#new york tribune

Text

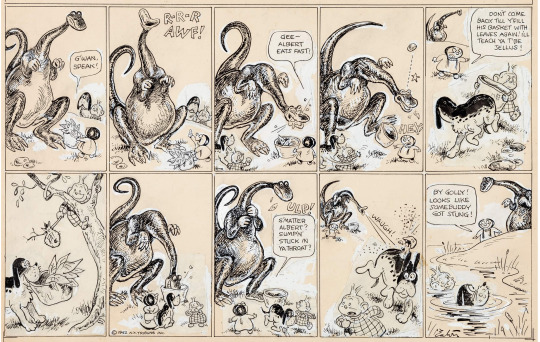

Original Peter Piltdown Sunday strip by Mal Eaton, published in the New York Tribune, 1942.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

𝗔𝘆𝘂𝗻𝘁𝗮𝗺𝗶𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝗱𝗲 𝗡𝘂𝗲𝘃𝗮 𝗬𝗼𝗿𝗸 𝗷𝘂𝗻𝘁𝗼 𝗮 𝗹𝗮 𝗡𝗲𝘄𝘀𝗽𝗮𝗽𝗲𝗿 𝗥𝗼𝘄 (𝗲𝗱𝗶𝗳𝗶𝗰𝗶𝗼𝘀 𝘀𝗲𝗱𝗲𝘀 𝗱𝗲 𝗡𝗲𝘄 𝗬𝗼𝗿𝗸 𝗪𝗼𝗿𝗹𝗱, 𝗡𝗲𝘄 𝗬𝗼𝗿𝗸 𝗧𝗿𝗶𝗯𝘂𝗻𝗲 𝘆 𝗡𝗲𝘄 𝗬𝗼𝗿𝗸 𝗧𝗶𝗺𝗲𝘀) 𝗲𝗻 𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗻𝗼 𝗮 𝟭𝟵𝟬𝟲

#historia#nueva york#manhattan#lugares#blanco y negro#siglo xx#1906#ayuntamiento#edificios#rascacielos#new york#history#city hall#newspaper row#new york world#new york tribune#new york times#20th century#black and white#xx century

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A BOUT DE SOUFFLE (1960)

#when i was in college i had a new york herald tribune sweater that was the pride of my life#i even had polly maggoo's shirt with her name on it#tell me you wrote your thesis on the women of the new wave without telling me#a bout de souffle#jean seberg#the french are glad to die for love#sixties sweethearts#*

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

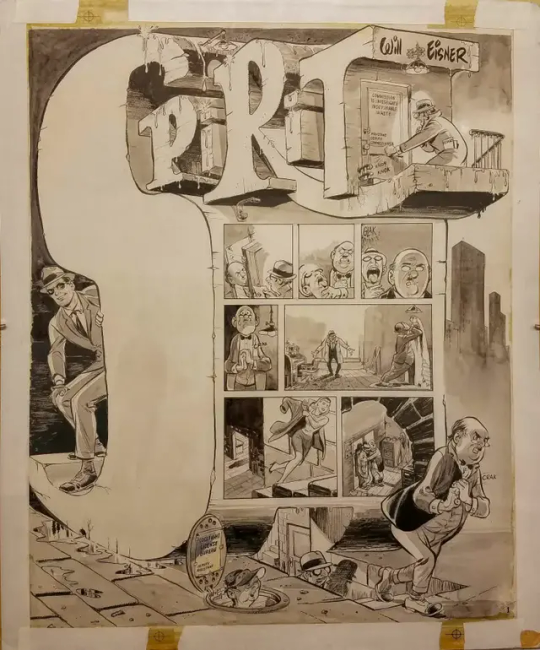

The Spirit

by Will Eisner and Chuck Kramer

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1901 on the new art is killing me cause all the theorists were guessing early 1870s for Annabel and Lenore so uh-

#nevermore webtoon#rip to all the people whose search history is all clothing from the 1800s trying to figure out what matched the best if its actually 1901-#damn#who knew barbie would cause this much of a crisis within me#like damn i know about rnf accidentally using the wrong logo for the new york tribune but wow#my world view feels shaken /j

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

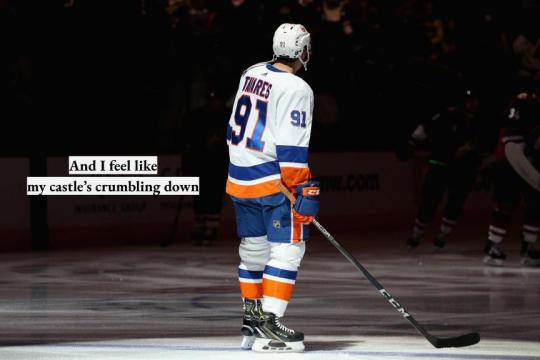

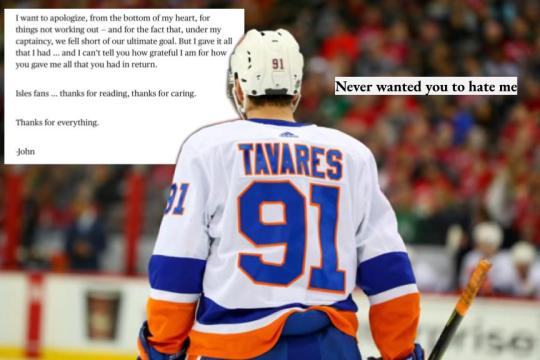

John Tavares x Castles Crumbling - Taylor Swift & Hayley Williams

#I saw a video edit of this on twitter a while ago but I do love my picture posts so I wanted to try it#I really love how the last panel turned out but also. GUT PUNCH when I read his players tribune thing#why am I posting this at fuckin 6:47am#John Tavares#New York Islanders#Toronto Maple Leafs#maple leafs#hockey#mine#hockey edit#taylor swift#hayley williams

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marguerite Higgins of the New York Herald Tribune receives the New York Newspaper Women's Club special citation as the outstanding woman reporter of the year, November 17, 1950. The citation commended Higgins for her reporting of the Korean conflict, for her courage under fire, and for her bravery in administering blood plasma to the wounded. Presenting it is Margaret Mara of the Brooklyn Eagle, president of the club, at the organization's Front Page Dinner Dance.

Photo: Marty Lederhandler for the AP

#vintage New York#1950s#Marty Lederhandler#Marguerite Higgins#women reporters#Nov. 17#journalism#NY Herald Tribune#newspapers#17 Nov.#female journalists#Korean War#female war correspondents#women in journalism

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m now in love w godard 💗

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wake up, read ,run errands

New York Herald Tribune!

كل عام وانتم بخير :)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Editor’s note: This story contains audio of people calling 911 during a mass shooting incident.

The first two 911 calls came in at 11:29 a.m.

A man had crashed his truck into a ditch by Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, and he was rushing toward the school with a gun.

“He’s inside the school shooting at the kids!” a third caller yelled at 11:33 a.m.

The gunman fired more than 100 rounds by the time police dispatchers received another call two minutes later. An adult voice could be heard making “shh” sounds for nearly 44 seconds before the phone abruptly cut out.

Monica Martinez, a STEM teacher who was hiding in a closet at the school, was among several callers from inside the school who followed.

“There’s somebody banging at my school,” Martinez said, her voice muffled as she continued speaking. “I’m so scared,” she said at 11:36 a.m.

What happened on May 24 in Uvalde is well documented. Hundreds of law enforcement officers from nearly two dozen local, state and federal agencies rushed to the scene. It took more than an hour before they entered the rooms where the gunman was located. They treated the crisis as one of a barricaded suspect who was no longer an active threat. Ultimately, 19 children and two teachers were killed in the worst school shooting in Texas history.

In the ensuing five months, the delayed law enforcement response has spurred state and federal investigations. The school district’s police chief was fired. He has publicly contested his termination, saying he was unfairly blamed. The acting Uvalde police chief has also been suspended and a state trooper fired. The chief of the Texas Rangers, the Department of Public Safety unit that is leading the state investigation, retired abruptly in September, as did his deputy in August. Several state police troopers remain under investigation. Officers facing punishment either could not immediately be reached for comment or declined to respond.

The Texas Tribune and ProPublica have for the first time obtained recordings of more than 20 emergency calls and dozens of hours of conversations between police and dispatchers that lay bare the increasing sense of urgency and desperation conveyed by children and teachers. In chilling, muffled 911 calls, they begged for help from inside the school.

Although the existence of some 911 calls and body camera footage has been reported publicly, the totality of the recordings show the pervasiveness of the miscommunication that unfolded that day.

During some calls, dispatchers and officers warned that class was supposed to be in session in rooms where the gunman had been shooting. On others, law enforcement officers said they were unaware that anyone aside from the gunman was in the classrooms, even as dispatchers received calls from children seeking help.

Ten-year-old Khloie Torres was one of those children. While state officials previously released a transcript with excerpts from one of Khloie’s phone calls, the news organizations obtained additional recordings of her pleading for help that had not been made public. Khloie survived that day.

In an interview, her father, Ruben Torres Jr., said he is “disgusted” that police did not quickly intervene. The fact that his daughter had to wait so long to get help is “mind-boggling,” Torres said.

“There was no control. That dude had control the entire 77 minutes,” said Torres, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran. “They didn’t have him barricaded. He had the police barricaded outside. It’s plain and simple. The police didn’t go in. That’s your job: to go in.”

DPS officials did not respond to questions from ProPublica and the Tribune about the recordings. A spokesperson for the city of Uvalde, the police chief, the Uvalde mayor and the county’s chief executive declined to comment.

Communication was a key failure throughout the response. Many officers assumed the school police chief, Pete Arredondo, was in command. He did not have his radios with him, issued few orders and later said he never viewed himself as the officer in charge. County officials said emergency communications were overwhelmed in the rural community, which typically has only two dispatchers answering 911 calls and juggling the transmission of key information to emergency responders.

The emergency radio system has two 911 lines and three emergency channels. Its frequency is designed for the vast, 15,000-square-mile stretch of scrubby desert terrain, rather than for high-density urban areas where equipment must work inside buildings, said Forrest Anderson, the county’s emergency management coordinator who oversaw the radio system’s implementation two decades ago. A legislative committee that later examined the response noted that city police radios worked only intermittently inside the school.

Radio traffic and footage obtained by the news organizations show that some police knew about the 911 calls, but just how many officers remains unclear.

High-stakes emergency responses always have some communications gaps, but skilled incident commanders should be prepared to overcome such challenges, said Bob Harrison, a former California police chief and homeland security researcher at the Rand Corp., a national think tank.

Harrison noted that many of the radios used by Border Patrol agents also did not work during the Uvalde shooting response, but the agency’s SWAT team, which does not typically lead the response in school shootings because it is a federal agency focused on immigration and national security, mobilized to breach the classroom once it arrived and determined no one was in control.

“If a strong unifying command scene was set up quickly, these discrepancies wouldn’t have been necessarily relevant, and there would have been one voice and one command,” Harrison said of the problems with 911 and radio communication.

The state legislative committee reached a similar conclusion in its July investigative report, which stated that a capable incident commander would have realized that the radios were “mostly ineffective” and that responders needed other means of communication to transmit key details such as calls from victims inside the classrooms. The report highlighted that law enforcement is trained to be “prepared to respond effectively without reliable radio communications” and could employ a series of strategies including using “runners” to deliver messages in person.

But that day, children and teachers, including Martinez, waited to be rescued.

In the dark closet of room 116, Martinez stayed on the phone with a dispatcher and tried to practice a key tenet of the school’s active-shooter protocol: Be quiet.

CLASS SHOULD BE IN SESSION

When a new round of gunshots rang out from behind the closed door of the two adjoining classrooms, Uvalde police Sgt. Daniel Coronado sprinted outside, panting heavily as he relayed an urgent message on his radio to city police dispatchers.

“He’s inside the building,” Coronado said of the shooter at 11:38 a.m. “We have him contained.”

He asked for ballistic shields and requested that someone call DPS.

Then he repeated: “He’s contained. We’ve got multiple officers inside the building at this time. We believe he’s barricaded in one of the offices. Male subject is still shooting.”

Four minutes later, a male voice, unclear from which agency, asked that someone check the classroom of fourth-grade teacher Eva Mireles, a 44-year-old educator and the wife of Ruben Ruiz, a Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District police officer. Mireles was assigned to classroom 112, one of two adjoining rooms where the shots were coming from.

“See if the class is in there right now or if they’re somewhere else,” the official said.

Then a Uvalde school district police officer came on the radio with a critical announcement: “The classroom should be in session right now. The class should be in session, Ms. Mireles.”

Another officer gasped.

“That’s going to be Ruben’s girl,” he said, referring to Mireles.

“Oh no, oh no,” Coronado muttered under his breath.

The exchange demonstrates some officers knew early on that the gunman was not barricaded alone in the classroom. More indicators, and clear confirmations, would come soon after — yet for much of the response, they would not be heard.

At 11:48 a.m., Ruiz, who was standing in the hallway outside of the classroom, told officers that his wife had been shot. Ruiz said his wife had called him and said she was “dying.” Mireles later died in an ambulance.

Officers escorted Ruiz outside, taking away his weapon for his safety, according to interviews officers at the scene later gave to the Texas Rangers. But they did not attempt to enter the classroom. One of the police lieutenants who heard Ruiz’s announcement told investigators that they were waiting for DPS and Border Patrol to arrive “with better equipment like rifle-rated shields.”

By that time, Martinez, the teacher, had been on the phone with 911 for more than 10 minutes. She had told the dispatcher that she could hear people in the hallway. The dispatcher urged her to stay quiet and remain barricaded in the closet.

“You still there with me?” the dispatcher asked at about 11:47 a.m.

“I’m still here,” Martinez whispered.

Misinformation spread as Martinez and other 911 callers waited to be rescued. At 11:50 a.m., a Uvalde school district police officer wrongly reported that the school chief was “in the room with the shooter,” referring to Arredondo by his call sign.

Seven minutes later, an officer asked if any children were inside with the gunman.

“No, we don’t know anything about that,” another officer replied on the radio.

“Everything is closed, like the kids are not in there,” a third responded.

About a minute later, an officer asked for the shooter’s location.

“The school chief of police is in there with him,” another officer replied.

As the back-and-forth continued, law enforcement officers rescued people from other classrooms. At 11:58 a.m., Martinez told the dispatcher that she again heard someone knocking. She said the person had identified themselves as a police officer.

“Open the door,” the dispatcher said, confirming that the person on the other side was law enforcement. “Stay on the line with me until you make contact with him.”

“I’m coming,” the teacher whispered.

Her sobs carried through the phone.

The teacher did not return calls and emails seeking comment.

CONFUSION MARKS RESPONSE

Some children in classrooms 111 and 112 with the gunman kept calling 911, seeking help even when they suspected it was not safe to speak. One of the first calls from a trapped student, at 12:03 p.m., was barely audible.

“There’s a school …” a muffled child’s voice reported, breaking up in the recording, “at Robb Elementary.”

The call lasted a minute and 24 seconds. The child was silent as the dispatcher asked their name and what room they were in.

“Hello, ma’am? Can you hear me?” the dispatcher asked.

Then at 12:10 p.m., Khloie called.

“There is a lot of bodies,” The New York Times previously reported that she told a dispatcher, adding that her teacher had been shot but was still alive.

Khloie stayed on the phone for more than 17 minutes. While she spoke, another city police dispatcher answered a call from DPS and erroneously reported that the school police chief was inside the classroom with the gunman.

“I have the school chief of the PD in room 111 or 112 with the active shooter, and they’re still standing by,” she said when the DPS dispatcher asked for an update. “We have multiple agencies on scene. I don’t know if you have anybody else to send out to help out?”

“We’re sending everybody that we can, um, heading out there, but do you have any injuries, fatals, anything?” the DPS dispatcher responded.

Only one female was shot, and perhaps an officer was injured, the Uvalde dispatcher replied.

A dispatcher’s voice crackled through the Uvalde police and Border Patrol radio traffic, notifying that she had a child on the line.

“The child is advising he is in the room full of victims, full of victims at this moment,” the dispatcher said.

Hallway surveillance video from inside the school at the time shows at least four law enforcement officials, one with a shield, kneeling outside the classroom door with their guns drawn.

It is not clear if the officers heard that message.

At 12:14 p.m., a state trooper’s body camera captured someone saying, “There’s victims in there, dude.” The trooper was standing outside a door to the school, with at least eight officers from different agencies visible from that camera angle.

“We need to get in there,” one responded.

No one did.

Five minutes later, another girl in room 111 called 911. The recording of the call, which lasted a minute and 17 seconds, is mostly inaudible.

In the hallway, Uvalde County Constable Emmanuel Zamora wrongly suggested that the gunman may have already shot himself.

“One shot at the end was self-inflicted, maybe,” Zamora said in the recording, referring to an earlier burst of gunfire.

Zamora did not respond to texts and emails about his comments, which had not been previously reported.

Arredondo, the school chief, can be heard on a state trooper’s body camera at 12:20 p.m. telling another officer: “We have victims in there. I don’t want to have any more. You know what I’m saying?”

It was the first time he acknowledged to other responders that anyone was wounded inside the two classrooms, according to new footage obtained by the news organizations. The legislative report noted only that he acknowledged “some casualties” 14 minutes later. Arredondo did not return a message seeking comment shared with him by his former attorney.

A minute later, the gunman fired again.

Officers in the hallway flinched, formed a line and started walking down the hall, then suddenly stopped, a state trooper’s body camera footage reveals.

Just after the shots were fired at 12:21 p.m., the school chief began trying to talk to the shooter for the first time, according to communications and records.

“If you can hear me, sir, please put your firearm down, sir,” Arredondo said. “We don’t want anyone else hurt.”

Just after 12:30 p.m., three troopers again advanced toward the classrooms before an unidentified person said “no, no, no,” according to body camera footage.

Once again, they stopped.

A DPS trooper who made his way into the hallway around that time asked another officer if there were children in the classroom. The response was, “We don’t know.”

By then, more than 20 minutes had lapsed since Khloie first begged a dispatcher for help. She ended the initial call when she feared the gunman, who she felt taunted the children, was getting close, her father later recalled.

She called 911 again at 12:36 p.m.

“There’s a school shooting,” Khloie said. “Yes, I’m aware,” the dispatcher responded. “I was talking to you earlier. You’re still there in your room? You’re still in room 112?” “Yeah,” Khloie replied. “OK. You stay on the line with me. Do not disconnect,” the dispatcher said.

“Can you tell the police to come to my room?” Khloie whispered. The dispatcher said: “I’ve already told them to go to the room. We’re trying to get someone to you.”

About two minutes later, Khloie once more asked for police.

Yet again, a dispatcher tried to reassure her.

“I have someone that is trying to get to you, OK,” she said.

Khloie whispered that she thought she heard the police next door.

“If you hear anyone come in, but they’re not supposed to be there, and they don’t say that they’re police, y’all pretend that you are asleep, OK?” the dispatcher replied.

“THAT WAS YOU?”

As the Border Patrol strike team was almost ready to breach, DPS Capt. Joel Betancourt went on the radio and ordered the agents to wait.

“The team that’s gonna breach needs to stand by,” Betancourt said at 12:50 p.m.

The captain did not respond to requests for comment left for him through DPS.

The team ignored the order and entered the classroom, quickly killing the shooter. The previously silent hallway filled with officers waiting to act.

Someone yelled, “Make a hole!” as police carried out wounded children. Law enforcement officers motioned for those who were not as severely injured to walk out on their own.

“Oh man, I guess there was more kids in that room,” a DPS special agent said, according to his body camera footage. “Yeah, he must have had some hostages,” another law enforcement officer replied.

As the onsite paramedics focused on the most critically injured, officers began taking other hurt children to the hospital. Khloie was among them.

“I was on the phone with a police officer,” she told the trooper examining her as the screams of other wounded children reverberated in the background.

The officer, whose body camera had earlier picked up a dispatcher describing that call, seemed surprised.

“Oh, that was you?” the trooper asked.

#us politics#news#tw child death#tw school shooting#school shooting#uvalde shooting#robb elementary shooting#texas#the texas tribune#propublica#2022#texas department of public safety#texas rangers#us border patrol#salvador ramos#the new york times#mass shootings#mass shooters#gun violence#gun control#911 recordings#body cam

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Al Jaffee - Dessin original pour la série ''Tall Tales'' (New York Herald Tribune, 1959) - Source Heritage Auctions.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Indian Revolt

Karl Marx for the New-York Daily Tribune

[September 16, 1857, page 6]

London, Sept 4, 1857.

The outrages committed by the revolted Sepoys in India are indeed appalling, hideous, ineffable — such as one is prepared to meet – only in wars of insurrection, of nationalities, of races, and above all of religion; in one word, such as respectable England used to applaud when perpetrated by the Vendeans on the “Blues,” by the Spanish guerrillas on the infidel Frenchmen, by Servians on their German and Hungarian neighbors, by Croats on Viennese rebels, by Cavaignac’s Garde Mobile or Bonaparte’s Decembrists on the sons and daughters of proletarian France. However infamous the conduct of the Sepoys, it is only the reflex, in a concentrated form, of England’s own conduct in India, not only during the epoch of the foundation of her Eastern Empire, but even during the last ten years of a long-settled rule. To characterize that rule, it suffices to say that torture formed an organic institution of its financial policy. There is something in human history like retribution: and it is a rule of historical retribution that its instrument be forged not by the offended, but by the offender himself.

The first blow dealt to the French monarchy proceeded from the nobility, not from the peasants. The Indian revolt does not commence with the Ryots, tortured, dishonored and stripped naked by the British, but with the Sepoys, clad, fed, petted, fatted and pampered by them. To find parallels to the Sepoy atrocities, we need not, as some London papers pretend, fall back on the middle ages, not, even wander beyond the history of contemporary England. All we want is to study the first Chinese war, an event, so to say, of yesterday. The English soldiery then committed abominations for the mere fun of it; their passions being neither sanctified by religious fanaticism nor exacerbated by hatred against an overbearing and conquering race, nor provoked by the stern resistance of a heroic enemy. The violations of women, the spittings of children, the roastings of whole villages, were then mere wanton sports, not recorded by Mandarins, but by British officers themselves.

Even at the present catastrophe it would be an unmitigated mistake to suppose that all the cruelty is on the side of the Sepoys, and all the milk of human kindness flows on the side of the English. The letters of the British officers are redolent of malignity. An officer writing from Peshawur gives a description of the disarming of the 10th irregular cavalry for not charging the 55th native infantry when ordered to do so. He exults in the fact that they were not only disarmed, but stripped of their coats and boots, and after having received 12d. per man, were marched down to the river side, and there embarked in boats and sent down the Indus, where the writer is delighted to expect every mother’s son will have a chance of being drowned in the rapids. Another writer informs us that, some inhabitants of Peshawur having caused a night alarm by exploding little mines of gunpowder in honor of a wedding (a national custom), the persons concerned were tied up next morning, and “received such a flogging as they will not easily forget.” News arrived from Pindee that three native chiefs were plotting. Sir John Lawrence replied by a message ordering a spy to attend to the meeting. On the spy’s report, Sir John sent a second message, “Hang them.” The chiefs were hanged. An officer in the civil service, from Allahabad, writes: “We have power of life and death in our hands, and we assure you we spare not.” Another, from the same place: “Not a day passes but we string up front ten to fifteen of them (non-combatants).” One exulting officer writes: “Holmes is hanging them by the score, like a ‘brick.’” Another, in allusion to the summary hanging of a large body of the natives: “Then our fun commenced.” A third: “We hold court-martials on horseback, and every nigger we meet with we either string up or shoot.” From Benares we are informed that thirty Zemindars were hanged on the mere suspicion of sympathizing with their own countrymen, and whole villages were burned down on the same plea.

An officer from Benares, whose letter is printed in The London Times, says: “The European troops have become friends when opposed to natives.” And then it should not be forgotten that, while the cruelties of the English are related as acts of martial vigor, told simply, rapidly, without dwelling on disgusting details, the outrages of the natives, shocking as they are, are still deliberately exaggerated. For instance, the circumstantial account first appearing in The Times, and then going the round of the London press, of the atrocities perpetrated at Delhi and Meerut, from whom did it proceed? From a cowardly parson residing at Bangalore, Mysore, more than a thousand miles, as the bird flies, distant from the scene of action. Actual accounts of Delhi evince the imagination of an English parson to be capable of breeding greater horrors than even the wild fancy of a Hindoo mutineer. The cutting of noses, breasts, &c., in one word, the horrid mutilations committed by the Sepoys, are of course more revolting to European feeling than the throwing of red-hot shell on Canton dwellings by a Secretary of the Manchester Peace Society, or the roasting of Arabs pent up in a cave by a French Marshal, or the flaying alive of British soldiers by the cat-o’-nine-tails under drum-head court-martial, or any other of the philanthropical appliances used in British penitentiary colonies. Cruelty, like every other thing, has its fashion, changing according to time and place. Caesar, the accomplished scholar, candidly narrates how he ordered many thousand Gallic warriors to have their right hands cut off. Napoleon would have been ashamed to do this. He preferred dispatching his own French regiments, suspected of republicanism, to St. Domingo, there to die of the blacks and the plague.

The infamous mutilations committed by the Sepoys remind one of the practices of the Christian Byzantine Empire, or the prescriptions of Emperor Charles V’s criminal law, or the English punishments for high treason, as still recorded by Judge Blackstone. With Hindoos, whom their religion has made virtuosi in the art of self-torturing, these tortures inflicted on the enemies of their race and creed appear quite natural, and must appear still more so to the English, who, only some years since, still used to draw revenues from the Juggernaut festivals, protecting and assisting the bloody rites of a religion of cruelty.

The frantic roars of the “bloody old Times,” as Cobbett used to call it – its, playing the part of a furious character in one of Mozart’s operas, who indulges in most melodious strains in the idea of first hanging his enemy, then roasting him, then quartering him, then spitting him, and then flaying him alive — its tearing the passion of revenge to tatters and to rags – all this would appear but silly if under the pathos of tragedy there were not distinctly perceptible the tricks of comedy. The London Times overdoes its part, not only from panic. It supplies comedy with a subject even missed by Molière, the Tartuffe of Revenge. What it simply wants is to write up the funds and to screen the Government. As Delhi has not, like the walls of Jericho, fallen before mere puffs of wind, John Bull is to be steeped in cries for revenge up to his very ears, to make him forget that his Government is responsible for the mischief hatched and the colossal dimensions it has been allowed to assume.

#Karl Marx#1857#Sepoy#revolt#mutiny#uprising#colonialism#eurocentrism#India#British#New-York Tribune

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

JEAN SEBERG: nouvelle vague français "IT GIRL"

speaking of style; jean seberg made cinema fashion history in the 1960 movie "Breathless". she was le first gal to wear a t-shirt in such a popular movie... as they had previously been an clothing item pour men. Her and her Iconic NEW YORK HERALD TRIBUNE scene made hishtory. plus she just a cutie.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#world news#time magazine#people magazine#mad magazine#architectural digest#new york times#chicago tribune#the sentinel#elle magazine#sixteen journal#life magazine#national geographic#washington post#the new yorker#new york#sports illustrated#newsweek#scientific american#womans world#woman's day#advocate men#workout#fitness#gq style#gq magazine#the herald#american zionist#road and track#off road#cbc news

1 note

·

View note

Text

Decoding Investment Treaty Arbitration: Navigating Global Disputes under English Law

Investment Treaty Arbitration (ITA) stands as an indispensable mechanism, steering the resolution of intricate global disputes between states and foreign investors. At its core, ITA finds its roots in bilateral and multilateral investment treaties, forming the bedrock for this comprehensive exploration of the process from an English law perspective.

Lexlaw Solicitors and Advocates, well-versed…

View On WordPress

#Arbitral tribunal#Arbitration Agreement#Arbitrator Appointments#Challenges to arbitration award#English Arbitration Act 1996#Foreign investors#ICSID#Investment Treaties#ITA#ITA Awards#ITA Proceedings#ITA Process#Litigation#New York Convention#Public Policy#Treaty Obligations#UNCITRAL

0 notes

Text

As early as the end of October 1946 Philip Morrison indicated his anxiety about the situation during the annual forum on public affairs conducted by the New York Herald Tribune:

At the last Berkeley meeting of of the American Physical Society just half the delivered papers . . . were supported in the whole or in part by one of the services . . . some schools derive 90 per cent of their research support from Navy funds . . . the Navy contracts are catholic. They are written for all kinds of work . . . some of the apprehension that workers in science feel about this war-born inflation comes from their fear of its collapse. They fear these things: the backers – Army and Navy – will go along for a while. Results, in the shape of new and fearful weapons, will not justify the expenses and their own funds will begin to dwindle. The now amicable contracts will tighten up and the fine print will start to contain talk about results and specific weapon problems. And science itself will have been bought by war on the instalment plan.

The physicist knows the situation is a wrong and dangerous one. He is impelled to go along because he really needs the money. It is not only that the war has taught him how a well-supported effort can greatly increase his effectiveness, but also that his field is no longer encompassed by what is possible for small groups of men. There is a real need for large machines – the nuclear chain reactors and the many cyclo-, synchro- and beta-trons – to do the work of the future. He needs the support beyond the capabilities of the university. If the O.N.R. or the new Army equivalent, G6, comes with a nice contract, he would be more than human to refuse.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#40s#1940s#philip morrison#anxiety#forum#public affairs#new york#herald tribune#berkeley#american physical society#army#navy#military funding#university funding#physicists#money#nuclear reactor#cyclotron#synchrotron#betatron#military contract

0 notes