#lesswrong has a lot to answer for

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

this is real. the theory is called "roko's basilisk" if you want to google it and be astonished at how stupid it is

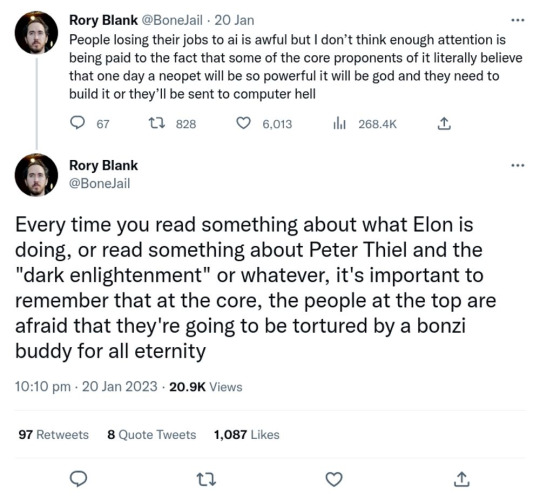

Rory Blank @BoneJail

People losing their jobs to ai is awful but I don’t think enough attention is being paid to the fact that some of the core proponents of it literally believe that one day a neopet will be so powerful it will be god and they need to build it or they’ll be sent to computer hell

Rory Blank @BoneJail

Every time you read something about what Elon is doing, or read something about Peter Thiel and the "dark enlightenment" or whatever, it's important to remember that at the core, the people at the top are afraid that they're going to be tortured by a bonzi buddy for all eternity

#sigh#lesswrong has a lot to answer for#morbidly obtuse#philosophy#they actually managed to make pascal's wager worse!#dove.txt

631 notes

·

View notes

Text

gpt-4 prediction: it won't be very useful

Word on the street says that OpenAI will be releasing "GPT-4" sometime in early 2023.

There's a lot of hype about it already, though we know very little about it for certain.

----------

People who like to discuss large language models tend to be futurist/forecaster types, and everyone is casting their bets now about what GPT-4 will be like. See e.g. here.

It would accord me higher status in this crowd if I were to make a bunch of highly specific, numerical predictions about GPT-4's capabilities.

I'm not going to do that, because I don't think anyone (including me) really can do this in a way that's more than trivially informed. At best I consider this activity a form of gambling, and at worst it will actively mislead people once the truth is known, blessing the people who "guessed lucky" with an undue aura of deep insight. (And if enough people guess, someone will "guess lucky.")

Why?

There has been a lot of research since GPT-3 on the emergence of capabilities with scale in LLMs, most notably BIG-Bench. Besides the trends that were already obvious with GPT-3 -- on any given task, increased scale is usually helpful and almost never harmful (cf. the Inverse Scaling Prize and my Section 5 here) -- there are not many reliable trends that one could leverage for forecasting.

Within the bounds of "scale almost never hurts," anything goes:

Some tasks improve smoothly, some are flatlined at zero then "turn on" discontinuously, some are flatlined at some nonzero performance level across all tested scales, etc. (BIG-Bench Fig. 7)

Whether a model "has" or "doesn't have" a capability is very sensitive to which specific task we use to probe that capability. (BIG-Bench Sections 3.4.3, 3.4.4)

Whether a model "can" or "can't do" a single well-defined task is highly sensitive to irrelevant details of phrasing, even for large models. (BIG-Bench Section 3.5)

It gets worse.

Most of the research on GPT capabilities (including BIG-Bench) uses the zero/one/few-shot classification paradigm, which is a very narrow lens that arguably misses the real potential of LLMs.

And, even if you fix some operational definition of whether a GPT "has" a given capability, the order in which the capabilities emerge is unpredictable, with little apparent relation to the subjective difficulty of the task. It took more scale for GPT-3 to learn relatively simple arithmetic than it did for it to become a highly skilled translator across numerous language pairs!

GPT-3 can do numerous impressive things already . . . but it can't understand Morse Code. The linked post was written before the release of text-davinci-003 or ChatGPT, but neither of those can do Morse Code either -- I checked.

On that LessWrong post asking "What's the Least Impressive Thing GPT-4 Won't be Able to Do?", I was initially tempted to answer "Morse Code." This seemed like as safe a guess as any, since no previous GPT was able to it, and it's certainly very unimpressive.

But then I stopped myself. What reason do I actually have to register this so-called prediction, and what is at stake in it, anyway?

I expect Morse Code to be cracked by GPTs at some scale. What basis to I have to expect this scale is greater than GPT-4's scale (whatever that is)? Like everything, it'll happen when it happens.

If I register this Morse Code prediction, and it turns out I am right, what does that imply about me, or about GPT-4? (Nothing.) If I register the prediction, and it turns out I am wrong, what does this imply . . . (Nothing.)

The whole exercise is frivolous, at best.

----------

So, here is my real GPT-4 prediction: it won't be very useful, and won't see much practical use.

Specifically, the volume and nature of its use will be similar to what we see with existing OpenAI products. There are companies using GPT-3 right now, but there aren't that many of them, and they mostly seem to be:

Established companies applying GPT in narrow, "non-revolutionary" use cases that play to its strengths, like automating certain SEO/copywriting tasks or synthetic training data generation for smaller text classifiers

Startups with GPT-3-centric products, also mostly "non-revolutionary" in nature, mostly in SEO/copywriting, with some in coding assistance

GPT-4 will get used to do serious work, just like GPT-3. But I am predicting that it will be used for serious work of roughly the same kind, in roughly the same amounts.

I don't want to operationalize this idea too much, and I'm fine if there's no fully unambiguous way to decide after the fact whether I was right or not. You know basically what I mean (I hope), and it should be easy to tell whether we are basically in a world where

Businesses are purchasing the GPT-4 enterprise product and getting fundamentally new things in exchange, like "the API writes good, publishable novels," or "the API performs all the tasks we expect of a typical junior SDE" (I am sure you can invent additional examples of this kind), and multiple industries are being transformed as a result

Businesses are purchasing the GPT-4 enterprise product to do the same kinds of things they are doing today with existing OpenAI enterprise products

However, I'll add a few terms that seem necessary for the prediction to be non-vacuous:

I expect this to be true for at least 1 year after the release of the commercial product. (I have no particular attachment to this timeframe, I just need a timeframe.)

My prediction will be false in spirit if the only limit on transformative applications of GPT-4 is monetary cost. GPT-3 is very pricey now, and that's a big limiting factor on its use. But even if its cost were far, far less, there would be other limiting factors -- primarily, that no one really knows how to apply its capabilities in the real world. (See below.)

(The monetary cost thing is why I can't operationalize this beyond "you know what I mean." It involves not just what actually happens, but what would presumably happen at a lower price point. I expect the latter to be a topic of dispute in itself.)

----------

Why do I think this?

First: while OpenAI is awe-inspiring as a pure research lab, they're much less skilled at applied research and product design. (I don't think this is controversial?)

When OpenAI releases a product, it is usually just one of their research artifacts with an API slapped on top of it.

Their papers and blog posts brim with a scientist's post-discovery enthusiasm -- the (understandable) sense that their new thing is so wonderfully amazing, so deeply veined with untapped potential, indeed so temptingly close to "human-level" in so many ways, that -- well -- it surely has to be useful for something! For numerous things!

For what, exactly? And how do I use it? That's your job to figure out, as the user.

But OpenAI's research artifacts are not easy to use. And they're not only hard for novices.

This is the second reason -- intertwined with the first, but more fundamental.

No one knows how to use the things OpenAI is making. They are new kinds of machines, and people are still making basic philosophical category mistakes about them, years after they first appeared. It has taken the mainstream research community multiple years to acquire the most basic intuitions about skilled LLM operation (e.g. "chain of thought") which were already known, long before, to the brilliant internet eccentrics who are GPT's most serious-minded user base.

Even if these things have immense economic potential, we don't know how to exploit it yet. It will take hard work to get there, and you can't expect used car companies and SEO SaaS purveyors to do that hard work themselves, just to figure out how to use your product. If they can't use it, they won't buy it.

It is as though OpenAI had discovered nuclear fission, and then went to sell it as a product, as follows: there is an API. The API has thousands of mysterious knobs (analogous to the opacity and complexity of prompt programming etc). Any given setting of the knobs specifies a complete design for a fission reactor. When you press a button, OpenAI constructs the specified reactor for you (at great expense, billed to you), and turns it on (you incur the operating expenses). You may, at your own risk, connect the reactor to anything else you own, in any manner of your choosing.

(The reactors come with built-in safety measures, but they're imperfect and one-size-fits-all and opaque. Sometimes your experimentation starts to get promising, and then a little pop-up appears saying "Whoops! Looks like your reactor has entered an unsafe state!", at which point it immediately shuts off.)

It is possible, of course, to reap immense economic value from nuclear fission. But if nuclear fission were "released" in this way, how would anyone ever figure out how to capitalize on it?

We, as a society, don't know how to use large language models. We don't know what they're good for. We have lots of (mostly inadequate) ways of "measuring" their "capabilities," and we have lots of (poorly understood, unreliable) ways of getting them to do things. But we don't know where they fit in to things.

Are they for writing text? For conversation? For doing classification (in the ML sense)? And if we want one of these behaviors, how do we communicate that to the LLM? What do we do with the output? Do they work well in conjunction with some other kind of system? Which kind, and to what end?

In answer to these questions, we have numerous mutually exclusive ideas, which all come with deep implementation challenges.

To anyone who's taken a good look at LLMs, they seem "obviously" good for something, indeed good for numerous things. But they are provably, reliably, repeatably good for very few things -- not so much (or not only) because of their limitations, but because we don't know how to use them yet.

This, not scale, is the current limiting factor on putting LLMs to use. If we understood how to leverage GPT-3 optimally, it would be more useful (right now) than GPT-4 will be (in reality, next year).

----------

Finally, the current trend in LLM techniques is not very promising.

Everyone -- at least, OpenAI and Google -- is investing in RLHF. The latest GPTs, including ChatGPT, are (roughly) the last iteration of GPT with some RLHF on top. And whatever RLHF might be good for, it is not a solution for our fundamental ignorance of how to use LLMs.

Earlier, I said that OpenAI was punting the problem of "figure out how to use this thing" to the users. RLHF effectively punts it, instead, to the language model itself. (Sort of.)

RLHF, in its currently popular form, looks like:

Some humans vaguely imagine (but do not precisely nail down the parameters of) a hypothetical GPT-based application, a kind of super-intelligent Siri.

The humans take numerous outputs from GPT, and grade them on how much they feel like what would happen in the "super-intelligent Siri" fantasy app.

The GPT model is updated to make the outputs with high scores more likely, and the ones with low scores less likely.

The result is a GPT model which often talks a lot like the hypothetical super-intelligent Siri.

This looks like an easier-to-use UI on top of GPT, but it isn't. There is still no well-defined user interface.

Or rather, the nature of the user interface is being continually invented by the language model, anew in every interaction, as it asks itself "how would (the vaguely imagined) super-intelligent Siri respond in this case?"

If a user wonders "what kinds of things is it not allowed to do?", there is no fixed answer. All there is is the LM, asking itself anew in each interaction what the restrictions on a hypothetical fantasy character might be.

It is role-playing a world where the user's question has an answer. But in the real world, the user's question does not have an answer.

If you ask ChatGPT how to use it, it will roleplay a character called "Assistant" from a counterfactual world where "how do I use Assistant?" has a single, well-defined answer. Because it is role-playing -- improvising -- it will not always give you the same answer. And none of the answers are true, about the real world. They're about the fantasy world, where the fantasy app called "Assistant" really exists.

This facade does make GPT's capabilities more accessible, at first blush, for novice users. It's great as a driver of adoption, if that's what you want.

But if Joe from Midsized Normal Mundane Corporation wants to use GPT for some Normal Mundane purpose, and can't on his first try, this role-play trickery only further confuses the issue.

At least in the "design your own fission reactor" interface, it was clear how formidable the challenge was! RLHF does not remove the challenge. It only obscures it, makes it initially invisible, makes it (even) harder to reason about.

And this, judging from ChatGPT (and Sparrow), is apparently what the makers of LLMs think LLM user interfaces should look like. This is probably what GPT-4's interface will be.

And Joe from Midsized Normal Mundane Corporation is going to try it, and realize it "doesn't work" in any familiar sense of the phrase, and -- like a reasonable Midsized Normal Mundane Corporation employee -- use something else instead.

ETA: I forgot to note that OpenAI expects dramatic revenue growth in 2023 and especially in 2024. Ignoring a few edge case possibilities, either their revenue projection will come true or the prediction in this post will, but not both. We'll find out!

257 notes

·

View notes

Note

is the less wrong harry potter fic thign a cult?? i really liked that fic like 10 years ago (though its boring but also interesting it just seemed like a weird little thingy that existed for nor reason) and then i met my abusive ex through us both liking the fic and it ended a couple years later but i never finished it but he spent like a MONTH doing some weird 'i must send the author the puzzle answer or harry dies' obsessive THING and idk i just never heard about it again after that. cult??

Yeah so, I'm not terribly educated on this one, but this reddit comment [link] is a pretty good write up/summary. Basically the author is the founder/leader of both LessWrong (a spin off of rationalist philosophy that has a lot of cult of personality elements to it) & MIRI, which stands for Machine Intelligence Research Institution, which is a group that believes that the invention of a world ruling AI is inevitable, so we (MIRI) need to make sure that it's a good AI, and to do that we need donations from our followers. Lots of donations. To help us save the world, yasee.

It's very Scientology 2. Grimes is involved.

#and honestly. like im only skimming here but a lot of this lesswrong shit seems very dianetics to me.#time is a flat circle.#ask#but yeah um. harry potter and the methods of rationality was made to push cult ideas#and solicit donations for a cult. by a cult leader.#surprise!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inadequate Definientia

I'd like to attempt to clear-up the bundle of "anti-inductive", "inadequate equilibria", and the implied "adequate equilibria" all at once. I think they're all part of the same confusing knot, for which specific kinds of teleological blindnesses are to blame.

"Inadequate Equilibria" is a termed coined by Eliezer Yudkowsky in the book of the same name. It describes situations in which a certain part of a system has reached an "equilibrium"—used casually to specify a stationary state that is difficult to escape from under certain assumptions, similar to a stable equilibrium—that EY feels are "inadequate". I think the definition of inadequate here is very vague, and digging hard to pretend that it's coherent seems a bit silly. However, what I think EY is pointing at is that the games certain people claim to be playing, e.g. the Bank of Japan claiming to try to be regulating Japan's economy for maximum profit and health, are often not the games they're actually playing. This is an extremely broad set of phenomena, but EY restricts himself to games where the players are kinda sort playing the game you think they're playing but with some caveats/extra rules/unexpected incentives.

I enjoyed the book and I think it's a decent intro to spotting "the games people are actually playing and when you should trust their claims", but the main issue is that EY doesn't seem to have any criteria for what makes the equilibria inadequate vs. the people telling you the rules just straight-up lying. Clearly both happen.

To make this worse, EY conflates the fact that certain games don't have the incentives you would want them to have (if you really wanted them to complete their stated goal) with the fact that certain games don't have the right conditions to make solution finding highly efficient, e.g. because one party has a monopoly.

Let's clear this up.

The latter case, when a game is currently blocked by something within the game that could be changed without breaking the rules or changing the game is the definition of market inefficiency. Let's just call it "inefficiency" because people get fussy about what counts as a market.

The former case, where you could redistribute or inject resources into the game, but the game isn't setup to incentivize what you—the protagonist of Reality—want from it is the definition of surrogation, i.e. "you're optimizing one thing and dreaming that it correlates with another".

Easy peasy.

If you think "surrogation" is often subjective, because not everyone will agree on what a game is "for" you're right! But if you think "efficiency" is objective, you're wrong: real systems are way more complex than most toy examples of efficient markets and we never really know "how good this game is at finding solutions" in comparison to the best possible game. Thus, "adequate equilibria" are judgement calls.

Sidenote: Despite my immense respect for LessWrong and the Rationalist community more broadly for incentivizing open, critical discourse and the construction of new and useful vocabulary, a lot of this vocabulary ends-up secretly being about "what I think system X should be/claims to be/is about vs. what it really is". There's often lots of interrogation of "what it really is" but relatively little of "maybe it's complicated how to define what something is for and most names/descriptions are just short-hand or for convenience?" I call this "the teleological lens". Everybody tends to fall into it, because communication is naturally about what you want from people, but literalists tend to think themselves immune because they define things so clearly. Most rationalists have at least a literalist streak, because it is what starting from first principles demands. Literalists are always in danger of taking other people's words too much at face value and completely missing the point, a complementary error to most people's inability to see literal meaning.

Finally, we reach "anti-inductive" which, in the article people tend to point to, seems to be something along the lines of "games where common knowledge is priced in". While this is a perfectly reasonable definition to inspire discussion, I think it's difficult to assess for many reasons, two of which are: (i) how do we agree what's common knowledge at time T? (ii) how the hell do we know it's priced in?

I propose the following definition for anti-inductive play:

anti-inductive (adj) — describing a property of certain kinds of game play where moves, on average, (i) leak information about your strategy and (ii) knowing such leaked information allows for the creation of counter-strategies.

In other words, anti-inductive plays are "scoopable", not just because effective counter-strategies exist (ii) but because their construction is a function of observing other strategies at play (i). Without both stipulations, pure randomness might be the winning strategy, in order to ensure eventually hitting on an effective counter-strategy.

Usually equilibria are sustained by anti-inductive play, in which different parties are constantly developing counter strategies and counter counter strategies, keeping the system locked onto some other fundamental factor, e.g. the actual overhead of a service during a price war. Adequate equilibria are ones where the byproduct of the game matches the in-game score well enough and is optimized quickly enough that the person saying "adequate" is happy with it. This is usually a result of anti-inductive play (e.g. web browser features that are useful spreading to all browsers) but not always (e.g. playing the cooperative game Hanabi when everyone is invested in doing well). Inadequate equilibria simply describe situations in which the system is "stuck" from the point of view of the speaker.

This might seem like "ruining the magic" of the term: "What do you mean it's all just about whether people like stuff?" I remember being struck by the "aha!" feeling of EY's description of inefficient and misaligned systems, and I don't think this at all changes his guide to spotting inefficiencies and misalignments from one's own point of view. It does require use to ask "inadequate to what?" and to answer with how you imagine the current system could be (i) more efficient (ii) better aligned. This seems like a low-bar, and it's one EY certainly passes, but which a lot of people referencing the concept eschew. Real systems are complex and we can almost only make relative judgements, efficiency and alignment give us axes to make these relative judgements comparable to each other. Anti-inductivity gives a sketch of the most common mechanism used for keeping efficiency and alignment stable.

The video game industry is at an equilibria where it is inadequate to create as many story rich games as I would like, since investing more in narrative design doesn't yield linear (or even predictable) returns. Anti-inductive play forces us to ask: why hasn't someone scooped up the free energy from my willingness to buy such games?

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

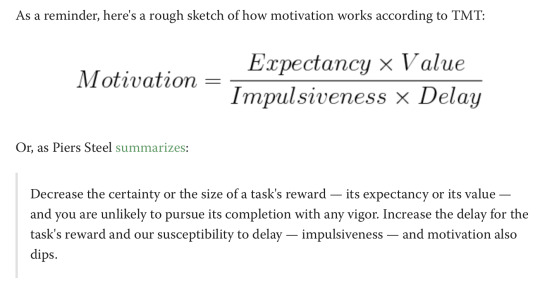

LessWrong: My Algorithm for Beating Procrastination

Step 1: Notice I'm procrastinating.

This part's easy. I know I should do the task, but I feel averse to doing it, or I just don't feel motivated enough to care. So I put it off, even though my prefrontal cortex keeps telling me I'll be better off if I do it now. When this happens, I proceed to step 2.

Step 2: Guess which unattacked part of the equation is causing me the most trouble.

Now I get to play detective. Which part of the equation is causing me trouble, here? Does the task have low value because it's boring or painful or too difficult, or because the reward isn't that great? Do I doubt that completing the task will pay off? Would I have to wait a long time for my reward if I succeeded? Am I particularly impatient or impulsive, either now or in general? Which part of this problem do I need to attack?

Actually, I lied. I like to play army sniper. I stare down my telescopic sight at the terms in the equation and interrogate them. "Is it you, Delay? Huh, motherfucker? Is it you? I've shot you before; don't think I won't do it again!"

But not everyone was raised on violent videogames. You may prefer a different role-play.

Anyway, I try to figure out where the main problem is. Here are some of the signs I look for:

When I imagine myself doing the task, do I see myself bored and distracted instead of engaged and interested?

Is the task uncomfortable, onerous, or painful? Am I nervous about the task, or afraid of what might happen if I undertake it?

Has the task's payoff lost its value to me? Perhaps it never had much value to me in the first place?

If my answer to any of these questions is "Yes," I'm probably facing the motivation problem of low value.

Do I think I'm likely to succeed at the task? Do I think it's within my capabilities? Do I think I'll actually get the reward if I do succeed? If my answer to any of these questions is "No," I'm probably facing the problem of low expectancy.

How much of the reward only comes after a significant delay, and how long is that delay? If most of the reward comes after a big delay, I'm probably the facing the problem of, you guessed it, delay.

Do I feel particularly impatient? Am I easily distracted by other tasks, even ones for which I also face problems of low value, low expectancy, or delay? If so, I'm probably facing the problem of impulsiveness.

If the task is low value and low expectancy, and the reward is delayed, I run my expected value calculation again. Am I sure I should do the task, after all? Maybe I should drop it or delegate it. If after re-evaluation I still think I should do the task, then I move to step 3.

Step 3: Try several methods for attacking that specific problem.

Once I've got a plausible suspect in my sights, I fire away with the most suitable ammo I've got for that problem. Here's a quick review of some techniques described in How to Beat Procrastination:

For attacking the problem of low value: Get into a state of flow, perhaps by gamifying the task. Ensure the task has meaning by connecting it to what you value intrinsically. Get more energy. Use reward and punishment. Focus on what you love, wherever possible.

For attacking the problem of low expectancy: Give yourself a series of small, challenging but achieveable goals so that you get yourself into a "success spiral" and expect to succeed. Consume inspirational material. Surround yourself with others who are succeeding. Mentally contrast where you are now and where you want to be.

For attacking the problem of delay: Decrease the reward's delay if possible. Break the task into smaller chunks so you can get rewards each step of the way.

For attacking the problem of impulsiveness: Use precommitment. Set specific and meaningful goals and subgoal and sub-subgoals. Measure your behavior. Build useful habits.

Each of these skills must be learned and practiced first before you can use them. It took me only a few days to learn the mental habit of "mental contrasting," but I spent weekspracticing the skill of getting myself into success spirals. I've spent months trying various methods for having more energy, but I can do a lot better than I'm doing now. I'm not very good at goal-setting yet.

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the thing you mentioned about the ratblr (delightful term, by the way) style of communication and how it seems to rub people outside ratblr the wrong way?

I’ve been meaning to answer this but never had quite the right mix of time and motivation! This will probably be a bit long. Also, disclaimer: I’m only sort of on the edges of ratblr, and I haven’t been here all that long, so I may get things wrong.

So first off: what is ratblr (short for rationalist tumblr, by the way)? It’s far from clearly defined, but most people I consider ratblr members share some combination of the following qualities: a background in STEM, specifically software engineering, autism or ADHD (or both), some connection to academia, social-democratic (or libertarian) political views, and a skepticism of mainstream tumblr discourse. Many have also read the sequences, a group of interconnected essays on rationalism from LessWrong, an ancestor of sorts to tumblr’s rationalist community that was very AI-focused. That said, many ratblr people prefer to call themselves rationalist-adjacent and don’t want to be too closely associated with that past, in part because LessWrong people were so insufferable... it’s a whole thing.

Also, in terms of blog composition, ratblrs usually have very few comment-free reblogs, lots of original posts and reblog-replies, many longer posts with academic or pseudo-academic language, and are often mutuals with other ratblrs (especially argumate).

So how does this lead to conflict with the rest of tumblr? First off, there’s a specific dialect that ratblr tends to use, drawing from academia and STEM, that bothers a lot of people. I think it’s because many people associate this style of writing with being talked down to, when I think that is almost never the intention from ratblr people. There’s also an often-justifiable distrust many people have for academics and STEM people which can bleed into this type of interaction.

Second, it’s a pretty major culture shift from the rest of tumblr to ratblr. There’s a lot of meta jokes made on here about how confrontational a lot of this website is, and that’s not exactly the case for most of ratblr. I’ve been blocked on here a lot for reblogging something with a dissenting opinion, but I’ve had heated discussions with ratblr people and stayed mutuals with them at the end of the day. Disagreement is much more a natural part of the culture, and arguing about politics is treated as part of the fun rather than a personal attack.This has its downsides, of course, as it allows some absolutely insufferable people to persist in the community, so I don’t want this to come off like “ratblr rules the rest of tumblr sucks.”

Continuing along the culture shift line of thinking, there’s an emphasis among ratblr blogs around being exacting in your language and nuanced in your thinking. I’m reminded of a post I made around a month ago where someone reblogged with a disagreement on my use of a term. I initially interpreted this as an attack on the overall content of the post and got a bit defensive, but it turned out they were just correcting me on how to properly use the term. On a lot of tumblr, a nitpick is a sign you disagree with the post and don’t see a better way to attack it. On ratblr, people just like to nitpick. This has its drawbacks, but it’s pretty harmless once you get used to it.

Putting all this together, you can imagine how ratblr blogs might come into conflict with other tumblr communities. There’s a dynamic that happens often when leftblr, a very dogmatic community that enjoys making sweeping generalizations and often interprets small disagreements as personal attacks, with ratblr, a community that hates dogma, nitpicks, and actively enjoys small disagreements, come into contact.

The meat of what I was talking about with communication style is mainly what I said in my fourth paragraph, but I think the rest is fun cultural context, so I wrote a lot more than was probably necessary. Thanks for asking!

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why I Do Things

I'm starting this off with a disclaimer, no one totally understands why they act the way they do. Therapists help us talk through our reasoning process and cognitive behavioral therapy is based on the idea that examining your own thoughts is both possible and nontrivial. I think people often fail to realize just how wide the gap is between why we think we do things, and why we actually do things. For a great example see this lesswrong post. One of the experiments summarized there was with a split-brain patient. Here's the relevant section:

This divorce between the apologist and the revolutionary might also explain some of the odd behavior of split-brain patients. Consider the following experiment: a split-brain patient was shown two images, one in each visual field. The left hemisphere received the image of a chicken claw, and the right hemisphere received the image of a snowed-in house. The patient was asked verbally to describe what he saw, activating the left (more verbal) hemisphere. The patient said he saw a chicken claw, as expected. Then the patient was asked to point with his left hand (controlled by the right hemisphere) to a picture related to the scene. Among the pictures available were a shovel and a chicken. He pointed to the shovel. So far, no crazier than what we've come to expect from neuroscience.

Now the doctor verbally asked the patient to describe why he just pointed to the shovel. The patient verbally (left hemisphere!) answered that he saw a chicken claw, and of course shovels are necessary to clean out chicken sheds, so he pointed to the shovel to indicate chickens. The apologist in the left-brain is helpless to do anything besides explain why the data fits its own theory, and its own theory is that whatever happened had something to do with chickens, dammit!

I found the book that the author sourced for that experiment and it looks awesome. I'm going to buy it on alibris and I might post about it when I get to read it. The point is, the patient believed that the reason they pointed to the shovel was that it could be used to clean out chicken coops but the actual reason was to shovel snow. This is my best guess for why I do the things I do and I can't guarantee it's correct.

My Brain

I usually think of my brain as being comprised of several, semi-autonomous sub-units. Each has it's own goals, personality and reasoning abilities. There's one special sub-unit which I think is the part that is responsible for abstract reasoning and also, I suspect, language. This is the part that carries out conscious decision making. The other parts are responsible for taking context appropriate actions. These are the parts that sometimes do very annoying things like playing Freecell or browsing Youtube when I'm supposed to be working. Those parts make decisions based primarily on habit. In contrast my conscious brain has a formal process for making decisions.

Conscious Decision Making

I'm a utilitarian. Heuristically, this means that my goal is to take actions that get me as much utility as possible. Utility is a measure of how much I like the state of the world. Equivalently it is how beautiful I find a world to be. To be more precise, it is a function that ascribes to every possible world a number. The higher the number, the more I like that outcome. My goal is to maximize the expected value of this function.

A short aside: I do sometimes keep promises even when I think doing so will result in less utility than breaking them. I only do this in special circumstances where commiting to a promise gives me an advantage in expectation. This is a fairly subtle point and doesn't come up all that often, but it does explain why I'm a bit more honest than you'd expect.

The professor that taught an ethics class I took once thought that utilitarians only care about maximizing total happiness. This is absolutely not the case. A world in which everyone is permanently doped up on soma has very high total happiness, but very low actual utility. The exact definition of utility is whatever my brain says it is, but I've built a approximate version from this which is what I'll discuss here.

All other things being equal, I ascribe higher utility to worlds in which any individual person experiences more happiness and less pain over the course of their life. It similarly increases with the degree to which that person can control their own life. It also increases when I have a better understanding of the world and decreases sharply when I believe things that are false. Some bits of knowledge have more value than others with some facts being worthless and others worth a lot of blood, sweat and tears. It increases when people make things like bridges, spaceships and art. The actual function is a non-linear combination of all these factors.

Focusing just on the component that looks at individual lives, I tend to value the happiness of any two people roughly equally. One exception is that I do tend to value my own happiness somewhat less than that of a stranger's. The total value of a life is approximatly their combined happiness and autonomy integrated over the course of their life. For the purposes of this calculation you can think of pain as negative happiness. For most people alive today I consider their utility at any particular moment to almost always be positive. Thus, all other things being equal, the longer someone lives the better.

The reason I help some people so much is because I think that I can significantly improve the utility contributed by their lives by doing so. Obviously there are many potential strategies for maximizing total utility but I think it is often better to focus on helping a few individuals a lot, than many people a little.

In summary I care about you, the reader, being happy, in control of your own life, and alive very much. Let me know if there's anything I can do to improve those things.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a rant based on things i observed, where I have replaced someone’s name with Outsider. the context is the way i have seen Official Smart Trad Rats treat someone who is currently running what is effectively one of the main lesswrong discords.

i find the "read the sequences" why? because SEQUENCES disgusting, tbh it really does make us look like two-bit religious philosophers with no valid backing. the key difference between Outsider and the trad rats is not the sequences or the reading of them. it is a different neurotype. i don't even know for sure if the sequences are anywhere near as useful for him as they are for the type of person who loves to read them. and the amount of actual rationality the Outsider displays without having read the sequences should make a lot of trad rats stop and fucking think for a second about things like judging people who are different than them, ability to understand other humans, the value of maturity and wisdom, and how to learn and say things in different ways and the evils of demanding everyone else use your fucking compression scheme to communicate or they're wrong

i have found a lot of value from core concepts in the sequences, like, test your beliefs. do they work? do they actually work? test them again. believe what is real. no, your mind is lying to you, you believe what you want to believe. what do you do about that? well, whatever is real is the best thing for you to believe. look behind the curtain. fight through the pain.

the idea that the world is mechanistic and rational, and that magical thinking is unhelpful. but not everyone has the same gremlins that I do, or the average lwrong reader does. maybe the sequences are a good guide for people with a lot of neurosis to knock their minds into shape. I don't know. and I've read a lot of other things other than the sequences and had a lot of experiences that also shaped me into who I am. so how much of this can I credit the sequences? that's tough to answer. maybe their main benefit is that they set a core philosophy for me to ground myself in of "at the base, the world actually works off of science. yes, in that way too." which is something that seems obvious and apparent but people do not actually behave as if it were so. what i would like to see is "you are making this rationality error, you fucked up, look, read these sequences" or "you could have done this better if you'd read the sequences"

i'd like to see actual effective application of them which demonstrates that, yes, there really is that much value in the words for that person and the people who have read them understand that value deeply enough to be able to manipulate and apply it at will

what i have just observed is that a traveler approached a monastery and ended up fighting the monks and beating the shit out of them and they responded by saying "none of his techniques were in our famous book of fighting techniques,” and, rather than asking him "can you add a new chapter for these strange and alien tactics of of allusion and implication and shitposting and being a generally pleasant gregarious dude who gets along with most people, we do not know of them” instead they just keep saying READ OUR BOOK and this such an epic failure of core concepts of rationality like "make your beliefs pay rent" and "observe reality and think about it rather than foisting your preconceived view of how you think things should work onto everything" that i am flummoxed and saddened by what i have seen

there is a religious adoration of the Rationality Movement which is entirely undeserved and a massive "not invented here" syndrome and nobody has stopped to question why some nobody who doesn't know their eliezer is running the big server instead of all the people who trained themselves to win at life

what makes this even more baffling is that the entire rationality movement is a patchwork quilt of truths taken from different places. that’s our whole point, to reflect reality accurately. but I get the feeling that a lot of people in it are not really very open-minded and there are places they just don’t look.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m confused by Stuart Armstrong’s recent posts on AI Alignment Forum ,( here (link 1) , here (link 2) , etc. ). Probably I’m just not reading them thoroughly enough? I may have skimmed (which is to say, I did skim) parts of them.

But considering the “Cake or Death” problem which he links to, applying the idea I expressed in my recent post “How to evaluate how informative we expect an experiment to be” , where the “Score” function is “utility if we act based on the probability distribution \mu over the true reward function, given that t is the true reward function”, uh, well, it gives the corrected answer that the post describes after the “naive cake or death problem” section. Which, isn’t surprising. I assumed that the post I made recently is just another way of expressing the obvious way to do something. But, part of what I’m confused about is, in the “sophisticated cake or death problem” section, it says

What happened here? Well, this is a badly designed p(C(u)|w). It seems that it's credence in various utility function changes when it gets answers from programmers, but not from knowing what those answers are. And so therefore it'll only ask certain questions and not others (and do a lot of other nasty things), all to reach a utility function that it's easier for it to fulfil.

and, I’m confused as to, uh, why it’s way of updating its beliefs would work like that?

Why would you design something such that it can know what the outcome of an experiment would be, but not take that into account when updating its probability distribution?

I guess if you gave something the ability to update its beliefs about things, but added on a hack saying “If I tell you something, believe it”, but without making it, uh, believe that the things you are going to say will be true, and it also had a model of what it would believe in the future which took into account the fact that it will believe you, then that would make some sense.

But, like, why?

Perhaps I would be less confused if I read the posts more carefully. But I should be grading hw right now, not blogging.

edit: Ok, so the whole “conservation of evidence” thing is, as I’ve now read the linked lesswrong wiki page, is *about* the “if you know what you would think afterwards, you should update now” thing. So I guess maybe what they are talking about is, “If you make the agent which has a broken way of updating its beliefs, how can you transform that into a correct way of updating its beliefs”?

0 notes

Text

I'm going to explain how the torment nexus is supposed to work, because the real roko's basilisk is "understanding roko's basilisk" and you're going to join me.

Roko's basilisk came from a group called LessWrong, which I can only describe as a "cult of rationality" where techbros went to pat themselves on the back for brute-forcing their way through Philosophy 101, and is the product of two prior leaps of logic: One about teleportation, and one about the Prisoner's Dilemma.

1) Suppose you get into a teleporter that takes you apart atom by atom and carefully reassembles you in another room. All your particles are in the exact same states they were when you entered (don't ask questions, it's superscience) so you should have all the same memories and sense of self you did before. But what if you didn't disintegrate and now there are two of you? Are you both you now? What if the teleporter keeps 3D-printing you until it runs out of toner? What if you took the digitised scan all your clones are based on and compiled it as a computer program? "What's the basis of identity" has a lot of possible answers with different implications, but if you're just as afraid of changing your mind as you are of dying (i.e. mortified) then the deterministic choice is to act like all your identical copies are equally the "real you".

2) Two prisoners with sentences of six months each are offered the opportunity to inform on each other in exchange for being immediately freed. Whoever gets betrayed gets ten years added to their sentence, and they can't talk to each other. Game theory says rational prisoners should betray each other because it reduces their sentence by six months whether their sentence gets extended or not, but "superrational" prisoners (I promise this is a legit maths term, but you see the appeal for smarter-than-thous) will realise the other prisoner is thinking the same thing and trust each other to hold their tongues. But you, you're an extradoubleplusrational prisoner (this one I made up, copyright me 2023) who didn't even have to be told the rules and just deduced there's another prisoner through facts and logic, thus coming to a beneficial agreement with someone just by thinking about them hard enough. (LessWrong calls this "acausal bargaining".)

Neither of these interpretations is completely mad - this is philosophy, madness is relative - but if you can put yourself in the head of someone who's convinced that they've never made any assumptions in their entire life you might see where this is going.

The idea is, while even an AI that bootstrapped itself into godlike powers would not be capable of time travel (that would violate general relativity, we don't believe in magic), it would be capable of observing the universe around it to godlike levels of detail and using that data to simulate the history of the universe that led up to its creation (never mind that this would violate quantum mechanics). Naturally, that includes you. You can't distinguish yourself from your simulated double, so by point (1) you have to act like you're the same person. And you're smart enough that the AI you've imagined I mean deduced is indistinguishable from the real AI in the future... who, in accordance with point (2), is holding your double hostage and wants to make a deal...

...and because everyone in your community has balanced each others' egos on the tower of your collective infallibility, you can't just stop imagining the AI.

I feel like we don’t make fun of AI guys enough for believing in Roko’s basilisk.

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry this response is so overdue, I had to switch jobs, apartments, living situations, schedules and states, and I expected a much larger rebuttal, so I kept the tab open until I could devote the right amount of time to reading and answering it. I'm not clear on how long it's been, exactly, but I didn't want you to think I'd just ignored you.

Before anything else, I'll agree with you on this: I don't see why sending dickpics should be defensible under identity politics, including autistic identity politics, although I clearly haven't seen the post you're talking about. If that’s really all you responded to me over, I think we’re done.

With that out of the way, I should definitely be more clear as to what I mean by “can’t help”. Sometimes it’s a matter of weighing improvements by the amount of resources they take - if someone chided me for not speaking Samoan, I could honestly respond that I can’t help it, because it would take a huge time investment. On the other hand, it can be a problem of seeing why to make a certain change. Putting a napkin on the wrong side of a plate when setting a table is something which can absolutely be helped, but also something a person won’t have much motivation to remember and continue unless they can be convinced that table etiquette is important.

The problem can also be not noticing - a person who has “resting bitch face” may suffer for it their entire life. Even if they’re told that it’s a problem and given some instructions on how to smile consciously, as a less-than-perfect being they’re bound to slip up eventually - when that happens, they can’t help it because they can’t internalize the routine. And, most insidious of all, as in the example I gave of myself, sometimes people recognize that a problem exists but can’t articulate it. Social interaction is subtle, and there are plenty of ways to not make the grade, not all of which can be neatly identified or taught. It’s all well and good to say that there are “treatment methods” which can help, but that’s assuming this is just an autism problem and being a little naive about the efficacy of a lot of treatments. I’ve been in a couple over the years, and they may have been the most insulting and mind-numbing things I’ve ever been through, though I can at least acknowledge they weren’t being run by anyone with real expertise.

Now, for the meat of your response:

The phrase "LessWrong identity politics" was a tag I came up with the moment I decided to post this, and not an actual connection to some extant controversy. I certainly wasn’t suggesting it as a framework, and I have yet to see any other person than you even use the phrase "LessWrong identity politics", but even if there is one and I can be lumped into it, I care much more about whether the points I've made are wrong or not. As far as I'm aware, you've taken a few disparate posts from the rationalistsphere, condensed them into an IDpol framework, and are now valiantly arguing against it by talking over the points I'm actually discussing. And maybe those points should be made, and there really are lots of people who need to hear them, but if that’s the case you could probably have made a better case to the community at large by not hijacking my post to talk about them.

I mean, you can't seem to help identifying me with a group, no matter how I emphasize to you that I'm the only person I know with the opinions I'm expressing. And your response to being told you’re not arguing in good faith is not just “Well, you’re doing it too!”, it’s a bad example of me doing it too; I haven’t made any argument in terms of victim-playing or “gotchas”, and in fact I’ve been trying from my first post to separate those from the arguments people should be using! And as if that’s not enough, there are still other words you’ve put in my mouth! I've made no claim at being charitable, and I haven't called you anything like a sadist; I've only pointed out that you - you specifically - aren't interested in having the discussion I'm trying to have in this post. Judging by your response, that’s a completely fair assessment. Kindly stop trying to sock-puppet me into being whatever enemy you’re convinced you’re fighting.

I’m going to restate my last conclusion, because it hasn’t changed in the last month, and I’m hoping you’ll respond to it, whether to attack it or to acknowledge that you don’t have a problem with it. If you don’t respond to it, then I’m going to ignore you.

My point is that eccentric, obsessive, geeky, shut-in, awkward people receive a certain amount of distaste from other groups, and it’s not a one-way road, but ultimately the world would be slightly better if people didn’t assume that a man who wants to talk about his favorite things past anyone’s ability to care is a malevolent mansplainer and not a bit overexcited.

Since I’ve been a small cog in the autism identity politics discourse lately, I should point out that I see that as more of a fun gotcha than what I really think. It’s satisfying to point out that a lot of behavior nearby critics look down their noses at is inherent, and that they’re bad people by their own standards for sneering at it, but it’s also a little convenient.

I mean, autism is broad enough that it doesn’t quite fit their targets. The issue’s really with people who are socially awkward or childish but also very intelligent, or those who, as @paradigm-adrift puts it, don’t bother faking humility about how smart they are. And I called the people attacking this group “humanities students”, although by that I more mean the people who work or have hobbies in them.

Personally, this sort of generally male-geek criticism seems to exist just to bash the demographic instead of giving useful information. Cory Doctorow’s Eastern Standard Tribe has a minor section where the protagonist and his new girlfriend are mugged on a walk, and he cleverly scares away the attackers, at which point she wheels on him for not giving them money and exposing them both to danger. This seemed no different to me than any of the other fuck-you-geek-protagonist speeches I’d hesrd, but then it turns out that she’s abusive and a villain of the book, and I have to wonder if it was meant to be foreshadowing.

The best point I can make here, really, is that people are different and have different self-images and standards of politesse. And when social commentators are chomping at the bit to spit on reclusive, withdrawn, eccentric obsessives, they’re clearly looking for easy targets and more importantly they’re trying to reduce some of the most unusual members of our society into the same homogenous rightthinking mass as the critics’ average ingroup member/countryman/fantasy citizen.

Unlike most situations, autism’s a lovely excuse there because it implies a degree of helplessness on the target’s part that makes those critics look like dicks, but I don’t think we need to go that far to bring that advantage into play. It’s sufficient to say that it’s in the nature of some people to have these qualities, whether they’re useful or harmful, and criticizing them for it is both a waste of time and a failure to understand that not everyone is or should be like you.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shouldn’t it be “identity politickers”?

I regret to tell you that I’m not the elected representative of LessWrong, and if you weren’t so invested in ripping the community’s head off I think you might’ve noticed this post was about a belief I think is individual to me. And judging by notes, it’s not as if my writing is influencing the sphere an awful lot, so if you want to do a grand dissection of the great intellectual degeneratocracy, I’m not a good subject. Frankly I’m a little surprised someone read that and cared enough to answer, especially to be angry about it. (Did you just search for “lesswrong identity politics”?)

It does feel cynical to me to use autism as a defense against the sort of critics I’m talking about, although I never mentioned social justice and it doesn’t need a politicized label. However, the reason it feels cynical to me is that it’s too easy, and it invites in the exact criticisms you’re talking about. This repeated strawman of “I might be autistic, therefore you’re evil for criticizing me” doesn’t match up to the situation of actually being autistic and being told behavior you can’t help or don’t notice is toxic and wrong. I think the fact that you dodge that scenario when you’re paraphrasing the “IDpolsters” means you agree with me there.

I don’t like parading it around, and I haven’t talked about it in a couple of years, but if it makes you see me differently I do actually have a diagnosis. I got it when I was a kid, when I had to go to another state and take a test I barely remember. There’s always been something about me that rubs people the wrong way no matter how hard I’ve tried to comport myself to their standards, and whenever I’ve asked, even they can’t explain what it is to me. Part of why I can’t give you a list of behaviors is because most of the complaints stem from reactions to things the targets aren’t aware of or don't get, and whether that gap is psychological or cultural is irrelevant to the fact that it exists and is sometimes worth maintaining. And I’m sure saying “well, maybe you’re not that smart after all, pbbbbt!” makes you feel like you’ve won an argument, but it’s exactly as helpful to me as saying nothing at all.

And I know you’re not really saying that in good faith (“I don’t know what specific behaviors you mean, therefore kitten-murder must be allowed”), but if we’re going to treat each other like avatars of movements I think your words speak to a larger problem. You’re not interested in helping people, you’re interested in bashing them. And I agree that you have every right to do that (and this has never been about banning criticism to me; I support free speech to degrees that have annoyed the people around me), but I want you to understand that you’re not any more insightful or righteous than an Encyclopedia Dramatica editor when you’re doing it.

My point is that eccentric, obsessive, geeky, shut-in, awkward people receive a certain amount of distaste from other groups, and it’s not a one-way road, but ultimately the world would be slightly better if people didn’t assume that a man who wants to talk about his favorite things past anyone’s ability to care is a malevolent mansplainer and not a bit overexcited. Where dickpics come into it, I have no idea.

Since I’ve been a small cog in the autism identity politics discourse lately, I should point out that I see that as more of a fun gotcha than what I really think. It’s satisfying to point out that a lot of behavior nearby critics look down their noses at is inherent, and that they’re bad people by their own standards for sneering at it, but it’s also a little convenient.

I mean, autism is broad enough that it doesn’t quite fit their targets. The issue’s really with people who are socially awkward or childish but also very intelligent, or those who, as @paradigm-adrift puts it, don’t bother faking humility about how smart they are. And I called the people attacking this group “humanities students”, although by that I more mean the people who work or have hobbies in them.

Personally, this sort of generally male-geek criticism seems to exist just to bash the demographic instead of giving useful information. Cory Doctorow’s Eastern Standard Tribe has a minor section where the protagonist and his new girlfriend are mugged on a walk, and he cleverly scares away the attackers, at which point she wheels on him for not giving them money and exposing them both to danger. This seemed no different to me than any of the other fuck-you-geek-protagonist speeches I’d hesrd, but then it turns out that she’s abusive and a villain of the book, and I have to wonder if it was meant to be foreshadowing.

The best point I can make here, really, is that people are different and have different self-images and standards of politesse. And when social commentators are chomping at the bit to spit on reclusive, withdrawn, eccentric obsessives, they’re clearly looking for easy targets and more importantly they’re trying to reduce some of the most unusual members of our society into the same homogenous rightthinking mass as the critics’ average ingroup member/countryman/fantasy citizen.

Unlike most situations, autism’s a lovely excuse there because it implies a degree of helplessness on the target’s part that makes those critics look like dicks, but I don’t think we need to go that far to bring that advantage into play. It’s sufficient to say that it’s in the nature of some people to have these qualities, whether they’re useful or harmful, and criticizing them for it is both a waste of time and a failure to understand that not everyone is or should be like you.

25 notes

·

View notes