#preach pappy!!!!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

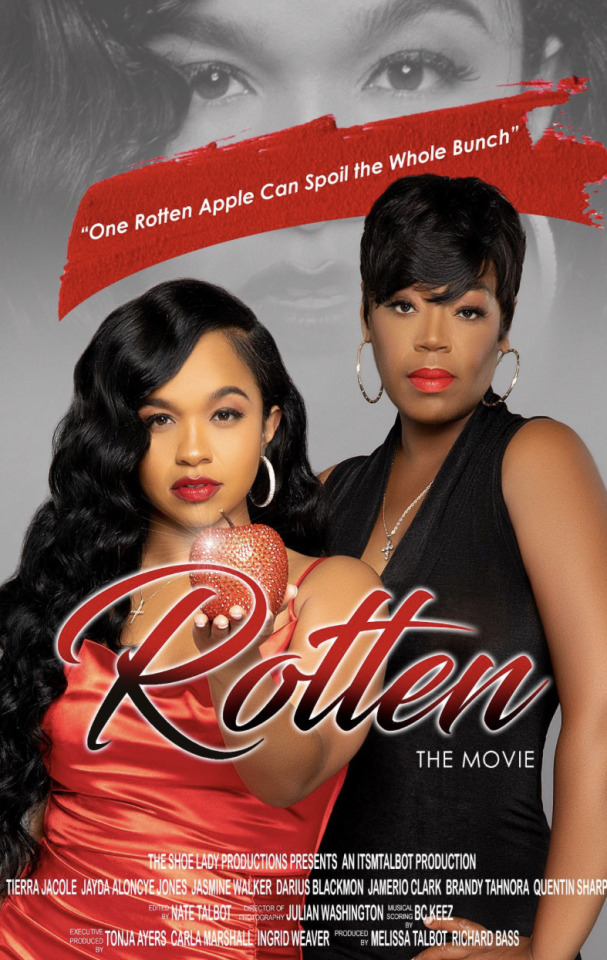

Commentary on the Tubi movie: Rotten

-somebody had a shopping spree at hobby lobby with all these signs

-Sis wasn't lying about homie being a bum

-not engage to a homeless nigga

-is she face timing T-Pain??

-what's going on???

-nothing wrong with loving your mother from a distance especially when she's toxic

-how are you a hairstylist and your man look destitute

-not sleeping with married men???

-let love into her life??? Sir why are you preaching to your mistress

-your wife is your world every day except for Wednesdays

-I'm confused was she taking down the braids on putting them in

-apple petty but she ain't lying about her mama

-Issac needs to stay out of their business

-shit parents ALWAYS NEED AN ORGAN🤣🤣

-once again apple ain't shit but she doesn't have to give her kidney to a mother that doesn't acknowledge the pain she caused

-girl what money have you got when you giving it to your homeless and jobless boyfriend

-one thing a broke nigga go do is keep a plan b aka another home to squat in

-sir I can't take you seriously with these glasses

-not his baby mama!!! Girl you dumb as hell

-girl ya man is a bum!!!

-she out here dating T-Pain

-oh they all got relationship issues

-apple about you sleep with Isaac

-🤣🤣🤣🤣🤣 she a damn fool

-girl tell them where Deon's bum ass at

-Baby the self-esteem in this family is lower than the earth’s core

-not he’s our man now!!😂😂

-Isaac is NOT a good man Savannah

-he has a point apple🥴

-I wonder if Isaac is Apple daddy??

-Apple is hella grimy was made that way

-the adulterer is judging and preaching to his mistress again🙃

-not her pulling this grey’s anatomy choose me love me line😂

-self-esteem has officially dropped to the south pole

-he working hard for this kidney

-black Carlos needs to take this bum out

-he not trying! I have yet to see him on Indeed jobs

-self-esteem #2 following right behind the other one

-not him stealing her identity

-HUSBAND???

-not him running

-she still defending this muskrat

-I completely agree you are a loser with that wide-ass part in that wig

-I’m so tired of this TD Jakes nigga

-not her throwing her bills away😂

-aww she gave her a booth at the shop🥹

-I hope T-ache is real

-Tami crawled so Tokyo Toni could walk

-Baby this is too much

-I wonder who the Pappy is

-I'm getting dizzy with this camera circling

-Issac gotta be her daddy

-not the adulterer catching feelings

-the wife is slow as well I see

-Deon out here dress like Fabo

-call black Carlos!!

-TD Jakes dresses like a new edition member...this is too much

-Black Carlos!!!

-Tami just tell that girl who her daddy is

-😱😱 this is the work of Tyler Perry

-the whole bloodline is trash my lawd

-they look to the sky for big Mama when she at the bottom looking up at them just burning

-not the whole salon knowing about her meet-up with T-ache

-is that a birth certificate I see👀👀

-i hope this man ain't a serial killer

-OH NO!!!! 😱😱

-Lawd this is too much

-I KNEW IT!!! She having a hills have eyes baby!!

-not the cousin dead Jesus 😱

-be pro-choice🤷🏽♀️

-this man fashions🙃

-not Tami popping up on Isaac

-Yaass Tami🔫🔫

Too much was going on but at least the plot was decent

3/5 stars

0 notes

Text

Eventually they go back to his place.

It’s a tiny walk up above a bagel shop, so the scent of freshly baked bread is overpowering, but not unpleasant.

Travis’s home is small and mostly barren. It’s as if he couldn’t think of any decorations to have, so he just didn’t bother. It’s full of nothing but practicalities – sofa, television, coffee table and the appropriate appliances.

Laura walks around wearing Travis’s police coat.

He always has it in his squad car just in case he needs it. Today, he needed it. It’s not exactly long enough to cover her, but it hides the bulk of her nudity.

However, she does find herself tugging on it, doing her best to hide the parts its poor at concealing – mainly her exposed privates and her ass.

Travis, for his part, keeps an eye out for any potential onlookers. He also shields her from view as much as possible. Once in his home, however, she relaxes considerably,

It makes him grin, feeling like a predator who has just caught their prey off guard. But he’s not going to attack just yet, still more concerned with her basic needs, “Are you hungry? Thirsty?”

She shakes her head in the negative and looks around, fingers dancing over his book shelves. It looks like she’s reading a few titles before moving on into his kitchen.

She spots some childish drawings with magnets holding them in place on the refrigerator – the only artwork she’s seen. There’s one that is – most likely - supposed to be Travis, a child’s handwriting above the clunky figure reading ‘Unkl Travus’.

The other picture has a different art style – this clearer, albeit no less immature. Each of the figures depicted in crayon have names labeled above their heads: Grammie, Pappy, Daddy, Mommy, Uncle Bobby, Uncle Travis, my brother, me.

Laura looks at both thoughtfully and Travis feels a little sheepish as he admits, “Yeah – the kids made those. Y’know, back when they were little. Caleb made this one. Kaylee here.”

He points to each in turn and Laura lets out a hefty breath, “They mean so much to you…”

Travis knows where this is going, “They do. But that doesn’t mean I regret my decision. I chose you. I’d choose you again. Don’t feel guilty about it.”

“Hard not to.” Laura turns so she can look directly at him, “I did appreciate their efforts…the children, in trying to free Silas. But after I got free during the fire and saw he’d bitten Caleb, we had to go. Again, I couldn’t trust-!”

“You’re preaching to the choir, Laura.” Travis huffs, “If anyone understands trust issues – it’s me.”

Laura nods and looks away from the pictures, “Still…wish we could have gotten the bone. Not to mention I now have no idea where Silas has gotten off to. I’m his guardian, his family, I watch out for him. Knowing he’s out there all alone…”

“Hey,” Travis tugs her forward, hugging her, “We’ll find him. Okay? We’ll fix this. Together.”

She nods, but he feels her burrow deeper into his chest. The way she’s doing so…it’s as if she’s starving for his touch, desperate for it.

What must it have been like for her? No doubt she’d been cooped up in some enclosed fish tank, a prison, always on display for gawking onlookers who doubted her authenticity or, even worse, poked fun at her for it.

…for fuck’s sake, even HE’D called her the ‘fish’ girl…

The thought makes his blood boil, but he just focuses on how good she feels in his arms. However, she eventually breaks away, asking softly, “Um…can I shower? I know that probably seems weird to ask after all the time we spent in the lake, but-!”

“No, it’s not strange.” He kisses her forehead, “Not if you need it.”

Laura’s lips twitch, “No more glasses, but still a cheesy dork.”

“I wear contacts now.”

“Mmm, do you?” she asks in good humor and Travis has to admit, he’s never felt this good himself. The more the memories settle in and the sharper they become, the more he realizes why he’s always felt so adrift.

Laura brought so much into his life – a sense of adventure and fun, things he’d never received from anyone else. True, he had good moments with both of his siblings, but neither of them compared to those days and nights he spent growing up alongside this girl – this woman.

After all, Laura may look like she’s in her twenties, but she’s truly closer to his own age and this thought sobers him some. What if he’s not good enough for her now? As old as he is.

She deserve a full life – a better one. He can only give her the time he has left. But, in so many ways, that’s better than no time at all and – while knowingly selfish – he wants that.

He wants her.

Travis hopes she wants it too, wants him too, and he promised her nothing but pleasure from here on out. A pleasure he plans to deliver as he gamely escorts her to his restroom with its glass encased shower.

A shower big enough for two.

A fact she’ll learn soon enough,

But, for now, he goes about innocently showing her the knobs and giving her toiletries and towels. Travis leaves the room and, as the shower head clicks on, he grins wickedly.

He’ll give ger a few minutes alone.

And then it’s ready for not, here he comes…

#hackearney#my writing#travis x laura#fin#back on my bullshit#this was written much longer#so im splitting it up#which means i might post another part later tonight

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

Oooh 14, 25 and 38?

I don’t know I mean there was like a few weeks back during church where my pappy was preaching and I suddenly remembered one of his old sermons and then it was either during that sermon or the next I can’t remember but he brought up that exact thing of sermon I had thought of and no I never spoke to him about it so hdhxhx wild

I didn’t feel like putting on new socks I wanna save them for when I shower tomorrow so I’m wearing old mismatched ones Jxhxhx one is black and one is dark grey

Uhm I’m not sure tbh I think the least amount of sleep I’ve gotten was like two hours or so one time ? I mean I stay up late pretty frequently but also I’ve been trying to get better about not doing it despite not having any real reason to fix my sleep schedule still jdhxhx

1 note

·

View note

Text

Everything People Said Would Happen If Elvis Danced On TV Has Happened

From rampant drug addiction, miscegeny, precipitous decline in education, complete moral degeneracy and sexual promiscuity to sky-rocketing rates of divorce, crime, venereal disease, and murdering unborn babies in the womb, literally every one of the most outrageous things raving lunatics said would happen if Elvis Presley were allowed to dance on The Ed Sullivan Show, has come to pass.

“It’s not as though some group of right-minded people sat down and thought about all the implications of television and pop music in some rational way, and then came to a conclusion about what reasonable likely outcomes might result” said UCLA chair of ethnomusicology and inveterate karaokist Mark Kligman. “No, what happened was precisely what only the MOST virulently raging lunatics and fundamentalists said would happen!”

“I ‘member when my Pappy burnt Elvis records, and preached that devil-music would cause men to marry horses, and women to murder their babies while they was still in the womb.” recalled Evangelical FedEx delivery driver Ray-Lee Jenkins. “At the time, ever’one said he were just crazy. Turns out, he were exactly right!”

University of California Sociologist Jessica Collett added “There doesn’t seem to be any scientific reason why rockabilly should be connected at all to utter social destruction, which is why it’s important for us to continue to harshly malign, belittle, and demonize every person who was right about that - especially religious people.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

0 notes

Text

Bernie Mac I'M Da Pappy Father'S Day T-Shirt

We are finally getting Bernie Mac I'M Da Pappy Father'S Day T-Shirt . Politicians that are in it for the people. And want what’s best for their constituents! Give the fat cats hell Pauline and Steve! who doesn’t want to do that hard thing in the do that big thing that feels like kinda an impossible thing. Yeah, do I hear you. Word of Life is launching a brand new web page to help people meet Jesus Christ. It’s Called Experience hope! We are all about the and reaching people so tell unsaved friends and family about the page or share this video. Help us preach the message of Christ to 7.5 million people this year. Thank you so much for your love and support during the loss of my your words are greatly appreciated and have lifted my heart at such a sad time. Naturally my followers span the world as well as many cultures, faiths, beliefs and religions. Bernie Mac I'M Da Pappy Father'S Day T-Shirt, hoodie, sweater, longsleeve and ladies t-shirt

Classic Women's

Long Sleeved

Unisex Sweatshirt

Unisex Hoodie

Classic Men's Hoodie, long-sleeved shirt, female tee, men's shirt, 3-hole shirt, V-neck shirt Bernie Mac I'M Da Pappy Father'S Day T-Shirt . Thank you for supporting Trendteeshirts. You're on your way and you don't have time to say "excuse me" to a bunch of riffraff. You're the king of this heap and they need to remember that. You don't have a superior attitude; you are superior. You act like you're better than everyone else because, well, you are. That's just a fact and if these revolting peasants don't like it, they can hit the high road, or rather the dirt road. The high road is yours. Wear this tee and keep them at arm's length where they belong. Say goodbye in style by wearing this tee that shows you have a sense of humor in any language. When you're giving the kiss-off to people, it's important to get your point across, and this tee leaves no doubt about your desire for certain individuals to hit the road. Give them the boot and leave them laughing all the way. You Can See More Product: https://trendteeshirts.com/product-category/trending/ Read the full article

0 notes

Text

And It Came To Pass In Those Days

23d December 1995, Lynch Mountain, Tempest, West Virginia For small creatures such as we the vastness is bearable only through love. _________ Carl Sagan, Contact

Throughout his life, Pappy was known by many names, but it was one Christmas Eve that he truly felt he earned the only one that really counted.

He began as Gustavus Simeon Lynch, but was very soon Gus. His birthname was too grandiose an appellation - it was given to him in gratitude by his father, Simeon, for Gustavus Olafsen, a Minnesotan of Swedish extraction who saved Simeon's life from the debacle onboard the USS San Diego during the Great War. But it proved too highfalutin for the boy who grew into a man.

That boy, Gus, was too often a cutup who disobeyed his Pa and had his hide tanned more times than he could count. He and his delinquent older cousin, Allen, would get drunk on badly-made shine out in the woods - they would play music together under the white oak on the other slope of the low mountain that belonged to their family, and Allen would tell him, hitting his fiddle with his bow gently to make a singular dulcet tone, Gus strumming his banjo to accompany, the old family legend that their ancestor, Patrick Lynch, had planted the great druid as but an acorn to mark his property when he came over from Ireland. Twice, Allen had kissed him passionately when they were both drunk - love, love, careless love - as Sodomites would, making him promise to never tell a soul, and though later in life Gus became concerned with both drink and sin, when he remembered those Summer afternoons underneath the mighty boughs of his family oak with his cousin, his first friend, his first love, all he could do was blush, and sigh, sad for bygone days. Years later, Gus heard that Allen, who married a girl he didn't love and fathered a child who grew up in the family as Cousin Bobby he didn't want, ended up going crazy and ripping out his own teeth, an eerie repeat of Gus' own father losing his teeth at a young age also. Hoping to be better than a backwoods moonshiner who did furtive and sinful things, the boy, Gus, became a man, with a new name to match: Private First Class Gus S. Lynch, Company E, 31st Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. He and his boyhood friend from Quinwood, Ralph Pomeroy, were shipped off during the Korean Conflict, where they stuck together because their fellows mocked their thick accents and yokel way - slights that he, Gus, never forgot or forgave. But, soon enough, there was that hopeless situation at a place that history would remember as Triangle Hill - Gus was one of the key witnesses to Ralph Pomeroy's dauntless actions that led his friend to be awarded, posthumously, the Medal of Honor. Then and there - seeing Ralph E. Pomeroy dedicate himself to something so completely larger than himself - Gus determined that he, too, would dedicate himself to something, and he fell on his knees, beseeching the sky above him, to say that he would devote his life to God. Soon, though he wouldn't care much for it, he became Corporal Gus S. Lynch, Silver Star Medal, but he scarcely remembered those October days in 1952 - his bright blue eyes, remarked on by his superior officers, always blurred by the tears as only men put through that awful fire can understand, blinded by dust and smoke...as though possessed, he dragged what injured he could, the same men who mocked him for being a hillbilly and who would pointedly ask if he was born in a coalmine or if he wore shoes but whom he swore to protect nonetheless, back to the medic tent, again and again and again, no man left behind. There were gruesome spectacles that would make any man doubt the sanity of the world, and still a lesser man repulsed by humans for the rest of his life, but Gus was swallowed in humility by his friend's actions and he wanted to somehow be brave himself - not for himself, but for the spirit he saw Ralph Pomeroy summon. And for these courageous actions - that he never, not once, felt courageous for - he had a Silver Star pinned to his breast by General van Fleet. When he returned home, honorably discharged back to West Virginia and back to the mountains, he wanted to make good on the promise he had made to the Almighty for saving him in Korea, and so he took the G.I. Bill money and crossed the border to Virginia to attend Bluefield College, where he read the Theology he would need to preach the Good Word and save souls for the Lord. In time he graduated, and he took still yet another name: Reverend Gus Lynch - he grew the thick, handsome chinstrap beard he would wear for the rest of his life, and, taking inspiration from the travelling preachers that comprised many of his proud ancestors, he rambled up and down the Appalachians in his big white Surburban, praising Jesus and baptizing the anointed, down to the river to pray, studying on that Good Old Way. Two fateful things happened as he journeyed from place to place, filling the spiritual needs of the wayward. The first was in Pennsylvania and not too long after New York, because they happened so close together. There, the people gave him names too, but this time they were bigoted slurs: redneck and hillbilly and inbred, they mocked his accent and his manners and his earnestness, so that Gus found himself rather like Jonah, wishing that these Yankees, like Nineveh, would perish rather than find salvation. He never forgot how those prejudiced Northerners treated him, treated him different, simply because of who he was and where he was born - he had met kind Negros, strong in the Lord and the love of their families, down in the Carolinas, and he knew they had it far worse than he did, but that made him all the more bitter, how man could treat his fellow man, regardless of how he spoke the English tongue, or even the color of his own skin. This led to the second event: one night at a revival in Summersville, having returned to West Virginia feeling he should go back to put down roots in Tempest - soured forever on the idea of rambling after his experiences up North - he met a beautiful little slip of a girl, dark-headed with soft grey eyes, who had a ready and sarcastic wit. Her name was Iris - Iris McComas, named for where her people had settled in that tiny coal town in McDowell County, many, many years ago. She was the prettiest thing in the room, with the purple-and-gold silk corsage she wore of her namesake, an iris...Gus' eyes followed her everywhere, finally, he got up the nerve, and he asked her to dance, and soon they got to talking. "Ye were in Korea?" asked she.

"I were," answered he. "Served with Ralph Pomeroy."

"Oh my, he was a hero."

"He was."

"If the army had more Pomeroys we'd've won that war."

Gus' expression turned serious. "We did have an army of Pomeroys - but y'only hear bout the famous ones."

"What a sad thing ta say - are ye a sad man, Mr. Lynch?"

"When the occasion calls fer it, my dear."

"My dear?" She gasped, pretending to be offended. "How forward!"

"Well then what would ya like me to call ye?" He gave that famous smirk, a crooked half-smile that many people knew him by. "My doe?" She burst out laughing. "Sly, too! My word, I can scarcely tell what kind o'man y'are - are y'always like this, Mr. Lynch? A man of God but a mystery ta women?"

"When the occasion calls fer it--" The smirk grew. "My dear." It was mid-December and the stars outside shone diamondiferous to join with the lavender half-moonlit snow - the congregation gathered together before they dispersed to sing one more hymn: Go! Tell it on the mountain! Our Jesus Christ is born! And as they stood together to sing, Iris put her hand in his. They took to courting, and soon were married, a fairytale, and they gave each other twenty-four of the happiest years of each others' life - they moved back together to Tempest where Gus became senior pastor of Living Hope Baptist Church. But it did not begin auspiciously. When Gus passed his thirty-fifth year, he was beset with toothaches that would not go away, wracked with pain that no medication or herbs would seem to salve. This went on for a week straight, until - one night - and to his horror, he found his eyeteeth, both of them, were being pushed out by something new in their place...when Iris came into their bedroom she flung her hands to her mouth as he turned to her so that she could see: for in his mouth were two, long, sharpened, canine fangs. Gus had always been aware of the morbid stories, the haints and the phantom creatures and the deep, shadowy weirdness that crawled all over Tempest, all over Adkins County - there were family legends for nearly each of the little clans that called this obscure corner of the Greenbrier Valley home, the Barnes and the Lightfoots and his own family, the Lynches...but he never thought that he would be privy, let alone part, of his own ghost story, his own monster-tale. Now he understood - now he understood the story about Cousin Allen, ripped out his own teeth and had taken to the drink too hard and died pitifully young...now he understood why his own father had a set of ivory chompers rather than what God gave him. Some malign ancestral curse had curdled in his blood and manifested itself as a hideous mutation of the mouth, something that made him look for all the world like a creature of the woods more than what he was - a man adapted for hunting and timber and subsistence living now reabsorbed by the forest he so loved to be a haint, a creature, bewitched and obscene to the world of men. At first Iris tried to help by filing his new additions down, blunting them so people would not notice - but horrible to relate, night after night, the things grew back, sharpened themselves to points as a form of growth. Several times they tried this, panicked husband and supportive wife - several times they were thwarted, right back to where they were. Desperate, and without recourse, they did, together, the only thing they thought left - even though he had not drank in years, Gus procured some fine whiskey from his friend, Ironside Lightfoot, guzzled it down until he was three sheets in the wind, and instructed his wife to take a wrench and do the unthinkable. When she was done, the teeth kept in a small box under his bed to remind him that this was not some kind of hideous vision sent to him from a Hellish delirium, near-feverish with pain and drink, and his mouth full of bloody cotton gauze, he looked on his wife with tears streaming forth from those uniquely blue eyes, begging her to forgive him for whatever sin he had done that had led him to be changed, however momentarily, into a monster. "Oh Iris - woman - what ye must think o'me - what kinda man I am--" "Gustavus Lynch," Iris answered without hesitation, "I know exactly what kinda man y'are." "N'what--" he was scared to finish the question. "What kinda man that be?" She said nothing - she just hugged him tight, and reached for his hand, taking it and squeezing it close to her own heart. They passed this crisis together as husband and wife, and with new teeth, dentures, procured from a dentist down in Roanoke, their life resumed its sunny way. Never did they talk about it, not once, even when Gus was troubled, year after year on the same day ever since, by quare visions of icy blue streams deep underground...when he would awake, dazed and vulnerable in the dead of night when nightmares seem realest, he would feel for his wife's hand, grasping her fingers into his own to feel grounded and unfraid once again. When they built their big house on Simeon Lynch's ancestral lands, on the day they knew their hard work was finished, she put her hand in his and squeezed it - when it became apparent she was with child, and told him the news, she took both of his hands and brought them to her belly... when she was in labor and he prayed over her, his heart full of joy and fear, she squeezed his hand again, as hard as she could - when the infant boy, who they named Gustavus after his father and so went through life as Junior, reached manhood and brought home a kind, mousey girl from Wetzel County to introduce as his fiancée, she squeezed his hand once more. They were blessed to have lived so full and fruitful, all those years together. But it all did not last. After, soon after, Iris contracted cancer of the breast, and she fell very ill very suddenly, she wasted away and was in great pain, such that there was nothing the doctors in Charleston could do. On her deathbed, she put her hand in Gus' one last time, and she said to him: "Oh, I finally know what kinda man y'are, Mr. Lynch." And with his eyes once again blurred with tears as they had been all those years ago in Korea, Gus answered: "N'what kinda man that be - Ms. McComas?" "Why - yer the man who loves me..." Then her hand slackened, it fell away - Gus' hand was empty, and she was gone. Gus knew he would never get over her and indeed he never did, and for years after would regard the day of her death - a clear, azure-skied day in October - as little short of cursed. Every year on her birthday, on the anniversary of their marriage, and to commemorate the day she died, he would pace up the side of his mountain and lay by her graveside, with space for him to be buried beside her when his time came, a bundle of her namesake, amethyst and gold - iris. One night, a year or two after her passing, driving back to the house that he and Iris had built and which now stood lonely and empty without her in it, Gus parked his Jeep that he had gotten by trading in his old Suburban on the side of a dirt road - he got out, and took a look, on a whim, above him, to the Winter stars. He had wrestled and grappled with the questions - theologically, spiritually, even psychologically - and still he had come up empty, empty as the indigo spans that one would have to traverse to get from star to star, how to properly mourn, how to properly grieve. And then he knew. He just - knew, somehow, a revelation, an epiphany, that she was up there...he knew, somehow, that in the crystalline twinkling of the stars, the same stars that twinkled just the same way the night they met, that she was watching. And - that she would not want him to be like this, not after all this time, all this wasted energy trying and wishing and praying for things that could no longer be. So he got back in his car, laid across the steering wheel and wept, one last time, and he let the heavens have her, let her watch over him and never let him go. Even after this the grief he felt never went away, but it was eased some after Junior had his own son, Gus' grandson, born en caul and destined for either second-sight or greatness or both, named Bligh after a distant patrilineal descendant - he had been too afraid to ask his son about his teeth, if it what happened to Gus had happened to Junior, but he was told by Susan Anne he had needed dentistry to fix some kind of abnormal growth...and knew the unspoken truth. Too soon, tragedy roared back into his life, another October day, this time grey and rainy, when Junior and his wife, Susan Anne, died in a car crash - Junior's Eldorado had careened off a sharp turn, killing them both, with little Bligh Allen, who had just turned five, miraculously surviving in the backseat. It was all, all enough for Gus to invoke old Job, and to have his faith, so sure even before his conversion all those years ago, shook so hard he wondered if Hell could hear it: why, why after so many years of faithful service, would God curse him so? Was it not enough to rob from his beloved, for whose touch he pined every day for the rest of his life - now his son, now his daughter-in-law too? And if I am a Christian,

I am the least of all-- But this was how Gus would soon become Pappy, the name that stuck at first as a tease and thereafter as how he would be known forever after, even amongst folk in Tempest outside of his own family - because his grandson Bligh, started calling him that. Bligh had always been a strange child - the circumstances of his birth alone were the subject of some comment, not just being en caul but having to be delivered in Barnes' veterinary office because of a great and terrible storm that at last blew down that old druid that Gus and Allen would play music under, but this was joined with his oddly quiet nature, as though observing everything around him in a troublingly mature kind of way. He did not speak as other children did - when Archie Lightfoot, the latest scion of that storied family which antedated Gus' own and the son of Gus' friend Ironside had his own son, Andrew, he was, by contrast, a bright and happy child, a chatterbox whose constant babbles exasperated his father...yet Bligh remained uncomfortably quiet. Then, one day, Junior, passing the peculiar newcomer to Gus to hold, murmured in babytalk: "Go see ya Pappy, go see ya Pappy now--" And Bligh burst out, his first words, when he was safe in Gus' arms: "Pa-pee! Pa-pee!" Junior was dumbstruck - but Gus, Pappy, was transported with happiness. He had been his grandson's first word. But...when Bligh came to live with Gus after his parents died, he did not like it, and made it a point, in his own sullen preschool-age way, to let Gus know he did not like him, throwing monstrous tantrums - howling like a wolf, which Gus would shake his head the hardest at - throwing his toys, refusing to come out of his new room in Gus' house, except to hastily eat and then steal back upstairs. It was bad enough that because of this withdrawn, traumatized behavior at school it was recommended he'd be held back a year, but really it seemed like there was no way, no way at all, for Gus to get through to his grandson, damaged in his young existence by being robbed of his parents. Weeks turned into months - Gus tried to cope the best he could, Christmastide drew nearer and he did his yearly rituals, cleaning for Baby Jesus' birthday and putting up a fresh, fragrant pine for a Christmas tree, all while his grandson remained dangerously introverted and reclusive. And then, finally, it occurred to Gus - what had happened to him nearly a decade before, ruminating on how Iris was gone, and what Iris would have wanted, and where Iris still was. Little Bligh would have to somehow see the same thing. So, carrying that little hope in his heart that he could fix things that shone distant but clear like the Star of Bethlehem, with the memory of Pappy as the boy's first word, on the eve of Christmas Eve, Gus came into the boy's room, and instructed him in a firm voice to get on something warm, they were going to go outside. It took some doing - thrice more did he have to be told, and the last time in a loud clear voice that was almost a threat - but eventually little Bligh tumbled down the steps and, his grandfather putting a guiding hand on the small of his back, they came outside. Gus made sure that Bligh followed every step he took, so that he would not get lost - eventually they came down the mountain, a gentle slope that was easy to traverse up and down, and arrived just where Gus needed them to be. The night was a masterpiece of Appalachian Winter - silent, neither sound nor movement, with a light snow dusting the ground that made a faint crunch beneath the feet. The cold was not biting or unpleasant as there was no wind, so that there was only the rejuvenating crispness that enlivened the nerves and thickened the blood. They came to a great, ruined, rotting tree - the big druid that his ancestor had planted, where Gus and his cousin would play music together, and where Gus had his first kiss, all those wistful bygone years before. Gus gently took his grandson's wrist. "Ya seen this tree here, boy?" Bligh shook his head - Gus let go, kneeling to his level, pointing. "This tree here fell the day ye's born...n'yer great-great--" He paused, tittering to himself. "Well let's say a feller ye n'me's both related ta, waaay back when - he planted it!" A spark of something like recognition seemed to wash away the sulky stubbornness that had possessed the boy's face lo these many weeks. "Someone - we related ta?" Bligh asked, his voice quiet to match the night. "S'right," Gus affirmed with a grin. "Our ancestor - our family been here a long, long time, understand." Bligh nodded, slowly, as though absorbing what his grandfather was telling him. "I want ya ta see sumthin else, too--" Using his boot, Pappy kicked part of the hollowed-out trunk of the old druid-tree hard - there, on the inside, was a cluster of phosphorescent vegetation, an unexpected symphony of fulgently radiant light hiding in the tiny cavern of the oaken log. Bligh recoiled - he had never seen anything like it before in his life. "Wha - wha?!" "Walk while ye have the light," Gus pronounced resolutely. "Lest darkness come upon ye - see that there glow?" Bligh nodded, his eyes wide with amazement. "That there's foxfire - it shines right here on the Earth sometimes - like the stars shine up in Heaven." "H-Heaven?" Bligh asked, his voice suddenly hushed. "Like - where Ma and Pa live now?" Now it was Gus' turn to nod. "Yes, boy - yes indeed." He swept up his grandson to lift him up so that he could see the stars shining - Heaven - above them. As he held Bligh up and then set him on his shoulders, he called out in his loud, clear voice that he used at Living Hope:

"Consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained!"

Right as Bligh grabbed hold of Pappy's head to balance, and just Pappy had finished - he sucked in an amazed breath.

Of course he had seen the stars, and of course he had asked about them, but he had never - so like a little boy - understood, in focus, what infinity meant, what the constellations and asterisms and shapes of the heavens meant, what lay beyond his playroom and the kitchen and the trees and the backyard.

And it was the words of King James that made him understand - the Word of the Lord that Pappy knew and practiced and had a bon mot for, sometimes clever and sometimes poignant, since that terrible day in that faraway place of Korea when he had devoted his life to the Good News.

Bligh's eyes beheld the stars not for the first time, but for the first time that really mattered. "Them stars up ere, boy - lookin down on us - there's ya Ma n'Pa, up ere - there's ya Mamaw Iris, who ye never met, but who - who woulda loved ye all the same..." "They - up there?" "That's right boy - all of em, watchin over us." And then grandson murmured the first true words of coherence in months: "Pappy - I wish they wudn't up yonder - I wish they was here." "Well me too, boy - me too." He sighed, swallowing back a wave of emotion that came with the words. "But we down here, for the time bein - n'we gotta make the best o'what the Lord God gave us." He took a hand to reach up and stroke his grandson's cheek. "So happens - the Lord God gave me a little boy - a little boy named Bligh."

A long silence followed, which Gus gently broke: "Just like em stars bove us shine, boy - n'like the foxfire aneath the log - I'll always shine fer ye. They watch over us up ere - but down here--" He let himself grin, for the first time in he couldn't remember approaching something like inner peace. "Down here - ain't nuthin gonna happen ta ye, long as I'm around - ain't nuthin ever gonna happen ta the boy the Good Lord gave me."

The Winter skies of West Virginia provide intangible proof in their starry voids of the ancient and the impossible, so that on a clear cold evening, with one's head tilted up to behold brumal Orion in the frigid air that turns the breath into the steamy vocabulary of Fafnir, it seems perfectly feasible that - on a night just like this - the Virgin Mary had a baby boy.

Go! Tell it on the mountain! O'er the hills and ev-ry-where!

And there was time enough for Lovecraft's mad spaces, and there was time yet still for Tyson's patient navigations, because there was time enough for little Bligh, already an orphan and doomed to a life against the grains of modernity, to understand the cruelty and the meanness of existence - but now he was wonderstruck, starstruck, at the cosmos that swirled above him in chilled clarity, the very Universe that Pappy's God in wisdom untold had designed and made, and so could he understand that this same cruel, mean place was also, at the very same time, full of kindness and love. "Pappy?" he heard his grandson whisper. "Yeah boy?" "I'm - I - I'm sorry..."

Now Gus - Pappy - felt that the wall that needed to come down had come down, now he knew that he could raise his grandchild and shelter him and protect him and guide him into manhood and carry on the Lynch name with honor and with pride and respect. Now - now Pappy lowered him down so that they were face to face, so that their identical eyes, gelid, frozen-over, but warm in this and all the Winters they would share together, now met. He pointed, down the mountain slope, the trees that twinkled with ice, and he whispered: "G'out with joy." He grinned an encouraging, knowing smile. "Be led forth with peace - the mountains -n'the hills shall break forth before ye into singin, and all the trees o'the field shall clap their hands..." He hugged his little grandson so tight he knew he would never forget. And right then, right that very second - everything was worth it. There had been a road here, there had been a journey undertaken, ever since Iris had blushed to see him watching her across the room at that little church in Summersville - ever since he had clutched Ralph's body in Korea and begged for him, screaming, to get up, to wake up - ever since he would join his cousin's melody on the banjo on those fine Summer days. They were all gone...but Bligh, his grandson, his blood, his flesh, his true legacy, was here. And of all the names, all the titles, all the ways he was or would be looked at - none of them would ever matter as much as the one that this serious, black-haired boy would foist upon him: "Pappy," little Bligh said again, and his eyes glimmered and became overfull with tears. Gus - Gustavus, Pappy - grinned at him, a full and proud smile, and kissed him gently on the cheek. "S'right boy," he whispered, but loud enough that the silent night of the approaching Christmas Eve allowed it to echo across time, space - and names. "I'm yer Pappy."

0 notes

Text

one last kylo analysis for now i guess

a few months ago i did a little explanation as to why i stanned kylo and after some time and much needed bts content, i feel as though i can put my finishing piece on my thoughts on the character.

for now at least.

well, i guess ill start this off by saying that i’ve just about played every star wars game and learned quite a bit about the extended uni so i can safely say this:

kylo ren is not a villain.

he only has the marketable look.

its easy to write him off as a villain after he X’d his poor pappy, but i’ve got to say, i’ve seen worse. mostly from the man he’s trying to emulate - Darth fuckin’ Vader. now, im not about to preach morals. im sure everyone reading this knows right from wrong (since according to anti’s, kylo stans do not) but Vader was a huuuuge dick in his prime. like, i see some anti’s bitch about kylo being a murderer but they’re quick to throw it back for Vad-oops, Anakin.

you see, i remember a guy called revan who more or less had the look of the big bad villain, and i thought, “wow, that guy looks fucking dope. i wanna be him!!”

*inserts conceited gif*

yeah, well, turns out, i was him the whole time, i just hit my head pretty fucking hard and got amnesia (hello memory loss au). and the entire game i was playing the big baddie and i could either get my redemption and save the galaxy, or stay the big baddie and be a total badass again.

TLDR;; star wars aint black or white. there are plot twists galore, and although its a lot harder now to surprise people, i think ants will be in for quite a surprise when kylo ren makes the inevitable side switch, and they end up willing to risk it all for him by the time the next trilogy comes out and we have a new edgelord to deal with. who of course, they will more than likely slander.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Mudbound' is the best movie Netflix has released so far — and you can watch it today

Steve Dietl/Netflix

Dee Rees' "Mudbound" is one of the best movies of the year.

It's also the best movie Netflix has released to date.

The ensemble cast is terrific, but Jason Mitchell proves he's one of the best up-and-coming actors working today.

Writer-director Dee Rees has been a shining star in the independent film world for years now, having given us movies like her striking debut feature “Pariah” in 2011, about a black Brooklyn teenager struggling with her gay identity, and the 2015 HBO biopic “Bessie,” about legendary blues artist Bessie Smith. But it’s her latest movie that will make her a known name in the mainstream.

“Mudbound,” which received high acclaim at this year’s Sundance Film Festival before being snatched up by Netflix for $12.5 million (it will play in theaters and be available on the site Friday), is a gripping work that looks at life on a rural Mississippi farm in post-World War II America. But it also contains themes of race and class that are sadly still very relevant in today’s world.

The movie is fueled by its perfect cast — which includes Carey Mulligan, Jason Mitchell, Jason Clarke, Garrett Hedlund, and Mary J. Blige — rich cinematography, and tender screenplay cowritten by Rees and Virgil Williams (adapted from the Hillary Jordan novel of the same name). It opens on a Mississippi farm with brothers Henry (Clarke) and Jamie (Hedlund) digging the grave for their recently departed father (Jonathan Banks) in the middle of a downpour. Jamie has cuts and bruises on his face, while Henry is conflicted about burying his father among the chains and bones of slaves they’ve uncovered while digging the deep grave.

We aren’t aware of the significance of any of these things, or why the black family in a carriage that Henry waves down to help with the burial looks so upset at him for asking. But in the next few hours it will all make sense.

“Mudbound” is a story about dreams that go unfulfilled, and how hatred that goes back generations can’t be mended by a single friendship. But mostly it’s about family: for one character it’s all he has, while for another it’s what he’s been trying to run from his whole life.

The two families the movie centers on are the McAllans and Jacksons. Henry McAllan, his new wife Laura (Mulligan), and his father Pappy (Banks) have all packed up and moved from the city to Mississippi to become farmers. Just down the road, Hap Jackson (Rob Morgan), his wife Florence (Blige), and their kids try to build a life of their own with their cotton crop, working on land McAllan owns.

NetflixThis part of the movie is heightened by the work of character actor Rob Morgan, known best for his roles on Netflix shows “Luke Cage” and “Stranger Things." He plays Hap as a proud man struggling to make a better life for his family, though all he knows is back-breaking work on the farm. Preaching in a half-built church on Sundays, and then tending to his cotton the rest of the week, we feel his pain through his heartbreaking voiceovers. One touching voiceover on the worth of a deed — playing on the word's dual meaning as a "good deed" or a "deed" to land — is delivered in a way by Morgan that will leave you with goosebumps.

The story then shifts abroad to the family's boys battling in World War II. Jamie McAllan (Hedlund) is a pilot and Ronsel Jackson (Jason Mitchell) is a tank commander. Both see a lot of awful things, and lose buddies, but Ronsel also realizes that on the field of battle, and to those he’s liberating, the color of his skin means nothing.

Both come home to Mississippi and form an instant bond as they suffer from different forms of PTSD. But Ronsel also has to deal with racism as soon as he gets off the bus. Things get worse when Ronsel crosses paths with Pappy, leading to a riff between the families, and to Ronsel suddenly having a target on his back among the white supremacists in the area.

However, Jamie and Ronsel’s bond grows even stronger. The two sneak away to have mid-day drinks and talk about the war. Ronsel even reveals to Jamie that he’s learned that he has a child back in Germany from the woman he fell for over there.

But things turn bad when Pappy realizes Jamie and Ronsel have been hanging out, leading to the appearance of the Ku Klux Klan and some very tough scenes to watch.

Rees captures this time in America with an unforgiving eye, which is essential to the story.

And though the story is heavily an ensemble work, it’s Mitchell’s performance as Ronsel that shines through. He’s has already wowed us playing Easy-E in 2015’s “Straight Outta Compton,” but here Mitchell proves that he’s one of the best up-and-coming talents in Hollywood today. It honestly will be criminal if Mitchell doesn’t receive an Oscar nomination for his work in “Mudbound.”

Hopefully Netflix plays somewhat by the rules to give “Mudbound” a chance to be eligible for Oscar consideration because it is pound-for-pound the best movie Netflix has released so far in its existence.

Youtube Embed: http://www.youtube.com/embed/xucHiOAa8Rs Width: 560px Height: 315px

NOW WATCH: Sean Astin describes one thing you probably never knew about 'The Goonies'

from Feedburner http://ift.tt/2mB3Iob

1 note

·

View note

Link

'Mudbound' is the best movie Netflix has released so far — and you can watch it today Steve Dietl/Netflix Dee Rees' "Mudbound" is one of the best movies of the year. It's also the best movie Netflix has released to date. The ensemble cast is terrific, but Jason Mitchell proves he's one of the best up-and-coming actors working today. Writer-director Dee Rees has been a shining star in the independent film world for years now, having given us movies like her striking debut feature “Pariah” in 2011, about a black Brooklyn teenager struggling with her gay identity, and the 2015 HBO biopic “Bessie,” about legendary blues artist Bessie Smith. But it’s her latest movie that will make her a known name in the mainstream. “Mudbound,” which received high acclaim at this year’s Sundance Film Festival before being snatched up by Netflix for $12.5 million (it will play in theaters and be available on the site Friday), is a gripping work that looks at life on a rural Mississippi farm in post-World War II America. But it also contains themes of race and class that are sadly still very relevant in today’s world. The movie is fueled by its perfect cast — which includes Carey Mulligan, Jason Mitchell, Jason Clarke, Garrett Hedlund, and Mary J. Blige — rich cinematography, and tender screenplay cowritten by Rees and Virgil Williams (adapted from the Hillary Jordan novel of the same name). It opens on a Mississippi farm with brothers Henry (Clarke) and Jamie (Hedlund) digging the grave for their recently departed father (Jonathan Banks) in the middle of a downpour. Jamie has cuts and bruises on his face, while Henry is conflicted about burying his father among the chains and bones of slaves they’ve uncovered while digging the deep grave. We aren’t aware of the significance of any of these things, or why the black family in a carriage that Henry waves down to help with the burial looks so upset at him for asking. But in the next few hours it will all make sense. “Mudbound” is a story about dreams that go unfulfilled, and how hatred that goes back generations can’t be mended by a single friendship. But mostly it’s about family: for one character it’s all he has, while for another it’s what he’s been trying to run from his whole life. The two families the movie centers on are the McAllans and Jacksons. Henry McAllan, his new wife Laura (Mulligan), and his father Pappy (Banks) have all packed up and moved from the city to Mississippi to become farmers. Just down the road, Hap Jackson (Rob Morgan), his wife Florence (Blige), and their kids try to build a life of their own with their cotton crop, working on land McAllan owns. Netflix This part of the movie is heightened by the work of character actor Rob Morgan, known best for his roles on Netflix shows “Luke Cage” and “Stranger Things." He plays Hap as a proud man struggling to make a better life for his family, though all he knows is back-breaking work on the farm. Preaching in a half-built church on Sundays, and then tending to his cotton the rest of the week, we feel his pain through his heartbreaking voiceovers. One touching voiceover on the worth of a deed — playing on the word's dual meaning as a "good deed" or a "deed" to land — is delivered in a way by Morgan that will leave you with goosebumps. The story then shifts abroad to the family's boys battling in World War II. Jamie McAllan (Hedlund) is a pilot and Ronsel Jackson (Jason Mitchell) is a tank commander. Both see a lot of awful things, and lose buddies, but Ronsel also realizes that on the field of battle, and to those he’s liberating, the color of his skin means nothing. Both come home to Mississippi and form an instant bond as they suffer from different forms of PTSD. But Ronsel also has to deal with racism as soon as he gets off the bus. Things get worse when Ronsel crosses paths with Pappy, leading to a riff between the families, and to Ronsel suddenly having a target on his back among the white supremacists in the area. However, Jamie and Ronsel’s bond grows even stronger. The two sneak away to have mid-day drinks and talk about the war. Ronsel even reveals to Jamie that he’s learned that he has a child back in Germany from the woman he fell for over there. But things turn bad when Pappy realizes Jamie and Ronsel have been hanging out, leading to the appearance of the Ku Klux Klan and some very tough scenes to watch. Rees captures this time in America with an unforgiving eye, which is essential to the story. And though the story is heavily an ensemble work, it’s Mitchell’s performance as Ronsel that shines through. He’s has already wowed us playing Easy-E in 2015’s “Straight Outta Compton,” but here Mitchell proves that he’s one of the best up-and-coming talents in Hollywood today. It honestly will be criminal if Mitchell doesn’t receive an Oscar nomination for his work in “Mudbound.” Hopefully Netflix plays somewhat by the rules to give “Mudbound” a chance to be eligible for Oscar consideration because it is pound-for-pound the best movie Netflix has released so far in its existence. Youtube Embed: http://www.youtube.com/embed/xucHiOAa8Rs Width: 560px Height: 315px NOW WATCH: Here's why people are afraid of clowns — and what you can do to get over it November 17, 2017 at 02:04PM

0 notes

Text

And It Came To Pass In Those Days

December 23d, 1996, Lynch Mountain, Tempest, West Virginia For small creatures such as we the vastness is bearable only through love. _________ Carl Sagan, Contact Throughout his life, Pappy was known by many names, but it was one Christmas Eve that he truly felt he earned the only one that really counted.

He began as Gustavus Simeon Lynch, but was very soon Gus. His birthname was too grandiose an appellation – it was given to him in gratitude by his father, Simeon, for Gustavus Olafsen, a Minnesotan of Swedish extraction who saved Simeon's life from the debacle onboard the USS San Diego during the Great War. But it proved too highfalutin for the boy who grew into a man. That boy, Gus, was too often a cutup who disobeyed his Pa and had his hide tanned more times than he could count. He and his delinquent older cousin, Allen, would get drunk on badly-made shine out in the woods – they would play music together under the white oak on the other slope of the low mountain that belonged to their family, and Allen would tell him, hitting his fiddle with his bow gently to make a singular dulcet tone, Gus strumming his banjo to accompany, the old family legend that their ancestor, Patrick Lynch, had planted the great druid as but an acorn to mark his property when he came over from Ireland. Twice, Allen had kissed him passionately when they were both drunk – love, love, careless love – as Sodomites would, making him promise to never tell a soul, and though later in life Gus became concerned with both drink and sin, when he remembered those Summer afternoons underneath the mighty boughs of his family oak with his cousin, his first friend, his first love, all he could do was blush, and sigh, sad for bygone days. Years later, Gus heard that Allen, who married a girl he didn't love and fathered a child who grew up in the family as Cousin Bobby he didn't want, ended up going crazy and ripping out his own teeth, an eerie repeat of Gus' own father losing his teeth at a young age also. Hoping to be better than a backwoods moonshiner who did furtive and sinful things, the boy, Gus, became a man, with a new name to match: Private First Class Gus S. Lynch, Company E, 31st Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division. He and his boyhood friend from Quinwood, Ralph Pomeroy, were shipped off during the Korean Conflict, where they stuck together because their fellows mocked their thick accents and yokel way, slights that he, Gus, never forgot or forgave. But, soon enough, there was that hopeless situation at a place that history would remember as Triangle Hill – Gus was one of the key witnesses to Ralph Pomeroy's dauntless actions that led his friend to be awarded, posthumously, the Medal of Honor. Then and there – seeing Ralph E. Pomeroy dedicate himself to something so completely larger than himself – Gus determined that he, too, would dedicate himself to something, and he fell on his knees, beseeching the sky above him, to say that he would devote his life to God. Soon, though he wouldn't care much for it, he became Private First Class Gus S. Lynch, Silver Star Medal, but he scarcely remembered those awful October days in 1952 – his bright blue eyes, remarked on by his superior officers, always blurred by the tears as only men put through fire can understand, and blinded by fire and dust and smoke…as though possessed, he dragged what injured he could, the same men who mocked him for being a hillbilly and who would pointedly ask if he was born in a coalmine or if he wore shoes but whom he swore to protect nonetheless, back to the medic tent. There were gruesome spectacles that would make any man doubt the sanity of the world, and still a lesser man repulsed by humans for the rest of his life, but Gus was swallowed in humility by his friend's actions and he wanted to somehow be brave himself – not for himself, but for the spirit he saw Ralph Pomeroy summon. And for these courageous actions – that he never, not once, felt courageous for – he had a Silver Star pinned to his breast by General van Fleet. When he returned home, honorably discharged back to West Virginia and back to the mountains, he wanted to make good on the promise he had made to the Almighty for saving him in Korea, and so he took the G.I. Bill money and crossed the border to Virginia to attend Bluefield College, where he read the Theology he would need to preach the Good Word and save souls for the Lord. In time he graduated, and he took still yet another name: Reverend Gus Lynch – he grew the thick, handsome chinstrap beard he would wear for the rest of his life, and, taking inspiration from the travelling preachers that comprised many of his proud ancestors, he rambled up and down the Appalachians in his big white Surburban praising Jesus and baptizing the anointed, down to the river to pray to study on that Good Old Way. Two fateful things happened as he journeyed from place to place, filling the spiritual needs of the wayward. The first was in Pennsylvania and not too long after New York, because they happened so close together. There, the people gave him names too, but this time they were bigoted slurs: redneck and hillbilly and inbred, they mocked his accent and his manners and his earnestness, so that Gus found himself rather like Jonah, wishing that these Yankees, like Nineveh, would perish rather than find salvation. He never forgot how those prejudiced Northerners treated him, treated him different, simply because of who he was and where he was born – he had met kind Negros, strong in the Lord and the love of their families, down in the Carolinas, and he knew they had it far worse than he did, but that made him all the more bitter, how man could treat his fellow man, regardless of how he spoke the English tongue, or even the color of his own skin. This led to the second event: one night at a revival in Summersville, having returned to West Virginia feeling he should go back to put down roots in Tempest – soured forever on the idea of rambling after his experiences up North – he met a beautiful little slip of a girl, dark-headed with soft grey eyes, who had a ready and sarcastic wit. Her name was Iris – Iris Jones, whose family name had been something else afore her great-granddaddy had renamed them from an unpronounceable jumble of Cumbrian letters for a tiny coal town in McDowell County where the family had all settled many, many years ago. She was the prettiest thing in the room, with the purple-and-gold silk corsage she wore of her namesake, an iris…Gus' eyes followed her everywhere, finally, he got up the nerve, and he asked her to dance, and soon they got to talking. "Ye were in Korea?" asked she.

"I were," answered he. "Served with Ralph Pomeroy."

"Oh my, he was a hero."

"He was."

"If the army had more Pomeroys we'd've won that war."

Gus' expression turned serious. "We did have an army of Pomeroys – but y'only hear bout the famous ones."

"What a sad thing ta say – are ye a sad man, Mr. Lynch?"

"When the occasion calls fer it, my dear."

"My dear?" She gasped, pretending to be offended. "How forward!"

"Well then what would ya like me to call ye?" He gave that famous smirk, a crooked half-smile that many people knew him by. "My doe?" She burst out laughing. "Sly, too! My word, I can scarcely tell what kind o'man y'are – are y'always like this, Mr. Lynch? A man of God but a mystery ta women?"

"When the occasion calls fer it—" The smirk grew. "My dear." It was mid-December and the stars outside shone diamondiferous to join with the lavender half-moonlit snow – the congregation gathered together before they dispersed to sing one more hymn: Go! Tell it on the mountain! Our Jesus Christ is born! And as they stood together to sing, Iris put her hand in his. They took to courting, and soon were married, a fairytale, and they gave each other twenty-four of the happiest years of each others' life – they moved back together to Tempest where Gus became senior pastor of Living Hope Baptist Church. But it did not begin auspiciously. When Gus passed his thirty-fifth year, he was beset with toothaches that would not go away, wracked with pain that no medication or herbs would seem to salve. This went on for a week straight, until – one night – and to his horror, he found his eyeteeth, both of them, were being pushed out by something new in their place…when Iris came into their bedroom she flung her hands to her mouth as he turned to her so that she could see: for in his mouth were two, long, sharpened, canine fangs. Gus had always been aware of the morbid stories, the haints and the phantom creatures and the deep, shadowy weirdness that crawled all over Tempest, all over Adkins County – there were family legends for nearly each of the little clans that called this obscure corner of the Greenbrier Valley home, the Barnes and the Lightfoots and his own family, the Lynches…but he never thought that he would be privy, let alone part, of his own ghost story, his own monster-tale. Now he understood – now he understood the story about Cousin Allen, ripped out his own teeth and had taken to the drink too hard and died pitifully young…now he understood why his own father had a set of ivory chompers rather than what God gave him. Some malign ancestral curse had curdled in his blood and manifested itself as a hideous mutation of the mouth, something that made him look for all the world like a creature of the woods more than what he was – a man adapted for hunting and timber and subsistence living now reabsorbed by the forest he so loved to be a haint, a creature, bewitched and obscene to the world of men. At first Iris tried to help by filing his new additions down, blunting them so people would not notice – but horrible to relate, night after night, the things grew back, sharpened themselves to points as a form of growth. Several times they tried this, panicked husband and supportive wife – several times they were thwarted, right back to where they were. Desperate, and without recourse, they did, together, the only thing they thought left – even though he had not drank in years, Gus procured some fine whiskey from his friend, Ironside Lightfoot, guzzled it down until he was three sheets in the wind, and instructed his wife to take a wrench and do the unthinkable. When she was done, the teeth kept in a small box under his bed to remind him that this was not some kind of hideous vision sent to him from a Hellish delirium, near-feverish with pain and drink, and his mouth full of bloody cotton gauze, he looked on his wife with tears streaming forth from those uniquely blue eyes, begging her to forgive him for whatever sin he had done that had led him to be changed, however momentarily, into a monster. "Oh Iris – woman – what ye must think o'me – what kinda man I am—" "Gustavus Lynch," Iris answered without hesitation, "I know exactly what kinda man y'are." "N'what—" he was scared to finish the question. "What kinda man that be?" She said nothing – she just hugged him tight, and reached for his hand, taking it and squeezing it close to her own heart. They passed this crisis together as husband and wife, and with new teeth, dentures, procured from a dentist down in Roanoke, their life resumed its sunny way. Never did they talk about it, not once, even when Gus was troubled, year after year on the same day ever since, by quare visions of icy blue streams deep underground…when he would awake, dazed and vulnerable in the dead of night when nightmares seem realest, he would feel for his wife's hand, grasping her fingers into his own to feel grounded and unfraid once again. When they built their big house on Simeon Lynch's ancestral lands, on the day they knew their hard work was finished, she put her hand in his and squeezed it – when it became apparent she was with child, and told him the news, she took both of his hands and brought them to her belly… when she was in labor and he prayed over her, his heart full of joy and fear, she squeezed his hand again, as hard as she could – when the infant boy, who they named Gustavus after his father and so went through life as Junior, reached manhood and brought home a kind, mousey girl from Wetzel County to introduce as his fiancée, she squeezed his hand once more. They were blessed to have lived so full and fruitful, all those years together. But it all did not last. After, soon after, Iris contracted cancer of the breast, and she fell very ill very suddenly, she wasted away and was in great pain, such that there was nothing the doctors in Charleston could do. On her deathbed, she put her hand in Gus' one last time, and she said to him: "Oh, I finally know what kinda man y'are, Mr. Lynch." And with his eyes once again blurred with tears as they had been all those years ago in Korea, Gus answered: "N'what kinda man that be – Ms. McComas?" "Why – yer the man who loves me…" Then her hand slackened, it fell away – Gus' hand was empty, and she was gone. Gus knew he would never get over her and indeed he never did, and for years after would regard the day of her death – a clear, azure-skied day in October – as little short of cursed. Every year on her birthday, on the anniversary of their marriage, and to commemorate the day she died, he would pace up the side of his mountain and lay by her graveside, with space for him to be buried beside her when his time came, a bundle of her namesake, amethyst and gold – iris. One night, a year or two after her passing, driving back to the house that he and Iris had built and which now stood lonely and empty without her in it, Gus parked his Jeep that he had gotten by trading in his old Suburban on the side of a dirt road – he got out, and took a look, on a whim, above him, to the Winter stars. He had wrestled and grappled with the questions – theologically, spiritually, even psychologically – and still he had come up empty, empty as the indigo spans that one would have to traverse to get from star to star, how to properly mourn, how to properly grieve. And then he knew. He just – knew, somehow, a revelation, an epiphany, that she was up there…he knew, somehow, that in the crystalline twinkling of the stars, the same stars that twinkled just the same way the night they met, that she was watching. And – that she would not want him to be like this, not after all this time, all this wasted energy trying and wishing and praying for things that could no longer be. So he got back in his car, laid across the steering wheel and wept, one last time, and he let the heavens have her, let her watch over him and never let him go. Even after this the grief he felt never went away, but it was eased some after Junior had his own son, Gus' grandson, born en caul and destined for either second-sight or greatness or both, named Bligh after a distant patrilineal descendant – he had been too afraid to ask his son about his teeth, if it what happened to Gus had happened to Junior, but he was told by Susan Anne he had needed dentistry to fix some kind of abnormal growth…and knew the unspoken truth. Too soon, tragedy roared back into his life, another October day, this time grey and rainy, when Junior and his wife, Susan Anne, died in a car crash – Junior's Eldorado had careened off a sharp turn, killing them both, with little Bligh Allen, who had just turned five, miraculously surviving in the backseat. It was all, all enough for Gus to invoke old Job, and to have his faith, so sure even before his conversion all those years ago, shook so hard he wondered if Hell could hear it: why, why after so many years of faithful service, would God curse him so? Was it not enough to rob from his beloved, for whose touch he pined every day for the rest of his life – now his son, now his daughter-in-law too? And if I am a Christian,

I am the least of all— But this was how Gus would soon become Pappy, the name that stuck at first as a tease and thereafter as how he would be known forever after, even amongst folk in Tempest outside of his own family. his grandson Bligh, started calling him that. Bligh had always been a strange child – the circumstances of his birth alone were the subject of some comment, not just en caul but having to be delivered in Barnes' veterinary office because of a great and terrible storm that at last blew down that old druid that Gus and Allen would play music under, but this was joined with his oddly quiet nature, as though observing everything around him in a troublingly mature kind of way. He did not speak as other children did – when Archie Lightfoot, the latest scion of that storied family which antedated Gus' own and the son of Gus' friend Ironside had his own son, Andrew, he was, by contrast, a bright and happy child, a chatterbox whose constant babbles exasperated his father…yet Bligh remained uncomfortably quiet. Then, one day, Junior, passing the peculiar newcomer to Gus to hold, murmured in babytalk: "Go see ya Pappy, go see ya Pappy now—" And Bligh burst out, his first words, when he was safe in Gus' arms: "Pa-pee! Pa-pee!" Junior was dumbstruck – but Gus, Pappy, was transported with happiness. He had been his grandson's first word. But…when Bligh came to live with Gus after his parents died, he did not like it, and made it a point, in his own sullen preschool-age way, to let Gus know he did not like him, throwing monstrous tantrums – howling like a wolf, which Gus would shake his head the hardest at – throwing his toys, refusing to come out of his new room in Gus' house, except to hastily eat and then steal back upstairs. It was bad enough that because of this withdrawn, traumatized behavior at school it was recommended he'd be held back a year, but really it seemed like there was no way, no way at all, for Gus to get through to his grandson, damaged in his young existence by being robbed of his parents. Weeks turned into months – Gus tried to cope the best he could, Christmastide drew nearer and he did his yearly rituals, cleaning for Baby Jesus' birthday and putting up a fresh, fragrant pine for a Christmas tree, all while his grandson remained dangerously introverted and reclusive. And then, finally, it occurred to Gus – what had happened to him nearly a decade before, ruminating on how Iris was gone, and what Iris would have wanted, and where Iris still was. Little Bligh would have to somehow see the same thing. So, carrying that little hope in his heart that he could fix things that shone distant but clear like the Star of Bethlehem, with the memory of Pappy as the boy's first word, on the eve of Christmas Eve, Gus came into the boy's room, and instructed him in a firm voice to get on something warm, they were going to go outside. It took some doing – thrice more did he have to be told, and the last time in a loud clear voice that was almost a threat – but eventually little Bligh tumbled down the steps and, his grandfather putting a guiding hand on the small of his back, they came outside. Gus made sure that Bligh followed every step he took, so that he would not get lost – eventually they came down the mountain, a gentle slope that was easy to traverse up and down, and arrived just where Gus needed them to be. The night was a masterpiece of Appalachian Winter – silent, neither sound nor movement, with a light snow dusting the ground that made a faint crunch beneath the feet. The cold was not biting or unpleasant as there was no wind, so that there was only the rejuvenating crispness that enlivened the nerves and thickened the blood. They came to a great, ruined, rotting tree – the big druid that his ancestor had planted, where Gus and his cousin would play music together, and where Gus had his first kiss, all those wistful bygone years before. Gus gently took his grandson's wrist. "Ya seen this tree here, boy?" Bligh shook his head – Gus let go, kneeling to his level, pointing. "This tree here fell the day ye's born…n'yer great-great—" He paused, tittering to himself. "Well let's say a feller ye n'me's both related ta, waaay back when – he planted it!" A spark of something like recognition seemed to wash away the sulky stubbornness that had possessed the boy's face lo these many weeks. "Someone – we related ta?" Bligh asked, his voice quiet to match the night. "S'right," Gus affirmed with a grin. "Our ancestor – our family been here a long, long time, understand." Bligh nodded, slowly, as though absorbing what his grandfather was telling him. "I want ya ta see sumthin else, too—" Using his boot, Pappy kicked part of the hollowed-out trunk of the old druid-tree hard – there, on the inside, as a cluster of phosphorescent vegetation, an unexpected symphony of fulgently radiant light hiding in the tiny cavern of the oaken log. Bligh recoiled – he had never seen anything like it before in his life. "Wha – wha?!" "Walk while ye have the light," Gus pronounced resolutely. "Lest darkness come upon ye – see that there glow?" Bligh nodded, his eyes wide with amazement. "That there's foxfire – it shines right here on the Earth sometimes – like the stars shine up in Heaven?" "H-Heaven?" Bligh asked, his voice suddenly hushed. "Like – where Ma and Pa live now?" Now it was Gus' turn to nod. "Yes, boy – yes indeed." He swept up his grandson to lift him up so that he could see the stars shining – Heaven – above them. As he held Bligh up and then set him on his shoulders, he called out in his loud, clear voice that he used at Living Hope:

"Consider thy heavens, the work of thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which thou hast ordained!"

Right as Bligh grabbed hold of Pappy's head to balance, and just Pappy had finished – he sucked in an amazed breath.

Of course he had seen the stars, and of course he had asked about them, but he had never – so like a little boy – understood, in focus, what infinity meant, what the constellations and asterisms and shapes of the heavens meant, what lay beyond the playroom and the kitchen and the trees and the backyard.

And it was the words of King James that made him understand – the Word of the Lord that Pappy knew and practiced and had a bon mot for, sometimes clever and sometimes poignant, since that terrible day in that faraway place of Korea when he had devoted his life to the Good News.

Bligh's eyes beheld the stars not for the first time, but for the first time that really mattered. "Them stars up ere, boy – lookin down on us – there's ya Ma n'Pa, up ere – there's ya Grandmamma Iris, who ye never met, but who – who woulda loved ye all the same…" "They – up there?" "That's right boy – all of em, watchin over us." And then grandson murmured the first true words of coherence in months: "Pappy – I wish they wudn't up yonder – I wish they were here." "Well me too, boy – me too." He sighed, swallowing back a wave of emotion that came with the words. "But we down here, for the time bein – n'we gotta make the best o'what the Lord God gives us." He took a hand to reach up and stroke his grandson's cheek. "So happens – the Lord God gave me a little boy – a little boy named Bligh."

A long silence followed, which Gus gently broke: "Just like em stars bove us shine, boy – n'like the foxfire aneath the log – I'll always shine fer ye. They watch over us up ere – but down here—" He let himself grin, for the first time in he couldn't remember approaching something like inner peace. "Down here – ain't nuthin gonna happen ta ye, long as I'm around – ain't nuthin ever gonna happen ta the boy the Good Lord gave me."

The Winter skies of West Virginia provide intangible proof in their starry voids of the ancient and the impossible, so that on a clear brumal evening, with one's head tilted up to behold cold Orion in the frigid air that turns the breath into the steamy vocabulary of Fafnir, it seems perfectly feasible that – on a night just like this – the Virgin Mary had a baby boy.

Go! Tell it on the mountain! O'er the hills and ev-ry-where!

And there was time enough for Lovecraft's mad spaces, and there was time yet still for Tyson's patient navigations, because there was time enough for little Bligh, already an orphan and doomed to a life against the grains of modernity, to understand the cruelty and the meanness of existence – but now he was wonderstruck, starstruck, at the cosmos that swirled above him in chilled clarity, the very Universe that Pappy's god in wisdom untold had designed and made, and so could he understand that this same cruel, mean place was also, at the very same time, full of kindness and love. "Pappy?" he heard his grandson whisper. "Yeah boy?" "I'm – I – I'm sorry…"

Now Gus – Pappy – felt that the wall that needed to come down had come down, now he knew that he could raise his grandchild and shelter him and protect him and guide him into manhood and carry on the Lynch name with honor and with pride and respect.

Now – now Pappy lowered him down so that they were face to face, so that their identical eyes, gelid, frozen-over, but warm in this and all the Winters they would share together, now met.

He pointed, down the mountain slope, the trees that twinkled with ice, and he whispered: "G'out with joy." He grinned an encouraging, knowing smile. "Be led forth with peace – the mountains –n'the hills shall break forth before ye into singin, and all the trees o'the field shall clap their hands…"

He hugged his little grandson so tight he knew he would never forget.

And right then, right that very second – everything was worth it.

There had been a road here, there had been a journey undertaken, ever since Iris had blushed to see him watching her across the room at that little church in Summersville – ever since he had clutched Ralph's body in Korea and begged for him, screaming, to get up, to wake up – ever since he would join his cousin's melody on the banjo on those fine Summer days.

They were all gone…but Bligh, his grandson, his blood, his flesh, his true legacy, was here.

And of all the names, all the titles, all the ways he was or would be looked at – none of them would ever matter as much as the one that this serious, black-haired boy would foist upon him:

"Pappy," little Bligh said again, and his eyes glimmered and became overfull with tears.

Gus – Gustavus, Pappy – grinned at him, a full and proud smile, and kissed him gently on the cheek.

"S'right boy," he whispered, but loud enough that the silent night of the approaching Christmas Eve allowed it to echo across time, space – and names. "I'm yer Pappy."

0 notes

Text

Ask Now the Beasts