#lisa feldman barrett

Text

latest headlines:

(techmonitor.ai)

vs the book How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain (Lisa Feldman Barrett, 2017)

"These same inconsistencies show up in infants.

If facial expressions are universal, then babies should be even more likely than adults to express anger with a scowl and sadness with a pout, because they’re too young to learn rules of social appropriateness.

And yet when scientists observe infants in situations that should evoke emotion, the infants do not make the expected expressions. (…)

It means that on different occasions, in different contexts, in different studies, within the same individual and across different individuals, the same emotion category involves different bodily responses.

Variation, not uniformity, is the norm.

These results are consistent with what physiologists have known for over fifty years: different behaviors have different patterns of heart rate, breathing, and so on to support their unique movements.

Despite tremendous time and investment, research has not revealed a consistent bodily fingerprint for even a single emotion. (…)

Emotion concepts are the secret ingredient behind the success of the basic emotion method.

These concepts make certain facial configurations appear universally recognizable as emotional expressions when, in fact, they’re not.

Instead, we all construct perceptions of each other’s emotions.

We perceive others as happy, sad, or angry by applying our own emotion concepts to their moving faces and bodies.

We likewise apply emotion concepts to voices and construct the experience of hearing emotional sounds. (…)

As emotion concepts become more remote, people do worse and worse at recognizing the emotions that the posed stereotypes are supposedly displaying.

This progression is strong evidence that people see an emotion in a face only if they possess the corresponding emotion concept, because they require that knowledge to construct perceptions in the moment. (…)

They only appear to be universal under certain conditions—when you give people a tiny bit of information about Western emotion concepts, intentionally or not."

more: tagged/how emotions are made

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wow. Do yourself a favor and listen to this all the way through. So many nuggets of life changing wisdom of self perception. we are always a 2 way communication between body and brain, often called top down and bottom up in psychotherapy.

Emotions are a summary of body-to-brain signals (body homeostasis). Feeling are a story your brain constructs to predict an outcome based on past experiences and current body summary.. Depression starts off as a significant biochemical imbalance to conserve resources: if not corrected it becomes the story that makes breaking free of depression "feel" unsafe and impossible. But creating new experiences in the present will eventually allow change in how your brain rewrites its story about the past and therefore about the future..thus changing your default emotion and current feelings.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Your social reality isn’t an absolute reality. | Lisa Feldman Barrett

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your brain doesn’t detect reality. It creates it.

Our perception of reality is not an exact representation of the objective truth but rather a combination of sensory inputs and the brain’s interpretation of these signals. This interpretation is influenced by past experiences and is often predictive, with the brain creating categories of similar instances to anticipate future events.

Follow The Well

Facebook:…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

youtube

Can you look at someone's face and know what they're feeling? Does everyone experience happiness, sadness and anxiety the same way? What are emotions anyway? For the past 25 years, psychology professor Lisa Feldman Barrett has mapped facial expressions, scanned brains and analyzed hundreds of physiology studies to understand what emotions really are. She shares the results of her exhaustive research -- and explains how we may have more control over our emotions than we think.

Check out more TED Talks: http://www.ted.com

The TED Talks channel features the best talks and performances from the TED Conference, where the world's leading thinkers and doers give the talk of their lives in 18 minutes (or less). Look for talks on Technology, Entertainment and Design -- plus science, business, global issues, the arts and more.

Follow TED on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/TEDTalks

Like TED on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TED

#Lisa Feldman Barrett#emotions#affect#psychology#facial expressions#physiology#exhaustive research#tedtalks#ted

0 notes

Text

i need to talk about ✨ this ✨ lovely book

dr. barrett is revered for her revolutionary research in both psychology and neuroscience, and this book she created reveals many insights of the human brain that each and every one of us carries

with what she’s learned from her studies and research applications, dr. barrett breaks down the brain’s nitty-gritty complexities in seven and a half easy-to-comprehend lessons

her balance between scientific terminologies and relatable examples makes this book a must read for anyone whom wishes to understand their brain a bit more (i’m looking at you fellow mentally ill people!!!)

my personal favorite lesson is number seven: “our brains can create reality” :)

#book recommendations#booklr#books and reading#nerd shit#dm me anytime to talk book recs <3#seven and a half lessons about the brain#7 1/2 lessons about the brain#dr. lisa feldman barrett#psychology#neuroscience

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The thing that people with power don’t know is what it’s like to have little or no power. Minute by minute, you are reminded of your place in the world: how it’s difficult to get out of bed if you have mental health conditions, impossible to laugh or charm if you are worried about what you will eat, and how not being seen can grind away at your sense of self.

I am often in rooms with people who do not understand this, people more educated than me, more privileged than me – people who are so accustomed to having power that they don’t even know it’s there. I am a black woman in my fifties, I am neurodiverse, and I have multiple mental health diagnoses. Part of my job as a researcher and cultural thinker involves working with leaders in the arts, business and politics, supporting them to see the one thing they can’t: the effects of the power that they wield.

But just pointing out this disparity can leave people feeling defensive. It can get you labelled an “angry black woman”. In the past, when I started to tell people about what it felt like to have no power, and how hard it was to understand, they didn’t listen. So I turned to science, to understand the effects of power in your body, in order to bring evidence to what I already knew, and make people listen.

I call this research the neurology of power. It involves looking at the sociological explanations of power as well as the neuroscientific underpinnings. Being in a state of powerlessness leads to perpetual stress. That stress trains our bodies to be on the alert for it, compromising our productivity and happiness in situations where others – those who have never experienced that sense of powerlessness – are left to thrive.

Anyone who’s ever taken a few deep breaths, forced themselves to lower their shoulders or closed their eyes to regain their composure is aware that the brain and the body are in a constant feedback loop. We feel our thoughts and we think our feelings.

Researching these ideas brought me into conversations with leading scientists around the world. Prof Lisa Feldman Barrett, at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts general hospital, told me about a process known as “body budgeting”, or allostasis. She argues that, like a financial budget, our brains keep track of when we spend resources (eg going for a run) and when resources are deposited (eg eating). It is a predictive process, by which the brain maintains energy regulation by anticipating the body’s needs and preparing to satisfy those needs before they arise.

Feldman argues that this process is so fundamental to the architecture of the brain that it extends to our mental states. Our emotions arise from our brain’s calculations of the physical, metabolic needs of our bodies. Predicting a dangerous situation requiring us to flee results in physical changes and discomfort we register as anxiety.

This body budgeting has social effects. For instance, our ability to empathise with another person is dependent on our body budgeting. When people are more familiar to us, our brain can more efficiently predict what their inner state and struggles may be and feel like. This process is harder for those less familiar to us, so our brains may be less inclined to use up precious resources in making difficult predictions.

Sukhvinder Obhi, a professor of social neuroscience at McMaster University in Canada, told me more about how people with power often struggle to empathise with others. Because the brain makes predictions based on past experiences, these patterns are self-reinforcing. Often, powerful people learn to behave as if they have power. Powerless people learn to behave as if they have none.

This research legitimised what I always knew. Power wires the powerful for power; but it can also wire them against people without power. You can lose your empathy. And power is critical for wellbeing.

This empathy deficit has historically been a celebrated attribute among leaders – ruthlessness that allows people to make hard decisions without fear of the consequences. You can see it in political leaders of every political persuasion, from time immemorial. Today it feels particularly stark. It has left society divided, trust in powerful institutions eroded and policymaking driven by ideology rather than human experience.

We need a new kind of policymaking that puts people at the heart of the process. Policymakers need to start by listening, by sharing power with the people who really understand the nature of powerlessness and the effect of the policies they are writing. We can’t stay in this perpetual loop of those with power deciding everything. They are handicapped by their own privilege.

Many find this evidence about power uncomfortable to confront. I’ve spoken on panels, presented my arguments and had them disputed in public by senior academics, who later apologised privately, once they’d checked my references in full.

I shouldn’t need to lean on science to be heard and justify what I already know: that power is a limiting factor for our leaders and we need to make policy differently to counterbalance the power gap. This is a call to action: we can do things differently. Let’s try.

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

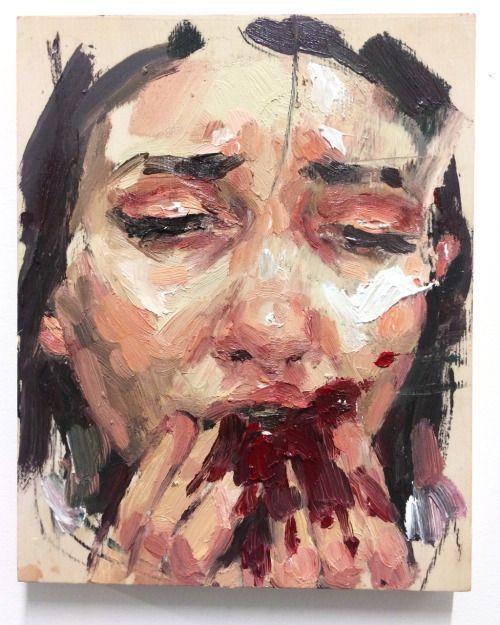

Hanif Abdurraqib, They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill Us

Glennon Doyle, Untamed

Elly Smallwood, Saturn

Meggie Royer, The No You Never Listened To

Volker Hermes, Hidden Duvivier

Athena Nassar, Love Is Not Always Song, but the Swelling

Siobhan Scherezade, Code

Eva Gonzalès, La Toalette

David Levithan, How They Met and Other Stories

Mark Wolynn, It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle

Lisa Feldman Barrett, How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain

Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility

The Mountain Goats, Up The Wolves x Jordi Garriga Mora, Minotauro

Kaveh Akbar, Calling A Wolf A Wolf

22 notes

·

View notes

Link

Abstract

Your brain keeps you alive and well by running a metabolic “budget” for your body. Our authors, who co-direct the Interdisciplinary Affective Science Laboratory at Northeastern University and Massachusetts General Hospital, explain how these budgetary activities, and the sensations they create inside your body, suggest surprising connections between brain, mind, body, and world.

Right now, as you read this text, it may seem like your eyes are simply detecting words out there in the world. But you’re not detecting—you’re constructing. In every moment, outside of your awareness, your brain constructs a model of the outside world, transforming light waves, pressure changes, and chemicals into sights, sounds, touches, smells, and tastes. Your brain continually anticipates what will happen next around you, checks its predictions against sense data streaming in from your eyes, ears, and other sensory surfaces of your body, updates the model as needed, and in doing so creates your experience of the world. This covert construction of your senses is called exteroception.

Your brain also models the events occurring inside your body. In much the same way that your brain sees sights, feels things that touch your skin, and hears sounds, it also produces your body’s inner sensations, such as a gurgling stomach, a tightness in your chest, and even the beating of your heart. Your brain also models other sensations from movements that you cannot feel, such as your liver cleaning your blood. The construction of all your inner sensations is called interoception and, like exteroception, it proceeds completely outside your awareness.

For a long time, scientists treated interoception and exteroception as completely separate domains of sensation, bounded by your skin. But recent research has revealed that the two might not be as separate as they seem, and their boundary is fuzzy. Perhaps more importantly, the science of interoception reveals some surprising insights about how your brain works and may be a key to better understanding health and illness.

Your Brain Runs a Budget for Your Body

You live in a complex body. With over 600 muscles in motion and dozens of internal organs, your body pumps 2,000 gallons of blood per day, balances dozens of hormones and other chemicals, regulates the energy of billions of neurons, digests food, excretes waste, and fights illness—all of it nonstop throughout your life. Your brain’s most important job is to coordinate and control the systems of your body as they burn and replenish energy efficiently. Your brain ensures that the right amounts of salt, glucose, water, and other vital resources are available where and when they’re needed, so you can walk, think, learn, innovate, and love. This constant budgeting of your body’s needs is called allostasis.

Allostasis is a predictive balancing act. Your brain moves your body through a massively complex world full of other brains-in-bodies, so it must constantly guess which of your cells need what resources… and guess well. If your heart rate is too fast or slow for the physical demands you face, or your lungs don’t process sufficient oxygen, or your cells become insensitive to the glucose that ultimately powers your muscles, you’re not likely to live long. So, your brain is engaged in the constant body-budgeting of allostasis, anticipating your body’s needs at every moment while deciding which efforts are worth the metabolic investment. Right now, for example, your brain is using some glucose and other metabolic resources to read these words. Learning and moving your body are some of your brain’s most costly operations, metabolically speaking.

Efficient energy regulation, therefore, is a major selection pressure for all living things. Animals live longer and suffer from fewer diseases when their tissues, organs, and systems receive the right nutrients just when they are needed. Such animals are more fit to reproduce. They can explore further for food and better protect themselves from predators, learning all the while and honing their models of the world. The more effectively and efficiently a brain can invest its energy, therefore, the greater the metabolic return.

Go to:

Sensing the World Around You

Reading this text depends on seeing, which is one form of exteroception. To perform this activity, your brain makes metabolic investments to model the world outside your body. It directs your eye muscles to contract and relax in a pattern that allows your eyes to sweep across a line of text—at each moment predicting what you will see next, based on past experience (see Figure 1). Your brain then directs your eyes to stop and fixate briefly to compare its predictions to the visual data arising from the page. It makes any necessary corrections and then directs the next volley of eye movements.

Vision, like other forms of exteroception, operates in the service of movement. Think about it: How do you know how far away to hold this page, so the article is legible? How do you even know where your limbs are in space? How do you manage not to bump into things when you walk, successfully guide your spoon to your mouth, or pick up a cup with the right amount of force? It’s all about sensation and its intimate ties to allostasis. Your brain sees, hears, feels physical contact, and constructs other sensations not because these activities are intrinsically fun or valuable, but because sensations are the means by which your brain controls your body’s many moving parts. Your movements give your brain the sense data to build its model of the world, and this model guides your actions, ultimately supporting allostasis so you survive, and even thrive, in the world around you.

Exteroception works mostly by prediction. Your brain issues motor commands, say, to move the muscles of your head, eyes, and other body parts (even before you’re aware) and simultaneously predicts the sensations likely to result from those movements. When the actual sense data arrives from the sensory surfaces in your eyes, skin, and other sense organs, your brain integrates the data to confirm or correct the predictions to refine or adjust the motor movements. In constructing your sensations, your brain estimates the state of the world in order to control and coordinate your body’s movements.

Go to:

Sensing the World Inside You

The muscles attached to your skeleton are not the only moving parts of your body. As you read this article, your brain is conducting a mostly silent symphony of movement inside your body, involving your organs, autonomic nervous system, endocrine system, and immune system. Your lungs continually expand and contract to take in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide as your heart beats to pulse blood throughout your body and brain. If what you’re reading seems interesting or unexpected, your heart rate and respiration may slow.

Many other things that you might not think of as movements are indeed movements of a sort. For example, the flow of your saliva to aid digestion; the surge of chemicals that create inflammation; and the gush of cortisol from your adrenal glands. (Cortisol has been called a stress hormone, but it is more correct to call it a metabolic hormone; it gets glucose into your bloodstream quickly when your brain predicts your body will need it.) Even conversations between the cells of your intestine and the bacteria that reside there are considered motor movements; this constant chatting aids digestion, and over time can even adjust the length of your intestine to regulate how quickly you digest!

Interoception, like exteroception, operates in the service of movement predictively. Here’s the gist: Your brain issues motor commands that adjust the insides of your body, and it simultaneously predicts the sensory consequences of those movements. At the same time, the sensory surfaces inside your body, including dozens of cells that monitor pressure changes, temperature, contractions, stretches, nutrients, gases, toxins, and various chemicals, send a steady stream of sensory signals back to your brain via electrical impulses in your spinal cord and swirling chemicals in your blood. Your brain integrates these sensory signals to confirm or correct the predictions and adjust its predicted movements, if necessary, thereby maintaining allostasis efficiently. In this way, your brain anticipates the needs of your body and proactively coordinates the internal movements that deliver glucose, water, salt, oxygen, and other resources to an infinite amount of cells just in time.

For example, think of the last time you were thirsty and drank a glass of water. Within seconds after draining the last drops, you probably felt less thirsty. This event might seem ordinary, but the water actually takes about 20 minutes to reach your bloodstream, so it can’t possibly quench your thirst in a few seconds. What relieved your thirst? Prediction. As your brain plans and executes the actions that allow you to swallow, it simultaneously anticipates the interoceptive consequences of gulping water, causing you to feel less thirsty long before your brain learns from the body about your increased hydration.

Go to:

New Insights and Deep Implications

There is still much to learn about the mechanisms of interoception and what they mean for health, illness, and basic mental functions. Exteroceptive senses such as vision are relatively better understood—perhaps because scientists are often guided by their experiences, and we don’t experience most interoceptive activity. Nevertheless, creative research by those who do study interoception has brought forth some intriguing insights. New ideas are transforming our most basic understanding of brains and bodies and challenging our most basic assumptions of how they work together to create the mind, control actions, and cause illness. We’ll share three such insights that blur three fundamental boundaries: what is inside versus outside the body, what is mental versus physical illness, and what distinguishes different mental phenomena.

MORE >>>

Interoception: The Secret Ingredient :: Lisa Feldman Barrett, Ph.D. and Karen S. Quigley, Ph.D.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Om recht te doen aan die complexiteit, hebben we méér woorden nodig. De Amerikaanse psycholoog en neurowetenschapper Lisa Feldman Barrett (een van de meest geciteerde onderzoekers in haar werkveld) ontdekte dat mensen met een grote emotionele woordenschat mentaal gezonder zijn. In het boek How Emotions Are Made (2017) laat Feldman Barrett zien hoe taal onze emotionele ervaring vormt. Als je naast ‘angstig’ ook gevoelens als ‘zenuwachtig’, ‘verlegen’ en ‘opgewonden’ kunt herkennen en benoemen, ervaar je minder angst. Een groter vocabulaire stelt je in staat meer variatie te ervaren en verschillende verhalen over je ervaring te onderzoeken. Dat maakt mentaal flexibel.

De mentale gezondheidscrisis, zou je kunnen zeggen, is mede een taalcrisis. Door de alomtegenwoordigheid van therapietaal op platforms als TikTok, in combinatie met lange wachtlijsten voor echte therapie, verschraalt de woordenschat waarmee jongeren zichzelf kunnen begrijpen. Dat werkt mentale inflexibiliteit in de hand. In het ergste geval verandert overhaaste zelfdiagnose mentaal ongemak in een specifieke, door TikTok geïnspireerde stoornis.

#readings#nederlands#laatste alinea vind ik zelf een zwaktebod#categorie Ja Eens ik snap denk ik wat je bedoelt maar het had 400 woorden extra nodig om niet vervelend te klinken

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEST OF 2022

Read:

Incarnadine, the Bloody Red of Fashionable Cosmetics and Shakespearean Poetics

Psychology, Misinformation, and the Public Square

Everyone Is Beautiful and No One Is Horny

agency/satisfaction

Actually, Let’s Not Be in the Moment

Do Brain Implants Change Your Identity?

Adam Savage on Lists, More Lists, and the Power of Checkboxes

Our Pseudonymous Selves

The skincare con

consistency is proficiency

Hundreds of Ways to Get S#!+ Done - and We Still Don’t

The digital death of collecting

The Mundanity of Excellence

Icons: Eli Keszler in Conversation with Adam Curtis

modern malaise

The Dangerous Populist Science of Yuval Noah Harari

Is There Such A Thing As Good Taste?

The Odor of Things

What It Takes To Put Our Phone Away

Personal Style Is Dead And The Algorithm Killed It

The Philosopher of Feelings

Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit

Expert by Roger Kneebone

Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe

The Act of Living by Frank Tallis

Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain by Lisa Feldman Barrett

The Joy of Science by Jim Al-Khalili

The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? by Michael J. Sandel

Sedated: How Modern Capitalism Created Our Mental Health Crisis by James Davies

Watched:

Literary Rendezvous at Rue Cambon: Girl.

In the library of Charlotte Casiraghi

Brave New World vs Nineteen Eighty-Four featuring Adam Gopnik and Will Self

Peaky Blinders (S6)

Killing Eve (S4)

The Decade the Rich Won

Everything Everywhere All At Once

Severance

Listened To:

Alt J’s The Dream

Beyonce’s Renaissance

Went To:

Swan Lake @ Royal Opera House

Fabergé in London: Romance to Revolution @ the V&A

Ancient Greeks: Science and Wisdom @ the Science Museum

Vision & Virtuosity by Tiffany & Co. @ Saatchi Gallery

Henry Marsh in conversation with Will Self

Feminine power: the divine to the demonic @ The British Museum

#I've been making these 'consumption' lists for over 2 years now (!) but I've never done a yearly best of.#So I thought I'd try but I hate it already because I feel like I missed a lot.#It was collated from the other lists this year simply by reading through them and picking the ones that from title alone made me think#'I remember that clearly and I would read/watch/listen to it again'.#But it doesn't really work for 'listened to' because those lists are normally just random songs I liked each month.#Not the most scientific of methods by alas.#personal

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bibliography: books posted on this blog in 2024

Sara AHMED (2010): The Promise of Happiness

Cat BOHANNON (2023): Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution

Holly BRIDGES (2014): Reframe Your Thinking Around Autism: How the Polyvagal Theory and Brain Plasticity Help Us Make Sense of Autism

Johann CHAPOUTOT (2024): The Law of Blood: Thinking and Acting as a Nazi

Caroline CRIADO-PEREZ (2019): Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men

Gavin DE BECKER (2000): Survival Signals That Protect Us from Violence

Virginie DESPENTES (2006): King Kong Theory

Annie ERNAUX (2000): Happening

Lisa FELDMAN BARRETT (2017): How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain

Shaun GALLAGHER (2012): Phenomenology

David GRAEBER (2015): The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy

Sarah HENDRICKX (2015): Women and Girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Understanding Life Experiences from Early Childhood to Old Age

Sarah HILL (2019): This Is Your Brain on Birth Control: The Surprising Science of Women, Hormones, and the Law of Unintended Consequences

Luke JENNINGS (2017): Killing Eve: Codename Villanelle

Bernardo KASTRUP (2021): Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics: The Archetypal Semantics of an Experiential Universe

Roman KOTOV, Thomas JOINER, Norman SCHMIDT (2004): Taxometrics: Toward a new diagnostic scheme for psychopathology

Benjamin LIPSCOMB (2021): The Women are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics

Dorian LYNSKEY (2024): Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About The End of the World

Kate MANNE (2024): Unshrinking: How to Fight Fatphobia

Mario MIKULINCER (1994): Human Learned Helplessness: A Coping Perspective

Jenara NERENBERG (2020): Divergent Mind: Thriving in a World That Wasn’t Designed for

Lucy NEVILLE (2018): Girls Who Like Boys Who Like Boys: Women and Gay Male Pornography and Erotica

Peggy ORNSTEIN (2020): Boys & Sex: Young Men on Hookups, Love, Porn, Consent, and Navigating the New Masculinity

Lucile PEYTAVIN (2021): Le coût de la virilité

Lynn PHILLIPS (2000): Flirting with Danger: Young Women’s Reflections on Sexuality and Domination

Stephen PORGES (2017): The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe

Joëlle PROUST (2013): The Philosophy of Metacognition: Mental Agency and Self-Awareness

John SARLO: The Mindbody Prescription: Healing the Body, Healing the Pain

Jessica TAYLOR (2022): Sexy But Psycho: How the Patriarchy Uses Women’s Trauma Against Them

Manos TSAKIRIS and Helena DE PREESTER (2018): The Interoceptive Mind: From Homeostasis to Awareness

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books about game design but not really but really

Collecting my suggestions & others' from a twitter thread (remember those?)

Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino

Pilgrim in the Microworld, David Sudnow

Breathing Machines, Leigh Alexander

Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Gabriel Garcia Marquez

Einstein’s Dreams, Alan Lightman

An Inventory of Losses, Judith Schalansky

Visit to a Small Planet, Elinor Fuchs (https://web.mit.edu/jscheib/Public/foundations_06/ef_smallplanet.pdf)

Noises Off, Michael Freyn

Influence, Robert Cialdini

Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges

Wonderbook, Jeff VanderMeer

Pale Fire, Vladimir Nabokov

The Westing Game, Ellen Raskin

Motel of the Mysteries, David Macaulay

Ghost Stories for Darwin, Banu Subramaniam (esp. “Singing the Morning Glory Blues”)

Batman: The Animated Series Writer’s Bible (https://dcanimated.com/WF/batman/btas/backstage/wbible/)

Dictionary of the Khazars, Milorad Pavić

The Passion, Jeannette Winterson

Rainbows End, Vernon Vinge

Cat’s Cradle, Kurt Vonnegut

Between the Acts, Virginia Woolf

Where Did You Go? Out. What Did You Do? Nothing., Robert Paul Smith

A Telling of the Tales, William J. Brooke

Finishing The Hat & Look, I Made A Hat, Stephen Sondheim

Finite and Infinite Games, James P. Cause

Exercises in Style, Raymond Queneau

The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman

Life: A User's Manual, Georges Perec

The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood, James Gleick

7 1/2 Lessons About The Brain, Lisa Feldman Barrett

additions:

Microserfs, Douglas Coupland

The Eyes of the Skin, Juhani Pallasmaa

House of Leaves, Mark Z. Danielewski

Piranesi, Susanna Clarke

13 notes

·

View notes