#only for people to mostly like artwork from bigger more established artists

Text

Dobson's Patreon: An Addendum to His Monument of Sins

(The following is a submission from @soyouareandrewdobson, meant to be an addendum to the multi-post submission @ripsinfest made a while back. Ironically, this one also had issues when being submitted, so I’ll be copypasting it here with all the images and links originally intended.)

In 2018, user @ripsinfest wrote a multipart series of posts for THOAD, recounting Dobson’s attempt to establish a patreon in 2015 and how it resulted in failure on a massive scale, to the point that his patreon is arguably “a monument to all his sins”.

Personally I think the post series is extremely well researched, rather “neutral” in terms of tone (letting the posts provided as evidence speak more for themselves than the opinion of the writer) and gives a detailed but quick rundown on what went wrong. Primarily that Dobson overestimated his own “value” as an artist and did NOT attempt to give his few supporters what they wanted through his artwork posted around the time.

I do however want to use the opportunity to also point out at certain obvious things that in my opinion (and likely the opinions of others) added to the failure of the patreon account, that were not accounted for in detail and are primarily related to how the internet perceives popularity and Dobson’s inability to understand, how to “sell” and make himself look good to the public.

To begin with, let’s just point out a certain truth about making money via Patreon: To do so, depends a lot on your popularity as a content creator online. That is simply because the more popular you are, the bigger your fanbase is and as such the more likely a certain percentage of people may be willing to donate money to you and your work in hopes they get something out of it, even if it is just the altruistic feeling of having helped someone they “like”. It doesn’t take a genius to see, how e.g. internet reviewers such as Linkara or moviebob (around 2800 and 4400$ earnings via patreon each month respectively) can make quite some money, while other, more obscure content creator or artists barely make money to go by, earning essentially pocket money at best.

In addition, popularity is fleeting. A few years ago e.g. internet personality Noah Antweiler aka The SpoonyOne managed to earn 5000$ a month via patreon, just shortly after establishing his account. But his lack of content over the years AND his toxic behavior online resulted in a decline of popularity and with it people jumping off his Patreon. As such, Antweiler only earns nowadays around 290$ a month via Patreon and most of that money is likely form people who have forgotten they donate to him in the first place anyway.

And Noah is not the only one who over the course of the last couple of years lost earnings. Brianna Wu makes barely more than he does, despite having once been the “darling” of the internet when the Gamergate controversy was at its peak. Many Bronies who once made more than 2k via video reviews on a show about little horses at the peak of its popularity (2013-15) earn less than 300-800 on average nowadays because interest on the show as well as people talking about it has declined.

Heck, in preparation of writing this piece I found out, that one of the highest grossing patreons nowadays is “The last podcast on the left”, a podcast that earns more than 67k a month by making recordings on obscure and macabre subjects on a regular basis.

So there you have it folks: As the interests of the internet users change, so does the popularity of certain people online and -in case they have a patreon account or similar plattforms- their chances of making money via their content.

Which now brings us back to Dobson, who was not popular at all at that particular time and managed to become even less popular as the months and years passed by.

Sure, Dobson had his fans via deviantart, people knew who he was. But the later was more because of “infamy” than popularity and the number of fans he had accumulated online were representing people interested in him at least since 2005 and did not quite represent his actual present day numbers of supporters at the time.

And mind you, the number of supporters was less than 100k, most of them likely underaged deviantart users. And if my research indicates something, then that most content creators with a halfway decent patreon earning need at least 100k+ followers in total. Because of those fans, only around 1-3% will on average then spend money on you, if you actually create content they enjoy and on a regular basis.

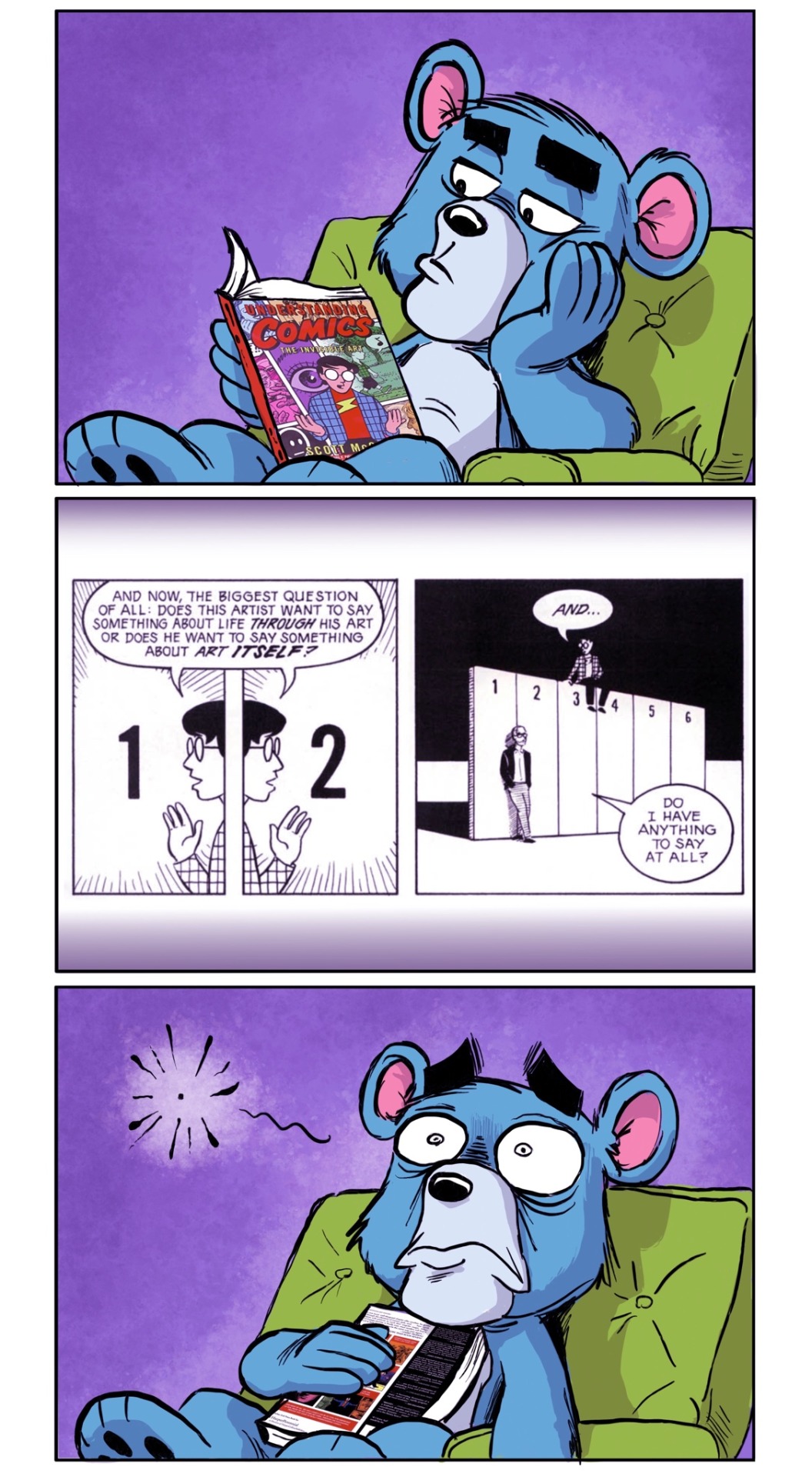

Which brings up the next major problem: Dobson did not create content people enjoyed and that in more than one meaning of the word.

On one hand, as pointed out by ripsinfest, he barely released any content at all over 2015 after a few initial months, despite the fact that he was obviously active online a lot, as shown by his presence on twitter. On the other hand, the few things he did create were not the stuff people wanted.

As an example: If you go to a restaurant and pay for a pizza, you expect the cook to give you a pizza. If however for some reason he just gives you a soda, you get ripped off and never come back. In Dobson’s case, the thing people wanted was not pizza but comic pages. But what he delivered was mostly bland fanart, such as of Disney and Marvel characters crossing over or KorraSami. Sure, a few strips of “So…you are a cartoonist” were still released at the time, but not really many.

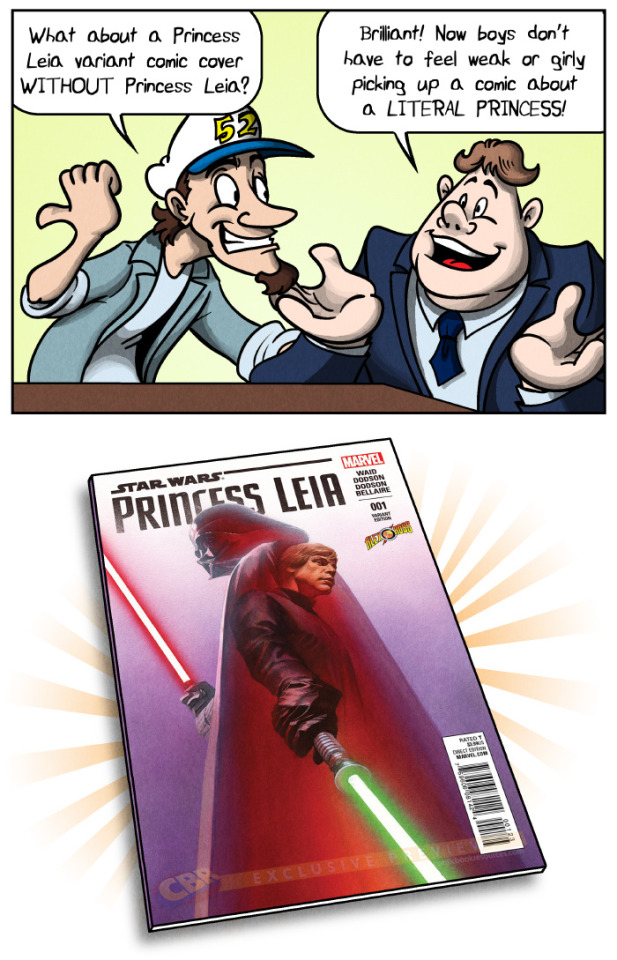

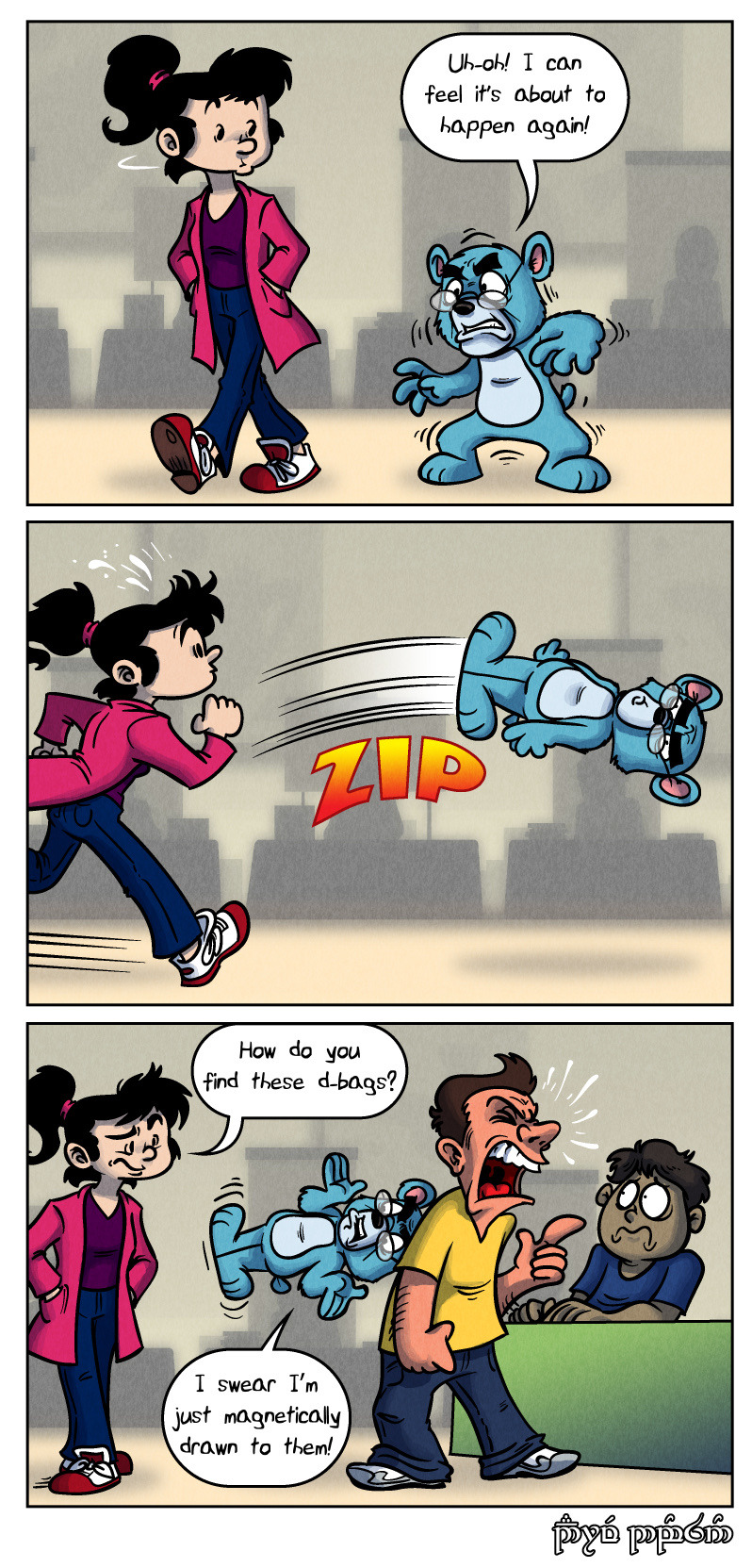

To give an overview: Taking the release dates on Dobson’s official SYAC site into account, he released around 16 strips of it between March and August of 2015, the last two being “No Leia” being titled “Zip line”

Afterwards, the next official strip released was “Anything at all” in October of 2016.

Now to be fair, there was at least one more strip at the time Dobson released via patreon, that is also save to see on kiwifarms and other plattforms, which has not been uploaded to his official SYAC page. Likely because he simply forgot about it.

But I think that in itself should tell you something about Dobson’s work ethics when it comes to his webcomics. He promoted his patreon in his own video as a way to ensure he can make comics in a timely fashion again for others to enjoy, but in an environment where certain artists are capable to create multiple strips per week at minimum, Dobson could overall not manage to produce more than 16 over a course of six months, which means an average production of 3 strips per month.

For comparison, Tatsuya Ishida of the infamous sinfest webcomic (a garbage fire of epic proportions from a TERF who I think should be put on a watch list) has produced on average 4 strips per week, including full page Sunday strips, for years and nowadays even releases stuff on a daily basis to pass the covid crisis. So a mad man who wants to see trnas people die, has better work ethics than Dobson.

In other words, people expected Dobson to actually get back into creating comics (with some even expecting a return of Alex ze Pirate), but he got in fact even lazier than before, releasing only SYAC strips and random fanart as a product. Which he then also tried to justify as his choice to make because a) he had mental health issues and b) no one can tell him what to do.

And sure, people do not need to tell you what to do. But when people pay/donate money to you expecting to get a certain product in return, they should get the product. Linkara e.g. by all means doesn’t NEED to review comics to have a fullfilling life, but he got famous for his reviews, people want to see his reviews and they pay him for those reviews. So obviously, he will continue those things.

Then there is also the fact that despite Dobson’s claims how he wants to create comics for everone to enjoy and that he aims to keep his artwork online for free so anyone can view it…(his exact words in his promotional video AND text on his patreon once upon a time)

youtube

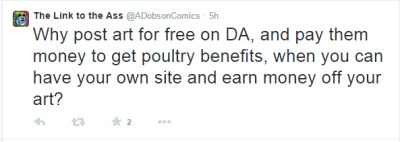

…the reality was, that he wanted to use patreon as a paywall. Something I actually kinda pointed out at on my own account (shameless self promotion) once, but want now to elaborate a bit. Basically at the time Dobson opened up his patreon, he also was on the verge of leaving deviantart as a platform people could look at his work behind. Which he eventually did.

Meaning that the only major platforms for people to watch any “new” stuff by him were his patreon or art sites such as the SYAC homepage or andysartwork. Which granted, he did EVENTUALLY put his stuff on.

But unlike other content creators who would put “patreon exclusive” new content up on more public plattforms often within a few days, weeks or a month after making them “patreon only” at first, Dobson waited longer and did barely anything to promote his sites as places to look his stuff up for a public audience. In doing so creating a “bubble” for himself that hurt him more than it helped, as Dobson made himself essentially come off as a snob.

A snob who did not create content for everybody to enjoy, but ONLY for those willing to pay him at least one dollar per month. As evident e.g. by the fact that as time went by, certain content was never released outside of his patreon at all, such as a SYAC strip involving Dobbear screaming at the computer because he saw a piece of art that featured tumblr nose.

Lastly, there is the issue of his patreon perks and stretch goals.

See, his perks were essentially non existent. Aside of the beggars reward of “my eternal thank you if you donate 1 dollar”, two other perks that come to my mind were the following: If you donated up to 5$ at minimum, you got your name thrown into a lottery to potentially win buttons and postcards of his artwork. Unsold cheap merch from years prior he failed to sell at conventions basically. There was just a problem with that thing: That lottery thing, which he also was only going to initiate when he reached a stretch goal of 150 dollar a month? It was illegal!

Patreon itself has in their user agreement a rule that forbids people from offering perks that essentially boil down to “earning” something via gambling, which this lottery by Dobson was.

(THOAD chiming in here to add that, in addition to all this, he fully admitted he would be excluding Patrons that he “knew were clearly trolls” from the lottery. Which made the already illegal lottery also fixed, so...yeah.)

The next thing coming to mind was his “discount” on previous books of his he offered online, if you donated at least 10 bucks per month to him. Or to translate it: You would get a bare minimum discount at pdf files of books such as Alex ze Pirate and Formera (you know, the permanently cancelled Dobson comics) if you paid up 50-75% of their original price on Patreon already. And considering the quality of his early works, he should have given you at least a book per month for free if you dared to donate him that much.

As for the stretch goals… lets go through them, shall we:

100$: A wallpaper per month. Something he did provide with eventually, but barely. And after less than five of those he stopped to make them overall

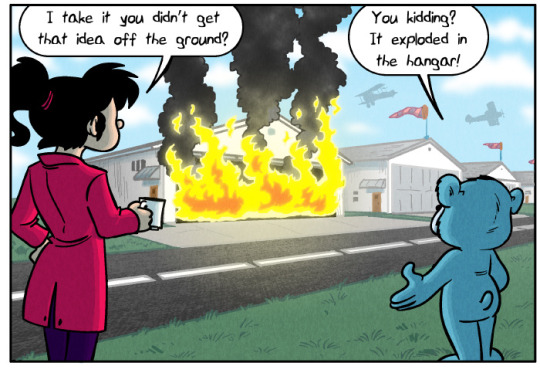

150$: Monthly Gift basket Lottery, which as I stated, was illegal and almost got him into serious trouble with his account. Also not an initial stretch goal he made up but instead came up with a few months into his accounts existence. Finally it got temporarily replaced by Dobson playing with the idea to use 150$ per month to open up a server and art site where people could upload stuff for free similar to deviantart, but under his administration. Promising a “safe space” for other artists. Which considering Dobson’s ego and inability to accept criticism or delegate responsibilities would have likely ended like this:

175$: Establishing a Minecraft server for him and his fans to play on. Meaning Dobson would have just wasted time he could spend on creating comics to endulge in his Minecraft obsession.

200$: Writing a Skyrim children book. Aside of the legal nightmare that this could have been (I doubt Valve would have been happy of someone else profiting of their property) I have to ask, who was even interested in Skyrim by 2015 anymore? Sure, Skyrim was a popular game and it had its qualities, but it was also a trend that had passed by that time. So in other words, there was not a market to cater towards here.

300$: A strip per week guaranteed.

… are you fucking kidding me? 75$ per strip essentially? Something people expect you to produce anyway if you want to be considered a “prolific” creator worth supporting online? Imagine if certain internet reviewers would do that, telling you that if they do not earn at least a certain amount of money, they will not produce anything, period, or less than usual. And Dobson had already proven that he can release more than just one comic within a few days, if he is motivated by enough spite.

600$: Starting a podcast with his friends to talk about nerd culture. In my opinion could only work under the assumption that people even like the idea of listening to Dobson and his opinions. Which considering how very little people like talking to him sounds doubtful. Also, considering how Dobson tends to be late to the party when it comes to nerd culture, likely tending to be out of date faster than he could upload. Finally... what friends?

700$: Returning the love, as he says it, by donating some of the money patreon users gave him to other content creators. This in my opinion is the most self defeating cause possible. On one hand sure, being generous and all that. But essentially Dobson admits here he would blow the money people give him to support HIS art on others, essentially defeating the purpose of HIS own account. He also does not clarify how much of that money he would donate, meaning there was a high chance that he would spend less than 10% of it on other creators, only creating the illusion of support while putting the actual earnings/donations into his own pocket.

2000$: A massive jump ahead. 2000$ per month would result in him getting better equipment (as in a new computer e.g.) and as such “potentially” make more comics. Mind you, only potentially.

This goal in my opinion is also the most fucked up one. Primarily for the following reasons:

Lets say Dobson would have achieved the goal and actually earned over 2000$ per month for at least a year. His annual earning would have been 24k, minus whatever he had to pay as taxes and payment for using the patreon service. And what would he do with this money? Get himself a better computer and equipment by paying a minor fraction of it once. Then he could use that computer for years to come while still having over 10k in his account, plus his monthly earnings. And he may still just produce 3-4 comics a month of a series that has as much depth to it than Peppa Pig if not less.

Sure, many patreon users have 2k+ as a stretch goal on their accounts to signify that if they could make that much monthly, they could have the necessary financial security to focus their time primarily on their content instead of a regular job. And if the content they create is actually well made, many people would support that or be okay with it.

But 2000 dollars to buy ONE computer and not account for how this money will add up over time? And that in light of such profits people may actually expect you to create more than you barely do already? That is either a case of narcissism, plain stupidity because you can't look further than 5 feet or just shows how Dobson did not understand at all the tool he had at his disposal.

Bottom line: Dobson, like many times before, fucked it up. He overestimated the potential support and resulting profits he could make, he expected that his name alone would be enough to assure gainings instead of creating content to justify support and he was unwilling to really give his supporters anything worthwhile back.

And while I am sure that there were also many other factors guaranteeing his failure, those at least to me, were his "common" mistakes most other people familiar even with the basics of internet popularity would ahve avoided.

#long post#patreon#syac#submission#very long post#andrew dobson#adobsonartworks#tom preston#adobsonart#soyouareandrewdobson#ripsinfest

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

What supplies would someone need to open an okiya? Same question for Ochaya.

I’m pretty sure that @missmyloko has written about this before, but I can’t seem to find it right now, so I’ll try my best ^^’.

As for okiya, the first thing that comes to mind is a big collection of kimono and obi. It depends on how big the okiya is, but you’d need enough kimono and obi to outfit a few Maiko (maybe like three is the minimum, I’d say?) at the same time, both senior and Maiko, and some kimono and obi for dependent Geiko as well (again, I’d say at least two? But they probably wouldn’t be as important as Maiko-kimono in the beginning).

In kagai that give their Geiko more time to become independent, the okiya have bigger collections of Geiko-kimono, in kagai where that’s not the case, the collection is smaller.

Of course, the collection would start out smaller and get even bigger over time, and once in a while, okiya also discard of old, overused items and sell them, if their condition is still good enough (Umeno did that last year, for example).

A regular Geiko-kimono costs at least 10,000 USD, with fancier ones being up to 15,000 USD and formal ones costing around 20,000 USD, and a regular Maiko-kimono costs around 15,000 USD and their kuromontsuki can cost up to 25,000 USD, and that’s not even counting any obi, so you can imagine to how much money just the clothing would amount to.

You’d also need hada - and nagajuban, eri, komon for the Maiko and houmongi and some tomesode for the Geiko for casual events, so the kimono-collection of an okiya can easily surpass 1 Million USD.

And then you’d also need hair ornaments and obidome! Regular daikin, maezashi and bira ougi wouldn’t be that expensive, but the tama, tachibana (only for junior Maiko) and hirauchi kanzashi (only for senior Maiko) and also the kushi very senior Maiko wear are already more expensive.

The kushi for Geiko are also quite expensive, and the bekko kogai they wear are made of real tortoiseshell and not only are these very expensive in the first place, since tortoiseshell-trade is heavily restricted nowadays, most of these pieces are antiques, quadrupling the prices. You’d also need toirtoishell-kanzashi for Maiko (kushi, hirauchi and chirikan) they wear them during their Misedashi and the first few days as Maiko and during very formal events like Shigyoshiki.

The obidome are the most expensive part of a Maiko’s outfit, and since they are worn almost every day, you need a good deal of them. They are made of precious stones and things like silver and platinum, so they can easily surpass the price of a kuromontsuki.

And then you’d of course need a building, you’d need the okiya itself. As far as I know, they don’t really build new ones anymore, so one would need to purchase a suitable building from the original owner, and this could, again, be over millions of dollars. Some of these buildings are smaller or bigger than others, so some okiya have enough space to house a lot of Maiko and Geiko at the same time (Komaya - 7 Maiko and 2 Geiko (I think?), Tama - 6 Maiko) and others only have adequate room for around 4 or 5 people, excluding the okaasan and the maids, who sometimes live on the premises.

Then, you’d also need furniture for the okiya, which needs to be of the finest quality, should guests be invited (which will be quite often). An okiya needs to be able to own expenive, high-quality furniture, both traditional and new, and art-works to not only show off their wealth, but also show that they are able to adequately support their Maiko and Geiko.

This is all excluding the running costs like utilities and food everyone has to pay for, and the lessons for Maiko and Geiko, the cleaning of the kimono, the maids and cooks etc. An okiya is incredibly expensive, 1 or 2 million seed capital won’t (even) cut it.

And you’d also need something that might be even more important than the money for both an okiya and an ochaya: You need conncetions. You could just go into any kagai and try and open an okiya or ochaya without any connections if you have enough money, but firstly, I highly doubt that you’d be very successful, and secondly, I doubt that they’d even let you (as in, purchase a building) in many districts.

You don’t necessarily need to be or have been a Geiko yourself to open an okiya or ochaya, but it does help, because it means that you already have many connections to the people working in the karyukai and the clients, have artistic experience and know what it’s like to be a Maiko/Geiko. However, you can also build relationships to the people in the karyukai in a different way (Katsufumi, okaasan of the newly-established Katsufumi Okiya of Kamishichiken, was a Geiko for only 2 years, but owned a bar and henshin studio for over a decade, Yuko, okaasan of the Umeno Okiya of Kamishichiken, was never a Maiko or Geiko, but grew up beside them and also has artistic experience).

And of course, as the okaasan of an okiya, you’d need girls and women wanting to be Maiko and Geiko to join you and as the okaasan of an ochaya, you’d need customers wanting to pay for your services and Geiko and Maiko wanting to work for/with you.

As for an ochaya, you of course wouldn’t need any kimono, obi or hair ornaments, you’d need the building and very nice furniture and artworks and also quite a lot of them, and everything would need to be absolutely spotless, so you’d also need to pay for maids and servers as well. Again, to open and run an ochaya, you’d need a lot of connections and people would need to like and respect you and think highly of you.

You’d need to be able to pay the restaurants preparing and delivering the food for you, you’d of course have to pay the Maiko and Geiko and you’d need to always be stacked up on expensive drinks, mostly alcoholic drinks like sake, wine, beer, shochu, whiskey etc., but also some non-alcoholic options, and depending on the guests, they might have to be personalized.

You’d need to buy less things to open an ochaya, but that doesn’t mean that the job of running an ochaya would be any less demanding than that of running an okiya. Not to mention that many okiya also have an adjoined ochaya, so they have to deal with a dual burden.

It feels like I’ve forgotten something, but that’s all that I can remember right now ^^’. If I’ve made any mistakes or you have something to add, please tell me so!

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Season 2, Cassette 8: Ohara Museum of Art (1980)

[tape recorder turns on]

Hello, I am curator Leah Akane, welcoming you to the Ohara Museum of Art, and our special exhibit of the work of the late Claudia Atieno. Toward the end of Atieno’s life, it was suggested by friends that she was walking toward more epic depictions. But as those works are unfinished, or perhaps not begun, we have but her more intimate concepts.

In this exhibit, we will see some of Atieno’s more political tributes to classic works, which were lost in the Great Reckoning. We also have the rarely displayed “Attentiveness”, which I feel has been an underrated part of Atieno’s catalogue.

Narrating your audio guide is journalist, artist, and dear friend of Atieno, Roimata Mangakāhia. We are (blessed) to have Mangakāhia’s knowledge not only of Atieno as an artist, but as a person. While not nearly as successful as her late friend, Mangakāhia has been an invaluable champion of Atieno’s work, perhaps as important to Atieno’s popularity as Atieno’s own talent.

We hope you find deeper understanding and appreciation for Atieno’s work, a life in art sadly cut short.

The exhibit begins in the main gallery. Artworks included in the audio guide are numbered. Enjoy your time at the Ohara Museum of Art.

[bell chimes]

One. “Stars”. Little remains of impressionist Vincent van Gogh’s work. There are a handful of photographs of “Starry Night”, and a portion of what remains in the paintings hangs in Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art. Its new (Harmer Island) structure, a masterpiece of modern architecture.

Many works of the European masters were lost in the Great Reckoning. Many works by artists worldwide were lost, but at the center of Western art history were the impressionists. “Starry Night”, Manet’s “Olympia”, Cézanne’s “The Card Players”. These paintings are often recreated by artists in our new society. An exercise in cultural reclamation of course, an attempt to return to the knowledge and art and history that was lost after the war. But with “Stars”, Atieno took this replication trend in a new direction, a direction that rejected recreating what was lot. In fact, Atieno’s replicas were reappropriations of classic images. In her way, Atieno was rejecting a return to the past and embracing the society, albeit the society she wanted, not the society that was.

From the moment I first saw Claudia in 1970, she was obsessed with replications. In “Stars”, she takes the stylized swirls and moist, twinkling glimmer of twilight, and brings all of its vibrant motion to a halt. The irony of Atieno’s version of “Stars” is its complete lack of stars. The black sky looms above a charcoal city at night, mostly war-scarred and evacuated. Or worse, eradicated. The stars likely shine and soar behind the choking clouds, unaware and unobserved. What we see is merely a moon struggling to be seen in a humid black haze above the town.

Notice in the center of her painting the church spire, broken. The rising hills along the right, rocky and charred. The homes him and roofless. There are large spirals of smoke mirroring van Gogh’s inspired blue swirls, but in Atieno’s “Stars”, we see only variations of gray. The one contrast in her bleak landscape is the tall flames in the foreground on the left.

Did you ever go to church? What is a spire? Did God do this to us?

If so, whose God?

Some critics refer to this as a fire representing the destruction of the Reckoning. But I believe that Atieno was attempting to evoke a bonfire, a possible celebration by the townspeople in the universe of her painting. A communal fire to burn old art, books, clothes and doctrines of the tribes which led the world to such destruction. The art of war, obviously, paintings and written accounts of war heroes, as we know now that war holds no place for heroes. All themes of national superiority were turned one by one to ash. Underneath the bleak sky, we have a fire of a new day, of a new people wishing to rid themselves of the package of their past, the treachery of nation states and family.

It’s a brilliant work and a perfect approach to artistic repurposing. It’s difficult to say when repurposing becomes just a copy or plagiarism, sometimes even the artist doesn’t know where to draw the line.

[bell chimes]

Two. “Attentiveness”.

Many critics claim Atieno’s “Attentiveness” is her most garish work, noting its bold, almost clumsy strokes and its unsubtle praise of her own fame and wealth. I don’t disagree with them, but I would hate to completely dismiss this work simply for its lack of tact and technique.

While Atieno never stated directly that it was a self portrait, it’s easy to place her as the woman central to this painting. Her narrow shoulders and short stature contrasted against the long, dark, braided hair.

The woman is exiting a luxury automobile, her head turned from the viewer, and a woman on the other side of the open car door, taking a camera from her bag.

Look at the photographer’s mouth agape, caught in a moment of surprise and awe at this chance encounter with a celebrity. Have you ever seen a celebrity? [chuckles] Were you this obvious about it? Are you impressed by luxury automobiles?

Do you wear driving gloves?

While she often bemoaned the loss of her anonymity and by extension, a freedom of self, Atieno most certainly relished the attention her career provided her. She would shower, dress, put on makeup, take off makeup, undress, shower again and repeat the process for two hours before a gallery opening.

She always dressed fashionably, but at private parties or events, she carried herself casually and comfortably. She did not like photographs, only compliments. She grew bored with conversations that did not acknowledge her talents at least occasionally. I had many conversations with Claudia that acknowledged her talents, as I urged her to focus on larger projects, pieces that could continue to impact the art world, as she slipped further an further into lazy drawings of discarded papers and staplers and weak forgeries disguised as tributes. I told her about her incredible talents and she liked that part. I followed it up with a critique of her process, and that she liked less.

In “Attentiveness”, Atieno does not paint the face of the woman, only the face of the woman who sees her.

Look again into the photographer’s stunned face. Do you see awe, panic, adoration in a single oval (moor) into glistening eyes, and a hand frantically clutching a camera strap. Do you believe cartoons are art?

This painting is garish. It is clumsy. But it’s so revealing of Atieno herself. I do not feel we can devalue its worth simply because it does not seem to show any skill.

If Claudia were still alive and could hear what I am saying, she would never speak to me again. But she’s dead and cannot hear what I am saying and will still never speak to me again, so what are you going to do?

[bell chimes]

Three. “Sunglasses and Cigarettes”.

These are two men wearing sunglasses. They both hold cigarettes. Next to them is an unpleasant looking dog. The five-buttoned suit jackets these men are wearing are dissimilar to the conservative business fashion of council employees or the simple structure of police jackets.

These men look quite different from usual police, even undercover officers. Atieno has also spent quite a bit of time on their mouths and hands. Notice the texture of her lines in these areas of the picture. Much more detail on their tight countenances and the tense physical postures. Their hands are clenched, cigarettes poking out of stone fists. Their lips curled, not in anger but stern concentrations. And unlike agents from the Society Establishment, they do not attempt to hide their observations of Atieno and her private home.

Statespeople who appeared at Atieno’s home often tried to gather information, but in a sociable and subtle manner. These two men and their dog, a mixed breed similar looking to a Dobermann pinscher though, stand brazenly at the curb staring directly inside.

Given the rectangular framing around this sketch, I believe Atieno drew this from the front window of an apartment she lived in years before I met her. It suggests she did not go outside to greet or confront them. I believe she was perhaps frightened or at least dubious of these men and their dog.

Claudia socialized with many politicians of the new society, as well as other well known artists and business owners. She wanted to be as important as her art. But the edges of these circles (--) [0:12:19] roughly with insidious people, people who do not trust nor like those within.

These men and their unpleasant dog were from some place we should not want to know. [softly] Look at the way they stand and stare. Do you feel watched? What do you think they know about you?

Who do you think they report to? Do you believe in conspiracies? Claudia did.

I saw men like these once sitting at small tables on the footpath outside a small café in Cornwall. They watched me, smoking their cigarettes. I did not believe them to be anything other than well dressed men with a bad habit and an unpleasant dog. But Claudia was certain they were dangerous and covert operatives. I told Claudia if they were a threat we should lay low, have fewer parties and get togethers, but we did not. I don’t know how strongly Claudia believed in her own stories.

We had more parties with bigger, more important, more controversial people. Her then lover, Pavel Zubov, brought many friends who talked often of the new New Revolution. Nothing ever came of their bluster. But in an unstable new world, revolutions are not difficult. What happens after a revolution is another matter, of course.

[bell chimes]

[tape recorder turns off]

[ads]

[tape recorder turns on]

[bell chimes]

Four. “Lamp”. Oil on wood.

Of this particular era of Atieno’s life, during the height of her frame, this might be my favorite work, the type of work I encouraged in her. A piece which when she finished it, I applauded and opened a vintage Cabernet (--) [0:16:43] I’d been saving for such an occasion.

Most of her paintings from this time pander to a broader pseudo-intellectual audience, in search of strange moderately confrontational art, a story they can tell others, a debate they can have over art’s virtuosity and validity. They may say this is not art, but that argument is the art itself.

In “Lamp”, Claudia basically painted an inverted yellow V atop a brown circle on a flint background. It’s geometric to be sure, and part of a post-war revival of art deco, all of the evolutionary flourishes of art nouveau eradicated, however. Here we see only the effects of the lamp, an incandescent shine in the dark, but the actual architecture of the device is missing entirely.

I spent a full 20 minutes raving to Claudia about this work when she showed it to me in 1969. We had not known each other long, and our initial relationship was almost like a master and pupil. I could teach her nothing about the craft of visual arts. But we drank wine and talked late into the night. For all of her political and refined small talk at parties with celebrities and power brokers, I was – I flatter myself, one of the few people she could really talk to.

There was Pavel, but their relationship was purely one of mutual and tumultuous passion for each other’s bodies. Claudia’s and my relationship was one of passion for creation.

My praise of this painting, original in a way she had seemed incapable of, so bold but on the noise politically, went past her. I told her this, this is what she should be creating, not staplers or glorifications of celebrity, not copies of other works.

She put the painting away and later told me she’d destroyed it.

When the staff at the Ohara Museum told me they were showing this work, I flew to Japan just to see it again. I’m glad she did not destroy it.

[softly] Look at its architecture, its balance. How it’s teetering slightly. It’s not physically possible, this lamp, but every element is in harmony. Look at that shade of yellow closely. How can a human make that color? It almost makes me angry.

Which brush strokes in this painting do you resent? Are they the same strokes you admire?

I’d like to tell you that this is her finest work, but in the past few years, more tributes and derivatives of “Lamp” have multiplied throughout the modern society art movement. Her work seems to be a cheap replica of itself, rather than an original that inspired hundreds of copies. Perhaps this painting’s brilliance has been eclipsed by the works it instigated.

Or perhaps I’m the wrong person to be narrating your walk through this exhibit. There are several other paintings I could describe to you, but I think after just a few you’ve got the idea. These works are decades old, and you’ve seen countless tributes or copies of them. You don’t need me to tell you what a clear acrylic box full of acorns mean. It honestly doesn’t mean anything. Or rather it means Claudia Atieno recognized that quantity was greater than quality, that celebrity simply means that demand surpasses supply. If she could keep generating new work, she could keep putting on exhibits all over the world, filling the needs of art-hungry survivors of a terrible war and its apocalyptic aftermath.

[bell chimes]

Five. “Box of Acorns”. Acrylic box, acorns.

I already said you don’t need to hear about this work, but oh I don’t know. [sighs] Perhaps you need to hear about it.

There was an oak tree on the island of her home in Cornwall, and she collected the acorns, I watched her do it. She found this acrylic in a warehouse of post-war debris. I was with her that day and we marveled at the number of paintings and sculptures in that warehouse.

[crying] I really didn’t…

[long silence, music]

[bell chimes]

[silence]

[bell chimes]

I’ll stop beeping in your ears. No, I won’t.

[bell chimes]

Eleven. There’s not actually a painting 11, but I’ll just go on the idea you forgot to press stop or you’re curious to see how far I’ll take this.

[sadly] I will tell you though that investigators found parts of Atieno’s body two years ago. They weren’t certain they were hers at first. Pieces of bone and clothing washed up on a lonely beach on St Agnes island. Then this year they found teeth and most of a torso underneath several inches of mud along a rocky beach. The torso had pieces of clothing that matched the previous clothes. They knew from the torso that the body had fallen, been crushed by the hard slap of gravity.

And 8-year-old girl found the body. The girl’s attendant had to report the girl to retraining at the institute. A-a place dedicating to ensuring that society’s new precepts aren’t disrupted.

Not much is known about the institute, and what is rumored about them goes unproven but… there is reason to be suspicious. There is reason to be more than suspicious.

I’m positive that the scars of seeing human remains were less impactful than the scars of whatever… [sigh/weep] recalibrating they’re putting her through now. Or perhaps she didn’t know what she found, just a blue gray mound of – fetid biology, vaguely human-shaped, partially preserved in salt and mud.

Maybe the girl could make out the outline of a person in this rotten flesh lump? Somehow, that’s even more frightening. Something that looks human but is not. Is not anymore.

Crushed from a fall, they said. But it wasn’t the fall that killed her. [scoffs] She’d been falling for years. It was the rocks, or something that she hit, I shouldn’t just say “rocks” out loud.

I never forgave her for slighting her legacy in favor of fame, but maybe I’m the one who needed to be forgiven. For demanding too much of her, for resenting her. [sighs] For adoring her. For lots of things.

Teeth and a torso. [chuckles] Someone should paint that. Oh god, I’m sure you’re gonna want your money back from this audio tour. Tell the folks at the Ohara that the tape player seemed broken, or tell them that you didn’t end up enjoying it. don’t tell them what I said. Or do, I don’t care. I honestly don’t.

I loved Claudia! She was a gifted artist and giving friend. She had a period of work this museum seems to like, but which I find contemptible for its naked pandering.

Maybe I’m just sad. I can’t reconcile my feelings. [whispers] I can’t believe they found her body! [deep sigh]

I can’t believe I don’t get to tell anyone anymore that she’s still alive. I probably knew she wasn’t. but I could always tell myself she was.

Bone fragments on the beach, near a home for preteens. The first post-war generation to grow up without parents. The great experiment for a bright new world. [sighs] I don’t know.

[tape recorder turns off]

“Within the Wires” is written by Jeffrey Cranor and Janina Matthewson and performed by Rima Te Wiata, with original music by Mary Epworth. Find more of Mary’s music at maryepworth.com.

The voice of Leah Akane was Julia Morisawa.

Don’t forget to check out the amazing “Within the Wires” T-shirts and Claudia Atieno art print at withinthewires.com.

OK. Our time is done, it’s you time now. Time to stop by the museum gift shop, grab yourself a souvenir book of paintings about [the sinus infection I have], pick up a poster featuring [me coughing] and buy a commemorative vase made out of [-].

#within the wires#season 2#season 2 cassette 2#ohara museum of art (1980)#within the wires transcripts

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 6: Watchmen

So HBO has spent the best part of 2019 looking for a show that can replace Game of Thrones as the big fantasy-action spectacle flagship for the brand and whilst they might not have struck gold a second time quite yet, what director Damon Lindelof has created could well be the best TV in 2019 has to offer. Let me explain. The original Watchmen graphic novel was created by writer Allan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons back in 1986 and basically serves as a huge middle finger to the mainstream comics establishment at the time. It received widespread praise not just for its political and social themes but also the nuanced complex characters created by Moore and the surreal, pseudo-dystopian setting loving rendered in Gibbons artwork. Despite the massive success of the book it was widely thought to be unadaptable, at least in movie format, although Zack Syder tried (and arguably failed) back in 2008. On the comics side of things there’s been prequels and crossovers but the idea of a straight sequel in any medium was considered sacrilegious to most hardcore devotees of the original work.

Enter Lost creator Damon Lindelof with an ambitious idea for a modern-day-but-alternate-history setting sequel and not only continued and updated the original work’s political themes but also kept the general tone of pulpy weirdness and cosmic absurdity that made the original work so unique. For the most part at least that’s what Watchmen 2019 is, simultaneously being jam packed with little details and subtle callbacks to the original as if to sate the content hungry appetites of a thousand YouTube listacles but still by and large its own thing, with characters, themes and a setting entirely divorced for the originals cold-war era politics. The big hot button issue this time is race, with the core existential threat of Watchmen 2019 not coming from Russian bombs or Lovecraftian squid monsters blowing up NYC but rather from America's own sordid pasting coming up to bite it. The show is set almost exclusively in Tulsa, Oklahoma (with brief detours to Vietnam, the arctic circle and the moons of Jupiter of course) and centres around the legacy of the very real and very disturbing Tulsa massacre, in which a small army of white supremacist thugs descended on the mostly black town killing what some estimated was over 150 people and displacing countless more.

The conflict in Tulsa in the world of Watchmen 2019 today is between the police, who all have to wear fluorescent yellow masks to protect their identity from bad guys (although some prefer more unique hero attire) and a Rorschach-masked right wing militia called the Seventh Kavalry, who want the more liberal america of the shows world to resemble something a little more like our own - oh and achieve world domination by giving a US senator the power of god, like I said, Watchmens’ weird. In the middle of this cop Angela Abar a.k.a. Sister Night, played masterfully by Regina King, has to tackle the mysterious death of her former police chief Judd, an equally mysterious wheelchair bound old man and the world richest woman, Lady Trieu (Hong Chau) building what is quite possibly a world-ending-doomsday machine next-door. The story twists and turns out from there and really has to be experienced first hand to be fully appreciated. Several key characters from the graphic novel make their return, Jeremy Irons is partially noteworthy as original Watchmen’s big bad Ozymandias with some bigger more game changing character reveals later on in the season.

Every actor in the show brings their A game which really helps to make this feel less like the traditional superhero fare and more like a serious TV drama, which in a lot of ways it is, although the wonderfully realised alternate history setting helps bring some of the more fantastical elements of the show into the spotlight. Watchmen 2019 is a different kind of comic book show, in world of CGI spectacle and never ending soap-opera style plot-lines, it stands proud as show with something real to say, one that challenges it’s audience with gleeful abbadon and, hopefully, one that will shape it’s medium for the better much like the original did.

0 notes

Text

DARK TRANQUILLITY

Interview with Mikael Stanne

by Daniel Hinds

(conducted August 1999)

Dark Tranquillity really established themselves as the forerunners of the melodic death metal movement in the 90s, with such albums as The Gallery and The Mind's I. Their unique blend of fast, thrashy death metal and highly melodic riffing and leadwork helped make them a household name in the metal community relatively quickly.

With their latest album, Projector, the band has taken a turn to explore new vistas, utilizing clean vocals and a more organic sense of melody than before. On the eve of the album's Stateside release, vocalist Mikael Stanne braved a hoarse voice and overseas connection to give me the low-down on one of Sweden's finest…

How would you say Projector differs from previous DT albums?

I think it differs a lot. We tried to experiment a lot more with this album, to kind of break free from what we'd done before. Going in and writing for this album was really different for us because we wanted to keep all alternatives really open. We got back from touring a lot for The Mind's I and we were like, 'Nope, we don't want to play this really fast stuff anymore.' We wanted to do something else, like focus more on the emotional parts of the music than we have in the past - take it a bit further. And the vocals had to change for the music, but I think that's the basic change - it's more open, more dynamic, more emotional.

Were you scared at all how people would react to the changes?

Not really. We thought about it, but we just said, 'This is exactly what we want to do,' so if people hate it, that's fine. If people love it, that's fine, too, it doesn't really matter. We just realized that we had to do this album, otherwise we couldn't go on playing. We couldn't do another Mind's I or another Gallery or whatever.

Has the songwriting process itself changed any?

Yeah, a bit. We're started writing using portable studios and computers and stuff, so we can make a lot of the arrangements at home and then present it to the other guys. Then we work on it from there and develop each idea. It's an easier process, since we know each other so well. Also, our drummer Anders contributed a lot to the music now. It's much more open and we feel we can do just about anything. It's really interesting and kind of a new start for us.

Are you looking forward to playing the new material live?

Oh yeah! This Friday is the first show, we're going to play a festival in Finland, so I'm really looking forward to that.

Why the title Projector?

Well, it came from the time when I was writing the lyrics, about a year and a half ago. I was having problems sleeping and just a lot of problems that I didn't really want to write about, but felt that I had to eventually. I started digging up all this stuff that I didn't really want to talk about and once I got it all to the surface, I had to see all these things from a different perspective. That's why you kind of put your distance to it. The more I thought about it, the bigger it got and that's what the 'projector' is: it kind of blows things out of proportion in order to make it more real and to see it with fresh eyes and from a new perspective. That's what it meant to me, to put light on small things and make them huge, make them a monster.

Could you tell me about some of the specific lyrics on the album?

They kind of deal with things that I hate, things about myself. Mainly, weaknesses and errors and all the stuff that you do and you hate but you can't do anything about, you know? I've come to realize that recently, that I do so many stupid things, I had to change my ways. As a step towards being better, I write about it first and expose the problem. A lot of it is about relationships between people, both my personal ones and other people. Basically, what really annoys me about hanging around in the city with the people I socialize with. The lyrics cover different aspects of this.

DT has always been blessed with cool artwork and I was curious how important the visual presentation of the band is to you.

We've always been interested in the graphic side and artwork and everything. Me and Niklas always kind of developed the concepts for T-shirts and the covers and everything, so it's always been a big part of it. For me and Niklas, anyway. We drew the first demo covers and EPs and stuff, so that's always been going on. Now Niklas is self-employed and doing graphics. He really wanted to do this whole concept for the album, with all the involved imagery. He does all the T-shirts and homepage and everything, to create an overall feel for the music.

I understand you've done a video for one of the tracks on Projector.

We just finished it the day before yesterday, actually. It's for the song "ThereIn" and we did it with a couple of friends of ours. We basically left ourselves in their hands and they did a video, which turned out pretty cool. Not as good as we expected, but it's okay. These kind of videos never get shown anyway, so there's no point in spending a lot of money on it. It represents the song and represents us, so it does what a video should do, without being too much.

There is a major tour in the works for DT soon. What details do you have so far?

Right now we're just doing festivals, but on September 17th, I think we start and go for six or seven weeks with In Flames, Children of Bodom and Arch Enemy through Europe. It's going to be our biggest tour yet. That will be a lot of fun.

Sounds like a pretty killer line-up.

Well, I think it is, it's a great package and we're all friends. It's going to be crazy and hazardous to our health. (laughs) Hopefully, we will do an American tour in November. We've been talking about it a lot. We were supposed to do it in August, but we didn't really feel right about that, so we'll do it in November, perhaps December.

Any new stops on this tour?

Umm…yeah, Poland, I think that's the only one on this tour. We also go to Japan in September, just for a couple of shows, and that's gonna be great. We'll probably go to Mexico as well. After that, we can retire. (laughs)

Do you get to see much of these countries you visit or is it mostly 'do the show and move on?'

Pretty much just move on, yeah. Sleep all day, eat, do soundcheck, do interviews, play, then leave. (laughs) Sometimes we get a chance, though. Sometimes we'll have a number of hours to just stroll around the city and that's great, but usually… Like when we went to Rome, we were like, 'Oh, great! We've gotta see this!' We didn't see ANYTHING! A big line of people, the inside of a bus, the inside of a club and that's it. It can really suck sometimes, but it's great anyway. The people are usually more interesting anyway.

Do you enjoy playing the big festivals?

We actually haven't done many festivals, just a couple small ones. When we were with Osmose, they weren't into doing festivals, as they thought of it as a waste of time more or less. Century Media is really trying to get is on the festivals, though, so we're doing Wacken this year and Friday this really big one in Finland. A couple others, I'm not really sure yet.

How did you get in touch with Century Media?

We contacted the manager that we heard about and said, 'We want to have a record contract, can you help us out?' So he sent out the record to several labels, and a lot of them were really interested and we started negotiating with like 6 or 7 labels. Eventually it came down to Century Media because they were the most open-minded and agree to our terms more than the other labels. We found out what a shitty, shitty industry that we're in. All these labels wanted to change us, to have us re-record the album, and do all this and that and tell us what kind of image we have to have for the video, etc. That's what we said in the beginning with Century Media: you cannot control us in any way. And they were like, 'Yep, totally cool, we agree to that.'

Did you have good luck with Osmose and Spinefarm?

Yeah, all these labels have been great. Spinefarm did a lot for us in the beginning. They aren't really a record label, they're more a distributor in Finland. That's their main thing and that's why they are kind of limited in their capabilities. Osmose did fabulous work and we cannot thank them enough for bringing out our records, but we just felt it was time to move on and since the album is kind of different, we thought 'let's make a record label change.' It felt like the best thing to do. Of course, it's been great so far and hopefully it will just get better.

Are you at all surprised by the level of popularity that DT has achieved so far?

Oh yeah! We're just a couple of friends hanging out and playing, that's what we do. Like in the beginning, when Skydancer came out, we didn't know what to expect, we just thought, 'This is not music that people get into nowadays, it's really a weird album.' But people got into it and we were like, 'whoa! Cool!' But it doesn't really affect us in that way. At the end of the day, what matters is what we think about it and if we love it, that's okay. If other people like, that's great. But it's still really hard to think of it in that way and when people say that we were founders of this 'Gothenburg sound,' it's so hard to think of it that way. We've just been playing forever. It's nothing that we really think about, but of course it's very flattering that people buy the records and come to our shows.

DT has done a number of tribute albums and I was curious what your take on that whole market is and if there are any bands that you think deserve a tribute but haven't got one yet.

It's a fun thing to do. It's flattering that a label asks us to do one, that they want to hear our interpretation of another artist's music. It's an opportunity for us to go into the studio and record some more, and that's always interesting. It's a challenge to do covers, too. I don't listen too much to the tribute albums, but if there's one of my favorite bands that have a tribute album, of course I'm going to buy it. Sometimes they're good, sometimes they suck all the way through. I listened to this Depeche Mode tribute album, it was pretty good. Smashing Pumpkins were on it.

How did you first get interested in playing music?

Like in '87, all of us in the band, we lived on the same street. We hung out every day, just sat around listening to records. We were nuts about music and calling up musicians and being really pathetic. We were kind of bored, as well, just sitting around talking all day, so me and Nicky decided, 'Let's start playing and see if we can be as good as these guys that we listen to.' So we started practicing and practicing and after about 5 months we decided we could play reasonably, and we asked our closest friends if they wanted to join a band. They were like, 'yeah, why not?' Nobody knew anything, so we just rehearsed and rehearsed, just to have something to do and our intention at the time was to do aggressive music that was also melodic. That's more or less always been our goal, to mix the really extreme stuff like Kreator and Sodom and the mellow stuff like Helloween and Blind Guardian.

Okay, it's 1999 so here is the obligatory Y2K question. How do you think things will turn out?

Of course there is going to be some problems, that's inevitable, but I don't think it will be such a big thing as it is all hyped up to be. I spoke yesterday about it with a friend of mine who works at Microsoft, and he said everyone is calling in, really worried, and all this paranoia. But it really isn't that big of a problem. It's going to be interesting to see like the suicide rate on New Year's Eve is going to be. I think it will be weird and a lot of people will freak out, but I'm just going to sit back and enjoy the show. (laughs)

www.darktranquillity.com

0 notes

Text

Art and Medicine

An Essay on the links between art and medicine

Art is the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.[1]The main feature is that it requires creativity and lateral thinking which provides people with different viewpoints and perspectives of particular situations and is very useful for effective problem solving. Medicine is the science or practice of the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.[2] Its regard as a science means that it is the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical world through observation and experiment.[3] At first glance, these two terms appear to be antonyms of one another. One which is expressive and the other which is regimented, however throughout this essay I explore how this is in fact not the case and how the study and practice of medicine relies on art.

An in-depth understanding of the human anatomy, is an area of knowledge required by all doctors. It enables them to link patient symptoms to possible diagnoses effectively. Anatomical drawings provide a visual representation of the aspects of the human body and help people understand it. Historically, medicine and art have been successfully intertwined, the development of medicine has also been dependent on art. Medical illustration for instruction first appeared in Hellenic Alexandria during the early 3rd century B.C. covering anatomy, surgery, obstetrics and plants that had medical properties. [4] Initially, anatomy was linked closely with science, culture and art, many of the anatomic drawings were amalgamations of these themes with the aim of simultaneously educating and entertaining the viewers. Some of which depicted cadavers as very much alive, full of character and eccentricity or contrastingly, dead. An example of this is pictured below.

This drawing [5] shows the subject as a young man emerging from the bushes on a hill. This background helps to add a feeling of anticipation and a sense of an important revelation being expressed. This could also be used to express the fact that the knowledge of the intricate structures that make up the human body were only just being discovered at the time that this drawing was created.

The artist depicts the male subject’s outer bodily features in a very realist style which enables the viewer to be able to relate to the subject and clearly identify it as a human being. It also influences the viewers’ perception of the organs being exposed in this piece.

On one hand the organs being shown seem real and believable as they are part of what seems to be a very real human being, expressing emotions not dissimilar to those that the viewer experiences on a daily basis. The way that the subject averts his eyes from the gaze of the viewer and uses his skin to cover his torso, expresses a sense of shyness and timidity that many people would have experienced as well as showing a sense of modesty.

On the other hand, the organs being shown seem unbelievable and magical. This is because the use of surrealism is a prominent component of this piece. One is not able to lift up their skin and reveal their organs as depicted here which makes the organs being revealed seem fake and unreal to some extent. Deeper analysis shows that the subject is positioning his hands as a magician does, adding an awe-inspiring, magical, implausible dimension to this drawing.

Whatever the interpretation, this drawing links the educational and artistic properties of anatomy, seamlessly, leaving the viewer to make their own conclusions as to what is real and what is not.

Specific aspects of practicing medicine can be described as art. An example of this is surgery which is defined as ‘the treatment of injuries or disorders of the body by incision or manipulation, especially with instruments’. [6] During the process leading up to surgery, often many imaging techniques are used to provide the surgeon and their team with an understanding of the condition they are dealing with, the pathology and how to go about rectifying the situation. These images themselves can be seen as art, they are visual representations of the body that tell a story, some of which make use of the different densities of aspects of the human body to create a detailed picture. Together they can be seen as art as each imaging technique enables to see the body slightly differently, examples of this include ultrasounds, which only show soft tissue and MRI scans which show a cross-section of the body part being scanned.

The invasive aspect of performing a surgery is also very artistic. A subtle example of this is that surgeons create incisions in the body enabling them to retract the skin, exposing organs of different shapes, sizes textures and densities. Upon revealing the aspect of the body concerned, the surgeon must inspect it and uses different tools to operate on the patient, cutting, stitching and removing parts of organs or blood vessels for example. The intricate workings of the body are being altered here improving bodily function in many people and leaving a lasting impression on the recipient. The need for a delicate hand, manual dexterity, a sense of purpose and an understanding of the medium that is the human body, is not dissimilar to an artist molding his structure or drawing his subject in a medium of paint or pencil. A more obvious example lies within the subspecialty of Plastic Surgery. This variation of surgery is most concerned with the outward appearance of different parts of the human body examples of such surgeries include rhinoplasties (nose jobs) and breast reconstructions from cancer. These require very intricate stitching to produce minimal scarring and the reshaping of parts of the body to look more aesthetically pleasing and more natural.

For surgeons, some of the most artistic procedures are found in microsurgical techniques where tissue is transferred from one part of the body to another based on establishing a new blood supply. This allows the surgeon to re-establish tissue in another location that can be rebuilt into something else. Here, the lines marking the division of medicine as art or science are increasingly blurred. Such procedures not only require extensive scientific understanding of anatomy and blood supply, but also are dependent on the surgeon being able to reshape one kind of bone into another. In the example of a tumour being removed from the mouth, a leg bone can be transplanted and carved into a mandible, for which an artistic perspective is paramount.

If doctors are criticized, it is often not for their lack of knowledge, but for a lack of insensitivity and for ignoring or being oblivious to the emotional distress affecting their patients. Mahajan (2006) warns doctors against allowing the science behind medicine to inhibit their humanity and sense of empathy. If medicine is viewed purely as a science, then the importance of successful patient-doctor communication and interaction is ignored. A knowledge of and ability to engage with fine art in particular, being able to deduce possible interpretations of artwork and be aware of the underlying emotional connotations being emphasised in the piece can help within the practice of medicine. This is because it makes a person more receptive to the people and emotions present around them, makes them more likely to notice intricate details regarding a person’s physical, mental and emotional state which can be crucial in correctly diagnosing a patient and providing the most suitable treatment overall for that patient. Also, the ability to analyse artwork can prove to be a great skill for doctors. This is because in the analysis of other subjects such as chemistry, the conclusions drawn are mostly based on fact that has been proven or a theory that is being developed, whereas art analysis draws on instinct, emotional response and the perception of a piece. Being able to look beyond the facts and particular list of symptoms to match a diagnosis with a patient can create a much needed patient-centered approach to medical dilemmas, focusing on the patient as a whole, seeing the bigger picture and then matching the patient with the diagnosis rather than the other way around. [7]

Though medicine relies on it, art can be its own form of psychotherapy involving the encouragement of free self-expression through painting, drawing, or modelling, used as a remedial or diagnostic activity.[8] The goal of this is to improve people’s mental health, specifically by reducing anxiety, helping to manage behaviour and addictions, allowing the client to explore their feelings and resolve emotional turmoil. Art therapists use their understanding of visual art in conjunction with counseling theories and techniques. It is widely practiced in hospitals, psychiatric and rehabilitation facilities, schools and other clinical and community settings and it is a prime example of how art can not only link with medicine but enhance it. [9]

TO

Sources

1. https://www.google.co.uk/?gws_rd=ssl#q=art+define

2. https://www.google.co.uk/?gws_rd=ssl#q=define+medicine

3. https://www.google.co.uk/?gws_rd=ssl#q=science+define

4. History, Present and Future of Medical Art

http://www.vesaliusfabrica.com/en/related-reading/karger-gazette/medical-art-through-history.html

5. National Library of Medicine

Tabulae Anatomicae: Venice, 1627.

6. https://www.google.co.uk/?gws_rd=ssl#q=define+surgery

7. Lisa Sanders: Every Patient Tells a Story: Medical Mysteries and the Art of Diagnosis (2009)

8. https://www.google.co.uk/?gws_rd=ssl#q=define+art+therapy

9. http://www.apexart.org/exhibitions/berlet.htm

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 100 Greatest American Music Venues | Consequence of Sound

Feature artwork by Cap Blackard

Where did you attend your first concert? Mine was at the Wiltern Theatre in Los Angeles. It was Counting Crows touring their second album, and for every detail that can be recalled of the actual performance is a bit of memory on how the space felt. The Wiltern was seated back then, and from the ornate chandelier to the first glimpse at a merch stand, the lasting impression was of how big everything felt, how a venue was a place you could get lost in, where the rules of reality didn’t necessarily apply.

Of course, part of that feeling is just youth, but the great venues do have a transportive quality. Details of the box office or the bathrooms or the bar all hold their own weight, building significance both in spite of and because of the experiences held in the rooms. And some of these rooms are better than others. Sure, the most unexceptional concert venues might be near and dear to our hearts because of the shows we saw there or the people we met, but the really great venues go beyond that. There is history between their walls, features that are unlike any other concert space, and state-of-the-art lighting and sound that allow for artists to realize their vision of live presentation.

We took all of this into account when selecting the best 100 venues in the US. Both major and smaller markets are represented, while the sizes range from arenas to bars. There are venues whose history extends back 100 years, and there are others built in this century. But they all hold a certain common ground. A big one is the booking, with most still lining their schedule with the best talent. A few that don’t make their money on national touring acts are known for booking top-tier local acts. All of these venues, though, are known for quality shows regardless of who is actually up on stage.

We’ve already asked our readers to weigh in on their favorite American concert venues. And a number of artists have made their own selection. Now, it’s our turn.

–Philip Cosores

Deputy Editor

Established: 2003

What You’ll See: Ian MacKaye, My Brightest Diamond, Cloud Nothings

Despite being sandwiched between two major cities, Connecticut is pretty barren when it comes to culture. Drive out to what feels like the middle of nowhere in Hamden, though, and you’ll find one of the state’s hidden gems: The Space. The all-ages venue sits in a huge, desolate parking lot, but once you step inside, it comes to life. Lights string the ceiling like silly string, a snack bar sits at the side with baked goods, and a flooded thrift store and arcade room hide upstairs.

It’s all types of cool without trying to win cool points, allowing The Space to boast the feel of a DIY Brooklyn space without all the pretension. Thanks to its tiny 150-person capacity and Connecticut’s limited venue options, concertgoers get an intimate show from bands that play far larger venues elsewhere on their tour. Then you step back outside and remember you’re in the middle of nowhere — which, ultimately, makes the venue feel all the more like an Alice in Wonderland trip.

–Nina Corcoran

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Established: 1930

What You’ll See: Animal Collective, Leon Bridges, Tyler, the Creator

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in September 2003, Cain’s Ballroom has a long history of serving various purposes, not hitting its stride as a contemporary music venue until relatively recently. It was initially constructed in 1924 as a garage for Tulsa co-founder W. Tate Brady’s vehicles. Six years later (or five years after Brady’s suicide by gunshot), Madison W. “Daddy” Cain converted the place into a dance establishment, giving it the name Cain’s Dance Academy.

From then on, it’s grown more and more synonymous with musical happenings in Tulsa, playing host to the Texas Playboys’ radio broadcast on KVVO and, after being sold to Larry Schaeffer in the 1970s, even the Sex Pistols in 1978. These days, a wide array of artists swing through for shows at 423 N. Main St. in Tulsa, including a considerable variety of hip-hop acts — A$AP Ferg, Tory Lanez, and Bones Thugs-n-Harmony are all scheduled for upcoming shows.

–Michael Madden

98. The Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace

Las Vegas, Nevada

Established: 2003

What You’ll See: Celine Dion, Rod Stewart, Reba McEntire, Elton John

Yes, the Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace looks like pure Vegas kitsch, a concert venue built to resemble the Colosseum of Rome. And yes, the residency program (inaugurated by Celine Dion) sometimes feels like an elephant graveyard for past-their-prime musical acts. But dig deeper, and this venue inspired by an ancient wonder soon reveals itself to be a modern marvel. The stage includes 10 motorized lifts as well as North America’s largest LED screen, which stands 40 feet tall and projects elaborate, seemingly three-dimensional backgrounds.

Despite a capacity of 4,100, no seat is more than 120 feet from the proscenium. That intimacy, combined with astounding acoustics and a stage spanning 22,400 square feet, means that everyone has a front-row seat for the always dazzling spectacles. All of these perks, combined with an extended stay in an exciting city, make these residencies very attractive to aging performers. If Rod Stewart or Reba McEntire aren’t your speed, that’s fine, but you’ll be glad it exists in 2031 when Jay Z starts his residency.

–Wren Graves

Established: 2012

What You’ll See: Burgerama, Beach Goth, Morrissey, Fetty Wap, Jenny Lewis

Using the shell of the Galaxy Concert Theatre, which hosted B-level gets like Sugar Ray and Medeski Martin and Wood for its run from 1994-2008, The Observatory emerged from a massive restoration that turned a 550-cap concert theatre into a two-room concert juggernaut. The main stage hosts acts ranging from hip-hop elite to Orange County legends in a 1,000-person space, while its smaller 350-cap Constellation Room is the only place in the OC to catch an act like Mitski or Into It. Over It.

One of the best aspects of the venue is how well it’s booked, landing better rap acts than any venue in neighboring Los Angeles, while often featuring bands offering warm-up shows before their much bigger LA or festival stops. It’s even become the sight of an occasional festival, with Burgerama and Beach Goth both utilizing the dual indoor stages and the outside parking lot.

–Philip Cosores

Established: 2002

What You’ll See: Synths, sun tans, and a sanctuary from mouse ears

Orlando’s countless amusement parks, performance spaces, hotels, and mini-golf courses make the sprawling central Florida city into an east coast Las Vegas, albeit one that was hit especially hard by the mid-2000’s subprime mortgage crisis. But a few Downtown O-town local hot spots weathered this economic hurricane and thank goodness for that.

The Social is still standing! And shaking, and grooving, as it continues an energetic tradition as the city’s best place to catch rock, electronic, and weekly acid jazz sets. The midsize venue is mostly built around concerts, but has sustained itself over time by becoming an incredible dance space that keeps the club kids, the rockers, and the Salsa fanatics equally entertained.

–Dan Pfleegor

95. JJ’s Bohemia

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Established: 2007

What You’ll See: That 1 Guy, Thelma and the Sleaze, Future Islands

JJ’s Bohemia is many things, but none of them are chic. A tiny space with a big patio attached (or a big patio with a tiny space, depending on your view), it feels as if every inch of the joint is covered with a sticker, a knick-knack, a string of holiday lights, or the front of a VW van. The vibe is undeniably chaotic, which meshes perfectly with the experience of gathering there for a show — when the stage is inches from your nose and no more than a few feet above you, it’s hard to not feel like a part of rock and roll in the making. Add in the free weekly comedy open mic, bartenders with devoted followers, and a handy disc-golf basket, and you’ve got plenty of reasons to roam off the beaten path.

–Allison Shoemaker

94. Count Basie Theatre

Red Bank, New Jersey

Established: 1926

What You’ll See: Brian Wilson, Randy Newman, Kevin Smith

The ‘burbs need concert venues, too, and the Count Basie Theatre caters to the bridge-and-tunnel crowd without making them drive across a bridge or through a tunnel. To that end, there’s something special about seeing legendary, decidedly mature musicians like Brian Wilson and Boz Scaggs right in your Garden State neighborhood, especially when they’re flanked by the Basie’s gorgeously detailed proscenium and celestial blue dome. But such classiness doesn’t drive away the occasional rowdy act: Bruce Springsteen has made several surprise appearances, and fellow Jersey hero Kevin Smith — whose comics shop, Jay & Silent Bob’s Secret Stash, is a mere half-mile away — has filmed a handful of his specials there.

–Dan Caffrey

Established: 1989

What You’ll See: Palm trees and great rock and roll

Like so many promoters-turned-club owners, Tim Mays was simply looking for a place to host shows when he opened The Casbah with Bob Bennett and Peter English in 1989. Eventually the venue became a haven for rock and roll of all shapes and sizes, from local heroes (Rocket from the Crypt, Three Mile Pilot) to alternative rock megastars (Nirvana! Smashing Pumpkins! Blink 182!). Now 26 years later, San Diego’s understated rock and roll mecca continues to be everything a small club should be.

With its 200-person capacity, there’s an intimacy to the current room (Mays moved the club up the street in 1994) even when your back’s against the bar. Posters adorning the wall pay homage to the city’s proud underground rock heritage, while the fake palm trees and year-round holiday lights give it the charm of a punk rock bungalow. There’s also music six nights a week, so yeah, it’s more or less a live music maven’s dream come true.

–Ryan Bray

Established: 2007

What You’ll See: Aesop Rock, Todd Barry, Eagulls, Mutual Benefit

The Crofoot is one of downtown Pontiac’s oldest structures. Nowadays, it’s a two-story building that contains three venues: the Crofoot Ballroom, the Pike Room, and the Vernors Room. It’s gone through numerous periods of turbulence in the past two centuries, facing the prospect of demolition as recently as 2005. It was at that time that the McGowan family of local preservationists sought to restore The Crofoot, ultimately leading to its reopening as a concert venue in September 2007.

Regular attendees are pleased to report their happiness about the above-average quality of sound and the politeness of the staff. While it may not draw household-name performers like some venues in Detroit and other areas of Michigan, the modern-day Crofoot’s combination of charm, intimacy, and historical value makes it an often underrated institution.

–Michael Madden

91. Rams Head Live!

Baltimore, Maryland

Established: 2004

What You’ll See: Queens of the Stone Age, Purity Ring, Metric, The New Pornographers

A lot of the best music venues in the US are anchored by their history, but there’s something to be said about what a modern room can be. A great example of this is Rams Head Live!, a concert hall that gets an exclamation mark in its name and doesn’t waste it. What might be most interesting about the space is that it doesn’t have to work with antiquated design.

Two levels of balcony zigzag the crevices of the space, allowing for viewing not just from the front of the stage, but from the side as well. When full, this can boost the energy to feel like the stage is surrounded by fans. History can be earned in time, but for now, Rams Head Live! provides a worthy alternative than traveling to DC for a mid-level band’s club show.

–Philip Cosores

This content was originally published here.

0 notes

Text

Inside the Mets construction of a museum without walls