#mükrime

Text

Sultan Mehmed II X Emine Gülbahar Mükrime Hatun

In January 1448 a son was born to Mehmed Çelebi in Thracian Dimotika, by a slave girl named Gülbahar. The boy was given the name of Bayezid and was later (1481) to mount the Ottoman throne as the second sultan of this name.

There is no doubt that this union was beneath Mehmed's station: Gülbahar bint Abdullah, whom Turkish legend sub- sequently transformed into a "daughter of the king of France," was a Christian slave of Albanian origin.

It is equally certain, as we shall see later on, that Mehmed preserved a particular affection for her as long as he lived. From the fact that Gülbahar Hatun bore her child in Dimotika, it may be inferred that Mehmed was back in Europe by the beginning of 1448 at the latest and perhaps even that he was residing there. Dimotika was the site of an old Byzantine castle, with a double ring of walls, preserved by the sultans and sometimes used for the Ottoman state treasury.

Babinger, F. (1978). Mehmed the conqueror and his time. Princeton University Press.

P.s. She also bore him a daughter named Geverhan Sultan.

#sultan mehmed ii#Emine Gülbahar Mükrime Hatun#gulbahar hatun#rise of empires: ottoman#ottoman empire#turkish history#history#european history#Dimotika#Geverhan Sultan#albanian#ottoman women#ottoman culture#slave girl

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emine Gülbahar Mükrime Hatun (گل بھار مکرمه خاتون; "benign", "spring rose" and "hospitable"; died c. 1492), was consort of Sultan Mehmed II, and mother of Sultan Bayezid II.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝑂𝑡𝑡𝑜𝑚𝑎𝑛 𝐷𝑦𝑛𝑎𝑠𝑡𝑦 𝐻𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑜𝑟𝑦 𝐴𝑝𝑝𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑖𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑀𝑜𝑛𝑡ℎ:

𝑊𝑒𝑒𝑘 2: 𝐻𝑎𝑠𝑒𝑘𝑖 𝑆𝑢𝑙𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑠/𝐿𝑒𝑔𝑎𝑙 𝑊𝑖𝑓𝑒𝑠

𝐷𝑎𝑦 13: 𝐺𝑢𝑙𝑏𝑎𝑟ℎ𝑎𝑟 𝐻𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑛, 𝐸𝑚𝑖𝑛𝑒 𝐺𝑢𝑙𝑏𝑎ℎ𝑎𝑟 𝑀𝑢𝑘𝑟𝑖𝑚𝑒 𝐻𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑛

#gülbahar hatun#emine gülbahar mükrime hatun#fetih 1453#the conquest 1453#ottoman dynasty history appreciation month:week 2

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mehmed II Conqueror + consorts (pictures are for aesthetic)

Emine Gülbahar Hatun — was a favourite consort of Sultan Mehmed II. In most sources she is referred as non-muslim slave who was converted to Islam after her arrival to the harem. There is no agreement on her origins some historians think she was Pontic Greek, Albanian or lowly Slavic. She was the mother of the future Sultan Bayezid II and Gevherhan Hatun. She died circa 1492 and was buried in her mausoleum inside the Fatih Mosque next to her late husband.

Çiçek Yagmur Hatun — was a wife or consort of Sultan Mehmed II. According to some sources she could have been Turkish noblewoman or Serbian, Greek, Venetian, French slave. She entered the harem or married Mehmed at Constantinople and gave birth to her only son Şehzade Cem (Ottoman claimant Sultan) on 22 December 1459. It is not known the degree of influence she had during Mehmed’s reign or if she even was favoured by him. She died on 3 May 1498 of plague and was buried in Cairo.

Hatice Hatun — was a thrid legal wife of Sultan Mehmed II. She was a possible daughter of Zaganos Mehmed Pasha. In 1463 she became Mehmed's third legal wife. After her husband death she remarried with a statesman.

Sitti Mükrime Hatun — was a Turkish Princess and first legal wife of Sultan Mehmed II. Her father was Süleyman Bey the sixth ruler of Dulkadir State. When Mehmed turned seventeen he married her for political purposes. Her possible offspring is unknown. Due to her middle name Sittişah is sometimes confused with Gülbahar Mükrime Hatun another consort of Mehmed. She died in September 1486 and was buried in a mausoleum built inside her mosque.

Helena Palaiologina — was a possible wife of Sultan Mehmed II. Her entering the Sultan's harem is controversial and remain unconfirmed. She was a daughter of the Despot of Morea Demetrios Paleologos the brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos the final Byzantine emperor and Theodora Asanina the daughter of Paul Asan. Some rumors says Mehmed II asked for her after his campaign in Morea having heard of her beauty. Probably he never bedded with her because he was afraid she would poison him. In another case Helena was provided with a pension and large estate at Adrianople by the Sultan though she was forbidden to marry. She died of unknown causes in 1469 or 1470 in Edirne.

Gülşah Hatun — was a second legal wife or consort of Sultan Mehmed II. There is no informations about her origins. She married Mehmed or entered his harem in 1449 when he was still a Prince and the governor of Manisa. Shortly before Murad’s II death she gave a birth to her only son Şehzade Mustafa and followed him to Konya when he became governor of the province. She died circa 1487 and was buried in Bursa in the tomb she had built for herself near that of Mustafa.

Maria Hatun — was a consort of Sultan Mehmed II. Before she entered Mehmed’s harem she was a widow of Alexander Komnenos Asen. According to some sources she was judicated as the most beautiful woman of her age. Some historians claims she could be more likely Murad’s II concubine than Mehmed’s.

Anna Hatun — was a consort of Sultan Mehmed II. Her parents were Trabzon Greek emperor David Komnenos and Helena Kantakuzenos. The marriage was initially proposed by her father, but Mehmed refused. Nontheless when Trabzon was taken in 1461 Anna entered the harem and stayed there for two years after which Mehmed married her off to Zaganos Mehmed Pasha.

#ottoman history#mehmed ii#consort#gulbahar hatun#cicek hatun#helena hatun#hatice hatun#maria hatun#sitti hatun#anna hatun#ottoman empire#aestehtic#history#historyedit#sultanate#wives#myedit#ottoman ladies

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

》 Mükrime Hatun 《

(In some sources, it is written as Mükerrem and Muharrem.)

Real name: Hüma

Date and place of birth : 1494 / Shkodër

Date of death and place: 05.09.1555 Edirne

Father: Skanderbeg (formerly / Prince Stephan Stanisha Chirnoevich)

Mother: Albanian Princess (probably Princess Arianiti)

Origin: Montenegro Royal family Chirnoyevich (Chernoyevich) dynasty

Spouse: 1 Süleyman

Marriage date : 12.1508 / Şebinkarahisar

Children: Şehzade Bayezid

Meryem Sultan

Neslihan Sultan

Şehzade Murad

Mükrime Hatun lived in Edirne Palace since 1534. And after 1545, he lived in his own palace in Edirne.

◇ Photo is representative.◇

#magnificent century#muhteşem yüzyıl#mukrime hatun#ottoman empire#ottoman history#sultans#sultan süleyman#sultan suleyman#suleiman the magnificent

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Family of Mehed II.

#mehmed ii#gülbahar hatun#gülbahar#gulbahar#sitti mükrime hatun#sitti mükrime#mükrime#sitti#sitti mukrime hatun#çiçek hatun#çiçek#cicek hatun#gülşah hatun#gülşah#gulsah#gulshah#anna hatun#helena hatun#hatice hatun#gevherhan hatun#gevherhan#bayezid ii#mustafa#cem#sultan cem

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is it true that between Mehmet II. and Süleyman I. no sultan had a consort in a classical sense (that is, a lawful wedded wife)? And what do you make of the claims that Selim I. and/or one of his brothers married a princess from Crimea?

Yes, it is true. One of Bayezid II's consorts was allegedly the niece of Sitti Mükrime Hâtûn, but her identity is not confirmed.

The story goes like this: Şehzade Mehmed, one of Bayezid II's sons, married this Crimean Princess - whom Alderson names Ayşe - but when he died, Selim I married her instead. Uluçay doesn't believe that this actually happened:

Alderson wrote that he [Selim I] had four wives, three of whom were named Ayşe, Hafsa, and Taçlı Hatun. He claimed that the last one's name was unknown. Even if he wrote that Ayşe was the daughter of the Crimean Khan, that she was married to Mehmed, Bayezid II's son, and that Selim married her upon Mehmed's death at a young age, it is not true. Because we know that during the reigns of Bayezid II and Selim I, Mehmed's mother and wife were paid and stayed in the Old Palace. — M. Çağatay Uluçay, Padişahların Kadınları ve Kızları

He goes on saying that on Hafsa Sultan's endowment deed for her pious foundation, she's called Ayşe so Ayşe and Hafsa are the same person after all.

Moreover, when Süleyman married Hürrem, it created such a scandal because it was perceived by everyone - Ottomans and foreigners - that sultans did not get married. This kind of proves that the last official marriage had been so in the past that nobody remembered it.

It could be that Şehzade Mehmed married the daughter of the Crimean Khan after all, but as he never succeeded his father on the throne, it is not an official marriage between a sultan and a foreign princess.

#anon#ask post#ask: ottoman history#selim i#bayezid ii#ayse hafsa sultan#ayse hatun#minetteskvareninova

14 notes

·

View notes

Link

Grup Başkanvekili Mahir Ünal, Kahramanmaraş’ın Elbistan ilçesinde Yatırım Değerlendirme Toplantısı’na katıldı. Ünal, Elbistan Belediyesi Mükrime Hatun Kültür Evi’nde gerçekleştirilen toplantıda yaptığı konuşmada, salgın dönemi öncesi her yıl...

0 notes

Text

Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan pdf indir

Fatih Sultan Mehmed, en önemli sultanlarından biridir Osmanlının; İstanbul’u almasıyla da ister Müslüman ister Hıristiyan tüm dünyanın öne çıkan önemli şahsiyetlerinden biri olarak tarihe de taht kurmuştur. Onun tahta çıkması, sanat ve bilimle olan ilgisi, dehası hep söz konusu edilmiş ve bu konuların her birinde gösterdiği sıra dışı konumlanışıyla da kendisinden söz ettirmiş bir sultandır, tarihsel kişiliktir.

Murat Aykaç Erginöz daha farklı, henüz yaygın bir biçimde tanınmayan eşlerinden birini, Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan’ı oyunun temel karakteri olarak ele alıyor. Bu karakterin çevresinde tüm tarihsel bilgileri işlerken, zamanın önemli kişilerinden evliliklerine, taht kavgalarına ve harem yaşamına kadar geniş bir alana uzanan bir eser çıkıyor ortaya: Fatih’in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan.

Oyunun kitap olarak basımı için yazılan önsözde de konu bilimsel olarak, değişik tarihçilerin gözünden son derece öğretici bir biçimde aktarılıyor. Sahnelendiğinde önemli bir ilgi göreceği kuşkusuz olan bu oyun, kitap olarak da son derce keyifle okunup, tarihsel bazı bilgileri de aktarırken öğretici bir nitelik de taşıyacaktır.

Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan pdf indir oku

#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan E-Book İndir#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan ebook indir#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan ebook oku#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan epub#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan epub indir oku#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan kitabı pdf indir#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan online pdf oku#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan PDF İndir#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan PDF Oku#Fatih'in Eşi Elbistanlı Mükrime Sitti Şah Sultan ücretsiz indir oku#Ekitap

0 notes

Text

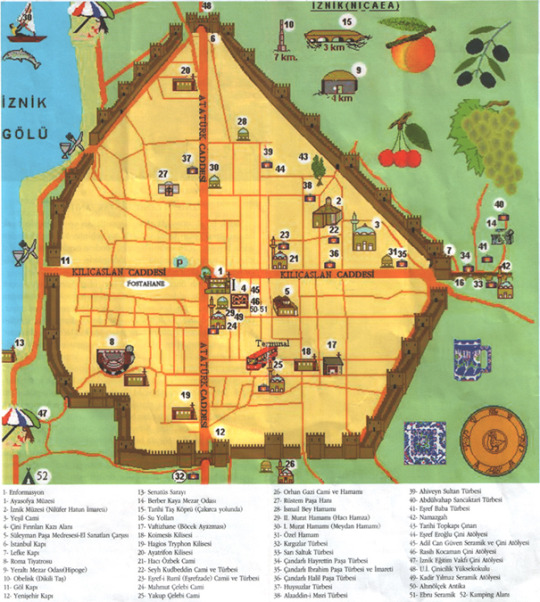

İZNİK

İznik İlçesi; Tarihte birçok medeniyete ev sahipliği yapmış, Dünyada eşine az rastlanan ve bütünüyle açık hava müzesi olan tarih ve antik bir şehirdir.

Nasıl Gidilir?

Eskihisar Topculardan arabalı vapura binilir Yalova’ya gelinir. Ardından Bursa yönüne doğru giderken Orhangazi şehir merkezindeki ışıklardan sola İznik istikametine sapılır. Yaklaşık 40 kilometrelik güzergâhı takip ederek Boyalıca ve Çakırca köylerini geçtikten sonra İznik’e gelebilirsiniz.

Hakkında?

İznik; Bursa iline bağlıdır.

Osmanlı döneminde Türk çini ve seramiği ile özdeşleşmiş bir isimdir.

Şarap tanrısı Dionysos’un kentidir İznik.

Geçmişten günümüze barışın simgesi olan zeytin ağaçları, göz alabildiğine uzanan yeşil ile çevrili İznik Gölü, muhteşem çinileri, yüzyıllara meydan okuyan tarihi eserleri, her yanından rengarenk çiçekler fışkıran toprak yolları, meyve ağaçlarının süslediği bahçeli şirin evleri ile masalın ta kendisidir İznik.

Yaz kış demeden adeta bereket saçan verimli toğrağı, kendine özgü iklimi ve doğal güzelliği nedeniyle, tarihin her döneminde insanlığın ilgi odaklarından biri haline gelmiş.

İstanbul Kapı, Yenişehir Kapı, Lefke Kapı ve Göl Kapı olarak şehrin 4 adet giriş kapısı mevcut. Şehir beşkenarlı 5000 kilometrelik surlarla çevrilidir. Dört ana kapı, zafer takı gibi gösterişlidir ve üçü halen ayaktadır. Lefke Kapı’da mermer friz parçalarının kullanıldığı görülmektedir. İstanbul Kapı Konstantinapolis’e açıldığından en gösterişli kapıdır. Yenişehir Kapı kısmen ayaktadır. Göl Kapı ise tamamen yıkılmıştır.

Romalılar Nicea adını verdikleri bu şehri korumak için büyük uğraş verdiler. Çeşitli saldırılara uğrayan Nicea’yı bu savaş akınlarından koruyabilmek için, Bithynia Krallığı, zamanında başlatılan ancak depremlerle hasar gören surları, daha güçlü olarak inşa ettiler. Sur duvarları her medeniyetin taş ustalığını sergiler.

İznik, her avuç toprağı binlerce yıldır kültür kalıntıları ile yoğrulmuş, bölgede, yüzyıllar boyu tarih sayfalarının baş köşelerinde yerini almış bir kenttir. Dört imparatorluğa başkentlik yapmış nadir yerleşimlerden biridir. Bitinya, Bizans, Selcuklu, Osmanlı imparatorluklarının başkenti olmuştur.

İznik'te M.Ö 2500 yıllarından itibaren uygarlıkların varolduğu bilinmektedir. M.Ö 316'da Makadeona İmparatoru İskender'in komutanı Antigonos tarafından yenilenen ve Antigoneia adını alan kent; Antigonos'un Lysimakhos'a yenilmesiden sonra muzaffer komutanın eşi Nikaia'nın adını almıştır. M.Ö 293'te Bitinya krallığına katılmış, bu dönemde önemli mimari eserlerle donatılmış ve bir süre de krallığın başkenti olmuştur. Daha sonra önemli bir Roma yerleşim birimi olarak varlığını sürdürmüştür. İznik, 325 yılında Hristiyanlık açısından çok önemli bir olay olan I. Konsül toplantısına ev sahipliği yapmıştır. Bu toplantıda Hz. İsa'nın tanrıdan dünyaya gelmediği tezine karşılık, tanrının oğlu olduğu görüşü baskın çıkmış, hristiyanlık ile ilgili yortu günleri ve 20 maddelik Nikeia Kanunları kabul edilmiştir. 787'de toplanan VII. Konsül de İznik'te gerçekleşmiş ve bu konsülde resim ve heykel üzerindeki yasakları kaldırmıştır.

Bizans ve Selçuk'a da başkentlik yaptıktan sonra 1331'de Orhan Gazi tarafından Osmanlı topraklarına katılmış; sanat, ticaret ve kültür merkezi haline gelmiştir. 14, 15, 16. yy'larda dünyaca ünlü İznik çinilerinin üretimi gerçekleşmiştir.,

Ayasofya Cami

Ayasofya Cami'si bu muhteşem yapı ülkemizdeki üç Ayasofya'dan biridir. İznik meydanda bulunan bu yapı Orhan Gazi'nin fethinden sonra 1331 yılında camiye çevrilmiştir. Şehir alındığında klise olarak kullanılan yapı Orhan Gazi tarafından camiye çevrildiği için Orhan Camii adıyla anılmaktadır. Ayasofya Kilisesi, Ayasofya Müzesi ve Orhan Camii olarak dünyada üç isimli tek yer olma özelliğini taşımaktadır. Hristiyanlık dini için oldukça önemli olan bu yapı İznik konsiline ev sahipliği yapmıştır.

Osmanlı İmparatorluğunun 2. padişahı Orhangazi, İznik’i kansız bir şekilde fethettikten hemen sonra İznik Ayasofya’yı Cami’ye çeviriyor ve adı Orhan Camii oluyor. 200 küsur yıl sonra meydana gelen depremde hasar gören yapıya, Mimar Sinan minare ve mihrabı ekliyor. Kurtuluş savaşı sıralarında da yapı yakılıp yıkılıyor ve uzun yıllar harabe şeklinde kaderine terk ediliyor. Kısaca İznik Ayasofya ortalama 850 yıl kilise, yine ortalama 600 yılda camii olarak kullanıldı.

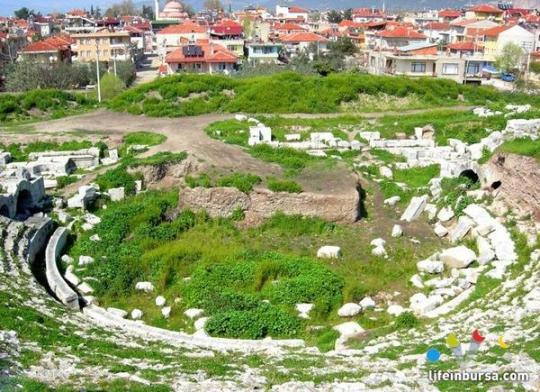

İznik Roma Tiyatrosu

İznik Gölü kıyısında, 2. yüzyıla ait Roma Tiyatrosu, 15. 000 kişi kapasitelidir. Antik tiyatronun, seyircilerin oturduğu kısım ile hayvanların arenaya salındığı tünel kısmı büyük ölçüde ayaktadır. Anadolu’da görebileceğimiz ayakta kalmış en görkemli arkeolojik yapılarından biridir.

Açılış Zamanı: 08:00 – 17:00

İstanbul Kapı

İstanbul Kapısı, Hadrianus zamanında, (Milattan Sonra) 70-71 yıllarında inşa edilmiş, Bursa'nın tarihi bir kalesidir.

İstanbul Kapısı, Roma ve Bizans dönemlerinde İstanbul'a giden yolun buradan başlamasından ötürü İstanbul Kapı ismi ile anılmıştır. Bithynia ve Pontus eyaletlerinde prokonsillük yapmıştır. Ayrıca iç kapının kuzeybatı yüzeyinden kazınmış bir büst kabartmasının da Büyük İskender´e ait olduğu belirtilmektedir.

Lefke Kapı

Lefke Kapısı veya tarihî adıyla Şam Kapısı, İmparator Hadrianus zamanında yapılan, İznik’in doğusunda, Kılıçarslan Caddesi´nin sonundadır.

Çini Fırınları

Çini Fırınlarının kazısı tarihimizde ilk olarak 1963 yılında başlanmış, ”Milet İşi, Şam İşi, Haliç İşi, Rodos İşi gibi isimlerle tanımlanmaya çalışan Osmanlı seramik ve çinilerinin” asıl ve önemli üretim merkezinin İznik olduğu, yapılan kazılar sonucu elde edilen fırın kalıntıları, pişirim malzemeleri, yarı mamul parçalar, deforme ve yanık parçalar sayesinde bilim çevrelerine kanıtlanmıştır. Bu çalışmalar sonucunda şimdiye kadar dört fırın kalıntısı ortaya çıkarılmış ve korunma altına alınmıştır.

Klise Kalıntıları (Kimesis, İstanbul ve Yenişehir Kapı)

Gölde kıyıdan yaklaşık 20 metre açıkta ve 2 metre derinlikte, erken Hristiyanlık mimarisinin özelliklerini taşıyan, Roma dönemine ait yaklaşık 1600 yıllık bazilika keşfedildi.

Bursa Büyükşehir Belediyesinin İznik'te başlattığı "Tarihi Kültürel Mirası Tespit ve Havadan Fotoğraflama Çalışmaları" sırasında çekilen görüntülerde tesadüfen fark edilen bazilikanın, M.S 740 depremindeki çökmenin etkisiyle göl sularına gömüldüğü tahmin ediliyor.

Bazilika; içi, ortadaki yüksek, yanlardakiler daha alçak olmak üzere iki sıra sütunla üç salona ayrılmış, dikdörtgen biçiminde büyük kilise olarak tanımlanıyor. Hristiyanlık dünyasının önemli olaylarına sahne olan İznik'te, Senato Sarayı'nda MS 325 yılında I. Konsil, M.S 787 yılında de İznik Ayasofya Kilisesi'nde 7. Konsil toplantıları yapılmıştı.

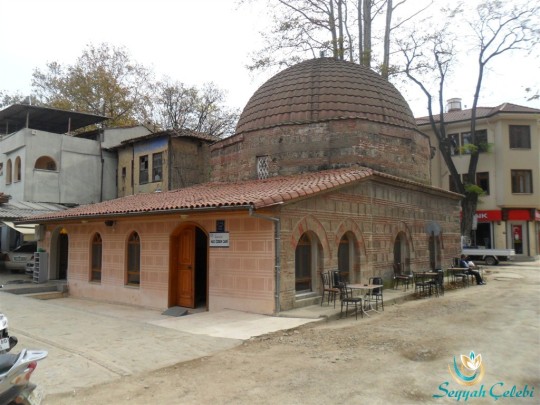

Eşrefzade Camisi ve Türbesi (Eşrefi Rumi)

II. Bayezit'in oğlu Şehinşah'ın eşi Mükrime Hatun tarafından XVI. yüzyılda yaptırılmıştır. Caminin ve türbenin duvarları Sultan IV. Murat tarafından (1640-1643) çinilerle kaplatılmıştır. Kurtuluş Savaşı sırasında Yunanlılar tarafından tamamen yıkılan cami 1950 yılında aslına benzer boyutlarda yeniden inşa edilmiştir. Eski camiye ait sadece minare ayaktadır. Minarenin külah bölümü yıkılmıştır. Çini kuşakların yer aldığı gövdesi ise çemberler İle sarılarak sağlamlaştırılmıştır. Caminin hemen yanında hazire şeklindeki türbede XV. yüzyılın büyük mutasavvıfı ve şairlerinden olan ve kendisini "gah muti gah asiyem, gah alim gah amiyem" diye tanıtan Eşref-i Rumî yatmaktadır.

İznik’in kuzeydoğusunda, Eşrefoğlu Sokak ile Türbe Sokağı’nın kesiştiği noktada yer alan Eşrefi Rumi Camisi türbe, dergâh, zaviye ve hazireden oluşan bir yapı topluluğu idi. Eşrefoğlu Abdullah Rûmi (1353-1469) aslen Mekkeli olup, Bursa’da eğitim görmüş olup, Hacı Bayram Veli’nin önce müridi, sonra da damadı olmuştur. Bundan sonra da dergâhını İznik’te kurmuş, bunun yanına da camisini yaptırmıştır.

Süleyman Paşa Medresesi

Süleyman Paşa, Orhan Gazi’ nin oğludur. 1332 yılında Süleyman Şah tarafından Süleyman Paşa Medresesi yaptırılmıştır. Süleyman Paşa Medresesi, geleneksel çini sanatını yaşatmak ve gelecek nesle ulaştırmak amacıyla restore edilerek yeniden düzenlenmiştir. “Çiniciler Çarşısı” olarak hizmet veren medresede seramik üretimi yapan dokuz sanat atölyesi bulunmakta olup, bu atölyelerde geleneksel İznik çinileri üretilmektedir. Yapı Osmanlı döneminin ilk medresesi olması sebebiyle diğer medrese yapıları arasında ayrıcalıklı bir yere sahiptir. Avlulu medreselerin de ilk örneğidir. Binada 11 hücre, bir dersane ve bunları örten 19 kubbe mevcuttur. Medrese açık avlulu ve "U" planlıdır. . Günümüzde ise medrese, çini sanatın gelişmesine ev sahipliği yapan atölyelerin de bulunduğu bir çarşı halindedir.

Açılış Zamanı: 08:00 – 17:00

Nikaıa İznik

Nilüfer Hatun İmaretine giderken sağ tarafta göreceğiniz çarşı içinde, çini ve çeşitli takılarla beraber hediyelik eşya alabileceğiniz pek çok dükkanı bir arada bulabileceksiniz. Ayrıca ortasında minik de bir çay bahçesi mevcut.

Nilüfer Hatun İmareti (İznik Müzesi)

Nilüfer Hatun İmareti olarak da bilinen yapı, 1388 yılında Sultan 1. Murat'ın annesi olan Nilüfer Hatun adına yaptırılmıştır. İmaret olarak inşaa edilen yapı, yoksullar için hergün yemek dağıtılan bir hayır kurumuydu.

Binanın planı ters T harfi şeklindedir. Bina bir kat küfeki taşı üç kat tuğla sistemiyle inşa edilmiş olup, zengin ve renkli bir taş ve tuğla işçiliğine sahiptir. 19. yüzyılın sonlarına kadar imaret işlerini sürdüren yapı Kurtuluş Savaşı'nda Yunan işgali esnasında büyük ölçüde tahrip olmuştur. Cumhuriyet döneminde 1960'lı yıllara kadar depo olarak kullanılmıştır. 1960 yılında restore edilen Nilüfer Hatun İmareti aynı yılın ağustos ayında müze olarak halkın hizmetine açılmıştır. Müzede İznik ve çevresinden çıkarılan arkeolojik buluntular ile Ilıpınar, İznik Roma Tiyatrosu ve İznik'teki çini fırınları kazılarından çıkarılan eserler sergilenmektedir. Müze bahçesinde Yunan, Roma, Bizans ve Osmanlı eserleri (sütun başlıkları, lahitler, kabartmalar, korkuluk levhaları, ambonlar, siterler, yazıtlar, çörtenler, sütun tanburları, vaftiz havuzları, pişmiş toprak levhalar ve mezar taşları) yer alır.

Şeyh Kubbettin Camisi ve Türbesi

İznik ilçe merkezinde Nilüfer Hatun imareti karşısında cami ve bitişiğinde türbe. Gerek cami, gerekse türbeyi yaptıran kimliği kesin olarak belirlenememiştir.

Hacı Özbek Cami

Osmanlı Devletinin ilk camisi olan Hacı Özbek Camii mevki olarak, Lefke kapıya giden ana cadde üzerinde bulunmaktadır. Kitabesine göre Hacı Özbek b. Mehmed tarafından 734 (1333-1334) yılında inşa ettirilen yapı, kitabesi mevcut en eski Osmanlı eseri olma özelliğini taşımaktadır.

İznik fethedildikten iki – üç yıl sonra yapılan Hacı Özbek Camii, anlam olarak ta müslüman Türklüğün ilk eseri olarak dikkat çekmekte fakat Kurtuluş Savaşı sırasında Ayasofya Orhan Cami gibi oda tahribattan payını almıştır. 1950’li yıllarda cadde genişletilmesi sırasında Hacı Özbek Camisinin son cemaat yeri de yıkılmıştır.

Hacı Özbek Camii, aralarında tuğla hatıllar olmak üzere taştan karma malzeme ile inşa edilmiştir. Caminin yapımında erken Osmanlı Türk yapı sanatında çok kullanılan, taşların aralarına dikine tuğla konulması tekniği uygulanmış, kemerlerde son dönem Bizans yapı sanatında yaygın olan bir küfeki taşı arasına üç tuğla konulması suretiyle meydana getirilen örgü kullanılmıştır. Bu da bu İslâm yapılarında yerli Bizanslı duvarcı ustalarının çalıştığını gösterir.

Kare planlı cami 7,5 x 7,5m. ölçülerindedir. Zaman içinde değişiklikler geçirmiş, eklemeler yapılmıştır

İznik Çini Vakfı

İznik Çinileri, İznik Vakfı İle Hayat Buluyor

İznik Eğitim ve Öğretim Vakfı 1993 yılı Eylül ayında Prof. Dr. Işıl Akbaygil'in öncülüğünde, İznik çinisini ve İznik çevresinin kültür ve sanat değerlerini tanıtmak, mevcut potansiyeli harekete geçirmek, geleneksel İznik Çini Sanatı ile ilgili var olan ve elde edilecek bilgileri bir sistem dahilinde eğitim ve öğretimle gelecek kuşaklara aktarmak amacıyla kurulmuştur.

16. Yüzyıl İznik Çini Sanatı’nın, dünya seramik edebiyatında hala zirvede kalmasından da anlaşılacağı gibi, İznik Çiniciliği’nin günümüz teknolojisine; kaliteyi ve estetiği bozmadan uyarlanabilmesi çok büyük önem taşımaktadır. İlk amaç olarak geleneksel İznik Çini Sanatı’nı ele alan ve bu sanatı canlandırmaya çalışan İznik Eğitim ve Öğretim Vakfı, araştırmalarını 1993 yılından itibaren devam ettirmektedir.

300 yıldır üretilmeyen dünyaca ünlü İznik çinilerine yıllar sonra yeniden hayat veren İznik Vakfı, ürettiği çinilerle dünyanın dört bir tarafında İznik çinilerini yaşatıyor. İznik Vakfı tarafından Kanada Montreal’deki Botanik Bahçesi içinde yer alan sanat tarihinde Osmanlı ile özdeşleşmiş lale deseni, Tokyo gibi birçok şehirde daha hayat buluyor. İznik Vakfı, birbirinden özel İznik çinisi örnekleriyle Avrupa Birliği programı kapsamında hazırlanan ‘Dünya Seramik Yolu’ projesine dahil oluyor.

Sahil yolundan tabelasını takip ederseniz sokak arasında mekanı göreceksiniz. (Not: Kapalı zannedip geri dönmeyin), demir kapıyı kendiniz açarak içeri girebilirsiniz. Büyük bir bahçe içinde kurulan vakfın ayrıca içinde satış noktası var. Marmaraydaki çiniler burada yapılmış ve fotoğraflarda da göreceğiniz gibi bahçesinde büyük bir çini örneği ve dinlenebileceğiniz banklar mevcut.

Telefon: 0 224 757 6025

ABDÜLVAHAP SANCAKTÂRÎ (Bayraklı Dede)

(Abdullah Dede)

VIII. yüzyılda yaşadığı varsayılan söylencesel kişi. İslâm ordularının Anadolu'yu geçerek Bizans'ı düşürme savaşımının sürdüğü 717-740 yılları arasında, Abdülvahap adlı bir sancaktarın yiğitliğinden söz edilir.

Söylence, Erdoğan Savaş'ın anlatımıyla şöyle:

"Üsküdar'a kadar gelen İslâm orduları birkaç kere İznik'i kuşatmışlardı. Kuşatma sırasında genç sancaktar Abdülvahap büyük yararlıklar göstermiş ve bu arada gönlünü genç bir Rum kızma kaptırmıştı. İznik surlarının Hotoz burcu, Rum kızları tarafından müdafaaa edilmekte idi. Sancaktan, Kızlar burcunu müdafaa eden sevgilisi Rum kızı ile uzun müddet sevişti. Sevgilisi. her defasında kendisine Kaleyi alırsan beni de alırsın' diye bağırmıştır. Genç sancaktar sevgilisine kavuşamadan bir düşman oku ile yaralanmış ve hücum eden tekfurlar tarafından başı uçunılmuştur. Buna rağmen kılıç sallamakta devam eden Sancaktarî'ye bir arkadaşının 'Bre Abdullah, başını unuttun' demesi üzerine, Sancaktan geri dönmüş ve başını koltuğuna alarak yedi adımda bugün yattığı tepeye çıkıp kendini defnetmiştir. Türkler İznik'i zaptedince, din uğruna şehit olan Abdülvahap için bir mezar inşa etmişlerdir. (Erdoğan Savaş, İznik)"

İznik'in doğusunda, kente egemen bir tepe üzerinde bulunan mezarı ziyaret yeridir. Ziyaretçiler tarafından bayrak asıldığı için "Bayraklı Baba" adıyla da anılır.

Yeşil Cami

Şehrin en tarihi yapılarından biridir. Çandarlı Halil paşa zamanında başlayıp (1378), onun oğlu Ali paşa döneminde bitirilmiştir (1392). Eserin mimarı Mimar hacı Musa dır. Osmanlı döneminin tek kubbeli camilerine örnek olan bir yapıdır. Özellikle mermerden yapılmış caminin minberi görülmeye değerdir. Caminin muhtelif yerlerinde zengin bir taş işçiliği vardır. Minaresi caminin sağ köşesinde yer alır. Gövdesi ve şerefenden sonrası mavi ve yeşil renkte çinilerle zikzaklı mozaik tekniğine örnek bir yapıdır. Adını da bu yeşil çinili ve tuğlalı minaresinden almıştır.

Şehrin en tarihi yapılarından biridir. Çandarlı Halil paşa zamanında başlayıp (1378), onun oğlu Ali paşa döneminde bitirilmiştir (1392). Eserin mimarı Mimar hacı Musa dır. Osmanlı döneminin tek kubbeli camilerine örnek olan bir yapıdır. Özellikle mermerden yapılmış caminin minberi görülmeye değerdir. Caminin muhtelif yerlerinde zengin bir taş işçiliği vardır. Minaresi caminin sağ köşesinde yer alır. Gövdesi ve şerefenden sonrası mavi ve yeşil renkte çinilerle zikzaklı mozaik tekniğine örnek bir yapıdır. Adını da bu yeşil çinili ve tuğlalı minaresinden almıştır.

Şehrin en tarihi yapılarından biridir. Çandarlı Halil paşa zamanında başlayıp (1378), onun oğlu Ali paşa döneminde bitirilmiştir (1392). Eserin mimarı Mimar hacı Musa dır. Osmanlı döneminin tek kubbeli camilerine örnek olan bir yapıdır. Özellikle mermerden yapılmış caminin minberi görülmeye değerdir. Caminin muhtelif yerlerinde zengin bir taş işçiliği vardır. Minaresi caminin sağ köşesinde yer alır. Gövdesi ve şerefenden sonrası mavi ve yeşil renkte çinilerle zikzaklı mozaik tekniğine örnek bir yapıdır. Adını da bu yeşil çinili ve tuğlalı minaresinden almıştır.

Kırgızlar Türbesi

Yenişehir Kapı dışında surlardan 250 m. ileride İznik-Yenişehir asfaltının sağındadır. İznik'in Türkler tarafından fethi sırasında yararlılıklar gösteren Kırgız Türklerinin anısına, Orhan Gazi tarafından 1331 tarihinde inşa ettirilmiştir. İçinde yedi büyük ve bir çocuk lahdi bulunmaktadır. Türbe, mimarisi ile kalem işi süslemeleri bakımından büyük değer taşır.

İsmail Bey Hamamı

İsmail Bey Hamamı, İznik’te İstanbul Kapısı yakınında hamam. Çeşitli uzmanlar yapıyı 14-17. yüzyıllar arasında değişik zamanlara tarihlemektedir. Boyutlarına ve iç düzenine bakarak bir saraya ait özel bir hamam olduğunu ileri sürenler de vardır. Zamanında beşik tonozla örtülüyken bugün yalnız temelleri kalmış olan bir girişten asıl hamama geçilir. Hamamın dört bölümüne, birbiri içinden geçilerek ve saatin tersi yönünde ilerlenerek ulaşılır. Bölümlerin her birinin duvarları ve kubbelerinin içleri birbirinden farklı, ama hepsi de çok zengin malakâri bezemelerle kaplıdır.

İsmail Bey Hamamı bugün oldukça yıkık durumdadır.

#berebergezsek#kültür#gezi#iznik#Ayasofya Cami#İznik Roma Tiyatrosu#İstanbul Kapı#Lefke Kapı#çini#Klise Kalıntıları#Eşrefzade Camisi ve Türbesi (Eşrefi Rumi)#Süleyman Paşa#Nikaıa#Nilüfer Hatun İmareti#İznik Müzesi#Şeyh Kubbettin#Hacı Özbek#İznik Çini Vakfı#ABDÜLVAHAP SANCAKTÂRÎ#Bayraklı Dede#Yeşil Cami#Kırgızlar Türbesi#İsmail Bey Hamamı

0 notes

Text

Fatih Sultan Mehmet (1451-1481)

Fatih Sultan Mehmet (1451-1481)

Genel Bilgiler

1432 yılında Edirne’de dünyaya gelen Fatih Sultan Mehmet, Osmanlı Padişahları’nın 7.’sidir. Babası II.Murat ve annesi Huma Hatun’dur.

Fatih Sultan Mehmet ’ten sonra padişah olan oğlu, II.Bayezid, Fatih Sultan Mehmet’in Mükrime Hatun adlı eşinden dünyaya gelmiştir. Mükrime Hatun Dulkarioğlu Süleyman Bey’in kızıdır. Diğer eşleri ise Emine Hatun, Helene Hatun, Alexias Hatun,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sarayların 'sim sırması' cazibesini yitirmiyor

KAHRAMANMARAŞ – İsmail Hakkı Demir Osmanlı padişahlarından Çelebi Mehmed‘in eşi Emine Hatun ve Fatih Sultan Mehmed‘in eşi Sitti Mükrime Hatun‘un çeyizleri arasında da bulunan Maraş işi “sim sırma“, farklı alanlardaki kullanımıyla günümüzde de cazibesini yitirmiyor. Geçmişi Selçuklular dönemine kadar uzanan Kahramanmaraş’a özgü geleneksel el sanatı “sim sırma” işlemeciliği, kentte ustaları…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Asilliğinden de Ödün Vermez Mükrime Hanımın Kızı @ayselayferturegun @cemturegun @cratospremiumhotel #cratospremium #cratospremiumhotel #kktc #kibris #cyprus ❤❤❤❤ (CRATOS Premium | Hotel & Casino)

0 notes

Note

Favorite consort of each sultan?

I gotta be honest, I don't have a favourite for each sultan, especially the early ones... that's really not my period at all. But I tried!!

Osman Gazi: ? I truly have no idea. Both Mal and Rabia Hatun are indifferent to me

Orhan Gazi: Theodora Kantakuzene

Murad I: ? I have no idea

Bayezid I: Maria Olivera Despina Hatun for sure

Çelebi Mehmed: no idea

Murad II: Mara Branković

Mehmed II: Çiçek Hatun and Sitti Mükrime Hatun

Bayezid II: I don't know

Selim I: well, Ayşe Hafsa of course LOL

Süleyman I: Hürrem (LOL)

Selim II: Nurbanu

Murad III: Safiye

Mehmed III: both Handan and Halime

Ahmed I: Kösem LOL

Mustafa I: had no consorts

Osman II: poor Meylişah Hatun, I feel so bad for her

Murad IV: ?? no idea

Ibrahim Han: Hümâ-Şâh Sultan and Hatice Muazzez Sultan

Mehmed IV: Emetullâh Rabî'a Gül-nûş Sultan and Afife Hatun/Kadın

Süleyman II: no idea

Ahmed II: Haseki Rabia Sultan

Mustafa II: Afife Kadın

Ahmed III: no idea tbh

Mahmud I: no idea

Osman III: no idea

Mustafa III: Mihr-i Şâh Sultan

Abdülhamid I: Hadîce Ruh-şâh Başkadınefendi

Selim III: Refet Kadın, only because she tried to prevent his assassination. It's something that wasn't expected of her so that kind of moved me

Mustafa IV: no idea

Mahmud II: Hacıye Pertev-Piyâle Nev-fidân Başkadınefendi and Bezmialem Sultan

Abdülmecid I: Servet-sezâ Başkadınefendi, Ayşe Ser-firâz Hanımefendi and Bezmiara Kadın

Abdülaziz Han: Gevheri Kadınefendi

Murad V: Meyl-i Servet Kadınefendi

Abdülhamid II: Nâzik-edâ Başkadınefendi, Bedr-i Felek Başkadınefendi

Mehmed V: Nâz-perver Kadınefendi

Mehmed VI: Emîne Nâzik-edâ Başkadınefendi and Inşirâh Hanımefendi

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marriages /Házasságok

The institution of marriage in the Ottoman Empire has always been an interesting topic. There was a great difference in the general conception of the marriages of sultans, sultanas, şehzades, pashas, and concubines. In this post, I would like to introduce you to the different forms of marriage.

First of all lets discuss the marriages of the sultans. The sultans of the earlier periods of the Ottoman Empire, regularly married women from the ruling dynasty of smaller and larger empires to strengthen their power and gain supporters. This was done, among others, by Murad I (reign: 1362-1389), who married Tamara, the daughter of the Bulgarian Tsar Ivan Alexander, so that he could have the Bulgarians as his supporters. Tamara was one of the greatest beauties of that period and she was specially chosen for him.

His namesake, Murad II (r. 1421-1444 and 1446-1451) married the daughter of a Serbian lord, George Brankovic, Mara Brankovic (1416-1487), who over time became one of the most famous women of her age. Mara's father was loyal to the Ottomans just until the death of Murad II. Mara however, even after Murad's death, decided not to return home but to stay with her adoptive son, Mehmed II (r. 1444-1446 and 1451-1481). She remained with Mehmed and served him as his adviser for the rest of her life. Mehmed II, by the way, is particularly important in the subject of marriage, because he was the one who began the tradition of sultans not to marry. It is interesting because Mehmed himself was married, his wife was choosed by his father Murad II. This is also a good indication of the importance of dynastic marriage during this period. The sultan himself chosed woman to his son, similar to European customs. His choice fell on the daughter of the ruler of the state of Dulkadir, Mükrime. However, their marriage remained childless, since Mehmed showed no interest on Mükrime, even though the wedding celebration lasted for three months! (No other wedding has ever been celebrated for so long.)

Marriages between sultans and noble women thus ceased during the reign of Mehmed II (r. 1444-1446 and 1451-1481). The reason for this was simple. After the occupation of Constantinople, the Ottoman Empire became strong and was more troubled by a noble relative than helped by them. They no longer needed the support of the ruler dynasty of other countries. This is precisely why it caused such outrage when a narrow hundred years later, Süleyman I (r. 1520-1566) married his enslaved love, Hürrem (⁓1503-1558). Although marriage for the sultans was not forbidden, but it has not been a habit since Mehmed II. In particular, not the marriage with a liberated slave. Süleyman began a new habit with this, as his descendants followed this form of marriage. So did Suleiman's son, Selim II (r.1566-1574), who married his love, Nurbanu (⁓1525-1583), almost immediately after becoming sultan. Seeing this pattern in front of him, their son Murad III (r. 1574-1595) also considered marrying his favorite concubine, but sources do not agree on whether he eventually married Safiye (⁓1550-1620?) or not.

A big turn came during the reign of Osman II (r. 1618-1622) in the field of marriages. Osman ascended the throne as a young boy, and as an orphan. His mother died when he was a child, so no one was behind him when he ascended the throne. Osman desperately sought to gain supporters for himself (as did the sultans of the very early period of the Ottoman Empire), so he married the daughter of Seyhülislam Efendi, Akile (1607-1638). Unfortunately, even his marriage couldn't rescu Osman, who was eventually executed during a Janissary rebellion. After Osman, the crazy Ibrahim I (r.1640-1648) was the one who married extremely. Although he did not marry a noble woman, but a simple concubine, Telli Hümaşah (⁓1630-1672), he he gave her extreme benefits. He made her one of the richest women in the empire, gave her the residence of the Valide Sultan (regardless of whether Ibrahim's mother, Kösem Sultan (⁓1590-1651) was alive!) and ordered her own sisters to serve his wives and he took away all of their property, just to give it to his wife. This extreme case brilliantly closed the marriages of the sultans for a long time in the history of the Ottoman Empire so that it could then be revived in the later periods.

In addition to sultan marriages, it is important to mention sehzades as well. Mehmed II's example, mentioned above, shows well that the marriage of princes was an important part of the daily life of the empire in the early period. II. During Mehmed's reign, however, in addition to the sultans, the marriages of the princes also changed. This practically means that although it was not forbidden by a specific law, but the princes could not marry either a noble woman or a simple concubine. And this custom persisted for centuries. When Süleyman I (r. 1520-1566) created the rank of Haseki, the former was supplemented by the fact that the princes could not even give the rank of Haseki to their concubines! These facts help to clear up a great deal of misunderstanding from the history of the Empire. For example:

Mehmed (1521-1543), the son of Süleyman I, could never marry his own cousin, Esmehan Baharnaz (1525-1559?).

The other sons of Süleyman I, Mustafa (1515-1553) and Bayezid (1525-1562), never had Hasekies, since not even the concubine could have the rank of Haseki who were single consorts of the princes. Thus Nurbanu herself (⁓1525-1583), the beloved concubine of later Selim II (r. 1524-1574), could carry the rank of Haseki only when Selim II ascended the throne.

Furthermore, one of the most important conclusions is that, because of this custom, Ayşe Hafsa (⁓1475-1534) could not be the wedded wife of Selim I (r. 1512-1520) contrary to rumors. Selim was just a prince when he took Hafsa as a consort. And this also highlights that Ayşe Hafsa could not have been a Crimean princess, as the princes could not marry, especially not the women of other dynasties. This is further strengthened by the fact that Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512) (Selim's father) didn't want to see Selim on the throne at all, so he would never allowed him to marry a Crimean princess. The origin of the legend may be that Hafsa may have been given to Selim as a gift from the Crimean dynasty, or perhaps she was a Crimean Tatar by origin.

But what about the sultanas? The sultanas were heavily exploited to strengthen the dynasty (the same as any female members of other dynasties). There have been more extreme periods and more acceptable ones in this era. In any case, in the earliest period of the empire, the sultans gave their daughters as wives to their supporters, and possibly married to neighboring dynasties for peace. A great example of the latter is the daughter of Murad I (r.1362-1389), Nefise Melek Hatun (⁓1363-1402?) whom his father added to the Kahramani ruler at the age of 18 to make peace. However, peace could not be maintained, so for a time Nefise Melek Hatun was placed under house arrest in her homeland along with her sons. Eventually, her situation was resolved and her eldest son was appointed to the throne of Kahraman after the two states managed to reach an agreement. However, these marriages were considered less frequent, it was more common for the sultan to honor the pashas who supported them with the grace that they could marry his daughters and sisters.

But it wasn't just the sultans who could benefit from their own daughters! Although Mehmed II (r. 1444-1446 and 1451-1481) forbade his sons to marry women of influential families, but he did not make stipulation that sehzades could not marry off their own daughters to these influential families. For example, Mehmed II's son, Bayezid (r.1481-1512), made an alliance — later life-saving alliance — with influential pasha by giving his daughters to them. He managed to ascend the throne actually due in large part to this. Later, the princes could not marry off their daughters by their own advantages, precisely in order to avoid such alliances. For example, Süleyman I (r. 1520-1566) was the one who decided to whom he should marry his granddaughters. His sons couldn't influence his decision. It is an interesting observation that he married off the eldest daughter of Mustafa (1515-1553), to a non-influential pasha, while the late Mehmed's (1521-1543) daughter or the daughter of Mihrimah (1522-1574) were married to influential pashas, as well as the later Selim II's daughters. In contrast, the daughters of his traitorous son, Bayezid (1525-1562), were married off almost out of their rank.

It can be seen, then, that the marriages of the sultanas have always been a very important part of the life of the Empire. But there were huge differences in how much these women were exploited. In the earliest periods of the empire, they generally acted in a fair manner, and even a second marriage was often rare for female members of the dynasty. Over time, that number has grown. The daughters of Selim I (r. 1512-1520) so the sisters of Süleyman could even claim a relatively normal number of marriages, such as Hatice Sultan (1491-?) who was married off once or twice, Fatma Sultan (1493-1557) three times, Hafsa Sultan (1500-1538) twice, Gevherhan Sultan (1494-?), Hanim Sehzade Sultan (? -?), Şah-i Huban Sultan (1500-1572) and Beyhan Sultan (1492-1559) were married only once. They had chance to decide how many times they married and after a certain age could live their life in peace. Thus, for example, Şah-i Huban herself decided to retire and did not remarry after her divorce. However, it is important to note that during this period, the sultanas were married off at the generally accepted age of 17-18. By the way, Süleyman was permissive with his daughter also, so Mihrimah (1522-1574) did not remarry after her widowhood.

There was no significant change during the reign of Murad III (r. 1574-1595), he too was explicitly permissive with her sisters (though probably more under pressure of his mother). After her sisters were widowed, they were able to choose their next husbands themselves. Thus, the widow of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha (1505-1579), Esmehan (1545-1585) married to Kalaylikoz Ali Pasha. Regarding Esmehan, it is important to mention that she was already longing for a husband in the same age as her (Sokollu was more than 40 years older than her). So she chosed a very handsome beylerbey, but the man rejected the marriage offer, this is why Esmehan was forced to look for someone else, so she got to her later husband Kalaylikoz Ali. Unfortunately, they weren't able to spent too much time together because barely a year after their wedding, Esmehan died in childbirth with her child. Esmehan’s sister, Şah Sultan (1544-1580), was also able to marry to her true love, Zal Mahmud Pasha. Their love was legendary, even death hit them at once, presumably due to illness. Murad III was less forgiving with his daughters, they too were married two or three times and not to the one they wanted. However, in addition to Murad, their mother, Safiye (⁓1550-1620?), could also play a role in this.

Soon after Murad III (r. 1574-1595) the most extreme period of marriages occurred. His grandson, Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617), married off his daughters at an extremely young age. Before I get into the details, it’s important to understand why he did that. Ahmed ascended the throne at a very young age but he did not serve in a sanjak before, this he did not have any supporters, so he had to quickly chain influential pashas to himself. The best way to do that was through marriage. While other sultans already had more adult daughters when they ascended the throne, Ahmed was childless. Over time, several daughters were born, whom he married off as infants. Of course, this did not mean a practical marriage! The infant girls did not have to live with the pashas, but were allowed to stay in the harem with their mothers, and by no means had to leave the palace until puberty. By then, usually, their husbands had either died a natural death or been executed. However, for these girls, this was not the only extremism in their lives. After the death of their father, a very complicated period ensued, but in the end, with a few detours, their younger brother, Murad IV (r. 1623-1640) came to power, who also needed supporters, so he married off his sisters often: if one of their husbands died, the next came, and so on. Unfortunately even after Murad's death, during the reign of Ibrahim I (1640-1648), they could not find peace because they were forced to remarry. Thus, the daughter of Ahmed I, Ayşe (⁓1608-1657?) may have married at least six times, while Fatma (⁓1606-1670) seven times! At the time of their last marriages, they were already old themselves, Ayşe was already 50 and Fatma was 61 years old. With the death of these sultanas, this extreme period also ended fortunately, so that later the sultanas were later raised around the generally accepted age.

Finally, I would like to say a few words about simple concubines. Although many of us have the image that the concubines who were not lucky enough to become consorts of the sultan, got old and died in the harem. However, this was not the case, especially rarely did any of the concubines grow old in the harem. The concubines were changed regularly, they always borught some new, younger women. So those who had been there for too long and began to age and had no chance of becaming the consort of the sultan, were simply married off. These marriages were a great advantage for both parties. It was a great prestige for an agha, a lower-ranked officer or a pasha to be able to get a wife from the imperial harem. And with this, the concubines were given a chance for a new life, far away from the dark and threatening world of the harem.

Used source: Leslie Peirce - THE IMPERIAL HAREM - Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire

* * *

A házasság intézménye az Oszmán Birodalomban mindig is egy érdekes téma volt. Nagy volt ugyanis az eltérés az általános felfogásban a szultánok, szultánák, hercegek, pasák és az ágyasok esetében. Ebben a posztban a házasságok különböző formáit szeretném bemutatni nektek.

Először is kezdjük a szultánok házasságaival. Az Oszmán Birodalom korai szultánjai rendszeresen házasodtak kisebb-nagyobb birodalmak uralkodócsaládjából származó asszonyokkal, hogy hatalmukat erősítsék és támogatókat szerezzenek. Így járt el többek között I. Murad (uralkodás 1362-1389) aki elvette Tamarát, a bolgár Ivan Alexander cár lányát (aki a kor egyik legnagyobb szépsége volt), hogy a bolgárokat támogatóként tudhassa maga mellett.

Névrokona, II. Murad (uralkodás 1421-1444 és 1446-1451) egy szerb fejedelem, Brankovic György leányát, Mara Brankovic-ot (1416-1487) vette nőül, aki idővel az egyik leghíresebb asszonya lett korának. Mara apját a frigy csupán II. Murad haláláig kötötte az oszmánokhoz, Mara azonban Murad halála után is úgy döntött, hogy nem tér haza, hanem fogadott fia, II. Mehmed (uralkodás 1444-1446 és 1451-1481) mellett marad és annak tanácsadójaként szolgálta a birodalmat élete végéig. II. Mehmed egyébként különösen fontos a házasság témakörében, ugyanis ő volt az, aki elkezdte azt a tradíciót miszerint egy szultán ne házasodjon. Érdekes, ugyanis maga Mehmed nős volt, feleségét még apja II. Murad választotta ki számára. Ez is jól mutatja, hogy ebben az időszakban milyen fontos volt a dinasztikus házasság. A szultán maga választott asszonyt fiának, hasonlóan az európai szokásokhoz. Választása a Dulkadir állam uralkodójának lányára, Mükrimére esett. Házasságuk azonban gyermektelen maradt, Mehmed nem mutatott érdeklődést arája iránt, pedig az esküvői ünneplés három hónapig tartott! (Soha egyetlen másik esküvőt nem ünnepeltek ilyen hosszan.)

A házasságkötések a szultánok és nemes asszonyok között tehát megszűntek II. Mehmed (uralkodás 1444-1446 és 1451-1481) uralkodása alatt. Ennek oka egyszerű volt. Az Oszmán Birodalom Konstantinápoly elfoglalása után elég erőssé vált és inkább jelentett nekik nyűgöt egy nemesi rokon, mint segítséget. Nem volt már többé szükségük más országok uralkodóinak támogatására. Pontosan ezért keltett olyan nagy felháborodást, amikor szűk száz évvel később I. Szulejmán (uralkodás 1520-1566) feleségül vette rabszolgából lett szerelmét, Hürremet (⁓1503-1558). Bár nem volt tilos a házasság a szultánoknak, azonban II. Mehmed óta ez nem volt szokás. Különösen nem egy felszabadított rabszolga feleségül vétele. Szulejmán egy új szokást kezdett el ezzel, ugyanis leszármazottjai követték ezt a házasodási formát. Így tett Szulejmán után annak fia, II. Szelim (uralkodás 1566-1574), aki szultánná válása után szinte azonnal nőül vette szerelmét, Nurbanut (⁓1525-1583). Ezt a mintát látva maga előtt, fiuk III. Murad (uralkodás 1574-1595) is fontolgatta kedvenc ágyasának feleségül vételét, ám a források nem egyeznek abban, hogy végül valóban nőül vette e Safiyét (⁓1550-1620?) vagy sem.

Nagy fordulat állt be II. Oszmán (uralkodás 1618-1622) uralkodása alatt a házasságkötések terén. Oszmán ugyanis gyermekként került trónra, árván. Anyja még gyermekkorában meghalt, így nem állt mögötte senki trónra lépésekor. Oszmán elkeseredetten igyekezett támogatókat szerezni magának (csakúgy, mint a rég múlt idők szultánjai), ezért feleségül vette a Seyhülislam Efendi leányát, Akilét (1607-1638). Sajnos Oszmánt a frigy sem tudta megmenteni és végül kivégezték egy janicsár lázadás során. Oszmán után az őrült I. Ibrahim (uralkodás 1640-1648) volt a következő, aki extrém házasságot kötött. Ő ugyan nem nemes asszonyt vett nőül, hanem egy egyszerű ágyast, Telli Hümaşaht (⁓1630-1672), azonban extrém juttatásokat adott neki. Őt tette a birodalom egyik leggazdagabb asszonyává, nekiadta a valide szultána lakrészét (függetlenül attól, hogy Ibrahim édesanyja, Kösem (⁓1590-1651) szultána életben volt!), valamint saját vérszerinti lánytestvéreit arra kötelezte, hogy szolgálják feleségét és minden vagyonukat elkobozta, hogy azt is nejének adja. Ez az extrém eset remekül zárta le a szultánok házasságkötéseit hosszú időre az Oszmán Birodalom történetében, hogy aztán a későbbi időszakban újraéledhessen.

A szultáni házasságkötések mellett fontos, hogy a hercegeket is megemlítsük. Mint II. Mehmed fentebbi példája jól mutatja, a hercegek kiházasítása fontos részét képezte a birodalom mindennapjainak a korai időszakban. II. Mehmed uralkodása alatt azonban a szultánok mellett a hercegek házasodási szokásai is megváltoztak. Ez gyakorlatilag azt jelenti, hogy bár nem konkrét törvény tiltotta, de a hercegek nem házasodhattak sem nemes asszonnyal, sem egyszerű ágyassal. Ez a szokás pedig bőven kitartott évszázadokig. Amikor I. Szulejmán (uralkodás 1520-1566) megalkotta a Haseki rangot, ez az előbbi még annyival kiegészült, hogy a hercegek még Haseki rangot sem adhattak ágyasaiknak! Az, hogy ezt most már tudjuk, nagyon sok félreértést segít tisztázni a birodalom történetéből. Így például a következőket:

I. Szulejmán fia, Mehmed (1521-1543) sosem vehette nőül saját unokatestvérét Esmehan Baharnazt(1525-1559?).

I. Szulejmán másik fiainak, Mustafának (1515-1553) és Bayezid (1525-1562) hercegeknek sosem volt Hasekije, hiszen még ott sem kaphatott Haseki rangot az ágyas, ahol nem volt mellette senki más a herceg életében. Így maga Nurbanu (⁓1525-1583), a későbbi II. Szelim (uralkodás 1524-1574) egyetlen, szeretett ágyasa sem viselhette a Haseki rangot, csak miután II. Szelim trónra lépett.

Továbbá egyik legfontosabb következtetés, hogy emiatt a szokás miatt nem lehetett Ayşe Hafsa (⁓1475-1534) I. Szelim (uralkodás 1512-1520) hites felesége a híresztelésekkel ellentétben. Szelim ugyanis még csak herceg volt, mikor Hafsát maga mellé vette. Ez pedig rávilágít arra is, hogy Ayşe Hafsa nem lehetett Krími hercegnő, hiszen a hercegek nem nősülhettek, különösen nem más dinasztiák asszonyaival. Ezt tovább erősíti, hogy II. Bayezid (uralkodás 1481-1512) (Szelim apja) a legkevésbé sem akarta Szelimet látni a trónon, tehát sohasem engedte volna neki, hogy egy Krími hercegnőt vegyen nőül. A legenda eredete talán az lehet, hogy Hafsa a Krími dinasztia ajándékaként kerülhetett Szelimhez, esetleg krími tatár származású volt.

Na de mi volt a helyzet a szultánákkal? A szultánákat, csakúgy mint más dinasztiák nőtagjait, jócskán kihasználták a dinasztia megerősítésének céljából. Voltak e téren extrémebb időszakok és viszonylag elfogadhatóbbak. Mindenesetre a birodalom legkorábbi időszakától kezdődően a szultánok támogatóikhoz adták nőül leányaikat, esetleg szomszédos dinasztiákba házasították be őket a béke érdekében.

Utóbbira remek példa Nefise Melek Hatun (⁓1363-1402?), I. Murad (uralkodás 1362-1389) leánya, akit 18 éves korában apja hozzáadott a Kahramani uralkodóhoz, hogy békét köthessenek. A békét azonban nem sikerült fenntartani, így egy időre Nefise Melek Hatun háziőrizetbe is került hazájában fiaival együtt. Végül helyzete megoldódott, és legidősebb fiát kinevezték a Kahramani trónra, miután sikerült a két államnak egyezségre jutni. Ezek a házasságok azonban ritkábbnak számítottak, gyakoribb volt, hogy a szultán az őt támogató pasákat tüntette ki azzal a keggyel, hogy nőül vehették leányait, nővéreit.

Na de csak nem csak a szultánok húzhattak hasznot saját lányaikból! Bár II. Mehmed (uralkodás 1444-1446 és 1451-1481) megtiltotta, hogy fiai befolyásos családok asszonyaival házasodjanak, arra nem tett kikötést, hogy a hercegek saját lányaikat kiházasíthatják e befolyásos családok fiaihoz. Így például II. Mehmed fia, Bayezid (uralkodás 1481-1512) úgy kötött – később számára életmentő – szövetséget befolyásos pasákkal, hogy leányait hozzájuk adta. Trónját tulajdonképpen nagyon nagyrészt ennek köszönheti. Később a hercegek nem igazán dönthettek önállóan leányaik kiházasításáról, pont az ilyen szövetségek elkerülése végett. Így például I. Szulejmán (uralkodás 1520-1566) is maga döntötte el, hogy leányunokáit kikhez adja nőül. Érdekes megfigyelés éppen ezért, hogy Musztafa (1515-1553) – akiben saját riválisát látta – leányát nem befolyásos pasához adta feleségül, míg a megboldogult Mehmed (1521-1543) lányát vagy Mihrimah (1522-1574) leányát befolyásos pasákhoz adta nőül csakúgy, mint a későbbi II. Szelim leányait. Ezzel szemben áruló fia, Bayezid (1525-1562) leányait szinte épphogy csak rangjuknak megfelelően házasította ki.

Látható tehát, hogy a szultánák házasságkötései mindig is nagyon fontos részét képezték a birodalom életének. Ám hatalmas különbségek voltak abban, hogy mennyire használták ki ezeket a nőket. A birodalom legkorábbi időszakában általában meglehetősen fair módon jártak el, még a második házasság is gyakran ritka volt a dinasztia nőtagjai számára. Idővel ez a szám egyre bővült. I. Szelim (uralkodás 1512-1520) leányai, Szulejmán testvérei is még viszonylag reális számú házasságot tudhattak magukénak, így Hatice szultána (1491-?) egyszer vagy kétszer, Fatma szultána (1493-1557) háromszor, Hafsa szultána (1500-1538) kétszer, Gevherhan szultána (1494-?), Hanim Sehzade szultána (?-?) és Şah-i Huban szultána (1500-1572), Beyhan szultána (1492-1559) csupán egyszer mentek férjhez. Nekik még volt beleszólásuk abba, hogy hányszor mennek férjhez és egy bizonyos kor után békében élhették özvegye életüket. Így például Şah-i Huban maga döntött visszavonulása mellett és válása után sem házasodott újra. Mindemellett fontos megjegyezni, hogy ebben az időszakban, az általánosan elfogadott 17-18 éves korban adták férjhez a szultánákat. Szulejmán egyébként leányával is megengedő volt, Mihrimah (1522-1574) sem ment férjhez megözvegyülése után.

III. Murad (uralkodás 1574-1595) uralkodása alatt sem állt be jelentős változás, ő is kifejezetten megengedő volt testvéreivel (bár valószínűleg inkább anyja nyomására). Miután testvérei megözvegyültek, maguk választhatták ki következő férjeiket. Így Sokollu Mehmed Pasa (⁓1505-1579) özvegye Esmehan (1545-1585), Kalaylikoz Ali Pasához ment hozzá. Esmehannal kapcsolatban fontos megemlíteni, hogy ő már nagyon vágyott egy korabeli férjre (Sokollu több mint 40 évvel volt idősebb nála), ezért egy nagyon jóképű beglerbéget választott ki, ám a férfi elutasította a házassági ajánlatot, így Esmehan kénytelen volt mást keresni, így jutott el későbbi férjéhez Kalaylikoz Ali-hoz. Sajnos nem adatott meg nekik sok idő együtt, mert alig egy évvel esküvőjüket követően Esmehan belehalt a szülésbe gyermekével együtt. Esmehan testvére, Şah szultána (1544-1580) is igazi szerelmi házasságot köthetett Zal Mahmud Pasával. Szerelmük legendás volt, még a halál is egyszerre érte őket, feltehetőleg betegség következtében. III. Murad lányaival már kevésbé volt elnéző, ők is kétszer-háromszor házasodtak és nem ahhoz, akit ők szerettek volna. Ebben azonban Murad mellett anyjuk, Safiye (⁓1550-1620?) is szerepet játszhatott.

III. Murad (uralkodás 1574-1595) után hamarosan bekövetkezett a legextrémebb periódus a házasodások terén. Unokája, I. Ahmed (uralkodás 1603-1617) ugyanis extrém fiatalon házasította ki leányait. Mielőtt a részletekbe bocsátkoznék, fontos megértenünk a miértet. Ahmed nagyon fiatalon került trónra, mivel nem szolgált szandzsákban, nem voltak támogatói sem, így gyorsan kellett magához láncolni befolyásos pasákat. Ennek legjobb módja a házasság volt. Míg más szultánok trónra lépésükkor már több, felnőtt leánnyal rendelkeztek, addig Ahmed gyermektelen volt. Idővel több leánya is született, akiket sokszor már csecsemőként kiházasított. Ez természetesen nem jelentett gyakorlati házasságot! A csecsemőlányoknak nem kellett a pasákkal élni, hanem a háremben maradhattak anyjukkal, és a pubertás eléréséig semmiképpen nem kellett elhagyniuk a palotát. Addigra pedig általában a férjeik vagy természetes halált haltak vagy kegyvesztetté válva holtan végezték. Azonban ezeknek a lányoknak nem ez volt az egyetlen extrémitás az életükben. Apjuk halála után nagyon zavaros időszak következett, de végül néhány kitérővel gyermeköccsük IV. Murad (uralkodás 1623-1640) került hatalomra, akinek szintén szüksége volt támogatókra, így sokszor házasította ki testvéreit: ha egyik férjük meghalt, jött a következő, és így tovább. Szerencsétlenek még Murad halála után, I. Ibrahim (1640-1648) uralkodása alatt sem lelhettek nyugalomra, mert kénytelenek voltak újabb és újabb házasságokat kötni. Így lehet, hogy I. Ahmed leányai közül Ayşe (⁓1608-1657?) legalább hatszor, Fatma (⁓1606-1670) hétszer ment férjhez! Utolsó házasságkötéseik alkalmával már maguk is idősek voltak, Ayşe már 50 is elmúlt, Fatma pedig 61 éves volt. Ezen szultánák halálával ez az extrém periódus is lezárult szerencsére, így a későbbiekben újra az általánosan elfogadott kor körül adták nőül a szultánákat.

Végezetül szeretnék néhány szót szólni az egyszerű ágyasokról. Bár sokakban él az a kép, hogy azok az ágyasok, akik nem voltak elég szerencsések, hogy a szultán asszonyaivá váljanak a háremben öregedtek meg. Ez azonban nem így volt, kifejezetten ritkán öregedett meg bármelyik ágyas a háremben. Rendszeresen frissítették az ágyasokat, így aki túl régóta volt ott, kezdett idősödni és nem volt rá esély, hogy a szultánhoz kerülhessen, azt egyszerűen kiházasították. Ezek a házasságok mindkét fél számára igen nagy előnyt jelentettek. Egy egy agának, alacsonyabb rangú pasának igen nagy presztízst jelentett, hogy a birodalmi háremből kaphattak maguknak feleséget. A nők pedig esélyt kaptak egy új életre, maguk mögött hagyhatták a hárem sokszor sötét és fenyegető világát.

Források: Leslie Peirce - THE IMPERIAL HAREM - Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire

#mara brankovic#zal mahmud#hürrem sultan#hürrem#süleyman i#mihrimah sultan#mihrima#sokollu mehmed#sah-i huban

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

I read "Sultan Suleyman I. und seine Frauen" S. Woronzow-Daschkow. And I wonder how true his judgment about Gulfem-Khatun is? About the fact that she is his relative?

Firstly, I thought the author was a woman because the name is Salomé, so...

In any case, some of the sources she chose kind of worry me:

Natalia von Anrep: Mahidevran, Leipzig 2016 - this book is a literal cancer for Ottoman storiography. The things this woman assume.... yikes

Cagatay Ulusoy: Haremden Mektuplar, Istanbul 1956 - Ulusoy?? The historian is called Mustafa Çağatay Uluçay. Ulusoy is the actor

While the beginning of the reasoning seemed interesting to me:

“In the current Turkish chronicles, including Yilmaz Öztuna's masterpiece Devletler ve Hanedanlar series, Gülfem Hatun is listed among the wives and concubines of Suleyman I. However, it is not clearly proven that Gülfem Hatun was a wife or concubine of Suleyman’s. Sultan Bayezid II also had a wife named Gülfem, who continued to live in the sultan's palace after her husband's death. It is likely that Bayezid’s widow enjoyed a high reputation in Suleyman’s harem as step-grandmother, making her one of the most powerful women in the palace.”

I mean the premise is interesting and all but where is the evidence that this Gülfem was Bayezid II’s concubine Gülfem?

“Gülfem Hatun wrote in 1512 to her stepson Selim after his enthronement a significant letter in which she congratulated him on his coronation. Had Gülfem been a wife or concubine of Suleyman, she should never have written such a letter. It can also be assumed that Gülfem Hatun was a relative of Suleyman's mother Hafsa. For after the death or rather murder of her husband she did not go to Constantinople with the other women of Bayezid, but settled in the palace of the princes of Saruhan, where Hafsa resided with her son Suleyman.“

Again... where is the evidence that the Gülfem in Manisa is the same Gülfem that wrote Selim I a letter of congratulations? Moreover, where is the evidence that she was therefore a relative of Hafsa’s? Just because she allegedly went to Manisa?

And here, things get... yikes:

“A family relationship is confirmed not only by this development, but also by the fact that both women were Albanians.“

well, that seals it then. As we all know, in Albania there were only TWO women in the whole country at the end of the XV century so they cannot not be related.

The source is - naturally - Natalia von Anrep, whom I would really like to meet because the numerous backflips she does to justify a completely different family tree for Suleyman are truly astonishing. Like, she needs to be studied.

Also:

“In some sources, the birth mother of Selim I is called the Princess Ayşe of Dulkadir, who died in 1505. But it is more likely that the Albanian princess Gülbahar Hatice was the birth mother of Selim I.”

This woman lists Leslie Peirce’s book The Imperial Harem among the sources but still says this kind of bullshit? “Recent research has shown that Gülfem was born in 1492 as a princess of the Kastrioti dynasty and married Sultan Bayezid II in 1507”? No??? No research has shown this, no. Natalia Von Anrep is not “recent research has shown”

So... no. When she started linking everyone to noble houses she lost all my respect.

Also, the names of Suleyman’s other concubines.... Mükrime, Meleksima, Merziban... and his children? All those princesses who reached adulthood without anyone mentioning them? Please.

Fatma (1520 – 1572)

Hafiza (1521 – um 1560)

Raziye (1525 – 1556)

Hatice (ca. 1555 – nach 1575)

Schahihuban (ca. 1560 – um 1595)

No. No. No

In the sources of the Turkish version of this article - which is slightly different and shorter - she included a lot of archives but then she doesn’t say which info comes from which of her sources... and since she’s claiming revolutionary stuff, it is a shame because no one can check what she wrote.

If you have printed this article, shred it.

25 notes

·

View notes