#mandarin moribund

Text

“Many factors can interrupt successful language transmission, but it is rarely the result of free will. The decision tends to be made by the very youngest speakers, 6- and 7-year-olds, under duress or social pressure, and these children then influence the speech behavior of adults in the community. These youngest speakers—acting as tiny social barometers—are acutely sensitive to the disfavored status of their elders’ language and may choose to speak the more dominant tongue. Once this happens, the decision tends to be irreversible. A language no longer being learned by children as their native tongue is known as ‘moribund’. Its days are numbered, as speakers grow elderly and die and no new speakers appear to take their places.” — K. David Harrison, When Languages Die

When I was in third grade (in the US), I stopped speaking Sichuanese. My mother forced me to use it at home because she didn’t want me to “forget Chinese”.

In college I visited my family in Sichuan and met the elementary school age child of a cousin (born & raised in Sichuan). The child refused to speak Sichuanese with us because it wasn’t “proper Chinese” (mandarin). Her mother did not correct her. She wanted her child to “learn Chinese.”

To this day, most Chinese people I meet are only mildly surprised by my ability to speak fluent mandarin despite growing up in the US, but every single one of them was absolutely floored when they realized my Sichuanese was better than my mandarin.

I think they were astonished that when my Chinese identity was “under threat” from my anglophone American childhood environment, my mother chose to rescue Sichuanese, her own mother tongue, instead of “proper Chinese” mandarin.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 8th Mori Art Museum and Maid Cafe ACADEMIC INDEPENDENT EXCURSION

Source: https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00001044/65-86_ESTABLISHING-OKINAWAN-HERITAGE-LANGUAGE-EDUCATION_43-Heinrich_Sugita-6.pdf

Today, I went to a maid cafe and the Mori art museum. I think that these were both eye-opening cultural experiences. One of the exhibits in the Mori Art Museum, “Lost and Found” focused on endangered languages. Artist Susan Hiller found speakers of various endangered languages, and had them reflect in their native tongue on the loss of each language, anecdotes from their lives, and songs in their languages. The languages included Livonian, Wichita, N/uu, among others. I found this particularly compelling. In Japan especially, the supremacy of Standard Japanese has rendered local dialects, and Okinawan languages (which are as distinct from Japanese as English is to German) moribund. In Okinawa particularly, U.S. occupation of those islands until 1972 probably hastened the death of those languages because Okinawan unification movements used their identification with Standard Japanese as a political cudgel to dislodge Okinawa from its status as an unincorporated U.S. territory.

In each language lies the essence and system of values of the People that speak it. When we lose an entire language, we do not just lose a method of communication, but a piece of humanity. So, it strikes me as a good thing that since the 1980’s there has been a revival movement of Japanese dialects, and Okinawan languages. Japanese dialects have seen renewed interest, as Japan attempts to recreate a sense of identity in a postmodern world. Japanese dialects make each place in Japan unique, and imbue every city with its own local flare that can no longer be usurped or suppressed by the mandarins in Tokyo.

When speaking of language death, often the main reason a language dies is because it is being displaced by another. That has been the case in Okinawa for the last 140 years or so. There, since the Meiji period until the end of WWII, the Japanese government tried unify the country under Standard Japanese, and discouraged the usage of dialects. People in Okinawa could be punished for speaking their languages out loud in public.

I have now read from a variety of scholarly works regarding Okinawan languages. Most of them suggest that the top down assimilation of Okinawa into Standard Japanese was not very successful until the early part of the 20th century. It was after WWII when Okinawa was rebuilt into a modern society, and Okinawan activism clinged to a Japanese sense of identity that language transfer was interrupted between the Older bi-lingual generation, and the Generations after. Most people below about age 60 in Okinawa do not speak their heritage language.

However, some scholars suggest that Okinawan Heritage Language education can save these languages. But Okinawans will need to decide how they would like their language to live on across the islands for any successful program to be implemented. This may differ across the archipelago. There are more than six distinct Ryukyuan languages, with various numbers of remaining native speakers. Okinawa has the most, and remote Yonaguni has just over 300 elderly speakers left. If they fail to implement this, these languages will likely die within the next 20-30 years.

I think linguists around the world should do everything they can to promote the use of endangered languages, or at least document them while we still can. As the world has continued to globalize, and the power of just a handful of languages continues to grow stronger, we should recall that in each language lives something special worth preserving. They are all worth preserving.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

登机牌 [dēng jī pái] - boarding pass

Mandarin

0 notes

Quote

不行 【bù xíng】- no good; poor; incapable; incompetent

Mandarin Moribund

#mandarin moribund#chinese moribund#chinese#moribundmurdoch#不行#no good#harris murdoch#murdoch maxwll#murdoch maxwell

0 notes

Text

原谅 (yuán liàng) - to forgive

#原谅#yuán liàng#to forgie#to forgive#moribundity#yugen v. the moribundity#the moribundity#moribundmurdoch#moribund institute#mandarin vocabulary#chinese vocabulary

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“what language should I learn?”

“is it better to learn [x] or [x]?”

“is it worth learning [x]?”

I get this type of question a lot and I see questions like these a lot on language learning forums, but it’s very difficult to answer because ultimately language learning is a highly personal decision. Passion is required to motivate your studies, and if you aren’t in love with your language it will be very hard to put in the time you need. Thus, no language is objectively better or worse, it all comes down to factors in your life. So, I’ve put together a guide to assist your with the kind of factors you can consider when choosing a language for study.

First, address you language-learning priorities.

Think of the reasons why are you interested in learning a new language. Try to really articulate what draws you to languages. Keeping these reasons in mind as you begin study will help keep you focused and motivated. Here are some suggestions to help you get started, complete with wikipedia links so you can learn more:

Linguistic curiosity?

For this, I recommend looking into dead, literary or constructed languages. There are lots of cool linguistic experiments and reconstructions going on and active communities that work on them! Here’s a brief list:

Dead languages:

Akkadian

Egyptian (Ancient Egyptian)

Gaulish

Gothic

Hittite

Old Prussian

Sumerian

Older iterations of modern day languages:

Classical Armenian

Classical Nahuatl (language of the Aztec Empire)

Early Modern English (Shakespearean English)

Galician-Portuguese

Middle English (Chaucer English)

Middle Persian/Pahlavi

Old English

Old French

Old Spanish

Old Tagalog (+ Baybayin)

Ottoman Turkish

Constructed:

Anglish (experiment to create a purely Anglo-Saxon English)

Esperanto

Interlingua

Láadan (a “feminist language”)

Lingua Franca Nova

Lingwa de Planeta

Lobjan

Toki Pona (a minimalist language)

Wenedyk (what if the Romans had occupied Poland?)

Cultural interests?

Maybe you just want to connect to another culture. A language is often the portal to a culture and are great for broadening your horizons! The world is full of rich cultures; learning the language helps you navigate a culture and appreciate it more fully.

Here are some popular languages and what they are “famous for”:

Cantonese: film

French: culinary arts, film, literature, music, philosophy, tv programs, a prestige language for a long time so lots of historical media, spoken in many countries (especially in Africa)

German: film, literature, philosophy, tv programs, spoken in several Central European countries

Italian: architecture, art history, catholicism (Vatican city!), culinary arts, design, fashion, film, music, opera

Mandarin: culinary arts, literature, music, poetry, tv programs

Japanese: anime, culinary arts, film, manga, music, video games, the longtime isolation of the country has developed a culture that many find interesting, a comparatively large internet presence

Korean: tv dramas, music, film

Portuguese: film, internet culture, music, poetry

Russian: literature, philosophy, spoken in the Eastern Bloc or former-Soviet countries, internet culture

Spanish: film, literature, music, spoken in many countries in the Americas

Swedish: music, tv, film, sometimes thought of as a “buy one, get two free” deal along with Norwegian & Danish

Religious & liturgical languages:

Avestan (Zoroastrianism)

Biblical Hebrew (language of the Tanakh, Old Testament)

Church Slavonic (Eastern Orthodox churches)

Classical Arabic (Islam)

Coptic (Coptic Orthodox Church)

Ecclesiastical Latin (Catholic Church)

Ge’ez (Ethiopian Orthodox Church)

Iyaric (Rastafari movement)

Koine Greek (language of the New Testament)

Mishnaic Hebrew (language of the Talmud)

Pali (language of some Hindu texts and Theravada Buddhism)

Sanskrit (Hinduism)

Syriac (Syriac Orthodox Church, Maronite Church, Church of the East)

Reconnecting with family?

If your immediate family speaks a language that you don’t or if you are a heritage speaker that has been disconnected, then the choice is obvious! If not, you might have to do some family tree digging, and maybe you might find something that makes you feel more connected to your family. Maybe you come from an immigrant community that has an associated immigration or contact language! Or maybe there is a branch of the family that speaks/spoke another language entirely.

Immigrant & Diaspora languages:

Arbëresh (Albanians in Italy)

Arvanitika (Albanians in Greece)

Brazilian German

Canadian Gaelic (Scottish Gaelic in Canada)

Canadian Ukrainian (Ukrainians in Canada)

Caribbean Hindustani (Indian communities in the Caribbean)

Chipilo Venetian (Venetians in Mexico)

Griko (Greeks in Italy)

Hutterite German (German spoken by Hutterite settlers of Canada/US)

Fiji Hindi (Indians in Fiji)

Louisiana French (Cajuns)

Patagonian Welsh (Welsh in Argentina)

Pennsylvania Dutch (High German spoken by early settlers of Canada/ the US)

Plaudietsch (German spoken by Mennonites)

Talian (Venetian in Brazilian)

Texas Silesian (Poles in the US)

Click here for a list of languages of the African diaspora (there are too many for this post!).

If you are Jewish, maybe look into the language of your particular diaspora community ( * indicates the language is extinct or moribund - no native speakers or only elderly speakers):

Bukhori (Bukharan Jews)

Hebrew

Italkian (Italian Jews) *

Judeo-Arabic (MENA Jews)

Judeo-Aramaic

Judeo-Malayalam *

Judeo-Marathi

Judeo-Persian

Juhuri (Jews of the Caucasus)

Karaim (Crimean Karaites) *

Kivruli (Georgian Jews)

Krymchak (Krymchaks) *

Ladino (Sephardi)

Lusitanic (Portuguese Jews) *

Shuadit (French Jewish Occitan) *

Yevanic (Romaniotes)*

Yiddish (Ashkenazi)

Finding a job?

Try looking around for what languages are in demand in your field. Most often, competency in a relevant makes you very competitive for positions. English is in demand pretty much anywhere. Here are some other suggestions based on industry (from what I know!):

Business (General): Arabic, French, German, Hindi, Korean, Mandarin, Russian, Spanish

Design: Italian (especially furniture)

Economics: Arabic, German

Education: French, Spanish

Energy: Arabic, French, German, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish

Engineering: German, Russian

Finance & Investment: French, Cantonese, German, Japanese, Mandarin, Russian, Spanish

International Orgs. & Diplomacy (NATO, UN, etc.): Arabic, French, Mandarin, Persian, Russian, Spanish

Medicine: German, Latin, Sign Languages, Spanish

Military: Arabic, Dari, French, Indonesian, Korean, Kurdish, Mandarin, Pashto, Persian, Russian, Spanish, Turkish, Urdu

Programming: German, Japanese

Sales & Marketing: French, German, Japanese, Portuguese

Service (General): French, Mandarin, Portuguese, Russian, Sign Languages, Spanish

Scientific Research (General): German, Japanese, Russian

Tourism: French, Japanese, Mandarin, Sign Languages, Spanish

Translation: Arabic, Russian, Sign Languages

Other special interests?

Learning a language just because is a perfectly valid reason as well! Maybe you are really into a piece of media that has it’s own conlang!

Fictional:

Atlantean (Atlantis: The Lost Empire)

Dothraki (Game of Thrones)

Elvish (Lord of the Rings)

Gallifreyan (Doctor Who)

High Valyrian (Game of Thrones)

Klingon (Star Trek)

Nadsat (A Clockwork Orange)

Na’vi (Avatar)

Newspeak (1984)

Trigedasleng (The 100)

Vulcan (Star Trek)

Or if you just like to learn languages, take a look maybe at languages that have lots of speakers but not usually popular among the language-learning community:

Arabic

Bengali

Cantonese

Hindi

Javanese

Hausa

Indonesian

Malay

Pashto

Persian

Polish

Punjabi

Swahili

Tamil

Telugu

Thai

Turkish

Urdu

Vietnamese

Yoruba

If you have still are having trouble, consider the following:

What languages do you already speak?

How many and which languages you already speak will have a huge impact on the ease of learning.

If you are shy about speaking with natives, you might want to look at languages with similar consonant/vowel sounds. Similarity between languages’ grammars and vocabularies can also help speed up the process. Several families are famous for this such as the Romance languages (Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Romanian), North Germanic languages (Norwegian, Swedish, Danish) or East Slavic languages (Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian). If you are a native English speaker, check out the FSI’s ranking of language difficulty for the approximate amount of hours you’ll need to put into different languages.

You could also take a look at languages’ writing systems to make things easier or for an added challenge.

Another thing to remember is that the languages you already speak will have a huge impact on what resources are available to you. This is especially true with minority languages, as resources are more frequently published in the dominant language of that area. For example, most Ainu resources are in Japanese, most Nheengatu resources are in Portuguese, and most Nahuatl resources are in Spanish.

What are your life circumstances?

Where you live with influence you language studies too! Local universities will often offer resources (or you could even enroll in classes) for specific languages, usually the “big” ones and a few region-specific languages.

Also consider if what communities area near you. Is there a vibrant Deaf community near you that offers classes? Is there a Vietnamese neighborhood you regularly interact with? Sometimes all it takes is someone to understand you in your own language to make your day! Consider what languages you could realistically use in your own day-to-day. If you don’t know where to start, try checking to see if there are any language/cultural meetups in your town!

How much time can you realistically put into your studies? Do you have a fluency goal you want to meet? If you are pressed for time, consider picking up a language similar to ones you already know or maintaining your other languages rather than taking on a new one.

Please remember when choosing a language for study to always respect the feelings and opinions of native speakers/communities, particularly with endangered or minoritized languages. Language is often closely tied to identity, and some communities are “closed” to outsiders. A notable examples are Hopi, several Romani languages, many Aboriginal Australian languages and some Jewish languages. If you are considering a minoritized language, please closely examine your motivations for doing so, as well as do a little research into what is the community consensus on outsiders learning the language.

#o#writing this post took a long time but it was really fun!!#langblr#language learning#choosing a language

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

uneducated follower here; could you elaborate on "leaving indigenous religion alone mostly so as to prop up the colonial state"? how did that work? i thought colonizers mostly just spread their own religions to colonies. how did leaving indigenous religions intact prop up colonizers? sorry aha

(Anon is in response to this and this post)

First off something to get out of the way is that colonialism is a historical phenomenon which means that it is not uniform thing. Colonialism in the sense of imperialism is about controlling a population and the means by which a colonial power exerts this control can range from expulsion or genocide of the native populace to be replaced by settlers or it could take the form of granting nominal sovereignty to a neo-colonial state where all the official offices are occupied by local people but the true masters of remain the same old ones.

So what Spain and Portugual did in the 16th and 17th centuries isnt necessarily gonna match the patterns of the British and French in the 19th and 20th centuries. So whereas the Portuguese in India exported their style of religious persecution to Goa in the form of the Goa Inquisition, the British East India Company actually had refused British missionaries access to territories they controlled up until 1813 on the grounds that missionaries might spoil relations with local rulers or merchants friendly with the EIC.

Despite propaganda that might seem to the contrary the purpose of prosthelyization in Spanish or Portuguese colonies was not purely out of a desire to turn the whole world Catholic. Just because Catholicism might see it as an ideal that the whole world be turned Catholic doesnt on its own necessitate that Catholic states would pursue such a policy because there is also an ideal of peace between fellow Christians that obviously Catholic states could care less about. There needs to be a pragmatic reason why to go through all that trouble. The most obvious reason for this is that converting the indigenous to the colonial religion you better pacify them by turning something they turn to in hours of suffering and grief into a thing that legitimizes and props up the colonial state. An additional way this helps control a population is that churches end up filling the role of an official registry of the names of people in various areas via baptismal certificates or other means. And of course in many cases the colonial state was itself the Church or at least controlled by it.

Anyway I just spent a paragraph seeming to argue the opposite point so whats up with colonial powers granting sanction to local religions out of self-interest? Well the answer is that there was growing realization that in many cases the local religions could actually fulfill the above roles just as well and frankly with much less struggle. If you could get local religious leaders to sanction and bless your rule and preach submission to it well all the better then. In the case of India, the British highly valued winning over the loyalty of local religious leaders of whatever was the dominant local faith because these religious leaders would then legitimize British rule and in turn the British would reward them for their loyalty. French colonialism in Indochina (ironically enough given that it primarily occurred during the Third Republic) often took the form of trying to preserve indiginous cultural practices that otherwise appeared moribund such as the Emperorship or the mandarinate because they believed this would be the superior way to legitimize their rule if they used the already-in-place forms of legitimizing state authority (not to mention the Third Republic had a.. contentious relationship with the Roman Catholic Church which is why there wasnt that much Catholic missionary work done in “New Imperialism” colonies as you might expect and French colonial authorities would sometimes trust indigenous or even non-French Protestant religious figures moreso than Catholic ones because of how hostile relations between the Catholic Church and the Third Republic could get).

Conversion can still occur of course but it tends to take the form of allowing independent churches to do what they will do. The flipside is that these native clerics can be harder to control and the sighs of the oppressed could more easily turn subversive than when compared with colonial religions but those are problems that have solutions from the perspective of a colonial administrator. The Javanese communist Tan Malaka is noteworthy for being a Marxist who disagreed with the political goal of eventual abolition of religion and had believed that religious clerics could be allies in the struggle against imperialism because in the Dutch East Indies he had cooperated with clerics for such reasons. But when he returned after a trip to Russia, Malaka was shocked to see how many of his former friends had turned around after Dutch colonial authorities had given them (”them” being the clerics, not the common people) some concessions such as control over schooling of native youths. This caused Malaka to shift his thinking such that while he remained a Muslim, he became convinced that present-day clergy will need to be abolished in order for religion to itself be revolutionized.

The late 19th century pan-Islamic intellectual Jalal al-Din al-Afghani was as far from a “colonial collaborator” as you could get being the zealous and implacable enemy of British imperialism that he was but there was one interesting incident wherein he attempted to make a “deal with the devil” so to speak. In 1885 al-Afghani traveled to London on invitation of the poet Wilfrid Blunt who was also his friend to meet with Randolph Churchill, Secretary of State for India. Al-Afghani made a rather blunt proposal to Churchill, namely that if the British were to grant independence to Egypt so that it may be a prominent Muslim country free of European (which includes Ottoman) domination then al-Afghani would use his immense prestige and and sway over anti-colonial movements in the Muslim world to preach alliance with the British and jihad against the Russians, their main rival in Central Asia and potentially South Asia as well (al-Afghani would also make similar overtures to Russia). Now dont let this influence your idea of al-Afghani the man because that was a life that was incredibly nuanced and fascinating to read about but these dynamics he proposed are what I want to point out.

Now a nuance that needs to be mentioned of course is that this is dependent on the societal role of religion and religious hierarchies prior to colonialism. Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya has an idiosyncratic definition of the word “theism” that I think might be useful here. For Chattopadhyahya “theism” refers not to the abstract belief in a divinity or even a personal divinity but rather the form this takes within societies marked by economic classes. This is relevant because if youre talking about tribes with more egalitarian social arrangements then its less likely that there will be a priestly class that can be won over in the same way. This both made conversion through missionaries not only easier because they werent competing with pre-existing organized religions but also greatly increased the usefulness in the colonial state sponsoring such endeavors. So again to bring up Indonesia but if you look at a map of religious affiliation in the country you’d see the widest concentration of Christian majorities is in the Indonesian-controlled part of New Guinea and if you look at the pre-colonial history of New Guinea there was much much less of a presence of class-determined religion in Chattopadhyahya’s sense of “theism”.

Anyway that was a ramble but the point is that don’t get too hung up on the idea of colonialism having a specific paradigm. When you think of the perspective of a colonial administrator who is trying to protect a regime of brutality, exploitation and bloodshed they have to act in what is the immediately pragmatic self-interest for the regime. Thus depending on the social circumstances (and frankly increasingly so overtime) there may be a move away from conversion of locals towards collaboration with local clerics. Force alone is not enough to maintain a state

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

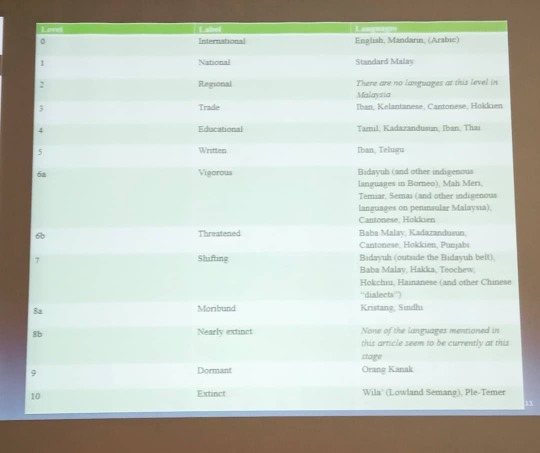

“Language Vitality In Malaysia”

We were in KL yesterday for these talks about indigenous languages. Missed the first two (damn you, KL traffic!) - but the one we did catch was enlightening.

+

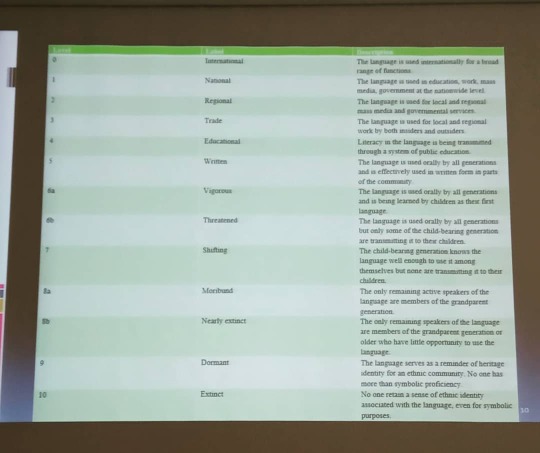

Paolo Coluzzi, from UM's Linguistics school, presented the "Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale" (EGIDS), a 13-point framework to roughly gauge a language's health.

Iban and Kelantanese are influential "Trade" languages. Bidayuh and Temiar are "Vigorous"- still in heavy oral use, and transmitted from parents to children. Kristang is "Moribund"- only the grandparent generation speaks it; once they are gone it is lost.

+

Why do languages die?

Folks move to the big city. They speak BM or English for work. Or they marry outside their language community- inevitably the household language tends towards BM, the language both partners know.

Underlying these specifics is the general logic of nationalism. "We are one nation, we should speak one language." The architecture of Malaysian education enforces that.

As well as the logic of modernity. The veneer of prestige that languages like English or Mandarin have - cultural sophistication; global-economic advantage. City languages. What's the utility of learning a kampung language like Baba Malay, in the face of *those*?

+

Paolo: "The only way would be to try and deconstruct the ideology of the 'new' and modernity, to expose its irrationality and its limits with clarity, and to highlight the positive aspects of tradition and the small-scale economy that used to be part of it."

+

There was a short Q&A afterwards. Folks were engaged. There were artists and activists from the indigenous community, linguists, students:

"There are five different kinds of Bidayuh. Which will be taught in the classroom, if the language is taught in school?"

"The issue is that when research begins, the language is already dying ..."

"You can start small. Write down the words your family uses, their meanings. Record your grandparents' stories. Start now."

"Don't think that, just because you are not Orang Asli, you cannot or should not learn these languages, or focus your research on them. We need everybody!

+

The sense that apocalypse is here - but there *is* space on the boat for you, and we need as many hands as we can get to row.

+

The talks were part of the Centre for Malaysian Indigenous Studies’ “Voices of the People” show -- an exhibition about indigenous languages in Malaysia.

Art. Lots and lots of stories. Videos of folks talking about their daily lives, in Semelai and Che Wong and Mah Meri.

Here’s a animated short of the Sang Kancil & Sang Buaya story, narrated in Temuan:

🐊🐊🐊

How to cross a river via crocodile. The Sang Kancil and Sang Buaya story, narrated in Temuan!

🐀🦌🐀

At the Centre for Malaysian Indigenous Studies, Universiti Malaya. #indigenousstudies #crocodilestudies pic.twitter.com/VZZot8n3MP

— Zedeck Siew (@zedecksiew) October 5, 2019

You should go for this exhibition. It is lovely, and very moving.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seamus Deane, Heroic Styles: The Tradition of an Idea [Field Day Pamphlet, No. 4] (Derry: Field Day 1984).

It would be foolhardy to choose one among the many competing variations [ways of reading - Irish literature and history - Romanticism, Victorianism, Modernism; Idealist, Radical, Liberal] and say that it is true on some specifically historical or literary basis. Such choices are always moral and/or aesthetic [5].

What I propose […] is that there have been for us two dominant ways of reading both our literature and our history. One is “Romantic”, a mode of reading which takes pleasure in the notion that Ireland is a culture enriched by the ambiguity of its relationship to an anachronistic and a modernist present [sic]. The other is a mode of reading which denies the glamour of this ambiguity and seeks to escape from it into a pluralism of the present. The authors who represent these modes most powerfully are Yeats and Joyce respectively. The problem which is rendered insoluble [5] by them is the North. In a basic sense, the crisis we are passing through is stylistic. That is to say, it is a crisis of language - the ways in which we write it and the ways in which we read it. In a culture like ours, ‘tradition’ is too easily taken to be an established reality. We are conscious that it is an invention, a narrative which ingeniously finds a way of connecting a selected series of historical figures or themes in such a way that the pattern or plot reveal to us becomes a conditioning factor in our reading of literary works. (p.5-6.)

A poem like “Ancestral Houses” owed its force to the vitality with [which] it offers a version of Ascendancy history as true in itself. The truth of this historical reconstruction of the Ascendancy is not cancelled by our simply saying No, it was not like that. For its ultimate validity is mythical, not historical. In this case, the mythical element is given prominence by the meditation on the fate of an originary energy which becomes so effective that it transforms nature into civilisation, and is then transformed itself by civilisation into decadence. The poem, then, appears to have a story to tell, and, along with that, an interpretation of the story’s meaning. It operates on the narrative and on the conceptual planes and at the intersection of these it emerges, for many readers, as a poem about the tragic nature of human existence itself. Yeats’s life, through the mediations of history and myth, becomes an embodiment of essential existence.

The trouble with such a reading is the assumption that this or any other literary work can arrive at a moment in which it takes leave of history or myth (which are liable to idiosyncratic interpretation) and becomes meaningful only as an aspect of the ‘human condition’. This is, of course, a characteristic determination of humanist readings of literature which hold to the ideological conviction that literature, in its highest forms, is non-ideological. It would be perfectly appropriate, within this particular frame, to take a poem by Pearse - say, “The Rebel” - and to read it in the light of a story - the Republican tradition from Tone, the Celtic tradition from Cuchulainn, the Christian tradition from Colmcille - and then reread the story as an expression of the moral supremacy of martyrdom over oppression. But as a poem, it would be regarded as inferior to that of Yeats. Yeats, stimulated by the moribund state of the [6] Ascendancy tradition, resolves, on the level of literature, a crisis which, for him, cannot be resolved socially or politically. In Pearse’s case, the poem is no more than an adjunct to political action. The revolutionary tradition he represents is not broken by oppression but renewed by it. His symbols survive outside the poem, in the Cuchulainn statue, in the reconstituted GPO, in the military behaviour and rhetoric of the IRA. Yeats’s symbols have disappeared, the destruction of Coole Park being the most notable, although even in their disappearance one can discover reinforcement for the tragic condition embodied in the poem. The unavoidable fact about both poems is that they continue to belong to history and to myth; they are part of the symbolic procedures which characterise their culture. Yet, to the extent that we prefer one as literature to the other, we find ourselves inclined to dispossess it of history, to concede to it an autonomy which is finally defensible only on the grounds of style.

The consideration of style is a thorny problem. In Irish writing, it is particularly so. When the language is English, Irish writing is dominated by the notion of vitality restored, of the centre energised by the periphery, the urban by the rural, the cosmopolitan by the provincial, the decadent by the natural. This is one of the liberating effects of nationalism, a means of restoring dignity and power to what had been humiliated and suppressed. This is the idea which underlies all our formulations of tradition. Its development is confined to two variations. The first we may call the variation of adherence, the second of separation. In the first, the restoration of native energy to the English language is seen as a specifically Irish contribution to a shared heritage. Standard English, as a form of language or as a form of literature, is rescued from its exclusiveness by being compelled to incorporate into itself what had previously been regarded as a delinquent dialect. It is the Irish contribution, in literary terms, to the treasury of English verse and prose. Cultural nationalism is thus transformed into a species of literary unionism. Sir Samuel Ferguson is the most explicit supporter of this variation, although, from Edgeworth to Yeats, it remains a tacit assumption. The story of the spiritual heroics of a fading class - the Ascendancy - in the face of a transformed Catholic ‘nation’ - was rewritten in a variety of ways in literature - as the story of the pagan Fianna replaced by a pallid Christianity, of young love replaced by old age (Deirdre, Oisin), of aristocracy supplanted by mob-democracy. The fertility of these rewritings is all the more remarkable in that they were recruitments by the fading class of the myths of renovation which belonged to their opponents. Irish culture became the new property of those who were losing their grip on [7] Irish land. The effect of these rewritings was to transfer the blame for the drastic condition of the country from the Ascendancy to the Catholic middle classes or to their English counterparts. It was in essence a strategic retreat from political to cultural supremacy. From Lecky to Yeats and forward to F. S. L. Lyons we witness the conversion of Irish history into a tragic theatre in which the great Anglo-Irish protagonists — Swift, Burke, Parnell — are destroyed in their heroic attempts to unite culture of intellect with the emotion of multitude, or in political terms, constitutional politics with the forces of revolution. The triumph of the forces of revolution is glossed in all cases as the success of a philistine modernism over a rich and integrated organic culture. Yeats’s promiscuity in his courtship of heroic figures — Cuchulainn, John O’Leary, Parnell, the 1916 leaders, Synge, Mussolini, Kevin O’Higgins, General O’Duffy— is an understandable form of anxiety in one who sought to find in a single figure the capacity to give reality to a spiritual leadership for which (as he consistently admitted) the conditions had already disappeared. Such figures could only operate as symbols. Their significance lay in their disdain for the provincial, squalid aspects of a mob culture which is the Yeatsian version of the other face of Irish nationalism. It could provide him culturally with a language of renovation, but it provided neither art nor civilisation. That had come, politically, from the connection between England and Ireland.

All the important Irish Protestant writers of the nineteenth century had, as the ideological centre of their work, a commitment to a minority or subversive attitude which was much less revolutionary than it appeared to be. Edgeworth’s critique of landlordism was counterbalanced by her sponsorship of utilitarianism and “British manufacturers”; Maturin and Le Fanu took the sting out of Gothicism by allying it with an ethic of aristocratic loneliness; Shaw and Wilde denied the subversive force of their proto-socialism by expressing it as cosmopolitan wit, the recourse of the social or intellectual dandy who makes [8] such a fetish of taking nothing seriously that he ceases to be taken seriously himself. Finally, Yeats’s preoccupation with the occult, and Synge’s with the lost language of Ireland are both minority positions which have, as part of their project, the revival of worn social forms, not their overthrow. The disaffection inherent in these positions is typical of the Anglo-Irish criticism of the failure of English civilisation in Ireland, but it is articulated for an English audience which learned to regard all these adversarial positions as essentially picturesque manifestations of the Irish sensibility. In the same way, the Irish mode of English was regarded as picturesque too and when both language and ideology are rendered harmless by this view of them, the writer is liable to become a popular success. Somerville and Ross showed how to take the middle-class seriousness out of Edgeworth’s world and make it endearingly quaint. But all nineteenth-century Irish writing exploits the connection between the picturesque and the popular. In its comic vein, it produces The Shaughran and Experiences of an Irish R.M.; in its Gothic vein, Melmoth the Wanderer, Uncle Silas and Dracula; in its mandarin vein, the plays of Wilde and the poetry of the young Yeats. The division between that which is picturesque and that which is useful did not pass unobserved by Yeats. He made the great realignment of the minority stance with the pursuit of perfection in art. He gave the picturesque something more than respectability. He gave it the mysteriousness of the esoteric and in doing so committed Irish writing to the idea of an art which, while belonging to “high” culture, would not have, on the one hand, the asphyxiating decadence of its English or French counterparts and, on the other hand, would have within it the energies of a community which had not yet been reduced to a public. An idea of art opposed to the idea of utility, an idea of an audience opposed to the idea of popularity, an idea of the peripheral becoming the central culture - in these three ideas Yeats provided Irish writing with a programme for action. But whatever its connection with Irish nationalism, it was not, finally, a programme of separation from the English tradition. His continued adherence to it led him to define the central Irish attitude as one of self-hatred. In his extraordinary “A General Introduction for my Work” (1937), he wrote:

“The ‘Irishry’ have preserved their ancient ‘deposit’ through wars which, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, became wars of extermination; no people, Lecky said ... have undergone greater persecution, nor did that persecution altogether cease up to our own day. No people hate as we do in whom that past is always alive ... Then I [9] remind myself that remind myself that though mine is the first English marriage I know of in the direct line, all my family names are English, and that I owe my soul to Shakespeare, to Spenser and to Blake, perhaps to William Morris, and to the English language in which I think, speak, and write, that everything I love has come to me through English - my hatred tortures me with love, my love with hate … . This is Irish hatred and solitude, the hatred of human life that made Swift write Gulliver and the epitaph upon his tomb, that can still make us wag between extremes and doubt our sanity.”

The pathology of literary unionism has never been better defined.

The second variation in the development of the idea of vitality restored [viz., separation] is embodied most perfectly in Joyce. His work is dominated by the idea of separation as a means to the revival of suppressed energies. The separation he envisages is as complete as one could wish. The English literary and political imperium, the Roman Catholic and Irish nationalist claims, the oppressions of conventional language and of conventional narrative - all of these are overthrown, but the freedom which results is haunted by his fearful obsession with treachery and betrayal. In him, as in many twentieth century writers, the natural ground of vitality is identified as the libidinal. The sexual forms of oppression are inscribed in all his works but, with that, there is also the ambition to see the connection between sexuality and history. His work is notoriously preoccupied with paralysis, inertia, the disabling effects of society upon the individual who, like Bloom, lives within its frame, or, like Stephen, attempts to live beyond it. In Portrait the separation of the aesthetic ambition of Stephen from the political, the sexual and the religious zones of experience is clear. It is, of course, a separation which includes them, but as oppressed forces which were themselves once oppressive. His comment on Wilde is pertinent:

Here we touch the pulse of Wilde’s art - sin. He deceived himself into believing that he was the bearer of good news of neo-paganism to an enslaved people ... But if some truth adheres ... to his restless thought ... at its very base is the truth inherent in the soul of Catholicism: that man cannot reach the divine heart except through that sense of separation and loss called sin.”

In Joyce himself the sin is treachery, sexual or political infidelity. [10] The betrayed figure is the alien artist. The ‘divine heart’ is the maternal figure, mother, Mother Ireland, Mother Church or Mother Eve. But the betrayed are also the betrayers and the source of the treachery is in the Irish condition itself. In his Trieste lecture of 1907, “Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages”, he notes that Ireland was betrayed by her own people and by the Vatican on the crucial occasions of Henry II’s invasion and the Act of Union: “From my point of view, these two facts must be thoroughly explained before the country in which they occurred has the most rudimentary right to persuade one of her sons to change his position from that of an unprejudiced observer to that of a convicted nationalist.” / Finally, in his account of the Maamtrasna murders of 1882 in “Ireland at the Bar” (published in Il Piccolo della Sera, Trieste, 1907), Joyce, anticipating the use which he would make throughout Finnegans Wake of the figure of the Irish-speaking Myles Joyce, judicially murdered by the sentence of an English-speaking court, comments: “The figure of this dumb-founded old man, a remnant of a civilisation not ours, deaf and dumb before his judge, is a symbol of the Irish nation at the bar of public opinion.” This, along with the well-known passage from Portrait [viz., ‘my soul frets in the shadow of his language", Portrait of An Artist, Chap. 5] in which Stephen feels the humiliation of being alien to the English language in the course of his conversation with the Newman Catholic Dean of Studies, identifies Joyce’s sense of separation from both Irish and English civilisation. Betrayed into alienation, he turns to art to enable him overcome the treacheries which have victimised him.

In one sense, Joyce’s writing is founded on the belief in the capacity of art to restore a lost vitality. So the figures we remember are embodiments of this “vitalism”, particularly Molly Bloom and Anna Livia Plurabelle. The fact that they were women is important too, since it clearly indicates some sort of resolution, on the level of femaleness, of what had remained implacably unresolvable on the male level, whether that be of Stephen and Bloom or of Shem and Shaun. This vitalism announces itself also in the protean language of these books, in their endless transactions between history and fiction, macro- and microcosm. But along with this, there is in Joyce a [11] recognition of a world which is “void” (a favourite word of his), even though it is also full of correspondence, objects, people. … His vitalism is insufficient to the task of overcoming this void. [... &c.]

Yeats was indeed our last romantic in literature as was Pearse in politics. They were men who asserted a coincidence between the destiny of the community and their own and believed that this coincidence had an historical repercussion. This was the basis for their belief in a “spiritual aristocracy” which worked its potent influence in a plebian world. Their determination to restore vitality to this lost society provided their culture with a millenial conviction which has not yet died.’ Whatever we may thing of their ideas of tradition, we still adhere to the tradition of the idea that art and revolution are definitively associated in their production of any individual style [12] which is also the signature of the community’s deepest self. [… &c.]’ (pp.12-13.)

There is a profoundly insulting association in the secondary literature surround him that he is eccentric because of his Irishness but serious because o his ability to separate himself from it. In such judgements, we see the ghost of a rancid colonialism. But it is important to recognise that this ghost haunts the works themselves. the battle between style as the expression of communal history … and Joycean stylism, in which the atomisation of community is registered in a multitude of equivalent, competing styles, in short, a battle between Romantic and contemporary Ireland.’ [Goes on to apply these ideas to the crisis in Northern Ireland.] (p.13.)

Joyce, although he attempted to free himself from set political positions, did finally create in Finnegans Wake a characteristically modern way of dealing with heterogenous and intractable material and experience. The pluralism of his styles and languages, the absorbent nature of his controlling myths and systems, finally gives a certain harmony to varied experience. But, it could be argued, it is a harmony of indifference, one in which everything is a version of something else, where sameness rules over diversity, where contradiction is finally and disquietingly written out. In achieving this in literature, Joyce anticipated the capacity of modern society to integrate almost all antagonistic elements by transforming them into fashions, fads - styles, in short. (Ibid., p.16.)

There is, therefore, nothing mysterious about the re-emergence in literature of the contrast which was built into the colonial structure of the country. But to desire, in the present conditions in the North, the final triumph of State over nation, Nation over State, modernism over backwardness, authenticity over domination, or any other comparable liquidation of the standard oppositions, is to desire the utter defeat of the other community. The acceptance of a particular style of Catholic or Protestant attitudes or behaviours, married to a dream of final restoration of vitality to a decayed cause or community, is a contribution to the possibility of civil war. It is impossible to do without ideas of a tradition. But it is necessary to disengage from the traditions of the ideas which the literary revival and the accompanying political revolution sponsored so successfully. (p.16.)

Although the Irish political crisis is, in many respects, a monotonous one, it has always been deeply engaged in the fortunes of Irish writing at every level, from the production of work to its publication and reception. The oppressiveness of the tradition we inherit has its source in our own readiness to accept the mystique of Irishness as an inalienable feature of our writing and, indeed, of much else in our culture. That mystique is itself an alienating force. To accept it is to become involved in the [17] spiritual heroics of a Yeats or a Pearse, to believe in the incarnation of the nation in the individual. To reject it is to make a fetish of exile, alienation, dislocation in the manner of Joyce or Beckett. [...] They inhabit the highly recognisable world of modern colonialism. (p.18.)

One step towards that dissolution [of the mystique] would be a revision of our prevailing idea of what it is that constitutes the Irish reality. In literary that could take the form of a definition, in the form of a comprehensive anthology, of what writing in this country has been for the last 300-500 years and, through that, an exposure to the fact that the myth of Irishness, the notion of Irish unreality, the notion surrounding Irish eloquence, are all political themes upon which the literature has battened to an extreme degree since the nineteenth century when the idea of national character was invented. The Irish national character [...] has been received as the verdict passed by history upon the Celtic personality. That stereotyping has caused a long colonial concussion. It is about time we put aside the idea of the essence - that hungry Hegelian ghost looking for a stereotype to live in. As Irishness or as Northerness he stimulates the provincial unhappiness we create and fly from, becoming virtuoso metropolitans to the exact degree that we have created an idea of Ireland as provincialism incarnate. These are worn oppositions. They used to be parentheses in which the Irish destiny was isolated. That is no longer the case. Everything has to be rewritten - i.e., re-read. that will enable new writing, new politics, unblemished by Irishness, but securely Irish.’ (pp.17-18; end.)

#seamus deane#field day#james joyce#w.b. yeats#irish literature#irish culture#ireland#postcolonial theory#words#favorites

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on the success & decline of civilisations, colonialism & civil conflict: USA/Europe, China & Africa

This is not so much a coherent article, but more of a collection of ideas and criticisms of past policies across world history.

I've always stood by the idea that the strengths of Western civilisation that brought its success between 1500-1900 has proven to be its weaknesses since that period in today's political climates.

Altruism, entrepreneurship, individualism incorporated within communitarianism, innovation, courage and creativity are just a few virtues that made Western civilization great, but has also become something that is now hurting USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. The West has hit its peak and is now in its age of decadence and decline.

On the topic of colonialism, UK, Portugal, Spain & France spread their influence on a massive global scale. Whilst Italy & Germany did colonize with lesser success, it's safe to say the third world still looks towards the West for ideas and innovation in 2019.

I will admit I'm not an expert on European civilisations' relationship with Jews (apart from expelling said tribe hundreds of times), but somewhere down the line it seems Europeans (and possibly Jews) failed to foresee the future birth rates of non-white populations such as Hispanics, Arabs, Black Africans & Indians, which have been skyrocketing since 1900. Meanwhile white European & east Asian birth rates have slowed down massively since the 1990s, due to the success of peace treaties, industrial success, improving standards of living and the comfort of first world standards. With infant mortality at an extremely low level in the first world, that urge for women to produce endless numbers of children in the western/east Asian world has plummeted to below replacement levels of 2.4 babies per woman- in some nations such as Germany, just 1.2 babies.

A mistake made by western colonialists pre-1900 was to try to integrate the New World (Americas), tribal Africa & aboriginal Australia into the western way of living. The white male troops should have been banned from breeding children with the local women; instead, the native populations should have been isolated and cordoned off into their own living lands. In addition, the use of slave labour by the colonialists should've been restricted. The colonialists should have then captured the lands which possessed minerals, natural resources and living land area in Africa. This land area should have then been populated with white Europeans- in particular, western colonialists should have focused on capturing land areas in southern Africa, where countries such as modern South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Angola & Mozambique exist today. These lands should have been established and divided as white-only nation-states, with any blacks attempting to enter these provinces expelled as illegal aliens breaching borders (or killed on sight if necessary). Likewise the indigenous populations of the Americas and Australia should have isolated and left to their own living areas; again, any of them trying to enter white-only areas should have been dealt with immediate expulsion.

As for the importation of Black African slave labour, the numbers of slaves brought to the USA should been much fewer in number (i.e. 25% of the original total). Therefore it would've been much easier to return the black slaves to Africa during the early 19th century, when the decreasing profit margins gained from slave labour was making this practice moribund. This would have avoided the unnecessary American Civil War of 1861-1865, which facilitated the early foundations of today's Federal Reserve. (In addition, European colonialists could've expelled black slaves located in the Caribbean during this time to place more white people here.)

Instead, the European colonialists should have instigated a mass breeding program for white people during 1500-1900 in order to facilitate a mass white population re-distribution of southern Africa, the modern Arab states of Asia & Africa, Canada, USA, Mexico Australia & South America. In the topic of the Arab world, had the whites succeeded in invading modern Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya & Algeria, there would be a huge white populous in northern Africa. This would mean the Muslim Arabs would be probably now be living on the border areas of Mali, Niger, Chad & Sudan, with blacks pushed further south to the central Africa.

As for the mainly British colonialism of south Asia (such as India & Hong Kong), there's not much for me to say. As there was little land space for the Brits to move the Indians around, it was always going to the case that the British colonised India for economic purposes mostly. It's tempting to think the British could've sterilised the Indians, but frankly that would've seen a civil war between the British colonizers and the native population, with the Brits expelled en masse. As for Hong Kong, the region's economic and political freedoms post-1949 (when the Communists took over and created "Peoples' Republic of China") allowed ethnic Han Chinese to immigrate to that region in large numbers to escape the Cultural Revolution. For those who think Hong Kong is nothing but a British paper tiger, Hong Kong survived the invasion of the Japanese during WW2 and escaped with its traditional infrastructure unscathed.

On the topic of China, I believe the presence of warlords constantly fighting each other throughout this nation-empire's history to be a major mistake. The 1700s saw the Qing dynasty rise to become the richest "nation/empire" in the world, so the end result was a population that never felt like they needed to improve their lot in life. The ideas of Transatlantic exploration was non-existent, leaving imperial China vulnerable to colonialist invasions by the British & the Portuguese, plus the French & the Germans temporarily colonized parts of southern and northern China's seaport towns (France had some power over parts of Yunnan, Guangxi, Hainan & Guangdong, whilst Germany captured Qingdao- hence why Tsingtao beer exists!) during the 19th century.

A huge mistake of Chinese emperors & warlords was to continually fight each other for land, possessions and ultimate ruling control within modern China's land area. Had any of the many Chinese tribes within the area had at least attempted to depart China in order to explore the New World, Africa & Australia pre-1900, the decline of imperial China's hegemony within the world would have not proved as problematic for its citizenry as it eventually became in the 20th century. Instead, China could have split up into 5 to 15 separate nations, with each region's languages and customs (Cantonese, Hokkien, Hakka etc.) being preserved, with Mandarin (only 400 years old, having originated from the Manchus) taking a far less of a dominant presence in today's Sinosphere.

What's more, the Han Chinese should have left the Tibetans and the Uyghurs alone to their own land areas and focused instead on conquering lands outside of Asia. Had the Han Chinese succeeded in doing this, there might've been nation-states in the Americas, Africa & perhaps parts of Australia which would have a majority Chinese population today. Instead, just like the Europeans, the Chinese are on the precipice of witnessing their ethnic populations decline massively in the 21st century and becoming dominated by other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, it was a mistake by European colonialists in failing to attempt some sort of birth-rate restriction on the indigenous populations in the new world, Africa & Australia. Had the colonialists succeeded in pushing down the numbers of Hispanics, Arabs & Africans (and possibly the Indians) right into the late 20th century at least, the impending demographic apocalypse of whites (& possibly East Asians) would not be so severe in this coming 21st century. Not only was it clearly a mistake for Europeans & Americans to accept centralised banking during the late 19th/early 20th century and to become involved in two world wars, but they should've practiced isolationism with the third world. Essentially, the Europeans & Americans should've focused on fighting the instigators of Communist takeover in Russia, which would have restricted the amount of influence that the banking cartels & Jews have on today's socio-economic-political landscape.

On the subject of PRC China's "economic colonialism" in modern Africa, the issues lie within how much longer can the Chinese communist party continue to plough money and resources into Africa, only to receive little return. As the local Africans cannot afford to pay debts for new railways, utilities and other buildings, the Chinese will start to run low on manpower. Although the Chinese have built new facilities in Africa & Pacific island nations, they've done so with their own ethnic Chinese workers, but refused to give many employment opportunities to the local populous within these regions. As China's birthrate continues to plummet, China is now becoming a victim of its own success (just like the West)- as the current Chinese citizens will now increasingly demand better jobs, living conditions and political rights.

Now when I've talked about the world we live in now being one that demands social and economic equality, I never stated it was a good thing as some believed. I merely stated it was part of the new world order despite myself being aware that equality is a lie. I believe there will be a socio-political backlash from Africa & the Pacific in coming years against China's "economic colonialism", whilst China's own slowing growth will see internal issues within its nation and the Communist party struggling to hold onto power.

The only real solutions I can see for nationalists within Europe and western nations is for a huge percentage of the population to start protesting the political and economic institutions en masse immediately. Make them abandon their jobs, live off the grid, collect rainwater & develop their own independent technology. Civil unrest can also be an option, but I'm not entirely sure whether the West could be resurrected from the ruins of a massively expensive civil and intercontinental war.

However, options such as secession of states from the USA should be kept on the table. Encourage a re-distribution of various ethnic groups to divide themselves into certain areas of the States, so that dividing the USA into separate ethnic enclaves can be done as peacefully as possible.

As for China, only a major economic collapse can make its citizens rise up against the criminal Communist party, but also for the populous to agree upon splitting up the nation for every region's benefits and needs. In addition, this will restore trust, peace and security to neighbouring nations such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam & the Philippines.

As for Europe: end the European Union.

As for Australia, Canada & New Zealand: wake up to the threat of Chinese buying up property and start learning Cantonese (not Mandarin) to irritate the Han Mandarin supremacists from mainland China.

So I would everyone on Pocketnet to think deeply about the past, the present & the future of the West, but to respect differing opinions here. Thank you.

0 notes

Text

您贵姓?

Nín guì xìng?

Your name?

Your honorable surname?

#nin gui xing#moribundmurdoch#chuisimoduoke#questions chinese#mandarin moribund murdcoh#ef shang hao#shang hai ef

0 notes

Quote

黑发 【hēifǎ】- dark-haired

Mandarin Moribund

0 notes

Photo

在里面一个韩国剧“W” [더블유] 有一个人物是不会射快因为他想要完美地击中目标.

Zài lǐmiàn yīgè hánguó jù “W” [deobeul-yu] yǒu yīgè rénwù shì bù huì shè kuài yīnwèi tā xiǎng yào wánměi dì jí zhòng mùbiāo.

Inside a Korean drama "W" [더블유] There is a character who can't shoot fast because he wants to hit the target perfectly.

#kdrama#moribundmurdoch#mandarin moribund#mandarin ccm#ccm chinese#elementary chinese#moribund murdoch#murdoch maxwell#murodch harris#murdoch harris#maxwell murdoch#w

0 notes

Photo

我是非常好羽毛球运动员。

Wǒ shì fēicháng hǎo yǔmáoqiú yùndòngyuán.

I am a very good badminton player.

#mandarin#mandarin moribund#chinese#chinese moribund#ccm#county college morris#county college of morris#community college#school murdoch#murdoch harris#murdoch maxwell#badminton#newton

0 notes

Photo

我的弟弟是一名初级奥林匹克游泳运动员。

Wǒ de dìdì shì yī míng chūjí àolínpǐkè yóuyǒng yùndòngyuán

My brother is a junior Olympic swimmer.

#moribundmurdoch#chinese#mandarin moribund#mandarin#ccm mandarin#ccm chinese#ccm moribundmurdoch#communty college#county college of morris#moribund murdoch#murdoch harris#harris murdoch#murdoch maxwell

0 notes

Photo

我的沙特阿拉伯朋友人和我。我们是排球神,但我们的团队才不呢 好.

Wǒ de shātè ālābó péngyǒu rén hé wǒ. Wǒmen shì páiqiú shén, dàn wǒmen de tuánduì cái bù ne hǎo.

My Saudi Arabian friend and me. We are volleyball gods, but our team is not good.

#mandarin#murdoch ccm#ccm murdoch#ccm#community college#moribund murdoch#murdoch maxwell#maxwell murdoch#mandarin moribund

0 notes