#my current one cost about $400 a handful of years ago; maybe 2017

Text

My computer might be fucked. Entirely.

Awesome.

#god. damn it.#I had two days of BLISS and opportunity#and now#this.#I work off of my computer and write off of it#it it genuinely also one of the only things that keeps me sane#my current one cost about $400 a handful of years ago; maybe 2017#I’m so pissed and sad#now I might have to choose between my wheelchair and a new computer#because this one keeps breaking down at random#it won’t copy-paste things#my screen keeps glitching at random#it keeps going black at random intervals#I just#I don’t know#I want ONE DAY where I’m not constantly stressed out of my fucking mind#and ONE DAY where I don’t want to break everything because I’m so stressed about money#spotty speaks#awesome. AWESOME.#vent post

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Livia Gershon | Longreads | November 2019 | 7 minutes (1,863 words)

My family’s natural gas-fired furnace is 23 years old. That’s aged; the average lifespan of a system like ours is 15 to 20 years. I live in New Hampshire, which gets awfully cold in the winter and, every October, I wonder whether we’ll make it to March. If the furnace fails this year and we replace it with another one like it, we’re committing to burning fossil fuels until about 2042. If my household switches to electricity, which is better for the environment than what we’ve got, our gas bills will nearly double, to around $2,800 every year. Recently, I called Bill Wenzel, who owns a geothermal heating business the next town over from me.

A geothermal heat pump is like a refrigerator in reverse. A hole is drilled deep into the ground, where the temperature remains steady at 55-ish degrees, then the system warms up the air some more and pumps it through the house. Wenzel told me that one of his systems would probably cut my heating bill in half. It would also provide essentially free air-conditioning, since it can circulate 55-degree air in the summer, too. The trouble is that, including the cost of drilling a bore hole, installing a geothermal system would run $30,000, compared with something like $4,000 to just throw in new gas furnace.

New Hampshire does not encourage geothermal heating with climate-conscious tax breaks or environmental subsidies. There is a federal renewable energy tax credit that would reduce the cost to me by 30 percent, but it’s slated to phase out over the next several years unless Congress takes action. Wenzel said that he does most of his business over the border in Massachusetts, where a hodgepodge of state incentives, combined with the federal credit, cut the price in half and provide no-interest financing. “New Hampshire stinks,” he told me. “That’s why I’m selling a lot in Massachusetts.”

When we think about the climate crisis, we tend to think on two levels: a global one, where the players are nations and international bodies, and an individual one, where we’re asked to make personal changes that, in theory, add up to collective transformation. But in the United States, we know that the federal government is a disaster, and it’s hard not to feel like making an individual choice is more about relieving guilt than it is about real change. If I squint, I could almost make the math work on a geothermal system by moving to another state—here in New Hampshire, not so much. And even if my family wanted to suck it up and spend thousands of dollars on green heating, we’d know, deep down, that it wouldn’t make the slightest difference to polar bears or climate refugees. Wenzel told me that a lot of people make the same calculation.

Still, from the case of my home-heating system, it quickly became clear: at the moment, the most significant place for climate action in this country is at the state level. Lately, states have been passing a wave of ambitious climate legislation, not just in Massachusetts, but also, this year alone, in Colorado, Maine, Washington, New Jersey, and New Mexico. Groups like the Sierra Club; the Union of Concerned Scientists; and 350.org, an international climate action nonprofit, have supported those laws. “As soon as Trump was elected to office, it was really clear that attention needed to shift to the states,” Emily Southard, US Fossil Free Campaign manager at 350.org, told me. Local organizations with connections in state houses have pushed their governments to address the climate crisis; some of the same has happened in cities, too. “Your traditional green groups that might do more insider lobbying have moved with frontline groups that are seeing the first-hand impacts, whether it be polluted air or water from the fossil fuel industry,” Southard went on. “They can speak to different elected officials in different ways, and can hold their feet to the fire.”

***

The best recent example of state-level progress is the passage of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), signed into law by Andrew Cuomo, New York’s governor, in July. Southard told me that it contains the strongest emission standards in the country. The force behind the CLCPA was NY Renews—a coalition of more than 180 environmental, social justice, faith, and labor organizations—that demanded not just an end to the burning of fossil fuels but also a sincere investment in green infrastructure. Of particular focus, they argued, had to be poor areas and communities of color, where environmental problems tend to hit the hardest. An estimate by the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst predicts that a plan on the scale of the CLCPA can create more than 160,000 steady jobs in renewable energy and energy efficiency; in New York, at least 35 percent of investments in housing and public transit will go to low-income or otherwise “disadvantaged” communities.

As soon as Trump was elected to office, it was really clear that attention needed to shift to the states.

How will the CLCPA affect life in the state of New York? “You would expect to see a ton of additional public transportation—bus lines, maybe light rail—so that you and your family would not need to rely as much on your vehicle,” Arielle Swernoff, of NY Renews, told me. “In terms of the health of your community, you’d be looking at better air quality. Rates of asthma would go down. In terms of jobs and industry, solar and wind and renewable jobs tend to be much more stable than fossil fuel jobs; maybe your neighbors would be working in renewable energy.”

Swernoff said that the vision for the CLCPA was based on that of PUSH Buffalo, a founding member of NY Renews. PUSH—which stands for “People United for Sustainable Housing”—lobbied the State House for the legislation’s passage; many of those involved had already been doing work that the new law will expand, such as installing renewable power systems and weatherizing homes. Rahwa Ghirmatzion, PUSH Buffalo’s executive director, told me that when the group formed, 14 years ago, it didn’t have a focus on climate; the initiative grew out of a 400-person community meeting. “Most worked in service-industry, minimum-wage jobs,” Ghirmatzion recalled. They talked about how winter wind leaked into their apartments and how, during the cold months, they sometimes paid more for their utilities than their mortgages. Yet there were plenty of skilled construction workers, handymen, and plumbers in the community, plus empty houses and vacant lots.

In the years that followed, PUSH Buffalo used tactics like civil disobedience to force the local fuel monopoly to fund weatherization. With additional money from the 2009 federal stimulus and a 2012 New York State law that it also lobbied to pass, the group renovated more homes with the best available solar power and geothermal systems. PUSH opened a “hiring hall” for green-construction workers and started training Buffalo residents returning from prison and young people not on a college track. They’re now planning a 50-unit project with a zero-carbon footprint that includes supportive housing for people with substance-use disorders and mental illness. “We thread workforce through every single component,” Ghirmatzion said.

Organizers such as these draw connections between local needs and the global climate crisis; they’re effective lobbyists for state regulation because they’re looking out for their livelihood. The steps can be incremental, to be sure; Swernoff said that NY Renews will have to keep fighting for real progress. Currently on the agenda: getting the state to pay for its energy transition by setting a penalty for polluting industries and influencing appointments to the Climate Action Council, the body charged with implementing the CLCPA. Some member organizations are also fighting a fossil fuel pipeline. Overall, though, she has a sense of hope. “It’s really easy to just get discouraged by the lack of action at the federal level, and I feel and understand that, but I think it’s really critical that states are taking these steps,” Swernoff said. “The work that we’ve done, and that other states have done, figuring out policies, figuring out how this works, are also impactful.”

***

Setting a goal doesn’t guarantee reaching it. In California, a national leader in climate legislation, implementation has been a serious challenge. From 2016 to 2017, for instance, the state reduced carbon emissions by just 1.15 percent and, according to Next 10, a nonprofit that monitors California’s climate efforts, if that pace continues, the state won’t reach its 2030 goal until 2061. James Sweeney, a professor of management science and engineering at Stanford University, told me that California has made strong progress when it comes to generating electricity from renewable sources, but that conventional vehicles and agricultural emissions remain a problem. “The bottom line is that California set very ambitious goals, but then you measure the actual progress toward those goals, the progress is not as dramatic as the goals set,” he said.

Everything we do determines just how bad the problem becomes.

The key to meaningful change, Southard told me, is grassroots engagement. Almost every state battle on environmental legislation has come down to the work of people who have felt the stakes of the climate crisis—those who lost their homes in New York during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, or in California during the devastating recent fires. Southard, who is based in Denver, told me that much of the attention in her state is on fracking; climate activists have formed alliances with other local interest groups for whom the environmental consequences are personal. “Here in Colorado there’s been a real coming together of those diverse constituencies,” she said, “to make sure any climate legislation isn’t just about a renewable energy standard—where it might mean that we’re putting a lot of solar on rooftops but we’re not closing down a coal-fired plant in a people-of-color community.”

In New Hampshire, for the past two years, Chris Sununu, my state’s governor, has vetoed bills that would have helped develop a more robust renewable energy industry. But the climate movement is growing here, too. In September, in the state’s biggest environmental protest since the seventies, a group of 67 activists got themselves arrested while demanding the shutdown of one of the last coal-fired power plants in New England. Sununu, a Republican, remains resistant to climate action, yet it’s not hard to imagine that, as in other states, the environmental movement would expand and join forces with other grassroots forces to craft a comprehensive plan he can’t ignore. Maybe my aged furnace will even hold out long enough that, by the time it dies, a geothermal system installed by well-paid local workers will be a viable option.

When contemplating the climate crisis, it’s easy to get stuck; even the best signs of progress we’ve got might not be enough. But everything we do determines just how bad the problem becomes; Southard said that state and local action can provide a template for federal laws—so far in the 2020 campaigns, there’s been lots of talk about ambitious plans to help the U.S. reduce its monstrous carbon footprint—and they also matter on their own. As she told me, “Every time a municipality or a state is passing climate action, then it’s knitting together this massive framework which we need to truly address the climate crisis.”

***

Livia Gershon is a freelance journalist based in New Hampshire. She has written for the Guardian, the Boston Globe, HuffPost, Aeon and other places.

Editor: Betsy Morais

Fact-checker: Samantha Schuyler

0 notes

Text

Oculus Quest - Room-Scale VR For Schools - A Full Review

Since the original Oculus Rift was launched several years ago, I was converted to the use of VR. There was so much potential out there for VR for the forward thinking technology departments to drop into. As I learned more about the modification (or home brew) scene in VR I was hooked on the Oculus Rift Developer kit - even when there was only 4 degrees of movement and the tethering of the HDMI cables meant you were attached to a laptop or desktop and usually seated because there wasn’t and Z axis tracking.

Then came the addition of things like VorpX. This allowed you to take a first person type environment and then transpose it into a VR game. Driving, roaming, exploring and being part of a game became a truly immersive experience. I loved it - even on the mediocre screen back then.

Then came all sorts of varieties and news in the tech media of what was technically possible - Leap Motion was one of the main ideas of this time - the mapping of hands and limbs within VR. There was a very positive outlook for VR back then. Then came the HTC Vive. Wow. A standing, ‘outside-in’ trackable environment that ran on a beefed up PC hardware pushing the realms of a not-too-distant future of VR for the masses. Along with this came the Leap Motion clip-on module, the additional ‘pucks’ for tracking and backpack PCs for untethered outside in tracking.

A little back story: the phrase ‘VR for the masses’ has been around since the mid-nineties when I remember seeing an advert for Sega and Nintendo VR. The snag is that VR has been around a while and the mantle for which VR type, style and format is best. The real bone of contention is, if it’s for the masses, then it really needs to be pared down because not everyone has a PC with a (now aging) GTX 1080 to provide room-scale grunt for their VR realms and the floor space to create the ‘Guardian’ that is required for room-scale VR.

The pared down version comes at a cost to the user, I feel. Namely the appliance-like nature of the device so that the mass-produced all-in-one case can provide a three-click platform: turn on, choose game, hit go. The appliance also pares down what the ‘user’ should be able to do. I find that this channels the user into what the appliance’s designers want you to use and how you should use it. Think of it like an IKEA type VR. You shop at IKEA and all you can do is trundle through the alleyways following the arrows pointing you to checkout and exiting with items you never came in for. The format and style of current titles is also of a low poly nature, that to be frank, surely cannot keep going where every title has the same blocky nature.

That is where I feel we are at with the Oculus Quest. This takes the room-scale usership to a simplified level - albeit a well crafted one. Unlike the IKEA analogy, the Quest is very well built, offers a robust material set and has very ergonomic controllers that offer a some hand tracking that seems (at the moment at least) to halt at finger pointing to turn switches on and off in-game. Here the Quest’s controllers are AA style removable batteries. Knowing how fast the Vive’s paddles are depleted I think you’ll be looking for something like Sony Eneloops to get all-day longevity out of these. The same goes for making a hack for the headset’s USB-C battery bank connection as I had gone through half the battery in about an hour of intermittent use. In school though, I think most tech departments are looking for internal rechargeable batteries where a power bank can be USB connected and recharged.

The well-built nature of the headset means that the phone-like innards (Qualcomm 835 (3years old equivalent to a Samsung Galaxy 8), Adreno 540 GPU and 4Gb RAM run the device pretty well. The heavy coating of the Quest, combined with the screen means this thing is pretty heavy on the face after about an hour. Other people have said they get tiredness around two hours however I have a gigantic Roman nose that felt like it was supporting the entire thing after a while.

When you put the headset on, I like the way it recognises the headset is on your head and uses similar sensors to that of the eye-piece of a digital camera to turn the LCD off and turn on the viewfinder. This presents you with a lovely screen and decent adjustable lenses to view content. The controllers are simple to find (they light up on screen when the headset is on which is a nice touch) and the pass-through camera lenses on the front of the device also highlight the controllers which is similar to the more high-end Vive where searching for the controllers/ searching the room is needed.

The interface is simple and has a store that seems to be filled with large number of apps and games (50at present). Now, I was expecting a lot more from this section for both apps and games. I was kind of expecting something similar to the Oculus, Vive and Steam stores. Lots of people have said that this has plenty of games starting with 50 for this specific Quest store. This is where people get a bit miffed in terms of ‘content’. If you are a Steam user then you know that there may be 5,000 games and apps in the store, yet there will only be around 10% of those games that have good reviews or good enough for you to start there. Then there will be only about 30% of these top rated games that are to your taste and of those about 10% are affordable. I think you get what I mean here, there are only about 5 of those games that I would like to play yet this is not what I’m after in this instance. What I'm after is creative or story telling experiences that wow the user...

You see, the apps needed in a school are creative, world—builder type apps that put the controllers front and center and the device set to its limits. I want it to allow me and my students to create and build something then export it somewhere to be used elsewhere, say, in TinkerCAD and 3D print it. There is only Tilt Brush by Google that I can see in the Oculus store and this was $30 (around 1000thb here in Thailand -that's way too much). TiltBrush on Steam for the full version on the Vive is much cheaper. Also, I say ‘full’ because there is no way that this phone could cope with building the scale of the models you will end up creating and exporting from a whole class - especially if you are making a walkthrough gallery of models.

The next part is looking for experiences for my students because the creative angle is blocked within a single mainstream application. I looked for video and 360 degree environments either from YouTubeVR or from sites that offer the experience from the site itself. In this regard, I tried out FirefoxVR - this has potential however as of yet there’s not much difference to a phone VR experience. What I wanted in this realm were the types of environments such as Allumette that guide you in room-scale via sound or trinkets and want to immerse you within the story itself. No such luck. Maybe there’ll be some ported over.

I also searched for apps similar to Google Expeditions, Google Stories and places to build or explore such as Museums. Sadly there isn’t really anything that stood out as something I would use a Quest for in my classroom other than what I have used previously with Android phones and Google Cardboard (or Cardboard-like headsets). These offer the same experiences as on the Quest for students that teachers always ask for, and, more importantly class teachers need to be able to search for content to splice into class projects. Having Android phones as your class set of VR devices also allow you to log into a single Admin user on the Play store and wirelessly push out the apps to each of the phones.

The other snag I felt that limited the use in the primary classroom especially is, should you work in a large school such as mine (8 form entry and a total of 2600 students from 3-18), having just one Quest in class, where usually two lessons of specialist provision or eight classes are running simultaneously, how can you reasonably use something like Tilt Brush, Blocks or should it ever arrive: Co Spaces, and include all children. In my school I only see the children in the 16 Junior classes once a fortnight for an hour at a time. It would require 8 devices per class set minimum with a teacher’s unit to get close to coverage.

The next item to think about here is the overall cost of a class set of Quests versus a class set of Android phone based class sets. Even if it was a set of 6 Quests, these 6 a need an additional phone for ownership for each seat in the app store (or users in the Oculus store per app per device) after the initial $500(+pp +duties) each. (The ones we have are 128Gb models the 64Gb models are $400 each) - that makes a class set cost of a minimum USD$3000 (for the models we have) before shipping and import duties.

Compare this to my previous set up of:

13 Xiao Mi Red Note 6’s with jelly-like cases =13 x S$230 (2017 models) = S$2990

2019 Mi RedNote 7 (3Gb, Qualcomm 632, 6” , 4000mah, ) similar pricing here

14 iamcardboard headsets (spare included): 14 x S$ 322 + S$50 shipping

6 Anker 10000MiA battery packs = 5 x S$55 = S$330

14 Sennheiser HD202 headphones (spare set) 14 x S$54.99 = S$769

Grand total for 1:2 class set of VR headsets: S$4488 = USD $3243.48

We can easily skin this total down by not purchasing battery packs or the Sennheiser and only buying Apple style earbuds ( I prefer these hard shell earphones for their durability). Cheap copies are available on the likes of TaoBao, Ali express or Lazada for a lot less. However, for this comparison, I’m going with the Oppo/ Huawei standard 3.5mm type that come in at S$19.

13 Xiao Mi Red Note 6’s with jelly-like cases =13 x S$230 (2017 models) = S$2990

2019 Mi RedNote 7 (3Gb, Qualcomm 632, 6” , 4000mah, ) similar pricing here

14 iamcardboard headsets (spare included): 14 x S$ 322 + S$50 shipping

14 Oppo/ Huawei earbud type earphones: S$19 x S$266

Grand total for 1:2 class set of VR headsets: S$3628 = USD $2619.42

With import duties and shipping, the Quest set works out roughly the same for a 1:2 class set (our classes are capped at 24 children ) of devices that, in my experience are simple to manage and above all else, provide a bookable resource of mobile devices that are not locked down in the same way as the Oculus Quest and provide all the functionality of a phone: video, stills, editing, QR and other apps too. The locked-down nature of the Quest where there needs to be another phone attached with a person’s Oculus account to release the developer mode really is a bind that you don’t really experience on Android devices, nor do you want to experience this as a class teacher with your students. Unless, of course, you have a teacher cohort at your school that frequently flash custom Android ROMs on their devices. However, I doubt this very much.

The thing I’m going to lead onto here is that the need for another phone’s Oculus app to pair the device for the Quest to enter Developer mode really is a step too far by comparison to a standard mobile phone for general class use. This enhanced mode allows you to you sideload apps from your Windows computer which, as a stand alone R&D device is perfect. The real stickler here is twofold and this is part and parcel of it being a great R&D device for honing staff member’s understanding of what technology is just around the corner. What I’ve learned from this type of R&D is that when single units like this are dropped into classrooms they spark so many ideas and lead-in for new wild projects or add-ons for already outstanding projects. What they don’t do is shape the current use and ready-planned resources within a school, the working, easy-to-use devices do this. The Quest is a fabulous device for future planning and aligning budget cycles especially if you run a 10% R&D already or are about to.

The two fold nature of this device is that, yes, you can mirror your computer with Riftcat and run Steam VR from here. However, I found it sketchy at best and, in school environment this has a ‘faff-to-success’ ratio of about 2:10 which, is how I found the HTC Vive originally but the ideation that came from that HTC and all the teachers who used it was astounding. The other issue, and this is a big one in terms of school use, is the tethering of the Quest to another mobile phone with the app on it. This makes it instantly a 1:1 device or in an environment such as a school is a put on/ pull off situation where there is limited time to actually make anything, say an .OBJ, for something such as Co-spaces a very tricky thing to achieve with a large proportion of kids younger than 13 or 14. Time constraints and, subsequently the exclusive nature of the device is difficult to bring into a specialist lesson. An all day round-robin cycle of activities that had this as a 20 minute building set would also hone the ideas for what we can do with the class set of Android phones for VR. The bigger social issue with this is that a single VR device, while that one kid is using it everyone is looking at that one kid wondering what the hell they are seeing. It is possible to cast the screen to another computer however, again I found the picture quality contained a lot of artefacts that may have just been the setup of our school network. This was certainly the case for streaming Steam content and to remote desktop. The ‘faff’ scale was hockey stick shaped with this endeavour.

Back to the tethering. This is mandatory for developer mode (why this isn’t a toggle on the device to begin with I don’t know as it’s an eight tap sequence in Android settings) which in turn is needed for the creation of the business account at Oculus.com. Once this is done, you can install the ADB drivers, Powershell script and then you can add other free VR apps from the Sideloader platform. As a serial tinkerer, this had me very much tempted into the ‘what if...? idea stream in my mind’. I was thinking along the lines of ‘what if we can build something and export it. Can we make a simple video compilation or edit game streaming as stories” for example. As it turns out, not really, maybe we will have this soon. Remember, the original Rift was like this and the Quest is a similar informant.

Now then, the Sideloader games and apps... as with any communities such as this, you need to be sympathetic to the wants and desires of devs and tinkerers, and the unstoppable desire for nostalgia. I’m talking really about the porting of games such as Quake into a VR headset such as the Quest. Sadly these don’t really work, but the desire is there to produce these kinds of channels for once champions of the gaming world. In fact, I’m still searching for a port of a game where the parabolic head movement combined a similarly moving horizon doesn’t induce instant nausea. On the other hand, these kinds of apps and games are for niche elements of school life and are a far cry from being useful for the layman - such as the painting polygon app in Sideloader. It’s an early start, yet these are not built school use in mind.

The final note here is to do with the trajectory of VR for schools versus the path VR is taking. The types of kits and the resources that are available for schools is fantastic. Something so simple as the Tuscan villa or Google Earth VR is an exceptional example of how children can be inspired to write or experience a scene that inspires other aspects of our curricula. Google Earth VR has a real Gulliver’s Travels feel about it. The snag is, harking back to the phrase ‘VR for the masses’ earlier, means that the likes of Facebook need to earn back their investment and to gain a profit by securing users to a platform. And to do this, they need to make the devices locked down and appliance-like. The games need need to be just that, games where eyeballs are on the screen as much as possible and to serialise these mini franchises. Google Earth et al is not going to do that job. Ever.

In essence, schools need to think and research very carefully how they are going to incorporate these types of devices into classes, to include as many children as possible because the learning experiences to be had from VR, as much as I’ve experienced with my classes, provide a primary source knowledge base for nearly all students, that has an outstanding knock-on effect, especially in areas such as creative writing and as I mentioned above, ideation.

0 notes

Text

I just sold my 2017 Z06 at bottom dollar and couldn't be happier (GM Sucks) via /r/cars

I just sold my 2017 Z06 at bottom dollar and couldn't be happier (GM Sucks)

As the title says, two weeks ago I sold my 2017 Z06 at bottom dollar and am glad to have that POS out of my life.

For some context, I’ve always been a car fanatic. I’ve been “car poor” my entire adult life. I’m currently 34. I got my first C5 Corvette at 16. Since then, I’ve owned a total of 5 Corvettes. Most of the time I owned two, one to beat on and one to keep clean. In November, 2016 I bought a brand new base 3-pedal 2017 C7 Z06 for just over $72k (sticker was $81k). At the time, I already owned two C5s (one stock C5 Coupe and one modded/widebody C5Z). I daily drove the C7Z and took it on several exotic car rallies and road trips. Since I could barely afford the car and never thought I'd buy a brand new car, I figured I'd drive it as much as possible. I managed to put well over 1000 hours and over 38k miles on the car in two and a half years. The first year was great. The second year and a half wasn’t.

First issue I encountered was the overheating issue. I had the car go into limp mode on the street on three separate occasions. I didn’t waste my time trying to track it, because it was pointless. Suddenly ending up with a 325hp drop in power on the track is a terrifying prospect. I should note that I did have some track time in a C7Z at the Ron Fellows Corvette Driving School at Spring Mountain Motorsport Ranch. They deny it, but it’s clear that the short track sessions are due to the overheating issues. There were two separate occasions where I was with a group and had a racetrack rented out and I didn’t drive the car on the track, and instead chose to ride passenger in friends cars, while my "race car" sat in the paddocks next to the track. There are multiple class action lawsuits against GM for this well known issue. GM even publicly acknowledged this issue and said that it was addressed in the ’17+ models. It wasn’t.

The next issue I encountered was the defective wheels. Based on what I've read online, the C7Zs have wide, 20”x12” rear wheels. They are made in Mexico and cast, not forged. They crack on the inside lip of the wheel, without impact. My first wheel cracked at exactly 16k miles, 7 days after mounting and balancing new tires. I was returning from Miami, heading towards DC when I started losing air in South Carolina. I had to stop in North Carolina to get it repaired. I thought it was a nail, but was informed that it was a cracked wheel. Since there were no signs of impact, the dealership replaced the wheel under warranty and I was on my way in about two hours. Later at 32k miles, 10 days after mounting and balancing new tires, I was losing pressure in the same (replaced) wheel. Again it was cracked with no evidence of impact. The dealership denied replacing the wheel under warranty. GM’s customer service was useless. They said that the dealership tech stated that it was “driver error.” I asked what evidence they had and they said that “it appears the car was driven very fast”, likely due to the rally graphics I had on the car. My response was “no shit it’s been driven fast, it’s a fucking Z06!”. After 3 weeks of going back and forth, I gave up and I bought a new wheel, tire, and TPMS sensor. The fact that I had to replace a 3 week old, $450 tire, since it was compromised from being driven on flat multiple times is what upset me more than the actual wheel. I'll also note that at 38k, the car was still on its original alignment and drove straight as an arrow, which also helps demonstrate that I never hit a pothole or did anything that should crack a wheel. There’s also a class action lawsuit against GM for this as well.

At 32k miles, I was also informed that I had a leaking shock. The C7Z has magnetic shocks that retail for over $700 each. Luckily the dealership replaced it under warranty, but it still took them several weeks to get the parts and make an appointment. When I brought the car in for its next service at 38k miles, I was informed that the other 3 shocks were leaking. I brought it in to a different dealership (since I was salty about how the previouse dealership handled the wheel issue) to see if they’d do a good faith repair, since shocks should last around 80k+ miles and the fact that all 4 were blown shows they’re defective. More importantly, they likely failed during the warranty period. Also, the fact that they didn’t all break at one time shows that there was no single driving event that destroyed them. The dealership calls me back and says that they’ll replace them (over $3k parts & labor), but I’d have to pay a $500 deductible. I said go for it. When they called me back 3 days later, I thought they were going to tell me that the car was done. Nope. They said that they made a mistake and it would be $1,100 dollars. This doesn’t help me since I found the shocks online for $400/each and can replace them in my driveway in an hour. Again, GM customer service was useless. I haven't read about any class action lawsuits about the shocks, but I suspect it's because most C7Z owners don't daily drive their cars in winter climates.

Then, there’s tires. The car had a total of 3 sets of Michel Pilot Sports and one set of the sport cups. Additionally, I needed to replace two tires due to nail punctures and one due to the wheel issue above. Now, don’t get me wrong, the Michelin Pilot Sports are the best tires I’ve ever used, and are worth the cost. It just sucks spending ~$10/day on tires. The Pilot Sports last me around 12k miles per set, mainly due to the aggressive alignment of the car, relatively low treadwear rating, and shallow tread depth. The Sport Cups typically last ~7k miles. They lasted me ~5k miles. I managed to go through a set in two weeks when I drove from DC->Toronto->Miami->DC. Again, this is just me whining, not complaining, since we all know the sacrifices involved with high performance tires. It’s just still kinda crazy to have spent almost $10k in tires in two years.

After the frustration with my second cracked wheel, I started shopping for other cars. I found a 970RWHP Twin Turbo C5 that captured my interest in NJ, so I stopped by Carmax to get an offer before checking out the TTC5, so I’d know what to expect as a bottom dollar trade-in. They quoted me $48k, deducting points for a cracked windshield (my fault), high mileage for the model year, and sports car season was ending (it was late November). I decided to hang on to the car until spring, since selling a sports car in winter is cumbersome.

After learning about the shocks, it was clear that I needed to exorcise this demon ASAP. I figured that I could clean the shocks and reasonably expect to get ~$47k from Carmax, since the mileage was slightly higher, but sports car season was in full bloom. I told the dealership to give me an offer and save me a trip to Carmax. If they offered me $45k, I would’ve accepted. They called me back a few hours later and said that they wouldn’t even give me an offer and I should bring the car to Carmax. They said that in addition to the defective struts and cracked windshield, they inspected the car and it’s showing signs of excessive clutch wear. That’s right, the dealership didn’t want to make an offer on my two year old, dealer maintained (w/ full service records), flagship model, even at bottom dollar.

For the record, I’ve been shifting my own gears since I first rode a dirtbike when I was 10 years old. My 2nd C5 had 126k miles on the original clutch when it was rear ended and totalled. I had an E39 with 197k on the original clutch. For fun, I drove my second C5 for a few months without using the clutch, except to start, and only would lightly grind maybe once or twice per week (out of thousands of shifts, including downshifting to first as I approached stops). My first C5 had a SPEC stage III+ racing clutch and lightened flywheel. My point is that I’m about as gentle on clutches as they come. I remembered when I first got the car that I was amazed that somehow GM could make a clutch that handles 650lb of torque and is VERY easy to drive and streetable. Actually, between the large amounts of torque, the easy clutch, and automatic rev matching, a C7Z is probably one of the easiest cars 3-pedal cars to drive. To me, it seems that GM didn’t actually make a clutch that handles 650lbs of torque.

So, I picked up the car from the dealership at 3pm. I called a buddy who has a collector car dealership and told him that I plan to drop that car off at Carmax the next day and should get around $47k. I told him that he could buy it off of me, as-is for $46k, which is $5k cheaper than any used 3-pedal C7Z listed, which would save me the trouble of going to Carmax. He called me back 15 minutes later and I had a check in my hand by 6pm same day.

He called me 3 days later and told me that the power steering failed in the middle of a sweeping right turn and the DIC said “Service Power Steering.” I said, “that sucks. keep me updated”. Later on he said that the car reset itself and was driving fine. He stopped driving the car.

In the end, the car costed me around $50k to own and drive for 2-1/2 years. When car shopping, I was also looking at 3-pedal Ferrari 360s or 3-pedal Lamborghini Gallardos. I figured I’d be better of supporting the cause by buying a brand new 3-pedal Z06 (save the manuals by buying new) and wouldn’t have to worry about costly repairs, since the car had a warranty. The car costed ~$50/hour to drive. Not cool for the “American Working Man’s Sports Car.”

Anyways, I got about $4k in equity back. I bought the car on a 100%, 5-year loan, so my 2-1/2 years of $1,400/month car payments went almost entirely towards depreciation. In total, the car had almost two months of downtime due to reliability/GM issues and another month while I had to save up for another set of tires. It really sucks taking the bus and Ubers while owning a new car that costs ~$60/day to own and drive.

I just bought a manual E39 wagon with 156k miles in relatively poor condition and couldn’t be happier (something something driving a slow car fast). I also learned that the public transportation in my area is amazing and now regularly take the bus & metro to work, even though I own a car. My commute takes me 10 minutes longer total, but I can sit and watch YouTube on my phone the entire trip. Plus, I’m helping the environment. So, there’s some positives.

The worst part about this ordeal was GM’s poor customer service. Fuck them. I could write another rant 3x as long as this one about the frustration with dealing with them. Again, this is coming from someone who’s owned 5 Corvettes.

I’m taking a break from expensive cars for a while (my beloved C5Z is for sale on consignment at a friend's dealership). My next big car purchase is likely going to be a 996 Turbo or a super clean E39 M5. I figure both of these are around $40-$45k and even though they’re 15+ years old, should cause me less headache than my brand new GM POS. At least when they break, they’re worth fixing and I don’t have to worry about a company reneging or string-betting on their warranty promises.

Here’s a few pictures of the car. Not gonna lie, it looked pretty and I had some great experiences with it:

https://imgur.com/a/wg64ueR

0 notes

Link

I bought my plastic broom in the frenzied cleaning portion of my last apartment move. The amount of time and energy I expended trying to decide which broom to buy lasted the duration of my walk to the local Duane Reade, plus the short trip to the cash register. It cost maybe $10.

This is one corner of the American broom market: the unromantic, inexpensive corner many of us are familiar with. For the same price, you could also go to Home Depot and get a humble, conventional version made from broom corn, the straw-like plant also known as sorghum that yellows as it ages. But work your way up the pricing scale — and onto the websites of artists and individuals who make brooms by hand — and you’ll find gangly brooms made from found wood, pleasingly curved hand brooms made from ash and horsehair, thick palm brooms imported from Japan, and classic Shaker brooms with gleaming, octagonal walnut handles. If you want, you can spend $70 or $95 or even $350 on a broom.

The people who make and sell these kinds of brooms say they want to see them in use, and hope that the brooms’ craftsmanship and elevated design will inspire owners to leave them out as decoration when they’re not being used to sweep the floor. But because of its functional (and often gendered) nature, the broom is an everyday object that kicks up a lot of sticky questions when it collides with the artisanal movement.

The complications run along two intersecting axes: price and design. How much should a broom cost? How much should a broom cost if it occupies the blurry space between craft and art? What does it say about divisions of wealth and labor when a person spends hundreds of dollars on a household tool only to hang it on their wall like a work of art? And if a person has no intention of using a broom to sweep their floor — if, say, they hire a cleaning service to do that work — is buying one an act of fetishization?

On the flip side, what’s it to us if someone wants to make cleaning their home a more pleasurable experience? Amazon is big enough; isn’t it a good thing to support individual craftspeople and slower, small-scale production?

It’s worth asking these questions because, anecdotally, I’ve noticed that friends and acquaintances have reactions to the idea of fancy brooms. Some are scandalized. Some are amused, because the thought of someone getting into small-batch broom-making in 2018 seems like a plot line out of Broad City or Portlandia. Clearly, there’s something there. What’s more, you could run the same arguments for any number of artisanal household objects. Brooms are just the example we’ll work with.

In the spring of 2017, Erin Rouse quit her job at the lighting design firm Lindsey Adelman to make brooms full time. She picked up the skill during her time in that job, which allowed employees to study in workshops around the world. She went to the Canterbury Shaker Village in New Hampshire, where she studied with a master broomsquire, the technical term for a broom-maker.

At $80 for a hand broom and $200 for a full-size version, which can reach $350 with a pleated skirt and handle cover, Rouse’s brooms aren’t cheap. Assuming all of her materials are prepped and ready to go — the process of cleaning and sorting by size a 100-pound batch of broom corn can take three or four days — she can make one in roughly two hours, plus the time required to trim the broom and sew a skirt and sheath. If she’s also dyeing the broom, that adds another five days to its production time.

Erin Rouse’s broom-making studio in Brooklyn houses equipment dating to the late 19th century. Custodian Studio

The Brooklyn studio that Rouse shares with a handful of other artists houses a foot-powered machine that likely dates to the 1890s, which rotates a broom by its handle, allowing Rouse to build up its sweeping end layer by layer, and a heavy vise that stands at hip height. It clamps down on the broom, sandwiching a round bunch of bristles such that the broom-maker can stitch it into a more efficient flat shape with a large needle. This vise was a game changer when the Shakers developed it in the late 18th century, and resulted in the style of brooms most Americans know today.

Though Rouse uses traditional American broom-making materials and techniques, she sees her brooms as functional sculptures. She envisions lumpy wooden handles with “a sumptuous little belly,” a bizarre and wonderful mental image. She offers add-ons for her brooms, like fabric skirts and sheaths.

Having been in business officially for less than a year, and in a market that is by nature fairly small, Rouse is still figuring out who her customer is.

“So far it’s been women who are older than me, who are interested in design and interiors. It tends to be established professional ladies, and they’re buying them because it’s functional sculpture,” Rouse says. “I think the more candid clients will tell me that they’re going to hang it as a decoration, but I have sold brooms that people tell me are in use.”

Hannah Beatrice Quinn, a San Francisco-based broom-maker who started making brooms five years ago, says hers land best with an older audience too. Her customers are in their late 20s and early 30s at the very least — people with disposable income and homes they’re invested in. When younger people buy her brooms, it’s usually because they have a keen interest in design or art.

The complication of domestic work being perceived as women’s work is an active presence in Rouse and Quinn’s businesses. As a designer, Rouse wants to engage with that fraught history. Quinn, meanwhile, has noticed that male customers who want to buy a broom as a gift for a woman often question the appropriateness of doing so, worrying that it will send the wrong message about her role in society.

Beyond their symbolism, brooms are, of course, used for sweeping. And because cleaning is not a high-paying endeavor — whether it’s done for free by the person residing in that home or outsourced to a professional — price point is where the conversation around brooms gets tricky.

Rouse and Quinn don’t have the cost-saving benefit of large-scale production, and they are both conscious of the prices of their brooms. Rouse recently knocked hers down from $400 to $350 at the maximum, and started making the less expensive hand brooms because she wanted to offer something that her friends could buy. Quinn sells a smaller $32 version of her brooms, which cost $70 for a full-size version.

At Custodian Studio, Erin Rouse’s broom business, $350 will get you a broom, plus a skirt and sheath. Custodian Studio

There are people willing to pay good money for a beautiful, well-made broom. Hilary Robertson, a New York-based interior stylist and set designer, is the target audience for that.

“I don’t really want to own anything that I don’t find beautiful, even if it’s a washing-up bowl,” Robertson says over the phone. “That’s my business, and the way I live.”

She recently bought one of Rouse’s brooms for her weekend home in Connecticut, an old schoolhouse with an extension. It has stone floors that get dusty very quickly, so Robertson needed a broom, and it has very little storage space, so she needed that broom to look especially good. Indeed, anyone who’s buying a luxury broom is doing so because they consider it part of their furniture, Robertson says. But that doesn’t mean it’s a choice lightly made.

“I think it’s not something you just say, ‘Oh, yeah, a $400 broom, sure. I’ll have one of those,’” she says. “It’s not a throwaway purchase.”

Which, interestingly, is exactly what happened to my $10 Duane Reade broom. It leans against my refrigerator next to a Swiffer that gets all the action. I never use the broom; when I do, a fluffy mass of hair and dust bunnies gathers in its blue straws, many which stick out at odd angles, helplessly raking the air.

Why do we even care how much a broom costs? It is a known fact in the world of consumer products that if a thing exists, a wildly expensive version of that thing exists too. You can pay $1,650 for a pen. And yet when we’re not accustomed to thinking of an item as an indulgence, a luxury version of it trips our brain’s alarm system. This is why we’re appalled (and, in our horror, sometimes delighted) by Goop gift guides every winter, with their 18-karat gold, $125,000 barbells. How much more unrelatable can you get?

“Because there are brooms for $12 now that you can get on Amazon, people think it’s somehow inappropriate to buy something more expensive,” says Robin Standefer, co-owner of the Roman and Williams Guild in New York, which sells handmade brooms from Japan and Sweden. “I’m hoping to reframe some of that. It’s supporting a micro-economy — a global one with people making things for real use — and these are functional objects. It’s not some cultural prop.”

Standefer runs Roman and Williams with her partner Stephen Alesch. They’ve worked on interiors for some of the most recognizable hotels, restaurants, and clubs in the country: the Standard, the Ace, the Boom Boom Room. These are beautiful, expensive places, and the Guild sells beautiful, expensive goods, like $250 rabbit pillows, $400 glass vases that shimmer with subtle texture, and delightfully knobbly, polka-dotted $220 pots. But Standefer is plainly uninterested in selling brooms as art objects.

“They’re meant to be used, and they happen to be made in a rigorous way,” Standefer says. “We sell [our Japanese broom, currently sold out] for $82. People say we could sell it for $300, that it’s an art object. But when you do, you’re elevating it to a fetish object.”

That is exactly what she doesn’t want to do. Standefer is one of a vocal faction of people in the retail world advocating for goods that are better made and long-lasting, if more expensive. Her feeling is that these unbelievably well-made brooms can be used for decades, saving the shopper money in the long run.

To convince shoppers of the same, she priced the Guild’s brooms lower than she usually would, slimming their margins in favor of making them more accessible to people used to Amazon’s bargains.

“I really believe that you could have this broom for 20 years or more,” says Standefer. “Our consumer economy is about replacing things. This is a big reframing.”

An inky model from Custodian Studio, Erin Rouse’s broom business. Custodian Studio

What we’re willing to pay for is inevitably a matter of what we’ve been taught to pay for — what it’s in fashion to pay for. Right now, people are willing to shell out for ceramics classes (a balm for those who spend too much time on their phones and computers) and handmade ceramics, many of which cost much more than those brooms. Despite features this year in T magazine and on the Strategist, New York magazine’s shopping site, artisanal brooms aren’t quite there yet.

“I think a fancy broom is untested in the way that a very fancy ceramic vessel has been proven,” says Rouse when I ask whether she’s started wholesaling to any retailers (she hasn’t). “You can definitely sell a $1,200 vessel — you can probably sell out of them — but a $400 broom is a little riskier. That would be why I’m making all these hand brooms, so there’s a lower-priced product to prove demand.”

That’s why Standefer sets a lower profit margin on the brooms she sells: We don’t know intuitively that we want meticulously crafted brooms for our homes. But one day, maybe even in a not-so-distant future, we might.

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Original Source -> Artisanal brooms exist, and they cost up to $350

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Text

The 2017 Baseball Memorabilia Haul

I’ve delayed this long enough. 2016 was a big year for me in terms of no longer just buying cards of guys from the 1980′s and 1990′s. I ventured out and started spending money on stars playing today, and prospects for the future! I continued that this year, but also filled out a lot more players on that 1980/1990 list that I’ve been working on!

2017 was by far my biggest year ever in terms of collecting cards. The most I’ve ever gotten in a single year. I hope you enjoy checkin’ em out!!!

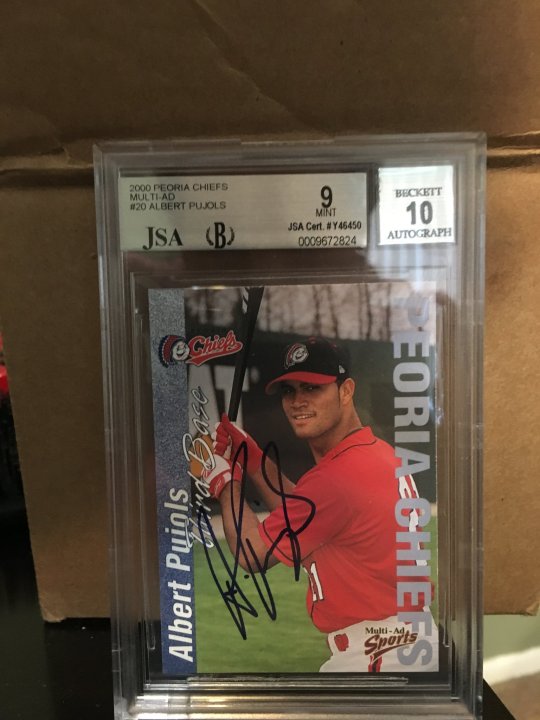

FIRST THINGS FIRST. THE ALBERT PUJOLS FROM LAST YEAR.

BIG BOY CAME BACK A 9! Which is crazy good! I’m ecstatic about it. The Corners sub-graded an 8.5 and the Edges graded a 9, while the Surface & Centering hit at 9.5. Part of me wants to do a re-grade to see if the corners and edges could possibly come back a bit higher... but hey. a 9 is still insane. And that auto is great.

Albert is currently looking like he’s at the end of his career, but even if he sticks around for another several years being basically unplayable - his peak was so nuts he will still be regarded as one of the best players in Baseball history.

Now to the new additions to the collection, by order of when I received them:

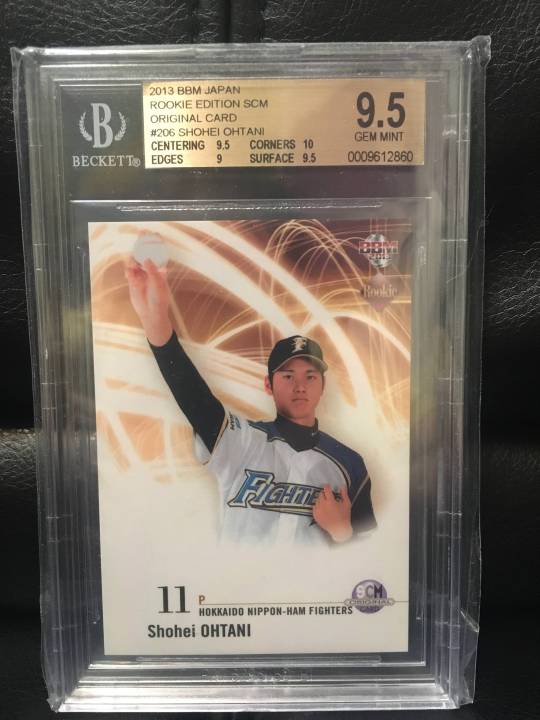

01.) 2013 BBM SCM Original #206 - Shohei Ohtani (BGS 9.5)

Newest big star in MLB. Shohei Ohtani is an awesome pitcher, and what makes him unique is he’s also great with a bat. Was desperately hoping he was going to sign with the Yankees, but unfortunately he came in immediately deciding he didn’t want to live on the East Coast. Which sucks. Boo. But hey, I hope he still does good. Just not against us.

02.) 1989 Donruss #635 - Curt Schilling (PSA 10)

Curt Schilling is a piece of crap. A terrible person, with terrible opinions, and his attitude keeping him out of the Hall of Fame so far has brought me some great joy.

With that said he’s one of the best pitchers of all time. His unpopularity atm made this purchase very easy on my wallet.

03.) 1983 Fritsch #013 - Jose Canseco (PSA 10)

Before Jose Canseco lost his finger and opened up a can of worms about steroids, he hit a lot of dingers and was very popular. He also is a butthead. I probably spent too much on this one, but eh. He’s off the list now.

04.) 1988 CMC Calgary Cannons #034 - Edgar Martinez (PSA 10)

I’d been wanting an Edgar Martinez card for a long time. He has no rookie card that really looks great though. This was my favorite of the bunch I had seen.

Edgar is one of the best designated hitters ever. Not the best, but at least top 3. Deserves to be in the hall, and I’m glad he’s taken a big jump in the votes and looks like he could get in next year!

05.) 1978 Burger King Tigers #013 - Lou Whitaker (PSA 8)

I had a PSA 8.5 of Alan Trammell. You can’t have just Trammell though without Whitaker. For 19 years, those 2 were the starting 2B and SS for the Detroit Tigers, and they were damn good. Trammell & Morris just made the Hall of Fame thanks to the Veterans Committee, but left Whitaker off the ballot in a decision that was just baffling. Hopefully Whitaker gets his due soon enough. He’s arguably the best of those 3.

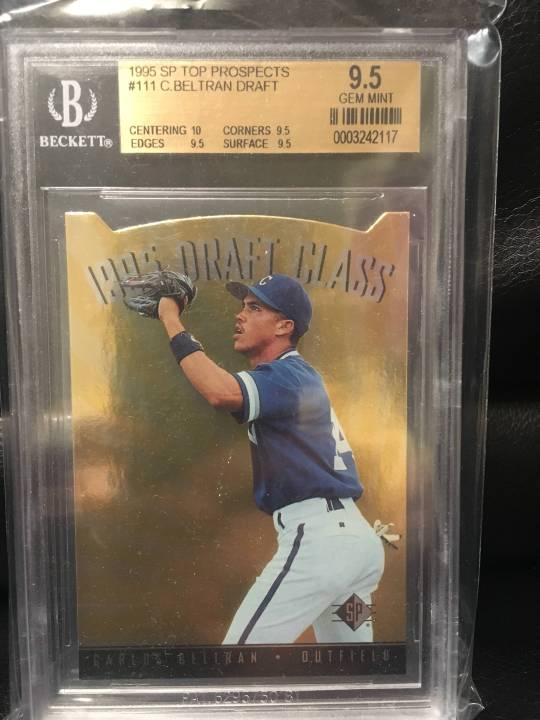

06.) 1995 Upper Deck SP Top Prospects #011 - Carlos Beltran (BGS 9.5)

Carlossss!!! The very next day after I purchased a Lou Whitaker, I got this card. No real reason other than I really like Beltran. I don’t think he’ll ever get Hall of Fame votes or anything, but he was a big player in New York.

I don’t like the Astros, but I’m glad he finally got his WS Ring before retirement.

07.) 1998 Bowman’s Best #120 - Adrian Beltre (BGS 9.5, AUTO 10)

This is it. The biggest purchase I made this year, and by far the most I’ve ever spent on a single card. A tough grade on its own, but I managed to get one with the Topps Certified Auto as well!

I got this card in March. Beltre went into the season with 58 more hits to go before he reached a career milestone of 3000. He ended up going into the season with an injury that kept him out for a little less than half the season. Because of that, I was super worried he wasn’t going to come into the season very productive - but in 94 games he was still able to hit .312/.383/.532 and reach the 3000 hit mark.

He’s currently sitting on 462 Home Runs also. With only one more year left on his Rangers contract, I don’t know if he’s going to be able to make it to 500 before his career his up. But who knows, if he has another stellar year this year - maybe he’ll get signed to a few more years and hit just enough to reach another milestone.

I may have spent a lot on this guy, but I can see the value of it being much higher in the future.

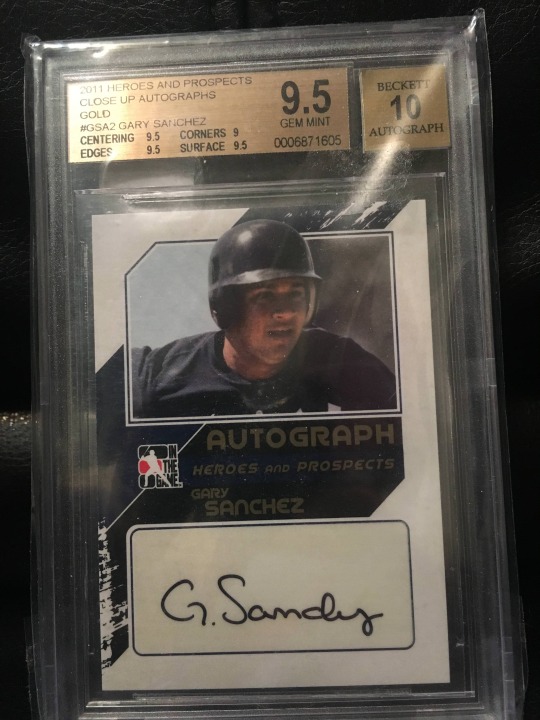

08.) 2011 Heroes & Prospects #GSA2 - Gary Sanchez (BGS 9.5, AUTO 10)

El Gary.

Gary Sanchez rolled into the 2016 season late and in only 53 games put up a really compelling case for Rookie of the Year. Unfortunately he didn’t get it.

Gary wasn’t as GODLY in 2017 as he was at the end of 2016, but he showed some real big sparks of greatness and I think he’ll be incredibly fun to watch for years to come.

This card is the GOLD Version of this set. Only 10 of these exist. Only 2 have been graded a 9.5. I’m happy to have one.

09.) 2000 SPx #094 - Alfonso Soriano (PSA 10)

Alfonso Soriano came up as a 2nd Baseman on the New York Yankees. In 2002 and 2003 he mashed a lot of taters. We then traded him for Alex Rodriguez.

Soriano spent most of his career on the Chicago Cubs where he was... pretty mediocre. He hit dingers but didn’t get on base a ton. He ended his career with over 2000 hits and over 400 home runs. I thought he was fun.

10.) 1983 Topps #083 - Ryne Sandberg (BGS 9.5)

Ryne Sandberg played his career on the Chicago Cubs as a second baseman. He was really good. He could hit dingers and also defend really well.

A PSA 10 of this card cost over 300. Nutty. I ended up settling for a BGS 9.5 since I was able to get it for much cheaper. If PSA did raw grade reviews I might see if I could get it converted to a PSA 10... but they don’t. Hrm. Oh well!

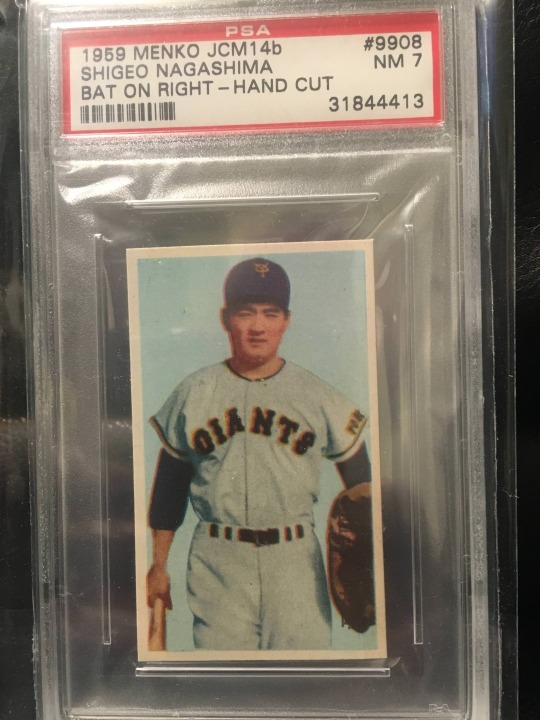

11.) 1959 Menko #JCM14b - Shigeo Nagashima (PSA 7, HAND CUT)

This is the coolest card I got all year.

Shigeo Nagashima is the most popular player in the history of Japanese baseball. More popular than his teammate Sadaharu Oh, the Home Run King. This isn’t a rookie card unfortunately! It’s a second year card. However I got it because last year I was able to nab a Sadaharu Oh rookie from this exact same set! Put them next to each other, and they match very well. A rookie card of Nagashima would be really cool - but I’m really really happy with this one!

12.) 2013 Elite Extra Edition #071 - Gleyber Torres (BGS 9.5, AUTO 10)

Gleyber Torres will be on the Yankees this year. Gleyber Torres will be great. I am ready for The Yankees to win the World Series.

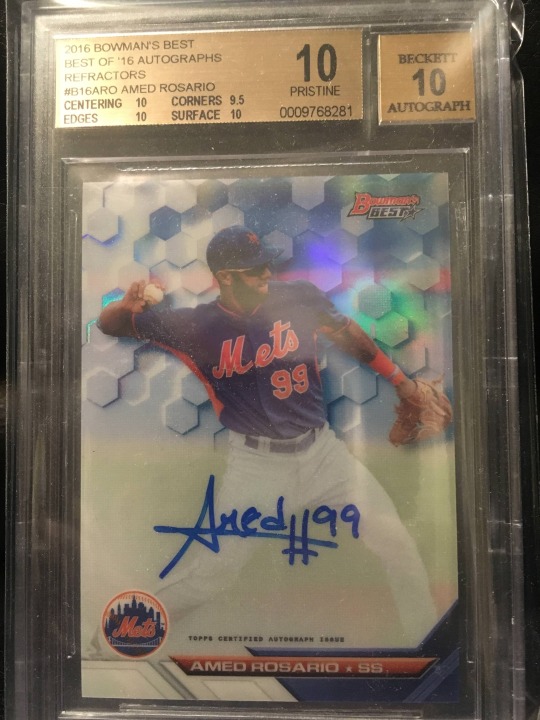

13.) 2016 Bowman’s Best #B16ARO - Amed Rosario (BGS 10, AUTO 10)

The Mets had a million problems last year and it took them forever before they called up Amed. He wasn’t great, but he’s young and has a good shot to bounce back. At least I hope. Also, that’s a sick auto.

14.) 1978 Burger King Tigers #015 - Alan Trammell (PSA 9)

I already had a PSA 8.5 of Alan Trammell. But I wanted a higher grade. So I got this one!

15.) 1987 Leaf #043 - Rafael Palmeiro (PSA 10)

Rafael Palmeiro was a very talented player. He was a lock for the Hall of Fame. But then he did something very dumb.

His downfall came when he testified to a room of Congressmen that he had never used Steroids, and then only 6 weeks later he failed a drug test.

He was a lock for the Hall of Fame. But the announcement that he failed a test killed his good standing with fans. Despite being 1 of only 5 players to have 3000 hits and over 500 Home Runs, he fell off the Hall of Fame ballot on his 4th year with only 4.4% of people voting for him.

16.) 1993 Upper Deck SP #273 - Johnny Damon (PSA 10)

Johnny Damon was a good player. Not great, but very good for a long time. This was his best moment. He never did anything big on the Red Sox, no siree.

17.) Some Didi Gregorius

The Bowman with the facsimile is a rookie card. The card next to that has a real autograph! Both of these cards came with the purchase of an autographed ticket from Didi Gregorius’ first game in Yankee Stadium. He hit a home run on the first pitch he saw.

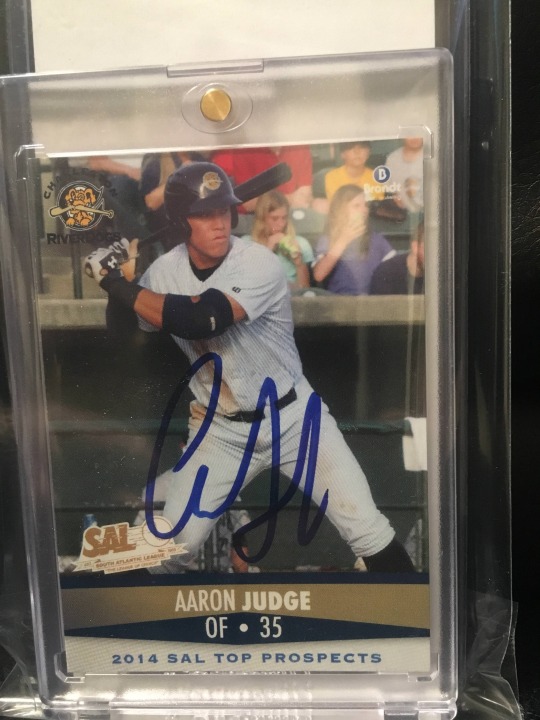

18.) 2014 Sal Top Prospects #017 - Aaron Judge (JSA AUTO)

Aaron Judge is big, and strong, and also my friend. I don’t think this card is really in the best condition to be graded, which is why I haven’t done that yet - but I really like the photo and the Autograph. You can tell he’s a big boy. I like it very much.

19.) 2010 Bowman Sterling #025 - Carlos Santana (BGS 9.5, AUTO 10)

Not his biggest card or anything - but for a First Baseman who has been nothing but good his entire career, this card was cheap as hell. Not one of my favorite players, but deal was a bit too good to pass up.

20.) 2003 Upper Deck USA Baseball #J-5 - Justin Verlander (PSA 10)

I don’t think I’d have been able to get this card for this cheap had Verlander not been on the Tigers still. One of the better pitchers of this era, and while he looked to be falling apart in 2014 - he’s been great every year after. Probably only needs a couple more good-not-great years and he’s pretty much a lock for the Hall.

21.) 2005 Upper Deck USA Baseball #DB-GU - Dellin Betances

A throw in with another card I had purchased. I forget which. I hope Betances can bounce back after falling apart last year because he is very fun when he is striking out everybody.

22.) 2008 Upper Deck USA Baseball #QA-SS - Stephen Strasburg (BGS 8.5, AUTO 10)

Aaaaugh!!! The 8.5 on this card KILLS ME. But despite that, I’m happy to have it. Strasburg was one of only 2 big current players on my list when I first started collecting cards again over 5 years ago. His popularity and scouting reports which pretty much guaranteed he was going to be a huge star made all of his cards wayyyyy out of my price range.

Strasburg is still a very popular player, and still very good. In 2015 & 2016 he wasn’t able to get any more than 150 IP though. Take that and add in that his ERA had been steadily climbing with each year, and this card became affordable.

However, in 2017, Strasburg had a real bounceback year. 175 Innings Pitched, and an ERA of 2.52 in a year where offense was the highlight.

I may just get this encased with a grade for the Autograph. I really love the rarity of this card. Only 20 in existence, great autograph, and it spells his name wrong. A lot to like!

23.) 2010 Upper Deck USA Baseball #USA-62 - Corey Seager (JSA AUTO)

This was a throw in if I added 10 dollars to the Strasburg card. Corey Seager is the starting shortstop for the LA Dodgers. He’s really damn good, and will probably be good for at least another 10 years.

24.) 2008 Bowman Chrome #BDP48 - David Robertson

DEALIN’ DAVE IS BACK ON THE YANKS. I love him. I’m planning to get it slabbed very very soon. That is all.

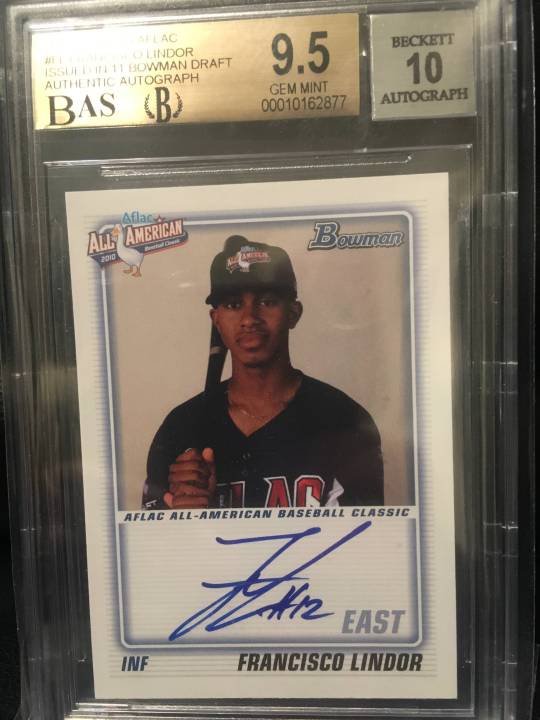

25.) 2010 Bowman AFLAC #FL - Francisco Lindor (BGS 9.5, AUTO 10)

Francisco Lindor had a rough start to the year, hitting only .252/.312/.456 in the first half. That’s rough when you supposedly had turned down an 100 million dollar offer at the start of the year.

However, he bounced back in the second half hitting .298/.366/.563. Like Corey Seager, he’s probably going to be a great player for years to come.

I don’t think I got as good a deal on this card as I did on the Joey Votto that I bought at the end of last year - but for the price I got for it... it’s gotta be up there. A really great way to end the year!

Andddd that was the last one! Hope you enjoyed.

#Baseball Cards#Baseball#MLB#NPB#Topps#Bowman#Leaf#Donruss#Upper Deck#Burger King#Panini#Prospects#Rookies#Menko#Shigeo Nagashima#Lou Whitaker#Alan Trammell#Jose Canseco#Ryne Sandberg#Rafael Palmeiro#Curt Schilling#Edgar Martinez#Johnny Damon#Carlos Beltran#Adrian Beltre#Alfonso Soriano#Justin Verlander#Dellin Betances#David Robertson#Stephen Strasburg

0 notes

Text

See previous post 1 and post 2 in this series, or related posts to this month-long trip here and here.

The drive to Ranomafana is about 12 hours. After experiencing the Tana roads, I thought maybe it was close via bad roads, but it’s really 12 hours in a 4WD at relatively high speed but through winding roads. For 12 hours, I was tossed side to side, tires screeching on the road.

I was very passive in this adventure, which is ironic when I think that this project arose because the TMSE PTA asked me to offer an anthropology course several years ago when my kids were in 3rd grade. I didn’t want to do it because I didn’t have the time to take on any more service, but I wanted to do it because I wanted to be able to share what I do with my kids and help their school. I remember discussing it with DoVeanna Fulton, then chair of Gender and Race Studies, whose son had been a classmate of my kids. She said, ‘if you wait till you have more time, will your kids still want you to do it and will there still be an opportunity?’ Thank you, DoVeanna.

So, Duke Beasley and I collaborated on the course that first time, and it went well that first time. But only my sons Lux and Jagger took it. The next year, Bailey wanted to take it, so Duke and I offered it again. Still, I was never going to do it again, but it was popular and I’d got a curriculum developed that I could hand off to students to teach, so I kept it going. Later, I recognized an opportunity to turn it into a service learning course when I saw an application to develop a community service course. At the time, I had another course in mind and didn’t realize I was already doing one. Then later, Jason DeCaro came across a Wenner-Gren Foundation grant call because he was flying to New York and would be meeting with president Leslie Aiello. So I threw together a proposal, got feedback from her, tweaked the proposal, and got funding for this project.

I met Dustin Eirdosh, who has been my liaison on this Madagascar collaboration, just as serendipitously in a way. He was working with David Sloan Wilson and the EvoS Consortium for resources and in touch with Becky Burch. I started contacting Dustin to brainstorm about collaboration potential and saw that his energy is similar to mine. So I say “passive” when I describe my activity in Madagascar, but what I really seem to do is flap my wings hard and fast like a hummingbird until an opening appears, then I hit it hard and without hesitation.

I set this trip up without any real game plan. I deferred to Dustin and Josia to give me a lead that I would then take. So it was Dustin who suggested a trip to Ranomafana and Josia who booked the driver for me. The first one got in an accident the day before, so she arranged the second one at the last minute. She used the same company she books for her own research, but I’m not sure that that was the same in both cases.

The driver was going to cost 140,000 ariary/day (around $50/day, 460,000 ari total). Gas would cost me another 420,000 ari for the trip. Then I would need hotel for 3 nights, which I found for 100,000/night. That’s about $400, not including food or other things. That’s a sizable amount of money, considering I had no specific plans of who I was going to talk to or if I would even be able to get a meeting and had very little money with me.

This was covered by grant funding, but universities never want to give you your grant money up front. They want you to pay it out first and reimburse you. Presumably, there’s liability involved. I also think it’s being used in some slush fund somewhere or earning interest. When I asked for a $1,000 advance, I was treated like I was asking for money to go binge drinking. I was told I was asking for a LOAN and that it is against state policy to LOAN employees travel funds. Load of crap. We researchers have rents or mortgages to pay back home when we travel. Sorry to tell the world, but you don’t get much financial compensation for a PhD in the social sciences and humanities. I’m so deep in debt from student loans, I will never be free (see the notice of being served because of my student loan debt from the first day of this trip).

So $400 is a lot for money for me, as I was traveling exclusively cash and carry, with nothing in a bank account I could access and no place in Madagascar takes credit cards. What an adventure, right? This means I was riding for 12 hours in a car to meet with people I didn’t know would meet with me about what I didn’t exactly know and not sure I’d have enough money to pay the driver when I got back.

Jao gripping the wheel.

But this is not a mystery story, so I’ll let you off the hook. I stressed on the ride, tallying up my expenses, especially when Jao, my driver, stopped at a tourist hotel restaurant for lunch to eat “normal” food. Normal for me, is what I think he meant. Also, “clean,” he said. But it ended up costing me a pretty penny. The next meal was a little better, but I had to keep pushing him: “Let me worry about the food poisoning. Let’s eat Malagasy food at hotelys.”

If there are traditional musicians selling their CDs at the hotel restaurant, it probably costs more than you want to spend for a quick road stop. Or if there are old New Yorkers talking loudly at the table behind them.

And I had to ask Jao to help me change currency so I could pay him. Banks there won’t change $100 bills, which is all I had. And we were returning on a Sunday when everything was closed. So we had to meet a black market money changer by the side of the road on the way back into town. I don’t mean to make this sound in any way like Romancing the Stone or Indiana Jones crap. Other field researchers have a million such stories, as do all the people who live in such countries. And they are unfortunately not rare in the world. I borrowed my money belt and steel-reinforced bag from a friend who regaled me with stories of dealing with a cholera outbreak, regularly carrying vast quantities of cash on her to cover field school expenses, meeting sketchy money changers in strange homes, and drinking with murderous warlords during her field seasons. It’s all a matter of perspective. But this time, I was in Africa, while she was back home attending the premier of Beauty and the Beast!

I took lots of photos as Jao drove in silence. He listened to music all the way back. At the first, I felt bad he had obviously not felt comfortable playing music in the car until I heard him playing Otis Redding and asked him to turn it up. We listened to that and a Beatles album on the way back, which I loved singing along to, but then the next 9 hours were taken up by bad 80s hair metal and Celine Dion. And I was stuck with only Neil Gaiman’s new Norse Mythology as my Audible book. It was interesting for about an hour, but then stories of Thor’s dumb brutishness and Loki’s selfish mischief just lulled me to sleep.

However, the Betsiloa countryside was beautiful. They are the tribe that occupies the highland south of Tana. Their homes are tall and made of red brick that matches the red clay of the ground. Their terracing for rice, corn, and other produce is more distinctive than terracing elsewhere (I got great photos of this but—foreshadowing—those photos are sadly no longer with me). Apparently, they get three annual harvest, where other only get 1-2.

As we passed through Antsirabe, suddenly there were colorful tricycle taxis everywhere. “City of Pouse-pouse,” Jao told me. The region is resplendent with bicycles and pouse-pouses. I couldn’t get enough photos of them and the colorful markets (alas, many of those also lost with someone on the road to perdition—okay, maybe a little harsh, but I’m very annoyed about it).

We rolled into Ranomafana around 4, a bit earlier than expected. I got a place at Hotel Cristo, which came recommended both by Lonely Planet and Josia and Rija. It turned out to be very lovely.

Again, in true colonial style, I sat on the veranda watching the sunset over the rainforest and Namorona River, while people spoke Dutch and English nearby, and brown-skinned hotel employees brought me a double expresso. But at least they owned the place this time. Dear Malinowski…

Anthropology is Elemental is currently funded by a grant from the Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Repost from April 2017 on Bama Anthro Blog Network. See that post for photo galleries missing above: https://wp.me/p2SN82-h8

AiE in Madagascar III: Road to Ranomafana See previous post 1 and post 2 in this series, or related posts to this month-long trip…

0 notes

Text

Miami's Publicly-Funded Ballpark Won't Make Marlins Owner Jeff Loria Richer

Tomorrow night's MLB All-Star Game in Miami will be, above all else, a celebration of shattered hopes and dreams:

The raison d'etre for Miami being awarded the game—the hulking, endomed Marlins Park which opened in 2012 after a many-year wait—remains largely unloved, and is most-known by baseball fans for its minuscule crowds and much-maligned home-run sculpture in center field.

The Marlins themselves have yet to post a winning record in their new home.

Miami taxpayers invested hundreds of millions of dollars into stadium construction—total public cost will end up at roughly $1.2 billion over time, or around $900 million in present value dollars—for purposes of "revitalizing" the building's surrounding neighborhood, which according to the Miami Herald remains "pocked with small strip malls, empty lots, and vacant buildings."

Oh yeah, and on top of the above, Jeffrey Loria, the Marlins' owner, is reportedly set to sell a team that he bought for $158 million in 2002 for a whopping $1.2 billion.

The idea that Loria is about to cash in on taxpayer largesse is enough to leave Miami-Dade County Mayor Carlos Gimenez mighty steamed. "I would think [Loria will] walk away with $500 million in his pocket" after paying off various debts, Gimenez told the New York Times last week. "It sticks in my craw."

Blowing public money on an unpopular stadium while the team's owner laughs all the way to the bank is worth getting ticked about. But as dislikable as Loria has been as an owner—remember, he once responded to declining crowds by suing season ticketholders who refused to renew—is it really true that he's getting rich thanks to Marlins Park?

Probably not. In fact, new ballparks don't seem to make baseball franchises much more valuable.

Marlins Park is located in Miami's Little Havana neighborhood. Photo by Robert Mayer-USA Today Sports

To understand why, let's first figure out just how much money Loria will walk away with. It's been widely reported that Loria's Marlins are $400 million in debt; no one exactly knows why, but let's leave that aside for the moment. Subtract that from the team's reported $1.2 billion sale price—it was going to be $1.3 billion, until Derek Jeter and Jeb Bush had a falling-out—and Loria is set to clear $800 million, a cool 406 percent profit on his $158 million purchase of the Fish. Annualize the same number—break it down by yearly gain, as if it were a savings account—and the Marlins under Loria have appreciated in value by 11.41 percent a year.

So, is that a lot?

One of the problems with determining a pro sports team's value is that they're not sold very often—you can't exactly look at all the other MLB teams bought in 2002 and sold in 2017 and do an apples-to-apples comparison. The closest analogue by sale date are the Los Angeles Dodgers, which were sold by Rupert Murdoch's NewsCorp to parking lot czar Frank McCourt in 2004 for $430 million; McCourt turned around and sold the team in 2012 to an assortment of investors (most notably by name if not by dollar value, Magic Johnson) for $2 billion. That makes for an annualized return of 21.16 percent—almost double the Marlins' appreciation, and for a franchise that has been playing in the same stadium since 1962.

That's just one team, though. For more data points, we can turn to Forbes' annual team value estimates. According to the magazine, the average MLB team in 2002 was worth $286 million. This year, with ten teams having opened new stadiums in the interim and 20 still playing in the same venues, that number is $1.54 billion—an annualized return of 11.87 percent.

In other words, Loria's windfall is almost exactly the league average for all MLB teams, whether they received new stadiums or not.

Now, if those estimated team values seem too dicey, we can look at Forbes' annual team revenue figures, which we believe are even more accurate, thanks to Marlins financial documents leaked to Deadspin in 2010 that almost exactly matched the magazine's numbers. Between 2007 and 2016, the Marlins' annual revenue (after accounting for Loria's own stadium payments) rose from $128 million to $206 million, an increase of 61 percent. Over the same time, the average MLB team's revenue went from $183 million to $292 million, an increase of 60 percent; even the Marlins' famously stadium-deprived cross-state rivals, the Tampa Bay Rays, saw their annual revenue go from $138 million to $205 million, a 49 percent jump.

This all paints a very different picture than the one imagined by Gimenez: Not of Loria cashing in thanks to a new stadium, but of everybody who owns an MLB team seeing them soar in value regardless of whether you play in a shiny new facility or a boring old dump.

When you're waiting to close the big sale before upgrading your phone. Photo by Jasen Vinlove-USA TODAY Sports

There are a bunch of reasons for rising team valuations. First, television broadcast revenues have gone through the roof, thanks to cable providers discovering that sports is the only thing that people will pay to watch live. "Money from things other than selling tickets is the fastest growing component of revenue," says Stanford sports economist Roger Noll, noting that local broadcast revenues in baseball have also soared in recent years.

Then there's the billionaire glut problem: The number of pro sports teams available for sale is rising very slowly, but the number of rich dudes eager to own one has soared astronomically in the 21st century. (I don't know if Thomas Piketty is a sports fan, but if so he has something new to complain about). This, says Noll, creates scenarios like Microsoft magnate Steve Ballmer spending $2 billion to buy the Los Angeles Clippers, just because he had money to burn and there was only one team up for sale.