#pamela colman smith

Text

The Woman Behind The World’s Most Famous Tarot Deck Was Nearly Lost In History

For centuries, people of all walks of life have turned to tarot to divine what may lay ahead and reach a higher level of self-understanding.

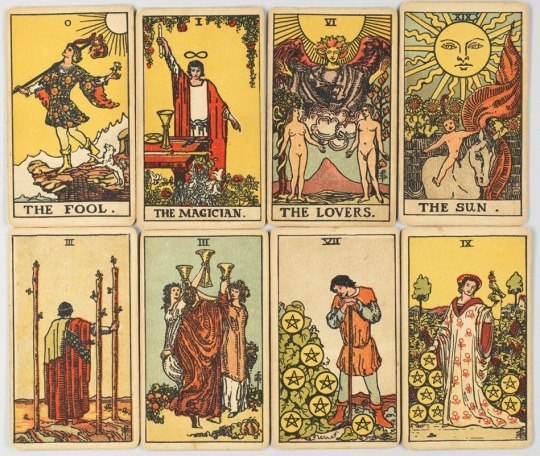

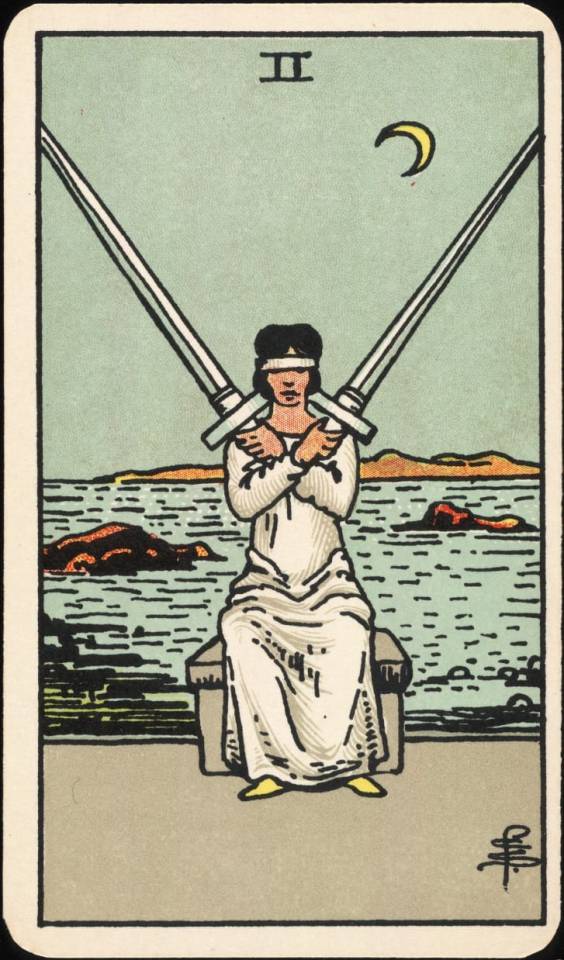

The cards’ enigmatic symbols have become culturally ingrained in music, art and film, but the woman who inked and painted the illustrations of the most widely used set of cards today – the Rider-Waite deck from 1909, originally published by Rider & Co. – fell into obscurity, overshadowed by the man who commissioned her, Arthur Edward Waite.

Now, over 70 years after her death, the creator Pamela Colman Smith has been included in a new exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York highlighting many underappreciated artists of early 20th-century American modernism in addition to famous names like Georgia O’Keeffe and Louise Nevelson.

CNN

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

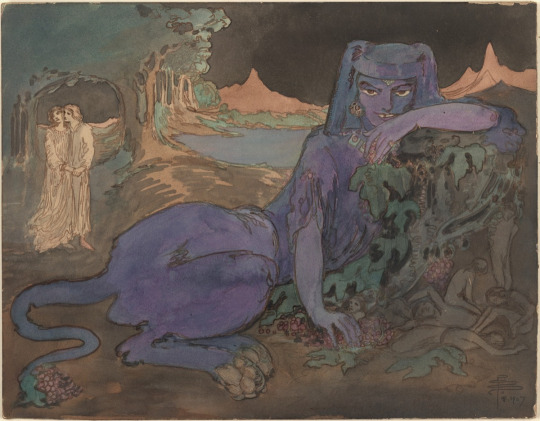

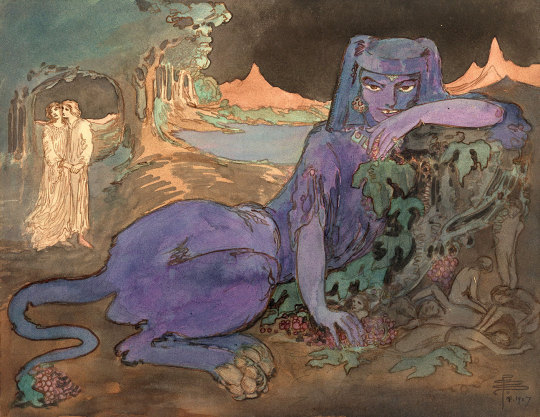

Pamela Colman Smith - The Blue Cat (1907)

851 notes

·

View notes

Text

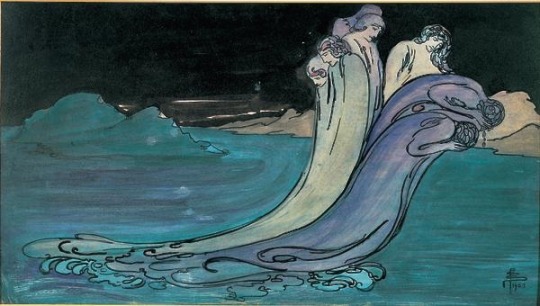

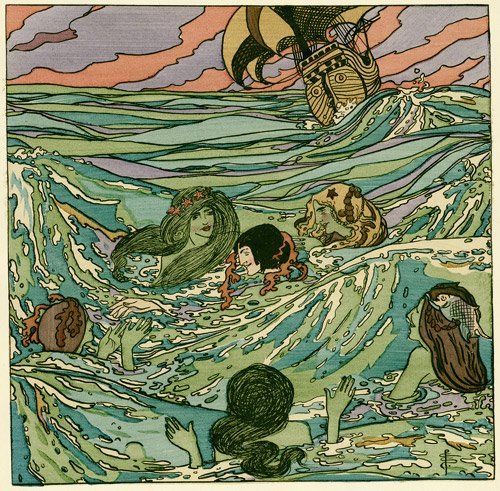

Pamela Colman Smith, "The City of Coral" from Susan and the Mermaid, December 1912 issue of The Delineator magazine

283 notes

·

View notes

Text

READ THE ARTICLE

#jewish#jewitches#judaism#jumblr#jewitch#jewish magic#witchcraft#witchblr#witchy#magic#tarot#tarot deck#tarot cards#RWS#rider waite#ride wait smith#pamela colman smith

892 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pamela Colman Smith, Illustrations

Artist of the Rider-Waite tarot deck

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

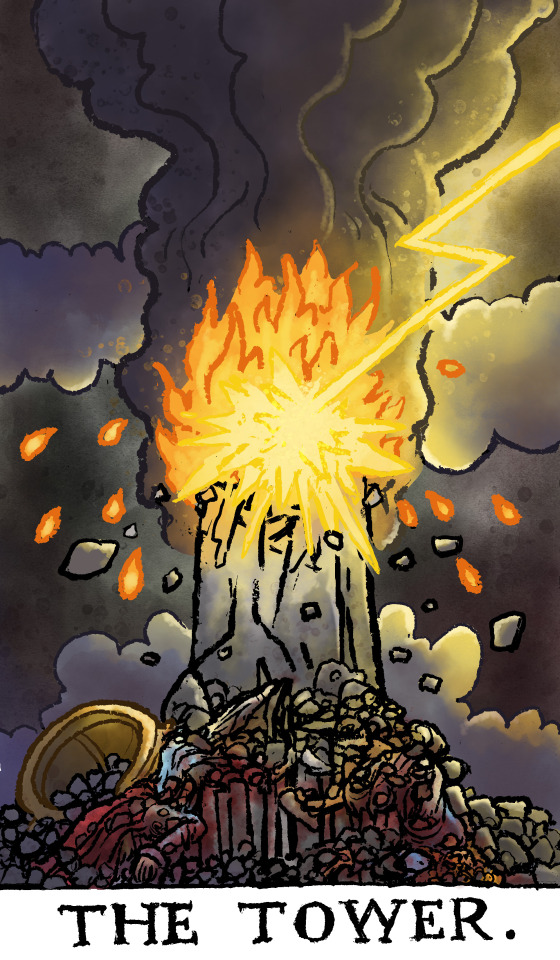

“Oops, All Towers,” a selection of Tarot cards from Aladdin Collar (with apologies to Pamela Colman Smith)

#tarot#pamela colman smith#divination#The tower#aladdin collar#symbolism#archetype#major arcana#occult#cartomancy#cartomanzia#ae waite#golden dawn#stella matutina

529 notes

·

View notes

Photo

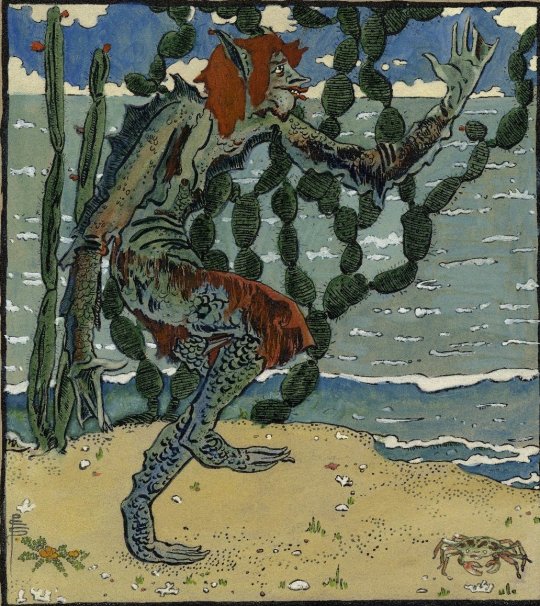

The Tempest by Pamela Colman Smith (1878 - 1951),

watercolor of Caliban

477 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pamela Colman Smith

The blue cat

1907

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spring Song by Pamela Colman Smith

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

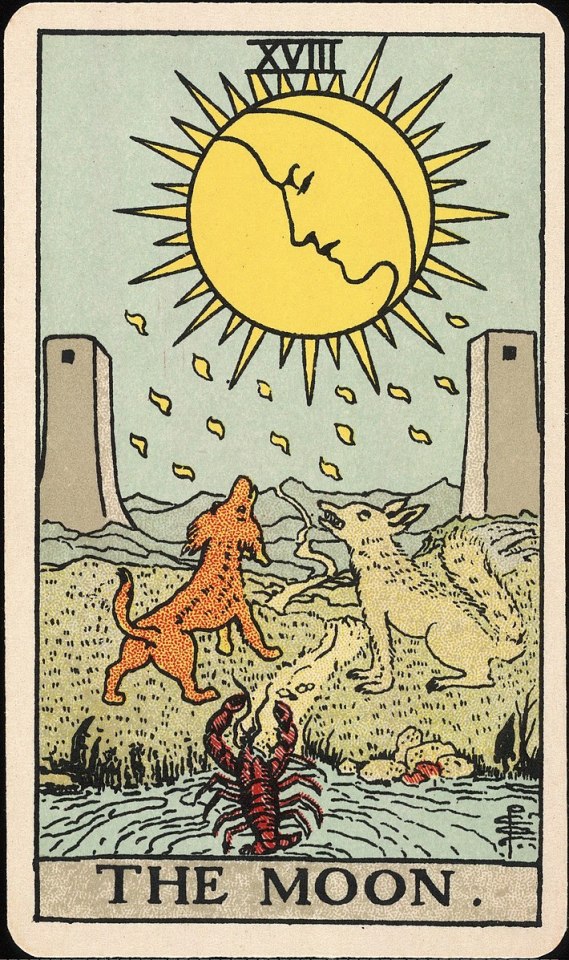

The Moon tarot card created by Pamela Colman Smith, 1909. Published 1937.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

No idea if this new 'The Artist' card actually exists, or it it was created for the cover of this new book "New Directions in Tarot; Decoding the Tarot Illustrations of Pamela Colman Smith" by Scott Martin. Book is published by Schiffer/Red Feather, but is available as a pre-order on Amazon. I get nothing for mentioning this book, am not being paid to promote it (would be nice if Red Feather gave me a free copy for being an influencer!); merely bringing a new book to your attention. The book will be available end of February 2024. Hardcover.

#pamela colman smith#pixie#tarot card reading#scott martin#pagan#wicca#witch#wizard#divination#cartomancy#tarot cards#occult#fortune telling#tarot

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Source details and larger version.

Here’s a collection of Pamela Colman Smith illustrations.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pamela Colman Smith - "Susan and the Mermaid" - The City of Coral (1912)

757 notes

·

View notes

Text

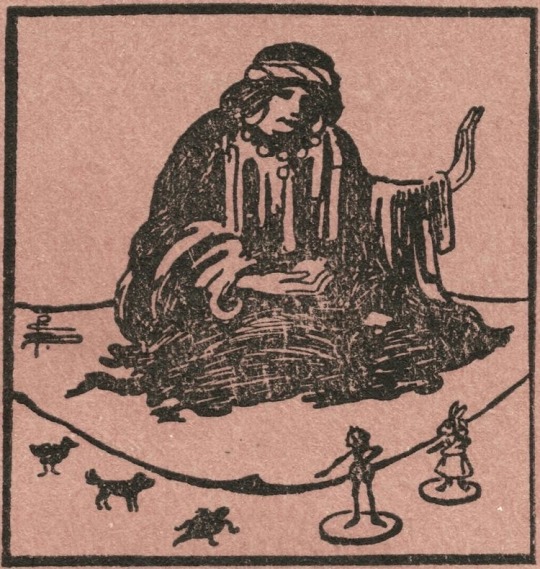

Y’all probably all know about the Rider-Smith tarot but have you ever seen a photo of Pamela Colman Smith, the woman who created the art for the cards? Because she looks absolutely Artistic and charming:

Apparently her nickname was also “Pixie.”

(Photo from the October 1912 issue of The Craftsman magazine)

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Self-portrait of Pamela Colman Smith

#pamela colman smith#art#illustration#portrait#portraiture#self portrait#autoportrait#autoportraiture

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pamela Colman Smith. Image in the public domain.

She’s the world’s most famous occult artist but her name is almost unknown.

Such is the enigma of Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951), an early 20th-century artist, writer, and mystic. Smith created dreamy, Symbolist-inspired watercolors that won her acclaim in her youth, including three successful exhibitions at Alfred Stieglitz’s famed New York gallery, 291, where she was the first non-photographic artist to have a show.

She was also an intimate friend of Dracula writer Bram Stoker, poet William Butler Yeats, and the actress and artistic muse Ellen Terry, for whom Smith designed illustrations and stage sets.

However, Smith’s most lasting artistic contribution was undoubtedly her designs for the Rider-Waite tarot deck. Made in collaboration with mystic and scholar A.E. Waite, Smith created the Art-Nouveau-inspired imagery of mythical archetypes set against luminous monochromatic backgrounds. Released in 1909, the deck is now regarded as the standard set, with more than 100 million copies in circulation. Smith’s imagery has become synonymous with tarot itself.

And yet, for more than a century, Smith went wholly uncredited for her contribution. Her claim to the deck was only cemented by her iconic serpentine signature, a monogram she created while studying Japanese design, and which she embedded into the decoration for every Tarot card.

“Tarot is a visual device—and yet the visual artist who composed them was eclipsed by Waite, the scholar, and Rider, the manufacturer,” said Micki Pellerano, a New York-based artist, astrologer, and scholar of occult history, “Academics, with all their inertia and corporatism, are somehow more palatable to the public and valuable to the market than artistry and vision… little has changed.”

But Smith has slowly been gaining recognition. The exhibition “At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism,” currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, features an entire vintage set of the Rider-Waite tarot deck with attribution to Smith alongside The Wave, a luminous 1903 watercolor and ink drawing in the museum’s collection. The artist’s place in art history is still forming, however, and her contributions are more complex than a simple story of rediscovery.

Pamela Becomes Pixie

Born in London to upper-class American parents, Smith moved through a sophisticated and cultured circle, spending her childhood in New York and then Jamaica, where she would be profoundly shaped by that nation’s folkloric history. Smith returned to New York in 1893, enrolling in Pratt Institute, though she would leave after two years to pursue her own interests, then returning to London following the death of her mother.

She was deeply involved in the literary world and her early accomplishments include the illustrations for a volume of verses by William Butler Yeats (1898), as well as the publication of her own writing, Annancy Stories, a collection of Jamaican folktales, and Widdicombe Fair, an illustrated version of a popular English folk melody.

By 1901, she had established a weekly salon at her London studio and apartment, and she started her own journal, The Green Sheaf, which she edited as well as contributing her own poems and illustrations. She devoted herself to miniature theater as well, constructing dazzling and diminutive stage sets for toy performances.

The Annancy Stories particularly won Smith admirers and a bit of notoriety. Smith toyed with gender conventions, granting the women characters in these stories more agency, and sometimes making the gender of the characters ambiguous. She’d also written these stories in Jamaican patois, with which she was familiar from her childhood—an unconventional decision at the time.

Smith was familiarly known as Pixie, a nickname bestowed on her by Ellen Terry and which captured something of her undefinable, impish spirit. Smith was often known to wear flowing robes, and occasionally pants, and her self-styling welcomed all sorts of speculation. “She adopted native costumes and wore feathers in her hair and colorful ribbons. It was almost like a self-constructed persona that she adopted,” explained Barbara Haskell, curator of the Whitney exhibition, in a phone interview.

Her sexual orientation and her ethnic makeup also sparked curiosity. She lived for many years with Nora Lake, her companion and business partner, with whom she may have shared a romantic relationship. Others have speculated that Smith was of biracial descent, with an English American father and a mother of either Jamaican or East Asian ancestry—although not much evidence exists to lead to any decisive conclusions on the matter. What was certain is that Smith was regarded as “other” by those around her and which in turn inspired her approach to art-making.

Early Fame and Acclaim

In 1907, Smith had her first exhibition at 291, featuring 72 watercolor paintings. These works were partially inspired by Smith’s own synesthesia, in which she experienced visual sensations set off by auditory impulses (her first synesthetic experience occurred while listening to Bach). She organized her works for the show with overtly musical references, such as overtures, sonatas, and concertos.

“In the 19th century, there was an idea that art was an expression of the unconscious and that it would elicit unconscious non-rational ways of thinking about the world,” Haskell said. “Smith would paint while listening to music as a way to unleash her unconscious, which would have fit Stieglitz’s mission at that point.”

This first exhibition was a commercial hit and Smith would have two more shows at the gallery in the following few years. Eleven of her unsold paintings and drawings remained in the collection of Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe. Eventually, however, Stieglitz would turn to a more masculine vision of Modernism, leaving Smith somewhat disheartened.

The Embrace of the Occult

From early in her life, Smith’s spiritual beliefs were oriented toward the esoteric and arcane. She had been raised a Swedenborgian, a mystical denomination of Christianity, and, as early as 1901, began to engage with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society that explored occult, metaphysics, and paranormal activities, which certainly influenced her artistic output.

For Haskell, these influences were symptomatic of the time. “Smith represents a strain of artists in early American Modernism who were disaffected with materialism and rationalism, but who were also unsatisfied with organized religion and so turned toward more occult pursuits,” she explained. “Theosophy was so influential at the turn of the century and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was similar—a secret society that looked at ancient texts, the kabbalah, and tarot cards. This was predominant among women and I think of Agnes Pelton as a parallel.”

Smith was eventually approached by A.E. Waite, a scholar of the Hermetic Order, who had ambitions to create a new version of the 78-card tarot deck, and who commissioned Smith to create the illustrations.

Waite, a Grand Master of the Hermetic Order, offered direction for his vision for the order of the Major Arcana, which is characterized by allegorical characters such as the Fool and the Sun. The Minor Arcana, cards in four suits of wands, swords, cups, and pentacles, were left entirely to Smith’s discretion, and she transformed these cards, which had traditionally been simply symbols, into lush, image-laden scenes.

The deck is mythical in scope, ranging from moments of exalted regality to mischievous pleasure, and Smith’s compositional signature predominates the cards: a lone, mysterious, medieval hero appears against a nearly Byzantine monochromatic background.

For Pellarano, Smith’s familiarity with the significance of the tarot is evidenced by her detail. “She possessed a rare command over iconography, and a deep understanding of it,” he said. “Her designs are constantly revealing new layers of information. They encode so much meaning and evoke so much contemplation, but are gentle in their elegance and appeal.” Haskell notes commonalities to the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. “She was in England, and through the theater, she was exposed to a lot of Pre-Raphaelite art” Haskell noted.

Some of the tarot archetypes are believed to have been modeled by Smith’s friends—Ellen Terry’s daughter, Edith Craig, appears as the Queen of Wands and actor William Terriss as the Fool. Smith, who struggled financially throughout her life, would receive no copyright or credit for her contribution, and was paid only a nominal commission.

A Retreat to Obscurity

Following the publication of the deck, Smith grew increasingly interested in Irish mythology, and in 1911, she made illustrations for Bram Stoker’s final book, Lair of the White Worm. But soon enough, Smith withdrew from the art world. That same year, she converted to Catholicism and with a small inheritance purchased a home in Bude, England.

There she would devote herself more fully to causes like women’s suffrage and the Red Cross. She would die at age 73 in Bude, all but penniless. “It was her decision. She just exited the art world,” Haskell said.

Still, Haskell believes it is time for Smith to rejoin the story of Modernism. “Art, more than words, presents the mood of the time, and Pamela Colman Smith’s work does get to the essence of a feeling of that era,” she said. “On one hand, people were excited about industrialization and that was the dominant mode, but there were also those who were very concerned that it was stripping individuals of a sense of spirituality and connection to their inner core. That certainly hasn’t gone away and we’ve come fully back into such a moment.”

“Smith’s works feel even more resonant,” Haskell added, “showing art as a way to find a personalized, spiritual connection to divinity in isolating times.”

3 notes

·

View notes