#linnaean taxonomy

Note

Birds are class Aves.

Sure, under Linnaean taxonomy. But, well,

A) Linnaeus was a eugenecist so his scientific opinions are suspect and his morality is awful

B) he didn't know about evolution

C) he didn't know about prehistoric life

so his classification system? Sucks ass. It doesn't work anymore. It no longer reflects the diversity of life.

Instead, scientists - almost across the board, now - use Clades, or evolutionary relationships. No rankings, no hierarchies, just clades. It allows us to properly place prehistoric life, it removes our reliance on traits (which are almost always arbitrary) in classifying organisms, and allows us to communicate the history of life just by talking about their relationships.

So, for your own edification, here's the full classification of birds as we currently know it, from biggest to smallest:

Biota/Earth-Based Life

Archaeans

Proteoarchaeota

Asgardians (Eukaryomorphans)

Eukaryota (note: Proteobacteria were added to an asgardian Eukaryote to form mitochondria)

Amorphea

Obazoa

Opisthokonts

Holozoa

Filozoa

Choanozoa

Metazoa (Animals)

ParaHoxozoa (Hox genes show up)

Planulozoa

Bilateria (all bilateran animals)

Nephrozoa

Deuterostomia (Deuterostomes)

Chordata (Chordates)

Olfactores

Vertebrata (Vertebrates)

Gnathostomata (Jawed Vertebrates)

Eugnathostomata

Osteichthyes (Bony Vertebrates)

Sarcopterygii (Lobe-Finned Fish)

Rhipidistia

Tetrapodomorpha

Eotetrapodiformes

Elpistostegalia

Stegocephalia

Tetrapoda (Tetrapods)

Reptiliomorpha

Amniota (animals that lay amniotic eggs, or evolved from ones that did)

Sauropsida/Reptilia (reptiles sensu lato)

Eureptilia

Diapsida

Neodiapsida

Sauria (reptiles sensu stricto)

Archelosauria

Archosauromorpha

Crocopoda

Archosauriformes

Eucrocopoda

Crurotarsi

Archosauria

Avemetatarsalia (Bird-line Archosaurs, birds sensu lato)

Ornithodira (Appearance of feathers, warm bloodedness)

Dinosauromorpha

Dinosauriformes

Dracohors

Dinosauria (fully upright posture; All Dinosaurs)

Saurischia (bird like bones & lungs)

Eusaurischia

Theropoda (permanently bipedal group)

Neotheropoda

Averostra

Tetanurae

Orionides

Avetheropoda

Coelurosauria

Tyrannoraptora

Maniraptoromorpha

Neocoelurosauria

Maniraptoriformes (feathered wings on arms)

Maniraptora

Pennaraptora

Paraves (fully sized winges, probable flighted ancestor)

Avialae

Avebrevicauda

Pygostylia (bird tails)

Ornithothoraces

Euornithes (wing configuration like modern birds)

Ornithuromorpha

Ornithurae

Neornithes (modern birds, with fully modern bird beaks)

idk if this was a gotcha, trying to be helpful, or genuine confusion, but here you go.

all of this, ftr, is on wikipedia, and you could have looked it up yourself.

671 notes

·

View notes

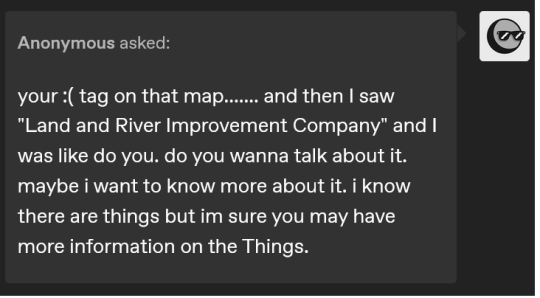

Photo

Science Saturday

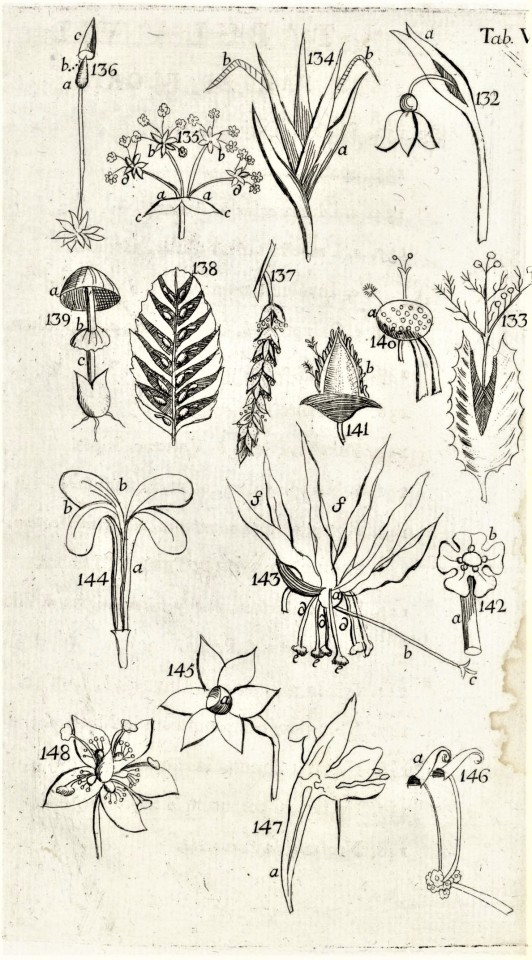

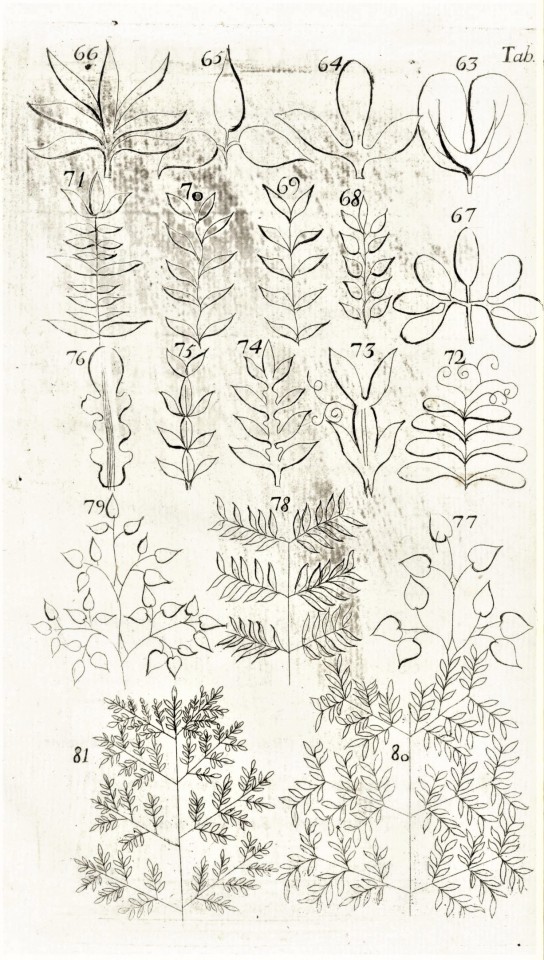

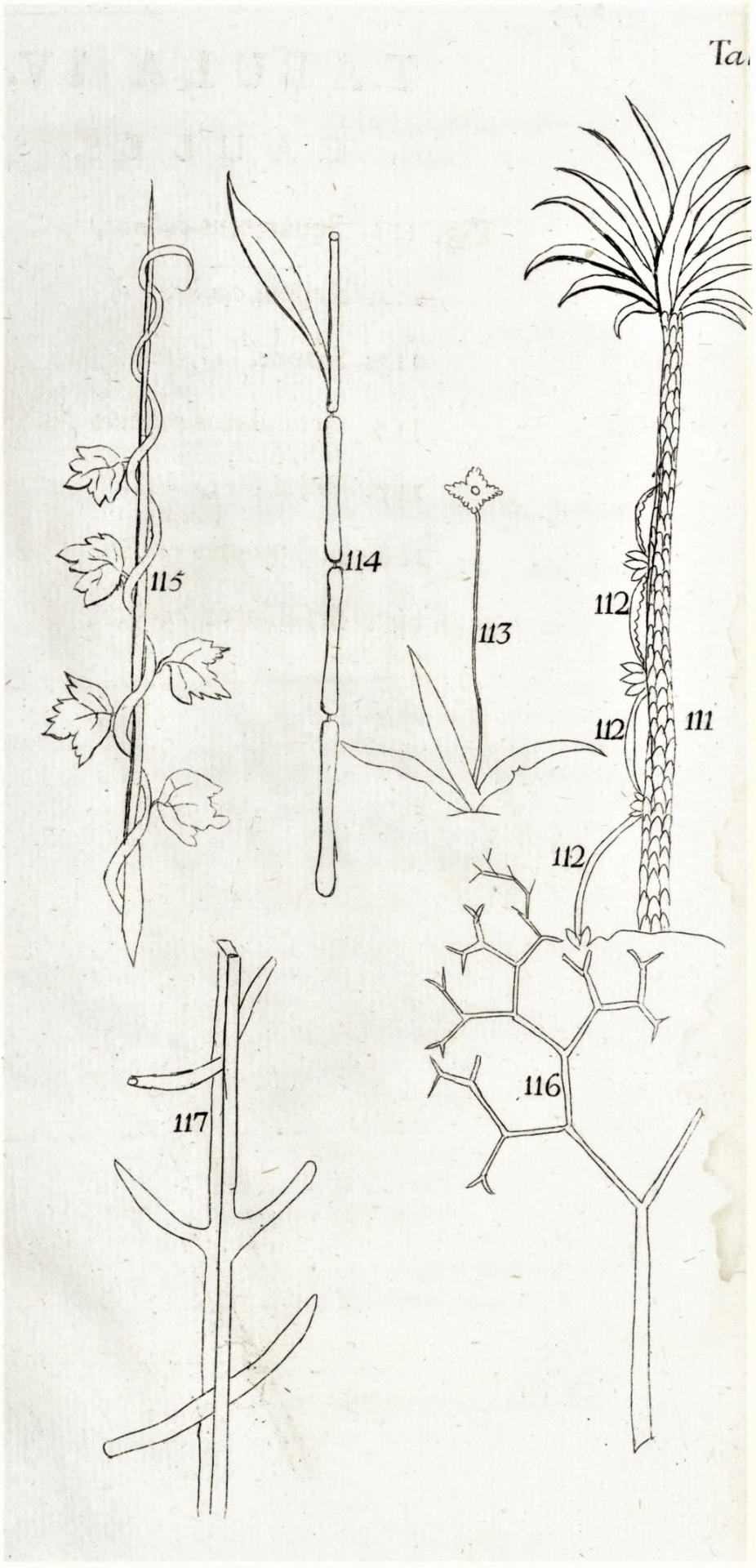

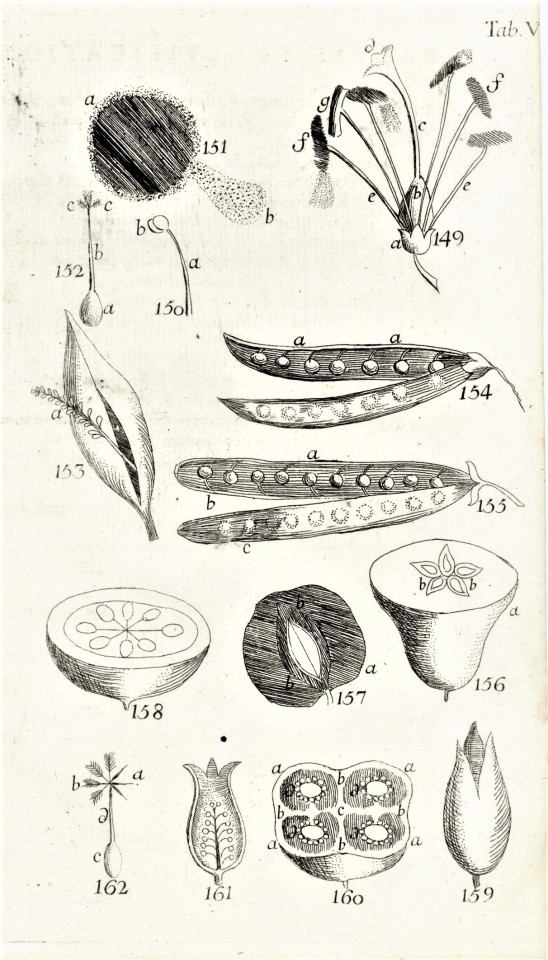

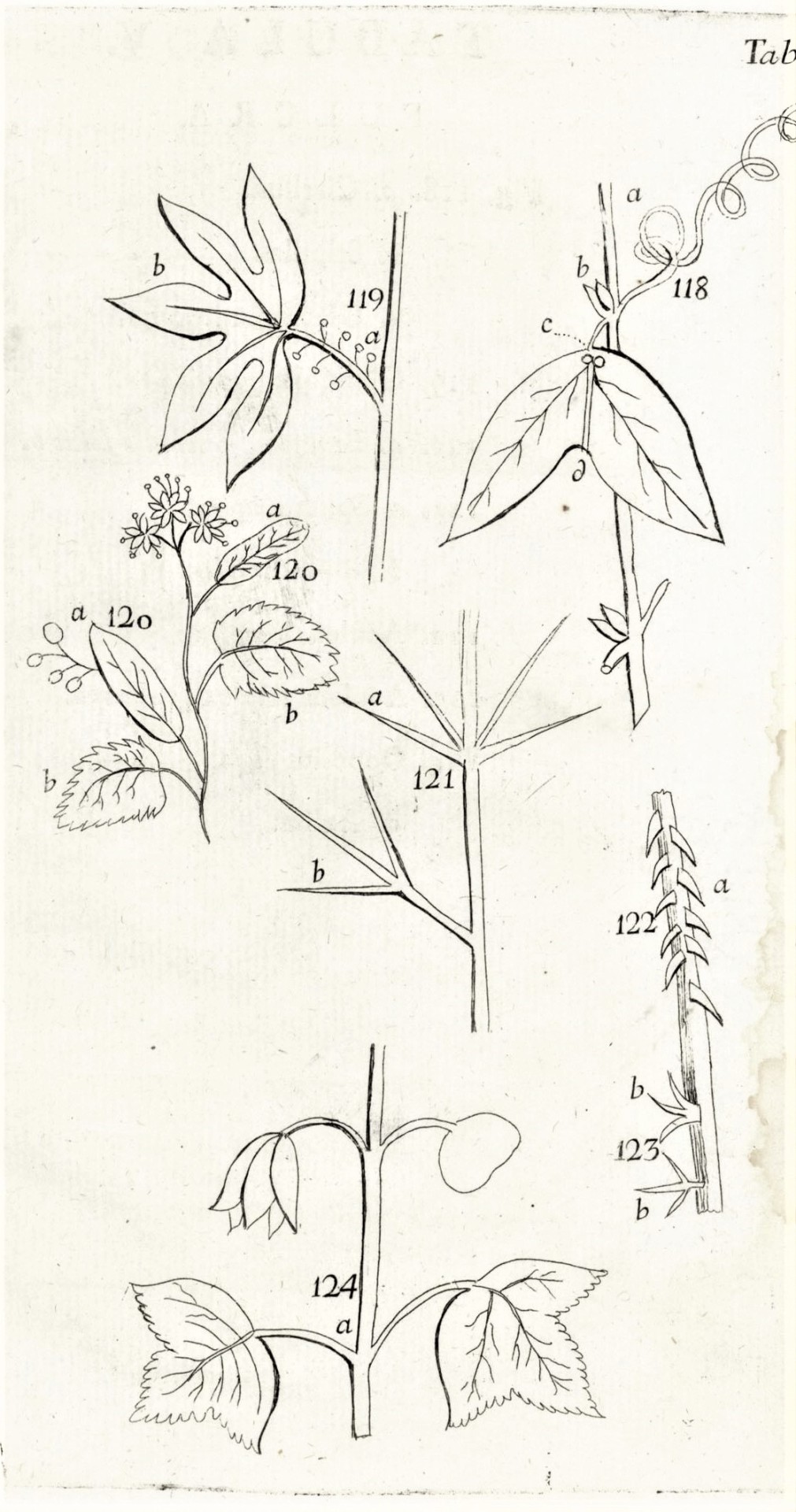

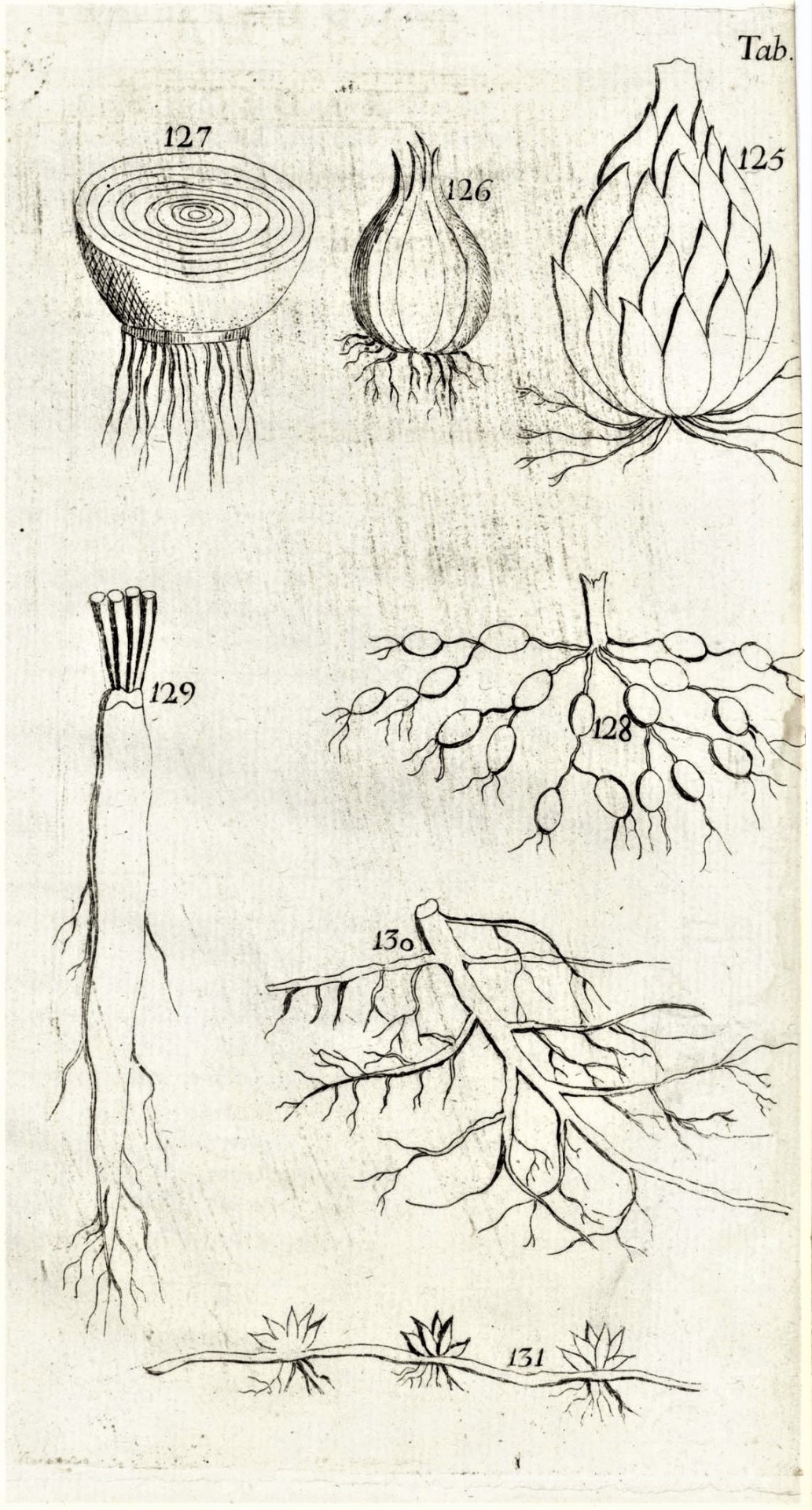

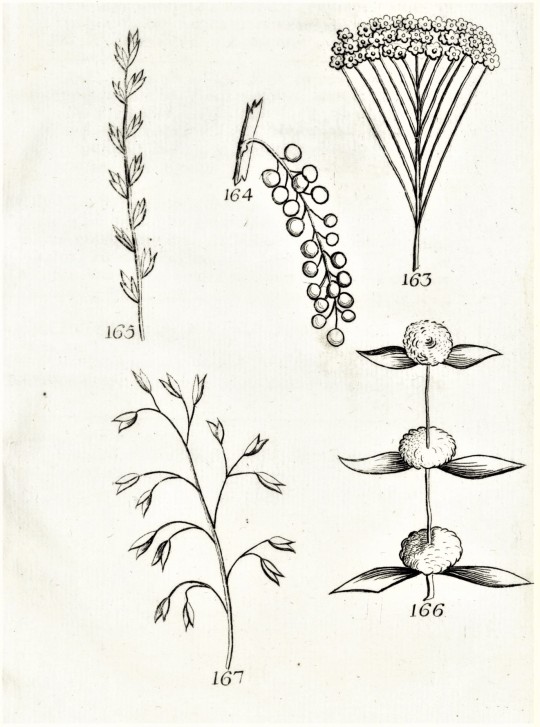

Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) is most well known for establishing a systematic binomial nomenclature for describing biological entities. This system was first published in his Philosophia Botanica, published in Stockholm and Amsterdam in 1751. This week we present engraved plates from a Spanish edition of this work, printed in Madrid by the widow and children of Pedro Marin in 1792 under the direction of Spanish botanist Casimiro Gómez de Ortega (1741-1818), with additional material by the Swedish botanist Johan Andreas Murray (1740-1791).

View more posts on works by Linnaeus.

View more Science Saturday posts.

#Science Saturday#Carl Linnaeus#Philosophia Botanica#binomial nomenclature#taxonomy#Linnaean taxonomy#engravings#copperplate engravings#Casimiro Gómez de Ortega#Johan Andreas Murray#Pedro Marin

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questions I have that I hope I'll be able to learn about when i start school in the fall

Do taxonomic ranks signify, even roughly, a particular amount of separation from other categories of organism, or are they totally arbitrary? How would you even quantify separation—time since a shared common ancestor, genetic similarity? Are two families in the same class generally a similar "distance" apart than another two families in a different class? Or are they basically annoying relics of Linnaean taxonomy that are still used because it's easier to just add categories like "infraorder" or "subfamily" than redo everything in an equally arbitrary way, and useless as an indicator of the level of relatedness of two organisms?

How do we make guesses about how often extinction happens? Say every big cat except lions goes extinct. Then a million years later lions have spread out and diversified into several new species. Now imagine that an alien civilization 100 years in the future is looking at the fossil record. How likely is it that the extinction of the big cats, excluding lions, is detectable in the fossil record?

I know about speciation, but what about de-speciation, where two species interbreed and merge back together again? We say that Neanderthals went extinct because of interbreeding with humans, or that red wolves are threatened by interbreeding with coyotes. Why is that considered to be extinction (or risk thereof) of one of the taxa? Is this all that rare throughout the history of life on Earth? Or is it possible that genera oscillate between speciation and de-speciation throughout time?

If you find a fossil of an animal and then find a fossil of that animal's ancestor from a million years earlier, are those two different species or what.

Why are we using the same system of categories to describe plants and animals when the mechanisms for speciation between the two of them appear WILDLY different?

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

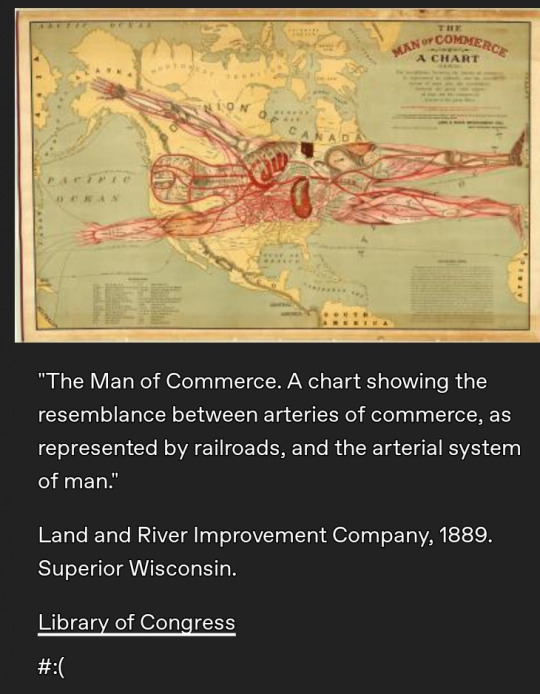

It's a big mess of hubris; the manipulative use of scientific language to legitimate/validate the status quo; Victorian/Gilded Age notions of resource extraction; the "rightness" of "land improvement"; and the inevitability of empire.

This was published in the United States one year before the massacre at Wounded Knee.

This was the final year-ish of the so-called "Indian Wars" when the US was "completing" its colonization of western North America; at the beginning of the Gilded Age and the zenith of power for industrial/corporate monopolies; when Britain, France, and the US were pursuing ambitious mega-projects across the planet like giant canals and dams; just as the US was about to begin its imperial occupations in Central America and Pacific islands; during the height of the "Scramble for Africa" when European powers were carving up that continent; with the British Empire at the ultimate peak of its power, after the Crown had taken direct control of India; in the years leading up to mass labor organizing and the industrialization of war precipitating the mass death of the two world wars.

This was also the time when new academic disciplines were formally professionalized (geology; anthropology; archaeology; ecology).

Classic example of Victorian-era (and emerging modernist and twentieth-century) imperial hubris which implies justification for its social hierarchies built on resource extraction and dispossession by invoking both emerging technical engineering prowess (trains, telegraphs, electricity) and the in-vogue scientific theories widely popularized at the time (Lyell's work, dinosaurs, and the geology discipline granting new understanding of the grand scale of deep time; Darwin's work and ideas of biological evolution; birth of anthropology as an academic discipline promoting the idea of "natural" linear progression from "savagery" to imperial civilization; the technical "efficiency" of monoculture/plantations; emerging systems ecology and new ideas of biogeographical regions).

While also simultaneously doing the work to, by implication, absolve them of ethical complicity/responsibility for the cruelty of their institutions by naturalizing those institutions (excusing the violence of wealth disparities, poverty, crowded factory laboring conditions, mass imprisonment, copper mines, South Asian famine, the industrialization of war eventually manifesting in the Great War, etc.) by claiming that "commerce is a science"; "pursuit of profit is Natural"; "empire is inevitable".

This tendency to invoke science as justification for imperial hegemony, whether in Britain in the 1880s or the United States in the 1920s and such, might be a continuation of earlier European ventures from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries which included the use of cartography, surveying/geography, Linnaean taxonomy, botany, and natural history to map colonies/botanical resources and build/justify plantations and commercial empires in the Portuguese slave ports, Dutch East Indies, or the Spanish Americas.

Some of the issues at play:

-- Commerce is "A Science". Commerce is shown to be both an ecological system (by illustrating it as if it were a landscape, which is kinda technically true) and a physiological system (by equating infrastructure/extraction networks with veins) suggesting wealth accumulation is Natural.

-- If commerce/capitalism are Natural, then evolutionary theory and linear histories suggest it is also Inevitable (it was not mass violence of a privileged few humans who spent centuries beating the Earth into submission to impose the Victorian/Gilded Age state of things, it was in fact simply a natural evolutionary progression). And if wealth accumulation is Natural, then it is only Right to pursue "land improvement".

-- US/European hubris. They can claim to perceive the planet in its apparent totality (as a globe, within the bounds of extraterrestrial space as if it were a laboratory or plantation). The planet and all its lifeforms are an extension of their body, implying a justified dominion.

-- However, their anxiety and suspicions about the stability of empire are belied by their fear of collapse and the simultaneous US/European obsession at the time with ancient civilizations, the "fall of Rome", classical ruins, etc. At this time, the professionalization of the field of archaeology had helped popularize images and stories of Sumer, Egypt, the Bronze Age, the Aegean, Rome, etc. And there was what Ann Stoler has called an "imperialist nostalgia" and a fascination with ancient ruins, as if Britain/US were heirs to the legacy of Athens and Rome. You can see elements of this in the turn of the century popularity of Theosophy/spiritualism, or the 1920s revival of "classical" fashions. This historicism also popularized a sort of "linear narrative" of history/empires, reinforced by simultaneous professionalization of anthropology, which insinuated that humans advance from a "primitive" state towards modernity's empires.

-- Meanwhile, from the first decades of the nineteenth century when Megalosaurus and Iguanodon helped to popularize fascination with dinosaurs, Georgian and later Victorian Britain became familiar with deep time and extinction, which probably contributed to British anxiety about extinction, imperial collapse, lastness, and death.

-- Simultaneously, the massive expansion of printed periodicals allowed for sensationalist narrativizing of science.

-- The masking of the cruelty in a euphemism like "land improvement". Like sentencing someone to a de facto slow death and deprivation in a prison but calling it a "sanatorium" or "reformatory". Or calling the mass amounts of poor, disabled, women, etc. underclasses of London "unfortunates". Whether it's Victorian Britain or early twentieth century United States: "Our empire is doing this for the betterment and advancement of all mankind."

-- If an ecosystem is conceived as a machine, "land improvement" actually means monoculture, high-density production, resource extraction, concentration.

-- The image depicts the body is itself is also a mere machine (dehumanization, etc.). And if human bodies are shown to be also systems, networks, machines like an ecosystem, then human bodies can also be concentrated for efficiency and productivity (literal concentration camps, prisons, factories, company towns, slums, dosshouses, etc.). This is the thinking that reduces humans and other creatures to objects, resources, to be concentrated and converted into wealth.

And so after the rise of railroads and coal-power and industrial factories in the earlier nineteenth century, the fin de siecle and Edwardian era then saw the expansion of domestic electricity, easier photography, telephones, radio, and automobiles. But you also witness the spread of mass imprisonment, warplanes, and machine guns, etc. And in the midst of this, the Victorian/Gilded Age also saw the rise of magazines, newspapers, mass media, pop-sci stuff, etc. So this wider array of published material, including visual stuff like maps and infographics could "win over" popular perception. This is nearly a century after the Haitian Revolution, so more and more people would have been able to witness and call out the contradictions and hypocrisies of these "civilized" nations, so scientific validation was important to empire's public image. (Think: 100 years prior, everyone witnessed widespread revolutions and slave rebellions, but now the European empires are still using indentured labor, expanding prisons, and growing even more powerful in Africa, etc. An outrage.)

Illustrations like this ...

It's people with power (or people with a vested interest in these institutions, people who aspire to climbing the social ladder, people who defend the status quo) looking around at the general state of things, observing all of the cruelty and precarity, and then using scientific discourses to concede and say "this was inevitable, this was natural" and not only that, but also "and this is good".

Related reading:

Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); "Science in the Nursery: the popularisation of science in Britain and France, 1761-1901" (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2011); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); "Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times" (Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Collette Le Petitcrops); “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden" (Sharae Deckard); "Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia's Plantation Economy" (Gregg Mitman, 2017); Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Ann Laura Stoler, 2013)

Fairy Tales, Natural History and Victorian Culture (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2014); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); "Shaping the beast: the nineteenth-century poetics of palaeontology" (Talairach-Vielmas, 2013); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2020)

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

question: does the appearance of Clutch Powers in s11 of Ninjago (formerly Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu) mean that Clutch Powers’ various media are a part of a the Ninjago franchise (naming based on longevity)? or is Ninjago a part of the Clutch Powers series (naming based on seniority a la Linnaean taxonomy)? is Ninjago: Dragons Rising a Clutch Powers series? discuss

for funsies 👍

#ninjago#clutch powers#lego#text✨#poll✨#this post brought to you by the ‘series by theme’ section on the LEGO tvs and movies wikipedia page#would you consider ninjago to be a sequel series to Lego: The Adventures of Clutch Powers (2010)?

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

my side-quest with this thesis has been checking all the scientific (Linnaean taxonomy) names for plants and animals mentioned in the thesis and inevitably only finding sources written by Bulmer, another anthropologist who was living with the Kalam around the same time as Inge and who spent a great deal of his time asking Kalam about flora and fauna. Bulmer and I have a fun secret rivalry which he doesn’t know about on account of having died in 1988; I like finding out whether or not specific species have been re-categorised since he wrote about them.

Problem is, as mentioned, there is very little written about random Kaytog Valley plants and animals that wasn’t written by Bulmer, and I can’t always access them for free. I had a little tantrum recently about not being able to access a paper he co-wrote about frogs and Inge sent it to me and it’s everything I wanted it to be. Look at this shit

I hope my husband is ready for me to spend six months announcing I’m ready to leave a room/event/building with only “the ngl nagl calls”

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Taxonomy

Every so often I get struck by the urge to try and make a somewhat coherent taxonomy for the dragons, because if HTTYD is meant to be ‘our world’ and the dragons are animals instead of like, magical beings who appeared out of the ether, they must have evolved.

I went through three iterations of this cladogram before settling on one I’m happy with (for now), so allow me to break it down for y’all:

For those who don’t know, Linnaean taxonomy (which I am using here) has seven main ranks, as well as sub ranks, which start off broad/general and get more and more specific. They are Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species. Dragons are in the Kingdom Animalia, the Phylum Chordata and the Class…

Okay so I originally put them in their own class, but assuming they’re reptiles, they’d more likely be considered a subclass, or superorder, within the Class Reptilia. It’s up to interpretation.

There are two Orders grouped under Drakontes. The first is Nykteromorpha, which are all the dragon species with a wing membrane that attaches from the shoulders down to the hips. The second is Ornisteromorpha, which are all the dragon species with a wing membrane that attaches at the shoulder and sometimes partway down the ribs for more support. This is the biggest order.

Each Order has two suborders. As you can see from the cladogram, we have the bat winged dragons with short necks, the bat winged dragons with long necks, the bird winged dragons with short necks and the bird winged dragons with long necks.

So there are two Orders, four Suborders, and eight Families. The Families are named after the most well known dragon species in each of those groups, e.g: Nadderidae, Furidae and Groncklidae.

Four of those Families are in turn split into two subfamilies, for the dragons that (I think) are more closely related to the titular species, and the dragons that are less closely related to them. For example, dragons that are most closely related to Furies are in the subfamily Furinae, whereas those less closely related are in the subfamily Parafurinae, meaning ‘almost/close to alike Furies’.

I could be totally off about this (there’s literally no way to tell) but I tried to base it on what I know of real evolution and taxonomy, and on the dragons body plans rather than shared features. Dragons with similar physical characteristics seem more likely to be related than dragons that look almost nothing alike and just happen to have certain abilities in common, such as flicking spines.

I think that pretty much sums everything up. Thanks for reading!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can’t let this go.

Canonically, Stede Bonnet is the father of modern taxonomy. Dryocampa rubicunda wasn’t discovered for 76 years, and the Linnaean system didn’t exist in 1717.

#things that keep me up at night#Our Flag Means Death#ofmd#Stede Bonnet#putting the homo in homo sapiens#sorry we're in the taxonomy AU now

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Easter!

This time I brought y'all an Easter Egg: Macroelongatoolithus carlylei from the Cretaceous (145–66 Ma), North America & Asia.

M. carlylei are eggs of gigantic oviraptorosaurs (like Beibeilong or Gigantoraptor).

Since the organism responsible for laying any given egg fossil is frequently unknown, M. carlylei is an so called 'oogenus'.

Scientists classify eggs using a parallel system of taxonomy separate from but modeled after the Linnaean system. This "parataxonomy" is called veterovata.

-Wikipedia

#paleoart#palaeoart#art#dinosaur#dino#prehistoric#paleontology#palaeontology#digitalart#Macroelongatoolithus#Elongatoolithidae#egg#easter#happy easter#easter egg#Macroelongatoolithus carlylensis#Macroelongatoolithus carlylei

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled Wednesday Library Series, Part 101

In Part the Ninety-Eighth, I promised the return of Ereshefsky’s Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy. This is that. In the intervening weeks I have finished it, griped to @krieper about it, and discussed it in broad strokes with my practical shoes-having former (and now accidentally, coincidentally, re-current) professor.

(The How)

I said before what I’d otherwise say here, bar this: in order to pay a ~reasonable amount for this copy, I had to go through a ~reputable third party book resale site. Those fuckers keep hitting me with new mailing lists. Unpleasant.

The Text

Ereshefsky’s argument is something like this: Linnaean taxonomy’s assumptions and rules are incorrect and burdensome, respectively; it is practically and philosophically beyond saving; a new system ought to be adopted. While he doesn’t definitely specify a new system, he makes 11 strong, ~clearly argued recommendations for what that system ought to look like and do.

Taken together, these points grandfather in existing taxa names but strip them of embedded meaning (e.g., family-level suffixes like -idae and -aceae) outsourcing information on inclusiveness to either numbers or indented lists, move all new names to unitalicized uninominal constructions (i.e., no more Genus species), do away with ranks entirely, and emphasize phylogenetic relationships when possible. This is not an uncontroversial set of suggestions, nor is it an entirely original one.

Ereshefsky does not like essentialism of genera. Not controversial. He does not like species essentialism. Less uncontroversial, but me too, bud. In fact he argues for the coexistence and co-utility of several equally valid concepts of species (e.g., ecospecies, phylospecies, biospecies) as ‘lineages’ which ‘crisscross the natural world’. Quite unpopular. His strongest point is that all such lineages represent historical entities (not contiguous historical individuals) whose internal relations are badly served by grouping and naming them like we currently do. Correct.

I enjoy his impulses toward dissatisfaction with existing system. I quite like many of his points about how they ought to work instead. I do not find myself compelled by his arguments, which occasionally feel sloppy. Maybe they’re not as sloppy as they seemed to be, but they did seem it. If I felt his illustration of alternative concepts was clear, I’d root for this more strongly. It’s interesting and mostly pretty bold and even sometimes avoids repeating itself.

(The Object)

Again, this section hardly beats new ground. Between the fact this is a university press hardcover and the case I made last time, I figure you get the picture. Apart from a well-times reuse of a Willi Hennig diagram, there are no surprises. Solid, attractive, basically predictable. It remains an unchallenging thing, but it’s got a decent feel to it.

The Why, Though?

Listen, I like this piece. I will absolutely be jamming bits of it further into my brain, and I will absolutely be recommending certain parts of it to certain people. Every time I find a new ~solid philosophy of biology text I wax slightly more annoying. Is it perverse to enjoy that? Perhaps so. Not the point.

I wish it gave more of a shit about complications like horizontal gene transfer and coherency among asexually reproducing organisms. I wish it used footnotes instead of endnotes. I wish it seemed more interested in the phenomena it discusses than it does, and I wish it seemed like it was written for an audience other than philosophers of taxonomy (like, say, taxonomists, or even (hell) biologists of broader stripes). Alas.

I stand by that second chapter; phenomenal work there. Absolutely killer bibliography. That alone is almost worth the price of admission.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curated List of My Tumblr Posts on Paleontology, Classification, Doraemon, etc.

I don’t currently take asks on this blog, but over the years I’ve accumulated a good amount of material on here that I essentially haven’t posted anywhere else. Given that finding old posts on Tumblr can be a difficult and arduous task, I’ve decided to assemble a curated selection of links to my posts that I think are of particular interest (whether on a general or personal level). These are often posts that have been especially popular, posts that I especially enjoyed writing, or both. Yes, I’m including the Doraemon reviews. 😛 For ease of access, I have also replicated this list on a page on this blog, which I will try to keep updated as I deem necessary.

Paleontology Resources

What are some good introductory resources for dinosaur paleontology?

What are some good YouTube channels about paleontology? (needs updating)

Some ways to access paywalled scientific papers (and why I won’t repost published phylogenetic figures on @new-dinosaurs)

What should one major in college to get into paleontology?

How do I make phylogenetic diagrams?

How to subscribe to the Dinosaur Mailing List

Specific Dinosaur Questions

How flexible are dinosaur tails?

What types of dinosaurs have feathers?

Wasn’t there a study showing that feathers were not an ancestral trait of dinosaurs?

How reliable are melanosomes for reconstructing the colors of extinct dinosaurs?

Why does paleoart of feathered dinosaurs tend to show the tip of snout unfeathered?

Is it true that non-avian dinosaurs couldn’t roar?

Which dinosaurian herbivores are foregut fermenters and which ones are hindgut fermenters?

When did dinosaurs evolve hollow bones?

Could sauropods swim?

Can any theropods pronate their hands? (And how about other reptiles?)

Were giant maniraptoriforms likely to have been featherless?

Did flightless non-avialan pennaraptorans have feather barbules?

Would Microraptor and Anchiornis have had trouble walking due to their large hindlimb feathers?

What do we know about the social and reproductive behaviors of dromaeosaurids?

Did bird ancestors evolve flight from the ground up or trees down? How might flight have evolved from the ground up? Do we have extant analogues for such a process?

How do we know birds are actually dinosaurs, and that we haven’t been misled by convergent evolution?

Why do birds have backward-pointing dewclaws?

What is the most likely phylogeny of modern birds?

Are eider ducks the fastest animals in the world?

Were there penguins in the Cretaceous?

Why do bateleur eagles have short tail feathers?

Do all owls have asymmetrical ears?

Are falcons closely related to parrots?

How many times did poison evolve in songbirds?

Taxonomy, Nomenclature, and Phylogenetics

How do you pluralize genus/species names?

What is the phylogenetic species concept?

What is wrong with ranked/Linnaean taxonomy?

If birds are reptiles, shouldn’t tetrapods be considered fish?

Should we avoid calling birds dinosaurs because they were not traditionally called dinosaurs?

How is phylogenetic nomenclature reconciled with the fact that species must have evolved from other species?

What is a synapomorphy and how do we identify one?

How often do morphological and molecular phylogenetics agree?

General/Other Biology

Should the study of birds be included under herpetology?

Why is monogamy more common in birds than in mammals?

We don’t know what ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians are (needs updating)

How do reptiles drink?

How to identify a rodent skull

Why do mammals have ear flaps?

Could a mammal evolve as many neck vertebrae as a bird?

How can you tell the position of an animal’s ears by looking at its skull?

What is the difference between mesothermy and endothermy?

Why has the "Handicap Principle” been disputed?

Does any organic material remain in fossils?

Does it worry me that paleontologists will run out of fossils to discover?

What do I think about using humor in scientific outreach?

Just for Fun

Meme about fossil bird books

Fusion is a cheap tactic to make weak reptiles stronger

Meme about horses in geology

What are some works of paleo-fiction that I enjoy? (needs updating)

What are some webcomics about extinct animals that I enjoy? (needs updating)

List of science-themed music artists (needs updating)

Phylogeny (“Under the Sea” parody)

We don’t talk about Spino

Are there non-talking horses in Equestria (from My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic)?

Hilda and the nature of revelations

Doraemon

Movie review: Nobita’s Dinosaur (1980) and Nobita’s Dinosaur (2006)

Movie review: The Records of Nobita, Spaceblazer (1981) and The New Record of Nobita’s Spaceblazer (2009)

Movie review: Nobita and the Haunts of Evil (1982) and New Nobita’s Great Demon (2014)

Movie review: Nobita and the Castle of the Undersea Devil (1983)

Movie review: Nobita’s Great Adventure into the Underworld (1984) and Nobita’s New Great Adventure into the Underworld (2007)

Movie review: Nobita’s Little Star Wars (1985) and Nobita’s Little Star Wars 2021 (2022)

Movie review: Nobita and the Steel Troops (1986) and Nobita and the New Steel Troops (2011)

Movie review: Nobita and the Knights on Dinosaurs (1987)

Movie review: The Record of Nobita’s Parallel Visit to the West (1988)

Movie review: Nobita and the Birth of Japan (1989) and Nobita and the Birth of Japan (2016)

Movie review: Nobita and the Animal Planet (1990)

Movie review: Nobita’s Dorabian Nights (1991)

Movie review: Nobita and the Kingdom of Clouds (1992)

Movie review: Nobita and the Tin Labyrinth (1993)

Movie review: Nobita’s Three Visionary Swordsmen (1994)

Movie review: Nobita’s Diary on the Creation of the World (1995)

Movie review: Nobita and the Galaxy Super-express (1996)

Movie review: Nobita and the Spiral City (1997)

Movie review: Nobita’s Great Adventure in the South Seas (1998)

Movie review: Nobita Drifts in the Universe (1999)

Movie review: Nobita and the Legend of the Sun King (2000)

Movie review: Nobita and the Winged Braves (2001)

Movie review: Nobita in the Robot Kingdom (2002)

Movie review: Nobita and the Windmasters (2003)

Movie review: Nobita in the Wan-Nyan Spacetime Odyssey (2004)

Movie review: Nobita and the Green Giant Legend (2008)

Movie review: Nobita’s Great Battle of the Mermaid King (2010)

Movie review: Nobita and the Island of Miracles (2012)

Movie review: Nobita’s Secret Gadget Museum (2013)

Movie review: Stand by Me Doraemon (2014)

Movie review: Nobita’s Space Heroes (2015)

Movie review: Nobita’s Great Adventure in the Antarctic Kachi Kochi (2017)

Movie review: Nobita’s Treasure Island (2018)

Movie review: Nobita’s Chronicle of the Moon Exploration (2019)

Movie review: Nobita’s New Dinosaur (2020)

Movie review: Stand by Me Doraemon 2 (2020)

Ranking the Doraemon movies (1980–2022)

Where to find Doraemon in English

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

If we are moving away from linnean taxonomy, how come we still do binomial nomenclature, wasn't that developed as part of his taxonomy?

Hooooooooboy

the reason for THAT is that a lot of scientists still think species are a real thing that need a real descriptor

also, that's how we've named pretty much every organism. if we got rid of it, suddenly we don't know how to talk about them

like, most of the linnaean groups were assigned to clades, its just certain ones - like bird or fish - didn't fit well anymore. Mammal was pretty easy to assign, same with animal or plant.

So, ideally, species would just be the smallest independent evolutionary unit. They're not, right now, because everyone has their own version of species. But that would be the ideal.

Whether or not genera can be monophyletic is a whole other kettle of worms.

303 notes

·

View notes

Text

with all those taxonomy polls going around I'm surprised by the amount of grown adults about my age who were unfamiliar with the concept of cladistics. like in my hometown we learned that in high school. I mean they did still teach us linnaean taxonomy first, but only in lower grades, not in high school biology. is that out of the norm?

#ofc there's schools that don't teach evolution period#but I would think if they taught evolution at all they'd do at least a little bit of cladistics

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Science in Nature Interpretation

Even though there is no prompt for this weeks blog posts, I felt that the title of the unit resonated with me. Science has always been a major passion of mine, and science is likely one of the most common mediums for nature interpretation. There are many different fields of scientific discovery fully focused on the natural world, such as ecology, zoology, botany and more. Even anthropology has roots in different natural environments, where a anthropologist must acknowledge the environment a culture grows in. As there are so many different fields, an important aspect of science must be to maintain a consistent nomenclature of understanding. Names of things must be the same regardless of field, so that when a scientist or anyone for that matter reads a paper, they can immediately distinguish what they are talking about. Their is an elegance to this work, differing fields each have their own societies of experts that decide on the proper names. Almost all of these fields follow some kind of Linnaean classification, which follows a hierarchy of levels of relatedness. This allows for the very large pool of plants, animals, and fungi alike to be classified efficiently. However, this wasn't always the case. Taxonomy, or the study of classification could be considered one of the oldest forms of science. It was first practiced by Aristotle, who separated living things into two categories, plants and animals. This classification was taken and advanced by his students, to give us more and more in depth analysis of their anatomies and histories. Some used these classifications to prop up and put down certain species, claiming some more primitive than others. This shows something that is very common throughout human history, it is almost human nature to classify everything into various categories and boxes. We saw this in the privilege section of the blog, where some people can be looked over due to preconceived boxes we have put them in. But these boxes are usually surface level, there is commonly much more to get the whole picture. One such example is from the TED talk "for the Love of Birds", where Washington Wachira highlights the many differences of feathermakers. He mentions that only one class of animals on earth can make feathers, birds. But as the talk continues, he goes over the many ways that birds are different. From the vulture to the bald eagle to the guinea fowl to the penguin, all of these animals are within the same bird classification, and yet all of them are majorly different. This brings me back to my main love of science, as it cannot always be interpreted the same way. In the way that science wants to classify things into categories, those categories cannot always be the same for everyone. The take home message from this idea, is that the scientific lens will not always hold the correct interpretation of nature, and it is important to constantly be thinking outside of the boxes.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A thing that I love to do is to intentionally unlearn English common names for plants and animals. Ascribing of strict formal names to living things for processing through institutionalized knowledge systems is an act of capture. And I am not interested in capturing, possessing, any creature.

What do some English common names teach us about a creature? Names are powerful. These are things that I often contemplate together in relation to each other: “folk” taxonomy, animal naming conventions, erasure of local environmental knowledge, the theft and extraction of Indigenous language and knowledge, and rare and endemic species with specific microhabitat preferences.

---

You might come to find that a creature, like a frog in the tropical Andes, is named for a museum curator in London who had never visited the Andes, or the frog is named after an eighteenth century plantation owner who contracted the European land surveyors to map the area.

There are so many creatures named after racists, eugenicists, violent colonizers. Of course, Linnaean taxonomic naming conventions were being established alongside the height of European maritime dominance, plantation slavery, and colonization of the American hemisphere, Australia, South Asia, the tropics.

A frog might be named after an imperial British adventurer who recorded the creature for audiences at European museums. They called “dibs” on the frog, despite the fact that local Indigenous communities may have had an ongoing relationship with the creature for centuries. So instead I’m interested in trying to learn a “folk” name for the creature, or instead I would apply a new name for an animal based on the geographic area, ecoregion, plant community, or ecocultural region that the creature was most closely associated with.

---

Here’s a situation:

There is a relatively little-known salamander species. It is superlative. The terrestrial adults are enormous, and can be purple-ish in color, marked with gold speckles that seem to glow like glitter. They’re one of the only salamanders on the planet that can vocalize. They live in habitat alongside grizzly bears, mountain lion, wolverine, moose, unique lichen-eating mountain caribou, land snails, big ferns. The aquatic larvae can reach lengths of over 30 centimeters (1 foot), and they live not in still water like ponds and lakes as most other salamander larvae, but instead they swim around in fast-flowing streams.

It’s an endemic species. It lives in just a few small rivers’ watersheds, mostly in small, fast-flowing, cold, clear mountain streams in temperate rainforest ecosystems in the Columbia Mountains of the Northern Rockies, almost entirely within the arbitrary political borders of the US state of “Idaho,” on the traditional land of Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) people and Schitsu’umsh (Skitswish/Coeur d’Alene) people.

And it’s official common name: “Idaho giant salamander.” Not cool. Does the salamander have a meaningful reciprocal relationship with a political entity less than 200 years old, or does the salamander have a relationship with the ancient cedars of the rainforest? Which has existed longer: the arbitrary political entity of Idaho, or the Nimiipuu people? What do some English common names teach us about a creature? Names are powerful. Is the salamander named after the streams, the source of its life? Is it named after the temperate rainforest ecoregion, this safe harbor of fertile vegetation? Does its name refer to the endemic tailed frogs or other aquatic creatures that it relies on for food? Does the name reference the Nimiipuu, who have known the amphibian for centuries? Even the region’s name (”Columbia Mountains”) is a reference to one of history’s most notorious celebrities.

---

Here’s something from Robin Wall Kimmerer:

In the English language, if we want to speak of that sugar maple or that salamander, the only grammar that we have to do so is to call those beings an “it.” [...] In Potawatomi, the cases that we have are animate and inanimate, and it is impossible in our language to speak of other living beings as “it”s. [...] [W]hen we name something, often with a scientific name, this name becomes almost an end to inquiry. We sort of say, well, we know it now. We’re able to systematize it […]. It’s such a mechanical, wooden representation of what a plant really is. And we reduce them tremendously if we just think about them [solely] as physical elements of the ecosystem. […] This comes back to what I think of as the innocent or childlike way of knowing. Actually, that’s a terrible thing to call it. We say it’s an innocent way of knowing, and, in fact, it’s a very worldly and wise way of knowing. That kind of deep attention that we pay as children is something that I cherish, that I think we all can cherish and reclaim, because attention is that doorway to gratitude, the doorway to wonder, the doorway to reciprocity.

Words of Robin Wall Kimmerer. Interviewed by Krista Tippett. “On Being with Krista Tippett - Robin Wall Kimmerer: The Intelligence in All Kinds of Life.” February 2016.

---

It’s also important to me to clarify that, when referencing an Indigenous name or term for landmarks, places, plants, animals, etc. I only really feel comfortable doing so if the name is explicitly used by and/or confirmed to be accurate by speakers, researchers, knowledge-holders, etc. from that Indigenous community. And I also don’t want to use/share a name/term if the name/term was “collected” (appropriated, extracted) by a chauvinistic white academic or paternalistic Euro-American “ethnologist” or reproduced in a 1950s ethnobotany book or something. I especially don’t like relying on the testimony of, like, Euro-American missionaries or “traders’ who recorded terms in their personal journal in the 1750s or something.

How were those terms encountered?

How were they “extracted”?

Under duress?

Were these names, this environmental knowledge, willingly shared?

What ethical implications are there, of accepting secondhand information from an invading “pioneer”?

Many times, I’ll be reading a paper, maybe a “contempoary” paper from the past 10 years, and see references to a cool-sounding place-name or alternative name for a creature, and I’ve thought “wow, the connotations of the name sound really interesting, I wonder where this was learned,” and I’ll check the bibliography, and the “Indigenous name” was taken from a 1965 academic article, which itself was taken from a 1922 ethnology article sponsored by the F0rd Motor Company in pursuit of stealing local plant knowledge and land titles for rubber plantations or something, and that info itself was taken from an 1874 report from settler-colonial surveyors interviewing “locals” while traveling in company with an ex-government employee “cowboy” who had previously murdered at least 5 of the “locals.” So that, often in Euro-American “Knowledge” or “Science”, when trying to determine the Source Of A Fact, there is this blatant lineage of theft and violence and roundabout superficial self-referencing.

Even in relatively modern academic journals. Let’s say, in the 1990s, a European academic does “field research” in Amazonia. Maybe they record an “accurate” term, and I read about it in a paper. The academic says that they have a “profound respect” for “the culture”. Does this make it OK to “take” their terms? Does this make it more acceptable to “extract” a language as if it were a resource, a possession? Does it change the fact that the sponsoring academic institution or the publishing journal are both entangled with corporate extraction and ongoing (neo)colonial financialization, dispossession, debt, etc.?

So (1) you’re presented with names/terms which are probably inaccurate and which you have no way of confirming because of the convoluted way the term was passed down through settler-colonial knowledge-systematization institutions; and/or (2) more importantly, you’re presented with names/terms stolen, often at threat of violence; or (3) even in “good” scenarios with an accurate term and a so-called self-professed “respectful observer”, you’re presented with names/terms which have great power, connected to a specific culture and landscape, which should be treated with reverence and deep care, but which can easily be stolen and appropriated by popular media, wielding the power of the name in contexts where it doesn’t belong, a betrayal to the people, place, and/or creature.

---

Names imply or explicitly reveal the life of a creature or place, and also imply the connections between the creature/place being named, and the other worlds and relationships it influences and interacts with.

If i am not from the community that conceived the term/language, (1) it doesn’t feel honorable appropriating their language for myself, especially if I don’t have ongoing personal connection to people, places; (2) it doesn’t feel honorable, or all that reliable, to accept at face value the accuracy of a language/term if it’s being reported secondhand by a Euro-American academic intermediary, especially if that language was recorded during periods when Euro-American observers were actively engaged in colonization; and (3) it doesn’t feel honorable to use what might even be accurate Indigenous language/terminology if it was recorded/learned/stolen/promoted by Euro-American observers, unless there is explicit permission from native speakers to use the word, or unless native speakers actively encourage the acknowledgement of the words, maybe for purposes like language revitalization.

There is power and knowledge in a name. using a name involves serious responsibility. i feel that some names aren’t for me to invoke.

---

I think that maybe no name can do justice to the entire rich existence of a creature, but we can really do better than some English common names, especially in those cases when an animal is named after a lone individual human. And so, in naming, there might be a difficult decision to make. Do you name a creature for its behavior, its location, its appearance, its season of activity, its prefered habitat, its companion species? Maybe you have your own, personal, relationship with the creature. A living thing has so many interweaved relationships with others. Maybe its “meaning” changes with context or season or emotional state of the human observer. Maybe I will sometimes call the “Idaho giant salamander” something more fitting. Maybe I’ll call it “the cedar salamander” or the “guardian of the waterfall pools” or “the giant of the stream” or “moss dragon” or whatever. Depends on the mood, context, whatever.

We are all of us, salamander and human, more rich and complex than associations with mere behavior, appearance, habitat preference, or the surveyors that try to capture and catalogue us. And sometimes, I’m uncomfortable enclosing us with a singular denomination, with a strict name. I don’t assume that I know enough about a living thing to possess it through formal naming conventions.

#this is all just copy pasted and slightly edited from older posts of mine on this site#but the naming conventions of the frogs in Ecaudorian tropical Andes had me thinking about this#abolition#interspecies#ecology

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

species don’t exist — i mean, obviously, they do. but they aren’t objective. species are (as most things are) a cultural construction, a coalition of humans deciding where and when to draw what lines. constantly in debate: did you know paleoanthropologists are unintentionally incentivized to claim to have discovered entire new genera along the path of human evolution because they are more likely to generate media buzz and gain desperately needed funding. thousands of plants may be categorized together but a centimeter’s difference in skull thickness warrants an entire new genus name. we are more genetically similar to chimpanzees than they are to their fellow non-human primates, but due to the rules of Linnaean taxonomy humanity will never be collapsed into the same genus as them because the rules dictate that the older genus name prevails: humanity would never accept becoming Pan sapiens, especially not after it took decades for it even to be accepted that humans were a part of the taxonomy in the first place. even the most basic of criteria we’ve used in the past to decide where a species stops and starts continues to be debunked - fish from entire opposites of the world can produce fertile offspring. analogous evolution can find lines that split millions of years back creating critters that would be side by side in a disney cartoon. categorization is a eternal battleground of western scientific standards requiring universalized objective qualifiers vs. the futile efforts to recognize the unmeasurable amounts of nuance held in traditional ecological knowledge — versus the fact that, inevitably, it all boils down to a vast continuum contained with only a few percentage points of variation in the squiggly lines that tell the cells of everything on the entire globe how to eat

#PONDERING . i should cite some of these with sources but i’m pondering pop science and genuinely curious how many people have got the full#‘the way we categorize living beings into species isn’t an innate trackable quality in dna but a constructed system of assigning names to#certain observable traits - be those visible to the eye or the microscope on a chromosome#<- has had no less than five evolution lectures at varying levels of complexity in the last three years <- anthropology student#i am approaching this both from a scientific perspective (genetic variation is so vast that there are many cases in which species distincti#ons boil down to two creatures or plants just being considered different by the people who interacted with them)#AND an anthropological linguistic one (those ways of categorizing animals or plants are inherently cultural and there is no objective#inherent quality of those plants/animals/fungi/whatever that would say it’s the binomial name or the colloquial name or anything at all)#text✨#idk what i’m doing. species don’t exist much like gender it’s biologically ambiguous and culturally valuable

7 notes

·

View notes