#moritz schlick

Text

This chapter opens by comparing Bergson’s and Schlick’s biological epistemologies. Both philosophers agree with Spencer, Mach, and the Pragmatists in seeing the emergence of perception as biologically explainable by reference to practical goals. Both disagree with their evolutionist predecessors, endeavouring to set a limit to biologism, though in each case the limit is set differently. While Bergson finds a source of disinterested knowledge in intuition, Schlick sees intuition as a type of disinterested aesthetic attitude that cannot pertain to knowledge. Contrary to Bergson’s pragmatic account of scientific knowledge as a ‘system of images’, Schlick develops an account of theoretical knowledge (Wissenschaft) in which images are replaced by exact concepts. On this basis, Schlick objects against the thesis that intuition is a form of knowledge.

Might be worth tracking down sometime?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My heart ! 🤍

#tagitables#philosophy#moritz schlick#hans hahn#otto neurath#ernst mach#ludwig boltzmann#vienna circles#logical positivism#logical empiricism

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moritz Schlick – Biçim ve İçerik (2023)

On dokuzuncu yüzyılın son çeyreğine doğru özellikle bilimlerde kaydedilen düşünsel ve teknik gelişmeler evren ya da doğa hakkındaki akıl yürütmelerde büyük değişimlere neden oldu.

Moritz Schlick bizzat bu değişimlerin dönüm noktasında yaşamış bir düşünür.

Matematikçi ve fizikçi olmanın getirdiği bir zihinle güncel tasavvurları da göz önünde bulundurarak varlık ve dil hakkında yeni anlayışlar…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

On June 22, 1936, the philosopher Moritz Schlick was on his way to deliver a lecture at the University of Vienna when Johann Nelböck, a deranged former student of Schlick’s, shot him dead on the university steps. Some Austrian newspapers defended the madman, while Nelböck himself argued in court that his onetime teacher had promoted a treacherous Jewish philosophy. David Edmonds traces the rise and fall of the Vienna Circle—an influential group of brilliant thinkers led by Schlick—and of a philosophical movement that sought to do away with metaphysics and pseudoscience in a city darkened by fascism, anti-Semitism, and unreason.

The Vienna Circle’s members included Otto Neurath, Rudolf Carnap, and the eccentric logician Kurt Gödel. On its fringes were two other philosophical titans of the twentieth century, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Karl Popper. The Circle championed the philosophy of logical empiricism, which held that only two types of propositions have cognitive meaning, those that can be verified through experience and those that are analytically true. For a time, it was the most fashionable movement in philosophy. Yet by the outbreak of World War II, Schlick’s group had disbanded and almost all its members had fled. Edmonds reveals why the Austro-fascists and the Nazis saw their philosophy as such a threat.

The Murder of Professor Schlick paints an unforgettable portrait of the Vienna Circle and its members while weaving an enthralling narrative set against the backdrop of economic catastrophe and rising extremism in Hitler’s Europe.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON EMPIRICISM: THE VIENNA CIRCLE

Habitual exposure makes things invisible. Fish are unaware of the water they move through, just as we humans typically fail to notice the air around us, unless there is a breeze.

For as long as most of us have been alive, our modern culture’s methods for exploring reality have prioritized mathematical logic and empirical science as the exclusive means to uncover truths about existence. Even spiritual intuitions or faith in a received religion is almost always framed in reference (and sometimes in opposition) to the standards of science. Scientific standards are like the air around us or the water in which fish swim.

Of course, this was not always so. In European culture, it took several centuries of struggle for empirical science and mathematics to push back against received religious “wisdom” about how the universe works. Scientists were often threatened with excommunication or death for promulgating empirical findings that contradicted church teachings (see: Copernicus). Even as empirical science rose in its powers of persuasion and credibility, social fissures developed and violence ensued (see: Darwin).

The cultural shift toward science as the arbiter of truth was not a constant march but rather a fitful, sporadic, and haphazard journey. During the centuries-long transition, it was not uncommon to find people with one foot solidly in each camp. Most notable among them, perhaps, was Sir Isaac Newton himself, discoverer of the laws of gravity and codiscoverer of calculus, who nonetheless produced far more written pages on alchemy than he ever did on mathematics or science.

At some point, though, the balance of power did shift. Science gained ground throughout the nineteenth century, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Scientific successes such as germ theory and the electric light bulb were vivid and immediate indicators of its reliability. And with the collapse of the old social orders in the violent chaos and destruction of World War I, momentum picked up speed.

The war had demolished the Austro-Hungarian Empire and reordered political power throughout Europe. Medieval hierarchies (the church and the aristocracy) were giving way to capitalism, communism, socialism, and fascism. Meanwhile, modern art, music, and writing were flourishing. Eventually, a movement coalesced in Vienna, one that would ultimately solidify what was to become our modern perspective.

From his office at Berggasse, Freud paved the way for a radical new understanding of human behavior. Not far away, Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were painting, Gustav Mahler and Arnold Schoenberg were composing, and Robert Musil and Stefan Zweig were writing.

Within this emergent hotbed of cultural activity, a diverse group of idealistic thinkers came together to concretize the view that empirical science and mathematical logic, exclusively, should guide our understanding of the world. These philosophers, scientists, mathematicians, logicians, and political and social theorists would later come to be known as the Vienna Circle.

They sought to banish nonscientific insights from what they considered reasonable, modern discourse and to purge philosophy of the more fanciful speculations of prior centuries. They didn’t aspire to perform science themselves but sought to catapult philosophy into the twentieth century; with the aid of modern logic, their aim was to make philosophy as scientific as possible.

The Vienna Circle was first gathered in 1924 by the philosopher Moritz Schlick, the social reformer Otto Neurath, and the mathematician Hans Hahn. Meeting regularly on Thursday evenings in a small lecture hall at the University of Vienna, the group referred to themselves as “logical positivists” and immediately entered into a decade of heated, though largely collegial, debate. What mattered most to them was how to characterize scientific knowledge and how to understand the nature of mathematics. Their fervent mission was to prevent philosophical confusion rooted in unclear language and unverifiable claims. They wished instead to convert philosophy into something “scientific” and set mathematics on complete and consistent foundations. As a corollary to all this, they also sought to banish metaphysics from modern thought.

Metaphysics is a field of philosophical inquiry concerned with questions that cannot be answered through an examination of material existence. Any attempts to understand the nature of life after death or the existence of a soul, for instance, would be a metaphysical speculation, as would efforts to comprehend the nature of gods and goddesses, or of a singular creator God.

Until the modern era, statements about consciousness fell exclusively within the realm of metaphysics. Church doctrines derived from ancient texts or spiritual insights—the only attempts to grapple with consciousness available at the time—were all metaphysical.

To a member of the Vienna Circle struggling to push past medieval modes of thought, anything with the whiff of metaphysics was to be summarily dismissed. If something could not be ascertained by empirical science or mathematical formal logic, it was deemed worthless. Indeed, among this crowd, declaring some statement to be “metaphysics” was to suggest not merely that it was wrong but that it was devoid of any meaning or significance. When debates within the circle grew heated, a declaration of “metaphysics!” by an opposing thinker was the ultimate smackdown.

The Vienna Circle led the way for our modern culture to award science and mathematics exclusive ownership over the truth. And the many successes of empirical science—from the development of antibiotics and vaccines to the exploration of other planets—fully demonstrated the power and importance of scientific methods.

As it turned out, though, while the philosophical vision of the Vienna Circle was idealistic and well-intentioned, it was also naive and destined to fall short.

0 notes

Text

Ungváry Krisztián és a Nyelvi Fordulat

Ungváry Krisztián 2023-ban tartott egy előadás sorozatot „Egy történelem – sok magyarázat. Interpretációk a magyar történelemről” címmel. Az előadások nagyon érdekesek és tanulságosak, és ajánlom is őket, a youtube-on mindegyik megtekinthető.

Az első előadásban azonban, melynek címe : „A történész mint „bíró”. Ítéletalkotás és történeti koncepciók”, Ungváry „sajnos” a történelemtudomány filozófiai kérdéseivel foglalkozik. Azért írom, hogy „sajnos”, mert úgy gondolom az előadás eléggé kusza és nem kellőképpen átgondolt. Ungvárynak szerintem sok módszertani és elvi elképzelése helyes, de teljesen szükségtelen ehhez azokat a „filozófiai” kérdéseket előrángatni, amikről beszél. Igazából egy ponthoz szeretnék hozzászólni, mert az egyik diáján Richard Rorty neve szerepel, és mivel nekem Rorty különösen kedves, ezért megszólítva érzem magam, hogy kommentáljam az előadás ezen részét, ami nagyjából 10 perc.

Elég nehéz belekezdeni, mert ebben a 10 percbe Ungváry elég sok mindent besűrít. Kezd a „nyelvi fordulat” bemutatásával, aminek levonja szerinte legfontosabb tanulságait, majd ezt szeretné használni keretrendszerként különböző idézetek elemzésére. Az idézeteket az általa „új konzervativizmusnak” nevezett irányzat illusztrálására használja, ami szerinte egy „posztmodern” jelenség, bár nem definiálja mit érte „posztmodern” alatt illetve azt sem, hogy ez hogyan kapcsolódik a „nyelvi fordulathoz”.

Elsőként Ungváry a filozófia „nyelvi fordulatáról” beszél, és ennek hatását vázolja a történelemtudományra. A nyelvi fordulat történelemírásra gyakorolt hatásáról nekem nincsenek ismereteim, szóval elfogadom, amit Ungváry mond, bár megjegyzem, hogy ahhoz a tanulsághoz, amit levon az előadásban és példákkal illusztrál szerintem semmi szükség a filozófia nyelvi fordulatát felhozni. Ungváry azt tekinti a fő tanulságnak, hogy a nyelvhasználat befolyásolja azt, ahogyan a világról gondolunk. Az ő példái a „patkánylázadás”, a „gengszterváltás”, illetve a „módszerváltás”. Szerintem mindenféle nyelvi fordulat nélkül is érthető, hogy akik ezeket a megnevezéseket használják, milyen színben szeretnék feltüntetni ezeket az eseményeket, én itt nem látom szükségét semmilyen filozófiai hivatkozásnak. Ahhoz, hogy tudatában legyünk annak, hogy bizonyos kifejezések lekicsinylők vagy rosszindulatúak nem szükségeltetik egy „nyelvi fordulat”.

Ungváry Rorty-t a „nyelvi fordulat” bemutatásánál hozza be, bár kifejezetten Rorty-ról nem mond semmit. A dián a következő írás szerepel: „A nyelvi fordulat – Valóság és a valóság megjelenítése közti viszony (Richard Rorty 1967)”. Több szempontból kérdéses számomra miért áll ez így a dián. „A nyelvi fordulat” egy esemény a filozófiatörténetben valóban, de ezt elég nehéz lenne konkrét évhez és személyhez kötni. Az ember leginkább egy listát tudna adni, azokról a filozófusokról, akikre úgy gondolunk, mint a „nyelvi fordulat” elindítói, ezek Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, Ludwig Wittgenstein, illetve a Bécsi Kör filozófusai közül lehetne neveket mondani, mint Moritz Schlick vagy Rudolf Carnap. Rorty az „analitikus filozófiai” irányzat filozófusaként kezdte karrierjét, de semmiképp nem köthető hozzá a „nyelvi fordulat”, ő már egy következő generáció tagja. Ezek a filozófusok jóval 1967 előtt már megírták műveiket amiket a nyelvi fordulat részének tekintünk, szóval az is kérdéses miért szerepel ez az évszám a dián. Erre könnyű megtalálni a választ: Rorty-nak ekkor jelent meg a szintén „Nyelvi fordulat” címet viselő könyve, ami egy általa szerkesztett antológia, de Ungváry ezt nem magyarázza meg. A „nyelvi fordulat” kifejezés egyébként nem Rorty-tól hanem, Rorty állítása szerint, Gustav Bergmanntól származik, de talán ez részletkérdés esetünkben.

A dia további része is csalóka, ha már tisztáztuk, hogy Rorty itt csak azért került a képbe, mert ezzel a címmel jelent meg antológia kötete annak nem az volt az alcíme, hogy „Valóság és a valóság megjelenítése közti viszony”, hanem „esszék a filozófia módszertanáról”. Itt már úgy gondolom Ungváry a „nyelvi fordulatot” mint jelenséget próbálta magyarázni. Ungváry azt mondja, hogy a nyelvi fordulat fő üzenete az, hogy „A nyelv nem egy semleges közvetítő, nem egy átlátszó közeg, hanem egy homályos tükör.” illetve, hogy „A nyelv önálló szerepet tölt be a valóság értelmi feldolgozásában.”. Az első mondatot azért vicces egy dián szerepeltetni Richard Rorty nevével, mert Rorty leghíresebb könyve a „Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature” épp azt kérdőjelezi meg, hogy az emberi tudás egyfajta tükre lenne a világnak. Rorty vitatja, hogy a nyelv szerepe a világban levő dolgok, tények reprezentációja, és így a tükör nem is lehet homályos, hiszen nincs tükör. A második megállapítás szerintem helyes lenne, annyiban, hogy nyelv nélkül nem lehetne gondolkodni a világról, bár nem tudom mit jelent az, hogy ez a szerep „önálló”. Az „önállóság” többnyire azt szokta jelenteni, hogy valamitől független, de mitől? Ezt a mondatot így bevallom nem értem.

Ez a két megállapítás helyesen írja le a filozófia nyelvi fordulatának mibenlétét? Igazából nem. Ha már szóba került nézzük meg Rorty, hogyan definiálja a nyelvi fordulatot az antológiás kötethez írt bevezetőjében (ez Rorty egyik legjobb írása egyébként): „Nyelvi fordulat alatt azt a nézetet fogom érteni, hogy a filozófia problémái megoldhatóak (vagy elkerülhetőek) nyelvünk megreformálásával vagy azzal, ha többet tudunk meg az általunk jelenleg használt nyelvről.” [fordítás tőlem] A nyelvi fordulat sokkal inkább szólt arról, hogy a filozófiai problémákat megpróbálták egyfajta illegitim nyelvhasználattal magyarázni, és így megoldani, avagy felszámolni ezeket a problémákat. Erre különböző formákban születtek próbálkozások, nézzük a nyelvi fordulat egyik emblematikus filozófusát: Ludwig Wittgensteint. A korai Wittgenstein azt kutatta a „Logikai-filozófiai értekezés” című művében, hogy mik azok az állítások, amik egyáltalán értelmesen állíthatóak a világról és mi az, ami „nonszensz”. Ehhez a kulcsot a nyelv logikai szerkezetének feltárásában látta. A kései Wittgenstein pedig azt gondolta, szakítva korábbi nézeteivel, hogy a filozófia problémái csak azért állnak elő, mert bizonyos szavakat kifejezetten olyan filozófiai értelemben használunk, amely kiragadja őket a normális hétköznapi használatból. Amit Ungváry mond nem jelentéktelen, de szerintem nem írja le helyesen a filozófia nyelvi fordulatát.

Ez után Ungváry különböző idézeteket hoz, amikről azt állítja, hogy a nyelvi fordulat tanulságai segítenek elemezni. Az első egy Békés Márton idézet. Erre megint csak azt tudom mondani, hogy semmi szükség a nyelvi fordulatot felhozni. Egyfelől tisztáztuk, hogy a nyelvi fordulat lényege nem az, amit Ungváry állít, illetve, bár nyilván Békés Márton használ retorikai fogásokat mondanivalója közlésére, amit mond empirikusan igazolható vagy cáfolható mindenféle probléma nélkül. Ungváry maga is megjegyzi, hogy Békés állításával szemben az Osztrák-Magyar Monarchia ugyanolyan liberális rendszer volt, mint az antant hatalmak bármelyike.

A következő idézet szintén Békés Mártontól származik, itt Ungváry már a „posztmodernt” is behozza, ami azért furcsa, mert a posztmodern filozófiának alapvetően nincs sok köze a filozófiában jóval korábban bekövetkező nyelvi fordulathoz, de Ungváry nem jelzi a témaváltást. Illetve ezt és a következő idézeteket Vlagyimir Megyinszkijtől, illetve a Magyarságkutató Intézettől az „új konzervativizmus” példáinak tekinti, ami szerinte egy „posztmodern” jelenség.

Explicit nem magyarázza meg mi is teszi ezeket posztmoderné, de szerintem ezt viszonylag könnyű kitalálni. A posztmodern filozófusokat gyakran vádolják meg a „relativizmus” vádjával. Ezek az idézetek az igazságot relativizálják, a „nemzeti érdektől” teszik függővé. Ami érdekes itt szerintem, az az, hogy ha elfogadjuk, hogy a posztmodernnek része a relativizmus, akkor valóban ebből a szempontból posztmodernnek lehet nevezni az „új konzervativizmust”, hiszen ezek szerint minden nemzet eldöntheti, mit tekint igaznak, és erről nincs értelme vitatkozni más nemzetekhez tartozó emberekkel. Ami viszont szembe megy a posztmodernizmussal az az, hogy a posztmodern filozófusok bizalmatlanok a „meta-narratívákkal” szemben. A meta-narratívák olyan történetek, amelyek a világtörténelem alakulásáról egy átfogó magyarázatot kívánnak adni. Ilyen például az, amikor a marxisták az „osztályharc” fogalmával próbálják megmagyarázni a történelem alakulását. A Megyinszkij idézet kifejezetten erre szólítja fel a történészt, hogy a feladat egy olyan meta-narratíva létrehozása, ami a "nemzet" érdekeit szolgálja. Ha tényleg elfogadjuk, hogy léteik ez az irányzat, amit Ungváry „új konzervativizmusnak” nevez, akkor ez ezek szerint a legrosszabbat vette át mind a modernizmusból (meta-narratíva), mind a posztmodernizmusból (relativizmus). Ezt a helyzetet nem a nyelvi fordulat fogja nekünk megvilágítani, sokkal inkább érdemes az irodalomhoz fordulni, ugyanis ezt a fajta agyrémet csak egy olyan ember lenne képes művelni, aki mestere annak, amit Orwell az 1984 című regényében „Duplagondolnak” hív: „Megfontolt hazugságokat mondani s közben őszintén hinni bennük, elfelejteni bármilyen tényt, ha időszerűtlenné vált, s aztán, ha ismét szükség van rá, előkotorni a feledésből”. Ungváry Krisztiánnak teljesen igaza van abban, hogy ezek az idézetek problémásak és károsak, de szerintem "túlintellektualizáljuk" a problémát, ha azt gondoljuk, hogy egy nyelvi fordulatra van ahhoz szükségünk, hogy ezt belássuk.

0 notes

Text

AI approaches the wisdom of Moritz Schlick

Moritz Schlick (1882-1936) from Berlin, Germany, held the Chair of Naturphilosophie at the University of Vienna and was the founding father of Logical Positivism and the Vienna Circle. He was murdered by one of his students. Every science presupposes a principle of causality for every observable thing in its field.

Moritz Schlick 1882-1936) was the father of Logical Positivism and the Vienna…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Epistemologia

Episteme: ciencia

Logia: Tratado

“Tratado sobre la ciencia”

Platon: Obra La republica

DOXA VS EPISTEME

Opinion ciencia

Subjetivo objetivo

Sin fundamento fundamentado

FUNCIONES DE LA CIENCIA

Describe: Dar la caracterización d ellos objetos observados.

EXPLICA: Justifica con conocimiento de causa (CAUSA-EFECTO)

Predice: adelanto de juicio con lo observado

Aplica: uso del conocimiento

CARACTERISTICAS:

Sistematico: es organizado en conjuntos de argumentos

Metodico: pasos a seguir para obtener el conocimiento

Selectivo: investiga una parcela de la realidad.

Falible: se perfecciona con el tiempo.

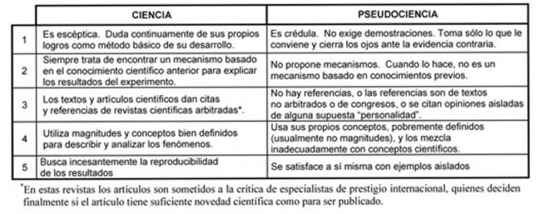

PRINICIPOS DE DEMARCACION.

Son lso criterios que permiten el carácter o estatus científico de un taeoria, es decir, distinguir una ciencia empírica de un sistema metafisico. Los criterios mas usados son: El prinicio de verificalidad (rudilf Carnap) y el principio de falsabilidad (Karl Popper).

TEORIAS EPISTEMOLOGICAS:

*Neo-positivismo:

Circulo de Viena

Influencia de comte y Wittgenstein

Propone un análisis riguroso de lenguaje

Modelo: CC.NN.

Ciencia: Método inductivo

Criterio de demarcación, verificación

Rechaza la metafísica.

Representantes: Moritz schlick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto neurah, Alfred Ayer, otros

*Racionalismo critico

Karl Popper

Rechaza el principio de verificación

Critica el método inductivo

Ciencia: propone el método

Hipotetico-deductivo

Criterio de demarcación:falsacionismo.

*Relativismo epistemologico:

Representante; Thomas Kuhn. Obra: La estructura de las revoluciones científicas.

Fases:

Fase: pre. Científica: recolectan observaciones un plan definido

Fase: ciencia normal: teoría científica que prevalece.

Fase: ciencia revolucionaria: Nivel intolerable de anomalías. El paradigma vigente entra en crisis y compite con otras nuevas teorías. (Asimilacion del nuevo paradigma).

*Anarquismo epistemologico

Fue propuesta por PAUL FEYERABEND. Afirma que la ciencia avanza al no sujetarlas a normas metodológicas establecidas o convencionales. L a única regla para la investigación científica debe ser: “Se permite todo, o el todo vale.”

Se debe restringir el método científico.

*Epistemologia de Mario Bunge

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bergsonism and the History of Analytic Philosophy

Bergsonism and the History of Analytic Philosophy

Bergsonism and the History of Analytic Philosophy Andreas Vrahimis

During the first quarter of the twentieth century, the French philosopher Henri Bergson became an international celebrity, profoundly influencing contemporary intellectual and artistic currents. While Bergsonism was fashionable, L. Susan Stebbing, Bertrand Russell, Moritz Schlick, and Rudolf Carnap launched different critical…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Verificationist Man

#Philosophy#Existential Comics#philosophy of science#epistemology#Circle of Vienna#Rudolf Carnap#Gottfried Leibniz#immanuel kant#Alfred North Whitehead#Moritz Schlick#verificationism#verificationist man

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Moritz Schlick, General Theory of Knowledge, Translated by Albert E. Blumberg, «Library of Exact Philosophy», Springer, Wien, 1974

#graphic design#philosophy#philosophy of science#epistemology#book#cover#book cover#moritz schlick#albert e. blumberg#library of exact philosophy#1970s

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Risto Hilpinen, Hintikka on Epistemic Logic and Epistemology

(I don't care for vocabulary like "representations" and especially "object files" tbh but found this interesting nonetheless)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wittgenstein with Moritz Schlick and the Vienna Circle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Moritz Schlick – Felsefenin Doğası (2023)

Felsefe nedir?

Felsefenin bilimden farkı nedir?

Felsefenin konusu ‘cevaplanamaz sorular’ mıdır?

Bir felsefe sorusunu diğer sorulardan ayırt eden nedir?

Hayatın bir anlamı var mı?

Kısacası ‘felsefi düşünme’ nasıl gerçekleşir?

Analitik felsefenin ve Viyana Çevresinin kurucu düşünürlerinden olan Moritz Schlick’in bu kitabı, felsefenin mahiyetine ilişkin net bir bakış sunuyor.

Geleneksel felsefe ile…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

There is no distinct 'philosophical knowledge' over and above the analytic knowledge provided by the formal disciplines of logic and mathematics and the empirical knowledge provided by the sciences. Philosophy is the activity by means of which the meaning of statements is clarified and defined.

Moritz Schlick, Erkenntnis, vol 3

#philosophy#quotes#Moritz Schlick#Erkenntnis#logic#mathematics#empiricism#knowledge#science#understanding

299 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Philosophy elucidates propositions, science verifies them. In the latter we are concerned with the truth of statements, but in the former with what they actually mean.

Moritz Schlick, General Theory of Knowledge

#moritz schlick#general theory of knowledge#quote#quotation#quotes#quoteoftheday#lit#literature#philosophy#knowledge#science#truth

29 notes

·

View notes