#odo of bayeux

Text

The Bastard Kings and their families

This is series of posts are complementary to this historical parallels post from the JON SNOW FORTNIGHT EVENT, and it's purpouse to discover the lives of medieval bastard kings, and the following posts are meant to collect portraits of those kings and their close relatives.

In many cases it's difficult to find contemporary art of their period, so some of the portrayals are subsequent.

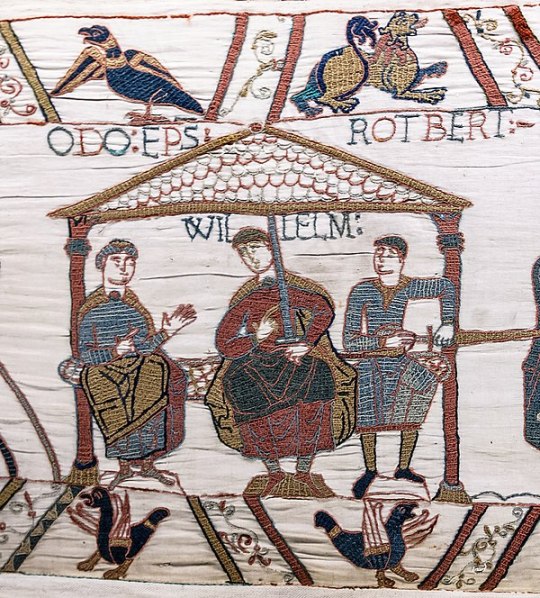

1) William I of England (c. 1028 – 1087), son of Robert I of Normandy and Herleva of Falaise; with his brothers Odo of Bayeux (d. 1097) and Robert of Mortain (c. 1031–c. 1095), sons of Herleva of Falaise and her husband Herluin de Conteville

2) His father, Robert I of Normandy (1000 –1035), son of Richard II of Normandy and his wife Judith of Brittany

3) His uncle, Richard III of Normandy (997/1001 – 1027), son of Richard II of Normandy and his wife Judith of Brittany

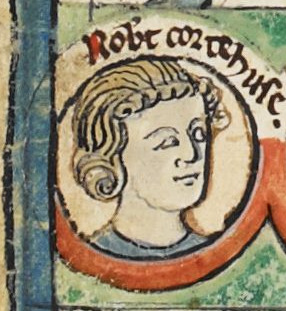

4) His son, Robert II of Normandy (c. 1051 – 1134), son of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

5) His son, William II of England( c. 1057 – 1100), son of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

6) His son, Henry I of England (c. 1068 –1135), son of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

7) His daughter, Cecily of Normandy (c. 1056 – 1126), daughter of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

8) His daughter, Constance of Normandy (c. 1057/61– 1090), daughter of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

9) His daughter, Adela of Normandy (c. 1067– 1137), daughter of William I of England and Matilda of Flanders

#jonsnowfortnightevent2023#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#day 10#echoes of the past#historical parallels#medival bastard kings#bastard kings and their families#william i of england#william the conqueror#odo of bayeux#robert of mortain#robert i of normandy#richard iii of normandy#robert ii of normandy#william ii of england#henry i of england#cecily of normandy#adela of normandy#constance of normandy#canonjonsnow

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

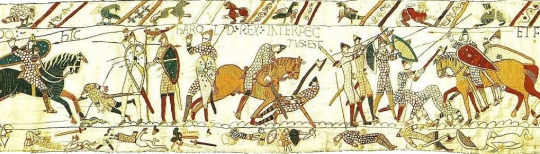

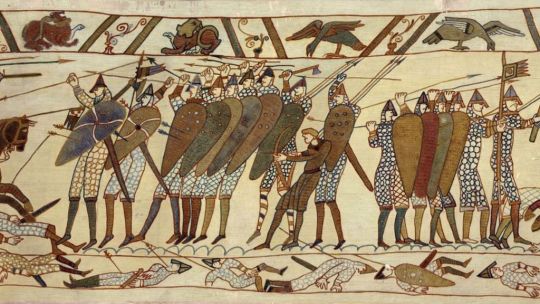

“Stand fast! Stand fast!” The Battle of Hastings

#1066#battle of hastings#bishop#odo of bayeux#william the conqueror#england#norman conquest#normans#anglo saxons#anglo saxon#bayeux tapestry#normandy#wace#roman de rou#conquest#invasion#art#painting#history#tom lovell#europe#knights#club#mace#white horse

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

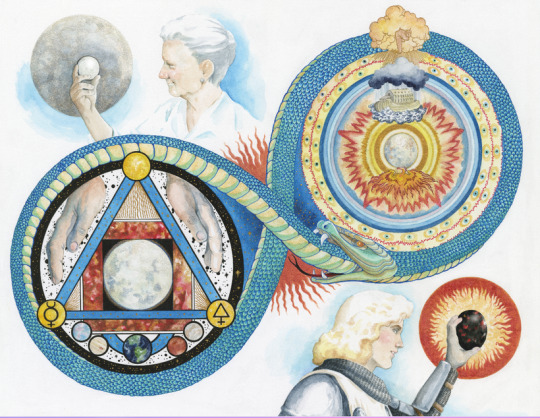

Neil Gaiman's CHIVALRY: From Illuminated Manuscripts to Comics

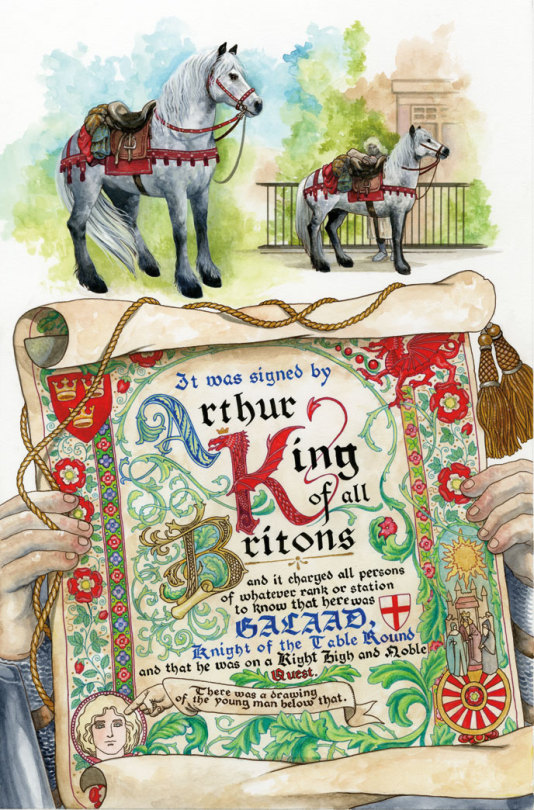

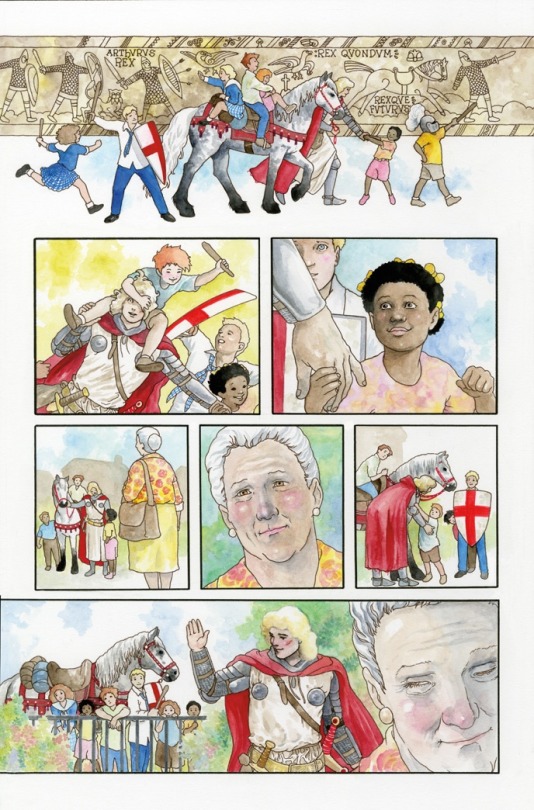

One of the many reasons I wanted to adapt Neil Gaiman's Chivalry into graphic novel form was to create a comic as a bridge and commentary re: comics and illuminated manuscripts.

We're often told that the first comic book was Action Comics #1 featuring Superman, a collection of Superman comic strips that morphed into comic books as an art form.

Sequential art predates Action Comics #1.

Action Comics popularized sequential art book storytelling that had already appeared in other forms in fits and starts throughout history. Comic books didn't take off as a popular medium for several reasons, not least of which was the necessary printing process hadn't been invented yet and it's hard to popularize - and commercialize - something most people can never see.

You find sequential art in cave paintings and in Egyptian hieroglyphics. I've read that comics (manga) were invented by the Japanese in 12th century scrolls.

And sequential art appears over and over again in Western art going back well over 1000 years, and in book form at least 1100 years ago.

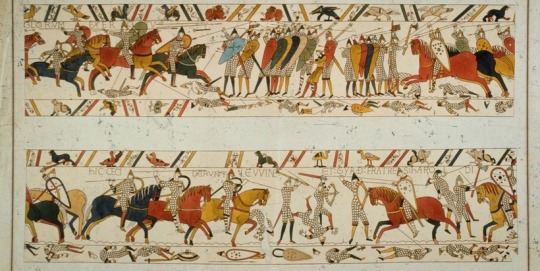

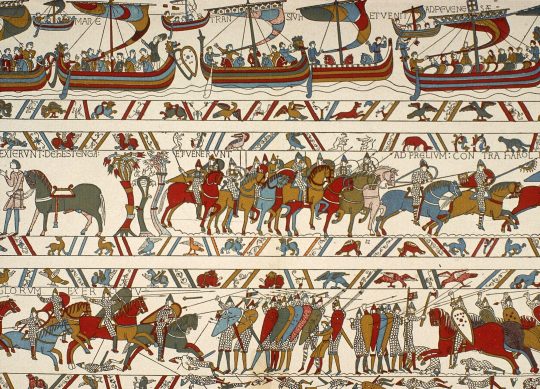

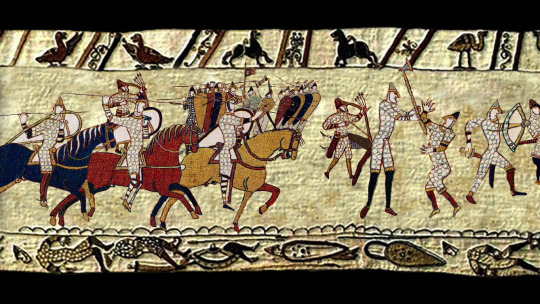

The most obvious example of early sequential art in Western art - as a complete narrative in sequence - is the Bayeux Tapestry.

At 230 feet long, this embroidered length of cloth was likely commissioned around the year 1070 by Bishop Odo, brother of William the Conqueror. It depicts the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the invasion of England by the Normans. (The tapestry was made in England, not in France, but it is called the Bayeux tapestry because that's where it is now.)

Imagine what a task it was to embroider this thing. Whew. And you thought it was hard learning Photoshop.

This work of art is important in the history of sequential narrative, but the Norman invasion is also important to the legend of King Arthur - and another important English legend - for reasons we'll get into later.

It's complicated.

All this is why you see this art in the background of this page of Chivalry.

Using the Romanesque art style of the tapestry in panel 1, I've added the Latin phrase "Rex Quondom, Rexque Futurus" - "The Once and Future King", the final words of Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur as inscribed on King Arthur's tomb, and the title of T.H. White's famous Arthurian novel. (EDIT) and it has been kindly pointed out to me that QUONDOM should be QUONDAM, which is hilarious and annoying and this is how history gets rewritten by accident.

My original intention was to draw this Bayeux Tapestry scene out and juxtapose it with shots of Galaad interacting with the children, but the two page sequence I imagined didn't really work as well in reality as it did in my head.

Foremost among my concerns was that the tapestry reference might be too obscure for most readers. I wanted to weave the visual meta-text of Chivalry into the story (For further reading on this project and my use of visual meta-text, symbolism, and history in Neil Gaiman's Chivalry, go HERE. And HERE. And HERE. And Yet again HERE.) in such a way as it would enhance the experience for people who "got" the visual meaning, while not dragging things down for people who didn't. So I cut this scene down to one panel.

The tapestry is a complete, long form comic strip created over 1100 years before some people claim comics were invented. So, I loved being able to reference it here.

But even more interesting to me are the sequential art sequences that appear in illuminated manuscripts - comics in book form.

I once got into a rather vicious argument with an academic who insisted illuminated manuscripts were comics. I said no. She said yes. Then she insulted the lowly comic artist and blocked me on Facebook.

Whatever.

My point was not that you can't find sequential art in illuminated manuscripts. My point is that an illustrated book isn't de facto a comic. Most illuminated manuscripts are illustrated books. Some illuminated manuscripts contain sequential art.

Just because opera is music, that doesn't mean all music is opera.

Just because comics books are books that doesn't mean all books are comic books.

And just because some illuminated manuscripts contain sequential art, that doesn't mean all illuminated manuscripts are sequential art.

But one is.

Let me show you it.

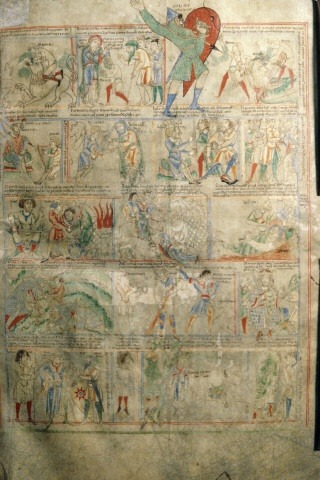

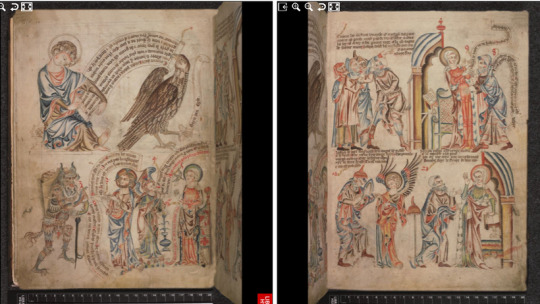

One of the earliest examples of an illuminated manuscript with comic art is The Bible d'Etienne Harding which you can see in this really bad jpg here, sorry, best I could find.

Created around the year 1109, property of a French Cistercian monk, it combines sequences like this with pages of text and illustration.

Not a comic book IMHO, but an illuminated manuscript with sequences of text, illustration and sequential narrative.

It's no more a "comic book" than a newspaper is for having text, illustration, and comic strips in it.

IMHO, academic lady.

And here's a look at the Old English Hexateuch (hexateuch refers to the first 6 books of the Bible) which I think is far more visually complex and interesting work, and comes much closer to the illuminated manuscript as comic, but still intersperses large sequences of text and illustration with sequential storytelling sequences. So I don't consider it a comic, but a book with sequential work in it.

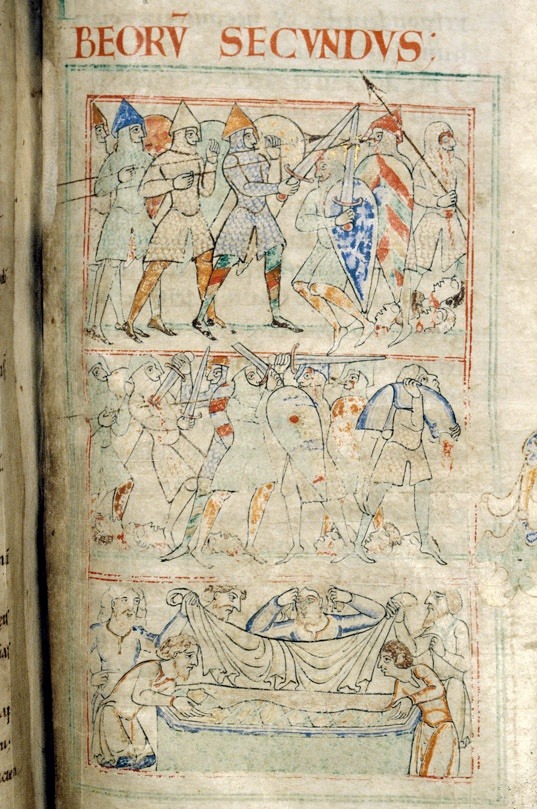

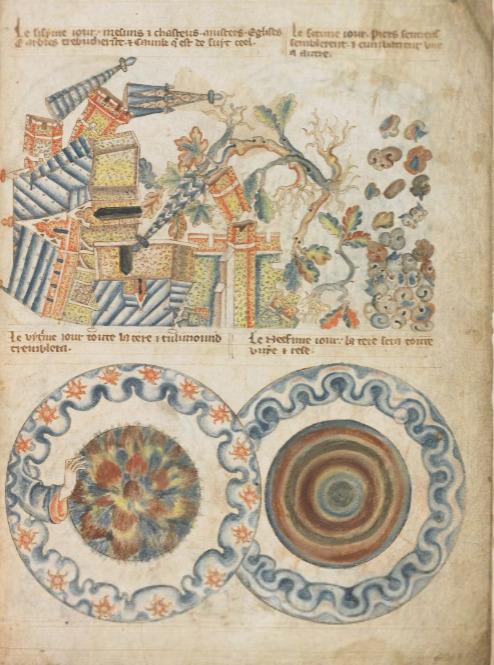

Now this work below is a different matter. This is from the Holkham Bible Picture Book, circa about 1330.

This thing is genius. It measures a little larger than a modern comic, around 8"x11", and almost every page of it is like this spread here. 231 pages of beautifully rendered art, with repeated use of banderoles - "speech scrolls" (basically word balloons) - and captions, and (mostly) real sequential art. I've never seen anything else that comes even close to it, and by all accounts, neither has anyone else.

It may not be a modern comic book - but it's a comic book as far as I can tell. I don't think there's any other illuminated manuscript that is as complete, sophisticated, and innovative a sequential storytelling work.

If this were printed and seen by more people, the comic book medium would have taken off centuries earlier, IMHO. But it wasn't. It was tucked away in a monastery somewhere and few people ever saw it. It ended up being forgotten for centuries until it popped up again around 1816 when a banker sold it to an avid book collector, Thomas Coke, Earl of Leicester, who inherited Holkham Hall and its library and set about restoring and expanding it.

The banker wrote, “a very curious MS. just brought here from the Continent. . . which I think one of the greatest curiosities I ever saw”.

Sequential art got invented over and over and over by one artist after another until one day centuries later, some teenaged boys found their newspaper strips gathered together in a cheap format, and suddenly comic books were popular and like new.

And then a lot of people who didn't seem to realize that books had had pictures in them for centuries got all up in arms about the harms of books with pictures in them.

I think it's funny that it is called the Holkham Bible Picture Book. There really was no "comic" art language when this work was created or when academics began to catalogue this sort of thing. Will they change the name now?

Who can say.

Anyway, another Holkham Bible Picture Book reference for you.

Look familiar?

I referenced it in this scene in Chivalry.

One of the fun things about the Holkham is that it opens with a discussion between a friar who has commissioned the work and the artist. The friar admonishes the artist to do a good job on the project because it will be shown to important people. And the artist responds, "Indeed, I certainly will and, if God lets me live, never will you see another such book."

He wasn't kidding.

You can see the entire manuscript HERE.

Sponsored by my Patreon. Thank you.

#chivalry#neilgaiman#neil gaiman#darkhorsecomics#dark horse comics#illuminated manuscript#medieval art#medieval manuscripts#watercolor#watercolor art#king arthur#arthuriana#arthurian legend#sir galahad

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

history facts!!!!!!! yes please

ANON SO TRUE!!!!

HISTORY FACT! the Bayeux Tapestry is NOT a tapestry, nor is it from Bayeux. it's an embroidery (tapestries are made on looms - this was not), and it was created by nuns in Canterbury. it may have been commissioned by Odo of Bayeux but it's not actually from there.

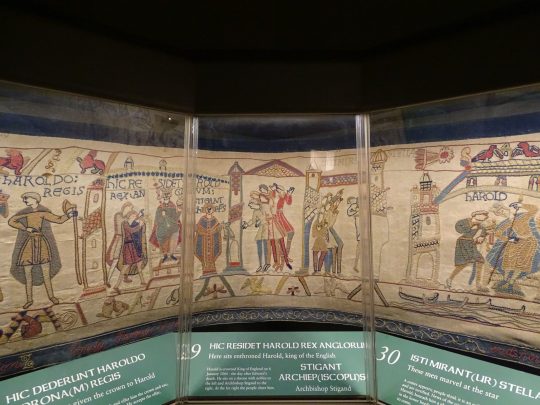

Bonus since we're on the topic - that guy everyone thinks is Harold Godwinson on the Bayeux Tapestry??? that ain't him.

Beneath the name 'Harold', we can see a man with an arrow in his eye, and for a long time people have assumed this was Harold Godwinson (who was King of England at the time) but it's NOT

And we know it's not him for a couple of reasons

As a general rule, the action described in the tapestry text typically appears at the end of the sentence. The man believed to be Harold is not in the right place for this to be correct

Recent examinations of the tapestry have found that the thread used to embroider the arrow in 'Harold's' eye dates back to the 19th Century. The Bayeux Tapestry was made in the 11th Century. This was not an original addition (typical Victorians, fucking with history - but that's a rant for another post)

By looking at accounts from around the time of the Battle of Hastings, we know Harold didn't die from an arrow to the eye - dude got dismembered real bad <3

So when we consider all of this, it's much more likely that the real Harold Godwinson is actually the man on the ground to the right of the figure most people label as him👍

#if anyone found this interesting please consider reading Femina by Janina Ramirez. she's got a whole chapter on this and it's really good#also she was on an episode of You're Dead To Me talking about it a while back - that's a great podcast 10/10 would reccommend#ask#history#british history#bayeux tapestry#harold godwinson

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

https://open.spotify.com/user/31hir66czgfvygtganeff2bw5rfy?si=-ZM12np-QVisyiWX-DyNWA btw mutuals if i don’t have you already on spotify ADD ME!! and try to ignore that my profile pic is bishop odo from the bayeux tapestry

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon and the Bayeux Tapestry

In 1803-1804, this tapestry was borrowed from Bayeux in Normandy for a two-month exhibition at the Musée Napoléon (Louvre).

Vivant Denon’s letter to the sub-prefect of Bayeux the following year:

“I am sending back to you the Tapestry embroidered by Queen Matilda, wife of William the Conqueror. The First Consul has seen with interest this precious monument of our history, he has applauded the care that the habitants of the city of Bayeux have brought for seven and a half centuries to its conservation. He has charged me to testify to them all his satisfaction and to entrust them with the deposit. Invite them to bring new care to the conservation of this fragile monument, which retraces one of the most memorable actions of the French Nation.”

(20 February 1804)

Napoleon attended the opening of the exhibition on 5 December 1803, with Denon and Visconti.

A press release for the exhibition was published in the ‘Beaux-Arts’ column in Le Moniteur on 29 November and in the tabloid Journal de Paris on 28 November. Visconti wrote a guide for the artwork which was partially reprinted in Le Moniteur.

The tapestry was returned to Bayeux two months later, on 18 February 1804. Many in Paris wanted to keep it in the city, but Napoleon ordered that it be returned.

Previously, the historic tapestry had been confiscated during the French Revolution. It was covering military wagons and almost cut up when a local lawyer, Léonard Lambert-Leforestier, saved it by sending it to city administrators for safekeeping.

The tapestry depicts the William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy. The piece was made about a decade after his 1066 invasion of England and the purpose of the tapestry was to glorify the invasion.

It was displayed to the public in Bayeux in 1812 and has been publicly displayed ever since:

“From 1812 the Tapestry was kept in the Hotel de Ville (city hall) in Bayeux. It was generally hung and displayed to the public in September of every year. In addition, the custodian could show it to visitors, rolling it out gradually on a table by turning the crank handle of a winder: this way of exhibiting it was described on several occasions by British writers between 1814 and 1836. From 1842, it was put on permanent display for the first time in the Matilda gallery.”

Sources:

Susan Jaques, The Caesar of Paris: Napoleon Bonaparte, Rome, and the Artistic Obsession that Shaped an Empire

Carola Hicks, The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece

Bayeux Museum: From Odo’s Cathedral to the Louvre

#Bayeux Tapestry#Bayeux#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#napoleonic#napoleonic era#first french empire#french empire#19th century#william the conqueror#France#history#art#norman invasion#1066#Susan Jaques#Carola Hicks#The Caesar of Paris#The Caesar of Paris: Napoleon Bonaparte Rome and the Artistic Obsession that Shaped an Empire#Vivant Denon#Denon#tapestry#embroidery#tapestries#Middle Ages#medieval#medieval history#french history#louvre

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bishop Odo of Bayeux was William the Conqueror's right hand man during his conquest of Anglo-Saxon England. How did this cunning, power-hungry nobleman make it to such a powerful position? And was he really a bishop?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herleva (died c. 1050) was an 11th-century Norman woman known for having been mother of William the Conqueror, born to an extramarital relationship with Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and also of William's prominent half-brothers Odo of Bayeux and Robert, Count of Mortain, born to Herleva's marriage to Herluin de Conteville.

0 notes

Photo

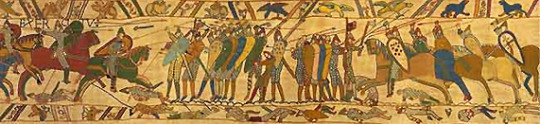

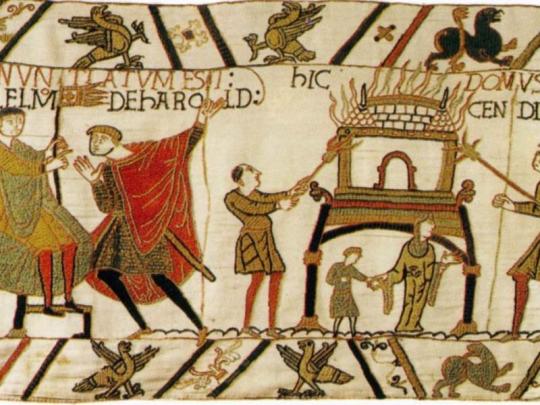

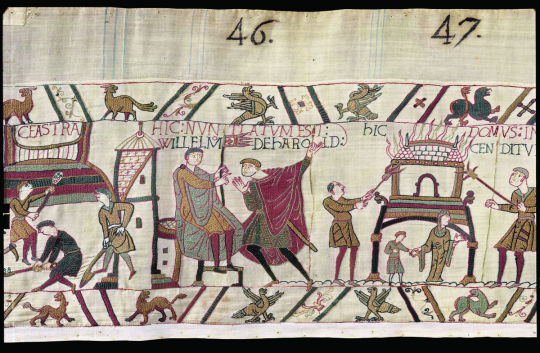

Hic Odo Eps Bacvlv Tenens Confortat Pveros -- Here Odo the Bishop (Episcopus) holding a cudgel (baculum) strengthens (gives courage to) the boys

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts Bishop Odo of Bayeux carrying a crude-looking club at the Battle of Hastings. This is one of the sources that inspired D&D clerics being limited to blunt weapons in early editions.

The club actually was a common symbol of authority, like a scepter but more functional in a fight, and Odo’s half-brother Duke William is shown to carry a similar one. Hic Est VVilel Dvx:

#D&D#Dungeons & Dragons#cleric#medieval#Bayeux Tapestry#medieval history#gaming history#history#latin#Bishop Odo#Odo of Bayeux#dnd#Dungeons and Dragons

108 notes

·

View notes

Link

Twin sent me this! This woman made (is making?) a full size Bayeux Tapestry!

Looook!

AHHH! THIS IS SO COOL!!! She’s got a whole album of more that 230 pictures of the process!

#Sword speaks#Bayeux Tapestry#Anglo-Saxon England#English history#Ancient England#British history#William the Conqueror#the Norman Invasion#Odo of Bayeux#the Battle of Hasings#history#1066#fibercrafts#tapestry#embroidery#sewing

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The nave of Bayeux Cathedral was recently restored. The Norman-Romanesque lower level was built between 1047 and 1077. The upper level, side aisles, and apse were added in the 13th century.

The famous Bayeux Tapestry (kept in a nearby museum) was probably commissioned by Bishop Odo who built the Norman Cathedral. Odo was the half-brother of William the Conquerer, and the tapestry depicts the Norman version of events leading up to William’s conquest of England in 1066. The tapestry was custom-made to hang along three walls of the cathedral’s nave, probably just above the rounded arches. It may have been made specifically for the consecration of the cathedral in 1077, which was attended by William and his family. It was displayed annually in the cathedral until 1803.

There is a plan to loan the Bayeaux Tapestry to the British Museum in London for display in 2022 or 2023. It would be the first time it would leave France in 950 years.

Photos by Charles Reeza, October 2021

#Norman architecture#Gothic architecture#church#pipe organ#vaulted ceiling#history of France and England#Norman conquest#Battle of Hastings

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bertha de Blois, Duchess Consort of Brittany and Countess of Maine (c. 1005-1084):

Bertha was the daughter of Odo of Blois and Ermengarde of Auvergne. She was married to Duke Alan III of Brittany in 1028. By all accounts seems to have been a successful marriage- even in charters, which historically had been fairly neutrally-worded documents, Bertha would refer to Alan in affectionate terms. With Alan, she gave birth to the future Duke Konan II and Duchess Hawiz. Her happiness was not to last however, as events would take a sharp turn.

The Bretons and Normans had historically been enemies, clashing over territory for years, and the pattern did not change in Alan’s reign. While his mother, Havoise of Normandy, had managed to form important bonds that spared Brittany war temporarily with the Normans, the peace dissolved quickly after her death. In the 1030′s, Duke Robert I had besieged the town of Dol, leading to years of raiding back and forth between the two duchies. A truce was finally settled between Robert and Alan, and the two began to work more closely politically. Several years later, Robert left for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and left his illegitimate son as heir with Alan as his the future William I’s guardian. Not long after, Robert I died on the return journey in 1035; William became Duke of Normandy at age 8 with Alan as protector. Soon death would come for Alan as well as he fell victim to a poisoning plot, dying suddenly in 1040.

Records show that Bertha was greatly saddened by losing her husband, but also distraught- her son would be succeeding as Duke at a only a few months old, and the Breton-Norman conflict had only escalated. The Normans were not the only force she needed to contend with, however, as her brother-in-law Eozen of Penthièvre was also attempting to gain control of the Breton government through guardianship of the young Konan II. Bertha and later her son Konan would vie for power with Eozen, leading to her seeking an alliance with the County of Maine by marrying Hugh IV in 1046.

Bertha would split her time in Maine with time counseling her son in Brittany, sharing authority with Eozen. Her alliance with Maine certainly helped her position, and she had two children with Hugh, but her fortune soon ran out in 1051. Civil war broke out in Maine; Hugh had died and left Bertha widowed, and chased out of the county. Bertha and her two children by Hugh sought refuge in Brittany with her daughter and son-in-law, Hawiz and Hoël de Cornouaille. During her exile, she returned to the side of her son Konan II who was now of legal age to rule. It was likely her that influenced him to favor abbeys with strong ties to Blois-Chartres, granting him a strong ally to challenge Eozen for power. Konan occasionally visited his uncle, Count Thibault III of Chartres, often assisting him in military pursuits in the region.

The alliance with Blois-Chartres would only do so much. Konan II and Eozen went to war, and Eozen was able to call upon his own familial ally: William I of Normandy. The conflict then began to draw in the Normans and English Saxons as well. Some of the events concerning this period are depicted in the beginning of the Bayeux Tapestry. In the fall of 1066, Konan was preparing to attack Castle Gontier in Anjou, but suddenly sickened and died. Rumors spread that Konan had refused to help William conquer England because of the animosity he held from his father’s poisoning, and in retaliation William had Konan poisoned himself. Whether illness or assassination, Konan was buried by December 1066 at the age of 26. Shortly after, his sister was proclaimed duchess, beginning the ducal dynasty of Cornouaille. Following Konan’s death, Bertha returned to her home in Blois where she died in 1084.

#historyedit#bertha de blois#absolute babe#she worked so hard and had such a sad life#she outlived both of her husbands but also both konan and hawiz that's so rough ;_;#eleventh century#my edit

119 notes

·

View notes

Note

If/when they make a Joe/Nicky prequel movie, what are some of the Dos and Don’ts for them, with regards to historical accuracy. Like, what do you think they should include, and what do you think they should avoid?

Oof. This is a GREAT question, and also designed to give me a chance to ramble on in a deeply, deeply self-indulgent fashion. That is now what will proceed to happen. Consider yourself warned. So if they were miraculously to be like “well that qqueenofhades person on tumblr seems like she knows what she’s talking about, let’s hire her to consult on this production!”, here are some of the things I would tell them.

First off, a question I have in fact asked my students when teaching the crusades in class is whether you could actually show the sack of Jerusalem on screen. Like... if you’re making a film about the First Crusade, what kind of choices are you going to make? What narrative viewpoint are you going to uphold throughout the story? Are you actually going to show a slaughter of Muslim and Jewish inhabitants that some chroniclers described as causing enough blood to reach up to the knees of horses? (Whether it actually did this is beside the point; the point is that the sack went far beyond the accepted conventions of warfare and struck everybody involved in it as particularly horrific.) Because when you’re making a film about the crusades, you are also making it by nature for a modern audience that has particular understandings of Christian/Muslim conflict, religious warfare and/or tolerance, the War on Terror, the modern clash over ISIS, Trump’s Muslim ban, and so forth. The list goes on and on. So you’re never making a straight, unbiased historical adaptation, even if you’re going off the text of primary sources. You’re still constructing it and presenting it in a deliberate and curated fashion, and you can bet that whichever way you come down, your audience will pick up on that.

Let’s take the most recent example of a high-profile crusades film: Kingdom of Heaven from 2005. I’ve written a book chapter on how the narrative choices of KoH, aside from its extensive fictionalization of its subject matter to start with, make it crystal clear that it is a film made by a well-meaning Western liberal filmmaker (Ridley Scott) four years after 9/11 and two years after the invasion of Iraq, when the sympathy from 9/11 was wearing off and everyone saw America/Great Britain and the Bush/Blair coalition overreaching itself in yet another arrogant imperial adventure into the Middle East. Depending on how old you are, you may or may not remember the fact that Bush explicitly called the War on Terror a “crusade” at the start, and then was quickly forced to walk it back once it alarmed his European allies (yes, back then, as bad as America was, it still did have those) with its intellectual baggage. They KNEW exactly what images and tropes they were invoking. It is also partly why medieval crusade studies EXPLODED in popularity after 9/11. Everyone recognized that these two things had something to do with each other, or they made the connection somehow. So anyone watching KoH in 2005 wasn’t really watching a crusades film (it is set in the late 1180s and dramatizes the surrender of Jerusalem to Saladin) so much as a fictional film about the crusades made for an audience explicitly IN 2005. I have TONS to say on this subject (indeed, if you want a copy of my book chapter, DM me and I’ll be happy to send it.)

Ridley Scott basically sets it up as the Christian and Muslim secular leaders themselves aren’t evil, it’s all the religious fanatics (who are all made Templars, including Guy de Lusignan, going back to the “evil Templar” trope started by Sir Walter Scott and which we are all so very familiar with from Dan Brown and company). Orlando Bloom’s character shares a name (Balian de Ibelin) but very little else with the eponymous real-life crusader baron. One thing Scott did do very well was casting an actual and well-respected Syrian actor (Ghassan Massoud) to play Saladin and depicting him in essential fidelity to the historical figure’s reputed traits of justice, fairness, and mercy (there’s some article by a journalist who watched the film in Beirut with a Muslim audience and they LOVED the KoH Saladin). I do give him props for this, rather than making the Evil Muslim into the stock antagonist. However, Orlando Bloom’s Balian is redeemed from the religious extremist violence of the Templars (shorthand for all genuinely religious crusaders) by essentially being an atheistic/agnostic secular humanist who wants everyone to get along. As I said, this is a film about the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq made three years after 9/11 more than anything else, and you can really see that.

That said, enough about KoH, back to this presumable Joe/Nicky backstory. You would obviously run into the fact that it’s SUPER difficult to make a film about the crusades without offending SOMEBODY. The urge to paint in broad strokes and make it all about the evil Westerners invading is one route, but it would weaken the moral complexity of the story and would probably make it come off as pandering to guilty white liberal consciences. Are we gonna touch on the many decades of proto-crusading ventures in Iberia, Sicily, North Africa, and other places, and how the eleventh century, especially under Pope Gregory VII, made it even thinkable for a Christian to be a holy warrior in the first place? (It was NOT normal beforehand.) How are we going to avoid the “lololol all religion sucks and makes people do crazy things” axe to grind favoured by So Very Smart (tm) internet atheists? Yes, we have to demonstrate the ultimate horror of the crusade and the flawed premises it was based on, but we can’t do that by just showing the dirty, religiously zealot medieval people doing that because they don’t know any better and are being cynically manipulated in God’s Name. In other words (and the original TOG film did this very well) we can’t position ourselves to laugh at or mock the crusader characters or feel confident in looking down on them for being Dumb Zealots. They have to be relatable enough that we realize we could BE (and in fact already ARE) them, and THEN you slide into the horror and what compels them to do those kinds of things, and THAT’S when it hits. Because take a look at the news. This is happening around us right now.

Obviously, as I was doing in my First Crusade chapter in DVLA, a lot of this also has to spend time centering the Muslim point of view, the way they reacted to the crusade, the ways in which Yusuf as an Isma’ili Shia Muslim (Kaysani is the name of a branch of Isma’ili Shi’ites, he has a definite historical context and family lineage, and hence is almost surely, as I wrote him, a Fatimid from Egypt) is likewise not just A Stock Muslim. In this case, obviously: Get actual Muslims on the set to advise about the details. Don’t make stupid and/or obvious mistakes. Don’t necessarily make the Muslims less faithful or less virtuous than the Christians (even if this is supposed to praise them as being “less fanatic” than those bad religious Catholics). Don’t tokenize or trivialize their reaction to something as horrific as the sack of Jerusalem, and don’t just use dead brown bodies as graphic visual porn for cheap emotional points. Likewise, it goes without saying, and I don’t think they would anyway, but OH MY GOD DON’T MAKE THIS INTO GAME OF THRONES GRIMDARK!!!! OH MY GOD!!! THERE IS BEAUTY AND THERE IS LIGHT AND THERE IS POETRY AND THAT’S WHY IT HURTS SO MUCH WHEN IT’S DESTROYED! AND THE CHOICES THAT PEOPLE MAKE TO DESTROY THOSE THINGS HAVE TO BE TERRIFYINGLY PLAUSIBLE AND FAMILIAR, BECAUSE OH MY GOD!!

Next, re: Nicolo. Evidently he is a priest or a former priest or something of the sort in the graphic novel, which becomes a bit of a problem if we want him to actually FIGHT in the crusades for important and/or shallow and/or OTP purposes. (I don’t know if they address this somehow or Greg Rucka is not a medieval historian or whatever, but never mind.) It was a Major Thing that priests could not carry weapons, at least and especially bladed weapons. (In the Bayeux Tapestry, we have Odo, the bishop of Bayeux, fighting at the battle of Hastings with a truncheon because he’s a clergyman and can’t have a sword). They were super not supposed to shed blood, and a broadsword (such as the type that Nicky has and carries and is clearly very familiar with) is a knight’s weapon, not a clergyman’s. The thing about priests was that they were not supposed to get their hands dirty with physical warfare; they could (and often did) accompany crusade armies, bishops were secular overlords and important landholders, monks and hermits and other religious preachers were obviously part of a religious expedition, and yes, occasionally some priests would break the rules and fight in battle. But this was an exception FAR more than the rule. So if we’re going by accuracy, we have Nicky as a priest who doesn’t actively fight and doesn’t have a sword, we have him as a rule-breaking priest with a sword (which would have to be addressed, and the Templars, who were basically armed monks, weren’t founded until 1119 so he can’t be one of those yet if this is still 1099) or we just skip the priest part and have him as a crusader with a sword like any other soldier. If he was in fact a priest, he also wouldn’t be up to the same standard of sending into battle. Boys, especially younger sons of the nobility, often entered the church at relatively early ages (12 or 13), where it was treated as a career, and hence they stopped training in arms. So if Nicky is actually out there fighting and/or getting killed by Yusuf several times for Important Purposes, he’s... almost surely not a priest.

Iirc, they’ve already changed a few things from the graphic novel (I haven’t read it, but this is what I’ve heard) so they can also tweak things to make a new backstory or a hybrid-new backstory in film-verse. So once we’ve done all the above, we still have to decide how to handle the actual sack of Jerusalem and massacre of its inhabitants, the balance between violence comparable to the original TOG film and stopping short of being exploitative (which I think they would do well), and the aftermath of that and the founding of the new Latin Christian kingdom. It would have to, as again the original film does very well, avoid prioritizing the usual players and viewpoints in these events, and dig into presenting the experiences of the marginalized and way in which ordinary people are brought to the point of doing these things. It doesn’t (and frankly shouldn’t) preach at us that U.S. Invasions Of The Middle East Are Bad (especially since obviously none of the characters/people/places/events here are American at all). And as I said already but bears repeating: my god, don’t even THINK about making it GOT and marketing it as Gritty Dramatic Medieval History, You Know It’s Real Because They’re Dirty, Violent, and Bigoted!

Also, a couple tags I saw pop up were things like “Period-Typical Racism” and “Period-Typical Homophobia” and mmm okay obviously yes there are these elements, but what exactly is “period typical?” Does it mean “using these terms just because you figure everyone was less tolerant back then?” We know that I, with my endless pages of meta on medieval queer history, would definitely side-eye any attempts to paint these things as Worse Than Us, and the setting alone would convey a sense of the conflict without having to add on gratuitous microaggressions. I basically think the film needs to be made exactly like the original: centering the gay/queer perspectives of marginalized people and people of color, resisting the urge for crass jokes at the expense of the identity of its characters, and approaching it with an awareness of the deep complexity and personal meaning of these things to people in terms of the historical moment we’re in, while not making a film that ONLY prizes our response and our current crises. Because if we’re thinking about these historical genealogies, the least we can do (although we so often aren’t) is to be honest.

Thanks! I LOVED this question.

#history#medieval history#kingdom of heaven#joe x nicky#long post#persephone-rose-r#ask#the old guard meta

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Original Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry is preserved and displayed in Bayeux, in Normandy, France. Nothing is known for certain about the tapestry’s origins. The first written record of the Bayeux Tapestry is in 1476 when it was recorded in the cathedral treasury at Bayeux as “a very long and narrow hanging on which are embroidered figures and inscriptions comprising a representation of the conquest of England”.

The Bayeux Tapestry was probably commissioned in the 1070s by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror. It is over 70 metres long and although it is called a tapestry it is in fact an embroidery, stitched not woven in woollen yarns on linen. Some historians argue that it was embroidered in Kent, England. The original tapestry is on display at Bayeux in Normandy, France.

- The Victorian Replica -

“England should have a copy of its own”

It was the idea of Elizabeth Wardle to make the replica Bayeux Tapestry, now on display in Reading Museum. She was a skilled embroiderer and a member of the Leek Embroidery Society in Staffordshire. Her husband, Thomas Wardle was a leading silk industrialist. Elizabeth Wardle researched the Bayeux Tapestry by visiting Bayeux in 1885. The Society also based the replica on hand-coloured photographs of the tapestry held by the South Kensington Museum, now called the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. The aim of the project was to make a full-sized and accurate replica of the Bayeux Tapestry “so that England should have a copy of its own”.

Thirty-five women members of the Leek Embroidery Society worked under Elizabeth Wardle’s direction. This ambitious project was completed in just over a year. As well as members from Leek, women from Derbyshire, Birmingham, Macclesfield and London took part. Each embroiderer stitched her name beneath her completed panel.

- Touring The Replica -

The replica Bayeux Tapestry was first exhibited in the Nicholson Institute in Leek in 1886. Over the next ten years the tapestry was put on display in towns and cities across Britain and it even travelled to Germany and America.

- A Permanent Home In Reading -

In 1895 the replica Bayeux Tapestry was exhibited in the Town Hall at Reading. The Reading exhibition was supported by Alderman Arthur Hill, a former Mayor. Hill offered to buy the replica. This offer was accepted by the Leek Embroidery Society. He then presented the tapestry as a gift to Reading where it was displayed in the Reading Museum and Art Gallery.

- A New Bayeux Tapestry Gallery -

In 1993 a new Bayeux Tapestry gallery was opened in the Museum. The tapestry was carefully conserved and remounted as a continuous strip in a specially designed display case. For the first time for many years the entire tapestry could be seen in one gallery. Now you can visit the Bayeux Tapestry gallery and see for yourself the work of the skilled Victorian women of Leek as well as discovering the story of the Norman Conquest.

The original Tapestry is over 70 metres long and depicts 626 human figures, 190 horses, 35 dogs, 506 other birds and animals, 33 buildings, 37 ships and 37 trees or groups and trees, with 57 Latin inscriptions. Here are a few of the people that appear in the Tapestry.

- The Three Kings -

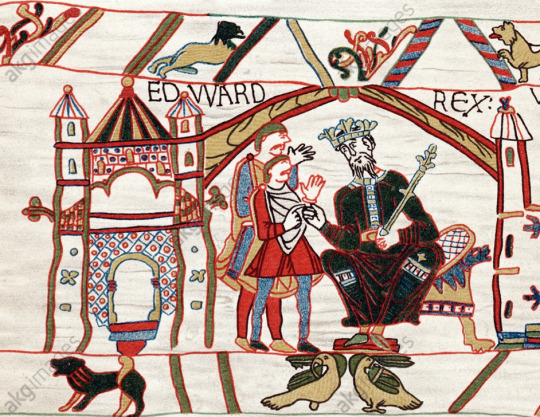

Edward the Confessor

King of England, 1042-1066

Edward was the son of the Saxon King Ethelred (the Unready) and Emma, sister of Duke Richard II of Normandy. Emma later married Cnut, King of Denmark. Cnut became King of England and Edward went to live in exile in Normandy.

When Cnut died in 1042 his son Harthacnut was made King of England. But Harthacnut died without leaving an heir so Edward became King in 1042 and was crowned at Winchester in 1043. He ruled with the help of the powerful Saxon earls and married Edith, daughter of Godwin, Earl of Wessex. Edward invited many of his Norman friends to come to England; he gave them important jobs and land. He ordered the building of Westminster Abbey.

Because Edward had no children, he had to choose someone to succeed him. There were many claimants to the throne. One was Harold, Earl of Wessex, Edward’s brother-in-law; another was Harold Hardrada, King of Norway, and a third was William, Duke of Normandy. The strongest claim was from Edgar Aetheling, Edward’s great nephew who had been raised by Edward since 1057 when he was 4 years old. The Normans said that Edward had promised the throne to William, but Harold Godwinson was chosen to succeed Edward who died in January 1066.

Harold

King of England, Jan - Oct 1066

Harold had no hereditary claim on the throne - he was not of royal birth. He was the son of Godwin, in his time the most powerful Saxon earl. Harold’s sister, Emma, was married to Edward the Confessor and had at least 5 brothers. The tapestry shows us that Harold had fought with William against the Duke of Brittany and shows him swearing upon holy relics. When Edward the Confessor died Harold was chosen to be King of England by the leading Saxon noblemen.

Right away Harold had problems. His brother Tostig accompanied Harold Hardrada King of Norway when he invaded England. Both Hardrada and Tostig were killed by Harold’s army at the Battle of Stamford Bridge near York. At the same time William of Normandy had brought his army to England to claim the throne. Harold marched from Stamford Bridge to London then on to Hastings where William’s army waited.

The English and Norman armies fought bravely, but Harold with his brothers Gyrth and Leofwine were all killed. The tapestry tells us “here King Harold has been killed” - struck down by the sword of a mounted Norman soldier. After the Battle of Hastings Williams had an abbey built on the place where the battle had been fought, and the high altar is supposed to mark the spot where Harold was killed.

William of Normandy

King of England, 1066-1087

William’s father was Duke Robert and his mother was Herleva who was a tanner’s daughter. Duke Robert’s great-great-grandfather was Rollo, a Viking who invaded France in 911. Although he was illegitimate William became Duke of Normandy when he was only seven years old - his father died on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. William’s mother married the Viscount of Conteville and had two more sons - Odo and Robert.

William was a strong leader and wanted to become King of England. William led his army at the Battle of Hastings where Harold was killed and his army defeated. William then set about the conquest of England; he gave Norman barons pieces of land all over the country and in return they supported him in war and administered regions of England on the king’s behalf.

During his reign William ordered the collection of information about the people in Britain and how much property they owned. This information was recorded in the Domesday Book. William died in 1087 after being injured when fighting in France.

- The Clerics -

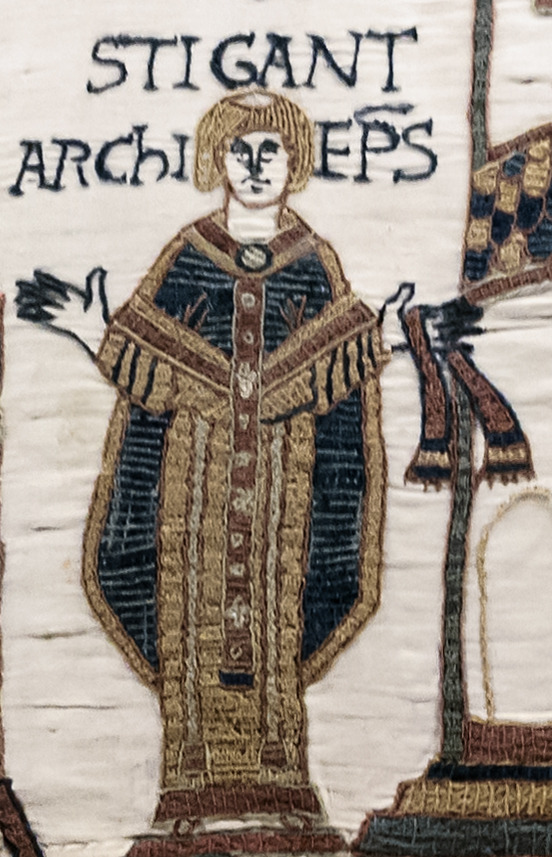

Odo

Bishop of Bayeux

Odo’s father was Herluin, Viscount of Conteville and his mother was Herleva who was also the mother of Duke William of Normandy. When Odo was only nineteen years old, William made him Bishop of Bayeux. He built a cathedral there.

When William was planning to invade England, Odo was at his side. He went with the Norman army and, as well as leading the prayers for victory, he fought in the battle. He carried a mace rather than a sword, because although men of the church were not allowed to spill blood, they were permitted to batter their opponents with a club.

Odo was made Earl of Kent and often ruled England when William was in Normandy. He was given great areas of land and he granted some of these areas to his knights. The tapestry may have been made in England to record the Norman victory and the part Odo played in it. The tapestry was later hung in his cathedral at Bayeux.

By 1082 William and Odo had fallen out. Odo was sent to prison in Rouen, and only released shortly before William died. He returned to England and plotted against William Rufus, the Conqueror’s son, but was captured and banished to Bayeux. He died in Sicily in 1097 on a crusade to the Holy Land.

Stigand

Archbishop of Canterbury

He is shown on the Tapestry playing a prominent position at Harold’s coronation. Because his appointment as Archbishop was disputed by the Pope, this may have been a Norman attempt to discredit Harold’s kingship.

- The Women -

Only three women are shown on the main narrative of the Tapestry

Edith

This figure must be Edith, wife of Edward the Confessor and sister of King Harold. The author of the Life of Edward, written soon after his death, records that she was present at Edward’s deathbed when he commended her to Harold’s protection. Edith appears in: The King is Dead… (scene 1)

Fleeing woman

This woman is shown either trapped inside or fleeing from a burning building at Hastings when William’s troops were harrying the area. The fleeing woman appears in: Beachhead (scene 3)

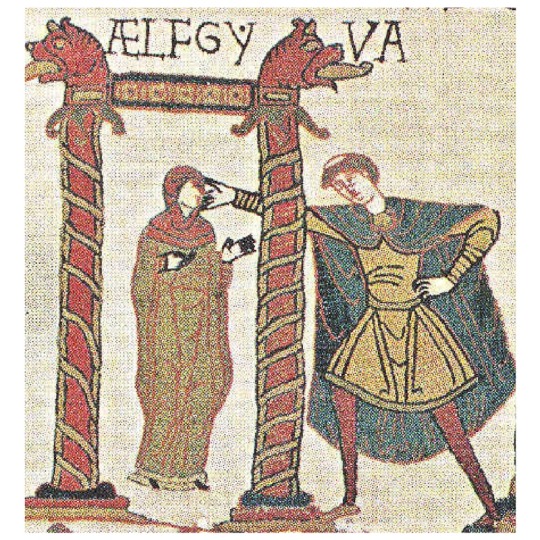

Aelfgyva

The meaning of this scene is obscure but it must refer to a well known event to be in such a prominent position. Aelfgyva was a widely used Saxon name. The mysterious lady appears in: The Mysterious Lady (scene 1)

What Happened After Hastings

After the Battle of Hastings, William still had to conquer England. He marched from Hastings, crossing the Thames at Wallingford, and then on towards London. At Berkhamsted he received the surrender of the city. William took hostages to ensure that the surrender was kept.

William wanted to be crowned King as soon as possible. His coronation took place on Christmas Day, 1066. It was held at Westminster Abbey, which had been built by Edward the Confessor. During the Coronation, as the people inside the Abbey shouted out their acceptance of William, the troops outside thought a fight had broken out. Fearing that William had been attacked, they began to set fire to Saxon houses. As the Norman soldiers could not understand the language of the Saxons, and the Saxons could not understand the language of the Normans, it was difficult for them to communicate.

William kept the promises he had made to the barons who fought with him to give them English land. He gave them lands taken from the Saxons. In exchange, the barons had to be loyal to William and provide knights to fight for him when he needed them. They might also have to pay sums of money to the king. William made sure that the barons could not easily rise against him by giving them pieces of land in different parts of the country, which made it difficult to raise a private army in secret.

In their turn the barons granted land to their followers. The knights promised in return to be loyal to the barons, to fight for them when needed and to raise money when the barons demanded it.

The peasants had to work the land for the knights at certain times of the year, and pay the knights in produce which kept the knights’ families supplied with food. Peasants were not usually allowed to leave their own villages. Every person owed his or her living to the people who had allowed them their land and was paid in service, money or goods. It was called the FEUDAL SYSTEM, and was the basis of society in the early middle ages.

William also gave lands to the Church because the Pope had supported William in his claim to the English throne. One of the first promises William kept was to build an abbey to celebrate his victory. He chose the site of the Battle of Hastings and the abbey became known as Battle Abbey. It is said that the high altar was built at the place where King Harold lost his life.

William wanted to raise money in his new kingdom, so he made the Saxons pay taxes. In 1086 he ordered a survey and his men went all over the country writing down exactly what everyone owned in land, cattle, crops and tools so that he knew exactly how much people could pay. When all the information had been collected, it was written down and is known as the Domesday Book.

Life gradually returned to normal. Ordinary people lived in wooden buildings and these gradually rotted away, so that we cannot see exactly what they looked like. However, the barons wanted more permanent buildings than the hastily built timber castles put up soon after the Battle of Hastings. Soon castles, churches, cathedrals, abbeys and monasteries were being built in stone. Some of the stone was brought across from Caen in France. The Normans brought their own style of building and decorating with them too. Some of their castles and cathedrals took a very long time to build, but we can still see many of them today. The style of the building at that time is called ROMANESQUE.

We should remember that William the Conqueror was not only King of England, he also ruled Normandy and he spent a lot of time there. Barons and knights in England spoke French for many years, and most writing was in Latin or French. The ordinary people spoke in their own Saxon language, and the Chroniclers continued to write in it until the reign of William’s grandson Henry II.

- The Norman Succession -

William of Normandy became King of England in 1066. He died in Rouen in 1087, and was buried at Caen. He left four children: Robert, William, Henry and Adela.

The eldest, Duke Robert, ruled in Normandy and his second son William became King William II of England, known as Rufus because of his red complexion. Rufus was not a popular king. He was killed by an arrow in 1100 when hunting in the New Forest and he may have been murdered. Rufus did not marry and had no children to succeed him. His brother Henry took the throne, but Robert of Normandy also claimed it. Eventually Henry imprisoned Robert who died in Cardiff Castle.

Henry I had two legitimate children, a son and a daughter. His son was drowned on the White Ship while crossing the English Channel. Possibly the loss of this son moved Henry to found the Abbey at Reading. When Henry died in 1135 he was buried in Reading, before the high altar of his abbey.

Henry had named his daughter Matilda, who was married to Geoffrey Plantagenet of Anjou, as his successor and the barons had sworn that they would accept her as sovereign. On Henry’s death, Stephen, son of William the Conqueror’s daughter Adela, seized the throne and from 1139 until 1153 civil war raged in England. In 1153 the Treaty of Wallingford established that Stephen would become king but Matilda’s son Henry would succeed him on his death. Stephen died a year later and Henry took the throne as Henry II, the first of fourteen Plantagenet Kings.

http://www.bayeuxtapestry.org.uk

Very interesting..thank you😊❤️❤️❤️❤️

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ROCHESTER CASTLE:

ROCHESTER Castle, located in Kent, England, was first constructed shortly after 1066 CE by the Normans, was converted into stone between 1087 and 1089 CE, and then added to over subsequent centuries, notably between 1127 and 1136 CE, and again in the mid-14th century CE.

The imposing castle keep or donjon seen today was added in the 12th century CE and is one of the best-preserved and tallest of any medieval castle. Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE), was a famous resident as well as the bishops of Rochester. In 1215 CE Rochester was the scene of a major siege by King John of England (r. 1199-1216 CE) when rebel barons temporarily took over the castle. Today the site is managed by English Heritage and is an important surviving example of 12th-century CE castle architecture.

Read More

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

Explore Every Stitch of the Famed Bayeux Tapestry Online

https://sciencespies.com/history/explore-every-stitch-of-the-famed-bayeux-tapestry-online/

Explore Every Stitch of the Famed Bayeux Tapestry Online

Since the Bayeux Tapestry’s rediscovery in the 18th century, scholars have painstakingly cataloged the 224-foot-long embroidered cloth’s contents. Today, they know that the medieval masterpiece features 626 humans, 37 buildings (including the Mont-Saint-Michel monastery), 41 ships, and 202 horses and mules, among many other objects.

Thanks to a newly debuted, high-resolution version of the tapestry created by the Bayeux Museum in Normandy, France, anyone with an internet connection can now follow in these researchers’ footsteps, reports the Associated Press (AP).

Though the work is widely known as a tapestry, it technically counts as a work of embroidery. Popular myth holds that Queen Matilda of England and her ladies-in-waiting embroidered the sweeping tableaux, but historians don’t actually know who created it, per the Bayeux Museum’s website.

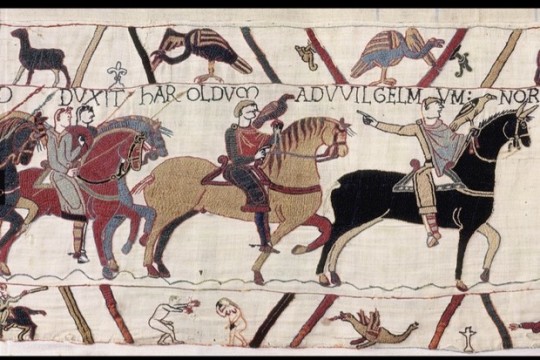

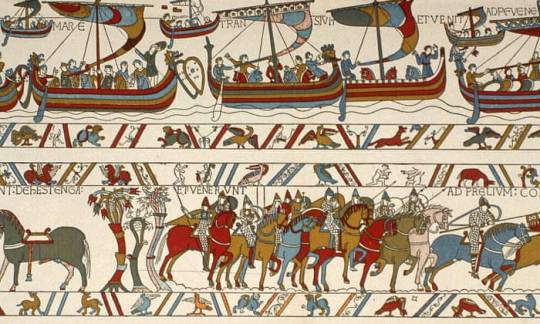

In 75 chronological episodes, each titled with a Latin phrase, the tapestry depicts the struggle for power between William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold Godwinson, England’s last Anglo-Saxon king. The scenes concludes with William’s successful invasion of England in 1066, which earned him the nickname “William the Conqueror.” According to the museum, the illustrations depict William in a favorable light and would have served as a record of events—as well as propaganda—for the successful ruler.

As art historian Kristine Tanton writes for Khan Academy, the tapestry’s scenes are arranged in three horizontal zones, with the main events in the middle. The upper and lower zones depict husbandry, hunting and scenes from Aesop’s Fables that relate to the central action.

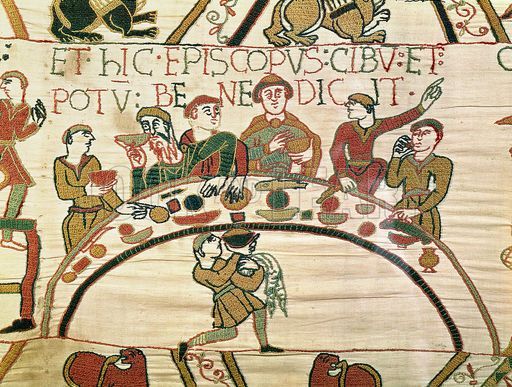

A group of Norman soldiers hold their first meal in England after arriving. In the center, Bishop Odo gazes at the viewer while blessing a cup in his hand.

(Bayeux Museum)

Harold, center, was crowned king of England in January 1066. He died in battle against William in October of that same year. The Bayeux Tapestry depicts Harold dying of an arrow through the eye—a symbol of divine fate.

(Bayeux Museum)

Panel 32 features the first known depiction of Halley’s Comet and the text “These men marvel at the star.”

(Bayeux Museum)

Throughout, Tanton notes, the “embroiderers’ attention to specific details provides important sources for scenes of [11th]-century life as well as objects that no longer survive.”

Scenes of a banquet, for instance, give historians crucial information about Norman dining practices, while battle scenes illuminate the types of military equipment and armor that soldiers would have worn in the 11th century.

The artisans who created the tapestry used ten colors of dyed wool thread and four types of embroidery stitches. In the high-resolution online version, viewers can zoom in on areas that have faded or grown discolored over the years. Interestingly, notes Cailey Rizzo for Travel + Leisure, the tapestry’s 19th-century restorations have faded more than the original colors and are now “almost … white.” As the AP reports, the tapestry’s curators plan to undertake a major renovation in 2024 aimed at fixing the wear and tear in the work’s weave.

Odo de Conteville, bishop of Bayeux and William the Conqueror’s half-brother, likely commissioned the work around 1070, either to decorate his home or to hang in the nave of the newly constructed cathedral of Notre-Dame of Bayeux. The tapestry was rediscovered by scholars in 1729 and has hung in a dedicated museum in Normandy since 1983.

“Such narrative hangings, occasionally put on display for all the faithful to see, were not just intended to decorate churches,” the museum notes on its website.

Instead, the museum adds, tapestries such as these “told stories that the people of the time, the majority illiterate, could follow. As with the Bayeux Tapestry, they could become a piece of propaganda for a victorious conquest.”

#History

2 notes

·

View notes