#octavian tullius

Text

You've heard about Cicero: The Roman Musical. Now get ready for Six-style musical about the wives of Mark Antony! (also featuring Curio)

Featuring but not limited to:

Antonia Minor's steamy duet with Dolabella

Fulvia's epic battle-cry rap number, including a verse based on Octavian's terrible poem

Octavia's heartfelt power ballad about desperately trying to keep the Octavian-Mark Antony alliance together while looking after all the children (while simultaneously refusing to allow other people to walk all over her)

Cleopatra singing about her political ambitions, comparing JC and Mark Antony, defending herself against her portrayal in Rome & in modern media

Also featuring a song/rap number based on Cicero's second philippic because it needs to be there!! Mark Antony climbing in through the roof, possibly in a stola, Curio and his dad is there ---

Some kind of ensemble song with the wives addressing the audience based on Shakespeare's Friends, Romans, countrymen speech

you see my vision, right?

Also yes, I'm aware there's six of them on the poster. One of them is Curio perhaps. Also, graphic design is my passion, can you tell?

#ancient rome#roman republic#roman empire#tagamemnon#history shitposting#history memes#mark antony#julius caesar#cleopatra#fulvia#dolabella#octavia#octavia the younger#octavian#augustus#six the musical#musical memes#marcus antonius#william shakespeare#cicero#marcus tullius cicero#curio#roman history#women's history#fadia#antonia minor

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey just went through your previous ask.

But honestly consider that if you are women in your early to mid 20s rank the ancient romans which of them would be least to most creepy on your journey.

Thank you for establishing that my theoretical life here is that of a woman of rank. So I'm my head the scenario is my litter or whatever I was traveling in has broken down and it's just me and the two slaves who were with me (real me would never have slaves obvs upper class Roman me pretty much would have to)

Octavian - one look at this man and my skins gonna break out. I'm baby faced IRL so his creepy ass would mistake 24yo me for 14 and he had a thing for underage girls so he's probably gonna try to take liberties. This isn't gonna end well for me I fear. Especially if I'm somebody's wife because if it's not teenage girls his next favorite amorous target is other guys' wives. 1/10 the only reason 1 is there is just in case I actually get to escape this scenario without him forcing himself on me.

Sulla - depends on if it's party boy Sulla or Sulla on a military mission. Either way I'm gonna either get basic courtesy but very brusque at best or at worst I'm getting r*ped and left on the side of the road, potentially without even the protection of my servants who he'd probably steal 3/10 if he's in a good mood my vehicle may get repaired but the prospects aren't great

Julius - Julius would follow the same route as Agrippa except if he found me attractive or thought my family was of strategic influence then he'd spend the whole time trying to seduce me. Which depending on how footloose and wild of a Roman lady I am here, I might do, especially if I think it will bring political advantage to my own family because that's all Romans care about. But if I turned him down emphatically enough he'd probably take it well enough and leave me in peace and then he might not be as considerate as Agrippa but he wouldn't be outright rude because he never knows when he might need favors from my fam. 7/10 on safe vibes.

Cicero - he'll be perfectly safe just very self important and remind me how indebted I am to him ever after this event. 7/10 I'll be safe, he won't be pervy, he'll just be annoying and pompous

Antony - he'd offer his assistance, invite me to the party he's having, invite me to travel with him, try to seduce me, but if rejected he'd take it just fine and give me a couple amphora of wine for the road 7/10 he might get handsy when he's drunk but other than that he's gonna be a gentleman about things

Brutus - he'd offer me what hospitality he could, even if this is Liberators Era Brutus and he's scant on supplies or something he'd still do his best to uphold the reputation of his family for hospitality. Definitely not creepy, dinner with him might turn morbid though so 8/10 simply because he might be a little too passive to stop the men under his command from behaving unseemly

Agrippa - would stop, offer his protection and assistance. He'd probably talk to me about his kids and treat me to a nice dinner and then if I wasn't headed the same direction as he was he'd send me on my way with a detachment for safety and protection or have his men repair my chariot or whatever I was traveling in. No creepy vibes whatsoever 9/10 on safe vibes

Aurelius - he would be very courteous and help me out and even restock my provisions and set me up with a whole new vehicle rather than even delaying me to wait for repairs 10/10 this man is not creepy in the least

Gnaeus Pompeius - Magnus is magnanimous as heck. He's also very traditional. He would treat me with respect and honor and be extremely courteous. If this is Pompeius the married man he wouldn't even think of flirting with me because he was notorious for his monogamy in marriage. If it's bachelor Pompeius he might be making observations on my suitability as a spouse but he's not gonna make any forward moves. He'd talk to my family about it afterwards if he was interested in marriage. 10/10 I'm gonna be safe and sound and if any of his men made inappropriate comments he'd be the most likely of the guys on this list to admonish them for it

#roman history#ancient rome#m t chickpea#marcus agrippa#marcus tullius cicero#Cicero#Agrippa#brutus#brutus and cassius#marcus aurelius#mark antony#marcus antonius#gnaeus pompeius magnus#gnaeus Pompeius#Pompey the Great#how often do you think about the roman empire#roman empire#ancient history#julius caesar#caesar#augustus#pompey#pompeius magnus#Octavian#sulla#lucius cornelius sulla#gaius julius caesar

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

My Mark Antony double drabble series is done! Self indulgent character study as befits the protagonist.

1: Antony & Brutus

2: Antony & Caesar

3: Antony & Cicero

4: Antony & Cassius

5: Antony & Octavian

6: Antony & Agrippa

7: Antony & Pompey

8: Antony & Rome

Chapters: 8/8

Fandom: Classical Greece and Rome History & Literature RPF, Julius Caesar - Shakespeare, Rome (TV 2005), Ancient History RPF

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Relationships: Marcus Antonius | Mark Antony/Julius Caesar, Marcus Antonius | Mark Antony & Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger, Marcus Antonius | Mark Antony & Gaius Cassius Longinus (d. 42 BCE), Mark Antony & Marcus Tullius Cicero, Mark Antony & Gaius Iulius Caesar Octavianus | Emperor Augustus, Mark Antony & Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Mark Antony & Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus | Pompey the Great

Characters: Marcus Antonius | Mark Antony, Julius Caesar, Marcus Junius Brutus the Younger, Gaius Cassius Longinus (d. 42 BCE), Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus | Emperor Augustus, Marcus Tullius Cicero, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus | Pompey the Great

Additional Tags: Double Drabble, Battle of Philippi, ides of March, War, Angst, Memory, Character Study

Summary:

A series of ficlets focused on Mark Antony during the 2nd Triumvirate: double drabbles, one for each pair.

#lemur writes#my fic#lemur romanus#mark antony#julius caesar#marcus junius brutus#gaius cassius longinus#octavian#marcus agrippa#pompey the great#marcus tullius cicero#and in the end rome itself#the harshest breakup#while the longest love affair has been between antony and his army

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cicero.exe has successfully rebooted.

#Rome#Rome HBO#Heroes of the Republic#Gaius Octavian Caesar#Cicero#Marcus Tullius Cicero#Danny watches Rome

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

salvete patres subscripti marcus tullius cicero is still alive. kind of

about e-pistulae | previous letters | subscribe to emails from cicero?

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

@nam-imperii please accept this meme

#tatiana the imperial#valania tullius#octavian tullius#skyrim#the elder scrolls#tes#skyrim oc#tes oc#meme

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most other Roman ppl are ego-shooters or some sophisticated video games.

Cicero is Animal Crossing.

Who agrees?

Does anyone want to create a list with Roman politicians and authors as games?

My suggestions would be...

I vote for Cato as Pong, Ludo or a chess computer.

Marcus Antonius would be GTA.

Sulla would be Pacman.

Caelius would be Mario and Catullus Luigi.

Clodius would be Bowser disguised as Princess Peach.

Marcus Tullius Tiro would be Doodle Jump.

Caesar as Candy Crush?

And Antonius would say that he never played GTA, but only ever played Candy Crush and then Octavian would throw the phone out of the window.

Kind of like that? I'm sure someone can improve that list. 😂😉😊📃

#marcus tullius cicero#cicero#tagamemnon#catilina#lucius sergius catilina#Caesar#gaius julius caesar#marcus tullius tiro#marcus antonius#marc antony#Tiro#octavian#octavian augustus

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In date 21 Last Seed of 4E 202 High Queen Elisif of Skyrim, ruler of the nordic imperial province, had to face the problematic of being both a young widow and the Queen of a recovering land. In an act which surprised many (and probably saved Skyrim) the Queen decided to crown Legate Octavian Tullius, the Last Dragonborn, as Proxy Ruler, acting as High King in her name. During the rule of High King Octavian, the Queen prepared herself in the arts of government and recovered from the grief and loss of her late husband death, returning to rule in her own name after some time. High King Octavian Tullius, a personal friend of Queen Elisif, gived the crown back as soon as she requested it despite the requests from some parts of the court to remain, declaring that he was glad to give Skyrim “a Queen that can truly save this land not with swords but with peace.”

-The Proxy High King and the Skyrim Regency Period, Brief History Of The Empire, Volume VI

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

8 Powerful Female Figures of Ancient Rome

Here are the Roman women who made their mark on the ancient empire.

Women in ancient Rome held very few rights and by law were not considered equal to men, according to a 2018 article on The Great Courses Daily. Roman women rarely held any public office or positions of power, and instead their role was expected to be caring for children and looking after the home.

Most women in Roman society were controlled by either their father or husband. Especially among richer families, women and young girls were married off in order to form political or financial relationships, and rarely could choose their partner.

Despite this lack of rights, there is evidence of a few exceptional women who managed to attain great power and influence in ancient Rome. While some controlled events from the sidelines, others took matters into their own hands, forming conspiracies and even assassination plots to seize control of the Roman empire.

Here are eight of ancient Rome's most influential and powerful women:

FULVIA:

Born into a noble family around 83 B.C., Fulvia was influential in Rome around the time of Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C. and built considerable personal wealth after she repeatedly became widowed. The earliest record of Fulvia describes the violent death of her first husband, a politician named Publius Clodius Pulcher.

"When a riot broke out during his campaign for office, Clodius was beaten to death by a mob paid for by a rival, Titus Annius Milo," historian Lindsay Powell told All About History magazine. "Fulvia and his mother dragged the corpse to the Roman Forum and swore to avenge his death."

In 49 B.C. her next husband, Gaius Scribonius Curio, was elected tribune, a powerful position in ancient Rome. Fulvia persuaded her deceased husband's followers to support Curio, said Joanne Ball, who has her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Liverpool in the U.K. "Fulvia was also adept at identifying the political mood within Rome, recognizing the value of allying with Julius Caesar and his populist cause, encouraging each of her husbands to form close links with Caesar," Ball said.

In 47 B.C., Fulvia married again — this time, to Mark Antony, Caesar's right-hand man. After Caesar's death three years later, Antony became one of three co-rulers of Rome, and the couple carried out a number of revenge killings, removing their political enemies, including politician Marcus Tullius Cicero. After Cicero's death in 43 B.C., Fulvia took the dead man's head, spat on it, took out the tongue and "pierced it with pins," according to Cassius Dio's "Roman History" (translation by Earnest Cary, through penelope.uchicago.edu).

The height of Fulvia's power was quickly followed by her downfall. In 42 B.C., Antony and his co-rulers left Rome to pursue Caesar's assassins, leaving Fulvia "de facto co-ruler of Rome," according to Ball. "In 41 B.C., in support of Antony's political ambitions, she opened hostilities with Octavian — Caesar's adopted son and Antony's main rival — raising eight legions in support of the cause," Ball said. "But by this stage, Antony's affections had been taken by Cleopatra of Egypt." Fulvia was defeated and died in 40 B.C., while exiled in Greece.

LIVIA DRUSILLA:

As the wife of Augustus (63 B.C.-A.D. 14), Rome's first emperor, Livia was one of the most powerful women during the early years of the Roman Empire. Though the couple did not produce an heir, Livia held a significant personal freedom,and was one of the most influential women Rome would ever see, according to Ball.

In A.D. 4, Augustus adopted Tiberius, Livia's son from a previous marriage, and appointed him his successor. After Augustus' death, Tiberius did become emperor; however, there were rumors that Livia had killed her husband after he intended to change his successor. According to ancient historian Cassius Dio, it was rumored that Livia "smeared with poison some figs that were still on trees … She ate those that had not been smeared, offering the poisoned ones to [Augustus]," (translation by Earnest Cary, through penelope.uchicago.edu).

The emperor's will granted Livia a new name Julia Augusta, which also served as an honorary title. According to Dio, she remained influential during her son's reign until her death in A.D. 29.

VALERIA MESSALINA:

Valeria Messalina was the third wife of Emperor Claudius (10 B.C.-A.D. 54), though she was at least 30 years younger. According to some historians, she had relationships with several members of the imperial court and allied herself with others to secure her position. "Her lovers were legion, the gossips said, and she was exhibitionist in her lusts," Michael Kerrigan wrote in his book "The Untold History of the Roman Emperors" (Cavendish Square Publishing LLC, 2016).

Messalina formed an influential clique of the most important men in the imperial court, whom she used to remove rivals and secure her powerful position and influence in Rome. "Whenever they desired to obtain anyone's death, they would terrify Claudius and, as a result, would be allowed to do anything they chose," Dio reports in "Roman History".

After the birth of Messalina's son, Brittanicus, she used her influence to remove any rival claimants to the imperial throne, Paul Chrystal wrote in his book "Emperors of Rome: The Monsters" (Pen and Sword Military, 2019). "The first to go was Pompeius Magnus (A.D. 30-47), the husband of Claudius's daughter Antonia, who was stabbed while in bed."

In A.D. 48, Messalina and her lover, an aristocrat and consul named Gaius Silius, married while Claudius was away from Rome. According to historian Tacitus' ancient text "Annals", the pair plotted to overthrow the emperor and rule together. After the couple's plan was discovered by the emperor, he had the couple executed.

AGRIPPINA THE YOUNGER:

At different points in her life, Agrippina was the wife, niece, mother and sister of some of the most famous emperors of ancient Rome, according to Emma Southon, author of "Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World" (Pegasus, 2019). In A.D. 39, her brother, Emperor Caligula (A.D. 12-41), exiled her for plotting against him, but she returned to Rome after he was assassinated in A.D. 41.

Eight years later, she married her uncle, Emperor Claudius. The emperor even changed the laws surrounding incest in order to marry his niece, who wielded a great amount of control over her new husband.

"Claudius was bad at politics and bad at ruling, and he was happy to accept help, even from his wife," Southon wrote. "Within a year, she had taken the honorific Augusta, making her Claudius' equal in name. Agrippina became intimately involved in the running and administering of the empire. She was her husband's partner in rule in every way. She broke every rule of appropriate female behaviour by refusing to be a quiet, passive wife."

Agrippina had her husband murdered by poison in A.D. 54, enabling her son Nero to take the throne, according to Tacitus's "Annals". While this secured her influence over the empire through her control over her young son, Nero soon conspired to kill Agrippina, whom he grew to resent because of her control over him. Tacitus describes how Agrippina survived several failed assassination attempts ordered by Nero before she was finally killed in A.D. 59.

HELENA:

Although little is known of her early life, Helena played a key part in the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, which led the Catholic Church to canonize her. She and her husband, Constantius, were separated before he became emperor in A.D. 293. It was not until her son Constantine became emperor in A.D. 306 that Helena began to assert her influence.

"Helena's story is unique in that her marriage has little bearing on her rise to fame," said Anneka Rene, a researcher at University of Auckland. Under her son's rule, Helena was elevated to the role of "dowager empress" with the honorary title of "Augusta Imperatrix," which gave her unlimited access to the imperial treasury, Rene said.

After converting to Christianity, Helena went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in A.D. 326. There, she ordered the building of churches at Jesus' birthplace in Bethlehem and at the site of his ascension near Jerusalem. While on this pilgrimage, she recovered a number of relics, including pieces of True Cross from Jesus' crucifixion.

"She would later be given a sainthood; her feast day is celebrated on May 21, Feast of the Holy Great Sovereigns Constantine and Helena, Equal to the Apostles," Rene said. "Her relics, and even her bones, are now found right across the world — most notably, her skull is on display in the Cathedral of Trier in Germany."

CLAUDIA METRODORA:

Although it was incredibly rare for women in ancient Rome to be directly involved in politics, Claudia Metrodora is one such example of a rich, powerful and influential person in her community.

A Greek woman with Roman citizenship, Metrodora held extraordinary power on the island of Chios, reaching the most important position on that island. "Metrodora held several political offices, including twice being appointed "stephanophoros," the highest magistracy on Chios, and "gymnasiarch" (meaning official) four times," Ball said.

Metrodora was also president of an important religious festival on three separate occasions. "One inscription in particular describes her as 'being desirous of glory for the city ... a lover of her homeland and priestess of life of the divine empress Aphrodite Livia, by reason of her excellence and admirable behaviour,'" Rene said. "Metrodora's life in Chios is most illuminating of the power and riches women could wield. Whilst often assumed that women held power mostly behind the throne, she instead takes centre stage in her own story."

Unlike some of ancient Rome's other influential women, Metrodora didn't marry into her power. "The most remarkable thing about Claudia Metrodora is how visible she was in public life in both Chios and Ephesus [an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey], defying the supposed conventions limiting female behaviour in the Roman-Greek world," Ball said. "She demonstrates that women could operate in civic life within the Romano-Greek world, financing public works and holding office in her own right, rather than wielding power indirectly through her husband or son."

AGRIPPINA THE ELDER:

The granddaughter of Emperor Augustus, Agrippina was ambitious but realized that as a woman, she would have to use the men around her to gain power in Rome, according to Rene. "As with many Roman women before her, Agrippina knew a Roman woman could wield little power on her own, so [she] used her wiles to best puppet those around her and wield power through her children," she said.

After marrying Germanicus Caesar, a popular army general, in A.D. 5, Agrippina joined him on his military campaigns, rather than remaining safe in the capital as was customary. "In A.D. 14, she was with him at great personal risk when he faced down mutinous legionaries in the camps of Germania Inferior," Powell said.

Agrippina even acted to stop the mutiny, presenting herself and her son Gaius, who would later become Emperor Caligula, before the mutinous soldiers, according to Ball. "She was clearly a quick-witted and bold woman who knew when to take risks in dangerous situations," Ball said.

After Germanicus mysteriously died in A.D. 19, Agrippina suspected he had been murdered. She returned to Rome with her three sons. "Artworks recall Agrippina personally ferrying the ashes of her husband home to Rome," Rene said. "Her arrival would be met with crowds of sympathizers, which continued to grow on her way from the port in Brundisium to Rome. This act would immortalize Agrippina as a loyal and devoted wife."

Once in the capital, Agrippina began promoting the claims of her sons to the throne, which created hostility between her and Tiberius. "She fell foul of Tiberius' regime, particularly his advisor Sejanus, who was wary of the popularity and potential political following Agrippina could command, particularly after she tried to convince Tiberius to adopt her sons as his heirs," Ball said. Several plots against the emperor implicated Agrippina, and she was arrested and exiled. She died in A.D. 33, three years before her younger son Caligula became emperor.

JULIA AVITA MAMAEA:

Born in Syria, then part of the Roman Empire, Julia Mamaea was from a noble and powerful family, which included Emperor Caracalla (A.D. 188-217), her cousin. After Caracalla was assassinated in A.D. 217, Julia's nephew Elagabalus eventually took the throne, and Julia and her son Alexander Severus were brought into the heart of the imperial court.

"Her son's time in court would lead him into favour with the Praetorian Guard, a unit who served as the emperor's bodyguard," Rene said. "Julia encouraged this support, reportedly distributing gold to them and encouraging them to keep her son safe from plots against him." Because she was a woman, Julia was not permitted to rule the empire, so she decided to pursue her ambitions through her son.

In A.D. 222, Elagabalus was assassinated, and the Praetorian Guard supported Severus as his successor, largely because of the political support that Mamaea had bought from the Praetorians, according to Ball. "Having bought her son's throne, Julia Mamaea became his Augusta, the highest rank a woman could be given," Ball said. "She was closely involved in the governance of the Empire — so much so that Alexander Severus became seen as an ineffective and weak emperor, impassive when compared to his mother, and a 'mama's boy.' Julia Mamaea dominated Imperial policy during her son's reign."

In A.D. 235, the army, frustrated by the emperor's lack of leadership, assassinated Mamaea and her son while she accompanied him on a campaign in Germania.

"In keeping a tight control over her son, Julia ultimately secured his downfall, as her influence meant that he could never develop into an effective leader in his own right, and in failing to secure the long-term support of the army, his long-term prospects would always be limited," Ball said. "Julia Mamaea knew that a Roman woman could only rule through her husband or son but forgot that her influence needed to be wielded as invisibly as possible. Her refusal, or inability, to step back would turn the Roman army against her son and led to his death and her own."

#8 Powerful Female Figures of Ancient Rome#romen women#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#powerful women#powerful roman women#ancient rome#roman culture#roman empire

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Tullius Cicero și sfârșitul republicii romane

Marcus Tullius Cicero și sfârșitul republicii romane

Om de stat, avocat, jurist, savant şi scriitor roman, care a încercat fără succes să menţină principiile republicane în timpul ultimelor războaie civile care au dus la căderea Romei. Scrierile sale includ lucrări de retorică, oratorie, tratate politice şi filozofice şi scrisori. În epoca modernă este considerat cel mai mare orator roman, cel care a inovat ceea ce astăzi se numeşte retorică…

View On WordPress

#al doilea triumvirat#augustus#caderea republicii#caesar#cezar#cicero#crassus#imperiul roman#marcus antonius#marcus tullius cicero#octavian#pompei#primul triumvirat#princeps senatus#razboi civil#republica romana#roma#trecerea rubiconului#ultimul republican

0 notes

Text

✨the powerful vibes✨

Gaius Octavian Caesar : Esteemed Senators, I take this first moment before you not to glorify myself, but to honor my father. In his honor I declare that my term as Consul shall usher in a new era. An era of moral virtue, of dignity, the debauchery and chaos that we had to endure will now end. Rome, shall be again as she once was. A proud Republic of virtuous women and honest men.

[the Senators applaud in approval]

Gaius Octavian Caesar : I speak to you now, not as a soldier or citizen. But as a grieving son. As my first act in this reborn Republic and in honor of my father I propose a motion.

[Cicero suspects something]

Gaius Octavian Caesar : To declare Brutus and Cassius, murderers. And enemies of the state.

[the Senators murmur amongst each other, Cicero then approaches Octavian]

Marcus Tullius Cicero : My dear boy this is not what we agreed.

Gaius Octavian Caesar : It is not. Nevertheless, here we are.

Marcus Tullius Cicero : Brutus and Cassisus didn't have many friends, you will strip a chamber. The unity of the REPUBLIC

Gaius Octavian Caesar : Step away from my chair!

[Cicero does as he's told]

Gaius Octavian Caesar : My father died on this floor. Right there. Stabbed 27 times, butchered, by men he called his friends. Who will tell me that is not murder? Who will tell my legions who loved Caesar as I do that that is not murder?

[Octavian's troops enter the hall and stand behind Octavian as they draw their swords]

Gaius Octavian Caesar : Who will speak against the motion?

https://youtu.be/GOlgZo5e7gI

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Fuck marry kill : octavian, cicero and agrippa

Absolutely killing Octavian

I think I'd fuck Cicero, but only if we get to do it on the rostra for thrills

I'll marry Agrippa, it gets me closer to Octavian so I can kill him, or maybe I can convince Agrippa that he's so much better than his best friend and should just take over and ACTUALLY restore the Republic. If not that, at least as Roman dudes go the sources we have that talk about Agrippa make it seem like he was a relatively decent husband. And even if he's not he's gonna be gone fighting Octavian's battles most of the time anyway. Only real downside to Agrippa is the fact I'm probably gonna be expected to have like 5 kids.

---------

Absolutely please send me more history asks folks ❤️

#fmk#fmk ancient rome#ancient Rome#absolutely send me more of these#asks#the rostra#cicero#m t chickpea#marcus tullius cicero#agrippa#Marcus Agrippa#marcus vipsanius agrippa#Octavianus#Augustus#Octavian#Caesar

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! so we have established at this point that you have A Lot Of thoughts about antony and brutus. but how does caesar (julius, not the little bitch octavian) play into that? bc like. my knowledge and impression of them is very limited and mainly constructed from watching hbo rome and idk. i think it'd be fun to throw caesar in the mix. love all the art and writing on your blog btw! have a nice day.

Hey, okay! So this used to be over 30 pages long (Machiavelli and Caligula got involved and that's when things got out of hand), but through the power of friendship and two late night writing dates fueled by coffee, I’ve cut it way down to under 10. Many thanks to the people who listened to me ramble about it at length, and also to a dear friend for helping me cut this down to under ten pages!

Also, thank you! I'm glad you enjoy the stuff I make! It makes me very happy to hear that!

And quickly, a Disclaimer: I’m not an academic, I’m not a classicist, I’m not a historian, and I spend a lot of time very stressed out that I’ve tricked people into thinking I’m someone who has any kind of merit in this area. It's probably best to treat this as an abstract character analysis!

On the other hand, I love talking about dead men, so, with enthusiasm, here we go!

For this, I’m going to cut Shakespeare and HBO Rome out of the framework and focus more on a historical spin.

Caesar is a combination of a manipulator and a catalyst. A Bad Omen. The remaining wound that’s poisoning Rome.

Cassius gets a lot of the blame for Brutus’ turn to assassination, but it overlooks that Brutus was already inclined towards political ambition, as were most men involved in the political landscape of the time.

Furthermore, although Sulla had actually raised the number of praetorships available from six to eight, there were still only two consulships available. There was always the chance that death or disgrace might remove some of the competition and hence ease the bottleneck. But, otherwise, it was at the top of the ladder that the competition was particularly fierce: whereas in previous years one in three praetors would have gone on to become consul, from the 80s BC onwards the chances were one in four. For the senators who had made it this far, it mattered that they should try to achieve their consulship in the earliest year allowed to them by law. To fail in this goal once was humiliating; to fail at the polls twice would be deemed a signal disgrace for a man like Brutus.

Kathryn Tempest, Brutus the Noble Conspirator

The way Caesar offered Brutus political power the way that he did, and Brutus accepting it, locked them into the assassination outcome.

Here is a man who’s built his entire image around honor and liberty and virtu, around being a staunch defender of morals and the republic

In these heated circumstances, Brutus composed a bitter tract On the Dictatorship of Pompey (De Dictatura Pompei), in which he staunchly opposed the idea of giving Pompey such a position of power. ‘It is better to rule no one than to be another man’s slave’, runs one of the only snippets of this composition to survive today: ‘for one can live honourably without power’, Brutus explained, ‘but to live as a slave is impossible’. In other words, Brutus believed it would be better for the Senate to have no imperial power at all than to have imperium and be subject to Pompey’s whim.

Kathryn Tempest, Brutus the Noble Conspirator

and you give him political advancement, but without the honor needed for this advancement to mean anything?

At the same time, however, Brutus had gained his position via extremely un-republican means: appointment by a dictator rather than election by the people. As the name of the famous career path, the cursus honorum, suggests, political office was perceived as an honour at Rome. But it was one which had to be bestowed by the populus Romanus in recognition of a man’s dignitas.69 In other words, a man’s ‘worth’ or ‘standing’ was only really demonstrated by his prior services to the state and his moral qualities, and that was what was needed to gain public recognition. Brutus had got it wrong. As Cicero not too subtly reminded him in the treatise he dedicated to Brutus: ‘Honour is the reward for virtue in the considered opinion of the citizenry.’ But the man who gains power (imperium) by some other circumstance, or even against the will of the people, he continues, ‘has laid his hands only on the title of honour, but it is not real honour’.70

Brutus may have secured political office, then, but he had not done so honourably; nor had he acted in a manner that would earn him a reputation for virtue or everlasting fame.

Kathryn Tempest, Brutus the Noble Conspirator

Brutus in the image that he fashioned for himself was not compatible with the way Caesar was setting him up to be a political successor, and there was really never going to be any other outcome than the one that happened.

The Brutus of Shakespeare and Plutarch’s greatest tragedy was that he was pushed into something he wouldn’t have done otherwise. The Brutus of history’s greatest tragedy was accepting Caesar’s forgiveness after the Caesar-Pompey conflict, and then selling out for political ambition, because Caesar's forgiveness is not benevolent.

Rather than have his enemies killed, he offered them mercy or clemency -- clementia in Latin. As Caesar wrote to his advisors, “Let this be our new method of conquering -- to fortify ourselves by mercy and generosity.” Caesar pardoned most of his enemies and forbore confiscating their property. He even promoted some of them to high public office.

This policy won him praise from no less a figure than Marcus Tullius Cicero, who described him in a letter to Aulus Caecina as “mild and merciful by nature.” But Caecina knew a thing or two about dictators, since he’d had to publish a flattering book about Caesar in order to win his pardon after having opposed him in the civil war. Caecina and other beneficiaries of Caesar’s unusual clemency took it in a far more ambivalent way. To begin with, most of them were, like Caesar, Roman nobles. Theirs was a culture of honor and status; asking a peer for a pardon was a serious humiliation. So Caesar’s “very power of granting favors weighed heavily on free people,” as Florus, a historian and panegyrist of Rome, wrote about two centuries after the dictator’s death. One prominent noble, in fact, ostentatiously refused Caesar’s clemency. Marcius Porcius Cato, also known as Cato the Younger, was a determined opponent of populist politics and Caesar’s most bitter foe. They had clashed years earlier over Caesar’s desire to show mercy to the Catiline conspirators; Cato argued vigorously for capital punishment and convinced the Senate to execute them. Now he preferred death to Caesar’s pardon. “I am unwilling to be under obligations to the tyrant for his illegal acts,” Cato said; he told his son, "I, who have been brought up in freedom, with the right of free speech, cannot in my old age change and learn slavery instead.

-Barry Strauss, Caesar and the Dangers of Forgiveness

something else that's a fun adjacent to the topic that's fun to think about:

The link between ‘sparing’ and ‘handing over’ is common in the ancient world.763 Paul also uses παραδίδωμι again, denoting ‘hand over, give up a person’ (Bauer et al. 2000:762).764 The verb παραδίδωμι especially occurs in connection with war (Eschner 2010b:197; Gaventa 2011:272).765 However, in Romans 8:32, Paul uses παραδίδωμι to focus on a court image (Eschner 2010b:201).766 Christina Eschner (2010b:197) convincingly argues that Paul’s use of παραδίδωμι refers to the ‘Hingabeformulierungen’ as the combination of the personal object of the handing over of a person in the violence of another person, especially the handing over of a person to an enemy.767 Moreover, Eschner (2009:676) convincingly argues that Isaiah 53 is not the pre-tradition for Romans 8:32.

Annette Potgieter, Contested Body: Metaphors of dominion in Romans 5-8

Along with the internal conflict of Pompey, the murderer of Brutus’ father, and Caesar, the figurehead for everything that goes against what Brutus stands for, Brutus accepting Caesar’s forgiveness isn’t an act of benevolence, regardless of Caesar’s intentions.

On wards, Caesar owns Brutus. Caesar benefits from having Brutus as his own, he inherits Brutus’ reputation, he inherits a better PR image in the eyes of the Roman people. On wards, nothing Brutus does is without the ugly stain of Caesar. His career is no longer his own, his life is no longer fully his own, his legacy is no longer entirely his. Brutus becomes a man divided.

And it’s not like it was an internal struggle, it was an entire spectacle. Hypocrisy is theatrical. Call yourself a man of honor and then you sell out? The people of Rome will remember that, and they’re going to make sure you know it.

After this certain men at the elections proposed for consuls the tribunes previously mentioned, and they not only privately approached Marcus Brutus and such other persons as were proud-spirited and attempted to persuade them, but also tried to incite them to action publicly. 12 1 Making the most of his having the same name as the great Brutus who overthrew the Tarquins, they scattered broadcast many pamphlets, declaring that he was not truly that man's descendant; for the older Brutus had put to death both his sons, the only ones he had, when they were mere lads, and left no offspring whatever. 2 Nevertheless, the majority pretended to accept such a relationship, in order that Brutus, as a kinsman of that famous man, might be induced to perform deeds as great. They kept continually calling upon him, shouting out "Brutus, Brutus!" and adding further "We need a Brutus." 3 Finally on the statue of the early Brutus they wrote "Would that thou wert living!" and upon the tribunal of the living Brutus (for he was praetor at the time and this is the name given to the seat on which the praetor sits in judgment) "Brutus, thou sleepest," and "Thou art not Brutus."

Cassius Dio

Brutus knew. Cassius knew. Caesar knew. You can’t escape your legacy when you’re the one who stamped it on coins.

Caesar turned Brutus into the dagger that would cut, and Brutus himself isn’t free from this injury. It’s a mutual betrayal, a mutual dooming.

By this time Caesar found himself being attacked from every side, and as he glanced around to see if he could force a way through his attackers, he saw Brutus closing in upon him with his dagger drawn. At this he let go of Casca’s hand which he had seized, muffled up his head in his robe, and yielded up his body to his murderers’ blows. Then the conspirators flung themselves upon him with such a frenzy of violence, as they hacked away with their daggers, that they even wounded one another. Brutus received a stab in the hand as he tried to play his part in the slaughter, and every one of them was drenched in blood.

Plutarch

For Antony, Caesar is a bad sign.

Brutus and Antony are fucked over by the generation they were born in, etc etc the cannibalization of Rome on itself, the Third Servile War was the match to the gasoline already on the streets of Rome, the last generation of Romans etc etc etc. They are counterparts to each other, displaced representatives of a time already gone by the time they were alive.

Rome spends its years in a state of civil war after civil war, political upheaval, and death. Neither Brutus or Antony will ever really know stability, as instability is hallmark of the times. Both of them are at something of a disadvantage, although Brutus has what Antony does not, and what Brutus has is what let’s him create his own career. Until Caesar, Brutus is owned by no one.

This is not the case for Antony.

You can track Antony’s life by who he’s attached to. Very rarely is he ever truly a man unto himself, there is always someone nearby.

In his youth, it is said, Antony gave promise of a brilliant future, but then he became a close friend of Curio and this association seems to have fallen like a blight upon his career. Curio was a man who had become wholly enslaved to the demands of pleasure, and in order to make Antony more pliable to his will, he plunged him into a life of drinking bouts, love-affairs, and reckless spending. The consequence was that Antony quickly ran up debts of an enormous size for so young a man, the sum involved being two hundred and fifty talents. Curio provided security for the whole of this amount, but his father heard of it and forbade Antony his house. Antony then attached himself for a short while to Clodius, the most notorious of all the demagogues of his time for his lawlessness and loose-living, and took part in the campaigns of violence which at that time were throwing political affairs at Rome into chaos.

Plutarch

(although, in contrast to Brutus, we rarely lose sight of Antony. As a person, we can see him with a kind of clarity, if one looks a little bit past the Augustan propaganda. He is, at all times, human.)

Antony being figuratively or literally attached to a person starts early, and continues politically. While Brutus has enough privilege to brute force his way into politics despite Cicero’s lamentation of a promising life being thrown off course, Antony will instead follow a different career path that echoes in his personal life and defines his relationships.

Whereas some young men often attached or indebted themselves to a patron or a military leader at the beginning of their political lives,

Kathryn Tempest, Brutus the Noble Conspirator

+

3. During his stay in Greece he was invited by Gabinius, a man of consular rank, to accompany the Roman force which was about to sail for Syria. Antony declined to join him in a private capacity, but when he was offered the command of the cavalry he agreed to serve in the campaign.

Plutarch

To take it a step further, it even defines how he’s perceived today looking back: it’s never just Antony, it’s always Antony and---

It can be read as someone being taken advantage of, in places, survival in others, especially in Antony's early life. Other times, it appears like Antony himself is the one who manipulates things to his favor, casting aside people and realigning himself back to an advantage.

or when he saw an opportunity for faster advancement, he was willing to place the blame on a convenient scapegoat or to disregard previous loyalties, however important they had been. His desertion of Fulvia's memory in 40, and, much later, of Lepidus, Sextus Pompey, and Octavia, produced significant political gains. This characteristic, which Caesar discovered to his cost in 47, gives the sharp edge to Antony's personality which Syme's portrait lacks, especially when he attributes Antony's actions to a 'sentiment of loyalty' or describes him as a 'frank and chivalrous soldier'. In this context, one wonders what became of Fadia.19

Kathryn E Welch , Antony, Fulvia, and the Ghost of Clodius in 47 B.C.

Caesar inherits Antony, and like Brutus, locks him in for a doomed ending.

The way Caesar writes about Antony smacks of someone viewing another person as something more akin to a dog, and it carries over until it’s bitter conclusion.

Caesar benefits from Antony immensely. The people love Antony, the military loves Antony. He’s charming, he’s self aware, he’s good at what he does. Above all of that, he has political ambitions of a similar passion as Brutus.

Antony drew some political benefit from his genial personality. Even Cicero, who from at least 49 did not like him,15 was prepared to regard some of his earlier misdemeanours as harmless.16 Bluff good humour, moderate intelligence, at least a passing interest in literature, and an ability to be the life and soul of a social gathering all contributed to make him a charming companion and to bind many important people to him. He had a lieutenant's ability to follow orders and a willingness to listen to advice, even (one might say especially) from intelligent women.17 These attributes made Antony able to handle some situations very well."1

There was a more important side to his personality, however, which contributed to his political survival. Antony was ruthless in his quest for pre-eminence

Kathryn E Welch , Antony, Fulvia, and the Ghost of Clodius in 477 B.C.

None of this matters, because after all Antony does for Caesar

Plutarch's comment that Curio brought Antony into Caesar's camp is surely mistaken.59 Anthony had been serving as Caesar's officer from perhaps as early as 53, after his return from Syria.60 He is described as legatus in late 52,61 and was later well known as Caesar's quaestor.62 It is more likely that the reverse of the statement is true, that Antony assisted in bringing Curio over to Caesar. If this were so, then he performed a signal service for Caesar, for gaining Curio meant attaching Fulvia, who provided direct access to the Clodian clientela in the city. Such valuable political connections served to increase Antony's standing with Caesar, and to set him apart from other officers in his army.63

Kathryn E Welch , Antony, Fulvia, and the Ghost of Clodius in 477 B.C.

Caesar still, for whatever reasons, fucks over Antony spectacularly with the will. Loyalty is repaid with dismissal, and it will bury the Republic for good.

It’s not enough for Caesar to screw him over just once, it becomes generational and ugly. Caesar lives on through Octavian: it becomes Octavian’s brand, his motif, propaganda wielded like a knife. Octavian, thanks to Caesar, will bring Antony to his bitter conclusion

And for my "bitter" conclusion, I’ll sign off by saying that there are actual scholars on Antony who are more well versed than I am who can go into depth about the Caesar-Octavian-Antony dynamic (and how it played out with Caligula) better than I can, and scholarship on Brutus consists mostly of looking at an outline of a man and trying to guess what the inside was like.

At the end of the day, Caesar was the instigator, active manipulator, and catalyst for the final act of the Republic.

I hope that this was at least entertaining to read!

#i cut out A Lot and its thanks to the patience of Friends that i got it down to the length that it is#like i cannot stress enough that i worked machiavelli into this and started dissecting the whole#brutus-cassius conflict with the framework that it was orchestrated by caesar#typically tho i tend to treat caesar as a symbolic device. a representation of something Very Wrong#this is a tag for asks

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“F**k Ulfric squad, assemble!”

“I am not wearing this…”

Left to Right:

Elisif, Nord, High Queen of Skyrim, has seen too much and must be protected and loved

Octavian (LDB of OneGuy in the Frozen Hearth Discord), Imperial, Son of General Tullius, Head chopper extraordinaire

Heidi(LDB of me), Half Nord half Altmer, Wielder of Auriels Bow, Sunshine nerd

Loric(LDB of @transseptims), Dunmer, Reincarnation of Shor/Lorkhan, entirely Done with Ulfric’s shenanigans

General Tullius, Imperial, Leader of the Legion in Skryim, Tired Old Man (tm)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 powerful female figures of ancient Rome

Women in ancient Rome held very few rights and by law were not considered equal to men, according to a 2018 article on The Great Courses Daily. Roman women rarely held any public office or positions of power, and instead their role was expected to be caring for children and looking after the home.

Most women in Roman society were controlled by either their father or husband. Especially among richer families, women and young girls were married off in order to form political or financial relationships, and rarely could choose their partner.

Despite this lack of rights, there is evidence of a few exceptional women who managed to attain great power and influence in ancient Rome. While some controlled events from the sidelines, others took matters into their own hands, forming conspiracies and even assassination plots to seize control of the Roman empire.

Here are eight of ancient Rome’s most influential and powerful women.

Fulvia

“The Vengeance of Fulvia” by Francisco Maura y Montaner. (Image credit: Public Domain / Museo municipal de Bellas Artes de Santa Cruz de Tenerife)

Born into a noble family around 83 B.C., Fulvia was influential in Rome around the time of Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 B.C. and built considerable personal wealth after she repeatedly became widowed. The earliest record of Fulvia describes the violent death of her first husband, a politician named Publius Clodius Pulcher.

“When a riot broke out during his campaign for office, Clodius was beaten to death by a mob paid for by a rival, Titus Annius Milo,” historian Lindsay Powell told All About History magazine. “Fulvia and his mother dragged the corpse to the Roman Forum and swore to avenge his death.”

Related: Did all roads lead to Rome?

In 49 B.C. her next husband, Gaius Scribonius Curio, was elected tribune, a powerful position in ancient Rome. Fulvia persuaded her deceased husband’s followers to support Curio, said Joanne Ball, who has her doctorate in archaeology from the University of Liverpool in the U.K. “Fulvia was also adept at identifying the political mood within Rome, recognizing the value of allying with Julius Caesar and his populist cause, encouraging each of her husbands to form close links with Caesar,” Ball said.

In 47 B.C., Fulvia married again — this time, to Mark Antony, Caesar’s right-hand man. After Caesar’s death three years later, Antony became one of three co-rulers of Rome, and the couple carried out a number of revenge killings, removing their political enemies, including politician Marcus Tullius Cicero. After Cicero’s death in 43 B.C., Fulvia took the dead man’s head, spat on it, took out the tongue and “pierced it with pins,” according to Cassius Dio’s “Roman History” (translation by Earnest Cary, through penelope.uchicago.edu).

The height of Fulvia’s power was quickly followed by her downfall. In 42 B.C., Antony and his co-rulers left Rome to pursue Caesar’s assassins, leaving Fulvia “de facto co-ruler of Rome,” according to Ball. “In 41 B.C., in support of Antony’s political ambitions, she opened hostilities with Octavian — Caesar’s adopted son and Antony’s main rival — raising eight legions in support of the cause,” Ball said. “But by this stage, Antony’s affections had been taken by Cleopatra of Egypt.” Fulvia was defeated and died in 40 B.C., while exiled in Greece.

Livia Drusilla

Livia remained influential in Roman politics after Augustus’ death. (Image credit: George E. Koronaios / CC BY-SA 4.0)

As the wife of Augustus (63 B.C.-A.D. 14), Rome’s first emperor, Livia was one of the most powerful women during the early years of the Roman Empire. Though the couple did not produce an heir, Livia held a significant personal freedom,and was one of the most influential women Rome would ever see, according to Ball.

Related: Why did Rome fall?

In A.D. 4, Augustus adopted Tiberius, Livia’s son from a previous marriage, and appointed him his successor. After Augustus’ death, Tiberius did become emperor; however, there were rumors that Livia had killed her husband after he intended to change his successor. According to ancient historian Cassius Dio, it was rumored that Livia “smeared with poison some figs that were still on trees … She ate those that had not been smeared, offering the poisoned ones to [Augustus],” (translation by Earnest Cary, through penelope.uchicago.edu).

The emperor’s will granted Livia a new name Julia Augusta, which also served as an honorary title. According to Dio, she remained influential during her son’s reign until her death in A.D. 29.

Valeria Messalina

Messalina almost managed to take down the empire from the inside. (Image credit: Public Domain / Vienna Museum)

Valeria Messalina was the third wife of Emperor Claudius (10 B.C.-A.D. 54), though she was at least 30 years younger. According to some historians, she had relationships with several members of the imperial court and allied herself with others to secure her position. “Her lovers were legion, the gossips said, and she was exhibitionist in her lusts,” Michael Kerrigan wrote in his book “The Untold History of the Roman Emperors” (Cavendish Square Publishing LLC, 2016).

Messalina formed an influential clique of the most important men in the imperial court, whom she used to remove rivals and secure her powerful position and influence in Rome. “Whenever they desired to obtain anyone’s death, they would terrify Claudius and, as a result, would be allowed to do anything they chose,” Dio reports in “Roman History”.

After the birth of Messalina’s son, Brittanicus, she used her influence to remove any rival claimants to the imperial throne, Paul Chrystal wrote in his book “Emperors of Rome: The Monsters” (Pen and Sword Military, 2019). “The first to go was Pompeius Magnus (A.D. 30-47), the husband of Claudius’s daughter Antonia, who was stabbed while in bed.”

In A.D. 48, Messalina and her lover, an aristocrat and consul named Gaius Silius, married while Claudius was away from Rome. According to historian Tacitus’ ancient text “Annals”, the pair plotted to overthrow the emperor and rule together. After the couple’s plan was discovered by the emperor, he had the couple executed.

Agrippina the Younger

Agrippina married Emperor Claudius after he executed his third wife, Valeria Messalina. (Image credit: Public Domain)

At different points in her life, Agrippina was the wife, niece, mother and sister of some of the most famous emperors of ancient Rome, according to Emma Southon, author of “Agrippina: The Most Extraordinary Woman of the Roman World” (Pegasus, 2019). In A.D. 39, her brother, Emperor Caligula (A.D. 12-41), exiled her for plotting against him, but she returned to Rome after he was assassinated in A.D. 41.

Eight years later, she married her uncle, Emperor Claudius. The emperor even changed the laws surrounding incest in order to marry his niece, who wielded a great amount of control over her new husband.

Related: The weird reason Roman emperors were assassinated

“Claudius was bad at politics and bad at ruling, and he was happy to accept help, even from his wife,” Southon wrote. “Within a year, she had taken the honorific Augusta, making her Claudius’ equal in name. Agrippina became intimately involved in the running and administering of the empire. She was her husband’s partner in rule in every way. She broke every rule of appropriate female behaviour by refusing to be a quiet, passive wife.”

Agrippina had her husband murdered by poison in A.D. 54, enabling her son Nero to take the throne, according to Tacitus’s “Annals”. While this secured her influence over the empire through her control over her young son, Nero soon conspired to kill Agrippina, whom he grew to resent because of her control over him. Tacitus describes how Agrippina survived several failed assassination attempts ordered by Nero before she was finally killed in A.D. 59.

Helena

Helena converted to Christianity and was canonized by several Christian churches. (Image credit: Public Domain/ National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC, United States). )

Although little is known of her early life, Helena played a key part in the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, which led the Catholic Church to canonize her. She and her husband, Constantius, were separated before he became emperor in A.D. 293. It was not until her son Constantine became emperor in A.D. 306 that Helena began to assert her influence.

“Helena’s story is unique in that her marriage has little bearing on her rise to fame,” said Anneka Rene, a researcher at University of Auckland. Under her son’s rule, Helena was elevated to the role of “dowager empress” with the honorary title of “Augusta Imperatrix,” which gave her unlimited access to the imperial treasury, Rene said.

After converting to Christianity, Helena went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in A.D. 326. There, she ordered the building of churches at Jesus’ birthplace in Bethlehem and at the site of his ascension near Jerusalem. While on this pilgrimage, she recovered a number of relics, including pieces of True Cross from Jesus’ crucifixion.

“She would later be given a sainthood; her feast day is celebrated on May 21, Feast of the Holy Great Sovereigns Constantine and Helena, Equal to the Apostles,” Rene said. “Her relics, and even her bones, are now found right across the world — most notably, her skull is on display in the Cathedral of Trier in Germany.”

Claudia Metrodora

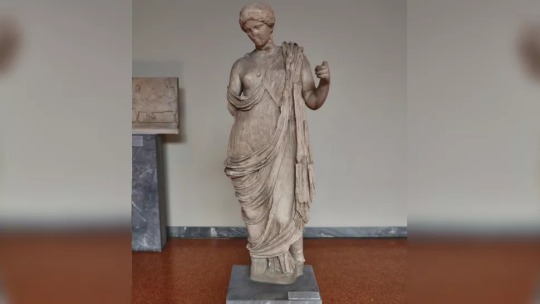

Claudia Metrodora was a Roman-Greek priestess devoted to Aphrodite Livia; pictured here is a contemporary statue of the goddess Aphrodite Livia that was discovered in Epidaurus, Greece. (Image credit: George E. Koronaios / CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although it was incredibly rare for women in ancient Rome to be directly involved in politics, Claudia Metrodora is one such example of a rich, powerful and influential person in her community.

A Greek woman with Roman citizenship, Metrodora held extraordinary power on the island of Chios, reaching the most important position on that island. “Metrodora held several political offices, including twice being appointed “stephanophoros,” the highest magistracy on Chios, and “gymnasiarch” (meaning official) four times,” Ball said.

Metrodora was also president of an important religious festival on three separate occasions. “One inscription in particular describes her as ‘being desirous of glory for the city … a lover of her homeland and priestess of life of the divine empress Aphrodite Livia, by reason of her excellence and admirable behaviour,'” Rene said. “Metrodora’s life in Chios is most illuminating of the power and riches women could wield. Whilst often assumed that women held power mostly behind the throne, she instead takes centre stage in her own story.”

Unlike some of ancient Rome’s other influential women, Metrodora didn’t marry into her power. “The most remarkable thing about Claudia Metrodora is how visible she was in public life in both Chios and Ephesus [an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey], defying the supposed conventions limiting female behaviour in the Roman-Greek world,” Ball said. “She demonstrates that women could operate in civic life within the Romano-Greek world, financing public works and holding office in her own right, rather than wielding power indirectly through her husband or son.”

Agrippina the Elder

A painting depicting Agrippina Landing at Brundisium, with the ashes of Germanicus. (Image credit: Getty)

The granddaughter of Emperor Augustus, Agrippina was ambitious but realized that as a woman, she would have to use the men around her to gain power in Rome, according to Rene. “As with many Roman women before her, Agrippina knew a Roman woman could wield little power on her own, so [she] used her wiles to best puppet those around her and wield power through her children,” she said.

After marrying Germanicus Caesar, a popular army general, in A.D. 5, Agrippina joined him on his military campaigns, rather than remaining safe in the capital as was customary. “In A.D. 14, she was with him at great personal risk when he faced down mutinous legionaries in the camps of Germania Inferior,” Powell said.

Agrippina even acted to stop the mutiny, presenting herself and her son Gaius, who would later become Emperor Caligula, before the mutinous soldiers, according to Ball. “She was clearly a quick-witted and bold woman who knew when to take risks in dangerous situations,” Ball said.

After Germanicus mysteriously died in A.D. 19, Agrippina suspected he had been murdered. She returned to Rome with her three sons. “Artworks recall Agrippina personally ferrying the ashes of her husband home to Rome,” Rene said. “Her arrival would be met with crowds of sympathizers, which continued to grow on her way from the port in Brundisium to Rome. This act would immortalize Agrippina as a loyal and devoted wife.”

Once in the capital, Agrippina began promoting the claims of her sons to the throne, which created hostility between her and Tiberius. “She fell foul of Tiberius’ regime, particularly his advisor Sejanus, who was wary of the popularity and potential political following Agrippina could command, particularly after she tried to convince Tiberius to adopt her sons as his heirs,” Ball said. Several plots against the emperor implicated Agrippina, and she was arrested and exiled. She died in A.D. 33, three years before her younger son Caligula became emperor.

Julia Avita Mamaea

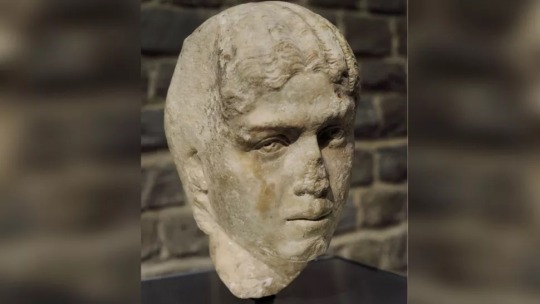

A bust of Julia Avita Mamaea, dated between A.D. 222 and 235. (Image credit: Getty / Universal History Archive)

Born in Syria, then part of the Roman Empire, Julia Mamaea was from a noble and powerful family, which included Emperor Caracalla (A.D. 188-217), her cousin. After Caracalla was assassinated in A.D. 217, Julia’s nephew Elagabalus eventually took the throne, and Julia and her son Alexander Severus were brought into the heart of the imperial court.

“Her son’s time in court would lead him into favour with the Praetorian Guard, a unit who served as the emperor’s bodyguard,” Rene said. “Julia encouraged this support, reportedly distributing gold to them and encouraging them to keep her son safe from plots against him.” Because she was a woman, Julia was not permitted to rule the empire, so she decided to pursue her ambitions through her son.

In A.D. 222, Elagabalus was assassinated, and the Praetorian Guard supported Severus as his successor, largely because of the political support that Mamaea had bought from the Praetorians, according to Ball. “Having bought her son’s throne, Julia Mamaea became his Augusta, the highest rank a woman could be given,” Ball said. “She was closely involved in the governance of the Empire — so much so that Alexander Severus became seen as an ineffective and weak emperor, impassive when compared to his mother, and a ‘mama’s boy.’ Julia Mamaea dominated Imperial policy during her son’s reign.”

In A.D. 235, the army, frustrated by the emperor’s lack of leadership, assassinated Mamaea and her son while she accompanied him on a campaign in Germania.

“In keeping a tight control over her son, Julia ultimately secured his downfall, as her influence meant that he could never develop into an effective leader in his own right, and in failing to secure the long-term support of the army, his long-term prospects would always be limited,” Ball said. “Julia Mamaea knew that a Roman woman could only rule through her husband or son but forgot that her influence needed to be wielded as invisibly as possible. Her refusal, or inability, to step back would turn the Roman army against her son and led to his death and her own.”

Additional resources

New post published on: https://livescience.tech/2021/10/24/8-powerful-female-figures-of-ancient-rome/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELDER MORTIMER

...

And, seeing his mind so doats on Gaveston,

Let him without controlment have his will.

The mightiest kings have had their minions:

Great Alexander loved Hephestion;

The conquering Hercules for Hylas wept;

And for Patroclus stern Achilles drooped.

And not kings only, but the wisest men:

The Roman Tully lov’d Octavius;

Grave Socrates, wild Alcibiades.

- Christopher Marlowe, Edward II, I.3

Very funny, Marlowe. You know, there is no wonder Isabella in the film tore her necklace on hearing this.

3 notes

·

View notes