#mycenaean linear b

Text

Mycenaean Greek

(and examples of lexical evolution to Modern Greek)

Mycenaean Greek is the most ancient attested form of the Greek language (16th to 12th centuries BC). The language is preserved in inscriptions of Linear B, a script first attested on Crete before the 14th century BC. The tablets long remained undeciphered and many languages were suggested for them until Michael Ventris, building on the extensive work of Alice Kober, deciphered the script in 1952. This turn of events has made Greek officially the oldest recorded living language in the world.

What does this mean though? Does it mean that a Modern Greek could speak to a resurrected Mycenaean Greek and have an effortless chat? Well obviously not. But we are talking about the linear evolution of one single language (with its dialects) throughout time that was associated with one ethnic group, without any parallel development of other related languages falling in the same lingual branch whatsoever.

Are we sure it was Greek though? At this point, yes, we are. Linguists have found in Mycenaean Greek a lot of the expected drops and innovations that individualised the Hellenic branch from the mother Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). In other words, it falls right between PIE and Archaic Greek and resembles what Proto-Greek is speculated to have been like. According to Wikipedia, Mycenaean Greek had already undergone all the sound changes particular to the Greek language.

Why was it so hard to decipher Linear B and understand it was just very early Greek? Can an average Greek speaker now read Linear B? No. An average Greek speaker cannot read Linear B unless they take into account and train themselves on certain rules and peculiarities that even took specialized linguists ages to realise and get used to. Here's the catch: Linear B was a script inspired by the Minoan Linear A, both of which were found in the Minoan speaking Crete. (Minoan Linear A inscriptions have yet to be deciphered and we know nothing about them.) The Mycenaeans (or was it initially the Minoans???) made only minimal modifications to produce the Linear B script and used it exclusively for practical purposes, namely for accounting lists and inventories. Linear B however was an ideographic and syllabic script that stemmed from a script that originally was not designed to render the Mycenaean Greek language, and thus it could not do it perfectly. In other words, the script itself does not render the Greek words accurately which is what made it extremely hard even for the linguists to decipher these inscriptions. Due to its limited use for utility and not for prose, poetry or any other form of expression, the Mycenaean Greeks likely did not feel compelled to modify the script heavily into some more appropriate, accurate form to cover the language's needs.

Examples of the script's limitations:

I won't mention them all but just to give you an idea that will help you then read the words more easily:

In the syllabic script Linear B, all syllable symbols starting with a consonant obligatorily have a vowel following - they are all open sylllables without exception. Linear B can NOT render two consonants in a row which is a huge handicap because Greek absolutely has consonants occuring in a row. So, in many cases below, you will see that the vowel in the script is actually fake, it did not exist in the actual language, and I might use a strikethrough to help you out with this.

For the same reason, when there are consonants together, at least one of them is often casually skipped in Linear B!

There were no separate symbols for ρ (r) and λ (l). As a result, all r and l sounds are rendered with the r symbol.

Exactly because many Greek words end in σ, ς (sigma), ν (ni), ρ (rho) but in Linear B consonants must absolutely be followed by a vowel, a lot of time the last letter of the words is skipped in the script!

Voiced, voiceless and aspirate consonants all use the same symbols, for example we will see that ka, ha, gha, ga all are written as "ka". Pa, va, fa (pha), all are written as "pa". Te, the are written as "te".

There are numerous other limitations but also elements featured that were later dropped from the Greek language, i.e the semivowels, j, w, the digamma, the labialized velar consonants [ɡʷ, kʷ, kʷʰ], written ⟨q⟩, which are sometimes successfully represented with Linear B. However, that's too advanced for this post. I only gave some very basic, easy guidelines to help you imagine in your mind what the word probably sounded like and how it relates to later stages of Greek, and modern as is the case here. That's why I am also using simpler examples and more preserved vocabulary and no words which include a lot of these early elements which were later dropped or whose decoding is still unclear.

Mycenaean Linear B to Modern Greek vocabulary examples:

a-ke-ro = άγγελος (ágelos, angel. Notice how the ke symbol is representing ge, ro representing lo and the missing ending letter. So keep this in mind and make the needed modifications in your mind with the following examples. Also, angel actually means "messenger", "announcer". In the Christian context, it means "messenger from God", like angels are believed to be. So, that's why it exists in Mycenaean Greek and not because Greeks invented Christianity 15 centuries before Jesus was born XD )

a-ki-ri-ja = άγρια (ághria, wild, plural neuter. Note the strikethrough for the nonexistent vowel)

a-ko-ro = αγρός (aghrós, field)

a-ko-so-ne = άξονες (áksones, axes)

a-na-mo-to = ανάρμοστοι (anármostoi, inappropriate, plural masculine. Note the skipped consonants in the script)

a-ne-mo = ανέμων (anémon, of the winds)

a-ne-ta = άνετα (áneta, comfortable, plural neuter, an 100% here, well done Linear B!)

a-po-te-ra = αμφότερες (amphóteres, or amphóterae in more Archaic Greek, both, plural feminine)

a-pu = από (apó, from)

a-re-ka-sa-da-ra = Αλεξάνδρα (Alexandra)

de-de-me-no = (δε)δεμένο (ðeðeméno, tied, neuter, the double de- is considered too old school, archaic now)

do-ra = δώρα (ðóra, gifts)

do-ro-me-u = δρομεύς (ðroméfs, dromeús in more Archaic Greek, runner)

do-se = δώσει (ðósei, to give, third person singular, subjunctive)

e-ko-me-no = ερχόμενος (erkhómenos, coming, masculine)

e-mi-to = έμμισθο (émmistho, salaried, neuter)

e-ne-ka = ένεκα (éneka, an 100%, thanks to, thanks for)

e-re-mo = έρημος (érimos, could be pronounced éremos in more Archaic Greek, desert)

e-re-u-te-ro-se = ελευθέρωσε (elefthérose, liberated/freed, simple past, third person)

e-ru-to-ro = ερυθρός (erythrós, red, masculine)

e-u-ko-me-no = ευχόμενος (efkhómenos or eukhómenos in more Archaic Greek, wishing, masculine)

qe = και (ke, and)

qi-si-pe-e = ξίφη (xíphi, swords)

i-je-re-ja = ιέρεια (iéreia, priestess)

ka-ko-de-ta = χαλκόδετα (και όχι κακόδετα!) (khalkóðeta, bound with bronze, plural neuter)

ke-ka-u-me-no = κεκαυμένος (kekafménos, kekauménos in more Archaic Greek, burnt, masculine)

ke-ra-me-u = κεραμεύς (keraméfs, kerameús in more Archaic Greek, potter)

ki-to = χιτών (khitón, chiton)

ko-ri-to = Κόρινθος (kórinthos, Corinth)

ku-mi-no = κύμινο (kýmino, cumin)

ku-pa-ri-se-ja = κυπαρίσσια (kyparíssia, cypress trees)

ku-ru-so = χρυσός (khrysós, gold)

ma-te-re = μητέρα (mitéra, mother)

me-ri = μέλι (méli, honey)

me-ta = μετά (metá, after / post)

o-ri-ko = ολίγος (olíghos, little amount, masculine)

pa-ma-ko = φάρμακο (phármako, medicine)

pa-te = πάντες (pántes, everybody / all)

pe-di-ra = πέδιλα (péðila, sandals)

pe-ko-to = πλεκτό (plektó, woven, neuter)

pe-ru-si-ni-wo = περυσινό / περσινό (perysinó or persinó, last year's, neuter)

po-me-ne = ποιμένες (poiménes, shepherds)

po-ro-te-u = Πρωτεύς (Proteus)

po-ru-po-de = πολύποδες (polýpoðes, multi-legged, plural)

ra-pte = ράπτες (ráptes, tailors)

ri-me-ne = λιμένες (liménes, ports)

ta-ta-mo = σταθμός (stathmós, station)

te-o-do-ra = Θεοδώρα (Theodora)

to-ra-ke = θώρακες (thórakes, breastplates)

u-po = υπό (ypó, under)

wi-de = είδε (íðe, saw, simple past, third person singular)

By the way it's killing me that I expected the first words to be decoded in an early civilisation would be stuff like sun, moon, animal, water but we got shit like inappropriate, salaried and station XD

Sources:

gistor.gr

Greek language | Wikipedia

Mycenaean Greek | Wikipedia

Linear B | Wikipedia

John Angelopoulos

Image source

#greece#history#languages#linguistics#greek#greek language#langblr#mycenaean greek#modern greek#greek culture#language stuff#vocabulary#linear b#mycenaean civilization

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classicstober Day 20: Odysseus (𐀃𐀉𐀮𐀄)

Odysseus is one of the most recognizable heroes of Greek mythology, maybe the most recognizable after Heracles/Hercules and various euphemisms (eg Achilles Heel and such). I borrowed Jorge Herran's hairdo for my interpretation of him because Epic has been on my mind and I deeply enjoy his interpretation of the character.

More than any other hero, Odysseus' relationship with his divine patron, Athena, is very close. Some interpretations might even argue too close, and maybe even dangerous…

What can a man say about Odysseus that hasn't already been said before? He is one of those mythological characters that is inescapable if you are dealing with ANY media that handles classical mythology. Polymetis seems to describe both him and his modern interpretations. I can't deny that I have a significant amount of Double Think about this man. To the ancient Greeks he would have been a perfect hero, but today… not so much. He murders without consequence, even if pragmatically, is filled with pride, and while his wife remains the model of chaste patience Odysseus is banging his way around the Mediterranean.

That said, it is very easy to make more palatable modern interpretations of him. He's almost as easy to sanitize as Perseus.

My depiction of him here is probably toward the end of his wanderings, maybe even right before unleashing his bow on the suitors. Since he is supposed to be dressed in beggar's rags his costume took very little research; it's just layers of cloth used as a cloak worn over a tunic. The only little addition I made is an ivory pin in the shape of an owl's face to show Athena's favor.

Athena, on the other hand, was a bit more challenging in pose and costume. I have mentioned before I try to abstain from direct depictions of the gods, but in this piece I wanted her influence on Odysseus to be palpable. The hardest part was making her armor as a war-god. Bronze age panoplies have been discovered and they seem to have been the pinnacle of protection, but I personally loathe the look of them so I decided to go with some Mycenaean vase-painting inspired armor. Although I usually think Athena's theme color would be green to reference her connection to olives, with this one I wanted her to be blindingly gray and white and terrifying.

It is a relatively modern concept to really depict the gods as evil, especially between Athena and Odysseus, but I kind of wanted to suggest that with her pose but still leave it ambiguous. Is the hand on his neck a tender caress, or a promise of a choke? Is she guiding his aim with a gentle touch, or is she forcing him to knock the bow and unleash the bloodshed?

#classicstober#classicstober2023#classicstober23#odysseus#the odyssey#athena#ancient greek mythology#mycenaean#linear b#tagamemnon#greek mythology#greek myths

176 notes

·

View notes

Photo

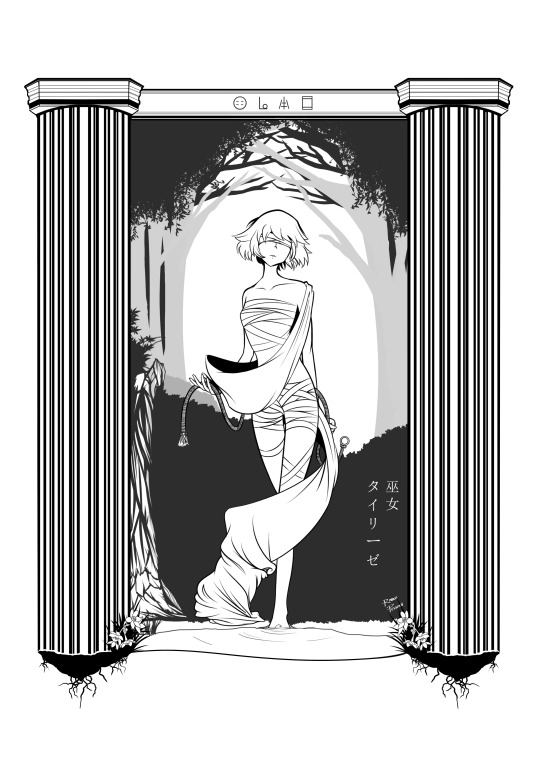

Teiresias, the blind seer, wading into Tilphussa’s waters to their death. The style is a combination of Japanese animation/manga and Byzantine iconography. The Linear B (ancient Greek) at the top reads: qe-ra-si-ja, which may be an early iteration of what would eventually become “Teiresias.”

#digital art#illustration#イラスト#rkgk#anime#greek mythology#greece#Hellenism#Teiresias#lgbtq#lgbtq art#Linear B#ancient greek#seer#Erinys and the Seer#Erinys to Miko#daffodils#narcissus#Mycenaean#エリニスと巫女#manga#mangaka

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway:

- Organic residue analysis of pottery from the dye workshop at Alatsomouri-Pefka, Crete

suck on it, tyre.

AND:

KN X 976 from LMIIIA2 (prior to 1300bce); should be read as: “This

many royal specialists are located at the purple workshop at da-*83-ja.”

#also thomas palaima's porphureion & kalkhion & minoan-mycenaean purple dye manufacture & use#if anyone's got my back it's always thomas palaima with his linear a/b readings#tyrian purple#TYRIAN purple my ASS i just found an article from 1966 talking about how the origin of the dye was in crete

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hymn to Agni (Stanzas 1-9 of the Rig Veda)

I praise Agni, the domestic priest,

the divine officiating priest of sacrifices,

the invoker, the best bestower of treasure.

Agni, to be praised by past

and present seers,

may he bring the gods here.

Through Agni, one may thus obtain wealth

and prosperity day by day,

glorious and most abounding in heroes.

O Agni, that worship and sacrifice,

which you encompass on all sides,

let that same go to the gods.

May Agni, the invoker, with the mental power of a seer,

the true, of the most brilliant fame,

come as a god with the gods.

Just as that good, which you,

Agni, do for the worshipper,

that of you is true, O Angiras.

To you, O Agni, day by day,

illuminator of the gloom, with a thought,

we come bringing praise;

ruling over sacrifices,

shining protector of order,

growing in your own house.

So, be easy of access to us,

O Agni, like a father to a son;

Follow us for our wellbeing.

#abby's translations#yes this is once again exam revision#but look its not greek this time lol#it is in fact vedic sanskrit#i will be hitting you guys with some linear b (mycenaean greek) translations next week though#don't worry about missing out on the many greek translations that i did last year

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the burnt city#punchdrunk#linear b#Mycenaean greek#catch me in Athens and/or Australia banging down some poor scholar's door BUT WHAT DOES KATORO MEAN#it's everywhere in the graffiti#it has to mean something#but also there's countless bits of graffiti everywhere, far too many to ever record and decipher#one of the great heartbreaking beautiful mysteries

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

i like to think that the ancient greeks made a lot of jokes about shipping cheese from tyre

#totally different etymologies but they are spelled the same in greek#τυρός cheese is from PIE and attested in linear b mycenaean greek#Τύρος tyre is semitic צור rock#mine

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The clearest evidence about the Mycenaean pantheon lies in the Linear B texts. As discussed above, only a handful of the deity names in these texts appear both on the mainland and on Crete. We might consider those deities mentioned only on Crete as being Minoan. For those deities mentioned on the mainland, we have at least two possibilities. On the one hand, they may be Greek, meaning that they may derive from the Indo-European civilization that gave rise to the Greek language. Some divine names do have Indo-European etymologies and cognates. On the other hand, they may be pre-Greek, belonging to the indigenous population of Greece before the Greek-speakers arrived. These deities may then have been adopted into the Greek pantheon. Some gods do have a blatantly Indo-European heritage, such as Zeus and Poseidon. Others are more difficult to determine. The deities attested to among the Mycenaeans are Zeus, Poseidon, Ares, Dionê, Marineus, Hera, Artemis, Hermes, Dionysos, Posideia, Trisheros, Manasa, Pereswa, Dopota, Dipsioi, Drimios, Iphemedeia, the Mother of Animals, the Queens, the King, the Lady of Upojo, the Lady of Asiwia, the Lady of Iqeja, the Lady of Newopeo, and the Lady of Grain, as well as simply Lady (Potnia) (Hägg 1997, 165).

Much can be learned from these names not only about Mycenaean religion, but also about continuity of Greek religion into the historical periods. Many deities remained in power throughout Greek history, such as Hera and Hermes, showing that the Greek Dark Age was hardly the utter devastation and re-creation of Greece that scholars originally believed it was. Other names in the corpus either ceased to exist after the Bronze Age or morphed into nondivine titles, such as Dipsioi, “the Thirsty,” possibly referring to the dead. The most vexing of these is the name/title Potnia. By Homer’s day, the term meant “revered female,” referring either to a mortal or to a goddess. Sometimes the title was specific, as with the Potnia Therôn—Mistress of Animals—used in reference to Artemis. The question of who the Bronze Age Potnia was/were, however, is problematic.

The name/title Potnia appears twelve times at Pylos, five or six times at Knossos, three times at Mycenae, and once at Thebes (Boëlle 2001, 403). Thus, it is common to both Greece and Crete. In some instances, the word appears alone; in others, it is modified by a concept or place-name. At Knossos we have the a-ta-na-po-ti-ni-ja, which translates to something like Lady of Athens, and the da-pu-ri-to-jo-po-ti-ni-ja, or Lady of the Labyrinth. At Pylos we have a po-ti-ni-ja-a-si-wi-ja, Lady of Asia; po-ti-ni-ja-i-qe-ja, Lady of Horses; and at Mycenae there is the si-to-po-ti-ni-ja, or Grain Lady (Trümpy 2001, 411–413). The question is: Is Potnia one goddess or many? Is Potnia similar to the Christian “Our Lady,” in the way that Our Lady of Lourdes is also Our Lady of Fatima? Or is Potnia a title applicable to several separate goddesses at once? In both linguistics and occurrence, Potnia is related to the god Poseidon. The Pot- portion of her title may derive from the Indo-European word for possession or ownership, just as Poseidon means “Lord of the Land.” Her strongest cult is attested to at Pylos, where Poseidon was clearly the chief god, and she even has the title of i-qe-ja, relating her to horses, just like Poseidon. One could argue that Potnia was the consort of Poseidon. Furthermore, we know from later Greek mythology that Poseidon once mated with Demeter, both of them in the form of horses. If we add this to our study, and combine it with the fact that at Mycenae there was mentioned a Grain Lady (possibly an epithet for Demeter), we might say that Potnia was one universally acknowledged Aegean goddess, understood to be a grain/horse deity, consort of Poseidon, and later manifesting as Demeter. But then how do we understand titles like a-ta-na-po-ti-ni-ja, “Lady of Athens,” which is certainly a title of an Athena-like goddess? How could an apparently Indo-European word like Potnia be identified with a blatantly Minoan term like labyrinth? Why does the name/title Potnia appear more than once on some Linear B tablets? Should we understand that Potnia, as one goddess, received different dedications in her different guises, or that the different Potnias referred to distinct goddesses? In the end, it seems probable that Potnia was a title given to various goddesses in the Aegean pantheons. In some instances, such as at Pylos, one goddess was so prominent that she could be referred to merely by the title Lady. At other times, adjectives were used to differentiate among goddesses.”

- The Ancient Greeks: New Perspectives, by Stephanie Lynn Budin

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Kober and Michael Ventris, the ancient Greek script Linear B

As a script, Linear B contains eighty-seven syllabic signs, or symbols that represent sounds, and over a hundred ideographic signs, or symbols that represent objects, units of measurement, or commodities. These ideographic signs, also referred to as “signifying signs” do not correlate to a phonetic sound but to a word describing an object.

It seems that Linear B was used only in administrative contexts—not for literature or other endeavors.

*

The contributions of Alice Kober, a Hungarian-American classicist from New York, made Ventris’ astounding accomplishment possible.

Kober, who was born in New York in 1906, was always an exceptional student. She attended Hunter College after receiving a scholarship in 1924 and began learning Latin and Ancient Greek there.

After graduating from Hunter College, Kober received her master’s degree and later PHD in Classics from Columbia University.

*

Born into a military family in 1922, he spent much of his youth studying languages and was fascinated with deciphering codes from a young age.

The scholar’s family moved to Switzerland when he was just a child, and it was there that his passion for learning languages began. The child learned French and German at an unbelievable pace and soon became fluent in Swiss German as well.

After eight years in Switzerland, Ventris and his family returned to England, and his parents divorced four years later in 1935. The teenager received a scholarship from the Stowe School, where he began studying Ancient Greek and Latin.

#ancient greek#mycenaean#history#archeology#linear b#language#language deciphering#discovery#historians#writing script

0 notes

Text

Thinking bout how Diana Prince probably writes in Linear B

#wonder woman#diana prince#diana princess of themyscira#dc comics#linear b#like literally#she was born in Mycenaean Greece

1 note

·

View note

Text

Classicstober Day 18: Phaedra (𐀙𐀂𐀉𐀨)

Phaedra was Ariadne's sister and married Theseus to become Queen of Athens (that must have been a WILD Christmas dinner). Things were good until Theseus' son by the Amazon queen dropped by for a visit. His name was Hippolytus (𐀂𐀢𐀬𐀵)…

Phaedra's story isn't quite as well known as many others in greek mythology, outside of a few tragedies and operas. The nature of the beast for most of these stories is that there are a couple of versions and no one can say which one is the 'real' one, but Phaedra's story, depending on the version you go by, can have wildly different vibes.

As I mentioned, she was Ariadne's sister. In some versions, when Ariadne helped Theseus defeat the Minotaur and escape, Phaedra was with her and part of Theseus' crew when he decided to abandon Ariadne on Naxos, eventually becoming his wife in Athens. In others, Phaedra is ignorant of the role Ariadne played in Theseus' victory and is instead sent to Athens to marry him for a political alliance. The implications of both versions are fascinating from a story-telling perspective. If Phaedra left with Theseus, just how complicit was she in leaving Ariadne behind? If their marriage was purely political, what did she think of the man who had just abandoned her sister? In the end, though, the important part (story wise) is that she marries Theseus and becomes Queen of Athens.

I depicted Phaedra here in her full queenly raiment. Yes, Athens was a purely Mycenaean settlement at this time, but the Mycenaean woman's fashion borrowed LOTS from the Minoan and considering where Phaedra was born she deserved a more Minoan look. That's why she has that quilted-looking over-garment on her dress. I made her palette green to represent her role as queen of Athens, and since Athena is the goddess of olive trees it made sense to me to lean into it. She is also blonde and amber-eyed to show her connection to Helios through her mother, Pasiphaë.

The architecture here is based on Minoan buildings. I imagine that inside the Cyclopean walls of Mycenaean Athens they could afford to make things more royal and less military-pragmatism. Athens is known for being a center of intellectualism in the ancient world (an image they painted themselves with), but even though this scene is set many centuries before the height of Classical Athens' power I decided to lean into that here too.

As for Hippolytus… the sources we have for the ancient Amazons are vanishingly rare. Most scholarship has focused on the Phrygians during the Classical Period, and I was able to find precious little reference for the Bronze Age Phrygians that might represent the historical Amazons. I did find one reconstructed garment, and even though it was very plain (and probably mean for a woman) I decided to put Hippolytus in it anyway. The Amazons were practical warriors, so I doubt that, as a child, Hippolytus would have had any other clothes than what his mother had. I also decided that he should be tall, taller than Theseus, as the Amazons were said to stand taller than normal men.

I could go into more details on the very disastrous story between Hippolytus, Phaedra, and Theseus, but I think it falls outside the purview of this piece. It is a fascinating, compelling story, though, so if you have made it this far into my ramble then I recommend checking it out.

#classicstober#classicstober23#classicstober2023#phaedra#hippolytus#greek mythology#ancient greek mythology#greek myth art#mycenaean#linear b#tagamemnon#amazons

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asivia: The Marriage Hunter, Former Party Member

(This is an excerpt from my essay, Real World Cultural and Linguistic References in Delicious in Dungeon)

ASIVIA

(Japanese Pronunciation: Ashibia)

Asivia (アシビア) is a female magic user that was in the Touden party before Marcille. She’s a pretty woman who tries to take advantage of Laios’ trusting nature, and is referred to at one point as a “marriage-seeker”, implying that she is a gold-digger, looking to find a man who has recently struck it rich in the dungeon and marry them now that they have money. Laios seems oblivious to the fact that she’s using him. When Laios, under pressure from the rest of the party, tells Asivia that he can no longer give her special treatment, she immediately leaves.

Asivia is a name that comes from the precursor to Ancient Greek, Linear B. Linear B is a syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest known form of the Greek language.

Asivia (𐀀𐀯𐀹𐀊/Ασίfια/a-si-wi-ja) is identified as an “ethnic name” on a chart I found online about names and words in Linear B, but it doesn’t specify what ethnicity. It most likely comes from the Hittite word Assuwa (𒀸𒋗𒉿, aš-šu-wa).

I found that asivia/asiwija was a word used to refer to a portion of northwestern Anatolia called Lydia. Later this word came to mean the world east of Greece in general, and eventually evolved into the English word Asia, so Asivia means a person from Lydia/east of Greece/Asia.

Lydia was an Iron Age kingdom located in modern day Turkey, and the name comes from Ancient Greek Λυδία (Ludía, “the region of Lydia”), from λυδία (ludía, “beautiful one, noble one”). The given name Lydia originally indicated ancestry or residence in the region of Lydia.

So Asivia’s name may be telling us where she’s from. In Dungeon Meshi’s case, it could mean she is from “Asia” meaning the Eastern Archipelago, or it could mean she is from the “East”, as in the Eastern Continent, where the story takes place. Since she looks like she has brown or red hair, I think she’s probably from the Eastern Continent. Her name could also be a joke about how she’s a pretty girl and Asivia means someone from Lydia, since Lydia/Ludia means “beautiful one” in Greek.

MISTRESS OF THE DUNGEON

Asivia/Asiwija also has a connection to the Ancient Greek word potina (𐀡𐀴𐀛𐀊/πότνια/po-ti-ni-ja), which means "Mistress, Lady", and is an honorific title used both for mortal women and goddesses. In the case of goddesses, it’s a euphemism used in place of their actual names, and Asivia/Asiwija is one of the descriptive words that has been found frequently accompanying potina. “Potina Asivia” means “Mistress/Goddess from the East.”

Despoina, another euphemistic title used the same way, means mistress of the house, and a famous use is a mysterious, nameless, "Mistress of the labyrinth", who was worshiped in Minoan Crete, the place where the Minotaur was supposedly imprisoned. The tale of the Minotaur and the labyrinth has deep connections to the world and plot of Dungeon Meshi, which I go into more in Chapter 12 (Elven Culture).

Asivia was not Laios’ mistress, obviously, but she wanted to be! And if she hadn’t left, and had become Laios’ lover, then maybe she would have been called the Mistress of the Dungeon (labyrinth) at the end of the story…

#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#dunmeshi#spoilers#laios touden#dungeon meshi research#dungeon meshi spoilers#The Essay

270 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hermes

Hermes was the ancient Greek god of trade, wealth, luck, fertility, animal husbandry, sleep, language, thieves, and travel. One of the cleverest and most mischievous of the 12 Olympian gods, Hermes was their herald and messenger. In that position, he came to symbolise the crossing of boundaries in his role as a guide between the two realms of gods and humanity.

Hermes was known for his impish behaviour and curiosity. He invented the lyre, the alphabet, and dice. The latter explains why the god was beloved by gamblers. Hermes was the patron of shepherds and invented the panpipes they used to call their flock. To the Romans, the god was known as Mercury.

Origins & Family

Hermes has a very long history, being mentioned in the Linear B tablets of the Mycenaean civilization, at its height from the 15th to 13th century BCE. Such tablets have been discovered at Pylos, Thebes, and Knossos. With origins, then, as an Arcadian fertility god who had a special love for the Peloponnese, the ancient Greeks believed Hermes was the son of Zeus and the nymph Maia (daughter of the Titan Atlas) and that he was born on Mt. Cyllene in Arcadia. In mythology, Hermes was also the father of the pastoral god Pan and Eudoros (with Polymele), one of the leaders of the Myrmidons, although the god was not given a wife in any Greek myth. The idea that Hermes represented movement is reflected in his role as the leader of both the Nymphs and Graces (Charites).

Continue reading...

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Mycenaean women put their own spindles to splendid use, producing luscious cloaks and long, richly patterned or striped skirts. Far from resigning themselves to the weaving rooms, they travelled in chariots, performed songs or poetry to the accompaniment of lyres, and carried wheatsheaves for public ceremonies and rituals, as vibrantly coloured frescoes from the palace at Mycenae reveal. In one of the most enigmatic paintings, one woman holds a sword, another a spear, while two tiny men, one painted red and the other black, float mysteriously between them, like toy models or thought bubbles. Through their contact with the divine, perhaps, the women pictured gain agency over the men’s fate. Hera, Zeus, Poseidon and a female birth and death goddess known as Potnia were among the deities the Mycenaeans are known to have worshipped. While Mycenaean women clearly played an important role in religion, their political position within the palaces was weaker than that of their Minoan counterparts, and secondary to the men’s. Each Mycenaean palace complex was presided over by a male ‘wa-na-ka’ or wanax.

Surviving clay writing tablets provide just as fascinating an insight into the lives of women in the real palaces of the Mycenaean era. The fullest collection of tablets comes from a pair of rooms in the palace complex of Pylos, but Knossos, the former Minoan capital, was also a key repository. A total of 4,476 tablets have been preserved across the two sites. Among these there are references to more than 2,000 different women. Unlike Linear A, the Minoans’ writing system, the Mycenaeans’ similarly syllabic Linear B has been successfully deciphered. Working (as opposed to non-working elite) women were denoted by signs resembling an abstract impression of the female form. ‘Woman’ was conveyed by two dots for breasts, legs joined to suggest a long skirt of the kind Mycenaean women wore, and a curved line where her head would be, suggestive of long or dressed hair (in the sign for a man, by contrast, there is a straight line for the head).

The women referred to in the tablets were employed in a wide range of jobs, many of them familiar from the Homeric epics. In the Odyssey, women grind wheat and barley, ‘the marrow of men’, at mills. There were ‘flour-grinders’ at the palace in Pylos. In both epics, women weave, whether royal or servile. Andromache works in the Trojan palace with a loom and distaff while ordering her servant women about their work. Helen embroiders a purple cloth with scenes from the Trojan War as if she were telling the story of the poem herself. And as we have seen, Penelope weaves and unweaves a funeral shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes. The women who wove at Pylos and Knossos were no less versatile in their handiwork. They managed something like a textile industry, producing goods for export as well as the palace community, and worked in groups according to specialism. There were wool-spinners and carders, linen- and leather-workers, finishers and headband-makers for horses. These women usually worked separately from men, but at Pylos there is evidence that at least two women, Wordieia and Amphehia, formed part of a mixed leather-making group.

Working groups were the modus operandi at the Mycenaean palaces. Women were usually accompanied by boys and girls, presumably their own children, as they went about their tasks. Many were divided also according to their geographical region. Pylos was split into sixteen districts over two provinces, Nearer and Further, separated by Mount Aigaleo. The palace-workers came from more than 200 named places, some of which may have been local streets, while others, including Lemnos, Miletus and Knidos, lay further afield. It is possible that, like the Sidonian (Phoenician) women carried to Troy by Paris in the Iliad to weave fine robes for the court, some of the women working in the Mycenaean palaces had been enslaved.

Although the women were engaged in hard, practical labour, their work was recognised as highly skilled, and the Mycenaeans took some pride in it. Men were sometimes described on tablets as being the offspring of women of particular crafts, for example, ‘sons of flax-workers’. Female workers were allocated the same amount of food in the regular distributions as their male counterparts, and twice as much as their children, whereas in Babylonia, men typically received three times the female ration.

A mysterious senior class of priestess at Pylos known as ‘keybearers’ (did they open and close shrines within the palace complex?) even owned land. A landowning keybearer named ka-pa-ti-ja (‘Karpathia’) was wealthy enough to donate almost 200 litres of grain to the palace, probably for a religious festival. Given the historical prominence of women at the court of Pylos, it is fitting that a mythical Pylian king should intervene in the dispute over Briseis in the Iliad. Old Nestor urges Agamemnon to return the woman to Achilles and to end their feud."

The Missing Thread: A Women's History of the Ancient World, Daisy Dunn

#history#women in history#women's history#historyedit#mycenaean greece#ancient greece#bronze age#ancient world#working women#women's work#greece#greek history

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I might have written about this before but: to people who are weirded out Modern Greeks call Zeus Δίας (Dias).

The original name of Zeus, first attested in Mycenaean Greek Linear B scripts (1400-1200 BC), was di-we, di-wo, from the possible Proto-Hellenic form *dzeus, from possible PIE root being *dewos, meaning "god". That d-strong form in Mycenaean was later retained better in the secondary forms of the noun, meaning the cases apart from the nominative.

Nominative: ὁ Ζεύς (o Zeus)

Genitive: τοῦ Διός (tou Dios)

Dative: τῷ Διῐ́ (to Dii)

Accusative: τὸν Δίᾰ (ton Dia)

Vocative: ὦ! Ζεῦ (oh Zeu)

The theorized z-including form *dzeus in Proto-hellenic survived better in some Greek dialects but even less so in others:

Δάν (Dán) — Aeolic

Δεύς (Deús) — Boeotian

Ζάς (Zás) — Laconian

Ζάν (Zán), Ζάς (Zás) — Doric

Ζήν (Zḗn) — poetic

Θιός (Thiós), Σιός (Siós) — Boeotian, Ionic

Τάν (Tán) — Cretan

As for Modern Greek, it has more often retained words through their secondary rather than their nominative cases, with the accusative case being the most common, like here.

#greek#greek language#ancient greek#modern greek#myceanean greek#languages#language stuff#linguistics#langblr#language learning#greek facts

182 notes

·

View notes