#marguerite d'anjou

Photo

· HISTORICAL WOMEN IN ARMOUR ·

Alicia Borrachero as ISABEL I DE CASTILLA

The Spanish Princess (2019-2020) · By Phoebe De Gaye

Sophie Okonedo as MARGUERITE D'ANJOU

The Hollow Crown (2016) · By Nigel Egerton

Gina Mckee as CATERINA SFORZA

The Borgias (2011-2013) · By Gabriella Pescucci

Laura Morgan as JEANNE D'ARC

The Hollow Crown (2016) · By Nigel Egerton

Cate Blanchett as ELIZABETH I

Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007) · By Alexandra Byrne

#the spanish princess#thespanishprincessedit#tspedit#the hollow crown#thehollowcrownedit#thcedit#the borgias#theborgiasedit#elizabeth the golden age#elizabethedit#isabel i de castilla#isabella i of castille#marguerite d'anjou#margaret of anjou#caterina sforza#jeanne d'arc#joan of arc#elizabeth i#elizabeth i of england#alicia borrachero#sophie okonedo#gina mckee#laura morgan#cate blanchett#mine#costume#costumes#whew a lot to tag#women tag

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

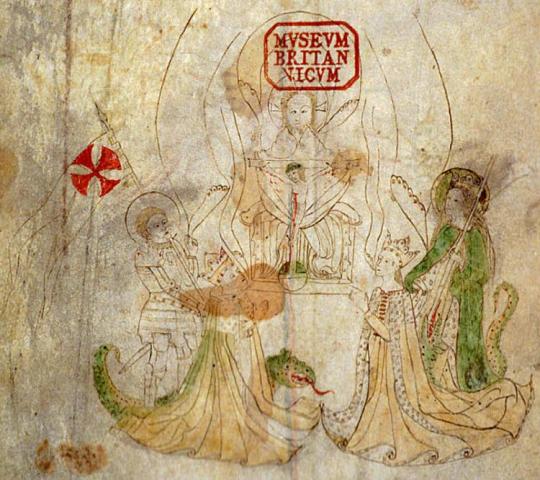

This museum identified this ivory plaque as Margaret of Anjou.

#margaret of anjou#marguerite d'anjou#middle ages#medieval#fifteenth century#i don't know of this is accurate#shredsandpatches#henry vi

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

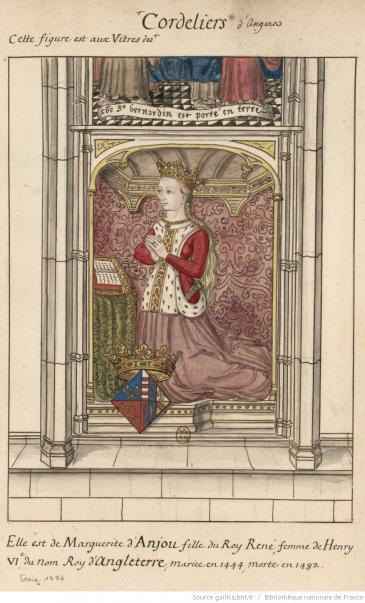

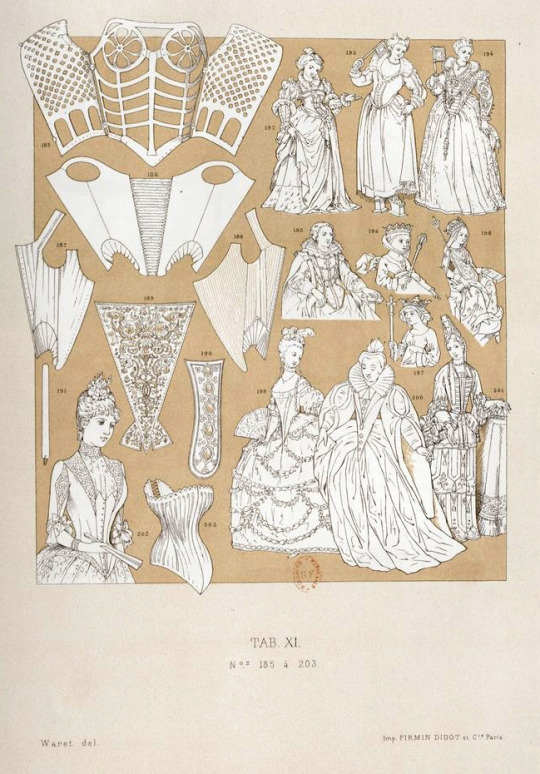

Icon representations of Queen Margaret of England throughout History.

#margaret of anjou#queen margaret#plantagenet dynasty#plantagenet#plantagenet consort#queen of england#wars of the roses#house of lancaster#marguerite d'anjou#iconography#medieval england

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝘚𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘰𝘧 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘧𝘢𝘷𝘰𝘶𝘳𝘪𝘵𝘦 𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘦𝘯𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘳𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘵 𝘩𝘪𝘴𝘵𝘰𝘳𝘺.

#Emma of Normandy#Katheryn Winnick#Eleanor of Provence#Naomi Watts#Marguerite de Provence#Margaret of Provence#Rebecca Ferguson#Joanna of Navarre#Joan of Navarre#Eleanor of Portugal#Eleanor of Avis#Holy Roman Empress#Empress Eleanor#Marguerite d'Anjou#Margaret of Anjou#Queen Margaret#Sophie Turner#Elizabeth of York#Elizabeth Plantagenet#Queen Elizabeth#Sophia Myles#Anne of Brittany#Anna de Bretagne#Queen Anne#La reine Anne#la bonne reine anne#Scarlett Johanson#Maria of Trastamara#Maria of Aragon#Maria of Castille

48 notes

·

View notes

Quote

And on the Monday after noon the Queen came to him, and brought my Lord Prince with her. And then he asked what the Prince's name was, and the Queen told him Edward; and then he held up his hands and thanked God thereof. And he said he never knew him till that time, nor wist not what was said to him, nor wist not where he had be whiles he hath be sick till now. And he asked who was godfathers, and the Queen told him, and he was well apaid.

Edmund Clere to John Paston I, 9 January 1455 (Firsthand description of Henry VI's meeting his infant son for the first time after coming out of his "catatonic state" [unknown illness which remains a mystery])

#The Paston Letters#I love reading other people's mail#Especially when it gives me adorable tidbits about Henry VI meeting his baby son#Henry VI#Queen Margaret#Margaret of Anjou#Marguerite d'Anjou#Edward of Westminster#Edward of Lancaster#Edward Prince of Wales#Edmund Clere#John Paston I#9 January 1455

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

『 ♛ 𝘓𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘳𝘪𝘢𝘯𝘴 𝘘𝘶𝘦����𝘯𝘴 𝘰𝘧 𝘌𝘯𝘨𝘭𝘢𝘯𝘥 ♛ 』

(𝟣𝟦𝟢𝟥-𝟣𝟦𝟨𝟣)

1. 𝑁𝑎𝑜𝑚𝑖 𝑊𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑠 𝑎𝑠 𝐽𝑜𝑎𝑛𝑛𝑎 𝑜𝑓 𝑁𝑎𝑣𝑎𝑟𝑟𝑎, 𝑄𝑢𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑜𝑟𝑡 𝑡𝑜 𝐾𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐻𝑒𝑛𝑟𝑦 𝐼𝑉.

2.𝐶𝑙𝑒́𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒 𝑃𝑜𝑒́𝑠𝑦 𝑎𝑠 𝐾𝑎𝑡𝘩𝑒𝑟𝑖𝑛𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑉𝑎𝑙𝑜𝑖𝑠, 𝑄𝑢𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑜𝑟𝑡 𝑡𝑜 𝐾𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐻𝑒𝑛𝑟𝑦 𝑉.

3. 𝐷𝑎𝑖𝑠𝑦 𝑅𝑖𝑑𝑙𝑒𝑦 𝑎𝑠 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑡 𝑜𝑓 𝐴𝑛𝑗𝑜𝑢, 𝑄𝑢𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑠𝑜𝑟𝑡 𝑡𝑜 𝐾𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐻𝑒𝑛𝑟𝑦 𝑉𝐼.

#House of Lancaster#Lancaster#Lancastrians#Plantagenets#Plantagenet Dynasty#Queens consorts#Lancastrians queens#Queen Joanna#Queen Katherine#Queen Margaret#Joanna of Navarra#Joan of Navarra#Jeanne de Navarre#Jeanne d'Évreux#Jeanne de Bretagne#Katherine of Valois#Katherine de Valois#Margaret of Anjou#Marguerite d'Anjou#red queens#Naomi Watts#Clémence Poésy#daisy ridley#fan cast#edit

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tʜᴇ AU·s I·ᴅ ʟɪᴋᴇ ᴛᴏ sᴇᴇ﹐ ᴘᴀʀᴛ II ﹕Mᴀʀɢᴀʀᴇᴛ ᴏғ Aɴᴊᴏᴜ﹐ ᴛʜᴇ ᴠɪᴄᴛᴏʀɪᴏᴜs ϙᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ.

[ 𝑆𝑜𝑝𝘩𝑖𝑒 𝑇𝑢𝑟𝑛𝑒𝑟 𝑎𝑠 𝑦𝑜𝑢𝑛𝑔𝑒𝑟 𝑞𝑢𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑡;

𝐶𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝐵𝑙𝑎𝑛𝑐𝘩𝑒𝑡𝑡𝑒 𝑎𝑠 𝑜𝑙𝑑𝑒𝑟 𝑞𝑢𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑀𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑎𝑟𝑒𝑡]

#Alternative Universe#plots#AU storylines#AU history#Margaret of Anjou#Queen Margaret#Marguerite d'Anjou#Queen of England#House of Lancaster#King Henry VI#Henry VI#Sophie Turner#as#young Margaret#Cate Blanchette#as older#Margaret#Chris Pine#as king#Henry#Charlotte Hope#as Margaret#firstly duchess of suffolk#secondly queen of england#loved this really

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Marguerite had been ill since she set out from Paris several weeks before, progressing slowly toward the coast while distributing Lenten alms, making propitiatory offerings at each church where she heard mass, dining with dignitaries, and saying good-bye one by one to her relations along the way. Slowly, though, in the days after her arrival in England, she recovered her health in a series of Sussex convents amid the sounds and scents of the church’s rituals, with all their reassuring familiarity.

On April 10, the records of the royal finances show a payment of 69s 2d* to one “Master Francisco, the Queen’s physician” who provided “divers aromatic confections, particularly and specially purchased by him and privately made into medicine for the preservation of the health of the lady.”

If Suffolk’s first concern had been to find a convent where Marguerite could be nursed, his second was to summon a London dressmaker to attend her, before the English nobility caught sight of her shabby clothes. Again, the financial records tell the tale: 20s, on April 15, to one Margaret Chamberlayne, dessmaker, or “tyre maker’, as it was then phrased. Among the various complaints the English were preparing to make of their new queen, one would be her poverty.

Before Marguerite’s party set out toward the capital, there was time for something a little more courtly, if one Italian contemporary, writing to the Duchess of Milan three years later, was to be believed. As Englishman had told him that when the queen landed in England, the king had secretly taken Marguerite a letter, having first dressed himself as a squire. “While the queen read the letter the king took stock of her”, the correspondent wrote, “saying that a woman may be seen very well when she reads a letter, and the queen never found out it was the king because she was so engrossed in reading the letter, and she never looked at the king in his squire’s dress, who remained on his knees at the time.”

It was the same trick Henry VIII would play on Anne of Cleves almost a century later, a game from the Continental tradition of chivalry. But this time it ended more happily. When Marguerite, afterward, was told of the premise, she was vexed at having paid the supposed squire no attention. But she must at least have reflected that there was nothing noticeably repulsive about her twenty-three-year-old bridegroom, and nothing intimidating either. And Henry VI, if the Milanese writer is to be believed, saw “a most handsome woman, though somewhat dark”-and not, the Milanese tactfully assured his duchess, “so beautiful as your Serenity”.

(The Englishman, he reported, ‘told me that his mistress was wise and charitable, and your Serenity has the reputation equally wise and more charitable. He said that his queen had an income of 80,000 gold crowns’)

At the French court, Marguerite had already acquitted herself well enough to win an admirer in the courtly tradition, Pierre de Brézé, to carry her colors at the joust and to move the Burgundian chronicler Barante to write that she was “already renowned in France for her beauty and wit and her lofty spirit of courage”.”

From: “Blood Sisters: The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses.” Sarah Gristwood.

#Marguerite d'Anjou#Queen Margaret#Margaret of Anjou#House of Lancaster#House of Anjou#Plantagenet dynasty#Plantagenets#wars of the roses

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles of Anjou and his brothers.

King Louis had been notably generous. Perhaps the decision that Charles should become count of Anjou had been made before the chance of the marriage arose, and Louis thought it inexpedient to change his mind once his brother had acquired Provence. On the other hand, the king may have anticipated positive benefits to the kingdom from his gift. The energetic young Charles might be counted on to oppose any attempt at reconquest by the English, and to undermine any surviving Breton influence in the area. Besides, Louis clearly did not regard his brothrs as potential rivals; if he had done so, he would not have encouraged Alphonse to expand beyond his core county of Poitou to take the Limousin under his authority; nor would he have planned Alphonse's marriage to the daughter of the count of Toulouse, a marriage which in 1249 brought him the huge county of Toulouse and part of the old marquisate of Provence to add to his already substantial holdings. In this case Louis must have been confident that he could exercise his authority over his sibling when need be. The same was probably true for Charles, whose lands within France were far smaller than Alphonse's.

Nevertheless, the enfeoffment of 1246 was a substantial endowment at the expense of the royal demesne [...]

From the end of 1246, therefore, Charles had the resources and position to begin to make his mark on western Europe by demanding the recognition of his rights, real or pretended, in every sphere. Although he continued to feel grateful to Louis for his vital assistance to his career, there was frequently an element of tension in his relations with his eldest surviving brother. Louis's position marked him out as one who must be obeyed; Charles by temperament was one to whom obedience came hard. Louis sometimes complained of Charles's insensitivity. Joinville painted a vivid picture of the king's sudden fury on discovering, as he sailed away defeated from Egypt in 1250 and in mourning for the death of his brother Robert, that Charles, far from attempting to comfort him, was playing dice with a friend. Given the temperamental differences between them, occasional signs of strain after 1246 were only to be expected.

Yet historians have been prone to exaggerate them. It is alleged that Louis forced Charles to surrender the county of Hainault, which Marguerite, countess of Flanders, had conferred on him in 1253. Louis is usually portrayed as reluctant to endorse the papal plan of sending Charles to conquer Sicily, while Charles is seen as desperate to get his hands on that rich realm. Neither picture is clearly supported by the evidence.

[...]

The most potent sources of friction were those that Charles inherited from his father-in-law Raymond Berengar V of Provence. The claimed monopoly on the salt trade up the Rhône deeply aggravated Louis, as did Charles's failure to pay up in full Margaret of Provence's dowry [...]

Though Louis did not particularly like Charles, he trusted him. He coupled him with Alphonse as regent of the realm when Blanche of Castille died in 1252. He entrusted them both with tricky negotiations with Henry III and Innocent IV in 1251. In arbitrating between Charles and his mother-in-law Beatrice of Savoy in 1256, the king substantially enhanced his brother's political power in Provence by obtaining for him the county of Forcalquier, in return for a pension to Beatrice which Louis himself paid. He seems to have prevented his wife Margaret, Beatrice's daughter, from causing trouble to his brother in Provence. He intervened in Anjou to acquire for Charles a castle that the younger man regarded as crucial to his power. These were not the actions of a saintly king who disapproved of his headstrong younger brother's conduct; nor were they acts of mere indulgence.

It is clear that Charles benefited substantially in the eyes of outsiders from his close relationship with Louis. His opponents in Provence and Italy feared possible French intervention in his support, and were therefore on occasion moved to treat with him rather than continuing the fight. [...] Louis IX's favour was worth having, and those who helped Charles expected to win it. This expectation argues against the tensions between the two brothers from being significant.

[...]

More striking was Charles's consistent friendship with Alphonse. For much of Louis's reign, the brothers worked together. It is true that there was the occasional spat of irritation between them when Alphonse's acquisition of the county of Toulouse made him Charles's neighbour in Provence; Charles was deeply hurt that Alphonse would not in 1264-65 commute his vow to go again to the Holy Land into service in the conquest of the Regno. But for the most part their interests were compatible. Together they subjected Avignon and the old marquisate of Provence to Capetian interests. Together they strengthened their holds on their respective domains by refusing to shelter each other's rebels. Together they pursued claims against Louis to the inheritance of the countess of Boulogne and the count of Clermont. When Alphonse fell ill in the Regno on his way back from the Tunis crusade, Charles demanded that the best medical help available in Naples be sent at once to him. His brother's death in 1271 must have come as a bitter blow.

None of his other male relations came near to equalling Alphonse's influence. But throughout his life, Charles looked to his nephews and cousins for backing and positive military support. His son-in-law Robert de Béthune was a pillar of his government in the Regno during the early years, his nephews Robert d'Artois and Pierre d'Alençon rushed to his assistance in 1282-83. He remained a family man until death, and a man who took great pride in his closest kin.

This characteristic is perhaps most evident in his testimony, probably in 1282, to a papal enquiry into the canonization of Louis. Charles talked of his family as the holy root from which sprang saintly branches; he argued that both Robert (who died on crusade) and Alphonse (who aspired to meet such a death) were as worthy as Louis of being elevated to the status of martyrs for the faith. For him, sanctity was a family trait, enhanced in his generation by excellent upbringing. Obviously this testimony was far from disinterested. But his slant on his eldest brother's claim to be canonized is noteworthy. After all, as a crowned head himself, Charles might have made more of Louis as God's representative on earth, or of the royal anointing as a kind of sacrament. He ignored the opportunity to contribute to the cult of kings, in favour of an encomium on the Capetians.

Jean Dunbabin- Charles I of Anjou- Power, Kingship and State-Making in Thirteenth-Century Europe.

#xiii#jean dunbabin#charles i of anjou: power kingship and state-making#charles i d'anjou#louis ix#alphonse de poitiers#robert i d'artois#marguerite de provence#béatrice de savoie#robert de béthune#pierre d'alençon#brothers#family feelings

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Respected and admired at the time of her death, over the centuries Catherine’s youngest daughter has come to be regarded as a sensual dilettante who put her own romantic inclinations ahead of her duty to the kingdom. Today she is remembered - if she is known at all - as the sympathetic but ultimately tragic heroine of Alexandre Dumas’s classic novel La Reine Margot.

But even Dumas’s portrayal, favorable though it may be, fails to give Marguerite’s intelligence and courage their due. It has become commonplace to suggest that a historical figure anticipated modern attitudes, but in Margot’s case this happens to be true. Here, hundreds of years before the advent of the feminist movement, was a strong, spirited, resolute individual unafraid to confront sexual mores. It is for this reason more than any other that her reputation has been systematically denigrated. Her desire to love and be loved - her willingness to engage in a series of passionate affairs - has overshadowed every other aspect of her life. This is especially ironic considering the licentious nature of her surroundings. By any measure the carnality attributed to her brothers and her husband dwarfs the queen of Navarre’s sensual experiences. And although Catherine de’ Medici cannot be accused personally of wanton behavior, she clearly encouraged it in others in order to gain political advantage. Alone among her family, Marguerite refused to use sex as a weapon and searched only for love.

But the queen of Navarre was so much more than the sum of her affairs. Acutely aware of the vulnerability of the position forced upon her by her marriage, Marguerite nonetheless steadfastly refused to accept victimhood and instead strove throughout her life to carve out a measure of independence and influence for herself. To an astounding degree, considering the variety and potency of the forces ranged against her, she succeeded. The political ascension of her brother François may be traced directly to his sister’s participation in and sponsorship of his interests. Although painted as a scapegoat for the kingdom’s woes by her family, Marguerite in fact consistently counseled peace between Catholics and Huguenots and presided over one of the very few courts in Europe where, at least briefly, religious tolerance was officially sanctioned. She only took up arms as a last resort when compelled to do so in her own self-defense. And she was invaluable to Henry IV, both as a political symbol and as an advocate, in helping to secure his rule and that of his successors after the death of her brother Henri III.

But for her inability to conceive a child, Marguerite might have gone down in history, as Henry IV did, as one of the great French rulers. Instead she is simply Queen Margot, who saved her husband - and by extension, the whole kingdom. ‘I have no ambition and I have no need of it,” she once wrote, “being who and what I am.’

The Rival Queens: Catherine de’ Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois, and the Betrayal That Ignited a Kingdom

#author: nancy goldstone#marguerite de valois#catherine de medici#henri iii#henri iv de navarre#françois duc d'alençon#françois duc d'anjou#i know this is a really long quote - it’s the last page and a half of the book but I couldn’t find a good place to cut it and keep the gist

16 notes

·

View notes

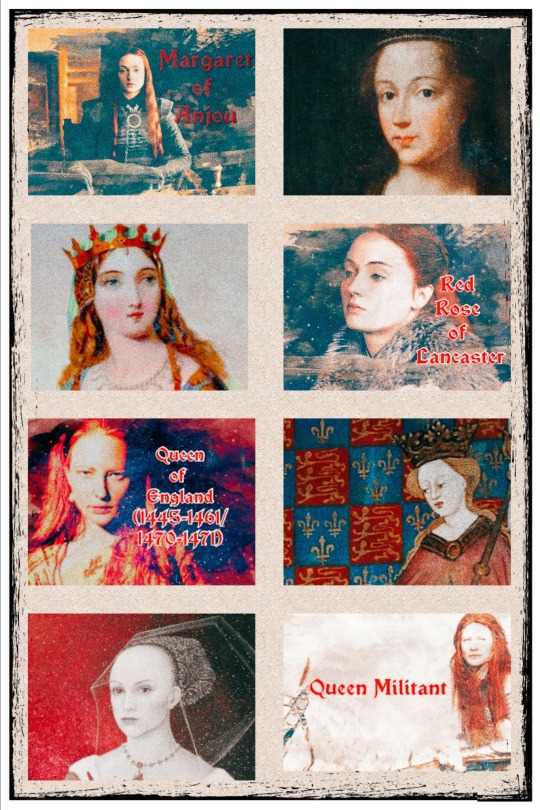

Photo

Tab. XI. Nos 185 à 203. Les Corsets.

Le costume historique, by Albert Racinet. Paris, 1888. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Tab. XI. Les Corsets.

185. Italian Busto, iron corset. Framework lined with velvet. Venetian. Photographic document.

186. Duchess corset body, front, with shoulder straps and basques, laced in front. (Encyclopédie; le tailleur de corps.)

187, 188, 191. French corset, open front. Boned with solid bones and transverse dressage bones, shoulder straps and basques. 187: half-whale; 188: solid ribs; 191: whale busk, used in pairs; slipped into the front, on each side, with a loop for removal. (Encyclopédie.)

190. Goldsmith's breastplate adorned with pearls and jewels, early 16th century. Ms. 7232, Bibl. nat.

192. Figure after Jost Amman, wearing a hooked corset, the point of which pointed forwards, 16th century.

193 & 194. Figures after César Vecellio, late 16th century; Venetians mounted on skates (Tab. X: 156, 157, 162, 163). Busto corset, advances while being prolonged, and in such a way as to form the false belly. (See about these ladies pl. 289.)

195. Lady of the Netherlands, after Van Dyck; Medici bodice.

196 & 197. Figures by Michel Wolgemut in the Chronicle of Nuremberg, 1493, showing the use of the corset by the curve of the body.

198. Marie d'Anjou, wife of Charles VII, receiving in 1455 the homage of a book, which is another example, going back earlier, of the obvious use of the corset walking with the arch of the loins. From the Twelve Perilz of Hell, Ms. de la Bibl. of the Arsenal.

199. Lady-in-Waiting to Queen Marie-Antoinette, after Moreau the Younger.

200. Marriage of Joyeuse, Marguerite de Vaudemont, 1581. Louvre.

201. Lady, late 17th century, after Bonnard.

202. Figure from La Mode illustrée, No. 9, 27 February 1887.

203. Cuirass-corset, with steel blades.

Le costume historique. Cinq cents planches, trois cents en couleurs, or et argent, deux cents en camaïeuTypes principaux du vêtement et de la parure rapproches de ceux de l'intérieur de l'habitation dans tous les temps et chez tous les peuples, avec de nombreux détails sur le mobilier, les armes, les objets usuels, les moyens de transport, etc. Recueil publié sous la direction de m. A. Racinet, auteur de l'ornement polychrome, avec des notices explicatives, une introduction générale, des tables et un glossaire. Paris, Librairie de Firmin-Didot et Cie. Imprimeurs de l'Institut, 56, rue jacob, 56. 1888. Droits de traduction et de reproduction réservés. Bibliothèque nationale de France

#Le costume historique#19th century#1800s#1880s#1888#publication#illustration#fashion#Bibliothèque nationale de France#corset#16th century#17th century#15th century#dress#busto#venetian#french#italian#plastron#van dyck#medici#Wolgemut

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

· QUEEN MARGUERITE D'ANJOU ·

— Sophie Okonedo · The Hollow Crown (2012–2016)

· QUEEN CHARLOTTE OF MECKLENBURG-STRELITZ ·

— Golda Rosheuvel · Bridgerton (2020–)

· QUEEN ANNE BOLEYN ·

— Jodie Turner-Smith · Anne Boleyn (2021)

#bridgerton#bridgertonedit#the hollow crown#thehollowcrownedit#anne boleyn 2021#anneboleynedit#sophie okonedo#golda rosheuvel#jodie turner-smith#marguerite d'anjou#margaret of anjou#queen charlotte#anne boleyn#perioddramaedit#diversehistorical#weloveperioddrama#perioddramasource#onlyperioddramas#mine#women tag

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Joan of Arc: I'm portrayed as a warmongering witch!

Richard III: I'm an evil hunchback who murders eighteen people!

Marguerite d'Anjou: That's nothing! I have an affair and commit war crimes

Henry VII: You guys are getting enough characterisation to be villainised?

I think I'm funny

Heee, true! Though of course, Henry VII's situation is not as dire as the other characters cited here, he's just boring(™) and underdeveloped. It kind of highlights how Shakespeare wasn't simply writing Tudor propaganda.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dieu...et mon droit.

#Margaret of Anjou#Queen Margaret of Anjou#Queen Margaret#Marguerite d'Anjou#Royne Marguerite d'Angleterre#Queen Margaret of England#house of Lancaster#Lancaster#Wars of the Roses#Cousin's Wars#Henry VI#consort#queen consort#lancaster consort#lancastrian consorts#lancaster edit#plantagenet edit#house of plantagenet#house plantagenet#plantagenet dynasty#sophie turner#cate blanchette

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fᴀᴠᴏᴜʀɪᴛᴇ ʀᴏʏᴀʟs ᴀɴᴅ ᴛʜᴇɪʀ sᴛᴀʀ sɪɢɴs (1):﹕

₁. Aʀɪᴇs﹕ Mᴀʀɢᴜᴇʀɪᴛᴇ ᴅ·Aɴᴊᴏᴜ/Mᴀʀɢᴀʀᴇᴛ ᴏғ Aɴᴊᴏᴜ﹐ Qᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ ﹙₂₃ Mᴀʀᴄʜ ₁₄₃₀﹣₂₅ Aᴜɢᴜsᴛ ₁₄₈₂﹚

₂. Tᴀᴜʀᴜs﹕ Lᴏᴜɪs IX﹐ Kɪɴɢ ᴏғ Fʀᴀɴᴄᴇ ﹙₂₅ Aᴘʀɪʟ ₁₂₁₄﹣₂₅ Aᴜɢᴜsᴛ ₁₂₇₀﹚.

₃. Gᴇᴍɪɴɪ﹕ Aɴɴᴇ Nᴇᴠɪʟʟᴇ﹐ Qᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ. ﹙₁₁ Jᴜɴᴇ ₁₄₅₆﹣₁₆ Mᴀʀᴄʜ ₁₄₈₅﹚.

₄. Cᴀɴᴄᴇʀ﹕ Mᴀʀɪᴀ ᴏғ Cᴀsᴛɪʟʟᴇ ᴀɴᴅ Aʀᴀɢᴏɴ﹐ Qᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Pᴏʀᴛᴜɢᴀʟ. ﹙₂₉ Jᴜɴᴇ ₁₄₈₂﹣₇ Mᴀʀᴄʜ ₁₅₁₇﹚.

₅. Lᴇᴏ﹕ Hᴀʀᴛʜᴀᴄɴᴜᴛ﹐ Kɪɴɢ ᴏғ Dᴇɴᴍᴀʀᴋ ᴀɴᴅ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ ﹙ʙᴏʀɴ Jᴜʟʏ/Aᴜɢᴜsᴛ ₁₀₁₈﹣₈ Jᴜɴᴇ ₁₀₄₀﹚.

₆. Vɪʀɢᴏ﹕ Eʟɪᴢᴀʙᴇᴛʜ I﹐ Qᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ ﹙₇ Sᴇᴘᴛᴇᴍʙᴇʀ ₁₅₃₃﹣₂₄ Mᴀʀᴄʜ ₁₆₀��﹚.

₇. Lɪʙʀᴀ﹕ Hᴇɴʀʏ III﹐ Kɪɴɢ ᴏғ Eɴɢʟᴀɴᴅ ﹙₁ Oᴄᴛᴏʙᴇʀ ₁₂₀₇﹣₁₆ Nᴏᴠᴇᴍʙᴇʀ ₁₂₇₂﹚.

₈. Sᴄᴏʀᴘɪᴏ﹕ Oʟɢᴀ Nɪᴋᴏʟᴀᴇᴠɴᴀ Rᴏᴍᴀɴᴏᴠᴀ﹐ Gʀᴀɴᴅ Dᴜᴄʜᴇss ᴏғ Rᴜssɪᴀ ﹙₁₅ Nᴏᴠᴇᴍʙᴇʀ ₁₈₉₅﹣₁₇ Jᴜʟʏ ₁₉₁₈﹚.

₉. Sᴀɢɪᴛᴛᴀʀɪᴜs﹕ Mᴀʀɢᴀʀᴇᴛ Tᴜᴅᴏʀ﹐ Qᴜᴇᴇɴ ᴏғ Sᴄᴏᴛʟᴀɴᴅ. ﹙₂₈ Nᴏᴠᴇᴍʙᴇʀ ₁₄₈₉﹣₁₈ Oᴄᴛᴏʙᴇʀ ₁₅₄₁﹚

₁₀. Cᴀᴘʀɪᴄᴏʀɴ:﹕ Cʜᴀʀʟᴏᴛᴛᴇ Aᴜɢᴜsᴛᴀ ᴏғ Hᴀɴɴᴏᴠᴇʀ﹐ Pʀɪɴᴄᴇss ᴏғ Wᴀʟᴇs ᴀɴᴅ ᴏғ Sᴀxᴇ﹣Cᴏʙʀᴜɢ ᴀɴᴅ Gᴏᴛʜᴀ. ﹙₇ Jᴀɴᴜᴀʀʏ ₁₇₉₆﹣₆ Nᴏᴠᴇᴍʙᴇʀ ₁₈₁₇﹚

#Margaret of Anjou#Marguerite d'Anjou#Queen Margaret#Lancastrian Queen#Henry VI#Louis IX#King Louis IX#Saint-Louis#Anerin Barnard#Cate Blanchette#Anne Neville#Maria of Aragon#Maria of Castille#Rainha Maria#Queen Maria of Portugal#Maria of Trastamara#Harthacnut#Hardicnut#Cnut III#Travis Fimmel#Elizabeth I#Elizabeth Tudor#Queen Elizabeth I#Tudor dynasty#Saoirse Ronan#Henry III#King Henry III#Plantagenet dynasty#Jon Snow#Kit Harrington

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Margaret Stewart, “Margaret of Scotland” “Dauphine of France” died in Châlons, France on 16th 1445

Not a subject I would normally post about, but I have before, she was the daughter of King James I and Lady Joan Beaufort therefor one of the Stewarts who were spread around all off Europe over the centuries.

Margaret had married Louis XI son of Charles VII and Maria d'Anjou in June 1436 in Tours Cathedral. As you would expect this marriage had more about the Auld Alliance than any love story.

Margaret sailed for France in March 1436, and she was escorted by some of the greatest Scottish nobles. She entered Poitiers, where a child dressed as an angel crowned her with a wreath of flowers. She was just a child herself, aged only 11, he husband, Louis in Tours was 13, they wed on 25 June 1436 and she became the Dauphine of France. The marriage of course was not consummated right away and she was taken into the household of the French Queen, Marie of Anjou, where she reportedly saw very little of her husband, whose aversion of her was remarked upon by contemporaries, the French knew her as Marguerite d'Écosse

She is said to have devoted much of her time to writing, and she was criticised by doctors for it, who claimed that her “poetic overwork” may have attributed to her death. Unfortunately, none of her works survive to this day. Reportedly, Louis ordered that all her papers be destroyed.

She was treated with kindness by King Charles VII and his wife, and when she died on 16 August 1445, there was a great outpouring of grief. Her two sisters, Eleanor and Joan, were on their way to France at the invitation of Marie of Anjou, but they arrived just a few days after Margaret’s death.

An unidentified Scot wrote of Margaret,

“Alas that I should have to write what I sadly relate about her death…I wrote write this saw her every day, for the space of nine years, alive and enjoying herself in the company of the King and Queen of France. But then…I saw her, within the space of eight days, first in good health and then dead and disembowelled and laid in a tomb at the corner of the high altar, in the cathedral church of Châlons.”

She is buried in Saint-Laon church in the French department of Deux-Sèvres, a canopy over her tomb is all that remains after the destruction during the French Revolution, which was similar to the events after The Scottish Reformation, which saw our country lose so much of or treasures and history. a modern floor plaque and grill have been added her coffin can be seen though the grill.

There is a lot more history to read about the marriage and her life here from the excellent Freelance History Writer

https://thefreelancehistorywriter.com/…/margaret-stewart-o…/

25 notes

·

View notes