalist#leftist#anarchy#fuck the man#stealing#theft#art theft#british museum#british royal family#british royalty#christianity#bible#indiana jones

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lolita fashion brand "Angelic Pretty" has enthusiastic fans all over the world. The exhibition "Angelic Pretty MUSEUM", which unravels the history of the select shop "PRETTY" until today, was held from October 26th (Friday) to 27th (Saturday), 2018 at LAFORET MUSEUM HARAJUKU.

In the first act, the gorgeous dresses that were unveiled at the dinner party held at the end of every year appeared one after another.

At the end of the collection, Risa Nakamura appeared in a special dress made for this exhibition. I walked on the runway while Black Sumire's "Happy Princess" was played.

model♡Risa Nakamura

#egl#egl fashion#egl community#eglfashion#eglcommunity#glb#gothic and lolita bible#gothic & lolita bible#kera#kera magazine#not my coord#laforet museum#angelic pretty museum#risa nakamura#angelic pretty#fashion show

189 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sumerian Cuneiform tablet from the ancient city of Ur, dating back to 2100-2000 BCE. Museum of the Bible, Washington, DC.

Photo by Babylon Chronicle

149 notes

·

View notes