#often narratives will take to naming a prisoner's crime to define their personality

Text

one thing that still Gets Me abt andor is that it never tried to ask the question if the prisoners are Guilty Or Not, if they Deserve to Be There or Not, which is the pitfalls for So Many stories which frame the Reason the prisoners are in prison as some kind of excuse to justify them being incarcerated in the first place. the prisoners are not defined by the crimes they did or did not do, it's never brought up and is never relevant.

andor is not interested in Any Of That. It never tries to get Cassian to ask Why someone is in prison and if they """"""deserve"""""" to be there. The bottom line is prisons are unjust and unpaid labour systems and the incarcerated are the victims here, not aggressors to society. which is a really refreshing take to see, for the show very unapologetically condemns the prison system for what it is: a means of systemic abuse and exploitation of labour.

#andor#andor spoilers#andor 1.09#often narratives will take to naming a prisoner's crime to define their personality#not ONCE does andor try to do that#the only interaction we get on this is 'what are u in for?' 'i didn't do Anything' 'been a lot of that 'round here lately'#and thats IT that's really it. the empire would put ppl in prison regardless of what they do#humans are cheaper than droids and easier to replace#it will never matter what they did to be put into prison. as long as the prison exists in the first place.#me.txt

803 notes

·

View notes

Text

ANIME & MANGA I HAVE BINGED IN THE LAST MONTH: May 2021

I've Been Hunting Slimes for the Past 300 Years and Now Ive Maxed Out My Level: incredibly long name aside, cute af slice of life that suffers Same Face Syndrome. I'm still happy to watch it because of how feel good and fluffy it is though, Im probably gonna forget about it in two or three years tho. 8/10.

Don't Toy With Me, Miss Nagatoro: I found out this was a webcomic first and suddenly all the HORNINESS made so much more sense. A Femdom, Degradation, Humiliation, Dacryphilia Bullies to Lovers story disguised as a high school rom-com which, I'm not going to lie, misses SKEEVY CITY by mere inches on a regular basis. However, I'm a Dom/Switch and this entire relationship sets off my dom brain center like New York City just shy of midnight. So if you're into that sort of scene, this anime is for you. If not, it's still fascinating but you're probably gonna be a little put off by how mean the Girl!Bully is to the guy MC. Unless you find out something about yourself, in which case, congrats! Stay safe, sane, consensual, and learn about the traffic light system on top of safe words, I promise you'll have a better life in general after that. Still Ongoing, currently 10/10.

Fruits Basket: IM GONNA CRY I LOVE THIS ANIME SO MUCH???? The original anime came out when I was in... I think middle school and my parents were really strict on what I watched so I never got to experience the first wave and I never bothered to watch the show ever after I moved out of the house years later. However, now that I'm much older I honestly can say this is one of my favorite anime to date, and all the characters are charming, lovable, with their own problems that I can connect to or sympathize with, and I love the MC which is always a treat tbh. Except Akito. Akito can suck a sandpaper dick. I'm only on S2 tho so no spoilers! Anime 11/10.

Monster Girl Doctor: went in thinking it was gonna be a monster girl who's a doctor with a homoerotic assistant (her name is SAPPHY okay sue me for thinking it) and ended up watching the entire dubbed harem series. Honestly, I've seen worse and this one has consistent follow-through on interesting characters and backstory enough for me to shove aside the blatant under-monstrousness of the female monsters and the harem-ness of everything else. Dubbing is honestly really good, which is a treat, and the monster designs are not the worst and the MC is tolerable. Honestly, I don't mind having watched it! The mix of cgi and the traditional animation together work pretty strangely though, and it often doesn't flow super well. 7.5/10

So I'm a Spider, So What: Dubbed version which honestly isn't that bad. Took me a bit to get into it, but after realizing that it's got a mismatched timeline a la The Witcher, it made so much more sense. Heavily done in cgi, and you can definitely tell between the 2D and 3D animations, but not the worst in the world. I went in not expecting much but it ended up being an Issekai I can stand and even enjoy. On god has a decent story... with the spider. I'd be a liar if I didnt say I skipped some of the human parts just to get back to the best part of the show. 8/10.

Somali and the Forest Spirit: I'm so fucking nostalgic for this thing it makes me want to go and hug my dad. About a human girl under threat of being eaten with a monster-dominated world. Very obvious "humans fear what they don't understand" message but instead of the humans learning tolerance it's what happens when they get annihilated first so like, kudos for the mangaka for having the guts to do that. I cried like a baby regularly. It's really good, I watched the dub and ID WATCH IT AGAIN!!! 9/10.

To Your Eternity: Oh my god. O h my g o d. Fell in love on the first episode, ngl. About if an immortal being learned how to be a person from scratch. I love it. HOWEVER. Keep a box of tissues on you at all times because you're gonna need them. I'm only on EP7 because that's all that's out right now but just know. I love it. Not for everyone but certainly for my "what do we define as human and the human condition" ass. 12/10.

Those Snow White Notes: A sports anime without any sports. About shamisen playing which is cool because I never realized how cool this instrument was??? Its neat af. OP1&2 are by Burnout Syndrom so know theyre fire. Gonna be real, its pretty alright, but not extraordinary. You can tell they were using the characters as archetypes rather than actually characters which kinda kills a lot of the emotional value you could've had, but I'm still gonna watch it. It doesn't make me cringe as hard as other sports anime tho so I consider it toptier in that regards but if you're a big sports anime fan you might be bummed out by it. Every single musical performance is INCREDIBLE tho. A solid 8/10.

Toilet Bound Hanako-kun: THE ART OMFG IT'S SO GORGEOUS. Listen, if you took coptic markers and gave them an animation budget with some manga panel direction thrown in there, that's this anime. It's beautiful. Gorgeous. I'm in love with the aesthetic every second. Story? Really good. Characters? I love the MC and his evil little twin brother asshat. Demons? Not super imaginative but I'm carrying on happy as can be anyways. Dubbing? A bit shaky at times but I found the voices charming if a little off for some of them. I'm already waiting for the second season with popcorn at the ready. 10/10.

Prison School: I watched this directly after Hanako-kun and it was like I got slapped in the face by sweaty unwashed titties and some fedora wearing schmuck's piss kink. No character is likable or redeemable. I finished it, but at what cost? 2/10 and only because a character shit his pants and I laughed.

Sleepy Princess in the Demon Castle: watched this right after Prison School and it was NECESSARY tbh. Its so CUTE and honestly, im not even kidding you, the fucking funniest anime I've seen in months. I watched the dub and the VAs are having the time of their lives working on this anime not just giving it their all but literally just going ham. Its great. If I read this im sure id be bored outta my mind but the VAs giving it a joyous performance make it an insta fave for me tbh. 9/10.

Sk8 the Infinity: i watched the dub with my bro and I can confirm that its a spectacular show because we both loved it and we have vastly different tastes. Incredibly SUSPENSFUL AND STRESSFUL for an anime about skateboarding but we finished it in a single sitting tbh. The last episode is not dubbed for some reason but we still loved it. Like if Free! was less obnoxious but the only fan-service here is Joe ♡ a beefcake who owns my lesbian heart. I think there's exactly one named female character tho and I legit couldn't tell you what it was if there was a gun to my head. So, over all, 9.5/10.

That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime: I'm going to be entirely honest, I went in thinking it was going to be a boring isekai of no value. I was right about the Isekai part. It was honestly pretty interesting and focused on nation building like you're playing civilization rather than the usual "Get Stronger" narrative or "Get Some Pussy" narrative most isekais take which is delightfully refreshing. Granted there are flavors of that in this which means it doesn't alienate the big isekai watchers out there, but it's not the whole dish and it doesn't make me want to cringe the same way others do. You've got a slime MC just vibing and building a nation of monsters nbd. Does lose points for making the female monsters more humanoid than their male counterparts but makes them back by only doing perfunctory fan-service and nothing that makes me want to cry... except the butt sumo episode but in fairness it was all a terrible dream. Literally, the MC refuses to dream anymore after that. solid animation, decent voice acting, decent story, made me realize how HUGE this is in the Light Novel community???? There's like 18 fucking novels and that's WILD. 8.5/10.

MANGA:

Spirit Photographer Saburo Kono: a one shot special by the mangaka of The Promised Neverland! Honestly a really delicate touch of both super creepy and really touching, and I'm not gonna lie I'm bummed that this isn't a bigger project but the single chapter makes it a good taste for their style. I've been wondering if I wanna read/watch The Promised Neverland and now I think I will. 10/10

Deranged Detective Ron Kamonohashi: from the mangaka of Hitman Reborn comes this Sherlock and Watson derivative! Not even 20 chapters out yet with a sort of spotty schedule, I honestly love it even thought it's exactly as you expect. HOWEVER. Kamonohashi the "Sherlock" character uses mental pressure to kill all confirmed murderers and it's up to Toto the "Watson" character to save all those people before Kamonohashi kills them! It's just recently introduced a "Moriarty" family of crime lords (not a big spoiler don't worry it was obvious) so the tension surrounding Ron's past is amping up rn. Personally, I think the art is GORGEOUS, the characters engaging, and the story quick enough to keep my interest. Most mysteries are solved within a chapter or two so you're not stuck 20 chapters into one locked room mystery which is just peachy tbh. RN, 10/10. If this gets an anime, I anticipate a legion of fangirls who ship the two main characters along with their many friends. I've been alive too long to believe otherwise.

Don't Toy with Me, Miss Nagatoro: Yeah I read the manga after I watched the show. A slower build than the anime, but it works for the format, if theyd done the same with the show then I don't think it wouldve done as well. Honestly? Cuter tbh but just as horny. You dont start really LEARNING about your character until like, chap 65 tho and no real "drama" happens until like 75. A good chunk of the chapters are like 8pgs so its a breeze to get through. I love these slow burn idiots of the century. 9.5/10 because you can DEFINITELY tell the mangaka does hentai too.

Yugen's All-Ghouls Homeroom: one-shot by the mangaka for Food Wars, it's no wonder there's this constant perviness from the MC, a guy who can see and exorcise spirits. Takes place at an all girl's finishing school with KICK ASS monsters tbh, kinda bummed its not longer. The MC? Blatant monsterfucker who is also a CONFRIMED monsterfucker???? Idk i vibe with that single emotion. Everything else is hit or miss. 7/10 for monsters and cool concept, lost points for the MC very pointedly being okay with admitting he'd wait for the teenagers to be adults tho. Creepy af. Could live without that.

Hell's Paradise: I finished the entire 127chps in 3 days and I was really enthusiastic about it 90% of the time thinking about how deep it was and then I actually thought about it and I ended up being very neutral about the whole thing tbh. The art is fantastic tho, but DEFINITELY deserving of the M rating. Tits. Tits everywhere. But not tits to be ecchi over, no, monster hermit tits on beautiful women-ish figures. Now generally I give that a pass but a huge theme in the story is that men and women are "no better than one or the other" but like, lady tits are what you see 99% of the time. Men tits are few and far between. I call bullshit on most of the "deep" themes is what I'm saying, so it's like the mangaka was trying for those deep thoughts but missed the margin a little too far for my preference. That being said, the MC is a married man who loves his wife which automatically makes him my favorite character so like... idk so many good things, so many misses, but overall really spectacular themes and imagery. Unique but classic all at once. It's getting an anime and I have NO IDEA how much censorship they're gonna be doing but they're going to be doing SO MUCH. Oh yeah, and one guy is a plant/human hybrid who fucks a 1000 year old plant-hermit which makes him a canon monster fucker. And one canon non-binary character who I, a nonbinary, actually like. So like... gosh I've got mixed feelings. 8.5/10.

Choujin X: From Sui Ishida, mangaka to the mega hit Tokyo Ghoul comes this brand new manga!... Of one chapter, lol. Not really binge-y because it's just the one chapter out right now but I'm already keeping my eye on it. The grasp on anatomy in the art is PHENOMENAL and you can see Ishida flexing his art skill which is great. Can't give a true rating but I'm giving it a tentative 9/10 because I'm excited to see more.

Shag&Scoob: technically not a manga, its an ongoing webcomic I binged an subscribed to in one day and I just think it deserves more attention. Starts off funny with "what if Scooby Doo had a gun" and has been led to "what if all cartoons are aliens that survive and receive their powers by the humans that love them in an epic war with Martians." On god, its good. I finished the current series in a couple hours so it's a breezy read, highly recommend it. 9/10.

To Your Eternity: Yeah I watched the anime and then finished all current 143 chapters in like 3 days. GOD IM WEAK. I don't buy physical manga unless I know I want to remember the story forever and I'm already budgeting for the current books out. Yeah, this is a good series. That being said, definitely not for the faint of heart or those who suffer under common triggers like suicide, molestation, death, etc. It's all framed as bad and necessary to the story don't get me wrong, but it's there and has lasting affects on the characters. Incredible story telling by the creator of A Silent Voice. Keep tissues nearby at all times. 12/10.

#i've been killing slimes for 300 years and maxed out my level#don't toy with me miss nagatoro#spirit photographer saburo kono#fruits basket#deranged detective ron kamonohashi#yugen's all-ghoul's homeroom#monster girl doctor#so i'm a spider so what#somali and the forest spirit#to your eternity#jigokuraku#hell's paradise#choujin x#shag and scoob#toilet bound hanako kun#prison school#sk8 the infinity#that time i got reincarnated as a slime

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

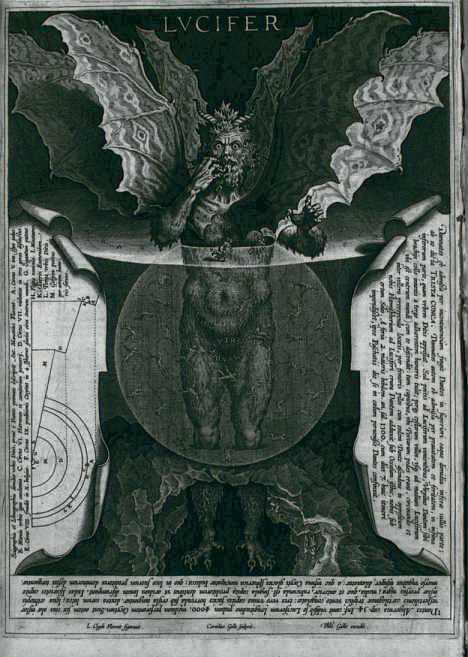

Psycho Analysis: Lucifer/Satan

(WARNING! This analysis contains SPOILERS!)

Please allow me to introduce this villain. He’s a man of wealth and taste...

Satan, or Lucifer, or whatever of the hundreds of names across multiple religions, folk tales, urban legends, movies, books, songs, video games, and more that you choose to call him, is without a doubt the biggest bad of them all. He is not just a villain; he is the villain, the bad guy your other bad guys answer to, the lord of Hell. If there’s a bad deed, he’s done it, if there’s a problem, he’s behind it. There’s nothing beneath him, and that’s not just because he’s at the very bottom of Hell. He is the root cause of all the misery in the entire world.

And if we’re talking about Satan, we gotta talk about Lucifer too. They weren’t always supposed to be one and the same, but over centuries of artistic depictions and reimaginings they’ve been conflated into one being, a being that is a lot more layered and interesting than just a simple adversary for the good to overcome when handled properly.

Motivation/Goals: Look, it’s Satan. His main goal is to be as evil as possible, do bad things, cause mischief and mayhem. Rarely does anything good come from Satan being around. If he is one and the same as Lucifer, expect there to be some sort of plot about him rebelling against God, as according to modern interpretations Lucifer fought against God in battle and was then cast out, falling from grace like lightning. When the Lucifer persona is front and center, raging against the heavens tends to be a big part of his schemes, but when the big red devil persona is out and about, expect temptations to sin, birthing the Antichrist, or tempting people to sell their souls.

Performance: Satan has been portrayed by far too many people over the years to even consider keeping count of, though some notable performances of the character or at least characters who are clearly meant to be Satan include the nuanced anti-villain take of the character Viggo Mortensen portrayed in The Prophecy; the sympathetic homosexual man portrayed by Trey Parker in South Park and its film; the hard-rocking badass Dave Grohl portrayed in Tencaious D’s movie; Robin Hughes as a sneaky, double-crossing bastard in “The Howling Man” episode of The Twilight Zone; the big red devil from Legend known as Darkness, played by Tim Curry; the shapeshifting angel named Satan from The Adventures of Mark Train who will make you crap your pants; and while not portrayed by anyone due to being entirely voiceless, Chernabog from Disney’s Fantasia is definitely noteworthy in regards to cinematic depictions of the devil.

Final Thoughts & Score: Satan is a villain whose sheer scope dwarfs almost every other villain in history. It’s not even remotely close, either; Satan pops up in stories all around the world, is the greater-scope villain of most varieties of three major religions, and his very name is shorthand for “really, really evil.” Every other villain I have ever discussed and reviewed wishes they could be a byword for being bad to the bone. Even Dracula, one of the single most important villains in fiction, looks puny in comparison to Satans villainous accomplishments.

Satan in old religious texts tended to be an utterly horrifying force of nature, until Medieval times began portray him as a dopey demon trying to tempt the faithful (and failing). Folklore and media have gone back and forth, portraying both in equal measure – you have the desperate, fiddle-playing devil from “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” and the unseen, unfathomable Satan who may or may not exist in the Marvel comics universe who other demons live in fear of the return of. Satan is just a very interesting and malleable antagonist, one who is defined just enough that he can make a massive, formidable force while still being enough of a blank slate that you can project any sort of personality traits onto him to build an intriguing foe.

One of the most famous examples of this in action is the common depiction of Satan as the king of hell. This doesn’t really have much basis in religion; he’s as much a prisoner as anyone else, though considering how impressive a prisoner he is, he’d be like the big guy at the top of the pecking order in any jail for sure. But still, the idea of Satan as the ruler of hell was clearly conceived by someone and proved such an intriguing concept that so many decided to run with it.

I think that’s what truly makes Satan such an interesting villain, in that he’s almost a community-built antagonist. People over the ages have added so much lore, personality, and power to him that is only vaguely alluded to in old religions to the point where they have all become commonplace in depictions of the big guy, and there really isn’t any other villain to have quite this magnitude on culture as a whole. It shouldn’t be any shock that Satan is an 11/10; rating him any lower would be a heinous crime only he is capable of.

But see, the true sign of how amazing he is is the sheer number of ways one can interpret him. You have versions that are just vague embodiments of all that is bad and unholy, such as Chernabog from Fantasia, you have more nuanced portrayals like the one Viggo Mortensen played in The Prophecy, you have outright sympathetic ones like the one from South Park… Satan is just a villain who can be reshaped and reworked as a creator sees fit and molded into something that fits the narrative they want. I guess what I’m trying to say is that not only is Lucifer/Satan one of the greatest villains of all, he’s also one of the single greatest characters of all time.

Now, there are far too many depictions of Satan for me to have seen them all, but I have seen quite a lot. Here’s how Old Scratch has fared over the millennia in media of various forms, though keep in mind this is by no means a comprehensive or exhaustive lsit:

“The Devil Went Down to Georgia” Devil:

I think this is one of my favorite devils in any fiction ever, simply because of what a good sport he is. Like, there is really no denying that Johnny’s stupid little fiddle ditty about chickens or whatever sucks major ass, and yet Satan (who had moments before summoned up demonic hordes to rip out some Doom-esque metal for the contest) gave him the win and the golden fiddle. What a gracious guy! He’s a 9/10 for sure, though I still wish we knew how his rematch ended…

Chernabog:

Chernabog technically doesn’t do anything evil, and he never says a word, and yet everything about him is framed as inherently sinister. It’s really no wonder Chernabog has become one of the most famous and beloved parts of Fantasia alongside Yen Sid and Sorcerer Mickey; he’s infinitely memorable, and really, how can he not be? He’s the devil in a Disney film, not played for laughs and instead made as nightmarishly terrifying as an ancient demon god should be. Everything about him oozes style, and every movement and gesture begets a personality that goes beyond words. Chernabog doesn’t need to speak to tell you that he is evil incarnate; you just know, on sight, that he is up to no good.

Quite frankly, the implications of Chernabog’s existence in the Disney canon are rather terrifying. Is he the one Maleficent called upon for power? Is he the one all the villains answer to? Do you think Frollo saw him after God smote him? And what exactly did he gain by attacking Sora at the end of Kingdom Hearts? All I know for sure is that Chernabog is a 10/10.

Lucifer (The Prophecy):

Viggo Mortensen has limited screentime, but in that time he manages to be incredibly creepy, misanthropic… and yet, also, on the side of good. Of course, he’s doing it entirely for self-serving reasons (he wants humanity around so he can make them suffer), but credit where credit is due. The man manages to steal a scene from under Christopher Walken, I think that’s worth a 10/10.

Satan (South Park):

Portraying Satan as a sympathetic gay man was a pretty bold choice, and while he certainly does fall into some stereotypes, he’s not really painted as bad or morally wrong for being gay, and ends up more often than not being a good (if sometimes misguided) guy who just wants to live his life. Plus he gets a pretty sweet villain song, though technically it’s more of an “I want” song than anything. Ah well, a solid 8/10 for him is good.

Satan (Tenacious D):

youtube

It’s Dave Grohl as Satan competing in a rock-off against JB and KG. Literally everything about this is perfect, even if he’s only in the one scene. 10/10 for sure.

Robot Devil:

Futurama’s take on the devil is pretty hilarious and hammy, but then Futurama was always pretty on point. He’s a solid 8/10, because much like South Park’s devil he gets a fun little villain song with a guest apearance by the Beastie Boys, not to mention his numerous scams like when he stole Fry’s hands. He’s just a fun, hilarious asshole.

The Howling Man:

The Twilight Zone has many iconic episodes, and this one is absolutely one of them. While the devil is the big twist, that scene of him transforming as he walks between the pillars is absolutely iconic, and was even used by real-life villain Kevin Spacey in the big reveal of The Usual Suspects. This one is a 9/10 for sure, especially given the ending that implies this will all happen again (as per usual with the show).

The Darkness:

While he’s more devil-adjacent than anything and is more likely to be the son of Satan rather than the actual man himself, it’s hard not to give a shout-out to the big, buff demon played by Tim Curry in some of the most fantastic prosthetics and makeup you will ever see. He gets a 9/10 for the design alone, the facty he’s Tim Curry is icing on the cake.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

#5yrsago Greenwald's "No Place to Hide": a compelling, vital narrative about official criminality

Cory Doctorow reviews Glenn Greenwald's long-awaited No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State. More than a summary of the Snowden leaks, it's a compelling narrative that puts the most explosive revelations about official criminality into vital context.

Glenn Greenwald's long-awaited No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State is more than a summary of the Snowden leaks: it's a compelling narrative that puts the most explosive revelations about official criminality into vital context.

No Place has something for everyone. It opens like a spy-thriller as Greenwald takes us through his adventures establishing contact with Snowden and flying out to meet him -- thanks to the technological savvy and tireless efforts of Laura Poitras, and those opening chapters are real you-are-there nailbiters as we get the inside story on the play between Poitras and Greenwald, Snowden, the Guardian, Bart Gellman and the Washington Post.

Greenwald offers us some insight into Snowden's character, which has been something of a cipher until now, as the spy sought to keep the spotlight on the story instead of the person. This turns out to have been a very canny move, as it has made it difficult for NSA apologists to muddy the waters with personal smears about Snowden and his life. But the character Greenwald introduces us to isn't a lurking embarrassment -- rather, he's a quick-witted, well-spoken, technologically masterful idealist. Exactly the kind of person you'd hope he'd be, more or less: someone with principles and smarts, and the ability to articulate a coherent and ultimately unassailable argument about surveillance and privacy. The world Snowden wants isn't one that's totally free of spying: it's one of well-defined laws, backed by an effective set of checks and balances ensure that spies are servants to democracy, and not the other way around. The spies have acted as if the law allows them to do just about anything to anyone. Snowden insists that if they want that law, they have to ask for it -- announce their intentions, get Congress on side, get a law passed and follow it. Making it up as you go along and lying to Congress and the public doesn't make freedom safe, because freedom starts with the state and its agents following their own rules.

From here, Greenwald shifts gears, diving into the substance of the leaks. There have been other leakers and whistleblowers before Snowden, but no story about leaks has stayed alive in the public's imagination and on the front page for as long as the Snowden files; in part that's thanks to a canny release strategy that has put out stories that follow a dramatic arc. Sometimes, the press will publish a leak just in time to reveal that the last round of NSA and government denials were lies. Sometimes, they'll be a you-ain't-seen-nothing-yet topper for the last round of stories. Whether deliberate or accidental, the order of publication has finally managed to give the mass-spying story that's been around since Mark Klein's 2005 bombshell.

But for all that, the leaks haven't been coherent. Even if you follow them closely -- as I do -- it's sometimes hard to figure out what, exactly, we have learned about the NSA. In part, that's because so much of the NSA's "collect-it-all" strategy involves overlapping ways of getting the same data (often for the purposes of a plausibly deniable parallel construction) so you hear about a new leak and can't figure out how it differs from the last one.

No Place's middle act is a very welcome and well-executed framing of all the leaks to date (some new ones were revealed in the book), putting them in a logical, rather than dramatic or chronological, order. If you can't figure out what the deal is with NSA spying, this section will put you straight, with brief, clear, non-technical explanations that anyone can follow.

The final third is where Greenwald really puts himself back into the story -- specifically, he discusses how the establishment press reacted to his reporting of the story. He characterizes himself as a long-time thorn in the journalistic establishment's side, a gadfly who relentlessly picked at the press's cowardice and laziness. So when famous journalists started dismissing his work as mere "blogging" and called for him to be arrested for reporting on the Snowden story, he wasn't surprised.

But what could have been an unseemly score-settling rebuttal to his critics quickly becomes something more significant: a comprehensive critique of the press's financialization as media empires swelled to the size of defense contractors or oil companies. Once these companies became the establishment, and their star journalists likewise became millionaire plutocrats whose children went to the same private schools as the politicians they were meant to be holding to account, they became tame handmaidens to the state and its worst excesses.

The Klein NSA surveillance story broke in 2005 and quickly sank, having made a ripple not much larger than that of Janet Jackson's wardrobe malfunction or the business of Obama's birth certificate. For nearly a decade, the evidence of breathtaking, lawless, endless surveillance has mounted, without any real pushback from the press. There has been no urgency to this story, despite its obvious gravity, no banner headlines that read ONE YEAR IN, THE CRIMES GO ON. The story -- the government spies on your merest social interaction in a way that would freak you the fuck out if you thought about it for ten seconds -- has become wonkish and complicated, buried in silly arguments about whether "metadata collection" is spying, about the fine parsing of Keith Alexander's denials, and, always, in Soviet-style scaremongering about the terrorists lurking within.

Greenwald doesn't blame the press for creating this situation, but he does place responsibility for allowing it square in their laps. He may linger a little over the personal sleights he's received at the hands of establishment journalists, but it's hard to fault him for wanting to point out that calling yourself a journalist and then asking to have another journalist put in prison for reporting on a massive criminal conspiracy undertaken at the highest level of government makes you a colossal asshole.

The book ends with a beautiful, barn-burning coda in which Greenwald sets out his case for a free society as being free from surveillance. It reads like the transcript of a particularly memorable speech -- an "I have a dream" speech; a "Blood, sweat, toil and tears" speech. It's the kind of speech I could have imagined a young senator named Barack Obama delivering in 2006, back when he had a colorable claim to being someone with a shred of respect for the Constitution and the rule of law. It's a speech I hope to hear Greenwald deliver himself someday.

No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State

https://boingboing.net/2014/05/28/greenwalds-no-place-to-hid.html

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Gilmore has come to understand that there are certain narratives people cling to that are not only false but that allow for policy positions aimed at minor or misdirected—rather than fundamental and meaningful—reforms. Gilmore takes apart these narratives: that a significant number of people are in prison for nonviolent drug convictions; that prison is a modified continuation of slavery, and, by extension, that most everyone in prison is black; and, as she explained in Chicago, that corporate profit motive is the primary engine of incarceration.

For Gilmore, and for a growing number of scholars and activists, the idea that prisons are filled with nonviolent offenders is particularly problematic. Less than one in five nationally are in prisons or jail for drug offenses, but this notion proliferated in the wake of the overwhelming popularity of Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow,” which focuses on the devastating effects of the war on drugs, cases that are primarily handled by the (relatively small) federal prison system. It’s easy to feel outrage about draconian laws that punish nonviolent drug offenders, and about racial bias, each of which Alexander catalogs in a riveting and persuasive manner. But a majority of people in state and federal prisons have been convicted of what are defined as violent offenses, which can include everything from possession of a gun to murder. This statistical reality can be uncomfortable for some people, but instead of grappling with it, many focus on the “relatively innocent,” as Gilmore calls them, the addicts or the falsely accused—never mind that they can only ever represent a small percentage of those in prison. When I asked Michelle Alexander about this, she responded: “I think the failure of some academics like myself to squarely respond to the question of violence in our work has created a situation in which it almost seems like we’re approving of mass incarceration for violent people. Those of us who are committed to ending the system of mass criminalization have to begin talking more about violence. Not only the harm it causes, but the fact that building more cages will never solve it.”

But in the United States, it’s difficult for people to talk about prison without assuming there is a population that must stay there. “When people are looking for the relative innocence line,” Gilmore told me, “in order to show how sad it is that the relatively innocent are being subjected to the forces of state-organized violence as though they were criminals, they are missing something that they could see. It isn’t that hard. They could be asking whether people who have been criminalized should be subjected to the forces of organized violence. They could ask if we need organized violence.”

Another widely held misconception Gilmore points to is that prison is majority black. Not only is it a false and harmful stereotype to overassociate black people with prison, she argues, but by not acknowledging racial demographics and how they shift from one state to another, and over time, the scope and crisis of mass incarceration can’t be fully comprehended. In terms of racial demographics, black people are the population most affected by mass incarceration—roughly 33 percent of those in prison are black, while only 12 percent of the United States population is—but Latinos still make up 23 percent of the prison population and white people 30 percent, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. (Gilmore has heard people argue that drug laws will change because the opioid epidemic hurts rural whites, a myth that drives her crazy. “People say, ‘God knows they’re not going to lock up white people,’ ” she told me, “and it’s like, Yes, they do lock up white people.”) Once you believe prisons are predominately black, it’s also easier to believe that prisons are a conspiracy to re-enslave black people—a narrative, Gilmore acknowledges, that offers two crucial truths: that the struggles and suffering of black people are central to the story of mass incarceration, and that prison, like slavery, is a human rights catastrophe. But prison as a modern version of Jim Crow mostly serves to allow people to worry about a population they might otherwise ignore. “The guilty are worthy of being ignored, and yet mass incarceration is so phenomenal that people are trying to find a way to care about those who are guilty of crimes. So, in order to care about them, they have to have some category to which they become worthy of worry. And the category is slavery.”

A person who eventually either steals something or assaults someone goes to prison, where he is offered no job training, no redress of his own traumas and issues, no rehabilitation. “The reality of prison, and of black suffering, is just as harrowing as the myth of slave labor,” Gilmore says. “Why do we need that misconception to see the horror of it?” Slaves were compelled to work in order to make profits for plantation owners. The business of slavery was cotton, sugar and rice. Prison, Gilmore notes, is a government institution. It is not a business and does not function on a profit motive. This may seem technical, but the technical distinction matters, because you can’t resist prisons by arguing against slavery if prisons don’t engage in slavery. The activist and researcher James Kilgore, himself formerly incarcerated, has said, “The overwhelming problem for people inside prison is not that their labor is super exploited; it’s that they’re being warehoused with very little to do and not being given any kind of programs or resources that enable them to succeed once they do get out of prison.”

The National Employment Law Project estimates that about 70 million people have a record of arrest or conviction, which often makes employment difficult. Many end up in the informal economy, which has been absorbing a huge share of labor over the last 20 years. “Gardener, home health care, sweatshops, you name it,” Gilmore told me. “These people have a place in the economy, but they have no control over that place.” She continued: “The key point here, about half of the work force, is to think not only about the enormity of the problem, but the enormity of the possibilities! That so many people could benefit from being organized into solid formations, could make certain kinds of demands, on the people who pay their wages, on the communities where they live. On the schools their children go to. This is part of what abolitionist thinking should lead us to.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Secret of Evil

I’d been sitting on this concept for a while, and then I found myself relaxing on Youtube one night, watching a film reviewer’s analyses — and I was jolted from my comfortable mood and into a flurry of expository frothing.

Possible content warning for talk about cults, general acts of violence, the dark side of humanity, cops, abuse — you get the idea.

Now, I think Ryan Hollinger does a great job of analysing this giving the constraints of his expertise and knowledge. I generally love his channel, and would recommend it. However, the underlying concept of this movie bothered me so greatly that, well — here we are.

youtube

What is evil?

For our purposes, “evil” refers to socially unacceptable, transgressive acts that cause harm to others. Examples include violent acts, sexual assault, murder, theft, fraud, lying — you get it.

Now, as long as humanity has been living in groups, squatting near our little fires, we’ve quarreled and bickered and occasionally wronged or harmed each other — sometimes, more severely than at others. The call to understand both our own dark impulses and bad decisions and to understand those taken by others appears to be pretty universal. Narratives and folkloric tales about evil, good, punishment, and morality appear in every single human civilization and culture, from small subsistence clans and tribes to our modern era.

I have a strong interest in cults, extremist groups, new religious movements, and that kind of thing. I’ve always wondered how “evil” came to be. It was a while before I understood that evil is a verb, not an actual force in the world.

But writers — especially in Hollywood, but in the general creative sphere as well — don’t all have degrees in the human condition. And while that’s fine, what is not fine is the way that evil is portrayed and continues to be portrayed. Not to mention the fact that criminality is often portrayed as “evil,” regardless of whether or not the criminal actions harmed anyone (i.e. an expired license plate vs a speeding ticket vs an assault charge).

Now, fun, lighter-hearted portrayals of evil aren’t really the issue here — I’m talking more about the serious portrayals, where a movie or story is really trying to Say Something. The silly portrayals of things, however, are rooted in the more serious stuff — so let’s talk about what we see as evil.

There’s no such thing as “born evil”

Take a minute with it. If you already know that, and are going, “yeah, duh,” then let me explain the whole “evil” thing in the context of murderers. I’m so tired of these bad, stupid true crime narratives about someone who just “wakes up and does bad things”. They allow us to ignore the massive preponderance of people who a) commit crimes for survival purposes, b) the misunderstandings of how mental health issues and neurodivergence works (i.e. “evil autistic” etcetera), and c) socio-economic factors, not to mention d) the cycle of abuse. That’s not even including e) cultural dehumanization of others caused by privilege — such as with wealth, perceived moral authority, or racist or gender-based ideas, to name but a few.

Let me run through those again with examples. Now, I’m not saying these are actually all “causes of evil,” but they’re various examples of causes of harmful acts, that some people might label — fairly or unfairly — as evil. Some of these groups and people are especially vulnerable to maltreatment, and especially innocent of what they’re accused of, but culturally, we don’t usually act like that’s the case.

a) survival criminality — doing something bad for either good reasons or personal safety. Example: stealing a TV to pay for a child’s school fees; stealing to pay for drugs in the case of an addiction

b) mental health issues and neurodivergence — people who experience impaired empathy and/or struggle to conform to societal cultural norms. Example: an autistic child slapping a caregiver during a meltdown, because they feel angry and/or threatened.

c) socio-economic factors — poverty is often criminalised, and some people — in Canada, that includes Indigenous, Metis, and First Nations people, and Black, African, and Caribbean Canadians in particular — are disproportionately accused of and suspected of crimes. This can lead to being forced into the prison system, loss of opportunities, prejudice, and murder. If you’ve heard the phrase “school to prison pipeline” regarding the way Black people are treated, you’ll know what I’m talking about. (If you don’t, look it up; it’s very important. Also horrifying.) Example: a store manager points at a Black child for acting “suspicious,” assuming the child has stolen a candy bar. (Depending on the portrayal, either the child will be implied to be “evil” or the store owner will be “evil”.)

d) the cycle of abuse. Abuse survivors who don’t deal with their experiences in some way go on to abuse others. Example: a man who is assaulted by his uncle may later go on to assault his daughter’s friend in her teen years. Alternately, an abused child may go on to abuse her spouse in adulthood.

e) cultural dehumanization of others caused by privilege — such as with wealth, perceived moral authority, or racist or gender-based ideas, to name but a few. The trope of the Evil Rich Executive from the 80s is a good example. See also, President of the US #45 for abundant and horrifying examples of dehumanizing and abusing others.

Does evil even exist?

I mean, colloquially, sure. As a primeval force? No. Even companies that profit from true crime content will, with some bashfulness, admit that a significant majority of the “terrifying killers” they love to portray are just severely abused people who’ve ended up lashing out in the worst possible ways. In the exceptionally rare cases where multiple murderers aren’t actually abused in childhood and/or suffering severe adverse effects, there’s often neurological damage involved.

However, as you can see from this brief analysis, it’s pretty clear that evil is more of a verb than a state of being. Someone’s actions can be evil, but defining a person as “evil” assigns a certain kind of evaluation that is both dehumanizing and oddly absolving. I won’t dive into the depths of Christian theology about evil right now — but even in games like Dungeons and Dragons, confronting the question of “evil races” (yikes) has required some updates and changes. And frankly, that’s a good thing.

How do we write about bad things and evil, then?

Don’t take this essay as the vituperative howling of an inveterate killjoy. Rather, it’s a plea for authors to realise that the old stories we’ve been telling are not only dusty and boring from overuse, they’re deeply inaccurate. The real world’s cues are so much more interesting and fertile, and trying to tell the same old mortality tales that have already been explored — without adding to them — is both artistically annoying and actually pretty harmful.

All of these things can still make for incredible, nuanced, interesting, gripping stories…but NoOoooooo, Hollywood still loves, “but what if just pure evil?” At this point, the thought experiment side of it is no longer a good argument. It’s become the predominant understanding of how crime, especially murderers, work — and that’s really, really bad.

We learn about the world from the narratives we take in — whether that’s pursuing true crime tales late into the night or listening to harrowing tales of social justice and fights against societal forces, or even just watching a fun, dumb horror movie. Luckily, there’s a lot of wonderful work that’s been coming out that does take these nuanced, complicated stories into account — to list some podcasts I love, How We Roll, Dungeons and Randomness, Campaign: Skyjacks, The Adventure Zone, and Critical Role all tend to feature plenty of nuance in the “evil” characters, as well as in the “good” ones.

So ask yourself — who are the heroes in this tale, and in the world? Who do you instinctively take the side of when you see a real-world conflict? Although we all pride ourselves on being able to tell the differences between facts and fiction, our construction of the world comes from stories — and that means we have to be honest about who we label “the bad guys,” and why.

***

Michelle Browne is a sci fi/fantasy writer and editor. She lives in Lethbridge, AB with her partner-in-crime and their cats. Her days revolve around freelance editing, knitting, jewelry, and learning too much. She is currently working on other people’s manuscripts, the next books in her series, and drinking as much tea as humanly possible.

0 notes

Text

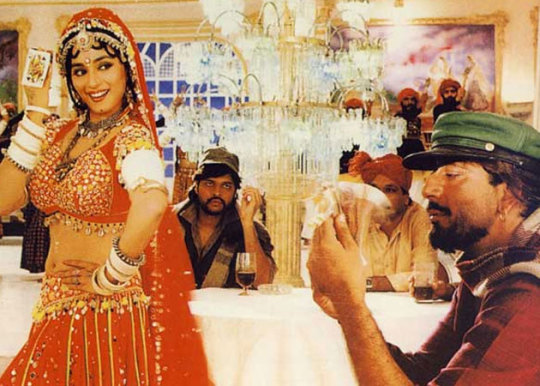

“Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”: Bollywood's Scandalous Question, and The Hardest-Working Scene in Movies by Genevieve Valentine

In a nightclub with the mood lighting of a surgical theater, a village belle is crying out for a husband. Her friend Champa encourages and chastises her by turns; her male audience is invited to be the bells on her anklets. (She promises, with a flare of derision, that serving her will make him a king.) Her costume, the color of a three-alarm fire, sparkles as she holds center screen. The song and camerawork builds to a frenzy as if unable to contain her energy; the dance floor’s nearly chaos by the time she ducks out—she alone has been holding the last eight minutes together. And the hardened criminal in the audience follows, determined not to let her get away.

Subhash Ghai’s 1993 blockbuster Khalnayak is a “masala film,” mingling genre elements with Shakespearean glee and a healthy sense of the surreal. By turns it’s a crime story, a separated-in-youth drama, a Gothic romance with a troubled antihero, a family tragedy, a Western with a good sheriff fighting for the rule of law, and a melodrama in which every revelation’s accompanied by thunder and several close-ups in quick succession. (There’s also a bumbling police officer, in case you felt something was lacking.) It was a box-office smash. But the reason it’s a legend is “Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”—“What's Behind That Blouse?”— an iconic number that’s one of the hardest-working scenes in cinema.

youtube

See, Ganga (Madhuri Dixit) isn’t really a dancer for hire. She’s a cop gone undercover to snag criminal mastermind Ballu (Sanjay Dutt), who’s recently escaped from prison and humiliated her boyfriend, policeman Ram (Jackie Shroff). Ballu, undercover to avoid detection, is trying to avoid trouble on the way to Singapore...but of course, everything changes after Ganga.

Though the scene shows its age—the self-conscious black-bar blocking, the less-than-precise background dancers—it’s an impressive achievement. Firstly, it’s a starmaker: the screen presence of Madhuri Dixit seems hard to overstate. By 1993 she was already a marquee name, and she would dominate Bollywood box office for a decade after, both as a vivid actress and as a dancer whose quality of movement was without peer. But if you’d never seen a frame of Bollywood you’d still recognize her mountain-climb in this number—playing the cop who disdains Ballu playing the dancer trying to court him, performing by turns for the room and to the camera, conveying flirty sexuality without tipping into self-parody, and all on the move for kinetic camera shots ten to fifteen seconds at a time. Dixit’s effortless magnetism holds it fast; the camera loves what it loves.

But this is more than just a career-making dance break; “Choli Ke Peeche” is the film’s cinematic and thematic centerpiece. Khalnayak is about performativeness. Ballu performs villainy (sometimes literally) in the hopes it will fulfill him; Ram vocally asserts the role of virtuous cop to define himself against those he prosecutes. As Ballu performs good deeds—saving a village from thugs, ditching his bad-guy cape for sublimely 1993 blazers—his conscience grows back by degrees. As Ganga performs a moral compass for Ballu, her heart begins to soften. And at intervals, crowds deliver praise or censure, reminding us that all the world’s a stage. (It’s in the smallest details: While on the run, Ballu’s ready to kill a constable until it turns out he’s an extra in the movie shooting down the street.)

And nowhere in cinema is the fourth wall more permeable than a musical number. Bollywood’s turned them into an art. Playback singers are well-known (they even have their own awards categories), a layer of meta in every performance. Diegetic dance numbers are common. Movies often halt the action entirely for an item number, as a guest actress drops by. For the length of a song, the suspension of disbelief the rest of a movie requires is on pause.

Musical numbers are a place where a movie can comment on itself, and Khalnayak takes full advantage of the remove. (In an earlier number with more traditional Hollywood framing, Dixit winks at us while singing to her beloved.) Likewise, Saroj Khan’s choreography in “Choli Ke Peeche” invites us to enjoy Ganga’s sexuality without concern about racy lyrics—or even about the villain, who dances in his chair along with the rest of us. With the camera as chaperone, it’s safe for “Ganga” to asks what else she’s meant to do but lift her skirts a bit as she walks (that skirt's expensive!), and to let her prince know she sleeps with the door open. The men around her are either part of the act, or an audience safely contained by the narrative and the frame for our benefit. (At times, her back is to her audience so she can dance for the camera; Khalnayak knows we’re watching.) “Choli Ke Peeche” is a thesis statement on the relationship between performance and audience.

It’s a moment powerful enough to cast a shadow across the rest of the film. This number, not the crimes or the cops, is what the movie returns to repeatedly; it’s too good to ignore and too subversive to solve. Not least, among the other layers of performance, is queer subtext. In Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures, Gayatri Gopinath points out that “female homoerotic desire between Dixit and [Neena] Gupta is routed and made intelligible through a triangulated relation to the male hero.” Champa’s masculinized within the performance; she asks the loaded title question, addresses our heroine’s male savior, and discusses him with Ganga. It’s a significant connection between women in a song supposedly directed at a man—which might be why Champa is the one who defends Ganga’s reputation by explaining the dance-hall sting, and reminding the audience it was all for show.

But that’s not going to stop “Choli Ke Peeche.” At the end of the second act, Ballu blows Ganga’s cover. (He’s known she’s a cop since their backstage meeting—another layer of performance). To prove they mean no real harm, the men don lenghas and veils and parody a chunk of the number, right down to interjectional close-ups and a wandering camera that brings kinetic energy to the static space.

youtube

In one way this reprise tries to undercut the song’s power by making it faintly ridiculous, suggesting it isn’t really sexual—it’s camp. But if “Choli Ke Peeche” functioned as a ���safe’ way for Ganga to express sexuality when we first saw it, it serves a parallel purpose here. Despite the mocking undertones, with this number the men are reassuring her; they understand her sexuality was itself just a performance—her purity is therefore safe with them. (We know that’s a concern here because her shawl is pulled close about her; the free-spirit act is over, and her virtue is at stake.)

But there’s also something undeniably subversive in hyper-masculine, violent figures reenacting coy expressions of feminine desire. To prevent things from getting too subversive, Ballu invades Ganga’s personal space, a reminder of his power amid the making fun. And the performance ends in the threat of violence against Ganga when she breaks the spell—the expected order of captor and captive reestablishing itself as the film falls into a formulaic last act, an attempt to wrest social order out of the exuberant chaos one musical number has wrought.

It caused some chaos offscreen, too. When the soundtrack was released ahead of the film, “Choli Ke Peeche” was deemed obscene; the song was banned on Doordarshan and All India Radio, and faced legal challenge at the Central Board of Film Certification. In “What is Behind Film Censorship? The Kahlnayak debates,” Monika Mehta writes that “the visual and verbal representation combined to produce female sexual desire. It was the articulation of this desire that was the problem—it posited that women were not only sexual objects, but also sexual subjects.” And within the number, there’s no doubt Ganga’s in control; she sends alluring glances Ballu’s way, mocks (then takes) his money, and signals he’s free to follow her if he dares. The undercover-cop framework gives these gestures the veneer of respectability, but since Ballu doesn’t know that yet, the frisson of the forbidden remains.

Letters of condemnation and support rolled in. Many claimed the song was too suggestive; an exhibitor from Paras Cinema in Rajasthan wrote in favor because “Choli Ke Peeche” was based on a folk song from the area, and “If it was vulgar then the ladies would have never liked it.” The examining committee eventually ruled in favor of letting the number remain, with some edits: one that removed the chorus entirely (which Ghai successfully appealed), and two cuts to beats considered provocative, including one of Ganga ‘pointing at her breast’ as she sings, “I can’t bear being an ascetic, so what should I do?”, unequivocally claiming sexuality without even a man as her object. No wonder it had to go.

It wasn’t the only controversy dogging the film; star Sanjay Dutt was arrested under The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Act for possible connections to the 1993 Bombay bombings, which added an uncomfortable self-awareness to Ballu’s onscreen misdeeds. Yet those controversies did Khalnayak no harm at the box office, where it broke records, and the movie’s had such nostalgic power that as of 2016, Ghai was considering a sequel.

But “Choli Ke Peeche” remains the movie’s most measurable influence. In Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, Rosie Thomas notes that after Ganga, “distinctions between heroine and vamp began to crumble, as the item number became de rigueur for female stars,” suggesting Khalnayak was a harbinger of less rigid strictures for Bollywood’s leading ladies. Another legacy of Khalnayak: more numbers feature women—with a man as the absent locus of their affections—dancing with each other instead, forming their own narrative connections and opening the opportunity for queer readings. (One of the most famous, “Dola Re Dola” from 2002’s Devdas, features Dixit again, alongside costar Aishwarya Rai.)

The pressure of so much cultural influence and metatextual weight might have turned a lesser scene into a relic, a stuttery car chase from a silent movie that starts a montage of the ways the camera has developed. It’s a testament to “Choli Ke Peeche” that it absorbs the weight of the years as gracefully as it does. If you want a watershed moment for sexual agency in Bollywood, you have it. If you want a starmaker with dancing that’s influenced choreography and direction for twenty years since, it’s happy to help. If you want a scene that dissects the idea of performance as subversive act, the offscreen vulgarity scandal only adds to your case. And if you want a musical number that reminds you what cinema can do, “Choli Ke Peeche” is as vibrant, campy, and complex as ever.

#bollywood#choli ke peeche#khalnayak#sanjay dutt#subhash ghai#masala film#all india radio#oscilloscope laboratories#musings#indian cinema#cinema of india#ganga#devdas#aishwarya rai#madhuri dixit#doordashan

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Piccarella, Charles Manson Was a Republican, The New Inquiry (August 5, 2019)

Long incorrectly associated in the public mind with the political left, Manson wasn’t merely conservative; he might as well have been a Fed

THE first time you see him, you barely notice him. He’s posing for a group photo, poking his head over the shoulders of two people you recognize. You have to see his face a few times before you begin to recognize him too, but soon enough you do. He’s showing up everywhere now, at a party with Sky Ferreira, in front of a media wall at a film festival with James Franco, on the beach with Justin Bieber. He’s slight and messy, but his face tattoo and rattail are distinctive enough to brand him somewhere between Jersey Shore and inzane_johnny. When you see him in one of Kanye’s selfies, you scroll through the comments looking for his name. A few of the commenters mention a Chad. You Google “kanye+chad” until you find a verified Instagram account with 100,000 followers. The bio reads “LOVExHATE // LIFExDEATH // ALLxONE,” and the handle is @ChadMansonOfficial.

You start following Chad on all social-media platforms. He often likes and occasionally reposts articles about himself; Vice develops a beat. Along with the rest of the world, you slowly get to know Chad and his singular lifestyle brand, part edgelord, part corporate woke. The elitist one percent has destroyed the planet and defrauded the people, and the only way to cope is to lean into whatever means to liberation remain. He’s nonmonogamous, advocates for entheogens and their potential to treat PTSD, and vehemently distrusts both political parties. Your friends tend to shrug off the rumors about his entourage of younger women and their creepy orgies. You’re not sure if you buy his message, but media personalities of various stripes have found something to like about him, from Tucker Carlson to Cum Town. Then the Fader runs the headline “Chad Manson at work on debut mixtape produced by Kanye West.” You wonder when the first single will drop, but it never does.

Instead, one morning, you wake up to a stream of push notifications. At a party at Franco’s house in Hollywood, along with at least six other industry personalities, actress Margot Robbie—no, Kate Bosworth—no, wait, Hilary Duff—has been hideously murdered by still unidentified perpetrators. Not quickly enough, police apprehend Chad Manson. Early reports suggest that Manson has been plotting against the cultural elite for years, coaxing stars like Ed Sheeran, Lil Xan, and the FuckJerry guy into his orbit. After a long investigation, detectives determine that Manson orchestrated the murders after hearing Kanye’s album Yeezus, reading its lyrics as coded messages from a powerful representative of the Black community about the coming armed battle against the white race.

AUGUST 9, 2019, will mark the 50th anniversary of the Tate-LaBianca murders, better known as the Manson Family Murders, which took place in the early hours of the morning on August 9, 1969. In honor of the occasion, at least four new movies (Mary Harron’s feminist revision Charlie Says, Quentin Tarantino’s pop-historical epic Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, the more straightforward biopic Tate, and the pure exploitation The Haunting of Sharon Tate) and a new season of the Netflix series Mindhunter will dramatize the events in some way this year. Whether these projects are motivated by revisionism or nostalgia is unclear.

The most famous piece of writing about the Manson Family—besides, maybe, Helter Skelter, the true-crime account by Manson’s prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi—is Joan Didion’s essay “The White Album,” now considered a classic of cultural journalism. In the essay, Didion writes, “Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.” This declaration can be interpreted any number of ways, but in the decades since its writing it has been reduced to a single, simple notion: The Manson Murders were somehow specific to, revealed something about, and effectively concluded “the Sixties,” whatever that was. They broke a tension and fulfilled a paranoia we associate with a historical moment defined, loosely, by “countercultural” behavior and activity. This has become the dominant narrative of the murders.

After Manson died in November of 2017, a flurry of thinkpieces appeared, most of which hardened this impression. “At the time,” the Atlantic reported, “Manson was seen as emblematic of the counterculture, living on a hippie commune with his followers, writing music, and dropping acid.” An op-ed in the Guardian alluded to “the widespread belief within the late 60s counterculture that he was innocent, a martyr who had been picked on by police as part of The Man’s war against the long-hairs.” On the right, the likes of Ben Shapiro and Kevin D. Williamson saw an opportunity, exaggerating and fabricating sympathies between Manson and leftist radicals and, in more than one case, Barack Obama. Articles in Vice and the New York Times compared Manson (more accurately) to the alt-right, but the prevailing interpretation is not exactly a collective misremembering. Reviewing Helter Skelter in 1975, the New Republic wrote, “It is hard to escape the conclusion that the Counterculture of the 1960s—which offered us beautiful music, new ways to live our lives, and the will to end the war—gave birth as well to Charles Manson.”

Hard nothing. Hardly anyone seems to want to try. But it’s not the growing leftist movement that’s rehabilitating Manson. That credit goes to the alt-right, Netflix, and Quentin Tarantino. If the ’60s counterculture was a failed attempt to take down the U.S. government, the Manson Murders were a failed attempt to accelerate its racist program. The boomers and Generation X were content, even happy, to remember the ’60s univocally as a freewheeling adventure against the Man, including Manson, but the evidence is thin.

The most enduring connections between Manson and radical leftists were drawn by Bugliosi, a prosecutor, who had no ear for hippie irony and no understanding of the culture’s contradictions. In a chapter of Helter Skelter listing assessments of Manson from the left, he offers, “The underground paper Tuesday’s Child, which called itself the voice of the Yippies, blasted its competitor the Los Angeles Free Press for giving too much publicity to Manson—then spread his picture across the entire front page with a banner naming him MAN OF THE YEAR.” The endorsement is more likely a reference to the publicity Bugliosi credits the paper with admonishing. After an anecdote about Yippie party founder Jerry Rubin visiting Manson in prison, Bugliosi admits, “Yet Charles Manson—revolutionary martyr—was a difficult image to maintain. Rubin admitted to being angered by Manson’s ‘incredible male chauvinism.’ A reporter for the Free Press was startled to find Manson both anti-Jewish and anti-Black. And when one interviewer tried to suggest that Manson was as much a political prisoner as Huey Newton, Charlie, perplexed, asked, ‘Who’s he?’”

Bugliosi’s most unfortunate contribution to this argument is this quote from Bernardine Dohrn, delivered at an SDS summit not long after the murders: “Offing those rich pigs with their own forks and knives, and then eating a meal in the same room, far out! The Weathermen dig Charles Manson.” This is the quote that no right-wing publication can seem to leave alone. But Bill Ayers, placing the quote back in the context of the speech for which he was present, refutes any ideas of its sincere support for Manson. The occasion and the subject of the speech was the recent death of Black Panther Fred Hampton, which the Weathermen assumed, not unreasonably, to be part of a racist government conspiracy curiously Mansonian in design. The comparison to Manson was meant to lament the media’s focus on the sexier story of the Tate-LaBianca murders rather than what to the Weathermen was the much greater and more politically significant crime. “This is what screams for our attention and our response,” Ayers remembers Dohrn continuing. “And what do we find in our newspapers? A sick fascination with a story that has it all: a racist psycho, a killer cult, and a chorus line of Hollywood bodies. Dig it!” It was simple sarcasm.

Dohrn’s juxtaposition of Manson and Hampton echoes in Didion’s juxtaposition in “The White Album” of Manson and the story of Black Panthers leader Huey Newton’s arrest for the murder of Oakland police officer John Frey. Both cases came about because of a deliberate police effort to target the Black Panthers. The New Republic review explains that “Helter-skelter was Charles Manson’s design for Armageddon: by committing crimes like the Tate-LaBianca murders and leaving clues to throw the blame on black power groups, Manson hoped to force a police crackdown on the blacks who would retaliate with war against the whites.” If “a police crackdown on the blacks” was the first phase of Manson’s plan for race war, then the FBI was already years ahead of him.

ANY examination of the Manson murders is incomplete if it ignores the U.S. government’s concurrent efforts to attack and undermine Black-power groups via espionage and violence, efforts made public in 1971 after the FBI’s papers documenting its counterintelligence programs were stolen and leaked to the press. After hearing The White Album, Manson directed his followers to murder Sharon Tate and her friends to try to frame the Black Panthers and incite a race war. At the time, we now know, police were seeking out the Panthers as part of a coordinated COINTELPRO effort, part of its aim being to demonize the Panthers as dangerous subversives with a threatening anti-white agenda. The main difference between Manson’s murderous efforts to provoke the Panthers and the FBI’s was scope. They were engaged in the same strategy and similar tactics.

Across five COINTELPRO programs, the FBI’s goals were broad but consistent: to suppress action by radical groups. The FBI wanted to neutralize any challenge to the prevailing order, of which white supremacy was (and remains) an inextricable part. One of the five COINTELPRO programs targeted white hate groups, but its documentation suggests that these groups only posed a threat to the FBI because their vigilantism threatened to subvert the government’s authority. Coordination between the different COINTELPRO programs to incite internecine struggle was also common enough in practice that the FBI might have infiltrated groups like the KKK to incorporate them into their operations against groups like the Panthers. The FBI workshopped so many plots against the Panthers that some of them probably sounded a lot like Manson’s.

The fantasy of white genocide that animated Manson permeates the highest levels of state power in this country. Manson may have been deluded enough to believe the Beatles knew who he was and cared enough about him to write him songs, but his racism wasn’t born of unique paranoia. Growing up in America in the middle of the 20th century, he could have picked it up pretty much anywhere. As is true of all white terrorists, what set Manson apart from other agents of white supremacy was not his hatred but his belief in his own personal importance.

The year 1988 was significant for white supremacists, many of whom use the number 88 as a symbol meaning “HH,” or “Heil Hitler.” Schreck and Rice both performed at an 8/8/88 concert that summer.All this notwithstanding, Manson’s direct connections to right-wing ideologues are not so easy to find. The best sources are in a document called The Manson File, published most recently by Feral House, an underground press with a record of publishing white supremacists, and an accompanying film called Charles Manson Superstar. The Manson File is a fanzine-style hodgepodge of drawings, photographs, and writings about and by Manson collected in 1988 by a group of Manson sympathizers including historically dubious experimental musicians Nikolas Schreck and Boyd Rice.* The file includes text by racialist extremist and Universal Order founder James N. Mason, whose name is so similar to Manson’s that even their fans occasionally mix them up. The equally choppy film includes a brief yet almost unwatchable interview with Mason, preceding a longer one with Manson.

Mason’s contributions to both productions are very hard to follow, both because they are extremely disturbing and because they make very little sense. Mason seems to refer to a years-long relationship between his Universal Order and the Manson Family, lasting at least into the ’80s, during which time the two groups discussed plans for race-based warfare on an ongoing basis. The book and the film both reproduce an image of the Universal Order’s official logo, a set of scales with a swastika imposed over the center. The logo was designed by Manson. A few years after the release of both documents, Mason’s collected writings were published, edited by Michael Moynihan, coauthor of popular Feral House title Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground, recently adapted as a major motion picture that erases its white-supremacist origins. Mason’s writings have since been rediscovered and adopted by Atomwaffen Division, the neo-Nazi terrorist group whose targeted guerilla efforts to assault and supplant the existing social order continue as of this writing.

These are Charles Manson’s friends and fans: murderous fanatics, deranged occultists, addled hipster racists, and conspiracy theorists of the QAnon variety. In a word, Nazis. They read his words and follow his lead and hide in plain sight with the government’s blessing as long as they don’t get in the way. Sure, Manson hung out with Dennis Wilson and Neil Young, but only to manipulate them. He definitely never hung out with Bernardine Dohrn. He’s not your dad’s distant friend who took too much acid and went off the deep end; he’s at once less and more familiar than that. He’s the estranged cofounder of the giant media outlet that laid you off. He runs a YouTube music-review channel you’ve been watching for years. Actually, he has a solo show opening next week at a gallery in LA. Check your calendar. You’re invited.

#charles manson#politics#conservatism#public image#murder#crime#analogy#murder groupies#culture#killer fandom#fandom#subcultures#tate-la bianca murders#manson family

0 notes

Link

Jasper Bernes | July 10th 2019 | Commune

In the poems of Eisen-Martin, the violent truth of the racialized city, and an address to the forms of collective life that might survive it.

Heaven Is All Goodbyes

Tongo Eisen-Martin

City Lights | $15.95 | 136 pages

Tongo Eisen-Martin is the principal author, in conjunction with comrades in the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, of a curriculum — “We Charge Genocide Again!” — that sets out to contextualize and organize against the extrajudicial police killing of black people. It situates extrajudicial murder in the broader historical and political context of “the maintenance of hegemonic power in the United States,” and defines it as a feature of US class structure, which in turn comprises interlocking modes of organized violence. One central claim of the text is that the ongoing practice of violence requires that extrajudicial murder seem not only justifiable but also logical, intrinsic to social function and reproduction. Disrupting that logic is one intervention a properly political poetry might make. Eisen-Martin’s collection Heaven Is All Goodbyes can serve as an example of what such poetry might look like.

Political poetry in this sense does not tell us how to vote or how to live, but instead makes us uncomfortably aware of the discrepancy between our desires and attachments — our investments and commitments — and the institutionalized avenues available for their satisfaction and realization. Such poetry may make us question whether voting, for example, is the best avenue through which to achieve substantive freedom. The contrasting term to “political poetry” here is not “mainstream” but “middle class” poetry, referring less to a class than an affective orientation toward the existing order. Such poetry resolves the apparent contradiction between quotidian pleasures and desires, on one hand, and the alienating, calculative logic of the unliving and unlivable, on the other, through the facile solidarities of interpersonal recognition, reinforcements of the common sense, and appeals to individual morality or sympathy. For all their crafted semblance of immediacy, middle-class lyrics typically present as universal normative experiences that reflect and reinforce the genocidal cultural logic Eisen-Martin’s curriculum outlines. Clichéd sentiments implicitly provide cover for quotidian violence, or personalize and depoliticize it, all the while evacuating everything messy and singular about subjectivity.

To my mind, this collection’s mode of political engagement reveals the ultimate intellectual and political bankruptcy of perennial debates surrounding the so-called “avant-garde.” As Fredric Jameson argued regarding the more fundamental “high”/“mass” culture binary, avant-garde and middle-class poetry are inseparably twin: they mutually reinforce forms of aesthetic production that correspond to historically specific moments in the development of capitalism. The issue is not that middle-class lyrics — often mischaracterized as “workshop poetry,” which in turn stands in for the shifting class, racial, and institutional dynamics surrounding poetry’s production — do not accord with readers’ experiences, but that their prestige forms too rarely offer a vision of desirable forms of life. The strength of Eisen-Martin’s work generally, and this collection in particular, is the glimpses it offers readers not only of the ways social life and organization exist, but the ways we might desire it otherwise.

Heaven Is All Goodbyes addresses itself to readers uncomfortable with poetry understood as a celebration of the paper-thin solidarities and small gestures of a shared morality, the celebration of survival that does not ask what makes life difficult. Yet, from its dedication — “Like 50 familiar postures in the dark . . . Run here. We will save your life” — its solution is not sloganeering through seemingly transparent expression. Neither the speaker nor addressee of the imperative “run here” is given; the collective “we” is hard-won rather than assumed as the outcome of readily obvious historical predicates and antagonisms. Forms of salvation are fraught and uncertain — the collection’s title itself is a caution against certain narratives or “familiar postures” of redemption. Read as a poem, which its presentation invites, it serves as an apt preparation for the strategies of the collection: assertive and advanced (not hindered) by implicit skepticism toward the given. Its discourse is terse but not obtuse, direct but withholding. Read as a private message it works in roughly similar ways.

From the first poem, “Faceless,” the collection blends flat assertion — “Warehouse jobs are for communists” — with an indirection and will to discrepancy that abuts surrealism: “But now more corridor and hallway have walked into our lives. Now the whistling is less playful and the barbed wire is overcrowded too.” The ironic reversal that has corridor and hallway walking, rather than walked through, initially appears playful. The next sentence undercuts play through metonymy insofar as “barbed wire” figures prison. Corridor and hallway apparently refer to passageways between defined spaces, indoors or outdoors, figuratively connecting the unthought spaces of incarceration and the nominally free. The next lines read:

My dear, if it is not a city, it is a prison.

If it has a prison, it is a prison. Not a city