#postromanticism

Text

Everytime I abandone city, I met some new phenomenas. Lost things, waiting if they would be recognized. At least for me. I feel like I took pictures of aliens, magic creatures. Pictures of the part of the world that many don't pay attention for. Mostly because these things are for nothing, without purpose, they are absurd, without cash value. In a moments of irrational, they are my best friends.

#aesthetic#photodiary#art#blink of my eye#mobile photo#daily life#daily photo#life#photography#nature#afternoon stillness#beauty#witchery#witchcore#postromanticism#romanticsm#irracional#phenomena

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Richard Strauss: Im Abendrot (from Vier letzte Lieder) (1949). Upon a text by Joseph von Eichendorff.

André Previn, conductor

Arleen Auger, soprano

Wiener Philharmoniker

Ist dies etwa der Tod?

#richard strauss#im abendrot#arleen auger#andre previn#vier letzte lieder#postromanticism#joseph von eichendorff#Youtube

0 notes

Text

you know the aesthetic you're trying to find is obscure when there's less than 20 results for it on pinterest

0 notes

Note

11, 13, 21 for the ask pls? :3

11. favourite native writer/poet?

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer. School made me read his poetry while I was an emo teenager and there's no coming back. He made me feel shrimp emotions. He's from the postromanticism and AAAAAAAAAA god. Dear lord. Romanticism sure was an artistic movement.

13. does your country (or family) have any specific superstitions or traditions that might seem strange to outsiders?

It is (maybe) known that we eat 12 grapes in New Years. What may not be known is that we have to wear red underwear for some reason.

21. if you could send two things from your country into space, what would they be?

I assume this is meant in a positive way to get our culture to be known and not chuck 'em as far away as possible. So I'm choosing torrijas (they are similar to french toast but way better) to represent that we know how to cook delicious stuff and our cooking culture is very rooted on not wasting anything (its original purpose is to nor waste bread that has gone hard) and a copy of the Quijote because I think it still represents our culture and also it's iconic of Cervantes to be so pissed at the misinterpretations of his work that he made a sequel because of it

1 note

·

View note

Text

🎀 sierpien → postromanticism

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Strauss - Overture for the Prologue of Ariadne auf Naxos (1912)

I keep coming back to Richard Strauss' less 'popular' operas. During his lifetime many of them were somewhat dismissed for their 'conservative' writing. It seems that Strauss was going into a more jarring and angst ridden Modernism with his operas Salome (1905) and Elektra (1908), but then betrayed that direction with the very gushy romantic Rosenkavalier (1910). I think this lower opinion of Strauss has more to do with the time he lived in rather than the music itself. Not to mention that this 'heavy/lighthearted' florid style continued through both World Wars. It's hard for me not to love his music because of it's unusual mix of being hyper-romantic and also clear and easy to follow. What Strauss did was the seemingly impossible task of synthesizing Wagner (free floating harmonies, thick orchestral textures, and long scale structure) with Mozart (clarity, grace, lyricism, and more grounded functioning tonality). This is the opening of Strauss' comic opera Ariadne auf Naxos. The confusing title for this post is due to the opera's structure; It is an opera within an opera. The opera is in two parts, first part is the prologue which gives us the backstory where a composer has been hired to stage one of his operas at some very super rich Viennese man's house. He is deeply offended to learn that the patron has also hired a burlesque dance troop to perform after his opera. Offended because (and I'm pretty sure Strauss is satirizing the Romantic-minded young artist who takes his own work too seriously) his opera, Ariadne of Naxos, is supposed to be a super serious tragedy and having a burlesque dance afterward shows how the patron and audience don't care that much for 'serious' art, and may even look forward to the half naked women more than the Grecian music-drama. The opera company and dance company argue over who gets to play first. The situation gets worse when the patron's butler informs everyone that his dinner party ended up going later than expected, and since he's paid for both acts already and wants them to perform, he decided he wants the opera and the burlesque to happen at the same time. The composer is angry but his teacher encourages him to comply. And the lead of the burlesque show, a risqué comedian named Zerbinetta, charms him into changing the opera to include scenes for her. The second part is the opera Ariadne of Naxos, where Ariadne has been abandoned on the isle of Naxos by her former lover and hero Theseus. Zerbinetta and other nymphs (the burlesque dancers) try to sing and cheer Ariadne up but they can't get her out of her depression. Zerbinetta tells her the best way to get over one man is to find another, and encourages her to flirt with a clown Harlequin. But then a stranger comes to the island, who turns out to be Bacchus the god of wine, chaos, and 'hedonism'. Ariadne and Bacchus fall in love, the end. Despite how this opera is somewhat minuscule (in comparison to all opera ever, let alone Strauss'), it is the genius combination of Wagner (a 'super-serious' philosophical music-drama based on classical antiquity where love transfigures the soul), Mozart (lighthearted comedy, flirting between men and women who don't understand each other, and an optimistic idealization of a classical pastorale) and Strauss (a metafictional story about an opera within the opera where characters discuss the nature of opera and relationship between artist and audience, the kinds of themes that would be best exemplified in Capriccio). But really the only reason I'm sharing this is because the main melody is stuck in my head, the perfect Straussian melody; optimistic and upbeat, goofy-sounding accidentals, very sentimental writing based on subtle diatonic dissonances, and coming back again and again in different waves of great orchestral writing.

#Strauss#ariadne auf naxos#music#classical#opera#opera music#overture#opera overture#modern#modernism#postromantic#postromanticism#postromantic music#post romantic music#post romantic#post romanticism#modern music#modernist music#orchestra music#orchestra#Richard Strauss#Strauss Ariadne auf Naxos#Youtube

25 notes

·

View notes

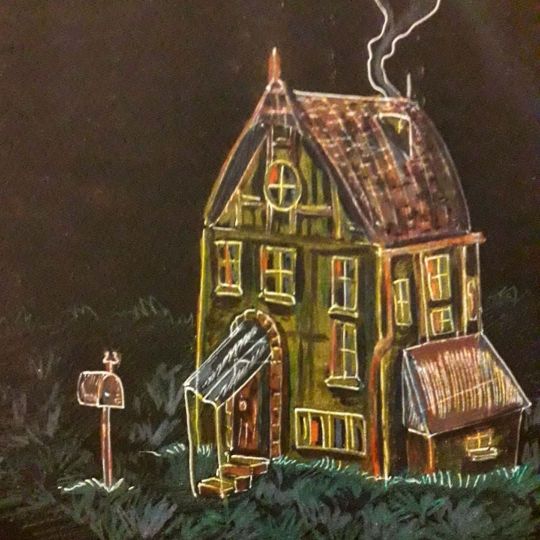

Photo

Environment design practice #house #temple #environmentdesign #drawing #practice #pencilart #penciksketch #instasketch #instart #art #storytelling #colorful #blackpaper #instadraw #postromanticism #edjovni #illustragram #fantasy #cute https://www.instagram.com/p/B71flytC-m0/?igshid=rkgecf9y1qx1

#house#temple#environmentdesign#drawing#practice#pencilart#penciksketch#instasketch#instart#art#storytelling#colorful#blackpaper#instadraw#postromanticism#edjovni#illustragram#fantasy#cute

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

For the first time, I saw in Dresden only a copy of a remarkable painting of Böcklin. The massive composition and mystical plot of this painting made a great impression on me, and it determined the atmosphere of the poem. Later in Berlin, I saw the original picture. In colours, it did not particularly excite me. If I had first seen the original, I would probably not have composed my “Isle of the Dead”. I like the picture more in black and white.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, about the painting that inspired his symphonic poem “Isle of the Dead”, Op. 29 in A minor

#rachmaninoff#rachmaninov#music#romanticism#postromanticism#post romanticism#bocklin#arnold bocklin#isle of the dead#painting#symphonic poem#quotes#quote

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

This is a piece from Sibelius that entered my heart since the very first day I listened to it. The illustrations show real pictures transformed into paintings. The dark one represents the dark and melancholic side of the piece, whereas the lighter one represents the optimistic message of the song. The dark painting has a style inspired by 20th-century cubism, meanwhile, the lighter one has an impressionistic style. Sibelius was an artist that made his message very clear: Recreate romanticism in a powerful, more modern-like way, but without leaving behind the feelings and the pain of daily life and post-romanticism. Listen to the link on the bio! . . . . . . . . . #sibelius #piano #pianomusic #impressionism #cubism #thespruce #romanticism #postromanticism #melancholy #optimism https://www.instagram.com/p/CTmCweZAY6A/?utm_medium=tumblr

#sibelius#piano#pianomusic#impressionism#cubism#thespruce#romanticism#postromanticism#melancholy#optimism

0 notes

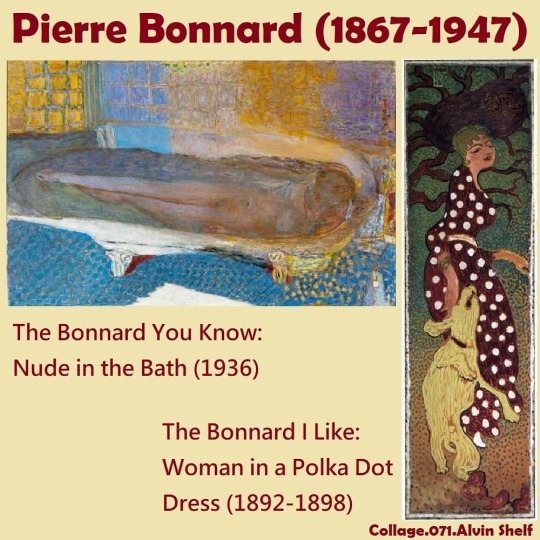

Photo

I like the lesser-known by the well-known. #pierrebonnard #postromanticism #nudeinthebath #womaninapolkadotdress #alvinshelf #collage https://www.instagram.com/p/CC0ikxvh5Pw/?igshid=15a8eg3ajly87

0 notes

Text

Anton Bruckner, 4 septembrie 1824, Ansfelden, Austria – 11 octombrie 1896, Viena

Schubert și Bruckner

Simfonia a IX-a de Schubert este prima simfonie de Bruckner. Fac această afirmaţie nu pentru a şoca (ar fi cu totul inutil), ci sub impresia că s-a vorbit insuficient despre legăturile care există între cei doi compozitori austrieci. Acuzat de wagnerism, pornind de la reala admiraţie manifestată faţă de maestrul de la Bayreuth şi de la ecourile wagneriene – şi ele reale – din unele simfonii, Bruckner este însă foarte apropiat de universul simfonic schubertian. Într-o privinţă, el pare să fie un continuator al lui Schubert, amplificând, construind polifonic, multiplicând o experienţă. Afinitatea spirituală dintre Schubert şi Bruckner, aspiraţia comună către o muzică a supremei detaşări, un simfonism al înălţimilor devin evidente, cu atât mai mult dacă nu căutăm simpla asemănare – ”citatul”. Continuitatea se poate observa cu relativă uşurinţă: ascultându-l pe Bruckner, ai impresia originalităţii gândirii simfonice dar, nu mai puţin, pe aceea a unui strat referenţial, a unui suport pe care pare să se sprijine în permanenţă. Fondul acesta rămâne fără îndoială experienţa simfonică a lui Schubert. Schubert, cel din ultimele simfonii. Schubert din marea Simfonie în Do major, partitură care înseamnă apoteoza gândirii sale orchestrale şi care, totodată, îl anunţă pe Bruckner.

Rareori în istoria muzicii doi mari creatori comunică mai îndeaproape decât în acest exemplu. Simfonia a IX-a, scrisă la sfârşitul vieţii (1828) şi cântată în primă audiţie 11 ani mai târziu (21 martie 1839) sub bagheta lui Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, ocupă un loc cu totul aparte în creaţia compozitorului. Ca experienţă simfonică, ea depăşeşte cu mult tot ceea ce autorul său dăduse la iveală; e chiar neaşteptată prin senzaţia de amploare, nu neapărat retorică, prin sentimentul monumentalităţii sprijinit încă pe expresivitatea melodică. Dar melodia se subordonează aici, până la ”umilinţă”, unei izbucniri de forţă – unui concept vital, sinonim cu aspiraţie, detaşare, în ultimă instanţă cu acea dorinţă de cuprindere a unui spaţiu uriaş. Dorinţă care poate fi tradusă prin sentiment cosmic ori prin principiu ordonator al experienţei afective, în mod sigur – una a plenitudinii. Raportul cu universul, ambiţia de a concura un echilibru obiectiv prin desprinderea de mărunte pasiuni, de sensul grotesc al existenţei sunt câteva dintre ”ideile” considerate frecvente în creaţia lui Bruckner. Le găsim anunţate în ultima simfonie de Franz Schubert. Aici romantismul său pare să fi depăşit, ca experienţă stilistică, faza de afirmare vulcanică; romantică în accepţia tipologică a termenului, Simfonia în Do major aparţine mai degrabă unei reevaluări stilistice. Nu ar fi deloc deplasat să spunem că orizontul ei se înscrie deopotrivă în structurile postromantice, exact prin echilibrul deplin al expresiei, prin maturitatea aspiraţiei. Un edificiu masiv, înălţat totuşi cu supleţe, ca un exerciţiu de verticalitate – exerciţiu de perfecţiune ce răzbate din construcţia acestei simfonii. La fel ca, mai târziu, în muzica lui Anton Bruckner.

Ascultaţi Andantele introductiv al părţii I şi vă veţi simţi negreşit în vecinătatea cea mai sensibilă a muzicii lui Bruckner: aceeaşi robusteţe a temei cardinale, cu acele intrări parcă supradimensionate ale alămurilor şi care solicită, din partea dirijorului, un rar efort de echilibrare pe întreaga desfăşurare a muzicii. Dispunerea temelor principale: una de largă respiraţie, neînduplecată şi rostind ”aspru” nevoia de confruntare, cealaltă, ”feminină”, poate uşor descriptivă, ca o compensaţie, păstrată mai ales pentru partidele suflătorilor de lemn, trimite direct la Bruckner. O temă cardinală, lansată mereu în cucerirea strălucirii şi monumentalităţii, temă de asalt; opusă ei, tema de caracter (cf. unei denumiri bine argumentate) sunt stâlpii de rezistenţă ai construcţiei. Simfonia în Do major configurează acest mod de organizare – de clarificare a materialului tematic. Asaltul din prima parte parte se dovedeşte tipic brucknerian, în timp ce sugestiile de marş din cea de-a doua, Andante con moto (mai lungă decât prima), trimit la Mahler. În rest, o spectaculoasă pagină bruckneriană se ascunde în această copleşitoare Simfonie în Do major.

Franz Schubert, Simfonia a IX-a în Do major, D 944. Orchestra Filarmonicii din Viena, dirijor: Riccardo Muti. Părțile sunt: 1. Andante – Allegro ma non troppo; 2. Andante con moto; 3. Scherzo. Allegro vivace – Trio; 4. Finale. Allegro vivace

”Un mistic gotic rătăcit în plin secol XIX”

La mai bine de un secol de la moarte (11 octombrie 1886, la Viena), muzica lui Anton Bruckner continuă să fie refuzată de o categorie, nu foarte restrânsă, de melomani. Alăturat lui Mahler, simfonismul brucknerian este considerat greoi, plictisitor, dacă nu de-a dreptul ”ininteligibil”. Şi, ca revers, adepţii sunt, ca şi în cazul lui Wagner sau Mahler, fanatici. În ce priveşte receptarea muzicii lui Bruckner nu există, se pare, cale de mijloc. Decât poate pentru cercetător şi pentru critic, dacă are echilibrul necesar. Dar şi în această privinţă, istoria receptării operei bruckneriene e plină de contradicţii şi contraste care le repetă într-un fel pe cele din timpul vieţii compozitorului născut în 1824. Bruckner însuşi a operat destule modificări în partiturile, socotite încheiate, ale simfoniilor sale. Multe dintre ele, se spune, la sugestia sau insistenţa prietenilor. În plus, acest muzician aproape umil îşi făcuse o regulă din a se consulta cu interpreţii şi simpatizanţii lungilor sale simfonii chiar în timpul, de obicei îndelungat, al elaborării lor. Trăia suficiente clipe de derută, de îndoială; la cealaltă extremă, avea momente când respingea ferm părerile dirijorilor care îi condiţionau executarea simfoniilor de prescurtări şi schimbări în orchestraţie. Ceda greu, treceau ani lungi până când se hotăra… Simple contradicţii creatoare? E greu de ştiut astăzi dacă şi cât era de acord Bruckner cu asemenea ”revizuiri”. Documentele ar arăta că nu le admitea decât de circumstanţă. Vorbind despre prescurtările făcute în partituri, Bruckner se exprimă cu claritate: ”Întregul este pentru mai târziu, şi numai pentru cunoscători şi prieteni…” Accepta modificări ”în spiritul execuţiilor de atunci”. Avea (care compozitor nu are?) slăbiciunea firească de a dori să-şi asculte propria muzică.

După moartea lui Bruckner, apropierea de muzica lui s-a făcut în aceeaşi manieră contradictorie, dar la altă scară şi cu perioade de eclipsă. La începutul secolului XX, Bruckner avea deja adepţi fanatici, pe linia marilor dirijori care îi promovaseră simfoniile încă din ultima parte a vieţii, Hans Richter, Arthur Nikisch, Felix Mottl. Nu e deloc curios că fiecare a dorit să servească această muzică în chip diferit. Pe de o parte, cei pe care i-am putea numi continuatori ai manierei dictate de dirijorii contemporani lui Bruckner, prescurtând majoritatea simfoniilor. O dată memorabilă, 11 februarie 1903, când a avut loc prima audiţie a Simfoniei a IX-a în re minor, rămasă neterminată, aducea ideea de retuşare considerabilă a partiturii, prezentată de Ferdinand Löwe în altă orchestraţie, din dorinţa sinceră de a o face viabilă… Acest elev al lui Bruckner opera un fals grosolan, deşi nimeni nu l-ar putea acuza de contrafacere. Era animat de cele mai bune intenţii, pornind de la realitatea partiturilor bruckneriene – de la inventarul de versiuni ale aceleiaşi lucrări. O statistică alcătuită de Mihai Moroianu, autorul unei solide monografii ”Anton Bruckner” *), arată astfel: ”Dacă răsfoim cele 9 simfonii şi cele 3 misse, vom întâlni multiple remanieri, după cum urmează: Simfonia întâi numără două versiuni în 24 de ani; Simfonia a doua, trei versiuni în 5 ani; Simfonia a treia, trei versiuni în 16 ani; Simfonia a patra, patru versiuni în 15 ani; Simfonia a cincea, două versiuni într-un an; Simfonia a opta, patru versiuni în 5 ani; Missa în re minor, două versiuni în 12 ani; Missa în mi minor, două versiuni în 16 ani; Missa în fa minor, trei versiuni în 22 de ani…” Aşa încât cerinţa expresă a lui August Gollerich, care solicită în 1912 ”restaurarea ştiinţifică a întregii opere după manuscrisele iniţiale”, era salutară, ”căci, într-o anumită privinţă – scrie Mihai Moroianu – drumul parcurs de la prima redactare şi până la transformările efectuate în decursul anilor conferea operelor bruckneriene un bizar caracter de produs colectiv, diacronic, care nu putea fi tolerat. De aceea, s-a pus întrebarea dacă înşişi discipolii maestrului intuiseră pe deplin întreaga semnificaţie a acestei opere atunci când s-au grăbit să-i dea sfaturi. Toate faptele ne îndreptăţesc să ne îndoim de acest lucru: ei se mărgineau să-şi venereze idolul cu acelaşi fanatism cu care îl slujeau şi pe Wagner. Abnegaţia cu care au colaborat la primele «ediţii canonice» ale operelor bruckneriene şi munca lor anonimă pentru modelarea şi aşezarea acestor monumentale simfonii în câmpul de forţă stilistic wagnerian stau mărturie în acest sens.”

Treptat, la câteva decenii de la moartea compozitorului, restaurarea partiturilor bruckneriene în versiunea originală, înlăturând şirul de subiectivităţi ”anonime”, începe cu adevărat să se producă – mai ales odată cu înfiinţarea la Viena a Societăţii Internaţionale Bruckner, de către Max Auer**). E drept însă că, în ciuda eforturilor, nu în toate situaţiile contribuţia străină din partiturile lui Bruckner a putut fi identificată…

Dincolo de toate aceste probleme de reconstituire fidelă a textului brucknerian, monumentalitatea simfoniilor sale, puse în relaţie cu creaţia similară a lui Beethoven şi Schubert, apoi, ca modalitate de abordare a materialului sonor, cu Wagner, în admiraţia căruia a trăit, entuziasmează astăzi prin raportarea directă la planul divin pe care aceste lucrări ample, cu multe lungimi, o conţin. Pe cât de stângaci, până la grosolănie (spun unii), pare să fi fost omul, pe atât de elocventă este apropierea lui de esenţa adoraţiei creştine. Legendele savuroase legate de modestul organist de la Sf. Florian trezesc interesul pentru biografia sa, de altfel nespectaculoasă. Se spune, printre altele, că Bruckner i-a dat un bacşiş lui Hans Richter după ce acesta îi dirijase o simfonie… Posibil, dar puţin important.

Liszt l-a numit pe Bruckner ”menestrelul Domnului”. Mahler spunea că autorul Simfoniei ”Romantica” este ”jumătate Dumnezeu, jumătate prostănac”. Claude Debussy considera simfoniile lui Bruckner ”munţi de linte”, cu ”inconsistente dimensiuni, pretenţios colosale”, criticând repetările inutile ale motivelor şi vorbind despre ”barbaria bruckneriană”. Pentru Furtwängler, Bruckner a fost ”un mistic gotic rătăcit în plin secol XIX”. Postromantismul brucknerian are, într-adevăr, o pronunţată tuşă medievală. Dar legăturile nu sunt greu de făcut, cum am văzut: între Schubert şi Bruckner, de pildă, continuitatea este directă. Spiritul vienez nu e deloc absent din opera lui Anton Bruckner, maestrul orchestrei transformate într-o imensă orgă, misticul alămurilor de foc. O orgă în care nu se mai întrevede nimic din spiritul baroc al lui Bach, pentru că aici spaţiul este dilatat, totul fiind gândit pe acea dimensiune verticală ameţitoare, proprie goticului. Diferenţele, care îi pot deruta pe mulţi, împiedicându-i să observe că într-o măsură drama interioară se repetă, trebuie căutate tocmai în felul în care complexul singurătăţii e trăit de Schubert şi Bruckner, aceste firi retractile, deopotrivă înfrânte. La primul singurătatea e un refugiu, modalitate de conservare a bogăţiei vieţii psihice. Schubert se simte poate chiar mai singur când se află într-o companie oarecare, trăind o viaţă paralelă impenetrabilă. Celălalt, dimpotrivă, caută mereu un punct de sprijin, singurătatea lui e disperată. Simfoniile sale sunt asemenea proiecţii grandioase prin care poate fi atinsă iluzia comunicării.

Privit astfel, maestrul de la Sf. Florian reprezintă o împlinire a gândirii simfonice, partiturile sale părând absolvite de orice retorică, de acel ”înveliş” prea mult criticat. Dezvelită în toată măreţia ei, muzica lui Bruckner rămâne un imn închinat Naturii şi Firii. ”Dacă există în Muzică un aspect uman, unul naţional şi altul universal – scrie Michel Lancelot într-o monografie***) publicată în 1964 – nu întâlnim nici un alt creator la care aceste trei elemente să fie reunite cu atâta plenitudine ca la Anton Bruckner… El cuprinde şi uneşte într-o singură imagine pământescul cu divinul, temporalul cu eternul, cântecul pădurilor şi al câmpiilor cu cel al ursitei omeneşti, în esenţa sa cea mai elevată, cea mai definitivă.”

________

*) București, Editura Muzicală, 1972.

**) Iniţial, Internationale Bruckner Gesellschaft, mai târziu Internationale Bruckner & Hugo Wolf-Gesellschaft).

***) ”Anton Bruckner: l’homme et son œuvre”, Paris, Seghers, 1964.

Integrala Simfoniilor lui Anton Bruckner. Orchestra Filarmonicii din Berlin; Orchestra Simfonică a Radiodifuziunii Bavareze, München. Dirijor: Eugen Jochum. Înregistrări realizat în 1958; 1964 – 1967, Deutsche Grammophon

Vezi Arhiva rubricii Filă de calendar

”Anton Bruckner, «menestrelul Domnului»” de Costin Tuchilă Anton Bruckner, 4 septembrie 1824, Ansfelden, Austria – 11 octombrie 1896, Viena Schubert și Bruckner Simfonia a IX-a…

#Ansfelden#Anton Bruckner#Arthur Nikisch#August Gollerich#Austria#Bach#Claude Debussy#Costin Tuchilă#Cristian Mandeal#cultură#Eugen Jochum#Felix Mottl#filă de calendar rubrica leviathan.ro#Franz Schubert#gotic#Gustav Mahler#Hans Richter#integrala simfonilor lui Bruckner#menestrelul Domnului#Michel Lancelot#Mihai Moroianu#mistic#muzică clasică#Richard Wagner#Sf Florian#Simfonia IX Schubert#Viena#Wilhelm Furtwängler

0 notes

Audio

Love Will Tear Us Apart (Elegy Version)

re-arranged by Matt Howden in 2011 • Sheffield, UK

produced and mixed by Andrew Liles in September 2012 • Hepton Stall, UK

Natt Wason ~ electric guitar

Eliot Bates ~ oud

Peter Hook ~ bass

Larry Cassidy ~ voice

note ~ this version features also remixed sounds from the musicians involved in the previous Love Will Tear Us Apart version.

Larry Cassidy recorded in 2011 at West Orange • Preston, UK

Eliot Bates recorded in 2011 at Miq Productions • Trumansburg (NY), USA

www.oursweetestsongs.com

http://oursweetestsongs.bandcamp.com

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Vaughan Williams – Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910)

From Psalm 2, as translated in Archbishop Parker’s 1567 psalter;

Why fumeth in sight: The Gentils spite,

In fury raging stout?

Why taketh in hond: The people fond,

Vayne thinges to bring about?

The kinges arise: The lordes devise,

In counsayles mett thereto:

Agaynst the Lord: With false accord,

Against his Christ they go.

Most incredibly, Vaughan Williams was able to take something very old, something as archaic as a Renaissance era modal hymn, and transform it into a remarkable work that feels timeless. Not to say that the Tallis hymn melody isn’t already remarkable; written in the Phrygian mode, the work modulates modally and so creates a somewhat uncomfortable reaction, where the music doesn’t “go” where you expect it “should”, and yet where it does go is satisfying and logical. And there is a deep pathos in this short tune, it is no wonder Vaughan Williams was so attracted to the work. The work is written for a three part expanded string orchestra, the first part is full sized, the second part is a smaller number of the same ensemble, and the third is a string quartet. His intention was to recreate the sonorities of a pipe organ. Following the “archaic” model, it is written as an Elizabethan fantasy, where the main theme and its original harmony is heard a few times but the material surrounding it is developed out of parts of the main theme. This creates an overall feel of rising and falling, a build up to the presentation of the main theme, and then melting away into a free flowing sound world that reacts to it. And maybe this is too ‘extra musical’ but I can’t help imagine a foggy day and seeing deer slightly out of sight and running away into the grey cloud.

#Vaughan Williams#fantasia#tallis#Thomas Tallis#music#classical#string orchestra#violin#viola#cello#bass#violin music#viola music#cello music#bass music#string orchestra music#orchestral fantasia#postromanticism#postromantic music#modernist#modernism#modernist music#fantasia on a theme by thomas tallis#Vaughan Williams fantasia on a theme by thomas tallis#Ralph Vaughan Williams

59 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Rachmaninoff – Cello Sonata in g minor (1901)

This was the first major work that Rachmaninoff wrote after overcoming a severe depressive episode. If you haven’t heard the story; when Rachmaninoff was first staring out as a composer, he wrote a symphony to act as his major ‘breakthrough’ piece. But the premiere was terrible [most likely because Glazunov, who conducted at the premiere, was a drunken mess], and the negative reception was so bad that Rachmaninoff internalized it as his own inability to write music. And I think this kind of bleak hopelessness, this feeling that you have nothing in your life that you are good at, or that you aren’t enough, can be felt in the opening bars of the sonata. The cello and the piano echo each other softly, shaping out the harmony, sparse texture compared to what Rachmaninoff is usually known for. The cello drags the melody out, the piano is icy. After the short intro, the piano breaks out in the allegro, the cello playing the main melody over a flurry of notes. The rhythm of the opening, two pulses of three beats, is woven into the entire movement. The softer melody that comes next is very nostalgic. The two instruments work together with the melody, passing it to each other gracefully. After the repeats, the transition section acts as a buildup of suspense, making you wait for an explosion that never comes. Instead, the main beat comes in the piano’s bass like the beginning of a march. The recapitulation has impressive piano work; heavy chords and quick flurries of notes. The nostalgic melody returns for a moment, but the coda races back to drama and ends with a restatement of the three-note pulse. The scherzo movement has the expected pianistic fireworks, and interesting enough the pulse comes back in the cello underplaying the melody. The soft lyrical melody that comes next is heartfelt and yearning. The middle of the movement has a beautiful passage between the instruments where the piano has delicate decorations under the cello’s songlike melody. The slow movement opens darkly, but quickly shifts into light, and it feels like a lullaby, except the minor key nudges its way in every so often. And again, the pulse returns, now a soft motif that opens the phrase. The cello singing with the piano makes this movement one of Rachmaninoff’s great melodies. The last movement opens with the piano in a quick burst of joy, the two play along with the exuberant mood. Even though Rachmaninoff is most well-known for the darkness in his music, I think he is at his best when he writes happy music, because it is unbridled exuberance and joy. There are dramatic interruptions and flourishes, but the mood stays upbeat all the way toward the coda, where we start to die down a bit and it feels like it will be a soft meditative ending, both instruments at their lower registers, but he brings the energy right up again and shoots for the stars. Before, feeling hopeless and void of spirit, now triumphing over sickness to begin the rest of an iconic career.

Movements:

1. Lento - Allegro moderato

2. Allegro scherzando

3. Andante

4. Allegro maestoso

#Rachmaninoff#Rachmaninov#cello#sonata#music#piano#classical#chamber#chamber music#classical music#piano music#cello music#cello sonata#Rachmaninoff cello sonata#Sergei Rachmaninoff#Sergei Rachmaninov#romantic music#postromanticism

120 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Rachmaninoff – Morceaux de Fantaisie, op.3 (1892)

I was going to make a post only on THE prelude today, but I remembered that I also adored the elegy, and I thought I may as well talk a bit about the full suite. “Fantasy Pieces”, again following the Romantic tradition of free-form music, was written by Rachmaninoff when he was just 19. Think of that! Usually when we talk about composers who wrote great stuff early on, we think Mozart or maybe Beethoven. But still a teenager, Rachmaninoff wrote a suite of gorgeous music, one of the pieces here would become his most popular and loved [to his chagrin]. He wrote the prelude first, and then the rest of the pieces came after, and he dedicated the suite to his teacher Anton Arensky. They are the accumulation of his studies, and show a shift towards a more mature style with craftsmanship and personality. The suite is not necessarily meant to be played as a group, and so you often hear the prelude as a stand-alone work. The opening Elegy starts off like a very darkened Chopin nocturne, and the main melody is full of the expected mourning and disturbingly tragic. This kind of darkness touches in on a lot of Rachmaninoff’s music. The melody sometimes sings out in one voice, sometimes another joins in harmony. And the music isn’t afraid to take sudden harmonic shifts. The middle section has an uplifting melody in the left hand as the right hand glitters over it. After an energetic transition, we come back to the bleak soundworld of the opening, the melody an octave lower. The coda grows louder with passionate descending thirds, and then the final bars go into the bass. The prelude is the most iconic work, and its popularity transcends the rest of the suite. Rachmaninoff was bothered by it the older he got, thinking that the love for the prelude of his teen years overshadowed ‘better’ music he wrote later. But it’s popularity is understandable. It opens with octaves going deep in the bass, part of the nickname “The Bells of Moscow”. They thunder underneath a main melody made up of thick homophonic chords, that has an almost yearning quality. The middle section is made of broken notes falling over each other chromatically, and eventually grows into a frantic passage of chords before exploding into a restatement of the opening, with dense chords slamming in the bass and then the hands jump to play the melody in full chords higher up. For clarity, the music here is written across four staffs. The intensity fills the room with immense pathos. That sounds like overkill with the adjectives maybe, but it does feel like music for an existential crisis. The music calms down a bit before dying away in softer chords, the bells ring out in the distance. After the angst of the opening, we are finally given a break in the form of the “melody”, which softly plays over gorgeous accompaniment, and as with the other works you hear premonitions of mature Rachmaninoff. Using chromaticism to murk up the harmonies, holding onto a gorgeous melody that seems to exist beyond the rhythm of the music, etc. The melody organically develops into an intense passage of chords that then break out into a pretty flourish, before coming back to the opening. The fourth movement, “Punchinella”, in reference to the same Commedia dell’arte character, is whimsical and full of joy, kind of foreshadowing Ravel’s “Alborada del gracioso”, and so with dense chords the music plays around on the keyboard. The middle section again has a main melody in the left hand while the right decorates over it, again keeping in the good mood but more genuine. Then we come back to the opening with its shifting grace notes and fun rhythm. The piece ends with staccato notes across the keyboard. The final work, the Serenade, opens with the melody alone, and comes off as “exotic” music, that is it follows folk writing scales that could be Spanish. It continues the brighter spirit that the second half of the suite has been carrying, while also dazzling with piano technique. Despite being in a minor key and ending with heavy chords, it is still a ‘happy’ piece.

Movements:

1. Elegie

2. Prelude

3. Melody

4. Polichinelle

5. Serenade

Pianist: Vladimir Ashkenazy

#Rachmaninoff#music#classical#morceaux de fantaisie#suite#piano#piano suite#classical music#piano music#prelude#romanticism#postromanticism#postromantic#Rachmaninoff morceaux de fantaisie#Rachmaninov#Rachmaninov morceaux de fantaisie#Rachmaninoff prelude#Rachmaninov prelude#Sergei Rachmaninoff#Sergei Rachmaninov

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Inktober 23 : Ancient #doodle #sketchbook#roughsketch #artistoninstagram#illustratoroninstagram #watercolorsketch #watercolorart #artistsofinstagram #inktober2019 #cute #fantasy #fantasyart #landscape #temple #ruins #postromanticism #instasketch #instaart #instaartist#instart #childrenillustration #inksketch #instadrawings #instadraw #fox #oldgod #forest #fall #nature https://www.instagram.com/p/B39EuRGoU7B/?igshid=1ca1kmh8f1ajm

#inktober#doodle#sketchbook#roughsketch#artistoninstagram#illustratoroninstagram#watercolorsketch#watercolorart#artistsofinstagram#inktober2019#cute#fantasy#fantasyart#landscape#temple#ruins#postromanticism#instasketch#instaart#instaartist#instart#childrenillustration#inksketch#instadrawings#instadraw#fox#oldgod#forest#fall#nature

1 note

·

View note